Abstract

Importance.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is updating its 2013 lung cancer screening guidelines, which recommend annual screening in adults aged 55 through 80 years who have at least a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years.

Objective.

To inform the USPSTF guidelines by estimating the benefits and harms associated with various low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) screening strategies.

Design, Setting, and Participants.

Comparative simulation modeling with 4 lung cancer natural history models for individuals from the 1950 and 1960 US birth cohorts followed from ages 45 to 90 years.

Exposures.

Screening with varying starting ages, stopping ages, and screening frequency. Eligibility criteria based on age, cumulative pack-years, and years since quitting smoking (risk factor–based), or on age and individual lung cancer risk estimation using risk prediction models with varying eligibility thresholds (risk model–based). A total of 1092 strategies were modeled. Full uptake and adherence were assumed for all scenarios.

Main Outcomes and Measures.

Benefits: Estimated lung cancer deaths averted and life-years gained compared with no screening. Harms: Estimated lifetime number of LDCT screens, false-positive results, biopsies, overdiagnosed cases, and radiation-related lung cancer deaths.

Results.

Efficient screening programs estimated to yield the most benefits for a given number of screens were identified. Most of the efficient risk factor–based strategies started screening at age 50 or 55 and stopped at age 80. The 2013 USPSTF-recommended criteria were not among the efficient strategies for the 1960 birth cohort. Annual strategies with a 20 pack-years minimum criterion were efficient and compared with the current criteria were estimated to increase eligibility (20.6% to 23.6% vs 14.1% of the population ever eligible), lung cancer deaths averted (469 to 558 vs 381 per 100,000), and life-years gained (6,018 to 7,596 vs 4,882 per 100,000). However, these strategies were estimated to result in more false-positive tests (1.9 to 2.5 vs 1.9 per person screened), overdiagnosed cases (83 to 94 vs 69 per 100,000), and radiation-related lung cancer deaths (29.0 to 42.5 vs 20.6 per 100,000). Risk model–based vs risk factor–based strategies were estimated to be associated with higher benefits and fewer radiation-related deaths, but more overdiagnosed cases.

Conclusions and Relevance.

Microsimulation modeling studies suggested that LDCT screening for lung cancer compared with no screening may increase lung cancer deaths averted and life-years gained when optimally targeted and implemented. Screening individuals aged 50 or 55 through age 80 with 20 or more pack-years of smoking exposure was estimated to result in more benefits than current criteria and less disparity in eligibility by sex and race/ethnicity.

Introduction

In 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in adults aged 55 through 80 years who have at least a 30 pack-year smoking history and currently smoke or have quit within the past 15 years (B recommendation).1 These recommendations were largely based on the results of the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST).2-4 Since then, new clinical guidelines have emerged for classifying and managing screen-detected pulmonary nodules,5 and new evidence has emerged on the benefits and harms of LDCT screening.6, 7

Early reports of screening practices suggest that the implementation of LDCT screening in the US has not been optimal, with less than 20% of eligible individuals accessing screening, while some ineligible individuals with smoking exposure less than 30 pack-years and some with severe comorbidities being screened.8-10 In addition, some groups, such as African American men, have been shown to be at high lung cancer risk even when not meeting current criteria.11, 12 Recognizing that simulation models provide an approach to extrapolate available evidence and predict long-term outcomes,13-15 the USPSTF commissioned a simulation analysis to estimate the long-term benefits and harms associated with various LDCT screening strategies to inform their lung cancer screening recommendations update.

Methods

Four lung cancer simulation models developed within the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) were used to estimate the benefits and harms of 1,092 LDCT screening strategies: MISCAN-Lung Model, Massachusetts General Hospital–Harvard Medical School (MGH-HMS), Lung Cancer Outcomes Simulation (LCOS), and University of Michigan (UM). All 4 models were part of the 2013 lung cancer screening decision analysis conducted for the USPSTF.1, 13 The full collaborative modeling study technical report is available at WEBPAGE.

Model Descriptions

The simulation models differ in terms of parameters, assumptions, model structure, and approach; comparison of results across models serves as an assessment of model specification uncertainty. Although they share common inputs, each modeling team developed its model independently. The models explicitly considered individual factors associated with lung cancer risk, including the number of cigarettes smoked per day at any given age, the age of smoking initiation, duration of smoking, and the number of years since quitting.

eTable 1 shows a comparison of model characteristics. The models simulate the natural history of lung cancer given an individual’s sex, birth year, and smoking history. The central component of each model is a dose-response module that predicts age- and sex-specific lung cancer incidence risk as a function of individual smoking history. A key component to all models is the shared Smoking History Generator, a validated microsimulator developed by the CISNET Lung Group that simulates individual smoking histories for the US population.16, 17 These smoking histories serve as the main inputs for the simulations.

Each model can simulate the effects associated with screening given an individual’s smoking and lung cancer natural history. The models were calibrated to both the NLST and the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial.13, 18 Three of the models (MGH-HMS, LCOS and UM) were updated to reflect current practice and outcomes according to the Lung Imaging Reporting and Data System (Lung-RADS) guidelines.19 The other model (MISCAN) uses false-positive tests, sensitivities, and screening result rates based fully on the NLST, allowing for comparison of alternative protocols and assumptions. Additional details are provided in eMethods.

Screening Strategies

Risk Factor–Based Strategies

The primary analysis focused on risk factor–based strategies using criteria similar to the 2013 USPSTF recommendation, which determine eligibility as a function of age and smoking exposure (pack-years and years since quitting). These strategies varied by starting age (45, 50, 55 years), stopping age (75, 77, 80 years), frequency of screening (annual, biennial), minimum pack-years (20, 25, 30, 40 pack-years), and maximum years since quitting smoking (10, 15, 20, 25 years). A total of 288 risk factor–based screening scenarios (eTable 2) were evaluated and compared with a reference no-screening scenario.

Various studies have suggested that reducing the minimum pack-year eligibility criterion to 20 pack-years would increase the number of lung cancer deaths that would be preventable by screening and also reduce sex and racial disparities in eligibility.6, 11, 12, 20 Motivated by these studies, risk factor–based strategies with 20 pack-years as the minimum pack-year criterion were further analyzed.

Risk Model–Based Strategies

The potential effects of screening with eligibility criteria based on multivariable risk prediction models (PLCOm2012 model [MPLCOm2012],21 Lung Cancer Death Risk Assessment Tool [LCDRAT] model [MLCDRAT],22 and the Bach model23) that use smoking duration and intensity, sex, and age to estimate lung cancer risk (risk model–based strategies) were also assessed.

These risk prediction models were selected based on their demonstrated ability to identify individuals at high probability of developing lung cancer,22, 24 their practicality and ease of implementation, and their use as risk calculators in current lung screening recommendations/implementations.25 Simplified versions of these risk models considering only age, sex, and smoking covariates were used.26 No other risk factors, such as race/ethnicity or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), were considered because including these would require joint simulation of these factors with smoking, sex, and age at the population level and availability of well-calibrated and validated lung cancer natural history models incorporating all covariates.

The evaluated risk model–based strategies varied by risk prediction model, model-specific risk threshold (minimum level of risk required for eligibility), and lower (50, 55 years) and upper (75, 77, 80 years) age limits. eTable 2 shows a summary of the resulting 804 risk model–based screening strategies.

Scenario Simulation and Analysis

The CISNET simulation models were used to estimate the benefits and harms of each strategy in the US 1950 and 1960 birth cohorts. These birth cohorts were selected because they are now in the middle of their screening eligibility according to current guidelines (70 years old for 1950 and 60 years old for 1960) and are representative of different time periods of the tobacco epidemic (higher smoking prevalence and intensity for 1950 vs lower rates for 1960). One million smoking histories per sex, per cohort were simulated using the Smoking History Generator and used as common inputs by each model to simulate individual-level outcomes under the different screening scenarios. All simulations were performed assuming that all screen-eligible individuals would undergo screening and adhere to ongoing screening (annual or biennial) for the duration of their eligibility. Smoking cessation and the risk of competing causes of disease and death were assumed to be unaffected by screening results. The risk model–based screening analysis was restricted to the 1960 birth cohort.

Outcomes

Simulated outcomes included counts of screening examinations, the number and percentage of persons screened given an eligibility criterion, number of lung cancer cases and deaths, life-years gained relative to a no-screening scenario, number of false-positive screens, number of biopsies, and overdiagnosed cases (defined as lung cancer cases detected by screening that would not have been diagnosed nor caused death in the absence of screening). Two models (MGH-HMS and UM) were used to estimate radiation-related lung cancer deaths. Outcomes are provided per 100,000 individuals alive at age 45 years (including both screened and unscreened individuals), rather than “per screened population” so that these are comparable across scenarios.

Selection of Consensus-Efficient Scenarios

Efficient scenarios estimated to provide the most lung cancer deaths averted and life-years gained for a given level of screening (number of LDCT screens per 100,000 population) were identified via a data envelopment analysis.13, 27 The analysis ranks scenarios based on their distance to the model-specific efficient frontier of LDCT screens vs deaths averted and LDCT screens vs life-years gained. Model-specific efficient scenarios were those on the model's efficient frontier or in the top 30% model rank. That is, model-specific efficient scenarios were those which the model estimated to result simultaneously in the most (or close to the most) lung cancer deaths averted and life-years gained for a given level of screening. Scenarios which were deemed efficient by at least 3 of the 4 models were called consensus-efficient, and were selected for further analysis. This approach ensured an equal weighting of the models. More details are provided in the full report.

For each identified consensus-efficient program, sex-specific results were aggregated to derive population-level mean (across the 4 CISNET models) predicted outcomes. Special attention was given to consensus-efficient scenarios leading to at least 9% mortality reduction.

Sensitivity Analysis

Additional sensitivity analyses assessed the effectiveness of different LDCT screening strategies for the effect of limiting screening to only those with more than 5 years of life expectancy assuming a perfect assessment of life expectancy.

Results

Presented results focus on the 1960 birth cohort. Results for the 1950 birth cohort are available in the Supplement and full report. Unless otherwise indicated, results presented are for men and women combined.

Risk Factor–Based Strategies

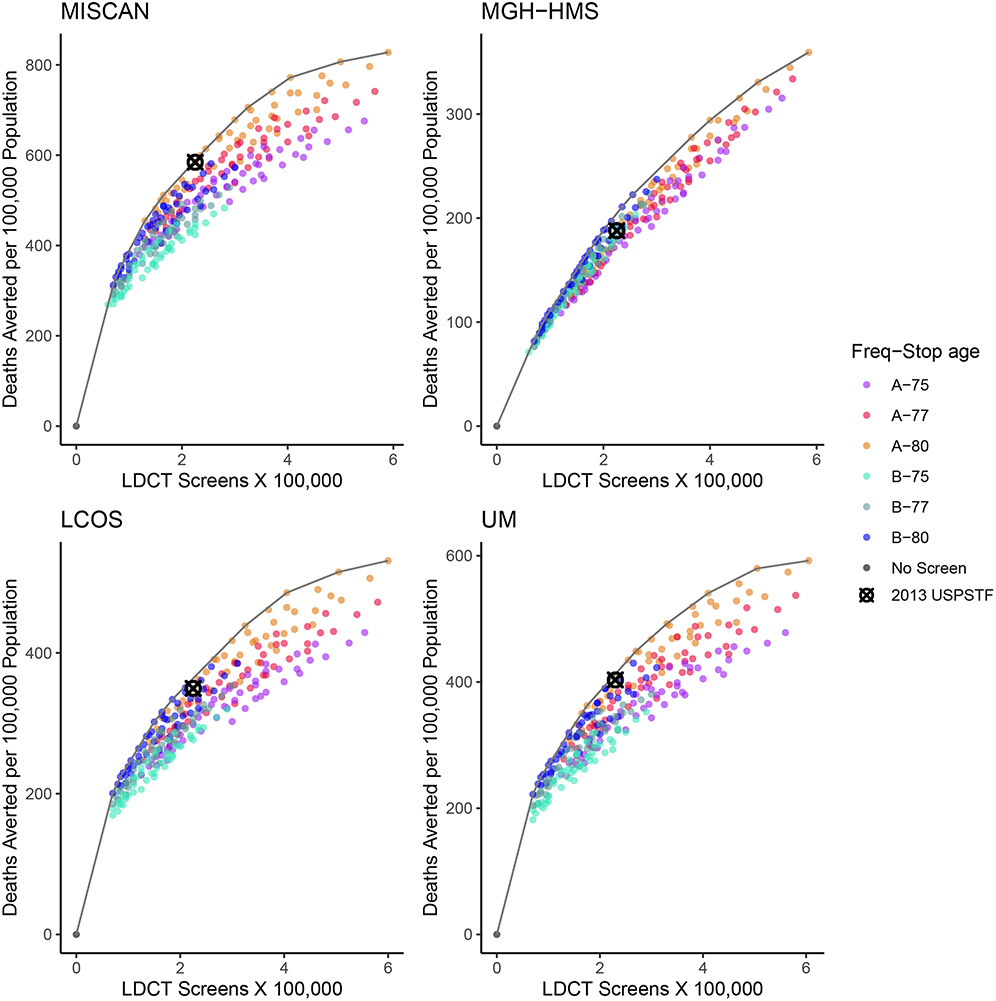

Compared with no screening, risk factor–based screening strategies were estimated to result in lung cancer deaths averted and life-years gained, with variations according to the level of screening (number of LDCT screens) and specific eligibility criteria of each scenario. Figure 1 shows the number of LDCT screens and deaths averted relative to no screening for each risk factor–based strategy. In general, scenarios on the efficient frontier had a screening stopping age of 80 years. Biennial strategies are concentrated on the lower/left side of each panel because they require fewer LDCT screens and are estimated to avert fewer deaths. Annual strategies tend to be on the upper/right side because they require more LDCT screens and are estimated to generally avert more deaths. Although the absolute range of predicted deaths averted varies by model, the general efficiency patterns were consistent across CISNET models. The 2013 USPSTF-recommended strategy was on or among the closest to the frontier for 3 out of the 4 models.

Figure 1. Number of LDCT Screening Examinations vs. the Number of Lung Cancer Deaths Averted in Each of the 288 Risk Factor–Based Strategies Evaluated by the 4 CISNET Models—1960 Birth Cohort.

Note: Each point represents a different scenario, and the line represents the estimated efficient frontier per model. Strategies vary by age at starting and stopping screening, frequency, pack-years criterion, and years since quitting smoking (eTable 2). The colors differentiate strategies by frequency (annual–A vs. biennial–B) and the age at stopping screening (75, 77, 80 years). The no-screening (black dot) and the 2013 USPSTF-recommended (“⊗” mark) scenarios are highlighted. Four CISNET lung cancer screening simulation models from different institutions were used for the analysis: Microsimulation Screening Analysis (MISCAN)-Lung Model from Erasmus University Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital–Harvard Medical School (MGH-HMS), the Lung Cancer Outcomes Simulation (LCOS) from Stanford University, and University of Michigan (UM).

Abbreviations: CISNET=Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network; LDCT=low-dose computed tomography; USPSTF=U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

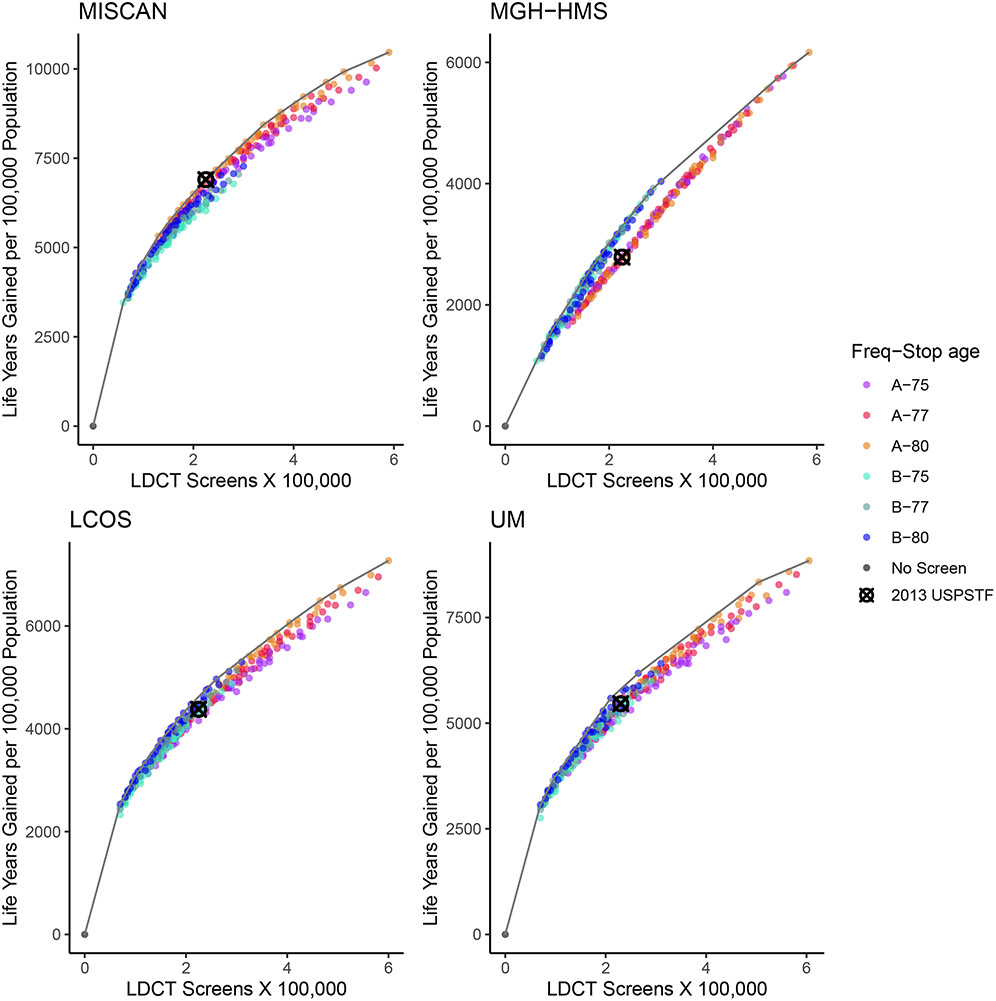

Figure 2 shows the corresponding efficient frontier curves using life-years gained as the benefit metric. The patterns were similar but show less variability among strategies than for deaths averted. In this case, the 2013 USPSTF-recommended strategy was only on (or among the closest to) the efficient frontier for 1 of the 4 models.

Figure 2. Number of LDCT Screening Examinations vs. Life-Years Gained in Each of the 288 Risk Factor–Based Strategies Evaluated by the 4 CISNET Models—1960 Birth Cohort.

Note: Each point represents a different scenario, and the line represents the estimated efficient frontier per model. Strategies vary by age at starting and stopping screening, frequency, pack-years criterion, and years since quitting smoking (eTable 2). The colors differentiate strategies by frequency (annual–A vs. biennial–B) and the age at stopping screening (75, 77, 80 years). The no-screening (black dot) and the 2013 USPSTF-recommended (“⊗” mark) scenarios are highlighted. Four CISNET lung cancer screening simulation models from different institutions were used for the analysis: Microsimulation Screening Analysis (MISCAN)-Lung Model from Erasmus University Medical Center, Massachusetts General Hospital–Harvard Medical School (MGH-HMS), the Lung Cancer Outcomes Simulation (LCOS) from Stanford University, and University of Michigan (UM).

Abbreviations: CISNET=Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network; LDCT=low-dose computed tomography; USPSTF=U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

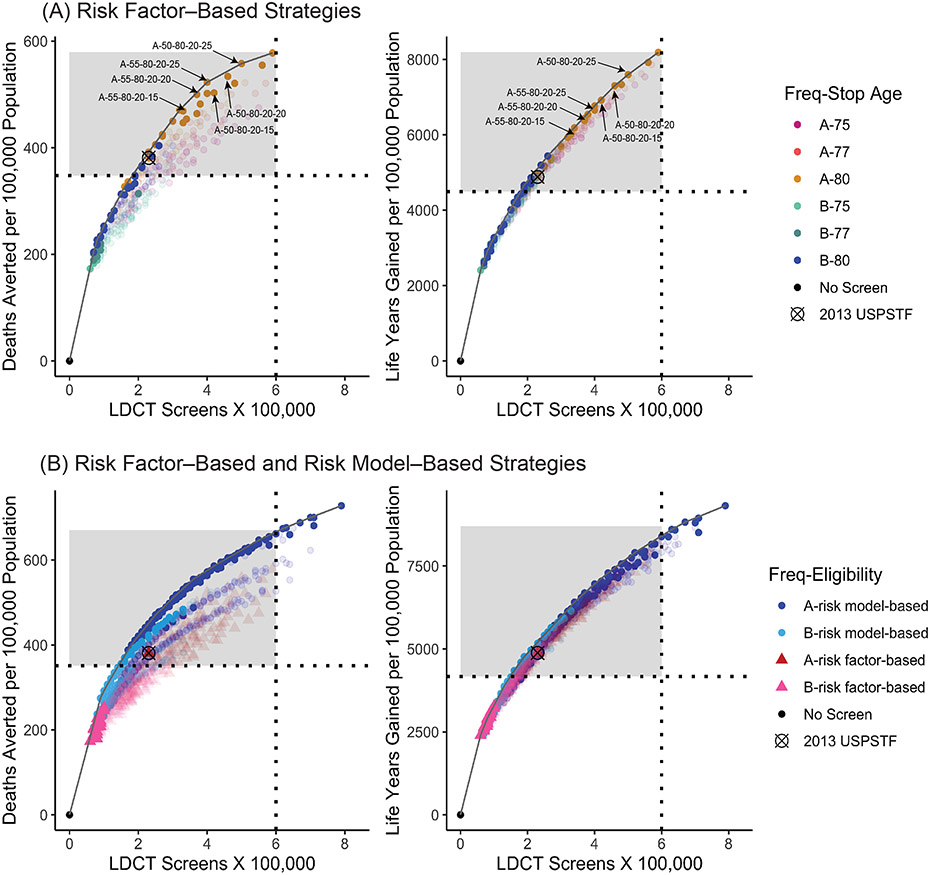

Risk Factor–Based Consensus-Efficient Scenarios

Fifty-seven consensus-efficient scenarios were identified. The 2013 USPSTF-recommended scenario was not 1 of the 57 consensus-efficient scenarios. Figure 3 (top) shows the mean (across CISNET models) number of LDCT screens compared with the number of deaths averted (left) and life-years gained (right) for all risk factor–based strategies, highlighting the consensus-efficient scenarios. Most of the consensus-efficient scenarios were on the efficient frontier or among the closest to the frontier for both benefit metrics. Detailed outcomes for the 57 consensus-efficient scenarios are shown in eTables 3 and 4.

Figure 3. Number of LDCT Screening Examinations vs. the Number of Lung Cancer Deaths Averted (Left Panels) and Life-Years Gained (Right Panels) —Average Values Across the 4 CISNET Models—1960 Birth Cohort.

Note: (A) Each point represents a different risk factor-based screening scenario, and the curve represents the estimated efficient frontier for the average model. Strategies vary by age at starting and stopping screening, frequency, pack-years criterion, and years since quitting smoking (eTable 2). The colors differentiate strategies by frequency (annual–A vs. biennial–B) and the age at stopping screening (75, 77, 80 years). The no-screening (black dot), the 2013 USPSTF-recommended (“⊗” mark), and six selected consensus-efficient 20 pack-year scenarios are highlighted. The panels show all 288 risk factor–based strategies but highlight (solid color points) those identified as consensus efficient (listed in eTable 3 and eTable4). The horizontal line divides strategies with less than or at least a 9% lung cancer mortality reduction. The shaded region includes those scenarios with at least a 9% lung cancer mortality reduction (listed in Tables 1 and 2). (B) Risk factor–based screening scenarios are represented with triangle points and risk model–based screening scenarios with round points. The curve represents the estimated overall efficient frontier for the average model. Risk factor–based strategies vary by age at starting and stopping screening, frequency, pack-years criterion, and years since quitting smoking (eTable 2). Risk model–based strategies vary by risk model, risk thresholds, and frequency (eTable 2). The colors differentiate strategies by frequency (annual–A vs. biennial–B). The no-screening (black dot) and the 2013 USPSTF-recommended (“⊗” mark) scenarios are highlighted. Panels show all considered strategies but highlight (solid color points) those identified as consensus efficient (listed in the full report). The vertical line represents 600 000 LDCT screens, and the horizontal line divides strategies with less than or at least a 9% lung cancer mortality reduction. The shaded region includes those scenarios with fewer than 600 000 LDCT screens per 100 000 population and providing at least a 9% lung cancer mortality reduction (listed in eTable 12 and eTable 13).

Abbreviations: CISNET=Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network; LDCT=low-dose computed tomography; USPSTF=U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

Table 1 shows the estimated benefits of the consensus-efficient scenarios restricted to those leading to at least a 9.0% lung cancer mortality reduction plus the 2013 USPSTF-recommended scenario (a total of 26 scenarios). These are estimated to result in a lung cancer mortality reduction close to or greater than that of the 2013 USPSTF-recommended strategy (9.8%). Of the selected consensus-efficient scenarios, 5 were biennial and 20 annual; all had 80 years as the stopping age and ranged from 14.5% to 24.1% eligible individuals. In terms of minimum pack-years, 13 (52.0%) had 20 pack-years, 8 (32.0%) had 25 pack-years, 4 (16.0%) had 30 pack-years, and none had 40 pack-years. The estimated number of lung cancer deaths averted per 100,000 population ranged from 348 to 578, corresponding to a population-level mortality reduction ranging from 9.0% to 14.9%. The estimated life-years gained per 100,000 population ranged from 4,490 to 8,186 and the number needed to screen (NNS) (persons ever screened per death averted) from 34 to 63.

Table 1.

Benefits of 25 Selecteda Consensus-Efficient Risk Factor–Based Screening Programs Plus the 2013 USPSTF-Recommended Criteria Ordered by LDCT Screens—1960 Birth Cohort

| Scenario | % Eligible | LDCT Screens |

Screen- Detected Lung Cancer Cases |

Lung Cancer Mortality Reduction (%) |

Lung Cancer Deaths Averted |

Life-Years Gained |

Life-Years Gained per Lung Cancer Deaths Averted |

LDCT Screens per Life-Years Gained |

LDCT Screens per Lung Cancer Deaths Averted |

NNS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-55-80-20-20 | 22.0 | 189,587 | 1,134 | 9.0 | 348 | 4,490 | 12.9 | 42 | 545 | 63 |

| B-55-80-20-25 | 22.7 | 207,010 | 1,189 | 9.5 | 366 | 4,701 | 12.8 | 44 | 566 | 62 |

| B-50-80-25-25 | 19.0 | 208,753 | 1,169 | 9.4 | 363 | 4,859 | 13.4 | 43 | 575 | 52 |

| A-55-80-30-15b | 14.1 | 227,443 | 1,102 | 9.8 | 381 | 4,882 | 12.8 | 47 | 597 | 37 |

| A-55-80-25-10 | 16.0 | 234,030 | 1,131 | 10.1 | 392 | 4,969 | 12.7 | 47 | 597 | 41 |

| B-50-80-20-20 | 23.3 | 239,223 | 1,226 | 9.9 | 384 | 5,194 | 13.5 | 46 | 623 | 61 |

| A-55-80-30-20 | 14.5 | 250,592 | 1,169 | 10.5 | 406 | 5,170 | 12.7 | 48 | 617 | 36 |

| B-50-80-20-25 | 23.6 | 258,024 | 1,288 | 10.4 | 404 | 5,436 | 13.5 | 47 | 639 | 58 |

| A-55-80-25-15 | 17.2 | 267,471 | 1,219 | 11.0 | 425 | 5,387 | 12.7 | 50 | 629 | 40 |

| A-55-80-30-25 | 14.8 | 269,096 | 1,218 | 10.9 | 422 | 5,333 | 12.6 | 50 | 638 | 35 |

| A-55-80-25-20 | 18.0 | 298,016 | 1,295 | 11.6 | 450 | 5,690 | 12.6 | 52 | 662 | 40 |

| A-55-80-25-25 | 18.3 | 324,008 | 1,354 | 12.2 | 471 | 5,930 | 12.6 | 55 | 688 | 39 |

| A-55-80-20-15c | 20.6 | 330,095 | 1,334 | 12.1 | 469 | 6,018 | 12.8 | 55 | 704 | 44 |

| A-50-80-30-25 | 15.3 | 334,396 | 1,273 | 11.5 | 447 | 6,066 | 13.6 | 55 | 748 | 34 |

| A-50-80-25-15 | 18.5 | 344,294 | 1,282 | 11.7 | 454 | 6,187 | 13.6 | 56 | 758 | 41 |

| A-55-80-20-20c | 22.0 | 369,610 | 1,423 | 12.9 | 500 | 6,379 | 12.8 | 58 | 739 | 44 |

| A-50-80-20-10 | 21.2 | 369,742 | 1,295 | 12.0 | 464 | 6,435 | 13.9 | 57 | 797 | 46 |

| A-50-80-25-20 | 18.9 | 377,405 | 1,357 | 12.5 | 482 | 6,542 | 13.6 | 58 | 783 | 39 |

| A-50-80-25-25 | 19.0 | 404,469 | 1,417 | 13.0 | 502 | 6,764 | 13.5 | 60 | 806 | 38 |

| A-55-80-20-25c | 22.7 | 404,596 | 1,492 | 13.5 | 523 | 6,654 | 12.7 | 61 | 774 | 43 |

| A-50-80-20-15c | 22.6 | 419,030 | 1,401 | 13.0 | 503 | 6,918 | 13.8 | 61 | 833 | 45 |

| A-50-80-20-20c | 23.3 | 463,457 | 1,487 | 13.8 | 534 | 7,301 | 13.7 | 63 | 868 | 44 |

| A-45-80-25-25 | 19.4 | 482,601 | 1,448 | 13.5 | 521 | 7,336 | 14.1 | 66 | 926 | 37 |

| A-50-80-20-25c | 23.6 | 500,430 | 1,560 | 14.4 | 558 | 7,596 | 13.6 | 66 | 897 | 42 |

| A-45-80-20-20 | 24.0 | 557,453 | 1,523 | 14.4 | 555 | 7,919 | 14.3 | 70 | 1,004 | 43 |

| A-45-80-20-25 | 24.1 | 594,973 | 1,592 | 14.9 | 578 | 8,186 | 14.2 | 73 | 1,029 | 42 |

Strategies with at least 9.0% lung cancer mortality reduction.

2013 USPSTF-recommended strategy.

Six selected consensus-efficient 20 pack-year strategies.

Numbers are per a 100 000-person cohort followed from ages 45 to 90 years and are based on mean estimates across the 4 models. The screening programs are labeled as follows: frequency (A–annual and B–biennial)–age start–age stop–minimum pack-years–maximum years since quitting.

Abbreviations: LDCT=low-dose computed tomography; NNS=number (people) needed to screen (ever) to prevent 1 lung cancer death; USPSTF=US Preventive Services Task Force.

Table 2 shows the corresponding estimated harms. The mean number of false-positive results per screened individual ranged from 1.2 to 2.8, the number of biopsies from 518 to 922 per 100,000 population, the mean number of LDCT examinations per screened individual from 8.6 to 24.9, and the overdiagnosis rate per screen-detected lung cancer from 5.6% to 6.3%. The estimated number of radiation-related lung cancer deaths ranged from 17.5 to 55.0 per 100,000 population.

Table 2.

Harms of 25 Selecteda Consensus-Efficient Risk Factor–Based Screening Programs Plus the 2013 USPSTF-Recommended Criteria Ordered by LDCT Screens—1960 Birth Cohort

| Scenario | LDCT Screens |

LDCT Scans |

Mean LDCT Screens per Person Screened |

Mean False- Positive Results per Person Screened |

Biopsies | Overdiagnosed Cases |

Overdiagnosis: % of All Lung Cancer Cases |

Overdiagnosis: % of Screen- Detected Lung Cancer Cases |

Radiation- Related Lung Cancer Deathsd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-55-80-20-20 | 189,587 | 209,334 | 8.6 | 1.2 | 526 | 64 | 1.3 | 5.6 | 17.5 |

| B-55-80-20-25 | 207,010 | 227,740 | 9.1 | 1.3 | 557 | 67 | 1.4 | 5.6 | 18.2 |

| B-50-80-25-25 | 208,753 | 228,965 | 11.0 | 1.5 | 546 | 68 | 1.4 | 5.8 | 19.3 |

| A-55-80-30-15b | 227,443 | 247,644 | 16.1 | 1.9 | 518 | 69 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 20.6 |

| A-55-80-25-10 | 234,030 | 254,870 | 14.6 | 1.8 | 536 | 71 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 21.5 |

| B-50-80-20-20 | 239,223 | 261,627 | 10.3 | 1.4 | 593 | 70 | 1.4 | 5.7 | 22.8 |

| A-55-80-30-20 | 250,592 | 272,008 | 17.3 | 2.0 | 554 | 73 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 21.5 |

| B-50-80-20-25 | 258,024 | 281,421 | 10.9 | 1.5 | 626 | 74 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 23.6 |

| A-55-80-25-15 | 267,471 | 290,163 | 15.6 | 1.9 | 586 | 77 | 1.5 | 6.3 | 23.4 |

| A-55-80-30-25 | 269,096 | 291,461 | 18.2 | 2.1 | 580 | 76 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 22.1 |

| A-55-80-25-20 | 298,016 | 322,330 | 16.6 | 2.0 | 630 | 82 | 1.6 | 6.3 | 24.7 |

| A-55-80-25-25 | 324,008 | 349,657 | 17.7 | 2.1 | 664 | 84 | 1.7 | 6.2 | 25.6 |

| A-55-80-20-15c | 330,095 | 356,390 | 16.0 | 1.9 | 667 | 83 | 1.7 | 6.2 | 29.0 |

| A-50-80-30-25 | 334,396 | 359,972 | 21.9 | 2.5 | 639 | 76 | 1.5 | 6.0 | 29.9 |

| A-50-80-25-15 | 344,294 | 370,892 | 18.6 | 2.2 | 658 | 77 | 1.6 | 6.0 | 32.1 |

| A-55-80-20-20c | 369,610 | 398,094 | 16.8 | 2.0 | 722 | 89 | 1.8 | 6.3 | 30.6 |

| A-50-80-20-10 | 369,742 | 397,994 | 17.4 | 2.1 | 684 | 77 | 1.5 | 5.9 | 36.5 |

| A-50-80-25-20 | 377,405 | 405,682 | 20.0 | 2.3 | 701 | 82 | 1.6 | 6.0 | 33.5 |

| A-50-80-25-25 | 404,469 | 434,104 | 21.3 | 2.5 | 735 | 85 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 34.9 |

| A-55-80-20-25c | 404,596 | 434,892 | 17.8 | 2.1 | 765 | 94 | 1.9 | 6.3 | 31.9 |

| A-50-80-20-15c | 419,030 | 449,947 | 18.5 | 2.2 | 750 | 84 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 38.6 |

| A-50-80-20-20c | 463,457 | 496,698 | 19.9 | 2.3 | 804 | 89 | 1.8 | 6.0 | 40.6 |

| A-45-80-25-25 | 482,601 | 515,967 | 24.9 | 2.8 | 797 | 86 | 1.7 | 5.9 | 45.8 |

| A-50-80-20-25c | 500,430 | 535,519 | 21.2 | 2.5 | 849 | 94 | 1.9 | 6.0 | 42.5 |

| A-45-80-20-20 | 557,453 | 595,203 | 23.2 | 2.7 | 879 | 91 | 1.8 | 6.0 | 53.1 |

| A-45-80-20-25 | 594,973 | 634,568 | 24.7 | 2.8 | 922 | 95 | 1.9 | 6.0 | 55.0 |

Strategies with at least 9.0% lung cancer mortality reduction.

2013 USPSTF-recommended strategy.

Six selected consensus-efficient 20 pack-year strategies.

Mean of 2 models (MGH-HMS and UM).

Numbers are per a 100 000-person cohort followed from ages 45 to 90 years and are based on mean estimates across the 4 models. The screening programs are labeled as follows: frequency (A–annual and B–biennial)–age start–age stop–minimum pack-years–maximum years since quitting.

Abbreviations: LDCT=low-dose computed tomography; MGH-HMS=Massachusetts General Hospital–Harvard Medical School; UM=University of Michigan; USPSTF=US Preventive Services Task Force.

eTables 5 and 6 provide the range of benefits and harms estimates across the 4 CISNET models.

20 Pack-Year Scenarios

Consensus-efficient annual 20 pack-year strategies with annual frequency and stopping age of 80, with starting ages of 50 or 55 years, and with at least 15 years since quitting smoking were examined further. There were 6 such strategies: A-55-80-20-15, A-55-80-20-20, A-55-80-20-25, A-50-80-20-15, A-50-80-20-20, and A-50-80-20-25 (Figure 3).

Expanding current screening eligibility to include individuals with 20 to 29 smoking pack-years was estimated to increase the percentage of the population ever screened from 14.1% to 20.6% to 23.6%, depending on the screening starting age and the number of years since quitting smoking. The mean number (across models) of LDCT screens per 100,000 population for these 20 pack-year scenarios ranged from 330,095 to 500,430 compared with 227,443 for the 2013 USPSTF-recommended strategy. The mean age at last screen ranged from 69.0 to 72.5 years compared with 71.3 years for the current criteria (eTable 7). The mean age at first screen ranged from 51.5 years (for all strategies with a starting age of 50 years) to 55.7 years vs 56.2 years for the current criteria (eTable 7).

The estimated number of lung cancer deaths averted per 100,000 population for the 20 pack-year strategies ranged from 469 to 558, corresponding to a mortality reduction ranging from 12.1% to 14.4%. The estimated life-years gained for the selected 20 pack-year strategies ranged from 6,018 to 7,596 per 100,000 and the NNS from 42 to 45. In comparison, the 2013 USPSTF-recommended strategy was estimated to result in 381 deaths averted, a 9.8% mortality reduction, 4,882 life-years gained, and an NNS of 37.

The estimated mean number of false-positive results per screened individual ranged from 1.9 to 2.5 for the selected 20 pack-year strategies vs 1.9 for the 2013 USPSTF-recommended strategy. The number of biopsies ranged from 526 to 849 per 100,000 vs 518 per 100,000 for the current criteria. The number of overdiagnosed cancers ranged from 83 to 94 per 100,000 population vs 69 per 100,000 for the current criteria. The rate of overdiagnosis per screen-detected lung cancer ranged from 6.0% to 6.3% vs 6.3% for the current criteria. In addition, the number of radiation-related lung cancer deaths ranged from 29.0 to 42.5 per 100,000 population vs 20.6 per 100,000 population for the current criteria.

Comparisons by sex are shown in eTables 8 and 9. These estimates show similar patterns as for the whole population but with higher increases in eligibility and deaths averted and life-years gained for women than men. Although the analysis did not consider different racial or ethnic groups, comparisons of the percentage of individuals eligible for screening in the United States under the 2013 USPSTF-recommended strategy vs selected 20 pack-year strategies by sex and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indian/Alaska Natives) are presented in the full report and eTables 10 and 11.

Risk Model–Based Strategies

Risk model–based strategies were estimated to result in considerably more lung cancer deaths averted for a given number of LDCT screens than risk factor–based strategies. However, the differences in life-years gained were less pronounced. Figure 3 (bottom) shows the mean (across CISNET models) number of LDCT screens vs the number of deaths averted (left) and life-years gained (right) for all scenarios. eFigures 1 and 2 show these for each CISNET model. The estimated benefits and harms of 144 consensus-efficient scenarios with at least 9% lung cancer mortality reduction and requiring fewer than 600,000 LDCT screens per 100,000 are presented in eTables 12 and 13.

Detailed comparisons of the 2013 USPSTF-recommended and the 6 selected 20 pack-year scenarios with corresponding risk model–based strategies with similar numbers of LDCT screens are presented in eTables 14 through 20. These show that the age of screening shifts to older ages for the risk model–based screening strategies compared with the risk factor–based strategies. This shift leads to higher numbers of deaths averted and overdiagnosed cases and lower numbers of screens per person screened and radiation-related lung cancer deaths for the risk model–based screening strategies.

Sensitivity Analyses

The general patterns observed for the 1960 birth cohort held for the 1950 birth cohort, with some variations in absolute numbers due to the higher level of smoking in the 1950 birth cohort. In general, limiting screening to only those with more than 5 years of life expectancy, assuming a hypothetical perfect assessment of life expectancy, did not greatly affect the resulting estimated benefits (deaths averted or life-years gained) but was estimated to result in fewer harms and, particularly, considerably fewer overdiagnosed cases. This finding was particularly true for strategies screening at older ages.

Discussion

The findings of this simulation analysis suggest that optimally targeted LDCT screening could lead to important reductions in lung cancer mortality and result in significant life-years gained. Although the analysis cannot identify a single optimal strategy, it identified a set of screening programs estimated to yield the most benefits for a given level of screening (efficient strategies). The analysis estimates that strategies screening individuals aged 50 or 55 through 80 years with 20 or more pack-years of smoking exposure are efficient and would result in more benefits than current criteria, but also more harms.

Recent studies have suggested that expanding eligibility to include ever-smokers with 20 to 29 pack-years of exposure would increase the proportion of lung cancers preventable by screening and reduce disparities in eligibility by race/ethnicity and sex.11, 12, 20, 28-30 Pinsky et al showed that reducing the minimum pack-years to 20 should increase the percentage of women and minorities who would be eligible for screening.11 They also found that the risk of 20 to 29 pack-year current smokers is comparable to that of screening eligible former smokers based on the 2013 USPSTF-recommended criteria. Aldrich et al recently found that proportionally fewer African Americans with lung cancer would have been eligible for screening vs whites with lung cancer and that expanding the criteria to include 20 to 29 pack-year ever-smokers would considerably increase the screening sensitivity for African Americans.12 The recently published NELSON trial, which found a 24% lung cancer mortality relative reduction at 10 years after 4 rounds of LDCT screening vs a no-screening group, included ever-smokers aged 50 to 74 years, with lower smoking exposure criteria than the NLST and current recommendations,6 providing additional support to expanding the age and smoking eligibility criteria.

The comparisons by sex and race/ethnicity suggest that the relative increase in eligibility for screening from reducing the pack-year criterion to 20 pack-years from the current criterion of 30 pack-years would be larger for women than for men and for non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, and American Indian/Alaska Natives than for non-Hispanic whites and Asians.

The better performance of risk model–based screening vs risk factor–based strategies is largely because risk model–based strategies shift screening to older ages when lung cancer risk is highest. These findings are consistent with other recent studies in the literature.26, 31 The analysis shows that although the specific risk prediction model used for determining eligibility is an important consideration, an even more critical aspect is to determine eligibility risk thresholds specific to the corresponding risk prediction model.

The decision analysis used 4 established lung cancer natural history models that capture the complexity in smoking patterns and lung cancer risk and integrate and synthesize information from screening trials, large epidemiological prospective studies, and cancer surveillance data. The CISNET models and the Smoking History Generator have been shown to reproduce the patterns of smoking and lung cancer incidence and mortality in the US13, 16, 32 and thus provide a valid framework to extrapolate the potential effects of screening into the entire population. The relative performance of different scenarios according to their characteristics (starting and stopping age, minimum pack-years, maximum years since quitting, risk threshold) was consistent across CISNET models.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis assumed idealized 100% screening uptake and adherence for eligible individuals; did not explicitly examine incidental findings or other potential harms, such as adverse events; and was based on models calibrated to lung screening trial outcomes, which might not be representative of screening in real-world settings. Thus, estimations of benefits should be interpreted as an upper bound of what the actual effects could be. Second, the analysis focused only on age, smoking history, and sex, ignoring other important risk factors, such as race/ethnicity, history of COPD, exposure to occupational and environmental carcinogens, and family history of lung cancer. Third, the analysis did not consider potential implementation challenges of risk model–based screening or whether those could vary by setting or among different demographic groups. Several ongoing implementation studies and trials are evaluating the feasibility and potential of risk model–based screening in clinical settings, so far with promising results.19, 33-36 Fourth, the projections did not account for future improvements in lung cancer treatment and further changes in smoking trends. Recent developments in targeted therapies and immunotherapies could affect future lung cancer survival and screening efficacy.37 In addition, the modeling did not consider the potential additional benefits of complementary smoking cessation programs within the context of lung screening.38-40

Conclusions

Microsimulation modeling studies suggested that LDCT screening for lung cancer compared with no screening may increase lung cancer deaths averted and life-years gained when optimally targeted and implemented. Screening individuals aged 50 or 55 through 80 with 20 or more pack-years of smoking exposure was estimated to result in more benefits than current criteria and less disparity in eligibility by sex and race/ethnicity.

Supplementary Material

Funding/Support:

This research was funded under contract HHSA-290-2015-00011-I, Task Order 11 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department of Health and Human Services. We also acknowledge support from National Cancer Institute award U01CA199284.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

Investigators worked with USPSTF members and AHRQ staff to develop the scope and key questions for this decision analysis. AHRQ had no role in the model development and analyses. AHRQ staff provided project oversight, reviewed the report to ensure that the decision analysis met methodological standards, and distributed the draft for public comment. Otherwise, AHRQ had no role in the conduct of the study; model simulations, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript findings. The opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of AHRQ or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Additional Information: A draft version of the full decision analysis report underwent external peer review from 3 content experts (William C. Black, MD, Darmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center; Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, Medical University of South Carolina; and Ann Zauber, PhD, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) and 2 National Cancer Institute reviewers (Paul Pinsky, PhD, and Kathy Cronin, PhD). Comments from reviewers were considered in preparing the final decision analysis. USPSTF members and peer reviewers did not receive financial compensation for their contributions.

Editorial Disclaimer: This decision analysis is presented as a document in support of the accompanying USPSTF Recommendation Statement. It did not undergo additional peer review after submission to JAMA.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported.

References

- 1.Moyer VA. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014. Mar 4;160(5):330–8. doi: 10.7326/M13-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011. Aug 4;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinsky PF, Church TR, Izmirlian G, et al. The National Lung Screening Trial: results stratified by demographics, smoking history, and lung cancer histology. Cancer. 2013. Nov 15;119(22):3976–83. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Lung cancer incidence and mortality with extended follow-up in the National Lung Screening Trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2019. Oct;14(10):1732–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazerooni EA, Armstrong MR, Amorosa JK, et al. ACR CT accreditation program and the lung cancer screening program designation. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016. Feb;13(2 Suppl):R30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020. Feb 6;382(6):503–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker N, Motsch E, Trotter A, et al. Lung cancer mortality reduction by LDCT screening-Results from the randomized German LUSI trial. Int J Cancer. 2020. Mar 15;146(6):1503–13. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huo J, Shen C, Volk RJ, et al. Use of CT and chest radiography for lung cancer screening before and after publication of screening guidelines: intended and unintended uptake. JAMA Intern Med. 2017. Mar 1;177(3):439–41. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinsinger LS, Anderson C, Kim J, et al. Implementation of lung cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Intern Med. 2017. Mar 01;177(3):399–406. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richards TB, Doria-Rose VP, Soman A, et al. Lung cancer screening inconsistent with U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. Am J Prev Med. 2019. Jan;56(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinsky PF, Kramer BS. Lung cancer risk and demographic characteristics of current 20-29 pack-year smokers: implications for screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015. Nov;107(11)doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aldrich MC, Mercaldo SF, Sandler KL, et al. Evaluation of USPSTF lung cancer screening guidelines among African American adult smokers. JAMA Oncol. 2019. Jun 27doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Koning HJ, Meza R, Plevritis SK, et al. Benefits and harms of computed tomography lung cancer screening strategies: a comparative modeling study for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014. Mar 04;160(5):311–20. doi: 10.7326/m13-2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knudsen AB, Zauber AG, Rutter CM, et al. Estimation of benefits, burden, and harms of colorectal cancer screening strategies: modeling study for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016. Jun 21;315(23):2595–609. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandelblatt JS, Stout NK, Schechter CB, et al. Collaborative modeling of the benefits and harms associated with different U.S. breast cancer screening strategies. Ann Intern Med. 2016. Feb 16;164(4):215–25. doi: 10.7326/m15-1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moolgavkar SH, Holford TR, Levy DT, et al. Impact of reduced tobacco smoking on lung cancer mortality in the United States during 1975-2000. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012. Apr 4;104(7):541–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeon J, Holford TR, Levy DT, et al. Smoking and Lung Cancer Mortality in the United States From 2015 to 2065: A Comparative Modeling Approach. Ann Intern Med. 2018. Nov 20;169(10):684–93. doi: 10.7326/m18-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meza R, ten Haaf K, Kong CY, et al. Comparative analysis of 5 lung cancer natural history and screening models that reproduce outcomes of the NLST and PLCO trials. Cancer. 2014. Jun 1;120(11):1713–24. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinsky PF, Gierada DS, Black W, et al. Performance of Lung-RADS in the National Lung Screening Trial: a retrospective assessment. Ann Intern Med. 2015. Apr 07;162(7):485–91. doi: 10.7326/m14-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holford TR, Levy DT, Meza R. Comparison of smoking history patterns among African American and white cohorts in the United States born 1890 to 1990. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016. Apr;18 Suppl 1:S16–29. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tammemagi MC, Katki HA, Hocking WG, et al. Selection criteria for lung-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2013. Feb 21;368(8):728–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katki HA, Kovalchik SA, Petito LC, et al. Implications of nine risk prediction models for selecting ever-smokers for computed tomography lung cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2018. Jul 3;169(1):10–9. doi: 10.7326/m17-2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bach PB, Kattan MW, Thornquist MD, et al. Variations in lung cancer risk among smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003. Mar 19;95(6):470–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ten Haaf K, Jeon J, Tammemagi MC, et al. Risk prediction models for selection of lung cancer screening candidates: a retrospective validation study. PLoS Med. 2017. Apr;14(4):e1002277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: lung cancer screening. Version 2. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/lung_screening.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.ten Haaf K, Bastani M, Cao P, et al. A Comparative Modeling Analysis of Risk-Based Lung Cancer Screening Strategies. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2019;112(5):466–79. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charnes A, Cooper WW, Rhodes E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. European Journal of Operational Research. 1978. 1978/November/01/;2(6):429–44. doi: 10.1016/0377-2217(78)90138-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y, Midthun DE, Wampfler JA, et al. Trends in the proportion of patients with lung cancer meeting screening criteria. JAMA. 2015. Feb 24;313(8):853–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vu C, Lin S, Chang C-F. Gender gaps in care: lung cancer screening criteria in women. Chest. 2019. 2019/October/01/;156(4, Supplement):A407. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han SS, Chow E, Ten Haaf K, et al. Disparities of National Lung Cancer Screening Guidelines in the US Population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020. Nov 1;112(11):1136–42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumar V, Cohen JT, van Klaveren D, et al. Risk-targeted lung cancer screening: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(3):161–9. doi: 10.7326/M17-1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeon J, Holford TR, Levy DT, et al. Smoking and lung cancer mortality in the United States from 2015 to 2065: a comparative modeling approach. Ann Intern Med. 2018. Oct 9doi: 10.7326/M18-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crosbie PA, Balata H, Evison M, et al. Implementing lung cancer screening: baseline results from a community-based 'Lung Health Check' pilot in deprived areas of Manchester. Thorax. 2019. Apr;74(4):405–9. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-211377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field JK, Duffy SW, Baldwin DR, et al. UK Lung Cancer RCT Pilot Screening Trial: baseline findings from the screening arm provide evidence for the potential implementation of lung cancer screening. Thorax. 2016;71(2):161–70. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tammemagi MC. Selecting lung cancer screenees using risk prediction models-where do we go from here. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2018. Jun;7(3):243–53. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.06.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tammemagi MC, Schmidt H, Martel S, et al. Participant selection for lung cancer screening by risk modelling (the Pan-Canadian Early Detection of Lung Cancer [PanCan] study): a single-arm, prospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2017. Nov;18(11):1523–31. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, et al. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020. Aug 13;383(7):640–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joseph AM, Rothman AJ, Almirall D, et al. Lung cancer screening and smoking cessation clinical trials. SCALE (Smoking Cessation within the Context of Lung Cancer Screening) collaboration. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018. Jan 15;197(2):172–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201705-0909CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kathuria H, Detterbeck FC, Fathi JT, et al. Stakeholder research priorities for smoking cessation interventions within lung cancer screening programs. An official American Thoracic Society research statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017. Nov 1;196(9):1202–12. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201709-1858ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao P, Jeon J, Levy DT, et al. Potential impact of cessation interventions at the point of lung cancer screening on lung cancer and overall mortality in the United States. J Thorac Oncol. 2020. Jul;15(7):1160–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.