Abstract

Biphenyl dioxygenase from Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) sp. strain LB400 catalyzes the first reaction of a pathway for the degradation of biphenyl and a broad range of chlorinated biphenyls (CBs). The effect of chlorine substituents on catalysis was determined by measuring the specific activity of the enzyme with biphenyl and 18 congeners. The catalytic oxygenase component was purified and incubated with individual CBs in the presence of electron transport proteins and cofactors that were required for enzyme activity. The rate of depletion of biphenyl from the assay mixture and the rate of formation of cis-biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol, the oxidation product, were almost equal, indicating that the assay accurately measured enzyme-specific activity. Four classes of CBs were defined based on their oxidation rates. Class I contained 3-CB and 2,5-CB, which gave rates that were approximately twice that of biphenyl. Class II contained 2,5,3′,4′-CB, 2,3,2′,5′-CB, 2,3,4,5-CB, 2,3,2′,3′-CB, 2,4,5,2′,5′-CB, 2,5,3′-CB, 2,5,4′-CB, 2-CB, and 3,4,5-CB, which gave rates that ranged from 97 to 35% of the biphenyl rate. Class III contained only 2,3,4,2′,5′-CB, which gave a rate that was 4% of the biphenyl rate. Class IV contained 2,4,4′-CB, 2,4,2′,4′-CB, 3,4,5,2′-CB, 3,4,5,3′-CB, 3,5,3′,5′-CB, and 3,4,5,2′,5′-CB, which showed no detectable depletion. Rates were not significantly correlated with the aqueous solubilities of the CBs or the number of chlorine substituents on the rings. Oxidation products were detected for all class I, II, and III congeners and were identified as chlorinated cis-dihydrodiols for classes I and II. The specificity of biphenyl dioxygenase for the CBs examined in this study was determined by the relative positions of the chlorine substituents on the aromatic rings rather than the number of chlorine substituents on the rings.

Chlorinated biphenyls (CBs) are widely dispersed environmental pollutants that have accumulated in sediment and soil as well as in the fatty tissues of humans and wildlife (35). Their presence is a cause for concern because they are suspected of having adverse effects on the human reproductive, endocrine, neural, and immune systems (33). CBs and related chlorinated aromatic compounds, such as 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethane (DDT) and 2,4,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzodioxin, are also suspected of interfering with reproduction and development of wildlife chronically exposed to contaminated water, sediment, and food (23, 32, 35). The high cost and public opposition to current physical remediation technologies have stimulated interest in the use of microorganisms for bioremediation of CB-contaminated sites (25, 43, 46). Since the demonstration that two strains of Achromobacter could degrade mono- and dichlorobiphenyls by Ahmed and Focht (1), numerous studies have shown that a broad diversity of bacteria have the ability to degrade many of the different CB congeners that contaminate the environment (3, 16, 24, 39). While natural microbial degradation of CBs is constrained by a combination of physical, chemical, and biological factors (25), development of effective bioremediation strategies will be aided by an understanding of the biochemical mechanisms involved in the mineralization of CBs.

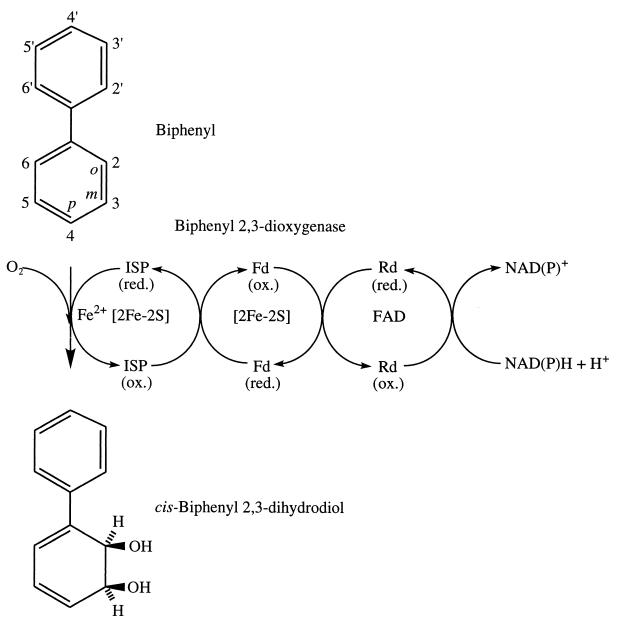

Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) sp. strain LB400 (47) grows on biphenyl and cooxidizes an exceptionally broad range of CBs (3, 8). The initial reaction in aerobic degradation of biphenyl and CBs is catalyzed by biphenyl dioxygenase (Fig. 1). The enzyme contains three protein components: reductaseBPH, ferredoxinBPH, and an iron-sulfur protein (ISPBPH). ReductaseBPH and ferredoxinBPH form a short electron transport chain for the transfer of two electrons from NAD(P)H to ISPBPH, the terminal oxygenase component that catalyzes the addition of molecular oxygen at positions 2 and 3 of biphenyl to produce cis-(2R,3S)-dihydroxy-1-phenylcyclohexa-4,6-diene (cis-biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol) and NAD(P)+ (18, 21). All three components have been purified to homogeneity from the soluble fraction of cell extracts of strain LB400 (10, 19, 22) and as histidine-tagged fusion proteins from recombinant strains of Escherichia coli expressing the bph genes of Comamonas testosteroni B-356 (26, 27). The subsequent reactions of the pathway are catalyzed by enzymes that transform cis-biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol into benzoate and Krebs cycle intermediates which support growth (1, 2, 11, 12, 40).

FIG. 1.

Reaction catalyzed by biphenyl dioxygenase. Numbered carbon atoms correspond to locations where chlorine may substitute for hydrogen (not shown) of chlorinated biphenyls; o, m, and p denote the ortho, meta, and para positions, respectively. Enzyme cofactors and redox centers are shown for each protein component. Abbreviations: ISP, iron sulfur protein; Fd, ferredoxin; Rd, reductase; red., reduced; ox., oxidized.

The broad specificity of the LB400 biphenyl dioxygenase for CBs is due to the relaxed regiospecificity for the position where molecular oxygen is added to the aromatic ring and to the ability to catalyze the addition of molecular oxygen at ortho-chlorinated positions. The latter activity produces an unstable intermediate that rearomatizes by spontaneous elimination of the chlorine substituent from the ring (20, 41). However, 4,4′-dichlorobiphenyl, a potential substrate having four unchlorinated positions (at positions 2 and 3), is a poor substrate for degradation by LB400, while 2,4,4′-CB and 2,4,2′,4′-CB are better substrates (14, 17). This variability in degradation of CBs by strain LB400 suggests that the substrate specificity of biphenyl dioxygenase is affected by factors in addition to the steric hindrance created by chlorine substituents which have van der Waals radii larger than that of hydrogen (7). However, structure-activity relationships are not apparent, in part because the use of complex mixtures of congeners, long incubation times, and intact cells in previous studies has not allowed oxidation rates to be adequately compared among CBs having different chlorination patterns. Thus, little is known about the effects of chlorine substituents on the rate of the oxidation reaction catalyzed by biphenyl dioxygenase. Here, we report the effect of chlorine substituents on the rate of oxidation of 18 CBs by biphenyl dioxygenase of Burkholderia sp. strain LB400. We were particularly interested in examining congeners having chlorine substituents at positions 2 and 5 because addition of molecular oxygen to a ring with this pattern is unique to strain LB400 and a few other described strains that possess a dioxygenase capable of catalyzing 3,4-dioxygenation in addition to 2,3-dioxygenation (3).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and growth conditions.

Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 was provided by H. Finkbeiner (General Electric Co., Schenectady, N.Y.). The organism was grown aerobically on a mineral salts medium (45) supplemented with 0.5% biphenyl as the sole carbon source. Cells were harvested at the end of the log phase of growth, washed twice with 2 culture volumes of 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and resuspended in BEG buffer [50 mM bis(2-hydroxyethyl)imino-tris(hydroxymethyl)methane [Bis-Tris] buffer (pH 7.0), containing 5% (vol/vol) ethanol and 5% (vol/vol) glycerol] at a ratio of 1 g of cell paste to 1 ml of buffer and stored at −75°C. Sphingomonas (Beijerinckia) yanoikuyae B8/36 (18, 30) was obtained from D. T. Gibson (The University of Iowa, Iowa City).

Protein purification.

Cell extract was prepared, ISPBPH was purified, and reductaseBPH was partially purified, as described previously (19, 21), from 120 ml of cell extract (3.3 g of protein). FerredoxinBPH was further purified to remove traces of cis-biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol dehydrogenase activity by the addition of ammonium sulfate to a 2.4 M concentration and removal of the precipitate by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was concentrated by ultrafiltration and applied to a 2.6- by 60-cm S-300 gel filtration column equilibrated with BEG buffer. Protein was eluted from the column with BEG buffer at a flow rate of 4 ml min−1. Fractions containing ferredoxinBPH were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration, and stored at −75°C until use. Protein purity was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis by the method of Laemmli (31). Isolated protein components were stored at −75°C until use. Protein concentration was determined by the method of Bradford (9), with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

CB oxidation rate and detection of products.

Assays were carried out in 4-ml amber vials sealed with Teflon-lined screw-on caps. Each reaction mixture contained 500 μg of pure ISPBPH, 100 μg each of the partially purified reductaseBPH and ferredoxinBPH, 800 μM ferrous ammonium sulfate, 2 mM NADPH, and 0.5% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 in morpholineethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer, pH 6.0. The final concentration of MES was 32 mM, and the total assay volume was 0.5 ml. The reaction was initiated by addition of the CB substrate (dissolved in 10 μl of acetone) to a final concentration of 500 μM. Each CB was assayed individually in duplicate reactions, and depletion rates were calculated from the slope obtained by linear regression analysis, with inclusion of the zero time point and two additional time points. Negative control reaction mixtures contained all of the assay components except NADPH. Each reaction mixture was shaken at 250 rpm (30°C) for the appropriate time interval, and each reaction was stopped by the addition of 1 ml of NaOH-washed ethyl acetate. The vials were then shaken overnight at room temperature, and 20 μl of the organic phases was analyzed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). The amount of CB remaining in the assay mixture was quantified by use of a standard curve relating the peak area at 254 nm to known amounts of the substrate. Time points showing a linear decrease in concentration with time (i.e., 5 [class I], 10 [class II], and 60 min [class III]) were fitted to a straight line by linear regression analysis, and substrate depletion rates (in nanomoles of CB oxidized per minute per milligram of ISPBPH) were calculated. The organic phases of the extracts for each CB were then pooled and dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the solvent was removed by evaporation with a stream of N2. The residue was dissolved in 200 μl of methanol and analyzed for oxidation products by HPLC.

HPLC.

HPLC was performed on a Beckman System Gold model 125 solvent module equipped with a Beckman model 168 photodiode array detector. Twenty microliters of extract or standard was injected onto a Beckman Ultrasphere C18 reverse-phase column (4.6 mm by 25 cm) equilibrated with water-methanol (50/50). Compounds were eluted with a linear gradient to 95% methanol in 20 min at 1 ml min−1 and held at 95% methanol for 10 min. The spectrum of the effluent was scanned from 190 to 500 nm, and eluting peaks were detected at 254 nm.

GC-MS.

CB oxidation products were purified by HPLC prior to analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The isolated products were collected as they were eluted from the HPLC column, and they were dried with a stream of N2 and derivatized overnight at 65°C with 1 mg of methylboronic acid. The 2,5,3′4′-CB oxidation product was derivatized with n-butylboronic acid. One to five microliters of the derivatives was injected, using a split ratio of 50:1, onto a 0.2 mm- by 25-m capillary column with a 0.33-μm-thick film of cross-linked dimethylpolysiloxane (Hewlett-Packard, Avondale, Pa.). The column carrier gas was helium at a flow rate 0.45 ml min−1. The injection port temperature was 225°C, and the column temperature was held at 150°C for 6 min, followed by an increase to 275°C at 10°C min−1. Mass spectra were obtained with a Hewlett-Packard model 5970 mass selective detector by electron impact ionization. The ionizing voltage was 70 eV, and the source temperature was 280°C. The number of chlorine substituents present on the molecules was determined from the mass spectrum by comparing the relative intensities of the molecular ions containing 35Cl and 37Cl isotopes (44).

Chemicals.

Chlorinated biphenyls were purchased from Ultra Scientific (North Kingston, R.I.) or EM Science (Gibbstown, N.J.) and had a purity of 97 to 99%. cis-Biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol was produced for use as an analytical HPLC standard using S. yanoikuyae B8/36 (18). The organism was grown in 0.25 liters of mineral salts medium containing 0.2% succinate at 30°C and 200 rpm. Biphenyl (0.5% [wt/vol]) was added at mid-log phase, and the culture was incubated until the end of log phase (optical density at 600 nm = 2). The culture was filtered through glass wool to remove solid biphenyl and extracted with 3 volumes of NaOH-washed ethyl acetate. The organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and the solvent was removed by rotary vacuum evaporation. The remaining residue was dissolved in acetone and purified by preparative thin-layer chromatography as described previously (20). Purity was confirmed by HPLC, and the concentration of cis-biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol was determined by absorbance spectrophotomery in methanol at 303 nm using an extinction coefficient of 13.6 mM−1 cm−1 (18).

Statistical analysis.

Linear regression and other statistical tests were performed using the Prism version 2.0 computer software program (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.). The relationships between CB oxidation rate and solubility or the number of chlorine substituents of the CBs were analyzed with the Spearman rank correlation routine. CBs of class IV which showed oxidation rates below the limit of detection of the depletion assay were excluded from correlation analyses. CB solubility values were those reported by Dunnivant et al. (13).

RESULTS

The three protein components of biphenyl dioxygenase of Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 were isolated from the soluble fraction of cell extracts and were combined to reconstitute catalytic activity in depletion assays designed to measure the initial velocity of CB oxidation. The assay was validated by comparing the biphenyl depletion rate with the cis-biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol formation rate in the same reaction mixture. The rates were 84.6 ± 6.7 nmol of biphenyl min−1 mg of ISPBPH−1 and 94.8 ± 7.9 nmol of cis-biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol min−1 mg of ISPBPH−1 in the reconstituted system (values are means ± standard errors of the means). These rates are close to the value of 91.5 nmol of cis-[14C]biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol min−1 mg of ISPBPH−1 obtained in a previous study (19). Reaction mixtures without ISPBPH, electron transport components, or NADPH showed no activity.

The depletion of CBs was linear for the first 5, 10, and 60 min of incubation for class I, II, and III congeners, respectively, as determined by the P values of the runs tests of the residuals and the goodness-of-fit (r2) of the linear regression analyses. Oxidation rates for the CBs varied over a range of undetectable (less than 3 nmol min−1 mg of ISPBPH−1) for six of the substrates to approximately twice the biphenyl depletion rate (182 nmol min−1 mg of ISPBPH−1) for 3-CB (Table 1). Products were detected by HPLC for all CBs with detectable oxidation rates, and all but one of the products were identified as chlorinated cis-dihydrodiols by GC-MS. The positions of the hydroxyl groups could not be determined because the small scale of the assays and short incubation times did not produce amounts of the products that were sufficient for additional analyses such as 1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry (20). Based on these data the CBs could be grouped into four classes. Class I contained congeners that were oxidized more rapidly than biphenyl and contained 3-CB and 2,5-CB; both were oxidized approximately twice as rapidly as biphenyl. Class II contained congeners with oxidation rates that were similar to that of biphenyl and included (ranked by rate in decreasing order) 2,5,3′,4′-CB, 2,3,2′,5′-CB, 2,3,4,5-CB, 2,3,2′,3′-CB, 2,4,5,2′,5′-CB, 2,5,3′-CB, 2,5,4′-CB, 2-CB, and 3,4,5-CB. Enzyme activity with these congeners varied from approximately 97 to 35% of the oxidation rate of biphenyl. Class III contained 2,3,4,2′,5′-CB, which had an oxidation rate less than 5% of that of biphenyl. Class IV included 2,4,4′-CB, 2,4,2′,4′-CB, 3,4,5,2′-CB, 3,4,5,3′-CB, 3,5,3′,5′-CB, and 3,4,5,2′,5′-CB. Depletion of these substrates was not detected during 60 min of incubation.

TABLE 1.

Rates of oxidation of chlorinated biphenyls by biphenyl dioxygenase

| Congener | Avg oxidation rate (nmol/min/mg of ISPBPH) | Relative rate | Class | Result of:

|

Product type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC analysis

|

GC-MS analysis

|

|||||||

| Retention time (min) | Absorbance maximum (nm) | Mol wtd | No. of Cl substituents | |||||

| 3-CB | 182 (11) | 210 | I | 4.5 | 308 | 288ef | 2 | 2′,3′-Dihydrodiolh |

| 2,5-CB | 169 (18) | 200 | I | 13.1 | 294 | 322ef | 2 | Dihydrodiol |

| 14.1c | 284 | 322ef | 2 | 2′,3′-Dihydrodiolh | ||||

| Biphenyl | 84.6 (6.7) | 100 | II | 8.8 | 304 | 212 | 0 | 2,3-Dihydrodiol |

| 2,5,3′,4′-CB | 82.4 (5.9) | 97 | II | 18.8 | 294 | 348 | 4 | Dihydrodiol |

| 2,3,2′,5′-CB | 74.6 (4.4) | 88 | II | 17.0c | 284 | 348 | 4 | Dihydrodiol |

| 17.5 | 278 | 348 | 4 | Dihydrodiol | ||||

| 2,3,4,5-CB | 71.4 (4.2) | 84 | II | 20.2 | 284 | 390f | 4 | Dihydrodiol |

| 2,3,2′,3′-CB | 55.4 (5.1) | 65 | II | 16.9c | 276 | 348 | 4 | Dihydrodiol |

| 17.8 | 282 | 348 | 4 | Dihydrodiol | ||||

| 2,4,5,2′,5′-CB | 54.0 (2.7) | 64 | II | 20.7 | 290 | 382 | 5 | Dihydrodiol |

| 2,5,3′-CB | 51.4 (3.9) | 61 | II | 16.1 | 292 | 356ef | 3 | Dihydrodiol |

| 17.1c | 280 | 356ef | 3 | Dihydrodiol | ||||

| 17.6 | 284 | 356ef | 3 | Dihydrodiol | ||||

| 2,5,4′-CB | 50.0 (2.2) | 59 | II | 16.4 | 294 | 314 | 3 | Dihydrodiol |

| 2-CB | 48.8 (6.6) | 58 | II | 10.5 | 280 | 288ef | 1 | 2′,3′-Dihydrodiolh |

| 3,4,5-CB | 29.8 (1.3) | 35 | II | 18.3 | 310 | 314 | 3 | Dihydrodiol |

| 2,3,4,2′,5′-CB | 3.3 (0.3) | 3.9 | III | 20.2 | 285 | —g | — | — |

| 2,4,4′-CB | NDb | IV | ND | |||||

| 2,4,2′,4′-CB | ND | IV | ND | |||||

| 3,4,5,2′-CB | ND | IV | ND | |||||

| 3,4,5,3′-CB | ND | IV | ND | |||||

| 3,5,3′,5′-CB | ND | IV | ND | |||||

| 3,4,5,2′,5′-CB | ND | IV | ND | |||||

Values in parentheses are standard errors of the means.

ND, activity or products not detected.

Major product.

Molecular weight of the methylboronate derivative, unless otherwise noted.

Determined previously (20).

Butylboronate derivative.

—, not determined.

Positions of hydroxyl groups determined previously by 1H NMR (20).

A single oxidation product was detected by HPLC analysis of the reaction mixtures incubated with nine CBs, while two products were detected from three CBs and three products were detected from one CB each of classes I, II, and III. No products were detected for class IV CBs. The absorbance maxima of the products ranged from 276 to 310 nm, suggesting that they were cis-dihydrodiols formed by the addition of both atoms of molecular oxygen to one of the rings (18, 20, 41). The products of class II were purified by HPLC, and the boronate derivatives were prepared and analyzed by GC-MS. Formation of boronate derivatives requires the presence of two vicinal cis-oriented hydroxyl groups. All products gave m/z ratios for their molecular ions that were equal to the calculated molecular weight of derivatized cis-dihydrodiols. In addition, the relative intensities of the isotopic molecular ions showed that the products had the same number of chlorine substituents as the parent CBs. These data show that none of the products were catechols produced by spontaneous elimination of HCl as a result of oxygenation of a chlorinated ortho carbon (20). GC-MS analyses of the oxidation products of 2-CB, 3-CB, 2,5-CB, and 2,5,3′-CB were not performed in this study, as they have been identified previously as cis-dihydrodiols (20), but the data are included for comparative purposes. The oxidation product of 2,3,4,2′,5′-CB was not analyzed by GC-MS due to the small amount of compound that was produced; however, the HPLC retention time and UV spectrum were similar to those of the cis-dihydrodiol product of 2,4,5,2′,5′-CB, suggesting that the former product was also a cis-dihydrodiol. Products were not detected for any CBs in control reaction mixtures containing all of the assay components except NADPH.

DISCUSSION

The specificity of biphenyl dioxygenase for oxidation of CBs was determined by comparing the rates of depletion of biphenyl and 18 congeners containing one to five chlorine substituents. The rates of depletion of biphenyl and cis-biphenyl 2,3-dihydrodiol formation were linear and almost equal for the first 10 min of incubation. This indicates that depletion of the substrate from the assay buffer was due to biphenyl dioxygenase activity rather than to nonspecific losses such as compound volatility or adsorption to the glass vial. The initial concentration of each substrate in the assay buffer was 500 μM. This concentration was chosen because preliminary assays with biphenyl showed that increasing the concentration to 1,000 μM did not increase the rate of biphenyl depletion, while lowering the concentration to 100 μM resulted in a rate that was 37% of the rate determined with 500 μM biphenyl. The apparent Km of the biphenyl dioxygenase of LB400 for biphenyl has been reported to be 103 μM (28).

Biphenyl and CBs are hydrophobic compounds with aqueous solubilities that may be below that required to saturate the active site of the enzyme. Triton X-100 (TX-100) was included in the assay buffer to increase the availability of the substrates to the enzyme and minimize effects of substrate solubility on enzyme activity. The rate and extent of oxidation of 2,5,2′-CB by biphenyl dioxygenase of LB400 were increased when TX-100 was included in the transformation reaction (J. Haddock, unpublished data). TX-100 caused a slight decrease in the rate of oxidation of biphenyl, but the effects of this nonionic detergent on enzyme activity would be expected to be the same in all congener assays. Statistical analysis showed that the oxidation rates were not significantly correlated to CB solubility (r2 = 0.0937; P = 0.3331, α = 0.05). For example, 2,5,3′,4′-CB has an aqueous solubility of 0.038 μM (13), which is 1,260 times lower than that of biphenyl, but this congener showed an oxidation rate that was almost equal to that of biphenyl. 2-CB has a solubility only slightly less than that of biphenyl (30 and 48 μM, respectively [13, 34]), but the oxidation rate was nearly half that of biphenyl. Therefore, variation in the initial oxidation rates among the CBs was most likely due to the influence of the chlorine substituents on the reaction catalyzed by the enzyme and not to the availability of the substrate.

The number of chlorine substituents was not significantly correlated with CB oxidation rate (r2 = 0.1194; P = 0.2474, α = 0.05). Using as examples the same two congeners discussed above, 2,5,3′,4′-CB has four chlorine substituents, while 2-CB has only one, but both were oxidized at rates that were similar to those of biphenyl and 2,4,5,2′,5′-CB, a pentachlorinated congener. These results are in contrast to the general observation that degradation of CBs by many bacterial isolates is inhibited as the number of chlorine substituents increases (3, 15). Several studies have demonstrated that LB400 and a few other isolates have an exceptional ability to degrade CBs containing up to six chlorine substituents (3, 4, 6, 8, 14, 17, 36–38). Other studies have shown that the ability of LB400 to degrade a broad range of CBs is due to the ability of the enzymes of the upper biphenyl degradation pathway to tolerate the presence of multiple chlorine substituents, resulting in transformation of the congeners to chlorinated phenylhexadienoates and benzoates (40). However, the CBs examined in this study were not randomly selected and the lack of a significant effect of chlorine number cannot be generalized to include all 209 congeners.

The purified biphenyl dioxygenase of LB400 catalyzes the initial oxidation reaction of a broad range of CBs (20), but precise structure-activity relationships between specific activity of the enzyme and the chlorination pattern of the substrate have not been examined. Thus, the CBs were placed into four different classes based on their oxidation rates in an attempt to identify common chlorination patterns that affected enzyme activity. It is interesting that two congeners gave higher rates than biphenyl, presumed to be the natural substrate of the enzyme. To our knowledge, CBs that are better substrates than biphenyl have not been identified for whole cells, cell extracts, or purified enzymes of any CB-degrading bacterium. These congeners were placed into class I; both contain an unchlorinated ring and only one meta chlorine on the unoxidized ring (20). The meta chlorine of 2,5-CB appears to be responsible for the enhanced rate, as 2-CB was oxidized at a rate that was about half that of biphenyl. The major oxidation products of the class I congeners have been shown to contain the hydroxyl groups on the unchlorinated ring (20). The class I congeners show that chlorine substituents on the ring that is not oxidized increased the oxidation rate, while 2-CB, 3,4,5-CB, and 2,3,4,5-CB of class II, which are also likely oxidized on the unchlorinated ring (20, 42), inhibited the rate to varying degrees. Bedard and Haberl (2) have also observed effects of chlorine substituents of the unoxidized ring on the reactivity of CBs by LB400.

Nine of the CBs were placed into class II because they had oxidation rates that were similar to that of biphenyl. The five best substrates in class II were tetra- and pentachlorinated, while the one monochlorinated and three trichlorinated CBs had somewhat lower oxidation rates. All but one congener of this class contain one or two ortho chlorines, and four of the congeners have a pattern of substitution at positions 2 and 5 on one ring. Thus, ortho chlorines did not have a large negative influence on the oxidation rate of these congeners. The detection of two cis-dihydrodiols from 2,3,2′,3′-CB is of interest, as this suggests that one of the products would have resulted from a 4,5-dioxygenation reaction.

2,3,4,2′,5′-CB was placed into class III because its oxidation rate was much lower than those of the CBs of class II. A product was detected by HPLC, indicating that the depletion was due to enzymatic activity, but the amount produced was judged to be insufficient for further analysis by GC-MS. The only difference in the chlorination pattern between this substrate and 2,4,5,2′,5′-CB of class II is the position of the meta chlorine on the trichlorinated ring, which was not likely the ring where oxidation occurred. This suggests that a 2,4,5-chlorination pattern may be preferred over a 2,3,4-chlorination pattern on the unoxidized ring. 2,4,5,2′,4′,5′-CB has also been shown to be degraded by LB400; however, the hypothetical dechlorinated oxidation product(s) has not been conclusively identified (3, 8, 14, 17).

Six of the CBs were placed into class IV because they showed no depletion greater than that of negative control reaction mixtures lacking NADPH and no products were detected by HPLC analysis. Four of the class IV congeners had chlorine substituents at both meta positions of one ring and one or two chlorines on the second ring. The effect of chlorine substituents at these positions was also evident when the oxidation rates of 2,4,5,2′,5′-CB (class II) and 3,4,5,2′,5′-CB (class IV) were compared; the change of one chlorine substituent from an ortho to a meta position eliminated detectable activity. 3,5,3′,5′-CB was used as a nondegradable internal standard in a study that compared the ability of LB400 and seven other bacteria to degrade di- and trichlorobiphenyls (2), while Joshi and Walia (29) have shown that several isolates of C. testosteroni can attack some congeners with a double meta-chlorinated ring. The other two congeners in class IV had chlorines at the para positions of both rings, a substitution pattern that has been shown to be a characteristic of poor CB substrates for LB400. While no products or enzyme activity were detected for these two congeners during the short incubation times used in this study, Seeger et al. (42) have detected metabolites after prolonged incubation of 2,4,4′-CB and 2,4,2′,4′-CB with high cell densities of recombinant strains of E. coli that overexpressed some of the bph genes of LB400. Oxidation products of 2,4,4′-CB have also been detected using whole LB400 cells (2). Our failure to detect oxidation of these substrates using purified enzyme components may have been due to the inability of the assay to detect very low oxidation rates or to the formation of undetectable oxidation products that inhibited enzyme activity. Clearly, if the congeners of class IV are oxidized by the enzyme, they are much poorer substrates than those of classes I and II and are also distinguishable from the class III congener which did show a detectable oxidation rate and product.

Billingsley et al. (6) determined rate constants for depletion of several congeners of commercial mixtures of polychlorinated biphenyls (Aroclors) by LB400 in a resting cell assay. Five congeners were common to the study reported here and were among those with the highest rate constants for depletion by the resting cells. These congeners were placed into class II in our study. Inhibition by other congeners in the Aroclors mixture was noted and precludes direct comparisons with our results using single CBs where competitive inhibition was not a factor. Billingsley et al. (5) measured depletion rates of three CBs individually using resting LB400 cells and found that the rate for 2,4,5,2′,5′-CB was only approximately 1.6 times greater than that for 2,4,2′,4′-CB. These two congeners were placed in classes II and IV, respectively, after being tested with purified biphenyl dioxygenase in our study. The presence in LB400 cells of a second biphenyl dioxygenase that has low activity towards congeners containing two para chlorines was considered by Billingsley et al. (5). However, studies with recombinant E. coli strains containing the cloned bphAEFG genes which encode the biphenyl dioxygenase components of LB400 have demonstrated oxidation of congeners with two para chlorines (14, 36, 37, 42). Thus, discovering the reasons for the different results obtained for whole cells and the purified dioxygenase will require additional experiments.

The results of this study support the hypothesis that the position rather than the number of chlorine substituents on the rings has a greater influence on the rate of oxidation of CBs by the biphenyl dioxygenase of LB400. The electronic effects of the chlorination pattern rather than steric effects of the chlorine substituents may be the most influential factor affecting the ability of the biphenyl dioxygenase of LB400 to oxidize CBs. The simultaneous presence of ortho, meta, and para chlorine substituents on both rings does not completely prevent degradation because 2,4,5,2′,4′,5′-CB is attacked by LB400 (3, 8). In addition, the presence of chlorine substituents at all but one position of a single ring does not greatly affect activity, as seen for 2,3,4,5-CB in this study and for 2,3,4,5,2′-CB previously (42). A full understanding of the influence of chlorine substituents on the ability of biphenyl dioxygenase to bind and oxidize CBs will require studies with additional congeners and determination of the enzyme's structure and reaction mechanism. Rational design of bacterial strains for efficient bioremediation of CBs and other chlorinated organic pollutants in the environment may then become possible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Office for Research Development and Administration, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale, and the APS Project of the Illinois Board of Higher Education.

We thank M. T. Madigan (Southern Illinois University) for comments on the manuscript and D. T. Gibson (The University of Iowa) for assistance with the GC-MS analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed M, Focht D D. Degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by two species of Achromobacter. Can J Microbiol. 1973;19:47–52. doi: 10.1139/m73-007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bedard D L, Haberl M L. Influence of chlorine substitution pattern on the degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by eight bacterial strains. Microb Ecol. 1990;20:87–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02543870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedard D L, Unterman R, Bopp L H, Brennan M J, Haberl M L, Johnson C. Rapid assay for screening and characterizing microorganisms for the ability to degrade polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:761–768. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.4.761-768.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedard D L, Wagner R E, Brennan M J, Haberl M L, Brown J F., Jr Extensive degradation of Aroclors and environmentally transformed polychlorinated biphenyls by Alcaligenes eutrophus H850. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1094–1102. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.5.1094-1102.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Billingsley K A, Backus S M, Ward O P. Studies on the transformation of selected polychlorinated biphenyl congeners by Pseudomonas strain LB400. Can J Microbiol. 1997;43:782–788. doi: 10.1139/m97-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billingsley K A, Backus S M, Juneson C, Ward O P. Comparison of the degradation patterns of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners in Aroclors by a Pseudomonas strain LB400 after growth on various carbon sources. Can J Microbiol. 1997;43:1172–1179. doi: 10.1139/m97-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bondi A. van der Waals volumes and radii. J Phys Chem. 1964;68:441–451. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bopp L H. Degradation of highly chlorinated PCBs by Pseudomonas strain LB400. J Ind Microbiol. 1986;1:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broadus R M, Haddock J D. Purification and characterization of the NADH:ferredoxinBPH oxidoreductase component of biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. Arch Microbiol. 1998;170:106–112. doi: 10.1007/s002030050621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrington B, Lowe A, Shaw L E, Williams P A. The lower pathway operon for benzoate catabolism in biphenyl-utilizing Pseudomonas sp. strain IC and the nucleotide sequence of the bphE gene for catechol 2,3-dioxygenase. Microbiology. 1994;140:499–508. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-3-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catelani D, Colombi A, Sorlini C, Treccani V. Metabolism of biphenyl 2-Hydroxy-6-oxo-6-phenylhexa-2,4-dienoate: the meta-cleavage product from 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl by Pseudomonas putida. Biochem J. 1973;134:1063–1066. doi: 10.1042/bj1341063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunnivant F M, Elzerman A W, Jurs P C, Hasan M N. Quantitative structure-property relationships for aqueous solubilities and Henry's Law constants of polychlorinated biphenyls. Environ Sci Technol. 1992;26:1567–1573. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erickson B D, Mondello F J. Enhanced biodegradation of polychlorinated biphenyls after site-directed mutagenesis of a biphenyl dioxygenase gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3858–3862. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3858-3862.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furukawa K. Microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) In: Chakrabarty A M, editor. Biodegradation and detoxification of environmental pollutants. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1982. pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furukawa K, Tonomura K, Kamibayashi A. Effect of chlorine substitution on the biodegradability of polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1978;35:223–227. doi: 10.1128/aem.35.2.223-227.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson D T, Cruden D L, Haddock J D, Zylstra G J, Brand J M. Oxidation of polychlorinated biphenyls by Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400 and Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:4561–4564. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.14.4561-4564.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gibson D T, Roberts R L, Wells M C, Kobal V M. Oxidation of biphenyl by a Beijerinckia species. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;50:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)90828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haddock J D, Gibson D T. Purification and characterization of the oxygenase component of biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5834–5839. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5834-5839.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddock J D, Horton J R, Gibson D T. Dihydroxylation and dechlorination of chlorinated biphenyls by purified biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:20–26. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.20-26.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haddock J D, Nadim L M, Gibson D T. Oxidation of biphenyl by a multicomponent enzyme system from Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:395–400. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.2.395-400.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haddock J D, Pelletier D A, Gibson D T. Purification and properties of ferredoxinBPH, a component of biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase of Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;19:355–359. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.2900429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heaton S N, Bursian S J, Giesy J P, Tillit D E, Render J A, Jones P D, Verbrugge D A, Kubiak T J, Aulerich R J. Dietary exposure of mink to carp from Saginaw Bay, Michigan. 1. Effects on reproduction and survival, and the potential risks to wild mink populations. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1995;28:334–343. doi: 10.1007/BF00213111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernandez B S, Arensdorf J J, Focht D D. Catabolic characteristics of biphenyl-utilizing isolates which cometabolize PCBs. Biodegradation. 1995;6:75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hooper S W, Pettigrew C A, Sayler G S. Ecological fate, effects and prospects for the elimination of environmental polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) Environ Toxicol Chem. 1990;9:655–667. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurtubise Y, Barriault D, Powlowski J, Sylvestre M. Purification and characterization of the Comamonas testosteroni B-356 biphenyl dioxygenase components. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6610–6618. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6610-6618.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurtubise Y, Barriault D, Sylvestre M. Characterization of active recombinant his-tagged oxygenase component of Comamonas testosteroni B-356 biphenyl dioxygenase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8152–8156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.8152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurtubise Y, Barriault D, Sylvestre M. Involvement of the terminal oxygenase β-subunit in the biphenyl dioxygenase reactivity pattern toward chlorobiphenyls. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5828–5835. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.22.5828-5835.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joshi B, Walia S. Characterization by arbitrary primer polymerase chain reaction of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB)-degrading strains of Comamonas testosteroni isolated from PCB-contaminated soil. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:612–619. doi: 10.1139/m95-081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan A A, Wang R-F, Cao W-W, Franklin W, Cerneglia C E. Reclassification of a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-metabolizing bacterium, Beijerinckia sp. strain B1, as Sphingomonas yanoikuyae by fatty acid analysis, protein pattern analysis, DNA-DNA hybridization, and 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:466–469. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-2-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeBlanc G A. Are environmental sentinels signaling? Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103:888–890. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lindstrom G, Hooper K, Petreas M, Stephens R, Gilman A. Workshop on perinatal exposure to dioxin-like compounds. I. Summary. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(Suppl. 2):135–142. doi: 10.1289/ehp.103-1518837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mackay D, Mascarenhas R, Shiu W Y. Aqueous solubility of polychlorinated biphenyls. Chemosphere. 1980;9:257–264. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFarland V A, Clarke J U. Environmental occurrence, abundance, and potential toxicity of polychlorinated biphenyl congeners: considerations for a congener-specific analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 1989;81:225–239. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8981225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mondello F J. Cloning and expression in Escherichia coli of Pseudomonas strain LB400 genes encoding polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1725–1732. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1725-1732.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mondello F J, Turich M P, Lobos J H, Erickson B D. Identification and modification of biphenyl dioxygenase sequences that determine the specificity of polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3096–3103. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3096-3103.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nadim L M, Schocken M J, Higson F K, Gibson D T, Bedard D L, Bopp L H, Mondello F J. Proceedings of the 13th annual research symposium on land disposal, remedial action, incineration, and treatment of hazardous waste. EPA/600/9-87/015. Cincinnati, Ohio: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 1987. Bacterial oxidation of polychlorinated biphenyls; pp. 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohmori T, Ikai T, Minoda Y, Yamada K. Utilization of polyphenyl and polyphenyl-related compounds by microorganisms. Part 1. Agric Biol Chem. 1973;37:1599–1605. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seeger M, Timmis K N, Hofer B. Conversion of chlorobiphenyls into phenylhexadienoates and benzoates by the enzymes of the upper pathway for polychlorobiphenyl degradation encoded by the bph locus of Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2654–2658. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2654-2658.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seeger M, Timmis K N, Hofer B. Degradation of chlorobiphenyls catalyzed by the bph-encoded biphenyl-2,3-dioxygenase and biphenyl-2,3-dihydrodiol-2,3-dehydrogenase of Pseudomonas sp. LB400. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;133:259–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seeger M, Zielinski M, Timmis K N, Hofer B. Regiospecificity of dioxygenation of di- to pentachlorobiphenyls and their degradation to chlorobenzoates by the bph-encoded catabolic pathway of Burkholderia sp. strain LB400. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3614–3621. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3614-3621.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shannon M J R, Rothmel R, Chunn C D, Unterman R. Evaluating polychlorinated biphenyl bioremediation processes: from laboratory feasibility testing to pilot demonstrations. In: Hinchee R E, Leeson A, Semprini L, Ong S K, editors. Bioremediation of chlorinated and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds. Boca Raton, Fla: Lewis Publishers; 1994. pp. 354–358. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silverstein R M, Bassler G C, Morrill T C. Spectrometric identification of organic compounds. 5th ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stanier R Y, Palleroni N J, Doudoroff M. The aerobic pseudomonads: a taxonomic study. J Gen Microbiol. 1966;43:159–271. doi: 10.1099/00221287-43-2-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unterman R, Bedard D L, Brennan M J, Bopp L H, Mondello F J, Brooks R E, Mobley D P, McDermott J B, Schwartz C C, Dietrich D K. Biological approaches for polychlorinated biphenyl degradation. In: Omenn G S, editor. Environmental biotechnology: reducing risks from environmental chemicals through biotechnology. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1988. pp. 253–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Viallard V, Poirier I, Cournoyer B, Haurat J, Wiebkin S, Ophel-Keller K, Balandreau J. Burkholderia graminis sp. nov., a rhizospheric Burkholderia species, and reassessment of [Pseudomonas] phenazinium, [Pseudomonas] pyrrocinia and [Pseudomonas] glathei as Burkholderia. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:549–563. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-2-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]