Abstract

Propionate consumption was studied in syntrophic batch and chemostat cocultures of Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans and Methanospirillum hungatei. The Gibbs free energy available for the H2-consuming methanogens was <−20 kJ mol of CH4−1 and thus allowed the synthesis of 1/3 mol of ATP per reaction. The Gibbs free energy available for the propionate oxidizer, on the other hand, was usually >−10 kJ mol of propionate−1. Nevertheless, the syntrophic coculture grew in the chemostat at steady-state rates of 0.04 to 0.07 day−1 and produced maximum biomass yields of 2.6 g mol of propionate−1 and 7.6 g mol of CH4−1 for S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei, respectively. The energy efficiency for syntrophic growth of S. fumaroxidans, i.e., the biomass produced per unit of available Gibbs free energy was comparable to a theoretical growth yield of 5 to 12 g mol of ATP−1. However, a lower growth efficiency was observed when sulfate served as an additional electron acceptor, suggesting inefficient energy conservation in the presence of sulfate. The maintenance Gibbs free energy determined from the maintenance coefficient of syntrophically grown S. fumaroxidans was surprisingly low (0.14 kJ h−1 mol of biomass C−1) compared to the theoretical value. On the other hand, the Gibbs free-energy dissipation per mole of biomass C produced was much higher than expected. We conclude that the small Gibbs free energy available in many methanogenic environments is sufficient for syntrophic propionate oxidizers to survive on a Gibbs free energy that is much lower than that theoretically predicted.

Propionate is an important intermediate in the conversion of organic matter to methane and carbon dioxide. In methanogenic environments, the degradation of propionate to acetate and CO2 may account for 6 to 35 mol% of the total methanogenesis (17). Propionate oxidation itself is energetically very unfavorable under standard thermodynamic conditions (see Table 1). Under methanogenic conditions, proton-reducing acetogenic bacteria are only able to gain energy from this reaction when the concentration of products is kept low. Thus, the degradation of propionate is only accomplished in obligate syntrophic consortia of proton-reducing acetogenic bacteria and methanogenic archaea (27, 28, 33). So far, three syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria and some highly purified enrichment cultures have been described (3, 11, 20, 21, 22, 32, 43, 44, 49).

TABLE 1.

Reactions involved in the degradation of propionate and their standard Gibbs free-energy changes, corrected for a pH of 6.9 and a temperature of 37°Ca

| Reaction | Equationb | ΔG0′ (kJ/reaction) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Propionate oxidation | C3H5O2 (aq) + 2H2O (l) → C2H3O2 (aq) + CO2 (g) + 3H2 (g) | +68.4 |

| 2. Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis | 4H2 (g) + CO2 (g) → CH4 (g) + 2H2O (l) | −125.9 |

| 3. Syntrophic oxidation of propionate | C3H5O2 (aq) + 1/2H2O (l) → C2H3O2 (aq) + 3/4(CH4 (g) + 1/4CO2 (g) | −26.0 |

| 4. Sulfidogenic oxidation of propionate | C3H5O2 (aq) + 3/4SO42− (aq) + 3/4H+ → C2H3O2 (aq) + CO2 (g) + 3/4HS− (aq) + H2O (l) | −42.8 |

Temperature correction was made with the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation. The applied ΔHf0 for propionate was −460.2 kJ mol−1, which was calculated as described by Hanselmann (10).

Abbreviations: aq, aqueous; l, liquid; g, gaseous.

Studies have shown that most of the known syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria degrade propionate via the methylmalonyl-coenzyme A (CoA) pathway (14, 25, 43). During the oxidation of propionate in the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway, electrons are released in three reactions, namely, the oxidation of succinate to fumarate, malate to oxaloacetate, and pyruvate to acetyl-CoA (25). In methanogenic environments, the H2 partial pressure is low enough to allow the direct reduction of protons with the electrons released during the oxidation of pyruvate and malate. However, the H2 partial pressure is not sufficient to allow this reduction during the oxidation of succinate to fumarate. It was hypothesized that the electrons released during the oxidation of succinate are shifted to a lower redox potential via reversed electron transport. This transport would be driven by the hydrolysis of 2/3 mol of ATP (27, 28, 37). Some evidence has been obtained for the presence of a reversed electron transport system in syntrophic propionate-degrading bacteria (41). However, the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway yields only 1 mol of ATP via substrate level phosphorylation. Therefore, if such a reversed electron transport is occurring, only 1/3 mol of ATP per mol of propionate is left for growth. Under physiological conditions, the Gibbs free-energy change needed for ATP synthesis must amount to a minimum of 70 kJ mol of ATP−1. Thus, the minimum Gibbs free-energy quantum that can generate 1/3 mol of ATP would amount to approximately −23 kJ mol of propionate−1. It has been suggested that this amount of Gibbs free-energy change corresponds to the minimum energy quantum required to sustain microbial life (27, 28).

In several methanogenic environments, the apparent Gibbs free-energy change for propionate oxidation was on the order of −3 to −15 kJ mol of propionate−1 and thus was rather small (5, 19, 26, 46). This amount of free-energy change is less than the minimum energy quantum needed to sustain microbial life. It is not clear why such small free-energy changes are observed during the degradation of propionate. Most syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria are not obligate syntrophs but are also able to grow on other substrates, such as fumarate, malate, and pyruvate, in the absence of a partner microorganism. A remarkable feature of the propionate-oxidizing Syntrophobacter species is their ability to couple the oxidation of propionate not only to an H2-consuming syntrophic partner but also to the reduction of sulfate. In fact, phylogenetic analysis of Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans has revealed that this bacterium is indeed related to sulfate-reducing bacteria (12). Perhaps the ability to reduce sulfate is of importance to explain the energetics of syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria.

Besides propionate, many alcohols, fatty acids, amino acids, and aromatic compounds are anaerobically degraded by syntrophy. In each case, the available free energy is relatively low and has to be shared between the two syntrophic partners (27, 28). The energetics of syntrophic interspecies H2 transfer has been studied in defined cocultures of benzoate-, lactate-, ethanol-, propionate-, and butyrate-oxidizing fermenting bacteria with H2-consuming methanogens (1, 8, 9, 30, 31, 28, 39, 45). Propionate oxidation, however, has not yet been investigated in continuous-culture experiments.

Therefore, we studied the energetics of propionate consumption in syntrophic cocultures of S. fumaroxidans and Methanospirillum hungatei in the absence and presence of sulfate by determining the Gibbs free energy available for both the propionate oxidizers and the H2-consuming methanogens under steady-state conditions in batch and chemostat cultures. The growth yields and maintenance coefficients of the syntrophic propionate oxidizer were also determined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and cultivation.

M. hungatei JF1T (DSM 864) and S. fumaroxidans MPOB (DSM 10017) were purchased from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (Braunschweig, Germany).

The microorganisms were grown in bicarbonate-buffered, sulfide-reduced mineral medium as described previously by Huser et al. (15). To 1 liter of medium, 1 ml of a vitamin solution (48) and 1 ml each of an acid and an alkaline trace elements solution were added (32). The vitamin solution was filter sterilized separately. The gas phase above the medium was N2-CO2 (80% to 20%) at 172 kPa, and the pH of the medium was 6.8 to 6.9. Substrates and other supplements were added from sterile anaerobic stock solutions. Pure cultures of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei were maintained on fumarate (40 mM) and hydrogen, respectively. Hydrogen was added to the headspace at an overpressure of 60 kPa. In the case of M. hungatei, 2 mM (each) formate, acetate, and isobutyrate were added as supplementary carbon sources. Culture purity was routinely checked by phase-contrast and fluorescence microscopy.

Batch and chemostat experiments.

In batch experiments, pure cultures of S. fumaroxidans or defined cocultures of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei were cultivated in 1-liter serum bottles containing 500 ml of mineral medium with 40 mM propionate with or without sulfate (40 mM) under a gas phase of N2-CO2 (80% to 20%) at 172 kPa.

Continuous cultivation was performed in a 1-liter chemostat system as described by Cypionka (7) with a working volume of 800 ml (flushed headspace) or 980 ml (nonflushed headspace). The chemostat experiments were only performed with cocultures of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei. The cocultures were grown under propionate limitation, and steady-state conditions were maintained for at least three culture volume changes. Substrate and product conditions were monitored, and total cell mass and species composition were checked under steady-state conditions.

For inoculation of the batch and chemostat experiments, S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei were pregrown on fumarate and hydrogen, respectively. Batch experiments with pure cultures of S. fumaroxidans were inoculated with 10% (vol/vol) S. fumaroxidans. Cocultures for batch and chemostat experiments were constructed by inoculating 10% (vol/vol) S. fumaroxidans and 10% (vol/vol) M. hungatei. All experiments were performed at 37°C.

Determination of specific cell mass.

Batch experiments were done as described above. Pure cultures of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei were grown with propionate plus SO42− and H2, respectively. Growth was measured by monitoring the total cell protein (see below). Cells were counted by phase-contrast microscopy using a Helber counting chamber. Bacterial dry mass was determined gravimetrically (see below). Cell suspensions contained (per liter) 27.4 ± 1.8 and 27.5 ± 0.6 mg (dry weight [dw]) of cells of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei, respectively. The corresponding cell numbers were (108 per ml) 2.25 ± 0.81 and 2.33 ± 0.01. The corresponding specific cell masses (xi; picograms [dw] per cell) 0.116 ± 0.037 and 0.119 ± 0.003.

Determination of growth parameters.

The maximum specific growth rate (μmax; per day) was calculated from the exponential part of the propionate depletion curves of batch cultures. The total growth yield of the pure and mixed cultures growing on propionate or on propionate plus sulfate in batch culture experiments was determined from the microbial cell dw (see below). The total growth yield in continuous culture was determined from the protein concentration at steady state by multiplication by a conversion factor (see below). The total biomass yield was calculated from the number of grams of dry biomass produced per mole of propionate degraded. For cocultures, the determined yield is the sum of the yields of both species participating in the degradation of propionate. Consequently, the measured yield is referred to as YXtot-S (grams of dw per mole of a substrate).

The dry mass of the propionate-degrading and methanogenic microorganisms (Xi; grams [dw] per liter) were calculated from the total cell mass (Xtot), the relative cell numbers (Ni; cells per milliliter) in the culture, and the specific cell masses (xi; grams [dw] per cell) according to the following equations (26):

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

The growth yields of the propionate-degrading microorganisms (YMPOB-S) and hydrogenotrophic methanogens (YMhun-P) in the batch incubations were calculated by relating the increase in the biomass concentration to the amount of propionate (S) degraded or methane (P) formed.

In the chemostat experiments, the maximum growth yield (YMPOBmax) and the maintenance coefficient (ms; millimoles of propionate per hour per gram [dw]) were obtained from the regression parameters of the following relationship (24):

|

4 |

with Y the apparent growth yield at different dilution rates (μ = D) in a chemostat.

Gibbs free-energy changes.

Standard Gibbs free-energy changes (ΔG0) for the individual steps in the degradation of propionate (see Table 1) were calculated from the standard Gibbs free energies of formation (ΔGf0) of the reactants and products (36), corrected for a temperature of 37°C by the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation. The Gibbs free energies (ΔG) in the cultures were calculated from the ΔG0 of the individual reactions using the actually measured concentrations or partial pressures of the reactants and products, as well as the prevailing temperature and pH (6.9).

Maintenance energy.

The maintenance energy (mE) was determined from measured values as described by Heijnen and VanDijken (13) and Tijhuis et al. (38). The measured maintenance coefficients (ms), in millimoles of substrate (electron donor) per gram (dw) of biomass per hour, were converted to mD, in moles of substrate C per mole of biomass C per hour. The available standard Gibbs free energy (ΔGav01; kilojoules per mole of substrate) was calculated from ΔG0′ (kilojoules per mole of substrate) of the reaction divided by the number of C atoms (three for propionate) and the degree of reduction (γD = 4.67 for propionate) of the substrate. The maintenance energy, in kilojoules per mole of biomass C per hour, was then calculated by the following equation:

|

5 |

Tijhuis et al. (38) found that mE can also be determined theoretically by the following equation:

|

6 |

Gibbs free-energy dissipation per mole of biomass C.

The Gibbs free-energy dissipation per mole of biomass C (Ds01/rAx; kilojoules per mole of biomass C) was calculated as described by Heijnen and VanDijken (13) by solving the macrochemical equation, which, for the syntrophic oxidation of propionate by a coculture of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei, can be written as follows:

|

7 |

|

The macrochemical equation for the oxidation of propionate by S. fumaroxidans can be written as follows:

|

8 |

|

The coefficient f was calculated from the determined maximum growth yield (Ymax). The other five stoichiometric coefficients (a, b, c, d, e) were calculated from the five (C, H, O, N, and electric charge) conservation equations. Ds01/rAx was then calculated by using the tabulated ΔGf0 for the reactants and products and ΔGf0 = −67 kJ mol of biomass C−1 (CH1.8O0.5N0.2) (13).

Heijnen and VanDijken (13) showed that Ds01/rAx can also be theoretically predicted from the number of C atoms (C) and the degree of reduction (yD) of the substrate C source as follows:

|

9 |

For propionate, the theoretical Ds01/rAx is 426.6 kJ mol of biomass C−1. This value can then be used to calculate a theoretical growth yield for the coculture of S. fumaroxidans plus M. hungatei and for S. fumaroxidans alone using the macrochemical equations and solving for the six stoichiometric coefficients by using the six (C, H, O, N, electric charge, and energy) conservation equations (13).

Analytical procedures.

During microbial growth, samples were taken for analysis of substrate and product concentrations. H2 and CH4 were quantified by gas chromatography (6, 29). Propionate and acetate were measured by high-pressure liquid chromatography (18). Sulfate was analyzed by ion chromatography (2). Bacterial growth was monitored by protein determination. Cell pellets of 4-ml culture samples were resuspended in 1 ml of 1 M NaOH. After heating at 100°C for 15 min, the samples were treated further by the method of Bradford (4). Bovine serum albumin was used as the standard. The dw of a known culture volume was determined gravimetrically. The samples were gassed with N2-CO2 to remove H2S, centrifuged, and washed twice with 50 mM ammonium acetate buffer (pH 6.0). The washed suspension was transferred into glass bottles and dried at 100°C to a constant weight. Cell numbers were counted by phase-contrast microscopy (see above). Conversion factors between protein content and biomass dw were determined by dividing the biomass dw by the protein content.

RESULTS

Batch experiments.

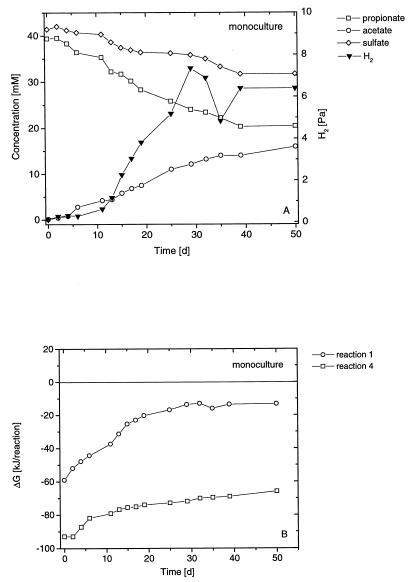

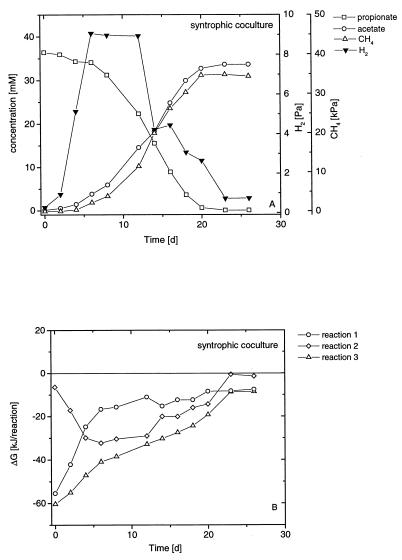

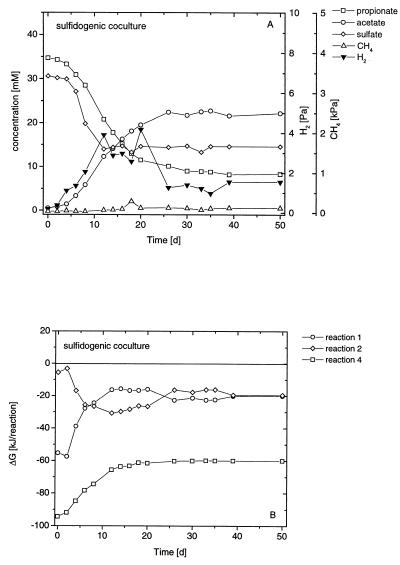

The degradation of propionate by a pure culture of S. fumaroxidans in the presence of sulfate is shown in Fig. 1A. Propionate was stoichiometrically converted (Table 1) to acetate while sulfate was reduced. However, only part of the propionate was degraded. H2 accumulated to about 7 Pa and remained at this level. A syntrophic culture of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei (syntrophic coculture) degraded propionate completely to acetate and CH4 (Fig. 2A). During the incubation, H2 transiently accumulated to about 9 Pa but decreased at the end to 0.8 Pa. A coculture grown on propionate plus sulfate (sulfidogenic coculture) degraded propionate almost completely to acetate (Fig. 3A). During the incubation, H2 accumulated to about 4 Pa but again decreased at the end to 1.5 Pa.

FIG. 1.

Batch monoculture of S. fumaroxidans growing on propionate plus sulfate. (A) Changes in propionate (□), acetate (○), hydrogen (▾), and sulfate (◊). (B) Actual Gibbs free-energy changes of fermentative propionate oxidation (○) and sulfidogenic propionate oxidation (□).

FIG. 2.

Batch syntrophic coculture of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei growing on propionate. (A) Changes in propionate (□), acetate (○), hydrogen (▾), and methane (▵). (B) Actual Gibbs free-energy changes of fermentative propionate oxidation (○), hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (◊), and syntrophic propionate oxidation (▵).

FIG. 3.

Batch sulfidogenic coculture of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei growing on propionate plus sulfate. (A) Changes in propionate (□), acetate (○), hydrogen (▾), sulfate (◊), and methane (▵). (B) Actual Gibbs free-energy changes of fermentative propionate oxidation (○), hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (◊), and sulfidogenic propionate oxidation (□).

The actual Gibbs free energies of the degradation of propionate by a pure culture of S. fumaroxidans in the presence of sulfate are depicted in Fig. 1B for both fermentative and sulfidogenic propionate degradation. The Gibbs free-energy values of propionate degradation under fermentative, syntrophic, and sulfidogenic conditions, as well as H2-dependent methanogenesis, are shown in Fig. 2B and 3B for the syntrophic and sulfidogenic cocultures, respectively. S. fumaroxidans grown in a coculture with M. hungatei on propionate plus sulfate is referred to as a sulfidogenic coculture.

The μmax, YXtot-S, and carbon and electron recoveries were calculated for three batch cultures and are summarized in Table 2. The culture conditions, i.e., pure culture, syntrophic coculture, and sulfidogenic coculture, significantly affected the μmax and YXtot-S of the cocultures. The highest μmax value was found in the syntrophic cocultures, followed by the sulfidogenic coculture.

TABLE 2.

μmax, YXtot-S, C and e recoveries, and protein conversion factora for batch cultures of S. fumaroxidans grown in a monoculture or in a coculture with M. hungatei on either propionate alone or propionate plus sulfateb

| Culture | Substrate | YXtot-S (g [dw] mol−1) | μmax (day−1) | C recoveryc (%) | e recoveryc (%) | Conversion factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoculture | Propionate + SO42− | 1.24 (0.21) | 0.020 (0.002) | 103 (2) | 95 (2) | 3.0 (0.5) |

| Coculture | Propionate | 1.57 (0.07) | 0.208 (0.012) | 113 (1) | 99 (1) | 2.5 (0.2) |

| Coculture | Propionate + SO42− | 1.28 (0.04) | 0.089 (0.005) | 107 (2) | 97 (2) | 2.3 (0.2) |

Conversion factor for protein to dw.

Values in parentheses represent 1 standard deviation of the measured values (n = 3).

For the calculation of C and e recovery, the total dw was calculated by multiplying the measured protein concentration by the determined conversion factor. C4H7.2O2N0.8 was used as the structural formula for biomass.

The calculated YMPOB-S of S. fumaroxidans and YMhun-P of M. hungatei are presented in Table 3. The error associated with the calculation of the Xi of the propionate-degrading and methanogenic microorganisms calculated from the Xtot, the Ni, and the xi was, in all cases, <20%. Furthermore, the qmax values for propionate were calculated from μmax and YMPOB-S. S. fumaroxidans obtained the highest YMPOB-S in the pure-culture incubation, followed by the syntrophic coculture and the sulfidogenic coculture (Table 3). M. hungatei, on the other hand, reached the highest YMhun-P in the sulfidogenic coculture rather than in the syntrophic coculture (Table 3). The highest qmax values were observed in the syntrophic coculture, followed by the sulfidogenic coculture and the pure culture (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

YMhun-P, YMPOB-S, qmax, actual ΔG, and YMPOBΔG for propionate-oxidizing S. fumaroxidans grown under three different batch conditions

| Culture | Substrate | YMPOB-S (g [dw] mol of S−1) | YMhun-P (g [dw] mol of P−1) | qmaxa (mol of S [g [dw] d−1]−1) | ΔGb (kJ mol of S−1) | YMPOBΔGc (g [dw] 70 kJ−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoculture | Propionate + SO42− | 1.24 (0.21) | 0.016 | −74.3 (2.4) | 1.2 | |

| Coculture | Propionate | 1.02 (0.04) | 0.73 (0.07) | 0.204 | −12.6 (2.7) | 5.7 |

| Coculture | Propionate + SO42− | 0.82 (0.04) | 17.7 (2.0) | 0.109 | −62.3 (1.7) | 0.9 |

qmax = μmax/YMPOB-S.

Values are the actual Gibbs free-energy changes for the conversion of propionate by S. fumaroxidans (reaction 4 in Table 1), syntrophic coculture (reaction 1 in Table 1), and sulfidogenic coculture (reaction 4). The average actual Gibbs free energies between 11 and 29, 8 and 20, and 12 and 26 days, respectively (Fig. 1B, 2B, and 3B), are shown.

Measured growth yields (see Table 2), normalized to an energy quantum of 70 kJ mol of S−1, are shown.

Chemostat experiments.

Syntrophic cocultures of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei were grown in chemostats with or without a flushed headspace. The conversion of substrates to products was generally well balanced (C balance, 116 to 130% and e balance, 96 to 105%). The steady-state partial pressures of H2 were 0.2 to 0.3 and 4.5 to 10 Pa in the flushed and nonflushed systems, respectively.

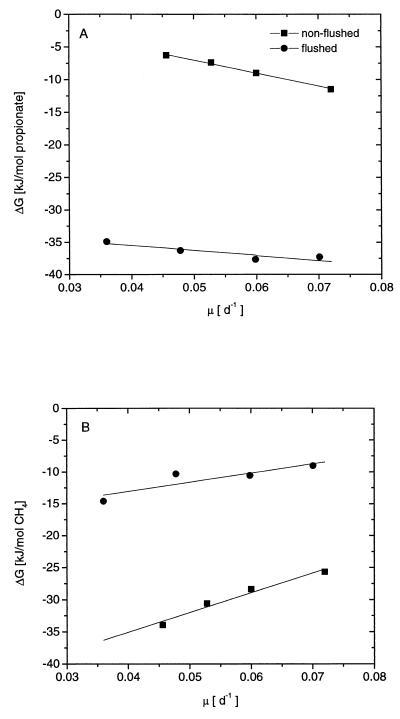

The actual Gibbs free energy of propionate fermentation (reaction 1 in Table 1) under steady-state conditions decreased linearly (becoming more negative) with increasing growth rate (Fig. 4A). Due to the lower H2 partial pressure, the Gibbs free energy was more negative in the flushed system than in the nonflushed system. The ranges of Gibbs free energies available under steady-state conditions in the flushed and nonflushed systems were −35.0 to −37.8 and −6.3 to −11.5 kJ per mol of propionate, respectively. On the other hand, the actual Gibbs free energy of hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis (reaction 2 in Table 1) under steady-state conditions increased linearly with the growth rate (Fig. 4B). Due to the lower H2 partial pressure, the Gibbs free energy was more positive in the flushed system than in the nonflushed system. The ranges of Gibbs free energies available under steady-state conditions in the flushed and nonflushed systems were −9.0 to −14.1 and −25.7 to −34.0 kJ per mol of CH4, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Actual Gibbs free-energy changes available for S. fumaroxidans (A) and M. hungatei (B) determined during syntrophic growth in propionate-limited chemostat cocultures with a flushed (●) or nonflushed (■) gas headspace.

Xtot, qs, and qCH4 increased linearly with growth rates (data not shown). Xtot values were higher in the flushed system than in the nonflushed system. The opposite was true for the specific propionate conversion rates, which were the highest in the nonflushed system.

Growth yields of the total coculture and of each syntrophic partner were determined individually by the total dw, the relative cell number, and the specific cell masses. Total dw was determined by multiplying the measured protein concentration by the determined conversion factor (Table 2).

The average growth yields (n = 4) for the total coculture obtained in the flushed and nonflushed systems were 4.0 ± 0.5 and 2.2 ± 0.2 g (dw) mol of S−1, respectively. These values were used to calculate Ytotmax and ms-tot from the regression parameters of the Pirt equation (equation 4) and are listed in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Ymax and ms of S. fumaroxidans cocultured with M. hungatei in two different chemostat set-ups

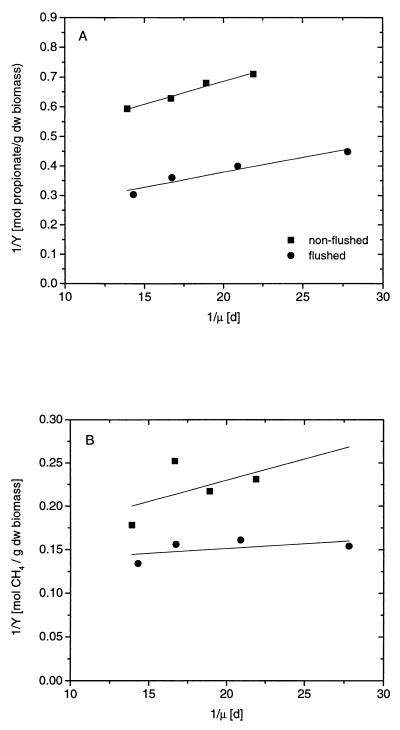

The average growth yields (n = 4) for S. fumaroxidans obtained in the flushed and nonflushed systems were 2.7 ± 0.5 and 1.5 ± 0.1 g (dw) mol of S−1, respectively. These values were used to calculate YMPOBmax and ms from the regression parameters of the Pirt equation (Fig. 5A) and are listed in Table 4.

FIG. 5.

Reciprocal plots of growth yields (1/Y) versus growth rates (1/μ) of S. fumaroxidans (A) (1/YMPOB) and M. hungatei (B) (1/YMhun) in propionate-limited chemostat cocultures with a flushed (●) or nonflushed (■) gas headspace.

The average growth yields (n = 4) for M. hungatei were calculated by relating the increase in the biomass concentration to the amount of methane formed. The amount of methane formed was calculated by assuming that 0.75 mol of methane was formed per mol of propionate (Table 1, reaction 3). The growth yields of M. hungatei obtained in the flushed and nonflushed systems were 6.6 ± 0.6 and 4.6 ± 0.7 g (dw) mol of P−1, respectively. These values were used to calculate YMhunmax and ms from the regression parameters of the Pirt equation (Fig. 5B) and are listed in Table 4.

Ds01/rAx, calculated from the determined Ytotmax of the chemostat cocultures of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei, in the flushed and nonflushed systems, were 56.1 and 167.6 kJ mol of C−1, respectively. The Ds01/rAx calculated from the determined YMPOBmax of S. fumaroxidans in the flushed and nonflushed systems were −320.7 and −705.7 kJ mol of C−1, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Energetics of syntrophic propionate oxidation.

The Gibbs free energy available for propionate-oxidizing S. fumaroxidans was found to be higher in the flushed (−35 to −38 kJ mol of propionate−1) than in the nonflushed (−6 to −12 kJ mol of propionate−1) chemostat cocultures. A possible disequilibrium of H2 between the liquid and gas phases would have resulted in even higher Gibbs free energies (less exergonic) than indicated by the values above. Disregarding this potential bias, the apparent Gibbs free-energy change in the flushed system is sufficient to generate not more than 1/2 mol of ATP, while in the nonflushed system less than 1/11 to 1/7 mol of ATP can be generated. The possible ATP generation based on the Gibbs free-energy change in the syntrophic batch cultures (−12.6 kJ mol of propionate−1; Table 3) was similarly low as in the nonflushed chemostat. The Gibbs free-energy change in the flushed chemostat system is more than the minimum energy quantum necessary to sustain microbial life (−23 kJ mole of substrate−1 ≅ 1/3 mol of ATP), but this is not the case in the nonflushed chemostat and in the batch culture. Nevertheless, our experiments show that microbial growth was sustained even in the nonflushed system. Hence, the available Gibbs free energy was apparently sufficient. Relatively small free-energy changes during the degradation of propionate have also been reported for different methanogenic environments (5, 19, 26, 46). These observations raise the question of how S. fumaroxidans and other syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria manage to exploit the little Gibbs free energy available for the generation of ATP. More research is required to answer this question.

Growth parameters.

Measured values of growth parameters obtained in batch experiments depended on the type of culture and the overall propionate-consuming reaction. S. fumaroxidans had the highest YMPOB-S but the lowest μmax when grown as a pure culture (propionate plus sulfate). The values of YMPOB-S and μmax (Table 2) we obtained correspond well to the previously reported values of 1.5 g (dw) mol of S−1 and 0.024 day−1 (40), respectively. The μmax values reported for S. fumaroxidans cocultured with M. hungatei on propionate was reported to be 0.17 day−1 (32). We obtained a value of 0.21 ± 0.01 day−1 for μmax, which is in the same range as the reported value. Growth yields of S. fumaroxidans in syntrophic or sulfidogenic cocultures are not reported in the literature. The growth yields we calculated for S. fumaroxidans were 1.02 ± 0.04 and 0.82 ± 0.04 g (dw) mol of S−1, respectively. Our results showed that the calculated and reported yields of S. fumaroxidans grown as a pure culture were higher than the values obtained in syntrophic and sulfidogenic cocultures. The reason for the lower growth yields in the cocultures can be explained by the fact that the available energy has to be shared between the two syntrophic partners.

The YMPOBmax and the ms for S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei cocultured on propionate were determined in chemostat cultures (Table 4). To our knowledge, these are the first data obtained for a syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacterium. The values are comparable to those determined for Pelobacter acetylenicus growing on ethanol syntrophically with different H2-consuming anaerobes (31).

Maintenance energy.

Tijhuis et al. (38) showed that the maintenance requirements of microorganisms can be described on the basis of mE, which theoretically should only be a factor of temperature. Thus, the theoretical mE values at 28, 30, and 37°C are 4.4 ± 1.4, 5.2 ± 1.7 and 9.8 ± 3.1 kJ mol of biomass C−1 h−1, respectively (38). We calculated the parameter mE from literature data on an ethanol-oxidizing syntrophic coculture on several anaerobic pure cultures and included the data obtained from the chemostat cocultures of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei (Table 5). Interestingly, these mE values were usually lower than the theoretical values, some by more than 1 order of magnitude.

TABLE 5.

mE determined for different anaerobic monocultures and cocultures grown under different conditions using the measured ms and the ΔGav01 of the overall catabolic reaction

| Microorganism | Temp (°C) | Substrate | ΔGav01 (kJ e-mol−1) | γD | mD (mol of [C] mol of C−1 h−1) | mE (kJ mol of C−1 h−1) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. fumaroxidans cocultured with M. hungatei | |||||||

| Flushed chemostat | 37 | Propionate | 1.86a | 4.67 | 0.023 | 0.20 | This study |

| Nonflushed chemostat | 37 | Propionate | 1.86a | 4.67 | 0.016 | 0.14 | This study |

| P. acetylenicus cocultured with H2 oxidizer: | |||||||

| Acetobacterium woodii | 28 | Ethanol | 3.54b | 6 | 0.100 | 2.12 | 30, 31 |

| Methanobacterium bryantii | 28 | Ethanol | 4.87c | 6 | 0.063 | 1.84 | 30, 31 |

| Desulfovibrio desulfuricans | 28 | Ethanol | 5.56d | 6 | 0.038 | 1.27 | 30, 31 |

| Pure-culture studies | |||||||

| Desulfovibrio propionicus | 28 | Ethanol | 5.56d | 6 | 0.047 | 1.56 | 35 |

| Desulfovibrio vulgaris Marburg | 28 | Ethanol | 5.56d | 6 | 0.224 | 7.47 | 35 |

| Pelobacter propionicus | 28 | Ethanol | 3.48e | 6 | 0.078 | 1.63 | 35 |

| Acetobacterium carbinolicum | 28 | Ethanol | 3.54b | 6 | 0.172 | 3.65 | 35 |

| Acetobacterium woodii | 30 | Lactate | 4.67f | 4 | 0.006 | 0.12 | 23 |

| Acetobacterium woodii | 30 | H2 | 12.7g | 2 | 0.042 | 1.06 | 23 |

Reaction 3 in Table 1.

Reaction: 2CH3CH2OH + 2HCO3− → 3CH3COO− + H+ + 2H2O.

Reaction: 2CH3CH2OH + HCO3− → 2CH3COO− + H+ + CH4 + H2O.

Reaction: 2CH3CH2OH + SO42− → 2CH3COO− + H+ + HS− + 2H2O.

Reaction: 8CH3CH2OH + 6HCO3− → 5CH3COO− + 4CH3CH2COO− + 3H+ + 8H2O.

Reaction: CH3CH2OCOO− → 1.5CH3COO− + 0.5H+.

Reaction: 4H2 + 2HCO3− + H+ → CH3COO− + 4H2O.

Heijnen and VanDijken (13) pointed out that to obtain meaningful values, the ΔGav should be calculated from the actual concentrations of reactants and products and that the use of ΔGav01, as done for calculation of the data in Table 5, is only a compromise if actual concentrations are not available. Therefore, we also calculated mE values from the actual ΔGav values measured for propionate oxidation by S. fumaroxidans (Fig. 4A) and H2-CO2-dependent methanogenesis by M. hungatei (Fig. 4B) in the chemostat experiments, using the species-specific ms values (Table 6). Again, however, the mE values of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei were more than 1 order of magnitude lower than the theoretical values expected from the equation of Tijhuis et al. (38). Obviously, the maintenance energies calculated from our chemostat experiments and from earlier experiments with anaerobic cultures are not consistent with the pertinent theory, suggesting that microorganisms, at least anaerobes, are able to grow at maintenance energies lower than those theoretically predicted. Tijhuis et al. (38) have concluded that (i) the electron acceptor, (ii) different C sources, (iii) the type of organism, and (iv) the use of mixed sludges versus pure cultures have no effect on mE. However, this conclusion was based on limited culture data. In particular, syntrophic cultures have not been included. In addition, Heijnen and VanDijken (13) cautioned that the derived theoretical relationships give only a first approximation based on thermodynamics and that modifications may be necessary if mechanistic details become available, e.g., microbes exploiting the available Gibbs free energy by using different metabolic pathways with different energetic efficiencies. There are even differences among the various physiological groups of anaerobic microbes in whether they depend on changes in reaction enthalpy or reaction entropy (42). For example, H2-CO2-dependent methanogenesis depends mainly on the enthalpy change and is retarded by the entropy change whereas anaerobes, syntrophs in particular, depend mainly on the entropy change (42). Apparently, more research is necessary to elucidate the theoretical background of maintenance energy in fastidious anaerobic bacteria.

TABLE 6.

mE determined from the ms and the actual ΔGav measured for S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei grown in syntrophic cocultures with two different chemostat setups

| Microorganism and chemostat conditiona | Substrate | ΔGav (kJ mol of e−1) | γD | mD (mol of [C] mol of C−1 h−1) | mE (kJ mol of C−1 h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. fumaroxidans | |||||

| Flushed | Propionate | 2.59b | 4.67 | 0.033 | 0.40 |

| Nonflushed | Propionate | 0.61b | 4.67 | 0.049 | 0.14 |

| M. hungatei | |||||

| Flushed | H2 | 1.44c | 2 | 0.005 | 0.01 |

| Nonflushed | H2 | 3.74c | 2 | 0.022 | 2.16 |

Gibbs free-energy dissipation per mol of biomass C.

Heijnen and VanDijken (13) showed that Ds01/rAx can be regarded as a simple thermodynamic measure of the amount of biochemical “work” required to convert a carbon source into biomass and can be used to characterize chemotrophic microbial growth. We calculated Ds01/rAx from the maximum growth yields determined for the syntrophic chemostat cocultures of S. fumaroxidans and M. hungatei. The calculated Ds01/rAx values for the flushed and nonflushed systems were 56.1 and 167.6 kJ mol of biomass C−1, respectively. These values are at the lower end of the range of values (150 to 3,500 kJ mol of biomass C−1) observed for various modes of chemotrophic growth (13). Furthermore, we calculated Ds01/rAx for S. fumaroxidans alone and obtained values of −320.7 and −705.7 kJ mol of biomass C−1, respectively, for the flushed and nonflushed systems. These negative values are not realistic and can be explained by the fact that the Ds01 is endergonic when using the standard Gibbs energies of formation for the reactants and products under standard conditions.

Therefore, we also calculated theoretical growth yields from a theoretical Ds01/rAx, which is 426 kJ mol of biomass C−1 for propionate. For the syntrophic coculture (equation 7), we calculated a Ytotmax of 4.4 g mol of S−1, i.e., similar to the actually observed values (Table 4). However, for S. fumaroxidans alone (equation 8), we obtained a negative YMPOBmax value, indicating that the theoretical Ds01/rAx must be too low. Only when we assumed a Ds01/rAx of >622 kJ mol of biomass C−1 did the calculated YMPOBmax become positive. When assuming a Ds01/rAx of 3,500 kJ mol of biomass C−1, we calculated a YMPOBmax of 1.95 g mol of S−1, i.e., similar to the actually observed values (Table 4). A Ds01/rAx as high as 3,500 kJ mol of biomass C−1 is usually observed in chemolithoautotrophic bacteria that use CO2 as a carbon source and require the occurrence of reversed electron transport, e.g., nitrifiers and thiobacilli. Our data indicate that syntrophic propionate oxidation by S. fumaroxidans falls into the same category of Gibbs free-energy dissipation.

Energetic efficiency of growth.

We were able to determine both the growth yield of S. fumaroxidans and the Gibbs free energy available by oxidation of propionate (Table 3). Although the net generation of ATP during the degradation of propionate is not clear, we were able to use the determined yields and Gibbs free-energy values to estimate a proxy (i.e., YMPOBΔG) for YATP, i.e., the biomass synthesized from 1 mol of ATP generated. Under physiological conditions, an average Gibbs free energy of 70 kJ is needed for the irreversible synthesis of 1 mol of ATP. Therefore, YMPOBΔG was calculated by normalizing the measured YMPOB-S to an energy quantum of 70 kJ mol−1 (16, 31). The results are shown in Table 3.

The YMPOBΔG values calculated for S. fumaroxidans grown on propionate plus sulfate in either a monoculture and a sulfidogenic coculture were 1.2 and 0.9 g (dw) 70 kJ−1, respectively. These values are much lower than the values of 5 to 12 g mol of ATP−1 reported by Stouthamer (34) for fermenting bacteria. The YMPOBΔG value for S. fumaroxidans grown on propionate in a syntrophic coculture was 5.7 g (dw) 70 kJ−1. The YMPOBΔG values calculated for flushed and nonflushed chemostat cocultures grown on propionate were 4.5 to 6.2 and 10.3 to 15.7 g (dw) 70 kJ−1, respectively. These values suggest that the energy efficiency in syntrophic cocultures was much higher than in sulfidogenic monocultures and cocultures.

A possible reason for the energetic inefficiency of sulfidogenic oxidation of propionate may be found in the mechanism of the reduction of sulfate to sulfide. With sulfate as an electron acceptor, substrate level phosphorylation might be more effective for the syntrophic propionate oxidizer but sulfate has to be activated first. This activation costs the cell 2 mol of ATP per mol of sulfate. Additionally, the cell losses another 1/3 mol of ATP during the transport of sulfate across the microbial membrane. So, the activation and transport of sulfate costs the cell 2 1/3 mol of ATP per mol of sulfate (47). This amount of energy cannot be generated at substrate level phosphorylation alone (maximum of 1 1/3 mol of ATP per mol of sulfate consumed). Thus, it is most likely that S. fumaroxidans associates the reduction of sulfate with an electron transport chain allowing chemiosmotic ATP synthesis. If this process operates inefficiently, it may explain the observed low energy efficiency for growth. Furthermore, this hypothesis could explain why syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria are outcompeted by propionate-oxidizing sulfate reducers. However, to our knowledge, no data concerning the energy efficiency for growth on propionate and sulfate for propionate-oxidizing sulfate reducers is available. Thus, there is no direct evidence to support these hypotheses.

Conclusion.

It is postulated that the small Gibbs free-energy changes observed during the degradation of propionate in different methanogenic environments are sufficient to sustain microbial growth. However, the Gibbs free-energy changes observed are much lower than those theoretically predicted. Furthermore, it is assumed that the calculated low energetic efficiency of S. fumaroxidans during growth on propionate plus sulfate can be due to an inefficient electron transport chain involved in chemiosmotic energy conservation. The observed growth yields further suggest that S. fumaroxidans requires a relatively large Gibbs free-energy dissipation for biomass synthesis, similar to that typically observed for chemolithoautotrophic bacteria with reversed electron transport.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was financially supported by the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahring B K, Westermann P. Product inhibition of butyrate metabolism by acetate and hydrogen in a thermophilic coculture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2393–2397. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.10.2393-2397.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bak F, Scheff G, Jansen K H. A rapid and sensitive ion chromatographic technique for the determination of sulfate and sulfate reduction rates in freshwater lake sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1991;85:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boone D R, Bryant M P. Propionate-degrading bacterium, Syntrophobacter wolinii sp. nov. gen. nov., from methanogenic ecosystems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;40:626–632. doi: 10.1128/aem.40.3.626-632.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin K J, Conrad R. Intermediary metabolism in methanogenic paddy soil and the influence of temperature. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;18:85–102. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conrad R, Schütz H, Babbel M. Temperature limitation of hydrogen turnover and methanogenesis in anoxic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1987;45:281–289. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cypionka H. Sulfide-controlled continuous culture of sulfate-reducing bacteria. J Microbiol Methods. 1986;5:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dong X, Plugge C M, Stams A J M. Anaerobic degradation of propionate by a mesophilic acetogenic bacterium in coculture and triculture with different methanogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2834–2838. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2834-2838.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dwyer D F, Weeg-Aerssens E, Shelton D R, Tiedje J M. Bioenergetic conditions of butyrate metabolism by a syntrophic, anaerobic bacterium in coculture with hydrogen-oxidizing methanogenic and sulfidogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1354–1359. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.6.1354-1359.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanselmann K W. Microbial energetics applied to waste repositories. Experientia. 1991;47:645–687. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmsen H J M, VanKuijk B L M, Plugge C M, Akkermans A D L, DeVos W M, Stams A J M. Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans sp. nov., a syntrophic propionate-degrading sulfate-reducing bacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:1383–1387. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-4-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmsen H J M, Kengen K M P, Akkermans A D L, Stams A J M. Phylogenetic analysis of two syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria in enrichments cultures. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heijnen J J, VanDijken J P. In search of a thermodynamic description of biomass yields for the chemotrophic growth of microorganisms. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1992;39:833–858. doi: 10.1002/bit.260390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houwen F P, Plokker J, Stams A J M, Zehnder A J B. Enzymatic evidence for involvement of the methylmalonyl-CoA pathway in propionate oxidation by Syntrophobacter wolinii. Arch Microbiol. 1990;155:52–55. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huser B A, Wuhrmann K, Zehnder A J B. Methanothrix soehngenii gen. nov. sp. nov., a new acetotrophic non-hydrogen-oxidizing methane bacterium. Arch Microbiol. 1982;132:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00407022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kleerebezem R, Pol L W H, Lettinga G. Anaerobic degradation of phthalate isomers by methanogenic consortia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1152–1160. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1152-1160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koch M, Dolfing J, Wuhrmann K, Zehnder A J B. Pathways of propionate degradation by enriched methanogenic cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:1411–1414. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.4.1411-1414.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krumböck M, Conrad R. Metabolism of position-labelled glucose in anoxic methanogenic paddy soil and lake sediment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1991;85:247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krylova N I, Janssen P H, Conrad R. Turnover of propionate in methanogenic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;23:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Balkwill D L, Aldrich H C, Drake G R, Boone D R. Characterization of the anaerobic propionate-degrading syntrophs Smithella propionica gen. nov., sp. nov. and Syntrophobacter wolinii. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49:545–556. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mah R A, Xun L-Y, Boone D R, Ahring B, Smith P H, Wilkie A D. Methanogenesis from propionate in sludge and enrichment systems. In: Belaich J-P, Bruschi M, Garcia J L, editors. Microbiology and biochemistry of strict anaerobes involved in interspecies transfer. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mucha H, Lingens F, Trösch W. Conversion of propionate to acetate and methane by syntrophic consortia. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1988;27:581–586. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peters V, Janssen P H, Conrad R. Efficiency of hydrogen utilization during unitrophic and mixotrophic growth of Acetobacterium woodii on hydrogen and lactate in the chemostat. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;26:317–324. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirt S J. Maintenance energy: a general model for energy-limited and energy-sufficient growth. Arch Microbiol. 1982;133:300–302. doi: 10.1007/BF00521294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plugge C M, Dijkema C, Stams A J M. Acetyl-CoA cleavage pathway in a syntrophic propionate oxidizing bacterium growing on fumarate in the absence of methanogens. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;110:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothfuss F, Conrad R. Thermodynamics of methanogenic intermediary metabolism in littoral sediment of Lake Constance. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1993;12:265–276. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schink B. Syntrophism among prokaryotes. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K H, editors. The prokaryotes. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1992. pp. 276–299. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schink B. Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:262. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.262-280.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuler S, Conrad R. Soils contain two different activities for oxidation of hydrogen. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1990;73:77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seitz H J, Schink B, Pfennig N, Conrad R. Energetics of syntrophic ethanol oxidation in defined chemostat cocultures. 1. Energy requirement for H2 production and H2 oxidation. Arch Microbiol. 1990;155:82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seitz H J, Schink B, Pfennig N, Conrad R. Energetics of syntrophic ethanol oxidation in defined chemostat cocultures. 2. Energy sharing in biomass production. Arch Microbiol. 1990;155:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stams A J M, VanDijk J B, Dijkema C, Plugge C M. Growth of syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacteria with fumarate in the absence of methanogenic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1114–1119. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1114-1119.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stams A J M. Metabolic interactions between anaerobic bacteria in methanogenic environments. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1994;66:271–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00871644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stouthamer A H. The search for correlation between theoretical and experimental growth yields. Int Rev Biochem. 1979;21:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szewzyk R, Pfennig N. Competition for ethanol between sulfate-reducing and fermenting bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1990;153:470–477. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thauer R K, Jungermann K, Decker K. Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1977;41:100–180. doi: 10.1128/br.41.1.100-180.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thauer R K, Morris J G. Metabolism of chemotrophic anaerobes: old views and new aspects. In: Kelly D P, Carr N G, editors. The microbe 1984: part II prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1984. pp. 123–168. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tijhuis L, VanLoosdrecht M C M, Heijnen J J. A thermodynamically based correlation for maintenance Gibbs energy requirements in aerobic and anaerobic chemotrophic growth. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1993;42:509–519. doi: 10.1002/bit.260420415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Traore A S, Gaudin C, Hatchikian C E, Le Gall J, Belaich J-P. Energetics of growth of a defined mixed culture of Desulfovibrio vulgaris and Methanosarcina barkeri: maintenance energy coefficient of the sulfate-reducing organism in the absence and presence of its partner. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:1260–1264. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1260-1264.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.VanKuijk B L M, Stams A J M. Sulfate reduction by a syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacterium. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1995;68:293–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00874139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.VanKuijk B L M, Schlösser E, Stams A J M. Investigation of the fumarate metabolism of the syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacterium strain MPOB. Arch Microbiol. 1998;169:346–352. doi: 10.1007/s002030050581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.VonStockar U, Liu J S. Does microbial life always feed on negative entropy? Thermodynamic analysis of microbial growth. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1412:191–211. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallrabenstein C, Hauschild E, Schink B. Pure culture and cytological properties of ‘Syntrophobacter wolinii’. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;123:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallrabenstein C, Hauschild E, Schink B. Syntrophobacter pfennigii sp nov, new syntrophically propionate-oxidizing anaerobe growing in pure culture with propionate and sulfate. Arch Microbiol. 1995;164:346–352. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warikoo V, McInerney M J, Robinson J A, Suflita J M. Interspecies acetate transfer influences the extent of anaerobic benzoate degradation by syntrophic consortia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:26–32. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.26-32.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Westermann P. The effect of incubation temperature on steady-state concentrations of hydrogen and volatile fatty acids during anaerobic degradation in slurries from wetland sediments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1994;13:295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Widdel F, Hansen T A. The dissimilatory sulfate- and sulfur-reducing bacteria. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K H, editors. The prokaryotes. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1992. pp. 583–624. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolin E A, Wolin M J, Wolfe R S. Formation of methane by bacterial extracts. J Biol Chem. 1963;238:2882–2886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zellner G, Busmann A, Rainey F A, Diekmann H. A syntrophic propionate-oxidizing, sulfate-reducing bacterium from a fluidized bed reactor. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:414–420. [Google Scholar]