Abstract

Objectives

Ixekizumab, a high-affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets interleukin 17A (IL-17A), has shown significant efficacy in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and sustained long-term clinical response without unexpected new safety outcome for an IL-17A inhibitor. Here, we report the updated safety profile of ixekizumab up to 3 years in patients with PsA.

Methods

This is an integrated safety analysis from four clinical trials in patients with PsA who received at least one dose of ixekizumab. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and selected adverse events (AEs) exposure-adjusted incidence rates (EAIRs) per 100 patient-years up to 3 years of exposure are reported.

Results

A total of 1401 patients with a cumulative ixekizumab exposure of 2247.7 patient-years were included in this analysis. The EAIR of patients with ≥1 TEAE was 50.3 per 100 patient-years and most TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity. Serious AEs were reported by 134 patients (EAIR=6.0). The most reported TEAEs were nasopharyngitis (EAIR=9.0) and upper respiratory tract infection (EAIR=8.3). Infections in general and injection site reactions were the most common TEAEs; the incidence rates of serious cases were low (EAIR ≤1.2). The EAIRs of malignancies (EAIR=0.7), inflammatory bowel disease (EAIR=0.1) including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, depression (EAIR=1.6), and major adverse cerebro-cardiovascular events (EAIR=0.5) were low. As assessed, based on year of exposure, incidence rates were decreasing or constant over time.

Conclusions

In this analysis, the overall safety profile and tolerability of ixekizumab are consistent with the known safety profile in patients with PsA. No new or unexpected safety events were detected.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Psoriatic Arthritis, Biological Therapy, Inflammation, Therapeutics

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Ixekizumab is a high-affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets interleukin 17A and has shown significant efficacy in the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis (PsA).

What does this study add?

This study includes a large safety analysis (N=1401; cumulative exposure=2247.7 patient-years) across four clinical trials with up to 3 years of ixekizumab treatment for PsA.

In this report, the exposure-adjusted incidence rate of serious adverse event was 6.0 per 100 patient-years.

In patients with active PsA, safety data reinforce the known safety profile of ixekizumab.

How might this impact on clinical practice or future developments?

This analysis provides clinically meaningful evidence of the overall safety profile of ixekizumab in patients with active PsA.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a heterogeneous inflammatory disease associated with cardiovascular, psychological and metabolic comorbidities.1–4 Current pharmacological management of PsA includes non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Recently, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis has recommended the use of interleukin 17 (IL-17) inhibitors, tumour necrosis factor inhibitors and Janus kinase inhibitors as treatment options for all patients with PsA. Use of IL-12/23 inhibitors, IL-23 inhibitors or phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors is considered when certain domains are involved.5

Ixekizumab is a high-affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively targets the IL-17A cytokine and is approved for treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in adults and children who are at least 6 years of age, active PsA, active ankylosing spondylitis and active non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis.6–9 The safety profile of ixekizumab 80 mg every 2 weeks or 4 weeks in patients with PsA has been previously published.10–13

In this analysis, we report the safety profile of ixekizumab for the PsA SPIRIT programme. In this report, we further evaluate the exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR), outcomes and medical history of patients with active PsA who experienced selected adverse events (AEs) of interest.

Methods

Patients and study design

Patient data were integrated from four randomised controlled clinical trials of ixekizumab in patients with active PsA, including SPIRIT-P1 (NCT01695239), SPIRIT-P2 (NCT02349295), SPIRIT-P3 (NCT02584855) and SPIRIT-H2H (NCT03151551). Eligibility criteria have been previously described.14–17 Briefly, patients were required to have active PsA that met the classification criteria for PsA with at least 3 of 68 tender and at least 3 of 66 swollen joints, and active psoriatic skin lesions or a documented history of psoriasis. Patients were excluded if they had active Crohn’s disease or active ulcerative colitis or if they had any condition that would pose an unacceptable risk to the patient or otherwise confound the results of the respective studies. Detailed study designs have been previously published.14–17 A summary is presented in online supplemental materials.

annrheumdis-2021-222027supp001.pdf (83.1KB, pdf)

Outcomes

All AEs were classified according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 22.1. A treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE) was an event that first occurred or worsened in severity after baseline and on or before the last day of the treatment period. Selected AEs of interest included infections, injection site reactions (ISRs), allergic reactions/hypersensitivity, malignancies including non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and malignancies excluding NMSC, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) including Crohn’s disease ulcerative colitis and IBD unclassified, depression, suicidal behaviour/self-injury, cytopaenia, and major adverse cerebro-cardiovascular event (MACE). MACE and IBD event analyses were executed by externally adjudicated analysis. According to Registre Epidemiologique des Maladies de l’Appareil Digestif criteria, IBD events classified as ‘probable’ and ‘definite’ per external adjudication were considered confirmed and reported. The IBD adjudication programme was developed and executed retrospectively for SPIRIT-P1, SPIRIT-P2 and SPIRIT-P3, and prospectively for SPIRIT-H2H. Depression was measured using the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology - Self-Report. Suicidal ideation was measured using the Columbia Suicide Rating Scale. Opportunistic infections (OIs) were reported according to the consensus recommendations for infections.18 Latent tuberculosis infection was identified by either latent tuberculosis preferred term or a positive result on any of the following annual tests: tuberculin skin test, interferon-gamma release assay or Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex test. Patients who tested positive for latent tuberculosis at screening could be rescreened and enrolled after receiving at least 4 weeks of appropriate therapy and having no evidence of hepatotoxicity (alanine transaminase (ALT)/alanine transaminase (AST) remained ≤2 times the upper limit of normal (ULN)). ISRs (broad term) included the following preferred terms: ISR, injection site (IS) erythema, IS pain, IS swelling, IS pruritus, IS hypersensitivity, IS bruising, IS rash, IS haematoma, IS induration, IS papule, IS urticaria, IS mass, IS warmth, IS discolouration, IS inflammation and IS oedema.

Statistical analysis

Safety analyses were based on all randomised patients who received at least one dose of the study drug (pooled data from patients at 80 mg every 4 weeks and every 2 weeks); a post-hoc safety analysis of the two ixekizumab regimens (every 2 weeks and every 4 weeks) was also conducted. Total exposure was calculated by summarising the duration of ixekizumab exposure (in days) for all patients divided by 365.25 and expressed in total patient-years (PY). All safety events were reported by number and percentage of patients with AEs and EAIRs per 100 PY (95% CI). All EAIRs were calculated as divided total number of patients who experienced the TEAE for each preferred term by the sum of all patients’ time (in 100 years) of exposure during the treatment period. The entire time on study during the treatment period was used. The current analysis includes data from initiation of the studies to 19 March 2020 cut-off.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or conduct of the study, development of outcomes or dissemination of study results.

Results

Demographic and baseline characteristics

A total of 1401 patients were included in this analysis (table 1). The mean age was 49.1 years and half of the cohort were female (51.5%). Most patients in this analysis were white (91.3%), and the mean body mass index was 30.0 kg/m2 (±6.9 SD). The mean duration of PsA symptoms was 9.4 years (±8.6). Previous exposure to systemic therapy with non-biologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs was observed in 74.2% and 24.1% of patients, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

| Characteristics |

Integrated IXE PsA

N=1401 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 49.1 (11.9) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 679 (48.5) |

| Female | 722 (51.5) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 1278 (91.3) |

| Other | 122 (8.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.0 (6.9) |

| Duration of symptoms, years, mean (SD) | 9.4 (8.6) |

| Previous PsA systemic therapy, n (%) | |

| Never used | 290 (20.7) |

| Non-biologic | 1040 (74.2) |

| Biologic | 338 (24.1) |

| Medical history, n (%) | |

| Herpes zoster | 19 (1.4) |

| Candida infections | 4 (0.3) |

| Latent tuberculosis | 35 (2.5) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 14 (1.0) |

BMI, body mass index; IXE, ixekizumab; N, number of patients in the analysis population; n, number of patients in each category; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

Exposure and general safety

The cumulative ixekizumab exposure from four studies was 2247.7 PY and included data up to 3 years; the mean exposure was 586.4 days (19.3 months), ranging from 8 to 1219 days (table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of safety

|

Integrated IXE PsA

N=1401 |

|||

| Total patient-years of exposure | 2247.7 | ||

| Mean exposure (days) | 586.4 | ||

| Median exposure (days) | 504.5 | ||

| Range of exposure (days), min–max | 8–1219 | ||

| n (%) | EAIR | 95% CI | |

| Death | 6 (0.4) | 0.3 | 0.1 to 0.6 |

| AE leading to discontinuation (including death) | 115 (8.2) | 5.1 | 4.3 to 6.1 |

| SAE* | 134 (9.6) | 6.0 | 5.0 to 7.1 |

| Injection site reactions (broad term) | 1 (0.1) | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.3 |

| Allergic reactions/hypersensitivities | 2 (0.1) | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| Malignancies | 7 (0.5) | 0.3 | 0.1 to 0.7 |

| NMSC | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| Malignancies excluding NMSC | 7 (0.5) | 0.3 | 0.1 to 0.7 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease† | 2 (0.1) | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| Depression‡ | 1 (0.1) | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.3 |

| Suicidal behaviour/self-injury | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| MACE† | 12 (0.9) | 0.5 | 0.3 to 0.9 |

| Cytopaenia§ | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| TEAE¶ | 1131 (80.7) | 50.3 | 47.5 to 53.3 |

| Mild | 461 (32.9) | 20.5 | 18.7 to 22.5 |

| Moderate | 556 (39.7) | 24.7 | 22.8 to 26.9 |

| Severe | 114 (8.1) | 5.1 | 4.2 to 6.1 |

| Most common TEAEs** | |||

| Nasopharyngitis | 202 (14.4) | 9.0 | 7.8 to 10.3 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 186 (13.3) | 8.3 | 7.2 to 9.6 |

| Injection site reaction†† | 156 (11.1) | 6.9 | 5.9 to 8.1 |

| Bronchitis | 91 (6.5) | 4.0 | 3.3 to 5.0 |

| Sinusitis | 77 (5.5) | 3.4 | 2.7 to 4.3 |

*Data collection for the clinical trial database does not specify when events became serious and therefore the numbers shown may represent more serious events than what actually occurred during the treatment period.

†Data represent adjudicated cases.

‡Broad, according to Standardised MedDRA Queries (SMQ) or sub-SMQ classification.

§Broad, according to SMQ classification.

¶Patients with multiple occurrences of the same event are counted under the highest severity.

**Defined as frequency of TEAE ≥5%.

††Narrow term.

AE, adverse event; EAIR, exposure-adjusted incidence rate per 100 patient-years; IXE, ixekizumab; MACE, major adverse cerebro-cardiovascular event; min–max, minimum–maximum; N, number of patients in the analysis population; n, number of patients in each category; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SAE, serious adverse event; SMQ, Standardised MedDRA Queries; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Overall, TEAEs occurred in 80.7% (50.3 per 100 PY) of patients (table 2). Most TEAEs were mild (32.9%) or moderate (39.7%). The most frequently reported TEAEs (≥5%) were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, ISR (narrow term), bronchitis and sinusitis. Serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred in 9.6% (EAIR=6.0) of patients. A total of 134 patients reported an SAE (9.6%); 123 cases led to hospitalisation (8.8%, EAIR=5.5), 3 events were life-threatening (0.2%, EAIR=0.1), 2 events led to disability (0.1%, EAIR=0.1) and 6 were fatal (0.4%, EAIR=0.3). The causes of death were cardiovascular event (n=2), metastatic renal cell carcinoma (n=1), cerebrovascular accident (n=1), pneumonia (n=1) and drowning (n=1). Overall, discontinuation from the study drug due to AEs was reported by 8.2% (EAIR=5.1) of patients. Among patients who discontinued, 1.4% were due to latent tuberculosis, followed by 0.4% of ISR (narrow term) and pneumonia (0.2%). There were four reported cases of pregnancy during ixekizumab exposure (online supplemental table 1).

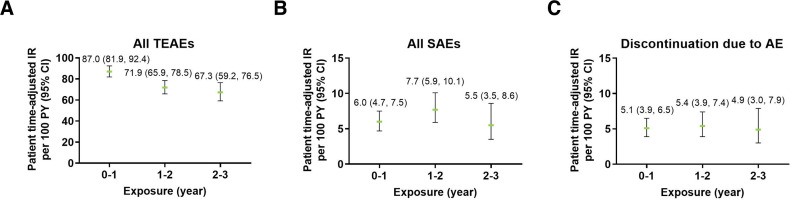

TEAEs were more common during the first year of ixekizumab exposure (EAIR=87.0) and decreased over time (EAIR=67.3 in the third year of exposure) (figure 1). EAIRs for SAEs and discontinuations remained consistent over time.

Figure 1.

Exposure-adjusted incidence rate of (A) TEAEs, (B) SAEs and (C) discontinuation due to AEs (exposure safety populations). The data points on the graph are the EAIR (95% CI)/100 patient-years at successive year intervals from year 0 to year 3. The CIs for the EAIR are from the likelihood ratio test of treatment effect from the Poisson regression model. AE, adverse event; EAIR, exposure-adjusted incidence rate; IR, incidence rate; PY, patient-years; SAE, serious adverse events; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Infections

Infections were reported by 54.2% of patients (EAIR=33.8) (table 3). Most cases of infections were mild (29.6%) or moderate (23.3%). The most common types of infections (EAIR >2.0) were nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, bronchitis, sinusitis, urinary tract infection and pharyngitis (table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of infections

| |

Integrated IXE PsA N=1401 |

||

| n (%) | EAIR | 95% CI | |

| Infections | 759 (54.2) | 33.8 | 31.4 to 36.3 |

| Mild | 415 (29.6) | 18.5 | 16.8 to 20.3 |

| Moderate | 326 (23.3) | 14.5 | 13.0 to 16.2 |

| Severe | 18 (1.3) | 0.8 | 0.5 to 1.3 |

| Most common infections* | |||

| Nasopharyngitis | 202 (14.4) | 9.0 | 7.8 to 10.3 |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 186 (13.3) | 8.3 | 7.2 to 9.6 |

| Bronchitis | 91 (6.5) | 4.0 | 3.3 to 5.0 |

| Sinusitis | 77 (5.5) | 3.4 | 2.7 to 4.3 |

| Urinary tract infection | 69 (4.9) | 3.1 | 2.4 to 3.9 |

| Pharyngitis | 54 (3.9) | 2.4 | 1.8 to 3.1 |

| Serious infections | 28 (2.0) | 1.2 | 0.9 to 1.8 |

| Opportunistic infections | 40 (2.9) | 1.8 | 1.3 to 2.4 |

| Oral candidiasis | 16 (1.1) | 0.7 | 0.4 to 1.2 |

| Oral fungal infection† | 6 (0.4) | 0.3 | 0.1 to 0.6 |

| Oesophageal candidiasis‡ | 2 (0.1) | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| Herpes zoster | 16 (1.1) | 0.7 | 0.4 to 1.2 |

| Hepatitis B virus reactivation | 1 (0.1) | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.3 |

| Latent tuberculosis§ | 35 (2.5) | 1.6 | 1.1 to 2.2 |

| Candida infections | 45 (3.2) | 2.0 | 1.5 to 2.7 |

| Oral candidiasis¶ | 22 (1.6) | 1.0 | 0.6 to 1.5 |

| Vulvovaginal candidiasis** | 13 (1.8) | 1.1 | 0.7 to 2.0 |

| Skin candidiasis | 5 (0.4) | 0.2 | 0.1 to 0.5 |

| Genital candidiasis | 3 (0.2) | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| Oesophageal candidiasis‡ | 2 (0.1) | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| Nail candidiasis | 1 (0.1) | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.3 |

| Systemic candidiasis | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| Viral infections | |||

| Viral upper respiratory tract infections | 25 (1.8) | 1.1 | 0.8 to 1.6 |

| Viral respiratory tract infections | 9 (0.6) | 0.4 | 0.2 to 0.8 |

| Influenza | 38 (2.7) | 1.7 | 1.2 to 2.3 |

A patient could present more than one event.

*Defined as EAIR of TEAE >2.0.

†As reported by investigator.

‡Data included one case considered severe and one case considered moderate.

§Data include cases of latent tuberculosis, interferon-gamma release assay positive, tuberculin test positive and Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex test positive.

¶Oral candidiasis infection includes oral candidiasis and oral fungal infection.

**Denominator adjusted due to gender-specific event for women: n=722, patient-years=1142.2 (pooled IXE).

EAIR, exposure-adjusted incidence rate per 100 patient-year; IXE, ixekizumab; n, number of patients in each category; N, number of patients in the analysis population; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

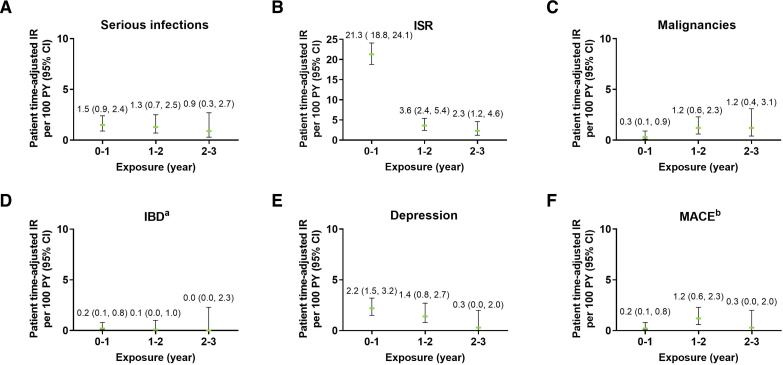

The frequency of serious infections was low (2.0%, EAIR=1.2) (table 3). A total of 28 patients with serious infections were reported (total of 33 events). Most serious infections were fully recovered or resolved (n=27, 81.8%), three patients recovered with sequelae (9.1%), one patient was recovering or resolving (3.0%), one patient did not recover (3.0%), and the outcome was fatal in one patient (3.0%). The EAIRs of serious infections were relatively stable for each of the 1-year periods (range 0.9 to 1.5) (figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Exposure-adjusted incidence rate of selected adverse events including (A) serious infections, (B) ISR, (C) malignancies, (D) IBD, (E) depression, and (F) MACE. The data points on the graph are the EAIR (95% CI)/100 patient-years at successive year intervals from year 0 to year 5. The CIs for the EAIRs are from the likelihood ratio test of treatment effect from the Poisson regression model. aData represent cases classified as ‘definite’ and ‘probable’ per external adjudication. Three patients had events of IBD confirmed by adjudication. One patient had more than one event. bData represent events confirmed after adjudication. EAIR, exposure-adjusted incidence rates; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IR, incidence rate; ISR, injection site reactions; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; PY, patient-years.

Overall, the frequency of OIs was low (2.9%, EAIR=1.8) (table 3). A total of 40 participants reported OIs, which were mainly oral (n=16) and oesophageal (n=2) candidiasis, oral fungal infection (n=6), localised herpes zoster (n=16) and one case of hepatitis B reactivation. The case of hepatitis B reactivation occurred in a 47-year-old white patient with concomitant use of sulfasalazine. On annual tuberculosis testing, 35 patients who were originally negative at entry in the trials had a positive test (2.5%, EAIR=1.6); positive tuberculosis test led to discontinuation for 10 patients according to protocols. The 25 remaining patients who did not discontinue the study received treatment for latent tuberculosis infection prior to resuming the study drug. Most new cases of latent tuberculosis occurred in patients from countries at high risk of tuberculosis (online supplemental table 2; WHO list).19 No cases of latent tuberculosis resulted in death, and there were no existing latent cases that presented any sign of active tuberculosis disease.

Candida infections were reported by 3.2% (EAIR=2.0) of patients (table 3). All cases of Candida infection were localised; most were mild (34 of 45) to moderate (10 of 45) in severity, except one case of oesophageal candidiasis which was considered severe. The patient who reported severe oesophageal candidiasis did not discontinue the study drug due to this AE. No cases of systemic candidiasis were reported in patients receiving ixekizumab. Serious Candida infections occurred in three patients (two cases of oesophageal candidiasis, one case of oral candidiasis), which all recovered or resolved. Each of these three patients only had one event of Candida infection.

Frequencies of viral infections were low (table 3). Viral upper respiratory tract infections were reported by 1.8% of patients (EAIR=1.1), viral respiratory tract infections occurred in 0.6% of patients (EAIR=0.4) and influenza was reported in 2.7% of patients (EAIR=1.7). No cases of viral infection led to trial discontinuation.

ISRs and hypersensitivity/allergic reactions

Overall, TEAEs of ISRs were relatively common and occurred in 18.6% of patients (EAIR=11.6) (table 4). ISRs were mainly mild (14.8%) to moderate (3.4%) in severity. Severe cases were rare (0.4%) and one serious case was reported which was an event of injection site rash (table 2). ISRs were the cause of discontinuation of the study drug for nine patients. The most common types of ISRs were ISR (preferred term; 11.1%), injection site erythema (4.3%) and injection site pain (1.6%). The mean time from start of treatment to first occurrence of ISR events was 59 days (±108.2). The incidence of new events of ISRs decreased over time from an EAIR of 21.3 in the first year period to 2.3 between years 2 and 3 (figure 2B).

Table 4.

Selected adverse events of interest

| Integrated IXE PsA N=1401 |

|||

| n (%) | EAIR | 95% CI | |

| Injection site reactions (broad term) | 260 (18.6) | 11.6 | 10.2 to 13.1 |

| Mild | 207 (14.8) | 9.2 | 8.0 to 10.6 |

| Moderate | 48 (3.4) | 2.1 | 1.6 to 2.8 |

| Severe | 5 (0.4) | 0.2 | 0.1 to 0.5 |

| Allergic reactions/hypersensitivity | 102 (7.3) | 4.5 | 3.7 to 5.5 |

| Malignancies | 15 (1.1) | 0.7 | 0.4 to 1.1 |

| NMSC | 9 (0.6) | 0.4 | 0.2 to 0.8 |

| Malignancies excluding NMSC | 7 (0.5) | 0.3 | 0.1 to 0.7 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease* | 3 (0.2) | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| Crohn’s disease | 2 (0.1) | 0.1 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1 (0.1) | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.3 |

| Depression† | 37 (2.6) | 1.6 | 1.2 to 2.3 |

| Suicidal behaviour/self-injury | 1 (0.1) | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.3 |

| MACE‡ | 12 (0.9) | 0.5 | 0.3 to 0.9 |

| Cytopaenia§ | 56 (4.0) | 2.5 | 1.9 to 3.2 |

| Asthma | 10 (0.7) | 0.4 | 0.2 to 0.8 |

| Uveitis | 0 (0.0) | 0.0 | 0.0 to 0.4 |

*Data represent cases classified as ‘definite’ and ‘probable’ per external adjudication. EAIR was calculated as the total of ‘definite’ and ‘probable’ cases/total patient-years, then multiplied by 100. One patient had reported event of anal abscess and anal fistula and this event was considered consistent with inflammatory bowel disease but was not adjudicated as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis due to insufficient information. Three patients had events of inflammatory bowel disease confirmed by adjudication. One patient had more than one event.

†Broad, according to SMQ or sub-SMQ classification.

‡Data represent adjudicated cases.

§Broad, according to SMQ classification.

EAIR, exposure-adjusted incidence rate per 100 patient-years; IXE, ixekizumab; MACE, major adverse cerebro-cardiovascular event; n, number of patients in each category; N, number of patients in the analysis population; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; SMQ, Standardised MedDRA Queries.

Overall, 7.3% (EAIR=4.5) of patients reported an event of allergic reaction or hypersensitivity (table 4). The most frequently reported events were rash (1.4%, EAIR=0.8), eczema (1.1%, EAIR=0.7), drug hypersensitivity (0.7%, EAIR=0.4) and allergic rhinitis (0.7%, EAIR=0.4). TEAEs of allergic reaction or hypersensitivity were more frequently reported after 1 day of injection and before the next injection. All reported events were mild (4.1%) to moderate (3.1%) in severity except for one severe case. Most cases were non-serious; two serious cases were identified (one case of angio-oedema and one case of bronchospasm) and both have recovered or resolved (table 2). No cases of anaphylaxis were confirmed after medical reviews. Also, available data do not support any association between immunogenicity and TEAEs.

Malignancies

In this study, malignancies were reported by a total of 15 patients (1.1%, EAIR=0.7), which included 8 patients (0.6%, EAIR=0.4) with NMSC and 7 patients (0.5%, EAIR=0.3) with malignancies other than NMSC (table 4). Overall, seven cases were serious: one event was fatal, three events recovered, two did not recover and one recovering (table 2). TEAE of malignancy was the cause of discontinuation of the study drug for eight patients (seven of these patients had a serious event of malignancy). The mean time from start of the treatment to onset of malignancy was 509.8 days. NMSC cases all occurred in white patients 50 years old or older and most cases were localised on the face. One of the patients also presented melanoma. Malignancies other than NMSC occurred in patients over 52 years old at diagnosis and included prostate cancer (n=1), breast cancer (n=2), gastrointestinal stromal tumours (n=1), thyroid carcinoma (n=1) and metastatic renal cell cancer (n=1) in a female with history of smoking. EAIRs were evenly distributed over time (figure 2C).

Inflammatory bowel disease

A total of three patients (0.2%, EAIR=0.1) had IBD confirmed per adjudication as Crohn’s disease (n=2, EAIR=0.1) or ulcerative colitis (n=1, EAIR=0.0) (table 4). None of these patients had medical history of IBD. One patient was a 55-year-old white man who reported five TEAEs of IBD, which were all adjudicated as ulcerative colitis: four were mild or moderate and one was severe. All these events recovered or resolved except the last event with an unknown outcome. Time from ixekizumab exposure to onset of the first IBD events was 351 days, with four subsequent events. Another patient was a 28-year-old white woman who had one event categorised as moderate IBD (adjudicated as Crohn’s disease) and did not recover and led to discontinuation of the study drug. This patient reported IBD at 183 days after exposure to ixekizumab. The last patient, a 64-year-old white woman, experienced a moderate IBD event (adjudicated as Crohn’s disease) that was resolving or recovering at the time of the data lock. This IBD event was reported at 113 days after ixekizumab exposure. Among the three confirmed cases, two were serious (0.1%, EAIR=0.1) (table 2). As assessed in exposure period analyses, the incidence of IBD was low (EAIR ≤0.6) and stable over time (figure 2D).

Depression and suicidal behaviour/self-injury

A total of 37 patients (2.6%, EAIR=1.6) reported a TEAE of depression (broad term) (table 4). The most common subcategories of depression were depression (n=25, 1.8%), depressed mood (n=6, 0.4%) and adjustment disorder with depressed mood (n=2, 0.1%). One case of suicidal ideation was reported which led to discontinuation of the study drug, with the outcome unknown at the time of data lock. Many of these patients presented medical history of psychiatric disorders (n=18, 48.6%), including depression (n=12, 32.4%), anxiety (n=5, 13.5%), insomnia (n=5, 13.5%), sleep disorder (n=3, 8.1%), adjustment disorder with depressed mood (n=1, 2.7%), alcoholism (n=1, 2.7%), personality disorder (n=1, 2.7%) or post-traumatic stress disorder (n=1, 2.7%). The incidence of new events of depression decreased over time from an EAIR of 2.2 per the first year period to 0.3 between years 2 and 3 (figure 2E).

Major adverse cerebro-cardiovascular events

Per adjudication, 12 patients (0.9%, EAIR=0.5) reported MACE, which included 3 moderate and 9 severe cases (table 4). All these events were serious; two were fatal and ten resolved or recovered, including one with sequelae. Most patients (n=9, 75.0%) presenting MACE had pre-existing cardiovascular risk factors (eg, hypertension, Raynaud’s phenomenon, hypercholesterolaemia, dyslipidaemia and obesity). As assessed in exposure period analyses, the incidence of MACE was stable over time and ranged in EAIR from 0.2 to 1.2 (figure 2F).

Other selected AEs

Cytopaenia (broad term) occurred in 4% of patients (EAIR=2.5) (table 4). The severity was comparable with those reported previously and no new safety signals were identified.20 Asthma was reported by 0.7% of patients (EAIR=0.4). No cases of uveitis were reported.

Safety profile of two ixekizumab regimens

The safety profile of the two ixekizumab regimens, every 2 weeks and every 4 weeks, showed no apparent differences (online supplemental table 3).

Discussion

In this analysis we reported the updated safety profile of ixekizumab in 1401 patients with PsA across four clinical trials for up to 3 years of ixekizumab. Because of the chronic nature of the disease, long-term pharmaceutical management of PsA is required to maintain adequate disease control. In the current analysis, the long-term ixekizumab exposure did not increase the exposure-adjusted rates of TEAEs and SAEs reported in previous safety reports.10 11 20 As assessed, EAIRs were decreasing or constant over time. The data reported in this analysis of patients with PsA are consistent with the known safety profile in the entire ixekizumab clinical development programme.20

In this study, the EAIR of SAEs was 6.0 per 100 PY (9.6% of patients reporting SAEs). In a long-term safety analysis of patients with PsA treated with another IL-17A inhibitor, secukinumab, the rate of SAEs was 7.9 per 100 PY.21

An integrated post-hoc analysis of the safety profile of the two ixekizumab regimens (80 mg of ixekizumab every 2 weeks and every 4 weeks) was conducted. This report shows that, although the studies were not powered to detect statistical differences between the two ixekizumab regimens, there are no apparent differences in the safety between ixekizumab every 2 weeks and every 4 weeks. This analysis is consistent with the safety profile of the two treatment regimens previously published.14 15

The most common TEAEs were infections (including nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection) and ISRs. The EAIRs of serious infections and ISRs (broad term) did not increase over time through 3 years of ixekizumab treatment. Most events of infections and ISRs were mild to moderate in severity and the frequency of serious events was low (≤2%). The frequency of OIs was low (2.9%), which were mainly oral and oesophageal candidiasis, probably due to the known role of IL-17A in host defence against these infections. In this analysis, the new positive tuberculosis test on annual testing was 2.5%. Among the 35 patients with new positive tuberculosis test, 10 patients discontinued the study drug according to protocols and 25 patients received treatment for latent tuberculosis infection prior to resuming the study drug. No cases of active tuberculosis disease were reported. Treatment with IL-17 inhibitor has not been associated with an increased risk of active tuberculosis.22 A recent study reported that new latent tuberculosis cases were rare, while patients with psoriasis, PsA or ankylosing spondylitis underwent treatment with the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab.23 Similarly, this analysis did not suggest a relationship between ixekizumab and increased risk of active tuberculosis in patients with PsA. In the present report, no cases of anaphylaxis occurred. Available data do not support an association between immunogenicity and TEAEs.

Patients with PsA have a twofold to threefold increased risk of onset of IBD compared with the general population.24 25 In this report, three patients (0.2%, EAIR=0.1) reported a confirmed IBD and one event led to discontinuation of the study drug. The EAIRs for IBD did not increase over time through 3 years of ixekizumab treatment.

A recent meta-analysis showed that the prevalence of cancer overall in patients with PsA is 5.74%, with an incidence rate of 6.44 per 1000 PY.26 In this study, malignancies were reported by 1.1% of patients receiving ixekizumab (EAIR=0.7 per 100 PY). Although the denominator is different in the meta-analysis than this report (1000 PY vs 100 PY), the incidence rate of malignancies in patients with PsA receiving ixekizumab treatment is in accordance with the incidence rate of cancer in patients with PsA.

Study length is important when investigating safety events. A strength of this report is that it includes the longest cumulative exposure reported to date of ixekizumab-treated patients with PsA with 2247.7 PY and up to 3 years. Nevertheless, this study is limited by the lack of a suitable long-term control group and a limited cohort of patients. Another limitation of this study is the prespecified inclusion criteria in clinical trials, potentially resulting in a study population which may not reflect the breadth of patients in the real-world clinical setting.

To conclude, the overall safety profile and tolerability of ixekizumab are consistent with the previously known safety profile in patients with PsA. No new or unexpected safety events were detected. These findings are of value to physicians who treat patients in the long term with PsA using IL-17A antagonists.

Acknowledgments

Elsa Mevel, PhD, provided writing and editorial assistance. The author wishes to thank Himanshu Patel, MD, for his assistance in data analysis.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Josef S Smolen

Contributors: All authors contributed to the analysis of data and interpretation of data and provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. GRB is guarantor.

Funding: Funding for editorial assistance was provided by Eli Lilly and Company.

Competing interests: AAD reports consulting and advisory boards for AbbVie, Amgen, Aurinia, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB; and research grants from AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB. BC has received grant/research support from Novartis, Pfizer and Roche-Chugai; served as a consultant for AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Pfizer, Roche-Chugai and Sanofi; and served on speakers’ bureaus for Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer and Roche-Chugai. APA, DZ, RB, AMG and ATS are shareholders and employees of Eli Lilly and Company. G-RRB is a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer; and has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Company.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants. SPIRIT-P1 was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (approval #1-838258-1), SPIRIT-P2 by the Bellberry Human Research Ethics Committee (application #2015-01-049-AA), SPIRIT-P3 by the Institutional Review Board (tracking number #20151638) and SPIRIT-H2H by the ethical review board (17/LO/0794). For all studies, approval was also obtained from each additional site. All studies were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Ritchlin CT, Colbert RA, Gladman DD. Psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:957–70. 10.1056/NEJMra1505557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gladman DD, Antoni C, Mease P, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, clinical features, course, and outcome. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64 Suppl 2:ii14–17. 10.1136/ard.2004.032482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferguson LD, Siebert S, McInnes IB, et al. Cardiometabolic comorbidities in RA and PsA: lessons learned and future directions. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2019;15:461–74. 10.1038/s41584-019-0256-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fernández-Carballido C, Martín-Martínez MA, García-Gómez C, et al. Impact of comorbidity on physical function in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis attending rheumatology clinics: results from a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Care Res 2020;72:822–8. 10.1002/acr.23910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coates LC, Soriano E, Corp N, et al. OP0229 the group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (GRAPPA) treatment recommendations 2021. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:139–40. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.4091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu L, Lu J, Allan BW, et al. Generation and characterization of ixekizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody that neutralizes interleukin-17A. J Inflamm Res 2016;9:39–50. 10.2147/JIR.S100940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Toussirot E. Ixekizumab: an anti- IL-17A monoclonal antibody for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2018;18:101–7. 10.1080/14712598.2018.1410133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Paller AS, Seyger MMB, Alejandro Magariños G, Magariños G, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in paediatric patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IXORA-PEDS). Br J Dermatol 2020;183:231–41. 10.1111/bjd.19147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prescribing Information - Taltz. Available: http://uspl.lilly.com/taltz/taltz.html#pi [Accessed 23 Apr 2020].

- 10. Mease P, Roussou E, Burmester G-R, et al. Safety of ixekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis: results from a pooled analysis of three clinical trials. Arthritis Care Res 2019;71:367–78. 10.1002/acr.23738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Combe B, Rahman P, Kameda H, et al. Safety results of ixekizumab with 1822.2 patient-years of exposure: an integrated analysis of 3 clinical trials in adult patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2020;22:14. 10.1186/s13075-020-2099-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chandran V, van der Heijde D, Fleischmann RM, et al. Ixekizumab treatment of biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 3-year results from a phase III clinical trial (SPIRIT-P1). Rheumatology 2020;59:2774–84. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Orbai A-M, Gratacós J, Turkiewicz A, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis and inadequate response to TNF inhibitors: 3-year follow-up (SPIRIT-P2). Rheumatol Ther 2021;8:199–217. 10.1007/s40744-020-00261-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, Ritchlin CT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:79–87. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nash P, Kirkham B, Okada M, et al. Ixekizumab for the treatment of patients with active psoriatic arthritis and an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled period of the SPIRIT-P2 phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;389:2317–27. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31429-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mease PJ, Smolen JS, Behrens F, et al. A head-to-head comparison of the efficacy and safety of ixekizumab and adalimumab in biological-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a randomised, open-label, blinded-assessor trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:123–31. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coates LC, Pillai SG, Tahir H, et al. Withdrawing ixekizumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis who achieved minimal disease activity: results from a randomized, double-blind withdrawal study. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73:1663–72. 10.1002/art.41716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Winthrop KL, Novosad SA, Baddley JW, et al. Opportunistic infections and biologic therapies in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: consensus recommendations for infection reporting during clinical trials and postmarketing surveillance. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:2107–16. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization . Use of high burden country Lists for TB by WHO in the post-2015 era: summary, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/high_tb_burdencountrylists2016-2020summary.pdf?ua=1#:~:text=The%2030%20TB%20HBCs%20(those,%2C%20Russian%20Federation%2C%20Sierra%20Leone%2C2021

- 20. Genovese MC, Mysler E, Tomita T, et al. Safety of ixekizumab in adult patients with plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: data from 21 clinical trials. Rheumatology 2020;59:3834–44. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deodhar A, Mease PJ, McInnes IB, et al. Long-Term safety of secukinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: integrated pooled clinical trial and post-marketing surveillance data. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:111. 10.1186/s13075-019-1882-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Romiti R, Valenzuela F, Chouela EN, et al. Prevalence and outcome of latent tuberculosis in patients receiving ixekizumab: integrated safety analysis from 11 clinical trials of patients with plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2019;181:202–3. 10.1111/bjd.17604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Elewski BE, Baddley JW, Deodhar AA, et al. Association of Secukinumab treatment with tuberculosis reactivation in patients with psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or ankylosing spondylitis. JAMA Dermatol 2021;157:43–51. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Makredes M, Robinson D, Bala M, et al. The burden of autoimmune disease: a comparison of prevalence ratios in patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;61:405–10. 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stolwijk C, Essers I, van Tubergen A, et al. The epidemiology of extra-articular manifestations in ankylosing spondylitis: a population-based matched cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:1373–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vaengebjerg S, Skov L, Egeberg A, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156:421–9. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2021-222027supp001.pdf (83.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.