Abstract

The protein kinase, TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), not only regulates various biological processes but also functions as an important regulator of human oncogenesis. However, the detailed function and molecular mechanisms of TBK1 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), especially the resistance of HCC cells to molecular-targeted drugs, are almost unknown. In the present work, the role of TBK1 in regulating the sensitivity of HCC cells to molecular-targeted drugs was measured by multiple assays. The high expression of TBK1 was identified in HCC clinical specimens compared with paired non-tumor tissues. The high level of TBK1 in advanced HCC was associated with a poor prognosis in patients with advanced HCC who received the molecular-targeted drug, sorafenib, compared to patients with advanced HCC patients and a low level of TBK1. Overexpression of TBK1 in HCC cells induced their resistance to molecular-targeted drugs, whereas knockdown of TBK1 enhanced the cells’ sensitivity to molecular-targeted dugs. Regarding the mechanism, although overexpression of TBK1 enhanced expression levels of drug-resistance and pro-survival-/anti-apoptosis-related factors, knockdown of TBK1 repressed the expression of these factors in HCC cells. Therefore, TBK1 is a promising therapeutic target for HCC treatment and knockdown of TBK1 enhanced sensitivity of HCC cells to molecular-targeted drugs.

Keywords: TANK-binding kinase 1, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, molecular-targeted drugs, epithelialmesenchymal transition, drug resistance, pro-survival, anti-apoptosis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common and frequent primary liver tumor, and its risk factors are mainly viral hepatitis and alcohol abuse (Lin et al., 2020; Nhlane et al., 2021; Powell et al., 2021). Despite the progress made in neonatal Hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination and HBV anti-tumor symptomatic treatment, there are still more than 80 million people infected with HBV and other hepatitis viruses (HCV) in China (Polaris Observatory Collaborators, 2018; Sung et al., 2021; Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators, 2022). Due to the high HBV and HCV infection rates in East Asia and the Asia-Pacific region represented by China, and as the diseases progress, patients have a high risk of eventually developing HCC (Wang et al., 2014; Zhang S et al., 2017; Tan and Schreiber, 2020). HCC has an insidious onset and a long disease course (Wang et al., 2014; Zhang S et al., 2017; Tan and Schreiber, 2020). Most patients are in an advanced stage at the first diagnosis and cannot receive radical treatment strategies such as liver transplantation or surgical resection (Kim et al., 2017; Llovet et al., 2018; Wang and Wei, 2020). For advanced HCC, one of the main drug treatment strategies is molecular-targeted therapy: patients orally take various small-molecule, multi-target protein kinase inhibitors (Roskoski, 2019; Roskoski, 2020; Roskoski, 2021; Roskoski, 2022). Although global, multi-center clinical trials show that these molecular-targeted drugs can help delay disease progression in patients with HCC, improve patients’ quality of life, and prolong patients’ survival (Bruix et al., 2017; Kudo et al., 2018), these drugs still have many shortcomings: 1) individual differences in patients with advanced HCC on molecular-targeted drugs treatment are very large, and only some patients are sensitive to molecular-targeted drugs (Zhu et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2020); 2) the treatment cycle of molecular-targeted drugs is very long, and patients are prone to develop drug resistance as treatment progresses (Zhu et al., 2017); and 3) these drugs are toxic and side effects of molecular-targeted drugs cannot be ignored (Zhu et al., 2017). Although many advances have been made in research on molecular-targeted drugs, the molecular mechanisms leading to drug resistance in HCC is still unclear and there is no ideal indicator molecule to signal the prognosis of patients receiving molecular-targeted drug therapy (Zhu et al., 2017). Therefore, there is a great need to elucidate the molecular mechanism of HCC resistance to molecular-targeted drugs and to study and discover new intervention targets to achieve safer and more effective molecular-targeted therapy.

As a member of the ubiquitous serine/threonine kinases that play important roles in regulating immune or inflammatory responses, the TRAF-associated NF-κB activator (TANK) binding kinase 1 (TBK1) has been considered as a therapeutic target (Li et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2020; Taft et al., 2021). It was initially considered an activator of the NF-κB pathway via inhibiting the activation of the IKK [inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB (IκB) kinase]-related pathway (Alam et al., 2021). Recently, aberrant TBK1 expression and/or activity have been identified in various human malignancies, including lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and colorectal cancer (Revach et al., 2020; Alam et al., 2021; Herhaus, 2021). TBK1 has also been considered to be an oncogene (Revach et al., 2020; Alam et al., 2021; Herhaus, 2021). However, the roles of TBK1 in HCC are still unclear. Moreover, inflammation is closely related to the occurrence and progression of tumors (Donisi et al., 2020; Heinrich et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021). NF-κB and its related signaling pathways not only play an important role in the body’s immune response and physiological mechanisms such as inflammation but also promote the occurrence and progression of various malignant tumors (Yang et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2021a; Zhou Q et al., 2021). In addition, NF-κB can also induce the resistance of malignant tumor cells to anti-tumor drugs (Ding et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2021; Smith and Burger, 2021). To this end, the present study intends to systematically investigate the molecular mechanism by which TBK1 regulates the resistance of HCC cells to molecular-targeted drugs. Exploring the significance of TBK1 as an intervention target sensitize HCC cells to molecularly-targeted drugs is of great value.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines and Vectors

The cell lines used in this study were mainly liver-derived, non-tumor cell lines (L-02) and some HCC cell lines (including MHCC97-H, MHCC97-L, HepG2, Huh-7, BEL-7402, and SMMC-7721). These cell lines are maintained in our laboratory and detailed in previous publications (He X et al., 2021; Yang H et al., 2021; Jiang Q et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). The expression levels assessed in these experiments included the full-length sequence of TBK1 and its siRNA, which were prepared as the lentivirus (these were transduced into lentivirus vectors). The target sequence of TBK1 siRNA was 5′-TAAACTTCTATTAGAAAGCTA-3′ and siTBK1 was used in pcilencer2.1U6 vectors. All sequences were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The cells were infected with the viral vectors and cells with the neomycin-resistance selectable marker were screened and selected by treatment with G418.

Clinical Specimens and qPCR

Clinical tissue specimens were obtained from patients with advanced HCC (52 patients) and paired, non-tumor tissues from the same patients were also obtained. These specimens were maintained in our laboratory and used as detailed in previous publications (Feng et al., 2018; Shao et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). The expression levels of TBK1 and other factors were examined by qPCR according to previous publications and manufacturer instructions. The primers used in these experiments were: E-cadherin, 5′-CTCCTGAAAAGAGAGTGGAAGTGT-3′; 5′-CCGGATTAATCTCCAGCCAGTT-3′; N-cadherin, 5′-CCTGGATCGCGAGCAGATA-3′; 5′-CCATTCCAAACCTGGTGTAAGAAC-3′; vimentin, 5′-ACCGCACACAGCAAGGCGAT-3′; 5′-CGATTGAGGGCTCCTAGCGGTT-3′; BCL2, 5′-GATCGTTGCCTTATGCATTTGTTTTG-3′; 5′-CGGATCTTTATTTCATGAGGCAC GTTA-3′; NICD (Notch NICD, the intracellular domain of Notch protein), 5′-CCGACGCACA AGGTGTCTT-3′, 5′-GTCGGCGTGTGAGTTGATGA-3′; survivin, 5′-ACATGCAGCTCGAATG AGAACAT-3′, 5′-GATTCCCAACACCTCAAGCCA-3′; cIAP-1, 5′-GTGTTCTAGTTAATCCTG AGCAGCTT-3′; 5′-TGGAAACCACTTGGCATGTTGA-3′; cIAP-2, 5′-CAAGGACCACCG CATCTCT-3′; 5′-AGCTCCTTGAAGCAGAAGAAACA-3′; TBK1, 5′-CCCTTTGAAGGGC CTCGTAG-3′; 5′-ACCCCGAGAAAGACTGCAAG-3′; NF-κB p50 (NFKB), 5′-TTTTCG ACTACGCGGTGACA-3′; 5′-TCCTGCACAGCAGTGAGATG-3′; NF-κB p65 (RELA), 5′-TGAACCGAAACTCTGGCAGCTG-3′; 5′-CATCAGCTTGCGAAAAGGAGCC-3′; and loading control β-actin, 5′-CACCATTGGCAATGAGCGGTTC-3′; 5′-AGGTCTTTGCGGATGTCCA CGT-3′. The heat-map of the qPCR results were obtained according to the methods by Zhou et al., 2020 and Yin et al., 2019 (Yin et al., 2019; Zhou W et al., 2021). The results of qPCR are displayed as heat maps, and the heat maps are drawn based on the relative folds of the expression levels of each factor in each group relative to the control group. At this time, the control group itself has no change compared with itself, so the folds of change is 0, the increase is a positive number of folds, and the decrease is a negative number folds. Each heat-map has a colored ribbon as an indication of the rates/folds of changes.

Cell-Survival Analysis

The following molecularly-targeted drugs used in this study were obtained by Dr. Cao Shuang of Wuhan Engineering University through chemical synthesis: sorafenib, regorafenib, lenvatinib, cabozantinib, and anlotinib. All pure-drug powders with a purity of greater than 99% were used in this study (see Table 1 referring to the purity of drugs via HPLC [High Performance Liquid Chromatography]). For the cytotoxic chemotherapeutics, etoposide (Cat. No. S1225), adriamycin (Cat. No. S1208), paclitaxel (Cat. No. S1150) or gemcitabine (Cat. No. S1714) was purchased from Selleck Corporation, Houston, Texas, United States. The small molecular inhibitor of TBK1 (MRT67307, Cat. No. S6386) was purchased from Selleck Corporation. For cell experiments, pure powders of these drugs were dissolved in organic solvents, such as DMSO (Dimethyl sulfoxide), according to previous publications (Ma et al., 2016; Wang J. H et al., 2021), then diluted in DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium) without FBS (fetal bovine serum). The concentration of molecular-targeted drugs used in the cell-survival analysis were: 30 μmol/L, 10 μmol/L, 3 μmol/L, 1 μmol/L, 0.3 μmol/L, 0.1 μmol/L, 0.03 μmol/L, and 0.01 μmol/L. The concentrations of cytotoxic chemotherapeutics were listed in Table 2. The cells were treated with various concentrations of the drugs for 48 h and counts of living cells were determined by the MTT assay. The inhibitory rates, or the IC50 values (half rate of inhibition), of the drugs on HCC cell survival were calculated according to previously published methods (Ma et al., 2016; Wang J. H et al., 2021).

TABLE 1.

The purity of drugs used in the presence work from HPLC.

| Drugs | Purity from HPLC (%) |

|---|---|

| Sorafenib | 99.1 |

| Cabozentinib | 99.5 |

| Lenvatinib | 99.3 |

| Regorafenib | 99.2 |

| Anlotinib | 99.5 |

TABLE 2.

The concentrations of cytotoxic chemotherapies in cell-based assays.

| Drugs | Concentrations (μmol/L) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| paclitaxel | 0.0003 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| etoposide | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 | 3 |

| adriamycin | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 |

| gemcitabine | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1 |

Subcutaneous Tumor Model

First, the sorafenib solution used in the animal experiments was prepared according to the method described in a previous publication (Jia et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2019). Specifically, pure sorafenib powder was dissolved in PEG400 (polyethylene glycol 400), Tween 80, and DMSO, then diluted with sterilized normal saline (Wang Y et al., 2021; Du et al., 2021; Jie et al., 2021; Zou et al., 2021). The final dose of sorafenib formulation used for treating the nude mice by oral administration was approximately 0.5 mg/kg. The siTBK1 was transfected in MHCC97-H cells and TBK1 into MHCC97-L, after which the cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice. The nude mice were then given sorafenib by oral gavage at doses of 2 mg/kg, 1 mg/kg, 0.5 mg/kg, and 0.2 mg/kg for almost 21 days (once per 2 days). The tumor weights and tumor volumes were examined.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using the SPSS 9.0 statistical software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States; two-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni correction). The IC50 values of molecular-targeted drugs were calculated by using Origin software (Origin 6.1; OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, United States).

Results

TANK-binding kinase 1 Expression is Associated With the Resistance of Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma

First, the expression of TBK1 in clinical specimens was examined. As shown in Figure 1A, the expression levels of TBK1 were much higher in HCC specimens compared with paired non-tumor tissues. Moreover, the HCC patients were divided into two groups: the TBK1-high group or the TBK1-low group, according to the median value of the TBK1 expression levels in the HCC specimens (Figure 1B). The prognosis of patients received sorafneib treatment in the TBK1-high group treated with the molecular-targeted drug sorafenib was significantly worse than that of the patients in the TBK1-low group. The OS (overall survivial) of the patients in the TBK1-high group and the TTP (time to progress) of sorafenib treatment were significantly shorter than those in the TBK1-low group (Figures 1C,D and Table 3).

FIGURE 1.

The clinical significance of TBK1 in HCC. (A) The expression of TBK1 in HCC clinical specimens or paired non-tumor tissues (non-tumor regions of the liver in the HCC patients). (B) The median value of TBK1 in patients in the TBK1-high group or the TBK1-low group. (C, D) The OS (overall survival) or TTP (time to progress) of the patients in the TBK1-high group or the TBK1-low group who received sorafenib treatment. ∗p < 0.05.

TABLE 3.

The endogenous TBK1 level associated with the clinical outcome of patients received sorafenib treatment.

| TBK1 mRNA expression | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High (n = 26) | Low (n = 26) | ||

| TTP | 8 | 12 | 0.01 |

| 6.0–9.9 (M) | 9.8–13.4 (M) | ||

| OS | 10 | 15 | 0.031 |

| 6.6–13.4 (M) | 7.7–22.2 (M) | ||

TTP, time to progress; OS, overall survival.

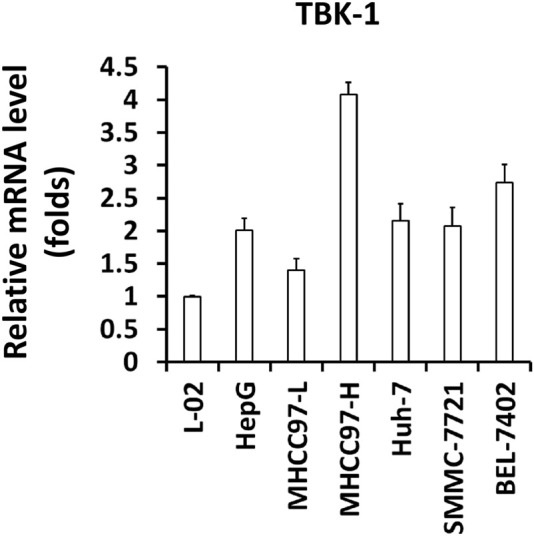

Next, the expression of TBK1 in hepatic cell lines was examined. As shown in Figure 2, the expression level of TBK1 was much higher in HCC cells compared with the non-tumor hepatic cell line L-02. Among the selected HCC cells, the expression level of TBK1 in MHCC97-H cells was the highest, while the expression level of TBK1 in MHCC97-L cells was the lowest, and the expression level of TBK1 in HepG2 was moderate. Because of these results, expression of TBK1 was knocked down using siRNA in MHCC97-H cells or TBK1 was overexpressed in MHCC97-L cells. TBK1 was simultaneously overexpressed and knocked down in HepG2 cells.

FIGURE 2.

The expression level of TBK1 in hepatic cell lines. The expression level of TBK1 in hepatic cell lines was examined by qPCR. The results were shown as Histogram form mean ± SD.

After knockdown or overexpression of TBK1 in HCC cells, the cells were treated with a series of doses of molecularly-targeted drugs to determine the effect of TBK1 in HCC cell death after treatment with molecularly-targeted drugs. The results shown in Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 demonstrate that molecularly-targeted drugs can kill HCC cells in a dose-dependent manner. Overexpression of TBK1 in MHCC97-L and HepG2 cells can significantly downregulate the killing effect of these drugs on HCC cells, and the IC50 values of the drugs on the cells were significantly increased (Table 4 and Table 5). Knockdown of TBK1 with its siRNA enhanced the antitumor activation of molecular-targeted drugs on HCC cells, and the drugs’ IC50 values decreased (Tables 5 and Table 6). Therefore, TBK1 is associated with the resistance of HCC cells to molecular-targeted drugs and TBK1 could be considered as a promising target for HCC treatment.

TABLE 4.

The effect of TBK1 overexpression on the sensitivity of MHCC97-L cells to molecular-target drugs, Sorafenib, Cabozentinib, Lenvatinib, Regorafenib or Anlotinib.

| Drugs | Control | TBK1 |

|---|---|---|

| IC 50 Values (μmol/L) | ||

| Sorafenib | 1.67 ± 0.27 | 8.82 ± 0.25 |

| Cabozentinib | 1.43 ± 0.32 | 12.89 ± 0.30 |

| Lenvatinib | 1.88 ± 0.69 | 9.29 ± 0.44 |

| Regorafenib | 2.13 ± 0.92 | 7.42 ± 1.08 |

| Anlotinib | 1.71 ± 0.36 | 6.13 ± 0.34 |

TABLE 5.

The effect of TBK1 overexpression or knockdown on the sensitivity of HepG2 cells to molecular-target drugs, Sorafenib, Cabozentinib, Lenvatinib, Regorafenib or Anlotinib.

| Drugs | Control | TBK1 | siTBK1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC 50 Values (μmol/L) | |||

| Sorafenib | 1.60 ± 0.20 | 5.22 ± 0.26 | 0.20 ± 0.05 |

| Cabozentinib | 1.43 ± 0.25 | 6.55 ± 0.52 | 0.27 ± 0.10 |

| Lenvatinib | 1.08 ± 0.12 | 4.82 ± 0.26 | 0.17 ± 0.06 |

| Regorafenib | 1.67 ± 0.13 | 5.23 ± 0.87 | 0.70 ± 0.01 |

| Anlotinib | 1.15 ± 0.69 | 3.62 ± 0.16 | 0.24 ± 0.15 |

TABLE 6.

The effect of TBK1 knockdown on the sensitivity of MHCC97-H cells to molecular-target drugs, Sorafenib, Cabozentinib, Lenvatinib, Regorafenib or Anlotinib.

| Drugs | Control | siTBK1 |

|---|---|---|

| IC 50 Values (μmol/L) | ||

| Sorafenib | 0.94 ± 0.51 | 0.07 ± 0.00 |

| Cabozentinib | 1.24 ± 0.60 | 0.23 ± 0.06 |

| Lenvatinib | 0.75 ± 0.25 | 0.14 ± 0.04 |

| Regorafenib | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 0.17 ± 0.02 |

| Anlotinib | 0.56 ± 0.18 | 0.22 ± 0.05 |

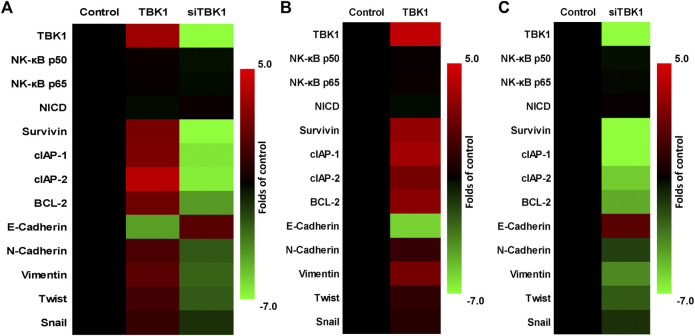

Knockdown of TANK-binding kinase 1 Repressed Drug-Resistance Related Factors

The effect of TBK1 expression on drug-resistance related factors was examined by qPCR. As shown in Figure 3A, overexpression of TBK1 in HepG2 cells upregulated drug resistance-related factors while knockdown of TBK1 downregulated drug resistance related factors. Specifically, cellular pro-survival-/anti-apoptosis-related factors and epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related factors were affected (the expression level of E-Cadherin was upregulated or the expression level of the factors was downregulated). On this basis, TBK1 was knocked down in MHCC97-H cells, and TBK1 was overexpressed in MHCC97-L cells (Figures 3B,C). The trend of the results was basically the same as that in HepG2 (Figures 3A-C). TBK1 did not affect the expression of NF-κB’s p65 or p50, or Notch NICD (FFigures 3A-C).

FIGURE 3.

The effect of TBK1 on the drug-resistance-related factors in HCC cells. (A) HepG2 cells were transfected with TBK1 or siTBK1 and the expression level of drug-resistance-related factors were examined by qPCR. (B) MHCC97-L cells were transfected with TBK1 and the expression level of drug-resistance-related factors were examined by qPCR. (C) MHCC97-H cells were transfected with siTBK1 and the expression level of drug-resistance-related factors were examined by qPCR. The results are shown as heat-map.

Next, to further confirm the effect of TBK1, the relationship between the expressions of TBK1 with these factors in clinical specimens was examined (Figure 4). As shown in Figure 4, the expression level of TBK1 was positively associated with the expression levels of Survivin (Figure 4A), BCL-2 (Figure 4B), cIAP-1 (Figure 4C), and cIAP-2 (Figure 4D) (factors that mediate the anti-apoptosis or pro-survival of cells); negatively associated with the expression of E-cadherin (Figure 4E) (a typical indicator of epithelial phenotype), and did not relate to the expression of NF-κB’s p65 (Figure 4F) or p50 (Figure 4G), or Notch NICD (Figure 4H). Therefore, knockdown of TBK1 repressed drug-resistance related factors’ expression level.

FIGURE 4.

The relationship between TBK1 with the drug-resistance-related factors in HCC specimens. The expression level of TBK1 and drug-resistance-related factors in HCC specimens by qPCR. The expression level of TBK1 is on the abscissa, the expression level of each factor is on the ordinate, and the data are shown as a scatter plot. Additionally, a regression equation was fit to the data (with its p-value) according to the trend of the scatter plot.

Knockdown of TANK-binding kinase 1 Enhanced the in Vivo Sensitivity of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to the Molecular-Targeted Drug Sorafenib

The above results were based on in vitro, cellular experiments. To further confirm the effect of TBK1 on HCC cells, in vivo experiments were performed using the nude mouse model. As shown in Figures 5, 6, HCC cells (MHCC97-L and MHCC97-H) could form subcutaneous tumor tissues in nude mice. Oral administration of sorafenib inhibited the subcutaneous growth of HCC cells in a dose-dependent manner. As shown in Figure 5, overexpression of TBK1 induced the resistance of HCC cells to sorafenib; the antitumor effect of sorafenib significantly decreased (the IC 50 value of the indicated concentrations of sorafenib increased from 1.25 ± 0.75 mg/kg to >2 mg/kg for tumor volumes and from 1.03 ± 0.42 mg/kg to >2 mg/kg for tumor weights). Next, the results shown in Figure 6 indicate that knockdown of TBK1 via its siRNA in MHCC97-H cells enhanced the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib; the antitumor effect of sorafenib significantly increased (the IC 50 value of the indicated concentrations of sorafenib reduced from 1.48 ± 0.91 mg/kg to 0.32 ± 0.25 mg/kg and from 1.67 ± 0.33 mg/kg to 0.41 ± 0.10 mg/kg for tumor weights), respectively. Therefore, knockdown of TBK1 enhanced the in vivo sensitivity of HCC cells to the molecular-targeted drug sorafenib.

FIGURE 5.

TBK1 induces resistance of MHCC97-L cells to the molecularly-targeted drug, sorafenib. After transfection of TBK1 in MHCC97-L cells, the cells were inoculated into nude mice, and the nude mice were treated with sorafenib by oral gavage. Afterward, tumor tissues were collected to determine their volume and weight. Results are displayed as photos of tumor tissue, tumor volume, and tumor weight. *p < 0.05.

FIGURE 6.

siTBK1 enhances the sensitivity of MHCC97-H cells to the molecularly-targeted drug, sorafenib After transfection of siTBK1 in MHCC97-H cells, the cells were inoculated into nude mice, and the nude mice were treated with sorafenib by oral gavage. Afterward, tumor tissues were collected to determine their volume and weight. Results are displayed as photos of tumor tissue, tumor volume, and tumor weight. ∗p < 0.05.

Knockdown of TANK-binding kinase 1 Enhanced the Sensitivity of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to Cytotoxic Chemotherapeutics

The above results were all based on molecularly targeted drugs, and we further tested cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs to supplement them. The results are shown in Table 7. The cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs etoposide, adriamycin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine can inhibit the survival of MHCC97-H cells in a dose–dependent manner and overexpression of TBK1 in cells can induce cell resistance to these drugs (the IC 50 values these cytotoxic chemotherapies significantly up-regulated), and knockdown of TBK1 could significantly up-regulate the killing effects of these drugs on HepG2 cells (the IC 50 values of these cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs were significantly down-regulated) (Table 7). These results further confirmed the role of TBK1 in HCC cells.

TABLE 7.

The effect of TBK1 overexpression or knockdown in HepG2 cells to Cytotoxic chemotherapies.

| Drugs | Control | TBK1 | siTBK1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC 50 Values (μmol/L) | |||

| paclitaxel | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.24 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| etoposide | 0.62 ± 0.10 | 1.18 ± 0.93 | 0.25 ± 0.07 |

| adriamycin | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 1.42 ± 0.25 | 0.10 ± 0.09 |

| gemcitabine | 0.50 ± 0.29 | 1.38 ± 0.26 | 0.14 ± 0.05 |

Small Molecular Inhibitor of TANK-binding kinase 1 Enhanced the Sensitivity of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to Antitumor Drugs

The above results are mainly based on the use of siRNA to knock down the expression of TBK1, and further use the existing TBK1 small molecule inhibitor MRT67307 to treat HCC cells. As shown in Figure 7, MRT67307 can dose-dependently down-regulate the expression levels of NF-κB and Notch pathway-related drug resistance factors in MHCC97-H cells, and inhibited the survival of MHCC97-H cells in a dose-dependent manner. At the same time, the 1 μmol/L dose of MRT67307 itself does not have obvious cytotoxicity, but can significantly down-regulate the expression levels of NF-κB and Notch pathway-related drug resistance factors (Figure 7). Treatment of MRT67307 did not affect the expression of NF-κB’s p65 or p50, or Notch NICD (Figure 7). Therefore, the 1 μmol/L dose of MRT67307 was selected for the next experiment. As shown in Table 8, treatment of 1 μmol/L dose of MRT67307 significantly up-regulate the antitumor effects of these drugs (including the molecular-targeted drugs and cytotoxic chemotherapies) on MHCC-97 cells (the IC 50 values of these cytotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs were significantly down-regulated) (Table 8). Therefore, down-regulation of TBK1 enhanced the sensitivity of HCC cells to antitumor drugs.

FIGURE 7.

The effect of TBK1’s inhibitor MRT67307 on the drug-resistance-related factors in HCC cells. MHCC97-H cells were treated with the indicated concentration of MRT67307 and the expression level of drug-resistance-related factors were examined by qPCR. The inhibitory activation of MRT67307 on MHCC97-H cells was examined by MTT methods. The results are shown as heat-map.

TABLE 8.

The effect of MRT67307 (1 μmol/L) on the antitumor effect of antitumor drugs in MHCC97-H cells.

| Drugs | Control | MRT67307 (1 μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| IC 50 Values (μmol/L) | ||

| Sorafenib | 1.06 ± 0.17 | 0.33 ± 0.10 |

| Cabozentinib | 1.20 ± 0.39 | 0.20 ± 0.03 |

| Lenvatinib | 0.72 ± 0.21 | 0.18 ± 0.06 |

| Regorafenib | 0.95 ± 0.82 | 0.30 ± 0.08 |

| Anlotinib | 0.77 ± 0.43 | 0.14 ± 0.09 |

| paclitaxel | 0.26 ± 0.11 | 0.03 ± 0.00 |

| etoposide | 0.49 ± 0.12 | 0.10 ± 0.08 |

| adriamycin | 0.56 ± 0.18 | 0.15 ± 0.04 |

| gemcitabine | 0.33 ± 0.07 | 0.12 ± 0.07 |

Discussion

At present, molecularly-targeted drug therapy for HCC is a high-interest research topic (Cerrito et al., 2021; El-Khoueiry et al., 2021; Granito et al., 2021; Vogel et al., 2021). It is generally believed that the resistance of HCC to molecularly-targeted drugs is a complex, multistep, and multifactorial process (Busche et al., 2021; Mou et al., 2021). It has been confirmed that the following factors can be involved in inducing the resistance of HCC cells to molecularly-targeted drugs: 1) mutual compensatory effect between RTKs (receptor tyrosine protein kinases), MAPK, PI3K/AKT, HGF/cMET, and other related pathways (Gao et al., 2012; Fu et al., 2020); 2) mechanisms related to cell survival and anti-apoptosis (Yang X et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2021); 3) epithelial-mesenchymal transition (Chen et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2021); and 4) many factors and mechanisms such as cancer stem cells (Ko et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2020; Leung et al., 2021). Each of these mechanism-related signaling pathways and important regulators can be used as intervention targets for HCC treatment, especially molecular-targeted-drug sensitization. There are differences in and connections between these molecular mechanisms, and knowing how to avoid inhibition of a single pathway or target and the compensatory effects of other pathways is of great importance.

TBK1 is an ideal intervention target for the sensitization of HCC to molecular-targeted drugs, mainly based on the following facts. 1) NF-κB can induce HCC by inducing the expression of survivin, cIAPs, BCL-2, and other cell pro-survival and anti-apoptotic factors; cells are resistant to molecularly-targeted drugs (Kang et al., 2013). 2) NF-κB is also regulated by Notch and other drug resistance-related pathways (Xiu et al., 2020). The Notch pathway can induce the expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related factors in cells and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype through NF-κB (Kang et al., 2013; Xiu et al., 2020). 3) As a key regulator of NF-κB activation, activated TBK1 not only induces the activation of the NF-κB pathway but also induces the phosphorylation of AKT, resulting in anti-apoptotic signals and pro-cellular survival. In this study, we not only detected the effect of TBK1 on HCC cells in molecular experiments, cellular experiments, and animal experiments but we also detected the expression of TBK1 in clinical HCC tissue samples, confirming that TBK1 has clinical significance (Ou et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2021). Theoretically, TBK1 may induce the resistance of HCC cells to molecularly-targeted drugs, and our results show that patients with a high TBK1 expression in HCC tissues have a poor prognosis after receiving sorafenib treatment. Therefore, our results are the first to report and confirm the role of TBK1 in molecularly-targeted drug resistance in HCC.

In this study, we overexpressed and knocked down TBK1 in HCC cells, then detected the expression levels of various factors, including: 1) survivin and cIAP related to cell survival and apoptosis -1/2, or BCL-2; 2) epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related factors, such as vimentin and N-cadherin (markers of mesenchymal transition), and E-cadherin (marker of an epithelial phenotype); 3) P65 and P50 of NF-κB; and 4) NICD of Notch protein (Zhang Y et al., 2017). These factors are all drug resistance-related genes within the NF-κB pathway and several other pathways are also involved. The results showed that TBK1 could affect the pro-survival, anti-apoptotic, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related factors, but not P65, P50, or NICD. These results are also consistent with the mechanism of action of TBK1 itself. In this study, five HCC-related, molecularly-targeted drugs were selected, but the Notch/NF-κB pathway can activate/desensitize HCC cells to molecularly-targeted drugs through cell-promoting, anti-apoptotic-related, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related factors, and eventually induce cell resistance to molecularly-targeted drugs. This suggests that the role of Notch/NF-κB pathway is not specific to drug selection, and downregulating TBK1 expression is also a broad-spectrum, molecular-targeted-drug sensitization strategy in HCC. The combined effect of different drugs is of great importance. Using a variety of strategies, our research group discovered some small molecule compounds with molecularly-targeted-drug sensitization effects. Existing studies have shown that TBK1 small molecule inhibitors have certain anti-tumor activity. In the future, research on TBK1 small molecule inhibitors and the combination of TBK1 small molecule inhibitors with molecular-targeted drugs and other therapeutic strategies will be carried out. There are few reports on the role and molecular mechanism of TBK1 in HCC (only 2-3 papers in PubMed) and unclear (Kim et al., 2010; Zou et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2021b). These articles focus on HCC-related tumor immunity and HBV-related research (Kim et al., 2010; Zou et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2021b). This study is the first to report the relationship between TBK1 and the resistance of HCC cells to molecularly targeted drugs, which not only expands our understanding of TBK1, but also provides new ideas and implications for the treatment of HCC with molecularly targeted drugs.

In addition to the Notch/NF-κB pathway, there are other important signaling pathways in HCC cells for resistance to antitumor drugs (Zhu et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2020; He Y et al., 2021; He W et al., 2021; Guan et al., 2021; Yan et al., 2021). For example, our research group found that molecular-targeted drugs can act as ligands and agonists of the pregnane X receptor to induce the transcription factor activity and downstream drug resistance genes of PXR (Feng et al., 2018; Shao et al., 2018). These drug-resistance genes can act as enzymes of drug metabolism to accelerate clearance rate of molecularly-targeted drugs and finally induce the resistance of HCC cells to molecularly-targeted drugs. The effects of PXR and its downstream drug-resistance genes on Notch/NF-κB are similar to those of antitumor drugs, and they are all non-selective. Moreover, this study mainly focused on the role of TBK1 in HCC. In addition to HCC, TBK1 may also regulate the resistance of other malignant tumor cells to antitumor drugs (Vu and Aplin, 2014; Zhu et al., 2019; Cheng and Cashman, 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). In the future, we will further explore the impact of TBK1 and its inhibitors on other kinds of human malignancies.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Medical Ethics Committee of the Fifth Medical Center of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. The animal study was reviewed and approved by Animal Ethics Committee of the Fifth Medical Center of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital.

Author Contributions

FD, QJ, JH, and DH conceived the main ideas and wrote the paper. HS, FS, SY, and HT supervised the study. FD, HS, and XL developed major methodologies, databases, reagents, and primary experiments. YC analyzed different aspects of the results. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.: 81700540) from the Chinese Government.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Alam M., Hasan G. M., Hassan M. I. (2021). A Review on the Role of TANK-Binding Kinase 1 Signaling in Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 183, 2364–2375. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruix J., Qin S., Merle P., Granito A., Huang Y. H., Bodoky G., et al. (2017). Regorafenib for Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Who Progressed on Sorafenib Treatment (RESORCE): a Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 389 (10064), 56–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busche S., John K., Wandrer F., Vondran F. W. R., Lehmann U., Wedemeyer H., et al. (2021). BH3-only Protein Expression Determines Hepatocellular Carcinoma Response to Sorafenib-Based Treatment. Cell Death Dis. 12 (8), 736. 10.1038/s41419-021-04020-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerrito L., Santopaolo F., Monti F., Pompili M., Gasbarrini A., Ponziani F. R. (2021). Advances in Pharmacotherapeutics for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 22 (10), 1343–1354. 10.1080/14656566.2021.1892074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. W., Zhou Y., Wei T., Wen L., Zhang Y. B., Shen S. C., et al. (2021). lncRNA-POIR Promotes Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Suppresses Sorafenib Sensitivity Simultaneously in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Sponging miR-182-5p. J. Cell Biochem. 122 (1), 130–142. 10.1002/jcb.29844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Cashman J. R. (2020). PAWI-2 Overcomes Tumor Stemness and Drug Resistance via Cell Cycle Arrest in Integrin β3-KRAS-dependent Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 9162. 10.1038/s41598-020-65804-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J., Li H., Liu Y., Xie Y., Yu J., Sun H., et al. (2021). OXCT1 Enhances Gemcitabine Resistance through NF-Κb Pathway in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 11, 698302. 10.3389/fonc.2021.698302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donisi C., Puzzoni M., Ziranu P., Lai E., Mariani S., Saba G., et al. (2020). Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in the Treatment of HCC. Front. Oncol. 10, 601240. 10.3389/fonc.2020.601240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y., Shi X., Ma W., Wen P., Yu P., Wang X., et al. (2021). Phthalates Promote the Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells by Enhancing the Interaction between Pregnane X Receptor and E26 Transformation Specific Sequence 1. Pharmacol. Res. 169, 105648. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khoueiry A. B., Hanna D. L., Llovet J., Kelley R. K. (2021). Cabozantinib: An Evolving Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Treat. Rev. 98, 102221. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2021.102221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng F., Jiang Q., Cao S., Cao Y., Li R., Shen L., et al. (2018). Pregnane X Receptor Mediates Sorafenib Resistance in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1862 (4), 1017–1030. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng F., Li X., Li R., Li B. (2019). The Multiple-Kinase Inhibitor Lenvatinib Inhibits the Proliferation of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Anim. Model Exp. Med. 2 (3), 178–184. 10.1002/ame2.12076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu R., Jiang S., Li J., Chen H., Zhang X. (2020). Activation of the HGF/c-MET axis Promotes Lenvatinib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells with High C-MET Expression. Med. Oncol. 37 (4), 24. 10.1007/s12032-020-01350-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F. F., Quan J. H., Choi I. W., Lee Y. J., Jang S. G., Yuk J. M., et al. (2021). FAF1 Downregulation by Toxoplasma Gondii Enables Host IRF3 Mobilization and Promotes Parasite Growth. J. Cell Mol. Med. 25 (19), 9460–9472. 10.1111/jcmm.16889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Inagaki Y., Song P., Qu X., Kokudo N., Tang W. (2012). Targeting C-Met as a Promising Strategy for the Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Pharmacol. Res. 65 (1), 23–30. 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granito A., Marinelli S., Forgione A., Renzulli M., Benevento F., Piscaglia F., et al. (2021). Regorafenib Combined with Other Systemic Therapies: Exploring Promising Therapeutic Combinations in HCC. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 8, 477–492. 10.2147/JHC.S251729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan X., Wu Y., Zhang S., Liu Z., Fan Q., Fang S., et al. (2021). Activation of FcRn Mediates a Primary Resistance Response to Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 709343. 10.3389/fphar.2021.709343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W., Huang X., Berges B. K., Wang Y., An N., Su R., et al. (2021). Artesunate Regulates Neurite Outgrowth Inhibitor Protein B Receptor to Overcome Resistance to Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 615889. 10.3389/fphar.2021.615889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Sun H., Jiang Q., Chai Y., Li X., Wang Z., et al. (2021). Hsa-miR-4277 Decelerates the Metabolism or Clearance of Sorafenib in HCC Cells and Enhances the Sensitivity of HCC Cells to Sorafenib by Targeting Cyp3a4. Front. Oncol. 11, 735447. 10.3389/fonc.2021.735447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Luo Y., Huang L., Zhang D., Wang X., Ji J., et al. (2021). New Frontiers against Sorafenib Resistance in Renal Cell Carcinoma: From Molecular Mechanisms to Predictive Biomarkers. Pharmacol. Res. 170, 105732. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich B., Gertz E. M., Schäffer A. A., Craig A., Ruf B., Subramanyam V., et al. (2021). The Tumour Microenvironment Shapes Innate Lymphoid Cells in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gut. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herhaus L. (2021). TBK1 (TANK-Binding Kinase 1)-mediated Regulation of Autophagy in Health and Disease. Matrix Biol. 100-101, 84–98. 10.1016/j.matbio.2021.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D. Q., El-Serag H. B., Loomba R. (2021). Global Epidemiology of NAFLD-Related HCC: Trends, Predictions, Risk Factors and Prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18 (4), 223–238. 10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Liu M., Wang X., Jiang Q., Wang S., Santhanam R. K., et al. (2021). Cimigenoside Functions as a Novel γ-secretase Inhibitor and Inhibits the Proliferation or Metastasis of Human Breast Cancer Cells by γ-secretase/Notch axis. Pharmacol. Res. 169, 105686. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H., Yang Q., Wang T., Cao Y., Jiang Q. Y., Ma H. D., et al. (2016). Rhamnetin Induces Sensitization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to a Small Molecular Kinase Inhibitor or Chemotherapeutic Agents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860 (7), 1417–1430. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q., Ma Y., Han J., Chu J., Ma X., Shen L., et al. (2021). MDM2 Binding Protein Induces the Resistance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to Molecular Targeting Agents via Enhancing the Transcription Factor Activity of the Pregnane X Receptor. Front. Oncol. 11, 715193. 10.3389/fonc.2021.715193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Chen S., Li Q., Liang J., Lin W., Li J., et al. (2021b). TANK-binding Kinase 1 (TBK1) Serves as a Potential Target for Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Enhancing Tumor Immune Infiltration. Front. Immunol. 12, 612139. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.612139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y., Han Q., Zhao H., Zhang J. (2021). The Mechanisms of HBV-Induced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Hepatocell. Carcinoma 8, 435–450. 10.2147/JHC.S307962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie Y., Liu G., E M., Xu G., Guo J., Li Y., et al. (2021). Novel Small Molecule Inhibitors of the Transcription Factor ETS-1 and Their Antitumor Activity against Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 906, 174214. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J., Kim E., Kim W., Seong K. M., Youn H., Kim J. W., et al. (2013). Rhamnetin and Cirsiliol Induce Radiosensitization and Inhibition of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) by miR-34a-Mediated Suppression of Notch-1 Expression in Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Cell Lines. J. Biol. Chem. 288 (38), 27343–27357. 10.1074/jbc.M113.490482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. W., Talati C., Kim R. (2017). Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): beyond Sorafenib-Chemotherapy. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 8 (2), 256–265. 10.21037/jgo.2016.09.07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. R., Lee S. H., Jung G. (2010). The Hepatitis B Viral X Protein Activates NF-kappaB Signaling Pathway through the Up-Regulation of TBK1. FEBS Lett. 584 (3), 525–530. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko K. L., Mak L. Y., Cheung K. S., Yuen M. S. (2020). Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Recent Advances and Emerging Medical Therapies. F1000Res. 2020 Jun 17;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-620. 10.12688/f1000research.24543.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo M., Finn R. S., Qin S., Han K. H., Ikeda K., Piscaglia F., et al. (2018). Lenvatinib versus Sorafenib in First-Line Treatment of Patients with Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma: a Randomised Phase 3 Non-inferiority Trial. Lancet 391 (10126), 1163–1173. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Nandi A., Singh S., Regulapati R., Li N., Tobias J. W., et al. (2021). Dll1+ Quiescent Tumor Stem Cells Drive Chemoresistance in Breast Cancer through NF-Κb Survival Pathway. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 432. 10.1038/s41467-020-20664-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung H. W., Leung C. O. N., Lau E. Y., Chung K. P. S., Mok E. H., Lei M. M. L., et al. (2021). EPHB2 Activates β-Catenin to Enhance Cancer Stem Cell Properties and Drive Sorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 81 (12), 3229–3240. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-0184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Feng F., Jia H., Jiang Q., Cao S., Wei L., et al. (2021). Rhamnetin Decelerates the Elimination and Enhances the Antitumor Effect of the Molecular-Targeting Agent Sorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells via the miR-148a/PXR axis. Food Funct. 12 (6), 2404–2417. 10.1039/d0fo02270e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. U., Zhao Y., Zhang H. (2017). P16INK4a Upregulation Mediated by TBK1 Induces Retinal Ganglion Cell Senescence in Ischemic Injury. Cell Death Dis. 8 (4), e2752. 10.1038/cddis.2017.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A. J., Baranski T., Chaterjee D., Chapman W., Foltz G., Kim H. (2020). Androgen-receptor-positive Hepatocellular Carcinoma in a Transgender Teenager Taking Exogenous Testosterone. Lancet 396 (10245), 198. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31538-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet J. M., Montal R., Sia D., Finn R. S. (2018). Molecular Therapies and Precision Medicine for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15 (10), 599–616. 10.1038/s41571-018-0073-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Yao Y., Wang C., Zhang L., Cheng L., Wang Y., et al. (2016). Transcription Factor Activity of Estrogen Receptor α Activation upon Nonylphenol or Bisphenol A Treatment Enhances the In Vitro Proliferation, Invasion, and Migration of Neuroblastoma Cells. Onco Targets Ther. 9, 3451–3463. 10.2147/OTT.S105745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Chai N., Jiang Q., Chang Z., Chai Y., Li X., et al. (2020). DNA Methyltransferase Mediates the Hypermethylation of the microRNA 34a Promoter and Enhances the Resistance of Patient-Derived Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Molecular Targeting Agents. Pharmacol. Res. 160, 105071. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou L., Tian X., Zhou B., Zhan Y., Chen J., Lu Y., et al. (2021). Improving Outcomes of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: New Data and Ongoing Trials. Front. Oncol. 11, 752725. 10.3389/fonc.2021.752725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nhlane R., Kreuels B., Mallewa J., Chetcuti K., Gordon M. A., Stockdale A. J. (2021). Late Presentation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Highlights the Need for a Public Health Programme to Eliminate Hepatitis B. Lancet 398 (10318), 2288. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02138-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Y. H., Torres M., Ram R., Formstecher E., Roland C., Cheng T., et al. (2011). TBK1 Directly Engages Akt/PKB Survival Signaling to Support Oncogenic Transformation. Mol. Cell 41 (4), 458–470. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaris Observatory Collaborators (2018). Global Prevalence, Treatment, and Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in 2016: a Modelling Study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 3 (6), 383–403. 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30056-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators (2022). Global Change in Hepatitis C Virus Prevalence and Cascade of Care between 2015 and 2020: a Modelling Study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7 (5), 396–415. 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00472-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell E. E., Wong V. W., Rinella M. (2021). Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Lancet 397 (10290), 2212–2224. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32511-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revach O. Y., Liu S., Jenkins R. W. (2020). Targeting TANK-Binding Kinase 1 (TBK1) in Cancer. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 24 (11), 1065–1078. 10.1080/14728222.2020.1826929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R., Jr. (2019). Properties of FDA-Approved Small Molecule Protein Kinase Inhibitors. Pharmacol. Res. 144, 19–50. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R., Jr. (2020). Properties of FDA-Approved Small Molecule Protein Kinase Inhibitors: A 2020 Update. Pharmacol. Res. 152, 104609. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R., Jr. (2021). Properties of FDA-Approved Small Molecule Protein Kinase Inhibitors: A 2021 Update. Pharmacol. Res. 165, 105463. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roskoski R., Jr. (2022). Properties of FDA-Approved Small Molecule Protein Kinase Inhibitors: A 2022 Update. Pharmacol. Res. 175, 106037. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.106037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z., Li Y., Dai W., Jia H., Zhang Y., Jiang Q., et al. (2018). ETS-1 Induces Sorafenib-Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells via Regulating Transcription Factor Activity of PXR. Pharmacol. Res. 135, 188–200. 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L. J., Sun H. W., Chai Y. Y., Jiang Q. Y., Zhang J., Li W. M., et al. (2021). The Disassociation of the A20/HSP90 Complex via Downregulation of HSP90 Restores the Effect of A20 Enhancing the Sensitivity of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to Molecular Targeted Agents. Front. Oncol. 11, 804412. 10.3389/fonc.2021.804412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. I. E., Burger J. A. (2021). Resistance Mutations to BTK Inhibitors Originate from the NF-Κb but Not from the PI3K-RAS-MAPK Arm of the B Cell Receptor Signaling Pathway. Front. Immunol. 12, 689472. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.689472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H., Feng F., Xie H., Li X., Jiang Q., Chai Y., et al. (2019). Quantitative Examination of the Inhibitory Activation of Molecular Targeting Agents in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patient-Derived Cell Invasion via a Novel In Vivo Tumor Model. Anim. Model Exp. Med. 2 (4), 259–268. 10.1002/ame2.12085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R. L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., et al. (2021). Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft J., Markson M., Legarda D., Patel R., Chan M., Malle L., et al. (2021). Human TBK1 Deficiency Leads to Autoinflammation Driven by TNF-Induced Cell Death. Cell 184 (17), 4447. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan A. T., Schreiber S. (2020). Adoptive T-Cell Therapy for HBV-Associated HCC and HBV Infection. Antivir. Res. 176, 104748. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Chen Z., Zhang W., Cheng Y., Zhang B., Wu F., et al. (2020). The Mechanisms of Sorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Theoretical Basis and Therapeutic Aspects. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 5 (1), 87. 10.1038/s41392-020-0187-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel A., Bathon M., Saborowski A. (2021). Advances in Systemic Therapy for the First-Line Treatment of Unresectable HCC. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 21 (6), 621–628. 10.1080/14737140.2021.1882855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu H. L., Aplin A. E. (2014). Targeting TBK1 Inhibits Migration and Resistance to MEK Inhibitors in Mutant NRAS Melanoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 12 (10), 1509–1519. 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. S., Fan J. G., Zhang Z., Gao B., Wang H. Y. (2014). The Global Burden of Liver Disease: the Major Impact of China. Hepatology 60 (6), 2099–2108. 10.1002/hep.27406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. H., Zeng Z., Sun J., Chen Y., Gao X. (2021). A Novel Small-Molecule Antagonist Enhances the Sensitivity of Osteosarcoma to Cabozantinib In Vitro and In Vivo by Targeting DNMT-1 Correlated with Disease Severity in Human Patients. Pharmacol. Res. 173, 105869. Epub 2021 Sep 3. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Wei C. (2020). Advances in the Early Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Genes Dis. 7 (3), 308–319. 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Liu S., Chen Q., Ren Y., Li Z., Cao S. (2021). Novel Small Molecular Inhibitor of Pit-Oct-Unc Transcription Factor 1 Suppresses Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Proliferation. Life Sci. 277, 119521. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia P., Zhang H., Xu K., Jiang X., Gao M., Wang G., et al. (2021). MYC-targeted WDR4 Promotes Proliferation, Metastasis, and Sorafenib Resistance by Inducing CCNB1 Translation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 12 (7), 691. 10.1038/s41419-021-03973-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia S., Pan Y., Liang Y., Xu J., Cai X. (2020). The Microenvironmental and Metabolic Aspects of Sorafenib Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. EBioMedicine 51, 102610. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.102610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu Y., Dong Q., Fu L., Bossler A., Tang X., Boyce B., et al. (2020). Coactivation of NF-Κb and Notch Signaling Is Sufficient to Induce B-Cell Transformation and Enables B-Myeloid Conversion. Blood 135 (2), 108–120. 10.1182/blood.2019001438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Kalac M., Markson M., Chan M., Brody J. D., Bhagat G., et al. (2020). Reversal of CYLD Phosphorylation as a Novel Therapeutic Approach for Adult T-Cell Leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL). Cell Death Dis. 11 (2), 94. 10.1038/s41419-020-2294-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X., Tian R., Sun J., Zhao Y., Liu B., Su J., et al. (2021). Sorafenib-Induced Autophagy Promotes Glycolysis by Upregulating the p62/HDAC6/HSP90 Axis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 788667. 10.3389/fphar.2021.788667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Zhang M. Z., Sun H. W., Chai Y. T., Li X., Jiang Q., et al. (2021). A Novel Microcrystalline BAY-876 Formulation Achieves Long-Acting Antitumor Activity against Aerobic Glycolysis and Proliferation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 11, 783194. 10.3389/fonc.2021.783194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Liu J., Liang Q., Sun G. (2021). Valproic Acid Reverses Sorafenib Resistance through Inhibiting Activated Notch/Akt Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 35 (4), 690–699. 10.1111/fcp.12608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. M., Kim S. Y., Seki E. (2019). Inflammation and Liver Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Semin. Liver Dis. 39 (1), 26–42. 10.1055/s-0038-1676806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin F., Feng F., Wang L., Wang X., Li Z., Cao Y. (2019). SREBP-1 Inhibitor Betulin Enhances the Antitumor Effect of Sorafenib on Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Restricting Cellular Glycolytic Activity. Cell Death Dis. 10 (9), 672. 10.1038/s41419-019-1884-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Wang F., Zhang Z. (2017). Current Advances in the Elimination of Hepatitis B in China by 2030. Front. Med. 11 (4), 490–501. 10.1007/s11684-017-0598-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li D., Feng F., An L., Hui F., Dang D., et al. (2017). Progressive and Prognosis Value of Notch Receptors and Ligands in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 14809. 10.1038/s41598-017-14897-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li D., Jiang Q., Cao S., Sun H., Chai Y., et al. (2018). Novel ADAM-17 Inhibitor ZLDI-8 Enhances the In Vitro and In Vivo Chemotherapeutic Effects of Sorafenib on Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Cell Death Dis. 9 (7), 743. 10.1038/s41419-018-0804-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q., Tian W., Jiang Z., Huang T., Ge C., Liu T., et al. (2021). A Positive Feedback Loop of AKR1C3-Mediated Activation of NF-Κb and STAT3 Facilitates Proliferation and Metastasis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 81 (5), 1361–1374. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-2480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Gao Y., Tong Y., Wu Q., Zhou Y., Li Y. (2021). Anlotinib Enhances the Antitumor Activity of Radiofrequency Ablation on Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Pharmacol. Res. 164, 105392. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Qi J., Lim C. W., Kim J. W., Kim B. (2020). Dual TBK1/IKKε Inhibitor Amlexanox Mitigates Palmitic Acid-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Lipoapoptosis In Vitro . Toxicology 444, 152579. 10.1016/j.tox.2020.152579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L., Yang H., Chao Y., Gu Y., Zhang J., Wang F., et al. (2021). Akt Phosphorylation Regulated by IKKε in Response to Low Shear Stress Leads to Endothelial Inflammation via Activating IRF3. Cell Signal 80, 109900. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Tao X., Lu W., Ding Y., Tang Y., Hernandez D., et al. (2019). Blockade of Integrin β3 Signals to Reverse the Stem-like Phenotype and Drug Resistance in melanomaDefining the Landscape of ATP-Competitive Inhibitor Resistance Residues in Protein Kinases. Cancer Chemother. PharmacolNat Struct. Mol. Biol. 8327 (41), 61592–624104. 10.1007/s00280-018-3760-z10.1038/s41594-019-0358-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. J., Zheng B., Wang H. Y., Chen L. (2017). New Knowledge of the Mechanisms of Sorafenib Resistance in Liver Cancer. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 38 (5), 614–622. 10.1038/aps.2017.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou R. C., Liang Y., Li L. L., Tang J. Z., Yang Y. P., Geng Y. C., et al. (2019). Bioinformatics Analysis Identifies Protein Tyrosine Kinase 7 (PTK7) as a Potential Prognostic and Therapeutic Biomarker in Stages I to IV Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. 25, 8618–8627. 10.12659/MSM.917142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou X. Z., Zhou X. H., Feng Y. Q., Hao J. F., Liang B., Jia M. W. (2021). Novel Inhibitor of OCT1 Enhances the Sensitivity of Human Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells to Antitumor Agents. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 907, 174222. Epub 2021 Jun 2. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.