Abstract

Background

Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) and community acquired pneumonia (CAP) often coexist. Although chest radiographs may differentiate between these diagnoses, chest radiography is known to underestimate the incidence of CAP in AECOPD. In this exploratory study, we prospectively investigated the incidence of infiltrative changes using low-dose computed tomography (LDCT). Additionally, we investigated whether clinical biomarkers of CAP differed between patients with and without infiltrative changes.

Methods

Patients with AECOPD in which pneumonia was excluded using chest radiography underwent additional LDCT-thorax. The images were read independently by two radiologists; a third radiologist was consulted as adjudicator. C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT), and serum amyloid A (SAA) at admission were assessed.

Results

Out of the 100 patients included, 24 had one or more radiographic abnormalities suggestive of pneumonia. The interobserver agreement between two readers (Cohen's κ) was 0.562 (95% CI 0.371–0.752; p<0.001). Biomarkers were elevated in the group with radiological abnormalities compared to the group without abnormalities. Median (interquartile range (IQR)) CRP was 76 (21.5–148.0) mg·L−1 compared to 20.5 (8.8–81.5) mg·L −1 (p=0.018); median (IQR) PCT was 0.09 (0.06–0.15) µg·L−1 compared to 0.06 (0.04–0.08) μg·L−1 (p=0.007); median (IQR) SAA was 95 (7–160) µg·mL−1 compared to 16 (3–89) µg·mL−1 (p=0.019). Sensitivity and specificity for all three biomarkers were moderate for detecting radiographic abnormalities by LDCT in this population. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.66 (95% CI 0.52–0.80) for CRP, 0.66 (95% CI 0.53–0.80) for PCT and 0.69 (95% CI 0.57–0.81) for SAA.

Conclusion

LDCT can detect additional radiological abnormalities that may indicate acute-phase lung involvement in patients with AECOPD without infiltrate(s) on the chest radiograph. Despite CRP, PCT and SAA being significantly higher in the group with radiological abnormalities on LDCT, they proved unable to reliably detect or exclude CAP. Further research is warranted.

Short abstract

LDCT-thorax can detect additional radiological abnormalities in patients with AECOPD after excluding CAP using chest radiography. Biomarkers are significantly elevated in patients with abnormalities, but are not able to reliably exclude these changes. https://bit.ly/3KAsBap

Introduction

Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) are associated with short-term and long-term reductions in quality of life and lung function, as well as increased risk of death [1–4]. On average, a patient with COPD suffers from 1.5 exacerbations a year [5]. Moreover, AECOPD requiring hospital admission represents a significant prognostic factor for reduced survival across all stages of COPD severity [6].

Patients with COPD have an increased risk of pneumonia, making it the most frequent infectious complication in COPD [7]. To complicate matters further, AECOPD and pneumonia are symptomatically alike, making it hard to diagnose pneumonia in COPD, based on clinical signs and symptoms alone [8]. Establishing a correct diagnosis is important for the guidance of antibiotic therapy. Misdiagnosing pneumonia could have great implications for patients, whereas overdiagnosing pneumonia leads to unnecessary exposure to antibiotics, which is a major driver of antimicrobial resistance [9, 10]. Hence, clinicians have a keen interest in new biomarkers that together with clinical assessments may improve the diagnostic accuracy of pneumonia in patients with AECOPD. Potential biomarkers that are used in AECOPD to detect bacterial infection are C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcitonin (PCT) and serum amyloid A (SAA) [11, 12]. Using these biomarkers as a diagnostic tool may increase the ability to detect clinically relevant bacterial infections at an early stage of the disease. Yet, it is not known whether these biomarkers can differentiate between AECOPD and community acquired pneumonia (CAP). Therefore, current practice for detecting pneumonia in patients with AECOPD is chest radiography. One study showed that 20% of patients admitted to hospital with AECOPD had abnormalities consistent with pneumonia on chest radiography [13], although this is probably an underestimation of the true incidence of pneumonia in patients with AECOPD; chest radiography has limited sensitivity and specificity. Moreover, the interpretation of chest radiography is often complicated by pre-existing cardiopulmonary diseases [14, 15]. Chest computed tomography (CT) outclasses chest radiography and is now considered the gold standard for diagnosing CAP [16, 17]. However, CT delivers much higher radiation doses than conventional diagnostic radiography [18]. An alternative to conventional chest CT scanning is low-dose CT (LDCT), which produces acceptable image quality with lower radiation exposure. LDCT scans have been shown to detect CAP if the chest radiograph does not reveal findings that explain the patient's clinical presentation [19].

In this exploratory study, we prospectively aimed to investigate in patients with AECOPD admitted to hospital in whom pneumonia was excluded using chest radiography, whether clinical biomarkers of CAP differed between patients with and without radiological abnormalities on LDCT. In addition, we investigated the interobserver variation in LDCT reading.

Material and methods

100 consecutive patients were enrolled at the Northwest Clinics Alkmaar (Alkmaar, the Netherlands) between November 2011 and March 2014 as part of the CRP-guided Antibiotic Treatment of Acute Exacerbations of COPD Admitted to Hospital study (CATCH study) (clinicaltrials.gov NCT01232140) [20]. The local ethics boards approved the study protocol, and all patients provided written informed consent. The study population consisted of patients diagnosed with COPD stages I–IV as defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) [21]. Inclusion criteria dictate that patients had acute exacerbation as defined by GOLD requiring hospital admission according to GOLD guidelines [21]; age >40 years; and former or current smoking, with a minimum smoking history of 10 pack-years. Exclusion criteria were pre-treatment with oral corticosteroids exceeding a total dose of 210 mg prednisolone during the 14 days preceding the presentation with AECOPD for hospitalisation and pneumonia visualised on a chest radiograph. Immunocompromised patients, patients with active lung cancer and patients with pulmonary embolism were also excluded.

Procedures

Before informed consent was obtained, a chest radiograph was performed to rule out CAP. After informed consent was obtained, baseline blood samples were drawn and baseline variables were collected. LDCT was performed within 12 h after informed consent was obtained using a standardised protocol. LDCT was performed on a CT Philips MX 8000 (16-slice) with the following settings: 90 kV, 25 mAs, CTDI 0.8 mGy; and CT Somatom Definition Flash (128 slice Dual source CT) with the following settings: 120 kV, 20 mAs, CTDI 1.35 mGy. For both scanners, acquisition and reconstruction was <1 mm.

Image analysis

The images were independently read by two radiologists (E. Boerhout and F.J. Rietema). If there was a dispute between the radiologists considering the presence of an infiltrate, a third radiologist was consulted as adjudicator (P.A. de Jong). The readers had no knowledge of clinical or laboratory data, other than the age and sex of the patient. From a list of abnormalities (segmental, peribronchovascular or scattered ground-glass, reticular opacity or consolidation), at least one, or a combination of several abnormalities was used for the diagnosis of pneumonia assessed by LDCT scan [22].

Biomarker measurements

Serum CRP was measured by nephelometry on a Beckman Synchron DxC 800 analyser (CRP latex reagent; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA); CRP reference values 0–5 mg·L−1. PCT was measured using time-resolved amplified cryptate emission (TRACE) technology on a Kryptor Compact analyser (Thermofisher – BRAHMS, Heningsdorf, Germany) with PCT-sensitive Kryptor reagent (Thermofisher – BRAHMS); PCT reference values 0.00–0.10 µg·L−1. SAA was measured using an in-house sandwich ELISA. The ELISA test was calibrated against World Health Organization standard 92/680; reference values were established as <4.2 mg·L−1 [23]. The test was performed at the laboratory of medicine of the University Medical Centre Groningen (Groningen, the Netherlands).

Microbiology

For all patients, sputum culture (if possible), nasopharyngeal swab for multiplex PCR for atypical and viral pathogens was obtained at admission. Additionally, paired serum samples were taken within 1 month for serology (Serion ELISA classic; Virion, Würzburg, Germany) for the detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1–7, influenza A and B virus, parainfluenza virus 1–3, respiratory syncytial virus and adenovirus.

Statistical analysis

In this pilot study, our primary objective was to establish whether levels of CRP, PCT and SSA differed between patients with and without infiltrative changes on LDCT. As we were unaware of how many patients would have infiltrative changes on their LDCT, and how this would influence biomarker levels, we were not able to make a sample size calculation. Due to financial constraints, a convenience sample of 100 consecutive patients initially underwent a LDCT scan. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS package programme (version 22.0). Data was presented as median (interquartile range (IQR)). In the comparison between groups, Chi-squared test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used. The interobserver agreement was measured using Cohen's κ: <0.20 indicating poor agreement, 0.21–0.40 fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 good agreement and 0.81–1.00 very good agreement between two observers. Receiver operating characteristics analysis was used to analyse the diagnostic accuracy of biomarkers. Overall statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p-value <0.05.

Results

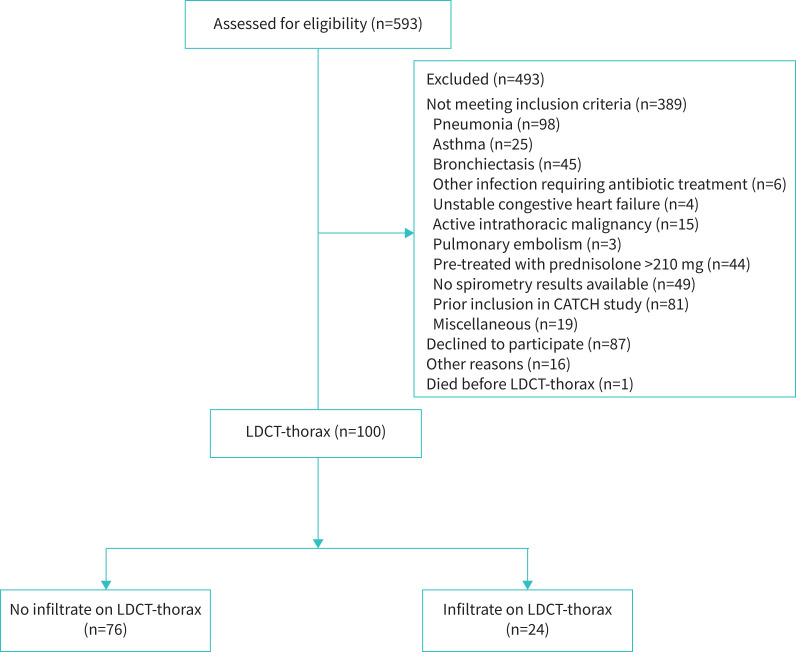

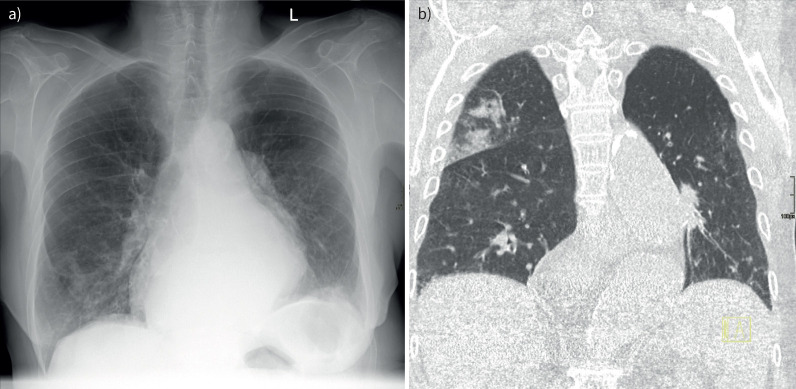

592 patients presenting at our emergency department with AECOPD were screened for inclusion. 100 (16.8%) patients were eligible and gave informed consent (figure 1). 24 (24%) patients had radiological abnormalities compatible with acute-phase lung involvement detected by LDCT without abnormalities visible on chest radiography (figure 2). Baseline characteristics of both groups are summarised in table 1 and did not show any significant differences between the groups, except for oxygen saturation which was slightly lower in the group with radiological abnormalities.

FIGURE 1.

Trial profile. CATCH: CRP-guided Antibiotic Treatment of Acute Exacerbations of COPD Admitted to Hospital; LDCT: low-dose computed tomography.

FIGURE 2.

A 79-year-old female presented to our emergency room with symptoms of acute exacerbation of COPD. a) Conventional chest radiograph without evidence of radiological abnormalities; b) low-dose coronal plane computed tomography of the same patient with alveolar consolidation of the right upper lobe.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

| No radiological abnormalities present | Radiological abnormalities present | p-value | |

| Patients | 76 | 24 | |

| Male | 38 (50) | 12 (50) | 1.000 |

| Age, years | 71 (62–77) | 68 (64–77) | 0.707 |

| FEV1, L # | 1.13 (0.82–1.46) | 1.17 (0.87–1.43) | 0.710 |

| FEV1, % pred # | 45 (35–59) | 42 (34–61) | 0.965 |

| FVC, L # | 2.76 (2.05–3.63) | 2.73 (2.16–3.44) | 0.803 |

| FVC, % pred # | 82 (74–99) | 81 (71–103) | 0.954 |

| FEV1/FVC, % # | 39.3 (31.4–48.9) | 38.5 (30.6–47.0) | 0.834 |

| BMI, kg·m−2 | 24.2 (21.2–27.8) | 23.6 (21.8–27.8) | 0.916 |

| Current smoking | 22 (28.9) | 9 (37.5) | 0.430 |

| Smoking pack-years, n | 43 (24–53) | 30 (21–50) | 0.207 |

| Number of exacerbations in past year, n | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.311 |

| Prior pneumonia | 12 (15.8) | 3 (12.5) | 0.694 |

| History of heart failure | 4 (5.3) | 2 (8.3) | 0.581 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (10.5) | 1 (4.2) | 0.343 |

| Pre-treatment with antibiotics | 31 (40.8) | 10 (41.7) | 0.939 |

| Pre-treatment with systemic corticosteroids | 38 (50.0) | 11 (48.8) | 0.722 |

| ICS usage | 18 (23.7) | 5 (20.8) | 0.722 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths·min−1 | 20 (16–24) | 24 (18–24) | 0.151 |

| Heart rate, beats·min−1 | 89 (78–102) | 95 (79–104) | 0.412 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 148 (131–162) | 137 (120–157) | 0.108 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 86 (71–93) | 78 (67–88) | 0.252 |

| Temperature, °C | 37.2 (36.7–37.7) | 37.5 (36.8–37.8) | 0.440 |

| Oxygen saturation, % | 94 (92–96) | 93 (91–94) | 0.041 |

| CCQ at admittance | 3.8 (3.2–4.1) | 3.8 (3.1–4.3) | 0.360 |

| c-LRTI-VAS at admittance | 23 (19–27) | 25 (23–27) | 0.816 |

| Positive sputum culture at admittance | 25 (32.9) | 10 (41.7) | 0.432 |

| CURB-65 score at admittance | |||

| 0–1 | 53 (69.7) | 17 (70.8) | 0.630 |

| 2 | 20 (26.3) | 5 (20.8) | |

| 3–5 | 3 (3.9) | 2 (8.3) |

Data are presented as n, n (%) or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise stated. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity; BMI: body mass index; ICS: inhaled corticosteroids; CCQ: Clinical COPD Questionnaire; c-LRTI-VAS: COPD lower respiratory tract infection visual anaologue score; CURB-65: confusion, urea >7 mmol·L−1, respiratory rate ≥30 breaths·min−1, blood pressure <90 mmHg (systolic) ≤60 mmHg (diastolic), age ≥65 years. #: last recorded post-bronchodilator value in a stable state before admission.

The different types of radiological abnormalities are summarised in table 2.

TABLE 2.

Types of radiological abnormalities#

| Consolidation | 15 (62.5) |

| Tree in bud | 12 (50.0) |

| Reticular changes | 9 (37.5) |

| Bronchopathy | 7 (29.2) |

Data are presented as n (%). #: n=24.

Results regarding sputum cultures are presented in table 3.

TABLE 3.

Sputum culture

| No radiological abnormalities present | Radiological abnormalities present | p-value | |

| Patients | 76 | 24 | |

| Representative sputum culture # | 25 (32.9) | 10 (41.7) | 0.432 |

| Isolated pathogens from sputum | |||

| Haemophilus influenzae | 10 (40.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.580 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 6 (24.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.714 |

| Haemophilus parainfluenzae | 6 (24.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.799 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3 (12.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.061 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 1 (4.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.127 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 5 (20) | 0 (0.0) | 0.127 |

| Escherichia coli | 1 (4.0) | 2 (20.0) | 0.127 |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.521 |

Data are presented as n or n (%), unless otherwise stated. #: sputum was representative according to the Bartlett criteria: sputum sample with >25 polymorphonuclear leukocytes and <10 squamous epithelial cells per low-power field was defined as a sputum sample representative of the lower airways.

Additional information regarding microbiological results in relation to the presence of radiological abnormalities can be found in supplementary tables S1 and S2.

Interobserver variation

The observed proportional agreement (P0) in LDCT judgement of observed abnormalities by radiologists A and B was 84.0%. The proportional agreement by chance (Pe) was 63.5%, resulting in a κ of 0.562 (95% CI 0.371–0.752; p<0.001), reflecting moderate agreement. The proportional agreement in positive cases (69.6%) was lower than the proportional agreement in negative cases (88.3%). 52 patients were scanned on a 128-detector-row scanner and 48 on a 16-detector row scanner. On the 16-detector-row scanner the agreement was 85.4% with a κ of 0.543 (95% CI 0.249–0.816). On the 128-detector-row system, the agreement was 82.7% with a κ of 0.575 (95% CI 0.333–0.816).

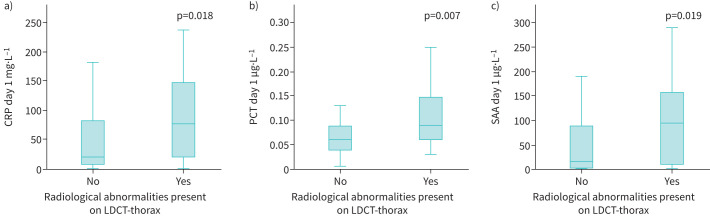

Biomarkers

All biomarkers were significantly higher in the group with radiological abnormalities on the LDCT compared to those without radiological abnormalities. CRP was 20.5 (IQR 8.8–81.5) mg·L−1 in the group without radiological abnormalities compared to 76 (IQR 21.5–148.0) mg·L−1 (p=0.018) in the group with abnormalities (figure 3a), whereas PCT was 0.06 (IQR 0.04–0.08) µg·L−1 in the group without radiological abnormalities compared to 0.09 (IQR 0.06–0.15) µg·L−1 (p=0.007) in the group with radiological abnormalities (figure 3b). SAA was 16 (IQR 3–89) µg·mL−1 in the group without radiological abnormalities compared to 95 (IQR 7–160) µg·mL−1 (p=0.019) in the group with abnormalities (figure 3c). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for CRP was 0.66 (95% CI 0.52–0.80), for PCT 0.66 (95% CI 0.53–0.80) and for SAA 0.69 (95% CI 0.57–0.81). The optimal cut-off value to identify radiological abnormalities was 43 mg·L−1 for CRP, with a sensitivity of 0.70 and a specificity of 0.68. The optimal cut-off point for PCT to identify radiological abnormalities was 0.05 µg·L−1, with a sensitivity of 0.78 and a specificity of 0.47. The optimal cut-off point for SAA to identify radiological abnormalities was 27 µg·mL−1, with a sensitivity of 0.70 and a specificity of 0.65.

FIGURE 3.

a) C-reactive protein (CRP) level in patients with and without radiological abnormalities; b) procalcitonin (PCT) level in patients with and without radiological abnormalities; c) serum amyloid A (SAA) level in patients with and without radiological abnormalities. LDCT: low-dose computed tomography.

Discussion

In this exploratory study, we show that 24% of the patients with AECOPD admitted to hospital without evidence of pneumonia on chest radiography had additional radiological abnormalities on LDCT. In patients with radiological abnormalities on LDCT, the levels of CRP, PCT and SAA were higher than in those without LDCT abnormalities. However, we were unable to reliably exclude or confirm the diagnosis of CAP using these biomarkers.

The incidence of infiltrative changes in AECOPD not detected by chest radiography was considerably higher than in an earlier study, among 47 patients suspected to have CAP; while confirming CAP in 18 patients, in eight further patients, CAP could be detected with high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) [22]. The higher number of infiltrates found in this study may be explained by a difference in baseline population, as our study consisted of hospitalised patients with AECOPD, while the aforementioned study consisted of patients with fever and cough from the general population.

The κ-value of agreement between the two radiologists was moderate (0.562), and lower compared to some previous studies [22]. This can probably be explained by a combination of small infiltrates that are more difficult to diagnose, and the use of LDCT instead of HRCT [22].

CRP, SAA and PCT were elevated in the group with consolidations. However, they were considerably lower compared to other studies in patients with radiographic confirmed pneumonia [24, 25]. The biomarkers reported in the group without radiological abnormalities were comparable to an earlier study in patients with AECOPD [11]. CRP, SAA and PCT showed poor sensitivity and specificity for the prediction of radiological abnormalities on LDCT. In part, this might be due to the fact that all biomarkers in this study are used in the detection of bacterial infection, whereas these radiological abnormalities can also be caused by viral infections [11, 26]. This might subsequently lead to a lower level of these biomarkers compared to bacterial infection [27, 28]. To complicate matters further, definite diagnosis of viral or bacterial origin cannot be achieved using imaging features alone. However, recognition of viral pneumonia patterns may help in differentiation between viral pathogens and bacterial pathogens, with subsequent reduction of unnecessary use of antibiotics [29].

A potential strength of this study is that all data were collected prospectively, thereby not resulting in selection bias. Another strength is the fact that radiologists were blinded to clinical data except for age and gender, so this could not have influenced their judgement. A potential limitation is design of our study, as patients were allowed to have a 12-h time gap between the initial chest radiography and the LDCT. Infiltrative changes may progress over time, which may have led to progression or emergence of new radiological abnormalities. The second limitation is the prescription of antibiotics or systemic corticosteroids prior to inclusion. We cannot exclude that these pre-treated patients may have altered biomarker performance, or that remnants of infiltrates invisible to chest radiography still can be detected on CT. The third potential limitation is the fact that CT cannot discriminate between viral and bacterial CAP, as only invasive local microbiological sampling would have provided this diagnostic precision [29]. As we did not gather these data, results regarding the differences between biomarker levels and LDCT findings should be interpreted with caution. A fourth weakness is that this is an explorative study and not powered to detect differences in biomarkers. Finally, our study was performed between 2011 and 2014. CT detector and reconstruction technology is evolving continuously. Iterative reconstruction lowered noise (and dose), but altered the lung appearance in some instances. With the most recent CT advances, resolution can be further improved. It may be that the detection of pneumonia will even further improve and that we missed some very subtle cases.

AECOPD and pneumonia have considerable symptomatic overlap, and ruling out CAP using chest radiography is often difficult. We have shown that using LDCT, it is possible to detect additional radiological abnormalities in patients with AECOPD. However, the question remains what the outcome means for the individual patient, as the abnormalities found are diverse and do often not reflect a specific aetiology. Biomarkers are increased in patients with infiltrative changes on their LDCT. Yet CRP, PCT and SAA did not carry sufficient weight to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of CAP in this specific population. Therefore, further research is necessary to determine whether the presence of additional infiltrative changes on LDCT represents a categorically different disease process or rather a spectrum of infection, especially in the light of the similarity between clinical characteristics and microbiology.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00054-2022.SUPPLEMENT (17KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov with identifier number NCT01232140. All data will be made available after de-identification, including the protocol, with no limit. Data will be made available immediately after publication. Data will be made available upon reasonable request to researchers with a methodological sound proposal. Proposals should be directed to w.boersma@nwz.nl.

Conflict of interest: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, Clinch JJ, et al. Measurement of short-term changes in dyspnea and disease-specific quality of life following an acute COPD exacerbation. Chest 2002; 121: 688–696. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.3.688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seemungal TA, Donaldson GC, Paul EA, et al. Effect of exacerbation on quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998; 157: 1418–1422. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9709032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shin B, Kim SH, Yong SJ, et al. Early readmission and mortality in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with community-acquired pneumonia. Chron Respir Dis 2019; 16: 1479972318809480. doi: 10.1177/1479972318809480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steer J, Norman EM, Afolabi OA, et al. Dyspnoea severity and pneumonia as predictors of in-hospital mortality and early readmission in acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax 2012; 67: 117–121. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aaron SD. Management and prevention of exacerbations of COPD. BMJ 2014; 349: g5237. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Müllerova H, Maselli DJ, Locantore N, et al. Hospitalized exacerbations of COPD: risk factors and outcomes in the ECLIPSE cohort. Chest 2015; 147: 999–1007. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres A, Peetermans WE, Viegi G, et al. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults in Europe: a literature review. Thorax 2013; 68: 1057–1065. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Titova E, Christensen A, Henriksen AH, et al. Comparison of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, white blood cell count and clinical status in diagnosing pneumonia in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbations of COPD: a prospective observational study. Chron Respir Dis 2019; 16: 1479972318769762. doi: 10.1177/1479972318769762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander SR, et al. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 2005; 365: 579–587. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17907-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seppälä H, Klaukka T, Vuopio-Varkila J, et al. The effect of changes in the consumption of macrolide antibiotics on erythromycin resistance in group A streptococci in Finland. Finnish Study Group for Antimicrobial Resistance. N Engl J Med 1997; 337: 441–446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708143370701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bafadhel M, McKenna S, Terry S, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: identification of biologic clusters and their biomarkers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 184: 662–671. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201104-0597OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniels JM, Schoorl M, Snijders D, et al. Procalcitonin vs C-reactive protein as predictive markers of response to antibiotic therapy in acute exacerbations of COPD. Chest 2010; 138: 1108–1115. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurst JR. Consolidation and exacerbation of COPD. Med Sci 2018; 6: 44. doi: 10.3390/medsci6020044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Self WH, Courtney DM, McNaughton CD, et al. High discordance of chest x-ray and computed tomography for detection of pulmonary opacities in ED patients: implications for diagnosing pneumonia. Am J Emerg Med 2013; 31: 401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2012.08.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karimi E. Comparing sensitivity of ultrasonography and plain chest radiography in detection of pneumonia; a diagnostic value study. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2019; 7: e8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claessens YE, Debray MP, Tubach F, et al. Early chest computed tomography scan to assist diagnosis and guide treatment decision for suspected community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192: 974–982. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0017OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waterer GW. The diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Do we need to take a big step backward? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192: 912–913. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1460ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith-Bindman R, Lipson J, Marcus R, et al. Radiation dose associated with common computed tomography examinations and the associated lifetime attributable risk of cancer. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169: 2078–2086. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park JE, Kim Y, Lee SW, et al. The usefulness of low-dose CT scan in elderly patients with suspected acute lower respiratory infection in the emergency room. Br J Radiol 2016; 89: 20150654. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prins HJ, Duijkers R, van der Valk P, et al. CRP-guided antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of COPD in hospital admissions. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1802014. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02014-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease . Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of COPD. 2019. Available from: http://goldcopd.org/.

- 22.Syrjälä H, Broas M, Suramo I, et al. High-resolution computed tomography for the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 27: 358–363. doi: 10.1086/514675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole S, Walker D, Gaines Das RE, et al. The first international standard for serum amyloid A protein (SAA). Evaluation in an international collaborative study. J Immunol Methods 1998; 214: 1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(98)00057-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Çolak A, Yılmaz C, Toprak B, et al. Procalcitonin and CRP as biomarkers in discrimination of community-acquired pneumonia and exacerbation of COPD. J Med Biochem 2017; 36: 122–126. doi: 10.1515/jomb-2017-0011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takata S, Wada H, Tamura M, et al. Kinetics of C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum amyloid A protein (SAA) in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), as presented with biologic half-life times. Biomarkers 2011; 16: 530–535. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2011.607189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Le Bel J, Hausfater P, Chenevier-Gobeaux C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of C-reactive protein and procalcitonin in suspected community-acquired pneumonia adults visiting emergency department and having a systematic thoracic CT scan. Crit Care 2015; 19: 366. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1083-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lannergård A, Larsson A, Kragsbjerg P, et al. Correlations between serum amyloid A protein and C-reactive protein in infectious diseases. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2003; 63: 267–272. doi: 10.1080/00365510310001636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noviello S, Huang DB. The basics and the advancements in diagnosis of bacterial lower respiratory tract infections. Diagnostics 2019; 9: 37. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics9020037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koo HJ, Lim S, Choe J, et al. Radiographic and CT features of viral pneumonia. Radiographics 2018; 38: 719–739. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00054-2022.SUPPLEMENT (17KB, pdf)