Abstract

Background

The global COVID-19 pandemic has challenged nurse leaders in ways that one could not imagine. Along with ongoing priorities of providing high quality, cost-effective and safe care, nurse leaders are also committed to promote an ethical climate that support nurses’ moral courage for sustaining excellence in patient and family care.

Aim

This study is directed to develop a structure equation model of crisis, ethical leadership and nurses’ moral courage: mediating effect of ethical climate during COVID-19.

Ethical consideration

Approval was obtained from Ethics Committee at Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University, Egypt.

Methods

A cross-sectional design was used to conduct this study using validated scales to measure the study variables. It was conducted in all units of two isolated hospitals in Damanhur, Egypt. A convenient sample of 235 nurses was recruited to be involved in this study.

Results

This study revealed that nurses perceived a moderate mean percent (55.49 ± 3.46) of overall crisis leadership, high mean percent (74.69 ± 6.15) of overall ethical leadership, high mean percent (72.09 ± 7.73) of their moral courage, and moderate mean percent of overall ethical climate (65.67 ± 12.04). Additionally, this study declared a strong positive statistical significant correlation between all study variables and indicated that the independent variable (crisis and ethical leadership) can predict a 0.96, 0.6, respectively, increasing in the dependent variable (nurses’ moral courage) through the mediating impact of ethical climate.

Conclusion

Nursing administrators should be conscious of the importance of crisis, ethical leadership competencies and the role of ethical climate to enhance nurses’ moral courage especially during pandemic. Therefore, these findings have significant contributions that support healthcare organizations to develop strategies that provide a supportive ethical climate. Develop ethical and crisis leadership competencies in order to improve nurses' moral courage by holding meetings, workshops, and allowing open dialogue with nurses to assess their moral courage.

Keywords: COVID-19, structure equation model, crisis leader, ethical leader, nurses’ moral courage, ethical climate

Introduction

The current coronavirus pandemic has presented a huge challenge and placed enormous pressure and unprecedented demands on all of us including those in leadership positions. Despite there is a lack of research in the field of crisis and ethical leadership particularly in health care.1 The coronavirus pandemic has prompted a critical appraisal of the evidence around crisis and ethical leadership during times of pandemic; this pandemic period is defined as an unpredictable incident that poses significant risk to an organization. During this pandemic period, nurse leader encounter situations with conflicting ethical values daily.2 The prevalence of ethical problems together with the moral goal of nursing, that is, the patient’s optimal well-being, renders nursing an ethical enterprise throughout. To solve ethical problems and to fulfill the moral quest of the profession, nurses need moral courage.3 However, a copious number of studies have evidenced that nurses suffer from unresolved ethical problems causing them moral distress with adverse consequences.4,5 Thus, nurses need a climate that enables them to meet their role and foster resolving these ethical problems; this is called ethical climate.6

Underpinning Theory

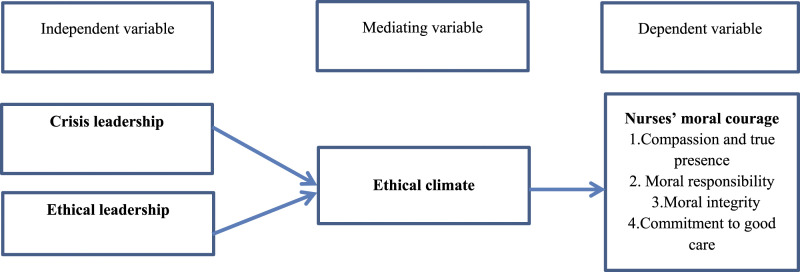

Bandura Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)7 has been deployed to explain the proposed theoretical framework. This theory proposed that there is a mutual relationship between personal factors, behavior, and environment and these factors constantly affect each other. An integral component in social learning theory is reciprocal determinism, which states that learning is the direct outcome of cognitive processes unraveling and subsequently being learned in a social setting. According to this theory, people will not directly imitate the behavior of their role model to shape their own desired positive or negative actions; it depends on the mechanism between the stimuli and responses. When people will monitor their stimuli like their role model or leader behavior which is according to the value of internal function or match with the worth of organization and extensively acceptable then due to cognitive thinking of individual, certain feelings, emotion, or intuitions will evoke to appraise the behavior of their model and decide either to imitate or not. When people will imitate their role model or stimuli behavior due to the positive feeling, emotion, or intuition about the role model behavior then they will be motivated to act accordingly as similar to their role model. Embedding social learning in the proposed model, we argue that employees learn from the crisis and ethical leader as their role models and indulge in ethical climate as cognition process. In line with the theory, they further imitate the behavior of crisis and ethical leader in the form of moral courage at workplace. This theoretical framework is considered as a golden rule for building our proposed conceptual framework (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proposed conceptual framework.

Crisis leadership

Crisis leaders often have influence over the impact of pending crises by either preventing or minimizing it. With crisis looming just around the corner, a leader’s ability to identify, avert, and manage a crisis has become a fundamental element in organizational sustainability.8 Christensen9 defined crisis leadership as “a process of responding to a low-probability, high-impact situation by influencing others to overcome or take advantage of the situation, regardless of its cause, optimizing the effect, in a timely framework.” They see the big picture, have an ability to link improbable events together in order to interpret a potential crisis, continuously engage in pre-crisis audits to identify warning signs, and have an ability to redesign an organization toward greater resiliency following a crisis.10

Brownlee-Turgeon11 declared that crisis leader has three competencies; Participatory management is the inclusion of employees in terms of communication, training, information, solutions, and interactions; Resourcefulness focuses on a leader’s ability to be agile in terms of resources. It includes agility in terms of decision making, identifying opportunities, actions, adapting to circumstances, handling information, deploying resources or assessment of the situation along with a confidence in one’s ability to navigate a system fluidly; and sense making emphasizes on the ability of the leader to identify warning signs of a looming crisis and bring it to the attention of others.

Ethical leadership

Brown et al.12 declared that ethical leader is controlled by a system of accepted beliefs and appropriate judgments rather than self-related interest, which is beneficial for followers, organizations, and society. They defined ethical leadership as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions, interpersonal relationships and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement and decision making”.12 Kalshoven et al.13 explained it through seven domains; fairness in which leader treat others fairly, create principled and fair choices, do not practice favoritism, and accept responsibility for their own actions. Power sharing is an empowering aspect, through allowing subordinates to share in making decision, be more independent on themselves rather than their leaders and more control over their work.

Role clarification aims to clarifying performance goals and expectations so nurses become aware of what is expected from them and achieve organization’s goals. People orientation reflects caring behavior, having a true concern for people respecting, and supporting subordinates and ensuring that their needs are met. Ethical guidance implies communication about ethics, explanation of ethical rules, and promotion and reward of ethical conduct among subordinates. Integrity behavior is the extent to which what one says is in line with what one does. Concern for sustainability focuses on the development of others in the environment, distribution of responsibilities, and endurance over time.13,14

So, ethical leadership is described as the process of influencing people through principles, values, and beliefs. It is composed of two basic elements; first, ethical leaders must act and make decisions in an ethical manner just as would all ethical persons. Second, ethical leadership must be seen in the way they interact with people daily, in their attitudes and in the way they lead their organizations. Consequently, ethical leaders are generally the leaders who build meaningful relationships with followers, model upstanding behavior, prioritize process over results, and encourage two-way communication.15 Otherwise, crisis leadership is the process of responding to an organization’s challenges and preventing them from occurring in the future. Most crisis leaders emphasize the needs of their employees and customers by providing emotional support. For instance, they might acknowledge their concerns and maintain clear communication throughout the crisis. People who use this leadership style also focus on the long-term implications of challenging events. By analyzing response methods, revising them and asking for support from employees and customers, they can develop effective plans to manage future crises.16 Subsequently, leadership is an important organizational context that shape subordinates’ behaviors as moral courage.17

Nurses’ moral courage

Moral courage has been presented as a concept needing more attention in terms of expanding nurses’ social-moral space, bringing alleviation to moral distress, and preserving nurses’ moral integrity.18 Khodaveisi et al.19 defined moral courage as the courage to act according to one’s own ethical values and principles even at the risk of negative consequences for the individual. It helps caregivers to provide professional care to the patient, families, and society. In nursing, Khoshmehr et al.20 described moral courage as the nurse’s ability to overcome fear by confronting an issue head on when the issue is in conflict with the nurse’s core professional values.

Numminen et al.21 proposed four construct of moral courage; compassion and true presence that describes care situations which encountering the patient’s vulnerability in sickness and suffering demands the nurse to overcome her or his own inner fears forcing the nurse to encounter her or his own vulnerability in order to be able to act courageously. Moral responsibility concentrates on courage needed to take responsibility in care situations impregnated with inherent moral uncertainty. Moral integrity focuses on adhering to the principles and values of the profession and health care in general, particularly in situations where taking the risk of negative consequences from others is a possibility, thus focusing on the very core of moral courage. Commitment to good care deals with care situations in which good nursing care is threatened due to deficient resources or poor professional competence, detrimental and compromising practices, or coercion.

Ethical climate

Newman et al.22 defined ethical work climate as ‟ the prevailing attitudes about the organization standards concerning appropriate conduct in the organization which sets the tone for decision making at all levels in all circumstances.” The creation of strong ethical climate within healthcare organization is considered as mediating factor affecting nurses’ perception about the nature of the relational contract between nurses themselves and their organization.23 Cullen et al.24 classified it into nine dimensions, namely, self-interest, efficiency, personal morality, organizational profit, friendship, organizational rules and procedures, team interest, laws and professional codes, and social responsibility. Ethical climate has been proved to be a mediating factor in several researches as Refs. 25–28 while, there was no study conducted to examine its role during COVID-19 pandemic period.

Mediating role of ethical climate

Studies show that nurses with high level of moral courage provide high quality of care specifically in dealing with dying and poor patients, entails invasive care, tackling with the newfound diseases and emergencies such as new crisis of COVID-19 (Numminen et al.;21 Khodaveisi et al.19). However, the previous studies have reported that ethical leadership directly affects moral courage without the mediating effect of the ethical climate and the leadership can impact on each employee`s moral courage theoretically.17,29 But in this study, we contend that the presence of high level ethical climate as a mediating factor with high level of crisis, ethical leadership would increase the degree of effect in this relation to reach high level of moral courage that supports nurses during COVID-19 crisis other than any day-to-day operations. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT)7 is a citadel that provides a support for this mediating relationship. According to this theory, when employees burgeon positive beliefs about an organization, they develop a tendency to reciprocate the just and fair treatment of their organization based on the rule of reciprocity. Following this theory, nurses after perceiving the crisis, ethical leadership, and ethical climate of their organization reciprocate this behavior in the disposition of a higher level of moral courage.

Justification of study

The most recent COVID-19 pandemic had added an additional layer of hardship to the already overburdened and over challenged system. Health leaders have become accustomed to shift priorities and function in a rapidly changing environment, often reacting or responding to the “crisis of the day.” This has had significant implications on how leaders manage and navigate their days.30 According to the State Expert Panel on the Ethics of Disaster Preparedness in collaboration with the Wisconsin Hospital Association and Wisconsin Public health,31 there are multiple ethical responsibilities health leaders need to be cognizant of and demonstrate in their day-to-day behaviors. Ethical leaders are expected to provide consistent and rational leadership, especially when leading through crises, such as COVID-19. In addition, those ethical leaders are able to impact on their followers to be moral, ethical, and committed to their organizations. Thus, ensuring that the organization is guided by an ethical framework that supports its vision, mission, values, and culture is essential in preventing ethical dilemmas, conflicts, and tensions. Being recognized as an ethical organization that creates an ethical climate is vital in garnering the public’s trust in the services and care delivered within its walls and their leaders are responsible for creating a workplace based on integrity, accountability, fairness, and respect.

Additionally, Khodaveisi et al.19 reported that nurses are the first health advocates against the crisis caused by the COVID-19; they need strong moral courage. Besides, the American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE)32 has advocated for the creation of healthful work environments that support moral courage, strong leadership practices, and effective ethical climate. However, no researches found to investigate nurses’ moral courage, its relation to crisis, ethical leadership in presence of ethical climate during. Therefore, this gap will be fulfilled by developing a structure equation model of the study variables.

Research hypotheses

From the conceptualization of study’s variables, crisis leadership and ethical leadership can be considered as the independent variables in this study, and moral courage as the dependent variables, and ethical climate as a mediating variable. Therefore, the following hypotheses were postulated to answer research question (see Figure 1):

What is the impact of crisis, ethical leadership on nurses’ moral courage, through ethical climate as a mediating factor?

Null H0: There is no significant impact of crisis, ethical leadership on nurses’ moral courage, through ethical climate as mediating factor.

Alternative H1: There is a significant impact of crisis, ethical leadership on nurses’ moral courage, through ethical climate as mediating factor.

The aim of this study

This study aims to develop a structural equation model of crisis, ethical leadership and nurses’ moral courage during COVID-19 pandemic the role of ethical climate as a mediating factor.

Methods

Research design and setting

A cross-sectional and correlation study was conducted through validated scales to measure the study variables based on the proposed framework. This study was conducted in all units of two isolated hospitals, namely, Damanhur fever hospital (n = 9 units) and Damanhur chest hospital (n = 7 units) which affiliated to the Ministry of Health and Population at El-Bohera Governorate, Egypt and are specialized in caring for patients with COVID-19.

Participant

The target population was nursing staff who were in charge of caring for Covid 19 patients and agreed to participate in this study. A non-probability, convenient sample of 235 nurses out of 346 nurses were recruited to participate in this study based on Epi-info calculated as following: Total population of nurses = 346; Acceptable error = 5%; α = 0.05; this test denotes that confidence coefficient = 99% with sample size (n = 235). All nurses that were determined based Epi-info participated in this study, and no one dropped out (100% response).

Tools of this study

Four standardized questionnaires were used in this empirical study, namely, crisis leadership questionnaire, Ethical Leadership Work Questionnaire (ELW), Nurses’ Moral Courage Scale (NMCS), and Ethical Work Climate Questionnaire (EWC):

(1) Crisis Leadership Questionnaire: it was developed by Brownlee-Turgeon11 to measure leader ability to identify and avert the crisis. It is composed of 35 items divided into three main dimensions, namely, Participatory Management (17 items), Resourcefulness (7 items), and sense making (11 items). The response was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. Overall score level ranged from 35 to 175.

(2) Ethical Leadership Work Questionnaire (ELW): This was developed by Brown et al.12 and validated by Kalshoven et al.13 It consisted of 38 items classified into seven dimensions, namely, people orientation (7 items), fairness (6 items), power sharing (6 items), concern of sustainability (3 items), ethical guidance (7 items), role clarification (5 items), and integrity (4 items). The response was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. The reversed score was applied for negative statements (9 items). The overall score level ranged from 38 to 190.

(3) Nurses’ Moral Courage Scale (NMCS): It was developed by Numminen et al.21 It consisted of 21 items measuring nurses’ self-assessed level of moral courage within four dimensions: compassion and true presence (5 items), moral responsibility (4 items), moral integrity (7 items), and commitment to good care (5 items). The response was measured on a 5-point Likert scale: (1) Does not describe me at all through to (5) Describes me very well. The overall score level ranged from 21 to 105.

(4) Ethical Work Climate Questionnaire (EWC): It was developed by Cullen et al.24 to measure the ethical work climate as perceived by nurses. It consisted of 36 items that are classified into nine dimensions: self-interest, efficiency, personal morality, organizational profit, friendship, organizational rules and procedures, team interest, laws and professional codes, and social responsibility. Each dimension composed of 4 items. The response was measured on 6-point Likert scale ranged from (0) completely false to (5) completely true. The reversed score was applied for negative statements (5 items). The overall score level ranged from 0 to 180.

In addition, demographic characteristics of the study subject including questions related to age, gender, marital status, educational qualification, and years of work experience.

Validity and reliability

The study tools were tested for internal reliability using Cronbach’s alpha correlation coefficient. The results proved four tools reliable with a correlational coefficient α = 0.950, 0.886, 0.940, and 0.910 for crisis leadership, ethical leadership, nurses’ moral courage, and ethical climate, respectively, while the statistical significance level was set at p < 0.05. Tools were translated into the Arabic language to be suited for Egyptian culture and tested for content validity along with the fluency of the translation by jury of five academic members in the field of study including, two professors and a lecturer from Nursing Administration Department, and Professor and Assistant Professor from Medical-Surgical Nursing Department. Accordingly, some items were modified for more clarity. Then, tools were back-translated into English by language experts. The back-translations were reviewed by the researchers and members of the jury to ensure accuracy and minimize potential threats to the study’s validity.

In addition, a pilot study was conducted on 23 nurses (10%) who were excluded from the study subjects to ensure the clarity and applicability of tools and estimate the time required to complete the study questionnaires. In the light of the findings of the pilot study, no changes occurred in the final tools.

Data collection

Written approval was obtained from administrative authority in the identified setting to collect the necessary data. The link of the questionnaires were sent by the researchers to the nurses who agreed to participate in the study via social media as WhatsApp and Email after done on Google Form by the researcher. Each nurse took about 30 min to complete the questionnaires. Data were collected from nurses after obtaining their acceptance using the questionnaires in 5 months, from January to May of 2021.

Ethical considerations

Approval was obtained from Ethics Committee at Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University. The researchers explained the aim of the research to all participants. The privacy and confidentiality of data were maintained and assured by obtaining participants’ informed consent to participate in the research before data collection. The questionnaire and informed consent forms were sent for participating nurses through sharing link using end-to-end encryption and security of platforms used to deliver online surveys. Voluntarily and anonymity concerning participation in this study were granted.

Analysis

The data were analyzed in SPSS and AMOS Ver. 23. The demographic characteristics of the participants, crisis leadership, ethical leadership, ethical climate, and nurses’ moral courage prevalence were analyzed proportionally using frequency, percentage, mean percent, and standard deviation (SD) where mean percent score of more than 66.6% indicates high perception of nurses, mean percent score from 66.6% to 33.3% considered as moderate perception while mean percent score less than 33.3% regarded as low perception. Also, the relationships between crisis leadership, ethical leadership, ethical climate, and nurses’ moral courage were determined using Pearson’s correlations. Cronbach’s alpha was conducted to assess tools reliability. AMOS Ver. 23 was used to examine structural equation modeling (SEM) and determine the mediation effect. The model was suitable by assessing the degree to which all the latent variable structures fit the model. If all the latent variables were well represented by the indicators, then the confirmed structure of the model fit indices included assessment of chi-square values, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Radio Frequency Interference (RFI). A significant chi-square value indicates a good fit between the model and the data. A RMSEA value of less than 0.08 implies an acceptable fit,33 and RFI, NFI, and CFI values exceeding 0.90 indicate a good fit. (The path coefficients were accepted as significant at the 0.05 level.)34

Results

Background characteristics of the participants

The mean age of the staff nurses was 34.20 ± 7.72 years. Half of them were in the age group of 30–40 years old while more than one-third of them were in the age group less than 30 years. The majority of them (93.6%) were female and more than two third (66.6%) were married. Concerning educational qualification, 43.5% of them had a bachelor degree of nursing science. The mean years of experience was 9.12 ± 5.24 years with 30.9% of them having from 5 to less than 10 years of experience; however, 10.0% had more than 15 years of experience in nursing profession.

Table 1 declares that nurses perceived a moderate mean percent (55.49 ± 3.46) of overall crisis leadership which is illustrated in moderate mean percent of its dimensions in the following ordered participatory management (54.20 ± 3.08), resourcefulness (52.80 ± 6.99), and sense making (51.41 ± 7.33).

Table 1.

Nurses’ perception of their crisis leadership.

| Crisis leadership | Min.–Max. | Mean ± SD. |

|---|---|---|

| Participatory management | 47.50–63.75 | 54.20 ± 3.08 |

| Resourcefulness | 37.14–68.57 | 52.80 ± 6.99 |

| Sense making | 41.82–74.55 | 51.41 ± 7.33 |

| Overall crisis leadership | 50.00–64.12 | 55.49 ± 3.46 |

From nurses perspective, Table 2 concludes that nurses perceived a high mean percent (74.69 ± 6.15) of overall ethical leadership which is reflected in all ethical leadership dimensions in the following ordered; fairness (74.57 ± 6.73), people orientation (73.09 ± 73.09), power sharing (70.89 ± 5.63), role clarification (70.58 ± 15.65), ethical guidance (69.97 ± 12.30), concern for sustainability (66.92 ± 15.12), and integrity (66.46 ± 12.08).

Table 2.

Nurses’ perception of their ethical leadership.

| Ethical leadership | Min.–Max. | Mean ± SD. |

|---|---|---|

| People orientation | 60.00–85.71 | 73.09 ± 73.09 |

| Fairness | 53.33–90.00 | 74.57 ± 6.73 |

| Power sharing | 56.67–86.67 | 70.89 ± 5.63 |

| Concern for sustainability | 40.00–100.00 | 66.92 ± 15.12 |

| Ethical guidance | 42.86–94.29 | 69.97 ± 12.30 |

| Role clarification | 40.00–100.00 | 70.58 ± 15.65 |

| Integrity | 40.00–100.00 | 66.46 ± 12.08 |

| Overall ethical leadership | 58.79–82.11 | 74.69 ± 6.15 |

Data in Table 3 presents that nurses perceived high mean percent score (72.09 ± 7.73) of their moral courage which is clarified by of all its dimensions in this order compassion and true presence (74.54 ± 19.69), commitment to good care (73.65 ± 23.88), moral responsibility (71.57 ± 8.05), and finally, moral integrity (69.54 ± 4.90).

Table 3.

Nurses’ perception of their moral courage.

| Nurses’ moral courage | Min.–Max. | Mean ± SD. |

|---|---|---|

| Compassion and true presence | 56.00–184.00 | 74.54 ± 19.69 |

| Moral responsibility | 55.00–90.00 | 71.57 ± 8.05 |

| Moral integrity | 62.86–85.71 | 69.54 ± 4.90 |

| Commitment to good care | 48.00–192.00 | 73.65 ± 23.88 |

| Overall nurses’ moral courage | 60.00–98.10 | 72.09 ± 7.73 |

Table 4 illustrates that nurses perceived moderate mean percent of overall ethical climate (65.67 ± 12.04) declared in a moderate mean of its related dimension; social responsibility (65.17 ± 19.00), friendship (64.02 ± 16.56), team interest (62.55 ± 17.91), organizational profit (62.44 ± 14.23), and self-interest (54.47 ± 19.01). However, nurses perceived high mean percent of the other dimension; efficiency (72.70 ± 18.12), organizational rules and procedures (72.17 ± 18.92), personal morality (70.25 ± 17.54), and laws and professional codes (67.29 ± 17.66).

Table 4.

Nurses’ perception of their ethical climate.

| Ethical climate | Min.–Max. | Mean ± SD. |

|---|---|---|

| Self-interest | 20.00–100.00 | 54.47 ± 19.01 |

| Efficiency | 25.00–100.00 | 72.70 ± 18.12 |

| Personal morality | 25.00–100 | 70.25 ± 17.54 |

| Organizational profit | 30.00–100.00 | 62.44 ± 14.23 |

| Friendship | 20.00–100.00 | 64.02 ± 16.56 |

| Organizational rules and procedures | 15.00–10.00 | 72.17 ± 18.92 |

| Team interest | 20.00–100.00 | 62.55 ± 17.91 |

| Laws and professional codes | 20.00–100.00 | 67.29 ± 17.66 |

| Social responsibility | 20.00–100.00 | 65.17 ± 19.00 |

| Overall ethical climate | 40.56–97.22 | 65.67 ± 12.04 |

Table 5 proves that there was a highly statistical significant positive correlation between overall crisis leadership and nurses moral courage where p = 0.000. Also, there was a highly statistical significance positive correlation between overall ethical leadership and overall nurses’ moral courage where p = 0.034. Additionally, it can be seen that there was a highly statistical significant positive correlation between overall ethical climate and overall moral courage where p = 0.000

Table 5.

Correlation matrix of crisis leadership, ethical leadership, nurses’ moral courage and ethical climate.

| Overall crisis leadership | Overall ethical leadership | Overall moral courage | Overall ethical climate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall crisis leadership | R | 1 | 0.171 (**) | 0.227 (**) | 0.316 (**) |

| Sig. | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

| Overall ethical leadership | R | 0.171 (**) | 1 | 0.138 (*) | 0.386 (**) |

| Sig. | 0.009 | 0.034 | 0.000 | ||

| Overall moral courage | r | 0.227 (**) | 0.138 (*) | 1 | 0.493 (**) |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.034 | 0.000 | ||

| Overall ethical climate | r | 0.316 (**) | 0.386 (**) | 0.493 (**) | 1 |

| Sig. | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

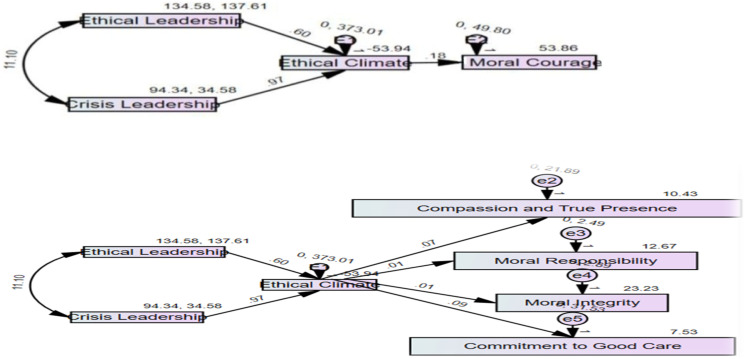

Figure 2 and Table 6 indicate the structure equation model results upon adding the mediating variable (Ethical Climate). They show that the estimated beta indicated that the independent variable (ethical leadership and crisis leadership) can predict a 0.6, 0.96, respectively, increasing in the dependent variable (nurses’ moral courage) through the mediating impact of ethical climate. The R2 value indicates that ethical leadership and crisis leadership can explain 12.6%, 9.99% of nurses’ moral courage through the impact of ethical climate. The coefficient of determination value in this relationship is the highest of all the previous values, which is accredited to the importance of the mediator. The p-value here is (0.001) which is highly significant; thus, this result shows that there is impact of both independent variables on dependent variable through mediating variable. This outcome indicates that the H1 hypothesis is accepted and the null hypothesis is rejected.

Figure 2.

Path analysis for direct and indirect effect of crisis leadership, ethical leadership on nurses’ moral courage mediated by ethical climate.

Table 6.

Path Analysis for Direct and Indirect Effect of crisis leadership, ethical Leadership on nurses’ moral courage Mediated by ethical climate.

| Path model estimates | Estimate | R2 | SE. | C.R. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall ethical leadership | Ethical climate | 0.6 | 0.126 | 0.111 | 5.426 | *** | |

| Crisis leadership | Ethical climate | 0.969 | 0.0997 | 0.218 | 4.444 | *** | |

| Ethical climate | Moral courage | 0.185 | 0.243 | 0.021 | 8.663 | *** | |

Note. r = Pearson correlation; CFI = Comparative fit index; NFI = Normed fit index; RFI= Radio Frequency Interference and RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

Model X2; significance 3.431; 0.001.

Model fit parameters CFI; NFI; RFI; RMSEA (0.987; 0.972; 0.862; 0.055).

Discussion

A key challenge of a pandemic as COVID-19 is that an effective management of the situation requires large-scale human behavior change and integrative effort. Also, the influential factor in crisis leadership style seems to be the level of unpredictability due to the number of risk components involved in the situation and their novelty, which requires joining forces and cognitive diversity. Another aspect is the motivating force which put pressure on staff members to keep the organization safely running.35 This justifies the reason for this result, as nurses perceived moderate crisis leadership behavior collectively with participatory management, resourcefulness, and sense making which are the main determinants of crisis leader. Furthermore, it was evident that crisis leadership was experienced through inclusion of nurses in terms of communication, training, information, solutions, and interactions, making decisions quickly when circumstances change, deploying resources easily to respond to opportunities and threats encountered, and ability to anticipate and prevent risk. From the other side, leaders are lacking to react adequately and to develop adaptive behavior in this situation due to its novelty.

This finding is similar to Martínez-Córcoles36 and Bajaba et al.37 which report moderate level of crisis leadership. Also, Shih et al.38 and Hadley et al.39 found that leaders who lead a crisis effectively have effective communication skills, self-confidence in their capability and enthusiasm to lead in crisis. In addition, Jankelová et al.40 revealed that adequate reaction, effective communication and decision making, self-efficacy and adaptive performance of crisis leaders are key elements of successful crisis leadership. On the contrary, Samuel et al.8 reported a high level of crisis leadership.

From the other side, recent fraud scandals have put ethical leadership behavior high on the priority list of organizations as ethical problems that break down the trust and reputation of both leaders and organizations.13 Several authors clarified that nurses had a moderate perception of ethical leadership.25,41 However, our study represents a high perception of nurses to the role conducted by their leader in relation to fairness, people orientation, power sharing, role clarification, ethical guidance, concern for sustainability and integrity. This can be explained as nurses reported that their leader promotes altruistic attitudes among nurses through role modeling, open communication, clarifying responsibilities, expectations, priorities and performance goals, so nurses become aware of what is expected from them; thus, nurses feel confident in their abilities. This result is similar to Dhahri et al.42 who proved the same result in which the participants were asked to state about the level of leadership during COVID-19 they have in their department from very good to bad. 40 (18.8%) responded as very well, 86 (40.4%) as good, 62 (29.1%) as neutral while 25 (11.7%) as bad. However, this is contradicted by the study conducted by Khalifa and Awad (2018)43 that proved low nurses’ perception of overall ethical leadership behavior represented in its all dimensions.

Kouzes and Posner44 suggest that nurses are influenced by their leader practices, and therefore, behaviors utilized by leaders can make a difference in employee outcomes. In this respect, scholars argue that leaders may empower followers to speak up and engage in morally courageous behaviors. So, the result of this study derived that nurses perceived high moral courage which implied in high perception of the compassion and true presence, commitment to good care, moral responsibility, and moral integrity. Besides, the likely reason for this result could be the sudden occurrence of COVID-19 disease with high spread power and nurses’ sense of responsibility for a useful and constructive presence to save the patient’s lives and keeping humanity in this global crisis. This result goes in the same line with Hakimi et al.,45 Khoshmehr et al.,20 Abdeen and Attia,46 and Taraz et al.47 whose results revealed that nurses enjoy a high level of moral courage. Furthermore, Khodaveisi et al.19 and Donkers et al.’s48 results reported high score of nurses’ moral courage who are caring for patients with COVID-19. On the other hand, Hannah et al.49 valued the moral courage of nurses as moderate and Day50 estimated weak moral courage in nurses.

Of great concern, that nurses in leadership position attempts to identify the work climate that affects the behavior of the nurses and it is clear that ethical work climate is considered to be a significant factor for organization success. In the light of this, our study indicated that nurses’ perceived moderate ethical climate. This can be attributed to moderate perception of social responsibility, friendship, team interest, organizational profit, and self-interest where this moderation required greater improvement. Nevertheless, nurses perceived high perception of the other dimension; efficiency, organizational rules and procedures, personal morality, and laws and professional codes as almost all nurses reported that they have trust and loyalty toward hospital, compliance with the law and professional standards. This is similar to Özden et al.41 and Taraz et al.47 However, Abdeen and Attia46 and Jiang et al.51 revealed that nurses reported high ethical climate during COVID-19. On the other hand, Constantina et al.52 showed that nurses perceived low ethical work climate.

In line with the moderate of studied variables (crisis leadership and ethical climate), high rating of ethical leadership and nurses’ moral courage supporting the main study aim, the most significant finding of this study revealed a strong, positive significant correlation between ethical leadership, crisis leadership, ethical climate, and nurses’ moral courage. The path analysis of structural equation modeling outcome established this correlation and revealed that ethical climate as a mediating factor accounted for 24% of the variance of nurses’ moral courage. This result is supported by Black et al.;53 Simmonds et al.;54 Mohammadi et al.;55 and Kleemola et al.56 whose result proved the good relation between ethical climate and nurses’ moral courage. Ogunfowora et al.29 concluded that leader ethical role influences moral courage by fostering employee moral ownership and a sense of obligation to the organization. Turale et al.57 reported that clear directions, continued support, and strong leadership in crisis of COVID pandemic will positively impact on strong nurses’ moral courage. Moreover, Al Halbusi et al.58 found that ethical leaders are vital components in the development of the ethical climate. On the contrary, Borhani et al.59 found no correlation between ethical climate and nurses’ moral courage.

So, it is interesting that this study creates a great challenges for all leaders to develop their crisis leadership skills especially in the era of pandemic as being able to involve all employees in terms of communication, training, information, solutions, and interactions related to crisis situation, have the ability to handle information, adapting to circumstances as depletion of resources, and develop their abilities to identify warning signs of a looming crisis and bring it to the attention of others. In addition, they need to enhance their ethical leadership competencies of being fair and treat others fairly, allow subordinates to share in making decision, be more independent on themselves, clarifying performance goals and expectations from others, reflect caring behavior of others, imply communication about ethics, explanation of ethical rules, and focus on the development of others. Consequently, these will bring more benefits for their organization, employees, and customers.

Strengths, limitations, and future researches

The results of this study are believed to fill a gap in nursing literature by showing the importance of crisis, ethical leadership, nurses’ moral courage and ethical climate. Also, this study proved the role of ethical climate in promoting and enhancing nurses’ moral courage which may have an impact on their performance. However, this study has some methodological limitations; for instance, nurses’ self-reports for their moral courage, their leader and ethical climate; therefore, the results may suffer from potential biases. Non-random sampling is the second limitation. Also, conducting SEM model requires sufficient sample size where the minimum acceptable number ranged from 100 to 200 based on Wolf et al.60 Finally, a cross-sectional survey and drawing causal explanations is not possible, so we suggest conducting longitudinal studies to better elucidate the causal associations between the study variables as a further study. Another study may be examining the effect of implementing crisis leadership training program for the nurses’ manager on nurses’ moral courage.

Conclusion

In summary, this study provides useful insights into the predicted effects of crisis, ethical leadership in the presence of ethical climate as a mediating factor on nurses’ moral courage. Based on these findings, we confirm the significant effect of crisis, ethical leadership as independent variable, and ethical climate as a mediating factor on enhancing nurses’ moral courage.

Implications to nursing management

This study has important significance for healthcare organizations to provide a supportive ethical climate and develop leader competencies in crisis and ethical leadership to enhance nurses’ moral courage which in turn enhances their performance and brings more benefits for the organization and quality of patients’ care service. Further, organizations should strive to foster effective crisis, ethical leadership practices and support ethical climate to strongly increase nurses’ moral courage which will support them in dealing with the crisis of COVID-19 pandemic. This could be done through carrying out meetings, workshops, and allowing open dialogue with nurses to assess their moral courage. In addition, hospitals should recruit and hire managers who have effective crisis, ethical leadership competencies and design development training program for existing managers. Improve the ethical climate by fostering teamwork, boosting social responsibility, building friendship at work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants who agreed to participate in this research study.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical considerations: Approval was obtained from Ethics Committee at Faculty of Nursing, Alexandria University. The researchers explained the aim of the research to all participants. The privacy and confidentiality of data were maintained and assured by obtaining participants’ informed consent to participate in the research before data collection. The anonymity of participants was granted.

ORCID iD

Nadia H Ali Awad https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8433-6139

References

- 1.Moore C. Nurse leadership during a crisis: ideas to support you and your team. Nurs Times 2020: 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aitamaa E, Leino-Kilpi H, Iltanen S, et al. Ethical problems in nursing management: The views of nurse managers. Nurs Ethics 2016; 23(6): 646–658. DOI: 10.1177/0969733015579309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mansur J, Sobral F, Islam G. Leading with moral courage: The interplay of guilt and courage on perceived ethical leadership and group organizational citizenship behaviors. Business Ethics A Eur Rev 2020; 29(3): 587–601. DOI: 10.1111/beer.12270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh Y, Gastmans C. Moral distress experienced by nurses: a quantitative literature review. Nurs Ethics 2015; 22(1): 15–31. DOI: 10.1177/0969733013502803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awad N, Ashour H. The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence, Moral distress and Work Engagement as perceived by critical care Nurses. Int J Adv Nurs Manag 2020; 8(3): 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang N, Li J, Bu X, et al. The relationship between ethical climate and nursing service behavior in public and private hospitals: a cross-sectional study in China. BMC Nursing 2021; 20(1): 1–10. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-021-00655-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bandura A.. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Review 1977; 48(2): 191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samuel P, Griffin M, White M, et al. Crisis leadership efficacy of nurse practitioners. J Nurse Pract 2015; 11(9): 862–868. DOI: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2015.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen T. Crisis Leadership: A Study of Leadership Practice. Doctoral Dissertation. School of Business & TechnologyCapella University, 2009. Available at, https://www.proquest.com/openview/b8d8cec7483d9ef5f971d90fc9542a1a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonvillian G.. Turnaround managers as crisis leaders. In: Dubrin A. (ed). Handbook of research on crisis leadership in organization. MA: Edward Elgar, pp. 92–109. North-ampton 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brownlee-Turgeon J. Measuring a leader’s ability to identify and avert crisis. J Manag Sci Business Intelligence 2017; 2(2): 9–16. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.827384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown M, Treviño L, Harrison D. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior Human Decision Processes 2005; 97(2): 117–134. DOI: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalshoven K, Den Hartog D, De Hoogh A. Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. Leadership Quarterly 2011; 22(1): 51–69. DOI: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.12.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Treviño L, Brown M, Hartman P. A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Hum Relations 2003; 56(1): 5–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouma C. Ethical Leadership and Organizational Culture: Literature Perspective. Int J Innovative Res Dev 2017; 6(8): 230–241. DOI: 10.24940/ijird/2017/v6/i8/AUG17099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Indeed Editorial Team . Crisis Leadership: Definition and 6 Essential Components 2021, https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/crisis-leadership [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu Q, Tang T, Jiang W. Does moral leadership enhance employee creativity? Employee identification with leader and leader–member exchange (LMX) in the Chinese context. J Business Ethics 2015; 126(3): 513–529. DOI: 10.1007/s10551-013-1967-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray J.. Moral Courage in Healthcare: Acting Ethically Even in the Presence of Risk. OJIN: Online J Issues Nurs 2010; 15(3). DOI: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No03Man02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khodaveisi M, Oshvandi K, Bashirian S, et al. Moral courage, moral sensitivity and safe nursing care in nurses caring of patients with COVID-19. Nurs Open 2021. DOI: 10.1002/nop2.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khoshmehr Z, Barkhordari-Sharifabad M, Nasiriani K, et al. Moral courage and psychological empowerment among nurses. BMC Nursing 2020; 19: 1–7. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-020-00435-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Numminen O, Katajisto J, Leino-Kilpi H. Development and validation of nurses’ moral courage scale. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26(7–8): 2438–2455. DOI: 10.1177/0969733018791325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman A, Round H, Bhattacharya S, et al. Ethical climates in organizations: A review and research agenda. Business Ethics Q 2017; 27(4): 475–512. DOI: 10.1017/beq.2017.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghorbani A, Hesamzadeh A, Khademloo M, et al. Public and private hospital nurses’ perceptions of the ethical climate in their work settings, Sari City, 2011. Nurs Midwifery Studies 2014; 3(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cullen J, Victor B, Bronson J. The ethical climate questionnaire: An assessment of its development and validity. Psychol Reports 1993; 73(2): 667–674. DOI: 10.2466/pr0.1993.73.2.667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elsayed B, Awad N, El Bialy G. The Relationship between Nurses' Perception of Ethical Leadership and Anti-Social Behavior through Ethical Climate as a Mediating Factor. Int J Novel Res Healthc Nurs 2020; 7(2): 471–484. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asad H, Naseem R, Faiz R. Mediating effect of ethical climate between organizational virtuousness and job satisfaction. Pakistan J Commerce Social Sci (PJCSS) 2017; 11(1): 35–48. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/188280 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramos R, Mata R, Nacar R. Mediating effect of ethical climate on the relationship of personality types and employees mindfulness. Linguistics Cult Rev 2021; 5(S1): 1480–1494. DOI: 10.21744/lingcure.v5nS1.1722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albejaidi F. The mediating role of ethical climate between organizational justice and stress: A CB-SEM analysis. Amazonia Investiga 2021; 10(38): 82–96. DOI: 10.34069/AI/2021.38.02.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogunfowora B, Maerz A, Varty C. How do leaders foster morally courageous behavior in employees? Leader role modeling, moral ownership, and felt obligation. J Organizational Behav 2021; 42(4): 483–503. DOI: 10.1002/job.2508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keselman D, Saxe-Braithwaite M. Authentic and ethical leadership during a crisis. Healthc Manage Forum 2020; 34: 1–4. DOI: 10.1177/0840470420973051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ethical responsibilities of healthcare leadership, Disaster Preparedness State Expert Panel on Ethics for Disaster Planning Wisconsin Hospital Association. Published January 2020. Available at:https://disasterinfo.nlm.nih.gov/ethics. Accessed June 15, 2020.

- 32.American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE) . Principles & elements of a healthful practice/work environment 2004. At:, http://www.aone.org/aone/pdf/PrinciplesandElementsHealthfulWorkPractice.pdf

- 33.McDonald R, Ho M. Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods 2002; 7(1): 64–82. DOI: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hair J, Black W, Babin B, et al. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed.. Essex: UKPearson New International EditionPearson Education Limited, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freysteinson W, Celia T, Gilroy H, et al. The experience of nursing leadership in a crisis: A hermeneutic phenomenological study. J Nurs Manag 2021. 29, 1535, 1543, DOI: 10.1111/jonm.13310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martínez-Córcoles M. High reliability leadership: A conceptual framework. J Contingencies Crisis Manag 2018; 26: 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bajaba A, Bajaba S, Algarni M, et al. Adaptive managers as emerging leaders during the COVID-19 crisis. Front Psychol 2021; 12:1062.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shih F, Turale S, Lin Y, et al. Surviving a life-threatening crisis: Taiwan’s nurse leaders’ reflections and difficulties fighting the SARS epidemic. J Clin Nurs 2009; 18(24): 3391–3400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hadley C, Pittinsky T, Sommer S, et al. Measuring the efficacy of leaders to assess information and make decisions in a crisis: the C-LEAD scale. Leadersh Q 2011; 22(4): 633–648. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jankelová N, Joniaková Z, Blštáková J, et al. Leading Employees Through the Crises: Key Competences of Crises Management in Healthcare Facilities in Coronavirus Pandemic. Risk Manag Healthcare Pol 2021; 14: 561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Özden D, Arslan G, Ertuğrul B, et al. The effect of nurses’ ethical leadership and ethical climate perceptions on job satisfaction. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26(4): 1211–1225. DOI: 10.1177/0969733017736924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dhahri A, Rehman U, Ali S, et al. Leadership Perception during COVID-19 Pandemic: The Critical Criticism on Surgical Leadership. SciMedicine J 2021; 3(3): 250–256. DOI: 10.28991/SciMedJ-2021-0303-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khalifa S, Awad N. The relationship between organizational justice and citizenship behavior as perceived by medical-surgical care nurses. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci 2018; 7(4): 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kouzes J, Posner B. The Leadership Challenge. 3rd edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hakimi H, Mousazadeh N, Nia H, et al. The relationship between moral courage and the perception of ethical climate in nurses. Res Square, 2020. DOI: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-41565/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abdeen A, Attia NM. Ethical work climate, moral courage, moral distress and organizational citizenship behavior among nurses. Int J Nurs Edu 2020; 12(3): . [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taraz Z, Loghmani L, Abbaszadeh A, et al. The relationship between ethical climate of hospital and moral courage of nursing staff. Electron J Gen Med 2019; 16(2). DOI: 10.29333/ejgm/93472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Donkers M, Gilissen V, Candel M, et al. Moral distress and ethical climate in intensive care medicine during COVID-19: a nationwide study. BMC Medical Ethics 2021; 22(1): 1–12. DOI: 10.1186/s12910-021-00641-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hannah S, Avolio B, Walumbwa F. Relationships between authentic leadership, moral courage, and ethical and pro-social behaviors. Business Ethics Q 2011; 21(4): 555–578. DOI: 10.5840/beq201121436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Day L.. Courage as a virtue necessary to good nursing practice. Am J Crit Care 2007; 16(6): 613–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang W, Zhao X, Jiang J, et al. The association between perceived hospital ethical climate and self-evaluated care quality for COVID-19 patients: the mediating role of ethical sensitivity among Chinese anti-pandemic nurses. BMC Med Ethics 2021; 22(1): 1–10. DOI: 10.1186/s12910-021-00713-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Constantina C, Papastavrou E, Charalambous A. Cancer nurses’ perceptions of ethical climate in Greece and Cyprus. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26(6): 1805–1821. DOI: 10.1177/0969733018769358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Black S, Curzio J, Terry L. Failing a student nurse: A new horizon of moral courage. Nurs Ethics 2014; 21(2): 224–238. DOI: 10.1177/0969733013495224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Simmonds A, Peter E, Hodnett E, et al. Understanding the moral nature of intrapartum nursing. J Obstetric, Gynecologic Neonatal Nursing 2013; 42(2): 148–156. DOI: 10.1111/1552-6909.12016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mohammadi S, Borhani F, Roshanzadeh M. Relationship between moral distress and moral courage in nurses. Iranian J Med Ethics Hist Med 2014; 7(3): . [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kleemola E, Leino-Kilpi H, Numminen O. Care situations demanding moral courage: content analysis of nurses’ experiences. Nurs Ethics 2020; 27(3): 714–725. DOI: 10.1177/0969733019897780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turale S, Meechamnan C, Kunaviktikul W. Challenging times: ethics, nursing and the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int Nursing Review 2020; 67(2): 164–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Al Halbusi H, Williams A, Ramayah T, et al. Linking ethical leadership and ethical climate to employees' ethical behavior: the moderating role of person–organization fit. Personnel Rev 202050, 159, 185. DOI: 10.1108/PR-09-2019-0522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A, Bahrampour A, et al. Investigating the relationship between the ethical atmosphere of the hospital and the ethical behavior of Iranian nurses. J Edu Health Promot 2021; 10(1): 193. DOI: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_891_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wolf E, Harrington K, Clark S, et al. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ Psychological Measurement 2013; 73(6): 913–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]