Abstract

Kocuria is an anaerobic, Gram-positive bacterium, which has been rarely reported to cause endophthalmitis following cataract surgery, intravitreal injections, penetrating ocular trauma, and also secondary to endogenous sources. Visual prognosis is often guarded, with no previous cases reporting a final visual acuity better than 20/60. We describe a young female patient who developed culture-proven Kocuria kristinae endophthalmitis associated with a traumatic scleral rupture. Visual acuity at 2 months of follow-up improved from light perception to 20/50 after treatment with intravitreal antimicrobial therapy and pars plana vitrectomy.

Keywords: Kocuria, Kocuria kristinae, Endophthalmitis, Intravitreal antimicrobials, Ocular trauma, Pars plana vitrectomy

Introduction

Kocuria species, a member of the Micrococcaceae family, is an anaerobic, coagulase-negative bacterium. Gram staining demonstrates Gram-positive cocci in tetrads which grow as cream-colored colonies on blood agar [1]. This organism is under-recognized, as it shares similar characteristics with Actinobacteria and is often misdiagnosed as Staphylococcus as a result of insensitive assays to identify the organism [2]. Kocuria is present in normal human skin and mucosal flora, but has been implicated in pathogenic conditions, including endocarditis, peritonitis, catheter-related infections, cholecystitis, peritonitis, and pneumonitis [1, 3, 4]. To date, only three previous reports of Kocuria-related endophthalmitis have been published, and none of these patients had a final visual acuity (VA) better than 20/100 [2, 4, 5]. We herein describe a case of a young woman with post-traumatic Kocuria endophthalmitis (KE) with an excellent clinical outcome.

Case Report

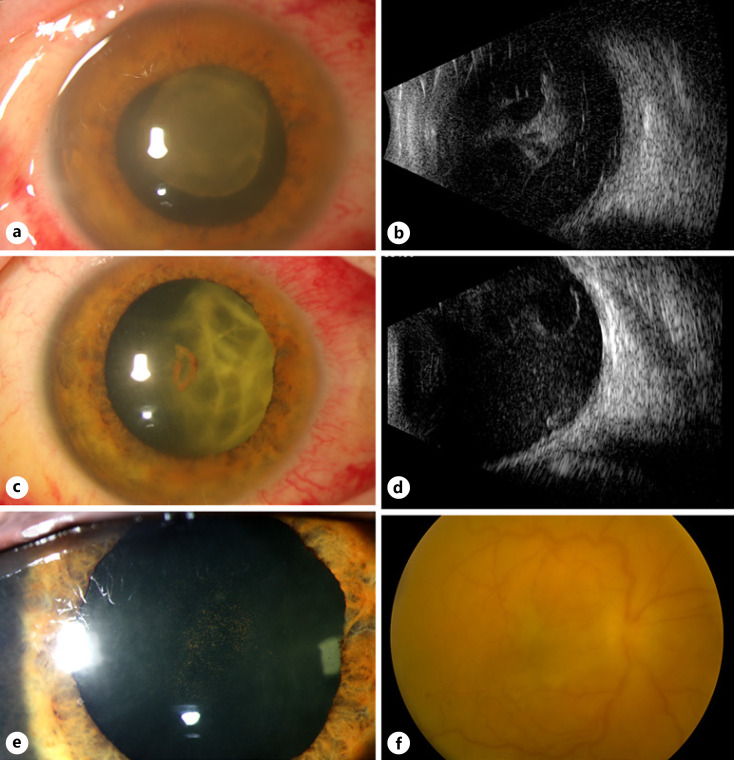

A 26-year-old healthy female who works at a wildlife facility presented to the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute emergency room after suffering ocular trauma by a blue heron bird beak 24 h earlier. The patient was referred from an outside hospital with concern of ruptured globe based on computerized tomography scan, which described an irregular contour of the globe. Her presenting corrected VA was 20/70 in the right eye (OD) and 20/20 in the left eye (OS). Intraocular pressures were 11 OD and 9 OS. A comprehensive exam OS was normal. Slit lamp examination of the right eye showed a small upper eyelid laceration, subconjunctival hemorrhage, 2+ cells, fibrin, and a small hyphema in the anterior chamber, but the lens was clear. Dilated fundus examination showed temporal commotio retinae but no evidence of a penetrating injury or intraocular foreign body. Two weeks later, she returned with sudden-onset vision loss and eye pain OD. VA was light perception (LP), and intraocular pressure was 14 OD. There were 3+ cells and a fibrinous membrane in the anterior chamber obscuring the view of the lens and fundus (Fig. 1a). B-scan ultrasound demonstrated dense vitreous opacities and membranes (Fig. 1b). It was unclear whether these dense vitreous opacities were vitreous hemorrhage or infectious in nature. Therefore, patient underwent vitreous aspiration rather than pars plana vitrectomy (PPV).

Fig. 1.

A 26-year-old female present with KE of the right eye. a Slit lamp photograph at presentation demonstrated a dense fibrin plaque on the posterior surface of the crystalline lens. b Corresponding B-scan ultrasonography showed dense vitreous opacities and membrane formation. c One week after intravitreal vancomycin (1 mg/0.1 mL), ceftazidime (2.25 mg/0.1 mL), and amphotericin (5 μg/0.1 mL). The fibrin plaque contracted. d The corresponding B-scan ultrasound demonstrated persistent vitreous opacities with resolving posterior membranes. e Slit lamp photograph 3 days after PPV showed resolution of anterior chamber media was clear. f Corresponding fundus photograph of the right eye (Topcon, Topcon Healthcare, Oakland, NJ, USA) showed persistent vitreous haze, but the retina was attached.

The patient underwent vitreous aspiration and injection of intravitreal vancomycin (1 mg/0.1 mL), ceftazidime (2.25 mg/0.1 mL), and amphotericin (5 μg/0.1 mL). Vitreous cultures were positive for pansensitive Kocuria kristinae. One week later, the fibrinous membrane was resolving and VA improved to counting fingers, but there were persistent dense vitreous opacities and no view to the retina (Fig. 1c, d). A 25-gauge PPV was performed to remove the vitreous opacities obscuring the vision. No evidence of any prior posterior rupture was seen intraoperatively. At postoperative day three, VA improved to 20/200, with significant reduction in anterior cell reaction, reduced fibrinous membranes, and reduced vitritis (Fig. 1e, f). At 2 months after the initial presentation, the VA was 20/50 in the right eye, with progressive nuclear sclerosis limiting vision. There was further reduction of anterior inflammation and vitritis, and there was a normal retinal examination at this time. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Discussion

KE is a rare but emerging cause of endophthalmitis. It was first described by Duan et al. [2], who reported KE in 1 out of 330 cases in their retrospective study. Clinical presentation can be delayed, ranging from 1 to 30 days from the inciting event [2, 4, 5]. Table 1 summarizes all published cases of KE in the literature, to date. Kocuria has been identified on intravitreal needles and ocular surfaces despite sterilization of the conjunctival surface [6]. Post-intravitreal KE by culture-positive K. kristinae presenting 5 days after intravitreal bevacizumab was described by Alles et al. [5]. Our patient had trauma 2 weeks prior to the diagnosis of endophthalmitis. While there was no clinical sign of a penetrating wound, there may have been an occult open globe injury. Dave et al. [4] in 2018 described 8 eyes affected by KE. Similar to our patient, 5 of the 8 cases were post-traumatic in etiology, 3 of which were classified as K. kristinae.

Table 1.

Summary of the published cases reporting KE

| Study | Organism identified | Cause | Presentation features | Pre-treatment VA | BCVA at last follow-up | Treatment | Presumed anatomic success* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duan et al. [2] | K. kristinae | Trauma | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Dave et al. [4] | K. kristinae | Trauma | Hypopyon | 20/60 | Intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime | Yes | |

| K. kristinae | Trauma | Hypopyon | LPa | 20/60 | Intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime | Yes | |

| K. kristinae | Trauma | Hypopyon, corneal edema | LP | HM | PPVb/PPLc/intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime | No | |

| K. varions | Keratitis | Corneal edema | HMd | HM | Intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime, adhesive tissue application | Yes | |

| K. rosea | Trauma | Cataract | 20/400 | 20/2,400 | Intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime | Yes | |

| K. rosea | Trauma | Hypopyon | LP | HM | PPV/PPL/intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime | No | |

| K. rosea | Endogenous | Hypopyon, corneal edema | LP | HM | PPV/PPL/intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime | Yes | |

| K. rosea | Postoperative | Corneal edema, inflammation | CFe | 20/80 | PPV, intravitreal vancomycin, and ceftazidime | Yes | |

| Alles et al. [5] | K. kristinae | Post-intravitreal injection | Hypopyon, vitritis | N/A | N/A | PPV/intravitreal vancomycin, ceftazidime, and moxifloxacin, then PPV | Yes |

| Present study | K. kristinae | Trauma | Fibrin, vitritis inflammation | LP | 20/50 | Intravitreal vancomycin and ceftazidime, then PPV | Yes |

LP, light perception.

PPV, pars plana vitrectomy.

PPL, pars plana lensectomy.

HM, hand motions.

CF, counting fingers.

Anatomic success was defined preserved globe, absence of hypotony, retinal attachment, and absence of active inflammation.

In our internal review of over 250 endophthalmitis isolates at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute from 2014 to 2020, we were only able to identify this 1 case of KE. Phenotypic assays used for Kocuria may often misidentify it as coagulase-negative Staphylococci [7]. Most clinical microbiology laboratories have limited access to advanced molecular techniques for precise identification, especially given its similarities to Staphylococcus and Micrococcus species [8, 9]. In addition, Kocuria may have a variable phenotypic behavior in vitro, especially under stress conditions [8]. Isolates were identified using an automated ID system (Vitek2; BioMerieux, Raleigh, NC, USA). Advanced techniques would involve using polymerase chain reaction and 16S analyses to confirm bacteria and then sequencing and/or polymerase chain reaction with Kocuria-specific primers.

Despite reported resistance to furazolidone and bacitracin, Kocuria has a generally favorable susceptibility pattern and can be treated with antibiotics such as vancomycin, moxifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and cefuroxime (Table 1) [2, 3, 4, 5]. The literature shows few Kocuria cases with resistance to amikacin and cefazolin [4]. Our clinical case was pansensitive to antimicrobials and thus had a good response to intravitreal antimicrobials at presentation. A lens-sparing PPV was effective in removing vision-obscuring vitreous opacities following resolution of KE. Dave and colleagues [4] described complete resolution of KE in 75% of the cases. However, final VA of 20/100 or better was achieved only in 38% of patients. Our case improved from LP to 20/50 in only 2 months, which is the best visual outcome reported in the literature to date following KE.

In conclusion, differentiating Kocuria from other similar organisms can help guide treatment, as KE generally responds well to standard empiric antibiotics [10]. A clinical suspicion for KE should be present in cases of endophthalmitis occurring within 1 month from a clinical history suspicious for ocular trauma.

Statement of Ethics

This case report was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The evaluation of all protected patient health information was performed in a manner compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to performing the procedure, including permission for publication of the images included herein. The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. The study protocol was reviewed, and the need for approval was waived by the University of Miami/Bascom Palmer Ethics Committee.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Fundus was supported by the NIH Core Grant P30EY014801, Research to Prevent Blindness Unrestricted Grant.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the ICMJE criteria including substantial contributions to the conception of the work, drafting the work critically, final approval of the version to be published, and agreement to be accountable to all aspects of the work regarding accuracy and integrity of the manuscript. Harry W. Flynn, Jr. is the corresponding author.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgment

Department of Photography at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, FL, USA.

References

- 1.Dunn R, Bares S, David MZ. Central venous catheter-related bacteremia caused by Kocuria kristinae: case report and review of the literature. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2011;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duan F, Wu K, Liao J, Zheng Y, Yuan Z, Tan J, et al. Causative microorganisms of infectious endophthalmitis: a 5-year Retrospective Study. J Ophthalmol. 2016;2016:6764192. doi: 10.1155/2016/6764192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savini V, Catavitello C, Masciarelli G, Astolfi D, Balbinot A, Bianco A, et al. Drug sensitivity and clinical impact of members of the genus Kocuria. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59((Pt 12)):1395–402. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.021709-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dave VP, Joseph J, Pathengay A, Pappuru RR. Clinical presentations, management outcomes, and diagnostic dilemma in Kocuria endophthalmitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2018;8((1)):21. doi: 10.1186/s12348-018-0163-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alles M, Wariyapola D, Salvin K, Jayatilleke K. Endophthalmitis caused by Kocuria kristinae: a case report. Sri Lankan J Infect Dis. 2020;10((2)):146–49. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ozkan J, Coroneo M, Sandbach J, Subedi D, Willcox M, Thomas T. Bacterial contamination of intravitreal needles by the ocular surface microbiome. Ocul Surf. 2021;19:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2020.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Ami R, Navon-Venezia S, Schwartz D, Carmeli Y. Infection of a ventriculoatrial shunt with phenotypically variable Staphylococcus epidermidis masquerading as polymicrobial bacteremia due to various coagulase-negative Staphylococci and Kocuria varians. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41((6)):2444–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2444-2447.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Ami R, Navon-Venezia S, Schwartz D, Schlezinger Y, Mekuzas Y, Carmeli Y. Erroneous reporting of coagulase-negative Staphylococci as Kocuria spp. by the Vitek 2 system. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43((3)):1448–50. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.3.1448-1450.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savini V, Catavitello C, Bianco A, Balbinot A, D'Antonio D. Epidemiology, pathogenicity and emerging resistances in Staphylococcus pasteuri: from mammals and lampreys, to man. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2009;4((2)):123–9. doi: 10.2174/157489109788490352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forster RK. The endophthalmitis vitrectomy study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113((12)):1555–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100120085015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.