Abstract

Acne vulgaris is one of the most frequent skin diseases worldwide, triggered by multiple endogenous and exogenous factors. Hormones, particularly growth hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factor-1, insulin, CRH, and glucocorticoids, play a major role in the pathogenesis and exacerbation of acne. Excess GH seen in acromegalic patients may result in increased size and function of sweat glands and sebaceous glands, which may contribute to the patient's worsening acne and interfere with dermatologic treatment. Therefore, understanding the pathogenesis of acne will help in treating resistant acne by diagnosing and treating the underlying etiology using multidisciplinary treatment.

Keywords: Acromegaly, Acne vulgaris, Resistant acne

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is an incredibly common disorder of the sebaceous follicles that is precipitated by follicular and epidermal hyperkeratinization, inflammation, and active commensal bacteria Propionibacterium acne. Excess sebum production is one of the pathogenic factors regulated by hormonal effects. To successfully treat this skin disease with a rational therapy, a deep knowledge of the pathogenesis of acne is required [1].

Acromegaly is a disorder that results from excess growth hormone (GH) production, typically by the pituitary gland, that affects about 6 per 100,000 people [2]. GH stimulates the synthesis of collagen and glycosaminoglycan in the skin and bones, leading to insidious hypertrophy of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and viscera along with periosteal overgrowth. GH also causes an increase in the size and function of sweat and sebaceous glands, as seen in acromegaly, which results in an offensive odor and exacerbation of acne [3]. We present a case of acromegaly in a young Bahraini male who was diagnosed by a dermatologist because of his severe resistant acne to isotretinoin.

Case Report/Case Presentation

A 34-year old Bahraini male with sickle cell trait and type 2 diabetes mellitus on oral hypoglycemic agents (metformin and gliclazide) presented to our dermatology clinic with severe nodulocystic acne. He had been treated by a dermatologist for his severe acne for over 10 years and had undergone multiple treatment regimens, including topical antibiotics, multiple courses of oral antibiotics, multiple courses of high-dose isotretinoin, and surgical intervention, such as comedonal extraction. He continued to have numerous acne lesions despite receiving isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/day for 9 months.

On physical examination, he presented with frontal bossing, prognathism, thick eyelids, a large triangular nose, a thickened lower lip, and macroglossia (shown in Fig. 1). He was also noted to have a barrel chest and large, wide hands and feet. Dermatological examination revealed multiple inflammatory papules, tender nodules, and grouped, polyporous comedones as well as multiple extensive, depressed scars localized predominantly on his face and back (Fig. 2). In addition, he had oily skin, mild skin puffiness, numerous dilated pores, and seborrhea. Based on these findings, he was referred to an endocrinologist on the suspicion of acromegaly.

Fig. 1.

Features of acromegaly on the face including frontal bossing, prognathism, thick eyelids, large triangular nose, and thickened lower lip.

Fig. 2.

Multiple inflammatory papules, tender nodules, and grouped, polyporous comedones as well as multiple scars on the back and chest.

Laboratory analysis showed increased GH (>40 ng/mL) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (1,529 μg/L; normal 116–352 μg/L) levels. FSH, LH, prolactin, testosterone, cortisol, ACTH, TSH, and free T4 levels were all within normal ranges (shown in Table 1). Magnetic resonance imaging was requested to rule out a pituitary adenoma, but the patient refused due to claustrophobia. He had been lost to follow-up for more than 6 months when he presented to the emergency department with severe headache, fever, altered mental status, and photophobia. A CT brain and lumbar puncture excluded meningitis. Repeated laboratory investigations showed panhypopituitarism with decreases in all hormonal parameters, including GH and IGF-1 levels (Table 1). Brain magnetic resonance imaging done under general anesthesia showed a large sellar lesion with significant intrasphenoidal and, to a lesser extent, suprasellar extension with heterogeneous peripheral enhancement and central necrosis. This process resulted in sellar enlargement, which suggested a longstanding process that was suggestive of pituitary apoplexy (Fig. 3). Currently, the patient is suffering from panhypopituitarism and is on hormonal replacement by an endocrinologist. The patient's acne has improved markedly after the decrease in his GH and IGF-1 levels. He continues to suffer from residual acne scars. He was referred to ophthalmology and neurosurgery for further management and multidisciplinary treatment.

Table 1.

Laboratory values of patient on initial and repeat (6 months) testing

| Test | Result A | Result B after 6 months | Unit | Ref. range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBS | 7.4 | 3.6 | mmol/L | 3.6–5.8 |

| FSH | 5.3 | 0.8 | IU/L | 1.6–11.0 |

| LH | 0.3 | 0.3 | IU/L | 0.8–6.0 |

| Testosterone | 13.4 | 0.2 | nmol/L | 9.1–40.0 |

| IGF-1 | 1,529 | 286 | µg/L | 116–352 |

| GH | >40 | 0.4 | µg/L | |

| Prolactin | 11.4 | 1.76 | ng/L | 3.9–29.5 |

| TSH | 1.5 | 0.24 | mlU/L | 0.25–5.0 |

| Free T4 | 22.7 | 9.8 | pmol/L | 6.0–24.5 |

| Cortisol @ 8:00 a. | m. 653 | 53 | nmol/L | 190–690 |

| ACTH | 9.7 | 1.4 | pmol/L | <10 |

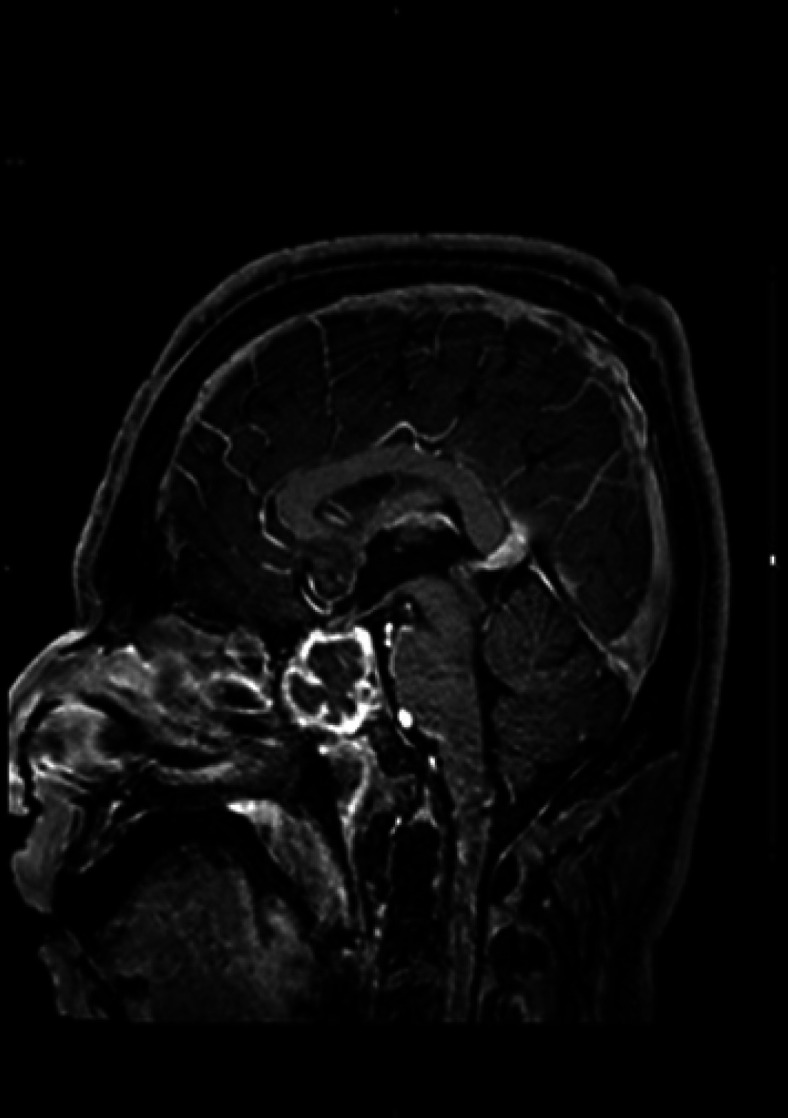

Fig. 3.

A large sellar lesion showing significant intrasphenoidal and, to a lesser extent, suprasellar extension with heterogeneous peripheral enhancement and central necrosis.

Discussion

Acromegaly is a hormonal disorder that results from excessive GH production in the body. A benign tumor of the pituitary gland called an adenoma causes overproduction of GH, which is responsible for about 98% of the cases of acromegaly [4]. It is a rare disorder that is associated with higher mortality and morbidity, most likely due to its slow, “sneaky” onset and various manifestations [5]. Patients may present with osteoarticular, cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrinological, and cutaneous manifestations that may go unrecognized for many years. Around 40% of acromegalic patients are diagnosed by internists, ophthalmologists if they have visual disturbances, dentists due to maxillary teeth separation, mandibular prognathism, and overbite, gynecologists due to menstrual irregularities and infertility, rheumatologists if they suffer from joint problems, or pulmonologists if they have obstructive sleep apnea [6]. This motivates us to report our case, which was a case of acromegaly diagnosed by a dermatologist because of his severe acne resistant to isotretinoin treatment.

Cutaneous manifestations of acromegaly include pigmented skin tags, acanthosis nigricans, and cutaneous microcirculation alteration [7]. In addition, excess GH may change the size and function of the sweat glands and sebaceous glands, as seen in acromegaly, which results in an offensive odor, hyperhidrosis, oily skin, and an exacerbation of acne [3, 7]. Marked cystic acne has been noted among people with acromegaly in reports by the FDA on 9 patients with the condition [8].

Acne vulgaris is an incredibly common condition with multiple contributory endogenous and exogenous factors in its pathogenesis. Acne can be a common feature in numerous systemic diseases (shown in Table 2) [9]. Acromegaly is an endocrine disorder in which hormones trigger sebum production and sebaceous growth and differentiation. An increased rate of acne development is associated with excessive hormone production, specifically androgens, GH, IGF-1, insulin, CRH, and glucocorticoids [10]. Basic therapeutic interventions for acne include topical therapy, systemic antibiotics, hormonal agents, isotretinoin, and physical treatments. Generally, the severity of acne lesions determines the type of acne treatment. However, knowing the complex multifactorial systemic disease that is associated with acne may give us a clue as to how to treat our patients with severe and recalcitrant acne, outside of basic therapeutic interventions. An improved understanding of the pathogenesis of acne can lead to a rational therapy that is successful in treating this skin disease [1]. Unfortunately, as our patient was lost for follow-up because of his claustrophobia, he eventually went on to develop pituitary apoplexy. Eighty percent of people develop hypopituitarism after pituitary apoplexy, most commonly due to GH deficiency, and require some form of hormone replacement therapy for treatment [11, 12]. Studies confirm that GH disorders, either directly or via IGF-I, may have both a structural and functional effect on human skin and its appendages [13]. Thus, in patients with acromegaly, acne can be a presenting symptom and should be the etiology that is targeted to effectively treat the skin condition.

Table 2.

Systemic diseases that present with acne

| Endocrine diseases | Nonendocrine diseases |

|---|---|

| Polycystic ovary disease | Apert syndrome |

| Cushing syndrome | Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis |

| Hyperandrogenemia, insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans | Osteitis syndrome |

| Seborrhea, acne, hirsutism, androgenetic alopecia | Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum |

| Congenital adrenal hyperplasia | |

| Late onset adrenal hyperplasia | |

| Androgen-secreting tumors | |

| Acromegaly | |

| Metabolic syndrome |

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images. Ethical approval was not required for this study in accordance with local/national guidelines.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. Fatema Abdulwahab Khamdan, Milaan A. Shah, Dr. Maryam Ahmed Khamdan, and Dr. Eman Albasri have no conflicts to disclose.

Funding Sources

No funding was utilized/provided for this report.

Author Contributions

Fatema Abdulwahab Khamdan, Milaan A. Shah, Maryam Ahmed Khamdan, and Eman Albasri contributed to the writing of all sections and components of the report.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author, Fatema Abdulwahab Khamdan.

References

- 1.Toyoda M, Morohashi M. Pathogenesis of acne. Med Electron Microsc. 2001 Mar;34((1)):29–40. doi: 10.1007/s007950100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Shlomo A, Melmed S. Acromegaly. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37((1)):101–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leonhardt JM, Heymann WR. Cutaneous manifestations of other endocrine diseases. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. p. p. 1669. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 19th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holdaway IM, Rajasoorya RC, Gamble GD. Factors influencing mortality in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89((2)):667–74. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drange MR, Fram NR, Herman-Bonert V, Melmed S. Pituitary tumor registry: a novel clinical resource. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85((1)):168–74. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.1.6309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Shlomo A, Melmed S. Skin manifestations in acromegaly. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24((4)):256–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.eHealthMe Acromegaly and cystic acne. [cited 2019 Apr 2]. Available from: https://www.ehealthme.com/cs/acromegaly/acne/

- 9.Kaur S, Verma P, Sangwan A, Dayal S, Jain VK. Etiopathogenesis and therapeutic approach to adult onset acne. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61((4)):403–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.185703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lolis MS, Bowe WP, Shalita AR. Acne and systemic disease. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93((6)):1161–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajasekaran S, Vanderpump M, Baldeweg S, Drake W, Reddy N, Lanyon M, et al. UK guidelines for the management of pituitary apoplexy. Clin Endocrinol. 2011;74((1)):9–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nawar RN, AbdelMannan D, Selman WR, Arafah BM. Pituitary tumor apoplexy: a review. J Intensive Care Med. 2008;23((2)):75–90. doi: 10.1177/0885066607312992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lange M, Thulesen J, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Skakkebaek NE, Vahl N, Jørgensen JO, et al. Skin morphological changes in growth hormone deficiency and acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;145((2)):147–53. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1450147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author, Fatema Abdulwahab Khamdan.