Abstract

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) has become associated with prothrombotic state that could lead to severe arterial thrombotic complications. In the case of severe COVID-19 infection, hepatic dysfunction has been observed in more than 50% of patients. In this article, we present a case of aortic thrombosis associated with COVID-19 infection and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphism (C677T) treated with rivaroxaban resulting in acute liver failure with fatal outcome.

Keywords: Acute liver failure, Rivaroxaban, COVID-19, Arterial thrombosis, Thrombophilia

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), a viral respiratory illness caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) that can cause a prothrombotic state due to excessive inflammation, platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, and stasis [1]. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor abundantly present in alveolar cells acts as a functional cell receptor by binding to the spike protein of the viral capsid. Studies have shown that ACE2 is expressed not only in lungs but also in other extrapulmonary organs like the liver [2].

Even healthy individuals contracted with COVID-19 infection are at risk of incident cardiovascular complications. However, majority of patients with severe arterial thrombosis associated with COVID-19 infection have had a history of cardiovascular diseases, usually interplayed with risk factors such as arterial hypertension, male sex, smoking, and diabetes [3, 4, 5].

An aortic thrombus is an uncommon condition even in hypercoagulability states including sepsis, polycythemia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, autoimmune diseases, pregnancy, and cancer. Aortic thrombosis is also an uncommon cause of peripheral arterial embolization. Floating aortic thrombus has been reported in at least three confirmed cases with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection despite low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) prophylaxis [6].

Kashi et al. [7] reported 7 cases of severe arterial thrombotic events in patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection despite the use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy. All patients had a history of cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, homozygous factor V Leiden mutation was noted in one patient.

Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene polymorphism (C677T) is a well-recognized genetic risk factor for venous thrombosis and it has been suggested that polymorphism could increase the risk of arterial thrombosis [8]. Liver damage has been described in more than 50% of patients with COVID-19, this is especially true in severe cases. Patients with acute liver injury (ALI) are also associated with higher mortality. Liver damage could be related to the direct viral infection, a systemic dysfunctional immune reaction such as the cytokine storm, sepsis, or drug-induced liver injury (DILI) [2].

In a recently published retrospective study, rivaroxaban was the only direct oral anticoagulant associated with DILI [9]. According to a French nationwide cohort study, ALI was more common in new users of rivaroxaban compared to users of vitamin K antagonists among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. However, no increased risk was observed for new users of apixaban and dabigatran [10]. According to the available data, there has been only one case of fatal acute liver failure induced by rivaroxaban described in literature since the drug's availability in 2008 [11, 12, 13, 14].

Case Presentation

A 60-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency unit due to pain, paresthesia, and coolness of the right lower leg and foot during the previous 48 hours. She was previously healthy, presenting only with cesarean section in her past medical history, without any previous thromboembolic events. Upon admission to the hospital, the toes of her right foot were cold with capillary filling lasting more than 5 s with absent distal pulses in both legs.

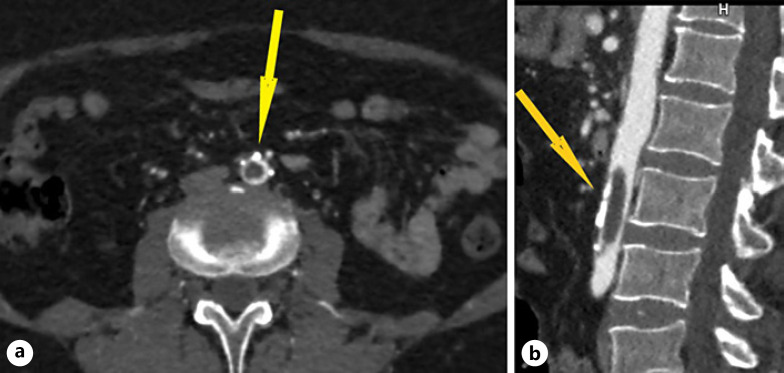

Computed tomography angiography of the aorta and lower limbs revealed a floating thrombus in the abdominal aorta (length 3.8 cm, width 0.9 cm) with minimal marginal flow and iliac arteries of regular lumen width with marginal atherosclerotic plaques (Fig. 1). Computed tomography angiography confirmed thromboembolism of the entire right deep femoral artery as well as in distal part of the left deep femoral artery. Furthermore, both superficial femoral arteries had a sustained flow. Third segment of the right popliteal artery was occluded with thromboembolus, spreading to the posterior tibial artery with marginal recanalization.

Fig. 1.

a MSCT angiography of the aorta demonstrates an aortic thromboembolism (yellow arrow)- axial plane. b MSCT angiography of the aorta demonstrates an aortic thromboembolism (yellow arrow)- sagittal plane, showing the extent of aortic thromboembolism.

Successful surgical thromboembolectomy was performed after being confirmed by multislice computed tomography (MSCT) angiography. She was also treated with LMWH, proton pump inhibitor (PPI), analgesic therapy, cefuroxime, and transfusions of deplasmatized red blood cells.

Although the patient had no fever, respiratory, or any other typical COVID-19-associated symptoms, routine preoperative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test using throat and nasopharyngeal swabs came positive for SARS-CoV-2. The patient was transferred clinically stable to a specific COVID-19 center where she was treated for 2 weeks with oral amoxicillin and clavulanic acid, intravenous PPI, and subcutaneous LMWH. During hospitalization in the center, she was asymptomatic regarding SARS-CoV-2 infection recovering well from surgical intervention. Laboratory and molecular diagnostics for hereditary thrombophilia revealed homozygous MTHFR C677T gene mutation. The patient was discharged with rivaroxaban 15 mg BID and PPI QD.

Four months after discharge, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit due to ALI of unknown etiology. Personal medical history included complaints of nausea in the past month as well as occurrence of jaundice a day before admission. The patient denied using any hepatotoxic substances except rivaroxaban. Other causes of hepatic dysfunction such as portal vein thrombosis, Budd-Chiari Syndrome, viral hepatitis, autoimmune or metabolic diseases of the liver and biliary tract were also excluded.

Contrast-enhanced MSCT of thorax, abdomen, and pelvis ruled out malignancy and confirmed post-COVID-19 characteristic changes in the lungs: locally distributed areas of “ground glass” in the lower lobes of both lungs with perilobular fibrosis. B-mode and color doppler ultrasound of the liver showed normal hemodynamic parameters of liver circulation without signs of cirrhosis. Urgent diagnostic evaluation indicated fulminant liver failure presenting predominantly as acute hepatocellular injury, highly likely DILI (Table 1). Real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction for COVID-19 was negative. Within hours, the patient's state deteriorated to grade 3 hepatic encephalopathy and a transfer to the National Transplant Center for Liver Diseases was organized on the same day.

Table 1.

Summary of laboratory parameters

| Values during admission at emergency unit | Values during hospitalization at COVID-19 center | Values during hospitalization at intensive care unit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hb | 104 | 118 | 94 |

| INR | 1.3 | >6.10 | |

| TBIL | 9.7 | 196 | |

| AST | 31 | 50 | 2,449 |

| ALT | 32 | 58 | 1,953 |

| LDH | 293 | 237 | 581 |

| GGT | 28 | 133 | |

| ALP | 181 | ||

| Creatinine | 43 | 43 | 84 |

Hb, hemoglobin (g/L); INR, international nomalized ratio; TBIL, total bilirubin (µmol/L); AST, aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L); ALT, alanine aminotransferase (IU/L); LDH, lactate dehydrogenase (IU/L); GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase (IU/L); ALP, alkaline phosphatase (IU/L), creatinine (µmol/L).

Due to rapidly progressive liver failure leading to hepatic coma with respiratory insufficiency, management included mechanical ventilation along with other intensive care measures. A liver was allocated within the Eurotransplant network due to a life-threatening condition.

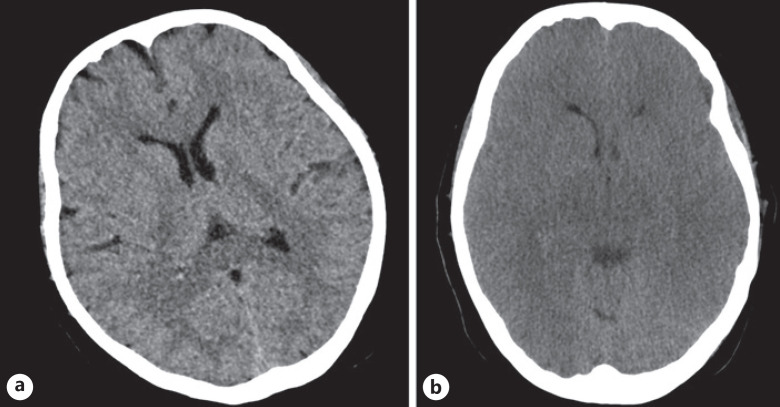

The patient developed tonic-clonic seizures. Brain MSCT confirmed diffuse brain edema of both cerebral hemispheres without signs of brain hemorrhage or ischemia (Fig. 2). Despite intensive treatment measures undertaken, there was no adequate neurological response and general condition deteriorated. The patient died a few days after admission to the transplant center. At the request of the family, the autopsy was not performed.

Fig. 2.

a MSCT of the brain demonstrating brain edema. b MSCT of the brain demonstrating brain edema progression after 2 days.

Discussion and Conclusion

This case illustrates that a combination of congenital thrombophilic and acquired prothrombotic risk factors can contribute to a significant thrombotic event. Although DILI is a common adverse event, to date there have been only rare cases of rivaroxaban-induced liver injury described in literature with only one lethal outcome [11]. We assessed DILI causality as highly probable to rivaroxaban. Key criteria: close and plausible temporal relationship nausea within 3 months of therapy initiation and icterus after 4 months, liver enzyme elevation >10 ULN, and negative differential diagnosis for alternative causes. Percutaneous liver biopsy was contraindicated due to prolonged prothrombin time.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of a lethal outcome due to acute liver failure in a COVID-19 patient treated with rivaroxaban for aortic thrombosis. We advise taking caution when introducing rivaroxaban therapy as well as monitoring liver enzymes on weekly basis for COVID-19-positive patients taking rivaroxaban. Especially, if the patients in question have liver injuries, pre-existing or due to SARS-CoV-2.

Clinicians should give preference to other NOACs that do not lead to hepatocellular damage, such as apixaban and dabigatran. COVID-19 infection is a challenge for clinicians due to the polymorphic clinical picture, the unpredictability of the clinical course, and manifestations of the disease. However, we must not forget about other underlying diseases that may act synergistically for thromboembolic events with SARS-Cov-2, such as hereditary thrombophilia.

Which patients with COVID-19 infection and thromboembolic events should be tested for inherited thrombophilia? This issue is very important because of the duration of anticoagulant prophylaxis. On the other hand, coagulopathy has been reported in up to 50% of patients with severe COVID-19 manifestations [15].

Statement of Ethics

The Ethical Committee of Clinical Hospital Center Split has given its consent to approve this study (reference number: 2181-147/01/06/M.S.-22-02). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's next of kin for publication of the details of their medical case and accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This manuscript did not receive any funding.

Author Contributions

Ivana Jukic, MD, PhD, is the primary author and researcher of this manuscript and was involved in all steps of the process from case data collection, writing and editing of the manuscript. Dorotea Bozic, MD, gastroenterology resident, and Mirela Pavicic Ivelja, MD, PhD, specialist of infectious diseases, assisted in writing of the manuscript. Milos Lalovac, gastroenterologist, MD, PhD; Jonatan Vukovic, MD, PhD; Zeljko Sundov, MD, PhD; and Mislav Radic, MD, PhD; reviewed the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, Driggin E, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC atate-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Jun 16;75:2950–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jothimani D, Venugopal R, Abedin MF, Kaliamoorthy I, Rela M. COVID-19 and the liver. J Hepatol. 2020 Nov;73((5)):1231–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 May 12;75((18)):2352–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomez-Arbelaez D, Ibarra-Sanchez G, Garcia-Gutierrez A, Comanges-Yeboles A, Ansuategui-Vicente M, Gonzalez-Fajardo JA. COVID-19-related aortic thrombosis: a report of four cases. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020 Aug;67:10–3. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2020.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woehl B, Lawson B, Jambert L, Tousch J, Ghassani A, Hamade A. 4 cases of aortic thrombosis in patients with COVID-19. JACC Case Rep. 2020 Jul 15;2((9)):1397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Carranza M, Salazar DE, Troya J, Alcázar R, Peña C, Aragón E, et al. Aortic thrombus in patients with severe COVID-19: review of three cases. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2021 Jan;51((1)):237–42. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02219-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashi M, Jacquin A, Dakhil B, Zaimi R, Mahé E, Tella E, et al. Severe arterial thrombosis associated with Covid-19 infection. Thromb Res. 2020 Aug;192:75–7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garakanidze S, Costa E, Bronze-Rocha E, Santos-Silva A, Nikolaishvili G, Nakashidze I, et al. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene polymorphism (C677T) as a risk factor for arterial thrombosis in georgian patients. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018 Oct;24((7)):1061–6. doi: 10.1177/1076029618757345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björnsson HK, Gudmundsson DO, Björnsson ES. Liver injury caused by oral anticoagulants: a Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Liver Int. 2020 Aug;40((8)):1895–900. doi: 10.1111/liv.14559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maura G, Bardou M, Billionnet C, Weill A, Drouin J, Neumann A. Oral anticoagulants and risk of acute liver injury in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a propensity-weighted nationwide cohort study. Sci Rep. 2020 Jul 15;10((1)):11624. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-68304-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baig M, Wool KJ, Halanych JH, Sarmad RA. Acute liver failure after initiation of rivaroxaban: a case report and review of the literature. N Am J Med Sci. 2015 Sep;7((9)):407–10. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.166221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrinan A, Shackleton L, Kelly C, Lavin M, Glavey S, Murphy P, et al. Liver injury during rivaroxaban treatment in a patient with AL amyloidosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Jul;77((7)):1073–6. doi: 10.1007/s00228-020-03084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verheyen E, Kileci JA, Mathew JP. Single-dose rivaroxaban-induced acute liver injury. Am J Ther. 2019 Jul/Aug;26((4)):e538–40. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000000799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Licata A, Puccia F, Lombardo V, Serruto A, Minissale MG, Morreale I, et al. Rivaroxaban-induced hepatotoxicity: review of the literature and report of new cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Feb;30((2)):226–32. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miesbach W, Makris M. COVID-19: coagulopathy, risk of thrombosis, and the rationale for anticoagulation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020 Jan-Dec;26:1076029620938149. doi: 10.1177/1076029620938149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.