Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of solid self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (S-SNEDDS) formation on the bioavailability of fenofibric acid.

Subject and Methods

Three formulations of fenofibric acid, namely, S-SNEDDS containing medium-chain triglyceride (FS1), S-SNEDDS containing long-chain triglyceride (FS2), and FSt as tablet of innovator product, were used in this study. Bioavailability study was conducted in 12 Indonesian healthy male subjects after a single-dose administration of each formulation with three-way crossover design. Blood samples were collected from 0 to 72 h after drug administration and then analyzed using the high-performance liquid chromatography method. Data were statistically analyzed using the ANOVA and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test using a p value of 0.05. Dissolution test was carried out with USP dissolution apparatus using three medium (pH 1.2, 4.5 and 6.8).

Results

The rates of absorption of fenofibric acid from S-SNEDDS FS1 and FS2 were significantly increased about 1.78 and 2.40 times, respectively, relative to FSt. T<sub>max</sub> values of FS1 and FS2 were shorter than FSt, namely, 0.96 ± 0.438 h (FS1), 0.71 ± 0.445 h (FS2), and 1.71 ± 0.840 h (FSt), respectively. Meanwhile, the C<sub>max</sub> and AUC values of FS1, FS2, and FSt were found to be not significantly different with a p value of >0.05. S-SNEDDS formation increased the dissolution rate in acid medium.

Conclusions

S-SNEDDS increased the dissolution rate in acid medium and absorption rate of fenofibric acid but did not increase the extent of fenofibric acid absorption.

Keywords: Fenofibric acid, S-SNEDDS, Comparative bioavailability

Highlights of the Study

The dissolution of fenofibric acid in solid self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (S-SNEDDS) is higher than the innovator product in acid medium.

S-SNEDDS increased the absorption rate of fenofibric acid in human subjects.

Medium- and long-chain triglycerides in S-SNEDDS did not affect the extent of absorption of fenofibric acid.

Introduction

A solid self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (S-SNEDDS) is described as an isotropic mixture of oil, surfactant, and cosurfactant that is usually adsorbed into a porous carrier to produce a flowable powder. Factors that influence the success of this technique are the selection of carrier excipient (oil, surfactant, cosurfactant, and adsorbent) concentration and solubilization mechanism of lipid excipients [1, 2]. The success of the S-SNEDDS formulation is not only in increasing dissolution but also in the absorption process; therefore, this will significantly determine its bioavailability [3].

The choice of oil is significantly influenced by the type and length of the triglyceride chain and will depend on the lipophilicity of the drug [4, 5]. According to Shahba et al. (2012), cinnarizine can be well formulated and is known to increase the dissolution and bioavailability using medium-chain triglyceride (MCT), compared with short- and long-chain triglyceride (LCT) [6]. However, this is not in line with studies conducted by Baloch et al. (2019) and Daar et al. (2017) with chlorpromazine and flurbiprofen. The formulation using LCT showed increased dissolution and bioavailability of both drugs [7, 8].

Fenofibric acid is an active form of fenofibrate used for the treatment of hyperlipidemia. Fenofibric acid often has poor solubility in water (Biopharmaceutical Classification System Class II), which, in turn, will affect its dissolution and bioavailability. Many previous studies have formulated class II and IV drugs in the form of SNEDDS or S-SNEDDS and have shown improvement in their dissolution. However, there are a very few studies that were followed by a bioavailability study, especially in human subjects [9].

Studies on increasing the dissolution rate and bioavailability of fenofibric acid have been carried out previously in a surface solid dispersion system [10]. Michaelsen et al. [11] have also conducted a study on the formulation and bioavailability assessment of fenofibrate (prodrug) on SNEDDS and super-SNEDDS in an animal model. In our previous study, fenofibric acid was formulated in SNEDDS to increase dissolution. We observed that the dissolution of fenofibric acid in SNEDDS formulations increased 1.6-fold as compared with pure fenofibric acid [12]. In the current study, the liquid SNEDDS was converted into solid dosage form using an adsorbent. Then, the powder was filled into a hard gelatin capsule. Solid SNEDDS is deemed more stable than liquid SNEDDS and can increase portability and patient compliance [13]. Comparative dissolution study of fenofibric acid from the capsules of S-SNEDDS was conducted followed by a bioavailability study in human healthy subjects. For this purpose, a tablet of fenofibric acid from the innovator product was used for comparison.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Fenofibric acid was purchased from BOC Sciences (New York, NY, USA). Kollisolv® MCT 70 (MCT) and Kolliphor® RH 40 (polyethylene glycol 40 hydrogenated castor oil) were kindly gifted by Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik (BASF, Ludwigshafen, Germany). Polyethylene glycol 400, KH2PO4, NaOH, and methanol were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Maisine® CC and Transcutol® HP were kindly gifted by Gattefosse (Lyon, France). Neusilin® US2 was purchased from Fuji Chemical Industries Co., Ltd (Toyama, Japan). Medium dissolutions used were hydrochloride acid (pH 1.2), buffer acetate solution (pH 4.5), and buffer phosphate solution (pH 6.8). Innovator product (the generic version of Fibricor®) was purchased from Halton Laboratories, and 4′-chloro-5-fluoro-2-hydroxybenzophenone (CFHB) and blank human plasma were purchased from the Indonesian Red Cross Society. All solvents used were of analytical grade.

Preparation of Fenofibric Acid in the S-SNEDDS

Each SNEDDS component (oil, surfactant, and cosurfactant) was added to a vial and vortexed at 3,000 RPM for 1 min. FS1 contains Kollisolv® MCT 70 (10% v/v), Kolliphor® RH 40 (80% v/v), and Transcutol® HP (10%v/v). Meanwhile, FS2 contains Maisine® CC (10% v/v), Kolliphor® RH 40 (70% v/v), and Transcutol® HP (20% v/v). Thereafter, fenofibric acid (35 mg) was added and mixed for 2 min at 3,000 rpm and then stirred using a magnetic stirrer for 30 min at 500 rpm at 40°C until a clear solution was obtained. The formulation of fenofibric acid in SNEDDS was adsorbed using Neusilin® US2 with concentrations of 40% w/v. The mixture was then stirred until a homogenous powder was obtained.

In vitro Dissolution Test

In vitro dissolution testing of fenofibric acid from capsules of S-SNEDDS (FS1 and FS2) and innovator product (FSt) was performed using USP dissolution apparatus I (Hanson Virtual Instruments SR8 Plus) in 900 mL each of simulated gastric media (pH 1.2 without enzyme) and intestinal fluid media (pH 4.5 and pH 6.8 without enzyme) at a rotation speed of 100 rpm and temperature of 37 ± 0.5°C. The samples (5 mL) were taken at interval times of 5, 10, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min, and each sample taken was replaced by fresh dissolution medium (5 mL). The amount of fenofibric acid dissolved in each medium was analyzed using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a maximum wavelength of 298 nm.

Subject Preparation

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards for studies in humans of the Declaration of Helsinki 2013 and the International Conference on Harmonisation − Good Clinical Practice [14] and applicable regulatory requirements. The protocol of studies using healthy human volunteers as subjects has been reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia. All eligible volunteers were informed of the aim and risks of this the study and provided written informed consent before participation. This study used 12 healthy male subjects, age between 19 and 50 years, weighing 53–73 kg, and having BMI of 17.8–26.49.

Study Design and Drug Administration

The study design used was open-label, single-dose, fasting conditions, randomized three-way crossover. Drug products used in this study consisted of two S-SNEDDS formulations (FS1 and FS2) in capsules and comparator product (FSt) in the tablet dosage form. The subjects were required to stay and undergo at least 10 h of fasting prior to dosing. The subject's physical activities were standardized during the sampling days. No consumption of alcohol, xanthine-containing food (e.g., coffee, tea, cola, cocoa, etc.), and fruit juices was permitted at least 24 h before the first drug administration and during the sampling period. The meal and liquid intake of the subjects was controlled during the study. Standard meals for both lunch and dinner were served at 4 and 10 h, respectively, after drug administration, while snacks were given at 7 h after drug administration.

Blood samples (5 mL each) were collected into vacuum tubes (Vacutainer) using sodium citrate as anticoagulant at predose (baseline): 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 6, 9, 12, 16, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h after administration of the drug. After being centrifuged at 2,000 g (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5430 R, Hamburg, Germany) for 15 min, the plasma samples were taken and divided into three Eppendorf tubes with distinct codes and kept frozen at −40°C until the analysis was done. The three treatments for each subject were separated by 1-week washout period. The subject's vital signs such as blood pressure, pulse rate, body temperature, respiratory rate, and the occurrence of an adverse event were monitored during the sampling times, and post-study monitoring was also conducted for 2 weeks after the last blood sampling.

Sample Preparation

The concentration of fenofibric acid in plasma samples was determined using a validated high-performance liquid chromatography method developed by Shah et al. [15], 2012, with the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 0.25 μg/mL. The analytical column was Inertsil ODS, C18, 5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm. Determination of fenofibric acid was conducted using the UV detector at a wavelength of 278 nm and a temperature of 25°C. The mobile phase was a mixture of acetonitrile: phosphate buffer pH 2.8 (75:25, v/v), with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and injection volume of 100 μL. The 4′-chloro-5-fluoro-2-hydroxybenzophenone of 100 μg/mL was used as an internal standard. The method was validated before it was used in this study according to FDA guidelines [16].

Pharmacokinetic Calculation and Statistical Analysis

The pharmacokinetic parameters such as Tmax, Cmax, Ke, T1/2, AUC0–t, and AUC0–∞ were calculated by a noncompartment model. Tmax and Cmax values were determined from the drug concentration profile curve in plasma versus time. The Ke value was determined by linear regression from the elimination phase. The half-life was calculated using the formula 0.693/Ke; the AUC0-t was calculated using the trapezoidal method; the AUC0-∞ was estimated using the equation AUC0-t + Ct/Ke, where Ct is the last measured concentration. Tmax and T1/2 were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, while Cmax, AUC0–t, and AUC0-∞ were compared using the ANOVA test followed by Tukey's test. Based on the drug concentration data obtained, the data used to calculate the pharmacokinetic parameters were only until 24 h after drug administration. The reason is because the drug levels in plasma after 24 h for 4 of 12 subjects were below the LLOQ value.

Results

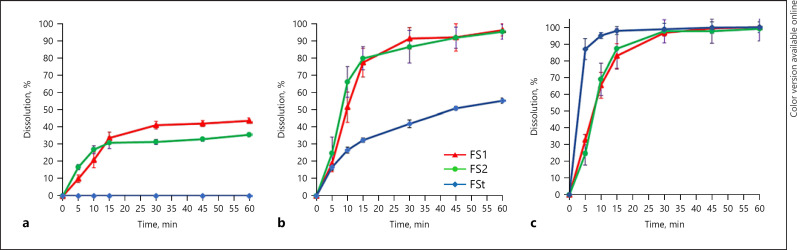

The dissolution profiles of FS1, FS2, and FSt in various media are presented in Figure 1. FS1 and FS2 showed higher percentage dissolution in pH 1.2 and pH 4.5 mediums compared with FSt. The percentage dissolution of FSt in pH 1.2 was not detected even up to 60 min, whereas the dissolution of FSt in pH 4.5 can only reach 55% up to 60 min. The dissolution profile in the phosphate buffer medium pH 6.8 showed that FS1, FS2, and FSt had higher dissolution compared with dissolution in other mediums, approximately 100% in 60 min.

Fig. 1.

Dissolution profile of FS1, FS2, and FSt in different media pH 1.2 (a), pH 4.5 (b), and pH 6.8 (c).

In total, 12 subjects were enrolled in this study. The sequence of drugs administered (FS1, FS2, and FSt) for each period was determined randomly. During treatment, all the vital signs of the subjects such as blood pressure, pulse, and aspiration rate were noted to be in a normal range; no serious adverse events were observed. There were no treatment-emergent laboratory measurements for any subjects attributable to this study. Fenofibric acid, whether administered as S-SNEDDS formulation or comparator product, did not affect the vital sign parameters of the subjects.

The retention time of fenofibric acid and standard internal in plasma was 4.12 min and 7.15 min, respectively. The separation factor (α) value between the analyte and standard internal was around 1.7 times. It was an indicator of the good separation of two peaks. LLOQ value was 0.25 μg/mL. The calibration curve concentration series starts from 0.25 to 20 μg/mL, with a linearity value (r) of 0.999. The precision and accuracy values of the intraday and inter-day assay were estimated by analyzing six replicates containing fenofibric acid at three levels of concentration, that is, 0.25, 5, and 20 µg/mL. The criterion for acceptability of the data was accuracy within ±15% deviation from the nominal value, except at LLOQ, which was set at ±20%.

Discussion

FS1 was the best S-SNEDDS formulation containing MCT (Kollisolv® MCT 70), while FS2 containing of LCT (Maisine® CC) as an oil phase. The dissolution at pH 1.2 showed that fenofibric acid in the form of S-SNEDDS FS1 and FS2 can be dissolved up to 40% within 30 min. However, the amount of drug dissolved after 60 min (43%) was not significantly increased. This may be due to the fenofibric acid being supersaturated in the acid medium that the fenofibric acid molecules are precipitated after 30 min. The capability of the drug dissolved from the formulation of the S-SNEDDS in the acid medium is assumed to be supported by micellar solubilization of surfactant in the formula. Meanwhile, the dissolution of fenofibric acid from FSt cannot be detected in the acid medium for even up to 60 min. This could be attributed to the pH below its pKa value (3.2); fenofibric acid was predominantly in the nonionized state, so the amount of drug dissolved was very small and cannot be detected.

The dissolution profile of FS1 and FS2 in the pH of 4.5 medium was found to have a higher dissolution percentage compared with FSt. At pH 4.5 medium, the fenofibric acid dissolved at FS1 and FS2 was about 96% in 60 min. The solubility of fenofibric acid at this pH was high because the pH > pKa, and the fenofibric acid is in predominantly ionized state due to the role of surfactant in the formula. Fenofibric acid is a weak acid whose solubility depends on pH. The higher the pH of the medium, the higher the fenofibric acid solubility. Hence, at the pH of 6.8, the dissolution of fenofibric acid from all formulations tested was approximately 100%.

Based on the results of dissolution studies for all tested products at various pH values, the S-SNEDDS formulas showed a better dissolution in the acidic medium compared with FSt. However, theoretically, weak acid compounds will be difficult to dissolve or may poorly dissolve in a medium with a pH below the pKa value (acidic medium). In the previous study conducted by Windriyati et al. [10], 2020, the formulation of the fenofibric acid in the form of a surface solid dispersion system was unable to increase its dissolution in acidic pH. This study revealed that the S-SNEDDS formulation can increase the dissolution of fenofibric acid in an acidic medium. This could be due to SNEDDS being able to form nanoemulsion spontaneously when they come in contact with gastrointestinal fluids. These fine globules contain solubilized drugs. Then, the lipids from nanoemulsion are lipolyzed in the stomach by gastric lipase and enzymes present in the intestine. The digestion products that contain the drug are then internalized in the micelles of surfactant, which then results in the solubilization of the drug in GI fluids that can be subsequently absorbed from GI tract [17].

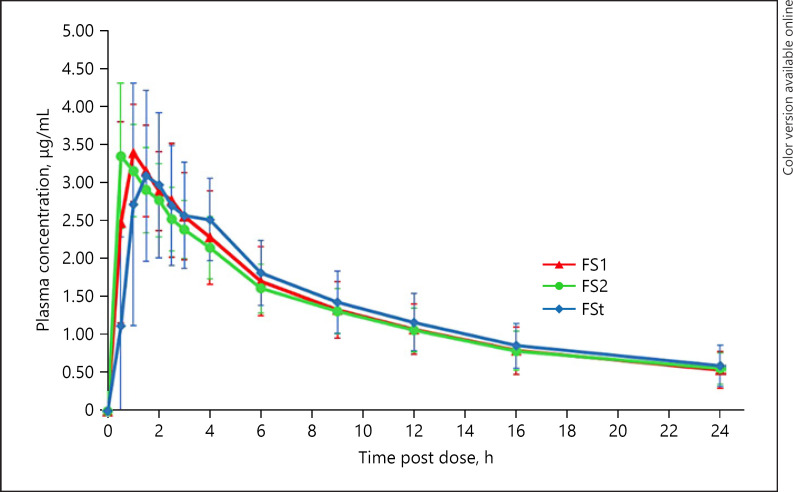

The profile of mean plasma concentration versus time of each tested product is shown in Figure 2. The curves were found to be identical. The absorption phase of FS1 and FS2 could not be observed because at the first sampling time (0.5 h), most of the subjects have reached the maximum concentration in plasma. The Tmax values found from S-SNEDDS were very short, which were unpredictable before. In the design of this study, the sampling time was arranged based on the value of Tmax from the previous studies, with the Tmax value of fenofibric acid of about 2 h [10]. Hence, to get more accurate/precision time, sampling should be performed in the early minutes such as 10 and 20 min after drug administration.

Fig. 2.

Mean plasma versus time curve with SD error bars for fenofibric acid after single oral administration of the test (FS1 and FS2) and reference (FSt) (N = 12).

Fenofibric acid then underwent rapid absorption in the formula FS1 and FS2. Some subjects showed Tmax equal to 0.5 h. These data indicated that the fenofibric acid in the S-SNEDDS had already been absorbed from the stomach. It is assumed that the fenofibric acid molecules that have dissolved in the acid medium (stomach) were absorbed very quickly and reached peak levels in less than 1 h. Meanwhile, FSt that has a low dissolution rate in an acidic medium (pH 1.2 and pH 4.5) showed a relatively slower absorption rate but can produce equivalent Cmax and AUC values. This also proves that fenofibric acid has high permeability properties both in the stomach and in the intestines [18].

The in vitro dissolution of FSt showed that no fenofibric acid dissolved can be detected in the pH of 1.2. The in vivo data showed a different result. The fenofibric acid from the FSt formula was already absorbed within 0.5 h after administration. Assuming that the drug retention time in the stomach was at least 1 h, it means that fenofibric acid from FSt has begun to dissolve in the stomach and be absorbed. This may occur because the pH in the stomach of Indonesian subjects was probably higher than pH of 1.2. This is supported by another study which reported that the gastric juice pH ranged from 1.5 to 3.5 in the lumen of a normal human stomach [19]. Besides, another important contributing factor is the nature of the dynamic equilibrium during absorption of the drug which is lacking in the in vitro conditions. Several endogenous compounds in the stomach, i.e., lipids and lipid digestion products, bile salts, and cholesterol which are secreted in duodenum, may help in micellar solubilization of fenofibric acid [17].

The process of absorption of fenofibric acid in S-SNEDDS formulation was faster than FSt; this could be due to two factors, the solubility of fenofibric acid in SNEDDS and the absorption pathway. Fenofibric acid has been in the dissolved form in the S-SNEDDS formulation; thus, when dispersed in gastrointestinal fluid, the fenofibric acid has been in the molecular form and is ready to be absorbed. Besides, the use of Neusilin® US2 (silica with larger pore diameter) as adsorbent in S-SNEDDS formulation can improve lipid digestion. Therefore, the diffusion and activation of lipase into Neusilin® US2 are faster and facilitate lipid digestion. This is in line with a previous pharmacokinetic study on a novel simvastatin silica-lipid hybrid formulation which indicated that silica-lipid hybrid formulation enhanced the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drug [20].

FS1 and FS2 contain different types of oils. FS1 contains Kollisolv® MCT 70 that is MCT (caprylic/capric acid triglycerides), while FS2 contains Maisine® CC that is an unsaturated long-chain fatty acid (LCT). The Tmax value of FS2 was shorter than FS1. This study revealed that FS2 contains long-chain fatty acid (LCT) and showed that a Tmax value shorter than FS1 contains MCT. Nevertheless, this was not significantly different. Moreover, the difference in triglyceride chain length in the oil phase in S-SNEDDS did not significantly influence the bioavailability of fenofibric acid. This might be due to the amount of oil phase in each S-SNEDDS formulation that tends to be small (only 10%). Therefore, the role of oil constituent used in the SNEDDS did not significantly affect the absorption process of fenofibric acid. This result is consistent with a study in which the use of LCT versus MCT in SEDDS had no impact on the bioavailability of fenofibrate [21].

FSt had Tmax longer than S-SNEDDS formulations. This is related to the dissolution process in the gastric fluids. Based on the results of the FSt dissolution test, fenofibric acid was not detected in the pH 1.2 dissolution media after 60 min. However, in acetate buffer media pH of 4.5, the dissolution of fenofibric acid in 60 min was about 55%. This is in accordance with the pH partition theory, where a weak acid compound ionizes at the pH > pKa so that the ionized drug dissolves and goes into the solution. The fenofibric acid in FSt only dissolves well after being in the intestinal tract with a higher pH, so that the absorption process will occur more in this intestinal tract. This is the reason why Tmax FSt is longer than FS1 and FS2. Conversely, Cmax, Kel, T1/2, and AUC0–t values did not differ significantly among FS1, FS2, and FSt (Table 1). These results indicated that the preparation of fenofibric acid in the form of S-SNEDDS was able to increase the rate of absorption of fenofibric acid. However, the total amount of drug absorbed cannot be increased. A similar result was also found in a previous study using surface solid dispersion dosage form of fenofibric acid. The results also showed that although the surface solid dispersion has a better dissolution than the innovator product, the bioavailability was not deemed significantly different [10]. This could be due to the possibility that fenofibric acid can be absorbed along the GI tract from the stomach to the intestine, and its permeability is very high (Class 2 BCS drug).

Table 1.

Summary of pharmacokinetics parameter of FS1, FS2, and FSt (n = 12)

| Parameters | FS1 | FS2 | FSt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax, h | 0.958±0.438* | 0.708±0.445* | 1.710±0.840 |

| Cmax, μg/mL | 3.631±0.612 | 3.644±0.625 | 3.567±0.750 |

| β, h−1 | 0.065±0.028 | 0.055±0.015 | 0.062±0.025 |

| T1/2, h | 12.216±4.048 | 13.698±4.344 | 12.640±4.246 |

| AUC0–t, μg h/mL | 32.525±10.041 | 31.044±6.538 | 32.088±8.962 |

| AUC0–∞, μg h/mL | 40.849±13.163 | 42.855±11.934 | 44.693±14.780 |

Significantly different.

The S-SNEDDS formulation of fenofibric acid was firstly tested in Indonesian subjects. This study revealed that increased dissolution of S-SNEDDS formulation contributed to the fenofibric acid absorption rate (Tmax), although it did not overall increase the extent of fenofibric acid absorption (AUC and Cmax). Several studies have shown that S-SNEDDS can increase drug bioavailability, along with the Cmax, Tmax, and/or AUC values of human subjects. A previous study showed increased Cmax (2 times) and AUC0–48 (2.3 times) of febuxostat-loaded self-nanoemulsifying self-nanosuspension [22]. Ammar et al. [23] (2018) reported an increase in AUC0–72 of sertraline HCl in S-SNEDDS formulation.

Conclusion

Formation of S-SNEDDS increased the dissolution rate in acid medium and the absorption rate of fenofibric acid in human subjects. The rates of absorption of fenofibric acid from S-SNEDDS formulation were significantly increased from 1.8 to 2.4 times relative to the standard formulation. Tmax was reduced from about 1.7 h to 0.7–1.0 h. However, based on the AUC and Cmax values of the S-SNEDDS formulations, the S-SNEDDS formation did not influence the extent of fenofibric acid absorption from solid dosage form. The length of the chain of triglyceride in the oil phase did not significantly affect the bioavailability of fenofibric acid in S-SNEDDS formulation.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Padjadjaran, Bandung, Indonesia (no.770/UN6. KEP/EC/2019).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was funded through the P3MI Grant Institut Teknologi Bandung 2019 (no. 021.1/SK/I1.C03/KP/2019).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Wira Noviana Suhery, Yeyet Cahyati Sumirtapura, Jessie Sofia Pamudji, and Diky Mudhakir; data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, validation, visualization, project administration, and writing original draft: Wira Noviana Suhery, Yeyet Cahyati Sumirtapura, Jessie Sofia Pamudji, and Diky Mudhakir; supervision: Yeyet Cahyati Sumirtapura, Jessie Sofia Pamudji, and Diky Mudhakir.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Laboratory, Central Research of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, Institut Teknologi Bandung, Indonesia, for all facilities used in this study.

References

- 1.Joyce P, Dening TJ, Meola TR, Schultz HB, Holm R, Prestidge CA, et al. Solidification to improve the biopharmaceutical performance of SEDDS: opportunities and challenges. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;142:102–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi JE, Kim JS, Choi MJ, Baek K, Woo MR, Jin SG, et al. Effects of different physicochemical characteristics and supersaturation principle of solidified SNEDDS and surface-modified microspheres on the bioavailability of carvedilol. Int J Pharm. 2021;597:120377. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh G, Pai RS. Trans-resveratrol self-nano-emulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS) with enhanced bioavailability potential: optimization, pharmacokinetics and in situ single pass intestinal perfusion (SPIP) studies. Drug Deliv. 2015 May 19;22((4)):522–30. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.885616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Izgelov D, Shmoeli E, Domb AJ, Hoffman A. The effect of medium chain and long chain triglycerides incorporated in self-nano emulsifying drug delivery systems on oral absorption of cannabinoids in rats. Int J Pharm. 2020;580:119201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weerapol Y, Limmatvapirat S, Sriamornsak P. Effect of lipophilicity of drugs on dissolution profiles of self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system. Adv Mater Res. 2015;1060:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shahba AA, Mohsin K, Alanazi FK. Novel self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems (SNEDDS) for oral delivery of cinnarizine: design, optimization, and in-vitro assessment. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2012 Sep 1;13((3)):967–77. doi: 10.1208/s12249-012-9821-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baloch J, Sohail MF, Sarwar HS, Kiani MH, Khan GM, Jahan S, et al. Self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery System (SNEDDS) for improved oral bioavailability of chlorpromazine: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Medicina. 2019 May;55((5)):210. doi: 10.3390/medicina55050210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daar J, Khan A, Khan J, Khan A, Khan GM. Studies on self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system of flurbiprofen employing long, medium and short chain triglycerides. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2017 Mar 1;30((2)):601–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee B, Hamed AS, Ahmed MDA, Mandal UK, Sengupta P. Controversies with self-emulsifying drug delivery system from pharmacokinetic point of view. Drug Deliv. 2016 Nov 21;23((9)):3639–49. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2016.1214990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Windriyati YN, Sumirtapura YC, Pamudji JS. Comparative in vitro and in vivo evaluation of fenofibric acid as an antihyperlipidemic drug. Turk J Pharm Sci. 2020;17((2)):203. doi: 10.4274/tjps.galenos.2019.27147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michaelsen MH, Jørgensen SD, Abdi IM, Wasan KM, Rades T, Müllertz A. Fenofibrate oral absorption from SNEDDS and super-SNEDDS is not significantly affected by lipase inhibition in rats. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2019 Sep 1;((142)):258–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suhery WN, Sumirtapura YC, Pamudji JS, Mudhakir D. Development and characterization of self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS) formulation for enhancing dissolution of fenofibric acid. J Res Pharm. 2020;24((5)):738–47. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quan G, Niu B, Singh V, Zhou Y, Wu CY, Pan X, et al. Supersaturable solid self-microemulsifying drug delivery system: precipitation inhibition and bioavailability enhancement. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:8801. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S149717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jahrbuch für Wissenschaft Und Ethik. 2009 Dec 24;14((1)):233–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah I, Barker J, Barton SJ, Naughton DP. A novel method for determination of fenofibric acid in human plasma using HPLC-UV: application to a pharmacokinetic study of new formulations. J. Anal Bioanal Tech. 2014 Mar 4;((12)):9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Department of Health and Human Services . Bioanalytical method validation, guidance for industry. 2001. Available from. http://www.fda.gov./cder/guidance/4252fnl.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maji I, Mahajan S, Sriram A, Medtiya P, Vasave R, Singh PK, et al. Solid self-emulsifying drug delivery system: superior mode for oral delivery of hydrophobic cargos. J Control Release. 2021;337:646–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu T, Ansquer JC, Kelly MT, Sleep DJ, Pradhan RS. Comparison of the gastrointestinal absorption and bioavailability of fenofibrate and fenofibric acid in humans. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50((8)):914–21. doi: 10.1177/0091270009354995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marieb EN, Hoehn K. Human anatomy and physiology. 8th ed. San Francisco, CA, USA: Benjamin Cummings; 2010. p. p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meola TR, Abuhelwa AY, Joyce P, Clifton P, Prestidge CA. A safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic study of a novel simvastatin silica-lipid hybrid formulation in healthy male participants. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2021 Jun;11((3)):1261–72. doi: 10.1007/s13346-020-00853-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffin BT, Kuentz M, Vertzoni M, Kostewicz ES, Fei Y, Dressman JB, et al. Comparison of in vitro tests at various levels of complexity for the prediction of in vitro performance of lipid-based formulations: case studies with fenofibrate. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2014;86((3)):427–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ElShagea HN, ElKasabgy NA, Fahmy RH, Basalious EB. Freeze-dried self-nanoemulsifying self-nanosuspension (SNESNS): a new approach for the preparation of a highly drug-loaded dosage form. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2019 Oct;20((7)):258–4. doi: 10.1208/s12249-019-1472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ammar HO, Ghorab MM, Mostafa DM, Ghoneim AM. Spray dried self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery systems for sertraline HCl: pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers. Int J Pharm Sci Dev Res. 2018 Jun 27;4((1)):009–19. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.