Abstract

Introduction

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is gaining popularity and is applied in a variety of clinical settings. This review aims to present and evaluate available evidence regarding the use of PRP in various applications in plastic surgery.

Methods

PubMed, Web of Science, Medline, and Embase were searched using predefined MeSH terms to identify studies concerning the application of PRP alone or in combination with fat grafting for plastic surgery. The search was limited to articles in English or German. Animal studies, in vitro studies, case reports, and case series were excluded.

Results

Of 50 studies included in this review, eleven studies used PRP for reconstruction or wound treatment, eleven for cosmetic procedures, four for hand surgery, two for burn injuries, five for craniofacial disorders, and 17 as an adjuvant to fat grafting. Individual study characteristics were summarized. Considerable variation in preparation protocols and treatment strategies were observed. Even though several beneficial effects of PRP therapy were described, significance was not always demonstrated, and some studies yielded conflicting results. Efficacy of PRP was not universally proven in every field of application.

Conclusion

This study presents an overview of current PRP treatment options and outcomes in plastic surgery. PRP may be beneficial for some indications explored in this review; however, currently available data are insufficient and systematic evaluation is limited due to high heterogeneity in PRP preparation and treatment regimens. Further randomized controlled trials employing standardized protocols are warranted.

Keywords: Autologous blood products, Healing, Therapy

Introduction

Over the past years, autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) has gained significant attention among various medical specialties, including, but not limited to, orthopedics, dermatology, gynecology, oro-maxillofacial surgery, and plastic surgery. PRP has been applied in a variety of clinical settings based on the assumption that it stimulates tissue regeneration, among other postulated positive effects, due to the presence of growth factors and cytokines [1].

The anticipated impact on tissue repair drives increased consideration for use of PRP in treating chronic wounds, burn injuries, and scars, hence establishing a promising supplemental approach in reconstructive plastic surgery. The application of PRP has also become more frequent in aesthetic surgery, i.e., in facial rejuvenation or in treatment of alopecia [2]. As a carrier-containing anti-inflammatory mediator, PRP is believed suppress inflammation in osteoarthritis, thereby promoting cartilage repair and temporizing pain [3]. In addition, PRP is used in bone grafting to support osseointegration and increase the odds of graft survival [4]. PRP is also introduced as an adjuvant to lipofilling since it is theorized to increase fat graft survival rates [5]. In addition to its beneficial therapeutic effects, it is easily obtained and cost-effective.

Despite increasing clinical popularity, the efficacy of PRP remains controversial due to the lack of consistent data and discord among researchers concerning the classification of PRP. Even though PRP is employed in a variety of medical fields, such as the different pillars of plastic surgery, current studies show notable inhomogeneity concerning the preparation process, control groups (CGs), and objective outcomes [6]. The purpose of this study was to demonstrate the current role of PRP and its application in plastic surgery, identify different techniques of preparation, and present current evidence for the use of PRP.

Background

PRP is defined as the portion of the plasma fraction of blood with a platelet count above baseline [7]. Platelets carry secretory alpha granules, which release a high number of biologically active proteins including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor, basic fibroblastic growth factor, vascular growth factor, transforming growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor. As a result, tissue regeneration and remodeling, angiogenesis, re-epithelialization, and collagen formation are promoted [6].

The preparation process for PRP varies since no standardized protocol has been established so far. The procedure involves drawing venous blood − in most cases a small volume between 5 and 50 mL − followed by centrifugation. The duration, force, and number of centrifugation cycles depend on the device. This step separates the blood in the tube into three different layers: red and white blood cells (bottom), PRP (middle), and platelet-poor plasma (PPP, top). After extracting the platelet-rich component, platelets can be activated by adding thrombin (Thrb) and calcium chloride (CaCl). However, some authors argue that this step is not a requirement [2]. Anticoagulation is necessary to stabilize the platelets and prevent clotting. In most cases, the tube used for the venipuncture already contains an anticoagulant coat [5].

Various classification systems for different types of PRP and platelet-rich concentrations in general have been proposed, but there is still no consensus on which classification system is the most suitable. One of the most common classification systems was established by Dohan Ehrenfest et al. [65]. The authors suggested dividing PRP into four main groups, depending on the presence of white blood cells (leucocyte rich or poor) and the density of the fibrin network (high or low density). The classification system according to Mishra et al. [66] separates PRP in four different categories as well. The most important factors for this classification are the platelet concentration and the absence or presence of leucocytes [8]. The DEPA classification by Magalon et al. [67] which was introduced in 2016 is based on the dose of platelets injected, as well as the efficiency, purity, and activation of PRP [2]. Recently, Lana et al. [8] proposed a new classification system called “MARSPILL,” which is based on eight parameters concerning the preparation and application of PRP: method (automated or handmade), activation, red blood cells (rich or poor), spin (one or two spins), platelet number, image guidance, leucocyte concentration, and light activation.

The hypothesis that the growth factors and cytokines provided by PRP support tissue regeneration, thereby restoring structure and function, has been confirmed in various in vitro studies and animal models. These effects may provide a major advantage in clinical settings of plastic surgery, since effective union of damaged tissue is crucial for satisfactory clinical outcome in this field. PRP has emerged as a promising treatment approach in various areas and subdomains of plastic surgery; however, the extent of its clinical efficacy remains uncertain due to lack of standardized research [9]. We performed a systematic review in order to present the currently available studies on PRP therapy within all branches of plastic surgery, evaluate evidentiary support for the efficacy of PRP treatment, and discuss preparation methods.

Materials and Methods

Literature Search

The databases PubMed, Web of Science (core collection), Embase, and Medline (via Ovid) were queried for studies concerning the therapeutic use of PRP in plastic surgery. A systematic search was performed until the December 1, 2021. To cover all pillars of plastic surgery, the following subject headings were used:

(“Plastic surgery” OR “aesthetic surgery” OR “reconstructive surgery” OR “hand surgery” OR “breast surgery” OR “burns”) AND (“platelet-rich plasma” OR “PRP”).

Depending on the database, further search restrictions (article type, search category, language, studied species) were predefined to optimize the results and exclude nonrelevant material by adjusting the search filter. The added limitations are portrayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Limitations added to query via refinement filters

| Search terms | Language | Species | Include article types | Exclude article types | Include category | Exclude category | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OVID: Embase, Medline |

(Plastic surgery, reconstructive surgery, aesthetic surgery, hand surgery, breast surgery) AND (platelet-rich plasma, PRP); burns AND platelet-rich plasma | x | Human | x | x | x | x |

|

| |||||||

| Web of Science Core collection |

(Plastic surgery, reconstructive surgery, aesthetic surgery, hand surgery, breast surgery, burns) AND (platelet-rich plasma, PRP) | English German | Human | x | Letters, review articles, book reviews, notes | Surgery, transplantation, emergency medicine | Dermatology, dentistry/oral surgery, gynecology, nephrology/urology, ophthalmology, orthopedics Rheumatology Sports sciences, veterinary sciences, zoology |

|

| |||||||

| PubMed | (Plastic surgery, reconstructive surgery, aesthetic surgery, hand surgery, breast surgery, burns) AND (platelet-rich plasma, PRP) | English, German | Human | Clinical study, clinical trials and protocols, comparative study, controlled study, evaluation study, observational study, RCT | x | x | x |

x, not applied/not possible for this database.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The search was limited to studies in English or German. Only clinical studies that investigated the treatment with autologous PRP alone or as an adjuvant in fat grafting (FG) in humans were included. All animal and in vitro studies were excluded, as well as case reports and case reviews. Trials were only included if the product they investigated was defined as “platelet-rich plasma” in their report. PRP-related products, for example, platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) or its derivatives (platelet-rich fibrin matrix), were not explored in this review.

All studies had to be conducted at a department for plastic surgery or by a physician who specializes in that field. Publications concerning medical specialties such as dermatology, orthopedics/trauma, oro-maxillofacial surgery, ophthalmology, periodontology, or any other center that was not defined as a division or subdivision of plastic surgery were eliminated.

Data Extraction

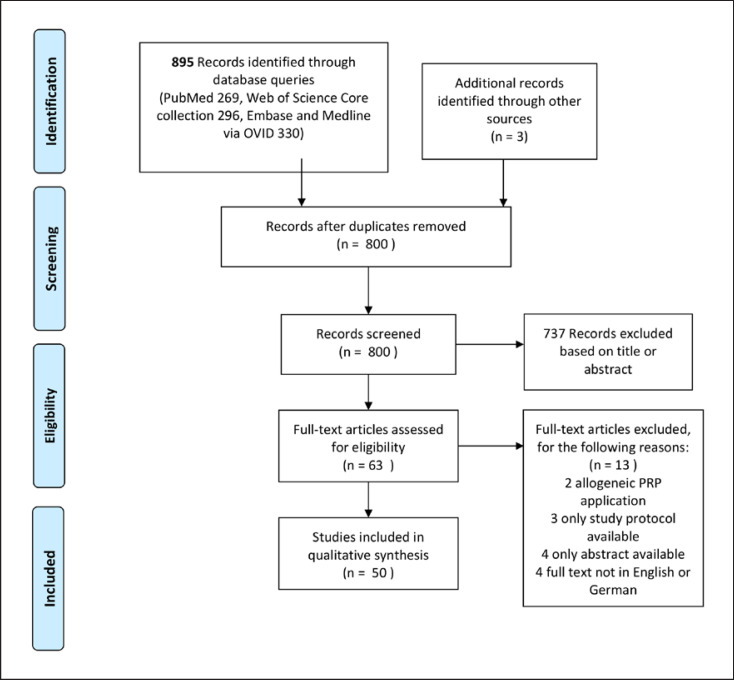

Following the assembly of the findings of all databases, duplicates were manually removed. First, all titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility, followed by a full-text review of the remaining studies. The study selection process has been highlighted in the flowchart shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart describing the review process.

Results

A total of 895 results were obtained through literature search. Three records were identified through other sources. After deduplication, 800 articles remained and were screened thoroughly. Fifty papers met the previously described inclusion criteria and were included in this review.

These studies were divided into sections according to their field of application in plastic surgery, namely: reconstructive surgery, aesthetic surgery, hand surgery, craniofacial surgery, and burn injury treatment. The use of PRP in FG was classified as an independent segment.

Eleven studies investigating the application of PRP in reconstructive plastic surgery were included. Five of them treated chronic wounds or ulcers with PRP injections or gel application [10, 11, 12, 13, 14]. Two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) compared PRP application to conventional fixation with split-thickness skin grafts (STSGs) [15, 16]. In 1 case, PRP was applied to the donor site to accelerate wound healing [17]. Two studies aimed to reduce postoperative complications after breast reconstruction with PRP application [18, 19]. Another study investigated the effects of PRP injections in keloid scars with the objective to improve scar quality and reduce pain [20].

In total, eleven studies reported the use of PRP in aesthetic plastic surgery, which was further subcategorized into “facial” and “hair growth” interventions. The most common indications were androgenetic alopecia (AGA) and alopecia areata. One paper described the use of PRP as a preservation solution for hair transplantation [21]. Three studies had a PRP and a placebo group, whereas one compared different types of PRP (activated vs. nonactivated autologous vs. homologous PRP) without a CG in AGA therapy [22, 23, 24, 25]. In one study, plasma was enhanced with dalteparin and protamine microparticles to evaluate if these growth factor carriers would result in better hair growth than conventional PRP, and one author explored the effects of the plant derivative QR678 in contrast to intradermal PRP injections in a randomized controlled study [26, 27]. The bioengineered formulation of QR678 was introduced by Kapoor and Shome in 2018. It contains a variety of biomimetic peptides, as well as vitamins, minerals, and amino acids and has been proven to be an efficient therapeutic approach for AGA for both male and female patients [26].

Two studies injected PRP to achieve facial rejuvenation [28, 29]. PRP gel was applied in two trials: one of them performed blepharoplasty, and the second one used it to improve face lifting outcome [30, 31].

The field of hand surgery is considered a sub-specialty that is shared between plastic, orthopedic, and general surgeons. Therefore, all studies concerning PRP therapy for procedures that are of interest for the plastic hand surgeon were included, regardless of the main medical specialty of the investigator. In total, four articles concerning plastic surgery of the hand were retrieved [32, 33, 34, 35]. In a comparative study (CS), patients with mild carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) were treated with either PRP or corticosteroid injections. Three authors performed intra-articular PRP injections as a treatment for carpometacarpal arthritis of the thumb joint. Two RCTs focused on the treatment of severe burns with PRP-enhanced skin grafts (SGs) [36, 37].

Craniofacial procedures fall under the scope of oro-maxillofacial surgery, as well as plastic surgery. A total of five studies conducted by plastic surgeons investigated the efficacy of PRP in bone grafting for alveolar cleft treatment, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, or other maxillofacial conditions [38, 39, 40, 41, 42]. All these studies were either CS or case-control (CC) study, and no RCTs were found.

Seventeen studies concerning to combination of PRP application and fat grafts were found, and three of those were RCTs [43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59]. Eight articles fell under the category “reconstruction,” focusing on chronic ulcers and wounds (three), scars (three), or breast reconstruction (two). Another eight studies administered PRP and autologous fat to improve the aesthetic outcome of lipofilling to the face and hand (six), the calf region (one), or the gluteal area (one). One study explored the effects of PRP mixed-microfat in 3 patients with wrist osteoarthritis. For a better overview, analysis and detailed descriptions of the included trials are presented in tabular form in Table 2.

Table 2.

Study details

| Author | Design | N | Intervention | Objective | Results | AEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction, wounds | ||||||

| Dhua et al.[15] | RCT | 40 | PRP versus mechanical fixation for STSG in wound bed | Graft loss, graft discharge, morbidity (hematoma, edema, pain), duration of stay, frequency of dressings, costs | PRP: instant graft take*; less graft loss, and morbidity* Lower costs and duration of stay | Related to PRP nm |

| Harper et al. [18] | RCT | 12 | L-PRP spray versus control for latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction | Reduction of drain burden (drain output volume, time to drain removal) and seroma formation | No benefit with L-PRP; 1 hematoma, 1 seroma reported (both in TG) | Hematoma (1) seroma (1) |

| Helmy et al. [10] | RCT | 80 | PRP versus conventional treatment for chronic venous leg ulcers | Rate of healing, reduction in ulcer size (%), recurrence, side effects | PRP: better healing results*, shorter healing time* higher % in reduction* no recurrence (11 in CG), no AEs, pain decrease | None |

| Hersant et al. [19] | Pro-study | 54 | PRP gel in breast reduction and weight loss sequelae surgery | Postoperative complications (seroma and hematoma) formation, wound healing/scar quality (POSAS) | Less complications in TG for limb lifting and breast reduction*; no difference in scar quality for all procedures | nm |

| Hersant et al. [20] | Pro-pilot study | 17 | PRP injection for keloid scar treatment | Remission of scars, VSS (including pruritus severity), pain (VAS) | 53% healed, 29% complete relapse (difference between groups*); decrease in VSS (pruritus)* | None |

| Moghazy et al. [11] | − | 40 | PRP gel versus VAC in complex wound management | Wound grading, change in wound surface, wound exudate, pain (VAS) | Decrease in wound size in both groups*; less pain in PRP group*; higher reduction rate in VAC group* | Wound sinus |

| Rainys et al.[12] | RCT | 69 | PRP gel versus control in chronic leg ulcers | Wound size, granulation tissue, microbiological wound bed changes, safety | PRP: Higher wound size reduction* and granulation tissue formation* higher wound contamination CG: wound size reduction*; no AEs in either group | No serious AEs |

| Saad Setta et al. [13] | CS | 24 | PRP versus PPP for chronic diabetic foot ulcers | Healing rate (measured length and width of ulcer), wound characteristics (exudation, necrosis, infection, granulation) | PRP: shorter haling time*; no significant differences in clinical signs between groups | nm |

| Slaninka et al. [17] | RCT | 24 | PRP versus control in healing SG donor sites | Healing quality (% of healed area assessed visually) and time | PRP: median healing time shorter*; accelerated healing | nm |

| Waiker and Shivalingappa [16] | RCT | 200 | PRP versus conventional fixation for STSG | Graft uptake or loss, hematoma or discharge, edema, frequency of dressing change, duration of hospital stay | Favorable results for all outcome parameters in PRP group*; high rate in instant graft take | nm |

| Xie et al. [14] Aesthetic | 25 | Platelet gel versus conventional dressing for diabetic sinus tract wounds | Sinus tract closure time, ulcer healing rate, hospitalization time and costs | APG: lower costs* shorter stay* higher healing rate, closure rate higher* until week 4, not at week 8 | None | |

|

| ||||||

| Aesthetic | ||||||

| Hair growth | ||||||

| Abdelkader et al. [21] | RCT | 30 | PRP versus saline as a preservation solution for hair transplantation | Hair graft uptake, hair follicular density, patient satisfaction | Higher hair thickness and graft uptake (after 1 year) in PRP group*; more rapid hair growth | − |

| Gentile et al. [22] | RCT | 23 | PRP versus placebo for hair growth | Hair regrowth, hair dystrophy, cell proliferation, itching sensation | Increase in hair count, total hair density, epidermal thickness, and epidermal cell proliferation* | None |

| lnce et al. [23] | − | 46 | aPRP versus nPRP versus hPRP injection for AGA | Hair density, average platelet number, complications | Higher hair density in all groups*; most of all in hPRP; highest platelet count and lowest preparation time for hPRP | None |

| Kapoor et al. [26] | Pro-CS | 50 | PRP versus QR678 injection for AGA | Hair fall rate, hair density, terminal hair, vellus hair, shaft diameter | Higher density and shaft diameter in non-PRP group* | Itchy scalp, light-headedness during |

| Kumar et al. [24] | Pro-CS | 40 | PRP versus placebo for AGA | Hair count, density, diameter, anagen/telogen, and terminal/vellus ratio | Higher increase in hair count, density, telogen/anagen ratio | injection Slight pain during injection, no major AEs |

|

| ||||||

| Singh [25] Takikawa et al. [27] Face Davis and Augenstein [28] |

Pro-study Clinical trial CS |

20 26 8 |

PRP for chronic alopecia areata PRP + D/P MPs versus PRP + saline for hair growth PRP versus amniotic allograft for midface aging correction |

Efficacy of PRP Aesthetic result, patient downtime, level of comfort, office time |

Improved hair growth, no side effects, only 1 relapse Increase in hair growth and thickness in both groups Improvement in both groups; quicker results and less downtime in non-PRP group |

None Discomfort during injection, no major AEs Hematoma, slight burn upon injection |

| Hersant et al. [29] | RCT | 93 | a-PRP or HA or PRP + HA injection for facial rejuvenation | Facial appearance Skin elasticity | Improvement in PRP + HA group compared to PRP or HA alone*; gross elasticity improved in all 3 groups | Mild bruising |

| Powell et al. [31] | RCT | 8 | Unilateral treatment with PRP gel versus control side for deep-plane rhytidectomy | Response to treatment judged by occurrence of edema and ecchymosis in buccal, preauricular, and cervical region of the face | Response to effect of PRP: ecchymosis − 13 positive, 9 equal, 3 negative; edema − 8 positive, 11 equal, 6 negative; no significance | None |

| Vick et al. [30] | RCT | 33 | PRP gel versus control for blepharoplasty | Postoperative occurrence of edema and ecchymosis, post-op discomfort | No significant difference in discomfort or ecchymosis; less edema in TG at day 1 and 30* | nm |

| Hand | ||||||

| Loibl et al. [33] | Pilot study 10 | Leucocyte-poor PRP for thumb joint arthritis | Changes in VAS, DASH, mayo wrist score, strength | Pain decrease*, improvement in mayo wrist score* | Palmar wrist ganglion (1) | |

| Malahias et al.[34] | RCT | 33 | PRP versus corticosteroids for thumb joint arthritis | Changes in VAS, quick-DASH, patient satisfaction | Better results for all parameters in PRP group after 12 months* | nm |

| Abdelsabor Sabah et al. [35] | RCT | 45 | PRP versus HA versus corticosteroids for thumb joint arthritis | Changes in VAS, strength, AUSCAN score, tenderness grading | Overall improvement for all groups after 4 weeks* only maintained for HA group after 12 week* | nm |

| Uzun et al.[32] | C-C | 40 | PRP versus corticosteroid injection for CTS | Change in NCS and BCTQ | No significant difference in NCS; higher BCTQ in PRP group at 3 months* | None |

|

| ||||||

| Burns | ||||||

| Gupta et al. [36] | RCT | 200 | PRP versus control as preparation for STSG | Graft adherence, complication rate | Better graft uptake in PRP group*; less hematomas in PRP group | nm |

| Marck et al. [37] | RCT | 52 | PRP versus control for deep dermal burns with SSG | Graft uptake and re-epithelialization; pain, complications, scar quality | No significant differences | Hematoma |

|

| ||||||

| Craniofacial | ||||||

| Chen et al. [38] | Pro-CS | 20 | PRP versus control for bone grafting for unilateral alveolar cleft | Newly formed bone volume, bone formation (BF) after PRP | No statistical difference in BF; faster recovery and less graft failure in PRP group | None |

| Gentile et al. [39] | C-C | 25 | PRP gel versus control for maxillofacial surgery | Bone regeneration of the jaw, morbidity | Less pain and infection in PRP group*; higher bone regeneration (54% in TG vs. 38% in CG) | No major AEs |

| Hanci et al. [40] | Pro-CS | 20 | PRP injection versus arthrocentesis for TMJ disorder | ROM, relief of functional pain, noise with joint movement | Less pain and joint sound in PRP group*; increase in mouth opening | No major AEs |

| Oyama et al. [41] | C-C | 23 | PRP versus control for iliac bone graft in alveolar cleft patients | Regenerated bone volume in CT | Higher rate of bone regeneration* in TG | None |

| Sakio et al. [42] | C-C | 29 | PRP versus control for alveolar bone grafting for unilateral cleft lip | Bone volume | No significant difference | Temporary wound dehiscence |

| Lipofilling + PRP | ||||||

| Bilkay et al. [43] | CS | 52 | FG with or without PRP for calf augmentation | Number of sessions needed for satisfactory result | Lower mean n of sessions in PRP group (2.0)* versus without PRP (2.95) | Infection (1) |

| Cervelli et al. [44] | − | 20 (vs. 10) | PRP gel + FG for lower extremity ulcers (vs. HA + collagen) | Re-epithelialization time | 16 ulcers restored at 9.7 weeks in PRP group (2 out of 10 in CG) | nm |

| Fontdevila et al. [45] | Clinical trial | 49 | PDGF + FG versus FG alone for facial lipoatrophy | Safety of treatments, improvement in facial structure/volume gain (clinical and via CT) | Improvement in facial atrophy and increase in volume in both groups* no difference in volume gain between TG and CG, no serious AEs | No serious AEs |

| Gentile et al. [46] | CS | 23 | PRP + FG versus SVF + FG versus control for breast reconstruction | Maintenance of contour restoring and 3D volume | 69% maintenance with PRP* and 63% with SVF* versus 39% control after 1 year overall satisfaction | No major AEs |

| Gentile et al. [47] | C-C | 20 | PRP + FG versus SVF + FG versus control for facial scars | Tissue regeneration (assessed visually by doctors and patients, MRI, US) | 69% maintenance with PRP* and 63% with SVF* versus 39% control after 1 year; overall satisfaction | None |

| Majani and Majani [48] | − | 28 | PRP before FG versus PRP + FG simultaneously versus FG alone for scar correction | FG improvement, aesthetic outcome, scar elasticity, dyschromia | Improvement in all groups at 30 d; more durable results with PRP | nm |

| Mayoly et al. [49] | Clinical trial | 3 | PRP mixed-microfat injection for radio-carpal osteoarthritis | Safety, complications, pain (VAS), function (DASH, PRWE), ROM, wrist strength, patient satisfaction | No serious AEs, pain decrease >50%, improvement in DASH and PRWE | None |

| Rigotti et al. [50] | CS | 13 | PRP + FG (vs. SVF + FG vs. adipose-derived stem cells vs. control) for facial rejuvenation | To determine the best approach for facial skin regeneration | Greater vascular reactivity in PRP group, no significant advantages in regeneration compared to other groups | nm |

| Salgarello et al. [51] | cs | 42 | PRP + FG versus conventional Coleman technique for breast FG | Clinical outcome (according to patient and doctor), liponecrosis rate (US), need for revision | No superiority of PRP group proven | nm |

| Sasaki [52] | Pro-C-C | 236 | PRP versus SVF versus PRP + SVF versus control for midface FG | Volume retention | Higher graft retention for all TG at 1 year*; PRP and SVF equally effective | No serious AEs |

| Sasaki [53] | − | 10 | FG for face or dorsal hand with or without PRP | Retention of fat volume and improvement in skin elasticity | Higher, but non-s volume restoration in PRP group | None |

| Segreto et al. [54] | Pro-study | 14 | nL-PRP + nanofat for infected chronic wounds | Pain reduction (VAS), wound depth, re-epithelization (%) |

53.8% healed completely (re-epithelization in 9.1 week, VAS 0); 30% improvement (wound depth reduction of 57.5%, VAS decrease of 42%) | nm |

| Smith et al. [55] | RCT | 18 | PRP + FG versus FG versus control for diabetic foot ulcers | Feasibility of trial, HRQoL, clinical outcome (wound size, healing, PUSH score, costs, AEs) | Feasibility proven, no differences in clinical outcomes, no serious AEs | Infection (3) |

| Tenna et al. [56] | CS | 30 | PRP + FG with or without fractional C02 laser for atrophic acne scars | Patient satisfaction and aesthetic perception via FACE questionnaire, thickness of subcutaneous tissue | Improvement of tissue thickness and FACE-Q in both groups, nonsignificant | nm |

| van Dongen et al. [57] | RCT | 28 | SVF + PRP + FG versus PRP + FG + saline for facial lipofilling | Improvement in skin elasticity, transdermal water loss, skin appearance (wrinkles, pigmentation, etc.), patient satisfaction (FACE-Q), recovery, AEs | No overall benefit with SVF; no improvement in skin quality in TG or CG; FACE-Q improvement in CG No major AEs | None |

| Willemsen et al. [58] | − | 21 | Gluteal augmentation with PRP + FG | Patient satisfaction and clinical results | Increased but subjective patient satisfaction, consistent results, safe procedure, low complication rate | Infection (1) |

| Willemsen et al. [59] | RCT | 32 | PRP versus control for facial lipofilling | Skin elasticity improvement, changes in skin, recovery time, and satisfaction according to patient | Faster recovery in PRP group* otherwise no significant differences between groups | None |

Asterisk means significant. AEs, adverse events; Pro, prospective study; RCT, randomized controlled trial; C-C, case-control study; CS, comparative study; TG, treatment group; CG, control group; STSG, split-thickness skin graft; SG, skin graft; HA, hyaluronic acid; FG, fat grafting; SVF, stromal vascular fraction; PPP, platelet-poor plasma; a-PRP/n-PRP/h-PRP, activated/nonactivated/homologous PRP; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factors; VAS, visual analogue scale; POSAS, patient and observer scar assessment scale; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; PUSH score, pressure ulcer scale for healing (quick); DASH (shortened), disability of shoulder and hand questionnaire; AUSCAN, score for pain, disability, joint stiffness in hand osteoarthritis; ROM, range of motion; PRWE, patient-rated wrist evaluation; NCS, nerve conduction studies; BCTQ, Boston Carpal Tunnel Questionnaire.

Complications

Overall, little to no side effects were observed. Only three out of 50 studies reported isolated occurrences of hematomas [18, 28, 37]. One patient developed a palmar wrist ganglion, which receded quickly and without need for intervention [33]. The most common side effect of PRP injections to the scalp or to the face was mild discomfort or light-headedness during the injection, which subsided shortly after the procedure [24, 26, 27, 28]. The 5 patients that exhibited signs of infection had all been treated with PRP-enhanced FG; therefore, one cannot be certain whether the PRP or the lipofilling itself was responsible for these side effects [43, 55, 58]. However, most patients did not experience any negative effects related to PRP application. No serious adverse event (AE) occurred in any of the studies. All authors concurred that the therapeutic use of PRP is safe.

PRP Preparation

The studies included in this review showed notable heterogeneity in terms of PRP preparation methods. Many factors had to be considered, such as differences in number of PRP applications or the use of activators. In seventeen studies [10, 11, 13, 14, 15, 21, 24, 27, 31, 34, 35, 38, 40, 41, 42, 50, 53], double spin centrifugation was performed, 21 studies used a single spin protocol [16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 29, 30, 32, 33, 36, 37, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 51, 58], and twelve authors merely disclosed the name of the device used, or no information about this process at all [12, 18, 25, 26, 28, 39, 52, 54, 55, 56, 57, 59]. Twenty-two authors reported the use of CaCl and/or Thrb for platelet activation [11, 13, 14, 15, 18, 19, 21, 24, 28, 30, 31, 37, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 50, 51, 58]. Nonactivated PRP (na-PRP) was applied in 6 cases [34, 52, 53, 54, 55, 57], and two authors reported the use of both na-PRP and a-PRP [22, 23]. One author applied photo-activated PRP [40]. The remaining studies did not mention this step of the process [10, 12, 16, 17, 20, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 41, 48, 49, 56, 59]. High variation was seen in the number of PRP treatments and in the volume of obtained/applied PRP. The reporting of PRP protocols showed inconsistencies, especially in terms of platelet count or platelet concentrate. Merely, a few studies included these details when describing the PRP preparation and treatment process [19, 20, 22, 23, 27, 29, 31, 32, 33, 37, 42, 50, 52, 53]. PRP preparation methods of each included study are portrayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Preparation methods for PRP

| Authors | Vol | N | PRP | Centrifugation | A/A | FORM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction and wounds | ||||||

| Dhua et al. [15] | nm | 1 | nm | 1 × 20 min (3,000 rpm) | CaCI | Topical |

| 1 × 10 min (1,000 rpm) | ||||||

| Harper et al. [18] | 52 mL | 1 | nm | nm | Ca, Thrb | Gel |

| Helmy et al. [10] | nm | 4–6 | nm | 1 × soft spin | nm | Injection |

| 1 × hard spin | ||||||

| Hersant et al. [19] | 24–48 mL | 1 | 4–5 mL | 1 × 5 min (1,500 g) | Thrb | Glue |

| Hersant et al. [20] | 8 mL | 4 | 4.5 mL | 1 × 5 min (1,500 g) | nm | Injection |

| Moghazy et al. [11] | One unit | 1 | 5–10 mL | Twice | Thrb | Gel |

| Rainys et al. [12] | 8 mL | Mult | nm | RegenKit BCT | nm | Gel |

| Saad Setta et al. [13] | 10 mL | nm | nm | 1 × soft spin (1,007 g) | CaCl, Thrb | Gel |

| 1 × hard spin (447.5 g) | ||||||

| Slaninka et al. [17] | 10 mL | 1 | 2–3 mL | 1 × 10 min (3,600 rpm) | nm | Gel |

| Waiker and Shivalingappa [16] | 20 mL | 1 | 4–5 mL | 1 × 5 min (1,000 rpm) | nm | Topical |

| Xie et al. [14] | 20 mL | nm | 3 mL | 1 × 4 min (2,000 rpm) | CaCl, Thrb | Gel |

| 1 × 6 min (4,000 rpm) | ||||||

| Aesthetic | ||||||

| Hair growth | ||||||

| Abdelkader et al. [21] | 20 mL | − | 2 mL PRP | 1 × 5 min (101 g) | Yes | Solution |

| 1 × 5 min (280 g) | ||||||

| Gentile et al. [22] (used two different systems) | 18 mL/60 mL | 3 | 0.1 mL/cm2 | Cascade-Esforax/P.R.L. system 1 × 10 | Ca2+/no | Injection |

| min (1,100 g/1 × 10 min 1,200 rpm) | ||||||

| Ince et al. [23] | 40 mL nPRP | nm | 4–5 mL nPRP | nPRP: 1 × 15 min (3,000 rpm) | aPRP: CaCI | Injection |

| 10 mL aPRP | 4–5 mL aPRP | aPRP | ||||

| 1 × 5 min (200 rpm) | ||||||

| Kapoor et al. [26] | nm | 8 | 1.5 mL | nm | nm | Injection |

| Kumar et al. [24] | 20 mL | 5 | 2–4 mL | 1 × 5 min (2,000 rpm) | CaCl | Injection |

| 1 × 10 min (2,500 rpm) | ||||||

| Singh [25] | 25 mL | 6 | nm | nm | nm | Injection |

| Takikawa et al. [27] | 15 mL | 5 | 3 mL | 1 × 15 min (1,700 rpm) | nm | Injection |

| 1 × 5 min (3,000 rpm) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Face | ||||||

| Davis and Augenstein [28] | 30 mL | 1 | 1 mL | nm | CaCl | Injection |

| Hersant et al. [29] | 8 mL | 3 | 4 mL | 1 × 5 min (1,500 g) | nm | Injection |

| Powell et al. [31] | 450 mL | 1 | 7–8 mL | 1 × 5,600 rpm | CaCI, Thrb | Gel |

| 1 × 2,400 rpm | ||||||

| Vick et al. [30] | 20 mL | 1 | nm | 1 × 14 min | CaCI, Thrb | Gel |

|

| ||||||

| Hand surgery | ||||||

| Loibl et al. [33] | 15 mL | 2 | 1–2 mL | 1 × 4 min (1,500 rpm) | nm | Injection |

| Malahias et al. [34] | 20 mL | 2 | 2 mL | 2 × (10 min and 3,100 rounds in total) | No | Injection |

| Abdelsabor Sabah et al. [35] | 20 mL | 1 | 1 mL | 1 × 15 min (1,500 rpm) | nm | Injection |

| 1 × 10 min (3,500 rpm) | ||||||

| Uzun et al. [32] | 15 mL | 1 | 2 mL | 1 × 4 min (4,000 rpm) | nm | Injection |

|

| ||||||

| Burns | ||||||

| Gupta et al. [36] | nm | 1 | 5 mL/100 cm2 | 1 × 10 min (3,500 rpm) | nm | Film |

| Marck et al. [37] | 54 mL | 1 | nm | 1 × 15 min (3,200 rpm) | Thrb | Topical |

| Craniofacial plastic surgery | ||||||

| Chen et al. [38] | 30 mL | 1 | 3 mL | 1 × 10 min (2,000 rpm) | nm | |

| 1 × 10 min (2,200 rpm) | ||||||

| Gentile et al. [39] | 18 mL | 1 | nm | Cascade-Esforax system | Ca2+ | nm |

| Hanci et al. [40] | 8 cm3 | 1 | 0.6 mL | 1 × 20 min (1,000 g) | Photo- | Injection |

| 1 × 10 min (1,500 g) | activated | |||||

| Oyama et al. [41] | 40 mL | 1 | nm | 1 × 20 min (160 g) | nm | nm |

| 1 × 15 min (400 g) | ||||||

| Sakio et al. [42] | 34 mL | 1 | 3 mL | 1 × 5 min (2,650 g) | CaCl | nm |

| 1 × 10 min (90 g) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Lipofilling + PRP | ||||||

| Bilkay et al. [43] | 20 mL | 2 (m) | nm | 1 × 10 min (1,100 g) | CaCl | FG |

| Cervelli et al. [44] | 18 mL | 1–2 | nm | 1 × 10 min (1,100 g) | CaCI | FG |

| Fontdevila et al. [45] | 4–5 mL | 1 | nm | 1 × 8 min (1,800 rpm) | CaCI | FG |

| Gentile et al. [46] | 18 mL | 1 | 0.5 mL | 1 × 10 min (1,500 g) | Ca2+ | FG |

| Gentile et al. [47] | 18 mL | 1–2 | 0.5 mL | 1 × 10 min (3,300 rpm) | Ca2+ | FG |

| Majani and Majani [48] | nm | 1 | 1–8 mL | 1 × 8 min (1,800 rpm) | nm | FG |

| Mayoly et al. [49] | 18 mL | 1 | 2 mL | 1 × 10 min (3,200 rpm) | nm | FG |

| Rigotti et al. [50] | nm | nm | 1 mL | 1 × 5 min (300 g) | CaCI, Thrb | FG |

| 1 × 17 min (700 g) | ||||||

| Salgarello et al. [51] | 16–40 mL | 1–3 | 0.3 mL | 1 × 5 min (3,500 rpm) | CaCl | FG |

| Sasaki [52] | 54 mL | 1 | 2–2.5 mL | nm | No | FG |

| Sasaki [53] | 54 mL | 1 | 6–7 mL | Double spin | No | FG |

| Segreto et al. [54] | nm | 4 | 4 mL | nm | No | FG |

| Smith et al. [55] | 52 mL | 1 | 2.6 mL (m) | Angel PRP processing device | No | FG |

| Tenna et al. [56] | nm | 2 | 3 mL | RegenLab THT tube | nm | FG |

| van Dongen et al. [57] | 62 mL | 1 | 6 mL | nm | No | FG |

| Willemsen et al. [58] | 2 × 54 mL | 1 | 6 mL | 1 × 15 min (3,500 rpm) | Thrb | FG |

| Willemsen et al. [59] | 30 mL | 1 | 3 mL | Biomet GPS 3 device | nm | FG |

V, volume of whole blood drawn; N, number of PRP treatments; PRP, volume of PRP; A/A, activation/added components; FG, PRP added to fat graft for application; rpm, rounds per minute; g, relative centrifugational/g force; CaCl, calcium chloride; Thrb, thrombin; Ca2+, calcium; m, mean; nm, not mentioned.

Discussion

Reconstructive Surgery

According to Dhua et al. [15] and Waiker and Shivalingappa [16], PRP showed significantly better results in skin grafting when compared to conventional mechanical fixation. Graft loss, morbidity, and time of hospitalization were reduced. A particularly beneficial outcome was the occurrence of instant graft uptake in the PRP group.

PRP showed positive effects in wound treatment in all studies. Healing time and overall results in chronic leg ulcers were significantly better when treated with PRP, according to Helmy et al. [10]; furthermore, there was no reoccurrence in the treatment group (TG) in contrast to the eleven cases in the CG. Similar results were presented by Xie et al. [14] and Rainys et al. [12]. According to these studies, PRP can reduce wound size, induce granulation tissue formation, and shorten hospital stay, which leads to reduced costs for both patients and hospitals. PRP may also decrease pain in wounds, as described by Moghazy et al. [11]. They treated 40 patients suffering from “complex wounds” − defined as acute or chronic wounds that challenge medical teams in terms of treatment and healing − with either PRP gel or vacuum-assisted closure (VAC). The patients included in this study had suffered from pressure sores, burn injuries, venous ulcers, diabetic ulcers, surgical wounds, or traumatic wounds. The authors reported significantly lower VAS scores and shorter, but nonsignificant, duration of hospital stays in the PRP group. However, the PRP group showed inferior results in reduction rates concerning the amount of wound exudate when compared to VAC treatment.

The effects of PRP in scar treatment and breast reconstructive surgery were not as conclusive. Hersant et al. [20] reported complete remission in 53% of keloids treated with PRP; however, 29% showed complete relapse. PRP seemed to have a significant beneficial effect on pruritus severity and the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS) score, which may indicate that PRP is an effective method in scar treatment. The same authors described the efficacy of PRP in breast reduction and limb lifting surgery [19]. Patients treated with PRP showed significantly less hematoma and seroma than the CG; however, this effect was not observed in abdominoplasty patients. The scar quality did not improve in the TG. In contrast, PRP did not show any favorable results in breast reconstruction with a latissimus dorsi flap performed by Harper et al. [18], and no reduction of hematoma or seroma formation was reported compared to the CG.

Aesthetic Surgery

Hair Growth

PRP appears to be a safe and suitable alternative in managing hair loss, according to all studies collected for this review. The most relevant factors were hair regrowth, hair density, and hair count. Gentile et al. [22], Kumar et al. [24], and Singh [25] findings showed improvement in all mentioned parameters. However, the results were not always statistically significant and superiority over other therapeutic approaches, such as the plant derivate QR678 applied in the CS by Kapoor et al. [26], was not proven. In fact, intradermal QR678 injections resulted in higher hair density and shaft diameter. Adding growth factor carriers to PRP yielded similar yet not better results than injecting PRP alone. PRP may also serve as a preservation solution for hair transplantation, since Abdelkader et al. [21] reported higher hair graft uptake and accelerated hair growth in their RCT. No AEs occurred in connection with PRP injections in any of the studies, suggesting it is a safe treatment.

Face Lifting and Skin Rejuvenation

The outcomes of three studies by Davis and Augenstein [28], Hersant et al. [29], and Powell et al. [31] did not show significant results after applying PRP in rhytidectomy or facial rejuvenation. Hersant et al. [29] reported a major benefit for facial appearance and skin elasticity when combining PRP and hyaluronic acid (HA) as opposed to PRP or HA alone. These findings are consistent with a prospective study the authors published in 2017, indicating a positive synergistic effect of HA combined with PRP in cosmetic surgery [60]. Powell et al. [31] let three blinded surgeons evaluate the effects of the PRP application in rhytidectomy. Each facial side treated with PRP gel that showed less edema or ecchymosis than the control side was interpreted as a “positive” response; an “equal” response correlated with no noticeable difference and a “negative” response indicated the non-PRP side showed a better outcome. The treatment did receive some positive feedback from the judges, but no clinically significant difference compared to the control side was observed. Vick et al. [30] provided data suggesting PRP may reduce edema in blepharoplasty, since patients presented with less edema at day one and day thirty in the PRP group, but no significant clinical effects were reported. Similar to the findings of Powell et al. [31], ecchymosis was not reduced significantly, neither was postoperative discomfort. Overall, PRP alone does not seem to have major beneficial effects on aging correction or face lifts; however, further investigation of the combination of PRP and HA may yield more promising results. The studies showed that PRP therapy is safe, and any complications that occurred were minor and temporary. This corresponds to the results of a systematic review on PRP treatment for stria distensae performed by Sawetz et al. [61] in 2021. Their findings demonstrated that (multiple) PRP injections are a safe treatment option for stretch marks; however, the lack of comparability among the included reports made it impossible to draw clear conclusions about the efficacy of PRP in that field. This was due to a variety of limiting factors, a major one being the broad range of PRP preparation protocols, an issue we have come across in this review as well.

Hand Surgery

In a CS, Uzun et al. [32] reported the application of PRP in plastic surgery of the hand. Their research demonstrated that PRP is an effective method to reduce symptom severity and improve hand function in patients with mild CTS, judged by the Boston Carpal Tunnel Questionnaire (BCTQ). Three months after the procedure, BCTQ scores were significantly improved in the PRP group compared to the group that had received cortisone; however, this significance was no longer maintained after 6 months. The treatments showed equal improvements in sensory nerve conduction.

Recently, PRP has sparked interest in treating carpometacarpal arthritis of the thumb joint (CMC-1 arthritis). To our knowledge, only three studies have published studies investigating PRP injections for CMC-1 arthritis so far. PRP shows promising results in terms of pain decrease, according to Loibl et al. [33], Malahias et al. [34], and Abdelsabor Sabah et al. [35]. Intra-articular PRP injections can also result in improved function (measured via quick-disability of shoulder and hand questionnaire [DASH] or AUSCAN questionnaire), higher patient satisfaction, and more grip and pinch strength, as demonstrated by Malahias et al. [34] and Abdelsabor Sabah et al. [35]. The latter reported that these effects were no longer present at the second follow-up examination (3 months post-intervention), which does not correspond to the findings of Malahias et al. [34], who reported satisfactory result even after 1 year. This may be owed to the fact that Abdelsabor Sabah et al. [35] only performed one injection of 1 mL, whereas Malahias et al. [34] performed two intra-articular injections of 2 mL each. More extensive research in that field may yield further insight into the efficacy of PRP therapy for this condition and provide data to optimize frequency and volume of intra-articular PRP injections.

Burn Injuries

Similar to hand surgery, little evidence for PRP application in burn treatment is available. The randomized controlled studies by Gupta et al. [36] and Marck et al. [37] both investigated the addition of PRP to skin grafting for the treatment of burn wounds. Gupta et al. [36] demonstrated a significantly higher graft take and a lower complication rate, respectively, hematomas, compared to the CG. Marck et al. [37], conversely, did not report any significant benefit to graft adherence, re-epithelization rate, or scar quality in patients treated with PRP, and all observed effects were minor. However, the inhomogeneity of the study population may have been responsible for these findings. No serious complications were observed. Enhanced graft survival with PRP application in burn treatment was recently demonstrated by Zheng et al. [62] and published in the Chinese journal of burns. They recommend the use of PRP in skin grafting for burn injuries since their trial showed improved survival and fusion rates.

Due to the scarcity of current data in that field, no clear statement on the efficacy of PRP in burn treatment can be made. Further research in that area needs to be provided.

Craniofacial Surgery

PRP appears to be more efficient than arthrocentesis in treating TMJ disorders, as demonstrated by Hanci et al. [40]. Their results showed significantly better pain relief and decrease in pathological joint movement sounds, as well as improved range of motion (ROM). Gentile et al. [39] observed high patient satisfaction and low morbidity rate in patients undergoing maxillofacial surgery and PRP gel application. Pain levels and infection rates were reduced significantly. Also, applying platelet gel resulted in a 16% higher bone regeneration rate. PRP is believed to promote bone growth and soft tissue healing. This effect was observed a study by Oyama et al. [41]: CT imaging showed higher rate in regenerated bone volume after additional PRP treatment for alveolar bone grafting compared to the CG, indicating PRP in fact induces osteogenesis. These findings were not confirmed by Chen et al. [38] and Sakio et al. [42], who conducted similar studies, but did not report statistically significant benefits of adding PRP to the graft regarding newly formed bone volume. However, Chen et al. [38] did show less graft failure and a faster recovery in patients receiving the PRP-enhanced bone graft. Overall, the results presented no clear evidence about the effect of PRP in alveolar cleft surgery. Larger studies in a randomized controlled study design are necessary to evaluate the potential of PRP in craniofacial plastic surgery.

PRP as an Adjuvant to FG

The combination of PRP and lipofilling is based on the assumption that pro-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory effects of PRP enhance fat grafts [63]. The vascular component of PRP was demonstrated by Rigotti et al. [50], who observed higher vascular reactivity when adding PRP to facial lipofilling. It is also theorized that the growth factors released from the platelets induce proliferation and differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells), thereby further improving the graft outcome [63].

Cervelli et al. [44], Segreto et al. [54], and Smith et al. [55] evaluated the combination of PRP and FG for wound healing purposes, proving feasibility and safety. Pain reduction and over 50% complete healing rate were reported by Segreto et al. [54]; however, there was no CG to compare these results to. PRP-enhanced lipofilling appears to accelerate the re-epithelization process in ulcers compared to HA and collagen, according to Cervelli et al. [44]. Although Smith et al. [55] did not report any significant clinical improvement in their RCT, the authors concluded that the procedure was safe and recommended conducting larger randomized controlled studies to further evaluate the efficacy of PRP-enhanced FG in wound treatment.

PRP improves aesthetic perception and skin quality in scar treatment as demonstrated by Tenna et al. [56] and Majani and Majani [48]. Significant superiority over fat graft alone was not observed by the latter, but results were more durable with PRP.

The outcome of PRP-enhanced fat grafts in facial lipofilling procedures does not differ significantly from FG alone, according to Fontdevila et al. [45], Sasaki [52], and Willemsen et al. [59]. Nevertheless, PRP may still be of interest for cosmetic surgery since the RCT of Willemsen et al. [59] reported significantly shorter recovery in the PRP group. This may be attributed to the effect of PRP on fibroblast growth and differentiation. PRP-enhanced lipofilling is a safe procedure for gluteal augmentation, according to Willemsen et al. [58], and may even, as described in “PRP-enhanced fat graft augmentation of the calf region” by Bilkay et al. [43], reduce the number of sessions necessary to achieve satisfactory results. This effect was not observed in breast reconstructive surgery performed by Salgarello et al. [51], neither was a better clinical outcome in the PRP group when compared to the conventional Coleman technique, questioning the role of PRP in this field.

A few authors compared the effects of PRP in lipofilling to those of stromal vascular fraction (SVF) as an adjuvant to FG. van Dongen et al. [57] and Sasaki [53] provided data suggesting PRP is equally effective in facial lipofilling compared to SVF. The outcome of two studies by Gentile et al. [46, 47] demonstrates significantly higher graft maintenance in breast reconstruction and scar therapy for both PRP- and SVF-enhanced lipofilling; however, PRP showed slightly better results in both studies. These findings support PRP efficacy in lipofilling and may indicate superior effects of PRP over SVF as an adjuvant in FG.

As previously mentioned, the application of PRP in plastic surgery of the hand is a relatively unexplored field. Mayoly et al. [49] performed intra-articular injection PRP and microfat on 3 patients with radio-carpal osteoarthritis and proved feasibility and safety for this procedure. Preliminary results showed positive short-term outcomes, indicating a potential efficacy which should be explored on a greater scale (more patients, longer follow-up periods).

Limitations

There are some limitations to this review. Many studies had different endpoints or different evaluation approaches, and in some cases, the primary and secondary endpoints were not clearly defined. This posed a challenge in comparing and analyzing results. The previously mentioned (nm) heterogeneity in PRP preparation and application must be taken into account as well. The considerable variations in PRP extraction, activation, and frequency of application can lead to significant discrepancies between study results and diminish comparability. Furthermore, the vast majority of the authors did not disclose the final platelet concentration and the platelet count in their report.

The issue of high variation in PRP preparation protocols has been addressed on several occasions [3, 4, 5]. One of the contributing factors is the broad range of suggested classification systems. Historically, Dohan Ehrenfest et al. [65] provided the first classification system in 2009. They suggested dividing platelet-rich preparations according to their contents − whether they contain leucocytes or not − and the density of the fibrin network: [2]

• P-PRP: leucocyte-poor, low-density fibrin network (pure PRP).

• L-PRP: leucocyte-rich, low-density fibrin network (leucocyte-rich PRP).

• P-PRF: leucocyte-poor, high-density fibrin network (pure PRF).

• L-PRF: leucocyte-rich, high-density fibrin network (leucocyte-rich PRF).

Other authors support labeling different PRP products according to the DEPA classification by Magalon et al. [67] which is based on the dose of injected platelets, the efficiency of the production (percentage of platelets retrieves from blood), the purity of PRP (ratio of platelets compared to red and white blood cells), and the activation process [2].

Mishra's classification, which has mainly gained recognition in sports medicine, separates PRP into four groups, mainly focusing on the platelet concentration and the presence of leucocytes [8]. In 2017, Lana et al. [8] proposed a new classification system called MARSPILL − an acronym for Method, Activation, Red blood cells, Spin, Platelet number, Image guidance, Leucocytes, Light activation − which provides a precise description of the most important steps in PRP preparation and pays special attention to the peripheral blood mononuclear cell component of PRP preparation. The authors argued that the presence of peripheral blood mononuclear cells has a crucial impact on the regenerative potential of PRP and that its quantity should therefore be the main focus in labeling PRP products [8]. The issue of confusing terminology and varying PRP preparation methods has been addressed by many authors, such as Everts et al. [64]. The authors pointed out that the magnitude of PRP products and the lack of detailed bioformulation descriptions contribute to inconsistent patient outcomes [64].

The different approaches and the lack of a categorization standard pose a problem in interpreting and comparing data. Standardized terminology, guidelines for the preparation protocols of PRP and other platelet products, and consistent and detailed reporting of said protocols would facilitate conducting − and analyzing − research in this field [2].

Conclusion

PRP therapy is widely used in plastic surgery, and numerous trials have investigated its effects in reconstruction, cosmetic surgery, burn treatment, hand surgery, and bone or FG. The majority of the literature focuses on the benefits of PRP in reconstructive and aesthetic surgery. Its use in hand surgery or burn treatment has only been reported by a small number of studies. Particularly good outcomes of PRP treatment can be achieved in wound healing and pain reduction. Since no serious complications or side effects are associated with PRP application, PRP presents a safe treatment option in the field of autologous blood products.

Even though several beneficial effects of PRP were identified, the evidence presented in current studies is conflicting and treatment regimens and evaluation methods show considerable heterogeneity. Moreover, PRP preparation protocols differ between one another and are often only partially disclosed.

The use of PRP shows promising results and is certainly justified in some areas, but its efficacy has not been proven in all fields of application. Further prospective randomized controlled studies with standardized preparation protocols and treatment regimens should be conducted to determine the efficacy of PRP in plastic surgery.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors received no financial support for this article.

Author Contributions

All authors provided meaningful input in the development and design of this work, or the analysis and interpretation of data for the work and the drafting of the work or revising the intellectual content.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study were obtained from online databases (PubMed, Ovid, Web of Science), journal websites, or other research platforms where restrictions or charges may apply. Such dataset may be requested from the respective journals or by contacting the authors directly.

References

- 1.Sommeling CE, Heyneman A, Hoeksema H, Verbelen J, Stillaert FB, Monstrey S. The use of platelet-rich plasma in plastic surgery: a systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013 Mar;66((3)):301–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alves R, Grimalt R. A review of platelet-rich plasma: history, biology, mechanism of action, and classification. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018 Jan;4:18–24. doi: 10.1159/000477353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie X, Zhang C, Tuan RS. Biology of platelet-rich plasma and its clinical application in cartilage repair. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014 Feb;16:204. doi: 10.1186/ar4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001 Dec;10((4)):225–8. doi: 10.1097/00008505-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chamata ES, Bartlett EL, Weir D, Rohrich RJ. Platelet-rich plasma: evolving role in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021 Jan;147((1)):219–30. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Motosko CC, Khouri KS, Poudrier G, Sinno S, Hazen A. Evaluating platelet-rich therapy for facial aesthetics and alopecia: a critical review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 May;141((5)):1115–23. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchmann S. Klinische anwendung von thrombozytenreichem plasma. Orthop Rheuma. 2020 Jun;23((3)):36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lana JFSD, Purita J, Paulus C, Huber SC, Rodrigues BL, Rodrigues AA, et al. Contributions for classification of platelet rich plasma: proposal of a new classification − MARSPILL. Regen Med. 2017 Jul;12((5)):565–74. doi: 10.2217/rme-2017-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alsousou J, Ali A, Willett K, Harrison P. The role of platelet-rich plasma in tissue regeneration. Platelets. 2013 May;24((3)):173–82. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2012.684730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helmy Y, Farouk N, Ali Dahy A, Abu-Elsoud A, Fouad Khattab R, Elshahat Mohammed S, et al. Objective assessment of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) potentiality in the treatment of chronic leg ulcer: RCT on 80 patients with venous ulcer. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021 Apr;20((10)):3257–63. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moghazy AM, Ellabban MA, Adly OA, Ahmed FY. Evaluation of the use of vacuum-asstisted closure (VAC) and platelet-rich plasma gel (PRP) in management of complex wounds. Eur J Plast Surg. 2015 Jul;38:463–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rainys D, Cepas A, Dambrauskaite K, Nedzelskiene I, Rimdeika R. Effectiveness of autologous platelet-rich plasma gel in the treatment of hard-to-heal leg ulcers: a randomized control trial. J Wound Care. 2019 Oct;28((10)):658–67. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2019.28.10.658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saad Setta H, Elshahat A, Elsherbiny K, Massoud K, Safe I. Platelet-rich plasma versus platelet-poor plasma in the management of chronic foot ulcers: a comparative study. Int Wound J. 2011;8((3)):307–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie J, Fang Y, Zhao Y, Cao D, Lv Y. Autologous platelet-rich gel for the treatment of diabetic sinus tract wounds: a Clinical Study. J Surg Res. 2020 Mar;247:271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhua S, Suhas TR, Tilak BG. The effectiveness of autologous platelet rich plasma application in the wound bed prior to resurfacing with split thickness skin graft vs. conventional mechanical fixation using sutures and staples. World J Plast Surg. 2019 May;8((2)):185–94. doi: 10.29252/wjps.8.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waiker VP, Shivalingappa S. Comparison between conventional mechanical fixation and use of autologous platelet rich plasma (PRP) in wound beds prior to resurfacing with split thickness skin graft. World J Plast Surg. 2015 Jan;4((1)):50–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slaninka I, Fibír A, Kaška M, Páral J. Use of autologous platelet-rich plasma in healing skin graft donor sites. J Wound Care. 2020 Jan;29((1)):36–41. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2020.29.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harper JG, Elliott LF, Bergey P. The use of autologous platelet-leukocyte-enriched plasma to minimize drain burden and prevent seroma formation in latissimus dorsi breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2012 May;68((5)):429–31. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e31823d2af0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hersant B, SidAhmed-Mezi M, La Padula S, Niddam J, Bouhassira J, Meningaud JP. Efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma glue in weight loss sequelae surgery and breast reduction: a Prospective Study. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4((11)):e871. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hersant B, SidAhmed-Mezi M, Picard F, Hermeziu O, Rodriguez AM, Ezzedine K, et al. Efficacy of autologous platelet concentrates as adjuvant to surgical excision in the treatment of keloid scars refractory to conventional treatments: a pilot Prospective Study. Ann Plast Surg. 2018 Aug;81((2)):170–5. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdelkader R, Abdalbary S, Naguib I, Makarem K. Effect of platelet rich plasma versus saline solution as a preservation solution for hair transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020 Jun;8((6)):e2875. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000002875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gentile P, Garcovich S, Bielli A, Scioli MG, Orlandi A, Cervelli V. The effect of platelet-rich plasma in hair regrowth: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015 Sep;4((11)):1317–23. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ince B, Yildirim MEC, Dadaci M, Avunduk MC, Savaci N. Comparison of the efficacy of homologous and autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for treating androgenic alopecia. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018 Feb;42:297–303. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-1004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar V, Sharma N, Mishra B, Upadhyaya D, Singh AK. To study the effect of activated platelet-rich plasma in cases of androgenetic alopecia. Turk J Plast Surg. 2020;29:28–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh S. Role of platelet-rich plasma in chronic alopecia areata: our centre experience. Indian J Plast Surg. 2015 Jan–Apr;48((1)):57–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.155271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapoor R, Shome D, Vadera S, Ram MS. QR 678 & QR678 neo vs PRP: a randomized, comparative, prospective study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020 Nov;19((11)):2877–85. doi: 10.1111/jocd.13398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takikawa M, Namakura S, Namakura S, Ishirara M, Kishimoto S, Sasaki K, et al. Enhanced effect of platelet-rich plasma containing a new carrier on hair growth. Dermatol Surg. 2011 Dec;37((12)):1721–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis A, Augenstein A. Amniotic allograft implantation for midface aging correction: a retrospective Comparative Study with platelet-rich plasma. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019 Jun;43:1345–52. doi: 10.1007/s00266-019-01422-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hersant B, SidAhmed-Mezi M, Aboud C, Niddam J, Levy S, Mernier T, et al. Synergistic effects of autologous platelet-rich plasma and hyaluronic acid injections of facial skin rejuvenation. Aesthet Surg J. 2021 Jun;41((7)):NP854–65. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjab061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vick VL, Holds JB, Hartstein ME, Rich RM, Davidson BR. Use of autologous platelet concentrate in blepharoplasty surgery. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Mar–Apr;22((2)):102–4. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000202092.73888.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powell DM, Chang E, farrior EH. Recovery from deep-plane rhytidectomy following unilateral wound treatment with autologous platelet gel: a Pilot Study. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001 Oct–Dec;3:245–50. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.3.4.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uzun H, Bitik O, Uzun Ö, Ersoy US, Aktaş E. Platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid injections for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2016;51((5)):301–5. doi: 10.1080/2000656X.2016.1260025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loibl M, Lang S, Dendl LM, Nerlich M, Angele P, Gehmert S, et al. Leukocyte-reduced platelet-rich plasma treatment of basal thumb arthritis: a Pilot Study. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:9262909. doi: 10.1155/2016/9262909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malahias MA, Roumeliotis L, Nikolaou VS, Chronopoulos E, Sourlas I, Babis GC. Platelet-rich plasma versus corticosteroid intra-articular injections for the treatment of trapeziometacarpal arthritis: a prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Cartilage. 2021 Jan;12((1)):51–61. doi: 10.1177/1947603518805230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abdelsabor Sabah HM, El Fattah RA, Al Zifzaf D, Saad H. A Comparative Study for different types of thumb base osteoarthritis injections: a Randomized Controlled Interventional Study. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2020 Dec;22((6)):447–54. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0014.6055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta S, Goil P, Thakurani S. Autologous platelet rich plasma as a preparative for resurfacing burn wounds with split thickness skin grafts. World J Plast Surg. 2020 Jan;9((1)):29–32. doi: 10.29252/wjps.9.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marck RE, Gardien KL, Stekelenburg CM, Vehmeijer M, Baas D, Tuinebreijer WE, et al. The application of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of deep dermal burns: a randomized, double-blind, intra-patient controlled study. Wound Repair Regen. 2016 Jul;24((4)):712–20. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen S, Liu B, Yin N, Wang Y, Li H. Assessment of bone formation after secondary alveolar bone grafting with and without platelet-rich plasma using computer-aided engineering techniques. J Craniofac Surg. 2020 Mar–Apr;31((2)):549–52. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gentile P, Bottini DJ, Spallone D, Curcio BC, Cervelli V. Application of platelet-rich plasma in maxillofacial surgery: clinical evaluation. J Craniofac Surg. 2010 May;21((3)):900–4. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181d878e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanci M, Karamese M, Tosun Z, Aktan TM, Duman S, Savaci N. Intra-articular platelet-rich plasma injection for the treatment of temporomandibular disorders and a comparison with arthrocentesis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015 Jan;43((1)):162–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oyama T, Nishimoto S, Tsugawa T, Shimizu F. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in alveolar bone grafting. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004 May;62((5)):555–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sakio R, Sakamoto Y, Ogata H, Sakamoto T, Ishii T, Kishi K. Effect of platelet-rich plasma on bone grafting of alveolar clefts. J Craniofac Surg. 2017 Mar;28((2)):486–8. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bilkay U, Biçer A, Özek ZC, Gürler T. Augmentation of the calf region with autologous fat and platelet-rich plasma enhanced fat transplants: a comparative study. Turk J Plast Surg. 2020;29((5)):21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cervelli V, Gentile P, Grimaldi M. Regenerative surgery: use of fat grafting combined with platelet-rich plasma for chronic lower-extremity ulcers. Aesth Plast Surg. 2009 Jan;33((3)):340–5. doi: 10.1007/s00266-008-9302-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fontdevila J, Guisantes E, Martínez E, Prades E, Berenguer J. Double-blind clinical trial to compare autologous fat grafts versus autologous fat grafts with PDGF: no effect of PDGF. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014 Aug;134((2)):219e–30e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gentile P, Orlandi A, Scioli MG, Di Pasquali C, Bocchini I, Curcio CB, et al. A Comparative Translational Study: the combined use of enhanced stromal vascular fraction and platelet-rich plasma improves fat grafting maintenance in breast reconstruction. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2012 Apr;1((4)):341–51. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2011-0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gentile P, De Angelis B, Pasin M, Cervelli G, Curcio CB, Floris M, et al. Adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction cells and platelet-rich plasma: basic and clinical evaluation for cell-based therapies in patients with scars on the face. J Craniofac Surg. 2014 Jan;25((1)):267–72. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000436746.21031.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Majani U, Majani A. Correction of scars by autologous fat graft and platelet rich plasma (PRP) Acta Med Mediterr. 2013;28:99–100. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mayoly A, Iniesta A, Curvale C, Kachouh N, Jaloux C, Eraud J, et al. Development of autologous platelet-rich plasma mixed-microfat as an advanced therapy medicinal product for intra-articular injection of radio-carpal osteoarthritis: from validation data to preliminary clinical results. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Mar;20((5)):1111. doi: 10.3390/ijms20051111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rigotti G, Charles-de-Sá L, Gontijo-de-Amorim NF, Takiya CM, Amable PR, et al. Expanded stem cells, stromal-vascular fraction, and platelet-rich plasma enriched fat: comparing results of different facial rejuvenation approaches in a clinical trial. Aesth Surg J. 2016 Mar;36((3)):261–70. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salgarello M, Visconti G, Rusciani A. Breast fat grafting with platelet-rich plasma: a comparative Clinical Study and current state of the art. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Jun;127((6)):2176–85. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182139fe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sasaki GH. The safety of efficacy of cell-assisted fat grafting to traditional fat grafting in the anterior mid-face: an indirect assessment by 3D imaging. Aesth Plast Surg. 2015 Dec;39((6)):833–46. doi: 10.1007/s00266-015-0533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sasaki GH. A preliminary clinical trial comparing split treatments to the face and hand with autologous fat grafting and platelet-rich plasma (PRP): a 3D, IRB-Approved Study. Aesthet Surg J. 2019 May;39((6)):675–86. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjy254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Segreto F, Marangi GF, Nobile C, Alessandri-Bonetti M, Gregorj C, Cerbone V, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma and modified nanofat grafting in infected ulcers: technical refinements to improve regenerative and antimicrobial potential. Arch Plast Surg. 2020 May;47((3)):217–22. doi: 10.5999/aps.2019.01571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith OJ, Leigh R, Kanapathy M, Macneal P, Jell G, Hachach-Haram N, et al. Fat grafting and platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a feasibility-randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2020 Jul;17((4)):1578–94. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tenna S, Cogliandro A, Barone M, Panasiti V, Tirindelli M, Nobile C, et al. Comparative study using autologous fat grafts plus platelet-rich plasma with or without fractional CO2 laser resurfacing in treatment of acne scars: analysis of outcomes and satisfaction with FACE-Q. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017 Jan;41:661–6. doi: 10.1007/s00266-017-0777-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Dongen JA, Boxtel J, Willemsen JC, Brouwer LA, Vermeulen KM, Tuin AJ, et al. The addition of tissue stromal vascular fraction to platelet-rich plasma supplemented lipofilling does not improve facial skin quality: a prospective randomized clinical trial. Aesthet Surg J. 2021 Aug;41((8)):NP1000–13. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjab109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Willemsen JC, Lindenblatt N, Stevens HP. Results and long-term patient satisfaction after gluteal augmentation with platelet-rich plasma-enriched autologous fat. Eur J Plast Surg. 2013 Sep;36:777–82. doi: 10.1007/s00238-013-0887-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Willemsen JCN, Van Dongen J, Spiekman M, Vermeulen KM, Harmsen MC, van der Lei B, et al. The addition of platelet-rich plasma to facial lipofilling: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Feb;141((2)):331–43. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hersant B, SidAhmed-Mezi M, Niddam J, La Padula S, Noel W, Ezzedine K, et al. Efficacy of autologous platelet-rich plasma combined with hyaluronic acid on skin facial rejuvenation: a prospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77((3)):584–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sawetz I, Lebo PB, Nischwitz SP, Winter R, Schaunig C, Brinskelle P, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for striae distensae: what do we know about processed autologous blood contents for treating skin stretchmarks? A systematic review. Int Wound J. 2021 Jun;18((3)):387–95. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng JS, Liu SL, Peng XJ, Liu XF, Yu L, Liang SQ. [A prospective study of the effect and mechanism of autologous platelet-rich plasma combined with meek microskin grafts in repairing the wounds of limbs in severely burned patients] Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2021 Aug;37((8)):731–7. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501120-20200427-00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Picard F, Hersant B, La Padula S, Meningaud JP. Platelet-rich plasma-enriched autologous fat graft in regenerative and aesthetic facial surgery: technical note. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017 Sep;118((4)):228–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Everts P, Onishi K, Jayaram P, Lana JF, Mautner K. Platelet-rich plasma: new performance understandings and therapeutic considerations in 2020. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Oct;21((20)):7794. doi: 10.3390/ijms21207794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet- rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L- PRF) Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27((3)):158–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mishra A, Harmon K, Woodall J, Vieira A. Sports medicine applications of platelet-rich plasma. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13((7)):1185–95. doi: 10.2174/138920112800624283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Magalon J, Chateau AL, Bertrand B, Louis ML, Silvestre A, Giraudo L, et al. DEPA classification: a proposal for standardizing PRP use and retrospective application of available devices. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2016;2((1)):1–5. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2015-000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study were obtained from online databases (PubMed, Ovid, Web of Science), journal websites, or other research platforms where restrictions or charges may apply. Such dataset may be requested from the respective journals or by contacting the authors directly.