Abstract

Background

The emergence of widespread drug-resistant strains of the malaria parasites militates against strives for more potent antimalarial drugs.

Aim

The present study evaluated the antimalarial activity of A. africana ethanolic crude extract in vitro and in vivo against Plasmodiumberghei -infected mice in anticipation of acquiring scientific evidence for it used by mangrove dwellers to treat malaria in Ghana.

Methodology

The pulverized dried leaves were extracted with 70% ethanol (v/v) and screened for phytochemicals using standard protocols. The in vitro antimalarial activity was investigated against chloroquine-sensitive Plasmodium falciparum (Pf3D7 clones), MRA-102, Lot:70032033, via SYBR® Green I fluorescent assay method using positive control Artesunate (50–1.56 × 10−3 μg/mL). In the in vivo studies, doses (200–1500 mg/kg) of AAE were used in the 4-day suppressive and curative tests, using P. berghei-infected mice. Artemether/lumefantrine (1.14 mg/kg) and normal saline were used as positive and negative control respectively.

Results

The phytochemical analysis revealed the presence of alkaloids, saponins, flavonoids, glycosides, tannins, terpenoids and phytosterols. The extract showed an IC50 of 49.30 ± 4.40 μg/mL in vitro and demonstrated complete parasite clearance at dose 1500 mg/kg in vivo with a suppressive activity of 100% (p < 0.0001) in the 4-day suppressive test. The extract demonstrated high curative activity (p < 0.0001) at 1500 mg/kg with 100% parasite inhibition and the oral LD50 > 5000 mg/kg in mice.

Conclusion

The results demonstrated that A. africana crude extract has antimalarial activity both in vitro and in vivo supporting the traditional use of the plant to treat malaria.

Keywords: Avicennia africana, Malaria, Plasmodium, Phytochemicals, Toxicity

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Traditionally, Avicennia species have been used as medicine for wide array of diseases including malaria worldwide.

-

•

A. africana ethanolic leaf extract has antimalarial activity against 3D7 P. falciparum strain (in vitro) and P. berghei (in vivo).

-

•

No potential toxicity signs were observed in all the mice demonstrating how safe the extract is.

List of abbreviation

- PCV

Packed cell volume

- MST

Mean survival time

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- AAE

Avicennia africana extract

- FACS

Flow cytometers

- pRBCs

Parasitized Red Blood Cells

- NMIMR

Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1 piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- CPM

Complete parasite medium

- DMSO

Dimethyl Sulfoxide

- RPMI

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

1. Introduction

Malaria continues to pose a great threat to humankind and presents a significant public health problem. Most of the 409,000 deaths registered globally in 2019 were caused by the ravaging effect of malaria, with most of the deaths occurring in Africa.1 Plasmodium parasite growth and multiplication are facilitated by both the female Anopheles mosquito vector and the human host. Plasmodium falciparum, P. ovale, P. malariae, P. vivax, and P. knowlesi are the parasites linked with the infection. P. falciparum, on the other hand, has been identified as the most prevalent parasite type in Sub-Saharan Africa.2 Malaria is undoubtedly endemic in Ghana. In spite of efforts to reduce its morbidity and mortality, the disease remains high, resulting in an economic and social burden.3,4

The emergence of drug-resistant parasite strains undermines efforts to develop effective antimalarial drugs,5 especially, in the absence of a clinical vaccine. Chemotherapy and chemoprophylaxis continue to be the cornerstones of disease management in Ghana.6 Artemisinin-based combination therapy is still first-and second-line treatment option for malaria treatment.2 Reports have suggested that over 80% of the global population depend on plant medicine for their basic health care needs.7,8 In particular, over 70% of Ghanaians significantly depend on plant-based medicine.9 This might be attributed to socio-cultural practices that have resulted in a strong preference for herbal remedies over modern scientific medication. This might also explain why the majority of people in Sub-Saharan Africa have an intense desire and inclination for plant or herb-based medicine for the maintenance of their health.10,11

A. africana, also known as black or olive mangrove, is one of the eight well-known species of genus Avicennia, it is a mangrove plant that is found in intertidal sections of seabeds, estuaries, rivers, and streams with a worldwide distribution.12 It has been speculated that various parts of the plant have many ethnomedicinal uses. A recent report suggested that the plant is used to treat various diseases, including malaria, asthma, diabetes, cancer, rheumatism, smallpox, ulcers, thrush, gangrenous wounds, and ringworm.12 Traditional medicinal plants and their products have a long folkloric history of usage, which contributes to their perceived efficacy.13 Consequently, previous phytochemical screening revealed the presence of different bioactive compounds, with a high concentration of alkaloids and saponins considered a notable prospective natural source for therapeutic compounds due to their diverse biological activities.14

Our investigation indicated that the plant has not been scientifically evaluated for its antimalarial efficacy, resulting in a knowledge gap due to a lack of evidence-based data. Hence, the present study sought to screen for the phytochemical constituents of the plant and evaluate the antimalarial activity of a 70% ethanol (v/v) crude extract of A. africana leaves using in vitro assays. Additionally, the efficacy of the extract was tested in vivo using a 4-day suppressive and curative test in mice infected with P. berghei (ANKA) strains.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and chemicals

Fehling's solutions (A and B), 1% gelatin, 20% sodium hydroxide, ammonia solution, and Dragendorff's reagents were prepared from stock reagents obtained from Merck Chemical Supplies (Darmstadt, Germany). Giemsa (Science Lab, USA), hydrochloric acid, absolute methanol chloroform, sulphuric acid, acetic anhydride, lead acetate, and ferric chloride were obtained from Merck Chemical Supplies (Darmstadt, Germany). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Qualikems Lab reagents, India), Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1940 (RPMI-1940), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1 piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), NaHCO3, Artesunate, l-glutamine, gentamycin, glucose, and Albumax II were procured from Sigma Aldrich (Germany). All reagents were of analytical quality.

2.2. Plant collection and identification

Leaves of A. africana were collected at Iture near Elimina, Cape Coast in the Central Region of Ghana in November 2018. The area lies within latitude N 5° 5̍ 55.122̎ North of the equator and Longitudes W 1° 19̍ 22.277̎ West of the Greenwich Meridian, and runs along the University of Cape Coast's coastal border. The plant was identified and authenticated by a botanist and a voucher specimen (CC3096) was deposited for future reference at the Herbarium of the Department of Environmental Science, School of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Coast.

2.3. Plant extraction

The matured plant leaves were thoroughly washed and shade-dried at room temperature and were pulverized into a coarse powder. A total of 900 g pulverized of the plant material was extracted by cold maceration [150 g of powdered material in 800 mL of 70% ethanol (v/v)] for 72 h. The filtrate was concentrated using a rotary evaporator (R-114 SABITA) at 45 rpm and 40 °C to obtain the crude extract (AAE). The gummy crude extract was kept in a desiccator with activated silica gel at room temperature for 72 h. However, the plant material residues were sequentially re-macerated (3x) to increase yield. The crude extract (178.06 g) representing a yield of 19.78% was stored in a freezer at −20 °C until used.

2.3.1. HPLC analysis of crude ethanolic extract of A. africana

The ethanolic extract (0.2 g) of A. africana was dissolved in methanol (10 mL) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. and then filtered through Whatman No.1 filter paper using a high-pressure vacuum pump. The sample was diluted to 1:10 with the sample solvent. The HPLC method was performed according to the procedure described by Sharma et al., (1993)15 with slight modifications on a Shimadzu LC-20 AD HPLC system, equipped with a model LC- 20 AV pump, UV detector SPD-20AV, Rheodyne fitted with a 5 μL loop, lab solution and auto injector SIL-20AC. The column was a hyper CTO-10AS C-18 100 column (4.6 150 nm, 3 m size). The elution was carried out with gradient solvent systems with a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min at ambient temperature (40 °C). The mobile phase was consisted of 0.1% v/v acetic acid (solvent A) and Acetonitrile (solvent B). The mobile phase was prepared fresh, filtered through a 0.45 μm filter and solicited before use. The solvent gradient was performed by varying the proportion of solvent B (Acetonitrile) to solvent A (1% acetic acid in water (v/v)) as follows: initial 60% A; 0–0.01 min, 60% A; 4.1 min, 100% A; 15 min, 100% A; 33.0 min and finally 60% A for 33.1 min. The total running time was 60 min. The sample injection volume was 5 μL while the wavelength of the UV–vis detector was set at 212 nm. The identification of alkaloids fingerprint in the sample was done by retention time.

2.4. Parasites used for In vitro and In vivo antimalarial studies

In the in vivo studies, the chloroquine-sensitive P. berghei (ANKA) strain, MRA-311 with Lot no. 64498867, was secured from the Immunology Department, Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR), University of Ghana, Legon, Accra. As recounted by Moll et al. (2008),16 the glycerolyte-frozen stabilate was thawed and washed using 12% NaCl and 1.6% NaCl, and subsequently washed in PBS per the washing procedures. An aliquot of 0.2 mL of inoculum (2.0 μL washed blood in 50 mL of PBS) was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) into uninfected mice. The parasites were maintained by a serial passage from naïve female donor mice to uninfected mice. A standard inoculum (1 × 107 parasitized RBC) was used to inject (0.2 mL) the experimental mice intraperitoneally. Additionally, the extract's efficacy was evaluated on a 3D7 chloroquine-sensitive strain of P. falciparum maintained in continuous culture, as described by Trager and Jensen (1980).17

2.5. Experimental animals

Adult ICR mice (17–30 g) of both sexes were used. The animals were procured from the University of Ghana Medical School (Animal unit), Korle-Bu, Accra, Ghana. They were allowed 7 days to adjust to the laboratory conditions before the start of the experiment. The mice were kept in plastic cages under standard laboratory conditions of 25 ± 5 °C and a 12 h light/dark cycle, and they were fed commercial feed and water ad libitum. The experiment protocol, as well as the handling of the animals, were done according to the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.18 The study protocols were validated by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cape Coast. Ghana.

2.6. Phytochemical screening

Preliminary phytochemical evaluation (qualitative) was done on the A. africana crude extract (AAE) to detect the presence of bioactive constituents in the plant, using standard methods as described by Wadood et al. (2013),19 Safowora (1993)20 and Evan & Trease (2002).21

2.7. Acute toxicity study

The LD50 was determined earlier using adult mice, with a modified method of Nafiu et al. (2021)22 and Orabueze et al. (2020).23 Six groups of animals were involved. A single dose of AAE (100, 300, 1000, 3000 and 5000 mg/kg)24 was orally administered to each mouse in all five groups of five mice while the negative group received only distilled water. The animals were observed for toxicity signs, distress or mortality up to 14 days.

2.8. In vitro antimalarial assay

2.8.1. Culturing and maintenance of 3D7 Plasmodium falciparum

As previously described by Trager and Jensen (1980),17 a chloroquine-sensitive strain of P. falciparum (Pf 3D7) was kept in continuous culture. The parasites were cultivated in O Rh+ RBC using a complete parasite medium, which was composed of RPMI 1640, supplemented with HEPES, NaHCO3, l-glutamine, gentamycin, glucose and Albumax II.25 Importantly, the following incubation conditions such as 5.5% CO2, 2% O2 and 92.5% N2 of the mixture gas, were adhered to in the experiment. The parasites cultivated in O Rh+ were kept in the incubator with daily media change till parasitaemia of more than 4% was obtained. Treating the culture with 5% sorbitol resulted in the synchronization of ring-stage P. falciparum. The parasitaemia was reduced to 1% after 48 h of synchronization.

2.8.2. Preparation of plant crude extract

A weight of 10 mg of the crude extract was dissolved in 1 mL of 100% DMSO, and vortexed to obtain a homogeneous concentration of 10 mg/mL (stock).

The stock was then diluted further with CPM to achieve a concentration of 1000 μg/mL (0.1% DMSO) (AAE) before being filtered into fresh sterile tubes. Artesunate was used as the positive standard drug and was diluted with CPM to a concentration of 1000 × 10−3μg/mL.26,27 The crude extract (AAE) was solubilized in normal saline to obtain a concentration of 1500 mg/kg for the in vivo investigations. From this concentration, a serial dilution was prepared to achieve dose levels of 1000, 600, 400 and 200 mg/kg. The calculation of dose levels was based on the bodyweight of each mouse.

2.8.3. In vitro parasite growth inhibition assay

The crude extract was tested for anti-plasmodia activity using the SYBR Green I fluorescence assay as described by Smilktein et al. (2004).28 In a nutshell, the working solution (AAE) [1000 μg/mL (0.1% DMSO)] was serially diluted (100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, and 3.125 μg/mL) for treatment, while the artesunate (reference drug) was diluted from 50 to 1.56 × 10−3 μg/mL. The test wells (96-well tissue culture plate) were initially seeded with 90 μL of ring-stage (synchronized) pRBCs (1% parasitaemia), CPM and packed RBCs at 2% haematocrit. An aliquot of 10 μL of the AAE was dispensed into each well in triplicate. However, wells containing RBCs (2% haematocrit), parasitized RBCs (pRBCs) and CPM served as negative and blank controls respectively. The plate was then incubated for 48–72 h. An aliquot of 100 μL of 4x buffered SYBR Green I (0.20 μL of 10,000X SYBR Green I/mL of 1x phosphate buffer saline) was added for a further 30 min at 37 °C. The presence and amount of pRBCs were detected using the Guava EasyCyte HT FACS machine (Millipore, USA) and parasitaemia was recorded in percentage. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was extrapolated from non-linear regression curves of percentage inhibition versus log-concentration curves from Graph Pad Prism 7.00 using algorithms obtained from flow cytometers (FACS) data.

2.9. In vivo antimalarial test

2.9.1. Preparation of standard inoculum and parasite inoculation

A mouse infected with Plasmodium berghei (ANKA) and with a parasitaemia of 44% was used as a donor. The mouse was thereafter euthanised and the blood collected (cardiac puncture) into an EDTA vacutainer tube. The blood sample was diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (0.9%) based on the parasitaemia level of the donor mouse and the RBC count of a normal mouse to achieve a suspension of 5 × 107 infected RBCs per millilitre.29 Each experimental animal received 200 μL (0.2 mL) of blood containing 1.0 × 107 parasitized RBCs intraperitoneally.

2.9.2. Grouping of experimental animals

Out of the seventy (70) P. berghei-infected mice, thirty-five (35) mice were used for the 4-day suppressive test. In this test, the animals were grouped into seven (7) groups of five animals each. Groups I, II, III, IV, and V animals were treated with AAE (200, 400, 600, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg), respectively, as proposed by Mzena, Swai & Chacha (2018).30 Groups VI and VII animals served as a negative control (normal saline-2 ml/kg) and positive control (Artemether/Lumefantrine-1.14 mg/kg). In the curative test, the remaining infected mice (35) were used to assess the curative effect of the extract. In this study, the animal groupings, dose treatment, and controls used were similar to the 4-day suppression test as described earlier.

2.9.3. Suppressive test

A modified Peters' 4-day suppressive test was used to establish the efficacy of the crude extract on early malarial infection against P. berghei in mouse models.31,32 In this experiment, 3 h after infection on day zero (D0), the animals were treated with various dose levels (200, 400, 600, 1000, and 1500 mg/kg) daily. The reference drug group received Artemether/Lumefantrine-1.14 mg/kg while the negative control group was dosed with normal saline-2 ml/100 g. The oral administration of the AAE extract to treatment groups as well as Art/Lum and normal saline continued daily for four consecutive days (D0 to D3). On day-4 (D4), tail blood was collected and blood smears were prepared for each animal in all the groups.

The thin blood smears were fixed in absolute methanol for 2 min, stained with 10% Giemsa in physiological saline at a pH of 7.2 for 20 min, and examined at 100X with a light microscope to determine parasitaemia. The number of parasitized RBCs counted divided by the total number of RBCs multiplied by 100 gave the percent parasitaemia. Additionally, the mean parasitaemias were used to compute the percent (%) suppression by utilizing the following formulae.

Where A = mean parasitaemia of negative control.

B = mean parasitaemia of AAE extract-treated group

2.9.4. The curative test

The extract's curative effect on established malaria infection in the mice was evaluated using the technique illustrated by Ryley and Peters, (1970).32 In this study, the infected mice (35) were similarly grouped as described earlier in the 4-day suppressive test. Here, 96 h after intraperitoneal inoculation of the parasites, baseline parasitaemia (D4) was determined to confirm infection. Five groups were given AAE orally once daily for five successive days with different dose levels (200–1500 mg/kg). The reference drug and negative control groups were treated with Art/Lum 1.14 mg/kg and normal saline (2 ml/100 g) respectively. The parasitaemia level was monitored on day-6 (D6), two days into treatment, and in the post-5-day treatment period (D9). A comparison was made of the baseline parasitaemia (D4), Day-6 (D6) and post-treatment Day-9 (D9) after the 5-day treatment period to establish the curative effect of the extract in the infected mice.

2.9.5. Mean survival time (MST)

The mean survival time (MST) was arithmetically determined by calculating the mean survival time (in days) for 30 days (D0 to D29). A total of 35 mice were observed for mortality from the inoculation day (D0) to post-inoculation of parasites (D29).

2.9.6. Evaluation of haematocrit

Haematocrit was measured to assess the potency of the extract to prevent haemolysis, arising from the multiplication of the parasites in the red blood cells. To assess the anti-haemolytic effect of the extract, a point-of-care haemoglobin testing device, the BioAid® haemoglobin testing system, was used to measure the haematocrit of all the animals using tail blood. The measurement was done before extract administration (baseline), two days into treatment, and 24 h after the five successive days of extract treatment in the curative studies.

2.9.7. Statistical analysis

Analysis was done using GraphPad Prism, version 7.00 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was determined by applying one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's and Tukey's post-hoc multiple comparison tests. The data were presented as mean ± SEM with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative phytochemical screening of the extract

The qualitative phytochemical screening of A. africana plant materials (pulverized leaves) of 900 g with an extract yield of 19.784% revealed the presence of alkaloids, saponins, flavonoids, glycosides, true and condensed tannins, as well as terpenoids and phytosterols, but not cyanogenic glycosides (Table 1).

Table 1.

Phytochemical screening of A. africana crude extract.

| Phytochemicals | Results |

|---|---|

| Alkaloid | + |

| Flavonoids | + |

| Glycosides | + |

| Saponins | + |

| Cyanogenic glycosides | – |

| Terpenoids | + |

| Phytosterols | + |

| True tannins | + |

| Condensed tannins | + |

+ = Positive, - = Negative, tests were done in triplicate.

3.2. HPLC analysis of A. africana crude extract

The HPLC analysis of the crude ethanolic extract of A. africana revealed wide variability in its phytochemical content (Fig. 1). About twenty-seven (27) components of compounds were visualized in the form of peaks (Fig. 1).There are nine (9) prominent peaks with the retention times of 21.957, 22.640, 23.153, 23.987, 25.170, 25.854, 26.327, 27.491, and 31.740 min identified at a wavelength of 212 nm. All the 27 molecules were separated because of their unique chemistry and may all contribute to the biological efficacy of the extract. The compound with a retention time of 22.64 min has the highest sharp peak with a 35.5 mV intensity (Fig. 1.0), followed by the compound with a retention time of 26.327 min with a 33.0 mV intensity.

Fig. 1.

HPLC spectrum (A&B) of ethanolic extract of A. africana.

3.3. Acute toxicity study

There was no lethality of mice at all dose levels (AAE 100–5000 mg/kg single dose) tested within 24 h post-extract administration and the subsequent 14-days of observation. No potential toxicity signs such as respiratory distress, decrease in appetite, diarrhoea, salivation, vomiting, sedation, tremors, hair erection, or lacrimation were observed in all the mice. This finding suggests that the LD50 for A. africana crude extract in mice is greater than 5000 mg/kg, which is consistent with the findings of Muluye et al. (2021).33

3.4. In vitro antimalarial test

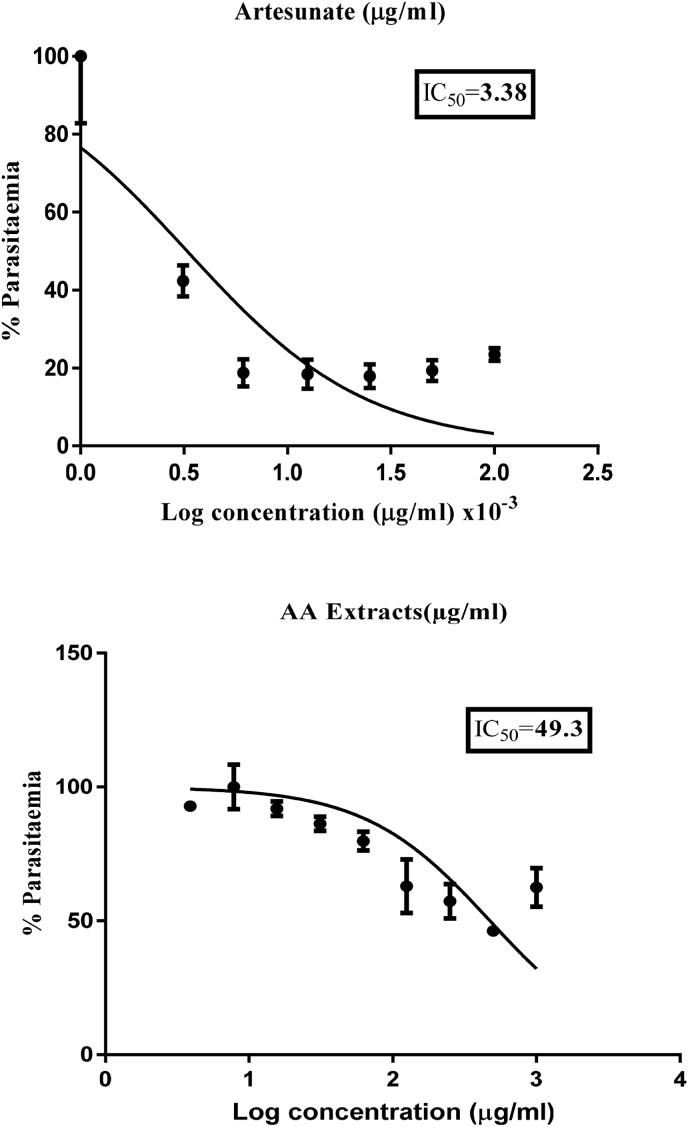

The antimalarial activity of AAE against P. falciparum (Pf3D7 strain) parasites showed varied IC50 values. The least IC50 obtained from the study was 44.90 μg/mL while the highest was 53.70 μg/mL, with a mean IC50 value of 49.30 ± 4.40 μg/mL (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Relatively, the reference drug (Artesunate) also showed IC50 values of 3.56 × 10−3 and 3.20 × 10−3 μg/mL from the in vitro tests conducted with a mean IC50 value of 3.38 × 10−3 ±0.18 μg/mL (Fig. 1 and Table 2). It is important to note that the antimalarial activities of extracts are considered ‘active’ when the IC50 is less than or equal to 50 μg/mL, as suggested by Ramazani et al. (2010).34 In the current study, the extract's mean IC50 value was 49.30 ± 4.40 μg/mL, indicating that the plant is active and has promising antimalarial activity. Table 2 shows the IC50 values obtained for Artesunate and A. africana after multiple treatments with P. falciparum (Pf3D7 strain). The resultant IC50 is expressed as an average ± SEM.

Fig. 2.

Concentration-response curves and IC50s of A. africana (leaf) crude extract and the reference drug (Artesunate) against P. falciparum (Pf3D7 strain).

Table 2.

Average IC50 for A. africana crude extract against P. falciparum (Pf3D7 strain).

| Treatments | IC50 (μg/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Mean | |

| Artesunate × (10−3) | 3.56 | 3.20 | 3.38 ± 0.18 |

| A. africana | 44.90 | 53.70 | 49.3 ± 4.40 |

3.5. In vivo antimalarial test

3.5.1. Effect of A. africana leaf extract on early malaria infection

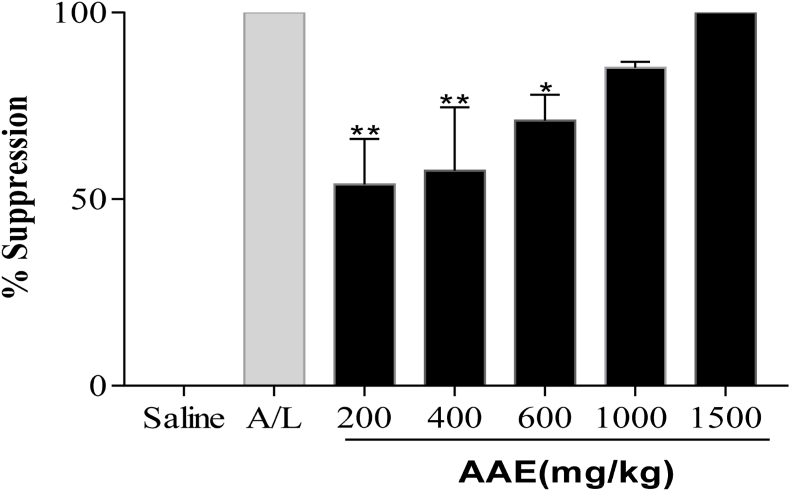

The 4-day suppression test showed that the AAE demonstrated a significant reduction (p < 0.05) in parasitaemia with a corresponding increase in chemo-suppression at all dose levels as opposed to the control groups. The extract significantly (p < 0.05) suppressed the parasites in vivo in a dose-dependent manner: (200 mg/kg; 16.14 ± 4.26; 53.98%), (400 mg/kg; 14.86 ± 5.96; 57.62%), (600 mg/kg; 10.17 ± 2.43; 71.01%), (1000 mg/kg; 5.18 ± 0.54; 85.21%) and (1500 mg/kg; 0.00 ± 0.00; 100.00%) (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 4aa). The reference drug (Art/Lum) caused complete suppression (100%), similar to the highest dosed animals mentioned above. The clearance of parasites in the blood was confirmed by micrographs of blood thin smears prepared on the 5th post-4-day suppressive test (Fig. 4a), indicating the total clearance of parasites in the 1500 mg/kg group of animals and the reference drugs animals compared to the negative control groups.

Fig. 3.

Effect of A. africana crude extract (AAE) on parasite density of P. berghei-infected ICR mice, indicating a decrease in parasitaemia from 200 mg/kg to 1500 mg/kg, compared to the negative control group (N. Saline- 10 ml/kg, Art/Lum-1.14 mg/kg). Data is expressed as Mean ± SEM, (n = 5), one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons.

Fig. 4.

Percentage parasite suppression against various concentrations of AAE leaf extracts and controls (N. Saline-10 ml/kg, Art/Lum- 1.14 mg/kg). The data show that the percentage of parasites suppressed in the four-day suppressive test is increasing. Data is presented as Mean ± SEM, using one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons.

Fig. 4a.

Comparing blood thin smears (micrographs) in confirmation of the extract's suppressive effect in the 4-day suppressive test, a:1500 mg/kg, b: Negative control (Normal saline) and c: Reference drug-A/L 1.14 mg/kg. Black arrows = parasitized RBCs (10% Giemsa stain, 1000X) in the 4-day suppressive test.

3.5.2. Effect of AAE on body weight and mean survival time in the four-day suppression

The extract did not cause a significant change in body weight in any of the extract-treated groups (p > 0.05), except the reference drug (Art/Lum) group, which showed a significant increase in body weight (weight gained) (p = 0.0108) in the 4-suppressive test. It was noticed that the mice's survival days increased with increasing dose level across groups, peaking at the highest dose of 1500 mg/kg (p < 0.0001), compared with the negative control group. In the 4-day suppressive test, the animals treated with AAE at 1500 mg/kg were protected for up to 24 days out of the 30 days (D0-D29) after drug treatment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bodyweight and survival time of P. berghei-infected mice treated with A. africana crude extract in the 4-day suppression test.

| Treatment | Weight (g) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/kg) | W0 | W4 | Survival time | |

| A. africana | 200 | 25.42 ± 2.06 | 25.44 ± 1.75 | 10.40 ± 1.40b3,c2 |

| 400 | 27.19 ± 0.55 | 26.36 ± 1.86 | 14.60 ± 1.28b2,a1 | |

| 600 | 27.79 ± 1.29 | 27.64 ± 1.52 | 15.60 ± 1.80b2,a1 | |

| 1000 | 25.07 ± 1.27 | 22.22 ± 1.72 | 19.00 ± 2.30b1,a1 | |

| 1500 | 20.37 ± 3.17 | 22.12 ± 4.68 | 24.00 ± 2.53a1 | |

| N. Saline (ml) | 10 | 24.92 ± 2.72 | 23.08 ± 3.38 | 6.60 ± 0.74b3 |

| Art/Lum | 1.14 | 28.94 ± 2.14 | 33.67 ± 1.53a1 | 30.00 ± 0.00 |

The results are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 5; acompared to normal saline treated group, bcompared to Artemeter-Lumefantrine, ccompared to 1500 mg/kg group, 1p < 0.05, 2p < 0.001, 3p < 0.0001. W0 = before extract treatment on day 0, W4 = post-treatment on day 4, W = weight.

3.5.3. Effect of AAE on established malaria infection (Rane's test)

The crude extract demonstrated a high curative power (p < 0.0001) at the highest dose level (1500 mg/kg) with a mean parasite count of 0.00 ± 0.00 (complete parasite clearance) and percentage inhibition of 100 ± 0.00 at the end of the five-day treatment period. Comparatively, the result of the dose level (1500 mg/kg) was similar to the reference drug (Art/Lum 1.14 mg/kg) group, with a complete parasite clearance and a percentage inhibition of 100 ± 0.00, while the mean parasitaemia in the untreated negative control group was 64.4 ± 3.10 as presented in Fig. 5. The total drug exposure across time (AUC) presented in Fig. 4b further explains the parasite's clearance in the curative studies. Additionally, micrographs from the blood smears of the 1500 mg/kg mice and the control groups presented in Fig. 5a confirmed complete clearance of parasites in 1500 mg/kg mice in Rane's test.

Fig. 5.

The percentage inhibition in parasites against treatment (dose levels) of extract (A. africana). The data represents mean parasitaemia in a time series (a) and AUC (b). Infection Day (D0), baseline parasitaemia (D4), two days into the treatment period (D6) and post-extract treatment (D9) parasitaemia.

Fig. 5a.

Comparison of micrographs of blood smears to confirm total parasite clearance in the curative test. a:1500 mg/kg (Pb-negative), b: Negative control (Pb-positive) and c: reference drug-A/L 1.14 mg/kg (Pb-negative). Black arrows represent parasitized RBCs, red arrow represent RBCs, and blue arrows represent leukocytes. (1000 × , 10% Giemsa stain).

3.5.4. Effect of A. africana on packed cell volume (PCV) in the curative test (Rane's test)

There was a significant reduction in PCV values across the treatment groups. A similar reduction (p < 0.05) was seen in the positive control group. However, the 1500 mg/kg extract-treated mice were found to prevent a reduction in PCV in the curative test, as no significant reduction (p > 0.05) in PCV values was observed. It is crucial to note (Table 4) that the reduction in PCV values may be associated with a decreasing trend in parasitaemia levels. Statistically, it appears that the haemolysis that was supposed to have been caused by rising levels of parasite density2 was rather a result of a decrease in parasitaemia from the least dosed group.

Table 4.

Packed Cell Volume (PCV) of P. berghei-infected mice treated with the crude AAE extract in Rane's test.

| Treatment | Packed Cell Volume (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/kg) | PCV4 | PCV9 | P value | |

| A. africana | 200 | 39.00 ± 1.04 | 22.00 ± 4.72∗ | 0.0377 |

| 400 | 36.00 ± 1.00 | 19.50 ± 1.50∗ | 0.0193 | |

| 600 | 37.00 ± 1.44 | 19.50 ± 0.64∗∗ | 0.0041 | |

| 1000 | 36.40 ± 2.11 | 19.60 ± 1.56∗∗∗ | 0.0006 | |

| 1500 | 44.25 ± 1.37 | 34.33 ± 0.88 | 0.0698 | |

| N. Saline (ml) | 10 | 37.20 ± 0.89 | 22.50 ± 0.50∗∗ | 0.0085 |

| Art/Lum | 1.14 | 38.00 ± 0.91 | 30.00 ± 1.00∗ | 0.0390 |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM; (n = 5), Data analysed using Paired t-test ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗p < 0.0001, PCV = mean packed cell volume, PCV4 = pre-extract treatment value on day 4, PCV9 = post-extract treatment value on day 9.

4. Discussion

In Ghana, traditional antimalarial herbal medicines are produced in the form of decoctions and infusions.35 The cold maceration extraction technique was utilized in this study since it mimics the method that is popular among the locals. This approach was also influenced by a previous method used to obtain a crude extract from this plant.36 The phytochemical screening of A. africana crude extract revealed the presence of highly polar secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, glycosides, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, terpenoids, and phytosterols in the current study (Table 1). The current findings concerning the secondary metabolites substantiate earlier reports on this plant.36, 37, 38, 39 HPLC analysis of the A. africana extract revealed wide variability in its phytochemical content (Fig. 1). High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) fingerprinting has been advocated as the best method for the chemical characterisation of natural products.40,41 The wavelength (212 nm) used for secondary metabolite profiling of the ethanolic extract is typical for antimalarial drugs' gradient HPLC-UV method recommended by the artemisinin monograph41, 42, 43 However, the technique has only successfully helped to obtain an overview of the secondary metabolite profile of A. africana in the absence of authentic standards.

This study evaluated the antimalarial activity of AAE using both in vitro and in vivo methods as proposed by Fidock et al. (2004).31 The in vitro antimalarial activity of the leaf extract against the P. falciparum (Pf3D7 strain) in this study was considered ‘active’, since the mean IC50 value was 49.30 ± 7.15 μg/mL, indicating that the plant has promising antimalarial potential.34 This outcome confirmed previous findings regarding other species of mangrove plants, which have been reported to possess high antimalarial activity.44 The presence of bioactive compounds embedded in these mangrove plants is believed to be responsible for their significant antimalarial activity.45,46

The 4-day suppressive test investigates the extract's ability to suppress P. berghei parasites in infected mice. It is widely used to screen potential antimalarial agents for antimalarial efficacy.47

The preference for the in vivo model in this study takes into account the possible prodrug effect and also the probable contribution of the host's immune system in the elimination of the parasites.29 The Rane's test has been suggested to be the most reliable technique in malaria drug discovery.31,32 Several studies, including Kalra et al. (2006),48 have suggested that this method remains one of the most commonly used techniques in the assessing the efficacy of potential antimalarial compounds.

The chemo-suppressive effect of 70% ethanol AAE against the parasite is dose-dependent, with the lowest and highest doses of 200 and 1500 mg/kg recording 53% and 100% chemo-suppression, respectively (Fig. 4). The study's findings revealed a significant (P < 0.05) percentage suppression of parasitaemia in P. berghei-infected mice in the 4-day suppressive test. The parasitaemias of the various groups were found to significantly decrease as the dose levels increased, with a significant increase in suppression when compared to the controls. It has been proposed that if an extract suppresses parasitaemia by 50% or more at doses of 500, 250, or 100 mg/kg body weight per day, it is considered to have moderate, good, or very good in vivo antimalarial activity.49 Based on the foregoing, the crude extract's chemo-suppressive ability ranges from ‘moderate’ to ‘very good’ with increasing doses. With a total clearance of parasites from the blood, the peak therapeutic effective concentration may have been reached at 1500 mg/kg (Fig. 4a). It appears from the findings that the active compounds in the plant responsible for antimalarial activity are mainly concentrated in higher doses.

Anaemia, weight loss and hypothermia are common manifestations of P. berghei infection in mice.50 In this study, the extract did not cause a significant change in body weight among the treatment groups except for the reference drug group, where there was weight gain. The extract at dose level (1500 mg/kg) significantly (p < 0.05) prolonged the survival days of mice with an associated decrease in parasitaemia as compared to the controls. The mean survival time (MST) and survival rate of the mice were prolonged by the extract across the treatment groups, from the lower dose level to the highest dose level compared to control groups, similar to the observation made by Belay et al. (2018).2

The curative test of AAE revealed a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in parasite density and an increase in parasite inhibition with increasing dose levels across the treatment groups, similar to results obtained in the 4-day suppression test. The highest dose produced a maximum percentage suppressive effect (100%) with the highest curative effect in Rane's test. The total parasite clearance at a dose level of 1500 mg/kg obtained 24 h post-5-day drug administration (D9), showed that the secondary metabolites in the crude extract possess a possible long-acting bioactive antimalarial activity.51 Combining this extract with another fast, short-lived antimalarial agent may be a good candidate for combination therapy.52 Anaemia in mice, as well as humans, can be attributed to splenic clearance of parasitized RBCs and uninfected cells. Due to the rising levels of parasitaemia, the infected RBCs break up to release merozoites which invade uninfected RBCs and invariably inhibit erythropoiesis.53 As a consequence, packed cell volume (PCV) was evaluated in this study to assess the ability of the extract to forestall haemolysis due to increasing parasitaemia levels in the blood. The extract prevented a significant reduction in PCV in mice. The antihaemolytic effect of the extract correlates favourably well with the total parasite clearance in both the suppressive and curative studies. However, there was a significant reduction in PCV values across the rest of the extract-treated groups.

The presence of secondary metabolites (alkaloids, terpenoids, tannins) inherent in the extract may explain the efficacy of AAE at 1500 mg/kg in both early infection (suppressive activity) and established infections (curative test). These bioactive compounds may have produced the antimalarial effects separately or in synergy. Alkaloidal compounds are believed to engineer a variety of metabolic activities in both humans and animals,54 with infinite pharmacological activities that include antimalarials. A good example is quinine, a notable alkaloid55 derived from the Cinchona succirubra plant which for centuries has been used to treat malaria infections.51

The mechanism of action of quinine is thought to be similar to that of chloroquine.56 The deprotonated chloroquine concentrates in the digestive vacuole and dimerizes with ferriprotoporphyrin IX, which inhibits heme polymerization, resulting in the build-up of a heme-chloroquine complex in the parasite's digestive vacuole56 and eventually killing the parasite. The presence of alkaloids in the plant may have disrupted the production of hemozoin in the parasite at various stages such as the ring or schizont stage by a variety of events such as dissipating mitochondrial capability as an early event in their antiplasmodial effect.57 Also, the contribution of terpenoids or their synergies with other bioactive compounds in plants against malaria parasites have been extensively studied by several actors in the medical sciences in recent times.58, 59, 60, 61 Tannins in medicinal plants form tannin-zinc or tannin-iron complexes that obstruct parasite growth (trophozoite stage) by depriving the parasites of the needed growth requirements.62 These bioactive compounds have been associated with antimalarial activities63 and are possibly the reason for the extract's higher suppressive and inhibitory activities.

The extract may serve as a good antimalarial drug candidate for the treatment of the infection, due to its demonstrably high curative power in established infections and suppressive effect at 1500 mg/kg. In comparing the performance of our test extract (AAE) to the standard (Artesunate) in the present study, the reference drug performed well with excellent activity in the nano range (in vitro) while the tested AAE extract performed quite well in the micro range. This is because the extract is a crude sample that possesses certain metabolites that may not be active components as opposed to a pure standard drug. Consequently, the HPLC analysis could not identify the actual compounds responsible for the antimalarial effect of the plant in this study, but it did validate the bioactive metabolites tested in the plant. Further studies would be required to isolate as well as to elucidate the structures of the bioactive compounds using HPLC-MS and NMR spectroscopy analysis.

5. Conclusion

These findings suggest that A. africana possess a promising antimalarial activity, hence supporting its folkloric use by mangrove dwellers to treat malaria. This is the first time antimalarial activity on this plant has been reported, to the best of our knowledge.

Ethical approval

All experiments were reviewed, cleared and approved (ID: UCCIRB/CHAS/2016/13) by the Ethical Committee on experimental animals of the Department of Biomedical Sciences, School of Allied Health Sciences, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana. Per the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, NIH, Department of Health Services Publication, USA.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors' thanks Dr Linda E. Amoah of the Department of Immunology, NMIMR, University of Ghana, Legon for the provision of the Plasmodium berghei Stabilates.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of The Center for Food and Biomolecules, National Taiwan University.

Contributor Information

Mustapha A. Ahmed, Email: mabubakarahmed@gmail.com.

Elvis O. Ameyaw, Email: eameyaw@ucc.edu.gh.

Desmond O. Acheampong, Email: dacheampong@ucc.edu.gh.

Benjamin Amoani, Email: bamoani@ucc.edu.gh.

Paulina Ampomah, Email: pampomah@ucc.edu.gh.

Emmanuel A. Adakudugu, Email: emmanuel.adakudugu@ucc.edu.gh.

Christian K. Adokoh, Email: cadokoh@ucc.edu.gh.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. World malaria report 2020: 20 years of global progress and challenges. ‘World malaria report 2020: 20 years of global progress and challenges. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belay W.Y., Endale Gurmu A., Wubneh Z.B. Antimalarial activity of stem bark of Periploca linearifolia during early and established plasmodium infection in mice. Evid base Compl Alternative Med. 2018;2018:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2018/4169397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gyaase S., Asante K.P., Adeniji E., Boahen O., Cairns M., Owusu-Agyei S. Potential effectmodification of RTS, S/AS01 malaria vaccine efficacy by household socio-economic status. BMC Publ Health. 2021;21(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10294-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nonvignon J., Aryeetey G.C., Malm K.L., et al. Economic burden of malaria on businesses in Ghana: a case for private sector investment in malaria control. Malar J. 2016;15(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1506-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wicht K.J., Mok S., Fidock D.A. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2020;74:431–454. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reyburn H. New WHO guidelines for the treatment of malaria. BMJ Clinical Research Edition. 2010;2010(340):c2637. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haq I. Safety of medicinal plants. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2004;43(4):203–210. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsaeimehr A., Martinez-Chapa S.O., Parra-Saldívar R. Medicinal plants versus skin disorders: a survey from ancient to modern herbalism: in clinical microbiology: diagnosis, treatments and prophylaxis of infections. The Microbiology of Skin, Soft Tissue, Bone and Joint Infections. 2017;2:205–221. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed M.A. University of Cape Coast); 2019. Assessment Of Antimalarial Activity and Toxicity of avicennia Africana Ethanol Leaf Extract in Rodent Model. Doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziblim I.A., Timothy K.A., Deo-Anyi E.J. Exploitation and use of medicinal plants, Northern region, Ghana. J Med Plants Res. 2013;7(27):1984–1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwansa-Bentum B., Ayi I., Suzuki T., et al. Administrative practices of health professionals and the use of artesunate-amodiaquine by community members for treating uncomplicated malaria in southern Ghana: implications for artemisinin-based combination therapy deployment. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(10):1215–1224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thatoi H., Samantaray D., Das S.K. The genus Avicenna, a pioneer group of dominant mangrove plant species with potential medicinal values: a review. Front Life Sci. 2016;9(4):267–291. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards S., Da-Costa-Rocha I., Lawrence M.J., Cable C., Heinrich M. Use and efficacy of herbal medicines: part 1—historical and traditional use. Pharmaceut J. 2012;289(7717):161–162. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edu E.A.B., Edwin-Wosu N.L., Udensi O.U. Evaluation of bioactive compounds in mangroves: a Panacea towards exploiting and optimizing mangrove resources. J Nat Sci Res. 2015;5(23):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma A., Singh R.T., Handa S.S. Estimation of phyllanthin and hypophyllanthin by high performance liquid chromatography in Phyllanthus amarus. Phytochem Anal. 1993;4:226–229. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moll K., Ljungström I., Perlmann H., Scherf A., Wahlgren M. fifth ed. vol. 14. 2008. (Methods in Malaria Research). Stockholm, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trager W., Jensen J.B. Pathology, Vector Studies, and Culture. 1980. Cultivation of erythrocytic and exoerythrocytic stages of plasmodia; pp. 271–319. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) TN. 425 . vol. 4. OECD Publishing; 2008. pp. 1–27. (Acute Oral Toxicity: Up-And-Down Procedure). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wadood A., Ghufran M., Jamal S.B., et al. Phytochemical analysis of medicinal plants occurring in the local area of Mardan. Biochem Anal Biochem. 2013;2(4):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sofowora A. Recent trends in research into African medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 1993;38(2-3):197–208. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(93)90017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans W.C., Trease G.E. Trease and Evan Pharmacognosy; 2002. Volatile Oils and Resins; pp. 253–288. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nafiu M.O., Adewuyi A.I., Abdulsalam T.A., Ashafa A.O.T. Antimalarial activity and biochemical effects of saponin-rich extract of Dianthus basuticus Burtt Davy in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. Adv Tradit Med. 2021:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orabueze C.I., Ota D.A., Coker H.A. Antimalarial potentials of Stemonocoleus micranthus Harms (leguminoseae) stem bark in Plasmodium berghei infected mice. J Tradit Complementary Med. 2020;10(1):70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olayode O.A., Daniyan M.O., Olayiwola G. Biochemical, hematological and histopathological evaluation of the toxicity potential of the leaf extract of Stachytarpheta cayennensis in rats. J Tradit Complementary Med. 2020;10(6):544–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Claessens A., Rowe J.A. Selection of plasmodium falciparum parasites for cytoadhesion to human brain endothelial cells. JoVE. 2012;59:e3122. doi: 10.3791/3122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amoah L.E., Kakaney C., Kwansa-Bentum B., Kusi K.A. Activity of herbal medicines on Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes: implications for malaria transmission in Ghana. PLoS One. 2015;10(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olasehinde G.I., Ojurongbe O., Adeyeba A.O., Fagade O.E., Valecha N., Ayanda I.O., Ajayi A.A., Egwari L.O. In vitro studies on the sensitivity pattern of Plasmodium falciparum to anti-malarial drugs and local herbal extracts. Malar J. 2014;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smilkstein M., Sriwilaijaroen N., Kelly J.X., et al. Simple and inexpensive fluorescence-based technique for high-throughput antimalarial drug screening. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(5):1803–1806. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1803-1806.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waako P.J., Gumede B., Smith P., Folb P.I. The in vitro and in vivo antimalarial activity of Cardiospermum halicacabum L. and Momordica foetida Schumch. Et Thonn. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;99(1):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mzena T., Swai H., Chacha M. Antimalarial activity of Cucumis metuliferus and Lippia kituiensis against Plasmodium berghei infection in mice. Res Rep Trop Med. 2018;9:81. doi: 10.2147/RRTM.S150091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fidock D.A., Rosenthal P.J., Croft S.L., et al. Antimalarial drug discovery: efficacy models for compound screening. Supplementary documents. Trends Parasitol. 2004;15:19–29. doi: 10.1038/nrd1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryley J.F., Peters W. The antimalarial activity of some quinolone esters. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1970;64(2):209–222. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1970.11686683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muluye R.A., Berihun A.M., Gelagle A.A., Lemmi W.G., et al. Evaluation of in vivo antiplasmodial and toxicological effect of Calpurnia aurea, Aloe debrana, Vernonia amygdalina and Croton macrostachyus extracts in mice. Med Chem. 2021;11:534. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramazani A., Zakeri S., Sardari S., et al. In vitro and in vivo anti-malarial activity of Boerhavia elegans and Solanum surattense. Malar J. 2010;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boadu A.A., Asase A. Documentation of herbal medicines used for the treatment andmanagement of human diseases by some communities in southern Ghana. Evid base Compl Alternative Med. 2017;8:2017. doi: 10.1155/2017/3043061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mfilinge P.L., Meziane T., Bachok Z., Tsuchiya M. Litter dynamics and particulate organic matter outwelling from a subtropical mangrove in Okinawa Island, South Japan. Estuarine. Coastal and Shelf Science. 2005;63:301–313. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiyama H., Fuju K., Yamasaki O., Oono T., Iwatsuki K. Antibacterial action of several tannins against. Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2001;48(4):487–491. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.4.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khafagi I., Gab-Alla A., Salama W.B., Fouda M. Biological activities and phytochemical constituents of the grey mangrove, Avicennia marina (Forssk) Yeoh. Egypt J Biol. 2003;5:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauer R., Tittel G. Quality assessment of herbal preparations as a precondition of pharmacological and clinical studies. Phytomedicine. 1996;2:193–198. doi: 10.1016/S0944-7113(96)80041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Springfield E.P., Eagles P.K.F., Scott G. Quality assessment of South African herbal medicines by means of HPLC fingerprinting. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;101:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The International Pharmocopeia. WHO; Geneva: 2003. WHO, artemisinin monograph; pp. 185–233. [Google Scholar]

- 42.WHO . 2006. Monograph on Good Agricultural and Collection Practices (GACP) for Artemisia Annua L. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lapkin A.A., Walker A., Sullivan N., et al. 2009. Development of HPLC Analytical Protocol for Artemisinin Quantification in Plant Materials and Extracts. Summary of Report on the Medicines for Malaria Ventures Supported Project.https://www.mmv.org/sites/default/files/uploads/docs/publications/2-HPLC methods for Artemisinin Report_Summary_for_MMV_3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravikumar S., Inbaneson S.J., Ramu A., et al. Mangrove plants as a source of lead compounds for the development of new antiplasmodial drugs from the South East coast of India. Parasitol Res. 2011;108(6):1405–1410. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basak U.C., Das A.B., Das P. Chlorophylls, carotenoids, proteins and secondary metabolites in leaves of 14 species of mangrove. Bull Mar Sci. 1996;58(3):654–659. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bandaranayake W.M. Bioactivities, bioactive compounds and chemical constituents of mangrove plants. Wetl Ecol Manag. 2002;10(6):421–452. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aherne S.A., Daly T., O'Connor T., O'Brien N.M. Immunomodulatory effects of β sitosterol on human Jurkat T cells. Planta Med. 2007;73 09. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalra B.S., Chawla S., Gupta P., Valecha N. Screening of antimalarial drugs: an overview. Indian J Pharmacol. 2006;38(1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nardos A., Makonnen E. In vivo antiplasmodial activity and toxicological assessment of hydroethanolic crude extract of Ajuga remota. Malar J. 2017;16(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12936-017-1677-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langhorne J., Quin S.J., Sanni L.A. Mouse models of blood-stage malaria infections: immune responses and cytokines involved in protection and pathology. Chem Immunol. 2002;80(80):204–228. doi: 10.1159/000058845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaur K., Jain M., Kaur T., Jain R. Antimalarials from nature. Bioorg Med Chem. 2009;17(9):3229–3256. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orabueze C.I., Ota D.A., Coker H.A. Antimalarial potentials of Stemonocoleus micranthus Harms (Leguminosae) stem bark in Plasmodium berghei infected mice. J Tradit Complementory Med. 2020;10(1):70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chinchilla M., Guerrero O.M., Abarca G., et al. An in vivo model to study the anti-malaric capacity of plant extracts. Rev Biol Trop. 1998;46(1):35–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robbers J.E., Speedie M.K., Tyler V.E. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 1996. "Chapter 9: Alkaloids". Pharmacognosy and Pharmacobiotechnology; pp. 143–185. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mekonnen L.B. In vivo antimalarial activity of the crude root and fruit extracts of Croton macrostachyus (Euphorbiaceae) against Plasmodium berghei in mice. J Tradit Complementary Med. 2015;5(3):168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daskum A.M., Chessed G., Qadeer M.A., Mustapha T. Antimalarial chemotherapy, mechanisms of action and resistance to major antimalarial drugs in clinical use: A Review. Microb Infect Dis. 2021;2(1):130–142. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li J.Y., Sun X.F., Li J.J., Yu F., Zhang Y., Huang X.J., Jiang F.X. The antimalarial activity of indole alkaloids and hybrids. Arch Pharmazie. 2020;353(11):2000131. doi: 10.1002/ardp.202000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kane N.F., Kyama M.C., Nganga J.K., et al. Comparison of phytochemical profiles and antimalarial activities of Artemisia afra plant collected from five countries in Africa. South Afr J Bot. 2019;125:126–133. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oluba O.M. Ganoderma terpenoid extract exhibited anti-plasmodial activity by a mechanism involving a reduction in erythrocyte and hepatic lipids in Plasmodium berghei infected mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2019;18(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12944-018-0951-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Isah M.B., Tajuddeen N., Umar M.I., et al. Terpenoids as emerging therapeutic agents: cellular targets and mechanisms of action against Protozoan parasites. Stud Nat Prod Chem. 2019;59:227–250. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duarte N., Ramalhete C., Lourenço L. Plant terpenoids as lead compounds against malaria and Leishmaniasis. Stud Nat Prod Chem. 2019;62:243–306. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sereme A., Milogo-Rasolodimby J., Guinko S., et al. Therapeutic power of tannins producing species of Burkina Faso. Pharmacopoeia and Africa Traditional Medicine. 2008;15:41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Oliveira A.B., Dolabela M.F., Braga F.C., et al. Plant-derived antimalarial agents: new leads and efficient phytomedicines. Part I. Alkaloids. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2009;81(4):715–740. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652009000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]