Abstract

Background

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) constitute the leading cause of mortality globally. Low and middle-income countries (LMICs) not only experience the largest burden of humanitarian emergencies but are also disproportionately affected by NCDs, yet primary focus on the topic is lagging. We conducted a systematic review on the effect of humanitarian disasters on NCDs in LMICs assessing epidemiology, interventions, and treatment.

Methods

A systematic search in MEDLINE, MEDLINE (PubMed, for in-process and non-indexed citations), Social Science Citation Index, and Global Health (EBSCO) for indexed articles published before December 11, 2017 was conducted, and publications reporting on NCDs and humanitarian emergencies in LMICs were included. We extracted and synthesized results using a thematic analysis approach and present the results by disease type. The study is registered at PROSPERO (CRD42018088769).

Results

Of the 85 included publications, most reported on observational research studies and almost half (48.9%) reported on studies in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO), with scant studies reporting on the African and Americas regions. NCDs represented a significant burden for populations affected by humanitarian crises in our findings, despite a dearth of data from particular regions and disease categories. The majority of studies included in our review presented epidemiologic evidence for the burden of disease, while few studies addressed clinical management or intervention delivery. Commonly cited barriers to healthcare access in all phases of disaster and major disease diagnoses studied included: low levels of education, financial difficulties, displacement, illiteracy, lack of access to medications, affordability of treatment and monitoring devices, and centralized healthcare infrastructure for NCDs. Screening and prevention for NCDs in disaster-prone settings was supported. Refugee status was independently identified both as a risk factor for diagnosis with an NCD and conferring worse morbidity.

Conclusions

An increased focus on the effects of, and mitigating factors for, NCDs occurring in disaster-afflicted LMICs is needed. While the majority of studies included in our review presented epidemiologic evidence for the burden of disease, research is needed to address contributing factors, interventions, and means of managing disease during humanitarian emergencies in LMICs.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-022-13399-z.

Keywords: NCDs, Non communicable diseases, Disaster, Warfare and armed conflicts, Cardiovascular disease, Diabetes mellitus, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Asthma, Disaster medicine, Cancer

Background

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) constitute the leading cause of mortality globally, accounting for 70% of deaths worldwide [1]. This percentage is projected to rise in the next fifteen years, with the steepest increase in morbidity and mortality from NCDs projected to occur in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs). The World Health Organization (WHO) projects a 10% rise in mortality in Africa from NCDs in from 2015 to 2030 [2]. This rise in NCDs in LMICs coincides with an increasing burden of humanitarian disasters [3].

The International Red Cross defines a disaster as: “a sudden, calamitous event that seriously disrupts the functioning of a community or society and causes human, material, and economic or environmental losses that exceed the community’s or society’s ability to cope using its own resources” [4], and can be divided into: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery phases [5]. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR) recorded over 1.35 million people killed by natural hazards between 1997–2017, with disproportionate mortality in LMICs [6]. Poverty, rapid urbanization, inadequate infrastructure, and underdeveloped disaster warning and health systems are all contributors to morbidity and mortality in disasters [6, 7].

According to the UNHCR Global Trends Report, an unprecedented 79.5 million people are estimated to have been displaced from their homes as internally displaced persons (IDPs) or refugees in 2019—the largest figure ever recorded [8]. The scale of humanitarian disasters has increased in recent decades for two primary reasons. Firstly, the frequency and ferocity of natural disasters are increasing due to climate change [9]. Secondly, the number of refugees, displaced persons, and migrants are at an all-time high due to the unprecedented refugee crises in Syria, Iraq, and the Democratic Republic of Congo [10]. Disasters may directly exacerbate NCDs through effects such as increased stress levels [11], exposures such as inhalation of substances that trigger worsening of pulmonary disease [12], and exacerbation of underlying disease secondary to limited access to care [13].

Despite the growing burden of humanitarian crises with increasing populations at risk for morbidity and mortality from NCDs, primary focus on the topic is lagging. It is essential to better understand the effect of disasters on NCDs in LMICs as the mortality and morbidity are projected only to increase given climate change and population growth in vulnerable areas [14]. In this context, we conducted a systematic review on the effect of humanitarian disasters on NCDs in LMICs assessing epidemiology, interventions, and treatment. While a limited number of articles have reviewed interventions for NCD management [15, 16], a single NCD disease type [17, 18], or a single geographic region in disaster settings [18–21], to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of its kind cross-cutting both regions and disease type. Our aims are to guide allocation of resources, future research, and policy development.

Methods

An experienced medical librarian performed a comprehensive search of multiple databases after consultation with the lead authors and a Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) analysis of key articles provided by the research team.

Eligibility criteria

In each database, we used an iterative process to translate and refine the searches. English, Arabic and French language articles were eligible based on these languages being spoken frequently in LMICs, our team’s language capabilities, and so as not to limit solely to English language articles and potential reporting bias as a result [22]. The formal search strategies used relevant controlled vocabulary terms and synonymous free text words and phrases to capture the concepts of noncommunicable, chronic and noninfectious diseases, and different types of humanitarian emergencies including natural disasters, armed conflicts, terrorism, and failed states (see Additional file 1).

Information sources

The databases searched were MEDLINE (OvidSP 1946-August Week 2 2015), MEDLINE (PubMed, for in-process and non-indexed citations), Social Science Citation Index, and Global Health (EBSCO).

Search strategy

We included studies conducted in LMICs investigating non-communicable diseases in the context of humanitarian emergencies; LMICs were categorized as outlined by The World Bank [23]. Studies conducted in high income countries (HICs) and review articles were excluded. Mental health and associated terms were not included in this review given evidence on the disease burden in existing literature [24–28] and our own research question which sought to address the leading four NCDs (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer and chronic respiratory disease) as outlined by the WHO [29]. No other restrictions on study type were applied. The original searches were run August 10, 2015 and were rerun on December 11, 2017. No date restrictions were applied such that any publication prior to this date was potentially eligible for inclusion. The full strategy for PubMed is available in the Additional file 1. The study is registered at PROSPERO (CRD42018088769).

Selection process

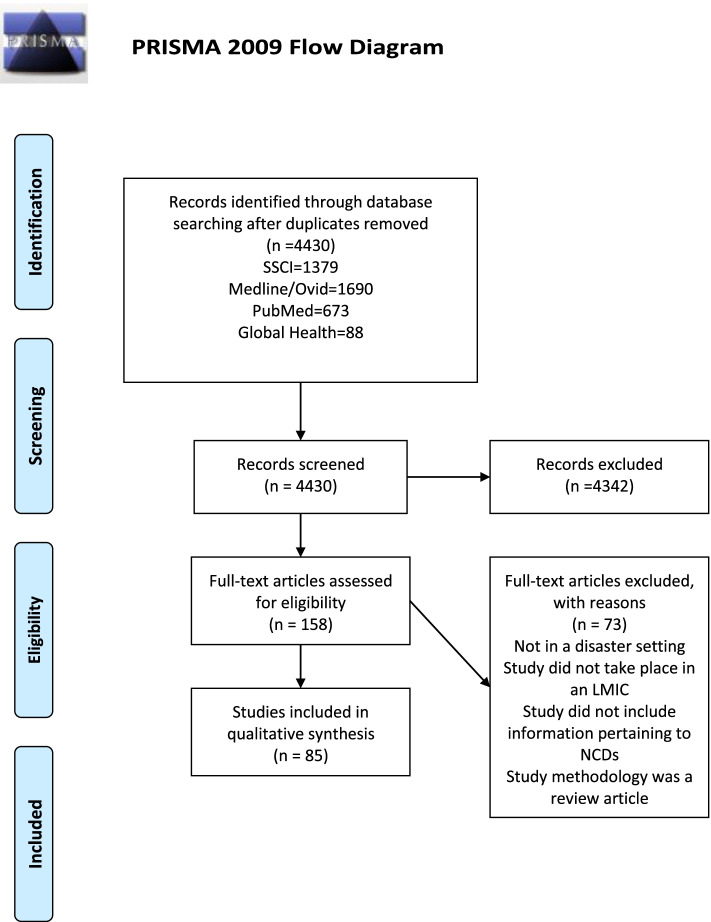

Retrieved references were pooled in EndNote and de-duplicated to 4,430 citations. Two separate screeners independently evaluated the titles, abstracts and full text of the eligible articles (RB and LW), with vetting by a third reviewer (CN). The flowchart per PRISMA is presented in Fig. 1. An assessment of the risk of bias of included studies is provided in tabular format in the Additional file 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Study risk of bias assessment

Bias was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for assessing risk of bias given majority observational studies in our findings [30].

Results

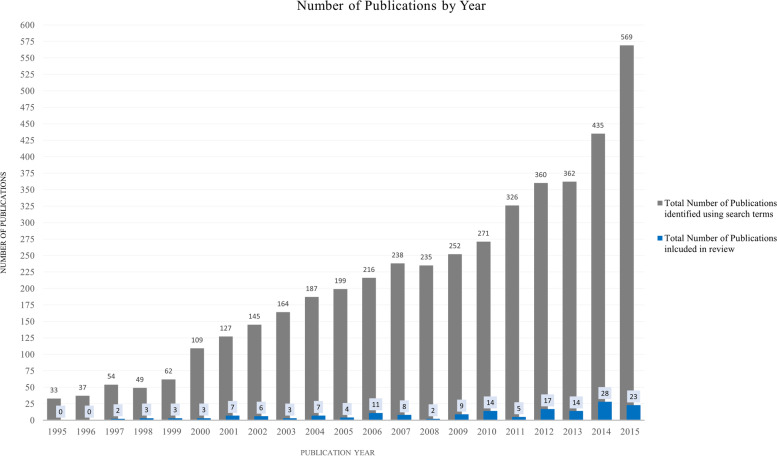

We retrieved a total of 4,430 references. Four thousand three hundred forty-two studies were excluded by title or abstract, and 158 articles were read in full. Out of the studies screened by full text, 85 studies are included in the final thematic analysis (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10; Fig. 2), with increasing publications on the topic over time (Fig. 2). For ease of review, we have presented the results by disease type (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5; Fig. 3) including summaries on study type as well as epidemiology of disease addressed. We felt that the study design would be relevant, in addition to the disease focus, in order to elucidate opportunities for future research based on study approaches that were lacking. The diseases types are split into five categories, which consist of the lead four NCDs in order of burden [29]: cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancer, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes, and a section on other NCDs (defined as those identified in our results that assessed NCDs not fitting into one of the lead four categories). We have also grouped the articles by region, and those results have been presented in tabular format and graphically (Tables 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10; Fig. 4). We present the results on interventions in detail elsewhere [31].

Table 1.

Characteristics of included publications by disease type: Cardiovascular Disease

|

Country/ Territory of Interest |

WHO region | Type of study | Target Population | Years of observation | Number of study participants | Major findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abukhdeir (2013) [32] | Palestinian Territories: West Bank/Gaza | EMRO | Cross sectional | Palestinian households in the West Bank and Gaza Strip | May 2004—July 2004 | 4,456 households in the West Bank and 2118 in the Gaza Strip | Being a refugee was a significant risk factor for CVD while being married/engaged or divorced/separated/ widowed was a risk factor for hypertension. Non-refugees were 46% less likely to have CVD than refugees. Gender was a risk factor for hypertension with females being 60% more likely to have hypertension than males. Age was a significant risk factor for hypertension and CVD(p < 0.0001) |

| Ahmad (2015) [33] | Syria | EMRO | Situational analysis using document analysis, key informant interviews, and direct clinic observation | Syrian national health system | October 2009 -August 2010 | 53 semi-structured interviews | The rebuilding of a post-conflict heath care system in Syria may benefit from insights into the structural problems of the pre-crisis system. Weaknesses that existed before the crisis are compounded by the current conflict |

| Armenian (1998) [34] | Armenia | Europe | Retrospective cohort | Employees of the Armenian Ministry of Health and their immediate families who survived the 1988 Earthquake in Armenia | 1990–1992 | 35,043 persons (7,721 employees who had survived the disaster and their family members) | The nested case–control analysis of 483 cases of newly reported heart disease and 482 matched non-heart-disease controls revealed that people with increasing levels of loss of material possessions and family members had significant increases in heart disease risk (OR for “loss scores” of 1, 2, and 3 were 1.3, 1.8, and 2.6, respectively) |

| Ben Romdhane (2015) [35] | Tunisia | EMRO | Situational analysis | Tunisian national health system | 2010 | 12 key informants were interviewed and eight documents were reviewed | Weaknesses that existed before the 2011 Revolution (Arab Spring) were compounded during the revolution. This study was conducted prior to political conflict but written post-conflict. Growth of the private sector fostered unequal access by socioeconomic status and reduced coordination and preparedness of the health system |

| Bergovec (2005) [36] | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Europe | Retrospective chart review | The population that lived in Mostar and the nine neighboring districts prior to the Bosnian War(1992–1995) | Five consecutive years (1987–1991) before the war and 5 consecutive years (1992–1996) during the war were analyzed | 182,000 persons per the 1991 census | There was a wartime increase in acute myocardial infarctions(AMI) for the total population (p = 0.025). There was a statistically significant increase (p = 0.001) in the total number of unstable angina pectoris(UA) cases during the war (185 cases, compared with 125 prewar cases). Females experienced a statistically significant increase in UA and AMI(p = 0.001, 0.007 respectively) whereas the increase among men was not statistically significant (p = 0.072, p = 0.354 respectively) |

| Chen (2009) [37] | China | Western Pacific | Case series | Adults who were in the West China Hospital on the day of the 2008 Sichuan (Wenchuan) earthquake | May 2008 | 11 patients | Mean blood pressure and heart rate increased immediately after the earthquake, regardless of gender or pre-existing hypertension. BP gradually declined within 6 h after the earthquake and increased again during aftershocks. Circadian variation was absent in all cases |

| Ebling (2007) [38] | Croatia | Europe | Multipart study including both a retrospective cohort study and an uncontrolled before-after study | Refugee-returnees of the 1991–1992 war operations in Eastern Slavonia from Osjek-Baranga County, Croatia | 2003 |

retrospective cohort study: 589 participants uncontrolled before-after study 202 participants |

Single counseling session aimed at lifestyle changes can be effective at decreasing CVD risk factors. The participation of subjects with high blood pressure in the population of displaced returnees, exceeded the values for both Slavonia and Croatia census data |

| Ebrahimi (2014) [39] | Iran | EMRO | Cross sectional | Patients with cardiovascular and respiratory diseases who received medical services from the Center for Disaster and Emergency Medicine in Sanandaj, Iran during dust event days | March 2009—June 2010 | – | A statistically significant increase in emergency admissions for cardiovascular diseases was demonstrated during dust storm episodes in Sanandaj, Iran(correlation coefficient (r) = 0.48, p < 0.05) |

| Huerga (2009) [40] | Liberia | Africa | Retrospective chart review | Patients of the medical and pediatric wards of Mamba Point Hospital, Monrovia, Liberia, one year after the end of the Liberian civil war | January 2005—July 2005 |

1,034 adult patients 1,509 children |

Non- infectious diseases accounted for 56% of the adult deaths. The main causes of death were meningitis (16%), stroke (14%) and heart failure (10%).Cardiovascular diseases caused half of deaths due to non-infectious diseases: 25% stroke, 18% heart failure, and 10% severe hypertension. No cases of ischemic heart disease were identified |

| Hult (2010) [41] | Nigeria | Africa | Retrospective cohort | 40 year old Nigerians with fetal exposure to famine in Biafra, Nigeria during the Nigerian civil war (1967–1970) | June 2009–July 2009 | 1,339 study participants | Fetal-infant exposure to famine was associated with elevated systolic (+ 7 mmHg; p < 0.001) and diastolic (+ 5 mmHg; p < 0.001) blood pressure, waist circumference (+ 3 cm, p < 0.001), increased risk of systolic hypertension (adjusted OR 2.87; 95% CI 1.90–4.34), and overweight status (OR 1.41; 95% CI 1.03–1.93) as compared to people born after the famine |

| Hung (2013) [42] | China | Western Pacific | Retrospective chart review | Patients treated by Hong Kong Red Cross three weeks after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake | June 2008 | 2,034 patient encounters | There was a high prevalence of chronic disease after the earthquake, especially hypertension. 43.4% of the 762 patients with blood pressure measurements were above the recognized criteria for hypertension |

| Kadojic (1999) [43] | Croatia | Europe | Cohort study | Displaced persons aged 20-60y with signs of PTSD and a history of traumatic war experience living in a displaced persons camp since 1991 | – | 120 displaced persons | Displaced persons in Croatia residing in camps had a significantly higher prevalence (p < 0.05) of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity when compared to age-matched controls in settlements adjacent to the study population not impacted by the war. Total risk for stroke was higher in the exposed group(p < 0.05 |

| Kallab (2015) [44] |

Country of Asylum: Lebanon Country of Origin: Syria |

EMRO | Program implementation reflection | Syrian refugees and vulnerable Lebanese being treated in 8 health facilities run by Amel Association International | November 2014- May 2015 | 1,825 patients | Of the 1,825 patients enrolled in the program hypertension and diabetes accounted for 46% and 27% of cases respectively, with the remaining 27% of patients presenting with both diseases. Major challenges included medications shortages and cost, insecurity, patient transportation cost, and high workload for providers |

| Khader (2014) [45] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Retrospective cohort study with program and outcome data collected and analyzed using E-Health | Palestine refugees living in Jordan | October 2009- June 2013 | 18,881 patients | 50% of patients were diagnosed with both hypertension and diabetes and 50% had hypertension alone. There were significantly more patients with hypertension and diabetes (N = 966, 13%) who had disease- related complications than patients who had hypertension alone (N = 472, 6%) [OR 2.2, 95% CI 2.0–2.5]. Most common risk factors included smoking, physical inactivity, and obesity |

| Marjanovic (2003) [46] | Croatia | Europe | Retrospective chart review | Patients examined at Beli Manastir Health Center Department of Emergency in Baranya, Croatia post- war | November 1997 (the time of Baranya reintegration into the legal system of the Republic of Croatia after the war)—December 2001 | 513 stroke patients | Stroke patients presenting to the emergency department at a single site had an average of 68.4y, with an age range from 25-91y, and a near equal distribution between men and women (51.7% male). Only 50.6% of patients presented within 6 h, another 16.2% presented after 24 h. Paresis, speech impairment and vision impairment were the most common presenting symptoms. 85.8% of patients had hypertension, 27% had diabetes, 44.6% had hyperlipidemia and 46% also had cardiac disease. 38.4% of patients presenting to the hospital died |

| Markoglou (2005) [47] | Kosovo | Europe | Cross sectional | Patients under the care of the NATO forces who provided medical services to the civilians of Kosovo during the Yugoslav Wars | January 2000—July 2000 | 830 patients | 30.6% patients were diagnosed with hypertension (188 female and 66 male). More than half of the patients (51.2%) had severe hypertension, 31.5% modest and 17.3% mild. Only 5.5% of patients were on regular antihypertensive treatment (9.09% men and 4.24% women). Concomitant diseases in our patients (62% of patients) were in descending order by incidence rheumatic, cardiovascular and COPD disorders. Hypertension due to increased sympathetic activity(attributed to war stress) was present in 35 patients, (13.78%, 32 – 17.02% women and 3 – 4.55% men, p < 0.05), and hypertension secondary to the use of NSAIDs or cortisone in 15 patients (5.91%, 8 women – 4.26% and 7 men – 10.6%, p > 0.1) |

| Mateen (2012) [48] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Iraq |

EMRO | Retrospective Cohort | Iraqi refugees receiving UNHCR health assistance in Jordan | January 2010-December 2010 | 7,642 registered Iraqi refugees | For adults 18y and older, primary hypertension was the top diagnosis(22%). Diagnoses requiring the greatest number of visits per refugee were cerebrovascular disease (average of 1.46 visits per refugee); senile cataract (1.46); glaucoma (1.44); urolithiasis (1.38); prostatic hyperplasia(1.36); and angina pectoris (1.35). Concomitant disease was common (60% has more than one diagnosis) |

| Miric (2001) [49] | Croatia | Europe | Retrospective chart review | Patients hospitalized in coronary care units of Clinical Hospital Split prior to, during, and following the Croatian War of Independence | 1989—1997 | 3,454 patients | In the 3-year period preceding the war, from 1989 to 1991, 1,024 patients were hospitalized because of MI. During the 3 years of full war activities, from 1992 to 1994, there were 1,257 patients (significantly more; p < 0.05). And in the 3-year period after the war, from 1995 to 1997, there were 1,173 patients. Older age was a risk factor for greater morbidity and mortality, however the number of smokers was greater among patients younger than 45 years (75% vs. 51%; p < 0.001) |

| Mousa (2010) [50] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, West Bank/Gaza Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Case series | Refugees registered by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) | June 2007 | 7,762 refugees | Overall 18.7% of the screened population presented with high blood pressure (≥ 140/ ≥ 90 mmHg). People were referred for screening most commonly because of age (both sexes), followed by smoking (males) and family history (females). More females over 40 years of age were screened than men (p < 0.01) |

| Otoukesh (2012) [51] |

Country of Asylum: Iran Country of Origin: Afghanistan |

EMRO | Retrospective cross sectional | Afghan refugees in Iran | 2005 -2010 | 23,152 refugees | Ischemic heart diseases constituted the fourth leading cause of referrals (10.4% of referrals). Referrals by Pashtun group were mostly for neoplasms (17%), among Uzbek group it was nephropathies (26%), and in Baluch group hematopoietic disorders (25%) |

| Sibai (2001) [52] | Lebanon | EMRO | Retrospective cohort study | Lebanese aged 50 years and over residing in Beirut, Lebanon in 1983 | 1983–1993 | 1,567 cases | The most important causes were non-communicable diseases, mainly circulatory disease (60%); and cancer (15%). Among circulatory diseases, ischaemic heart disease accounted for the majority of the mortality burden (68%) followed by cerebrovascular diseases (21%). In countries that lack reliable sources of mortality data, the utility of verbal autopsy can be viably extended to cohort studies for assessing causes of death |

| Sibai (2007) [30] | Lebanon | EMRO | Retrospective cohort study | Lebanese aged 50 years and over residing in Beirut, Lebanon | 1984–1994 | 1,567 cases | Most important causes of death were CVD and Cancer. High adjusted risk of CVD mortality associated with being single (never-married) versus married among men and women. Outcomes were self-reported |

| Strong (2015) [53] |

Country of Asylum: Lebanon Country of Origin: Syria |

EMRO | Cross sectional | Syrian refugees over age 60 residing in Lebanon and registered with either Caritas Lebanon Migrant Center (CLMC) or the Palestinian Women’s Humanitarian Organization (PALWHO) | March 2011—March 2013 | 210 refugees | Older refugees reported a high burden of chronic illnesses and disabilities. Hypertension was most common (60%), followed by diabetes mellitus (47%), and heart disease (30%). The burden from these diseases was significantly higher in older Palestinians compared to older Syrians, even when controlling for the effects of sex and age (hypertension p < 0.001; diabetes p < 0.001; heart disease p = 0.042). Financial difficulties were given as the primary reason for not seeking care by 79% of older refugees |

| Sun (2013) [54] | China | Western Pacific | Cross sectional | Survivors of Wenchuan earthquake staying in a temporary shelter for more than 1 year | March–May 2009 | 3,230 adults | The prevalence rate of hypertension among survivors was 24.08%. Age, family history of hypertension, sleep quality, waist-to-hip ratio, BMI,and blood glucose levels are risk factors for earthquake-induced hypertension. Mental stress was not a risk factor. The rates of hypertension awareness, dosing, and control was 34.58%, 53.43% and 17.84%, respectively |

| Tomic (2009) [50] | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Europe | Retrospective case control | Pregnant women with hypertensive disorders and their neonates hospitalized in the Obstetric/Gynecological and Pediatric Departments of Mostar Hospital during the war and postwar period (Bosnian War 1992–1995) | January 1995—December 1999 | 542 pregnancies with hypertensive disorders | The prevalence of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy was higher during wartime, demonstrated by a drop in prevalence during the five years after the war, with the highest prevalence occurring at 8.7% during the first year after the war. Those in the study group had higher odds of placental abruption, cesarean delivery, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death. Those in the study group with hypertensive pregnancy disorders had a lower number of prenatal care visits than controls (p < 0.001) |

| Vasilj (2006) [55] | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Europe | Retrospective chart review | Patients who suffered from the acute coronary syndrome in western Herzegovina pre, during, and post-war (Bosnian War 1992–1995) | 1987–2001 | 2,022 patients | There was a higher prevalence of ACS presentations both during (n = 665, p < 0.0005) and after the war (n = 843, p < 0.0005), as compared to prior to the war (n = 365) in both sexes |

| Vukovic (2005) [56] | Serbia | Europe | Retrospective chart review | Patients with ischemic heart disease who were admitted to the Cardiac policlinic for a control check-up immediately after the suspension of air raids | June 1999 | 75 patients | The severity of angina pains and nitroglycerin pill usage was associated with timing of air raids, increasing during the first week and initial week after raids when compared to the week before raids |

| Yusef (2000) [22] |

Country of Asylum: Lebanon Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Cross-sectional | Diabetic and hypertensive patients attending UNRWA primary health care facilities in Lebanon | 1997 | 2,202 records | Presence of both diabetes and hypertension increased the risk for late-stage complications. The major complication was cardiovascular disease followed by retinopathy. Only 18.2% of diabetic patients and 17.7% of diabetic patients with hypertension were managed by lifestyle modification. Medication shortages may drive medication choices for hypertension |

| Zubaid (2006) [57] | Kuwait | EMRO | Retrospective chart review | Catchment area of Mubarak Al Kabeer Hospital | March 2003 | 1 Missile Attack Period (MAP) and 4 control periods | Missile attacks were associated with an increase in the incidence of AMI. The number of admissions for AMI was highest during MAP, 21 cases compared to 14–16 cases in the four control periods, with a trend towards increase during MAP (incidence rate ratio = 1.59; 95% CI 0.95 to 2.66, p < 0.07).The number of admissions for AMI during the first 5 days of MAP was significantly higher compared to the first 5 days of the four control periods (incidence rate ratio = 2.43; 95% CI 1.23 to 4.26,p < 0.01) |

Table 2.

Characteristics of included publications by disease type: Cancer

|

Country/ Territory of Interest |

WHO region | Type of study | Target Population | Years of observation | Number of study participants | Major findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huynh (2004) [58] | Vietnam | Western Pacific | Case control | Vietnamese women hospitalized with cervical cancer | June 1996—September 1996 | 145 women in southern Vietnam and 80 women in northern Vietnam | The development of invasive cervical cancer was significantly associated with military service by husbands during the Second Indochinese War and with parity status. Geographic and temporal variation in cervical cancer rates among Vietnamese women was associated with the movement of soldiers |

| Khan (1997) [59] |

Country of Asylum: Pakistan Country of Origin: Afghanistan |

EMRO | Cross sectional | Patients from North West Pakistan and Afghan refugees attending the Institute of Radiotherapy and Nuclear Medicine, Peshwar | 1990—1994 |

13,359 patients 2988 were Afghan refugees 10,371 were adults from North West of Pakistan |

In male Afghan refugees, esophageal cancer represented 16.6% of the cases, compared to only 4.6% of the cases in Pakistani residents. Both Pakistani and Afghani refugee women experienced breast cancer as the most common cancer |

| Li (2012) [60] | China | Western Pacific | Retrospective cohort | Birth cohorts who were exposed to the 1959–1961 Chinese famine | 1970–2009 | Population of Zhaoyuan county during the 1970–1974 death survey and 2,830,866 during the 2005–2009 death survey | The Zhaoyuan population, which experienced long-term nutritional deficiencies from childhood to adolescence, had increased risk for stomach cancer 15 to 20 years after the 1959–1961 Chinese famine. The birth cohorts who were exposed to famine or experienced malnutrition had higher stomach cancer mortality rates in later life than the birth cohorts not exposed to malnutrition |

| Marom (2014) [61] | Philippines | Western Pacific | Case series | Patients presenting with head and neck (H&N) tumors to a field hospital in the ‘sub-acute’ period following a typhoon | November 2013 | 1844 adult patients examined, 85 (5%) presented with H&N tumors | In a relief mission, despite the lack of clinical and pathological staging and questionable continuity of care, surgical interventions can be considered for therapeutic, palliative and diagnostic purposes |

| McKenzie (2015) [62] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Iraq, Syria |

EMRO | Retrospective cohort | UNHCR registered refugees (Iraqi/Syrian) in Jordan | 2012—2013 | 223 refugees | Brain tumors accounted for 13% (n = 29) of neuropsychiatric applications, and was the most expensive neuropsychiatric diagnosis overall and per applicant. The ECC denied six applications for reasons of eligibility, cost, and/or prognosis. Of the 20 approved applications, 15% (n = 3) were approved for less than the requested amount, receiving on average 39% of requested funds |

| Milojkovic (2005) [63] | Croatia | Europe | Retrospective cohort | Patients with corpus uteri and cervix uteri cancer and ovarian cancer treated in the Clinical Hospital Osijek | 1984 -2002 | 1455 patients treated for gynecological cancer were analyzed | Gynecologic cancer incidence according to age shows an increase tendency of cervical cancer in younger women in the post war period. The incidence of corpus cancer and ovary has not changed in the observed periods |

| Otoukesh (2012) [51] |

Country of Asylum: Iran Country of Origin: Afghanistan |

EMRO | Cross sectional | Afghan refugees in Iran | 2005–2010 | 23,152 refugees | Neoplasms represented 17% of referrals among Pashtun group |

| Shamseddine (2004) [64] | Lebanon | EMRO | Ecological study | Lebanese cancer patients following the 1975 -1990 Lebanese Civil War | 1998 | 4388 cases | Among males, the most frequently reported cancer was bladder (18.5%), followed by prostate (14.2%), and lung cancer (14.1%). In sharp contrast to countries worldwide, bladder cancer was notably high, in particular among males. Among females, breast cancer alone constituted around one third of the total cancer caseload in the country. This was followed by colon cancer (5.8%), and cancer of the corpus uteri (4.8%). The predominance of smoking related cancers highlights the importance of primary preventive strategies aimed at reducing smoking prevalence in Lebanon |

| Sibai (2001) [52] | Lebanon | EMRO | Retrospective cohort | Retrospective cohort study Lebanese aged 50 years and over residing in Beirut, Lebanon in 1983–1993 during the Lebanese Civil War | 1983–1993 | 1567 cases | In both sexes, the leading causes of death were non-communicable, mainly circulatory diseases (60%) and cancer (15%) |

| Telarovic (2006) [65] | Croatia | Europe | Cross sectional | Patients with CNS tumors admitted to the Department of Neurology of Pula General Hospital, Croatia during wartime | January 1986-December 2000 | 364 patients | There was a statistically significant increase of incidence rate ratios (IRR) of CNS tumors in war period versus the periods before and after war..Higher proportion of metastatic tumors than expected per the authors literature review. Authors relate to stress and PTSD |

Table 3.

Characteristics of included publications by disease type: Chronic Respiratory Disease

| Country/Territory of Interest | WHO region | Type of study | Target Population | Years of observation | Number of study participants | Major findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abul (2001) [66] | Kuwait | EMRO | Retrospective chart review | Patients admitted with asthma in Kuwait | 2001 | 12,113 asthma patients during the pre-Gulf War period compared with 9,771 patients during the post-Gulf War period | No significant difference between hospitalization or death rates pre and post Gulf War |

| Bijani (2002) [67] | Iran | EMRO | Retrospective chart review | Patients exposed to chemical weapons in northern Iran | 1994—1998 | 220 patients | Obstructive lung disease was a common finding amongst patients exposed to chemical weapons in Iran |

| Ebrahimi (2014) [68] | Iran | EMRO | Retrospective chart review | Patients with respiratory or cardiac diseases in Sanandaj, Iran | March 2009—June 2010 | – | Cardiac disease, but not respiratory disease, was significantly correlated with dust storm events |

| El-Sharif (2002) [69] | West Bank/Palestinian Territories | EMRO | Retrospective chart review | Schoolchildren in Ramallah District, Palestine | Autumn of 2000 | 3,382 children | Children from refugee camps appear to be at higher risk of asthma than children from neighboring villages or cities. Multivariate logistic regression confirmed that the estimated risk of having wheezing in the previous 12 months was higher for those residing in refugee camps than those living in neighboring villages and cities |

| Forouzan (2014) [70] | Iran | EMRO | Prospective observational | Patients presenting with asthma or bronchospasm in western Iran | Nov-13 | 2000 patients | Many patients presented with bronchospasm after a thunderstorm |

| Hung (2013) [42] | China | Western Pacific | Cross-sectional chart review | Patients presenting during 19 days following the Sichuan earthquake | Jun-08 | 2,034 patients | Musculoskeletal, respiratory, and GI problems were the top 3 areas and > 43% of patients had BP in HTN range |

| Kunii (2002) [71] | Indonesia | South-East Asia | Cross sectional | Patients exposed to air pollution in the “haze disaster” in Indonesia | September 1997 -October 1997 | 543 subjects | Patients had increased respiratory issues after a large forest fire disaster, especially the elderly. Wearing a high quality face mask was protective (vs handkerchief or simple surgical mask) |

| Lari (2014) [72] | Iran | EMRO | Cross sectional | Patients exposed to sulphur mustard gas | March 2010- April 2011 | 82 patients | The COPD Assessment Test (CAT) was found to be a valid tool for assessment of health related quality of life in chemical warfare patients with COPD |

| Mirsadraee (2011) [73] | Iran | EMRO | Retrospective Cohort | Patients whose parents were exposed to chemical warfare | – | 409 children | The prevalence of asthma was not significantly different in the offspring of chemical warfare victims |

| Molla (2014) [74] | Bangladesh | South-East Asia | Cross sectional | Children 5 years of age in Dhaka with diarrhea and asthma | September 2012 -November 2012 | 410 households | The DALYs lost due to asthma and diarrhea were significantly different amongst the climate refugee community than a non refugee group |

| Naumova (2007) [75] | Ecuador | Americas | Cross sectional chart review | ED patients after a volcanic eruption in Quito, Ecuador | January 2000 -December 2000 | 5,169 patients | Rate of ED visits for respiratory conditions significantly increased in 3 weeks after eruption. Rates of asthma and asthma related diagnosis double during volcano “fumarolic activity”. 345 excess ED visits in 4 weeks |

| Guha-Sapir(2007) [76] | Indonesia | South East Asia | Cross sectional | Patients attending an International Committee of the Red Cross(ICRC) field hospital in Aceh, Indonesia, established immediately after the tsunami in 2004 | 2 January 15, 2004- January 31 2,004,005–2010 | 1,188 study participants | Post tsunami, respiratory diseases were one of the most commonly recorded conditions (21.0%) and included acute asthma exacerbations |

| Redwood-Campbell (2006) [77] | Indonesia | South-East Asia | Cross Sectional | Patients registering in the ICRC field hospital in Banda Aceh after the tsunami | Mar-05 | 271 patients | 12% of the problems seen in the clinic 9 weeks after the tsunami were still directly related to the tsunami. Majority of patients were male, the problems were urologic, digestive, respiratory and musculoskeletal in that order. 24% had 4 or more depression/PTSD symptoms |

| Wright (2010) [78] | Kuwait | EMRO | Cross sectional | Patients in Kuwait following the Iraqi invasion | December 2003—January 2005 | 5028 subjects | Study suggested that those who reported highest stress exposure in the invasion were more than twice as likely to report asthma. Suggestive of correlation between war trauma and asthma |

Table 4.

Characteristics of included publications: Diabetes Mellitus

|

Country/ Territory of Interest |

WHO region | Type of study | Target Population | Years of observation | Number of study participants | Major findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abukhdeir (2013) [32] | Palestinian Territories: West Bank/Gaza | EMRO | Cross sectional | Palestinian households in the West Bank and Gaza Strip | May 2004—July 2004 | 4456 households in the West Bank and 2118 in the Gaza Strip | Being a refugee was a significant risk factor for diabetes and CVD while being married/engaged or divorced/separated/ widowed was a risk factor for diabetes and hypertension. Non-refugees were 33% less likely to have diabetes and 46% less likely to have CVD than refugees. Gender was a risk factor for hypertension with females being 60% more likely to have hypertension than males |

| Ahmad (2015) [33] | Syria | EMRO | Situational analysis using document analysis, key informant interviews, and direct clinic observation | Syrian national health system | October 2009 -August 2010 | 53 semi-structured interviews | The rebuilding of a post-conflict heath care system in Syria may benefit from insights into the structural problems of the pre-crisis system. Weaknesses that existed before the crisis are compounded by the current conflict. The authors suggest an over reliance on secondary and tertiary care for DM patients with withdrawal of the Syrian government from the public health clinics, which led to escalating healthcare costs and fostered increasingly unequal access |

| Alabed (2014) [79] |

Country of Asylum: Syria Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Cross sectional | Palestinian refugees living in Damascus attending three UNRWA health clinics | August 2008—September 2008 | 154 DM patients | UNRWA clinic inspections highlighted shortages in drug stocks with 47.3% of patients reporting problems accessing prescribed medications and 67.7% reporting having to buy medications at their own expense at least once since their diagnosis. Patients’ knowledge of their condition was limited, Patients were generally unaware of the importance of good glucose control and disease management. Women were more likely to attend the clinic than men, with 71% of patients being female |

| Ali-Shtayeh (2012) [80] | Palestinian Territories: West Bank | EMRO | Cross sectional | Patients attending outpatient departments at West Bank Governmental Hospitals in 7 towns in the Palestinian territories (Jenin, Nablus, Tulkarm, Qalqilia, Tubas, Ramalla, and Hebron) | August 2010—May 2011 | 1,883 DM patients | While all patients using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) were additionally using conventional therapies, the use of CAM differed significantly between residents of refugee camps versus residents of urban or rural areas (p = 0.034). More residents in a refugee camp reported using CAM vs. not using CAM as compared to those who reported living in a village or city. Most CAM users were above 40 years old, predominantly female, and residents of refugee camps and rural areas |

| AlKasseh (2013) [81] | Palestinian Territories: Gaza | EMRO | Retrospective case control | Refugee women attending the UNRWA postnatal clinics in Gaza | March 2011—June 2011 | 189 postnatal GDM women with 189 matched controls by age and place of residency | A history of miscarriage more than once, being overweight before pregnancy, history of stillbirth, history of caesarean birth and positive family history of diabetes mellitus were strongly correlated with developing gestational diabetes(GDM). WHO criteria for screening for GDM remain a good instrument to identify GDM in refugee populations in war-torn countries (like the Gaza Strip) |

| An (2014) [82] | China | Western Pacific | Retrospective cohort | 1976 Tangshan Earthquake survivors, aged 37–60, without severe liver disease, trauma surgery, secondary diabetes, or diagnosed mental disease | September 2013—December 2013 | 1030 exposed subjects | The incidences of impaired fasting glucose and DM for earthquake survivors were significantly higher than that for the control group. There was a higher diabetes incidence in those who had lost relatives than those who had not lost relatives, however, this effect was only statistically significant in women earthquake survivors |

| Armenian (1998) [83] | Armenia | Europe | Retrospective cohort | Employees of the Armenian Ministry of Health and their immediate families who survived the 1988 Earthquake in Armenia | 1990–1992 | 35,043 persons (7,721 employees who had survived the disaster and their family members) | Longer term increased rates of DM morbidity following an earthquake are related in a dose–response type relationship to the intensity of exposure to disaster. Bereavement, injuries in the family, and material loss, act as independent predictors of long term adverse physical illness including for DM |

| Balabanova (2009) [84] | Georgia | Europe | Rapid appraisal process with snowball sampling | Georgian health system evaluation | March—April 2006 | 36 interviews | Essential inputs for diabetes care are in place (free insulin, training for primary care physicians, financed package of care), but constraints within the system hamper the delivery of accessible and affordable care. The scope of work of primary care practitioners is limited and they rarely diagnose and manage diabetes, which instead takes place in the context of a hospital admission and tertiary-level endocrinologists. Obtaining syringes, supplies and hypoglycemic drugs and self-monitoring equipment remains difficult and leads to a cost driven shift toward insulin for diabetic management |

| Ben Romdhane (2015) [85] | Tunisia | EMRO | Situational analysis | Tunisian national health system | 2010 | 12 key informants were interviewed and eight documents were reviewed | Weaknesses that existed before the 2011 Revolution(Arab Spring) were compounded during the revolution. This study was conducted prior to political conflict but written post-conflict. Growth of the private sector fostered unequal access by socioeconomic status and reduced coordination and preparedness of the health system |

| Besancon (2015) [86] | Mali | Africa | Case study | Mali diabetic population following a March 2012 Coup in Bamako | Spring 2012 following the March 2012 coup | – | Diabetics are a vulnerable population in humanitarian crisis due to their continuous need for health care and medicines and the financial burden this may place on them. The authors propose that in an emergency setting there is not one single diabetes population that should be considered in planning humanitarian responses, but multiple, each with unique needs. These sub-populations include people still in active conflict regions, IDPs, refugees, and the population which houses IDPs |

| Ebling (2007) [87] | Croatia | Europe | Multipart study including both a retrospective cohort study and an uncontrolled before-after study | Refugee-returnees of the 1991–1992 war operations in Eastern Slavonia from Osjek-Baranga County, Croatia | 2003 |

retrospective cohort study: 589 participants uncontrolled before-after study 202 participants |

The participation of subjects with DM in the population of refugee-returnees despite similar demographic indicators, exceeded values for both Slavonia and Croatia. Extremely high participation of patients with diabetes was noted(10.5%), despite a lower proportion of aged people over 65 among returnees |

| Eljedi (2006) [88] | Palestinian Territories: Gaza | EMRO | Cross sectional | Patients with DM residing in refugee camps in Gaza Strip | November 2003—December 2004 | 197 DM patients | Using the World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF) four domains–including physical health, psychological, social relations, and environment – were strongly reduced in diabetic patients as compared to controls, with stronger effects in physical health (36.7 vs. 75.9 points of the 0–100 score) and psychological domains (34.8 vs. 70.0) and weaker effects in social relationships (52.4 vs. 71.4) and environment domains (23.4 vs. 36.2). The impact of diabetes on health-related quality of life (HRQOL). was especially severe among females and older subjects (above 50 years) |

| Gilder (2014) [89] |

Country of Asylum: Thailand Country of Origin: Myanmar |

South-East Asia | Cross sectional | Women attending the antenatal care (ANC) clinic in Maela refugee camp on the Thai–Myanmar border | July 2011—March 2012 | 228 women | The prevalence of GDM is lower in this population compared with other populations, but still complicates 10% of pregnancies. Despite the weight of evidence for the benefits of early diagnosis and treatment of GDM, the absence of a simple, inexpensive and applicable screening method remains a major barrier to GDM screening programs in refugee camps and other resource-poor settings |

| Habtu (1999) [90] | Ethiopia | Africa | Cross Sectional | Insulin treated diabetic patients from the Diabetic Clinic at the Mekelle Hospital in rural Tigray, Northern Ethiopia- the center of the severe Ethiopian famine of the mid-1980s | Six month period in 1997 | 100 patients | The correct prescribed dose of insulin was only being taken by 50% of patients and the correct syringe by only 12%. Insulin treatment had been interrupted in 48% of cases due to lack of supply. Low BMI(mean of 15.8), young age, and resistance to diabetic ketoacidosis(DKA) amongst study participants were consistent with previous descriptions of malnutrition related diabetes mellitus(MRDM) |

| Hult (2010) [42] | Nigeria | Africa | Retrospective Cohort | 40 year old Nigerians with fetal exposure to famine in Biafra, Nigeria during the Nigerian civil war (1967–1970) | June 2009–July 2009 | 1,339 study participants | Fetal and infant undernutrition was associated with significantly increased risk of impaired glucose tolerance in 40 year old Nigerians. However, early childhood exposure was not associated with increased risk |

| Kallab (2015) [44] |

Country of Asylum: Lebanon Country of Origin: Syria |

EMRO | Program implementation reflection | Syrian refugees and vulnerable Lebanese host communities over the age of 40 | November 2014- May 2015 | 1825 patients | DM accounted for 54% of patient cases, with 27% of patients affected by both DM and HTN. Principal barriers to providing diabetic management in active conflict included insecurity, the fluid movement of refugees, limited opening hours of the centers, transportation costs, and medication shortages |

| Karrouri (2014) [91] |

Country of Asylum: Tunisia Country of Origin: Libya |

EMRO | Case report | Case of a 10-year-old Libyan boy | – | One patient | Report of a 10 year old without personal or familial diabetes mellitus history who developed type 1 diabetes appeared immediately following severe psychological trauma |

| Khader (2012) [82] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Retrospective cohort | Persons with DM at Nuzha PHC Clinic | October 2009- March 2012 | 2,851 patients | A directly observed therapy(DOTS) cohort monitoring system can be successfully adapted and used to monitor and report on Palestinian refugees with DM in Jordan. A sizeable proportion of DM patients of the clinic failed to have postprandial blood glucose measurements, and BP measurements in those with comorbid HTN |

| Khader (2013) [77] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Retrospective cohort | Palestine refugees living in Jordan | October 2009- June 2013 | 12,549 total patients | High burden of disease due to DM amongst Palestinian refugees at UNRWA primary health care clinics in Jordan. Cohort analysis using e-Health is a successful tool for to assess management and follow-up of DM patients. Complications, including myocardial infarction and end-stage renal disease were significantly more common in males. Females were more likely to be obese |

| Khader (2014) [69] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Retrospective cohort | Palestinian refugees living in Jordan with DM attending Nunzha Clinic | 2012 | 2,974 DM patients | E-Health systems are useful for monitoring patients, since over half who miss their quarterly appointment fail to return. Suggests a need for monitoring and active follow-up |

| Khader (2014) [45] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Retrospective cohort | Palestinian refugees living in Jordan with DM attending Nunzha Clinic | 2010–2013 | 119 DM patients | E-health systems are useful for monitoring patients. An increasing number of patients had complications despite no change in obesity rates indicating places where more resources may be useful |

| Li (2010) [72] | China | Western Pacific | Retrospective cohort | Rural Chinese exposed to the Chinese famine(1959–1961) during fetal life and early childhood | 2002 | 7,874 rural Chinese | In severely affected famine areas, fetal-exposed adults had an increased risk of hyperglycemia compared with nonexposed subjects. Differences were not significant for the early and mid childhood–exposed cohorts. This association appears to be exacerbated by a nutritionally rich environment in later life |

| Lumey (2015) [92] | Ukraine | Europe | Retrospective cohort | Individuals exposed to the man-made Ukrainian famine of 1932–33 during prenatal development compared with all patients with type 2 diabetes diagnosed at age 40 years or older in the Ukraine national diabetes register 2000–08 | 2000–2008 | 43,150 patients with diabetes and 1,421,024 controls | Demonstrates a dose–response relationship between famine severity during prenatal development and odds of type 2 diabetes in later life. The associations between type 2 diabetes and famine around the time of birth were similar in men and women |

| Mansour (2008) [93] | Iraq | EMRO | Cross sectional | Diabetic patients in an outpatient clinic in Al-Faiha general hospital in Basrah, South Iraq | January 2007—December 2007 | 3,522 diabetic patients | The most common reasons for poor glycemic control(HBA1C > 7%) listed by patients were drug shortages and drugs and/or laboratory expense(over 50%). 30% of diabetic patient with poor glycemic control believed that their poor glycemic control is due to migration after the war |

| Mateen (2012) [48] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Iraq |

EMRO | Cross sectional | Iraqi refugees receiving health assistance in Jordan as recorded by a UNHCR database | January 2010-December 2010 | 7642 Iraqi refugees | 11% of refugees presented with type 2 DM. For all refugees the largest number of visits were for essential hypertension (2067 visits); visual disturbances (1129); type II diabetes mellitus (1021) |

| Mousa (2010) [50] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Gaza, West Bank Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Cross sectional | UNRWA registered Palestinian refugees attending UNRWA clinics | June 2007 | 7,762 refugees | Overall 9.8% of screened refugees had random blood glucose values ≥ 126 mg/dL. Being older than 40 years, obese or with a positive family history of diabetes or cardiovascular disease increased the risk of presenting with hyperglycemia 3.5, 1.6 and 1.2 times respectively. Variations were statistically significant between UNRWA locations and between the sexes. Significant variations were found between fields for females (χ2 = 112.6, P < 0.01) and for males (χ2 = 39.2, P < 0.01), with the highest proportion of cases diagnosed in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and the lowest in Jordan and Syria |

| Ramachandran (2006) [94] | India | South-East Asia | Retrospective cohort | Tsunami affected population of Chennai(Madras) in Southern India | April 2005- June 2005 | 1,184 tsunami affected subjects, 1,176 controls | Undetected diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance were higher in the tsunami-hit area as compared to controls. Diabetes prevalence was found to be similar in the tsunami affected population and control. Women of both the control and the tsunami affected population had both a higher stress score(using the Harvard trauma questionnaire) than men with a significantly higher stress score in women affected by the tsunami, as well as a higher prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance in the tsunami hit area |

| Read (2015) [67] | The Philippines | Western Pacific | Cross sectional | Patients treated by an Australian Government deployed surgical team in a field hospital in the city of Tacloban for 4 weeks after Typhoon Haiyan | November 2013 | 131 persons | Sepsis from foot injuries in diabetic patients constituted an unexpected majority of the workload of a foreign collaborative surgical medical team in Tacloban in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan |

| Sengul (2004) [95] | Turkey | Europe | Prospective cohort | Type 1 Diabetic Survivors of the 1999 Marmara Earthquake | 1998–2000 | 88 subjects | HbA1c levels and insulin requirements significantly increased at the 3rd month post earthquake however only increased insulin requirement continued to be significantly increased, one year post earthquake. No significant difference was identified between HbA1c levels pre earthquake and post 1 year earthquake. Results indicated that the Marmara earthquake affected glycemic control of people with type 1 diabetes in the short term but its negative impact did not continue in long term |

| Sofeh (2004) [94] |

Country of Asylum: Pakistan Country of Origin: Afghanistan |

EMRO | Cross sectional | Adult Afghan Refugees attending Red Cross health care facilities in Peshawar, Pakistan | . | 456 patients | The frequency of non-insulin dependent DM was found to be 55.9% amongst Afghan refugees in Peshawar during a two year study period. 17.25% of diabetics had concomitant hyperlipidemia. Gender was not identified as a risk factor for higher fasting blood glucose levels |

| Strong (2015) [53] |

Country of Asylum: Lebanon Country of Origin: Syria |

EMRO | Cross sectional | Syrian refugees over age 60 residing in Lebanon and registered with either Caritas Lebanon Migrant Center (CLMC) or the Palestinian Women’s Humanitarian Organization (PALWHO) | March 2011—March 2013 | 210 refugees | 47% of older refugees had DM. The number of days older refugees reporting eating bread only and nothing else corresponded to their reported financial status. Financial difficulties were given as the primary reason for not seeking care by 79% of older refugees with only 1.5% stating they had no difficulties in obtaining care when needed |

| Wagner (2016) [96] | Cambodia | Western Pacific | Uncontrolled before and after | Unpaid Cambodian village health guide volunteers were trained in DM prevention teaching behaviors | . | 185 guides were trained to instruct at 10 health centers | Knowledge of community health workers on DM prevention techniques increased significantly from pre-test to posttest after 6 months of follow-up. 159 guides (85%) completed at least one monthly checklist |

| Yaghi (2012) [97] | Lebanon | EMRO | Cross sectional | Cases of amputations in Lebanon | January 2007-December 2007 | 661 amputations | Diabetes and vascular indications were not only more common than trauma-related amputation, but both were associated with more major surgery and longer hospital stay including conflict afflicted southern Lebanon where trauma, diabetes and vascular disease amputations all occurred at more than twice the national rate |

| Yusef (2000)[22] |

Country of Asylum: Lebanon Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

EMRO | Cross sectional | Diabetic and hypertensive patients attending UNRWA primary health care facilities in Lebanon | 1997 | 2,202 records | Presence of both DM and HTN increased the risk for late-stage complications. Only 18.2% of diabetic patients and only 17.7% of DM patients with HTN were managed by lifestyle modification. About 50% of type 2 and 66% of type 1 patients who were on insulin were well controlled |

Table 5.

Characteristics of included publications by disease type: Other Non-Communicable Diseases

| Country/Territory of Interest | WHO region | Type of study | Target Population | Years of observation | Number of study participants | Major findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amini (2010) [98] | Iran | EMRO | Cross- sectional | Iranian war victims blinded in both eyes | 2007 | 250 conference attendees | Quality of Life (QOL) scores in blind war victims decreased with increasing age and additional medical comorbidities |

| Armenian (1998) [83] | Armenia | European | Prospective, nested case–control | Survivors of the 1988 Earthquake in Armenia | 1988–1992 | 35,043 employees of the Armenian Ministry of Health and their immediate families | During a 4-year follow-up period, the highest number of deaths from all causes (including heart disease) occurred within the first 6 months following the earthquake; associated with extent of disaster-related damage and losses |

| Chan (2010) [99] | Pakistan | EMRO | Cross sectional | Face-to-face, household-based survey conducted 4 months after the 2005 Kashmir, Pakistan earthquake in internally displaced camps near Muzafarabad city |

February 2006 4 months post-earthquake |

167 households | Although the proportion of the population with chronic conditions was similar across these studied camps, 85% of residents in the smallest unofficial camp had no available drugs to manage their chronic medical conditions as compared with their counterparts residing in larger rural unofficial (40%) and official camps (25%) |

| Chan (2009) [92] | Pakistan | EMRO | Comparative descriptive study | Patients ≥ 45 years who attended two different types of post-earthquake relief clinics during a 17-day field health needs assessment in response to the 2005 Kashmir earthquake |

February 2006 4 months post-earthquake |

30,000 patients in a rural site, and 382 IDPs in a urban site | The greatest gap in health services post-earthquake in both sites was non-communicable disease management. Clinical records reviewed in all study locations showed a systematic absence of documentation of common NCDs. In rural areas, older women were less likely to receive medical services while older men were less likely to access psychological services in both sites. During days when solely male doctors provided clinical services in the rural site, medical services utilization decreased by 30% |

| Hung (2013) [42] | China | Western Pacific | Cross-sectional chart review | Patients presenting during a 19 day period three weeks following the Sichuan earthquake | Jun-08 | 2,034 patients | Musculoskeletal, respiratory, and GI systems were top 3 problems and > 43% of patients met hypertension criteria |

| Khateri (2003) [100] | Iran | EMRO | Cross-sectional retrospective survey | Patients exposed to chemical weapons in Iran during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988) | 1997–2000 | 34,000 subjects | Lesions of the lungs (42.5%), eyes (39.3%), and skin (24.5%) were the most common sites of involvement among mustard agent exposure survivors |

| Leeuw (2014) [101] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan, Lebanon Country of Origin: Syria |

EMRO | Cross-sectional survey | Syrian refugee households in Jordan and Lebanon | 2013 | 3,202 refugees | Impairments found in 22% of refugees and disproportionately affecting those over 60 years of age (70% with at least 1 impairment) |

| Li (2011) [102] | China | Western Pacific | Cross-sectional survey | Adults exposed to severe famine in utero or as children | 2002 | 7,874 adults | Adults exposed to severe famine while in utero or early childhood had increased risk of metabolic syndrome |

| Mateen (2012) [31] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Iraq |

EMRO | Prospective observational | Iraqi refugees seeking health care in Jordan | 2010 | 7642 patients | Chronic diseases like hypertension (22%) and diabetes (11%) were common and the most common reason for visit was respiratory illness (11%) |

| Mateen (2012) [103] | 19 countries | Africa, EMRO, South East Asia | Retrospective chart review | Refugees in camp settings globally | 2008–2011 | 58,598 visits | Chronic, noncommunicable diseases like epilepsy and cerebrovascular disease far exceeded (> 98%) those for neurologic infectious diseases |

| McKenzie (2015) [62] |

Country of Asylum:Jordan Country of Origin: Syria, Iraq |

EMRO | Retrospective cohort | Syrian & Iraqi refugees applying for emergency or exceptional medical care | 2012–2013 | 223 refugees | Neuropsychiatric applications accounted for 11% of all Exceptional Care Committee applications and 2/3 of neuropsychiatric cases were for emergency care |

| Otoukesh (2012) [51] |

Country of Asylum: Iran Country of Origin: Afghanistan |

EMRO | Cross-sectional | Afghan refugees in Iran | 2005–2010 | 23,152 refugees | The most common health referral for those aged 15–59 years was ophthalmic diseases in females and nephropathies in males. In those aged 60 + it was ophthalmic diseases for both sexes |

| Redwood-Campbell (2006) [77] | Indonesia | South East Asia | Prospective observational | Patients registering in the ICRC field hospital in Banda Aceh 9 weeks after the tsunami | Mar-05 | 271 patients | 12% of clinic visits were directly related to the tsunami. The most common medical complaints were urological (19%), digestive (16%), respiratory (12%), and musculoskeletal (12%). 24% of patients had 4 or more depression/PTSD symptoms |

| Sibai (2001) [52] | Lebanon | EMRO | Cross-sectional | Representative cohort of men and women completing a health survey in Beirut, Lebanon during wartime | 1983–1993 | 1567 subjects | Total mortality rates were estimated at 33.7 and 25.2/1000 person years among men and women respectively. Leading cause of death was circulatory disease (60%) and cancer (15%) for both sexes |

| Strong (2015) [53] |

Country of Asylum: Lebanon Country of Origin: Syria, Palestine |

EMRO | Cross Sectional | Refugees over age 60 receiving assistance from social workers | 2011–2013 | 210 refugees | Most older refugees reported at least one non-communicable disease: hypertension (60%), diabetes (47%), heart disease (30%). 74% indicated at least some dependency on humanitarian assistance |

Table 6.

Characteristics of included publications by region: Africa

| Country/Territory of Interest | Target Population | Type of Study | NCD Studied | Years of Observation | Number of study participants | Major Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Besancon (2015) [86] | Mali | Mali diabetic population following a March 2012 Coup in Bamako | Case Study | Diabetes | Spring 2012 following the March 2012 coup | – | Diabetics are a vulnerable population in humanitarian crisis due to their continuous need for health care and medicines and the financial burden this may place on them. In an emergency setting sub-populations of diabetics must be taken into account for humanitarian response planning; including people still in active conflict regions, IDPs, refugees, and the host population which houses IDPs |

| Habtu (1999) [90] | Ethiopia | Insulin treated diabetic patients from the Diabetic Clinic at the Mekelle Hospital in rural Tigray, Northern Ethiopia- the center of the severe Ethiopian famine of the mid-1980s | Cross-sectional | Diabetes | Six month period in 1997 | 100 patients | The correct prescribed dose of insulin was only being administered in 50% of DM patients in rural Tigray, Ethiopia and the correct syringe by only 12% of patients. Insulin treatment had been interrupted in 48% of cases due to lack of supply. Low BMI(mean of 15.8), young age, and resistance to diabetic ketoacidosis(DKA) amongst study participants were consistent with previous descriptions of malnutrition related diabetes mellitus(MRDM) |

| Huerga (2009) [97] | Liberia | Patients of the medical and pediatric wards of Mamba Point Hospital, Monrovia, Liberia, one year after the end of the Liberian civil war | Cross-sectional | Multiple NCDs including CVD (stroke, CHF, and HTN) | January 2005—July 2005 |

1,034 adult patients 1,509 children |

Of 1034 adult hospitalized patients in post-war Liberia, 529 (51%) were diagnosed with a noninfectious disease. Among the 241 deaths recorded, the cause was non-infectious disease in 134 (56%) patients. The fatality rate for infectious diseases (19.7%; 92 deaths/465 cases) was lower (P = 0.04) than for non-infectious diseases (25.3%; 134 deaths/529 cases). Cardiovascular diseases caused half of deaths due to non-infectious diseases: 25% stroke, 18% heart failure and 10% severe hypertension. No cases of ischemic heart disease were identified Among hospitalized children, 229 (15%) were diagnosed with a noninfectious disease. NCDs represented 34% of all deaths. The fatality rate for infectious diseases (18.6%; 197 deaths/1189 cases) was lower (P < 0.01) than for non-infectious diseases (28.8%; 66 deaths/229 cases) |

| Hult (2010) [42] | Nigeria | 40 year old Nigerians with fetal exposure to famine in Biafra, Nigeria during the Nigerian civil war (1967–1970) | Retrospective cohort | Diabetes and HTN | June 2009–July 2009 | 1,339 study participants | Fetal and infant undernutrition was associated with significantly increased risk of hypertension(adjusted OR 2.87; 95% CI 1.90–4.34), and impaired glucose tolerance (OR 1.65; 95% CI 1.02–2.69) in 40 year old Nigerians. However, early childhood exposure was not associated with increased risk |

Table 7.

Characteristics of included publications by region: Region of the Americas

| Country/Territory of Interest | Target Population | Type of Study | NCD Studied | Years of Observation | Number of study participants | Major Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniels (2009) [104] | Peru | Displaced as well as nondisplaced populations in rural to urban settings | Stratified cluster survey | Multiple NCDs | 2007 (six months post-earthquake) | 672 households | Displaced populations sought care more, people with injury or NCD sought care more. People who did not seek care cited cost as a barrier |

| Naumova(2007) [75] | Ecuador | Pediatric ER visits with acute upper and lower respiratory conditions and asthma related conditions | Retrospective review of medical records | Chronic respiratory disease including asthma | January – 2000 December 2000 | 5,169 emergency department records | Rates of ED visits for pediatric patients increased significantly during period of volcanic activity. Youngest patients (4 and under) were most affected |

Table 8.

Characteristics of included publications by region: Eastern Mediterranean Region

|

Country/ Territory of Interest |

Target Population | Type of study | NCD studied | Years of observation | Number of study participants | Major findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abukhdeir (2013) [32] | Palestinian Territories-Gaza/ West Bank | Palestinian households in the West Bank and Gaza Strip | Cross-sectional nationally representative household survey | Diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer | 2013 | 4,456 households in the West Bank and 2118 in the Gaza Strip. The response rates for the 2 regions were 84.1% and 96.9% respectively | The authors emphasized that even though previous studies have combined Palestinians as one group, they live in different areas and are subject to different health systems which can result in different health outcomes. Being a refugee was a significant risk factor for diabetes and CVD while being married/engaged or divorced/ separated widowed was a risk factor for diabetes and hypertension. Non-refugees were 33% less likely to have diabetes and 46% less likely to have CVD than refugees |

| Abul (2001) [66] | Kuwait | Patients admitted to hospitals in Kuwait with asthma for six years (1987–1989 and 1992–1994) | Retrospective cross-sectional study | Asthma | 2001 | 12,113 asthma patients during the pre-Gulf War period compared with 9,771 patients during the post-Gulf War period | During the war, a lot of oil wells were burned, giving suspicion to the potential for increase in asthma. No statistically significant difference in hospital admissions for to death rates attributable to asthma in the pre- and post-Gulf War periods in Kuwait. Notably, the war was 1990/1991, and no data is available for those years, so the immediate effect isn’t known |

| Ahmad (2015) [33] | Syria | Syrian national health system | Situational analysis using document analysis, key informant interviews, and direct clinic observation | Diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD | October 2009 -August 2010 | 53 semi-structured interviews | The rebuilding of a post-conflict heath care system in Syria may benefit from insights into the structural problems of the pre-crisis system. Weaknesses that existed before the crisis are compounded by the current conflict. The authors suggest an over reliance on secondary and tertiary care for DM patients with withdrawal of the Syrian government from the public health clinics, which led to escalating healthcare costs and fostered increasingly unequal access |

| Alabed (2014) [79] |

Country of Asylum: Syria Country of Origin: Palestinian Territories |

Palestinian refugees living in Damascus attending three UNRWA health clinics | Cross sectional | Diabetes | August 2008—September 2008 | 154 DM patients | UNRWA clinic inspections highlighted shortages in drug stocks with 47.3% of patients reporting problems accessing prescribed medications and 67.7% reporting having to buy medications at their own expense at least once since their diagnosis. Patients’ knowledge of their condition was limited, Patients were generally unaware of the importance of good glucose control and disease management. Women were more likely to attend the clinic than men, with 71% of patients being female |

| Ali-Shtayeh (2012) [80] | Palestinian Territories-West Bank | Patients attending outpatient departments at Governmental Hospitals in 7 towns in the Palestinian territories (Jenin, Nablus, Tulkarm, Qalqilia, Tubas, Ramalla, and Hebron) | Cross-sectional survey | Diabetes | August 2010—May 2011 | 1,883 DM patients | The use of CAM differed significantly between residents of refugee camps versus residents of urban or rural areas (p = 0.034). Those who were on CAM reported they were using it to slow down the progression of the disease or relieve symptoms. All patients with DM who used CAM were also on conventional therapies |

| AlKasseh (2014)[81] | Palestinian Territories-Gaza | Patients at UNRWA clinics within Gaza | Retrospective case–control study | Gestational diabetes (GDM) | March 2011—June 2011 | 189 postnatal GDM women with 189 matched controls by age and place of residency | The present study showed that history of miscarriage more than once, being overweight before pregnancy, history of stillbirth, history of caesarean birth and positive family history of diabetes mellitus were strongly correlated with developing GDM. The WHO criteria for screening for GDM remains a good instrument to identify GDM in refugee populations in war-torn countries (like the Gaza Strip) |

| Amini (2010) [98] | Iran | Completely blind Iranian survivors of the Iran-Iraq War | Cross-sectional study | Multiple NCDs including hypertension, Hypercholesterolemia, and erectile dysfunction | 2010 | 250 Iran-Iraq war survivors | As blind war survivors’ age, they will present with a greater set of burdens despite their relatively better quality of life (QOL) in the physical component scale when compared with lower limb amputees. Risk factors of cardiovascular attack such as high blood pressure and hypercholesterolemia were present: High systolic and diastolic blood pressure, hearing loss, and tinnitus had negative individual correlations to (QOL) (p = 0.016, 0.016, 0.005, p < 0.0001). Hypercholesterolemia showed significant correlation to QOL (p = 0.021) |

| Bijani (2002) [105] | Iran | Iranians injured by chemical weapons during the Iraq–Iran war who are under services of the Mostazafan and Janbazan Foundations of Babol, Iran | Cross-sectional | Chronic respiratory diseases | 1994—1998 | 220 patients | The clinical evaluations, radiography, and PFTs revealed that the most prevalent effects of chemical weapons on respiratory tract were chronic obstructive lung disease. Victims of suphorous gas had demonstrated involvement of airways during acute and chronic phases of injury, however over time clinical manifestations, radiography, and PFT gradually became normal. Most patients reported mustard gas exposure.. Chest X-Ray was not reliable to diagnose lung injury in these patients. Diagnosis was completed most accurately by PFTs |

| Ben Romdhane (2015) [85] | Tunisia | Tunisian national health system | Situational analysis | Cardiovascular disease and diabetes | 2010 | 12 key informants were interviewed and eight documents were reviewed | Weaknesses that existed before the 2011 Revolution(Arab Spring) were compounded during the revolution. This study was conducted prior to political conflict but written post-conflict. Growth of the private sector fostered unequal access by socioeconomic status and reduced coordination and preparedness of the health system |

| Chan (2009) [106] | Pakistan | Patients ≥ 45 years who attended two different types of post-earthquake relief clinics during a 17-day field health needs assessment in response to the 2005 Kashmir earthquake | Comparative descriptive study | Multiple NCDs |

February 2006 4 months post-earthquake |

30,000 patients in a rural site, and 382 IDPs in a urban site | The greatest gap in health services post-earthquake in both sites was non-communicable disease management. Clinical records reviewed in all study locations showed a systematic absence of documentation of common NCDs. In rural areas, older women were less likely to receive medical services while older men were less likely to access psychological services in both sites. During days when solely male doctors provided clinical services in the rural site, medical services utilization decreased by 30% |

| Chan (2010) [99] | Pakistan |

Face-to-face, household-based survey conducted 4 months after the 2005 Kashmir, Pakistan earthquake in internally displaced camps near Muzafarabad city |

Cross sectional | Multiple NCDs |

February 2006 4 months post-earthquake |

167 households | Although the proportion of the population with chronic conditions was similar across these studied camps, 85% of residents in the smallest unofficial camp had no available drugs to manage their chronic medical conditions as compared with their counterparts residing in larger rural unofficial (40%) and official camps (25%) |

| Doocy (2013) [107] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan/ Syria Country of Origin: Iraq |

Iraqi populations displaced in Jordan and Syria | Cross-sectional | Disability and multiple NCDs including hypertension, arthritis, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, and cardiovascular disease | October 2008-March 2009 | 1200 and 813 Iraqi households in Jordan and Syria, respectively | Chronic disease prevalence among adults was 51.5% in Syria and 41.0% in Jordan, with hypertension and musculoskeletal problems most common. Overall disability rates were 7.1% in Syria and 3.4% in Jordan, with the majority of disability attributed to conflict and depression the leading cause of mental health disability |

| Doocy (2015) [108] |

Country of Asylum: Jordan Country of Origin: Syria |

Syrian refugees in non-camp settings in Jordan | Cross-sectional survey | Multiple NCDs including hypertension, arthritis, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases, and cardiovascular disease | 1994—1998 | 1,550 refugees | More than half of Syrian refugee households in Jordan reported a member with an NCD. Among adults, hypertension prevalence was the highest (9.7%, CI: 8.8–10.6). While care-seeking was high (85%) among those reporting a NCD, among those who did not seek care, cost was the primary reason |