Abstract

Introduction.

Transactional developmental and anxiety theories suggest that mothers and toddlers may influence each other’s anxiety development across early childhood. Further, toddlers’ successful solicitations of comfort during uncertain, yet manageable, situations, may be a behavioral mechanism by which mothers and toddlers impact each other over time. To test these ideas, the current study employed a longitudinal design to investigate bidirectional relations between maternal anxiety and toddler anxiety risk (observed inhibited temperament and mother-perceived anxiety, analyzed separately), through the mediating role of toddler-solicited maternal comforting behavior, across toddlerhood.

Methods.

Mothers (n = 174; 93.6% European American) and their toddlers (42.4% female; 83.7% European American) participated in laboratory assessments at child ages 1, 2, and 3 years. Mothers self-reported anxiety symptoms. Toddler anxiety risk was observed in the laboratory as inhibited temperament and reported by mothers. Solicited comforting interactions were observed across standardized laboratory tasks.

Results.

Direct and indirect bidirectional effects were tested simultaneously in two longitudinal path models. Toddler anxiety risk, but not maternal anxiety, predicted solicited comforting behavior, and solicited comforting behavior predicted maternal anxiety. No convincing evidence for parent-directed effects on toddler anxiety risk emerged.

Conclusion.

Results support continued emphasis on child-elicited effects in child and parent anxiety development in early childhood

Keywords: Anxiety/anxiety disorders, child/adolescent, maternal-child

Transactional theory (Sameroff, 2009) indicates the possibility of bidirectional relations between maternal anxiety and toddler anxiety risk. Toddlers display meaningful, yet malleable, individual differences in anxiety risk in the form of inhibited temperament, characterized by wariness and withdrawal in the presence of novelty or uncertainty (Bayer et al., 2019; Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2009; Fox et al., 2005; Kagan et al., 1984; Perez-Edgar & Guyer, 2014), or early emerging anxiety symptoms (Battaglia et al., 2016; Briggs-Gowan et al., 2006). Although fathers and other socializers also have anxiety-relevant dynamic relationships with children (Bögels & Phares, 2008), mothers face unique parenting demands and possible continued effects of postpartum anxiety (Mughal et al., 2018). Maternal anxiety may include physiological hyperarousal, worry, and social evaluative concerns (Kerns et al., 2011; Kiel & Kalomiris, 2016; Lawrence et al., 2020; Poole et al., 2018). Beyond shared mother-child genetic influences (Li et al., 2008; Mughal et al., 2018), mothers and toddlers may mutually influence each other’s anxiety. Maternal anxiety in infancy/toddlerhood has predicted preschool/school-aged children’s internalizing problems (Gjerde et al., 2020; Hentges et al., 2020), and maternal anxiety has predicted increased child anxiety in middle childhood (Kerns et al., 2011; Poole et al., 2018). Child-directed effects of broader temperament (e.g. effortful control, negative emotionality) on parents’ psychological functioning and parenting have been found in the preschool/school years (Allmann et al., 2016; Klein et al., 2018; Oddi et al., 2013). The literature is still missing fully bidirectional longitudinal studies in early childhood that control for stability in anxiety (or anxiety risk). Further, anxiety-prone children may elicit specific parenting behaviors linked to maternal and child anxiety (Gouze et al., 2017; Rubin et al., 1999), and parenting behavior has been identified as a mechanism by which parent anxiety relates to toddler anxiety risk (Metz et al., 2018), motivating our investigation of a behavioral mechanism of bidirectional effects.

According to anxiety and parenting theories, behavioral parent-child interactions surrounding anxiety-prone children’s reassurance seeking behaviors may be the route through which maternal and child anxiety influence one another (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Dadds & Roth, 2001). Anxiety-prone children attempt to elicit their parents’ assistance in avoiding feared situations and consequent distress (Dadds & Roth, 2001). In early childhood, physical comfort is a primary means by which parents respond to child distress. Toddler-solicited comforting behaviors are physically reassuring behaviors (e.g., physical contact, active soothing, hugging or embracing) enacted by the parent in direct response to the toddler’s bid for comfort or reassurance. Although spontaneous parental comfort could also undermine toddlers’ independent regulation, children’s bids for comfort and may be particularly relevant to transactional parent- child processes by actively drawing parents into behavioral patterns that contingently reinforce anxious responses. Toddlers’ anxiety-proneness has been directly linked to solicited responses of comforting and protection (Kiel & Buss, 2012). Maternal anxiety may also contribute to mothers’ comforting responses. Anxious mothers may overestimate threat in their children’s environments and ineffectively manage their own emotional reactions in such situations (Abramowitz & Blakely, 2020; Kerns et al., 2017). Mothers may avoid distress through comforting their children instead of using more approach-based or autonomy-encouraging strategies. Parenting constructs including responsiveness and warmth have been associated with maternal anxiety and its features (Coplan et al., 2008; Kerns et al., 2017; Kiel & Maack, 2012). Thus, both child anxiety-proneness and maternal anxiety may predict solicited maternal comforting behavior.

Solicited maternal comforting behavior may subsequently predict future anxiety (risk) in both toddlers and mothers. Physical comfort is an adaptive response when the demands of the situation outweigh toddlers’ capacities for independent regulation, but physical comfort may reinforce toddlers’ avoidance when facing uncertain, yet manageable, situations (Fox et al.,2005; Rubin et al., 2009). Physical comfort provides toddlers relief from physiological arousal caused by uncertainty and could diminish toddlers’ motivation to approach someone or something new. Physical comfort has been theorized to prevent children’s development of independent regulation (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Rubin et al., 2009) and empirically shown to attenuate anxiety-prone children’s engagement in regulatory behaviors (Kiel et al., 2020). Extreme levels of maternal sensitivity, comforting, and support have predicted child anxiety-relevant outcomes (Bayer et al., 2019; Kiel & Buss, 2012, 2014; Mount et al., 2010). Comforting behavior may also reinforce mothers’ avoidance of situations that potentially cause their children distress; this avoidance may feed back into mothers’ own anxiety, evidence for which would augment theory surrounding parenting. Existing studies directly support a mechanistic role of parenting behavior in the relation between maternal anxiety and child outcomes (Cooklin et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2015; Kerns et al., 2017; Kiel & Maack, 2012) some of which have employed longitudinal designs with observational and parent-report methods (Metz et al., 2018; de Vente et al., 2020). The prediction from child anxiety to maternal anxiety through maternal parenting has yet to be studied.

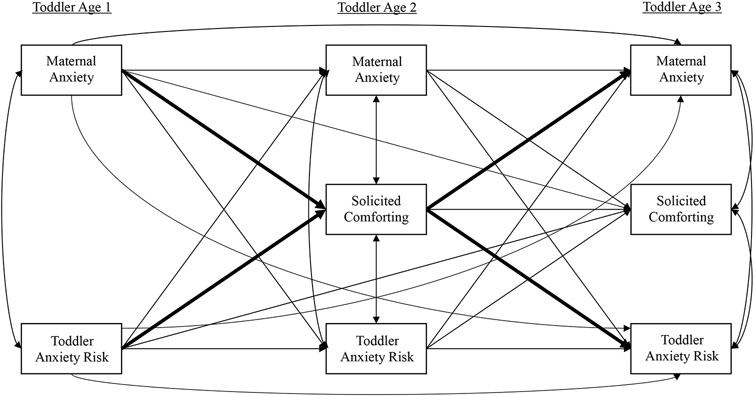

The current study addressed the need to test a fully transactional model of mother and toddler anxiety incorporating a maternal behavioral mechanism. Our longitudinal design included repeated measures of toddler anxiety risk and maternal anxiety at toddler ages 1, 2, and 3 years to simultaneously discern parent-driven and child-driven relations. We measured toddler-solicited comforting at ages 2 and 3 years because older toddlers are more independently mobile and more capable of autonomous exploration. To account for complementary strengths and limitations to studying temperament, we analyzed observed inhibited temperament and mother- perceived toddler anxiety separately. Our conceptual model (Figure 1) allowed us to test the following hypotheses while simultaneously accounting for stability in constructs, as well as direct transactional relations not accounted for by our hypothesized behavioral mechanism. We hypothesized that both maternal anxiety and toddler anxiety risk at toddler age 1 would predict toddler-solicited maternal comforting behavior at toddler age 2 (H1). We hypothesized that toddler-elicited maternal comforting behavior at age 2 would subsequently predict both maternal anxiety and toddler risk at toddler age 3 (H2). Finally, we hypothesized that toddler-solicited maternal comforting would indirectly link maternal anxiety at toddler age 1 to toddler anxiety risk at age 3, as well as from toddler anxiety risk at age 1 to maternal anxiety at toddler age 3 (H3).

Figure 1. Conceptual Model of Mediated Transactional Effects.

Note. Above and beyond stability and transactional associations occurring outside of our proposed behavioral mechanism, we hypothesized (as denoted by bolded paths) that maternal anxiety and toddler anxiety risk would both predict toddler-solicited maternal comforting behavior, that comforting would predict both maternal anxiety and toddler anxiety risk, and that comforting would indirectly link age 1 toddler anxiety risk to maternal anxiety at toddler age 3, and maternal anxiety at toddler age 1 to toddler age 3 anxiety risk. Correlated errors acknowledge shared variance occurring through non-behavioral mechanisms (e.g., genetics).

Method

Participants

Participants included 174 mothers and their toddlers (42.4% female) enrolled in a larger longitudinal study, involving assessments at child age 1 (T1), 2 (T2), and 3 (T3) years. We recruited mothers and their typically developing children from the community, including at the local Women’s, Infants, and Children’s office, in a modified accelerated longitudinal design; planned missingness (like planned wave-missing designs; Little & Rhemtulla, 2013), handled with contemporary statistical approaches, allowed for larger total sample size in a shorter longitudinal period. Most families (cohort 1; n = 125; 56 female toddlers) were recruited at T1 (toddlers: Mage = 14.12 months, SDage = 1.35; Range = 12.02 to 18.17; mothers: Mage = 30.81 years, SD = 5.51, Range = 18.57 to 45.24). Nearly simultaneously, we recruited a smaller number of families (cohort 2; n = 49, 16 female toddlers) for T2, yielding the total 174 families. Ninety-eight cohort 1 families (78.4%) returned for T2, yielding 147 families at T2 (62 female toddlers: Mage = 26.89 months, SD = 2.00; Range = 23.49 to 33.05; mothers: Mage = 32.34 years, SD = 5.59, Range = 19.67 to 46.35). Across cohorts, 105 families (71.4% of T2 participants; 29.2% did not participate in T1) participated at T3 (42 female toddlers: Mage = 39.44 months, SD = 2.27, Range = 35.84 to 45.80; mothers: Mage = 33.74 years, SD = 5.37, Range = 20.50 to 47.46). Cohorts did not significantly differ on child sex distribution, maternal age, maternal education, or household income at either T2 or T3.

Mothers reported their own and their children’s racial identity, respectively, to be Black/African American (1.2%, 1.2%), Asian/Asian American or Pacific Islander (2.9%, 1.2%), White/European American (93.6%, 83.7%), Native American (.6%, .6%), or multiracial/other (1.7%, 13.3%). Mothers reported their own and their child’s ethnicity as 2.3% and 4.7% Hispanic/Latina, respectively. Maternal education ranged from 9 to 21 years (M = 15.30, SD = 2.63). Household income ranged from < $15,000 to > $81,000 (Mean = $41,000 - $50,000).Most toddlers (72.4%) had siblings (median = 1, range = 0-7).

Procedure

(Miami University's Institutional Review Board approved procedures.)’s Institutional Review Board approved procedures. At the T1 laboratory visit, the primary experimenter (E1) completed consent procedures and explained laboratory activities with the mother. For the inhibited temperament procedure (Calkins et al., 1996; Fox et al., 2001), E1 showed the dyad into a room with an assortment of toys. After 5 minutes of free play and brief mother-toddler clean-up period, a second experimenter (E2) entered and sat quietly for 1 minute without interacting. E2 then played with a dump truck and blocks, a toy robot, and a tunnel. E2 provided prompts at pre-determined intervals if the toddler did not approach. The mother completed questionnaires regarding her own and her toddler’s anxiety.

At T2, mothers completed questionnaires, and dyads participated in the inhibited temperament procedure as at T1. The dyad also engaged in Clown and Puppet Show episodes (Buss, 2011), for which E1 instructed the mother to interact with her toddler naturally for later scoring of solicited comforting behavior. For Clown, E2, dressed as a friendly clown with a wig, clown suit, and red nose, entered and invited the toddler to play with bubbles, beach balls, and musical instruments (1 min each) before cleaning up and exiting the room. For Puppet Show, E2 sat behind a wooden stage and interacted via two puppets. The puppets invited the child to play catch (1 min), fishing (1 min), and sticker prize retrieval before E2 emerged from behind the stage, removed the puppets, and exited the room. T3 procedures were identical to T2.

Measures

Maternal anxiety.

Mothers self-reported their anxiety using three well-established measures. The 7-item Anxiety subscale (αs = .64-, 84) of the 21-item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS 21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) asked mothers to rate statements of symptoms for the past week from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much most of the time). Items were summed and multiplied by 2 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer et al., 1990) is a 16-item measure of non- normative worry. Mothers rated how typically the statements applied to them from 1 (not at all typical) to 5 (very typical of me). Items were reversed if necessary and summed (αs = .94). The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998) is a 20-item measure of anxiety-driven social difficulties rated from 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Items were reversed if necessary and summed (αs = .93-,94). Sixty-two mothers (35.6%) reported at least one score above the published clinical/severe cutoff (Behar et al., 2003; Brown et al., 1997; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) for at least one timepoint. Measures were intercorrelated (rs = .42 to .51 at T1,.35 to .54 at T2, .31 to .61 at T3; allps < .01). Thus, within each time-point, we standardized and averaged the three scores to create a final maternal anxiety composite.

Mother-perceived toddler anxiety.

Mothers completed the Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, 2003), which measures a toddler’s difficulties and competencies on a 0 (not true or rarely true) to 2 (very true or often true) scale. We averaged 16 items (αs = .78 - .81) reflecting inhibition to novelty, anxiety/worry, and separation distress for the mother-perceived toddler anxiety risk variable.

Observed toddler inhibited temperament.

Coders scored toddler behaviors from the Free Play, Stranger/Dumptruck (S), Robot (R), and Tunnel (T) episodes of the battery according to established procedures (Fox et al., 2001; Fox et al., 1995; Calkins, Fox, & Marshall, 1996) using Interact software (Mangold, 2017). Behaviors were reliably scored as present/absent on a frame-by-frame basis continuously within each episode (rs = 90- .99, rmean = .96). Principal Components Analysis of T1 coding revealed 16 behaviors that coalesced coherently: duration (in seconds) of proximity to mother (within 2 ft) while not playing (S, R, T), count of non-distress vocalizations (reversed; S), duration of playing in proximity (within 2 ft) of the stranger (reversed; S, R), latency (in seconds) to approach the stranger or objects (S, R), latency to touch the stranger or objects (S, R), duration of freezing (S, R), duration of vigilant stare (S, R, T), and duration of touching the robot (R). We averaged the Z-scored values of the 16 codes (αs: = .92 to .93). To maintain consistency across ages, the same composite was created at all three timepoints.

Solicited comforting behavior.

Clown and Puppet Show episodes were scored according to an established coding scheme (Kiel & Buss, 2010). Mothers’ comforting behavior was scored as 0 (no comforting behavior), 1 (touching child in still manner), 2 (active soothing such as rubbing back) or 3 (hugging of the child and/or kissing child) each 10-sec epoch of each episode. Each comforting behavior was also scored as solicited or unsolicited. Inter-rater reliability, conducted at the level of epoch, was adequate for Clown (ICC = .90) and Puppet Show (ICC = .81). Scores for solicited behaviors, only, were averaged across epochs within an episode, yielding a weighted proportion score (multiplied by 100 for interpretability). We averaged scores across episodes given the correlation (r =.26, p <.05 at T2, r = .29, p = .07), yielding a final score of solicited comforting behavior at T2 and T3.

Coding.

Coders received extensive training and achieved inter-rater reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] > .80, or correlation > .90) with a master coder before coding independently. The master coder double-scored approximately 20% of cases throughout coding to prevent coder drift.

Results

Missing Data

Outside of planned missingness, missing values (Table 1) occurred for observed variables typically because of technical problems or child non-compliance, and for survey measures typically because mothers did not complete the questionnaire packet; a few mothers had to leave the lab prior to in-lab questionnaire completion. Compared to retained mothers, mothers lost to attrition (21.6% at T2 and 28.6% at T3) reported lower socioeconomic status and higher T1 anxiety; attrition did not relate to child biological sex or T1/T2 primary variables (Table 2). Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test, including primary and demographic variables, suggested that the pattern of missingness did not deviate from the MCAR pattern (χ2[865] = 881.02,p = .345). In line with recommendations for planned missingness designs (Little & Rhemtulla, 2013), all missing values (including those occurring because families were recruited after earlier time points) were handled in primary models with Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation, informed by SES as an auxiliary variable.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics across Assessments

| Variable | Time 1 |

Time 2 |

Time 3 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Observed inhibited temperament | 124 | −0.02 (0.67) | −1.31-1.90 | 137 | 0.01 (0.67) | −1.23-1.58 | 100 | 0.04 (0.69) | −1.02-1.94 |

| S: Not playing, in prox to M (dur) | 55.67 (60.35) | 0-235.48 | 78.60 (62.40) | 0-224.64 | 90.28 (57.11) | 0-212.48 | |||

| S: Non-distressed vocs (count) | 7.91 (6.97) | 0-34 | 9.66 (8.50) | 0-50 | 11.03 (9.40) | 0-42 | |||

| S: Playing in prox of S (dur) | 33.05 (32.17) | 0-120.48 | 30.30 (29.57) | 0-152.12 | 31.15 (30.68) | 0-125.98 | |||

| S: Latency to approach S | 111.03 (100.44) | 2.52-291 | 120.38 (71.53) | 2.76-239 | 122.24 (69.44) | 2.13-244 | |||

| S: Freezing (dur) | 10.29 (20.42) | 0-133 | 19.87 (24.44) | 0-111.94 | 30.24 (33.48) | 0-160.69 | |||

| S: Vigilant stare (dur) | 51.31 (43.97) | 0-155.60 | 45.19 (37.48) | 0-169.84 | 53.36 (42.13) | 0-200.72 | |||

| S: Latency to touch simulus | 179.80 (96.25) | 49.65-291 | 137.95 (67.57) | 18.77-239 | 138.98 (67.49) | 28.14-244 | |||

| R: Not playing, in prox to M (dur) | 31.86 (38.62) | 0-153.04 | 37.43 (40.71) | 0-147.97 | 31.44 (38.79) | 0-123.85 | |||

| R: Latency to touch stimulus | 78.05 (71.48) | 0-160 | 100.35 (75.50) | 0-168 | 120.42 (84.89) | 0-195 | |||

| R: Playing in prox of S (dur) | 14.36 (24.68) | 0-136.84 | 23.46 (34.56) | 0-131.08 | 32.03 (39.15) | 0-125.61 | |||

| R: Latency to approach R | 71.62 (72.65) | 0-160 | 67.00 (74.55) | 0-168 | 73.41 (85.57) | 0-195 | |||

| R: Freezing (dur) | 23.34 (26.13) | 0-109.64 | 19.18 (23.76) | 0-96.86 | 21.92 (27.19) | 0-117.69 | |||

| R: Vigilant stare (dur) | 47.27 (30.09) | 0-121.39 | 35.79 (32.29) | 0-112.64 | 33.96 (33.57) | 0-123.85 | |||

| R: Touching R (dur) | 15.86 (25.21) | 0-136.76 | 13.35 (23.02) | 0-131.53 | 9.36 (17.84) | 0-81.88 | |||

| T: Not playing, in prox to M (dur) | 18.04 (20.30) | 0-75.06 | 9.12 (14.41) | 0-56.76 | 7.70 (13.96) | 0-54.87 | |||

| T: Vigilant stare (dur) | 6.81 (10.27) | 0-51.07 | 4.61 (8.89) | 0-45.60 | 2.09 (6.20) | 0-36.42 | |||

| Mother-reported toddler anxiety | 113 | 0.62 (0.31) | 0.11-2.00 | 135 | 0.68 (0.32) | 0.05-1.51 | 93 | 0.67 (0.30) | 0.06-1.35 |

| Maternal anxiety | 125 | 0.05 (0.87) | −1.22-3.44 | 143 | 0.04 (0.85) | −1.20-4.06 | 104 | 0.03 (0.83) | −1.48-2.54 |

| DASS anxiety | 118 | 2.97 (4.88) | 0-26 | 132 | 3.39 (6.11) | 0-34 | 96 | 2.74 (4.29) | 0-24 |

| PSWQ total score | 122 | 45.87 (13.36) | 21-77 | 140 | 44.60 (13.65) | 20-77 | 102 | 42.26 (13.48) | 18-75 |

| SIAS total score | 122 | 22.41 (12.94) | 1-51 | 140 | 21.64 (14.03) | 0-54 | 103 | 22.02 (15.06) | 0-63 |

| Solicited comforting behavior | -- | -- | -- | 138 | 9.65 (15.14) | 0-93 | 103 | 10.89 (16.44) | 0-78 |

Note. S = Stranger. R = Robot. T = Tunnel.

Table 2.

Comparisons between Retained Families and Families Lost to Attrition

| Variable | Retained |

Lost to Attrition |

t/-test (df) | P | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Socioeconomic Status | 0.19 | 0.85 | −0.29 | 0.95 | −3.34 (166) | .001 | −0.53 |

| Toddler observed inhibited temp T1 | −0.02 | 0.66 | −0.03 | 0.68 | −0.01 (122) | .994 | −0.00 |

| Toddler observed inhibited temp T2 | 0.02 | 0.67 | −0.00 | 0.64 | −0.18 (135) | .859 | −0.03 |

| Mother-perceived toddler anxiety T1 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.63 | 0.29 | 0.16 (111) | .875 | 0.03 |

| Mother-perceived toddler anxiety T2 | 0.67 | 0.32 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 0.52 (133) | .604 | 0.10 |

| Maternal anxiety T1 | −0.09 | 0.73 | 0.26 | 1.01 | 2.30 (123) | .023 | 0.40 |

| Maternal anxiety T2 | −0.04 | 0.85 | 0.23 | 0.86 | 1.66 (141) | .098 | 0.31 |

Note. Socioeconomic status was a composite of Z-scored income and maternal education. Inhibited temperament variables and maternal anxiety variables were means of Z-scored components. Levene’s test for equality of variances was non-significant (p > .05) in all cases. T1 = Time 1. T2 = Time 2. Retained families versus families lost to attrition did not differ according to toddler biological sex (χ2[l] = 0.21, p = .649).

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Relations

Descriptive statistics for primary variables are reported in Table 1. No variables exhibited severe deviations from normality (all |skew| < 3.00, all |kurtosis| < 10.00; Kline, 2016). Maternal age at the time of the child’s birth related to T3 maternal anxiety, so it was included as a covariate in primary path models. No other demographic variables related to dependent variables, so they were not considered further.

Bivariate correlations among primary variables are presented in Table 3. Stability occurred across assessments of maternal anxiety (large effects), observed inhibited temperament (medium effects), mother-reported toddler anxiety (medium to large effects), and solicited comforting behavior (medium effect). Correlations were generally of low magnitude and non-significant between maternal anxiety and observed inhibited temperament, with the exception that T1 inhibited temperament related to T3 maternal anxiety. T1 and T2 (but not T3) observed inhibited temperament related to mother-reported anxiety symptoms with small to moderate magnitudes. Moderately sized correlations existed among maternal anxiety and mother-reported toddler anxiety problems, but not observed inhibited temperament. T2 solicited comforting behavior related to most maternal and child variables, and T3 solicited comforting behavior was most strongly related to observed temperament and mother-reported toddler anxiety symptoms.

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Time 1 maternal anxiety | .78*** | .82*** | .14 | .09 | .15 | .34*** | .34*** | .23† | .19† | .12 |

| 2. Time 2 maternal anxiety | -- | 80*** | .12 | −.00 | .11 | .31** | .35*** | .23* | .26** | .17 |

| 3. Time 3 maternal anxiety | -- | .27* | .15 | .13 | .36** | .38*** | .37*** | .42*** | .17† | |

| 4. Time 1 observed inhibited temperament | -- | .26* | .30* | .41*** | .35*** | .26* | .33** | .19 | ||

| 5. Time 2 observed inhibited temperament | -- | .34** | .29** | .18* | .11 | .29** | .23* | |||

| 6. Time 3 observed inhibited temperament | -- | .14 | .06 | .14 | .04 | .31** | ||||

| 7. Time 1 mother-reported toddler anxiety | -- | .53*** | .42** | .48*** | .39** | |||||

| 8. Time 2 mother-reported toddler anxiety | -- | .66*** | .27** | .31** | ||||||

| 9. Time 3 mother-reported toddler anxiety | -- | .33** | .33** | |||||||

| 10. Time 2 solicited comforting behavior | -- | .40*** | ||||||||

| 11. Time 3 solicited comforting behavior | -- |

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Transactional Models

Relations among maternal anxiety, toddler anxiety risk, and toddler-solicited comforting behavior within and across time were analyzed simultaneously in longitudinal path models in MPlus 7.3. In each of two models, we specified autoregressive and cross-lagged paths according to our conceptual model (Figure 1) to provide stringent tests of hypotheses. We tested paths from T1 maternal anxiety and T1 toddler anxiety risk to T2 toddler-elicited comforting behavior (H1). We tested paths from T2 toddler solicited comforting to T3 maternal anxiety and to T3 toddler anxiety risk (H2). We tested indirect effects within the standard normal distribution and by deriving bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CIs) (H3). We expected to test two indirect effects: from T1 maternal anxiety to T3 toddler anxiety risk through T2 toddler- elicited comforting behavior, and from T1 toddler anxiety risk to T3 maternal anxiety through T2 toddler elicited comforting behavior. We correlated error terms within timepoints to account for shared variance due to unstudied mechanisms (e.g., shared genetics). Correlated errors among constructs at T2 and T3 acknowledged that concurrent maternal anxiety and toddler anxiety risk may be proximal correlates of toddler-elicited comforting behavior, outside of variance predicted from T1.

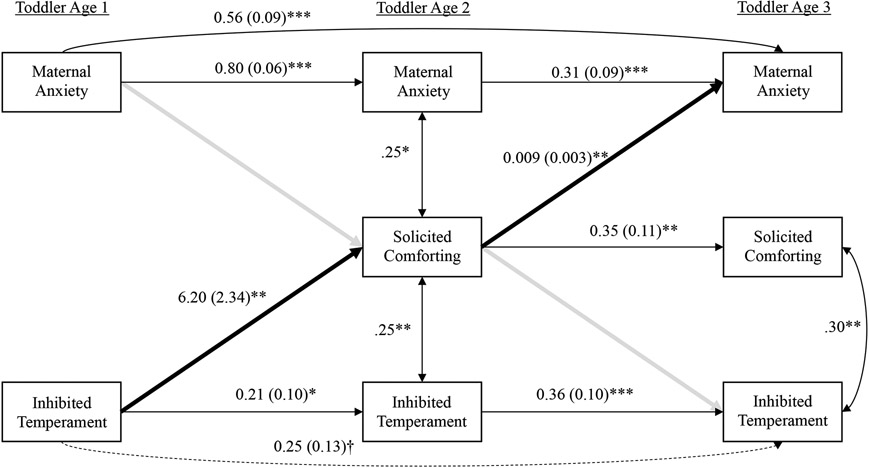

In the model with observed inhibited temperament (Table 4, Figure 2), hypothesis 1 was supported in that T1 inhibited temperament predicted T2 solicited comforting; T1 maternal anxiety did not. Hypothesis 2 was supported in that T2 solicited comforting predicted T3 maternal anxiety; it was not supported for the prediction of T3 inhibited temperament. These relations occurred above and beyond significant stability within constructs and concurrent relations at T2. We tested one indirect effect (H3), indicated by significant paths, from T1 inhibited temperament to T3 maternal anxiety through T2 solicited comforting. A significant indirect effect occurred in the standard normal distribution (ab = 0.06, SE = 0.03, Z = 1.99, p = .047, 95% CI [0.001, 0.113]) but was not supported with the bias-corrected bootstrapped 95% CI (−0.01, 0.17), the latter resulting from an inflated standard error (0.05).

Table 4.

Observed Inhibited Temperament: Path Model Coefficients

| Variable | b(SE) | β | t | P | 95% CI (b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV = T2 maternal anxiety (R2 = .66) | |||||

| T1 inhibited temperament | 0.02 (0.08) | 0.02 | 0.30 | .767 | [−0.14, 0.18] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 0.80 (0.06) | 0.81 | 14.14 | <001 | [0.69, 0.92] |

| DV = T2 inhibited temperament (R2 = .04) | |||||

| T1 inhibited temperament | 0.21 (0.10) | 0.20 | 2.14 | .032 | [0.02, 0.39] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | -0.01 (0.07) | −0.01 | −0.09 | .931 | [−0.14, 0.13] |

| DV = T2 solicited comforting behavior (R2 = .09) | |||||

| T1 inhibited temperament | 6.20 (2.34) | 0.27 | 2.65 | .008 | [1.62, 10.79] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 1.89(1.59) | 0.11 | −0.97 | .236 | [−1.23, 5.01] |

| DV = T3 maternal anxiety (R2 =.81) | |||||

| Maternal age at birth of child | −0.02 (0.01) | −0.10 | −1.96 | .050 | [−0.03, 0.00] |

| T1 inhibited temperament | 0.02 (0.08) | 0.02 | 0.28 | .111 | [−0.13, 0.17] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 0.56 (0.09) | 0.57 | 6.13 | <001 | [0.38, 0.74] |

| T2 inhibited temperament | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.00 | 0.01 | .994 | [−0.13, 0.13] |

| T2 maternal anxiety | 0.31 (0.09) | 0.31 | 3.62 | <001 | [0.14, 0.48] |

| T2 comforting behavior | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.16 | 2.99 | .003 | [0.003, 0.015] |

| DV = T3 inhibited temperament (R2 = .19) | |||||

| T1 inhibited temperament | 0.25 (0.13) | 0.23 | 1.91 | .056 | [−0.01, 0.50] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 0.02 (0.16) | 0.03 | 0.13 | .897 | [−0.29, 0.33] |

| T2 inhibited temperament | 0.36(0.10) | 0.34 | 3.63 | <001 | [0.17, 0.56] |

| T2 maternal anxiety | 0.06 (0.15) | 0.08 | 0.42 | .673 | [−0.24, 0.36] |

| T2 comforting behavior | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.13 | −1.30 | .194 | [−0.02, 0.003] |

| DV = T3 solicited comforting behavior (R2 = .15) | |||||

| T1 inhibited temperament | 0.03 (3.15) | 0.00 | 0.01 | .992 | [−6.13, 6.20] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 1.27 (3.98) | 0.07 | 0.25 | .749 | [−6.52, 9.07] |

| T2 inhibited temperament | 2.79 (2.32) | 0.11 | 1.20 | .230 | [−1.77, 7.35] |

| T2 maternal anxiety | −0.12 (3.67) | −0.01 | −0.03 | .974 | [−7.32, 7.08] |

| T2 comforting behavior | 0.35 (0.11) | 0.33 | 3.33 | .001 | [0.14, 0.56] |

Note. The model showed good fit according to chi-square test (χ2[5] = 5.14, p = .399), RMSEA (0.01, 90% CI [0.00, 0.11], CFI(1.00), TLI(1.00), and SRMR(0.02). The correlation was not significant between T1 inhibited temperament and T1 maternal anxiety (r =.12, p = .203). Also modeled were residual correlations between T2 inhibited temperament and T2 maternal anxiety (r = −.03, p = .756), T2 solicited comforting and T2 inhibited temperament (r = .25, p = .002) and T2 maternal anxiety (r = .25, p = .010), T3 inhibited temperament and T3 maternal anxiety (r = .02, p = .891) and T3 solicited comforting with those of T3 inhibited temperament (r = .30, p = .002) and T3 maternal anxiety (r = −.09, p = .450).

Figure 2. Path Model for Observed Inhibited Temperament.

Note. Statistically significant paths are solid (hypothesized paths are bolded), and marginally significant paths are dashed. Non-significant paths are not displayed except for gray hypothesized paths. Maternal age was modeled, but is not displayed, as a covariate predicting maternal anxiety at toddler age 3.†P < .10,*p < .05, **p< .01, ***p < .001

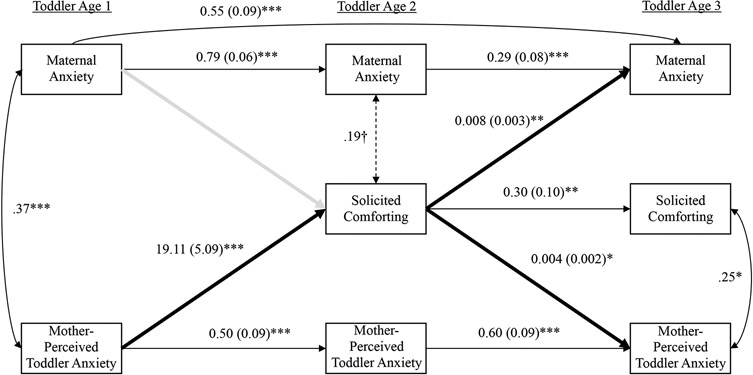

In the model with mother-perceived toddler anxiety (Table 5, Figure 3), hypothesis 1 was partly supported: T1 mother-perceived toddler anxiety predicted T2 solicited comforting; T1 maternal anxiety did not. Hypothesis 2 was supported: T2 solicited comforting predicted T3 maternal anxiety and T3 mother-perceived toddler anxiety. For H3, we tested the one indirect effect indicated by significant paths: T1 mother-perceived toddler anxiety to T3 maternal anxiety through T2 solicited comforting. The indirect effect was significant within the standard normal distribution (ab = 0.15, SE = 0.07, Z = 2.11, p = .035) and demonstrated a trend from the bias-corrected bootstrapping method (90% CI [0.004, 0.41]).

Table 5.

Mother-Perceived Toddler Anxiety: Path Model Coefficients

| Variable | b (SE) | β | t | P | 95% CI (b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV = T2 maternal anxiety (R2 = .67) | |||||

| T1 toddler anxiety | 0.18 (0.20) | 0.06 | 0.89 | .372 | [−0.21, 0.57] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 0.79 (0.06) | 0.79 | 12.83 | <001 | [0.67, 0.91] |

| DV = T2 toddler anxiety (R2 = .32) | |||||

| T1 toddler anxiety | 0.50 (0.09) | 0.49 | 5.36 | <001 | [0.32, 0.68] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.15 | 1.65 | .100 | [−0.01, 0.12] |

| DV = T2 solicited comforting behavior (R2 = .17) | |||||

| T1 toddler anxiety | 19.11 (5.09) | 0.40 | 3.76 | .000 | [9.14, 29.08] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 0.49 (1.67) | 0.03 | 0.30 | .768 | [−2.78, 3.77] |

| DV = T3 maternal anxiety (R2 = .82) | |||||

| Maternal age at birth of child | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.09 | −1.87 | .062 | [−0.03, 0.00] |

| T1 toddler anxiety | 0.08 (0.18) | 0.03 | 0.45 | .653 | [−0.27, 0.43] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 0.55 (0.09) | 0.55 | 6.15 | <001 | [0.37, 0.72] |

| T2 toddler anxiety | 0.27 (0.16) | 0.10 | 1.64 | .100 | [−0.05, 0.59] |

| T2 maternal anxiety | 0.29 (0.08) | 0.29 | 3.48 | <001 | [0.13, 0.46] |

| T2 comforting behavior | 0.008 (0.003) | 0.13 | 2.61 | .009 | [0.002, 0.013] |

| DV = T3 toddler anxiety (R2 = .51) | |||||

| T1 toddler anxiety | −0.04 (0.12) | −0.04 | −0.38 | .703 | [−0.27, 0.18] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.07 | 0.41 | .679 | [−0.09, 0.14] |

| T2 toddler anxiety | 0.60 (0.09) | 0.61 | 6.60 | <001 | [0.42, 0.78] |

| T2 maternal anxiety | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.04 | 0.27 | .784 | [−0.09, 0.12] |

| T2 comforting behavior | 0.004 (0.002) | 0.21 | 2.36 | .018 | [0.001, 0.008] |

| DV = T3 solicited comforting behavior (R2 = .20) | |||||

| T1 toddler anxiety | 9.03 (7.12) | 0.18 | 1.27 | .205 | [−4.92, 22.98] |

| T1 maternal anxiety | 0.69 (3.77) | 0.04 | 0.18 | .855 | [−6.71, 8.09] |

| T2 toddler anxiety | 7.01 (5.75) | 0.14 | 1.22 | .223 | [−8.15, 23.82] |

| T2 maternal anxiety | −1.04 (3.49) | −0.06 | −0.30 | .766 | [−4.27, 18.29] |

| T2 comforting behavior | 0.30 (0.10) | 0.28 | 2.96 | .003 | [0.10, 0.49] |

Note. The model showed good fit according to chi-square test (χ2[5] = 4.45, p = .487), RMSEA (0.00, 90% CI [0.00, 0.10], CFI (1.00), TLI (1.00), and SRMR (0.02). The correlation was significant between T1 toddler anxiety and T1 maternal anxiety (r = 37, p < .001). Also modeled were residual correlations betweenT2 toddler anxiety and T2 maternal anxiety (r = .15, p = .170, T2 solicited comforting with both T2 toddler anxiety (r = .04, p = .712) and T2 maternal anxiety (r = .19, p = .077), T3 toddler anxiety and T3 maternal anxiety (r = .17, p = .154) and T3 solicited comforting with those of T3 toddler anxiety (r = .25, p = .032) and T3 maternal anxiety (r = −.15, p = .187).

Figure 3. Path Model for Mother-Perceived Toddler Anxiety.

Note. Statistically significant paths are solid (hypothesized paths are bolded), and marginally significant paths are dashed. Non-significant paths are not displayed except for the gray hypothesized path. Maternal age was modeled, but is not displayed, as covariate predicting maternal anxiety at toddler age 3.†P < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Discussion

We tested transactional relations between maternal anxiety and toddler anxiety risk, indicated by both observed inhibited temperament and maternal perceptions, across toddlerhood and examined maternal comforting behavior, solicited by toddlers, as a possible behavioral mechanism of bidirectional effects. By simultaneously testing lagged paths between parents and children, over and above stability, we were able to rigorously test for directionality of relations between mothers and their toddlers.

Our results most strongly supported hypothesized child-directed effects on mothers. Consistent with theory that anxiety-prone children display greater reassurance-seeking and bids for support from their parents (Dadds & Roth, 2001), we hypothesized, and found, that toddler anxiety risk predicted maternal comforting behavior enacted in response to toddlers’ solicitations. This predictive relation was robust across method of assessing toddler anxiety risk. Toddler-solicited comforting behavior then predicted change in maternal anxiety, consistent with one part of our second hypothesis, which is notable given the large stability effects for maternal anxiety. Anxiety may be a particularly salient piece of mothers’ own development in the first three years postpartum (Mughal et al., 2018). Toddlers place heavy demands on mothers as they begin to develop in their communication, emotion regulation, and motor skills. Anxiety-prone children’s distress and reluctance to engage with the environment theoretically increases demand on mothers to respond, which can increase mothers’ own feelings of uncertainty, parenting stress, and incompetency, which fuel anxiety (Dadds & Roth, 2001). For this reason, we hypothesized a child-directed indirect effect, from toddler anxiety risk to maternal anxiety through toddler-solicited comforting behavior. We found evidence for a small indirect effect, using either observed inhibited temperament or mother-perceived toddler anxiety, in the standard normal distribution. These effects, although the same estimates, had larger standard errors resulting from resampling for the bias-corrected bootstrapping method, perhaps due to missing data inherent to our modified accelerated longitudinal design. We may have had limited statistical power to elucidate small effects. Small effects are expected in longitudinal mediation designs that rigorously control for stability in constructs and may not have the same interpretations as effects not controlling for stability (Adachi & Willoughby, 2015). Thus, we believe these effects are meaningful. Specifically, clinical interventions for anxious mothers should specifically address the role of child anxiety-proneness on the mother-child relationship and subsequent anxiety.

Aspects of our hypotheses focusing on mother-directed effects on toddlers were less strongly, or not at all, supported. When modeling observed inhibited temperament, more solicited comforting behavior occurred from mothers who were concurrently more anxious, but, contrary to our first hypothesis, earlier maternal anxiety did not predict solicited comforting behavior. Maternal anxiety also did not directly predict change in toddler anxiety risk. Maternal anxiety’s role in parenting and child anxiety may be proximal, rather than distal, a speculation that is supported by concurrent studies (e.g., Kerns et al., 2017) but requires additional longitudinal studies for falsification. Alternatively, other maternal characteristics, or toddler anxiety risk itself, may moderate the relation between maternal anxiety and later parenting, in line with studies showing no direct relation between maternal anxiety and parenting (e.g., Coplan et al., 2008). This could also be due to methodological differences between our study and others. We used a composite of three self-report measures of maternal anxiety rather than a single survey or a diagnostic interview, and our detailed observational measure of inhibited temperament differed from other measures of anxiety.

Further, theories highlighting anxious parenting as a key environmental influence on children’s anxiety development (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Dadds & Roth, 2001) informed our hypothesis that solicited comforting behavior, enacted during mild challenge and uncertainty, would predict later toddler anxiety risk. This hypothesis was supported for maternal perceptions of, but not observed temperamental risk for, toddler anxiety. Because maternal anxiety related to maternal perceptions of toddler anxiety, this could reflect another outcome of parenting on maternal anxiety. Alternatively, solicited comforting may predict increases in toddlers’ anxious behaviors that are accurately observed by mothers outside of the laboratory. Potentially, more robust parent-driven effects on children do not appear until later childhood, the focus of many studies on mothers’ anxious parenting (Kerns et al., 2011; Poole et al., 2018). Alternatively, parent-driven effects may have been overestimated in studies that did not control for stability in children’s anxiety or child-driven effects on parents. Also, our examination of a very specific and contextually bound parenting behavior diverges from studies assessing more global parenting behaviors like warmth and control.

Our study had several limitations. Most mothers and children were European American; anxiety and parenting can be perceived and exhibited differently, and have different consequences, across families of diverse identities (Asmal & Stein, 2008). Therefore, the current results are primarily generalizable to European American families. Advancement towards anti-racist psychological science requires greater representation of diverse families in research. We purposefully recruited families from the community to detect individual differences emerging from typical development, but studies of clinically anxious mothers that expand measurement beyond self-report may yield stronger parent-driven effects on children. We expected that toddler-solicited maternal comforting would become relevant when toddlers became more mobile and independent at age 2. However, our choice not to measure this behavior at the initial assessment limited the possible tests of alternative pathways, particularly for mother-driven effects. It should also be acknowledged that the associations tested in the current study occur alongside and in conjunction with multiple mechanisms, including additional aspects of parenting and socialization (particularly by fathers and other family members), co-regulation, psychophysiological and psychobiological processes, and genetics.

Conclusion

Children play an active role in shaping their environments, demonstrated presently within a transactional model of anxiety as the prediction from toddler anxiety risk to both toddler-solicited maternal comforting behavior and maternal anxiety. Although mothers’ influence on toddler anxiety may be elucidated by continued investigation of factors that reveal how and when maternal anxiety influences children’s outcomes, future work should routinely account for stability in toddler characteristics and child-elicited effects on parents.

Acknowledgements

The project from which these data were derived was supported by funds from Miami University and an R15 area award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R15 HD076158) of the National Institutes of Health, granted to Elizabeth Kiel. Elizabeth Kiel’s time was additionally supported by R01 MH113669 from the National Institute of Mental Health during the writing of this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We express our appreciation to Dr. Anne E. Kalomiris, staff of the Behavior, Emotions, and Relationships lab, and the families who participated in this project.

Data Availability Statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- Abramowitz JS, & Blakey SM (2020). Overestimation of threat. In Abramowitz JS & Blakey SM (Eds.), Clinical handbook of fear and anxiety: Maintenance processes and treatment mechanisms, (pp. 7–25). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/10.1037/0000150-001 [Google Scholar]

- Adachi P, & Willoughby T (2015). Interpreting effect sizes when controlling for stability effects in longitudinal autoregressive models: Implications for psychological science. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 72(1), 116–128. 10.1080/17405629.2Q14.963549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allmann AE, Kopala-Sibley DC, & Klein DN (2016). Preschoolers’ psychopathology and temperament predict mothers’ later mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(3), 421–432. 10.1007/sl0802-015-0Q58-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmal L, & Stein DJ (2008). Anxiety and culture. In Antony MM & Stein MB (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 657–664). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M, Touchette É, Garon-Carrier G, Dionne G, Côté SM, Vitaro F, … & Boivin M (2016). Distinct trajectories of separation anxiety in the preschool years: Persistence at school entry and early-life associated factors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(1), 39–46. 10.llll/icpp.12424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer JK, Morgan A, Prendergast LA, Beatson R, Gilbertson T, Bretherton L, … & Rapee RM (2019). Predicting temperamentally inhibited young children’s clinical-level anxiety and internalizing problems from parenting and parent wellbeing: A population study.Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(1), 1165–1181. 10.1007/sl0802-018-0442-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar E, Alcaine O, Zuellig AR, & Borkovec TD (2003). Screening for generalized anxiety disorder using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire: A receiver operating characteristic analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 34, 25–43. 10.1016/S0005-7916(03)00004-l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogels S, & Phares V (2008). Fathers’ role in the etiology, prevention, and treatment of child anxiety: A review and new model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 539–558. 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Bosson-Heenan J, Guyer AE & Horwitz SM (2006). Are infant-toddler social-emotional and behavioral problems transient? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(7), 849–858. 10.1097/01.chi.0000220849.4865Q.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Turovsky J, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Brown TA, & Barlow DH (1997). Validation of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale across the anxiety disorders. Psychological Assessment, 9(1), 21–27. 10.1037/1040-35909.1.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buss KA (2011). Which fearful toddlers should we worry about? Context, fear regulation, and anxiety risk. Developmental Psychology, 47, 804–819. 10.1037/a0023227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Fox NA, & Marshall TR (1996). Behavioral and physiological antecedents of inhibited and uninhibited behavior. Child Development, 67(2), 523–540. 10.1111/i.1467-8624.1996.tb01749.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, & Little TD (2003). The infant-toddler social and emotional assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(5), 495–514. 10.1023/A:1025449031360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita B, & Barlow D (1998). The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 3–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, … & Fox NA (2009). Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(9), 928–935. 10.1097/CHT0b013e3181ae09df [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooklin AR, Giallo R, D'Esposito F, Crawford S, & Nicholson JM (2013). Postpartum maternal separation anxiety, overprotective parenting, and children’s social-emotional wellbeing: Longitudinal evidence from an Australian cohort. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 618–628. 10.1037/a0Q33332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Arbeau KA, & Armer M (2008). Don’t fret, be supportive! Maternal characteristics linking child shyness to psychosocial and school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 359–371. 10.1007/slQ802-007-9183-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadds MR, & Roth JH (2001). Family processes in the development of anxiety problems.In Vasey MW & Dadds MR (Eds.), The developmental psychopathology of anxiety (pp. 278–303). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Vente W, Majdandzic M, & Bogels SM (2020). Intergenerational transmission of anxiety: Linking parental anxiety to infant autonomic hyperarousal and fearful temperament. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(11), 1203–1212. 10.1111/jcpp.13208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, & Ghera MM (2005).Behavioral inhibition: Linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 235–262. 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, & Schmidt LA (2001). Continuity and discontinuity of behavioral inhibition and exuberance: Psychophysiological and behavioral influences across the first four years of life. Child Development, 72(1), 1–21. 10.1111/1467-8624.00262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Rubin KH, Calkins SD, Marshall TR, Coplan RJ, Porges SW, … & Stewart S (1995). Frontal activation asymmetry and social competence at four years of age. Child Development, 66(6), 1770–1784. 10.1111/i.1467-8624.1995.tb00964.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde LC, Eilertsen EM, Eley TC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Roysamb E, & Ystrom E (2020). Maternal perinatal and concurrent anxiety and mental health problems in early childhood: A sibling comparison study. Child Development, 91, 456–470. 10.1111/cdev.13192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouze KR, Hopkins J, Bryant FB, & Lavigne JV (2017). Parenting and anxiety: Bidirectional relations in young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45(6), 1169–1180. 10.1007/s10802-016-0223-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges RF, Graham SA, Fearon P, Tough S, & Madigan S (2020). The chronicity and timing of prenatal and antenatal maternal depression and anxiety on child outcomes at age 5. Depression and Anxiety, 37, 576–586. 10.1002/da.23039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JD, Lebowitz ER, Marin CE, & Stark KD (2015). Family accommodation mediates the association between anxiety symptoms in mothers and children. Journal of Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 27(1), 41–51. 10.2989/17280583.2015.1007866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, & Garcia-Coll C (1984). Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Development, 55, 2212–2225. 10.2307/1129793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns CE, Pincus DB, McLaughlin KA, & Comer JS (2017). Maternal emotion regulation during child distress, child anxiety accommodation, and links between maternal and child anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 50, 52–59. 10.1016/i.ianxdis.2017.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerns K, Siener S, & Brumariu LE (2011). Mother-child relationships, family context, and child characteristics as predictors of anxiety symptoms in middle childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 593–604. 10.1017/S0954579411000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2010). Maternal accuracy and behavior in anticipating children…s responses to novelty: Relations to fearful temperament and implications for anxiety development. Social Development, 19(2), 304–325. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00538.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Buss KA (2012). Associations among context-specific maternal protective behavior, toddlers’ fearful temperament, and maternal accuracy and goals. Social Development, 21, 742–760. 10.1111/j1467-9507201100645.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, & Maack DJ (2012). Maternal BIS sensitivity, overprotective parenting, and children’s internalizing behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences, 53, 257–262. 10.1016/i.paid.2012.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiel EJ, Price NN, & Premo JE (2020). Maternal comforting behavior, toddlers’ dysregulated fear, and toddlers’ emotion regulatory behaviors. Emotion, 20(5), 793–803. 10.1037/emo000060Q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein MR, Lengua LJ, Thompson SF, Moran L, Ruberry EJ, Kiff C, & Zalewski M (2018). Bidirectional relations between temperament and parenting predicting preschool-age children’s adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(S1), S113–S126. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1169537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence PJ, Creswell C, Cooper PJ, & Murray L (2020). The role of maternal anxiety disorder subtype, parenting and infant stable temperamental inhibition in child anxiety: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61, 779–788. 10.1111/jcpp.13187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, & Rhemtulla M (2013). Planned missing data designs for developmental researchers. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 199–204. 10.1111/cdep.12043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, & Lovibond SH (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behavior Research and Therapy, 55(3), 335–343. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangold (2017): INTERACT User Guide. Mangold International GmbH; (Ed.) www.mangold-international.Com [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, & Clarke JC (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(4), 455–470. 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, & Borkovec TD (1990). Development and validation of the penn state worry questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(6), 487–495. 10.1016/0005-7967(97)10031-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz M, Majdandžić M, & Bogels S (2018). Concurrent and predictive associations between infants’ and toddlers’ fearful temperament, coparenting, and parental anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(4), 569–580. 10.1080/15374416.2015.1121823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mount KS, Crockenberg SC, Jó PSB, & Wagar JL (2010). Maternal and child correlates of anxiety in 2½-year-old children. Infant Behavior and Development, 55(4), 567–578. 10.1016/i.infbeh.2010.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mughal MK, Giallo R, Arnold P, Benzies K, Kehler H, Bright K, & Kingston D (2018). Trajectories of maternal stress and anxiety from pregnancy to three years and child development at 3 years of age: Findings from the All Our Families (AOF) pregnancy cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 234, 318–326. 10.1016/i.iad.2018.02.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddi KB, Murdock KW, Vadnais S, Bridgett D, & Gartstein MA (2013). Maternal and infant temperament characteristics as contributors to parenting stress in the first year postpartum. Infant and Child Development, 22, 553–579. 10.1002/icd.l813 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Edgar KE, & Guyer AE (2014). Behavioral inhibition: Temperament or prodrome? Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 7(3), 182–190. 10.1007/s40473-014-0019-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole K, Van Lieshout RJ, McHolm AE, Cunningham CE, & Schmidt LA (2018). Trajectories of social anxiety in children: Influence of child cortisol reactivity and parental social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 1309–1319. 10.1007/slQ802-017-0385-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Coplan RJ, & Bowker JC (2009). Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 141–171. 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Nelson LJ, Hastings P, & Asendorpf J (1999). The transaction between parents’ perceptions of their children’s shyness and their parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22(4), 937–957. 10.1080/0165Q2599383612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff A (2009). The transactional model. In Sameroff A (Ed.), The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each other (p. 3–21). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 10.1037/11877-001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.