Abstract

Culture-dependent studies have implicated sulfur-oxidizing bacteria as the causative agents of acid mine drainage and concrete corrosion in sewers. Thiobacillus species are considered the major representatives of the acid-producing bacteria in these environments. Small-subunit rRNA genes from all of the Thiobacillus and Acidiphilium species catalogued by the Ribosomal Database Project were identified and used to design oligonucleotide DNA probes. Two oligonucleotide probes were synthesized to complement variable regions of 16S rRNA in the following acidophilic bacteria: Thiobacillus ferrooxidans and T. thiooxidans (probe Thio820) and members of the genus Acidiphilium (probe Acdp821). Using 32P radiolabels, probe specificity was characterized by hybridization dissociation temperature (Td) with membrane-immobilized RNA extracted from a suite of 21 strains representing three groups of bacteria. Fluorochrome-conjugated probes were evaluated for use with fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) at the experimentally determined Tds. FISH was used to identify and enumerate bacteria in laboratory reactors and environmental samples. Probing of laboratory reactors inoculated with a mixed culture of acidophilic bacteria validated the ability of the oligonucleotide probes to track specific cell numbers with time. Additionally, probing of sediments from an active acid mine drainage site in Colorado demonstrated the ability to identify numbers of active bacteria in natural environments that contain high concentrations of metals, associated precipitates, and other mineral debris.

Acidophilic bacteria play an important role in environmental and industrial processes. Chemolithotrophic and heterotrophic bacteria benefit bioleaching applications by solubilizing metals from sulfide minerals (12, 14, 38). Conversely, the production of ferric iron and sulfuric acid by certain acidophilic bacteria may cause significant environmental damage by inducing acidic mine drainage and the corrosion of concrete (11, 26, 28, 33).

Members of the genus Thiobacillus, particularly Thiobacillus ferrooxidans, have often been cultured and detected by PCR in acidified mining wastes and are therefore commonly used as models to describe how the metabolism of iron- and sulfur-oxidizing bacteria can catalyze acid production in the environment. Other acidophilic bacteria have also been associated with acidic mining, bioleaching, and sewer crown environments, including Leptospirillum ferrooxidans and members of the genus Acidiphilium (14, 21, 38). While some investigators have agreed that Thiobacillus is a dominant genus in acid mine drainage environments (13, 15), recent genetic studies have suggested that Thiobacillus species play a different and perhaps lesser role than previously thought in maintaining acidic environments (33).

In the microbial ecology associated with acidic environments, members of the genus Acidiphilium may have significant interactions with sulfur- and iron-oxidizing bacteria. A mutualistic relationship between Thiobacillus species and members of the genus Acidiphilium has been suggested (21). Pure-culture studies on T. thiooxidans have shown that these microorganisms excrete pyruvic and oxalacetic acids that are self-inhibitory at 2 × 10−5 to 7 × 10−5 M (7), and therefore, growth of T. thiooxidans may require a relationship with an acidophilic heterotroph. Members of the genus Acidiphilium are capable of iron reduction. This biological reduction of Fe(III) to Fe(II) helps to offset ferric iron production and thus attenuates acid production in mine drainage environments (31).

The apparent environmental importance of these two genera necessitates the development of a method to identify and quantify active Thiobacillus and Acidiphilium species in situ. Culture-based techniques (15, 21) have been useful in identifying relationships between Thiobacillus species and environmental pH; however, given the many limitations and biases introduced by quantitative culture-based techniques (3), these relationships should be considered tentative. Molecular techniques have proven useful in more accurately describing the microbial ecology of acidic environments. Signature fatty acid analysis (22) has identified neutrophilic and acidophilic Thiobacillus species in corroding concrete sewers. PCR (14, 38) and 16S rRNA gene sequence analyses of bacteria have been used to identify members of the genera Thiobacillus, Leptospirillum, and Acidiphilium and other chemolithoautotrophic bacteria in bioleaching applications, sites of pyrite oxidation (10), and natural systems containing high sulfide concentrations (4). However, PCR is not yet reliably quantitative and relative abundance cannot be determined by this method alone. Bacterial community investigations that characterized the spacer regions between the 16S and 23S genes in the bacterial rRNA genetic loci after PCR amplification revealed the presence of T. ferrooxidans, T. thiooxidans, and L. ferrooxidans in copper leachates (12, 30, 37); the investigators reported that bacterial populations comprised of T. thiooxidans and L. ferrooxidans but not T. ferrooxidans may develop during leaching at high sulfuric acid concentrations. Monoclonal antibodies against T. ferrooxidans (6) have been developed and can be used quantitatively, but they are difficult to use for a broader population description as they are limited to a single serotype. 16S rRNA probe fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) cell counts for T. ferrooxidans and L. ferrooxidans nested with eubacterial FISH cell counts suggest the presence of other species in acidic environments and provided an important step toward quantitative population analysis in these environments (10, 33). These studies concluded that T. ferrooxidans occurs mainly in peripheral slime-based communities (pH >1.2) and not at the site of substrate acid formation (pH 0.3 to 0.7). This previously reported Thiobacillus probe (33) is specific for the species T. ferrooxidans only. The presence of T. thiooxidans and Acidiphilium species in acidic environments, as determined by PCR and DNA analysis, coupled with results from population description studies of T. ferrooxidans and L. ferrooxidans, suggests a need to examine different species that promote sulfide weathering (33).

We report here the development and testing of two synthetic oligonucleotide probes, one circumscribing T. thiooxidans and T. ferrooxidans and the other circumscribing the members of the genus Acidiphilium. Quantitative FISH analysis was used to characterize bacteria associated with acid mining wastes in laboratory analogue systems and environmental samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms, culture techniques, and nucleic acid extraction.

The organisms used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cultures were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, Va.), the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (Braunschweig, Germany), and collections at the University of Colorado at Boulder. All organisms were cultured in accordance with ATCC and German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures recommendations. Pure liquid cultures were harvested in mid-log phase, and organisms were pelleted by centrifugation of 50 ml for 8 min at 10,000 × g. RNA was extracted using an RNAqueous Isolation Kit (Ambion Inc., Austin, Tex.) with the following modifications to the manufacturer's cell lysing instructions. Cells were lysed in 1.7-ml centrifuge tubes containing 200 μl of cell culture, 400 μl of lysing agent, and 400 μl of 1-μm-diameter washed, sterile glass beads. The mixture was shaken for 3 min with a Mini-beadbeater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.). RNA was quantified spectrophotometrically at 260 nm (standardized by an A260 of 1 = 40 μg of RNA per ml). Isolated RNA was denatured by the addition of 3 volumes of 2% glutaraldehyde (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and diluted to 4 μg/ml with 1 μg of polyadenylic acid (Sigma Chemical Co.) by the methods of Raskin and coworkers (32).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in membrane hybridization consisting of species of gram-positive bacteria; alpha, beta, and gamma Proteobacteria; and the Flexibacter-Cytopaga-Bacteroides group

| Organism | Phylogenetic grouping (subdivision) |

|---|---|

| 1. Flavobacterium columnare RR-1A ATCC 43622 | Flexibacter-Cytophaga-Bacteroides I |

| 2. Acetobacter diazotrophicus ATCC 49037 | Proteobacteria (α) |

| 3. Acidiphilium cryptum ATCC 33463 | Proteobacteria (α) |

| 4. Acidiphilium organovorum ATCC 43141 | Proteobacteria (α) |

| 5. Acidiphilium acidophilum ATCC 27807 | Proteobacteria (α) |

| 6. Sphingomonas chlorophenolicus ATCC 39723 | Proteobacteria (α) |

| 7. Nitrosomonas europaea | Proteobacteria (β) |

| 8. Thiobacillus thioparus ATCC 23646 | Proteobacteria (β) |

| 9. Thiobacillus thiooxidans ATCC 8085 | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 10. Thiobacillus thiooxidans 3/TA ATCC 19377 | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 11. Thiobacillus thiooxidans ATCC 19703 | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 12. Thiobacillus thiooxidans DSM 612 | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 13. Thiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 14. Thiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 19859 | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 15. Pseudomonas fluorescens | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 16. Pseudomonas chlororaphis ATCC 17810 | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 17. Acinetobacter calcoaceticus | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 18. Thiobacillus neapolitanus ATCC 23461 | Proteobacteria (γ) |

| 19. Bacillus subtilis | Gram-positive Bacillus-Lactobacillus-Streptococcus |

| 20. Micrococcus luteus | High-G+C gram-positive bacteria |

| 21. Gordona amarae ASF-3 | High-G+C gram-positive bacteria |

Environmental samples.

Samples of subsurface leachate and sediment were taken from saturated tailing piles at the Rockford Tunnel Wetland, Idaho Springs, Colo. The ores discarded as tailing piles in this region were comprised primarily of pyrite (FeS2), with small amounts of chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), tennantite (Cu12As4S13), and gold (Au) (35). Subsurface tailing (and leachate) samples, taken at depths between 10 and 20 cm below the surface, were aseptically transferred to sterile 50-ml Oakridge centrifuge tubes using an ethanol-washed spatula. To prepare sediment-associated bacteria for FISH, samples were immediately transferred to a fresh 4% paraformaldehyde-based fixative solution in a 1:3 volumetric dilution. Within 4 h, samples were transported to the laboratory and washed three times in a 50 mM phosphate-buffered saline solution (150 mM NaCl, pH 7.2) using sequential centrifugation and resuspension (5 min at 10,000 × g) for FISH analysis. pH was measured by a calomel reference element pH probe.

Laboratory bench-scale reactors.

In addition, laboratory-scale batch bioreactors were used to monitor pure and mixed cultures of selected acidophilic bacteria using the oligonucleotide probes described below. The reactors were 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks mounted to a shaker table (New Brunswick Scientific Company, Inc., Edison, N.J.) agitated at 200 rpm. All batch bioreactors contained 9K minimal medium (5) with the following modifications: 2.43 g of NH4Cl per liter, 0.5 g of KH2PO4 per liter, 0.41 g of MgCl2 · 6H2O per liter, 0.1 g of KCl per liter, and 0.018 g of Ca(NO3)2 per liter; the pH was adjusted to 2.5 with 2 N HCl. A 1.5-g sample of dry pyrite was added to the bioreactors (see below) to serve as the growth substrate for autotrophic cells. The initial liquid volume of each reactor was 250 ml, with 2.5 ml being removed for each sample. Sterility was ensured by autoclaving the reactors and liquid solutions at 121°C at 15 lb/in2 for 15 min, covering the opening with cotton plugs, and sampling the reactors aseptically. Using accepted methods, bioreactors were confirmed to maintain dissolved O2 concentrations in excess of 6 mg/liter during the experimental periods.

Batch bioreactors were inoculated with pure cultures of T. ferrooxidans (ATCC 23270) and Acidiphilium acidophilum (ATCC 27807; formerly Thiobacillus acidophilus (18). T. ferrooxidans cells were added by first growing them in a separate reactor on solid-phase pyrite (Ward Scientific, Rochester, N.Y.). The pyrite was prepared by grinding and sieving to a particle diameter between 425 and 832 μm, washed in 0.1 N HCl, and rinsed with Milli-Q water (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) until the background conductivity of the rinse water was less than 3 μS. Suspended T. ferrooxidans cells were also added to the reactors to ensure that both planktonic and sessile T. ferrooxidans cells were present. To sustain heterotrophic growth during the course of the experiment (ca. 60 days), glucose was added at a concentration of 1,000 mg/liter whenever necessary. Bulk soluble-phase total (ferric and ferrous) iron was monitored by the phenanthroline method after the sample had been passed through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter and then chemically reduced in 1% hydroxylamine (9).

Oligonucleotide probes.

Two oligonucleotide probes were synthesized. S-G-Acdp-0821-a-A-24 (Acdp821) was designed to circumscribe all catalogued members of the genus Acidiphilium, and S-S-Thio-0820-a-A-22 (Thio820) was designed to circumscribe all of the T. thiooxidans and T. ferrooxidans strains catalogued by the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) (25), except the more distantly related mixotrophic strain T. ferrooxidans m-1 DSM 2392. Both probes were designed by comparing all of the 16S rRNA sequences for Acidiphilium and Thiobacillus species catalogued by the RDP using the SUBALIGN program. The RDP CHECK_PROBE program and the BLAST network service (1) were used to determine the uniqueness of the probe sequences. Additionally, a probe complementary to the small-subunit rRNAs of all of the organisms, S-*-Univ-1390-a-A-18 (Univ1390) (27), was used for membrane hybridizations. Probes circumscribing the domain Bacteria (S-D-Eub-0338-a-A-18) (Eub338) (2) and the species Leptospirillum ferrooxidans (LF581) (33) were also used in whole-cell hybridizations. Probes used in membrane hybridization studies were synthesized and purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography by Genosys Biotech (Woodlands, Tex.). The 5′ end was labeled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase (34). Oligonucleotides used in FISH analysis were obtained from Genosys Biotech and purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography or cartridge, depending on the recommendation of the fluorescent-dye manufacturer. FISH analysis probes were 5′ end labeled with tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (Univ1390), CY3 (Eub338), Oregon green 538 (Acdp820 and LF581), or Texas red (Thio821).

FISH.

Target cells from environmental samples, batch bioreactors, and pure cultures were observed with an epifluorescence microscope using the following procedures. Cells were fixed on ice in 1:3 (vol/vol) dilutions of 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h. The fixative was removed by sequential centrifugation and resuspension; cells were washed three times in 0.1% Tergitol type NP-40 (Sigma Chemical Co.) and resuspended in sterile filtered phosphate-buffered saline. Probe target species were observed using a modification for membrane filter enumeration (16). Hybridization and incubation were performed with 1.7-ml microcentrifuge tubes. Ten microliters of fixed cell solution was added to prewarmed hybridization buffer (0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.9 M NaCl, 100 mM Tris [pH 7.2]) containing 200 ng of fluorochrome-conjugated probe. Cells were allowed to hybridize for 9 h below the predetermined disassociation temperature (Td). A 50-μl volume of this solution was then removed, added to 450 μl of fresh hybridization buffer (prewarmed to the Td), and incubated for 1 h at the Td. Cells were then counterstained with a 10-μg/ml final concentration of 4′,6-damidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma Chemical Co.) and filtered with 0.22-μm-pore-size black polycarbonate filters (Osmonics Inc., Livermore, Calif.). The filters were washed with hybridization solution at the Td to remove any unbound probe. Filters were mounted on microscope slides for observation with low-fluorescence immersion oil. Bacteria retained on slide and membrane filter surfaces were observed using a Nikon Eclipse E400 series epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Excitation and emission filter sets were chosen in accordance with the fluorescent-dye manufacturers' recommendations. FISH counts were performed in accordance with a previously described protocol (19) on a total of three filters per sample, and a minimum of 10 fields were counted per slide. A coefficient of variance of less than 30% was chosen as the criterion for an acceptable uniform distribution of FISH-stained bacteria on filters. Images were captured by a 24-bit cooled color digital camera (Spot Camera; Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, Mich.).

Td determination and stringency testing.

Organisms with zero, two, and unknown mismatches according to probe design results were used in temperature disassociation experiments. Extracted RNA (50 ng) was dot blotted onto nylon membranes (Magna Charge; Micron Separation, Inc., Westboro, Mass.) as previously described (32). 32P-labeled nucleic acid probes were hybridized to membrane-bound RNA at 40°C for the Acdp821 probe and 25°C for the Thio820 probe for 16 h. Following hybridization, individual RNA blots were cut from the membranes and 32P-labeled probes were eluted at increasing temperatures in 15 ml of 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate–1× SSC (0.15 M NaCl, 0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7.0) during sequential washes. The wash sequence temperature increased in 5°C increments to 80°C. Membrane blots were transferred to new vials containing fresh wash solution at 15-min intervals for each temperature tested. During each interval, the blot-containing wash vial contents were gently mixed by placement of the dry bath incubator block (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) on a rotary shaker at 50 rpm. The amount of 32P-labeled probe released during each wash was quantified by adding equal amounts of scintillation cocktail to the wash vials (ScintiSafe Plus, Fair Lawn, N.J.) and counting 32P disintegrations associated with eluted probe on a model 1600CA liquid scintillation analyzer (Packard Instruments, Downers Grove, Ill.). Data were fitted to a sigmoidal curve using SigmaPlot software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.), and the empirical Td values were determined at the temperature where 50% of the probe was eluted.

Specificity of Acdp820 and Thio821 was tested using a suite of 21 organisms representing the alpha, beta, and gamma subdivisions of the division Proteobacteria, the gram-positive bacteria, and the Cytophaga-Bacteroides-Flexibacter group (Table 1). Extracted RNA (50 ng) from each species was blotted in triplicate onto three separate membranes. Each membrane was isolated and hybridized with either Acdp820, Thio821, or Univ1338. Membranes were dried, and then blots were excised and individually washed for 10-min intervals at the experimentally determined Td. The remaining probe was eluted from the membrane blots by washing for a final incubation interval at 90°C. The amount of probe released in the final 90°C wash was quantified by scintillation counting as described above.

Whole-cell experiments.

Probe specificity was also tested using FISH techniques. A fixed pure culture of the mid-log growth target species Acidiphilium organovorum (50 μl) was mixed with cultures (50 μl of each) of the fixed nontarget species Sphingomonas chlorophenolicus ATCC 39723, T. thiooxidans DSM 612, and Pseudomonas fluorescens. The same amount of A. organovorum was added to 150 μl of sterile deionized water, and both treatments were hybridized with probe Acdp821 as described above. Similar experiments were performed with the target species T. thiooxidans DSM 612 and probe Thio820. Three microscope slides were prepared for each treatment, and cells were counted as described above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Probe Acdp821 design.

Probes Acdp821 and Thio820, designed to circumscribe members of the genus Acidiphilium and the species T. ferrooxidans and T. thiooxidans, respectively, were tested against a list of known rRNA sequences in the RDP using the CHECK_PROBE program (25) and the BLAST network service (1). Acdp821 circumscribed all of the sequenced Acidiphilium species with no mismatches and aligned with A. acidophilum with one target site sequence deletion. Six closely related species had two mismatches (no species showed one mismatch) near the 3′ end of the target sequence. To demonstrate specificity and determine whether these mismatches would result in a significant decrease in the Td associated with Acdp821, Acetobacter diazotrophicus, a bacterium with two target sequence mismatches, was included in temperature disassociation experiments.

Probe Thio820 design.

Probe Thio820 had no mismatches with the T. ferrooxidans and T. thiooxidans sequences catalogued in the major databases. However, sequence ambiguities (unknown bases) exist in the strains T. thiooxidans ATCC 19377 and T. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270. Additionally, six species, members of the genera Chlorobium, Coprococcus, and Lachnospira, have two mismatches with probe Thio820. Because these species are obligate anaerobes (Thiobacillus species are obligate aerobes) (8, 20, 23, 29), their role in highly acidic, aerobic environments was not considered and they were not included in temperature disassociation experiments. The more distantly related mixotrophic strain T. ferrooxidans m-1 DSM 2392 was not circumscribed by Thio820.

The genus Thiobacillus is heterogeneous, with members exhibiting a wide range of physiological and genetic characteristics (15, 18, 24). Members of this genus can be found in three different subdivisions of the phylum Proteobacteria (25), with T. acidophilus recently being transferred to the genus Acidiphilium as A. acidophilum (18); thus, a single probe circumscribing the entire genus could not be designed. Our probe design therefore focused on the closely phylogenetically and physiologically related thiobacilli that have been identified in acidic environmental niches (14, 26, 33, 37, 38). Probe Thio820 should facilitate identification of both T. thiooxidans and T. ferrooxidans when nested with the previously developed (33) T. ferrooxidans probe. Neutrophilic Thiobacillus species (e.g., T. neapolitanus and T. thioparus) have been identified as important indicators of the progression of corrosion in concrete corrosion environments (21), and probes that circumscribe these thiobacilli may be important for this application. These species each have eight mismatches with probe Thio820, and this probe did not hybridize with RNAs extracted from T. neapolitanus and T. thioparus in this study.

Specificity and Td experiments.

To compare hybridization responses among target and nontarget organisms, probes Acdp821 and Thio820 were hybridized against a suite of microorganisms with known RNA sequences (Table 1). These organisms included members of three subdivisions of the Proteobacteria of which Acidiphilium species (alpha) and Thiobacillus species (beta and gamma) are members, as well as the Flexibacter-Cytophaga-Bacteroides group and the gram-positive bacteria. Results are summarized in Fig. 1 as counts per minute normalized to nanograms of RNA blotted. All of the microorganisms tested hybridized with the universal probe (Univ1138), and only selected target species hybridized with probes Acdp821 and Thio820 (Table 2). The average nontarget signal intensity was less than 2% of the signal intensity recovered from the respective probe target species in all cases except for A. diazotrophicus. Nontarget signal intensity associated with A. diazotrophicus was observed at 11% of the target signal intensity due to its two mismatches with the target. This observation was predicted by the Td curves. Signal variability was estimated from triplicate measurements (three independent experiments with one nucleic acid stock) for each species, and the standard deviations were calculated (Table 2).

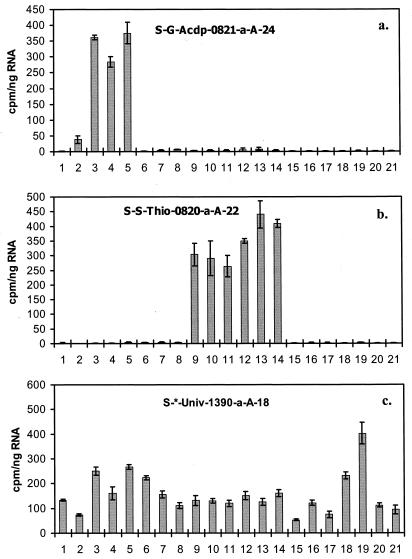

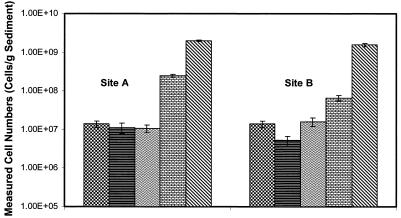

FIG. 1.

Probes Acdp821 (a), Thio820 (b), and Univ1390 (c) were hybridized on membranes containing RNAs from 21 different strains of bacteria belonging to three different groups. The numbers at the bottom of each graph correspond to the strains listed in Table 1. Membranes were first washed at previously determined Tds corresponding to the probes used and then washed at 90°C to elute the remaining probe. The quantity of the probe eluted was determined and normalized to the amount of RNA blotted. Each error bar represents one standard deviation (for three blots).

TABLE 2.

Experimental disassociation and stringency results for S-S-Thio-0820-a-A-22 and S-G-Acdp-0821-a-A-24

| Probea and target group | No. of mismatches | Experimental Td (°C) ± SD | Avg nontarget signal intensity as % of target intensity (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-S-Thio-0820-a-A-22 | |||

| T. thiooxidans ATCC 19377 | 0 | 46.0 ± 0.17 | |

| T. thiooxidans DSM 612 | 0 | 46.5 ± 0.42 | |

| T. thiooxidans ATCC 19703 | Unknown | 45.9 ± 0.53 | |

| T. thiooxidans ATCC 8085 | Unknown | 43.9 ± 0.47 | |

| T. ferrooxidans ATCC 19859 | 0 | 46.8 ± 0.12 | |

| T. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 | 0 | 45.6 ± 0.12 | |

| All target species | 45.8 ± 0.59 | 0.71 (0.25–1.31) | |

| S-G-Acdp-0821-a-A-24 | |||

| A. angustum ATCC 35903 | 0 | 58.6 ± 0.12 | |

| A. cryptum ATCC 33463 | 0 | 59.0 ± 0.35 | |

| A. organovorum ATCC 43141 | 0 | 60.7 ± 0.17 | |

| A. acidophilum ATCC 27807 | 0 | 62.2 ± 0.42 | 1.47 (0.30–11.12) |

| Genus Acidiphilium | 0 | 60.1 ± 1.65 | |

| A. diazotrophicus ATCC 49037 | 2 | 52.1 ± 0.06 |

Small-subunit rRNA positions (Escherichia coli numbering) are shown.

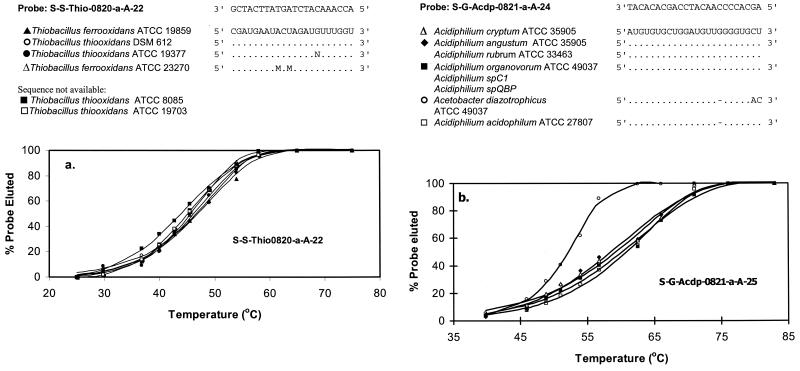

Results of disassociation temperature experiments are presented in Fig. 2. For the Acidiphilium species tested against probe Acdp821, the average Td was 62.2 ± 0.42°C. A. diazotrophicus, a species with two sequence mismatches, had a markedly lower Td of 52.1 ± 0.06°C. The Td for the Thio820 probe targets was 45.8 ± 0.59°C. When applied to the Thio820 Td experiments, Tukey's test (36) results showed that the observed Td differences between species with target sequence ambiguities, T. thiooxidans ATCC 19377 and T. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270, and species with fully determined target sequences (e.g., T. thiooxidans DSM 612) fell between the differences in their means with 95% confidence. These results suggest total homology among their target sequences. Tds and observed errors associated with the unsequenced strain T. thiooxidans ATCC 19703 fell within the same confidence region, also implying homology in target sequences and a correct classification. However, the mean Td associated with T. thiooxidans ATCC 8085 fell outside the confidence regions determined by Tukey's test, suggesting at least one mismatch with the target sequence.

FIG. 2.

Temperature disassociation experiments for S-S-Thio-0820-a-A-22 (a) and S-G-Acdp-0821-a-A-24 (b). Symbols represent the measured data, and lines represent the model fit for Td determination. The probe and target sequences are shown above the graphs. Identical bases are represented by dots, differences are denoted by the replacement nucleotides shown below the target sequences, and dashes indicate deletions. N is A, C, G, or T; M is A or C.

Whole-cell stringency.

Known quantities of target cells were added to mixed cultures of nontarget microorganisms and compared to probe counts from the same amount of pure-culture target cells added to sterile distilled water. Results of a paired t test showed that, with 95% confidence, there was no statistically significant difference between the mixed-culture and pure-culture counts. The result was the same for probes Thio820 and Acdp821. Coefficients of variance for all counts were less than 25%. Probe specificity in the FISH application was sufficient to distinguish between Acidiphilium species and Thiobacillus species, as well as species from the alpha and gamma subclasses of the phylum Proteobacteria.

Implementation of probes in laboratory reactors.

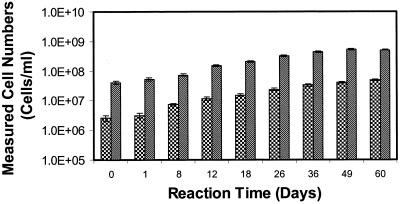

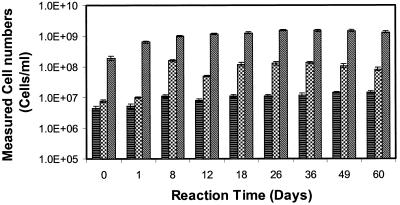

Results of the pure-culture laboratory experiments indicated that oligonucleotide probes Thio820 and Acdp821 were capable of tracking changes in T. ferrooxidans and A. acidophilum bulk fluid cell concentrations, respectively, in a well-controlled experimental system containing solid-phase pyrite. Sampling of pyrite and its associated cells was not performed in laboratory reactors to avoid destructive sampling of the reactors. The experiment was carried out for 60 days, during which time changes in the chemical and biological characteristics of the bulk liquid phase were monitored. The measured variations in cell numbers of T. ferrooxidans and a mixed culture of T. ferrooxidans and A. acidophilum are shown in Fig. 3 and 4, respectively. During the course of the experiment, both reactors exhibited an increase in Fe(III) and a concomitant decrease in pH, typical of an active T. ferrooxidans culture. Glucose amendments were consumed rapidly (ca. 5 to 7 days) in the mixed-culture reactor and had to be repeated to maintain active growth of A. acidophilum. Between 0.7 and 2.3% of the DAPI-stained cells hybridized with probe Thio820, and between 1.6 and 16.3% of the DAPI-stained cells had a positive response to probe Acdp820. In the T. ferrooxidans pure-culture reactor, cells detected by probe Thio820 accounted for 6.0 to 10.3% of the total cells as determined by staining with DAPI. The low percentages of probe-detected cells in the pure- and mixed-culture reactors reflect the low activity of planktonic bulk fluid cells. The lower activity and overall increase with time of T. ferrooxidans in the mixed-culture reactor suggest that the presence of acidophilic heterotrophs inhibits autotrophic activity. The lower oxidation rates of pyrite determined by dissolved ferric and ferrous iron analysis in the mixed-culture reactor support this finding (unpublished data).

FIG. 3.

Bulk fluid measured cell concentrations versus time for a pure-culture T. ferrooxidans reactor. Bars:  , probe Thio820;

, probe Thio820;  , DAPI-stained cells. Each error bar represents 1 standard deviation (for three slides).

, DAPI-stained cells. Each error bar represents 1 standard deviation (for three slides).

FIG. 4.

Bulk fluid measured cell concentrations versus time for a mixed-culture T. ferrooxidans and A. acidophilum reactor. Bars:  , probe Thio820;

, probe Thio820;  , probe Acdp821;

, probe Acdp821;  , DAPI-stained cells. Each error bar represents 1 standard deviation (for three slides).

, DAPI-stained cells. Each error bar represents 1 standard deviation (for three slides).

Implementation of probes with environmental samples.

Environmental samples collected from the Rockford Tunnel tailing pile were subject to DAPI staining and whole-cell hybridization with oligonucleotide probes Thio820, Acdp821, LF581, and Eub338. Results of whole-cell hybridizations are presented in Fig. 5 for two locations. Site A (pH 3.0) corresponds to the base of a tailing pile, and site B (pH 3.1) corresponds to the inlet of a wetland directly below a tailing pile. These sites were characterized by elevated dissolved and total metal concentrations (17) from both sediments and water and could be considered typical acid mine drainage sites. At both sites, Thiobacillus species accounted for about 1.4 × 107 cells/g of sediment while Acidiphilium species varied from 1.1 × 107 to 1.4 × 107 cells/g of sediment at sites A and B, respectively. The ability to microscopically discriminate and count FISH-hybridized species in an environmental matrix containing high concentrations of metal precipitates is demonstrated for site A in Fig. 6. Total probe Eub338 counts were higher than the sum of the directed-probe counts in both cases. At site B, 53% of the probe Eub338 counts were accounted for by the sum of Thiobacillus and Acidiphilium species and L. ferrooxidans while only 15% of the probe Eub338-positive signal at site A could be accounted for by the probes used. Schrenk and coworkers (33) reported that at an acidic mine drainage site, T. ferrooxidans and L. ferrooxidans occur in slime layers with pHs above 1.3, but only L. ferrooxidans occurs in subsurface acid-forming environments (pHs 0.3 to 0.7). The probe Thio820 and L. ferrooxidans values in this study were consistent with these trends above pH 1.3; however, because Thio820 circumscribes both T. thiooxidans and T. ferrooxidans, comparisons to results in the literature cannot be accurately made. The nesting of Thio820 with a previously described T. ferrooxidans probe may provide valuable insight into the relative abundance of T. thiooxidans at sites of acid generation pHs above and below 1.3. These data also raise the possibility that the oligonucleotide probes used as described herein do not completely describe all of the bacterial species that are significant to the acid drainage ecosystem and related impacts on the drainage environment. Additionally, these sediment probing results indicate active acidophilic populations near the site of acid production (tailing piles), as well as downstream from these tailings.

FIG. 5.

FISH sediment samples from an active acid mine drainage site in Colorado. The bars represent the numbers of cells per gram of sediment circumscribed by probe Thio820 ( ), probe Acdp821 (

), probe Acdp821 ( ), probe LF581 (

), probe LF581 ( ), probe Eub338 (

), probe Eub338 ( ), and DAPI staining (

), and DAPI staining ( ). Site A sediment is from the outlet of a tailing pile, and site B sediment is from the inlet to a wetland directly below the tailing pile. Each error bar represents 1 standard deviation (for three slides).

). Site A sediment is from the outlet of a tailing pile, and site B sediment is from the inlet to a wetland directly below the tailing pile. Each error bar represents 1 standard deviation (for three slides).

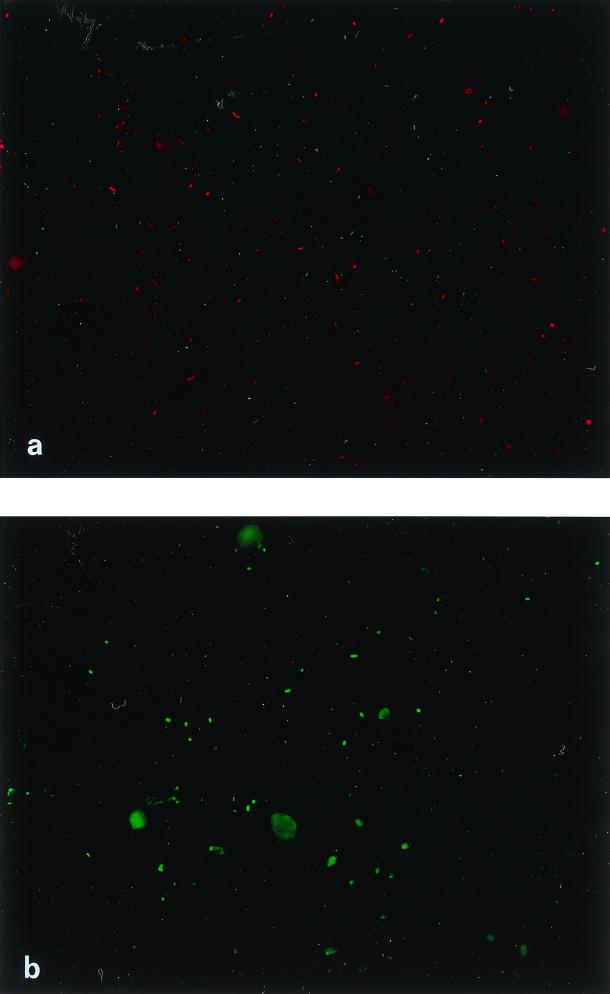

FIG. 6.

Epifluorescence micrographs of 16S rRNA in situ hybridization for 5′ Texas red-labeled probe Thio820 (specific for T. thiooxidans and T. ferrooxidans) (a) and 5′ Oregon green 538-labeled probe Acdp821 (specific for the genus Acidiphilium) (b). Environmental samples are from sediment at the base of a mining tailing pile (site A). Images were captured by a Spot 24-bit digital camera and produced with Adobe Photoshop 5.0 for Windows.

Summary.

The design and testing of oligonucleotide probes for T. ferrooxidans, T. thiooxidans, and the genus Acidiphilium are significant steps toward quantitative descriptions of acidic-environment microbial ecology. Hybridization conditions and stringency for Thio820 and Acdp821 have been determined. Active bulk fluid populations were tracked in laboratory bioreactors, while active bacteria were quantified in natural environments that contain high concentrations of metals and associated precipitates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was sponsored by the Cyprus Amax Mining Company and a GAANN Doctoral Fellowship.

We thank Robert Kuchta for the use of his scintillation counter, Lutgarde Raskin for her valuable assistance in temperature dissociation experiments, and two peer reviewers for their helpful comments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Krumholz L, Stahl D A. Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental studies in microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:762–770. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.762-770.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angert E R, Northup D E, Reysenbach A L, Peek A S, Goebel B M, Pace N R. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of bacterial community in Sulphur River, Parker Cave, Kentucky. Am Mineralogist. 1998;83:1583–1592. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atlas R M. Phenanthroline method. In: Parks L C, editor. Handbook of microbiological media. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker K H, Mills A L. Determination of the number of respiring Thiobacillus ferrooxidans cells in water samples by using combined fluorescent antibody–2-(p-iodophenyl)-3-(p-nitrophenyl)-5-phenyltetretrazolium chloride staining. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:338–344. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.2.338-344.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borichewski R M. Keto acids as growth-limiting factors in autotrophic bacteria that share their habitat. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1967;38:265–292. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bryant M P. Genus Lachnospira. In: Kreig N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergy's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 661–662. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eaton A D, Clesceri L S, Greenberg A E, editors. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1995. pp. 3-68–3.70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards K J, Goebel B M, Rodgers T M, Schrenk M O, Gihring T M, Cardona M M, Hu B, McGuire M M, Hamers R J, Pace N R, Banfield J F. Geomicrobiology of pyrite (FeS2) dissolution: case study at Iron Mountain, California. Geomicrobiol J. 1999;16:155–179. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards M, Courtney B, Heppler P, Hernandez M. Beneficial discharge of iron coagulation sludges to sewers. J Environ Eng. 1997;123:1027–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espejo R T, Romero J. Bacterial communities in copper sulfide ores inoculated and leached with solution from a commercial-scale copper leaching plant. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1344–1348. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1344-1348.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evangelou V P, Zhang Y L. Pyrite oxidation mechanisms and acid mine drainage prevention. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 1995;25:141–199. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goebel B M, Stackebrandt E. Cultural and phylogenetic analysis of mixed microbial populations found in natural and commercial bioleaching environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1614–1621. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.5.1614-1621.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison A P., Jr The acidophilic thiobacilli and other acidophilic bacteria that share their habitat. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:265–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.001405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heidelberg J F, O'Neill K R, Jacobs D, Colwell R R. Enumeration of Vibrio vulnificans on membrane filters with a fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probe specific for kingdom-level 16S rRNA sequences. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3474–3476. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3474-3476.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez K S. Metals speciation and distribution in a montane wetland receiving acid mine drainage. M.S. thesis. Boulder, Colo: Department of Geology, University of Colorado; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiraishi K, Nagashima V P, Masuura K, Shimada K, Takaichi S, Wakao N, Katayama Y. Phylogeny and photosynthetic features of Thiobacillus acidophilus and related acidophilic bacteria: its transfer to the genus Acidiphilium as Acidiphilium acidophilum comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:1389–1398. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-4-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobbie J E, Daley R J, Jasper S. Use of Nuclepore filters for counting bacteria by fluorescence microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;58:1225–1228. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.5.1225-1228.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holdeman Moore L V, Moore W E G. Genus Coprococcus. In: Sneath P H A, Mair N S, Sharpe M E, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 2. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 1097–1099. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Islander R L, Devinny J S, Mansfeld F, Postyn A, Shih H. Microbial ecology of crown corrosion in sewers. J Environ Eng. 1991;117:751–770. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerger B D, Nichols P D, Sand W, Bock E, White D C. Association of acid-producing thiobacilli with degradation of concrete: analysis by ‘signature’ fatty acids from polar lipids and lipopolysaccharide. J Ind Microbiol. 1987;2:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuenen J G, Robertson L A, Tuovinen O H. The genera Thiobacillus, Thiomicrospira, and Thiosphaera. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H, editors. The prokaryotes: a handbook on the biology of bacteria: ecophysiology, isolation, identification, and applications. New York, N.Y: Springer Verlag; 1992. p. 2625. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lane D J, Harrison A P, Jr, Stahl D, Pace B, Giovannoni S J, Olsen G J, Pace N R. Evolutionary relationships among sulfur- and iron-oxidizing eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:269–278. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.269-278.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maidak B L, Cole J R, Parker C T, Jr, Garrity G M, Larsen N, Li B, Lilburn T G, McCaughey M J, Olsen G J, Overbeek R, Pramanik S, Schmidt T M, Tiedje J M, Woese C R. A new version of the RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:171–173. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morton R L, Yanko W A, Graham D W, Arnold R G. Relationships between metal concentrations and crown corrosion in Los Angeles County sewers. J Water Pollut Control Fed. 1991;63:789–798. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen G J, Lane D J, Giovannoni S J, Pace N R, Stahl D A. Microbial ecology and evolution: a ribosomal RNA approach. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1986;40:337–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parker C D. Mechanics of corrosion of concrete sewers by hydrogen sulfide. Sewage Ind Wastes. 1951;23:1477–1485. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfennig N. Genus Chlorobium. In: Stanley J T, Bryant M P, Pfennig N, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 3. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 1684–1687. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pizarro J, Jedlicki E, Orellana O, Romero J, Espejo R T. Bacterial populations in samples of bioleached copper ore as revealed by analysis of DNA obtained before and after cultivation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1323–1328. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1323-1328.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pronk J T, Johnson D B. Oxidation and reduction of iron by acidophilic bacteria. Geomicrobiol J. 1992;10:153–171. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raskin L, Stromley J M, Rittmann B E, Stahl D A. Group-specific 16S rRNA hybridization probes to describe natural communities of methanogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:1232–1240. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.4.1232-1240.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schrenk M O, Edwards K J, Goodman R M, Hamers R J, Banfield J F. Distribution of Thiobacillus ferroxidans and Leptospirillum ferroodixans: implications for generation of acid mine drainage. Science. 1998;279:1519–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5356.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stahl D A, Amann R. Development and application of nucleic acid probes. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1991. pp. 205–248. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart K C, Sererson R C, editors. Guidebook on the geology, history, and surface-water contamination and remediation in the area from Denver to Idaho Springs, Colorado. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tukey J W. Comparing individual means in the analysis of variance. Biometrics. 1949;5:99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vásquez M, Espejo R T. Chemolithotrophic bacteria in copper ores leached at high sulfuric acid concentration. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:332–334. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.332-334.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wulf-Durand P, Bryant L J, Sly L I. PCR-mediated detection of acidophilic bioleaching-associated bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2944–2948. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2944-2948.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]