ABSTRACT

Novel neplanocin A derivatives have been identified as potent and selective inhibitors of hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication in vitro. These include (1S,2R,5R)-5-(5-bromo-4-methyl-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidin-7-yl)-3-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-3-ene-1,2-diol (AR-II-04-26) and (1S,2R,5R)-5-(4-amino-3-iodo-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-1-yl)-3-(hydroxylmethyl)cyclopent-3-ene-1,2-diol (MK-III-02-03). The 50% effective concentrations of AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 were 0.77 ± 0.23 and 0.83 ± 0.36 μM in HepG2.2.15.7 cells, respectively. These compounds reduced intracellular HBV RNA levels in HepG2.2.15.7 cells and infected primary human hepatocytes. Accordingly, they could reduce HBs and HBe antigen production in the culture supernatants, which was not observed with clinically approved anti-HBV nucleosides and nucleotides (reverse transcriptase inhibitors). The neplanocin A derivatives also inhibited HBV RNA derived from cccDNA. In addition, unlike neplanocin A itself, the compounds did not inhibit S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine hydrolase activity. Thus, it appears that the mechanism of action of AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 differs from that of the clinically approved anti-HBV agents. Although their exact mechanism (target molecule) remains to be elucidated, the novel neplanocin A derivatives are considered promising candidate drugs for inhibition of HBV replication.

KEYWORDS: hepatitis B virus, antiviral, neplanosin A derivative, unique mechanism

INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis B is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and is a serious health problem, with nearly 300 million chronically infected individuals worldwide (1). Chronic HBV infection is a major risk factor of liver diseases, such as liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Currently, pegylated interferons (PEG-IFNs) and nucleoside/nucleotide analogs (NAs) are approved for the treatment of chronic HBV infection. The NAs include lamivudine (3TC), adefovir (ADF), entecavir (ETV), tenofovir disoproxil (TDF), and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF). Although IFNs are considered to eliminate HBV in a certain proportion of patients, they are often poorly tolerated for patients, especially at high doses (2). The NAs act as potent inhibitors of HBV DNA polymerase, which also has the function of reverse transcription. Furthermore, HBV-infected patients are required for long-term therapy with NAs to prevent viral reactivation. Consequently, drug-resistant mutants may appear during treatment (3, 4). This is mainly due to the presence of highly stable and covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) of HBV in the nucleus of HBV-infected hepatocytes. The standard therapies with IFNs and NAs make it difficult to eliminate cccDNA from the HBV-infected hepatocytes (5). Therefore, the identification and development of potent and selective HBV inhibitors with a novel mechanism of action are desired for treatment of chronic HBV infection.

In fact, several attempts have been made to identify and develop novel anti-HBV agents. Myrcludex-B is a synthetic lipopeptide derived from the cell attachment region of HBV envelope protein (6, 7). Pretreatment of hepatocytes with this peptide can prevent viral entry into the cells. The oligonucleotide-based nucleic acid polymer REP 2139 is currently under clinical development for the treatment of chronic HBV infection. REP 2139 blocks HBsAg release from HBV-infected hepatocytes through interfering with the assembly and secretion of viral particles (8, 9). Phenylpropenamide derivatives suppressed HBV replication by accumulating genome-free capsids without affecting capsid morphology, and heteroaryldihydropyrimidines (HAPs) inhibited HBV replication through capsid disassembly (10–12). Although HAPs exhibited antiviral efficacy in an animal model of HBV infection without toxicity, the development of HAP derivatives was halted after a clinical trial due to their toxicity (11, 13, 14).

Neplanocin A (NPA) was isolated from Ampullariella regularis as an antitumor substance and is known as a potent inhibitor of S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine hydrolase (SAHase) (15, 16). SAHase is a key enzyme in the regulation of S-adenosyl-l-methionine-dependent methylation reactions during mRNA synthesis. Inhibition of SAHase raises intracellular SAH levels, blocking cellular methylation reactions via feedback inhibition mechanism. This causes reduced methylation of viral mRNA 5′ cap moieties and impairs viral protein synthesis (17). Thus, SAHase has been considered an attractive target for inhibition of viral replication. In fact, NPA and its derivatives have been identified as inhibitors of various DNA and RNA viruses, including vaccinia virus, herpes simplex viruses, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C virus, reovirus, and Ebola virus (18). It was previously reported that 7-deazaneplanocin A (7-DNPA) derivatives selectively inhibited the replication of wild-type HBV and 3TC-resistant mutants (19).

In this study, we have examined various NPA derivatives for their inhibitory effect on HBV replication in cell cultures and found that two novel 7-DNPA derivatives are potent and selective inhibitors of HBV. In addition, their mechanism of action has proved to be totally different from that of the existing anti-HBV nucleoside/nucleotide analogs.

RESULTS

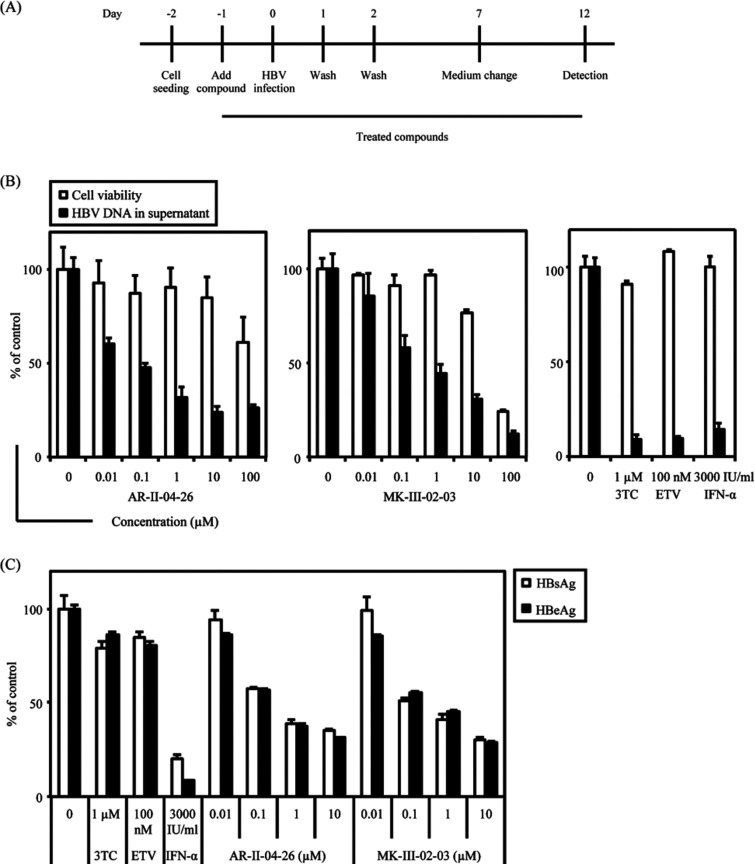

Inhibition of HBV DNA and HBsAg production in HepG2.2.15.7 cells.

The anti-HBV activity of (1S,2R,5R)-5-(5-bromo-4-methyl-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]-pyrimidin-7-yl)-3-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopent-3-ene-1,2-diol (AR-II-04-26) and (1S,2R,5R)-5-(4-amino-3-iodo-1H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-1-yl)-3-(hydroxylmethyl)cyclopent-3-ene-1,2-diol (MK-III-02-03) (Fig. 1A) was examined in HepG2.2.15.7 cells. 3TC was used as a reference compound. As shown in Fig. 1B, both compounds selectively reduced the amount of HBV DNA in the culture supernatants of HepG2.2.15.7 cells in a dose-dependent fashion. The 50% effective concentration (EC50) and 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of AR-II-04-26 were 0.77 ± 0.23 μM and >100 μM, respectively. On the other hand, the EC50 and CC50 of MK-III-02-03 were 0.83 ± 0.36 μM and 67.8 ± 7.7 μM, respectively. These results indicate that AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 are potent and selective inhibitors of HBV DNA production in cell cultures. Since NPA is a potent inhibitor of SAHase, we examined the effect of AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 on SAHase activity. These compounds did not inhibit SAHase activity, while the SAHase inhibitors NPA and 3-deazaneplanocin A (DZNep) had no inhibitory effect on HBV replication (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These results suggest that the anti-HBV activity of AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 is not due to the inhibition of SAHase activity.

FIG 1.

Inhibitory effect of NPA derivatives on HBV DNA and antigen production in HepG2.2.15.7 cells. (A) Chemical structures of AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03. (B) HepG2.2.15.7 cells were treated with AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03 at various concentrations or the reference compound 3TC for 9 days. Every 3 days, culture medium was replaced with fresh culture medium containing an appropriate concentration of the compound. The cell viability was measured by a tetrazolium dye method (open column). The culture supernatants were collected and treated with lysis buffer, and HBV DNA was quantified by real-time PCR (closed column). (C) HepG2.2.15.7 cells were treated with AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03 at various concentrations or 3TC for 9 days, as described for panel B. The culture supernatants were collected and their HBsAg (open column) and HBeAg (closed column) levels were measured by ELISA. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and representative results (means ± standard deviations [SD]) are shown.

AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 were also examined for their inhibitory effect on the production of HBs and HBc antigens (HBsAg and HBeAg, respectively) in HepG2.2.15.7 cells. Interestingly enough, the compounds reduced HBsAg and HBeAg production in a dose-dependent fashion but 3TC did not (Fig. 1C), indicating that their mechanism of action (target molecule) clearly differs from that of 3TC, one of the existing anti-HBV nucleoside/nucleotide analogs.

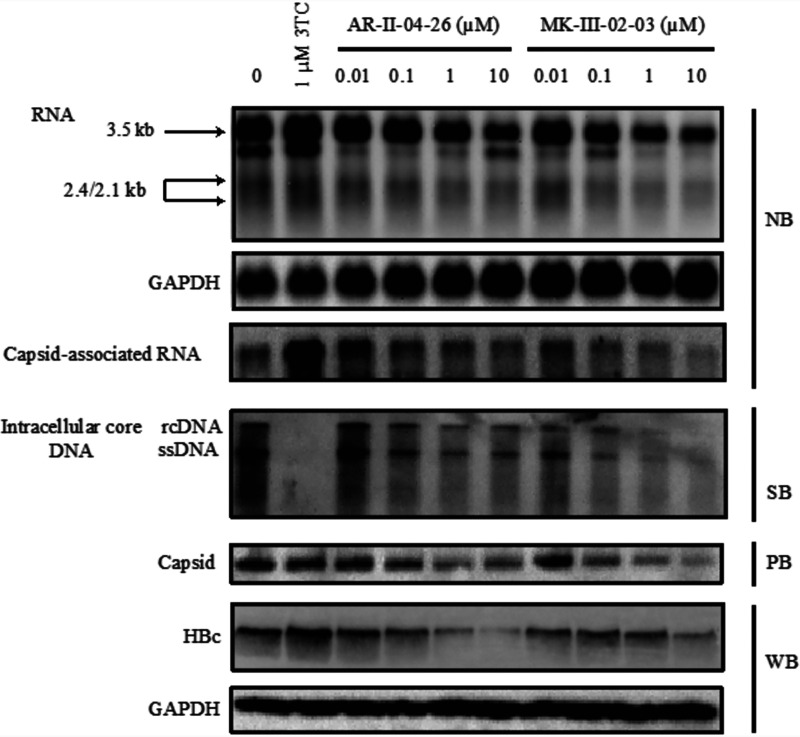

Inhibition of HBV RNA, capsid-associated HBV RNA, intracellular HBV core DNA, capsid formation, and HBc protein in HepG2.2.15.7 cells.

To gain insight into the mechanism of action, AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 were further investigated for their effect on different steps in HBV replication cycle. When the transcription of viral RNA was determined by Northern blotting, the compounds inhibited the synthesis of pregenome RNA (pgRNA) (3.5 kb) and surface mRNA (2.4 and 2.1 kb) in HepG2.2.15.7 cells (Fig. 2). Such inhibition was not observed with the reverse transcriptase inhibitor 3TC. Although the RNA inhibition by AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 was observed at a concentration of 0.1 μM, further increase of compound concentration did not lead to complete suppression of pgRNA and surface mRNA. These results corresponded well to those of HBsAg production in the culture supernatants. Unlike 3TC, the compounds could reduce capsid-associated RNA, HBc protein, and capsid formation in HepG2.2.15.7 cells. The amounts of intracellular core HBV DNA were also reduced by AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Inhibitory effect of NPA derivatives on HBV RNA, intracellular core HBV DNA, capsid, and HBc protein levels. HepG2.2.15.7 cells were treated with AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03 at various concentrations or the reference compound 3TC for 9 days. Every 3 days, the culture medium was replaced with fresh culture medium containing an appropriate concentration of the compound. Total RNA, capsid-associated HBV RNA, intracellular core DNA, capsid, and whole-cell proteins of the cells were extracted and analyzed by Northern blotting (NB) and Southern blotting (SB), particle blotting (PB), and Western blotting (WB), respectively.

Antiviral activity in HBV-infected PHHs derived from humanized chimeric mice.

AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 were also examined for their inhibitory effect on HBV replication in primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, the compounds selectively inhibited HBV DNA production in the culture supernatants of HBV-infected PHHs in a dose-dependent fashion. The EC50 and CC50 of AR-II-04-26 were 0.068 μM and >100 μM, respectively. The EC50 and CC50 of MK-III-02-03 were 0.38 μM and 32.4 μM, respectively. Both compounds could also reduce the HBsAg and HBeAg production in the infected PHHs (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, the compounds were more inhibitory to HBeAg production in the infected PHHs than in HepG2.2.15.7 cells. HBeAg originates from either cccDNA or integrated DNA in the infected PHHs, while it originates from integrated DNA rather than cccDNA in HepG2.2.15.7 cells (20). Therefore, we examined the effect of AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 on cccDNA in the infected PHHs. As shown in Fig. 4A, the compounds did not affect the HBV cccDNA in the infected PHHs. In contrast, total HBV RNA, HBV precore RNA (pcRNA), pgRNA, and intracellular core DNA were reduced by treatment with AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 (Fig. 4B and C). These results suggest that they inhibit HBV RNA expression from cccDNA. In addition, their stronger inhibitory effect in PHHs compared to HepG2.2.15.7 cells may be because the number of infected cells is increasing over time through a spread of the infection with de novo-synthesized virions.

FIG 3.

Inhibitory effect of NPA derivatives on HBV replication and antigen production in PHHs. (A) Experimental design for infection of PHHs with HBV. (B) PHHs were treated with AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03 at various concentrations or the reference compounds 3TC, ETV, and IFN-α for 12 days. On days 1, 2, and 7, the culture medium was replaced with fresh culture medium containing an appropriate concentration of the compound. The cell viability was measured by a tetrazolium dye method (open column). The culture supernatants were collected and treated with lysis buffer, and HBV DNA was quantified by real-time PCR (closed column). (C) PHHs were treated with AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03 at various concentrations or the reference compounds 3TC, ETV, and IFN-α for 12 days, as described above. The culture supernatants were collected, and their HBsAg (open column) and HBeAg (closed column) levels were measured by ELISA. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and representative results (means ± SD) are shown.

FIG 4.

Inhibitory effect of NPA derivatives on HBV cccDNA, HBV mRNAs, and intracellular core HBV DNA in PHHs. (A) PHHs were treated with AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03 at various concentrations or the reference compounds 3TC, ETV, and IFN-α for 12 days. On days 1, 2, and 7, the culture medium was replaced with fresh culture medium containing an appropriate concentration of the compound. Total DNA (500 ng) was treated with PSAD, and cccDNA was quantified by real-time PCR. (B) Total RNA was quantified by real-time RT-PCR. The primer pairs for detecting each mRNA were described in Materials and Methods. GAPDH level was determined as an internal control for normalization. (C) The intracellular core HBV DNA was extracted and analyzed by real-time PCR. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, and representative results (means ± SD) are shown.

Effect on HBV RNA derived from cccDNA.

The NPA derivatives decreased the HBV RNA, HBsAg, and HBeAg in HepG2.2.15.7 cells but not in Hep38.7-Tet cells (Fig. S2). Although the average number of copies of cccDNA in HepG2.2.15.7 cells, a HepG2.2.15 clone producing a higher number of viral particles, is unknown, it ranged from 0 to 10.8 copies/cell in HepG2.2.15 cells (21). HBV replication in Hep38.7-Tet cells is regulated by tetracycline, and it is considered that Hep38.7-Tet cells do not produce cccDNA in the presence of tetracycline. Therefore, we examined the effect of AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 on HBV RNA derived from cccDNA. First, removal of tetracycline from culture medium led to the accumulation of HBV RNA and cccDNA in Hep38.7-Tet cells. After incubation for 14 days, the culture medium was supplemented with 1 μg/mL tetracycline and 10 μM 3TC to immediately shut down transgene-based pgRNA transcription and viral DNA replication, respectively, which prevented the replenishment of cccDNA formation. After 4 days, although the levels of viral RNA slightly decreased, cccDNA remained at a high level. Therefore, the cells were treated with AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03 at this point, and the culture medium was changed every 2 days until day 24 (Fig. 5A). As expected, AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 inhibited the HBV RNA on days 20, 22, and 24 but did not reduce the accumulated cccDNA (Fig. 5B). In addition, the compounds suppressed the HBsAg production in a time-dependent fashion (Fig. 5C). These results indicate that the NPA derivatives inhibit HBV RNA expression from cccDNA.

FIG 5.

Inhibitory effect of NPA derivatives on HBV RNA production from cccDNA in Hep38.7-Tet cells. (A) Hep38.7-Tet cells were seeded in a collagen-coated 6-well plate. When the cells became confluent, tetracycline was removed from the culture medium to induce HBV replication and cccDNA. After incubation for 14 days, 1 μg/mL tetracycline and 10 μM 3TC were added to the culture medium to shut down pgRNA transcription from the integrated HBV genome and prevent viral DNA replication. After 4 days, the cells were treated with culture medium containing tetracycline, 3TC, and either 10 μM AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03 and further incubated. (B) Hep38.7-Tet cells were cultured in the absence (−) or presence (+) of tetracycline, 3TC, and/or the NPA derivative. At the indicated days, the level of cccDNA (Hirt DNA) and HBV RNA were determined by Southern blotting and Northern blotting, respectively. (C) The culture supernatants of Hep38.7-Tet cells were collected at the indicated days, and their HBsAg levels were determined by ELISA.

Effect on HBV promoter and enhancer.

Hep38.7-Tet cells were a clone of HepAD38 cells stably transfected with 1.1-U length HBV genome under the control of a tetracycline regulatory element and minimum cytomegalovirus promoter (tetCMV) in place of the viral core promoter in HepG2 cells (20, 22, 23). If AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 do not inhibit HBV replication in Hep38.7-Tet cells, the compounds possibly interact with the viral core promoter and inhibit the transcription of viral genome. When the compounds were examined for their inhibitory effect of HBV replication in Hep38.7-Tet cells, they did not reduce extra- and intracellular HBV DNA levels (Fig. S2A and B). HBsAg of Hep38.7-Tet cells is not regulated by tetracycline, so the NPA derivatives should affect HBsAg production in Hep38.7-Tet cells. However, our results indicated that the NPA derivatives did not. In contrast, the compounds suppressed HBsAg production in HepG2.2.15.7- and HBV-infected PHH cells. These results suggest that the genes or proteins regulating HBsAg expression are different between Hep38.7-Tet and other cells (Fig. S2C). In the next experiment, AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 were examined for whether they affect the HBV promoter and enhancer activity. When a transient HBV promoter activity assay was conducted in HepG2 or HepG2.2.15.7 cells, the compounds did not suppress the viral promoter and enhancer activity (Fig. S3). These results suggest that the NPA derivative affects the RNA degradation.

Effect on pgRNA degradation.

We next assessed the influence of AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 on viral RNA degradation. To this end, viral RNA expression was attenuated by actinomycin D, and viral RNA levels were determined by Northern blotting. HepG2.2.15.7 cells were treated with AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03 and actinomycin D at the indicated time, as shown in Fig. 6. Interestingly, AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 promoted the degradation of 3.5-kb pgRNA, and they promoted the degradation of surface mRNA to a lesser degree, suggesting that they affected mainly the degradation of viral RNA. Thus, the NPA derivatives inhibit HBV replication through accelerating the degradation of 3.5-kb pgRNA, yet their exact mechanism of action still remains to be further investigated. In addition to accelerating the degradation, the decrease of pgRNA may also be because pgRNA is packaged into the capsid, subjected to reverse transcription, and released as a virion or naked capsid.

FIG 6.

Effect of NPA derivatives on the decay of HBV pregenomic RNA in the HepG2.2.15.7 cells. HepG2.2.15.7 cells were seeded into a 24-well plate at 5.0 × 104 cells/well. After incubation for 3 days, the cells were treated with 10 μM AR-II-04-26 or 10 μM MK-III-02-03 and 10 μg/mL actinomycin D for 6, 12, and 24 h. Total RNA was extracted at the indicated time using TRIzol reagent and determined by Northern blotting.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified two NPA derivatives, AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03, to be potent and selective inhibitors of HBV replication in HepG2.2.15.7 cells and PHHs. Unlike the anti-HBV nucleoside/nucleotide analogs currently approved for clinical use, the NPA derivatives inhibited HBsAg production in these cells (Fig. 1 and 3). This may be advantageous over the existing anti-HBV drugs in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B, since large amounts of HBV antigens, particularly HBsAg, have been shown to exhaust antigen-specific T-cell immune responses in patients (24). Our results also suggest that the compounds inhibit HBV replication through suppressing the transcription of viral RNA from cccDNA and integrated HBV DNA (Fig. 2 and 4). Although the compounds inhibited HBV replication in a dose-dependent fashion, they could not completely suppress the synthesis of viral RNA even at high concentrations. Therefore, further modification of their chemical structures may be required and is in progress to identify the NPA derivatives that completely inhibit HBV RNA synthesis and HBsAg production.

It is known that SAHase inhibitors, such as NPA, DZNep, and aristeromycin, exert their antiviral activity through blocking the methylation reaction mediated by SAHase. In fact, NPA and its derivatives are inhibitory to the replication of minus-strand RNA, double-stranded RNA, and DNA viruses (18). Thus, NPA-type derivatives have also been developed as promising candidates for inhibition of HBV and other viruses (19, 25). However, our results demonstrated that NPA and DZNep were not active against HBV replication (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material), while AR-II-04-26 (7-deazaneplanocin A derivative) and MK-II-02-03 (7-deaza-8-azaneplanocin A derivative) were not inhibitory to SAHase activity (Fig. S1B). It was previously reported that 7-deazaneplanocin A derivatives did not affect SAHase activity (26). The pharmacophore analysis revealed that the N-7 position played an important role in its inhibitory effect on SAHase, which supports our finding that AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 did not interfere with SAHase activity. Even so, further studies may be required to conclude that the anti-HBV activity of this series is indeed unrelated to the inhibition of SAHase activity, since only two compounds have been examined so far.

Another important issue to be determined is whether the nucleoside structure is required for the inhibition of HBV replication. In other words, AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 need to be phosphorylated whether or not they exert their anti-HBV activity. At present, we do not have any evidence that the compounds can be phosphorylated in HepG2.2.15.7 cells and PHHs. In addition, it is not known whether the hydroxy group at the 5′-position is indispensable for exerting anti-HBV activity of the NPA derivatives. Several derivatives, of which the hydroxyl group at the 5′ position is replaced by another group, will be synthesized and examined for their anti-HBV activity.

Recently, the Roche group reported that RG7834, belonging to a dihydroquinolizinone (DHQ) chemical class, was a potent and orally bioavailable small-molecule inhibitor of HBV gene expression. RG7834 reduced viral RNA through accelerating RNA degradation without affecting HBV promoter activity (27). It interacts with noncanonical poly(A) RNA polymerases (PAP) and inhibits the function of PAP-associated domain-containing proteins 5 and 7 (PAPD5 and PAPD7), which play an important role in maintaining HBV RNA stabilization. Another group also reported that RG7834 affected the posttranscriptional regulatory element (HRPE) of HBV (28). However, the activity of RG7834 was lost in the presence of actinomycin D or cycloheximide. They speculated that new RNA transcription and protein synthesis was required for the antiviral function of RG7834 (28). In contrast, AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 accelerated the degradation of viral RNA in the presence of actinomycin D (Fig. 5). Therefore, it is possible that their mechanism of action differs from that of RG7834.

In conclusion, the NPA derivatives AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 are novel inhibitors of HBV replication with a unique antiviral mechanism of action. Although their exact molecular target remains to be elucidated, these compounds have potential as promising candidates for treatment of chronic HBV infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds and reagents.

AR-II-04-26 and MK-III-02-03 were synthesized by Sharon and colleagues according to the method previously described (29, 30). 3TC and ETV were purchased from AdooQ BioScience (Irvine, CA). IFN-α and DZNep were obtained from PBL Assay Science (Piscataway, NJ) and Selleck Chemicals (Boston, MA), respectively. These compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 20 mM or higher to exclude the cytotoxicity of DMSO and stored at −20°C until use.

Cell cultures.

HepG2.2.15.7 cells, from a HepG2.2.15 clone producing a larger number of viral particles, were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium-nutrient mixture F12 (DMEM-F12) medium supplemented with GlutaMAX (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fischer Scientific), 5 μg/mL insulin, 50 μM hydrocortisone, 10 mM HEPES, 400 μg/mL G418 (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (22). PHHs isolated from urokinase-type plasminogen activator transgenic (u-PA)/SCID mice inoculated with PHHs were purchased from PhoenixBio (Hiroshima, Japan). PHHs were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 20 mM HEPES, 44 mM NaHCO3, 15 μg/mL l-proline, 0.25 μg/mL insulin, 50 nM dexamethasone, 5 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 0.1 mM ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, 2% DMSO, 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (31). HepG2 cells were maintained in DMEM-F12 medium supplemented with GlutaMAX, 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin G, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Hep38.7-Tet cells (a HepAD38 clone) were cultured as previously described (22, 32).

Antiviral assays.

HepG2.2.15.7 cells were seeded onto a collagen type I-coated 96-well plate (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) at 1.0 × 104 cells/well. After incubation for 24 h, the cells were cultured in the presence of various concentrations of the test compound. Every 3 days, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing an appropriate concentration of the compound. After incubation for 9 days, the culture supernatants were collected and lysed with an equal volume of SideStep lysis and stabilization buffer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The amount of extracellular HBV DNA was quantified by real-time PCR analysis using the primer pair 5′-ACTCACCAACCTCCTGTCCT-3′ and 5′-GACAAACGGGCAACATACCT-3′ and the fluorescent probe 5′-FAM-TATCGCTGGATGTGTCTGCGGCGT-TAMRA-3′ (33). The real-time PCR was performed at 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min with TaqMan gene expression master mix (Thermo Fischer Scientific). The number of viable cells was determined by a tetrazolium dye method (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

HBV preparation and infection.

HBV (genotype D) was obtained from the culture supernatants of HepG2.2.15.7 cells. The culture supernatants were collected every 3 days for 30 days. The pooled supernatants were mixed with 10% polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG8000) and 2.3% NaCl and incubated for 12 h at 4°C. Viral particles were precipitated by centrifugation at 2,300 rpm for 30 min at 4°C and dissolved in serum-free DMEM. HBV DNA was quantified by real-time PCR. PHHs were infected with HBV at 100 to 200 viral genome equivalents per cell (vge/cell) in the presence of 4% PEG8000 for 20 h. The infected PHHs were washed with medium on days 1 and 2 after viral infection, and culture medium was replaced every 5 days (31). The cells were treated with various concentrations of the test compound during and after HBV infection. After 12 days, the extracellular HBV DNA and cell viability were analyzed as described above.

SAHase activity assay.

SAHase activity assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with some modifications (Axis-Shield Diagnostics, Dundee, UK). Briefly, SAHase was mixed with various concentrations of the test compound and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After incubation, l-homocysteine and adenosine were added to each sample and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped with adenosine deaminase. Subsequent manipulations were carried out by the manufacturer's protocol.

Analysis for HBsAg and HBeAg production.

HepG2.2.15.7 cells and PHHs were treated with the test compound as described above. The levels of HBsAg and HBeAg in the culture supernatants were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (HBsAg ELISA kit; Beacle, Kyoto, Japan; HBeAg ElLISA kit; Siemens AG, Berlin, Germany).

Analysis for cccDNA.

Total DNA was extracted from HBV-infected PHHs using a SMITEST EX-R&D kit (Medical & Biological Laboratories, Nagoya, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Five hundred nanograms of the extracted DNA was digested with 10 U of Plasmid-Safe ATP-dependent DNase (PSAD) (Epicentre, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 min at 37°C, followed by PSAD inactivation for 30 min at 70°C. Five microliters of the reaction sample was added to 15 μL of real-time PCR mixture. The real-time PCR was performed at 95°C for 10 min and 50 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min with PowerUp SYBR green master mix (Applied Biosystems) and the primer pair specific for HBV cccDNA, 5′-CGTCTGTGCCTTCTCATCTGC-3′ and 5′-GCACAGCTTGGAGGCTTGAA-3′ (23, 34).

Analysis for total RNA and capsid-associated HBV RNA.

Total RNA was extracted from HepG2.2.15.7 cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) or from PHHs with RNeasy minikit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Capsid-associated HBV RNA of HepG2.2.15.7 cells was purified by the following procedures. The cells were treated with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% NP-40), and the nuclei were removed by centrifugation. The cell lysate was incubated with 10 U of micrococcus nuclease and 6 mM CaCl2 for 30 min at 37°C. Capsid-associated RNA was extracted by adding 1 mL of TRIzol reagent. For Northern blotting, 10 μg of total RNA or a half volume of capsid-associated RNA was separated in a 1.2% gel with 2% formaldehyde. Total RNA or capsid-associated RNA was transferred onto a positive-charge membrane with 20× saline sodium citrate (SSC; 1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) buffer for 12 h using a capillary transfer method and cross-linked using a UV cross-linker. The membrane was hybridized with a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled full-length HBV DNA probe. For quantification of total RNA, cDNA was synthesized from the extracted RNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystem), followed by PCR with PowerUp SYBR green master mix and the primer pairs for total RNA (except for 0.7-kb HBx mRNA) (5′-ACTCACCAACCTCCTGTCCT-3′ and 5′-GACAAACGGGCAACATACCT-3′), for precore mRNA (5′-GGTCTGCGCACCAGCACC-3′ and 5′-GGAAAGAAGTCAGAAGGCAA-3′), and for 3.5-kb pregenomic RNA (5′-CTCAATCTCGGGAATCTCAATGT-3′ and 5′-TGGATAAAACCTAGCAGGCATAAT-3′), respectively (32, 35). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) RNA was used to normalize the RNA samples.

Analysis for intracellular core HBV DNA.

HepG2.2.15.7 cells and PHHs exposed to the test compound were treated with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% NP-40), and the nuclei and debris were removed by centrifugation. The cell lysate was treated with magnesium acetate (MgOAc; 6 mM), DNase I (200 μg/mL) (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ), and RNase A (100 μg/mL) (Nacalai Tesque) for 2 h at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by adding 10 mM EDTA and incubating for 15 min at 65°C. The cell lysate was treated with proteinase K (0.5 mg/mL) and 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and incubation for 2 h at 37°C. The intracellular core HBV DNA was purified by phenol-chloroform–isoamyl alchohol (25:24:1) extraction. For Southern blotting, 10 μL of extracted intracellular core DNA from HepG2.2.15.7 cells was loaded and separated in a 1.0% agarose gel. The agarose gel was denatured for 30 min in denaturation buffer (0.5 M NaOH and 1.5 M NaCl) and washed with neutralization buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl [pH 7.5] and 1.5 M NaCl) for 30 min. The intracellular core HBV DNA was transferred onto a positive-charge membrane with 20× SSC buffer using a capillary transfer method. The membrane was hybridized with a DIG-labeled full-length HBV DNA probe. For quantification of the intracellular core HBV DNA in PHHs, real-time PCR was performed as described above.

Analysis for capsid formation.

HepG2.2.15.7 cells exposed to the test compound were treated with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, and 1% NP-40), and the nuclei and debris were removed by centrifugation. The cell lysate was treated with MgOAc (6 mM), DNase I (200 μg/mL) (Worthington Biochemical), and RNase A (100 μg/mL) (Nacalai Tesque) for 2 h at 37°C, and the reaction was stopped by adding 10 mM EDTA and incubating for 15 min at 65°C. Ten microliters of the cell lysate was separated using a 1.0% agarose gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane with TNE (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) buffer using a capillary transfer method. The presence of core particles was examined by Western blotting using an anti-HBV core antigen (HBcAg) antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) (1:1,000 dilution).

Western blot analysis.

HepG2.2.15.7 cells exposed to the test compound were treated with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Nacalai Tesque) for 30 min on ice. After incubation, the cell lysate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C until analysis. For analysis, the samples were separated by electrophoresis in 12% SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Detection was carried out by an enhanced chemiluminescence prime Western blotting detection reagent (GE Healthcare Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Anti-HBcAg (Abcam) (1:1,000 dilution) and anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) (1:10,000 dilution) were used for the analysis.

Reporter assay.

pHBV-S1-Luc, pHBV-S2-Luc, pHBV-Luc, and pHBV-X/EnhI-Luc were gifts from Wang Shick Ryu (Addgene plasmid numbers 71416, 71417, 71414, and 71418) (36, 37). The pGL4.28 vector containing enhancer II and the basic core promoter region of HBV DNA (genotype D) were previously described (38). HepG2 or HepG2.2.15.7 cells were transiently transfected with each reporter plasmid in a 60-mm dish by Lipofectamine 2000 reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). After transfection for 24 h, the cells were split into a collagen-coated 96-well plate and incubated in the presence of various concentrations of the test compound for 24 h. The cells were treated with 1× lysis buffer (Promega, Fitchburg, WI), and the cell lysate was transferred into a white 96-well plate. The luciferase activity was measured by a luminometer with automatic injectors after adding the reagent in a luciferase assay system kit (Promega).

Analysis for total RNA derived from cccDNA.

Hep38.7-Tet cells were seeded into a collagen-coated 6-well plate. When the cells became confluent, they were incubated in the absence of tetracycline. After incubation for 14 days, the culture medium was supplemented with 1 μg/mL tetracycline and 10 μM 3TC. After 4 days, the cells were treated with 10 μM AR-II-04-26 or MK-III-02-03, and the culture medium was replaced by fresh medium containing an appropriate concentration of the compound every 2 days. At every point of time, the culture supernatants and the cells were collected. The levels of HBsAg in the culture supernatants were measured by an ELISA kit, and the total RNA and cccDNA were extracted from the cells, as described before (39).

Viral RNA degradation assay.

HepG2.2.15.7 cells were seeded onto a collagen type I-coated 24-well plate at 5.0 × 104 cells/well. After incubation for 3 days, the cells were treated with 10 μM AR-II-04-26 or 10 μM MK-III-02-03 and 10 μg/mL actinomycin D for 6, 12, and 24 h. Total RNA was extracted at the indicated time using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank M. Maeda for her secretarial work.

This research is supported by the Research Program on the Innovative Development and Application of New Drugs for Hepatitis B from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant number 21fk0310103h1005).

All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved its submission for publication in this journal. M.T. and M.B. designed this study. A.S. synthesized the NPA derivatives. K.W., M.I., A.Y., K.M., M.M., and T.W. prepared and provided the materials for mechanism analyses. M.T. conducted the experiments. M.T., K.W., M.O., T.W., and M.B. analyzed the results. M.T. and M.B. wrote the manuscript.

M.B. and A.S. are inventors of the patent for the NPA derivatives. Other coauthors have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2022. Hepatitis B, fact sheets. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b. Accessed on 3 February 2022.

- 2.Wursthorn K, Lutgehetmann M, Dandri M, Volz T, Buggisch P, Zollner B, Longerich T, Schirmacher P, Metzler F, Zankel M, Fischer C, Currie G, Brosgart C, Petersen J. 2006. Peginterferon alpha-2b plus adefovir induce strong cccDNA decline and HBsAg reduction in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 44:675–684. 10.1002/hep.21282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gish R, Jia JD, Locarnini S, Zoulim F. 2012. Selection of chronic hepatitis B therapy with high barrier to resistance. Lancet Infect Dis 12:341–353. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim SG, Wai CT, Rajnakova A, Kajiji T, Guan R. 2002. Fatal hepatitis B reactivation following discontinuation of nucleoside analogues for chronic hepatitis B. Gut 51:597–599. 10.1136/gut.51.4.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo JT, Guo H. 2015. Metabolism and function of hepatitis B virus cccDNA: implications for the development of cccDNA-targeting antiviral therapies. Antiviral Res 122:91–100. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gripon P, Cannie I, Urban S. 2005. Efficient inhibition of hepatitis B virus infection by acylated peptides derived from the large viral surface protein. J Virol 79:1613–1622. 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1613-1622.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen J, Dandri M, Mier W, Lütgehetmann M, Volz T, von Weizsäcker F, Haberkorn U, Fischer L, Pollok JM, Erbes B, Seitz S, Urban S. 2008. Prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in vivo by entry inhibitors derived from the large envelope protein. Nat Biotechnol 26:335–341. 10.1038/nbt1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schöneweis K, Motter N, Roppert PL, Lu M, Wang B, Roehl I, Glebe D, Yang D, Morrey JD, Roggendorf M, Vaillant A. 2018. Activity of nucleic acid polymers in rodent models of HBV infection. Antiviral Res 149:26–33. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roehl I, Seiffert S, Brikh C, Quinet J, Jamard C, Dorfler N, Lockridge JA, Cova L, Vaillant A. 2017. Nucleic acid polymers with accelerated plasma and tissue clearance for chronic hepatitis B therapy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 8:1–12. 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delaney WE, Edwards R, Colledge D, Shaw T, Furman P, Painter G, Locarnini S. 2002. Phenylpropenamide derivatives AT-61 and AT-130 inhibit replication of wild-type and lamivudine-resistant strains of hepatitis B virus in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:3057–3060. 10.1128/AAC.46.9.3057-3060.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deres K, Schröder CH, Paessens A, Goldmann S, Hacker HJ, Weber O, Krämer T, Niewöhner U, Pleiss U, Stoltefuss J, Graef E, Koletzki D, Masantschek RN, Reimann A, Jaeger R, Gross R, Beckermann B, Schlemmer KH, Haebich D, Rübsamen-Waigmann H. 2003. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by drug-induced depletion of nucleocapsids. Science 299:893–896. 10.1126/science.1077215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feld JJ, Colledge D, Sozzi V, Edwards R, Littlejohn M, Locarnini SA. 2007. The phenylpropenamide derivative AT-130 blocks HBV replication at the level of viral RNA packaging. Antiviral Res 76:168–177. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weber O, Schlemmer KH, Hartmann E, Hagelschuer I, Paessens A, Graef E, Deres K, Goldmann S, Niewoehner U, Stoltefuss J, Haebich D, Ruebsamen-Waigmann H, Wohlfeil S. 2002. Inhibition of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) by a novel non-nucleosidic compound in a transgenic mouse model. Antiviral Res 54:69–78. 10.1016/S0166-3542(01)00216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zoulim F. 2011. Hepatitis B virus resistance to antiviral drugs: where are we going? Liver Int 31:111–116. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yaginuma S, Muto N, Tsujino M, Sudate Y, Hayashi M, Otani M. 1981. Studies on neplanocin A, new antitumor antibiotic. I. Producing organism, isolation and characterization. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 34:359–366. 10.7164/antibiotics.34.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montgomery JA, Clayton SJ, Thomas HJ, Shannon WM, Arnett G, Bodner AJ, Kion IK, Cantoni GL, Chiang PK. 1982. Carbocyclic analogue of 3-deazaadenosine: a novel antiviral agent using S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase as a pharmacological target. J Med Chem 25:626–629. 10.1021/jm00348a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Clercq E. 2004. Antivirals and antiviral strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 2:704–720. 10.1038/nrmicro975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Clercq E. 2015. Curious (old and new) antiviral nucleoside analogues with intriguing therapeutic potential. Curr Med Chem 22:3866–3880. 10.2174/0929867322666150625094705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HJ, Sharon A, Bal C, Wang J, Allu M, Huang Z, Murray MG, Bassit L, Schinazi RF, Korba B, Chu CK. 2009. Synthesis and anti-hepatitis B virus and anti-hepatitis C virus activities of 7-deazaneplanocin A analogues in vitro. J Med Chem 52:206–213. 10.1021/jm801418v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou T, Guo H, Guo JT, Cuconati A, Mehta A, Block TM. 2006. Hepatitis B virus e antigen production is dependent upon covalently closed circular (ccc) DNA in HepAD38 cell cultures and may serve as a cccDNA surrogate in antiviral screening assays. Antiviral Res 72:116–124. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang JT, Yang Y, Hu YM, Liu XH, Liao MY, Morgan R, Yuan EF, Li X, Liu SM. 2018. A highly sensitive and robust method for hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA detection in single cells and serum. J Mol Diagn 20:334–343. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogura N, Watashi K, Noguchi T, Wakita T. 2014. Formation of covalently closed circular DNA in Hep38.7-Tet cells, a tetracycline inducible hepatitis B virus expression cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 452:315–321. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ladner SK, Otto MJ, Barker CS, Zaifert K, Wang GH, Guo JT, Seeger C, King RW. 1997. Inducible expression of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) in stably transfected hepatoblastoma cells: a novel system for screening potential inhibitors of HBV replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:1715–1720. 10.1128/AAC.41.8.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondo Y, Ninomiya M, Kakazu E, Kimura O, Shimosegawa T. 2013. Hepatitis B surface antigen could contribute to the immunopathogenesis of hepatitis B virus infection. ISRN Gastroenterol 2013:935295. 10.1155/2013/935295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang M, Schneller SW, Korba B. 2005. 5'-Homoneplanocin A inhibits hepatitis B and hepatitis C. J Med Chem 48:5043–5046. 10.1021/jm058200e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandra G, Moon YW, Lee Y, Jang JY, Song J, Nayak A, Oh K, Mulamoottil VA, Sahu PK, Kim G, Chang TS, Noh M, Lee SK, Choi S, Jeong LS. 2015. Structure-activity relationships of neplanocin A analogues as S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase inhibitors and their antiviral and antitumor activities. J Med Chem 58:5108–5120. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mueller H, Wildum S, Luangsay S, Walther J, Lopez A, Tropberger P, Ottaviani G, Lu W, Parrott NJ, Zhang JD, Schmucki R, Racek T, Hoflack JC, Kueng E, Point F, Zhou X, Steiner G, Lütgehetmann M, Rapp G, Volz T, Dandri M, Yang S, Young JAT, Javanbakht H. 2018. A novel orally available small molecule that inhibits hepatitis B virus expression. J Hepatol 68:412–420. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou T, Block T, Liu F, Kondratowicz AS, Sun L, Rawat S, Branson J, Guo F, Steuer HM, Liang H, Bailey L, Moore C, Wang X, Cuconatti A, Gao M, Lee ACH, Harasym T, Chiu T, Gotchev D, Dorsey B, Rijnbrand R, Sofia MJ. 2018. HBsAg mRNA degradation induced by a dihydroquinolizinone compound depends on the HBV posttranscriptional regulatory element. Antiviral Res 149:191–201. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thiyagarajan A, Salim MT, Balaraju T, Bal C, Baba M, Sharon A. 2012. Structure based medicinal chemistry approach to develop 4-methyl-7-deazaadenine carbocyclic nucleosides as anti-HCV agent. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 22:7742–7747. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasula M, Balaraju T, Toyama M, Thiyagarajan A, Bal C, Baba M, Sharon A. 2013. A conformational mimetic approach for the synthesis of carbocyclic nucleosides as anti-HCV leads. ChemMedChem 8:1673–1680. 10.1002/cmdc.201300277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishida Y, Yamasaki C, Yanagi A, Yoshizane Y, Fujikawa K, Watashi K, Abe H, Wakita T, Hayes CN, Chayama K, Tateno C. 2015. Novel robust in vitro hepatitis B virus infection model using fresh human hepatocytes isolated from humanized mice. Am J Pathol 185:1275–1285. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwamoto M, Cai D, Sugiyama M, Suzuki R, Aizaki H, Ryo A, Ohtani N, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Wakita T, Guo H, Watashi K. 2017. Functional association of cellular microtubules with viral capsid assembly supports efficient hepatitis B virus replication. Sci Rep 7:10620. 10.1038/s41598-017-11015-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Hussain M, Wong S, Fung SK, Yim HJ, Lok AS. 2007. A genotype-independent real-time PCR assay for quantification of hepatitis B virus DNA. J Clin Microbiol 45:553–558. 10.1128/JCM.00709-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mason AL, Xu L, Guo L, Kuhns M, Perrillo RP. 1998. Molecular basis for persistent hepatitis B virus infection in the liver after clearance of serum hepatitis B surface antigen. Hepatology 27:1736–1742. 10.1002/hep.510270638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laras A, Koskinas J, Hadziyannis SJ. 2002. In vivo suppression of precore mRNA synthesis is associated with mutations in the hepatitis B virus core promoter. Virology 295:86–96. 10.1006/viro.2001.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ko C, Lee S, Windisch MP, Ryu WS. 2014. DDX3 DEAD-box RNA helicase is a host factor that restricts hepatitis B virus replication at the transcriptional level. J Virol 88:13689–13698. 10.1128/JVI.02035-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cha MY, Ryu DK, Jung HS, Chang HE, Ryu WS. 2009. Stimulation of hepatitis B virus genome replication by HBx is linked to both nuclear and cytoplasmic HBx expression. J Gen Virol 90:978–986. 10.1099/vir.0.009928-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsukuda S, Watashi K, Iwamoto M, Suzuki R, Aizaki H, Okada M, Sugiyama M, Kojima S, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Li J, Tong S, Wakita T. 2015. Dysregulation of retinoic acid receptor diminishes hepatocyte permissiveness to hepatitis B virus infection through modulation of sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) expression. J Biol Chem 290:5673–5684. 10.1074/jbc.M114.602540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai D, Mills C, Yu W, Yan R, Aldrich CE, Saputelli JR, Mason WS, Xu X, Guo JT, Block TM, Cuconati A, Guo H. 2012. Identification of disubstituted sulfonamide compounds as specific inhibitors of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA formation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4277–4288. 10.1128/AAC.00473-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S4. Download aac.02073-21-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.6 MB (1.6MB, pdf)