ABSTRACT

Islatravir (ISL) is a nucleoside reverse transcriptase translocation inhibitor (NRTTI) that inhibits human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reverse transcription by blocking reverse transcriptase (RT) translocation on the primer:template. ISL is being developed for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. To expand our knowledge of viral variants that may confer reduced susceptibility to ISL, resistance selection studies were conducted with wild-type (WT) subtype A, B, and C viruses. RT mutations encoding M184I and M184V were the most frequently observed changes. Selection studies were also initiated with virus containing a single known resistance-associated mutation in RT (K65R, L74I, V90I, M184I, or M184V), and no additional mutations were observed. Antiviral activity assays were performed on variants that emerged in selection studies to determine their impact. M184I and M184V were the only single-codon substitutions that reduced susceptibility >2-fold compared to WT. A114S was an emergent substitution that when combined with other substitutions further reduced susceptibility >2-fold. Viruses containing A114S in combination with M184V did not replicate in primary blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), consistent with the rare occurrence of the combination in clinical samples. While A114S conferred reduced susceptibility to ISL, it increased susceptibility to approved nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs). This differential impact of A114S on ISL, an NRTTI, compared to NRTIs likely results from the different mechanisms of action. Altogether, the results demonstrate that ISL has a high barrier to resistance and a differentiated mechanism compared to approved NRTIs.

KEYWORDS: islatravir, antiretroviral resistance, human immunodeficiency virus

INTRODUCTION

Islatravir (ISL, also known as MK-8591 or 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine [EFdA]) is a nucleoside analog that is converted to the pharmacologically active triphosphate form (ISL-TP) via endogenous intracellular kinases. ISL-TP is a potent and specific inhibitor of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT) in vitro with unique mechanisms of action for blocking human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 replication. ISL-TP maintains a 3′-hydroxyl, in contrast to approved NRTIs which do not have this moiety, and therefore is not an obligate chain terminator. It inhibits reverse transcription via multiple mechanisms which can confer a unique mutant susceptibility profile. First, the 4′-ethynyl group blocks translocation of RT along the primer:template in the RT active site preventing further deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) binding and incorporation, thereby resulting in immediate chain termination. Second, in the event that translocation does occur, ISL inhibits RT via delayed chain termination. In this scenario, the 3′-OH can allow for addition of one nucleotide before ISL causes structural changes in the viral DNA and prevents further nucleotide incorporation. Last, ISL is efficiently misincorporated by RT (opposite nucleobase G, C, or A, rather than its cognate substrate nucleobase T or U), leading to mismatched primers that are difficult to extend and are protected from nucleotide excision (1–4).

ISL is currently being developed for the treatment of HIV-1 infection (5). Phase 3 studies of daily oral coadministration of ISL and the nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) doravirine (DOR) for HIV-1 treatment are ongoing. DOR is a clinically approved NNRTI that is indicated for treatment of people living with HIV-1 (PLWH) in combination with other antiretroviral agents (6).

Viral resistance selection studies and antiviral assays with HIV-1 variants have previously been conducted to understand the mutations within RT that alter susceptibility to ISL (7–10). These studies have primarily identified substitutions of M184 to V or I as the primary ISL resistance-associated variants. In this report, additional viral resistance selection experiments were performed with subtype A, B, or C wild-type (WT) viruses or subtype B viruses containing known resistance-associated mutations in RT. Antiviral activity assays were conducted on variants that emerged during selection; in addition, the replicative capacity of a select panel of viruses was also evaluated.

RESULTS

Resistance to ISL in vitro is associated with M184I or M184V in subtypes A, B, and C.

To expand our knowledge of viral variants that may confer reduced susceptibility to ISL in HIV-1 subtype A, B, or C, in vitro dose escalation selection studies were conducted in both 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 10% normal human serum (NHS). Amino acid substitutions that were observed at ≥4-fold the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) and in ≥2 wells on a plate are displayed in Table 1. In all replicate selection experiments conducted with subtype B (R8) virus (8 in 10% FBS and 8 in 10% NHS) and in all replicates of subtype A and C selection experiments conducted in the presence of 10% NHS (n = 8 for each), mutations encoding M184I and/or M184V substitutions were observed. No substitutions were observed in selection experiments with subtype A or C virus in the presence of 10% FBS, likely due to the short duration of these experiments (6 and 12 passages, respectively). In addition to M184I and M184V, V90VI and C162CY (mixtures of the WT V90 or C162 with V90I or C162Y, respectively) were also categorized as common mutations, as they were observed in more than 1 replicate experiment. While linkage was not established, all substitutions (with the exception of P313PT at passage 4 with subtype B virus in the presence of 10% NHS) were detected together with M184I or M184V. Among the other mutations, those encoding M41L, A114S, and A400T were the only ones that were not detected as mixtures with WT at the same codon. These mutations were rare and only observed together with M184V in a single replicate at passage 38 in the 10% FBS subtype B selection experiment.

TABLE 1.

HIV-1 RT substitutions observed in dose escalation selection experiments with HIV-1 subtypes A, B, and Ca

| HIV-1 subtype | Serum type | Passage no. | Amino acid substitutions (no. of replicate experiments observed) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commonb | Otherc | |||

| A | FBS | 6 | None observed | None observed |

| B | FBS | 4 | M184I (3), M184VI (2), M184MI (2), M184V (1) | E36EK (1) |

| 11 | M184I (6), M184V (2), | K166KRe (1) | ||

| 38 | M184MVI (3), M184V (3), M184I (1), M184MI (1), V90VI (1), C162CY (1) | K166KRe (1), G196GR (1), M41L (1), A114S (1), A400T (1) | ||

| C | FBS | 12 | None observed | None observed |

| Ad | NHS | 36 | M184I (6), M184VI (2) | None observed |

| B | NHS | 4 | None observed | P313PTe (1) |

| 25 | M184MV (1), M184I (1) | H221HYe (1) | ||

| 34 | M184V (3), M184MV (1), M184VI (4), V90VI (1) | E36ED (1), A158AT (1), H221Ye (1), P313PTe (1) | ||

| C | NHS | 36 | M184I (5), M184VI (3), V90VI (1) | L74LI (1), V75VA (1) |

FBS, fetal bovine serum; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; ISL, islatravir or MK-8591; NHS, normal human serum; RT, reverse transcriptase.

Common substitutions are those observed in ≥2 replicate experiments out of 8 for each HIV-1 subtype/serum combination.

Other substitutions are those observed in multiples wells within a single-replicate experiment.

C162CY was only detected in 1 replicate experiment from this experiment but was also observed in 2 of 16 replicates from a separate experiment (data not published).

eSubstitutions at K166, H221, and P313 were each observed at multiple passages in the same replicate experiment and are not considered common.

ISL did not select for additional mutations when selection was initiated with viruses containing NRTI resistance-associated mutations in RT.

In order to evaluate whether additional mutations that may confer reduced susceptibility to ISL could emerge in viruses already containing one of several common NRTI resistance-associated mutations, static selection studies were conducted using R8 virus containing mutations encoding single HIV-1 RT substitutions: K65R, L74I, V90I, M184I, or M184V. WT R8 virus was used in parallel as a control. Unlike in the dose escalation selections where ISL concentration was increased at each passage, static experiments included more input virus, and both cells and supernatant were passaged to the same ISL concentration every 3 to 4 days. Four independent experiments were performed as described in Table 2 with the viruses tested, number of replicates, ISL concentrations, and total passage number varied from experiment to experiment. Sequencing of viral RNA was performed at the final passage in all wells with evidence of viral replication.

TABLE 2.

Description of ISL static selection experiments with subtype B viruses containing known NRTI resistance mutationsa

| Expt no. | Virus | No. of replicates | ISL concentrations tested (nM) | No. of passages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WT, M184I, or M184V | 8 | 50.0, 25.0, 12.5, 6.25, 3.13, 1.56, 0.781, 0.391, 0.195, 0.0977, 0.0490, 0.0244 | 18 |

| 2 | WT, M184I, M184V, L74I, or V90I | 16 | 50.0, 25.0, 12.5 | 19 |

| 3 | K65R | 16 | 50.0, 25.0, 12.5 | 17 |

| 4 | WT, M184I, M184V, or L74I | 16 | 50.0, 25.0, 12.5 | 11 |

ISL, islatravir, also known as MK-8591; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; WT, wild-type R8 virus.

Across all the selections starting with WT virus there was no viral replication observed at concentrations above the ISL in vitro IC50 (0.79 nM); in the wells with viral replication there were no missense mutations detected in RT. Selection experiments starting with K65R, L74I, or V90I RT containing virus were each performed with ISL concentrations of 12.5, 25, and 50 nM, and there was no viral replication observed in the presence of ISL in any replicates, and therefore no sequencing was performed.

Selection experiments with virus encoding M184I or M184V were performed across a wider range of ISL concentrations. There was no evidence of viral replication at ISL concentrations of ≥6.25 nM (comparable to the IC50s for M184I [8.5 nM] and M184V [9.89 nM] RT containing viruses in 10% NHS) in any of these experiments. While viral replication was observed at concentrations of <6.25 nM, only the original M184I or M184V encoding mutations were observed, and no additional mutations appeared under ISL selective pressure.

Correlation of ISL concentrations in static selection experiments to intracellular ISL-TP concentrations.

As exposure targets for ISL efficacy are based on intracellular ISL-TP levels (11), the amount of ISL-TP available within cells in the static ISL concentration selection experiments was assessed. MT4 cells were treated with ISL at 10 nM, 100 nM, or 1,000 nM for 24 h, and cells were harvested for analysis of intracellular ISL-TP levels by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Concentrations of measured ISL-TP indicate that every 10 nM ISL added correlated with an additional approximately 0.1 pmol of intracellular ISL-TP per 106 MT4 cells. Therefore, ISL was effective at blocking viral replication of M184I- and M184V-bearing virus over multiple passages at intracellular ISL-TP concentrations as low as approximately 0.0625 pmol per 106 cells. ISL was also effective at blocking replication at ISL-TP concentrations as low as 0.125 pmol per 106 cells for K65R-, L74I-, and V90I-bearing virus and at all concentrations greater than 0.0078 pmol per 106 cells for WT RT-containing virus. These values are all below the ISL-TP levels observed with the 0.75 mg daily oral dose under investigation in phase 3 clinical studies (12).

ISL exhibited potent (nM) antiviral activity in vitro against HIV-1 variants that were selected during in vitro resistance selection studies with ISL.

To assess the impact of substitutions that were observed in selection studies on susceptibility to ISL, a multiple-cycle antiviral assay in MT4-green fluorescent protein (GFP) cells with 100% NHS was used to evaluate activity of ISL against WT HIV-1 R8 virus and a panel of 22 HIV-1 viral variants. As linkage was not established during the selection experiments, both single and combinations of mutations were constructed. ISL had potent activity (IC50 = 1.06 nM) for the WT R8 virus in this assay (Table 3). IC50 values for the single-codon variants ranged from 0.63 nM to 7.25 nM (fold change in potency compared to WT [FC] from 0.6- to 6.8-fold), and IC50 values for the combination variants ranged from 3.31 nM to 68.68 nM (FC from 3.1- to 64.8-fold). Of all single-codon variants tested M184I and M184V conferred the largest fold reductions in potency to ISL (FC of 6.2 and 6.8, respectively). Only combinations of variants containing M184I or M184V conferred reduced potencies greater than 6.8-fold. Combinations of M184 variants with V90I or C162Y did not reduce ISL potency more than 2-fold beyond M184I or M184V alone.

TABLE 3.

ISL susceptibility by multiple cycle assay (100% NHS) and clinical frequency for a panel of HIV-1 variants containing mutations observed in ISL viral selection experimentsa

| HIV-1 variant | IC50 (nM)b | FCc | Frequencyd (total PLWH) | Frequencyd (NRTI-experienced PLWH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 1.06 ± 0.21 (n = 40) | 1.0 | ND | ND |

| M41L | 0.80 ± 0.06 (n = 6) | 0.8 | 8.64 | 23.96 |

| L74I | 0.97 ± 0.09 (n = 12) | 0.9 | 1.40 | 3.99 |

| V90I | 0.93 ± 0.15 (n = 13) | 0.9 | 3.48 | 6.72 |

| A114S | 2.10 ± 0.31 (n = 11) | 2.0 | <0.01e | 0.01e |

| A158T | 0.97 ± 0.12 (n = 9) | 0.9 | 0.19 | 0.37 |

| C162Y | 0.63 ± 0.08 (n = 5) | 0.6 | 2.33 | 2.78 |

| T165A | 0.90 ± 0.13 (n = 6) | 0.8 | 0.08 | 0.17 |

| M184I | 6.56 ± 1.37 (n = 18) | 6.2 | 0.96 | 3.04 |

| M184V | 7.25 ± 1.81 (n = 18) | 6.8 | 19.11 | 56.15 |

| A400T | 0.77 ± 0.12 (n = 4) | 0.7 | 67.30 | 69.28 |

| M41L/A114S | 3.31 ± 0.69 (n = 4) | 3.1 | <0.01f | <0.01f |

| M41L/M184V | 5.98 ± 0.83 (n = 5) | 5.6 | 5.77 | 16.13 |

| L74I/M184I | 4.44 ± 0.73 (n = 5) | 4.2 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| V90I/M184I | 5.86 ± 1.75 (n = 5) | 5.5 | 0.31 | 1.04 |

| A114S/M184V | 40.14 ± 3.97 (n = 9) | 37.9 | <0.01f | <0.01f |

| C162Y/M184I | 3.87 ± 0.28 (n = 5) | 3.6 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| C162Y/M184V | 13.33 ± 1.15 (n = 5) | 12.6 | 0.60 | 1.66 |

| T165A/M184I | 7.80 ± 0.95 (n = 5) | 7.4 | <0.01f | <0.01f |

| T165A/M184V | 13.78 ± 2.24 (n = 5) | 13.0 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| M184V/H221Y | 7.93 ± 0.66 (n = 6) | 7.5 | 1.63 | 5.44 |

| M41L/A114S/M184V | 68.68 ± 5.79 (n = 5) | 64.8 | <0.01f | <0.01f |

| M41L/A114S/M184V/A400T | 62.34 ± 4.56 (n = 4) | 58.8 | Not observed | Not observed |

FC, fold change; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; ND, not determined; PLWH, people living with HIV; WT, wild-type.

IC50 is displayed as the geometric mean ± standard deviation.

FC is calculated as (IC50 against mutant isolate)/(IC50 against WT) for each test article.

Frequency of each variant = (number of PLWH with specified substitutions/total number of PLWH with sequence available at the specified residues) × 100. This value was determined without excluding variants with additional substitutions or mixtures at the designated residues using the Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database (18). The frequency data were calculated based on the database in February 2021.

There were 8 total and 5 NRTI-experienced PLWH with A114S detected.

Variants were present in 1 to 4 individuals within the Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database out of ~178,000 total or ~43,000 NRTI-experienced PLWH.

While the A114S mutation alone conferred a modest FC in potency of 2.0, this mutation was present in combination with M184V in the 3 variants that exhibited the largest potency reductions: A114S/M84V (FC = 37.9), M41L/A114S/M184V/A400T (FC = 58.8), and M41L/A114S/M184V (FC = 64.8). These combinations were all constructed due to their appearance in a single replicate experiment from resistance selection conducted with subtype B virus and 10% FBS as discussed above.

ISL has a distinct resistance profile compared to approved NRTIs.

As the mutations observed in ISL selection experiments have also been associated with some NRTIs, cross-resistance between ISL and NRTIs was evaluated in a multiple-cycle assay with 10% NHS against a select panel of HIV-1 variants, including 8 that were previously observed in ISL selection experiments and tested in the 100% NHS assay (Table 3), and 5 additional NRTI resistance-associated variants (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Antiviral activity of ISL and comparator molecules against a panel of HIV-1 variants with mutations in RT in a multiple cycle assay with 10% NHSa

| HIV-1 variant | ISL |

TDF |

AZT |

3TC |

FTC |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | |

| WT | 0.80 ± 0.08 (11) | 1 | 45.99 ± 11.56 (16) | 1 | 9.99 ± 1.38 (16) | 1 | 849.86 ± 265.52 (6) | 1 | 291.28 ± 47.80 (17) | 1 |

| M41L | 1.65 ± 0.11 (7) | 2.1 | 97.16 ± 12.88 (8) | 2.1 | 19.82 ± 2.50 (10) | 2 | 1,481.14 ± 301.45 (8) | 1.7 | 370.94 ± 54.58 (8) | 1.3 |

| K65R | 0.34 ± 0.06 (6) | 0.4 | 492.20; 580.36 (2) | 11.6 | 7.79; 9.42 (2) | 0.9 | 4,590.35; 4,787.03 (2) | 5.5 | NA | NA |

| L74I | 1.08 ± 0.09 (5) | 1.4 | 89.50 ± 25.02 (6) | 1.9 | 20.83 ± 3.42 (7) | 2.1 | 2280.97 ± 285.92 (5) | 2.7 | 576.15 ± 86.19 (8) | 2 |

| A114S | 1.74 ± 0.31 (4) | 2.2 | 2.89 ± 2.01 (6) | 0.1 | 4.67 ± 0.28 (7) | 0.5 | 715.56 ± 84.49 (4) | 0.8 | 217.75 ± 24.97 (8) | 0.7 |

| M184I | 8.50 ± 0.59 (7) | 10.6 | 44.96 ± 1.87 (4) | 1 | 8.68 ± 0.55 (4) | 0.9 | >42,016.67 (6) | >49.4 | >42,016.67 (4) | >144.2 |

| M184V | 9.89 ± 0.93 (7) | 12.4 | 48.09 ± 10.38 (4) | 1 | 9.40 ± 1.07 (4) | 0.9 | >42,016.67 (7) | >49.4 | >42016.67 (8) | >144.2 |

| T215Y | 1.99 ± 0.33 (7) | 2.5 | 192.86 ± 13.04 (3) | 4.2 | 82.79 ± 8.07 (6) | 8.3 | 4,045.70 ± 715.99 (5) | 4.8 | 1184.01 ± 135.29 (7) | 4.1 |

| A114S/M184V | 28.25 ± 6.93 ( 8) | 35.3 | 1.81 ± 0.38 (8) | 0.04 | 2.39 ± 0.40 (11) | 0.2 | >42,016.67 (10) | >49.4 | >42,016.67 (12) | >144.2 |

| M41L/A114S/M184V | 32.25 ± 6.20 (4) | 40.3 | 1.98 ± 0.25 (4) | 0.04 | 3.82 ± 0.38 (4) | 0.4 | >42,016.67 (4) | >49.4 | >42,016.67 (4) | >144.2 |

| M41L/L210W/T215Y | 2.95 ± 0.13 (4) | 3.7 | 271.97 ± 26.11 (4) | 5.9 | 73.80 ± 12.01 (4) | 7.4 | 1,796.43 ± 249.18 (3) | 2.1 | 764.22 ± 84.02 (7) | 2.6 |

| D67N/K70R/T215F/K219Q | 3.05 ± 0.43 (7) | 3.8 | 192.94 ± 7.21 (3) | 4.2 | 78.19 ± 12.79 (5) | 7.8 | 4,099.30 ± 508.53 (3) | 4.8 | 3,354.82 ± 218.48 (4) | 11.5 |

| D67N/K70R/A114S/T215F/K219Q | 2.72 ± 0.44 (6) | 3.4 | 3.51 ± 0.40 (7) | 0.1 | 6.73 ± 1.09 () | 0.7 | 969.34 ± 77.79 (3) | 1.1 | 646.52 ± 138.82 (7) | 2.2 |

3TC, lamivudine; AZT, zidovudine; FC, fold change; FTC, emtricitabine; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; ISL, islatravir; NA, not available; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; WT, wild-type.

IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration; nM) displayed as geometric mean ± standard deviation.

Fold change (FC) is calculated as (IC50 against mutant isolate) / (IC50 against WT) for each test article.

ISL was the most potent of the 6 compounds against the WT. The K65R NRTI resistance-associated variant was hypersusceptible to ISL (FC of 0.4), while susceptibility to both tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and lamivudine (3TC) was significantly reduced (fold change in susceptibility of 11.6 and 5.5, respectively). In contrast to ISL, which exhibits decreased potency against all variants containing A114S, NRTIs exhibited increases in potency against these variants. M184I and M184V, which conferred moderate reductions in potency to ISL (10.6- and 12.4-fold, respectively, in the 10% NHS assay), conferred large reductions in potency to both 3TC (>49.4-fold) and emtricitabine (FTC) (>144.2-fold) compared to WT, while these mutations had no impact on TDF or zidovudine (AZT). The single thymidine analog mutation (TAM), T215Y, conferred larger decreases in susceptibility to the NRTIs than to ISL. Susceptibility of the type 1 (M41L/L210W/T215Y) and type 2 (D67N/K70R/T215F/K219Q) pattern TAM combination variants was also assessed, and the fold change in susceptibility versus WT to ISL was similar or less than that observed for the NRTIs (Table 4).

The type 2 pattern TAMs were also evaluated in the context of A114S, as this combination was previously reported to reduce excision and thereby increase the potency of AZT in HIV-1 RT enzymatic assays compared to type 2 pattern TAMs alone (13). In contrast to effects on susceptibility to the NRTIs, addition of A114S to the type 2 pattern TAM variant (D67N/K70R/T215F/K219Q) did not have much effect on susceptibility to ISL (Table 4).

Susceptibility of variants containing A114S and/or M184V in PBMCs.

The susceptibility of WT, M184V, A114S, and A114S/M184V viruses to ISL and approved NRTIs (TDF, AZT, 3TC, and FTC) was also assessed in primary blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using a single-cycle assay with 10% NHS. These PBMC assays were run in parallel to circumvent any effects due to serum or PBMC donor. All compounds with the exception of TDF showed increased potency against WT in PBMCs versus the 10% NHS multiple-cycle assay in MT4-GFP cells (Table 4). Comparable fold changes against each of the variants were observed for the PBMC single-cycle and MT4-GFP cell multiple-cycle assays for all the 5 compounds tested. These data demonstrate that the contrasting effects of A114S on susceptibility to ISL versus approved NRTIs was recapitulated in both MT4-GFP cells and PBMCs. The data are summarized in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Antiviral activity of ISL, TDF, AZT, 3TC, and FTC with GFP-expressing virus in PBMCs (single cycle assay)a

| HIV-1 variant | ISL |

TDF |

AZT |

3TC |

FTC |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | IC50 (nM) (n)b | FCc | |

| WT | 0.23 ± 0.04 (4) | 1 | 47.28 ± 6.77 (4) | 1 | 6.42 ± 2.37 (4) | 1 | 114.09 ± 29.10 (4) | 1 | 42.44 ± 9.18 (4) | 1 |

| A114S | 0.44 ± 0.07 (3) | 1.9 | 3.41 ± 0.64 (3) | 0.07 | 2.71 ± 0.53 (3) | 0.4 | 101.58 ± 28.03 (3) | 0.9 | 27.18 ± 7.28 (4) | 0.64 |

| M184V | 1.07 ± 0.67 (3) | 4.7 | 26.40 ± 4.13 (4) | 0.6 | 2.63 ± 0.49 (4) | 0.4 | >42,017.67 (3) | >368.3 | >42,017.67 ± 0.00 (3) | >990.0 |

| A114S/M184V | 5.70 ± 0.80 (3) | 24.8 | 1.64 ± 0.29 (3) | 0.03 | 2.46 ± 0.28 (3) | 0.4 | >42,017.67; >42,017.67 (2) | >368.3 | >42,017.67 ± 0.00 (3) | >990.0 |

3TC, lamivudine; AZT, zidovudine; FC, fold change; FTC, emtricitabine; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; ISL, islatravir; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; WT, wild-type.

IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration; nM) displayed as geometric mean ± standard deviation, and individual values are listed if the replicates <3.

FC is calculated as (IC50 against mutant isolate)/(IC50 against WT) for each test article.

A114S variants have increased susceptibility to DOR.

As ISL is being coadministered with DOR to treat HIV infection in the clinic, cross-resistance between ISL and DOR was also evaluated in the multiple-cycle assay with 10% NHS against variants with decreased susceptibility to ISL. DOR had an IC50 of 5.75 ± 1.09 (n = 16) against WT R8 virus and maintained potent antiviral activity on the 5 resistance-associated variants that were tested. M184I and M184V each had 1.4-fold reduction in susceptibility to DOR, and A114S-containing variants, A114S, A114S/M184V, and M41L/A114S/M184V, had increased susceptibility to DOR with a FC of 0.5, 0.3, and 0.3, respectively.

Variants containing A114S have low replicative capacity.

In order to further probe the relevance of A114S variants, A114S/M184V and M41L/A114S/M184V were evaluated in a multiple-round replication assay in MT4-GFP cells and PBMCs to assess replicative capacity. WT HIV-1 and clinically relevant M184I and M184V viruses previously evaluated for fitness in vitro were used as controls as described in Materials and Methods (14).

The amount of input p24 required to obtain approximately 300 GFP-positive cells per well at 48 h postinfection of MT4-GFP cells was determined for each virus, and the fold change in input between WT and each variant was calculated (Table 6). The M184V, M184I, and M41L/A114S/M184V viruses required approximately 2-fold more virus input to obtain the same number of infected cells as the WT. The A114S/M184V virus required 6.4-fold more virus input than the WT.

TABLE 6.

Characteristics of HIV-1 virus preparations and assessment for replicative capacity in MT4-GFP cellsa

| HIV-1 variant | p24 (pg/mL)b | MT4-GFP normalized p24 inputc (pg/mL) | FCd | R0 by change in no. of GFP-positive cells | R0 by change in p24 level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 7.55 × 105 | 3.93 × 103 | 1.0 | 18.66 | 5.44 |

| M184V | 7.63 × 105 | 7.95 × 103 | 2.0 | 21.43 | 6.20 |

| M184I | 6.51 × 105 | 8.68 × 103 | 2.2 | 22.23 | 7.39 |

| A114S/M184V | 6.02 × 105 | 2.51 × 104 | 6.4 | 5.69 | 3.42 |

| M41L/A114S/M184V | 4.45 × 105 | 7.42 × 103 | 1.9 | 7.54 | 3.70 |

FC, fold-change; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1.

Concentrations of p24 were determined by titration of viral stocks across a wide range of dilutions and interpolation to a linear standard curve.

MT4-GFP normalized p24 input: the concentration of virus in pg/mL of p24 that was required to infect 8 × 104 MT4 GFP cells and detect approximately 300 GFP-positive cells 48 h after infection.

FC is calculated as (MT4-GFP normalized p24 input mutant)/(MT4-GFP normalized p24 input WT).

In order to determine if the viruses being evaluated have defects in replicative capacity, they were used to infect both MT4-GFP cells and PBMCs with virus input of 20 pg/mL or 100 pg/mL p24. Viral replication was evaluated for up to 10 days by monitoring GFP-positive cells (MT4-GFP cells only) and p24. The replicative ratio (R0) was calculated for the time points with exponential growth in the level of p24 in the supernatant and/or number of GFP-positive cells.

All viruses were able to replicate to some extent in MT4-GFP cells with both the 20 pg/mL and 100 pg/mL input infections (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). M184V and M184I viruses were only slightly delayed compared to WT virus. M41L/A114S/M184V and A114S/M184V viruses were delayed approximately 1 day measured by p24 and 2 to 3 days measured by GFP-positive cells. The R0 for the viruses in MT4-GFP cells were calculated (Table 6) and reveal that differences in R0 were more evident for the analysis based on the number of GFP-positive cells compared to p24 protein levels, indicating that analysis of p24 protein level may underestimate kinetic differences in viral replication. This is likely due to the fact that p24 is continuously produced by infected cells, and therefore, measured increases may not always reflect new rounds of infection. The longer time courses for the replicative capacity experiments also revealed a decreased R0 for the M41L/A114S/M184V variant versus the M184I and M184V variants that had not been as obvious in the data from normalized input in the 48-h infections.

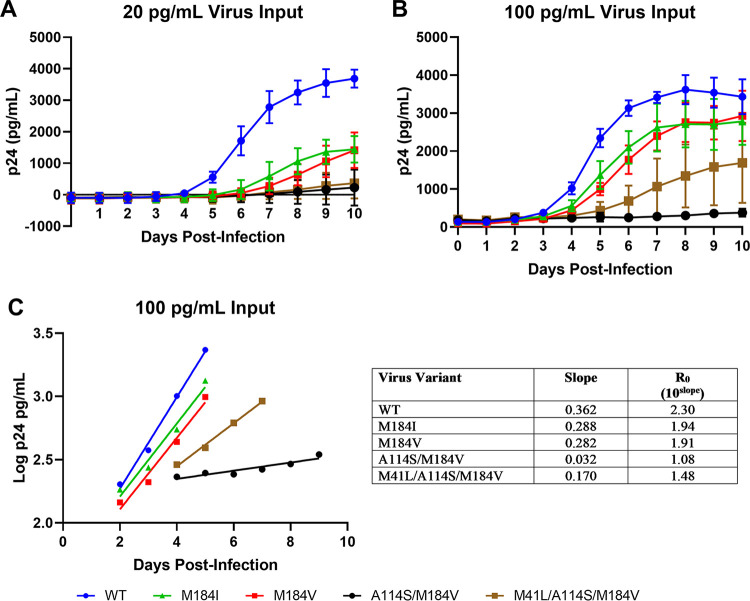

Replicative capacity was also assessed in PBMCs by monitoring p24 levels (Fig. 1A and B). In both the 20-pg/mL and 100-pg/mL virus input infections, increased levels of p24 were seen first for WT virus, followed by M184V and M184I. Growth of the M41L/A114S/M184V virus was evident with the 100-pg/mL virus input, although at much lower levels than those observed for M184V and M184I. Very low p24 protein levels were detected with the 20 pg/mL virus input, which suggested limited replication of M41L/A114S/M184V. Very low p24 protein levels were detected from A114S/M184V virus over the course of the experiment with either 20 pg/mL or 100 pg/mL virus input. The increases in p24 over time for A114S/M184V were likely caused by continuous secretion of p24 into the supernatant from a few infected cells rather than a result of multiple rounds of replication.

FIG 1.

Replication kinetics of virus variants in PBMCs. (A and B) Shown are replication kinetics of virus variants monitored by p24 protein levels in PBMCs of 20-pg/mL (A) and 100-pg/mL (B) virus input infections. Each data point in panels A and B is shown as the mean ± standard deviation from triplicate infections. (C) Assessment of the replicative ratio (R0) for the 100-pg/mL virus input infections. Each data point in panel C is the mean from 3 triplicate infections with linear regression, and the table depicts the slope and R0 for each variant. PBMC, primary blood mononuclear cell; WT, wild type.

Linear regression was performed during the exponential phase of p24 production to determine the R0 value for each virus (Fig. 1C). Since p24 values were used, the R0 values included p24 production and were likely overestimates of the rates of virus replication. The R0 values for M184I and M184V were slightly less than that for the WT (16% and 17% less, respectively), while the R0 for M41L/A114S/M184V was approximately 36% of that of the WT. The R0 for A114S/M184V was 1.08, which was only slightly above 1, indicating essentially no replication.

DISCUSSION

ISL is an NRTTI which inhibits HIV-1 RT through binding and incorporation into the growing strand at the active site. Unlike approved NRTIs, ISL contains a 3′-hydroxyl and 4′-ethynyl moieties which contribute to its unique mechanisms of action, including include immediate and delayed chain termination. These differentiated mechanisms of action have the potential to result in altered pathways to the development of resistance. Multiple resistance selection studies have been performed demonstrating that decreased susceptibility to ISL is mainly associated with changes at RT codon 184, which has previously been described as a discriminatory mutation for NRTIs (15). In order to more fully characterize the pathways associated with resistance to ISL and determine if there are additional resistance pathways that relate to its novel mechanism, we performed in vitro resistance selection studies with subtypes A, B, and C viruses or subtype B viruses with resistance-associated mutations in RT. The emergent variants were characterized by assessing their impact on antiviral potency and replicative capacity.

The in vitro dose escalation experiments starting with WT subtype A, B, or C virus confirmed previous observations (7, 8, 10) that M184V and M184I are the most frequent substitutions selected by ISL. These mutations confer modest 6.2- and 6.8-fold losses in susceptibility to ISL, respectively, when assayed in 100% NHS (Table 3). Inhibitory quotients (clinical minimum concentration of drug in serum [Cmin]/in vitro IC50) for WT virus with the 0.75-mg daily oral ISL dose currently being evaluated in phase 3 trials are >100 (12). Therefore, while M184V and M184I have been observed in vitro (7, 8, 10) and in vivo in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected rhesus monkeys treated with ISL (16, 17), ISL is expected to remain active against both of these mutations at clinical exposures. Other mutations were predominantly observed in combination with M184I and/or M184V. Neither V90I nor C162Y, which were characterized as common mutations, resulted in a greater than 2-fold change in susceptibility to ISL either compared to the WT or M184I/V (Table 3).

M41L, A114S, M184V, and A400T were observed together in a single replicate experiment with subtype B virus, and this was the only time that mutations encoding substitutions other than M184V or M184I were not observed as a mixture with the WT. M41L, A114S, and A400T were not observed in any other replicate experiments. M41L is a thymidine analog mutation (TAM) that is associated with resistance to most approved NRTIs, except 3TC and FTC. It did not alter susceptibility to ISL alone or in combination with M184V. A400T is an RT polymorphism that is observed in 67.30% of individuals in the Stanford HIV drug resistance database (18). It did not alter susceptibility to ISL alone or when added onto to the combination of M41L/A114S/M184V (Table 3).

A114S is very rare among clinical samples, with only 8 instances recorded across 178,309 total individuals sequenced through the Stanford HIV drug resistance database (≤0.01%) (18). Hence, A114S in combination with other mutations is expected to be exceedingly rare. Previous studies of A114S in vitro were initiated due to its location in a region of RT highly conserved across unrelated RT enzymes and demonstrated that introduction of A114S imparts a slight reduction in RT activity with effects in biochemical and viral assays (19, 20). Further studies have demonstrated that the reduced activity of the enzyme is due to decreased binding affinity for incoming dNTPs, and this leads to deficits in viral replicative capacity at low dNTP concentrations that could be present in some infected cells (21, 22). A114S has previously been shown to alter susceptibility of RT to some inhibitors in vitro, including AZT and foscarnet, a pyrophosphate analog polymerase inhibitor which is primarily used as salvage therapy for HIV-infected individuals, but has not been observed in the context of clinical resistance. A114S sensitizes virus to AZT in in vitro viral assays, and biochemical studies have demonstrated that A114S in combination with TAMs resensitized RT to AZT (13, 19, 21, 22).

A114S is part of the hydrophobic pocket where the 4′-ethynyl of ISL binds and was also observed in a resistance selection experiment with ISL described by Cilento et al. (10). In that experiment, A114S was observed in combination with M184V and A502V after 10 passages with escalating concentrations of ISL. Cilento et al. reported that the combination of A114S and M184V conferred a 24-fold decrease in susceptibility to ISL, which is similar to what we have reported here (24.8- to 37.9-fold [Tables 3 to 5]). They also noted reduced infectivity of A114S-containing variants and decreased catalytic efficiency of recombinant RT enzymes containing A114S with or without M184V resulting primarily from decreased binding affinity.

In this study, A114S only moderately reduced (~2.0-fold [Table 3 and 4]) susceptibility to ISL on its own; however, it was the only mutation tested which, in combination with M184V, reduced susceptibility to ISL >2.0-fold more than M184V alone. Unlike what was observed for ISL, A114S increased susceptibility to TDF, AZT, 3TC, and FTC on its own and to TDF and AZT in combination with M184V or M41L/M184V (Table 4). The low to nonexistent replication capacity of the A114S/M184V and A114S/M41L/M184V variants in PBMCs is consistent with its rareness among clinical sequences and makes it unlikely that these combinations will play a role in the clinic.

In order to further probe the mechanism of how A114S exerts its impact across the panel of compounds, we generated viral variants containing type 2 pattern TAMs with or without A114S similar to what had been previously reported using recombinant RT (13). Variants with the type 2 pattern TAMs conferred 3.8- to 11.5-fold reduced susceptibility to ISL and the clinical NRTIs compared to the WT (Table 4). When A114S was introduced in addition to the type 2 pattern TAMs, ISL susceptibility was not further altered, while susceptibility to the NRTIs was enhanced in the variants. While the mechanism of A114S resistance to AZT has been proposed to result from decreased pyrophosphorolysis (13), this mechanism is not expected to contribute to resistance to ISL. This is because ISL has a higher binding affinity and is incorporated by RT faster than adenosine, the natural nucleoside (3). Hence, ISL has a higher likelihood of being reincorporated into the growing viral strand after excision. This is highlighted by the inability of A114S to reduce the modest effect that the type 2 pattern TAMs have on ISL compared to the other compounds evaluated. The observed effects for ISL are likely due to steric hindrance against the 4′-ethynyl moiety (an essential structural element required for blocking RT translocation) in the pocket containing A114S relative to the WT. Unlike ISL, the 3′-hydroxyl lacking nucleos(t)ides which act through immediate chain termination do not have bulky groups entering the A114S pocket and are not discriminated against with these variants.

Because ISL is being coadministered with DOR for treatment of HIV infection in the clinic, the potency of DOR on variants with altered susceptibility to ISL was also investigated. DOR was potent on these ISL variants, with enhanced or minimally reduced susceptibility ranging from 0.3- to 1.4-fold. The increased susceptibility of A114S-containing variants to DOR makes it unlikely that A114S would emerge in the presence of DOR in the clinic.

Altogether, this work confirms previous observations that M184I and M184V, although having a modest impact, are the most common substitutions that alter susceptibility to ISL. With the exception of A114S, other substitutions observed in these studies had minimal effects on viral susceptibility alone or in combination with M184 substitutions. A114S augmented resistance conferred by M184V but had minimal effect (2-fold) on its own. A114S is rare in the clinic, and virus containing A114S in combination with M184V did not replicate in PBMCs. A114S also increased susceptibility to approved NRTIs and to DOR, making it unlikely that A114S will emerge frequently in the clinic. The high potency of ISL against RT variants shown here, coupled with its previously reported high inhibitory quotients (12) indicate a high barrier to resistance and continue to support ISL clinical development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Evaluation of antiviral activity in a multiple-cycle assay in MT4-GFP cells.

ISL was evaluated for its ability to prevent HIV-1 infection in MT4-GFP cells. In this method, HIV-1 replication is monitored using MT4-gag-GFP clone D3, MT4 cells with a GFP reporter gene, the expression of which is dependent on the HIV-1-expressed proteins, tat and rev (23). Infection of MT4-GFP cells with HIV-1 results in GFP expression approximately 24 h postinfection. Proviral variants used for these studies were generated by site-directed mutagenesis in the WT proviral plasmid R8 (24). Virus was produced by transfection in 293T cells.

MT4-GFP cells were placed in growth medium lacking G418 and cultured overnight with the appropriate HIV-1 variant at an approximate multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 under the growth conditions. Cells were then washed and resuspended in media containing the appropriate serum at 2 × 105 cells/mL. Compound plates were prepared by dispensing compounds dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) into 384-well poly-d-lysine-coated plates (0.2 μL/well) using an Echo acoustic dispenser. Each compound was tested in a 10-point serial 3-fold dilution (typical final concentrations: 8,400 nM to 0.42 nM). Controls included no inhibitor (DMSO only) and a combination of 3 antiviral agents, efavirenz, indinavir, and the integrase strand transfer inhibitor, L-002254051, at final concentrations of 4 μM each. Cells were added (50 μL/well) to compound plates, and the infected cells were cultured at 37°C, 5% carbon dioxide, and 90% humidity until evaluation of infection.

Infected cells were quantified at approximately 48 h and 72 h postinfection. The number of green fluorescent cells in each well was counted using an Acumen eX3 scanner (TTP Labtech, Inc., Melbourn, UK). The reproductive ratio, R, is calculated by dividing the number of infected cells at 72 h by those at 48 h postinfection. The percent inhibition caused by a test compound is calculated by the following formula:

The dose-response curves of each test compound were plotted as the percent inhibition versus the test concentration. IC50 values were determined by nonlinear 4˗parameter curve fitting of the dose-response curve data.

Dose escalation selection experiments with subtype A, B, and C viruses.

Selection experiments were performed in a 96-well-plate format with separate plates for initiating selection with subtype A, B, or C virus in the presence of 10% NHS or 10% FBS. Compound concentrations were selected using multiples above and below the compound’s IC50 in the multiple-cycle assay with the appropriate serum (Table S1).

The highest ISL concentration was in column 1, and the lowest was in column 11. Column 12 served as a virus control and feeder well with no compound (DMSO only). Compound concentrations were the same in all cells across a single column, and each row represented a replicate experiment totaling 8 replicates per virus/compound combination on a plate. Cells (MT4-GFP/CCR5 cells for subtype A and C viruses and MT4-GFP cells for subtype B virus) were infected with virus (subtype A [92RW026], B [R8], or C [93MW959]) at a low MOI so that <1% of cells would be GFP-positive in DMSO-containing wells 3 to 4 days after infection for subtype A and C, and <0.1% of cells would be GFP-positive in DMSO-containing wells 3 to 4 days after infection with subtype B.

After 3 to 4 days of culturing, a new selection cycle was initiated. The procedure used was as follows. A prepared compound plate containing the same amount of each compound as on the original plate was thawed; this was followed by the addition of fresh MT4-GFP cells (with or without a CCR5 coreceptor, depending on the virus subtype). Supernatant (30 μL) was removed from each well of the plate from the previous selection cycle and split into three 10-μL portions. These 3 portions were used to infect the freshly prepared cells in the wells at compound concentrations 1, 2, and 4 times the concentration in the original well from which the supernatant was removed. This procedure was repeated every 3 to 4 days on a Bravo liquid-handling station. For every passage, the plates were scanned with an Acumen eX3 cytometer to monitor the level of viral replication by the number of GFP-positive objects (cells). Supernatant was removed from the plate and stored at −80°C periodically for future genotyping analysis. Sequencing was performed after a minimum of 30 passages.

Static selection experiments with R8 virus containing WT, K65R, L74I, V90I, M184I, or M184V RT.

In vitro selection experiments were performed in 96-well plates with viruses containing known NRTI resistance-associated mutations (K65R, L74I, V90I, M184I, and M184V). In order to provide time for uptake of ISL and conversion to ISL-TP, MT4-GFP cells were added to 96-well plates containing the desired compound concentration and incubated at 95% humidity, 37°C, and 5% carbon dioxide for 24 h prior to addition of virus at each passage. Viruses (R8 WT, K65R, L74I, V90I, M184I, and M184V) were added to individual wells, and plates were incubated for 3 to 4 days at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide prior to initiation of the next selection passage.

The procedure used was as follows: a prepared compound plate containing the same amount of each compound as on the original plate was thawed; this was followed by the addition of fresh MT4-GFP cells and incubation at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide for 24 h. Then, 30 μL of culture (cells plus supernatant) was removed from each well of the plate from the previous selection cycle and transferred into the matched well on the new plate. This procedure was repeated every 3 to 4 days. For every passage, the plates were scanned with an Acumen eX3 cytometer to monitor the level of viral replication by the number of GFP-positive objects (cells). Supernatant was removed from the plate and stored at −80°C periodically for future genotyping analysis.

Genotyping analysis.

RNA isolation and sequencing were performed for wells with evidence of viral replication at indicated passages for each experiment. Viral RNA was extracted with the MagMAX-96 viral RNA isolation kit from culture supernatant. The RT-encoding region was amplified by the one-step RT-PCR method using a SuperScript III one-step RT-PCR system with Platinum Taq high-fidelity DNA polymerase and purified with ExoSAP-IT. PCR products were genotyped by an automated population-based full-length sequencing method (codons 1 to 440 of the RT region). The primers used for PCR amplification are described in Table S2. The primers used for sequencing are described in Table S3. Population sequencing was completed at Genewiz (South Plainfield, NJ, USA). Clonal sequencing was not conducted, and therefore, linkage between the mutations was not established.

Sequencing results were reported when mutations resulted in amino acid changes compared with HIV-1 92RW026 (subtype A), R8 (subtype B), and 93MW959 (subtype C) reference sequences. Sequence alignments were performed in SeqScape software v2.5 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Missense mutations leading to amino acid substitutions are depicted by referring to the change in the encoded protein with the single-letter amino acid code within the reference sequence followed by the amino acid position number within HIV-1 RT and then the single-letter amino acid codes predicted by the sequencing analysis; for example, M184I denotes that the amino acid at position 184 (M) is changed to an I, while M184MI indicates that the amino acid at position 184 is a mixture of M184 and M184I. For dose escalation selection experiments, where virus is constantly passed between multiple wells on a plate within each replicate experiment, substitutions were only included if they were present in ≥2 wells on a plate.

Clinical frequency analysis.

The frequency of each combination of mutations was determined among people living with HIV-1 (PLWH) by referencing the curated Stanford HIV Drug Resistance Database (18). The frequency was assessed (I) among all PLWH in the database and (II) among PLWH that are NRTI-experienced. Frequencies include the total number of variants containing each mutation, such as variants containing mutations that affect the single codon of interest, mixtures containing the assessed mutation and other mutations at the same codon, and combinations including additional mutations at other codons within RT. Hence, the assessment conservatively included multiple mutations present in an individual which may or may not be linked.

Evaluation of antiviral activity in a single-cycle assay in PBMCs.

To evaluate the ability of inhibitors to prevent HIV-1 infection in primary cells, human PBMCs obtained from Biological Specialty Corporation (Colmar, PA, USA) were used to assess antiviral activity. The proviral variants used for these studies were generated by site-directed mutagenesis in a proviral vector derived from NL43 (25) that encodes GFP. Virus was produced by transfection in 293T cells.

PBMCs were activated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) at 5 μg/mL in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS for 2 to 3 days. Compound plates were prepared by dispensing compounds dissolved in DMSO into 384-well poly-d-lysine-coated plates (0.2 μL/well) using an Echo acoustic dispenser. Each compound was tested in a 10-point serial 3-fold dilution (typical final concentrations: 5,000 nM to 0.1 nM). Controls included no inhibitor (DMSO only) and a combination of 3 antiviral agents, efavirenz, indinavir, and the integrase strand transfer inhibitor, L-002254051, at final concentrations of 4 μM each. PHA-activated human PBMCs were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% NHS and 30 units/mL interleukin-2 (IL-2) at 6 × 105 cells per mL. PBMCs were added to the compound plates and cultured for 24 h at 37°C, 5% carbon dioxide, and 90% humidity. The appropriate HIV-1 variant was added to the PBMCs and cultured at 37°C, 5% carbon dioxide, and 90% humidity for an additional 24 h.

HIV-1-infected cells were quantified by counting the number of green fluorescent cells in each well using an Acumen eX3 scanner (TTP Labtech, Inc., Melbourn, UK). IC50 values were determined by nonlinear 4-parameter curve fitting of the data.

Compounds were also tested against GFP-expressing HIV-1 variants harboring mutations that confer resistance to NRTIs in the PBMC-based replication assay. FC values were calculated by dividing the IC50 value for each resistant variant by the IC50 for WT HIV-1.

Evaluation of replicative capacity of mutant viruses in MT4-GFP cells and PBMCs.

HIV-1 viruses encoding WT RT or M184I, M184V, A114S/M184V, or M41L/A114S/M184V RT mutants were generated in parallel to assess their replicative capacities through monitoring virus spread via changes in the number of GFP-positive cells and/or capsid (p24) protein production over time in MT4-GFP cells and PBMCs.

(i) Virus production. HIV-1 WT R8 and R8-derived viruses encoding M184I, M184V, A114S/M184V, or M41L/A114S/M184V were produced in 293T/17 cells. Cells were plated in 10 mL Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS at 2.5 × 106 cells per dish onto 100-mm tissue culture-treated dishes (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) and incubated at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide. After 24 h, a transfection mix was prepared for each virus with 0.75 mL of Opti-MEM I and 60 μL of FuGENE 6 reagent, mixed by inversion, and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. Transfection mix was added dropwise into tubes containing 18 μg of proviral DNA plasmid at 1 μg/μL in Tris-EDTA buffer. Tubes were mixed gently by inversion and incubated at room temperature for 20 to 30 min before adding the mixture dropwise into the 100-mm dishes containing 293T/17 cells. Cells were incubated with DNA and transfection mix for 16 h at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide before supernatant was aspirated and replaced with 10 mL fresh DMEM with 10% FBS. Incubation at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide was continued for 48 h. Virus was harvested by collecting supernatant and centrifuging it at 142 × g to remove cell debris. Virus preparations were stored at −70°C in 250-μL aliquots.

(ii) p24 AlphaLISA. The levels of viral capsid (p24) were determined using the HIV p24 (high-sensitivity) AlphaLISA detection kit following the manufacturer’s suggested protocol with luminescence read on an EnSight multimode plate reader (Perkin Elmer, USA). Concentrations of p24 were determined by interpolation to a linear standard curve using Excel.

(iii) Determining virus titer based on volume. Titers of viruses were determined on MT4-GFP cells by plating 80,000 cells per well (in 100 μL) in 96-well plates and adding 50 μL of virus to column 1 and 50 μL of 2-fold serial dilutions of virus to each column thereafter. HIV-1-infected cells were quantified by counting the number of green fluorescent cells in each well using an Acumen eX3 scanner (TTP Labtech, Inc., Melbourn, UK) at 48 h postinfection. The amount of input p24 required to obtain 300 GFP-positive cells per well at 48 h was determined for each virus, and the fold change in input between the WT and each variant was calculated.

(iv) Replicative capacity evaluations. Assays to assess the replicative capacity of variants were performed in MT4-GFP cells or PBMCs. MT4-GFP cells were plated in RPMI 1640 with l-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 400 μg/mL G418 at 0.2 × 106 cells per mL in 3 mL in 6-well plates. Virus was added at a final concentration of 20 pg/mL or 100 pg/mL into each well, and 200 μL of cells with virus was transferred to at least 3 wells in a 96-well plate. Infections were incubated at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide. The HIV-1-infected cells were quantified daily by counting the number of green fluorescent cells using an acumen eX3 scanner (TTP Labtech Inc., Melbourn, UK). In addition, 30 to 50 μL of supernatant was removed from the remaining volume in the 6-well plate each day for p24 analysis.

Human PBMCs were obtained from Biological Specialty Corporation (Colmar, PA, USA). PBMCs were activated with PHA at 5 μg/mL in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS for 3 days. PHA-activated human PBMCs were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% NHS and 20 units/mL IL-2 at 1 × 106 cells per mL. Then 3 mL of cells was added to each well in a 6-well plate, and cells were infected at a final concentration of 20 pg/mL or 100 pg/mL virus. Incubation proceeded at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide, and 30 to 50 μL of supernatant was removed daily for p24 analysis.

GraphPad Prism 8 was used to plot changes in the number of infected cells and the concentration of p24 over time. Analysis of virus growth rates was computed using linear regression fit for the time points where exponential growth (measured in number of infected cells or levels of p24) was apparent for each infection. The slope was exported from the linear regression fit, and the replicative ratio (R0) was calculated in Excel with the equation R0 = 10Slope.

Data availability.

The consensus reference HIV-1 RT sequences that were used for alignment to identify novel mutations throughout the study were deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: ON351529 (R8, subtype B), ON351530 (92RW026, subtype A), and ON351531 (93MW959, subtype C).

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kirby KA, Singh K, Michailidis E, Kodama EN, Ashida N, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Sarafianos SG. 2011. The sugar ring conformation of 4'-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2'-deoxyadenosine and its recognition by the polymerase active site of HIV reverse transcriptase. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 57:40–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michailidis E, Huber AD, Ryan EM, Ong YT, Leslie MD, Matzek KB, Singh K, Marchand B, Hagedorn AN, Kirby KA, Rohan LC, Kodama EN, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Sarafianos SG. 2014. 4′-Ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) inhibits HIV-1 reverse transcriptase with multiple mechanisms. J Biol Chem 289:24533–24548. 10.1074/jbc.M114.562694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michailidis E, Marchand B, Kodama EN, Singh K, Matsuoka M, Kirby KA, Ryan EM, Sawani AM, Nagy E, Ashida N, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Sarafianos SG. 2009. Mechanism of inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine triphosphate, a translocation-defective reverse transcriptase inhibitor. J Biol Chem 284:35681–35691. 10.1074/jbc.M109.036616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muftuoglu Y, Sohl CD, Mislak AC, Mitsuya H, Sarafianos SG, Anderson KS. 2014. Probing the molecular mechanism of action of the HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitor 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine (EFdA) using pre-steady-state kinetics. Antiviral Res 106:1–4. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molina J-M, Yazdanpanah Y, Afani Saud A, Bettacchi C, Chahin Anania C, DeJesus E, Olsen Klopfer S, Grandhi A, Eves K, Robertson MN, Correll T, Hwang C, Hanna GJ, Sklar P. 2021. Islatravir in combination with doravirine for treatment-naive adults with HIV-1 infection receiving initial treatment with islatravir, doravirine, and lamivudine: a phase 2b, randomised, double-blind, dose-ranging trial. Lancet HIV 8:e324–e333. 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. 2019. PIFELTROTM (doravirine) prescribing information. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Whitehouse Station, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawamoto A, Kodama E, Sarafianos SG, Sakagami Y, Kohgo S, Kitano K, Ashida N, Iwai Y, Hayakawa H, Nakata H, Mitsuya H, Arnold E, Matsuoka M. 2008. 2′-Deoxy-4′-C-ethynyl-2-halo-adenosines active against drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40:2410–2420. 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeda K, Desai DV, Aoki M, Nakata H, Kodama EN, Mitsuya H. 2014. Delayed emergence of HIV-1 variants resistant to 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine: comparative sequential passage study with lamivudine, tenofovir, emtricitabine and BMS-986001. Antivir Ther 19:179–189. 10.3851/IMP2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takamatsu Y, Das D, Kohgo S, Hayashi H, Delino NS, Sarafianos SG, Mitsuya H, Maeda K. 2018. The high genetic barrier of EFdA/MK-8591 stems from strong interactions with the active site of drug-resistant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. Cell Chem Biol 25:1268–1278.e3. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cilento ME, Reeve AB, Michailidis E, Ilina TV, Nagy E, Mitsuya H, Parniak MA, Tedbury PR, Sarafianos SG. 2021. Development of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine starting with wild-type or nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor resistant-strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:AAC0116721. 10.1128/AAC.01167-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schürmann D, Rudd DJ, Schaeffer A, De Lepeleire I, Friedman EJ, Robberechts M, Zhang S, Liu Y, Kandala B, Keicher C, Däumer M, Hofmann J, Grobler JA, Stoch A, Iwamoto M, Ankrom W. 2021. Single oral doses of MK-8507, a novel non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, suppress HIV-1 RNA for a week. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 89:191–198. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rudd DJ, Cao Y, Vaddady P, Grobler JA, Asante-Appiah E, Diamond T, Klopfer S, Grandhi A, Sklar P, Hwang C, Vargo R. 2020. Modeling-supported islatravir dose selection for phase 3, abstr 462. Conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arion D, Sluis-Cremer N, Parniak MA. 2000. Mechanism by which phosphonoformic acid resistance mutations restore 3′-azido-3′-deoxythymidine (AZT) sensitivity to AZT-resistant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J Biol Chem 275:9251–9255. 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Back NK, Nijhuis M, Keulen W, Boucher CA, Oude Essink BO, van Kuilenburg AB, van Gennip AH, Berkhout B. 1996. Reduced replication of 3TC-resistant HIV-1 variants in primary cells due to a processivity defect of the reverse transcriptase enzyme. EMBO J 15:4040–4049. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb00777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shafer RW, Schapiro JM. 2008. HIV-1 drug resistance mutations: an updated framework for the second decade of HAART. AIDS Rev 10:67–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markowitz M, and, Grobler JA. 2020. Islatravir for the treatment and prevention of infection with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 15:27–32. 10.1097/COH.0000000000000599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphey-Corb M, Rajakumar P, Michael H, Nyaundi J, Didier PJ, Reeve AB, Mitsuya H, Sarafianos SG, Parniak MA. 2012. Response of simian immunodeficiency virus to the novel nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor 4′-ethynyl-2-fluoro-2′-deoxyadenosine in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4707–4712. 10.1128/AAC.00723-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhee S-Y, Gonzales MJ, Kantor R, Betts BJ, Ravela J, Shafer RW. 2003. Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database. Nucleic Acids Res 31:298–303. 10.1093/nar/gkg100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larder BA, Kemp SD, Purifoy DJ. 1989. Infectious potential of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase mutants with altered inhibitor sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:4803–4807. 10.1073/pnas.86.13.4803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larder BA, Purifoy DJ, Powell KL, Darby G. 1987. Site-specific mutagenesis of AIDS virus reverse transcriptase. Nature 327:716–717. 10.1038/327716a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cases-Gonzalez CE, Menendez-Arias L. 2005. Nucleotide specificity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptases with amino acid substitutions affecting Ala-114. Biochem J 387:221–229. 10.1042/BJ20041056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Cor-Hosmer SK, Daddacha W, Kelly Z, Tsurumi A, Kennedy EM, Kim B. 2012. The impact of molecular manipulation in residue 114 of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 reverse transcriptase on dNTP substrate binding and viral replication. Virology 422:393–401. 10.1016/j.virol.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y-J, McKenna PM, Hrin R, Felock P, Lu M, Jones KG, Coburn CA, Grobler JA, Hazuda DJ, Miller MD, Lai M-T. 2010. Assessment of the susceptibility of mutant HIV-1 to antiviral agents. J Virol Methods 165:230–237. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallay P, Swingler S, Song J, Bushman F, Trono D. 1995. HIV nuclear import is governed by the phosphotyrosine-mediated binding of matrix to the core domain of integrase. Cell 83:569–576. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adachi A, Gendelman HE, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin MA. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol 59:284–291. 10.1128/JVI.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1 to S3 and Fig. S1. Download aac.00133-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.4 MB (398KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The consensus reference HIV-1 RT sequences that were used for alignment to identify novel mutations throughout the study were deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers: ON351529 (R8, subtype B), ON351530 (92RW026, subtype A), and ON351531 (93MW959, subtype C).