Abstract

The past few decades have witnessed unprecedented global economic catastrophes that exacerbated pre-existing socioeconomic inequalities. Although many scholars have attributed the resulting social harms to the failures of neoliberal capitalism—and recognize it as criminogenic—the logics upholding the economic order continue to hold sway among the public. Given that these logics are commonly reinforced through media and popular culture narratives, in this paper we explore how economic inequalities are portrayed in American comic books. We employ a thematic analysis of comic book depictions of mass economic destruction and economic inequality from the financial crisis of 2008 through the Occupy Wall Street movement to the more recent characterization of a post-capitalist existence under the throes of a global plutocracy. In doing so we recognize the potential for re-imagining alternatives to neoliberal capitalism, taking a critical criminological lens to the comic books. We then place The Black Monday Murders, a culmination of portrayals of economic inequality and related violence, in the context of more mainstream comic book depictions and discuss how this particular work exemplifies a rising theme in comics—a purported trade-off between global capitalism and human life, a discussion point that explicitly entered American public discourse during the coronavirus pandemic.

Introduction

In 2008, the global financial collapse resulted in the loss of retirement and health care savings, foreclosures, job losses, and slowed household income growth among other impacts on millions of Americans (Kotz, 2015; Merle, 2018; Pew, 2010). Twelve years later, the coronavirus pandemic dwarfed the 2008 economic damage, plunging the global economy into a tailspin. In a linguistic twist minimizing harm from financial malfeasance, the common narrative of steep economic decline, described in the USA as the worst since the Great Depression, has been one of “crisis” or “disaster.” However, these economic collapses are better understood as crime events in which the global economy itself is implicated (Passas, 2005; Schecter, 2010; Wilson, 2012).

The abstract notion of capitalism as criminogenic was concretized by the response to the coronavirus pandemic in the USA as various pundits and politicians offered human lives in exchange for a robust economy (Tankersley et. al., 2020; Brown, 2020; Levitz, 2020; Barber et al., 2020). The pandemic posed a mortal threat, disrupted the economies of major countries around the world and fundamentally altered daily life. In the USA, President Donald Trump, though waffling on the federal response, put into place temporary guidelines for social distancing and individual states and counties added measures based on local rates of infection (The White House, 2020). The disruption to daily life, though severe and lasting many months, was necessitated as a life-saving measure, according to public health officials. However, the economy nose-dived with ten million jobs disappearing in the first two weeks of the crisis alone (Casselman & Cohen, 2020). On March 27, 2020, Congress passed an unprecedented $2 trillion dollar stimulus package to provide support to industries, small businesses, and recently unemployed Americans, as well as providing a cash payment to poor and middle-class Americans (Pramuk, 2020; The Economist, 2020). However, by May 28, 2020, the unemployment rate reached nearly one in four Americans where 40 million people were unemployed (Tappe, 2020) and more than 100,000 Americans had died of the virus. By the end of April 2021, the death count had reached nearly 600,000.

“Human Beings are Here to Serve the Economy”

Approximately two weeks into the pandemic in the USA, public discourse took a grim turn. Several pundits and officials, such as Lieutenant Governor of Texas Dan Patrick, said the risk to lives posed by the virus was a reasonable price to pay to revive the economy, arguing that social distancing, cancelations, and shut-downs should be reversed. He said he was in the “high-risk pool” for contracting a serious case of the virus, but nonetheless would sacrifice his life to preserve the economy for his children and grandchildren (Tankersley et. al., 2020). Soon thereafter, Patrick doubled-down by stating “There are more important things than living” (Brown, 2020). Similarly, a few weeks later former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie echoed Patrick’s sentiments, announcing that he felt that “…there are going to be deaths no matter what” and that keeping the economy open during the pandemic is a “sacrifice” worth making for the American economy and way of life (Silverstein, 2020).

The idea of reopening to bolster the economy, even if hundreds-of-thousands of people die, received positive nods from pundits on FOX News and other right-wing media, framing it as an acceptable cost of doing business. Lloyd Blankfein, former Chief Executive of Goldman Sachs, tweeted that willingly “crushing the economy” came with unacceptable costs: people with a lower risk of disease should return to work.” President Trump agreed when he tweeted “WE CANNOT LET THE CURE BE WORSE THAN THE PROBLEM ITSELF” (Levitz, 2020). As theorist Douglas Rushkoff (2020) put it, “Trump’s message [was] clear: The economy is not here to serve human beings; human beings are here to serve the economy.” Some, appalled at the notion of sacrificing American lives, took to Twitter posting comments such as “They [Trump and allies] would bury [their] own grandmother for a buck” (Joe the Voter, 2020). By April 10, 2020, there seemed to be no alternative frame for discussing how we may navigate through the pandemic as the New York Times invited “five thinkers” to debate who is worth saving in our quest to reopen the economy (Barber et al., 2020). A year later, The Guardian asked “Has Covid changed the price of life?” in an article which outlined the primary philosophical perspectives used by economists and epidemiologists to debate the “moral and economic minefield” of governments determining how much economic spending or economic loss is warranted to save life during a pandemic (Spinney, 2021). Of note, a cross-national analysis of GDP effects due to lockdowns before and after vaccine availability shows that indeed there is a negative economic effect in the short-term from public health measures, but that significant recovery gets underway within months. The panicked notion that lockdowns destroy economies is not so far supported by academic review of the data (König and Winkler, 2021).

It is not a new problem in the neoliberal USA to see incidents when profit is prioritized over lives, but rarely does this profit-prioritization receive the attention that the economy-or-your-life discourse during the pandemic did. For instance, in early 2020 Purdue Pharma pled guilty to fraud, having unethically pushed opioid prescriptions which played a large role in the opioid addiction crisis and increased their profits. In 2017, more than 47,000 people overdosed on prescription opioids and died, with tens of thousands more having died of illicit opioids, the use of which may have stemmed from an initial prescription (NIH, 2021). Similarly, the tobacco industry engaged in unethical behavior when it suppressed the dangers of smoking; likewise the lead paint industry covered up the health effects of lead poisoning. Although concern surfaced in all these examples of corporate malfeasance, the coronavirus was framed as affecting everyone in society and more explicitly exposed that many Americans, particularly of the wealthy classes, have long been implicitly comfortable with bloodletting for the economy. The opioid crisis, the dangers of smoking, and lead paint, on the other hand, were parsed as problems of the addicted and marginalized.

The new-found prominence of the notion of sacrificing human lives on the altar of the economy eerily resonates with a recent critically acclaimed comic book series, The Black Monday Murders (Vol. 1, 2017; Vol. 2, 2018) by Jonathan Hickman and Thomm Coker.1 The book depicts a dystopian world where a cabal of billionaires runs the global economy through an organized crime network that has co-opted government and requires allegiance to the devil and his requisite blood sacrifice. Capitalism has a body count in The Black Monday Murders, linking the functioning of the economy to routine violence, an ideology that values money over people, and a secret vampire cult. Avoiding victimization means bowing to the blood economy, devoting your life to the corrupt system at the expense of others. When the comic book was first published as single issues in 2016, the dystopian world envisioned by Hickman and Coker seemed like just another creative extrapolation based on the ordinary excesses of capitalism.

Our goal in this paper is three-fold. First, we suggest that comic books are situated within a broader popular cultural scaffolding that sustains neoliberal logics. Here we question whether this dynamic is inevitable or whether disruption is possible. We do this by rooting our theoretical perspective in critical criminology, recognizing the harms of capitalism as criminogenic, and by suggesting that though the logics are culturally sustained, they are not necessarily immutable. As we did in our earlier work (Phillips & Strobl, 2013), we focus on mainstream comic books due to their wide readership relative to other titles. In doing so, we assume that challenges to neoliberal logics are more likely to resonate in work that reaches more people. We acknowledge, however, that critically acclaimed books that are not best-sellers are important contributions to the medium.

Second, we show that mass economic disruption and the toll that capitalism takes on working people have sometimes been themes in American comic books historically but are becoming more palpable in recent years. We note that comics that forefront black superheroes, for example, take on class issues in displays of characters' double marginality in terms of race and socioeconomic standing. But our main thrust points to various books influenced by Occupy Wall Street (OWS) through a purposive sample of books that have plots involving economic inequality, purposively selected because they prompted a fair amount of discourse around how economic inequalities flow throughout comic narratives. We approach our analysis with the understanding that text, images, readers, and creators are intertwined in a popular cultural conversation producing a discourse on capitalism, economic inequality, crime and justice (Levi, 2006; Reiner, 2007; Phillips & Strobl, 2013). In doing so, we are conducting a broad thematic analysis in order to highlight and evaluate what we see as a turn toward plots that focus on economic inequality as a structural foundation for crime and violence. We rely heavily on not just our own interpretation of the texts, but on various commentaries around the books from scholars and comic book fans, as well as select statements by the creators. We believe it is this flow of discourse around the thematic content of the books that contributes to the possible rupturing of the perception that neoliberal capitalism is inevitable.

Third, we highlight The Black Monday Murders (2016–2018) because we found it to be among the most concrete expressions of the overall turn toward themes around neoliberal capitalism as exacting a toll on human life. The book foregrounds the violence of neoliberal capitalism, the relevance of which was brought to the fore during the coronavirus pandemic and controversies around keeping economies functioning even if people get sick and die. The book forces the reader to grapple with the fact that the system itself demands human sacrifice, even if we are not always willing to acknowledge it, themes that are also picked up contemporaneously in Lazarus (2013–2018) and The Flintstones (2016).

Critical Criminology and the Rigged Economy

It is well-documented that economic prosperity in the USA was built on the back of slave labor and the subjugation of the marginalized. This oppression was enforced through state violence and reinforced through decades of legal, social, and cultural fortification of capitalism. Theoretically, we draw broadly from a critical, Marxist perspective which puts forth that the greatest crimes in Western, capitalist societies are the unjust structures of capitalism, where institutions of power exploit lower class people. According to Quinney’s (1977) work linking Marxism and criminology, the most serious crimes in society are the perpetuation of poverty and inequality (along with racism and sexism). According to Quinney, the mechanisms of law and the state help perpetrate crimes of economic domination by elites. Collectively, popular cultural imaginings determine what perspectives about economic inequality are seen as “normal” or “natural.” Capitalism thrives on economic egoism while simultaneously downplaying altruistic concerns. As Bonger explains, it diminishes the “moral force in man which combats the inclination towards egoistic acts” and those egoistic acts are sometimes criminal (Bonger, 1916: p. 532; Stichman 2010).

Although Karl Marx suggested uprisings among the exploited working class would signal the demise of capitalism, such an outcome never fully materialized in the USA and elsewhere. Instead, over the past decades there emerged a significant cultural embrace of the logics of neoliberalism, the embrace of free-market ideology, deregulation, the privatization of public goods, services, and spaces, and an emphasis on individual responsibility (Alvaredo et al., 2017; Blyth, 2013; Fukuyama, 1992; Hall, 2012; Harvey, 2005; Kotz, 2015; White, 2017). As cultural theorist Mark Fisher noted, “Fukuyama’s thesis that history has climaxed with liberal capitalism may have been widely derided, but it is accepted, even assumed, at the level of cultural unconsciousness” (2009: p. 6). Indeed, as global economic inequalities continue to increase, the logics of neoliberalism boost the implementation of austerity measures, the erosion of public services, and function to legitimate repressive state policies.

Within criminology, the dynamics of oppression and subjugation as a result of neoliberal capitalism have been theorized to explain how the criminal justice system disadvantages the poor while serving as a buffer for the wealthy (Reiman & Lieghton, 2016), exacerbate mass incarceration and the punitive state (Gottschalk, 2006; Harcourt, 2011; Wacquant, 2009; Xenakis & Cheliotis, 2018), and, more broadly, to further our understanding of criminology’s “aetiological crisis” (Hall, 2012; Kotzé, 2019; Matthews, 2014, 2016; Young, 2011).2

Moreover, critical criminologists refute the misconception that crimes of capitalism are mostly non-violent acts and acknowledge violence perpetuated for financial and economic gain of economic elites, or “red collar” crimes (Brody & Kiehl, 2010; Perri, 2011). These include perpetrators threatening and murdering potential whistle-blowers or perpetuating unsafe working conditions in the name of lowering the production costs that then lead to worker injuries and deaths. Within criminology, studies have underscored physical, social, and economic harms caused by crimes of the powerful perpetrated by people in positions of trust, whether in the private sector or those in government working to regulate the financial industry, while also recognizing the lack of social concern for them relative to other types of crime (Hall & Winlow, 2015; Kotzé, 2019; Kauzarlich & Rothe, 2014; Reiman & Leighton, 2016; Rothe & Kauzlarich, 2016; Winlow and Hall, 2019). Overall, incidents of financial crime are normalized as part of the necessary workings of the economic system.

While the material consequences of neoliberal capitalism have been felt among the populace, the logics are rarely challenged and considered an inevitable consequence of modernity (Fisher, 2009; Fukuyama, 1992). The status quo is viewed as part of the natural order through a process outlined by Italian theorist Antonio Gramsci who posited that exploitative practices are kept in place not necessarily by sheer brute force, but by the cultural embrace of ruling class ideas (Bates, 1975). In this way, culture operates as a significant force in shaping values, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that sustain neoliberal logics. Efforts to sustain the free market at any cost are viewed as a natural and inevitable part of contemporary society. The result is what Fisher described as capitalist realism, a social existence of collective cynicism, apathy, demoralization, and powerlessness (Fisher, 2009). Without alternative imaginings, as Fisher and other social theorists argue, we are unable to envision any alternative to our current political and economic conditions (Fisher, 2009; 2018).

In the 21st Century, however, some observers have noted a loosening of the seemingly infrangible grip of neoliberalism (Patience, 2017; Jacques, 2016; Sunkara, 2019; Winlow and Hall, 2019). In 2011, OWS was a catalyst for raising awareness around economic inequalities, but the political apparatus has been slow to offer alternatives. Despite shifting the Overton window to include policy positions such as universal health care and increased minimum wage, as Fisher (2018) cautioned, “zombie capitalism” lingers on, dominating our institutions. In fact, the political response to the pandemic has further enriched the wealthiest billionaires while globally hundreds of millions are left in desperation (Blumberg, 2018; Gustafson et al., 2018; Sheffield, 2019; Rushe & Chalabi, 2020).

As disaster capitalism looms in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, it is too soon to say whether this dystopian landscape will subside, but nothing is forever fixed (Solis, 2020). Viable alternatives are on the horizon if we are willing to embrace them. Political scientist Allan Patience writes that the end of neoliberalism portends two options, “Either a post-capitalist, grimly neo-fascist world awaits us, or one shaped by a new and highly creative version of communitarian democracy. It’s time for some great imagining” (Patience, 2017).

Comic Books and Imaginations of Economic Inequality

In our previous work examining mainstream American comic books spanning nearly a decade (2002–2010), we found that crime is usually depicted as interpersonal violence or street crimes (Phillips & Strobl, 2013). What we found to be missing were narratives implicating broader social structures, such as capitalism. In other words, critical theories were rarely implicated, neglecting how the socioeconomic structure may itself be criminogenic. As a result, we found few mainstream narratives that imagine justice as a political project requiring the reconstruction of economic arrangements. This is not to say that historically comics have not addressed social and economic inequalities. In fact, these types of themes have resonated throughout the years, but they have often championed neoliberal logics rather than challenging them.

As a product of their social and cultural milieu, comics have always reflected socioeconomic-political anxieties (Brown, 2001; Cocca, 2016; Fawaz, 2016; McAllister et al., 2001; Nama, 2011; Weinstein, 2009; Wright, 2003). Scholar Bradford Wright describes comics published during the 1940s as propagandistic, championing WWII efforts that aligned with American values of democracy and freedom (2003: p. 42). Similarly, scholar Ramzi Fawaz argues that the era produced narratives of the “…superhero as local do-gooder and loyal patriot” (2016: p. 4). However, eventually post-WWII comics moved away from the nationalist, patriotic themes to explore heroes’ vulnerabilities as social outcasts that challenged dominant hegemony (Fawaz, 2016).

As the war ended, superheroes receded in popularity and other genres gained prominence. When superheroes reemerged in popularity, they reflected cultural shifts in American society. For example, Fawaz suggests that narratives in the 1960s reflected the real-world left-wing political movements of the time and offered a radical politics through their embrace of in-flux identities, feminist ideals, anti-racism and anti-colonialism in an inter-galactic setting. It is in this era, and moving into the 1970s, that we see explicit references to socioeconomic inequalities. For instance, Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor (1976) has Marxist implications. The main character (also named Harvey Pekar) struggles with his perception that he is overlooked and under-appreciated as a feature of lower middle-class life (Booker, 2014: p. 503). In American Splendor #4 (1979), as a result of money problems, Pekar turns to stealing jazz records–his obsession–from a radio station.

In addition, scholars have pointed to Denny O’Neill and Neal Adams’ Green Arrow/Green Lantern (1976–1977) run as a scathing indictment on how racism and economic inequalities are “killing us all” and are a “moral cancer…rotting our very souls,” in a nod toward the double marginality people experience by way of race and class. As we explained in Comic Book Crime (2013), focus groups of New York City comics fans revealed that black representations in comics were welcomed by black readers regardless of the nature of the representation. Being represented at all was a first step toward being represented well. In Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes, Adilifu Nama (2011) wrote about how significant Green Arrow/Green Lantern was in addressing the political tensions at the time and pushing the boundaries of discourse around social inequalities:

“...because Green Lantern and Green Arrow were addressing such immense social issues [about] the sweeping cultural fallout and the emotional trauma the American psyche suffered from witnessing a spate of political assassinations on American soil. Green Arrow and Green Lantern functioned as elegant cultural ciphers that openly questioned the crisis of meaning and identity that Green Arrow expresses in his lament over the assassinations. [The] Green Lantern Co-Starring Green Arrow comic book series was symbolically sophisticated when confronting white privilege and racial injustice in America.”

Eventually, the strains of radical politics of the 1960–70s gave way to the Reagan-Thatcher era of the 1980s during which the logics of neoliberal capitalism solidified in the public imagination. Some acclaimed comics were critical of the politics of the day and imagined dystopian landscapes exploring the consequences of authoritarianism. For example, Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta (1982) examined trauma and terror in an imagined England descending into fascism. In another dystopian tale, Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen (1986) deconstructed the superhero genre and illustrated the corrosive nature of absolute power, while Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986) presented a rather authoritarian Batman reemerging from retirement to a media-saturated environment rife with crime, gang violence, and terrorism. In mainstream comics, narratives involving ostentatious wealth such as the inherited fortunes of Bruce Wayne (Batman), Oliver Queen (Green Arrow) and Tony Stark (Iron Man), have most often been used to bolster the neoliberal notion that private assets are more valuable in fighting crime than social resources. As is common in mainstream superhero comics, the solution to social ills are not to be found in the redistribution of resources or reallocation of political power, but instead in the visceral display of apocalyptic incapacitation in which the status quo is reset.

In this way, critiques of capitalism are not necessarily absent; they weave through storylines, but do not posit the need for a revolutionary solution. Fawaz observed that during the 1980–90s the perils of capitalism served as a backdrop for the psychic manipulation and emotional breakdown of individual characters. For example, he identified a recurring trope of demonic possession that “…linked the psychic corruption of their central superheroic characters to the machinations of global capitalism” (p. 202). In The Uncanny X-Men (1980), mutant Jean Grey was portrayed as a possessed megalomaniac determined to devour the entire cosmos. Fawaz positions this narrative within the coterminous cultural critique of rampant consumerism, self-interest, and narcissism. For Fawaz, the proliferation of demonic possession narratives served “as a metaphor for the rapacious expansion of late capitalism” (Fawaz: p. 205).

In our prior research on mainstream comic books, we saw few narratives that implicated neoliberal capitalism as criminogenic (Phillips & Strobl, 2013). In books published after 9/11, we instead recognized a grappling with American hegemony through narratives exploring the role of superheroes in a new world order in which America’s dominance was strained. Narratives ranged from the reactionary to the pacifist and there was no recognizable monolithic response. We interpreted the post-9/11 fissure in comics as a promising avenue for acknowledging the historically marginalized and we observed efforts to increase diverse representations along racial, ethnic, gender, and sexual orientation identities. It was after 9/11 that comics increased the representation of people of color as superheroes, with such notable examples as Miles Morales, a biracial Spider-Man, and the reinvigoration of the character of Black Panther in a self-titled comic series and an acclaimed movie. In Super Black, Nama (2011) goes beyond representation to provide a deeper analysis of the social, cultural, and political importance of black superheroes over decades, writing,

But black superheroes are not only representative of what is racially right. They are also ripe metaphors for race relations in America, and are often reflective of escalating and declining racial unrest. In this sense, black superheroes in American comic books and, to a lesser extent, in Hollywood films and television are cultural ciphers for accepted wisdom regarding racial justice and the shifting politics of black racial formation in America.

In our prior work, we noted that in post 9/11 narratives, the dystopian present teetered on the brink of an apocalyptic breaking point commonly prompted by acts of terrorism, genocide, organized crime, and government malfeasance against the backdrop of geopolitical and inter-galactic intrigue (Phillips & Strobl, 2013). As Fawaz pointed out, during this time the radical edge of mainstream books was muted by both the commercial aspects of the industry and the lack of real-world social movements advocating for vast restructuring to upend economic inequalities. However, we suggest a somewhat more optimistic view moving forward and argue that social reaction to the crimes that prompted the 2008 crisis, the subsequent emergence of OWS, and the inadequate and reckless federal government response to the coronavirus pandemic pave the way for new critiques of neoliberal capitalism in comics.

Occupy Wall Street: A Turning Point for Comics

OWS, which arose in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, influenced portrayals of socioeconomic inequalities in comics published by the “Big Two” (DC and Marvel) as well as other publishers that comprise a smaller market share. We identified narratives that critiqued neoliberal capitalism as criminogenic. Overall, much like the impact of 9/11 on comics, these narratives ranged from the relatively superficial appropriation of language (e.g., the 2012 Archie featuring an Occupy Riverdale storyline referencing the plight of the 99%) to titles offering more robust critiques.

Notably, in 2012, Black Mask Studios published Occupy Comics and donated proceeds to Occupy protesters. Initially launched as a Kickstarter project, the book gives voice to artists and other creators inspired by the potential for social change, but the project initially had difficulty landing a publisher. The Kickstarter page detailed their aims,

”…We are comic book [and] graphic novel artists and writers who've been inspired by the movement and hope to tell the stories of the people who are out there putting themselves at risk for an idea. What is that idea? Most of the media will tell you the idea is a vague and befuddled mess, but movements don't coalesce around vague, befuddled messes….”

Prompted by the desire to see the book to fruition, Matt Pizzolo, Steve Niles, and Brett Gurewitz formed Black Mask Studios to produce transgressive works that foster a “punk sensibility” and to promote counter-culture values that are too often shunned by publishers. In one interview, Pizzolo recounts a discussion in which the creators lamented that “if V for Vendetta were created today, there would be no publisher for it” (Foxe, 2015). Other comics influenced by OWS, to a greater or lesser degree, followed.

Some mainstream titles used OWS as a way of reframing the fight for justice. For example, Marvel’s Occupy Avengers (2016) focused on community-based justice. In the story arc, Hawkeye travels around the USA to aid communities-in-need, with the first stop in New Mexico’s Sweet Medicine Indian Reservation to address their contaminated water supply. The book’s narrator states,

“When a cosmic entity threatens to destroy the world, you do something about it. Shape-shifting aliens invade your planet, you take a stand. But what do you do when the water supply of a town is contaminated? When the rights of the poor and the powerless are ignored because…well…they’re poor and powerless” (Walker & Pacheo, 2016).

Similarly, DC directly engaged with OWS rhetoric by advertising two titles that challenged readers to “Meet the 1%” (The Green Team) and “Meet the 99%” (The Movement). The Movement’s (2013) solicitation read: “Who defends the powerless against the GREEDY and the CORRUPT? Who protects the homeless and poverty-stricken from those who would PREY upon them in the DARK OF NIGHT?” (Young, 2013). The 12-issue series portrays an anarchist movement using social media to combat police brutality and corruption in a blighted neighborhood. In contrast, The Green Team (a 2013 relaunch of the original 1975 title) focuses on a group of trillionaire teens who accumulated wealth in the tech industry and use their resources to fight against equally wealthy, although selfish and greedy, villains.

Mainstream books rarely offer critiques that seriously challenge the capitalist order as publishers are overwhelmingly wedded to superhero stories whose formula relies on the consistent restoration of the social order, ad infinitum. These are not usually books of resistance and revolution. As mentioned, while the superhero narratives may tackle inequalities, the problem is resolved through apocalyptic incapacitation as opposed to meaningful economic restructuring. In these instances, social ills are depoliticized, transmogrified, and embodied by supervillains who are ultimately incapacitated, though rarely killed, in a violent showdown. When comics do buck the status quo in a meaningful way, generally they are either independent, creator-owned comics or conceived as limited, out-of-continuity runs. For example, The Flintstones (2016) captured the absurd essence of neoliberal capitalism and provided one of its sharpest rebukes. The book, by creators Mark Russell and Steve Pugh, is a powerhouse critique of rampant free-market capitalism, conspicuous consumption, rising authoritarianism, the perils of war, and a failing health care system. Moreover, the book critiques gender inequalities, animal exploitation, and failing social institutions while confronting the existential question of the meaning of life.

The book portrays economic exploitation of the working class by introducing the “Cro-Mags” who are ushered into Bedrock as low-wage laborers at the Quarry and told by Fred, “You should be proud to be working at Slate’s Quarry.” Nonetheless, after expressing that they hated “making rock,” they were paid…money.

CRO-MAG: What am I supposed to do with this?

FRED: I do not know. Buy something someone else hated making.

The resistance to labor exploitation in Bedrock may be fictional, but the issue resonates and has proven prescient, particularly considering the largest union organizing campaign in recent history undertaken among Amazon and Starbucks workers and the many who are a part of labor strikes across the country (Weise, 2021). Moreover, the labor exploitation of the Cro-Mags is set against the brutal war-torn history of the founding of Bedrock which is described in the book as “…thousands of men like you, fighting and dying, to make Bedrock safe for business.” After exposure to all that Bedrock has to offer, the boss, Mr. Slate, is shocked that the Cro-Mags are not wooed by the marvels of civilization such as food chains (i.e., the “Outback Snakehouse” and “Starbricks Coffee”) and bare-knuckle UFC-styled fights at “Madistone Square Garden” where, in the arena, the spoils are consumed by vicious pterodactyls (Issue #1).

Linking the exploits of capitalism to pain and suffering, the Cro-Mags are recruited to kill mammoths. This move resulted in the death of one of their fellow Cro-Mags and was the final straw that led to their departure.

MR. SLATE: Bedrock has so much to offer.

CRO-MAG 1: No offense, but it seems like the whole point of civilization is to get someone else to do your killing for you.

CRO-MAG 2: Yeah, I think we will pass.

It is through these conflicts and others that the book confronts socioeconomic inequalities, destabilizing the assumption that social, physical, and economic harms from capitalism are inevitable. Rather, harms are exposed as the consequence of choices made wherein the marginalized and powerless are exploited and those in power are enriched. The book exposes what and whom we are willing to exploit to sustain the illusion that the economy benefits everyone and lays bare what is sacrificed in the process. For example, in an interview with Freak Sugar, writer Mark Russell mentions why The Flintstones is an appropriate vehicle for illustrating the harms of hyper-consumerism,

“If there is one thing that I today find darkly subversive about The Flintstones, it’s the embedded commentary on consumerism. If you want a Polaroid camera, then there’s a tiny bird with a chisel that has to live inside that camera, but somehow, there’s never any question about whether or not subjecting that bird to a life of hellish slavery inside a camera is worth it. We are no less blithe when it comes to our seafood and iPhones.”

It is fairly unusual for any given monthly comic to receive media attention in outlets such as The Washington Post, Vox, and NPR, yet The Flintstones received accolades. That a book confronting the failures of neoliberal capitalism was declared a “[a] bleak, brilliant comic book” and “[t]he most politically relevant comic on the stands” among other praise, illustrates that readers are receptive to such critiques.3 Rather than dismiss headlines as inconsequential, we suggest they are indicative of readers deriving more from the book than mere appropriation of OWS rhetoric. The book taps into some of the more intense socioeconomic-political anxieties arising in contemporary society. For example, in his review, Charles Pulliam-Moore describes how the book captures the frustrations of citizens who have been failed by their leaders and deprived of the safety nets that may sustain them:

“There are the background citizens of Bedrock who, displeased with their current mayor who was unable to fulfill all of their desires for the city, turn to an incompetent strongman leader who makes promises that he could never keep. There are the veterans of the great war with the Tree People who, as Bedrock’s health system for veterans deteriorates, can’t get access to the physical and psychological therapies they need to reintegrate into society” (Pulliam-Moore, 2017).

While The Flintstones delivers a stinging critique with subversive humor, other books take a more sober approach such as Greg Rucka and Michael Lark’s ongoing series, Lazarus. The book is set in a near-future post-capitalist dystopia where concentrated wealth shapes a new global order. In this not-so-distant future, biotechnological advances extend life expectancies for the privileged few and nation-states are replaced with sixteen families who rule over the remaining “serfs” and “waste.” The book brings to stark relief what Richard Evans and Henry Giroux (2015) call the politics of disposability where violence is depoliticized and detached from ethical considerations; “Entire populations once protected by the social contract are now considered disposable, dispatched to the garbage dump of a society that equates one’s humanity exclusively with one’s ability to consume” (p. 151). In the book, the waste are beholden to the Families as coercive land-use agreements bind them to lives of crippling debt and despair. Periodically, the waste are offered a chance to “Lift” to serf status if they can demonstrate a talent or skill that will benefit the ruling Family. In the book, the careful worldbuilding (provided in the backmatter of the single issues, collected editions, and sourcebooks) gives a sense of the global territory conquered by each family, the bureaucracies and governance formed, and the technology and military utilized to maintain global domination. The world of Lazarus is an imaginary future, but it is not a world inconceivable. Various parallels between our post-OWS political and economic landscape are fairly explicit in Lazarus as Evan McGarvey, writing for the LA Review of Books, points out,

“If the brothers Koch can torque dozens of local and state elections and fund what amounts to a half-decade-long obstructionist movement in one nation, what might happen if the families Slim, Koç, Ambani, Ferrero, Bettencourt—to name several of the richest in the world—joined the Kochs, and others, and decided to flip the game board of geopolitics over?” (McGarvey, 2017).

Moreover, writer Greg Rucka is explicit about how OWS, austerity, unbridled corporate power and other authoritarian political developments inspired Lazarus. He offers the book as a warning for what happens when “capitalism supplant[s] democracy” (Johnston, 2017; Wong, 2013). Lazarus offers a futuristic imagining of how concentrated wealth in the hands of the few might reshape the world order. Within the story are signs of resistance from the marginalized; however, the narrative primarily focuses on the machinations of those in power. For now, we reside in the dystopian landscape where the only alternative to capitalism is a bleak plutocracy.

The Black Monday Murders: Feeding Mammon

If Lazarus offers us a grounded dystopian new world order illuminating how those rendered disposable are consigned to what Evans and Giroux (2015) call “zones of abandonment,” Jonathan Hickman and Tomm Coker bring our attention to the machinations of wealth and corruption in the upper echelons of society, a big lie hidden from the masses through the fiction of fair competition in capitalist society. Underneath the seemingly rational economic system is a devil-worshipping financial cabal, the subject of Hickman and Coker’s The Black Monday Murders (2017), a cross between a crime procedural and a horror story. In this tale of Wall Street corruption and a rigged economy, the economic machine is not maintaining prosperity and equality, but rather is an unsustainable, self-devouring apparatus that repeatedly takes its victims throughout history: the poor, the marginalized, and the disempowered. Like The Flintstones and Lazarus, The Black Monday Murder’s depiction of inequality and crime is a shift from historic portrayals of these social problems as inevitable and ultimately unstoppable, and exposes neoliberal capitalism itself as criminogenic.

In The Black Monday Murders, a series of seemingly independent entities are in cahoots: a secret financial cabal embedded within quasi-Christian religious institutions, a vampire cult, national governments, multinational corporations, and international intergovernmental bodies. The cabal controls the economic system through a semi-hereditary succession featuring two main families. Complicated lore underlies their traditions, such as a heritage written in a fictional Mesopotamian ancient language. The back story also draws on a post-Cold War merging of Eastern and Western systems of government, forming a global financial system that is a way of life, a religion involving devil-worship of Mammon, a practical reality of economic inequality, and a threat to human life. Intercalary musings interrupt the traditional comic book frames of action, such as procedural documents with parts redacted in thick black stripes. As one reader posted on Reddit, the documents had “implications for conspiracy” and “gives us the feeling that people in power… are trying to keep certain elements of the conversation secret or classified. It makes you wonder who else is impacted by these secret societies and how they work with different institutions of power” (Universe 2000, 2017).

The creators are playing with common themes in comics of a critical nature. Fawaz noted that demonic possession often represents the “rapacious expansion of late capitalism” in contemporary comics (Fawaz, p. 205). Black Monday Murders is yet another example of the hungry demon metaphor being applied to the economic order. The book also plays with another trope: it is a crime procedural in a larger universe of global conspiracy. Similar themes emerge in the popular series 100 Bullets, published by Vertigo Comics which ran from 1999 to 2009. There, an organization known as “The Trust” is entangled with the main character, Agent Graves, who in each issue provides victims of crime with the means and opportunity to take revenge on their perpetrators, free of consequence. The Trust is composed of the heads of 13 European families who together control most of the wealth gleaned from the “Old World” colonial experience, implying that they are the engine behind the contemporary global economic order. Although on one level the book explores the moral implications of revenge in a series of individual stories, over the course of the series Agent Graves is revealed to be on a mission to fight back against the all-powerful trust through the murderous deployment of the retaliating victims he recruits. Weaving together a crime procedural and a giant conspiracy, the plot of 100 Bullets is a “… larger social narrative, which incorporates a sprawling conspiratorial discourse on corporate power and its corrupting influence on the lives of ordinary citizens” (Nurse, 2015: 133). Through individual vigilante narratives that connect to the larger conspiracy, the series implies that seemingly individualized choices are manipulations by larger forces. Individual crimes are more akin to organized ones in the sense that they are a response to greater social factors, and therefore, require an organized response (Nurse, 2015).

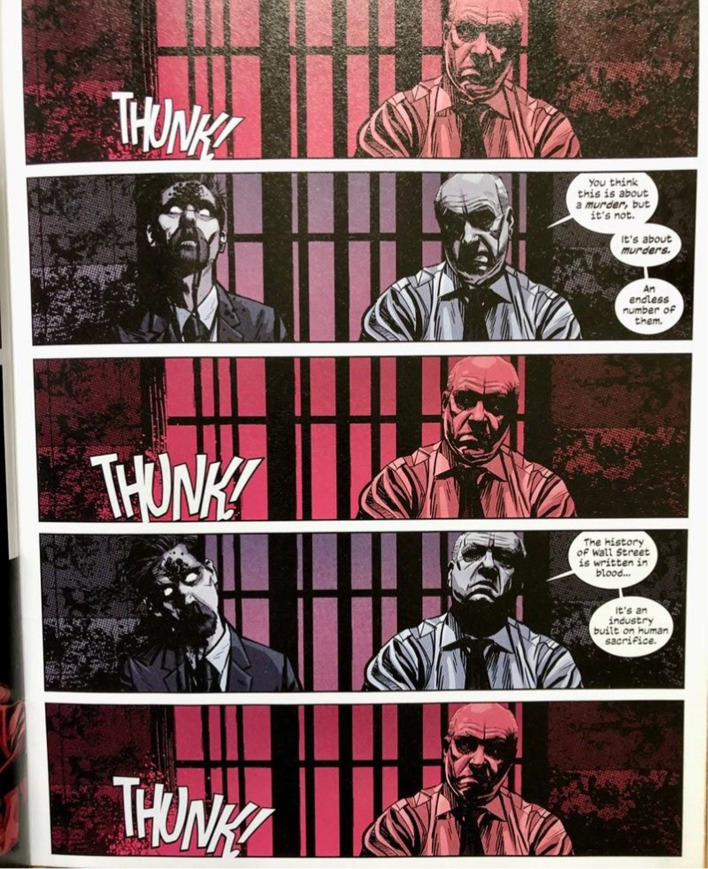

Similarly, in The Black Monday Murders, Detective Theo Dumas, while investigating one murder, uncovers the alleged truth about the homicidal economic system that is hidden to most. As Viktor Eresko, an investment banker and member of the cabal, tells the detective, “You think this is about a murder, but it’s not. It’s about murders. An endless number of them.” Dumas is one of the only people outside the conspiracy who begins to see it for what it is. Through Dumas, the book questions the fallacy of neoliberal logics as the natural order, through his questioning of perpetrators of the vast conspiracy. He surmises that the system is seemingly based on individual choice and democracy, but behind the curtain it is rigged and deadly. In Volume 2, Dumas descends into a portal of hell with an informant, Dr. Gaddis, a fringe economist who, like him, has come to know the system is rigged at the behest of the devil (Mammon) who demands blood sacrifice. Together, Dumas and Gaddis confront Mammon, the devil asking him in a dramatic, confrontational scene why he bothers with a secret cabal that controls the economy if he is all powerful. Could he not control the economy directly? Mammon replies:

I permit the [cabal] to exist because they serve my purpose. In return for my favor and the gifts that this favor yields, they work to create hunger in the masses. Scarcity gives the people appetite, and hope makes them believe they will be fed. Man is my seed and they are a true reflection of my nature. So, they worship themselves and in doing so, me. Eternal consumers (Vol. II, Chapter 7).

From the interchange with Mammon, Dumas and Gaddis learn that every Wall Street crash in history was a demonic manipulation, save one, that of 1987. An emerging mystery in the book—which is not solved in the two extant volumes—is why the 1987 crash may have been different. Regardless, like everything of value in the system, the exchange of this insider information has a price. Mammon takes his requisite blood sacrifice and uses his vampiric underlings to murder the fringe economist.

In Black Monday Murders, what plagues the economic system are not one-off white-collar crimes, but a systemic corruption implicating capitalism itself. In this way, the book operates much like cultural, critical, and realist criminologists who expand their scope of study beyond legalistic parameters designating what is “criminal” toward the identification of problematic broader social systems. Economic harms, for example, are more violent and destructive than all the officially measured street crimes, but rarely recognized as such by the public. Likewise, in The Black Monday Murders, murders functional to the rigged economic structure are never understood as such by the general public (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fringe economist Dr. Gaddis and Detective Dumas discuss the human sacrifice that the economic system takes and how people still believe it is just and fair despite evidence to the contrary (The Black Monday Murders, Issue #4)

However, the book avoids a simplistic dismissal of greed through rational choice and opportunity, which is often how these plots are handled historically in comics. Instead, as a critical text, Black Monday Murders goes deeper into the structural forces at play where wealth and prosperity itself can only be had through human sacrifice. In an early scene in the volumes, an investment banker explicitly disregards the human toll after another body has been sacrificed to the forces of Mammon. He says, “Well, I don’t give a damn if [people] drown in it. All that matters is this institution, and that we are made whole.” In his review of the book, David Allison explains,

“One of the interesting aspects of modern currency, which the world economy was forced to reckon with in the 20th century, is that capital growth eventually exceeds the ability of mineral deposits to back it. The Black Monday Murders acknowledges this, stating that real wealth is “pulled from the earth.” What’s more, as Dr. Gaddis cites the use of slaves in expropriating of silver from South America by Spanish colonialists, we see that this mineral wealth can also be expressed as the human cost in extracting it.”

The explicit positioning of what this accumulated wealth costs in terms of human lives is what makes The Black Monday Murders stand in contrast to other mainstream comic portrayals of economic inequality (see Fig. 2). The god of Mammon describes this economic “deal with the devil”:

DR. GADDIS: What causes a market crash?

MAMMON: …when I wake I hunger, and when I hunger I consume… the market reacts as I eat—the scales become unbalanced—and a correction must be achieved. So, man pays until my hunger subsides (Issue #7).

Fig. 2.

Operative in the secret cabal, Victor Eresko, spontaneously murders his own defense attorney using mind control, in order to show Detective Dumas the magical and demonic power manifest in the cabal (The Black Monday Murders, Issue #3)

Similarly, in the discourse around the coronavirus pandemic, the exchange of lives of the elderly and other at-risk individuals in order to ensure the functioning of the economy is viewed as an acceptable trade-off (Barber et al., 2020; Hume, 2020). Meanwhile, those critical of the economic trade-off wondered whether the pandemic unveiled the existing inequalities and underlying logic of privileging capitalism to benefit the elite over human lives in general. Some Twitter users, under #socialmurder, circulated a meme calling out sacrificing lives for the economy, labeling “social murder” as “…coined by Frederich Engels in 1845 and used to describe murder committed by the social and political elite when they knowingly permit conditions that threaten life” (Beth, 2020).

In the coronavirus pandemic, the protocols of global capitalism were interrupted and the violent nature of global capitalism seemed more apparent. Some Twitter users wondered whether going back to low-paying jobs in unsafe conditions was worth it given that profits from this labor are disproportionately flowing to the economic elite. Another intimated that if average people realized how rigged against them the economic system is both financially and even physically, they may not go back to work as usual. “Some of us won’t want to go back and play by their rules” (Rebekah West, 2020).

Both the coronavirus pandemic and The Black Monday Murders illuminate how neoliberal logics function to uphold systems and perpetuate inequalities. As mentioned, market crashes are explained as a balancing of the status quo—a flow of capital to and among the elite—and perceived as natural and inevitable (see Fig. 3). The big lie of inevitability obfuscates power dynamics at play and the deeper truths of the costs of maintaining economic inequalities. Some, such as Dr. Gaddis, recognize that this is a truth that few are willing to hear. Dr. Gaddis asks Det. Dumas, “If we understand it, do we have the will to act on it?”

Fig. 3.

The Matriarch of the quasi-Christian denomination, serving as the spiritual foundation of the secret economic cabal, delivers a sermon at the death of an elite member in front of representatives of its cooperating entities (The Black Monday Murders, Issue #4)

The challenge posed by The Black Monday Murders is an existential one: who do you serve? Those who benefit must be morally comfortable taking human lives, vampirically consuming others, and in the comic book gain even more power by devouring their own family members. The protagonist detective fights the supernatural and, without spoiling, reveals the perpetrator to be a member of the cabal. The twist is that even as justice is pursued, there remains a seduction impossible to resist. Economic inequality remains a product of supernatural forces and knowledge is not power. Rather, it creates the desire for corruption and leaves even those pursuing justice to claim “I want in,” as Detective Dumas does in the end of Volume 2. The resulting tension where the story leaves off is whether Dumas is indeed corrupted, as it appears on the surface, or if his statement acts as a ruse so he can potentially investigate the homicidal cabal from the inside.

Limitations

It is our hope that our analysis provides a starting point for considering how narratives challenging economic inequalities flow through comic books and, moreover, how those narratives provide a critical criminological lens for recognizing the harms of neoliberal capitalism as criminogenic; a political-economic social reality that is neither natural nor inevitable. We acknowledge our analysis is a purposive sample limited to comics published in the USA. As a result, we have left unexplored comics published in the UK, France, Scandinavia, and the widely influential manga out of Japan. Future research may put forward a comparative analysis that more directly investigates narratives of global socioeconomic inequalities.

Conclusion

We suggest that mainstream comic books are an important cultural resource for sustaining and potentially resisting the logics of neoliberal capitalism. Although readership of these books is declining, many of the plots and storylines are picked up by the film industry and resonate loudly in that medium. Using a critical criminological lens, we show that narratives of socioeconomic inequalities have long been present in comics. We also recognize that the OWS movement created an opening for creators to portray a direct link between the machinations of neoliberal capitalism and human suffering and death. These critiques exist along a spectrum; a range we highlighted from books such as The Flintstones, Lazarus, and The Black Monday Murders that are worlds apart in terms of tone and genre but commensurate in conveying the harms of unbridled capitalism.

We have drawn links between themes in various books and the Marxist perspective, which point to the unjust structures of capitalism as criminogenic and exploitative. These themes are seen in the labor exploitation, lack of social services, and rising authoritarianism portrayed in The Flintstones and in the eradication of democracy through consolidation of money and power in Lazarus. Similarly, we see the seductive potential for sustaining the economy at all costs in The Black Monday Murders which brings to relief Bonger’s notion of economic egoistic acts as criminogenic. These fictional narratives positioning neoliberal capitalism as a direct cause of suffering and death have resonated in the political climate during the pandemic.

Lurking within mainstream American political narratives is the implicit valuing of money over lives. This is explicit in discourse about reopening the economy during the coronavirus pandemic that, at least during the last year of the Trump administration, prioritized productivity over protecting human lives. Privileging the economy over lives echoes as a rallying cry by constituents demanding “liberation” after quarantine. In The Black Monday Murders, it is not the coronavirus but Mammon who must be fed for the economy, and elites gain power through being the ones feeding the beast. In a post-pandemic world to come, as the comic book industry struggles to survive, we hope mainstream creators will continue to be propelled in a critical criminological direction, building on the response to OWS, daring to question the capitalist system and the sacrifices people make for it.

Footnotes

Although a third volume was originally planned for the series, the series’ artist Tomm Coker had health issues which delayed the completion of the work. Arrant, Chris (2019, April 24). “Tomm Coker's health concerns leads to The Black Monday Murders hiatus” Retrieved April 8, 2020 at https://www.newsarama.com/44921-tomm-coker-s-health-concerns-leads-to-black-monday-murders-hiatus.html]

Here, the etiological crisis refers to theoretical and methodological deficiencies that prevent criminologists from adequately understanding and explaining the most significant social facts about crime such as the crime drop in the late 1990s (Matthews, 2016).

https://www.dailydot.com/parsec/dc-flintstones-comic-reboot-2016/; https://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2017/03/29/the-flintstones-comic-is-surprisingly-deep-and-people-are-shoo_a_22018057/; https://www.ign.com/articles/2017/03/29/how-dcs-flintstones-became-the-most-politically-relevant-comic-on-the-stands; https://www.gq.com/story/the-flintstones-woke-comic-book; https://slate.com/culture/2017/04/mark-russell-and-steve-pughs-comic-book-reboot-of-the-flintstones-reviewed.html; https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/comic-riffs/wp/2016/06/28/yabba-dabba-reboot-satire-is-sharp-enough-to-cut-rocks-in-dc-comics-debut-of-the-flintstones/; https://www.vox.com/culture/2017/3/22/15000062/flintstones-comic-interview-russell-pugh.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nickie D. Phillips, Email: nphillips@sfc.edu

Staci Strobl, Email: sstrobl@su.edu.

References

- Alvaredo, F., Chancel, L., Piketty, T., Saez, E. & Zucman G. (2017, December 14). Inequality is not inevitable—but the US 'experiment' is a recipe for divergence. Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/dec/14/inequality-is-not-inevitable-but-the-us-experiment-is-a-recipe-for-divergence. Accessed 2 June 2020.

- Barber, W., Case, A., Zeke, E., Gupta, V., Singer, P., & Bazelon, E. (2020, April 10). Restarting America Means People Will Die. So When Do We Do It? New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/10/magazine/coronavirus-economy-debate.html. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Bates T. Gramsci and the Theory of Hegemony. Journal of the History of Ideas. 1975;36(2):351–366. doi: 10.2307/2708933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beth L. [@mjbethel]. (2020, April 15). Meme entitled “Social Murder” replying to @ndrew_lawrence in thread: https://twitter.com/ndrew_lawrence/status/1250582792972484610?s=20

- Blumberg, Y. (2018, August 28). 70% of Americans now support Medicare-for-all—here’s how single-payer could affect you. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/08/28/most-americans-now-support-medicare-for-all-and-free-college-tuition.html. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Blythe M. Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bonger W. Criminality and Economic Conditions. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Booker, K.M. (2014). Capitalism and Corporations. In Booker, K.M. (ed.), Comics through time: A history of icons, idols and ideas (pp. 501–504). Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

- Brody RG, Kiehl KA. From white-collar crime to red-collar crime. Journal of Financial Crime. 2010;17(3):351–364. doi: 10.1108/13590791011056318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. (2020, April 22). Texas Lt. Gov Dan Patrick: ‘There are more important things than living’ during pandemic. NY Post. https://nypost.com/2020/04/22/lt-gov-dan-patrick-there-are-more-important-things-than-living/. Accessed 22 April 2020.

- Casselman, B. and P Cohen (2020, April 2). A widening toll on jobs: ‘This thing is going to come for us all’. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/02/business/economy/coronavirus-unemployment-claims.html. Accessed 2 April 2020.

- Cocca, C. (2016). Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Evans B, Giroux H. Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of Spectacle. San Francisco, CA: City Lights Publishers; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fawaz R. The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics. New York, NY: NYU Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M. Capitalist Realism: Is there no alternative? Winchester, UK: Zero Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, M. (2018). K-Punk. London, UK: Repeater.

- Foxe, S. (2015). Black Mask Studios Founders Talk Creator Rights, Punk Ethics and a Very Busy 2015. Paste. https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2015/03/black-mask-studios-founders-talk-creator-rights-pu.html. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Fukuyama F. The End of History and the Last Man. New York, NY: The Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk M. The Prison and the Gallows. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, A., Rosenthal, S., Leiserwitz, A., J. Maibach, E., Kotcher, Ballew, M., & Goldberg, M. (2018, December 14). The Green New Deal has Strong Bipartisan Support. Yale Program on Climate Communication. http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/publications/the-green-new-deal-has-strong-bipartisan-support/. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Hall S. Theorizing Crime and Deviance: A New Perspective. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hall S, Winlow S. Revitalizing Criminology Theory: Towards a new ultra-realism. London, UK: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harcourt B. The illusion of free markets: Punishment and the myth of the natural order. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 1–256. [Google Scholar]

- Hume, B. (2020, March 25). Fox News' Brit Hume Defends Risking Older People's Lives 'To Allow The Economy To Move Forward' In Coronavirus Shutdown. Newsweek.https://www.thewrap.com/brit-hume-entirely-reasonable-elderly-would-want-to-die-to-save-economy-amid-coronavirus/. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Jacques, M. (2016, August 21). The death of neoliberalism and the crisis in western politics. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/aug/21/death-of-neoliberalism-crisis-in-western-politics. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Joe the Voter. [@JoetheVoter]. (2030, March 27). PLEASE #America if your own lives and lives of family and friends matter DO NOT listen to a word that comes from #Trump, @whitehouse or his appointed liars. They would bury own grandmother for a buck. #coronavirus #COVID19 #BlueWave2020 #MAGA [Tweet]. https://twitter.com/HassanRouhani/status/385138174822850560. Accessed 22 April 2020.

- Johnston, R. (2017, April 4). Greg Rucka And Michael Lark Launch X+66, A New Lazarus Mini-Series Starting In July From Image Comics. Bleeding Cool. https://www.bleedingcool.com/2017/04/04/greg-rucka-michael-lark-launch-new-lazarus-mini-series-starting-july-x66-image-comics/. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Kauzlarich D. & Rothe D.L. (2014) Crimes of the powerful. In: Bruinsma G., Weisburd D. (eds) Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice.New York, NY: Springer.

- Keith, J. (2016, July 12). Recapturing The Magic: Mark Russell On The Flintstone. http://www.freaksugar.com/mark-russell-the-flintstones-interview/. Accessed April 2, 2019.

- König, M. & A. Winkler (2021). COVID-19: lockdowns, fatality rates and GDP growth. Intereconomics: Review of European Economic Policy, 56(1): 32–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kotz D. The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism. 2. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kotzé J. The Myth of the “Crime Decline”: Exploring Change and Continuity in Crime and Harm. London, UK: Routledge; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Levi M. The media constructions of financial white-collar crime. British Journal of Criminology. 2006;46:1037–1057. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azl079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levitz, E. (2020, March 28). Trump can’t save the economy by letting coronavirus run wild. New York Magazine. https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2020/03/trump-coronavirus-economy-recession-social-distancing.html. Accessed 02 April 2020.

- Matthews R. Realist Criminology. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews R. Realist criminology, the new aetiological crisis and the crime drop. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy. 2016;5(3):2–11. doi: 10.5204/ijcjsd.v5i3.343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister M, Sewell E, Jr, Gordon I. Comics and Ideology. New York, NY: Peter Lang; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey, E. (2017). Cogs of War: “Lazarus” and the Limits of Dystopia. LA Review of Books.https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/cogs-of-war-lazarus-and-the-limits-of-dystopia/#!. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Merle, R. (2018). A guide to the financial crisis — 10 years later. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/a-guide-to-the-financial-crisis--10-years-later/2018/09/10/114b76ba-af10-11e8-a20b-5f4f84429666_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.165bf29ad344. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Nama A. Super Black: American Pop Culture and Black Superheroes. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health (NIH; 2021, March 11). Opioid Overdose Crisis. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis. Accessed 29 April 2021.

- Nurse, A. (2015). Extreme restorative justice: the politics of vigilantism in Vertigo’s 100 Bullets. In Thomas Giddens (Ed.), Graphic Justice. Intersections of Comics and Law (p. 130–146). New York: Routledge.

- O’Neill, D. and N. Adams (1976- 1977). Green Arrow/Green Lantern. New York: DC Comics.

- Passas N. Lawful but awful: ‘Legal Corporate Crimes’. Journal of Socio-Economics. 2005;34(6):771–786. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2005.07.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patience, A. (2017, February 5). If we are reaching neoliberal capitalism’s end days, what comes next. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/if-we-are-reaching-neoliberal-capitalisms-end-days-what-comes-next-72366. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Perri FS. White-collar criminals: the ‘kinder, gentler’offender? Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling. 2011;8(3):217–241. doi: 10.1002/jip.140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew. (2010). The Impact of the September 2008 Economic Collapse. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2010/04/28/the-impact-of-the-september-2008-economic-collapse. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Phillips ND, Strobl S. Comic Book Crime: Truth, Justice, and the American Way. New York, NY: NYU Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pramuk, J. (2020, March 27). Trump signs $2 trillion coronavirus relief bill as the US tries to prevent economic devastation. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/27/house-passes-2-trillion-coronavirus-stimulus-bill-sends-it-to-trump.html. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Pulliam-Moore, C. (2017, June 8). The Flintstones Comic Is a Darkly Funny Story About the Perils of Late Stage Capitalism. Gizmodo. https://io9.gizmodo.com/the-flintstones-comic-is-a-darkly-funny-story-about-the-1795933097. Accessed April 2, 2019.

- Quinney R. Class, State and Crime: Theory and Practice in Criminal Justice. Philadelphia: D. McKay Co; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Rebekah West [@rebequewest]. (2020, April 15). And the longer we are at home figuring out how to live differently... Replying to @ndrew_lawrence in thread: https://twitter.com/ndrew_lawrence/status/1250582792972484610?s=20

- Reiman J, Leighton P. The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Prison: Ideology, Class, and Criminal Justice. 11. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner, R. (2007). Media-made criminality: The representations of crime in the mass media. In M. Maguie, R. Morgam & R. Reiner, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Criminology, 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rothe D, Kauzlarich D. Crimes of the Powerful: An introduction. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rushe, D. & Chalabi, M. (2020, April 26). 'Heads we win, tails you lose': how America's rich have turned pandemic into profit. Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/26/heads-we-win-tails-you-lose-how-americas-rich-have-turned-pandemic-into-profit?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other. Accessed 26 April 2020.

- Rushkoff, D. (2020, March 25). We wish to inform you that your death is highly profitable. Medium.com. https://gen.medium.com/we-wish-to-inform-you-that-your-death-is-highly-profitable-22c73744055c. Accessed 2 April 2020.

- Schecter, D. (2010, April 23). The Financial Crisis as Crime Story. The Nation. Available: https://www.thenation.com/article/financial-crisis-crime-story/. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Sheffield, M. (2019, January 24). Poll: Majority of voters support $15 minimum wage. The Hill. https://thehill.com/hilltv/what-americas-thinking/426780-poll-a-majority-of-voters-want-a-15-minimum-wage. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Silverstein, J. (2020, May 5). Chris Chritie argues for reopening the economy because ‘there are going to be deaths no matter what.’ CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/chris-christie-reopening-economy-deaths-no-matter-what/. Accessed 29 April 2021.

- Solis, M. (2020, March 13). Coronavirus Is the Perfect Disaster for ‘Disaster Capitalism’. Vice. https://www.vice.com/amp/en_us/article/5dmqyk/naomi-klein-interview-on-coronavirus-and-disaster-capitalism-shock-doctrine?__twitter_impression=true. Accessed 22 April 2020.

- Spinney, L. (2021, February 14). Has Covid Changed the Price of Life? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/14/coronavirus-covid-19-cost-price-life. Accessed 29 April 2021.

- Stichman A. Bonger, Willem: Capitalism and Crime. In: Cullen Francis T, Wilcox Pamela., editors. Encyclopedia of Criminological Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2010. pp. 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Sunkara B. The Socialist Manifesto: The Case for Radical Politics in an Era of Extreme Inequality. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tankersley, J., Haberman, M. & R. Caryn R. (2020, March 23). Trump considers reopening economy, over health experts’ objections. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/business/trump-coronavirus-economy.html Accessed 2 April 2020.

- Tappe, A. (2020, May 28). 1 in 4 American workers have filed for unemployment benefits during the pandemic. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/28/economy/unemployment-benefits-coronavirus/index.html. Accessed 29 May 2020.

- The Economist. (2020, March 28). A $2 trillion bazooka. The Economist, pp. 21–22.

- The White House. (2020, March 31). 30 Days to Slow the Spread. At https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/03.16.20_coronavirus-guidance_8.5x11_315PM.pdf. Accessed 2 April 2020.

- Universe 2000 (2017). “The language doesn’t get explained…” Black Monday Murders Reddit thread. Retrieved on March 23, 2019 from www.reddit.com [since removed].

- Wacquant L. Punishing the Poor. Durham: Duke University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, D. & Pacheo, C. (2016). Occupy Avengers. Issue 1. Marvel Comics.

- Weinstein S. Up up and oy vey! How Jewish History, Culture, and Values Shaped the Comic Book Superhero. Fort Lee, NJ: Barricade Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Weise, K. (2021, March 17). The Amazon Unionization Vote: What to Know. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/17/technology/amazon-union-vote.html. Accessed 18 March 2021.

- White, R. (2017). Neoliberalism. In A. Brisman, E. Carrabine, & N. South (Eds.), Routledge Companion to Criminological Theory and Concepts. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Wilson E. Criminogenic Cyber-Capitalism: Paul Virilio, Simulation, and the Global Financial Crisis. Critical Criminology. 2012;20:249–274. doi: 10.1007/s10612-011-9139-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winlow S, Hall S. Shock and Awe: On Progressive Minimalism and Retreatism, and the New Ultra-Realism. Critical Criminology. 2019;27:21–36. doi: 10.1007/s10612-019-09431-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P. (2013, June 25). Interview With “Lazarus” Writer Greg Rucka. BeyondChron. http://beyondchron.org/interview-with-lazarus-writer-greg-rucka/. Accessed 02 June 2020.

- Wright, B. W. (2003). Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Xenakis S, Cheliotis LK. Whither neoliberal penality? The past, present and future of imprisonment in the US. Punishment & Society. 2018 doi: 10.1177/1462474517751911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young J. Criminological Imagination. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Young, B. (2013, February 7). Interview: Gail Simone on "The Movement.” Available: http://www.bigshinyrobot.com/48540/interview-gail-simone-on-the-movement/. Accessed 02 June 2020.