Abstract

Purpose

Although there is evidence supporting the benefits of corticosteroids in patients affected with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), there is little information related to their potential benefits or harm in some subgroups of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with COVID-19. We aim to investigate to find candidate variables to guide personalized treatment with steroids in critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Methods

Multicentre, observational cohort study including consecutive COVID-19 patients admitted to 55 Spanish ICUs. The primary outcome was 90-day mortality. Subsequent analyses in clinically relevant subgroups by age, ICU baseline illness severity, organ damage, laboratory findings and mechanical ventilation were performed. High doses of corticosteroids (≥ 12 mg/day equivalent dexamethasone dose), early administration of corticosteroid treatment (< 7 days since symptom onset) and long term of corticosteroids (≥ 10 days) were also investigated.

Results

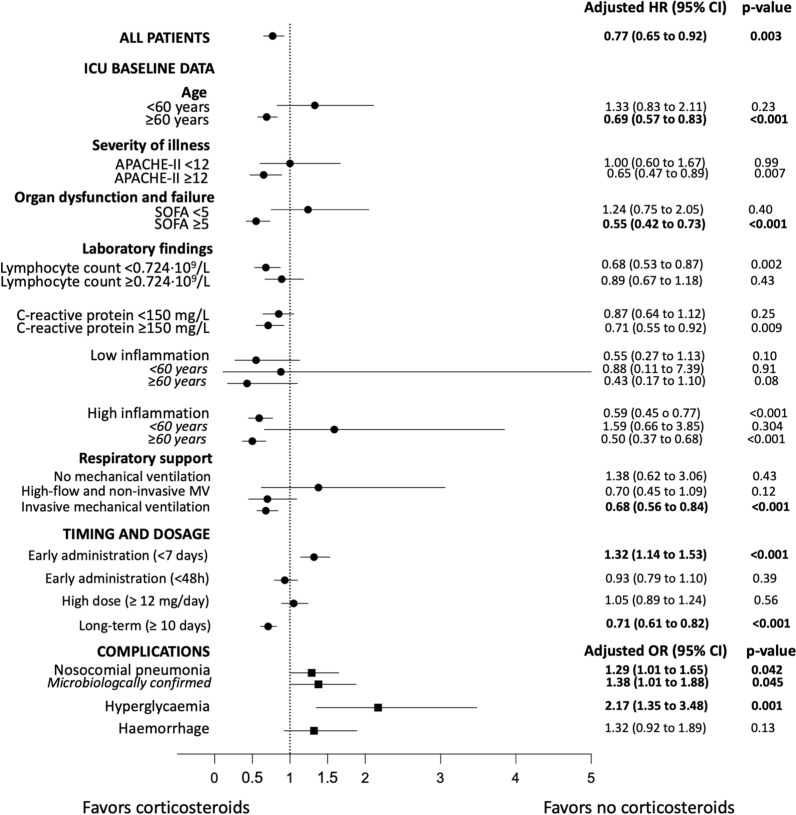

Between February 2020 and October 2021, 4226 patients were included. Of these, 3592 (85%) patients had received systemic corticosteroids during hospitalisation. In the propensity-adjusted multivariable analysis, the use of corticosteroids was protective for 90-day mortality in the overall population (HR 0.77 [0.65–0.92], p = 0.003) and in-hospital mortality (SHR 0.70 [0.58–0.84], p < 0.001). Significant effect modification was found after adjustment for covariates using propensity score for age (p = 0.001 interaction term), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (p = 0.014 interaction term), and mechanical ventilation (p = 0.001 interaction term). We observed a beneficial effect of corticosteroids on 90-day mortality in various patient subgroups, including those patients aged ≥ 60 years; those with higher baseline severity; and those receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at ICU admission. Early administration was associated with a higher risk of 90-day mortality in the overall population (HR 1.32 [1.14–1.53], p < 0.001). Long-term use was associated with a lower risk of 90-day mortality in the overall population (HR 0.71 [0.61–0.82], p < 0.001). No effect was found regarding the dosage of corticosteroids. Moreover, the use of corticosteroids was associated with an increased risk of nosocomial bacterial pneumonia and hyperglycaemia.

Conclusion

Corticosteroid in ICU-admitted patients with COVID-19 may be administered based on age, severity, baseline inflammation, and invasive mechanical ventilation. Early administration since symptom onset may prove harmful.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00134-022-06726-w.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, COVID-19, Critically ill, Intensive care

Take-home message

| Clinicians should consider age, baseline disease severity, mechanical ventilation requirement and days from symptom onset before administering corticosteroids. 90-day mortality increases when corticosteroids are administered to patients within 7 days of symptom onset, while duration of treatment for more than 10 days was associated with lower mortality. |

Introduction

In patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) admitted to intensive care units (ICU), especially in those requiring mechanical ventilation, mortality remains unacceptably high (30–60%) [1]. This statement held particularly true when only supportive treatment was available for patients during the initial waves of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Corticosteroids at reasonably low dosages and for short duration appear to decrease mortality in both severe community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) [2] and moderate-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [3, 4]. However, this type of medication could be harmful in severe influenza pneumonia [5]. For that reason, and at the beginning of the pandemic, experts did not recommend or were against use of such medication in patients with COVID-19 [6]. Despite these initial recommendations, though, and due to the dimension of the health crisis, clinicians resorted to administering corticosteroids in cases of disease progression.

The Recovery trial [7] demonstrated that administering dexamethasone versus usual standard of care decreased mortality in patients with COVID-19 requiring oxygen therapy, with or without mechanical ventilation. A subsequent meta-analysis from the World Health Organisation (WHO) [8] confirmed the Recovery trial findings. Recent European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines [9] recommended the use of corticosteroids only for patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure requiring oxygen administration. However, clinicians extended the use of corticosteroids to other patients with COVID-19—irrespective of hospitalisation status—especially in those with persistent signs and symptoms.

Despite evidence that supports the benefits of corticosteroids, retrospective/prospective studies have described a lack thereof in some patient subgroups. One study, for instance, reported increased mortality in patients aged > 80 years [10]. Another multicentre study in France [11] including ICU-admitted patients found elevated mortality in patients aged < 60 years without any increase in inflammation markers, [i.e., d-dimer, ferritin or C-reactive protein (C-RP)]. There is a general concern that corticosteroids might be harmful or ineffective in some COVID-19 phenotypes of patients.

The primary aim of this study was to assess in critically ill COVID-19 patients the effect of corticosteroid treatment on 90-day mortality in the overall population.

Methods

Study design and patients

We retrospectively analysed patients from the CIBERESUCICOVID study (NCT04457505), which had prospectively included patients aged ≥ 18 years with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection from across 55 Spanish hospitals between 5 February 2020 and 7 October 2021 (Online Table 1). All consecutive patients admitted to ICU were enrolled if reason for admission was COVID-19. Exclusion criteria for patients included the following: (1) unconfirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection; (2) lack of data at baseline or hospital discharge; (3) lack of information about corticosteroid treatment; (4) prior treatment with systemic steroids; (5) patient transfer from another ICU; and (6) ICU admission due to other reasons.

The study received approval by the Institution’s Internal Review Board (Comité Ètic d’Investigació Clínica, registry number HCB/2020/0370). Local researchers maintained contact with a study team member, and participating hospitals obtained local ethics committee approval. We reported results in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [12].

Data collection

We recorded data on demographics, comorbidities and previous treatment. Standard laboratory and clinical data were collected at hospital and ICU admission. The pharmacologic treatments administered, and interventions performed during hospital admission until either discharge from hospital or death were also collected. Importantly, corticosteroids treatment data was reported, including higher dose not pulse therapy administered, start date and duration of treatment. Main complications during hospital stay, including pulmonary complications, hyperglycaemia, nosocomial infections, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute kidney injury and acute hepatic failure, were reported.

Primary and secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses and definitions

For this study, we compared the following two groups: patients receiving corticosteroids versus those who did not. The primary outcome was all-cause 90-day mortality. Secondary outcomes included in-hospital mortality, length of ICU and hospital stay, and ventilator-free days. We examined this main outcome according to the following categories: (1) overall population; (2) several patient subgroups based on baseline data at ICU admission: age, illness severity and organ damage [Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE-II) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores using median values cut-off, respectively], laboratory findings (lymphocyte count, C-RP and inflammation), and mechanical ventilation; (3) by administration timing; (4) by dosage; and (5) by duration.

Length of ICU and hospital stay was calculated from ICU admission and hospitalisation, respectively. Ventilator- and ICU-free days at 28 days were calculated as mentioned elsewhere [13].

High inflammatory status was defined as the fulfilment of at least two of the following criteria, as described elsewhere [11]: ferritin of > 1000 µg/L; d-dimer of > 1000 µg/L; and C-RP of > 100 mg/L. As per prior studies done on severe CAP, we also looked at C-RP when ≥ 150 mg/L and lymphocyte count when < 0.724 × 109/L [14, 15].

Early administration since symptom onset of corticosteroid therapy was defined as corticosteroids administered for the first time within 7 days of symptom onset, while early administration since ICU admission was defined as corticosteroids administered for the first time within the initial 48 h of ICU admission. Patients received high-dose corticosteroids when dexamethasone or equivalent was equal or more than 12 mg/day [16], similar also to guidelines recommendation from Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) [17]. The long-term duration was equal or more than 10 days [7].

We also explored the potential association between complication onset and corticosteroid use and duration of treatment. Nosocomial bacterial pneumonia was defined according to international guidelines [18]. Microbiologically confirmed nosocomial pneumonia was defined clinically or radiologically diagnosed bacterial pneumonia managed with antimicrobials with positive culture of pathogenic germs in respiratory secretions samples. Hyperglycaemia was defined as a consistent blood glucose level above 126 mg/dL. Haemorrhage referred to any type of clinically significant bleeding. Further details are reported in a previous publication [19].

Statistical analysis

We reported the number and percentage of patients as categorical variables, and the median (first quartile [Q1]; third quartile [Q3]) as continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, whereas continuous variables were compared using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test.

We first assessed differences in 90-day mortality between groups (i.e. corticosteroid treatment vs. no treatment) using the Kaplan–Meier method (Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test [20]). To evaluate the effect of corticosteroids on 90-day mortality, we then used Cox regression models [21] stratified on the centre variable tested in univariable and multivariable analyses. The multivariable models included the following variables based on clinical relevance only: age, sex, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, chronic heart disease, chronic lung disease, chronic renal failure, immunosuppression, APACHE-II score at ICU admission, PaO2/FiO2 ratio at ICU admission, pH at ICU admission, haemoglobin at ICU admission, lymphocyte count at ICU admission, platelet count at ICU admission, d-dimer at ICU admission, C-RP at ICU admission, serum creatinine at ICU admission, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at ICU admission, ferritin at ICU admission, mechanical ventilation at ICU admission, septic shock at ICU admission, disseminated intravascular coagulation at ICU admission, tocilizumab administration and COVID-19 wave. Hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Proportional hazards assumptions were tested with log minus log plots. Patients who were transferred to another hospital were censored in survival analyses.

A propensity score [22, 23] for corticosteroid use was developed, given that corticosteroid therapy was not randomly administered to these patients and could result in a potential confounding factor and selection bias. The propensity score was determined, irrespective of outcome, with a multivariable logistic regression to predict the influence of 15 predetermined variables on the use of corticosteroids [24]. Variables were chosen for inclusion in the propensity score calculation according to methods set forth by Brookhart et al. [25], comprising variables associated with corticosteroid use and outcome (age, sex, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, chronic heart disease, chronic lung disease, chronic renal failure, immunosuppression, APACHE-II score at ICU admission, PaO2/FiO2 ratio at ICU admission, pH at ICU admission, mechanical ventilation at ICU admission, septic shock at ICU admission and disseminated intravascular coagulation at ICU admission). The score was finally entered as a continuous variable in the survival analysis for 90-day mortality.

Effect modification by factors potentially associated with patient outcomes and corticosteroid use were assessed by an interaction term, and similar analyses were carried out for subgroup analyses of these factors.

We also constructed propensity scores for patients receiving corticosteroids to examine the relationship between (1) early administration of corticosteroid therapy since symptom onset, (2) early administration of corticosteroid therapy since ICU admission, (3) high-dose corticosteroids, (4) long-term of corticosteroids, and the likelihood of 90-day mortality. The scores were created using logistic regression models and later included in the survival analyses.

We also analysed the association between corticosteroid therapy and the following variables: in-hospital mortality (by means of a Fine-Gray competing risks model [26, 27] stratified on the centre variable); length of ICU and hospital stay, and ventilator-free days (by means of generalised estimating equations [28], considering a Gaussian distribution and accounting for the effect raised by the clustering of patients from the same centre); and complication onset, such as nosocomial bacterial pneumonia, hyperglycaemia and haemorrhage (by means of generalised estimating equations [28], considering a binomial distribution and accounting for the effect raised by the clustering of patients from the same centre). Subdistribution hazard ratios (SHRs), odds ratios (ORs), beta coefficients (βs), and their 95% CIs were calculated where appropriate.

We used the multiple imputation method [29] for missing data in both the covariates of the propensity score models and multivariable analyses (Online Table 2).

The level of significance was set at 0.05 (two-tailed). No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Between 5 February 2020 and 7 October 2021, 5745 patients with COVID-19 were admitted to 55 ICUs. We included 4226 patients in this analysis, of whom 3592 (85%) received systemic corticosteroids at either hospital admission or during hospitalisation (Online Fig. 1 and Online Table 3).

Demographics and characteristics

Table 1 shows patient characteristics at ICU admission. The median body mass index was higher in those patients receiving corticosteroids (27.8 [25.6; 31.5] vs. 29 [26.1; 32.4] kg/m2; p < 0.001). Time from initial symptoms to ICU admission was also higher in the corticosteroid group (8 [6; 11] vs. 9 [7; 12] days; p < 0.001). Treatments before ICU admission differed between groups, with higher proportions of statin in patients receiving systemic corticosteroids. Although the median SOFA score did not vary between groups, the proportion of patients with a SOFA score ≥ 5 was lower in the corticosteroid group (204 [56%] vs. 1150 [49%]; p = 0.021) than in patients not receiving corticosteroids. When compared with patients without corticosteroid treatment at day 1 in ICU, patients receiving corticosteroids had a lower temperature, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, lymphocyte count and C-RP levels yet overall higher respiratory rate, pH, haemoglobin, and leukocyte, neutrophil and platelet counts. Corticosteroid treatment related data are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Variables | No treatment (N = 634) |

Corticosteroid treatment (N = 3592) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (Q1; Q3), years | 63 (51; 72) | 63 (54; 71) | 0.613 |

| Age ≥ 60 years, n (%) | 382 (60) | 2233 (62) | 0.360 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 442 (70) | 2534 (71) | 0.712 |

| BMI, median (Q1; Q3), kg/m2 | 27.8 (25.6; 31.5) | 29.0 (26.1; 32.4) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, n (%) | 0.033 | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2) | 0 (0) | 8 (0.3) | 0.368 |

| Normal weight (≥ 18.5 to < 25 kg/m2) | 116 (21) | 518 (16) | 0.079 |

| Pre-obese (≥ 25 to < 30 kg/m2) | 252 (45) | 1342 (43) | 0.201 |

| Obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) | 188 (34) | 1286 (41) | 0.013 |

| Comorbidities, n (%)a | 264 (42) | 1585 (44) | 0.245 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 144 (23) | 890 (25) | 0.265 |

| Chronic liver disease | 24 (4) | 104 (3) | 0.228 |

| Chronic heart disease | 81 (13) | 437 (12) | 0.646 |

| Chronic lung disease | 80 (13) | 508 (14) | 0.320 |

| Chronic renal failure | 40 (6) | 213 (6) | 0.712 |

| Immunosuppression | 7 (1) | 85 (2) | 0.045 |

| Days since initial symptoms to ICU admission, median (Q1; Q3) | 8 (6; 11) | 9 (7; 12) | < 0.001 |

| Treatment before admission, n (%) | |||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 107 (38) | 706 (40) | 0.620 |

| Statin | 165 (26) | 1135 (32) | 0.006 |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug | 66 (11) | 432 (12) | 0.278 |

| Characteristics at ICU admission | |||

| Glasgow Coma Scale, median (Q1; Q3) | 15 (15; 15) | 15 (15; 15) | 0.184 |

| APACHE-II score, median (Q1; Q3) | 11 (8; 16) | 12 (9; 15) | 0.505 |

| APACHE-II score ≥ 12, n (%) | 169 (50) | 941 (50) | 0.920 |

| SOFA score, median (Q1; Q3) | 5 (3; 7) | 4 (4; 7) | 0.319 |

| SOFA score ≥ 5, n (%) | 204 (56) | 1150 (49) | 0.021 |

| SOFA hemodynamic component, median (Q1; Q3) | 0 (0; 4) | 0 (0; 4) | < 0.001 |

| SOFA renal component, median (Q1; Q3) | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | 0.394 |

| Temperature, median (Q1; Q3), °C | 37.1 (36.3; 38) | 36.8 (36; 37.5) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate, median (Q1; Q3), bpm | 25 (20; 30) | 26 (22; 32) | < 0.001 |

| Arterial blood gases at ICU admission | |||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio, median (Q1; Q3) | 127 (86; 184) | 107 (78; 156) | < 0.001 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio in ventilated patients, median (Q1; Q3) | 123 (83; 178) | 107 (78; 153) | < 0.001 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio categories in ventilated patients, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Severe (< 100) | 152 (36) | 1221 (45) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate (≥ 100 to < 200) | 181 (43) | 1113 (41) | 0.502 |

| Mild (≥ 200 to < 300) | 64 (15) | 262 (10) | 0.001 |

| No ARDS (≥ 300) | 23 (5) | 95 (4) | 0.052 |

| pH, median (Q1; Q3) | 7.40 (7.32; 7.45) | 7.42 (7.35; 7.46) | < 0.001 |

| PaCO2, median (Q1; Q3), mmHg | 39.7 (34; 47) | 38.4 (33.7; 45.6) | 0.176 |

| Laboratory findings at ICU admission | |||

| Haemoglobin, median (Q1; Q3), g/dL | 13.1 (11.9; 14.2) | 13.3 (12.2; 14.4) | 0.002 |

| Leucocyte count, median (Q1; Q3), 109/L | 7.9 (5.8; 11.5) | 9.1 (6.5; 12.5) | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocyte count, median (Q1; Q3), 109/L | 0.8 (0.56; 1.1) | 0.7 (0.49; 0.97) | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophil count, median (Q1; Q3), 109/L | 6.5 (4.5; 9.7) | 7.8 (5.3; 11.1) | < 0.001 |

| Monocyte count, median (Q1; Q3), 109/L | 0.35 (0.2; 0.54) | 0.35 (0.2; 0.52) | 0.965 |

| Platelet count, median (Q1; Q3), 109/L | 221 (169; 299) | 235 (179; 307) | 0.005 |

| d-dimer, median (Q1; Q3), ng/mL | 946 (502; 2,260) | 941 (500; 2,116) | 0.953 |

| C-reactive protein, median (Q1; Q3), mg/L | 150 (84; 237) | 130 (64; 222) | 0.001 |

| C-reactive protein ≥ 150 mg/L, n (%) | 284 (50) | 1485 (44) | 0.008 |

| Serum creatinine, median (Q1; Q3), mg/dL | 0.87 (0.69; 1.1) | 0.84 (0.68; 1.07) | 0.126 |

| LDH, median (Q1; Q3), U/L | 473 (362; 632) | 482 (364; 657) | 0.289 |

| Ferritin, median (Q1; Q3), ng/mL | 1076 (531; 1730) | 1164 (626; 1949) | 0.174 |

| High inflammation, n (%)b | 244 (79) | 1699 (73) | 0.013 |

| Ventilatory support, n (%) | |||

| Mechanical ventilation at ICU admissionc | < 0.001 | ||

| No mechanical ventilation | 89 (14) | 218 (6) | < 0.001 |

| High-flow nasal cannula | 147 (24) | 1133 (32) | < 0.001 |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 23 (4) | 375 (11) | < 0.001 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 356 (58) | 1789 (51) | < 0.001 |

| ECMO support during ICU admission | 9 (1) | 70 (2) | 0.364 |

| COVID-19 therapies during ICU admission, n (%) | |||

| Ribavirin | 6 (1) | 2 (0.1) | < 0.001 |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | 493 (78) | 1385 (39) | < 0.001 |

| Remdesivir | 39 (6) | 653 (18) | < 0.001 |

| Interferon alpha | 8 (1) | 11 (0.3) | 0.004 |

| Interferon beta | 301 (48) | 538 (15) | < 0.001 |

| Chloroquine | 72 (11) | 96 (3) | < 0.001 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 468 (74) | 1556 (43) | < 0.001 |

| Tocilizumab | 221 (35) | 1498 (42) | 0.001 |

| Darunavir/cobicistat | 22 (3) | 41 (1) | < 0.001 |

ICU intensive care unit, Q1 first quartile, Q3 third quartile, BMI body mass index, APACHE acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, SOFA sequential organ failure assessment, PaO2 partial pressure of arterial oxygen, FiO2 fraction of inspired oxygen, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, ECMO extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Percentages calculated on non-missing data

aPossibly > 1 comorbidity

bAt least two of the following criteria: ferritin > 1,000 ng/mL or d-dimer > 1000 ng/mL or C-reactive protein > 100 mg/L

cPatients who received high-flow nasal cannula but needed non-invasive intubation were included in the non-invasive mechanical ventilation group. Patients who received high-flow nasal cannula and/or non-invasive ventilation but needed intubation were included in the invasive mechanical ventilation group

Table 2.

Characteristics of corticosteroid use

| Variablesa | Corticosteroid treatment (N = 3592) |

|---|---|

| Administered drug, n (%) | |

| Dexamethasone | 2045 (60) |

| Methylprednisolone | 1882 (56) |

| Hydrocortisone | 287 (8) |

| Prednisone | 38 (1) |

| Prednisolone | 12 (0.4) |

| Betamethasone | 5 (0.1) |

| Fludrocortisone | 1 (0.03) |

| Days from initial symptoms to corticosteroid administration, median (Q1; Q3) | 9 (6; 13) |

| < 7 days, n (%) | 896 (27) |

| Days from ICU admission to corticosteroid administration, median (Q1; Q3) | 0 (− 2; 1) |

| Before ICU admission (< 0 h), n (%) | 1307 (39) |

| Day 0–1 of ICU admission (0–48 h), n (%) | 1275 (38) |

| Since day 1 of ICU admission (≥ 48 h), n (%) | 741 (22) |

| Cumulative dose | |

| Length of treatment, median (Q1; Q3), days | 10 (6; 12) |

| Prevalence of long-term use (≥ 10 days), n (%) | 1914 (58) |

| Discontinuation before mechanical ventilation termination | 1475 (60) |

| Requirement of reintubationb | 76 (9) |

| Total dose, median (Q1; Q3), mg/dayc | 15 (6; 30) |

| Prevalence of high dose (≥ 12 mg/day), n (%)c | 1899 (61) |

| Total dose, median (Q1; Q3), mg/kg/dayd | 1 (0.45; 2.04) |

ICU intensive care unit, Q1 first quartile, Q3 third quartile. Percentages calculated on non-missing data

aAdministered drug was assessed in 3388 patients; days from initial symptoms to corticosteroid administration in 3317 patients; days from ICU admission to corticosteroid administration in 3323 patients; length of treatment in 3283 patients; total equivalent dexamethasone dose in 3098 patients; total equivalent methylprednisolone dose in 2898 patients

bPatients that returned to invasive mechanical ventilation after discontinuation of corticosteroids treatment

cEquivalent dexamethasone dose

dEquivalent methylprednisolone dose

Primary and secondary outcomes

The proportion of 90-day mortality was similar between patients who received corticosteroids and those who did not (Table 3). Nonetheless, the Kaplan–Meier curves show that patients without corticosteroids had a higher likelihood of 90-day mortality (p < 0.001) than patients with corticosteroids (Online Fig. 2). In the propensity-adjusted multivariable analysis, 90-day mortality was significantly associated with corticosteroid use, decreasing the risk of 90-day mortality by 23% (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.65–0.92; p = 0.003) (Table 4 and Online Tables 4-5).

Table 3.

Complications during ICU admission and outcome variables

| Variables | No treatment (N = 634) | Corticosteroid treatment (N = 3592) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications, n (%) | |||

| Bacterial pneumoniaa | 118 (19) | 1005 (28) | < 0.001 |

| Microbiologically confirmed pneumoniab | 82 (14) | 771 (23) | < 0.001 |

| Pneumothorax | 26 (4) | 292 (8) | < 0.001 |

| Pleural effusion | 43 (7) | 413 (12) | < 0.001 |

| Organising pneumonia | 7 (1) | 206 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Tracheobronchitis | 4 (1) | 34 (1) | 0.435 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 37 (6) | 376 (11) | < 0.001 |

| Septic shockc | 38 (7) | 216 (7) | 0.807 |

| Endocarditis | 1 (0.2) | 13 (0.4) | 0.708 |

| Myocarditis/pericarditis | 14 (2) | 66 (2) | 0.523 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 14 (2) | 60 (2) | 0.338 |

| Heart failure | 11 (2) | 82 (2) | 0.393 |

| Cardiac ischemia | 10 (2) | 78 (2) | 0.340 |

| Bacteraemia | 147 (23) | 1021 (28) | 0.008 |

| Stroke | 13 (2) | 61 (2) | 0.526 |

| Delirium | 96 (15) | 723 (20) | 0.004 |

| Coagulation disorderd | 133 (21) | 709 (20) | 0.416 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulatione | 48 (38) | 148 (21) | < 0.001 |

| Anaemiaf | 324 (51) | 2061 (57) | 0.004 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 17 (3) | 133 (4) | 0.204 |

| Acute renal failureg | 218 (34) | 1102 (31) | 0.062 |

| Pancreatitis | 5 (1) | 31 (1) | 0.855 |

| Liver dysfunction | 160 (25) | 1003 (28) | 0.171 |

| Hyperglycaemia | 322 (51) | 2432 (68) | < 0.001 |

| Haemorrhage | 27 (4) | 283 (8) | 0.001 |

| Outcomes | |||

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 207 (33) | 1051 (29) | 0.085 |

| 90-day mortalityh | 208 (34) | 1062 (32) | 0.273 |

| Length of ICU stay, median (Q1; Q3), days | |||

| All patients | 10 (5; 19) | 15 (8; 29) | < 0.001 |

| Surviving patients | 11 (5; 22) | 13 (7; 29) | < 0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay, median (Q1; Q3), days | |||

| All patients | 17 (10; 31) | 25 (16; 43) | < 0.001 |

| Surviving patients | 22 (14; 37) | 27 (17; 47) | < 0.001 |

| Ventilator-free days, median (Q1; Q3) | 0 (0; 16) | 0 (0; 16) | 0.723 |

| Mechanical ventilation length, median (Q1; Q3)i, days | |||

| All patients | 12 (6; 19) | 16 (9; 28) | < 0.001 |

| Surviving patients | 13 (9; 22) | 14 (8; 27) | 0.075 |

| ICU-free days, median (Q1; Q3) | 6 (0; 20) | 3 (0; 19) | 0.016 |

| Tracheostomy, n (%) | 157 (25) | 1130 (31) | 0.001 |

| Reintubation, n (%)j | 15 (7) | 124 (8) | 0.522 |

ICU intensive care unit, Q1 first quartile, Q3 third quartile. Percentages calculated on non-missing data

aClinically or radiologically diagnosed bacterial pneumonia managed with antimicrobials. Bacteriologic confirmation was not required

bMicrobiologically confirmed nosocomial pneumonia was defined clinically or radiologically diagnosed bacterial pneumonia managed with antimicrobials with positive culture of pathogenic germs in respiratory secretions samples

cCriteria for the Sepsis-3 definition of septic shock include vasopressor treatment and a lactate concentration > 2 mmol/L at ICU admission

dAbnormal coagulation was identified by abnormal prothrombin time or activated partial thromboplastin time

eDisseminated intravascular coagulation was defined by thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time, low fibrinogen, elevated d-dimer and thrombotic microangiopathy

fHaemoglobin consistently below 120 g/L for non-pregnant women and 130 g/L for men

gAcute renal injury was defined as either an increase in serum creatinine by ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 h or an increase in serum creatinine to ≥ 1.5 times that at baseline

hCalculated only for patients with 90-day follow-up (615 in the no treatment group and 3363 in the corticosteroid treatment group)

iDuration of invasive mechanical ventilation was measured from initiation of ventilation until either successful extubation, successful permanent disconnection or death

jReintubation due to extubation failure

Table 4.

Association of corticosteroid therapy and 90-day mortality

| Univariable analysis | Adjusted analysisa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| All patients (N = 4226) | 0.74 (0.63–0.86) | < 0.001 | 0.77 (0.65–0.92) | 0.003 |

| Subgroup analysesb | ||||

| Age group | 0.001c | |||

| Age < 60 years (n = 1611) | 1.25 (0.82–1.90) | 0.296 | 1.33 (0.83–2.11) | 0.233 |

| Age ≥ 60 years (n = 2615) | 0.60 (0.51–0.71) | < 0.001 | 0.69 (0.57–0.83) | < 0.001 |

| Severity of illness at ICU admission group | 0.260c | |||

| APACHE-II score < 12 (n = 1112) | 0.87 (0.57–1.34) | 0.539 | 1.00 (0.60–1.67) | 0.999 |

| APACHE-II score ≥ 12 (n = 1110) | 0.58 (0.44–0.76) | < 0.001 | 0.65 (0.47–0.89) | 0.007 |

| Organ dysfunction and failure at ICU admission group | 0.014c | |||

| SOFA score < 5 (n = 1348) | 1.26 (0.80–1.98) | 0.318 | 1.24 (0.75–2.05) | 0.397 |

| SOFA score ≥ 5 (n = 1354) | 0.61 (0.48–0.79) | < 0.001 | 0.55 (0.42–0.73) | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory findings at ICU admission | ||||

| Lymphocyte count group | 0.159c | |||

| Lymphocyte count < 0.724 × 109/L (n = 2117) | 0.67 (0.54–0.84) | 0.001 | 0.68 (0.53–0.87) | 0.002 |

| Lymphocyte count ≥ 0.724 × 109/L (n = 1808) | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) | 0.033 | 0.89 (0.67–1.18) | 0.430 |

| C-reactive protein group | 0.093c | |||

| C-reactive protein < 150 mg/L (n = 2161) | 0.76 (0.59–0.96) | 0.024 | 0.85 (0.64–1.12) | 0.248 |

| C-reactive protein ≥ 150 mg/L (n = 1769) | 0.67 (0.53–0.83) | < 0.001 | 0.71 (0.55–0.92) | 0.009 |

| Inflammation group | 0.708c | |||

| Low inflammation (n = 707)d | 0.73 (0.41–1.31) | 0.290 | 0.55 (0.27–1.13) | 0.103 |

| Age < 60 years (n = 320) | 0.93 (0.23–3.76) | 0.922 | 0.88 (0.11–7.39) | 0.909 |

| Age ≥ 60 years (n = 387) | 0.52 (0.26–1.03) | 0.061 | 0.43 (0.17–1.10) | 0.079 |

| High inflammation (n = 1943)d | 0.62 (0.48–0.79) | < 0.001 | 0.59 (0.45–0.77) | < 0.001 |

| Age < 60 years (n = 667) | 1.12 (0.55–2.30) | 0.749 | 1.59 (0.66–3.85) | 0.304 |

| Age ≥ 60 years (n = 1276) | 0.51 (0.39–0.66) | < 0.001 | 0.50 (0.37–0.68) | < 0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation at ICU admission group | 0.001c | |||

| No mechanical ventilation (n = 307) | 1.55 (0.81–2.95) | 0.185 | 1.38 (0.62–3.06) | 0.433 |

| High-flow nasal cannula/non-invasive mechanical ventilation (n = 1678) | 0.96 (0.65–1.43) | 0.859 | 0.70 (0.45–1.09) | 0.115 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation (n = 2145) | 0.64 (0.53–0.78) | < 0.001 | 0.68 (0.56–0.84) | < 0.001 |

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, APACHE acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, SOFA sequential organ failure assessment

aAdjusted for variables (age, sex, body mass index, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, chronic heart disease, chronic lung disease, chronic renal failure, immunosuppression, APACHE-II score at ICU admission, PaO2/FiO2 ratio at ICU admission, pH at ICU admission, haemoglobin at ICU admission, lymphocyte count at ICU admission, platelet count at ICU admission, D-dimer at ICU admission, C-reactive protein, serum creatinine at ICU admission, LDH at ICU admission, ferritin at ICU admission, mechanical ventilation at ICU admission, septic shock at ICU admission, disseminated intravascular coagulation at ICU admission, tocilizumab administration, COVID-19 wave and the propensity score)

bAPACHE-II score was assessed in 2222 patients; SOFA score in 2702 patients; lymphocyte count in 3925 patients; C-reactive protein in 3930 patients; inflammation in 2650 patients; and mechanical ventilation in 4130 patients

cInteraction effect for the subgroup and treatment group

dHigh inflammation was defined as the fulfilment of at least two of the following criteria: ferritin > 1000 ng/mL or d-dimer > 1000 ng/mL or C-reactive protein > 100 mg/L

Length of ICU and hospital stay, mechanical ventilation duration and tracheostomy were higher in the corticosteroid group yet overall lower ICU-free days; 90-day mortality and ventilator-free days were similar between groups (Table 3). Propensity-adjusted analyses showed that in-hospital mortality was significantly associated with corticosteroid use, decreasing the risk by 30% (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.58–0.84; p < 0.001; Online Table 4). Propensity-adjusted analyses also showed that there was a significant association between corticosteroid use and longer length of ICU (β 7.08, 95% CI 5.67–8.50; p = 0.004) and longer hospital stay (β 9.96, 95% CI 7.79–12.14; p < 0.001); while no significant association between corticosteroid use and the number ventilator-free days (Online Tables 6–10).

Subgroup analyses

To examine risks for particular types of patients, we explored effect modification by age, APACHE-II score, SOFA score, lymphocyte count, C-RP, inflammation and mechanical ventilation. No significant effect modification was found after adjustment for covariates using propensity score, except for age (p = 0.001 interaction term), Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (p = 0.014 interaction term), and mechanical ventilation (p = 0.001 interaction term) (Table 4).

In addition, propensity-adjusted analyses showed that systemic corticosteroids were associated with a lower risk of 90-day mortality in the following subgroups: (1) patients aged ≥ 60 years; (2) patients with more severe clinical status at day 1 in ICU (SOFA ≥ 5); and (3) patients with invasive mechanical ventilation at day 1 in ICU (Table 4).

Among the overall population receiving corticosteroids, there was also significant association between early administration of corticosteroids since initial symptom onset (< 7 days) and increasing the propensity-adjusted risk of 90-day mortality by 32% (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.14–1.53; p < 0.001) (Online Table 11). Corticosteroid administration within 7 days from symptoms onset was unbeneficial or even harmful in all subgroups defined based on ICU admission data (Online Table 11).

In contrast, there were no significant associations observed either between the early administration of corticosteroids since ICU admission (< 48 h) and the propensity-adjusted risk of 90-day mortality (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.79–1.10; p = 0.392; Online Table 12); or the high-dose corticosteroids (≥ 12 mg/day) and the propensity-adjusted risk of 90-day mortality (HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.89–1.24; p = 0.559; Online Table 13). Exceptions to these no effect are further explored in Online Tables 12–13, respectively.

There was also significant association between long-term corticosteroids (≥ 10 days) and decreasing the propensity-adjusted risk of 90-day mortality by 29% (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61–0.82; p < 0.001) (Online Table 14). Those associations between long-term corticosteroids (≥ 10 days) and 90-day mortality extended to some of the studied subgroups of patients (Online Table 14).

When analysing corticosteroid treatment and the secondary outcomes, those associations extended to some of the subgroups of patients (i.e., age, illness severity and organ damage, laboratory findings and invasive mechanical ventilation at ICU admission) as further described in Online Tables 4–10.

Complications

When compared to the non-corticosteroid group, patients in the corticosteroid group more frequently presented nosocomial bacterial pneumonia, pneumothorax, pleural effusion, organising pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, bacteraemia, delirium, anaemia, hyperglycaemia and haemorrhage. Conversely, this same group presented disseminated intravascular coagulation less frequently (Table 3).

When analysing nosocomial bacterial pneumonia, propensity-adjusted analysis showed a significant increased risk for developing the infection among those patients that received corticosteroids (OR 1.29; 95% CI 1.01–1.65; p = 0.042; Online Table 15). Moreover, corticosteroids use was also significantly associated with higher risk for developing microbiologically confirmed nosocomial pneumonia (OR 1.38; 95% 1.01–1.88; p = 0.045; Online Table 16). Similarly, propensity-adjusted analysis showed that there was a significant higher risk of hyperglycaemia (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.35–3.48; p = 0.001; Online Table 17). In contrast, there were no significant association observed between corticosteroids and the propensity-adjusted risk of haemorrhage (OR 1.32%, CI 0.92–1.89; p = 0.131; Online Table 18). Those associations between treatment with corticosteroids and complications extended to some of the studied subgroups of patients (Online Table 15–18).

Discussion

In this large, multicentre and retrospective observational study of consecutive critically ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to 55 Spanish ICUs, we investigated the association between corticosteroid treatment and 90-day mortality. Furthermore, we examined the existence of subpopulations for whom corticosteroids could prove unbeneficial or even harmful, and evaluated the risk of complications associated with corticosteroid use.

Our study resulted in various main findings, as displayed in Fig. 1 and Online Fig. 3. First, after adjusting for confounding variables, we observed that using corticosteroids was protective for 90-day and in-hospital mortality in the overall population. However, patients receiving corticosteroids had a longer length ICU and hospital stay. Second, we reported a beneficial effect conferred by corticosteroids on 90-day mortality across the following three subgroups: (1) patients aged ≥ 60 years; (2) patients with higher baseline severity and (3) patients requiring invasive mechanical at ICU admission. Third, early administration of corticosteroids since initial symptom onset was associated with a higher risk of 90-day mortality in the overall population, especially in some patient subgroups. Fourth, 10 days or more of administration of corticosteroids resulted in a 90-day increased survival. Finally, corticosteroid use was associated with an increased risk of both clinically suspected and microbiologically confirmed nosocomial bacterial pneumonia and hyperglycaemia in the overall population.

Fig. 1.

Summary of results for 90-day mortality (HRs and 95% CI) and complications (ORs and 95% CI)

In our cohort of critically ill, ICU-admitted patients with respiratory failure, our data confirmed results obtained from previous studies that reported an association between decreased 28-day and/or in-hospital mortality and corticosteroid use in patients with severe COVID-19 [1, 7, 8, 30]. This observation falls in line with current recommendations [6, 9, 31, 32]. Moreover, we found that corticosteroid use proved beneficial in decreasing 90-day mortality across the aforementioned subgroups. These findings are important, given that previous studies have not extensively reported thereof.

Overall, when it comes to corticosteroid use, age appears to be an important factor worth considering. The RECOVERY trial [7], for instance, reported no efficacy of corticosteroid use in the subgroup of patients aged > 70 years; however, only 169 (4.74%) patients from that particular group were on mechanical ventilation. Another recently published study [10] showed that mortality rose in patients aged ≥ 80 years receiving corticosteroids. There are two primary reasons that may explain these discrepancies between our study and those prior as follows: (1) the heterogeneity of populations included in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies (different severity and degrees of respiratory failure, different age threshold); and (2) the varying immunophenotypes (humoral immunodeficiency, hyper-inflammatory and complement-dependent) recently identified in critically ill patients [33].

Another significant finding is that corticosteroids decreased 90-day mortality in mechanically ventilated patients at ICU admission. In line with our results, the WHO meta-analysis found that corticosteroids were associated with lower mortality in critically ill patients who were receiving invasive mechanical ventilation at randomization [8]. In this context, we can recommend that all mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 receive corticosteroids.

Early administration of corticosteroids in ICU and high-versus-low dosages represent other clinical scenarios that could affect benefits conferred by such medication. Remarkably, we found that corticosteroids were associated with increased mortality in the overall population when administered early after initial symptom onset (Fig. 1, Online Fig. 3). In this context, recent observational publications suggest that early administration of corticosteroids after symptom onset (< 7 days) can prove harmful for patients [34, 35]. Corticosteroids may increase viral replication during the initial disease stage, resulting in a deterioration of the patient’s status. In view of such results, our recommendation is to not administer corticosteroids during the early disease period (i.e., within the first seven days of symptom onset).

With respect to early administration of corticosteroids in ICU, we found no differences when compared to late administration of this medication in the overall population. Other observational studies have indicated [36, 37] that early administration of corticosteroids in ICU is associated with decreased mortality. In addition, Van Passen et al. [38] found decreased progression to mechanical ventilation when clinicians administered corticosteroids early in ICU. Varying definitions regarding early and late administration could explain overall differences with our study. Our findings, as observed in a very large population, highlight the importance of not discarding corticosteroid administration in ICU-admitted patients with COVID-19 after the first 48 h of ICU admission.

Regarding dosage and corticosteroid use, we did not find differences between high and low doses. A recent RCT comparing 6 vs 12 mg of dexamethasone in adults requiring either at least 10 L/min of oxygen or mechanical ventilation did not result in more statistically significant survival days without life support at 28 days [16]. Serious, infectious adverse events were similar in both groups.

Nevertheless, the risk of nosocomial infections in relation to corticosteroid use in COVID-19 cases remains controversial. Graselli et al. [39] did not observe such a relationship; however, they did find an association between the aforementioned risk and the use of tocilizumab. Furthermore, observational and meta-analysis of RCTs in severe COVID-19 and in non-COVID-19 ARDS did also not find this association [11, 17, 40, 41]. In contrast, though, our results showed that patients who received corticosteroids faced an elevated risk of both clinically suspected and microbiologically confirmed nosocomial pneumonia. This finding raises an important concern: worse outcomes have been observed in patients with COVID-19 and co-infections in comparison to patients without such complications [42]. It may be argued that this increased risk was due to increased length of hospital stay in patients receiving corticosteroids (Online Tables 8–9). However, our results were adjusted by this variable. We also observed an increased risk of hyperglycaemia in patients who received corticosteroids, as previously described [7]. Since all complications deriving from corticosteroid use can lead to higher mortality and morbidity, we believe that clinicians should be careful when administering corticosteroids and avoid their use when harm is possible or there is no benefit.

Another important finding of our study is that the duration of corticosteroid treatment 10 days or more was significantly associated with increased 90-day survival. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis in both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 ARDS showed that patients receiving corticosteroids more than 7 days better survival [41]. Our results fit also with the concepts from Meduri et al. [43] in non-COVID ARDS. Unfortunately, we do not have data about tapering corticosteroids, and we cannot give precise recommendation on how tapering has to be done. Thus, we cannot exclude that some complications may have occurred as a result of termination of treatment without tapering. However, our rates of reintubation were similar between both groups [44].

Major strengths of this study include its multicentre nature, the consecutive inclusion of all patients from each unit, thorough checking of data quality, and the high number of patients analysed and long-term follow-up. Limitations of our study include a lack of data on live virus shedding, which represents a variable that can affect outcomes in patients receiving corticosteroids [45]. Moreover, despite exhaustive propensity score analysis for underlying conditions, a possible limitation of the propensity score methods is their inability to control for unmeasured confounding. Another limitation is the different waves of the pandemic, which could have influenced our results (Online Table 19); we have, however, adjusted all of our analyses for this confounder and similar results were obtained when only patients from first wave were included (Online Table 5). Finally, as we examined real-world data, limitations associated with the observational nature and missing (e.g., different dosage, high-dose bolus, tapering, etc.) should be considered.

In summary (Fig. 1, Online Fig. 3), we confirmed that corticosteroid treatment decreased 90-day mortality and in-hospital mortality in a large population of patients with COVID-19 admitted to Spanish ICU units. However, clinicians should consider age, baseline disease severity, and the need of invasive mechanical ventilation to administer corticosteroids. Use of such medications may not confer any benefit on or, conversely, could cause harm in some patient subgroups. Specifically, clinicians should avoid administering corticosteroids early after patients develop initial symptoms. Also, they should take into account the potential risk for nosocomial bacterial pneumonia and hyperglycaemia. With particular group exceptions, neither early administration of corticosteroids in ICU nor high-dose corticosteroids were associated with 90-day mortality. However, 10 days of more of administration of corticosteroids resulted in a 90 days increased survival.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to all participating medical and nursing colleagues for their assistance and cooperation in this study. Thank you to Anthony Armenta for providing language editing assistance for this article.

CIBERESUCICOVID Project Investigators: Rafael Mañez: Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, Barcelona. Felipe Rodríguez de Castro: Hospital Dr. Negrín, Las Palmas. María Mora Aznar: Hospital Nuestra Señora de Gracia, Zaragoza. Mateu Torres, María Martinez, Cynthia Alegre, Sofía Contreras: Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona. Javier Trujillano, Montse Vallverdú, Miguel León, Mariona Badía, Begoña Balsera, Lluís Servià, Judit Vilanova, Silvia Rodríguez, Neus Montserrat, Silvia Iglesias, Javier Prados, Sula Carvalho, Mar Miralbés, Josman Monclou, Gabriel Jiménez, Jordi Codina, Estela Val, Pablo Pagliarani, Jorge Rubio, Dulce Morales, Andrés Pujol, Àngels Furro, Beatriz García, Gerard Torres, Javier Vengoechea, David de Gozalo Calvo, Jessica González, Silvia Gomez: Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova, Lleida. Lorena Forcelledo Espina, Emilio García Prieto, Paula Martín Vicente, Cecilia del Busto Martínez: Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo. María Aguilar Cabello, Carmen Eulalia Martínez Fernández: Hospital San Juan de Dios del Aljarafe, Sevilla. María Luisa Blasco Cortés, Ainhoa Serrano Lázaro, Mar Juan Díaz: Hospital Clínic Universitari de València, Valencia. María Teresa Bouza Vieiro, Inés Esmorís Arijón: Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti, Lugo. David Campi Hermoso., Rafaela Nogueras Salinas., Teresa Farre Monjo., Ramon Nogue Bou., Gregorio Marco Naya., Núria Ramon Coll: Hospital Universitari de Santa Maria, Lleida. Juan Carlos Montejo-González: Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid. Gloria Renedo Sanchez-Giron, Juan Bustamante-Munguira, Ramon Cicuendez Avila, Nuria Mamolar Herrera: Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valladolid. Alexander Agrifoglio, Lucia Cachafeiro, Emilio Maseda: Hospital Universitario La Paz-Carlos III, Madrid. Albert Figueras, Maria Teresa Janer, Laura Soliva, Marta Ocón, Luisa Clar, J Ignacio Ayestarán: Hospital Universitario Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca. Sandra Campos Fernández: Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander. Eva Forcadell-Ferreres, Immaculada Salvador-Adell, Neus Bofill, Berta Adell-Serrano, Josep Pedregosa Díaz, Núria Casacuberta-Barberà, Luis Urrelo-Cerrón, Àngels Piñol-Tena, Ferran Roche-Campo: Hospital Verge de la Cinta de Tortosa, Tortosa. Pablo Ryan Murúa, Covadonga Rodríguez Ruíz, Laura Carrión García, Juan I Lazo Álvarez: Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor, Madrid. Desire Macias Guerrero: Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme, Sevilla. Daniel Tognetti: Clinica Sagrada Familia, Barcelona. Carlos García Redruello, David Mosquera Rodríguez, Eva María Menor Fernández, Sabela Vara Adrio, Vanesa Gómez Casal, Marta Segura Pensado, María Digna Rivas Vilas, Amaia García Sagastume: Hospital de Vigo, Vigo. Raul de Pablo Sánchez, David Pestaña Laguna, Tommaso Bardi: Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, Madrid. Carmen Gómez Gonzalez, Maria Luisa Gascón Castillo: Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocio, Sevilla. José Garnacho-Montero: Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla. Joan Ramon Masclans, Ana Salazar Degracia, Judit Bigas, Rosana Muñoz-Bermúdez, Clara Vilà-Vilardel, Francisco Parrilla, Irene Dot, Ana Zapatero, Yolanda Díaz, María Pilar Gracia, Purificación Pérez, Andrea Castellví, Cristina Climent: Hospital del Mar, Barcelona. Lidia Serra, Laura Barbena, Iosune Cano: Consorci Sanitari del Maresme, Barcelona. Alba Herraiz, Pilar Marcos, Laura Rodríguez, Maria Teresa Sariñena, Ana Sánchez: Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona. Juan Fernando Masa Jimenez: Hospital Universitario San Pedro de Alcántara, Cáceres. Gemma Gomà: Hospital Parc Taulí, Sabadell. Mercedes Ibarz, Diego De Mendoza: Hospital Universitari Sagrat Cor, Bacelona. Enric Barbeta, Victoria Alcaraz-Serrano, Joan Ramon Badia, Manuel Castella, Leticia Bueno, Laia Fernandez Barat, Catia Cillóniz, Pamela Conde, Javier Fernández, Albert Gabarrus, Karsa Kiarostami, Alexandre López- Gavín, Cecilia L Mantellini, Carla Speziale, Nil Vázquez, Hua Yang, Minlan Yang, Carlos Ferrando, Pedro Castro, Marta Arrieta, Jose Maria Nicolas, Rut Andrea: Hospital Clinic, Barcelona. Marta Barroso, Sergio Álvarez, Dario Garcia-Gasulla, Adrián Tormos: Barcelona supercomputing Center, Barcelona. Cesar Aldecoa, Rubén Herrán-Monge, José Ángel Berezo García, Pedro Enríquez Giraudo: Hospital Rio Hortega, Valladolid. Pablo Cardinal Fernández, Alberto Rubio López, Orville Báez Pravia: Hospitales HM, Madrid. Leire Pérez Bastida, Antonjo Alvarez Ruiz: Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Palencia, Palencia. Anna Parera Pous: Hospital Universitari MutuaTerrassa, Terrassa. Ana López Lago, Eva Saborido Paz, Patricia Barral Segade: Hospital de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago. Manuel Valledor Mendez: Hospital San Agustin, Aviles. Luciano Aguilera: Hospital Basurto, Basurto. Esther López-Ramos, Ángela Leonor Ruiz-García, Belén Beteré: Hospital Universitario Principe Asturias , Alcala de Henares. Rafael Blancas: Hospital Universitario del Tajo, Aranjuez. Cristina Dólera, Gloria Perez Planelles, Enrique Marmol Peis, Maria Dolores Martinez Juan, Miriam Ruiz Miralles, Eva Perez Rubio, Maria Van der Hofstadt Martin-Montalvo, Tatiana Villada Warrington: Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante. Sara Guadalupe Moreno Cano: Hospital de Jerez, Jerez. Federico Gordo: Hospital Universitario del Henares, Coslada. Basilisa Martinez Palacios: Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina, Parla. Maria Teresa Nieto: Hospital de Segovia, Segovia. Sergio Ossa: Hospital de Burgos, Burgos. Ana Ortega: Hospital Montecelo, Pontevedra. Miguel Sanchez: Hospital Clinico, Madrid. Bitor Santacoloma: Hospital Galdakao, Galdakao.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the study: AT, AM, CC, AC, LFB, FB. Data acquisition: all authors. Statistical analysis: AG. Data analysis and interpretation: AT, AM, CC, AC, LFB, JBM, FB. Manuscript drafting: AT, AM, CC, AC, LFB, AG. Critical revision for important intellectual content: all authors. Final approval of the submitted version: all authors. CiberesUCICOVID consortium participated in data collection.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III de Madrid (COV20/00110, ISCIII); Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); "Una manera de hacer Europa"; and Centro de Investigación Biomedica En Red—Enfermedades Respiratorias (CIBERES). DdGC has received financial support from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Miguel Servet 2020: CP20/00041), co-funded by European Social Fund (ESF)/“Investing in your future”. CC received a grant from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (PI19/00207), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, co-funded by the European Union. Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding sources had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have disclosed that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Collaborators of the CIBERESUCICOVID project are listed in the Acknowledgement section.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Antoni Torres and Anna Motos equally contributed.

Contributor Information

Antoni Torres, Email: atorres@clinic.cat.

Ana Motos, Email: amotos@clinic.cat.

the CIBERESUCICOVID Project Investigators:

Rafael Mañez, Felipe Rodríguez de Castro, María Mora Aznar, Mateu Torres, María Martinez, Cynthia Alegre, Sofía Contreras, Javier Trujillano, Montse Vallverdú, Miguel León, Mariona Badía, Begoña Balsera, Lluís Servià, Judit Vilanova, Silvia Rodríguez, Neus Montserrat, Silvia Iglesias, Javier Prados, Sula Carvalho, Mar Miralbés, Josman Monclou, Gabriel Jiménez, Jordi Codina, Estela Val, Pablo Pagliarani, Jorge Rubio, Dulce Morales, Andrés Pujol, Àngels Furro, Beatriz García, Gerard Torres, Javier Vengoechea, David de Gozalo Calvo, Jessica González, Silvia Gomez, Lorena Forcelledo Espina, Emilio García Prieto, Paula Martín Vicente, Cecilia del Busto Martínez, María Aguilar Cabello, Carmen Eulalia Martínez Fernández, María Luisa Blasco Cortés, Ainhoa Serrano Lázaro, Mar Juan Díaz, María Teresa Bouza Vieiro, Inés Esmorís Arijón, David Campi Hermoso, Rafaela Nogueras Salinas, Teresa Farre Monjo, Ramon Nogue Bou, Gregorio Marco Naya, Núria Ramon Coll, Juan Carlos Montejo-González, Gloria Renedo Sanchez-Giron, Juan Bustamante-Munguira, Ramon Cicuendez Avila, Nuria Mamolar Herrera, Alexander Agrifoglio, Lucia Cachafeiro, Emilio Maseda, Albert Figueras, Maria Teresa Janer, Laura Soliva, Marta Ocón, Luisa Clar, J. Ignacio Ayestarán, Sandra Campos Fernández, Eva Forcadell-Ferreres, Immaculada Salvador-Adell, Neus Bofill, Berta Adell-Serrano, Josep Pedregosa Díaz, Núria Casacuberta-Barberà, Luis Urrelo-Cerrón, Àngels Piñol-Tena, Ferran Roche-Campo, Pablo Ryan Murúa, Covadonga Rodríguez Ruíz, Laura Carrión García, Juan I. Lazo Álvarez, Desire Macias Guerrero, Daniel Tognetti, Carlos García Redruello, David Mosquera Rodríguez, Eva María Menor Fernández, Sabela Vara Adrio, Vanesa Gómez Casal, Marta Segura Pensado, María Digna Rivas Vilas, Amaia García Sagastume, Raul de Pablo Sánchez, David Pestaña Laguna, Tommaso Bardi, Carmen Gómez Gonzalez, Maria Luisa Gascón Castillo, José Garnacho-Montero, Joan Ramon Masclans, Ana Salazar Degracia, Judit Bigas, Rosana Muñoz-Bermúdez, Clara Vilà-Vilardel, Francisco Parrilla, Irene Dot, Ana Zapatero, Yolanda Díaz, María Pilar Gracia, Purificación Pérez, Andrea Castellví, Cristina Climent, Lidia Serra, Laura Barbena, Iosune Cano, Alba Herraiz, Pilar Marcos, Laura Rodríguez, Maria Teresa Sariñena, Ana Sánchez, Juan Fernando Masa Jimenez, Gemma Gomà, Mercedes Ibarz, Diego De Mendoza, Enric Barbeta, Victoria Alcaraz-Serrano, Joan Ramon Badia, Manuel Castella, Leticia Bueno, Laia Fernandez Barat, Catia Cillóniz, Pamela Conde, Javier Fernández, Albert Gabarrus, Karsa Kiarostami, Alexandre López-Gavín, Cecilia L. Mantellini, Carla Speziale, Nil Vázquez, Hua Yang, Minlan Yang, Carlos Ferrando, Pedro Castro, Marta Arrieta, Jose Maria Nicolas, Rut Andrea, Marta Barroso, Sergio Álvarez, Dario Garcia-Gasulla, Adrián Tormos, Cesar Aldecoa, Rubén Herrán-Monge, José Ángel Berezo García, Pedro Enríquez Giraudo, Pablo Cardinal Fernández, Alberto Rubio López, Orville Báez Pravia, Leire Pérez Bastida, Antonjo Alvarez Ruiz, Anna Parera Pous, Ana López Lago, Eva Saborido Paz, Patricia Barral Segade, Manuel Valledor Mendez, Luciano Aguilera, Esther López-Ramos, Ángela Leonor Ruiz-García, Belén Beteré, Rafael Blancas, Cristina Dólera, Gloria Perez Planelles, Enrique Marmol Peis, Maria Dolores Martinez Juan, Miriam Ruiz Miralles, Eva Perez Rubio, Maria Van der Hofstadt Martin-Montalvo, Tatiana Villada Warrington, Sara Guadalupe Moreno Cano, Federico Gordo, Basilisa Martinez Palacios, Maria Teresa Nieto, Sergio Ossa, Ana Ortega, Miguel Sanchez, and Bitor Santacoloma

References

- 1.Cano EJ, Fonseca Fuentes X, Corsini Campioli C, et al. Impact of corticosteroids in coronavirus disease 2019 outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2021;159:1019–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye Z, Wang Y, Colunga-Lozano LE, et al. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in COVID-19 based on evidence for COVID-19, other coronavirus infections, influenza, community-acquired pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2020;192:E756–E767. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villar J, Ferrando C, Martínez D, et al. Dexamethasone treatment for the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:267–276. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villar J, Confalonieri M, Pastores SM, Meduri GU. Rationale for prolonged corticosteroid treatment in the acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0111. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with middle east respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:757–767. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH, et al. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group. Sterne JAC, Murthy S, et al. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalmers JD, Crichton ML, Goeminne PC, et al. Management of hospitalised adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a European Respiratory Society living guideline. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2100048. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00048-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung C, Wernly B, Fjølner J, et al. Steroid use in elderly critically ill COVID-19 patients. Eur Respir J. 2021;58:2100979. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00979-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dupuis C, de Montmollin E, Buetti N, et al. Impact of early corticosteroids on 60-day mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a multicenter cohort study of the OUTCOMEREA network. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0255644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.STROBE—Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology. https://www.strobe-statement.org/. Accessed 25 Oct 2021

- 13.Schoenfeld DA, Bernard GR, Network ARDS. Statistical evaluation of ventilator-free days as an efficacy measure in clinical trials of treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1772–1777. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres A, Sibila O, Ferrer M, et al. Effect of corticosteroids on treatment failure among hospitalized patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia and high inflammatory response: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bermejo-Martin JF, Cilloniz C, Mendez R, et al. Lymphopenic community acquired pneumonia (L-CAP), an immunological phenotype associated with higher risk of mortality. EBioMedicine. 2017;24:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.COVID STEROID 2 Trial Group. Munch MW, Myatra SN, et al. Effect of 12 mg vs 6 mg of dexamethasone on the number of days alive without life support in adults with COVID-19 and severe hypoxemia: the COVID STEROID 2 randomized trial. JAMA. 2021;326:1807–1817. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annane D, Pastores SM, Rochwerg B, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency (CIRCI) in critically ill patients (Part I): Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) 2017. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:1751–1763. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4919-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torres A, Niederman MS, Chastre J, et al. International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)/ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) of the European Respiratory Society (ERS), European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and Asociación Latinoamericana del Tórax (ALAT) Eur Respir J. 2017 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00582-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torres A, Motos A, Riera J, et al. The evolution of the ventilatory ratio is a prognostic factor in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 ARDS patients. Crit Care. 2021;25:331. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03727-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanley KE, editor. Statistics in medical research: methods and issues, with applications in cancer research. Hoboken: Wiley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. 2. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. doi: 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.568786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. Hoboken: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, et al. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1149–1156. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the analysis of survival data in the presence of competing risks. Circulation. 2016;133:601–609. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176350951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanley JA, Negassa A, de Edwardes MDB, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaudhuri D, Sasaki K, Karkar A, et al. Corticosteroids in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 ARDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06394-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. In: COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/about-the-guidelines/whats-new/. Accessed 19 Nov 2021

- 32.Bartoletti M, Azap O, Barac A, et al. ESCMID COVID-19 living guidelines: drug treatment and clinical management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dupont T, Caillat-Zucman S, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, et al. Identification of distinct immunophenotypes in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients. Chest. 2021;159:1884–1893. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreno G, Carbonell R, Martin-Loeches I, et al. Corticosteroid treatment and mortality in mechanically ventilated COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients: a multicentre cohort study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11:159. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00951-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Llano LAP, Golpe R, Pérez-Ortiz D, et al. [Early initiation of corticosteroids might be harmful in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia: a multicenter propensity score analysis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monedero P, Gea A, Castro P, et al. Early corticosteroids are associated with lower mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2021;25:2. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03422-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mongardon N, Piagnerelli M, Grimaldi D, et al. Impact of late administration of corticosteroids in COVID-19 ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:110–112. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06311-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Paassen J, Vos JS, Hoekstra EM, et al. Corticosteroid use in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis on clinical outcomes. Crit Care. 2020;24:696. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03400-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grasselli G, Scaravilli V, Mangioni D, et al. Hospital-acquired infections in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Chest. 2021;160:454–465. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meduri GU, Annane D, Confalonieri M, et al. Pharmacological principles guiding prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2284–2296. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06289-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaudhuri D, Sasaki K, Karkar A, et al. Corticosteroids in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 ARDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:521–537. doi: 10.1007/s00134-021-06394-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nseir S, Martin-Loeches I, Povoa P, et al. Relationship between ventilator-associated pneumonia and mortality in COVID-19 patients: a planned ancillary analysis of the coVAPid cohort. Crit Care. 2021;25:177. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03588-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meduri GU, Marik PE, Annane D. Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment in acute respiratory distress syndrome: evidence supporting effectiveness and safety. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1800–1803. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819d2b43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meduri GU, Bridges L, Siemieniuk RAC, Kocak M. An exploratory reanalysis of the randomized trial on efficacy of corticosteroids as rescue therapy for the late phase of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:884–891. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sinha P, Furfaro D, Cummings MJ, et al. Latent class analysis reveals COVID-19-related ARDS subgroups with differential responses to corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021 doi: 10.1164/rccm.202105-1302OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.