Abstract

Negative symptoms, particularly the motivation and pleasure (MAP) deficits, are associated with impaired social functioning in patients with schizophrenia (SCZ). However, previous studies seldom examined the role of the MAP on social functioning while accounting for the complex interplay between other psychopathology. This network analysis study examined the network structure and interrelationship between negative symptoms (at the “symptom-dimension” and “symptom-item” levels), other psychopathology and social functioning in a sample of 269 patients with SCZ. The psychopathological symptoms were assessed using the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS) and the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Social functioning was evaluated using the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS). Centrality indices and relative importance of each node were estimated. The network structures between male and female participants were compared. Our resultant networks at both the “symptom-dimension” and the “symptom-item” levels suggested that the MAP factor/its individual items were closely related to social functioning in SCZ patients, after controlling for the complex interplay between other nodes. Relative importance analysis showed that MAP factor accounted for the largest proportion of variance of social functioning. This study is among the few which used network analysis and the CAINS to examine the interrelationship between negative symptoms and social functioning. Our findings supported the pivotal role of the MAP factor to determine SCZ patients’ social functioning, and as a potential intervention target for improving functional outcomes of SCZ.

Keywords: negative symptoms, motivation and pleasure dimension, social functioning, network analysis, schizophrenia

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a complex disorder with a wide variety of psychopathology affecting one’s emotion, thinking and perception.1 Negative symptoms comprise five consensus domains, ie, anhedonia, avolition, alogia, asociality and blunted affect.2 Previous studies generally supported the mapping these domains onto at least two dimensions, ie, motivation and pleasure (MAP) deficits (comprising avolition, asociality and anhedonia) and expressivity (EXP) deficits (comprising blunted affect and alogia).3,4 Although several recent studies using the Brief Negative Symptoms Scale (BNSS) supported a five-factor model for negative symptoms,5 other studies using the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS) supported a two-dimension model.6,7 The two-dimension model has been particularly well-supported by pathophysiological research findings.8

Negative symptoms strongly determines SCZ patients’ social functioning.9–11 Early studies investigating the relationship between negative symptoms and social functioning usually adopted a unitary construct of negative symptoms.2 However, the MAP and EXP factors of negative symptoms might differ in their associations with social functioning in SCZ patients,12–14 and MAP deficits are in particular closely linked to social functioning.13, 15–24 As shown in table 1, many previous studies on the relationship of the MAP and EXP factors with social functioning in SCZ patients have employed correlation and regression analyses, which were less able to account for the complex interplay between the MAP and EXP factors, other psychopathology (such as positive or disorganized symptoms), and illness-related variables (such as illness duration or antipsychotic medication side effects), as well as how such interplay would affect SCZ patients’ social functioning.21, 22, 25

Table 1.

Summary of Previous Studies on Negative Symptoms and Functioning in SCZ Patients

| Studies | Year | Participants | Measurements of Negative Symptoms | Measurements of Functioning Outcome | Data Analysis | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strauss et al13 | 2013 | 199 SCZ 169 SCZ |

SANS | CAF; RFS; LOF | Cluster analysis | • Patients with predominant MAP deficit showed poorer social functioning |

| Fervaha et al15 | 2014 | 754 SCZ | PANSS | QLS | Correlation | • MAP was correlated with quality of life • EXP was correlated with quality of life |

| Robertson et al16 | 2014 | 561 SCZ | PANSS | SLOF | Regression | • Items related to MAP predicted impairments in SLOF interpersonal relationship subscale • Items related to EXP did not predict SLOF |

| Rocca et al17 | 2014 | 92 SCZ | SANS | QLS; PSP | Regression | • MAP predicted impairments in functioning • EXP did not predict functioning |

| Fervaha et al18 | 2015 | 166 SCZ | PANSS | QLS | Regression | • MAP predicted impairments in quality of life • EXP did not predict quality of life |

| Kalin et al19 | 2015 | 179 SCZ | PANSS | SLOF; SSPA | Regression | • MAP predicted impairments in SLOF interpersonal relationship subscale • EXP predicted social competence |

| Harvey et al20 | 2017 | 630 SCZ | PANSS | SLOF | Regression | • MAP predicted impairments in SLOF • EXP did not predict SLOF |

| Rocca et al21 | 2018 | 880 SCZ | BNSS | SLOF | SEM | • MAP was directly linked with SLOF work skills, activities and interpersonal relationship subscales • EXP was directly linked with SLOF activities subscales |

| Ang et al22 | 2019 | 274 SCZ | BNSS | GAF | Regression | • MAP predicted the global functioning • EXP did not predict the global functioning |

| Cuesta et al23 | 2020 | 98 SCZ 50 HC |

CAINS | GAF; WHODAS; PSP; QLS; SLOF | Correlation | • MAP was correlated with functioning • EXP was correlated with functioning |

| Okada et al24 | 2020 | 107 SCZ | BNSS | SFS | SEM | • MAP was directly linked with social functioning • EXP was indirectly linked with social functioning |

| Galderisi et al26 | 2018 | 740 SCZ | BNSS | SLOF | Network analysis | • MAP was significantly correlated with SLOF work skills and interpersonal relationship subscales • EXP was correlated with SLOF everyday life skills subscale |

| Chang et al27 | 2020 | 323 FEP | SANS | RFS; SF-12 | Network analysis | • MAP was strongly correlated with social functioning • EXP was weakly correlated with social functioning • MAP played the most central role in the network |

Note: SCZ, Schizophrenia patients; FEP, First-episode patients with schizophrenia; HC, Healthy controls; SEM, Structural Equation Modeling; PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SANS, the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; CAINS, the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms; BNSS, the Brief Negative Symptom Scale; MAP, Motivation and Pleasure factor of CAINS; EXP, Expressivity factor of CAINS; CAF, Comprehensive Assessment of Functioning Interview; RFS, the Role Functioning Scale; LOF, the Level of Function Scale; QLS, the Heinrichs–Carpenter Quality of Life Scale; SLOF, the Specific Levels of Functioning; PSP, Personal and Social Performance scale; SSPA, the Social Skills Performance Assessment; GAF, Global Assessment of Functioning; SFS, Social Functioning Scale; WHODAS, WHO Disability Assessment Schedule; SF-12, Short form-12 Health Survey.

Contrary to traditional models which conceptualized symptoms as manifestations of a common underlying disorder, the network approach conceptualizes mental disorders as complex dynamic systems of interacting symptoms.28–30 Network analysis is a data-driven approach which does not require any a priori hypothesis regarding the causal relationship among different variables,28 and therefore can circumvent the inherent limitations of traditional analyses (such as structural equation modeling) which require a priori assumption of causality. As such, network analysis offers promise to unveil the complex interplay between psychopathology and social functioning in SCZ patients. Moreover, network analysis could estimate and visualize the overall patterns of interrelationship among variables as network structures, and generate useful indexes to assess the centrality of each variable.29, 31 For instance, a recent network analysis study32 found that the node of avolition was highly central when SCZ patients were receiving placebo, but the centrality indices of this node reduced when SCZ patients were receiving roluperidone. As such, network analysis suggested potential intervention targets for negative symptoms in SCZ patients.

To date, only Chang et al27 and Galderisi et al26 have utilized network analysis to investigate the interrelationships among psychopathological symptoms, illness-related variables and social functioning in SCZ patients. In their studies,26,27 the MAP and EXP factors exhibited different connection patterns with social functioning. Furthermore, MAP deficits played the most central role in the network in Chang et al 's study.27 However, several unresolved issues remained. First, only a few studies26,27 utilized the well-defined negative symptom domains of the MAP and EXP factors as nodes in the network. Second, in Chang et al's study,27 only the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)33 was used, but first-generation negative symptom scales might have conflated attention and cognitive impairments as negative symptoms.2 The second-generation negative symptom scales such as the CAINS6 and the BNSS34 are more appropriate for studying the relationship of the MAP and EXP deficits with social functioning. Third, the effects of illness-related variables, such as illness duration and antipsychotic side effects, were not taken into consideration in Galderisi et al's study.26 Finally, although gender difference in negative symptoms and social functioning in SCZ patients has consistently been reported,35 few studies investigated possible gender difference in the network structure of the MAP and EXP factors and social functioning.

This study therefore attempted to address the previous limitations.13, 15–24, 26, 27 We investigated the interplay between the MAP and EXP deficits, social functioning and other psychopathology using network analysis, and to identify the most central nodes of the resultant network using centrality indices. We also examined which nodes of psychopathological symptoms would strongly influence social functioning using relative importance contribution analyses.36 We used exploratory analyses to investigate the possible gender differences in network structure, as well as the complex interplay between the MAP and EXP deficits, social functioning and other psychopathology at the “symptom-item” level. Based on earlier findings,18, 26, 27 we hypothesized that the MAP rather than the EXP deficits would strongly influence social functioning after controlling for the effects of other variables. We also hypothesized that the MAP deficits would account for a higher proportion of variability of social functioning compared with other nodes, supporting its predicting validity for social functional outcomes in SCZ patients.

Methods

Participants

Two-hundred and sixty-nine SCZ outpatients were recruited from the West Kowloon Psychiatric Centre (WKPC) and Castle Peak Hospital (CPH) in Hong Kong. All participants met the diagnosis of SCZ based on the criteria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).37 The details of eligibility criteria and ethics committee approval are shown in Supplementary Materials. All participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

The Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS)6.

The CAINS is a 13-item interview-based rating scale, covering the MAP and the EXP factors. The MAP factor comprises 9 items assessing participants’ deficits in social, vocational and recreational aspects. The EXP factor comprises 4 items assessing emotion expression, including speech, vocal prosody, body gestures and facial expressions. Each item is rated on a Likert scale, ranged from 0 (no impairment) to 4 (severe deficit). Higher scores indicate greater severity of negative symptoms. We used the Chinese version of the CAINS, which has high internal reliability (the Omega values for the MAP factor, the EXP factor, and the CAINS total score were 0.87, 0.94 and 0.91 respectively), and good divergent and convergent validity in clinical populations.7,38

The Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS)39.

The SOFAS is a clinician-rated scale for evaluating participants’ ability of independence in terms of daily living, social and role functioning. The score on SOFAS ranged from 0 to 100, based on a semi-structured interview. Higher scores indicate better social functioning at the time of assessments. The SOFAS has been shown to have high validity and reliability in various clinical populations.40

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)41.

The PANSS was used to assess SCZ patients’ psychopathology. In this study, we generated the positive, depressive, disorganized and excited symptoms, which were derived by the sum of specific PANSS items (see table 2 footnote) based on the consensus five-factor model of the PANSS proposed by Wallwork et al.42 The Omega values of the PANSS-positive, depressive, disorganized and excited symptoms ranged from 0.43 to 0.71 in our sample. The five-factor model of PANSS has been validated in the Chinese setting with good convergent validity.43,44

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics in SCZ Patients [M (SD)]

| Male (n = 135) |

Female (n = 134) |

Total (n = 269) |

χ

2

/t

(df = 267) |

p | φ 2/Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment status (employ/unemployed) | 77/58 | 63/71 | 140/129 | 2.706 | 0.100 | 0.100 |

| Age (years) | 38.49 (11.54) | 39.09 (11.30) | 38.79 (11.40) | −0.431 | 0.667 | −0.053 |

| Length of education (years) | 12.64 (4.24) | 13.52 (4.24) | 13.08 (4.25) | −1.705 | 0.089 | −0.208 |

| Duration of illness (years) | 13.09 (10.09) | 12.45 (9.76) | 12.77 (9.91) | 0.526 | 0.599 | 0.064 |

| Medication dose (CPZ (mg/d)) | 455.52 (303.50) | 388.89 (259.03) | 422.33 (283.67) | 1.936 | 0.054 | 0.236 |

| SOFAS | 65.96 (16.18) | 71.87 (16.71) | 68.91 (16.68) | −2.947 | 0.003 | −0.359 |

| CAINS | ||||||

| Motivation and pleasure factor | 17.28 (6.66) | 13.83 (6.64) | 15.56 (6.86) | 4.261 | <0.001 | 0.519 |

| Expressivity factor | 5.20 (4.23) | 2.91 (3.25) | 4.06 (3.94) | 4.980 | <0.001 | 0.412 |

| Total score | 22.48 (10.04) | 16.74 (8.71) | 19.62 (9.82) | 5.008 | <0.001 | 0.606 |

| PANSS | ||||||

| Positive symptoms a | 5.19 (2.12) | 5.13 (1.85) | 5.16 (1.99) | 0.210 | 0.834 | 0.030 |

| Disorganized symptoms a | 4.63 (1.90) | 4.31 (1.65) | 4.48 (1.78) | 1.458 | 0.146 | 0.180 |

| Excited symptoms a | 4.43 (1.40) | 4.22 (0.73) | 4.33 (1.12) | 1.515 | 0.131 | 0.188 |

| Depressive symptoms a | 3.19 (0.72) | 3.49 (1.28) | 3.34 (1.05) | −2.303 | 0.022 | −0.289 |

| SAS | 0.54 (1.27) | 0.62 (1.22) | 0.58 (1.24) | −0.519 | 0.604 | −0.064 |

| BARS | 0.41 (0.90) | 0.22 (0.71) | 0.31 (0.81) | 1.935 | 0.054 | 0.234 |

Note: p < 0.05 are bold. SCZ, schizophrenia; M, Mean; SD, Standard Deviation; CPZ, Chlorpromazine equivalents; SOFAS, the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; CAINS, the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms; PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SAS, the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effects Scale; BARS, the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale.

a The PANSS-positive symptom = composite score of Items P1, P3, P5 and G9; The PANSS disorganized symptom = the composite score of Items P2, N5 and G11; The PANSS-excited symptom = The composite score of Items P4, P7, G8 and G14; The PANSS-depressive symptom score = the composite score of Items G2, G3 and G6.

Extrapyramidal Side Effects.

The Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effects Scale (SAS)45 and the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale (BARS)46 were administrated to evaluate the severity of extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic medications.

Data Analysis

We calculated the mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis and frequency of all the variables. Our sample did not have any non-response or missing data, and all participants’ data (N = 269) were used for subsequent analyses. Gender difference in demographics and clinical symptoms were examined using the SPSS version 23.0.47 The variables were entered as nodes in network analysis, ie, the SOFAS, the MAP and EXP factors of the CAINS, the positive, disorganized, depressive and excited domains of the PANSS, the SAS, the BARS and illness duration. Network analysis and estimation of the centrality indices were conducted using the R statistical software version 4.0.0,48 and R package qgraph version 1.6.549 and R package bootnet version 1.4.3.50

Given that the ten variables in our sample did not follow a normal distribution, we first applied non-parametric transformations to the variables using the R package huge version 1.3.451 prior to network estimation. Partial correlation analyses were then conducted to estimate the correlations between all pairs of nodes, while controlling for the influence of the remaining variables. To shrink the spurious connections between the nodes and to estimate a sparse model, the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) statistical regularization technique,52 combining with Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) model selection, which set a tuning hyperparameter at 0.5, was adopted. The EBIC is a goodness-of-fit measure for model selection.53,54 The resultant network comprised the nodes and “edges” (the correlations between different nodes). The stronger the correlations between two nodes, the thicker will be the edges, and the closer the proximity of the nodes. The resultant network is displayed using the Fruchterman–Reingold algorithm55 (see Supplementary Figure S1).

To further elucidate the effects of clinical symptoms on social functioning in SCZ patients, we visualized the network structure as a flow diagram using the flow function of R package qgraph.49 The flow diagram was constructed using the Reingold–Tilford graph layout algorithm,56 which placed the node of social functioning on the left, and created a vertical network indicating which edges would be directly or indirectly related to the node of social functioning.

For each node, we computed three network centrality indices (ie, strength, closeness and betweenness).57–59 Higher values of the centrality indices indicate higher centrality of a node in the resultant network. We also computed the expected influence (EI)60 and predictability centrality61,62 estimates. The predictability would be visualized as a ring-shaped pie chart around a given node.

In addition, we followed Epskamp et al's50 guidance to estimate the network accuracy and stability. The details for centrality indices and stability estimation can be found in Supplementary Materials. The non-parametric bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) of the difference between each pair strength centrality and edge-weights were calculated (see Supplementary Figures S4 and S5).

Furthermore, to quantitatively assess the extent of contribution from each variable to social functioning in SCZ patients, and to identify the nodes which better predict social functioning, we conducted the linear regression analysis. We first confirmed that our data did not have problems of multicollinearity, and the residuals were normally distributed. Then, the R package relaimpo version 2.236 was used to estimate the relative contribution of each variable to social functioning. This method could tease out the partitions of the explained variance among all the variables, considering the direct effect of each variable on social functioning, and the indirect effect of other variables.

To compare the overall network structure and global strength invariance of the male participants (n = 135) and the female participants (n = 134), we conducted Network Comparison Test while accounting for multiple testing of many edges, using R package Network Comparison Test version 2.2.1.63 The Network Comparison Test is a permutation test to examine the gender difference by repeatedly rearranging participants from each network (1,000 iterations).

Finally, although our sample size was modest, we conducted an exploratory network analysis at the “symptom-item” level, to supplement our findings at the “symptom-dimension” level. In the network analysis at the “symptom-item” level, each item of the CAINS and the PANSS was used as nodes to examine the interplay between individual symptoms, the SOFAS, the SAS, the BARS and illness duration. The procedures were identical to the network analysis conducted at the “symptom-dimension” level.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 shows the demographics and clinical characteristics of our participants. The gender differences in demographics were non-significant (ps > 0.05). Regarding the clinical characteristics, compared with female participants, male participants exhibited significantly lower levels of social functioning and depressive symptoms, but higher levels of negative symptoms. The male and female SCZ participants did not differ in positive, disorganized and excited symptoms of the PANSS.

Network Structure at the Symptom-dimension Level

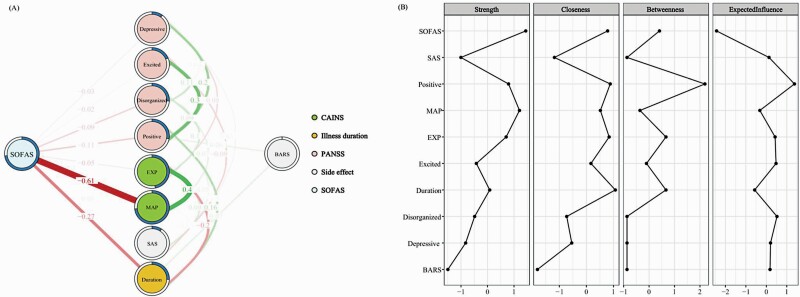

The flow network presented in figure 1A emphasized the link between social functioning and other nodes of interest. Among the psychopathological nodes, our results showed moderate positive connections between the MAP and the EXP factors, between the PANSS-positive symptoms and the PANSS-excited symptoms, and between the PANSS-positive symptoms and the PANSS-depressive symptoms. Moreover, our results showed a negative connection between the EXP factor and illness duration.

Fig. 1.

(A) Regularized partial correlation flow network of social functioning, negative symptoms, other psychopathology and illness-related variables at the “symptom-dimension” level in SCZ patients (N = 269). Each node represents a variable. Each edge represents the partial correlation between two nodes controlled for all other nodes. The value of each edge represents the strength of the correlations. Green edges (for the online version) or positive edge values (for the print version) represent positive associations, whereas red edges (for the online version) or negative edge values (for the print version) represent negative associations. Thicker edges (positive and negative) signify stronger partial correlations. The pie chart surrounding each node represents node predictability. The value of each edge represents the strength of the correlations. (B) The standardized centrality estimates of the network in SCZ patients.Note: SCZ, schizophrenia; SOFAS, the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; CAINS, the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms; MAP, Motivation and Pleasure factor of the CAINS; EXP, Expressivity factor of the CAINS; PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SAS, the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effects Scale; BARS, the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale.

After accounting for the interrelationships between psychopathological nodes, the resultant network suggested that social functioning was strongly (negatively) linked to the MAP factor, but moderately linked to illness duration, and weakly linked to the PANSS-positive and disorganized symptoms.

Results of Centrality Indices

Figure 1B shows the centrality indices of each node in the resultant network. Importantly, social functioning showed the highest strength, followed by the MAP factor. The PANSS-positive symptoms and illness duration showed relatively high closeness and betweenness centrality indexes. The PANSS-positive symptoms showed the highest EI. On the other hand, the nodes of MAP factor and social functioning were relatively predictable in the resultant network. The centrality, predictability and EI values of each node are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Network Stability and Accuracy

The network accuracy and the stability of centrality indices are presented in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3. The correlation stability (CS) coefficients for strength and EI were 0.751 and 0.751 respectively, suggesting sufficient stability. However, the CS coefficients for closeness and betweenness were 0.048 and 0.048 respectively, falling below the recommended minimum threshold (ie, p > 0.25).

Relative Importance for Social Functioning

The linear regression model found that the MAP and EXP factors, together with other clinical characteristics, accounted for 72.97% of the variance of social functioning (F(9, 259) = 77.70, p < 0.001). Table 3 summarizes the linear regression and relative contribution of psychopathological nodes to social functioning. The MAP factor, illness duration and the PANSS-positive symptoms significantly predicted social functioning in SCZ participants. In contrast, the remaining nodes of interest did not significantly predict social functioning (ps > 0.05).

Table 3.

Linear regression and relative contribution of each variable on social functioning

| Independent variables | Unstandardized beta | Standardized beta | SE |

t

(df = 259) |

p | Explained R2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAP | −1.814 | −0.746 | 0.044 | −16.957 | <0.001 | 44.782 |

| EXP | 0.056 | 0.013 | 0.045 | 0.294 | 0.769 | 8.917 |

| Illness duration (years) | −0.416 | −0.247 | 0.034 | −7.160 | <0.001 | 8.938 |

| SAS | −0.022 | −0.002 | 0.034 | −0.048 | 0.962 | 0.926 |

| BARS | −0.939 | −0.046 | 0.033 | −1.402 | 0.162 | 0.419 |

| PANSS-Positive symptoms | −0.786 | −0.094 | 0.038 | −2.460 | 0.015 | 3.151 |

| PANSS-Excited symptoms | −0.657 | 0.041 | 0.036 | 1.142 | 0.255 | 0.683 |

| PANSS-Disorganized symptoms | 0.616 | −0.070 | 0.037 | −1.877 | 0.062 | 4.551 |

| PANSS-Depressive symptoms | −0.377 | −0.024 | 0.035 | −0.683 | 0.495 | 0.605 |

Note: p < 0.05 are bold. SE, Standard Error; CAINS, the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms; MAP, Motivation and Pleasure factor of the CAINS; EXP, Expressivity factor of the CAINS; SAS, the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effects Scale; BARS, the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale; PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Moreover, the MAP factor accounted for 44.78% of the variance of social functioning, which was statistically higher than the contribution from other variables. The bootstrapped CIs for the difference are shown in Supplementary Table S4. The MAP factor played the most important role in determining SCZ participants’ social functioning, after controlling for the interplay between other nodes.

Gender Difference in Overall Network Invariance and Global Strength

The Network Comparison Test did not find any difference between male and female participants in terms of the overall network invariance (ie, the Maximum difference in edge-weights was 0.216, p = 0.385) and global strength (ie, the Strength difference was 0.200, p = 0.858) (see Supplementary Figure S6).

Network Structure at the “symptom-item” Level

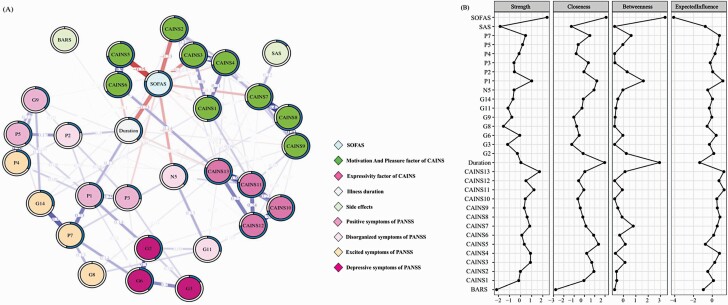

The resultant network is shown in figure 2A. Regarding the nodes of the CAINS items, our resultant network showed that individual items (related to social, vocational and recreational aspects) belonging to the MAP factor were connected together (edge value = 0–0.499), while individual items belonging to the EXP factor were closely correlated with each other (edge value = 0.190–0.363). Importantly, the CAINS items denoting (1) social motivation and pleasure, and (2) vocational motivation and pleasure were closely connected to the SOFAS, whereas individual items belonging to the CAINS EXP factor and the PANSS items lied more distal from the node of SOFAS. Together, the results at the “symptom-item” level concur with the results at the “symptom-dimension” level. Moreover, in the item-level network, illness duration was moderately linked to the SOFAS.

Fig. 2.

(A) Regularized Partial Correlation Network of social functioning, negative symptoms, other psychopathology and illness-related variables at the “symptom-item” level in SCZ patients (N = 269). Each node represents a variable. The value of each edge represents the strength of the correlations. Each edge represents the partial correlation between two nodes controlled for all other nodes. Blue edges (for the online version) or positive edge values (for the print version) represent positive associations, whereas red edges (for the online version) or negative edge values (for the print version) represent negative associations. Thicker edges (positive and negative) signify stronger partial correlations. The pie chart surrounding each node represents node predictability. The value of each edge represents the strength of the correlations. (B) The standardized centrality estimates of the network in SCZ patients.Note: SCZ, schizophrenia; SOFAS, the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale; CAINS, the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms; SAS, the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effects Scale; BARS, the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale; PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

The centrality indices of the item-level network are shown in figure 2B. The SOFAS showed the highest central role in the network, and a relatively high predictability. The centrality, predictability and EI values of each node are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

The network accuracy and the stability of centrality indices are shown in Supplementary Figures S7 and S8. The CS coefficients for strength, betweenness, closeness and EI were 0.673, 0.283, 0 and 0.673 respectively. Taken together, the results of network analysis at both the domain-level and symptom item-level converged to support the important role of the MAP factor in determining social functioning in SCZ participants. Compared to the item-level network, network at domain-level was relatively more stable.

Discussion

This network analysis study utilized a state-of-the-art instrument to measure negative symptoms, and examined the complex interplay between psychopathology, illness-related characteristics and social functioning in a reasonably large sample of SCZ patients. We specifically investigated the effects of the MAP and EXP factors on social functioning, while accounting for medication side effects, illness duration and other psychopathology. Together, our findings supported that MAP deficits play a pivotal role in determining SCZ patients’ social functioning, and the MAP factor may constitute an important intervention target.

At the “symptom-dimension” level, psychopathological nodes did not show a well-formed cluster. The MAP and the EXP factors were moderately interconnected with each other, but both were weakly connected to other psychopathological nodes. Moreover, the nodes of PANSS-positive and excited symptoms were connected more strongly than the interrelationship between other nodes of the PANSS. Manuela et al64 suggested that the dimensions of negative symptoms and other clinical symptoms are relatively discrete, mirroring the heterogeneity of psychopathology in psychosis. Regarding the link between psychopathological nodes and social functioning, our resultant network at the “symptom-dimension” level strongly supported that social functioning was negatively correlated with the MAP factor after accounting for the complex interplay between all the nodes, consistent with previous network analysis studies.26,27 In addition, social functioning was moderately linked to illness duration, and weakly connected with the PANSS-positive and disorganized symptoms, concurring with previous findings.21, 27 Our resultant network at the “symptom-item” level demonstrated a very similar network pattern, with a clear cluster of nodes comprising social functioning and the individual items of the MAP factor. Taken together, this study provided consistent evidence to support the close relationship between the MAP factor and social functioning in SCZ patients.

In the resultant network at the “symptom-dimension” level, the nodes of social functioning and the MAP factor showed high values of strength centrality, implicating important roles in the network. These two nodes also showed high values of predictability, indicating that the majority of their variance could be accounted for by the surrounding nodes of the network. Regarding the indices of closeness and betweenness, the PANSS-positive symptoms and illness duration showed relatively high values. However, the closeness and betweenness centrality indices did not reach a stable coefficient in bootstrapping analysis, therefore these results should be interpreted cautiously. Among various indices, strength is the most important and reliable parameter for a node in network analysis examining psychopathology, and has the highest diagnostic prediction ability in longitudinal research.31, 65 Therefore, our study and previous studies27, 32 both support that the MAP factor is a potential intervention target to alleviate other symptoms and to improve social functioning.

The node with highest EI was the PANSS-positive symptoms, though the nodes of social functioning and MAP factor had high strength centrality. The presence of negative edges in the network may result in the divergent results between EI and the strength index. EI is considered a better parameter for identification of intervention targets, particularly in networks having many negative edges.60 Therefore, the PANSS-positive symptoms may be another intervention target for improving SCZ patients’ social functioning.

Furthermore, our relative importance analyses showed that the MAP factor accounted for the largest proportion of the variability of social functioning in the network. Accumulating evidence17, 18, 27 suggests that the MAP factor is one of the strongest determinants of SCZ patients’ social functioning. Impaired motivation usually persists despite pharmacological treatments, and predicts functional outcomes in SCZ patients.18, 66 Our findings suggested that MAP deficits, rather than other psychopathology, might be an important intervention target for enhancing SCZ patient’s social functioning and functional outcomes. In fact, accumulating neurobiological evidence suggests that SCZ-associated impairments of reward-related processing is related to altered frontal-striatal circuits, underpinning the MAP deficits.8, 67 Future network analysis studies should include additional neuropsychological variables related to reward processing (eg, cost-benefit computation) as nodes, to further examine the relative importance of the MAP factor and its neuropsychological underpinnings for social functioning, and to further investigate the complex interplay between psychopathology-cognition-social functioning in SCZ patients.

Apart from the MAP factor, illness duration also played an important role in predicting social functioning in our sample, consistent with previous evidence.25 SCZ patients having long illness duration likely exhibit severe cognitive deficits and poor treatment response.68 Given that illness duration is associated with many adversities in SCZ patients, which may be confounds on social functioning, research should include more nodes (eg, neurocognitive impairments) in network analysis.

In contrast to the MAP factor, the EXP factor showed a very weak link with social functioning in our network, implicating that the MAP-EXP differentiation has significant impact on social functioning. Moreover, at the “symptom-item” level, our resultant network showed that the individual items belonging to the MAP factor would not form clusters with the individual items belonging to the EXP factor. This further supports the factor-structure of negative symptoms in SCZ patients.4, 69 Consistent with Chang et al's study,27 we found that the role of EXP deficits on social functioning was weak. Several reasons may explain this observation. First, there may be an indirect pathway from the EXP factor to social functioning through the MAP factor.24 Second, the CAINS might not be an ideal instrument to comprehensively assess EXP deficits,70 further research should include other measurements for EXP deficits. Third, several studies found that EXP deficits significantly linked with everyday life skills, whereas MAP deficits linked with interpersonal relationships and work skills.21, 26 Accumulating neuroimaging evidence support the existence of distinct neural mechanisms subserving these two dimensions, such that EXP deficits may be related to abnormalities in the cortical motor area and the frontal-limbic circuits, whereas MAP deficits may be related to abnormalities in the frontal-striatal circuits.8 In the light of these neuroimaging findings, it is understandable that the MAP and EXP factors may affect social functioning differently. Future research should investigate the role of EXP deficits on social functioning using additional measures based on behavior-coding strategies,71 and automated computer-based acoustic analysis.70 Consistent with prior studies,35 male SCZ patients exhibited more severe negative symptoms and poorer social functioning than female SCZ patients. However, our gender-stratified subsample did not show any significant difference in terms of the overall network structure and global strength, consistent with a recent study.27

Our study has several limitations. First, our findings have not been replicated using another independent sample. Poor replicability and unstable centrality of the partial correlation network have recently been reported.72,73 Second, our cross-sectional design precluded the possibility of inferring causality among the variables of the network. Future research should gather longitudinal data to examine how the network structure between negative symptoms and social functioning would evolve along the course of illness. Third, our sample size may not be large enough, resulting in the relatively low stability of the centrality indices of closeness and betweenness, and limiting the power of our exploratory “symptom-item” level network analysis. Fourth, we did not include other variables known to influence social functioning in SCZ patients, such as premorbid functioning,27 neurocognitive74 and social cognitive impairments19 and internalized stigma.26 Besides, socioeconomic status (eg, income) may be potential confounds. However, recent studies found psychopathological symptoms, rather than cognitions, playing central role in the psychopathology-cognition network.75 Cognitive variables may not be directly connected to functional variables, and their connections may be mediated through disorganized symptoms.26,27 Lastly, we only used the SOFAS to measure social functioning. It is possible that several aspects of the CAINS MAP factor may overlap with the SOFAS, because both instruments take SCZ patients’ observable behaviors into the consideration. However, the ratings of the CAINS MAP items are not only based on SCZ patients’ actual behavior, but also their internal motivation, interests and emotions. Moreover, SOFAS is a measure of occupational and social domains and is not specifically capturing social functioning. Future research should employ multimodal measures, including self-report scales and performance-based assessments, to comprehensively quantify social functioning.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study showed that MAP factor appeared to link strongly to social functioning, after accounting for the effects of other psychopathology. The MAP factor explained a high proportion of variance of social functioning in our SCZ sample. Taken together, our findings apparently support the MAP factor as one promising intervention target to improve the social and functional outcomes of SCZ patients.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study was supported by the CAS Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology and the Phillip K.H. Wong Foundation. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Contributor Information

Hui-Xin Hu, Neuropsychology and Applied Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory, CAS Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; Department of Psychology, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China.

Wilson Y S Lau, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China.

Eugenia P Y Ma, Department of Adult Psychiatry, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China.

Karen S Y Hung, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China.

Si-Yu Chen, Neuropsychology and Applied Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory, CAS Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; Department of Psychology, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China.

Kin-Shing Cheng, Department of Adult Psychiatry, Kwai Chung Hospital, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China.

Eric F C Cheung, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China.

Simon S Y Lui, Castle Peak Hospital, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China; Department of Psychiatry, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China.

Raymond C K Chan, Neuropsychology and Applied Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory, CAS Key Laboratory of Mental Health, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; Department of Psychology, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China.

References

- 1. Carpenter WT, Buchanan RW. Schizophrenia. New Engl J Med. 1994;330(10):681–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kirkpatrick B, Fenton WS, Carpenter WT, Marder SR. The NIMH-MATRICS consensus statement on negative symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):214–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blanchard JJ, Cohen AS. The structure of negative symptoms within schizophrenia: implications for assessment. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(2):238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Messinger JW, Trémeau F, Antonius D, et al. Avolition and expressive deficits capture negative symptom phenomenology: Implications for DSM-5 and schizophrenia research. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(1):161–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Strauss GP, Ahmed AO, Young JW, Kirkpatrick B. Reconsidering the latent structure of negative symptoms in schizophrenia: a review of evidence supporting the 5 consensus domains. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45(4):725–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kring AM, Gur RE, Blanchard JJ, Horan WP, Reise SP. The Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS): final development and validation. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(2):165–172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xie DJ, Shi HS, Lui SSY, et al. Cross cultural validation and extension of the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS) in the Chinese Context: evidence from a spectrum perspective. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(suppl_2):S547–S555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bègue I, Kaiser S, Kirschner M. Pathophysiology of negative symptom dimensions of schizophrenia – current developments and implications for treatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;116:74–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ventura J, Hellemann GS, Thames AD, Koellner V, Nuechterlein KH. Symptoms as mediators of the relationship between neurocognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2–3):189–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rabinowitz J, Levine SZ, Garibaldi G, Bugarski-Kirola D, Berardo CG, Kapur S. Negative symptoms have greater impact on functioning than positive symptoms in schizophrenia: analysis of CATIE data. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):147–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ventura J, Subotnik KL, Gitlin MJ, et al. Negative symptoms and functioning during the first year after a recent onset of schizophrenia and 8 years later. Schizophr Res. 2015;161(2–3):407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Foussias G, Remington G. Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: Avolition and Occam’s Razor. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36(2):359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Strauss GP, Horan WP, Kirkpatrick B, et al. Deconstructing negative symptoms of schizophrenia: avolition–apathy and diminished expression clusters predict clinical presentation and functional outcome. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(6):783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Galderisi S, Bucci P, Mucci A, et al. Categorical and dimensional approaches to negative symptoms of schizophrenia: focus on long-term stability and functional outcome. Schizophr Res. 2013;147(1):157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fervaha G, Foussias G, Agid O, Remington G. Motivational and neurocognitive deficits are central to the prediction of longitudinal functional outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(4):290–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Robertson BR, Prestia D, Twamley EW, Patterson TL, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Social competence versus negative symptoms as predictors of real world social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;160(1–3):136–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rocca P, Montemagni C, Zappia S, Piterà R, Sigaudo M, Bogetto F. Negative symptoms and everyday functioning in schizophrenia: a cross-sectional study in a real world-setting. Psychiatry Res. 2014;218(3):284–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fervaha G, Foussias G, Agid O, Remington G. Motivational deficits in early schizophrenia: prevalent, persistent, and key determinants of functional outcome. Schizophr Res. 2015;166(1–3):9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kalin M, Kaplan S, Gould F, Pinkham AE, Penn DL, Harvey PD. Social cognition, social competence, negative symptoms and social outcomes: inter-relationships in people with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;68:254–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harvey PD, Khan A, Keefe R. Using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) to define different domains of negative symptoms: prediction of everyday functioning by impairments in emotional expression and emotional experience. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2017;14(11-12):18–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rocca P, Galderisi S, Rossi A, et al. Disorganization and real-world functioning in schizophrenia: results from the multicenter study of the Italian Network for Research on Psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2018;201:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ang MS, Rekhi G, Lee J. Validation of the Brief Negative Symptom Scale and its association with functioning. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cuesta MJ, Sánchez-Torres AM, Lorente-Omeñaca R, Moreno-Izco L, Peralta V, SegPEPs Group. Cognitive, community functioning and clinical correlates of the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS) in psychotic disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020; doi: 10.1007/s00406-020-01188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Okada H, Hirano D, Taniguchi T. Single versus dual pathways to functional outcomes in schizophrenia: role of negative symptoms and cognitive function. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2020;23:100191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dickerson F, Boronow JJ, Ringel N, Parente F. Social functioning and neurocognitive deficits in outpatients with schizophrenia: a 2-year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 1999;37(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Galderisi S, Rucci P, Kirkpatrick B, et al. Interplay among psychopathologic variables, personal resources, context-related factors, and real-life functioning in individuals with schizophrenia: a network analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chang WC, Wong CSM, Or PCF, et al. Inter-relationships among psychopathology, premorbid adjustment, cognition and psychosocial functioning in first-episode psychosis: a network analysis approach. Psychol Med. 2020;50(12):2019–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:91–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Borsboom D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Borsboom D, Cramer AOJ, Kalis A. Brain disorders? not really: why network structures block reductionism in psychopathology research. Behav Brain Sci. 2018;42:e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McNally RJ. Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behav Res Ther. 2016;86:95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Strauss GP, Zamani Esfahlani F, Sayama H, et al. Network analysis indicates that avolition is the most central domain for the successful treatment of negative symptoms: evidence from the Roluperidone Randomized Clinical Trial. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46(4):964–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155(S7):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kirkpatrick B, Strauss GP, Nguyen L, et al. The brief negative symptom scale: psychometric properties. Schizophr bull. 2011;37(2):300–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ochoa S, Usall J, Cobo J, Labad X, Kulkarni J. Gender differences in schizophrenia and first-episode psychosis: a comprehensive literature review. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2012;2012:916198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tonidandel S, LeBreton JM. Relative importance analysis: a useful supplement to regression analysis. J Bus Psychol. 2011;26:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 37. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chan RCK, Shi C, Lui SSY, et al. Validation of the Chinese version of the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS): a preliminary report. Front Psychol. 2015;6:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(9):1148–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(4):323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kay SR, Fisbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wallwork RS, Fortgang R, Hashimoto R, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1–3):246–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jiang J, Sim K, Lee J. Validated five-factor model of positive and negative syndrome scale for schizophrenia in Chinese population. Schizophr Res. 2013;143(1):38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fong TC, Ho RT, Wan AH, Siu PJ, Au-Yeung FS. Psychometric validation of the consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;62:204–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970; 212:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. IBM. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS Base Version. Armonk, NY: IBM Corporation; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 48. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Version 4.0.0 . 2016. https://www.r-project.org/

- 49. Epskamp S, Cramer AOJ, Waldorp LJ, Schmittmann VD, Borsboom D. qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(4):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Epskamp S, Borsboom D, Fried EI. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: a tutorial paper. Behav Res Methods. 2017;50(1):195–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu H, Lafferty J, Wasserman L. The nonparanormal: semiparametric estimation of high dimensional undirected graphs. J Mach Learn Res. 2009;10:2295–2328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Friedman JH, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics. 2008;9(3):432–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen J, Chen Z. Extended Bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika. 2008;95(3):759–771. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Foygel R, Drton M. Extended Bayesian information criteria for Gaussian graphical models. In: Lafferty JD, Williams CKI, Shawe-Taylor J, Zemel RS, Culotta A, eds. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 23. New York, NY: Curran Associates, Inc; 2010:604–612. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fruchterman TMJ, Reingold EM. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw Pract Exp. 1991;21(11):1129–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Reingold E, Tilford J. Tidier drawing of trees. IEEE T Software Eng. 1981;7(2):223–228. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Barrat A, Barthélemy M, Pastor-Satorras R, Vespignani A. The architecture of complex weighted networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3747–3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Boccaletti S, Latora V, Moreno Y, Chavez M, Hwang DU. Complex networks: structure and dynamics. Phys Rep. 2006;424:175–308. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Opsahl T, Agneessens F, Skvoretz J. Node centrality in weighted networks generalizing degree and shortest paths. Soc Networks. 2010;32(3):245–251. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Robinaugh DJ, Millner AJ, McNally RJ. Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125(6):747–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Haslbeck JMB, Waldorp LJ. mgm: Structure Estimation for Time-Varying Mixed Graphical Models in high-dimensional Data.2016; https://arxiv.org/abs/1510.06871v8

- 62. Haslbeck JMB, Fried EI. How predictable are symptoms in psychopathological networks? A reanalysis of 18 published datasets. Psychol Med. 2017;47(16):2767–2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. van Borkulo C, Epskamp S, Jones P, Haslbeck J, Millner A. NetworkComparisonTest. R Package Version 2.2.1. CRAN. Package ‘NetworkComparisonTest’. 2016; https://cran.microsoft.com/web/packages/NetworkComparisonTest/NetworkComparisonTest.pdf

- 64. Manuela R, Levine SZ, Arsime D, et al. Association between symptom dimensions and categorical diagnoses of psychosis: a cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Robinaugh DJ, Hoekstra RHA, Toner ER, Borsboom D. The network approach to psychopathology: a review of the literature 2008–2018 and an agenda for future research. Psychol Med. 2020;50(3):353–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lutgens D, Joober R, Iyer S, et al. Progress of negative symptoms over the initial 5 years of a first episode of psychosis. Psychol Med. 2019;49(1):66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kring AM, Barch DM. The motivation and pleasure dimension of negative symptoms: Neural substrates and behavioral outputs. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(5):725–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Altamura AC, Serati M, Buoli M. Is duration of illness really influencing outcome in major psychoses? Nord J Psychiatry. 2015;69(6):1685–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liemburg E, Castelein S, Stewart R, et al. Two subdomains of negative symptoms in psychotic disorders: established and confirmed in two large cohorts. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(6):718–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cohen AS, Elvevåg B. Automated computerized analysis of speech in psychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27(3):203–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. de Boer JN, Voppel AE, Brederoo SG, et al. Acoustic speech markers for schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: a diagnostic and symptom-recognition tool. Psychol Med. 2021:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Forbes MK, Wright AGC, Markon KE, Krueger RF. Evidence that psychopathology symptom networks have limited replicability. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017;126(7):969–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Hallquist MN, Wright AGC, Molenaar PCM. Problems with centrality measures in psychopathology symptom networks: why network psychometrics cannot escape psychometric theory. Multivariate Behav Res. 2021;56(2):199–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Strassnig MT, Raykov T, O’Gorman C, et al. Determinants of different aspects of everyday outcome in schizophrenia: the roles of negative symptoms, cognition, and functional capacity. Schizophr Res. 2015;165(1):76–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Moura BM, van Rooijen G, Schirmbeck F, et al. A network of psychopathological, cognitive, and motor symptoms in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47(4):915–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.