Abstract

NMDA receptor blockade in rodents is commonly used to induce schizophrenia-like behavioral abnormalities, including cognitive deficits and social dysfunction. Aberrant glutamate and GABA transmission, particularly in adolescence, is implicated in these behavioral abnormalities. The endocannabinoid system modulates glutamate and GABA transmission, but the impact of endocannabinoid modulation on cognitive and social dysfunction is unclear. Here, we asked whether late-adolescence administration of the anandamide hydrolysis inhibitor URB597 can reverse behavioral deficits induced by early-adolescence administration of the NMDA receptor blocker MK-801. In parallel, we assessed the impact of MK-801 and URB597 on mRNA expression of glutamate and GABA markers. We found that URB597 prevented MK-801-induced novel object recognition deficits and social interaction abnormalities in adult rats, and reversed glutamate and GABA aberrations in the prelimbic PFC. URB597-mediated reversal of MK-801-induced social interaction deficits was mediated by the CB1 receptor, whereas the reversal of cognitive deficits was mediated by the CB2 receptor. This was paralleled by the reversal of CB1 and CB2 receptor expression abnormalities in the basolateral amygdala and prelimbic PFC, respectively. Together, our findings show that interfering with NMDA receptor function in early adolescence has a lasting impact on phenotypes resembling the negative symptoms and cognitive deficits of schizophrenia and on glutamate and GABA marker expression in the PFC. Prevention of behavioral and molecular abnormalities by late-adolescence URB597 via CB1 and CB2 receptors suggests that endocannabinoid stimulation may have therapeutic potential in addressing treatment-resistant symptoms.

Keywords: schizophrenia, animal model, NMDA receptor, URB597, CB1, CB2

Introduction

The negative symptoms and cognitive deficits of schizophrenia (SZ) are considered core components of the disorder, precede the emergence of psychosis in late adolescence to early adulthood, and are generally resistant to antipsychotic drug treatment.1,2 Negative symptoms are broadly divided into social and motivational deficits,3 while cognitive abnormalities include specific aberrations in memory, executive function, and attention.4 Several lines of evidence support the association of these abnormalities with a disrupted excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance, ie, disturbed communication between glutamatergic pyramidal neurons and GABAergic interneurons in prefrontal cortex (PFC) and temporal brain regions.5

Glutamate and GABA transmission in PFC reach full maturity in late adolescence to early adulthood,6 and are modulated by several factors including the endocannabinoid (ECB) system.7 The ECB ligand N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide; AEA) is degraded by fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), and acts on the cannabinoid receptors CB1 (CB1r) and in lower affinity CB2 (CB2r). While cannabis use is a risk factor for psychosis in genetically-predisposed individuals,8 enhancing endogenous cannabinoid signalling may lead to a better pharmacological response than currently-prescribed antipsychotics.9,10 The interaction of ECB system components with glutamate and GABA transmission in fronto-hippocampal regions mediates social behavior,11 motivation, and working memory.12 Thus, modulating the ECB system may be particularly beneficial in addressing negative symptoms and cognitive abnormalities relevant to SZ psychopathology.

Rodent studies indicate that NMDA receptor (NMDAr) blockers, which induce SZ-like symptoms in healthy humans13 and exacerbate symptoms in SZ patients,14 lead to behavioral and molecular abnormalities that resemble SZ symptoms, including negative symptoms (eg, social deficits) and cognitive abnormalities (eg, working memory and attentional set shifting deficits).2 Additionally, NMDAr blockade leads to excess glutamate release and reduced GABA marker expression, particularly in temporo-cortical regions.2,15

The FAAH inhibitor URB597 ameliorates MK-801-induced memory impairments16 and PCP-induced social interaction abnormalities,17 but its long-term effects on NMDAr blockade-induced behavioral and glutamate and GABA abnormalities has not been studied. Furthermore, the differential involvement of CB1r and CB2r in URB597's effects on social and cognitive capacities has not been studied.

In the present study we asked whether URB597 treatment in late adolescence reverses the effects of early-adolescence chronic MK-801 treatment on SZ-like social and cognitive deficits, via CB1r and/or CB2r activation. We further assessed changes in mRNA expression of glutamate, GABA, and ECB markers induced by MK-801, and their reversal by URB597, in several brain regions.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Male Sprague Dawley rats (Envigo Laboratories, Jerusalem) were used; female rats were not included since the estrous cycle affects the response to ECB agonists and antagonists,18 necessitating a different experimental design. Experimental procedures were approved by the University of Haifa Ethics and Animal Care Committee (555/18) and comply with NIH guidelines and regulations for minimizing pain and discomfort.

Pharmacological Agents

The noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (MK; dizocilpine; 0.2 mg/kg; Sigma Aldrich, Israel) was dissolved in 0.9% saline (Sal); controls received Sal. URB597 (URB; 0.3 mg/kg; Cayman Chemicals, USA), the CB1r antagonist AM251 (0.3 mg/kg; Cayman Chemicals, USA), and the CB2r antagonist AM630 (1 mg/kg; Cayman Chemicals, USA) were dissolved in vehicle (Veh) solution of 5% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), 5% Tween-80, and 90% saline, prepared on each injection day; controls received Veh. All drugs were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) at 1 ml/kg. Drug doses were based on previous publications.15,19,20

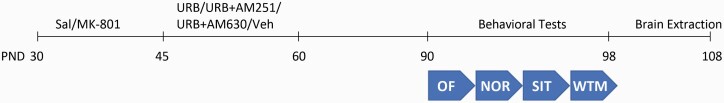

Experimental Design

Figure 1 summarizes the experimental design [see details in supplementary information]. Briefly, rats were randomly divided into 6 groups: Sal+Veh, MK+Veh, Sal+URB, MK+URB, MK+URB+AM251, and MK+URB+AM630. The URB597 administration period was selected based on previously-demonstrated effectiveness of ECB treatment during this time window.21 Behavioral and molecular assessments were performed in adulthood since we were interested in the long-term effects of the drugs rather than the well-studied short-term impact.15,22 A control experiment was conducted in order to examine whether late-adolescence AM251 and AM630 administration on its own induces behavioral effects in saline- or MK-801-treated rats.

Fig. 1.

Experimental procedure timeline. OF = open field test, NOR = novel object recognition task, SIT = social interaction test, WTM = water T-maze.

Behavioral Tests

The open field (OF) test assessed general locomotor function (total distance, cm, divided into 5 min bins) and novelty-induced anxiogenic behavior (time in arena center, first 5 min).24 The Novel Object Recognition (NOR) test, with an inter-trial interval (ITI) of 5 min, was used to measure novelty recognition and working memory.25 We assessed total exploration time (s) and the mean discrimination-index (DI), calculated as (TN = novel object exploration time, TF = familiar object exploration time) in the test phase. The Social Interaction Test (SIT) assessed social behaviors (eg, sniffing, physical touch, climbing) and nonsocial behaviors (eg, self-grooming, remaining alone).26 Time (s) spent on each behavior was measured, and the sociability index was calculated as the time spent engaging in social behaviors divided by the total test time (5 min). The Water T-maze test assessed spatial discrimination and reversal learning.25 In the acquisition (acq) phase, rats were required to reach a platform located in one of the arms. After a probe trial, the platform was moved to the other side for the reversal (rev) phase. The number of trials to reach criterion (5 correct trials) on each phase was recorded. For elaborated testing procedures, see supplementary information.

Gene Expression

The prelimbic (PrL) and infralimbic (IL) mPFC subregions and the basolateral amygdala (BLA) were extracted in the cryostat using 0.5 cm punches. Punch location was verified using the rat brain atlas27 and Nissl staining (see supplementary information for Nissl procedure and figures 3 and 4 for punch location). RNA extraction, cDNA preparation, and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) were performed using standard methodology as previously described24 (see supplementary information for details and primers sequences).

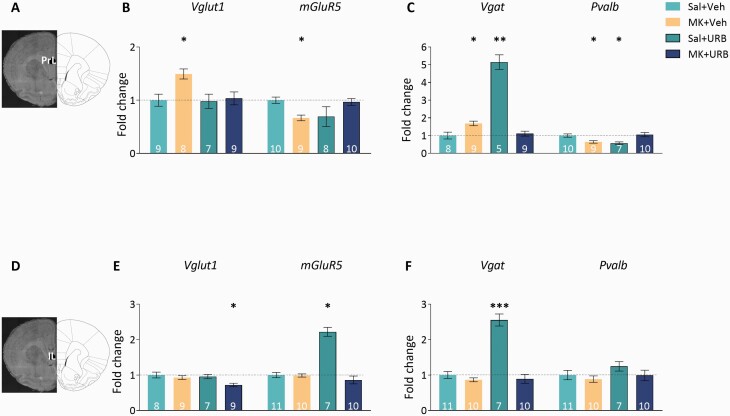

Fig. 3.

The expression of glutamate and GABA markers in the PrL (A–C) and IL (D–F). (A) rat brain atlas illustration (right) and Nissl staining (left) indicating PrL punch location. (B)Vglut1 (left) was upregulated in the MK+Veh group, compared to all other groups, and mGluR5 (right) was downregulated compared to Sal+Veh and MK+URB. (C)Vgat (left) was upregulated and Pvalb (right) was downregulated in the MK+Veh and the Sal+URB groups, compared to Sal+Veh and MK+URB. (D) rat brain atlas illustration (right) and Nissl staining (left) indicating IL punch location. (E)Vglut1 (left) was downregulated in the MK+URB group and mGluR5 (right) was upregulated in the Sal+URB group compared to all other groups. (F)Vgat (left) was upregulated in the Sal+URB compared to all other groups; no group differences were observed in Pvalb expression. Data represent fold change ± SEM. Numbers in bars represent n/group. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, relative to the Sal+Veh group.

Fig. 4.

The expression of ECB receptors in the PrL and BLA. (A) Rat brain atlas illustration (right) and Nissl staining (left) indicating PrL punch location. (B) The expression of Cnr1 (left) was unaffected by drug treatment. Cnr2 (right) expression was increased in the MK+Veh group compared to all other groups. (C) Rat brain atlas illustration (right) and Nissl staining (left) indicating BLA punch location. (D)Cnr1 (left) expression was increased in the MK+Veh group compared to all other groups; Cnr2 expression (right) was unaffected by drug treatment. Data represent fold change ± SEM. Numbers in bars represent n/group. *P < .05, relative to the Sal+Veh group.

We examined mRNA gene expression levels of glutamate and GABA markers in PrL and IL. Glutamate markers included the vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (Vglut1),28 and the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5). GABA markers included the presynaptic vesicular GABA transporter (Vgat)29 and parvalbumin (Pvalb).30 In PrL and BLA we examined the ECB markers cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (Cnr1 and Cnr2, respectively), and fatty acid amide hydrolase (Faah). In PrL, we also assessed dopamine receptors 1 and 2 (Drd1 and Drd2, respectively).

Statistical analyses were performed on ΔCt values normalized to the reference gene hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase (Hprt). Fold change values were calculated as 2−ΔΔCt relative to the Sal+Veh group and used in graph presentations.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 25 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois). Normality assumption was examined by Shapiro–Wilk test for all dependent variables. Normally-distributed data (Shapiro–Wilk P > .05) were analyzed with ANOVA. When ANOVA revealed significant differences, Games-Howell post-hoc tests were conducted with bootstrapping (BCa 95% confidence interval (CI), 5000 samples) to account for potential violations of the homoscedasticity assumption.31 When data did not distribute normally (Shapiro–Wilk P < .05), the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Mann–Whitney post-hocs, were used. Outliers were defined by 2 standard deviations from the group mean and removed from the analysis.

Results

URB597-Induced Reversal of MK-801 Effects on Social and Cognitive Behavior Is Differentially Mediated by CB1 and CB2 Receptors

We assessed whether early-adolescence MK-801 administration induces behavioral deficits in adulthood, whether late-adolescence URB597 can preempt these deficits, and whether the reversal of MK-induced deficits by URB597 treatment is mediated by CB1r and/or CB2r.

Open Field.

Repeated-measures ANOVA on distance travelled during 6 5 min bins [time × group (6 × 6)] revealed an effect of time [figure 2A, left; F(2.9,240) = 400.491, P < .0001], pointing to decreased activity across groups over time, but no effect of group [F(5,83) = 1.44, P > .1], or a time × group interaction [F(14.5,240) = .57, P>.1]. One-way ANOVA on time in center during the first 5 min bin revealed no group differences [figure 2A, right; F(5,87) = .77, P > .1]. Hence, drug treatment did not affect locomotor activity or anxiety-like behavior in adulthood.

Fig. 2.

MK-801-induced behavioral effects and their CB1/2r-mediated reversal by URB597. (A) In the OF, no group differences were observed in total distance travelled during 6 5 min bins (left), or in the time spent in the center during the first 5 min (right). (B) In the NOR test phase, no differences were observed in total exploration time (left), but a lower DI was observed in the MK+Veh group compared to Sal+Veh, and in the MK+URB+AM630 group compared to MK+URB (right). (C) In the SIT, MK+Veh rats demonstrated a lower sociability index (left), as well as increased non-social behavior (right) compared to Sal+Veh; the MK+URB+AM251 group had lower sociability index (left) and higher non-social behavior (right) compared to MK+URB. (D) In the Water T-maze, no group effects were found in the number of trials to criterion in the acq (left) or rev (right) phases. Bars represent group means and SEM. *CI P < .05, compared to the Sal+Veh or MK+URB groups, as described.

Novel Object Recognition.

One-way ANOVA showed that while the total exploration time in the test phase did not differ between groups [figure 2B, left; F(5,84) = 1.09, P > .1], there was an effect of group on DI [figure 2B, right; F(5,87) = 6.34, P < .0001]. Post-hoc comparisons point to lower DI in the MK+Veh group compared to the Sal+Veh (CI: −.21, −.02), Sal+URB (CI: −.37, −.09), and MK+URB (CI: −.2, −.03) groups; no differences were found between the Sal+Veh and MK+URB group (CI: −.07, .06), or the Sal+Veh and Sal+URB (CI: −.24, .006) groups. The DI of the MK+URB+AM630 (CI: .066, .22) but not the MK+URB+AM251 group (CI: −.05, .09) was significantly lower than the DI of the MK+URB group. These findings indicate that (1) MK-801 led to long-term impairments in novelty recognition, reversed by URB597; and (2) the effect of URB597 was mediated by CB2r.

Social Interaction Test.

One-way ANOVA revealed group effects on the sociability index [figure 2C, left; F(5,87) = 12.81, P < .0001] and nonsocial behaviors [figure 2C, right; F(5,87) = 12.81, P < .0001]. Post-hoc tests showed that the MK+Veh group had a lower sociability index and spent more time in nonsocial behaviors than the Sal+Veh (social, CI: −.23, −.12; nonsocial, CI: 28.59, 77.18), Sal+URB (social, CI: −.15, −.05; nonsocial, CI: 14.9, 45.75), and the MK+URB groups (social, CI: −.17, −.08; nonsocial, CI: 18.41, 61.25). The Sal+URB group exhibited a lower sociability index and more nonsocial behavior than the Sal+Veh group (social, CI: .01, .13; nonsocial, CI: −38.9, −5.2). No differences were found between the Sal+Veh and the MK+URB groups in the sociability index (CI: −.09, .005) or nonsocial behaviors (CI: −2.41, 28.44). The MK+URB+AM251 group exhibited a lower sociability index (CI:.05, .17) and more nonsocial behaviors (CI: −52.75, −18.35) compared to the MK+URB group. No differences were seen between the MK+URB+AM630 and the MK+URB groups in sociability index (CI: −.01, .09) or nonsocial behaviors (CI: −27.82, 3.87). This indicates that (1) MK-801 led to long-term impairments in social behavior, reversed by URB597; and (2) the effect of URB597 was mediated by CB1r.

Water T-maze.

A repeated-measures ANOVA [phase × group (2 × 6)] on the number of trials to reach criterion in acquisition and reversal revealed an effect of phase [F(1,77) = 5.99, P < .05], suggesting that the latency to reach criterion was longer in reversal than in acquisition for all groups. We found no effects of group [F(5,77) = 1.6, P > .1], or a phase × group interaction [F(5,77) = 1.2, P > .1; figure 2D].

An additional experiment was performed to examine the effects of late-adolescence AM251 and AM630 administration on behavior in early-adolescence saline- or MK-801-treated rats. As shown in supplementary figure S2, this experiment replicated the effects of early-adolescence MK-801 on adult behavior in the NOR and SIT. However, neither antagonist had an effect on behavior in the OF, NOR, SIT, or water T-maze tasks in saline- or MK-801-treated rats (see detailed results in supplementary information).

URB597 Reverses the Long-Term Effects of MK-801 on Gene Expression of Glutamate and GABA Markers in the PrL

To determine whether early-adolescence MK-801 leads to abnormal mPFC expression of glutamate and GABA markers, and whether these abnormalities are reversed by late-adolescence URB597 treatment, we examined mRNA levels of Vglut1, mGluR5, Vgat, and Pvalb in the PrL (figure 3A–C) and IL (figure 3D–F) of Sal+Veh, MK+Veh, Sal+URB, and MK+URB rats. In PrL, mRNA expression of presynaptic glutamate and GABA markers Vglut1 and Vgat, respectively, was upregulated in the MK+Veh group and this effect was reversed by subsequent URB597 treatment (Vglut1: H(3,33) = 5.48, P < .05; MK+Veh > Sal+Veh, Z = −2.5, P < .05; MK+Veh > MK+URB, Z = −2.21, P < .05. Vgat: H(3,31) = 17.85, P < .05; MK+Veh > Sal+Veh, Z = −2.4, P < .05; MK+Veh > MK+URB, Z = −2.25, P < .05). No differences were observed in Vglut1 expression between the Sal+URB and Sal+Veh groups (Z = −.053, P > 1), but Vgat was upregulated by approximately 5-fold in the Sal+URB group compared to Sal+Veh (Z = −2.92, P < .01) and MK+URB (Z = −3, P < .01). mGluR5 and the GABA marker Pvalb were downregulated in the MK+Veh group, and this effect was reversed by subsequent URB597 treatment (mGluR5: F(2,33) = 4.01, P < .05; MK+Veh < Sal+Veh, CI: .3, .86; MK+Veh < MK+URB, CI: .23, .82. Pvalb: F(3,32) = 7.94, P < .0001; MK+Veh < Sal+Veh, CI: .24, 1.05; MK+Veh < MK+URB CI: .29, 1.15). In the Sal+URB group, mGluR5 expression did not differ from Sal+Veh (CI: −.1, 1.09), MK+Veh (CI: −.7, .53), or MK+URB (CI: −.16, 1.06). Pvalb was downregulated in the Sal+URB group compared to Sal+Veh (CI: .39, 1.31) and MK+URB (CI: .44, 1.39).

In the IL, MK-801 treatment alone had no effect on gene expression. Vglut1 mRNA expression was downregulated in the MK+URB group compared to all other groups (F(3,29) = 4.88, P < .01, MK+URB < Sal+Veh, CI: .17, .78; MK+URB < MK+Veh CI: .12, .62; MK+URB < Sal+URB, CI: .13, .67). mGluR5 and Vgat were upregulated in the Sal+URB group compared to all other groups (mGluR: F(3,34) = 19.21, P < .0001; Sal+URB > Sal+Veh, CI: −1.39, −.9; Sal+URB > MK+Veh, CI: −1.37, −.97; Sal+URB > MK+URB, CI: −1.79, −.97. Vgat: H(3,38) = 17.72, P < .0001; Sal+URB > Sal+Veh, Z = −3.48, P < .0001; Sal+URB > MK+Veh, Z = −.41, P < .0001; Sal+URB > MK+URB, Z = −3.41, P < .0001). No group effects were found in the expression of Pvalb [H(3,34) = 1.17, P > .1].

URB597 Reverses the Long-Term Effects of MK-801 on Gene Expression of Cnr1 and Cnr2 in PrL and BLA

Since URB597 reversed the MK-801-induced NOR deficits via its effects on CB2r (figure 2B) and social interaction deficits via its effects on CB1r (figure 2C), we examined the expression of Cnr1 and Cnr2 in the PrL (figure 4A and B), associated with novelty recognition32 and the BLA (figure 4C and D), involved in social interaction and social reward processing.33

In PrL, MK-801 or URB597 had no effect on Cnr1 expression [figure 4B, left; H(3,37) = 1.09, P > .1]. Cnr2 expression was upregulated in the MK+Veh group, and this effect was reversed by URB597 treatment (figure 4B, right, F(3,25) = 4.08, P < .05; MK+Veh > Sal+Veh, CI: −1.09, −.19; MK+Veh > Sal+URB, CI: −1.21, −.19; MK+Veh > MK+URB, CI: −.89, −.13).

In the BLA, Cnr1 expression was upregulated in the MK+Veh group and this effect was reversed by URB597 treatment (figure 4D, left; F(3,21) = 3.56, P < .05; MK+Veh > Sal+Veh, CI: −1.28, −.32; MK+Veh > Sal+URB, CI: −1.49, −.32; MK+Veh > MK+URB, CI: −1.43, −.15). MK-801 or URB597 had no effect on Cnr2 [figure 4D, right; F(3,24) = .69, P > .1].

mRNA expression of Faah was decreased by URB in PrL (F(3,30) = 3.62, P < .05; Sal+URB < Sal+Veh, CI: .08, .98; Sal+URB < MK+URB, CI: .03, .87). No group effects on Faah expression were observed in BLA [F(3,23) = .76, P > .1; supplementary figure S1].

The mRNA expression levels of Drd1 and Drd2 in PrL did not differ between groups [Drd1: F(2,31) = 1.07, P > .1. Drd2: F(3,31) = 2.58, P > .05; supplementary figure S3].

Discussion

Early-adolescence chronic NMDAr hypofunction induces SZ-like deficits in novelty recognition and social behavior in adult male rats, and alters the mRNA expression of glutamate and GABA markers in the PrL subregion of the mPFC. URB597 rescues behavioral and gene expression deficits. Our pharmacological studies show that the effects of URB597 on NOR are mediated by CB2r, whereas its reversal of MK-801-induced deficits in social behavior are exerted via CB1r. In line with these behavioral findings, URB597 reverses MK-801-induced abnormalities in mRNA expression of Cnr1 and Cnr2 in the BLA and PrL, implicated in social reward and cognitive behavior, respectively.

Early-adolescence MK-801 impairs object recognition memory and social behavior in adult rats, corroborating previous studies with NMDAr antagonists administered in adolescence15,34 and adulthood.35,36 These findings support the validity of NMDAr blockade in rodents as a model for the negative and cognitive symptoms of SZ, and show that cognitive and social deficits are present long after NMDAr dysfunction was induced.

The absence of locomotor activity or spatial acquisition deficits indicates that early-adolescence MK-801 administration does not lead to general motor or learning impairment in adulthood. MK-801 also leaves reversal learning intact, contrary to previous studies with NMDAr blockers.37,38 This may signify that NMDAr blockade has immediate, rather than long-term effects on reversal learning, or that deficits may be task-dependent.

Our molecular findings point to long-term effects of NMDAr blockade on glutamate and GABA transmission. Consistent with previous observations of excess glutamate release in the PFC following NMDAr blockade,39 we find that early-adolescence MK-801 upregulates the expression of Vglut1 in the adult PrL. We also find downregulation of Pvalb mRNA levels in the PrL, but not IL, of MK-801-treated rats. This is consistent with findings of PCP-induced reductions in parvalbumin immunoreactivity in PrL but not IL,40 and with parvalbumin deficits consistently demonstrated in the DLPFC of SZ patients.41 Possibly, NMDAr hypofunction during a critical period of brain development weakens interneurons' ability to regulate pyramidal cell activity, leading to enhanced glutamate release in adult animals.

Our finding of increased Vgat expression indicates that GABAergic dynamics are affected by NMDAr blockade in a cell type-specific manner, and that compensatory mechanisms may be at play. MK-801-induced downregulation of mGluR5 expression points to a disrupted balance between glutamate and GABA transmission, as mGluR5s modulate the expression of glutamate transporters42 and were found to be critical for maintaining PFC GABAergic activity.43

URB597 normalized MK-801-induced impairments in Vglut1, Vgat, mGluR5, and Pvalb in PrL, suggesting that ECB potentiation can repair glutamate and GABA abnormalities induced by earlier NMDAr blockade. URB597 may act directly to inhibit glutamate and/or GABA release, or indirectly by affecting other components of the glutamate-GABA synapse. For example, URB597's normalizing effect on mGluR5 expression may lead to increased AEA synthesis, resulting in increased CB1r-dependent inhibition of glutamate spillover.44 Alternatively, URB597 may restore disrupted parvalbumin interneuron activity, ultimately mitigating pyramidal cell firing.45 Taken together, our molecular findings suggest that URB597 protects against excess glutamate activity. Notably, URB597 alone induced changes in the expression of GABA markers in the PrL, and in glutamate and GABA markers in the IL, suggesting that increased ECB signaling may be beneficial in cases where glutamate and/or GABA homeostasis is disrupted but have different influences in the undisrupted brain.

URB597 reversed the effects of MK-801 on behavior, consistent with previous experiments showing the beneficial effects of enhanced ECB signaling on social and cognitive dysfunction.16,17 Reversal of social deficits was mediated by CB1r activation, in line with a previous study on URB597's effects on PCP-induced social withdrawal.17 The reversal of NOR deficits in our study was mediated by CB2r activation. This study adds to current literature by showing the long-term effects of MK-801 and URB597, and by demonstrating a dissociation between CB1r and CB2r in mediating social and cognitive capacities. Notably, apart from a slight increase in non-social behavior, long-term treatment with URB597 alone in late adolescence had no impact on adult behavior. Moreover, late-adolescence AM251 and AM630 had no behavioral impact on saline- or MK-801 treated rats.

MK-801-induced behavioral deficits and their reversal by URB597 are mirrored by molecular findings of Cnr1 and Cnr2 expression in BLA and PrL. In the PrL, which plays a role in novelty recognition,32 we found that URB597 reverses the MK-801-induced upregulation in Cnr2 with no effect on Cnr1. In the BLA, which is implicated in motivated social behavior,33 URB597 reversed the MK-801-induced upregulation in Cnr1, but had no effect on Cnr2. Previous findings from our lab similarly showed that URB597 normalizes increased protein expression of CB1r in the BLA.23

The limitations of the current study are that (1) Experiments were performed in male rats only. The ECB system interacts substantially with feminine sex hormones,46 possibly accounting for previously-observed sex differences in the response to ECB-based pharmacological interventions.23 The investigation of URB597 effects in females is critical, and requires a separate study. (2) Gene expression changes were assessed on the mRNA level, which do not necessarily correlate with changes in protein expression due to regulatory expression control at different levels.47 Therefore, mRNA changes in the present study should be regarded as markers of change in relevant neurotransmitter systems, rather than indicators of translational alterations. Despite these limitations, the ability of URB597 to reverse the MK-801-induced behavioral deficits points to a therapeutic capacity of ECB stimulation in treating chronic aspects of SZ. The differential reversal of URB597's behavioral effects by CB1r or CB2r antagonism suggests that discrete molecular pathways are involved in different aspects of SZ symptoms. In conclusion, by showing that increased ECB signaling is able to reverse SZ-like behavioral dysfunctions and molecular abnormalities, our findings can contribute to future development of novel ECB-based treatment venues for the treatment resistant symptoms of SZ.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tomer Mizrachi Zer-Aviv for assistance in behavioral procedures and Nissl staining guidance.

Contributor Information

Hagar Bauminger, Department of Psychology, School of Psychological Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838, Israel; The Integrated Brain and Behavior Research Center (IBBRC), University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838, Israel.

Hiba Zaidan, Department of Psychology, School of Psychological Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838, Israel; The Integrated Brain and Behavior Research Center (IBBRC), University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838, Israel.

Irit Akirav, Department of Psychology, School of Psychological Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838, Israel; The Integrated Brain and Behavior Research Center (IBBRC), University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838, Israel.

Inna Gaisler-Salomon, Department of Psychology, School of Psychological Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838, Israel; The Integrated Brain and Behavior Research Center (IBBRC), University of Haifa, Haifa 3498838, Israel.

Funding

This work was made possible by grant support from the Israel Ministry of Health (I.G.S. and I.A., 3-15065), from the National Institute for Psychobiology in Israel (I.G.S. and I.A., 236-17-18), and from the Israel Science Foundation-National Natural Science Foundation of China (I.G.S., 2401/18).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. Karam CS, Ballon JS, Bivens NM, et al. Signaling pathways in schizophrenia: emerging targets and therapeutic strategies. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neill JC, Barnes S, Cook S, et al. Animal models of cognitive dysfunction and negative symptoms of schizophrenia: focus on NMDA receptor antagonism. Pharmacol Ther. 2010;128:419–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marder SR, Galderisi S. The current conceptualization of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:14–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sheffield JM, Karcher NR, Barch DM. Cognitive deficits in psychotic disorders: a lifespan perspective. Neuropsychol Rev. 2018;28:509–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsai G, Coyle JT. Glutamatergic mechanisms in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:165–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Insel TR. Rethinking schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hu HY, Kruijssen DLH, Frias CP, Rózsa B, Hoogenraad CC, Wierenga CJ. Endocannabinoid signaling mediates local dendritic coordination between excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Cell Rep. 2019;27:666–675.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, et al. Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene: longitudinal evidence of a gene X environment interaction. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1117–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernandez-Espejo E, Viveros MP, Núñez L, Ellenbroek BA, Rodriguez de Fonseca F. Role of cannabis and endocannabinoids in the genesis of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;206:531–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iseger TA, Bossong MG. A systematic review of the antipsychotic properties of cannabidiol in humans. Schizophr Res. 2015;162:153–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haller J, Szirmai M, Varga B, Ledent C, Freund TF. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor dependent effects of the NMDA antagonist phencyclidine in the social withdrawal model of schizophrenia. Behav Pharmacol. 2005;16:415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zimmermann T, Bartsch JC, Beer A, et al. Impaired anandamide/palmitoylethanolamide signaling in hippocampal glutamatergic neurons alters synaptic plasticity, learning, and emotional responses. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1377–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, et al. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bubeníková-Valesová V, Horácek J, Vrajová M, Höschl C. Models of schizophrenia in humans and animals based on inhibition of NMDA receptors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32:1014–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li JT, Su YA, Guo CM, et al. Persisting cognitive deficits induced by low-dose, subchronic treatment with MK-801 in adolescent rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;652:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kruk-Slomka M, Banaszkiewicz I, Slomka T, Biala G. Effects of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitors acute administration on the positive and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia in mice. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56:7251–7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seillier A, Martinez AA, Giuffrida A. Phencyclidine-induced social withdrawal results from deficient stimulation of cannabinoid CB1 receptors: implications for schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1816–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Craft RM, Marusich JA, Wiley JL. Sex differences in cannabinoid pharmacology: a reflection of differences in the endocannabinoid system? Life Sci. 2013;92:476–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. García-Gutiérrez MS, Pérez-Ortiz JM, Gutiérrez-Adán A, Manzanares J. Depression-resistant endophenotype in mice overexpressing cannabinoid CB(2) receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1773–1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fidelman S, Mizrachi Zer-Aviv T, Lange R, Hillard CJ, Akirav I. Chronic treatment with URB597 ameliorates post-stress symptoms in a rat model of PTSD. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28:630–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alteba S, Mizrachi Zer-Aviv T, Tenenhaus A, et al. Antidepressant-like effects of URB597 and JZL184 in male and female rats exposed to early life stress. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;39:70–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Piomelli D, Tarzia G, Duranti A, et al. Pharmacological profile of the selective FAAH inhibitor KDS-4103 (URB597). CNS Drug Rev. 2006;12:21–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zer-Aviv TM, Akirav I. Sex differences in hippocampal response to endocannabinoids after exposure to severe stress. Hippocampus. 2016;26:947–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zaidan H, Leshem M, Gaisler-Salomon I. Prereproductive stress to female rats alters corticotropin releasing factor type 1 expression in ova and behavior and brain corticotropin releasing factor type 1 expression in offspring. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:680–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lander SS, Linder-Shacham D, Gaisler-Salomon I. Differential effects of social isolation in adolescent and adult mice on behavior and cortical gene expression. Behav Brain Res. 2017;316:245–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alteba S, Korem N, Akirav I. Cannabinoids reverse the effects of early stress on neurocognitive performance in adulthood. Learn Mem. 2016;23:349–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Paxinos G, Watson C.. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 6th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fremeau RT Jr, Voglmaier S, Seal RP, Edwards RH. VGLUTs define subsets of excitatory neurons and suggest novel roles for glutamate. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McIntire SL, Reimer RJ, Schuske K, Edwards RH, Jorgensen EM. Identification and characterization of the vesicular GABA transporter. Nature. 1997;389:870–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Markram H, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Wang Y, Gupta A, Silberberg G, Wu C. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:793–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee S, Lee DK. What is the proper way to apply the multiple comparison test? Korean J Anesthesiol. 2018;71:353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Farahbakhsh ZZ, Siciliano CA. Neurobiology of novelty seeking. Science. 2021;372:684–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Trezza V, Damsteegt R, Manduca A, et al. Endocannabinoids in amygdala and nucleus accumbens mediate social play reward in adolescent rats. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14899–14908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. White IM, Minamoto T, Odell JR, Mayhorn J, White W. Brief exposure to methamphetamine (METH) and phencyclidine (PCP) during late development leads to long-term learning deficits in rats. Brain Res. 2009;1266:72–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rung JP, Carlsson A, Rydén Markinhuhta K, Carlsson ML. (+)-MK-801 induced social withdrawal in rats; a model for negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29:827–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rajagopal L, Massey BW, Huang M, Oyamada Y, Meltzer HY. The novel object recognition test in rodents in relation to cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:5104–5114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chadman KK, Watson DJ, Stanton ME. NMDA receptor antagonism impairs reversal learning in developing rats. Behav Neurosci. 2006;120:1071–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nikiforuk A, Gołembiowska K, Popik P. Mazindol attenuates ketamine-induced cognitive deficit in the attentional set shifting task in rats. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;20:37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roenker NL, Gudelsky GA, Ahlbrand R, Horn PS, Richtand NM. Evidence for involvement of nitric oxide and GABA(B) receptors in MK-801- stimulated release of glutamate in rat prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:575–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McKibben CE, Jenkins TA, Adams HN, Harte MK, Reynolds GP. Effect of pretreatment with risperidone on phencyclidine-induced disruptions in object recognition memory and prefrontal cortex parvalbumin immunoreactivity in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2010;208:132–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lewis DA, Curley AA, Glausier JR, Volk DW. Cortical parvalbumin interneurons and cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:57–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aronica E, Gorter JA, Ijlst-Keizers H, et al. Expression and functional role of mGluR3 and mGluR5 in human astrocytes and glioma cells: opposite regulation of glutamate transporter proteins. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2106–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Barnes SA, Pinto-Duarte A, Kappe A, et al. Disruption of mGluR5 in parvalbumin-positive interneurons induces core features of neurodevelopmental disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:1161–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Batista EM, Doria JG, Ferreira-Vieira TH, et al. Orchestrated activation of mGluR5 and CB1 promotes neuroprotection. Mol Brain. 2016;9:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gonzalez-Burgos G, Lewis DA. GABA neurons and the mechanisms of network oscillations: implications for understanding cortical dysfunction in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:944–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tabatadze N, Huang G, May RM, Jain A, Woolley CS. Sex differences in molecular signaling at inhibitory synapses in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2015;35:11252–11265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vogel C, Marcotte EM. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.