Abstract

Social mixing contributes to the transmission of SARS-CoV-2. We developed a composite measure for risky social mixing, investigating changes during the pandemic and factors associated with risky mixing. Forty-five waves of online cross-sectional surveys were used (n = 78,917 responses; 14 September 2020 to 13 April 2022). We investigated socio-demographic, contextual and psychological factors associated with engaging in highest risk social mixing in England at seven timepoints. Patterns of social mixing varied over time, broadly in line with changes in restrictions. Engaging in highest risk social mixing was associated with being younger, less worried about COVID-19, perceiving a lower risk of COVID-19, perceiving COVID-19 to be a less severe illness, thinking the risks of COVID-19 were being exaggerated, not agreeing that one’s personal behaviour had an impact on how COVID-19 spreads, and not agreeing that information from the UK Government about COVID-19 can be trusted. Our composite measure for risky social mixing varied in line with restrictions in place at the time of data collection, providing some validation of the measure. While messages targeting psychological factors may reduce higher risk social mixing, achieving a large change in risky social mixing in a short space of time may necessitate a reimposition of restrictions.

Subject terms: Human behaviour, Viral infection

Introduction

Behavioural strategies to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2 have focused on reducing the number of contacts made in everyday life through policies requiring people to work from home where possible, avoid hospitality and leisure venues, and remain physically distant from each other. This is an effective way of decreasing transmission1. In England, there have been a series of national restrictions limiting social contact (Table 1). In some cases, social mixing was only allowed in outdoor spaces, due to evidence suggesting that transmission is lower in more ventilated areas (see Supplementary Materials 1 for a more detailed description of restrictions)2,3. Compared to before the pandemic, people’s contacts were reduced between March 2020 and March 2021, with contact patterns changing in line with UK Government recommendations4. Previous studies have investigated people’s contact behaviour in a range of different settings (e.g. at home, work, on public transport, and while socialising). A previous paper from this series of surveys has explored factors associated with working outside of the home5. In this study, we focus solely on patterns of social mixing.

Table 1.

Restrictions on social mixing in England during the pandemic (March 2020–July 2021).

| Date | Restriction | Setting | Social contact allowed | Number of people from other households allowed | Distancing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 March 2020 | People asked to stay at home | All settings | Yes | Not specified | Not specified |

| 23 March 2020 | First national lockdown | All settings | No | None | N/A |

| 13 May 2020 | Step 1 of lockdown restrictions easing | Outdoor public spaces | Yes | One | 2 m+ |

| 1 June 2020 | Step 2 of lockdown restrictions easing | Outdoor public spaces | Yes | Five | 2 m+ |

| 4 July 2020 | Hospitality reopens | Outdoors | Yes | Five | 1 m+ |

| Indoors | Yes | Not specified, from one other household | 1 m+ | ||

| 14 September 2020 | Rule of six | Outdoors | Yes | Five | Not specified |

| Indoors | Yes | Five | Not specified | ||

| 14 October 2020 | Tiers (local COVID-19 alert level) | ||||

| 1 (medium) | Outdoors | Yes | Five | Not specified | |

| Indoors | Yes | Five | Not specified | ||

| 2 (high) | Outdoors | Yes | Five | Not specified | |

| Indoors | No | None | N/A | ||

| 3 (very high) | Outdoor public spaces | Yes | Five | Not specified | |

| Indoors | No | None | N/A | ||

| 5 November 2020 | Second national lockdown | All settings | No | None | N/A |

| 2 December 2020 | Tiers (local COVID-19 alert level) | ||||

| 1 (medium) | Outdoors | Yes | Five | Not specified | |

| Indoors | Yes | Five | Not specified | ||

| 2 (high) | Outdoors | Yes | Five | Not specified | |

| Indoors | No | None | N/A | ||

| 3 (very high) | Outdoor public spaces | Yes | Five | Not specified | |

| Indoors | No | None | N/A | ||

| 19 December 2020 | Tier 4 | Outdoor public spaces | Yes | One | 1 m+ |

| 5 January 2021 | Third national lockdown | All settings | No | None | N/A |

| 29 March 2021 | Step 1 of roadmap | Outdoor public spaces | Yes | Five, or one other household | 1 m+ |

| Indoors | No | None | N/A | ||

| 12 April 2021 | Step 2 of roadmap | Outdoors | Yes | Five, or one other household | 1 m+ |

| Indoors | No | None | N/A | ||

| 17 May 2021 | Step 3 of roadmap | Outdoors | Yes | Twenty-nine | 1 m+ |

| Indoors | Yes | Five, or one other household | None | ||

| 19 July 2021 | Step 4 of roadmap | All settings | Yes | No limit | None |

Protective behaviours are only effective at preventing transmission of infection if people adhere to them. One way of encouraging uptake is to legally enforce behaviours, and to limit people’s opportunity to socialise (e.g. by closing hospitality venues). In England, legal restrictions on social mixing were in place between 27 March 2020 and 19 July 20216,7. After this, emphasis was placed on individuals understanding and managing their own risk8. While new measures were introduced in response to the Omicron variant (November 2021 to January 2022), these did not include restrictions on social mixing, focusing instead on mandating face coverings and vaccine passports in certain indoor spaces, and working from home where possible9,10.

A range of factors—socio-demographic, contextual, and psychological—may affect whether people adopt protective behaviours. Research suggests that women, older people, those with chronic illnesses, people who perceived measures to be more effective, people who perceived COVID-19 to be a more severe illness, and those who thought that others were also adhering to measures were more likely to adopt physical distancing behaviours11–14. A study investigating close contacts during the pandemic found that people who reported more contacts were less likely to think that COVID-19 would be a serious illness for them, were more likely to agree that they were likely to catch COVID-19, and were more concerned that they might spread COVID-19 to others4. These studies investigated factors associated with individual dimensions of social mixing, for example the number of times people had met up with friends or family socially, whether they came into close contact with others, or self-reported adherence to Government guidelines. A detailed understanding of how patterns of social mixing changed under different restrictions over the course of the pandemic is missing. Furthermore, most studies investigated mixing at the start of the pandemic (May 2020), with one study analysing data collected up to December 202014, and another analysing data up to March 20214. At the time of writing, there were no available data investigating social mixing after the release of all legal restrictions in the UK on 19 July 2021.

Since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak, we have been working with the English Department of Health and Social Care to track behaviours that affect SARS-CoV-2 transmission using a series of online cross-sectional surveys. Reporting has so far focused on individual behaviours and associated factors. However, the surveys include questions asking for detailed information on participants’ latest instance of social mixing (including setting, whether they maintained distance from others, how many other households they mixed with, how many people from other households were present), all of which influence transmission risk. We used these data to:

develop a composite measure for risky social mixing based on most recent social mixing, taking into account setting, close contact, number of households, and number of people from other households;

describe change over time in the percentage of people engaging in risky social mixing;

identify who is most likely to engage in risky social mixing, and whether socio-demographic, psychological, and contextual factors are associated with risky social mixing.

Methods

Design

A series of cross-sectional surveys have been carried out by BMG Research and then Savanta (both Market Research Society Company Partners) since January 2020 on behalf of the English Department of Health and Social Care. We analysed these data as part of the COVID-19 Rapid Survey of Adherence to Interventions and Responses (CORSAIR) study15. For this study, we used data collected between 14 September 2020 and 13 April 2022 (waves 28 to 72). These are the waves in which all questions used to form our outcome measure were included in the survey; some had not been introduced before 14 September 2020 (wave 28).

Participants

Participants were recruited from two specialist research panel providers, Respondi (n = 50,000) and Savanta (n = 31,500) and were eligible for the study if they were aged 16 years or over and lived in the UK (n ≈ 2000 per wave). Members of online research panels have consented to being contacted to take part in online surveys. Following industry standards, informed consent was implied by participants’ completion of the survey. Quotas based on age and gender (combined) were applied to ensure the sample was broadly representative of the UK population. After having completed the survey, participants were unable to take part in the following three waves of data collection. Participants were reimbursed in points which could be redeemed in cash, gift vouchers or charitable donations (up to 70p per survey). For this study, only participants living in England were selected, as restrictions differed between the four nations of the UK (n ≈ 1700 per wave).

Study materials

Full survey questions are presented in Supplementary Materials 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Participants reported their age, gender, employment status, highest educational or professional qualification, ethnicity, relationship status, how many people lived in their household, their first language, whether there was a dependent child in the household, the highest earner in household worked in a manual occupation, and whether they or a household member had a chronic illness. Participants were also asked for their full postcode, from which geographical region and indices of multiple deprivation were determined16.

Participants were asked if they thought they had previously, or currently, had COVID-19. We recoded answers into a binary variable (“I’ve definitely had it, and had it confirmed by a test” and “I think I’ve probably had it”, vs “I don’t know whether I’ve had it or not”, “I think I’ve probably not had it”, and “I’ve definitely not had it”).

Financial hardship was measured by asking participants to what extent in the past seven days they had been struggling to make ends meet, skipping meals they would usually have, and were finding their current living situation difficult (Cronbach’s α = 0.81).

Risky social mixing

All participants were asked “the number of times [they had] been out of [their] home in the last seven days … to meet up with friends and/or family that [they didn’t] live with”. From 1 June 2021 (wave 51), the wording of this question was slightly changed, to ask participants “how many times [they had] done each of the following activities in the past seven days…met up with friends and/or family that [they didn’t] live with”.

Participants who indicated they had been out at least once were asked a series of follow-up questions about “the last occasion [they] met up with friends and/or family they [didn’t] live with”. Questions asked whether the last occasion participants met up with friends or family occurred indoors or outdoors (“setting”), whether they stayed at least 2 m apart (“close contact”), how many other households were present (“total number of households”), and the number of people from outside their household (“number of people from other households”). Full survey items used in our outcome measure are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Coding of variables to compute risky social mixing variable.

| Variable | Question text | Response options | Risk level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setting (indoors/outdoors) |

And still thinking about only the last occasion you met up with friends and/or family, were you indoors or outdoors? [People in wave 44 were asked a slightly different version of this question. Therefore, we have excluded them from analyses] |

Exclusively outdoors | Lowest (“exclusively outdoors”) |

| Mostly outdoors | Medium (“mostly outdoors”) | ||

| Equally split between indoors and outdoors | Highest (“indoors”) | ||

| Mostly indoors | Highest (“indoors”) | ||

| Exclusively indoors | Highest (“indoors”) | ||

| Close contact | Again, thinking about the last occasion you met with friends and/or family that you don’t live with, did people stay at least 2 m apart? | Yes, at all times | Lowest (“distanced”) |

| Yes, most of the time | Lowest (“distanced”) | ||

| Yes, some of the time | Highest (“not distanced”) | ||

| No—not at all | Highest (“not distanced”) | ||

| Total number of households | The last time you met with friends and/ or family that you don’t live with, how many households (not people) did those people come from? Don’t include your own household in this number | Scale | Question + 1 (to include own household) |

| Lowest (“2”) | |||

| Highest (“3+”) | |||

| Number of people from other households | And still thinking about the last time you met friends and/or family that you don’t live with, how many people from outside your household were there? | Scale | Lowest (“ ≤ 2”) |

| Highest (“ ≥ 3”) |

Contextual and psychological factors

Participants were asked “the number of times [they had] been out of [their] home in the last seven days … to go out to work”. On 1 June 2021 (wave 51), the wording of this question was slightly changed, to ask participants “how many times [they had] done each of the following activities in the past seven days … left the house to go out to work (number of days)”.

Worry about COVID-19 was measured by asking participants “overall, how worried [they were] about coronavirus” on a five-point scale from “extremely worried” to “not at all worried”. Perceived risk of COVID-19 was measured by asking participants “to what extent [they thought] coronavirus [posed] a risk to” people in the UK and themselves personally on a five-point scale from “major risk” to “no risk at all”.

Other psychological factors were measured using a series of five statements, each of which was measured on a five-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Statements asked participants to what extent they agreed that COVID-19 would be a serious illness for them, they would worry about what others would think of them if they tested positive for COVID-19, someone could spread COVID-19 to other people even if they did not have symptoms yet, their personal behaviour had an impact on how COVID-19 spread, and they thought the risks of COVID-19 were being exaggerated.

Participants also indicated the extent to which they thought information from the UK Government about COVID-19 (a) could be trusted, and (b) was biased or one-sided on a five-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.

Ethics

This work was conducted as a service evaluation of the Department of Health and Social Care’s public communications campaign and, following advice from King’s College London Research Ethics Committee, was exempt from requiring ethical approval. The study was otherwise carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Power

A sample size of 1700 allows a 95% confidence interval of about plus or minus 2% for the prevalence estimate for a survey item with a prevalence of 50%.

Analysis

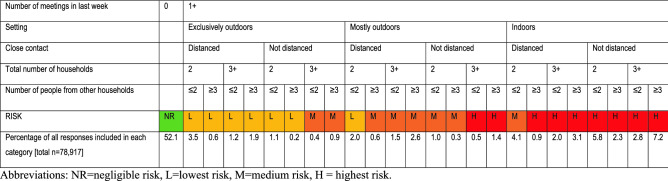

We used information about participants’ latest instance of social mixing to compute a measure of “risky social mixing”. Participants who reported that they had not been out to meet friends or family that they did not live with were assigned to the “negligible risk” category. For participants who reported having been out to meet friends or family from another household, we used information about setting (indoors/outdoors), whether they came into close contact with others, the total number of households, and how many people from other households were present to assign them a risk category. First, we created dichotomous or trichotomous variables denoting low or high risk (or low, medium, high risk where trichotomous) for each factor (Table 2). Second, participants were categorised according to risk ratings for individual factors (setting, close contact, total number of households present, number of people from other households). Third, risk ratings for individual variables were combined to give an overall risk rating, and participants’ latest instance of social mixing was categorised as “lowest risk”, “medium risk” or “highest risk” (Fig. 1). Risk ratings and their categorisations were developed using consensus agreement between the authors and the English Department of Health and Social Care and with advice from participants in COVID-19 working groups from public health agencies and experts in infectious disease transmission and modelling. People in wave 44 (data collected 22 to 23 February 2021) were asked a slightly different version of one of the questions used to create our composite measure. Therefore, we have excluded them from analyses. See Supplementary Materials 3 for responses to individual items.

Figure 1.

Categorisation of risk ratings.

To describe change in risky social mixing over time, we computed risky social mixing for each survey wave, presenting results graphically. Rates of risky social mixing between 1 November and 16 December 2021 (5 waves, wave 61 to 64) have been reported elsewhere17.

We investigated associations with highest risk social mixing at different time points within the pandemic. We selected slices of data (two or three survey waves) that were collected at seven different time points in the pandemic, choosing times when different restrictions were in place. Time points were: (1) rule of six indoors and outdoors (data collected 14 to 30 September 2020), (2) second national lockdown (data collected 9 to 25 November 2020), (3) third national lockdown (data collected 11 January to 9 February 2021), (4) rule of six outdoors, no indoor mixing (data collected 19 April to 5 May 2021), (5) rule of six indoors, up to 30 people outdoors (data collected 1 to 15 June 2021), (6) straight after the legal restrictions on social mixing were lifted (data collected 26 July to 10 August 2021), and (7) after the legal restriction to self-isolate if symptomatic had been lifted (proxy for return to most “normal” context in UK since the start of the pandemic; data collected 14 March to 13 April 2022).

We investigated associations between highest risk social mixing and:

socio-demographic characteristics (survey wave, region, gender, age [raw and quadratic], presence of a dependent child in the household, having a chronic illness oneself, having a household member who has chronic illness, employment status, highest earner in household works in a manual occupation, index of multiple deprivation, highest educational or professional qualification, ethnicity, first language, living alone, relationship status, having had COVID-19 before, and financial hardship) and,

contextual and psychological characteristics (having been out to work in the last week, worry about COVID-19, perceived risk of COVID-19 [to self and people in the UK], perceived severity of COVID-19, worry about what others would think if you tested positive for COVID-19, agreeing that someone can spread COVID-19 even if asymptomatic, thinking that your personal behaviour as an impact on the spread of COVID-19, thinking that the risks of COVID-19 are exaggerated, agreeing that information from the UK Government about COVID-19 can be trusted, and is biased or one-sided).

We used multivariable logistic regressions adjusting for all socio-demographic characteristics.

Multiple analyses were run on individual outcomes (n = 12), therefore we applied a Bonferroni correction (p ≤ 0.004).

Results

Participants

Descriptions of risky social mixing are based on 78,917 responses. 53.1% of respondents were women (n = 41,923; men 46.5%, n = 36,728; prefer to self-describe 0.2%, n = 196; prefer not to say 0.1%, n = 70). Respondents’ mean age was 48.4 years (SD = 17.7, range 16 to over 100 years). Respondents were slightly more likely to be white than the general population (82.5% white British, n = 65,122; 5.9% white other, n = 4638; 2.6% mixed, n = 2021; 5.3% Asian/Asian British, n = 4210; 2.6% Black/Black British, n = 2018; 0.5% Arab/other, n = 432; 0.6% prefer not to say, n = 476 [compared to 86.0% white in the 2011 census of England and Wales18]). Responses within each of our time slices are from separate individuals. However, respondents may appear in more than one time slice (n = 19,201 participants appear in one time point, 65.5% of responses; n = 4186 participants appear in more than one time point, 34.5% of responses).

Participants in different time slices did not vary significantly by key socio-demographic characteristics (Table 3). Where differences were statistically significant, values only differed minimally (by 4.1% or less). An exception was the increasing percentage of people who reported that they thought they had had COVID-19 in later time slices. This is congruent with the second wave of infections over winter 2020/2021. The other exception was for workplace attendance, which was markedly lower in the third national lockdown and higher after the legal obligation to self-isolate had been removed.

Table 3.

Respondent socio-demographic characteristics and workplace attendance for the full study sample, and within each time slice.

| Full study sample (total n = 78,917), % (n) | Rule of six indoors and outdoors (total n = 3423), % (n) | Second national lockdown (total n = 5223), % (n) | Third national lockdown (total n = 5116), % (n) | Rule of six outdoors, no indoor mixing (total n = 3298), % (n) | Rule of six indoors, up to 30 people outdoors (total n = 3367), % (n) | No restrictions on social mixing (total n = 3438), % (n) | No legal obligation to self-isolate (total n = 5455), % (n) | p-value between time slices | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | East Midlands | 9.0 (7124) | 8.4 (289) | 9.4 (491) | 9.1 (468) | 9.3 (308) | 9.1 (307) | 8.8 (303) | 9.2 (504) | 0.90 |

| East of England | 11.4 (9011) | 10.5 (358) | 11.7 (610) | 12.0 (613) | 12.2 (403) | 11.4 (383) | 10.8 (372) | 11.2 (611) | ||

| London | 14.1 (11,116) | 14.6 (501) | 14.1 (736) | 14.0 (714) | 13.3 (440) | 14.2 (478) | 14.2 (489) | 14.0 (761) | ||

| North East | 5.2 (4068) | 5.1 (173) | 5.8 (302) | 5.2 (266) | 5.2 (172) | 5.3 (177) | 5.1 (175) | 5.3 (289) | ||

| North West | 13.3 (10,510) | 13.6 (466) | 13.1 (683) | 12.9 (658) | 13.2 (436) | 12.6 (425) | 14.2 (488) | 13.6 (742) | ||

| South East | 15.9 (12,512) | 15.1 (517) | 15.4 (802) | 16.0 (819) | 15.1 (497) | 15.9 (535) | 15.1 (518) | 15.7 (857) | ||

| South West | 10.2 (8081) | 10.2 (349) | 10.0 (522) | 10.4 (531) | 9.9 (328) | 10.4 (350) | 10.8 (371) | 9.8 (534) | ||

| West Midlands | 10.6 (8360) | 11.2 (382) | 10.3 (539) | 9.8 (499) | 10.8 (357) | 10.3 (348) | 10.5 (362) | 11.1 (603) | ||

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 10.3 (8135) | 11.3 (388) | 10.3 (538) | 10.7 (548) | 10.8 (357) | 10.8 (364) | 10.5 (360) | 10.2 (554) | ||

| Gender | Male | 46.7 (36,728) | 45.8 (1563) | 46.7 (2434) | 47.4 (2419) | 46.8 (1538) | 45.8 (1536) | 46.8 (1605) | 48.2 (2615) | 0.28 |

| Female | 53.3 (41,923) | 54.2 (1852) | 53.3 (2774) | 52.6 (2682) | 53.2 (1751) | 54.2 (1816) | 53.2 (1828) | 51.8 (2815) | ||

| Age | Mean, SD | M = 48.4, SD = 17.7 | M = 48.0, SD = 16.9 | M = 48.6, SD = 17.1 | M = 48.8, SD = 17.5 | M = 47.6, SD = 16.9 | M = 48.5, SD = 17.3 | M = 49.4, SD = 17.3 | M = 48.6, SD = 17.1 | < 0.001* |

| 16 to 24 years | 10.7 (8463) | 8.9 (306) | 9.5 (498) | 9.9 (505) | 8.9 (295) | 9.6 (324) | 9.2 (317) | 13.4 (731) | ||

| 25 to 34 years | 16.1 (12,686) | 17.0 (581) | 15.1 (788) | 15.5 (794) | 17.6 (579) | 15.9 (536) | 14.8 (509) | 17.8 (971) | ||

| 35 to 44 years | 16.3 (12,871) | 18.5 (633) | 17.7 (925) | 16.3 (836) | 18.3 (604) | 16.9 (570) | 16.4 (564) | 15.2 (829) | ||

| 45 to 54 years | 18.1 (14,281) | 19.3 (662) | 18.6 (971) | 18.7 (955) | 19.7 (651) | 18.1 (608) | 18.9 (651) | 16.9 (920) | ||

| 55 to 64 years | 16.4 (12,912) | 15.0 (514) | 17.3 (901) | 17.1 (876) | 16.6 (548) | 17.8 (598) | 17.6 (605) | 13.7 (745) | ||

| 65 to 74 years | 14.6 (11,498) | 14.8 (506) | 15.6 (815) | 15.0 (768) | 12.6 (414) | 15.4 (519) | 14.4 (494) | 12.9 (706) | ||

| 75+ years | 7.9 (6206) | 6.5 (221) | 6.2 (325) | 7.5 (382) | 6.3 (207) | 6.3 (212) | 8.7 (298) | 10.1 (553) | ||

| Dependent child in household | None | 67.5 (53,308) | 65.8 (2253) | 68.4 (3574) | 67.9 (3473) | 65.6 (2164) | 66.9 (2254) | 67.8 (2332) | 64.5 (3519) | < 0.001* |

| Child present | 32.5 (25,609) | 34.2 (1170) | 31.6 (1649) | 32.1 (1643) | 34.4 (1134) | 33.1 (1113) | 32.2 (1106) | 35.5 (1936) | ||

| Chronic illness (self) | No | 71.2 (53,738) | 70.1 (2356) | 71.1 (3628) | 72.3 (3626) | 72.1 (2310) | 71.6 (2359) | 70.7 (2369) | 70.5 (3769) | 0.22 |

| Yes | 28.8 (21,730) | 29.9 (1003) | 28.9 (1474) | 27.7 (1391) | 27.9 (892) | 28.4 (935) | 29.3 (984) | 29.5 (1579) | ||

| Household member has chronic illness | No | 84.6 (63,864) | 83.9 (2817) | 83.7 (4268) | 83.7 (4199) | 84.6 (2708) | 84.6 (2787) | 84.7 (2839) | 85.8 (4587) | 0.05 |

| Yes | 15.4 (11,604) | 16.1 (542) | 16.3 (834) | 16.3 (818) | 15.4 (494) | 15.4 (507) | 15.3 (514) | 14.2 (761) | ||

| Employment status | Not working | 44.8 (34,865) | 44.4 (1500) | 45.0 (2314) | 44.5 (2248) | 42.5 (1379) | 45.1 (1499) | 44.7 (1518) | 43.0 (2317) | 0.12 |

| Working | 55.2 (43,001) | 55.6 (1880) | 55.0 (2830) | 55.5 (2807) | 57.5 (1867) | 54.9 (1824) | 55.3 (1876) | 57.0 (3077) | ||

| Highest earner in household works in a manual occupation | No | 71.6 (55,239) | 71.3 (2386) | 70.7 (3618) | 71.9 (3599) | 70.6 (2279) | 72.3 (2383) | 70.8 (2377) | 73.1 (3906) | 0.06 |

| Yes | 28.4 (21,873) | 28.7 (960) | 29.3 (1497) | 28.1 (1408) | 29.4 (951) | 27.7 (912) | 29.2 (982) | 26.9 (1436) | ||

| Index of multiple deprivation | 1st (least) to 4th quartile (most deprived), mean, SD | M = 2.66, SD = 1.1 | M = 2.61, SD = 1.1 | M = 2.62, SD = 1.1 | M = 2.56, SD = 1.1 | M = 2.64, SD = 1.09 | M = 2.61, SD = 1.1 | M = 2.61, SD = 1.11 | M = 2.62, SD = 1.1 | < 0.001* |

| Highest educational or professional qualification | Less than degree | 67.0 (52,856) | 67.5 (2311) | 65.4 (3417) | 65.6 (3357) | 66.5 (2192) | 67.1 (2259) | 66.7 (2292) | 67.2 (3667) | 0.24 |

| Degree or higher | 33.0 (26,061) | 32.5 (1112) | 34.6 (1806) | 34.4 (1759) | 33.5 (1106) | 32.9 (1108) | 33.3 (1146) | 32.8 (1788) | ||

| Ethnicity | White British | 83.0 (65,122) | 84.7 (2883) | 83.5 (4330) | 84.1 (4284) | 81.2 (2658) | 81.8 (2742) | 84.6 (2890) | 81.1 (4397) | < 0.001* |

| White other | 5.9 (4638) | 6.5 (221) | 6.9 (360) | 6.7 (339) | 7.4 (242) | 6.0 (202) | 5.5 (189) | 5.1 (275) | ||

| Black and minority ethnicity | 11.1 (8681) | 8.8 (299) | 9.6 (498) | 9.2 (471) | 11.4 (374) | 12.1 (407) | 9.9 (337) | 13.8 (748) | ||

| First language | Not English | 8.5 (6713) | 8.0 (274) | 8.7 (457) | 8.5 (437) | 9.5 (314) | 8.8 (295) | 7.2 (248) | 9.1 (494) | 0.02 |

| English | 91.5 (72,204) | 92.0 (3149) | 91.3 (4766) | 91.5 (4679) | 90.5 (2984) | 91.2 (3072) | 92.8 (3190) | 90.9 (4961) | ||

| Living alone | Not living alone | 79.6 (62,808) | 81.1 (2775) | 80.2 (4190) | 80.4 (4113) | 80.3 (2648) | 79.4 (2672) | 77.0 (2647) | 79.3 (4328) | 0.001* |

| Living alone | 20.4 (16,109) | 18.9 (648) | 19.8 (1033) | 19.6 (1003) | 19.7 (650) | 20.6 (695) | 23.0 (791) | 20.7 (1127) | ||

| Relationship status | Not partnered | 40.4 (31,599) | 39.2 (1323) | 38.7 (1995) | 38.8 (1969) | 39.3 (1283) | 40.0 (1332) | 40.4 (1372) | 42.0 (2279) | 0.009 |

| Partnered | 59.6 (46,607) | 60.8 (2053) | 61.3 (3161) | 61.2 (3104) | 60.7 (1984) | 60.0 (1996) | 59.6 (2028) | 58.0 (3146) | ||

| Ever had COVID-19 | Think not | 78.2 (61,694) | 84.6 (2895) | 85.5 (4464) | 83.6 (4278) | 82.3 (2714) | 82.8 (2788) | 79.8 (2745) | 58.1 (3172) | < 0.001* |

| Think yes | 21.8 (17,223) | 15.4 (528) | 14.5 (759) | 16.4 (838) | 17.7 (584) | 17.2 (579) | 20.2 (693) | 41.9 (2283) | ||

| Financial hardship | Range 3 (least) to 15 (most), mean, SD | N = 76,811, M = 7.7, SD = 3.1 | N = 3312, M = 7.9, SD = 3.0 | N = 5009, M = 7.9, SD = 3.0 | N = 4898, M = 7.9, SD = 2.9 | N = 3239, M = 7.6, SD = 3.1 | N = 3311, M = 7.5, SD = 3.1 | N = 3376, M = 7.4, SD = 3.2 | N = 5009, M = 7.9, SD = 3.0 | < 0.001* |

| Been out to work in last week | No | 63.3 (49,940) | 64.9 (2221) | 68.5 (3576) | 73.7 (3772) | 62.6 (2065) | 61.4 (2066) | 60.4 (2077) | 54.5 (2975) | < 0.001* |

| Yes | 36.7 (28,987) | 35.1 (1202) | 31.5 (1647) | 26.3 (1344) | 37.4 (1233) | 38.6 (1301) | 39.6 (1361) | 45.5 (2480) |

*p ≤ 0.004.

Social mixing

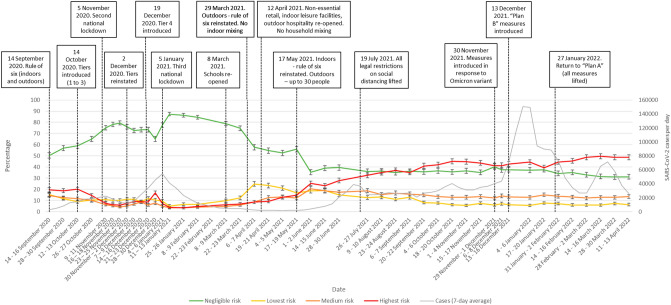

Patterns of risky social mixing changed over time, largely in line with restrictions on social mixing in place at the time of data collection (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Pattern of risky social mixing between September 2020 and April 2022. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. The grey line shows the number of new SARS-CoV-2 cases per day (7-day average) in England19. Case rates from April 2022 are an underestimate as only selected people were eligible for testing.

There was a large influence of time on engagement in highest risk social mixing (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of people engaging in risky social mixing at different time points in the pandemic.

| Rule of six indoors and outdoors (total n = 3423), % (n) | Second national lockdown (total n = 5223), % (n) | Third national lockdown (total n = 5116), % (n) | Rule of six outdoors, no indoor mixing (total n = 3298), % (n) | Rule of six indoors, up to 30 people outdoors (total n = 3367), % (n) | No restrictions on social mixing (total n = 3438), % (n) | No legal obligation to self-isolate (total n = 5455), % (n) | p-value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | % (95% CI) | n | ||

| Negligible risk | 53.6 (51.9 to 55.3) | 1835 | 77.6 (76.5 to 78.8) | 4055 | 86.1 (85.2 to 87.1) | 4407 | 53.6 (51.9 to 55.3) | 1769 | 37.2 (35.6 to 38.9) | 1254 | 36.2 (34.6 to 37.8) | 1244 | 31.3 (30.0 to 32.5) | 1706 | < 0.001 |

| Lowest risk | 13.6 (12.4 to 14.7) | 465 | 10.3 (9.5 to 11.1) | 538 | 6.2 (5.6 to 6.9) | 318 | 22.3 (20.9 to 23.8) | 737 | 18.8 (17.5 to 20.1) | 632 | 12.9 (11.8 to 14.0) | 443 | 6.6 (5.9 to 7.3) | 360 | < 0.001 |

| Medium risk | 13.6 (12.4 to 14.7) | 464 | 5.3 (4.7 to 6.0) | 279 | 3.6 (3.1 to 4.1) | 186 | 13.0 (11.8 to 14.1) | 428 | 19.6 (18.3 to 20.9) | 660 | 17.1 (15.8 to 18.3) | 587 | 13.1 (12.2 to 14.0) | 714 | < 0.001 |

| Highest risk | 19.3 (17.9 to 20.6) | 659 | 6.7 (6 to 7.4) | 351 | 4.0 (3.5 to 4.5) | 205 | 11.0 (10.0 to 12.1) | 364 | 24.4 (22.9 to 25.8) | 821 | 33.9 (32.3 to 35.4) | 1164 | 49.0 (47.7 to 50.4) | 2675 | < 0.001 |

At all timepoints, engaging in highest risk social mixing was associated with being less worried about COVID-19, perceiving a smaller risk of COVID-19 to oneself and people in the UK, lower perceived severity of COVID-19 to oneself, and thinking the risks of COVID-19 were being exaggerated (Tables 5, 6).

Table 5.

Socio-demographic characteristics associated with engaging in highest risk social mixing at different time points in the pandemic.

| Attribute | Level | Rule of six indoors and outdoors | Second national lockdown | Third national lockdown | Rule of six outdoors, no indoor mixing | Rule of six indoors, up to 30 people outdoors | No legal restrictions | No legal obligation to self-isolate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | ||

| Survey wave in timepoint | Wave 1 | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Wave 2 | 0.93 (0.77 to 1.11) | 0.40 | 0.85 (0.64 to 1.12) | 0.25 | 0.82 (0.55 to 1.21) | 0.32 | 1.57 (1.24 to 1.99) | < 0.001* | 0.87 (0.73 to 1.02) | 0.09 | 1.14 (0.98 to 1.32) | 0.09 | 0.96 (0.83 to 1.10) | 0.52 | |

| Wave 3 | – | – | 0.81 (0.61 to 1.08) | 0.16 | 1.25 (0.88 to 1.79) | 0.22 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.97 (0.85 to 1.12) | 0.71 | |

| Overall | – | – | χ2(2) = 2.3 | 0.32 | χ2(2) = 5.0 | 0.08 | – | – | – | – | – | – | χ2(2) = 0.4 | 0.81 | |

| Region | East Midlands | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| East of England | 0.93 (0.62 to 1.40) | 0.74 | 1.50 (0.91 to 2.47) | 0.11 | 0.98 (0.48 to 2.02) | 0.96 | 1.20 (0.71 to 2.02) | 0.50 | 1.09 (0.76 to 1.57) | 0.64 | 1.26 (0.90 to 1.77) | 0.17 | 1.13 (0.88 to 1.44) | 0.35 | |

| London | 0.90 (0.61 to 1.34) | 0.61 | 1.02 (0.62 to 1.70) | 0.93 | 1.07 (0.55 to 2.07) | 0.84 | 1.11 (0.66 to 1.85) | 0.70 | 0.99 (0.69 to 1.44) | 0.97 | 1.14 (0.82 to 1.58) | 0.44 | 1.07 (0.84 to 1.37) | 0.56 | |

| North East | 0.91 (0.55 to 1.49) | 0.70 | 0.79 (0.39 to 1.60) | 0.52 | 1.11 (0.47 to 2.63) | 0.81 | 1.28 (0.68 to 2.40) | 0.45 | 1.64 (1.07 to 2.52) | 0.02 | 1.14 (0.75 to 1.72) | 0.54 | 1.49 (1.09 to 2.02) | 0.01 | |

| North West | 0.59 (0.39 to 0.89) | 0.01 | 0.85 (0.49 to 1.45) | 0.54 | 1.34 (0.69 to 2.61) | 0.39 | 0.80 (0.47 to 1.38) | 0.43 | 0.89 (0.62 to 1.29) | 0.55 | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.30) | 0.72 | 1.17 (0.92 to 1.49) | 0.19 | |

| South East | 0.87 (0.60 to 1.28) | 0.49 | 1.14 (0.69 to 1.88) | 0.60 | 1.00 (0.51 to 1.97) | 1.00 | 1.62 (1.00 to 2.64) | 0.05 | 0.89 (0.63 to 1.26) | 0.51 | 1.13 (0.82 to 1.55) | 0.46 | 1.16 (0.92 to 1.46) | 0.22 | |

| South West | 1.22 (0.82 to 1.82) | 0.32 | 1.03 (0.59 to 1.79) | 0.92 | 0.65 (0.28 to 1.47) | 0.30 | 1.26 (0.74 to 2.16) | 0.40 | 1.06 (0.73 to 1.54) | 0.74 | 0.98 (0.70 to 1.38) | 0.92 | 1.02 (0.79 to 1.32) | 0.86 | |

| West Midlands | 0.89 (0.60 to 1.33) | 0.57 | 1.29 (0.77 to 2.16) | 0.33 | 1.38 (0.70 to 2.74) | 0.35 | 1.03 (0.60 to 1.77) | 0.91 | 1.22 (0.84 to 1.76) | 0.30 | 0.92 (0.66 to 1.30) | 0.65 | 1.18 (0.92 to 1.51) | 0.20 | |

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 0.94 (0.63 to 1.40) | 0.76 | 1.15 (0.68 to 1.95) | 0.60 | 1.43 (0.73 to 2.79) | 0.30 | 1.28 (0.76 to 2.17) | 0.36 | 1.18 (0.82 to 1.71) | 0.37 | 1.13 (0.80 to 1.59) | 0.49 | 1.17 (0.91 to 1.52) | 0.22 | |

| Overall | χ2(8) = 14.1 | 0.08 | χ2(8) = 8.6 | 0.38 | χ2(8) = 6.6 | 0.58 | χ2(8) = 10.8 | 0.21 | χ2(8) = 13.7 | 0.09 | χ2(8) = 6.9 | 0.54 | χ2(8) = 8.6 | 0.38 | |

| Gender | Male | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Female | 1.09 (0.90 to 1.31) | 0.38 | 0.80 (0.63 to 1.01) | 0.06 | 0.58 (0.42 to 0.79) | 0.001* | 0.85 (0.67 to 1.07) | 0.17 | 1.11 (0.93 to 1.31) | 0.24 | 1.17 (1.00 to 1.36) | 0.05 | 1.44 (1.29 to 1.61) | < 0.001* | |

| Age (per decade) | Raw age | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.95) | 0.001* | 0.88 (0.80 to 0.96) | 0.004* | 0.84 (0.75 to 0.94) | 0.003* | 0.86 (0.79 to 0.94) | 0.001* | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.98) | 0.01 | 0.93 (0.87 to 0.99) | 0.01 | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.96) | < 0.001* |

| Age: quadratic (age–mean)2 | – | 1.0004 (1.0000 to 1.0007) | 0.03 | 1.0004 (0.9999 to 1.0008) | 0.09 | 1.0005 (0.9999 to 1.0010) | 0.09 | 1.0008 (1.0003 to 1.0012) | < 0.001* | 1.0002 (0.9999 to 1.0005) | 0.29 | 1.0001 (0.9998 to 1.0003) | 0.63 | 1.0001 (1.0000 to 1.0003) | 0.13 |

| Dependent child in household | None | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Child present | 1.08 (0.87 to 1.35) | 0.49 | 1.16 (0.87 to 1.55) | 0.30 | 1.21 (0.83 to 1.77) | 0.31 | 1.16 (0.88 to 1.55) | 0.30 | 1.02 (0.83 to 1.26) | 0.85 | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.13) | 0.50 | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.12) | 0.66 | |

| Chronic illness (self) | No | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Yes | 0.8 (0.65 to 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.78 (0.58 to 1.04) | 0.09 | 1.33 (0.94 to 1.89) | 0.11 | 0.88 (0.66 to 1.16) | 0.37 | 1.04 (0.86 to 1.26) | 0.70 | 0.84 (0.70 to 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.76 (0.67 to 0.87) | < 0.001* | |

| Household member has chronic illness | No | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Yes | 0.86 (0.66 to 1.12) | 0.27 | 1.12 (0.81 to 1.56) | 0.50 | 0.96 (0.61 to 1.53) | 0.87 | 0.81 (0.56 to 1.16) | 0.24 | 0.98 (0.77 to 1.25) | 0.89 | 0.88 (0.70 to 1.09) | 0.23 | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.31) | 0.20 | |

| Employment status | Not working | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Working | 0.96 (0.77 to 1.19) | 0.70 | 0.76 (0.58 to 1.00) | 0.05 | 1.21 (0.83 to 1.76) | 0.32 | 0.90 (0.68 to 1.19) | 0.45 | 0.90 (0.74 to 1.10) | 0.31 | 0.81 (0.67 to 0.97) | 0.03 | 0.84 (0.73 to 0.97) | 0.02 | |

| Highest earner in household works in a manual occupation | No | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Yes | 1.16 (0.94 to 1.43) | 0.16 | 1.02 (0.78 to 1.33) | 0.90 | 1.17 (0.83 to 1.65) | 0.38 | 1.22 (0.94 to 1.58) | 0.14 | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.12) | 0.39 | 1.03 (0.87 to 1.23) | 0.71 | 0.95 (0.83 to 1.09) | 0.48 | |

| Index of multiple deprivation | 1st (least) to 4th quartile (most deprived) | 1.04 (0.95 to 1.13) | 0.43 | 1.06 (0.95 to 1.19) | 0.30 | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.24) | 0.37 | 1.14 (1.02 to 1.29) | 0.02 | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.03) | 0.20 | 0.93 (0.87 to 1.01) | 0.07 | 1.11 (1.05 to 1.18) | < 0.001* |

| Highest educational or professional qualification | Less than degree | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Degree or higher | 0.98 (0.79 to 1.20) | 0.83 | 0.81 (0.62 to 1.05) | 0.11 | 1.10 (0.79 to 1.54) | 0.57 | 0.95 (0.73 to 1.24) | 0.70 | 0.99 (0.82 to 1.20) | 0.92 | 0.86 (0.73 to 1.02) | 0.09 | 0.95 (0.84 to 1.08) | 0.43 | |

| Ethnicity | White British | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| White other | 1.15 (0.74 to 1.81) | 0.53 | 1.71 (1.06 to 2.78) | 0.03 | 1.09 (0.56 to 2.12) | 0.80 | 1.43 (0.87 to 2.35) | 0.15 | 1.04 (0.68 to 1.60) | 0.85 | 1.44 (0.96 to 2.14) | 0.08 | 0.94 (0.69 to 1.29) | 0.70 | |

| Black and minority ethnicity | 0.82 (0.57 to 1.20) | 0.31 | 1.60 (1.09 to 2.35) | 0.02 | 1.34 (0.82 to 2.21) | 0.24 | 1.18 (0.80 to 1.73) | 0.40 | 0.82 (0.61 to 1.12) | 0.22 | 0.97 (0.73 to 1.31) | 0.86 | 0.82 (0.67 to 1.00) | 0.05 | |

| Overall | χ2(2) = 1.9 | 0.39 | χ2(2) = 8.0 | 0.02 | χ2(2) = 1.4 | 0.50 | χ2(2) = 2.2 | 0.33 | χ2(2) = 1.8 | 0.41 | χ2(2) = 3.5 | 0.18 | χ2(2) = 4.0 | 0.13 | |

| First language | Not English | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| English | 1.23 (0.79 to 1.91) | 0.36 | 1.23 (0.77 to 1.96) | 0.38 | 0.76 (0.43 to 1.33) | 0.33 | 1.18 (0.74 to 1.89) | 0.48 | 1.09 (0.75 to 1.60) | 0.66 | 2.15 (1.44 to 3.19) | < 0.001* | 1.16 (0.90 to 1.49) | 0.26 | |

| Living alone | Not living alone | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Living alone | 1.16 (0.86 to 1.57) | 0.34 | 1.59 (1.10 to 2.30) | 0.01 | 1.96 (1.27 to 3.01) | 0.002* | 1.61 (1.11 to 2.33) | 0.01 | 1.14 (0.86 to 1.50) | 0.36 | 1.23 (0.96 to 1.57) | 0.10 | 1.17 (0.97 to 1.41) | 0.10 | |

| Relationship status | Not partnered | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Partnered | 0.83 (0.65 to 1.05) | 0.12 | 0.82 (0.60 to 1.12) | 0.21 | 0.49 (0.33 to 0.72) | < 0.001* | 0.87 (0.64 to 1.17) | 0.36 | 1.12 (0.89 to 1.40) | 0.33 | 1.14 (0.93 to 1.41) | 0.21 | 1.08 (0.93 to 1.25) | 0.33 | |

| Ever had COVID–19 | Think not | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Think yes | 1.08 (0.84 to 1.40) | 0.55 | 0.95 (0.68 to 1.33) | 0.75 | 1.50 (1.05 to 2.16) | 0.03 | 1.20 (0.90 to 1.60) | 0.22 | 1.06 (0.84 to 1.32) | 0.64 | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.23) | 0.94 | 1.28 (1.14 to 1.44) | < 0.001* | |

| Financial hardship | Range 3 (least) to 15 (most) | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.98) | 0.001* | 1.01 (0.97 to 1.06) | 0.54 | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) | 0.52 | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.03) | 0.66 | 0.95 (0.92 to 0.98) | 0.001* | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.96) | < 0.001* | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.96) | < 0.001* |

†Adjusting for wave, region, gender, age (raw and quadratic), presence of a dependent child in the household, having a chronic illness oneself, having a household member who has chronic illness, employment status, highest earner in household works in a manual occupation, index of multiple deprivation, highest educational or professional qualification, ethnicity, first language, living alone, relationship status, having had COVID-19 before, and financial hardship.

*p ≤ 0.004.

Table 6.

Contextual and psychological factors associated with engaging in highest risk social mixing at different time points in the pandemic.

| Attribute | Level | Rule of six indoors and outdoors | Second national lockdown | Third national lockdown | Rule of six outdoors, no indoor mixing | Rule of six indoors, up to 30 people outdoors | No legal restrictions | No legal obligation to self-isolate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | aOR for engaging in highest risk social mixing (95% CI)† | p | ||

| Been out to work in last week | No | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Yes | 1.34 (1.06 to 1.68) | 0.01 | 1.14 (0.86 to 1.52) | 0.37 | 1.76 (1.23 to 2.53) | 0.002* | 1.74 (1.30 to 2.34) | < 0.001* | 1.23 (1.00 to 1.51) | 0.06 | 1.20 (0.99 to 1.45) | 0.06 | 1.99 (1.71 to 2.32) | < 0.001* | |

| Worry about COVID–19 | 5-point scale (1 = not at all worried to 5 = extremely worried) | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.82) | < 0.001* | 0.65 (0.58 to 0.72) | < 0.001* | 0.65 (0.57 to 0.75) | < 0.001* | 0.67 (0.60 to 0.75) | < 0.001* | 0.71 (0.65 to 0.77) | < 0.001* | 0.76 (0.71 to 0.81) | < 0.001* | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.75) | < 0.001* |

| Perceived risk of COVID–19 to self | 5-point scale (1 = no risk at all to 5 = major risk) | 0.78 (0.71 to 0.85) | < 0.001* | 0.65 (0.58 to 0.73) | < 0.001* | 0.74 (0.64 to 0.85) | < 0.001* | 0.72 (0.64 to 0.81) | < 0.001* | 0.68 (0.62 to 0.74) | < 0.001* | 0.81 (0.75 to 0.87) | < 0.001* | 0.76 (0.72 to 0.79) | < 0.001* |

| Perceived risk of COVID–19 to people in the UK | 5-point scale (1 = no risk at all to 5 = major risk) | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.89) | < 0.001* | 0.62 (0.55 to 0.70) | < 0.001* | 0.60 (0.52 to 0.70) | < 0.001* | 0.71 (0.63 to 0.80) | < 0.001* | 0.78 (0.71 to 0.85) | < 0.001* | 0.82 (0.76 to 0.89) | < 0.001* | 0.77 (0.73 to 0.82) | < 0.001* |

| Coronavirus would be a serious illness for me | 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.82) | < 0.001* | 0.61 (0.54 to 0.68) | < 0.001* | 0.71 (0.61 to 0.82) | < 0.001* | 0.65 (0.58 to 0.73) | < 0.001* | 0.73 (0.67 to 0.79) | < 0.001* | 0.79 (0.73 to 0.85) | < 0.001* | 0.73 (0.69 to 0.77) | < 0.001* |

| I would worry about what others would think of me if I tested positive for coronavirus | 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | 0.87 (0.81 to 0.95) | 0.001* | 0.85 (0.76 to 0.94) | 0.002* | 0.90 (0.79 to 1.03) | 0.12 | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.00) | 0.06 | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.95) | 0.001* | 0.81 (0.76 to 0.87) | < 0.001* | 0.83 (0.79 to 0.87) | < 0.001* |

| Someone could spread coronavirus to other people, even if they do not have symptoms yet | 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.03) | 0.13 | 0.72 (0.63 to 0.82) | < 0.001* | 0.68 (0.57 to 0.80) | < 0.001* | 0.75 (0.66 to 0.86) | < 0.001* | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.95) | 0.004* | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.06) | 0.52 | 1.00 (0.94 to 1.07) | 0.98 |

| My personal behaviour has an impact on how coronavirus spreads | 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | 0.83 (0.76 to 0.91) | < 0.001* | 0.74 (0.67 to 0.82) | < 0.001* | 0.74 (0.64 to 0.85) | < 0.001* | 0.70 (0.63 to 0.78) | < 0.001* | 0.88 (0.81 to 0.95) | 0.001* | 0.93 (0.87 to 1.00) | 0.05 | 0.91 (0.86 to 0.96) | < 0.001* |

| I think the risks of coronavirus are being exaggerated | 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | 1.19 (1.10 to 1.28) | < 0.001* | 1.47 (1.33 to 1.62) | < 0.001* | 1.42 (1.25 to 1.61) | < 0.001* | 1.37 (1.24 to 1.51) | < 0.001* | 1.18 (1.09 to 1.27) | < 0.001* | 1.14 (1.06 to 1.22) | < 0.001* | 1.15 (1.10 to 1.21) | < 0.001* |

| Information from the UK Government about coronavirus can be trusted | 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | 0.84 (0.77 to 0.90) | < 0.001* | 0.79 (0.71 to 0.88) | < 0.001* | 0.84 (0.74 to 0.96) | 0.009 | 0.79 (0.71 to 0.87) | < 0.001* | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.92) | < 0.001* | 0.86 (0.80 to 0.91) | < 0.001* | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.97) | 0.001* |

| Information from the UK Government about coronavirus is biased or one-sided | 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) | 1.03 (0.95 to 1.12) | 0.51 | 1.05 (0.94 to 1.18) | 0.37 | 1.17 (1.02 to 1.35) | 0.03 | 1.08 (0.97 to 1.20) | 0.17 | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.15) | 0.10 | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.05) | 0.60 | 0.95 (0.90 to 1.00) | 0.04 |

†Adjusting for wave, region, gender, age (raw and quadratic), presence of a dependent child in the household, having a chronic illness oneself, having a household member who has chronic illness, employment status, highest earner in household works in a manual occupation, index of multiple deprivation, highest educational or professional qualification, ethnicity, first language, living alone, relationship status, having had COVID-19 before, and financial hardship.

*p ≤ 0.004.

At most timepoints (five or six out of seven), engaging in highest risk social mixing was associated with younger age, not agreeing that you would worry about what others would think of you if you tested positive for COVID-19, not agreeing that your personal behaviour had an impact on how COVID-19 spread, and not agreeing that information from the UK Government about COVID-19 could be trusted (Tables 5, 6). Lower financial hardship and not agreeing that someone could spread COVID-19 even if asymptomatic were associated with engaging in highest risk social mixing at four timepoints, while having been out to work was associated with engaging in highest risk social mixing at three time points (Tables 5, 6).

Men were more likely to engage in highest risk social mixing during the third lockdown and after the legal obligation to self-isolate if symptomatic or positive for SARS-CoV-2 was removed (Table 5).

In the third national lockdown, engaging in highest risk social mixing was associated with living alone and not having a partner (Table 5). When the rule of six was in place outdoors but there was no indoor mixing, later survey wave was associated with engaging in highest risk social mixing (Table 5). When there were no legal restrictions on social mixing, speaking English as your first language was associated with engaging in highest risk social mixing (Table 5).

When there was no legal obligation to self-isolate if symptomatic or positive for SARS-CoV-2, highest risk social mixing was associated with thinking that you had already had COVID-19 and living in a more deprived area; having a chronic illness was associated with not engaging in highest risk social mixing (Tables 5, 6).

Correlations between psychological factor items are reported in Supplementary Materials 4. Most items were significantly correlated.

Discussion

We computed a composite measure of social mixing associated with a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, taking into account setting, physical distancing, number of households present, and number of people from other households present. We described how people’s social mixing patterns varied between September 2020 and April 2022. This measure of social mixing shows clear variation in line with UK Government guidance in place at the time of data collection, including low rates of any social mixing during the third national lockdown, an increase in lower risk socialising (outdoors) between April and May 2021, and an increase in highest risk socialising (indoors) following the opening of indoor hospitality and removal of any legal restrictions on social mixing. Our analyses replicate findings investigating contact patterns during the pandemic4, and extend them by suggesting that changes occurred not only in the number, but also in the nature, of social interactions.

Psychological factors were consistently associated with engaging in highest risk social mixing. Similar to other studies, we found that highest risk social mixing was associated with lower perceived risk of COVID-1920, being less worried about COVID-1921,22, and lower perceived severity of COVID-194,11. As in other pandemics, believing that the risks of the virus were being exaggerated was associated with not engaging with protective behaviours23. While strong and consistent associations between worry about, perceived risk and perceived severity of illness suggest that increasing worry and risk may result in increased protective behaviours, messaging designed to increase worry and perception of risk should only be contemplated when perceived risk is disproportionately low and in tandem with messaging highlighting the effectiveness of protective behaviours24.

Lower knowledge that SARS-CoV-2 can spread even when asymptomatic was consistently associated with engaging in highest risk social mixing. Other studies have also shown that people with lower knowledge of transmission are less likely to intend to adhere to the test, trace, and isolate system25. People who agreed that their personal behaviour had an impact on how COVID-19 spreads were less likely to engage in highest risk social mixing. This is in line with other evidence on internal health locus of control and uptake of health behaviours14,26–28. Increasing knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 transmission and emphasising that an individual’s behaviour can affect the spread of the virus may encourage uptake of protective behaviours such as lower risk social mixing. Associations between highest risk social mixing and disagreeing that information about COVID-19 from the UK Government can be trusted suggest that messaging about such issues may be better received if it is communicated by sources other than the Government, such as the National Health Service (NHS) or public health agencies.

Highest risk social mixing was associated with socio-demographic characteristics, namely younger age, having been out to work, and lower financial hardship. These findings may in part reflect the fact that younger people have higher rates of social contacts29,30, and that people who attend work have on average twice the number of social contacts than those working from home31. It also follows that, if people have been in close contact with others in the workplace, they may be more comfortable and perceive less risk in socialising outside of work. People in greater financial hardship may be less likely to be able to afford costs associated with frequent higher risk socialising (e.g. transport to and from meeting points, eating or drinking at hospitality venues).

After the removal of all legal restrictions on socialising on 19 July 2021, the UK Government moved to a system where individuals were expected to understand and manage their own risk, rather than follow rules8. However, risk perception is complex32, and evidence suggests that people have difficulty interpreting their own risk in different situations33. It is notable that when the legal obligation to self-isolate if symptomatic or positive for SARS-CoV-2 was removed, a time where SARS-CoV-2 cases in England were high, people with chronic health conditions were less likely to engage in highest risk social mixing, perhaps pointing to a continuing impact of high risk perception among this group. While messaging may encourage people to engage in less risky social mixing, our evidence and that from elsewhere suggests that the biggest driver of mixing behaviour is the restrictions in place at the time34–37. If they are needed again, obtaining large reductions in mixing as a result of communication alone may prove challenging.

Strengths of this study include that it gives a nuanced insight into social mixing behaviour over the course of the pandemic, spanning different restrictions, including the removal of all legal restrictions on social mixing. Limitations include: (1) the use of an online sample, whose views and behaviours may not be representative of the wider population, although associations within the data should remain valid38. (2) Surveys were cross-sectional, therefore we cannot imply causation. (3) We asked participants for details about the most recent time they met with people from another household to minimise recall bias. As surveys were conducted at the start of the week (usually Monday to Tuesday or Wednesday), people’s most recent instance of social mixing was likely to have been during the preceding weekend. Socialising patterns during the week may be different. (4) Participants were asked about their behaviour in the previous week. In some cases, this may have overlapped with a change in restrictions. (5) Patterns of social mixing may not be as significant predictors of COVID-19 risk as other aspects of a person’s life, such as their work environment, commuting and interactions with social and healthcare. (6) We did not include vaccination status as an explanatory variable in our regression analyses. All UK adults became eligible to have the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine on 17 June 2021 (with their second dose 8 weeks after)39. Before this date, only certain age groups were eligible, which would have confounded analyses. To keep analyses across time points consistent, we did not include vaccination status in our final time point.

This study outlines patterns of social mixing between September 2020 and April 2022 using a composite measure drawing together information about factors influencing transmission risk (setting, distancing, and number of other households and individuals from other households present). Mixing behaviour varied according to the restrictions in place at the time. Messages targeting psychological factors, such as increasing knowledge about SARS-CoV-2 transmission and that an individual’s behaviour can impact the spread of the virus, may promote lower risk social mixing. However, should Government deem it necessary to significantly reduce risky social mixing in a short space of time, it is likely that a reimposition of restrictions may be necessary.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

All authors conceptualised the study. L.S. completed analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. H.W.W.P., R.A., N.T.F., S.M. and G.J.R. contributed to subsequent drafts. All authors approved the submitted manuscript and are personally accountable for their own contributions.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme. Surveys were commissioned and funded by Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), with the authors providing advice on the question design and selection. LS, RA and GJR are supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response, a partnership between the UK Health Security Agency, King’s College London and the University of East Anglia. RA is also supported by the NIHR HPRU in Behavioural Science and Evaluation, a partnership between the UK Health Security Agency and the University of Bristol. HWWP has received funding from Public Health England and NHS England. NTF is part funded by a grant from the UK Ministry of Defence. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, UK Health Security Agency, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Ministry of Defence.

Data availability

The data are owned by the UK’s Department of Health and Social Care, so no additional data are available from the authors.

Competing interests

All authors had financial support from NIHR for the submitted work; RA is an employee of the UK Health Security Agency; HWWP has received additional salary support from Public Health England and NHS England; HWWP receives consultancy fees to his employer from Ipsos MORI and has a PhD student who works at and has fees paid by Astra Zeneca; NTF is a participant of an independent group advising NHS Digital on the release of patient data. At the time of writing GJR is acting as an expert witness in an unrelated case involving Bayer PLC, supported by LS. All authors were participants of the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies or its subgroups.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-14431-3.

References

- 1.Jarvis CI, et al. Quantifying the impact of physical distance measures on the transmission of COVID-19 in the UK. BMC Med. 2020;18:124. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01597-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.PHE Transmission Group. Factors Contributing to Risk of SARS-CoV2 Transmission Associated with Various Settings. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/945978/S0921_Factors_contributing_to_risk_of_SARS_18122020.pdf (2020). Accessed 12 Oct 2021.

- 3.Cabinet Office. COVID-19 Response—Spring 2021 (Summary). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-response-spring-2021/covid-19-response-spring-2021-summary (2021). Accessed 12 Oct 2021.

- 4.Gimma A, et al. Changes in social contacts in England during the COVID-19 pandemic between March 2020 and March 2021 as measured by the CoMix survey: A repeated cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2022;19:e1003907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michie S, et al. Factors associated with non-essential workplace attendance during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK in early 2021: Evidence from cross-sectional surveys. Public Health. 2021;198:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown J, Kirk-Wade E. Coronavirus: A History of English Lockdown Laws. House of Commons Library; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prime Minister's Office. Prime Minister Confirms Move to Step 4. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-confirms-move-to-step-4 (2021). Accessed 12 Oct 2021.

- 8.Cabinet Office. Coronavirus: How to Stay Safe and Help Prevent the Spread. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/covid-19-coronavirus-restrictions-what-you-can-and-cannot-do?priority-taxon=774cee22-d896-44c1-a611-e3109cce8eae (2021). Accessed 12 Oct 2021.

- 9.Prime Minister's Office. Prime Minister Sets Out New Measures as Omicron Variant Identified in UK: 27 November 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-sets-out-new-measures-as-omicron-variant-identified-in-uk-27-november-2021 (2021). Accessed 11 May 2022.

- 10.Prime Minister's Office. Prime Minister Confirms Move to Plan B in England. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-confirms-move-to-plan-b-in-england (2021). Accessed 11 May 2022.

- 11.Smith LE, et al. Factors associated with adherence to self-isolation and lockdown measures in the UK: A cross-sectional survey. Public Health. 2020;187:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett C, Cheung KL. Knowledge, socio-cognitive perceptions and the practice of hand hygiene and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study of UK university students. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:426. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10461-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eraso Y, Hills S. Intentional and unintentional non-adherence to social distancing measures during COVID-19: A mixed-methods analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0256495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright L, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Patterns of compliance with COVID-19 preventive behaviours: A latent class analysis of 20,000 UK adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2021 doi: 10.1136/jech-2021-216876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith LE, et al. Adherence to the test, trace, and isolate system in the UK: Results from 37 nationally representative surveys. BMJ. 2021;372:n608. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government . The English Indices of Deprivation 2019. Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith LE, et al. How has the emergence of the Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern influenced worry, perceived risk, and behaviour in the UK? A series of cross-sectional surveys. Open Sci. Framew. 2022 doi: 10.31219/osf.io/rpcu2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.GOV.UK. Regional Ethnic Diversity. https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/national-and-regional-populations/regional-ethnic-diversity/latest#areas-of-england-and-wales-by-ethnicity (2020). Accessed 11 May 2022.

- 19.GOV.UK. Cases in England. https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/cases?areaType=nation&areaName=England (2022). Accessed 11 May 2022.

- 20.Dryhurst S, et al. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020 doi: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kooistra EB, Van Rooij B. Pandemic compliance: A systematic review of influences on social distancing behaviour during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak. PsyArXiv. 2020 doi: 10.31234/osf.io/c5x2k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noone C, et al. A scoping review of research on the determinants of adherence to social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Psychol. Rev. 2021 doi: 10.1080/17437199.2021.1934062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin GJ, Potts HWW, Michie S. The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A H1N1v) on public responses to the outbreak: Results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK. Health Technol. Assess. 2010;14:183–266. doi: 10.3310/hta14340-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters GJ, Ruiter RA, Kok G. Threatening communication: A critical re-analysis and a revised meta-analytic test of fear appeal theory. Health Psychol. Rev. 2013;7:S8–S31. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2012.703527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith LE, et al. Intention to adhere to test, trace, and isolate during the COVID-19 pandemic (the COVID-19 rapid survey of adherence to interventions and responses study) Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norman P, Bennett P, Smith C, Murphy S. Health locus of control and health behaviour. J. Health Psychol. 1998;3:171–180. doi: 10.1177/135910539800300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steptoe A, Wardle J. Locus of control and health behaviour revisited: A multivariate analysis of young adults from 18 countries. Br. J. Psychol. 2001;92:659–672. doi: 10.1348/000712601162400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith LE, et al. Tiered restrictions for COVID-19 in England: Knowledge, motivation and self-reported behaviour. Public Health. 2022;204:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mossong J, et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e74. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wallinga J, Teunis P, Kretzschmar M. Using data on social contacts to estimate age-specific transmission parameters for respiratory-spread infectious agents. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006;164:936–944. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jarvis, C., Edmunds, J. & CMMID COVID-19 Working Group. Social Contacts in Workplace the UK from the CoMix Social Contact Survey. https://cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19/reports/comix/Comix%20Report%20contacts%20in%20the%20workplace.pdf (2021). Accessed 12 Oct 2021.

- 32.Weinstein ND. What does it mean to understand a risk? Evaluating risk comprehension. JNCI Monogr. 1999;1999:15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Damman OC, Bogaerts NMM, van den Haak MJ, Timmermans DRM. How lay people understand and make sense of personalized disease risk information. Health Expect. 2017;20:973–983. doi: 10.1111/hex.12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coletti P, et al. CoMix: Comparing mixing patterns in the Belgian population during and after lockdown. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:21885. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78540-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foad CMG, Whitmarsh L, Hanel PHP, Haddock G. The limitations of polling data in understanding public support for COVID-19 lockdown policies. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2021;8:210678. doi: 10.1098/rsos.210678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Latsuzbaia A, Herold M, Bertemes J-P, Mossong J. Evolving social contact patterns during the COVID-19 crisis in Luxembourg. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0237128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ringa N, et al. Social contacts and transmission of COVID-19 in British Columbia, Canada. Front. Public Health. 2022 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.867425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kohler U. Possible uses of nonprobability sampling for the social sciences. Surv. Methods Insights Field. 2019 doi: 10.13094/SMIF-2019-00014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.NHS England. NHS Invites All Adults to Get a COVID Jab in Final Push. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2021/06/nhs-invites-all-adults-to-get-a-covid-jab-in-final-push/ (2021). Accessed 11 May 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are owned by the UK’s Department of Health and Social Care, so no additional data are available from the authors.