Abstract

COVID-19 has had a profound impact on agriculture, nutrition, and consumption impacting food system value chain, creating shortage of labor, and increasing food inflation. Global lockdown leading to logistic restrictions has forced the producers and consumers to explore new markets. Despite various social protection systems and safety nets, informal sector has been vulnerable, bearing the brunt in dealing with the challenges till their livelihood return to normal. Double disasters greatly impact small island developing states or other nonagrarian economies that are highly vulnerable to food insecurity. FAO predicts that undernourished people could rise between 83 million to 132 million in 2020 due to pandemic. Despite the challenges some stakeholders across the value chain have experienced positive returns. This chapter would take a stock of positive and negative implications on various stakeholders in agriculture and food system value chain in India and Thailand. It would share cases, where digital technologies reacted rapidly to mitigate the impact and highlight additional strategies to build resilient agriculture systems in the future.

Keywords: Agriculture, COVID-19, Digital agriculture, Food systems, Value chain

1. Background

COVID-19 has brought substantial disruptions to the economies with a loss of USD12.5 trillion of cumulative output (IMF, 2020). It has impacted not only the agrarian economies domestically but has also hit the overall global supply chain. Food production, consumption, and purchasing behavior changed the markets forcing them to evaluate the impact of the pandemic and adopt new pathways in the process. World Economic Output report indicates that despite the volatility, the rebound of primary commodity price index (CPI) varied by sectors and regions based on the outbreak, storability, and supply elasticity of the commodity. The primary CPI that provides the weighted average of selected CPI representing global import in 3 years (2014–16) normalized to 100 at 2016 year prices (IMF, 2019) depicts a sharp fluctuation over the years (Fig. 23.1 ). The CPI for food commodities has declined from 105.4 in January 2020 to 93.1 in April 2020, thereafter increased continuously reaching 101.8 in August 2020. The trend further indicates that the price recovery of some agricultural raw materials picked up later than that of the metals and energy products although the food and beverage price index increased by 0.7% whereas demand for agricultural raw material and animal feed declined initially. Also prices were less affected as changes were wide dispersed across agricultural commodities (IMF, 2020).

Figure 23.1.

Movement in commodity price indices.

Data source: imf.org.

Most staple food crops such as maize, wheat, soyabean, and palm oil have been stable or declined due to large global supplies and the collapse of crude oil initially during the pandemic. Also, the meat price index fell by 7.1% mainly because of the spread of pandemic, reducing consumption and demand which further led to reduction in processing and supply to retail markets. The rice price still went up by 12.6% whereas the corn price declined by 13% because of the ethanol demand declining to its lowest in last 10 years in May. Huge global supplies of soybean further reduced the price by 13%. The supply and demand side challenges including supply disruptions, export restrictions further added to the risks. Some agricultural products such as Thailand rice, arabica coffee, and oranges have reflected an increase in price during COVID-19 period (IMF, 2020).

Agricultural activities ideally follow a schedule based on crop calendar with reference to the season and weather. Disruption in any phase of the value chain could impact yield and output leading to losses (FAO, 2020a). Loss of incomes and food inflation have substantially hit the lower-middle-class communities creating tensions in the markets and increasing food security risks. Disruption in case of plantation, crop management, harvesting, and marketing has been reported in various parts of the world. The major impact has been reported for the distribution of perishable fruits and vegetables, meat, and fisheries impacting the quality of diets. Various reports indicate that farmers were forced to destroy their produce due to discontinuity of logistics during the restriction period. For instance, 14 million liters milk per day are dumped in the United States, 5 million liters per week at risk in England, US chicken processor smashing 750,000 unhatched eggs per week (BBC, 2020), and loss of tea plants in India (Aday & Aday, 2020). Food loss and waste are already raising eyebrows as around 14% of food produced globally is lost in between the production and retail supply chain and more wasted at the retail and consumption phases. Also, food loss and waste attribute to 6% of total water withdrawals for agriculture (United Nations, 2020b). The pandemic is further complicating the challenges of food loss and waste management. Many fish farmers faced losses as they were unable to sell their products or had to sell their products at very low prices (FAO, 2020b,c).

In the times of COVID-19, increasing population growth rates and reduction in the remittances in developing countries, insufficient supplies, insufficient access, and ineffective utilization are commonly talked about as major contributors to food insecurity. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) indicates that according to the postdisaster needs assessment during 2003–13, climate change and natural disasters were observed to contribute 21.8% of damage and losses in the agricultural sector. COVID-19 has made these challenges more daunting. Agriculture remains the core for various economic activities globally, where many countries still follow traditional ways through small holder farmers. Market restrictions and lockdown have forced many small-scale farmers to liquidate their assets to manage their minimum needs. Children have been pulled out from school because fees were unaffordable to many such small players in the agriculture sector. At the same time, some recovery response initiatives like alternative marketing through online or e-commerce platforms have been beneficial for many small holder farmers. While many countries were facing the brunt of COVID-19 in terms of economic contraction, Indian agriculture sector grew at 3.4% in the second quarter while India's GDP contracted by 7.5% in the second quarter, recording a 23.9% decline in the first quarter according to the National Statistical Office (NSO) (The Hindu, 2020a).

1.1. COVID-19 and agriculture

The impacts of COVID-19 on agriculture have not been quantified completely but disruptions have been observed majorly in case of distribution of perishable food products, livestock value chain, declining demands, and exports globally. Inadequate storage facilities, nondiversifies supplies and labor migration have been some major vulnerabilities in developing economies. Considering these challenges governments have been supporting through outputs, inputs, and credit support and allowing labor and transportation movement related to agricultural services. Many laborers migrated back to the villages without employment adding up pressure on forests, natural resources and increasing illegal trafficking, mining, and deforestation. The Brazilian Space Agency recently released satellite data indicating a 50% rise in deforestation in Amazon rainforest (ABC News, 2020). COVID-19 coincided with the harvest season and disrupted the collection on nontimber forest products (NTFPs) in Odisha's forest, which is considered labor intensive in India (The Hindu, 2020b).

Most countries are now focusing on strengthening their domestic market in terms of production, distribution, and consumption. Emphasis on consuming local has become the new normal and is being strongly advocated in many countries. Product diversification based on the nutrition needs is being considered as a vital strategy for agricultural development and management. Traceability is being highlighted as consumers have become more particular about the quality and safety of food. Central banks are looking at small farmers and micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) liquidity and their convenient access to credit and finance.

2. Impact on Indian agriculture

India has recorded the second highest COVID-19 cases in the world after the United States with 8,313,876 confirmed cases and 123,611 deaths (WHO, 2020). With a population over 1.3 billion and poverty rate of about 23%, the pandemic has brought an unprecedented shock to the Indian economy. The agriculture sector is key to the state of rural demand with increased agricultural GDP from 2.4% in 2019 to 4% in 2020. Growth in rural wages was subdued in the pre-COVID period, particularly for agricultural labor in both nominal and real terms, partly due to the slowdown in the construction sector. However, there has been disruption in prices of agricultural commodities due to closure of agricultural produce market committees (APMCs)/Mandis that had affected agricultural supply chain. Since supply chains have not been working properly, vast amounts of food started getting wasted leading to massive losses for Indian farmers. A survey by Azim Premji University (2020) shows that 37% of farmers were unable to harvest, 37% have been sold at reduced prices, and 15% were unable to sell the harvest. Thus, the government should work on smoothing the wholesale and retail marketing and initiating procurement operations. Dairy farmers and poultry farmers have experienced huge loss owing to outbreak of pandemic. Due to lack of demand, the dairy farmers dumped the milk in the drains. Millions of small poultry farmers across the country particularly in the states of Maharashtra, Karnataka, Odisha, and Andhra Pradesh were struggling after sales have crashed 80% over these false claims. Many farmers have also dumped their seasonal agricultural and horticultural products such as fruits and vegetables. Restricted supply chain and low demand had led to huge losses of about 27,000 crore Indian rupees in the poultry industry (FICCI, 2020).

As the COVID-19 pandemic threatens India, MSMEs and agriculture sectors are most badly hit. The Agricultural and allied industry are pacing up to keep employees and consumers safe, while still providing food, agricultural inputs, machineries, services, and feed. Considering food industry as critical was allowed to operate as usual despite lockdown in the nation. Major agribusiness firms have increased hygiene procedures and are taking measures to ensure safety. In the country, restaurants and food chains have seen significant drop in the sales as most of the people are buying groceries and cooking their own food. This has shifted the supply chain from stores to e-commerce.

A survey by NABARD in 2018 shows that only 23% of rural income is from agriculture (The Indian Express, 2018). Around 44% of income is from wage labor, 24% from government/private service, and 8% from other enterprises. The rural wages are declining due to the arrival of migrant workers from the cities and urban areas have been affected more than rural areas because of high density, in-migration, and disruption in food supply chains (Down To Earth, 2021).

3. Impact on Thailand agriculture

Thailand's agriculture sector employs 30% of labor force contributing to 10% of GDP in 2019. The agricultural productivity has declined in the last three decades pulling down 40% of the farming households below poverty line, earning less than 32,000 baht annually (United Nations, 2020a). The debt levels of farmers have escalated, aging farmers have increased, and young farmers have declined in the past few decades. According to farmers registration in 2017, 40% of farm households lack land ownership, only 42% have access to water resources and only 26% benefit from the irrigation facilities. Thailand government declared nation-wide state of emergency on March 25 with soft lockdown allowing essential services like supermarkets, delivery, and takeaway of food to operate.

According to FAO, Thailand farming households have faced greater loss of income about 39% as compared to 16% for general households during the pandemic. Employment rate in Bangkok and nearby provinces during the lockdown increased to 9.6% according to the Kasikorn Research Centre (The Nation, 2020). Yet, many small-scale farmers are still not registered in the government system and lack access to social safety nets provided by the government. Due to recent droughts and other structural challenges such as water resources, soil quality, technology applications, and logistics, most of the migrant workers moving back to the farmland remain unemployed making the situation worse.

The government strongly indicated its support in promoting online platforms and channels for reaching the market and also supporting the migration of labor in agriculture. Thailand produced 28.4 million tons of rice in 2019, with an estimated consumption of 13.3 million tons and seed production worth 1.37 million tons still managing surplus for export purposes. Also, the fisheries/sea food consumption is estimated at about 17.24% of total production and other basic products have been estimated to be sufficient for domestic consumption (Food Navigator Asia, 2020). Ministry of Commerce established focus areas called the seven “war rooms” to monitor rice, fruits and vegetables, processed food, livestock, medical supplies, logistics and delivery, and animal feed. Some products like rice and eggs were hoarded as panic buying and the government had to ban the export of eggs till the end of April 2020. Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MOAC) launched policies for farmers to take new loan, extend loan repayment period, and provide aid of 5000 baht each to about 10 million farmers for a period of 3 months (Agroberichten Buitenland, 2020).

Thailand domestic markets account for 62% of poultry production, 85% of fisheries, and seafood produces accounts for export with fruits exports worth 88,000 million baht per year. Production has been stable while huge decline in exports has been observed. Thailand rice export forecasts were slashed to 6.5 million tons, the lowest in 20 years because of the early year drought and also the rise in prices making it uncompetitive in global market. Although export of Thai jasmine rice increased by 63% because of the panic purchasing done during COVID-19 by countries (Reuters, 2020b).

The National Statistical Office (NSO) suggests that Thai household spent about 33.9% of their expenditure on foods and beverage based on their preferences and taste rather than cleanliness and nutrition (FFTC-AP, 2020). Post-COVID-19 the consumers' food preferences and diet pattern have been reflected in their change in lifestyle. More concerns are raised regarding the health, food safety, and hygiene making the consumers more conscious and aware engaging more digitally. Mckinsey and Company research indicated that consumers seemed worried about the increasing meal cost because of the takeout, delivery, and ready meal consumption preferences. 41% respondents suggested that grocery spending has increased and 92% respondents who have switched stores will move back to their original stores post-COVID-19 situations (McKinsey & Company, 2020).

4. Impacts of COVID-19 on agricultural food system value chain in India and Thailand

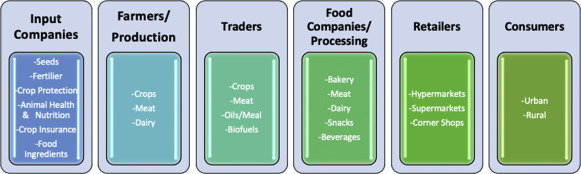

COVID-19 continues to affect agriculture, nutrition, and food systems as global economy slowdown and human development gets adversely impacted. A huge market shift has taken place due to the changes in demand and supply postmovement restrictions forcing producers to find new outlets for food production. Agricultural supply chains or food system value chains in India and Thailand are more or less similar which is depicted in Fig. 23.2 .

Figure 23.2.

Agricultural food system value chain.

Source: Authors.

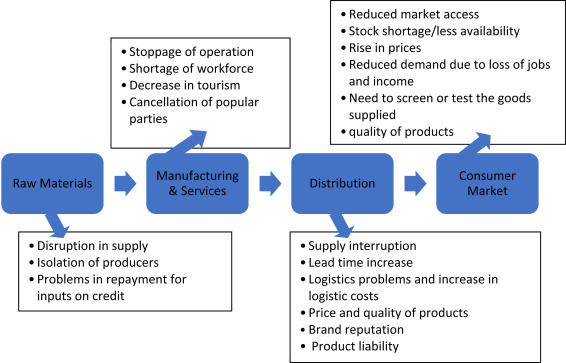

The chain impacts of the pandemic resulted in disruption in interindustry interactions and have strong impact on the agri-supply chain and overall economic growth of both the countries as stated in Fig. 23.3 . The input industry was delinked from the producers to a significant extent resulting in disruption in supply. In many cases, the payments toward inputs taken on credit were not repaid to the input suppliers, disrupting the production process of inputs. The manufacturing and service sectors were greatly affected due to stoppage of operations owing to shortage of workforce. Reduction in demand, decrease in tourism, and other marketing activities further reduced the production activities and increased the losses due to glut.

Figure 23.3.

Pandemic risks associated with food supply chain.

Source: Authors.

The pandemic lockdown period coincided with the peak Rabi season in India which raised concerns across the entire value chain from harvesting, procurement operations, disruption in supply of perishable products, storage facilities, and product marketing (Fig. 23.3). Increased interstate migration created panic when the Union Home Ministry allowed the movement of farmers, laborers, and harvesting machines during the lockdown. Workers without agricultural skills too migrated to rural areas exacerbating the existing problem of workforce shortage in various food production and processing units.

The economic losses were strongly driven by logistics problems. Difficulties in logistics and trade also influenced the pricing of agricultural products as well. The traders and consumer markets were greatly affected due to reduced market access, stock shortage/less availability, rise in prices, reduced demand due to loss of jobs and income, need to screen or test the goods supplied, and apprehension of poor quality of available products.

The recent ADB-ILO report, titled “Tackling the COVID-19 youth employment crisis in Asia and the Pacific,” estimated 28.8% of total youth job loss in the agriculture sector of India due to COVID-19 (ADB-ILO, 2020). The report says, despite all these activities during lockdown there has been good agricultural output in the last two seasons, but the supply and logistical bottlenecks have increased food inflation. Food inflation along with shortage of labor have further started impacting prices of nonfood products and services.

5. Implications for the stakeholders

The section tries to evaluate some positive and negative impacts of COVID-19 on various stakeholders along the value chains in India (Table 23.1 ) and Thailand (Table 23.2 ).

Table 23.1.

Implications of COVID-19 for stakeholders along the food supply chain in India.

| Food chain | Organizations | Positive impact | Negative impacts | Remedial measures taken | Challenges/comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input industries (seeds and Fertilizers) |

PI Industries Limited, India Integrated in 1946, PI industries Ltd. contributes to the supply chain of Agchem starting from R&D to production, and solutions. It collaborates with innovators worldwide to produce novel products and crop safety technologies, with operations in India, China, Japan, and Germany. |

|

Two products launched—Londax power (insecticide) and Shield (fungicide). 18 new patent applications filed during H1′FY21 including intermediaries of COVID-19. |

COVID-19 disruption to operations and movement of goods impacted in a limited manner with all manufacturing facilities operational and capacity utilization building back to pre-COVID levels. | |

| Input supplier (agri-inputs such as seeds, pesticides, fertilizers) |

Bharat Group Bharat Group was established four decades ago with its three constituent companies, viz. Bharat Rasayan Ltd., Bharat Insecticides Ltd., and BR Agrotech Ltd. The group has established a strong presence in domestic and international markets and has come a long way to be a US$ 167 million enterprise. |

Bharat Group products are available to the farming community at their doorsteps through a network of 26 warehouses, 5500 distributors and a large number, of retailers. Bharat Rasayan Ltd. had a turnover of 1231.87 crores rupees, an increase of about 23.84% over previous year (Bharat Rasayan Limited, 2020). |

Though company did not face much difficulty in its usual business, the local disruptions in supply of agri-inputs have occurred at some regions because of transport difficulties. | Good performance of the company is due to the fact that the agri-inputs (seeds and fertilizers and pesticides) were supplied by the company in time before travel restrictions were put in place. Because of relaxation of COVID restrictions by Government, the company did not face much difficulty in its usual business. | |

|

Input supplier (agri-inputs: fertilizers) |

Rashtriya Chemicals and Fertilizers (RCF) Limited A leading fertilizers and chemicals manufacturing company with about 75% of its equity held by the government of India. Some of its products have very high brand equity in rural India such as “Ujjwala” (Urea) and “Suphala” (complex fertilizers). |

The manufacturing unit in Trombay, Maharashtra, suspended operations but has recovered well post April 2020 (Rashtriya Chemicals and Fertilizers Limited, 2020). |

|

|

|

| Input supplier (prawn and fish feeds) |

Avanti Feeds Limited A leading manufacturer of prawn and fish feeds, processes and exports shrimp from India. It has a joint venture with Thai Union frozen products PCL., the world's largest seafood processors and leading manufacturer of prawn and fish feeds in Thailand with integrated facilities from hatchery, shrimp, and fish processing, and exports. |

Q2FY21 reported consolidated revenues of Rs. 11,316.2 million, a growth of 6.3% YoY. | The stock price performance declined in March 2020 and bounced back positively since November 2020. | The demand for shrimp has dropped globally by about 30–35% as an immediate reaction of COVID-19 due to closure of restaurants, malls, and public eating places (Avanti Feeds Limited, 2020). | |

| Input supplier (poultry products) |

Suresh Bhatlekar Poultry Farm Located in Belgavi, Karnataka, India consists of total 35 poultry farms, sells meat, egg, chicken to retailers and meat processors. |

In the pre-COVID era, the overall domestic poultry industry witnessed a healthy 13% revenue growth in the financial year 2019. | As a result of the rumors surrounding the spread of coronavirus through animals and chicken, the lockdown turned out to be a double whammy for poultry players. Because of less demand, chicken was sold by the farm at Rs 60–150 per kg in retail compared with Rs 180–200 during pre-COVID period (Singh, 2020). | The farm generated awareness on the government circular on rumor that helped the consumers to regain the confidence and started consuming the poultry products as usual. | |

| Producer/processor |

Nestle India One of the world's largest food processing companies with 435 production factories operating in 35 countries, more than 15,000 food products are sold across 189 countries. |

Demand for food and drinks consumed at home remained strong during lockdowns, while sales of products consumed outside home and on the go—about 15% of Nestle's sales—fell by 26.4% in the third quarter of 2020 (Reuters, 2020a). | Due to COVID-19, nestle shares went down by 0.2% in the food sector index. The result was not good for the company during the financial year 2020. | The work-from-home policy adopted by nestle India throughout the pandemic has pushed the food sector to adopt a decentralized approach to its business. Unlike earlier, when bulk of the decision-making about its marketing and sales strategies, distribution, or manufacturing happened at its headquarters in Gurgaon, the company decentralized a lot of its decision-making to the factories and local sales areas. | |

|

Farmer/producer/processor |

All India Meat and Livestock Exporters Association Traditional meat drying, preparation of natural sausage casings from intestines of slaughter animals, the comprehensive listing and description of nonmeat ingredients, etc., are the major activity of meat processing plant. |

Due to COVID-19, some processing plants were working with less labor but could meet the demand. According to the company and trade bodies, buffalo meat exports rose 15% in August YoY basis and were expected to reach pre-COVID levels in the October–December quarter. Exporters indicated demand from Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia had boosted sales and the trend would continue. |

The COVID pandemic forced meat processing factories in India to shut down from the last week of March 2020 until the end of April. Disruption in the delivery and supply chains hit the industry. Various meat processing plants had shut down and have been forced to operate at reduced capacity. Low demand from meat processors has left producers with unsold mature animals. In the first quarter of 2020–21, buffalo meat exports fell 52% on YoY basis. Total meat exports from India in 2019–20 fell from 9.93% to 1.15 million tonnes, valued at Rs 22,668 crore (The Economic Times, 2020a). |

The association reduced the workforce during the pandemic and looked for better time for revival of demand. After revival of demand during last quarter of 2020, the association could bring back the business to the pre-COVID level. |

Resumption of international travel by tourists and business will give a boost to the overall demand. If passenger flights resume, then it will take about a quarter to get exports to the normal levels. |

| Producer/processor |

Britannia Industries Being a leading player in FMCG sector, the company produces food bakery products, gourmet foods, dairy products, etc., for majority of Indian consumers. Britannia, which had a revenue of Rs 10,482.45 crore in FY 2018–19, operates 15 manufacturing units in India, which are widely spread in states including Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Assam, Uttaranchal, Bihar, Odisha, and Maharashtra. |

Britannia industries witnessed double-digit growth during the pandemic-induced lockdown. The revenue rose by nearly one-third in the April–June quarter of 2020 with its sales and profit after tax (PAT) growth estimated around 22% and 51%, respectively. | Britannia reduced its utilization to 65% of its capacity and focused on optimizing limited manpower (The Economic Times, 2020b). | In a bid to scale up production quickly, the company is focusing on stock availability rather than consumer demand with staple stock keeping units (SKUs) being preferred rather than those SKUs which demand labor intensity in order to optimize limited available manpower. |

Compilation by authors from PI industries limited. (2020). Press Release. Retrieved from https://www.piindustries.com/Media/Documents/Press Release_Sept_2020.pdf.; Avanti Feeds Limited. (2020). Q2FY21 result presentation November 2020, (103). Retrieved from https://www.avantifeeds.com/QuarterlyResults/AFL_Investor_concall_intimation_30-09-2020.pdf; Rashtriya Chemicals and Fertilizers Limited. (2020). Disclosure of Covid-19 pandemic impact on the Company's operations, (July), 2020–2022. Retrieved from https://www.bseindia.com/xml-data/corpfiling/AttachHis/d2910a5a-1393-4b3a-b0e4-bdce48e10921.pdf; The Economic Times. (2020a). Coronavirus outbreak cuts down demand for buffalo meat by half. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/coronavirus-outbreak-cuts-down-demand-for-buffalo-meat-by-half/articleshow/74504051.cms; The Economic Times. (2020b). Lockdown: Britannia utilising 65% of its capacity, focus on optimising limited manpower. Retrieved from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/cons-products/food/lockdown-britannia-utilising-65-of-its-capacity-focus-on-optimising-limited-manpower/articleshow/75176980.cms?from=mdr; Singh, A. (2020). Covid-19 rumours, fake news slaughter poultry industry; Rs. 22,500 crore lost; 5 crore jobs at stake. Retrieved from https://smefutures.com/covid-19-rumours-fake-news-slaughter-poultry-industry-rs-22500-crore-lost-5-crore-jobs-at-stake/; OECD. (2020). Food supply chains and COVID-19: Impacts and policy lessons. Retrieved from https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=134_134305-ybqvdf0kg9&title=Food-Supply-Chains-and-COVID-19-Impacts-and-policy-lessons; Reuters. (2020a). Nestle shrugs off COVID-19 impact thanks to pet food and health nutrition. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/nestle-results-idUSKBN2760KS; Reuters. (2020b). Thai rice exporters cut 2020 forecast to 6.5 million T, lowest in 20 years. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-rice/thai-rice-exporters-cut-2020-forecast-to-6-5-million-t-lowest-in-20-years-idUSKCN24N0BD.

Table 23.2.

Implications of COVID-19 for stakeholders along the food supply chain in Thailand.

| Food chain | Organizations | Positive impact | Negative impacts | Remedial measures taken | Challenges/comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food producer and exporter |

Oishi Group Public Company Limited The company has two segments, food and beverage business that focus on three areas:

|

Profit declined 40.8% in Q3/2019–2020. Consumption declined by 70%, with limited online delivery. |

Developed a contactless food ordering system (QR order) introduced at Oishi Grand, Oishi Buffet, Oishi Eaterium, Shabushi and is intended to expand to all 269 branches. Started online booking through app to avoid interaction/contact during visit. Launched two new apps, O-Navi (search restaurants in Oi group) to provide convenience and ShabushiHotto game, to redeem awards or receive discounts during dining. |

||

| Food producer |

Kaset Thai International Sugar Corporation Public Company Limited (KTIS) Produces sugar as a major product along with bioproducts, which are used by-products from sugar production as raw materials, such as paper pulp from bagasse, ethanol from molasses, and electrical energy from biomass. |

The operating cost of the company decreased by 29.7% as the net profit decreased 32.4%. Various business lines were affected by the pandemic (Matichon, 2020). | In order to fight the COVID-19, KTIS decided to produce alcohol/sanitizers to be distributed by 7-Eleven in Thailand. | Certain projects within the organization were delayed due to lockdown impacting the delivery of machinery from Europe and other countries in Asia. Apart from COVID, the early drought in 2020 impacted the sugarcane production in the country. |

|

| Food producer and supplier | Minor Food, The Operator of Pizza, Sizzlers, and Bonchon in Thailand. | Reported growth in their food delivery sales proportion of total business from 15% in the first quarter of 2019 to 30% for the same period in 2020. | Many restaurants shifted their focus to delivery and takeaway, which have become the key sales drivers. It is estimated that the food delivery business in Thailand could grow by 31% with a total value of more than US $60 million during the partial lockdown. (USDA, 2020) |

||

| Retailers | Central Food Retail (Tops Supermarket, Central Food Hall, Tops Daily, and Family Mart). | Generated 4% increase in sales revenue of about US $710 million. Makro, a cash and carry retailer, also reported a 9% growth rate for its first quarter from consumers stockpiling essential food items. |

7-Eleven reported a drop in their average sales by 4% for the first quarter of 2020 | Some retailers are offering chat-and-shop services (placing orders by calling)

|

Declining international tourists have severely impacted the retail and food service markets with limited growth. |

Compilation by authors Matichon. (2020). KTIS, p. 15608. Retrieved from https://sitwebsites.blob.core.windows.net/ktissugar-news/20201204-ktis-matiachon-midday01.pdf; USDA. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the Thai food retail and food service sector.

As the pandemic continues to unfold, various impacts on agricultural stakeholders in India clearly indicate examples of how they have coped with the occurrence of the pandemic and have worked on smoothening the food supply chain (Table 23.1). The pandemic has impacted various food industries in terms of reduction in capacity utilization, decrease in prices due to less demand, decline of their shares in food sector index, etc. Most of them have adopted the policy of work from home for their employees. There were some disruptions as Indian rice exports were halted for 3 weeks but later resumed (OECD, 2020). These disruptions occurred because of the policies adopted to control the pandemic but soon reduced as unnecessary restrictions were removed.

Despite the challenges faced by COVID-19, Thailand has received investment worth 5.84 billion baht for food processing and manufacturing projects in the first half of 2020 according to the Thailand Board of Investment (BOI) which indicates investors' confidence in the food sector. Thailand's agricultural and agro-industrial export grew by 2.5%, with 83% increase for frozen and processed fruits and vegetables (BOI, 2020). The social distancing policies implemented by the government forced most retailers to develop their omnichannel retailing methods to address the customers' needs through digital applications, social media, and free delivery services. Although food delivery operators like Food panda and Grab Food have experienced growth during the period, food companies and restaurants were seen extending their direct delivery services to avoid the commission charged by other delivery aggregators.

6. Relevant digital technologies and tools

Online platforms have benefitted many traders and retailers during pandemic. In the first quarter of 2020, Thailand fruit exports declined by 10%. To address this concern, Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives (MOAC) collaborated with 1300 agricultural cooperatives to promote sale of fruits through online platform such as http://www.coopshopth.com/ providing promotions and discounts for domestic consumption. TALAD APP has also been used for access to more customers, increasing incomes, access to workers, and mechanics on fields in another provinces.

Digital payment has been accelerated in many countries in the times of COVID-19; JAM Trinity is an excellent example of digital payment infrastructure in India which enabled direct cash transfer to small holder farmers contributing to food security. Late March 2020, as the lockdown started in India, the government distributed $5 billion cash benefits to its citizens mostly affected and needing assistance through the digital payment platform. Saving nearly $23 billion, 98% of this by eliminating erroneous beneficiaries. A robust direct benefit transfer (DBT) of INR 28,256 crore was done through the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojna (PMGKY) (Srivastava, 2020).

Big data was used by many food operators in South Korea using algorithms to recommend products to customers based on their lifestyle, age, and consumer behavior. Korean SMARTKIOSK company sold food kits through their kiosk service called “FreshStore” (Chemlinked, 2020). Big data has been utilized by FAO Data Labs that developed a set of tools for impact analysis, daily food prices, tweet search, news search, and daily news digest. Apart from impact analysis all other tools are standalone products. Daily food prices are being collected from Numbeo for 14 food products through crowdsourcing and percentage price change is compiled post February 14, 2020. This tool indicates that food prices have increased 4.2% and 9.9% since February 14, 2020, in Thailand and India, respectively. Yet, many agrarian economies have to improve on the collection and dissemination of data for better managing the risks in the agricultural sector.

Digital advisory applications such as e-choupal has been very beneficial for managing the procurement process during COVID-19 in India. Ideally the application provides information regarding procurement, market demand, and prices for informed decision-making in the market. During the crisis, the network infrastructure was used to procure directly from farm locations and introduced supply chain interventions such as multipoint rake movement and coastal container movements to make sure of uninterrupted supply of produce throughout the country (WBCSD, 2020).

Tools and technologies used during the pandemic have had influential roles in different ways along the value chain. For instance, technologies such as bioinformatics and crop genetics are more applicable to the input companies; precision agriculture, apps providing weather information, and crop prices and crop insurance are more applicable for the farmers, and traceability was seen as more applicable to the traders, food companies, and the retailers (Fig. 23.4 ).

Figure 23.4.

Tools and technologies used across agricultural value chain.

Source: Authors.

As more and more technologies are becoming complex, starting from informational level to customized transactional level, it has created further challenges for the farmers at ground level to understand and implement. In case of food safety and quality control of perishable goods such as fruits, vegetables, and fisheries, technology is again used at different levels for packaging, temperature and humidity check during transport, quality control by government at point of entry during imports, and compliance and specific protocols at the retailer level.

7. Conclusion and way forward

In Thailand, apart from the challenges like reduced incomes and increased debts faced by farming households, COVID-19 also created opportunities for the youngsters to be innovative in creating value in the agricultural sector and improve its contribution to Thai economy. Food system value chains still lacks efficient systems to frequently monitor the food security challenges and map and optimize supply chains for efficient risk management. Policy of the government to go for digital solution approach needs an integrated infrastructure including bank account and mobile banking system. Risk models available with the private sector are not effective and reliable enough to facilitate local solutions.

In India, the central government and RBI announced several fiscal and monetary policies with broader economic reforms. In addition, several state governments announced fiscal stimulus measures such as Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana with a financial package of 1.7 lakh crores; Atma-nirbhar package with three components: (i) monetary actions, (ii) fiscal actions, and (iii) economic reforms. Although considering the widespread impact and demand, the package falls short and may need to be enhanced. The fiscal initiatives only address the financing constraints on the supply side, that too inadequately. India's budget provision for managing COVID was 1.3% of GDP as compared to the United States (with budget provision of 10.7% of GDP), Germany (20.95%), Malaysia (16.17%), Spain (15.29%), the United Kingdom (15.27%), and Japan (10.0%). Much more investments are needed to enhance and protect farmers, agricultural laborers, workers in the supply chains, ensuring smooth operation of postharvest activities, marketing of products, cold storage, and transportation for sustainability of agricultural businesses.

Agricultural supply chain was affected both in India and Thailand. Despite various technologies discussed, COVID-19 provides a great opportunity for better adoption of technology and digitization to enhance the existing agricultural systems. Integration of market intelligence and better coordination between departments and ministries can reduce supply chain risks. Proper estimation of demand and enhancing the food processing industry can help in reducing postproduction losses. Public–private partnerships that develop infrastructures and logistics for exports would benefit both India and Thailand in the long run. Providing incentives to companies for research and development will further enhance the resilience of agricultural value chain at national and local levels.

References

- ABC News . 2020. Deforestation of Amazon rainforest accelerates amid COVID-19 pandemic.https://abcnews.go.com/International/deforestation-amazon-rainforest-accelerates-amid-covid-19-pandemic/story?id=70526188 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Aday S., Aday M.S. Vols. 1–14. 2020. (Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ADB-ILO . 2020. Tackling the COVID-19 youth employment crisis in Asia and the Pacific.https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/626046/covid-19-youth-employment-crisis-asia-pacific.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Agroberichten Buitenland . 2020. Update on COVID-19 impact in Thailand.https://www.agroberichtenbuitenland.nl/actueel/nieuws/2020/04/28/update-on-covid-19-impact-in-thailand Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Avanti Feeds Limited . 2020. Q2FY21 result presentation November 2020, (103)https://www.avantifeeds.com/QuarterlyResults/AFL_Investor_concall_intimation_30-09-2020.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Azim Premji University . 2020. COVID-19 livelihoods survey compilation of findings.https://cse.azimpremjiuniversity.edu.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Compilation-of-findings-APU-COVID-19-Livelihoods-Survey_Final.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52267943.

- Bharat Rasayan Limited . 2020. 31st annual report 2019–2020.https://www.bharatgroup.co.in/bharat-rasayan/images/157iuf_Annual_Report_2019_20.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- BOI . 2020. The increasing investments in Thailand's food sector reflects the confidence in Thailand despite COVID-19 outbreak: BOI.https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-increasing-investments-in-thailands-food-sector-reflects-the-confidence-in-thailand-despite-covid-19-outbreak-boi-301099357.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Chemlinked . Vol. 19. 2020. https://www.tisi.go.th/data/regulate/trading_partners/pdf_korea/Impact_of_COVID19_Th.pdf (Impact of COVID-19 on the food industry of the Republic of South Korea). Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- DownToEarth . 2021. COVID-19 has hit India's urban poor more than those in villages: Report.https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/health/covid-19-has-hit-india-s-urban-poor-more-than-those-in-villages-report-76823 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . 2020. Responding to the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on food value chains through efficient logistics, (April)http://www.fao.org/3/ca8466en/CA8466EN.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . 2020. The impact of COVID-19 on fisheries and aquaculture food systems Possible responses.http://www.fao.org/3/cb2537en/CB2537EN.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- FAO The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Sustainability in Action. 2020 http://www.fao.org/3/ca9229en/ca9229en.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- FFTC-AP . 2020. Towards the new normal lifestyle of food consumption in Thailand.https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/2615 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- FICCI . 2020. Decoding agriculture in India amid COVID-19 crisis: Agriculture in India, (June)https://ficci.in/spdocument/23267/FICCI-GT-Report-on-Agriculture.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Food Navigator Asia . 2020. Thailand's COVID-19 ‘war’: Local food production centre of focus as government guarantees supplies.https://www.foodnavigator-asia.com/Article/2020/04/06/Thailand-s-COVID-19-war-Local-food-production-centre-of-focus-as-government-guarantees-supplies Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- IMF . Vol. 6. 2019. (IMF primary commodity price index). [Google Scholar]

- IMF . 2020. World economic outlook, chapter 1: Global prospects and policies. October 2020, (October) [Google Scholar]

- Matichon . 2020. KTIS; p. 15608.https://sitwebsites.blob.core.windows.net/ktissugar-news/20201204-ktis-matiachon-midday01.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company . 2020. Survey: Food retail in Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic.https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/survey-food-retail-in-thailand-during-the-covid-19-pandemic# Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- OECD . 2020. Food supply chains and COVID-19: Impacts and policy lessons.https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=134_134305-ybqvdf0kg9&title=Food-Supply-Chains-and-COVID-19-Impacts-and-policy-lessons Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- PI industries limited. Press Release; 2020. https://www.piindustries.com/Media/Documents/Press Release_Sept_2020.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Rashtriya Chemicals and Fertilizers Limited . 2020. Disclosure of Covid-19 pandemic impact on the Company's operations, (July), 2020–2022.https://www.bseindia.com/xml-data/corpfiling/AttachHis/d2910a5a-1393-4b3a-b0e4-bdce48e10921.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters . 2020. Nestle shrugs off COVID-19 impact thanks to pet food and health nutrition.https://www.reuters.com/article/nestle-results-idUSKBN2760KS Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Reuters . 2020. Thai rice exporters cut 2020 forecast to 6.5 million T, lowest in 20 years.https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-rice/thai-rice-exporters-cut-2020-forecast-to-6-5-million-t-lowest-in-20-years-idUSKCN24N0BD Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. 2020. Covid-19 rumours, fake news slaughter poultry industry; Rs. 22,500 crore lost; 5 crore jobs at stake.https://smefutures.com/covid-19-rumours-fake-news-slaughter-poultry-industry-rs-22500-crore-lost-5-crore-jobs-at-stake/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava S. 2020. Digital solutions for small holders, FAO-ITU digital solutions forum, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- The Economic Times . 2020. Coronavirus outbreak cuts down demand for buffalo meat by half.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/foreign-trade/coronavirus-outbreak-cuts-down-demand-for-buffalo-meat-by-half/articleshow/74504051.cms Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- The Economic Times . 2020. Lockdown: Britannia utilising 65% of its capacity, focus on optimising limited manpower.https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/cons-products/food/lockdown-britannia-utilising-65-of-its-capacity-focus-on-optimising-limited-manpower/articleshow/75176980.cms?from=mdr Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- The Hindu . 2020. Indian economy contracts by 7.5% in Q2.https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/indian-economy-contracts-by-75-in-q2/article33193753.ece Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- The Hindu . 2020. Lockdown halts harvesting season in Odisha's forests.https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/lockdown-halts-harvesting-season-in-forests/article31253235.ece Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- The Indian Express . 2018. Only 23% of rural income from farming, reveals NABARD 2016–17 survey.https://indianexpress.com/article/india/farming-agriculture-income-farm-distress-nabard-survey-nsso-5313772/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- The Nation . 2020. Thai unemployment at nearly 10 percent due to Covid-19.https://www.nationthailand.com/news/30389095 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . 2020. Thai agricultural sector: From problems to solutions.https://thailand.un.org/en/103307-thai-agricultural-sector-problems-solutions Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . 2020. The challenge of reducing food loss and waste during COVID-19.https://www.un.org/en/observances/end-food-waste-day Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- USDA . 2020. The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the Thai food retail and food service sector. [Google Scholar]

- WBCSD . 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on smallholder farmers–insights from India.https://www.wbcsd.org/Overview/News-Insights/WBCSD-insights/Impact-of-COVID-19-on-smallholder-farmers-in-India Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard.https://covid19.who.int/table Accessed on 4th September 2020. [Google Scholar]