Abstract

Antibody therapy is effective for treating infectious diseases. Due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the rise of drug-resistant bacteria, rapid development of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to treat infectious diseases is urgently needed. Using a therapeutic human mAb with the lowest immunogenicity is recommended, because chimera and humanized mAbs are occasionally immunogenic. In order to directly obtain naïve human mAbs, there are three methods: phage display, B cell receptor (BCR) cDNA sequencing of a single cell, and antibody-encoding gene and amino acid sequencing of immortalized cells using memory B cells, which are isolated from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy, vaccinated, infected, or recovered individuals. After screening against the antigen and performing neutralization assays, a human neutralizing mAb is constructed from the antibody-encoding DNA sequences of these memory B cells. This review describes examples of obtaining human neutralizing mAbs against various infectious diseases using these methods. However, a few of these mAbs have been approved for therapy. Therefore, antigen characterization and evaluation of neutralization activity in vitro and in vivo are indispensable for the development of therapeutic mAbs. These results will accelerate the development of antibody drug as therapeutic agents.

Keywords: Antibody therapy, Antibody therapeutic agent, Human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, Memory B cells, Infectious diseases, Viral infection, Bacterial infection

Abbreviations: coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19; monoclonal antibody, mAb; B cell receptor, BCR; dengue virus, DENV; antibody-dependent enhancement, ADE; constant regions of a antibody, CH and CL; complementarity determining region, CDR; severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SARS-CoV-2; peripheral blood mononuclear cells, PBMCs; Ebola virus, EBOV; hepatitis C virus, HCV; single-chain fragmented variable region, scFv; fragmented antigen binding region, Fab; Epstein Bar virus, EBV; heavy chain variable region, VH; light chain variable region, VL; reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, RT-PCR; enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, ELISA; immunoglobulin G, IgG; botulinum neurotoxin, BTX; diphtheria toxin, DT; human immunodeficiency virus, HIV; hepatitis B virus, HBV; Zika virus, ZIKV; Toll-like receptor, TLR; lymphoblast cell line, LCL; spike glycoprotein, S; N-terminal domain, NTD; receptor-binding domain, RBD; angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, ACE2; hemagglutinin, HA; neuraminidase, NA; Ebola virus disease, EVD; Bundibugyo ebolavirus, BDBV; Sudan ebolavirus, SUDV; Tai Forest ebolavirus, TAFV; Reston ebolavirus, RESTV; glycoprotein, GP; Direct acting antivirals, DAA; C-terminal receptor binding domain of the heavy chain, Hc; N-terminal translocation domain of the heavy chain, Hn; light chain, Lc; catalytic, C; transmembrane, T; receptor binding, R

1. Introduction

Antibodies were first discovered as antitoxins against tetanus and diphtheria, and it is a well-known fact that antibodies can control infectious diseases (Lu, Suscovich, Fortune, & Alter, 2018; Salazar, Zhang, Fu, & An, 2017). However, the development of therapeutic antibody agents to treat infectious diseases lags far behind that of those to treat cancer and autoimmune diseases (Castelli, McGonigle, & Hornby, 2019; Lu et al., 2018). Antibiotics are less expensive and easier to produce than the reagents for immunotherapies. Consequently, antibiotics have been prioritized to treat bacterial infectious diseases (Pelfrene, Mura, Cavaleiro Sanches, & Cavaleri, 2019; Saylor, Dadachova, & Casadevall, 2009). For viral infectious diseases, it is often impossible to formulate a strategy to develop antibody drugs unless the mechanism of infection for a virus and a host cell has been clarified (Salazar et al., 2017). Viruses invade host cells to parasitize and replicate, making it difficult for the host immune system to recognize it as a foreign enemy. Moreover, in the case of dengue virus (DENV) infection, symptoms are sometimes exacerbated by vaccination due to antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) (Dejnirattisai et al., 2010). Suboptimal antibodies bind to the virus, resulting in enhancement of its entry into host cells (Iwasaki & Yang, 2020). In order to use antibodies for therapy, it is essential to identify the epitope and to elucidate the mechanism by which the antibody affects the course of an infectious disease. Thus, research and development of antibody drugs require substantial cost and time (Saylor et al., 2009). In recent years, human mAb therapeutics have been attracting attention again because of the COVID-19 pandemic and rise of antimicrobial resistant bacteria (Jahanshahlu & Rezaei, 2020; Kaplon, Muralidharan, Schneider, & Reichert, 2020). In addition, it is much safer to administer a human mAb as therapy against infectious diseases than to administer attenuated or inactivated vaccine or immunoglobulin preparations (Marston, Paules, & Fauci, 2018). Moreover, the development of human neutralizing mAbs against infectious diseases has improved with technological advances with human immunoglobulin transgenic mice, single cell B cell receptor (BCR) DNA sequencing, and phage display (Salazar et al., 2017). Many successful cases have been reported in the past decade (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Human neutralizing mAbs against various infectious diseases.

| Miccrobe | Clone info (name) | KD (nM) | Epitope | Method | Neutralization activity | Origin | Reference info | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus | SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV | S309 | < 1.0 × 10−3 | RBD | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro | An individual infected with SARS-CoV in 2003 | Dora Pinto et al., 2020, Nature | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | C121 | RBD | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of Spike protein-specific B cell | in vitro | 149 COVID-19-convalescent individuals | Davide. F. Robbiani et al., 2020, Nature, and Christopher O. Barnes et al., 2020, Nature | |||

| C135 | |||||||||

| C144 | |||||||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | BD-368-2 | 0.82 | RBD | High-throughput scRNA/VDJ-seq of antigen-binding B cells | in vitro and in vivo (hACE2 transgenic mice) | 12 COVID-19 convalescent individuals from Beijing Youan Hospital | Yunlong Cao et al., 2020, Cell | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 311mab-31B5 | RBD | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of RBD-specific B cell | in vitro | Recovered COVID-19 individuals | Xiangyu Chen et al., 2020, CMI | |||

| 311mab-32D4 | |||||||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | Approximal 40 clones including REGN10933 and REGN10987 | RBD | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of RBD-specific B cell from VelocImmune mouse and human donors | in vitro | Individuals 3–4 weeks post laboratory-confirmed PCR positive test for SARS-CoV-2 and symptomatic COVID-19 infection. | Johanna Hansen et al., 2020, Science | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | CR3022 | 6.3 | RBD | Phage display | in vitro | A convalescent SARS individual from Singapore | Jiandong Huo et al., 2020, Cell Host & Microbe, and Kaewta Rattanapist et al., 2020, Sci Rep | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 | CV30 | 3.6 | RBD | Single cell BCR-seq of Spike protein-specific B cell | in vitro | One of the first individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the state of Wahington at 21 days after the onset of clinical disease | Emilie Seydoux et al., 2020 Immunity, and Nicholas K. Hurlburt et al., 2020, Nature Comm | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 | P2B-2F6 | 5.14 | RBD | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of Spike protein-specific B cell | in vitro | 8 individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2 | Bin Ju et al., 2020, Nature | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 | S2X259 | RBD | Hybridoma (Spike protein-specific B cell and mesenchymal stromal cells) | in vitro and in vivo (Syrian hamster model) | An individual who had recovered from COVID-19 | M. Alejandra Tortorici et al., 2021, Nature | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 7 clones | RBD | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of Spike protein-specific B cell | in vitro | An individual infected with SARS-CoV in 2003 | Anna Z. Wec. et al., 2020, Science | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | COV2–2196 | RBD | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of Spike protein-specific B cell | in vitro and in vivo (anti-IFNAR1-treated, AdV-hACE2-transduced mice) | 2 convalescing individuals who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China | Seth J. Zost et al., 2020, Zost et al., 2020, Nature | |||

| SARS-CoV-2 | COV2–2676 | NTD | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of Spike protein-specific B cell | in vitro and in vivo (hACE2 transgenic mice) | 2 convalescing individuals who had been infected with SARS-CoV2 in Wuhan, China | Naveenchandra Suryadevara et al., 2021, Cell | |||

| COV2–2489 | |||||||||

| SARS-CoV-2 | P5A-3C8 | 1.3 | RBD (K417/R/A/E/N/T) | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of Spike protein-specific B cell | in vitro and in vivo (Syrian hamster model) | 8 individuals infected with SARS-CoV2 | Qi Zhang et al., 2021, Nature Comm | ||

| SARS-CoV-2 | 7 clones | RBD | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of Spike protein-specific B cell and these B cells immortalized | in vitro | 4 individuals in North America with recent laboratory-confirmed symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections | Seth J. Zost, Gilchuk, Case, et al., 2020, Zost, Gilchuk, Chen, et al., 2020, Nature medicine | |||

| H1N1 influenza virus | 1F1 | 5.4 | HA | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (BALB/c mice model) | Survivors of 1918 H1N1 influenza virus pandemic | Xiaocong Yu, et al., 2008, Nature | ||

| 1 l20 | 0.048 | ||||||||

| 2B12 | 6.2 | ||||||||

| 2D1 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| 4D20 | 0.14 | ||||||||

| H5N1 and H1N1 influenza viruses | CR6261 | 3.8 (Fab) | H1 HA | Phage display | in vitro and in vivo (BALB/c mice model) | Volunteers recently vaccinated with the seasonal influenza vaccine | Mark Throsby et al., 2008, PLoS ONE | ||

| 4.1(Fab) | H5 HA | ||||||||

| Influenza A and B viruses | CR9114 | 1.3–4.8 | B HA | Phage display | in vitro and in vivo (Mouse model) | Volunteers recently vaccinated with the seasonal influenza vaccine | Cyrille Drefus, et al., 2012, Science | ||

| 0.9–2.2 | A HA | ||||||||

| H7N9 influenza virus | NA-80 | 0.17 | NA (N9) | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (BALB/c mice model) | H7N9 survivors | Iuliia M. Gilchuk et al., 2019, Cell Host & Microbe | ||

| NA-22 | 0.81 | ||||||||

| H1N1 and H3N2 influenza viruses | MEDI8852 | HA of all 16 subtypes | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (Mouse model) | Volunteers recently vaccinated with the seasonal influenza vaccine | Nicole L. Kallewaard et al., 2016, Cell | |||

| H1N1 and H1N5 influenza viruses | 70-1F02 | 0.00749 | H1N1 HA | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of HA-specific plasmablasts | in vitro and in vivo (BALB/c mice model) | 24 healthy adults immunized with the subunit pH1N1 2009 vaccine | Gui-Mei Li et al., 2012, PNAS, and Raffael Nachbagauer et al., 2018, JV | ||

| 0.0104 | H1N5 HA | ||||||||

| 9-3A01 | 0.179 | H1N1 HA | |||||||

| 0.718 | H1N5 HA | ||||||||

| H1 influenza virus | KPF1 | 0.178 | HA | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of HA-specific plasmablasts | in vitro and in vivo (C57BL/6 mice model) | A healthy subject prior to seven days and one month after receiving the 2014–2015 seasonal inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine (A/California/07/2009 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus, A/Texas/50/2012 (H3N2)-like virus, B/ Massachusetts/2/2012-like virus, B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus) as standard-of-care at the University of Rochester Medical Center | Aitor Nogales et al., 2018, Sci Rep | ||

| H7N9 infulenza virus | H7.5 | <0.1(Fab) | HA (head) | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro | Donors who participated in a vaccination trial with monovalent, inactivated influenza (H7N9), A/Shanghai/02/2013 vaccine candidate (DMID13–0033) | Hannah L. Turner et al., 2019, PLOS Biology | ||

| H7N9 infulenza virus | 5 clones | HA | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (BALB/c mice model) | Donors who participated in a multicenter trial conducted by the NIH Vaccine Treatment and Evaluation Unit (DMID13–0033) | Natalie J. Thornburg et al., 2016, JCI | |||

| H3N2 infulenza virus | C585 | < 1.00–4.01 × 10−3 | HA | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing of plasmablasts | in vitro | A healthy, 56-year-old male vaccinated in the 2013/2014 season with TIV composed of A/California/7/2009 (H1N1), A/Texas/50/2012 (H3N2), and B/Massachusetts/2/2012 (Yamagata lineage) | Yu Qiu et al., 2020, JV | ||

| Infulenza H3N2 variant virus | H3v-47 | < 1.0 × 10−3 | HA (H3N2v) | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (DBA/2 J mice model) | Donors vaccinated with an experimental H3N2v vaccine containing the A/Minnesota/11/ 2010 strain | Sandhya Bangaru et al., 2018, Nature comm | ||

| Infulenza H3N2 variant virus | 6 clones | HA | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (DBA/2 J mice model) | Healthy adult donors received 2 doses of subvirion H3N2v vaccine (15 μg of HA/dose) 21 days apart in an open–label trial |

Sandhya Bangaru et al., 2016, JCI insight. | |||

| Group1 and Group 2 Infulenza A viruses | Fl6 | HA of all 16 subtypes | Single cell antibody-encoding gene sequencing of plasma cells | in vitro and in vivo (BALB/c mice and ferret models) | Healthy donors seven days after i.m. vaccination with seasonal influenza vaccine according to manufacturer instructions |

Davide Corti et al., 2011, Science | |||

| EBOV | mAb114 | GP | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (rhesus macaques model) | Two survivors of the 1995 EVD outbreak in Kikwit | Davide Corti et al., 2016, Science | |||

| EBOV | EBOV-526 | GP | Human hybridoma | in vitro and in vivo (STAT1 KO mice, guinea pigs and ferrets models) | Two survivors of the 2014 EVD outbreak in the DRC and one survivor of the West African 2013–2016 EVD epidemic | Pavlo Gilchuk et al., 2018, Immunity | |||

| EBOV-515 | |||||||||

| EBOV, BDBV and SUDV | EBOV-548 | The base region of GP | Human hybridoma | in vitro and in vivo (BALB/c mice and rhesus macaques models) | Two human survivors of the 2014 EVD outbreak in the DRC and one survivor of the West African 2013–2016 EVD epidemic | Pavlo Gilchuk et al., 2020, Immunity | |||

| EBOV-520 | The gyycan cap of GP | ||||||||

| EBOV and BDBV | BDBV223 | GP2 stalk | Human hybridoma | in vitro and in vivo (BALB/c mice model) | A human survivor of the 2007 BDBV outbreak in Uganda | Andrew I.Flyak, er al., 2016, Cell, Andrew I. Flayk, et al., 2018, Nature microbe, FlyakLiam B. King, et al., 2019, Nature comm | |||

| EBOV | Several clones | GP | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of GP-specific B cell | in vitro and in vivo (BALB/c mice model) | Human survivors of the 2014 EBOV Zaire outbreak. |

Zachary A. Bornholdt et al., 2016, Science | |||

| EBOV and BDBV | Several clones | The fusion loop region of GP | Yeast display | in vitro and in vivo (mouse and ferret models) | Human survivors of the 2014 EBOV Zaire outbreak. |

Anna Z. Wec. et al., 2017, Cell | |||

| HCV | 2A5 | GT1b E2 region (conformation-dependent) | Human hybridoma | in vitro and in vivo (Human liver-chimeric mice model) | An individual chronically infected with HCV | Isabelle Desombere et al., 2017, Antiviral Res | |||

| HCV | AR4A | 2.9 ± 1.8 | outside the CD81-binding site on the E1E2 complex | Phage display | in vitro | A 35-year-old female individual with Sjögren's syndrome and chronic HCV (GT1a) infection | Erick Giang et al., 2012, PNAS, and Rodrigo Velazquez-Moctezuma, et al., 2018, JID | ||

| HCV | AR3A | 1.3/1.7 | E2 (HCVpp GT1a/2a/4/5) | Phage display | in vitro and in vivo (Human liver-chimeric mice model) | A 35-year-old female individual with Sjögren's syndrome and chronic HCV (GT1a) infection | Mansun Law et al., 2008, Nature medicine | ||

| AR3B | 2.0/2.3 | ||||||||

| HBV | 3 clones | HBsAg | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of HBsAg specific B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro | A vaccinated healthy donor and a individual convalescing from acute HBV infection | Antonella Cerio, et al., 2015, PLoS ONE | |||

| ZIKV | ZIKV-117 | E protein | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (IFNAR-blocking C57BL/6 mice model) | Healthy individuals who had previously been infected with ZIKV in diverse geographic locations. | Gopal Sapparapu et al., 2016, Nature, S. Saif Hsaan, et al., 2017, Nature comm, and Jesse H. Erasmus et al., 2020 Methods & Clinical Development | |||

| ZIKV | 2F-8 | E protein (DIII) | Phage display | in vitro and in vivo (Ifnar−/− mice model) | Two ZIKV-infected individuals at Seoul National University Hospital | Sang Il Kim et al., 2021, BBRC | |||

| ZIKV | ZIKV-195 | E protein | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (IFNAR-blocking C57BL/6 mice model) | Healthy individuals who had previously been infected with ZIKV in diverse geographic locations. | Feng Long et al., 2019, PNAS | |||

| ZIKV | ZKA64 | E (DI/II) | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (A129 mice model) | Four ZIKV- infected individuals from the current epidemic, of which two were DENV-naïve and two had serological records of DENV infection | Karin Stettler et al., 2016, Science | |||

| ZIKV and DENV | MZ4 | 2.7/2.6 | E protein (DI/III linker region) (ZIKV/DENV2) | Single cell BCR DNA sequencing of ZIKV E protein- and DENV E protein-specific B cells | in vitro and in vivo (ZIKV challenge: BALB/c mice model, DENV-2 challenge: Ifnar−/− mice model) | A flavivirus-experienced individual enrolled in the ZPIV phase 1 vaccine clinical trial (NCT02937233) conducted at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center | Vincent Dussupt et al., 2020, Nature medicine | ||

| DENV | m366.6 | 0.27–1.9 | E protein (DIII) | Phage display | in vitro and in vivo (A129 mice model) | Individual who might have been infected during foreigntravel. | Dan Hu et al., 2019, PLOS Pathogen | ||

| Parasite | Malaria | CIS43 | 42 | PfCSP | Single cell antibody-endocing gene sequencing of PfCSP-specific plasmablasts | in vitro and in vivo (C57BL/6 mice model) | A malaria-naive individual who received the PfSPZ vaccine | Neville K Kisalu et al., 2018, Nature medicine and Lawrence T. Wang et al., 2020, Immunity | |

| Bacteria | Toxin | Clostridium tetani | 8A7 | TeNT (Hc) | Antibody-encoding gene sequencing and cloning of Memroy B cells immortalized by EBV | in vitro and in vivo (Mouse model) | A healthy individual belonging to a presumed population that has been vaccinated against tetanus | Takeharu Minamitani et al., 2021, Sci Rep | |

| 17F7 | TeNT (Hc) | ||||||||

| 8D8 | TeNT (Hn) | ||||||||

| 16E8 | TeNT (Lc + Hn + Hc) | ||||||||

| Clostridium botulinum | Three clones | 0.24–14.33 (scFv) | BTX Lc | Yeast display | in vitro | A healthy individual immunized with BONT/A-E Toxoid | Yongfeng Fan et al., 2015, toxins | ||

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | Several clones | DT | Phage display | In vitro | Three individuals received a regular booster immunization with an adsorbed diphtheria and tetanus vaccine | Esther Veronika Wenzel et al., 2020, Sci Rep | |||

| Bacterial components | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Cam-003 | 144 | Exopolysaccharide Psl | Phage display | in vitro and in vivo (Mouse model) | Healthy individuals and patients convalescing from P. aeruginosa infections | Antonio DiGiandomenico et al., 2012, JEM | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 514G3 | 0.0467 | SpA | Phage display | in vitro and in vivo | Healthy individuals | Avanish K. Varshney et al., 2018, PLOS one | ||

ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; AdV-hACE2, replication-defective adenoviruses encoding human ACE2; BCR, B cell receptor; BDBV, Bundibugyo ebolavirus; BTX, botulinum neurotoxin; SUDV, Sudan ebolavirus; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019; DENV, Dengue virus; DRC, Democratic Republic of the Congo; DT, Diphtheria toxin; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; EBOV, Ebola virus; EVD, Ebola virus disease; Fab, Fab, fragmented antigen binding region; GP, glycoprotein; GT, genotype; HA, hemagglutinin; HBsAg, hepatitis B virus antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus, Hc, heavy chain C-terminal receptor binding domain; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HCVpp, pseudotype virus particles HCV; Hn, heavy chain N-terminal translocation domain, IFNAR1, interferon Alpha and Beta receptor subunit 1; IFNR, interferon receptor; i.m., intramuscular injection; KD, dissociation constant; Lc, light chain; NA, neuraminidase; NTD, N-terminal domain; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PfSPZ, Plasmodium falciparum sporozoite; SARS-CoV, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; SpA, S. aureus wall moiety Protein A; TeNT, tetanus toxin; TIV, trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine; RBD, receptor binding domain; ZIKV, Zika virus; ZPIV, Z001 Zika purified inactivated virus (Bangaru et al., 2016; Bangaru et al., 2018; Barnes et al., 2020; Bornholdt et al., 2016; Cao et al., 2020; Cerino, Bremer, Glebe, & Mondelli, 2015; Chen et al., 2020; Corti et al., 2011; Corti et al., 2016; Desombere et al., 2017; DiGiandomenico et al., 2012; Dreyfus et al., 2012; Dussupt et al., 2020; Erasmus et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2015; Flyak et al., 2016; Flyak et al., 2018; Giang et al., 2012; Gilchuk et al., 2018; Gilchuk et al., 2019; Hansen et al., 2020; Hasan et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2019; Huo et al., 2020; Hurlburt et al., 2020; Ju et al., 2020; Kallewaard et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2021; Kisalu et al., 2018; Law et al., 2008; Li et al., 2012; Long et al., 2019; Minamitani et al., 2021; Nachbagauer et al., 2018; Nogales et al., 2018; Pinto et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2020; Rattanapisit et al., 2020; Robbiani et al., 2020; Sapparapu et al., 2016; Seydoux et al., 2020; Stettler et al., 2016; Suryadevara et al., 2021; Thornburg et al., 2016; Throsby et al., 2008; Tortorici et al., 2021; Turner et al., 2019; Varshney et al., 2018; Velázquez-Moctezuma et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020; Wec et al., 2017; Wec et al., 2020; Wenzel et al., 2020; Yu, Tsibane, et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2021; Zost, Gilchuk, Case, et al., 2020; Zost, Gilchuk, Chen, et al., 2020).

2. Antibody therapeutic agents

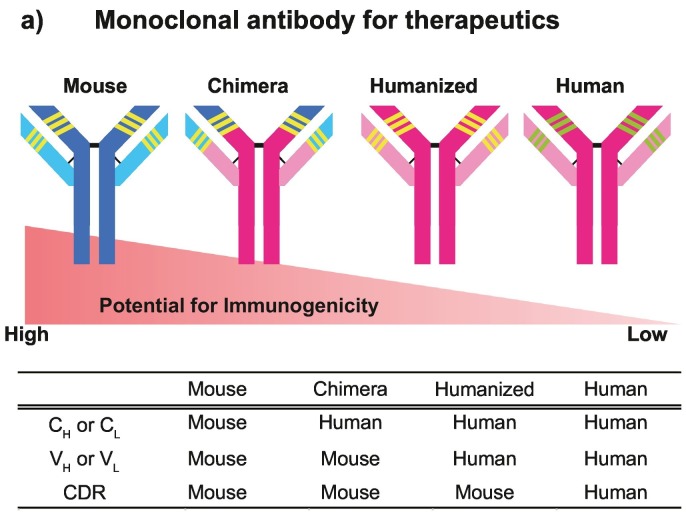

Research and development of antibody therapeutic agents began with the hybridoma technique, which uses cell fusion between murine lymphocytes and myeloma cells. Firstly, mouse mAbs against various diseases pathogens including infectious diseases were made as therapeutic agents (Elgundi, Reslan, Cruz, Sifniotis, & Kayser, 2017). However, when a mouse mAb is administered to a patient, it is recognized as foreign by the human immune system, resulting in production of antibodies against the mouse mAb (Goulet & Atkins, 2020; Lu et al., 2020). In addition, adverse effects such as excessive immune response are induced occasionally. It is difficult to use mouse mAbs for therapy in humans because of their high immunogenicity. To suppress immunogenicity, a chimeric antibody was made by replacing the constant regions (CH and CL) of a mouse antibody with those of a human antibody (Fig. 1 ) (Lu et al., 2020). In addition, humanized antibodies are constructed by inserting only the complementarity determining regions (CDR) of a mouse antibody into the human antibody frame (Fig. 1) (Castelli et al., 2019; Marston et al., 2018). However, chimeric and humanized antibodies are occasionally immunogenic (Lu et al., 2020). Until 2022, 11 therapeutic antibodies for infectious diseases have been approved in EU and US (Ecker, Jones, & Levine, 2015; Kaplon et al., 2020; Kaplon and Reichert, 2018, Kaplon and Reichert, 2019, Kaplon and Reichert, 2021; Reichert, 2016, Reichert, 2017). Eight of them are human antibodies (Raxibacumab, Bezlotoxumab, maftivimab + odesivimab-ebgn, Ansuvimab, Regdanvimab, Sotrovimab, Tixagevimab + Cilgavimab, Casirivimab + imdevimab). Two are humanized antibodies (Palivizumab, Ibalizumab). One is a chimeric antibody (Obiltoxaximab). The recent reports regarding immunogenicity and approved therapeutic agents suggest an urgent need for further development of human mAbs. Indeed, 161 manuscripts about neutralizing mAbs against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have been published in 2020 and 2021. Moreover, the number of publications about neutralizing mAbs against various diseases in 2021 (4411 publications) is approximately twice more than that in 2018 (2366 publications) and 2019 (2409 publications).

Fig. 1.

Potential for immunogenicity in therapeutic mAbs.

In a chimeric antibody, VH and VL (which contains the CDR) are the sequences derived from a mouse antibody; approximately 65% of the sequence is from a human antibody. On the other hand, a humanized antibody includes only the CDR of a mouse antibody. Over 90% of the antibody sequence is from human. CDR, complementarity determining region; CH and CL, constant regions of the heavy and light chains; VH and VL, variable regions of the heavy and light chains.

3. Development of human neutralizing mAbs against infectious diseases

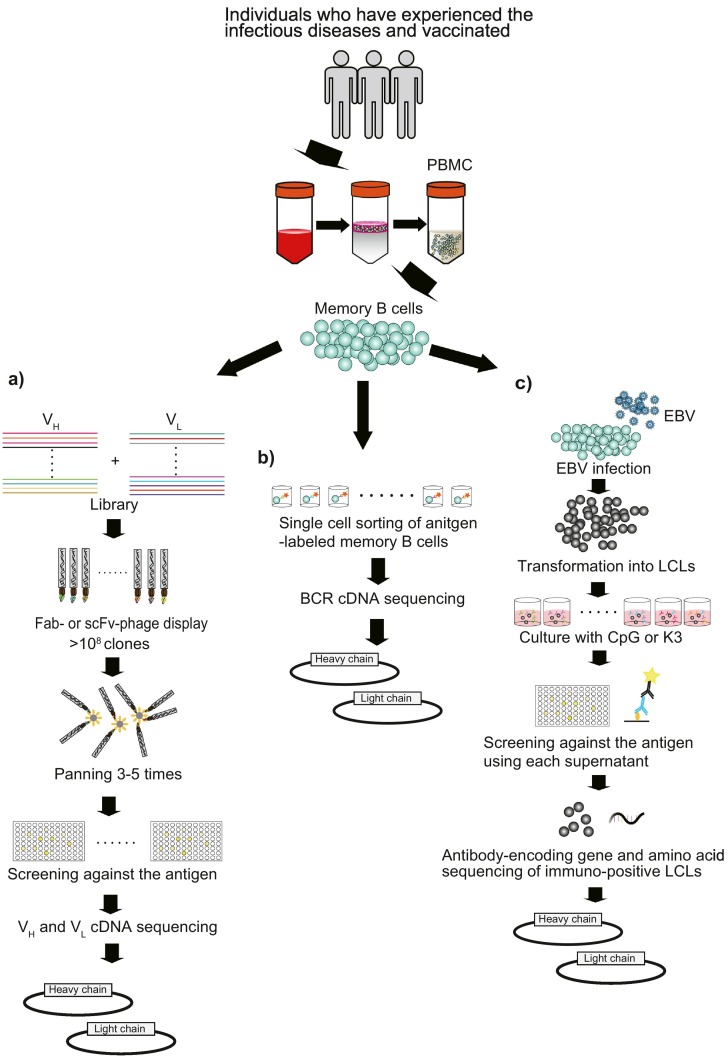

Human mAb development consists of two methods, those with or without memory B cells isolated from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Lu et al., 2020; Salazar et al., 2017). One strategy for identifying mAbs without memory B cells involves the use of human immunoglobulin transgenic mice (Elgundi et al., 2017). This method can rapidly obtain human mAbs when the conventional hybridoma technique is used (Lu et al., 2020). The greatest advantage of this method is that antibodies can be constructed against highly lethal pathogens such as Ebola virus (EBOV), SARS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome-CoV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), influenza virus, and Staphylococcus aureus alpha toxin (Broering et al., 2009; Coughlin et al., 2007; Mendoza et al., 2018; Morin et al., 2012; Pascal et al., 2018; Tkaczyk et al., 2012). The disadvantage is that antibodies acquired using transgenic mice are not naïve human antibodies. Hence, the safety issue needs to be considered. On the other hand, the methods with memory B cells use phage display with a single-chain fragmented variable region (scFv) or a fragmented antigen binding region (Fab), BCR DNA sequencing of a single antigen-labeled memory B cell, memory B cells immortalized by Epstein Barr virus (EBV) infection, or human B cells hybridoma (Fig. 2 ) (Salazar et al., 2017; Yu, McGraw, House, & Crowe, 2008). These methods can directly result in naïve human mAb-encoding gene sequences. Since recombinant naïve human mAbs are expected to have the lowest immunogenicity and be the safest in humans, we will focus on the development of human mAbs for therapies using the methods with memory B cells and introduce neutralizing mAbs against various infectious diseases in the following sections.

Fig. 2.

Schematic for obtaining mAbs using memory B cells.

Memory B cells are isolated from PBMCs of healthy, immunized, or infected individuals. a) Phage display. A VH and VL library is acquired from antigen-specific memory B cells. After panning 3–5 times, phage clones are screened with an ELISA. Finally, the VH and VL sequences of immunopositive phage clones are identified with RT-PCR. b) BCR DNA sequencing of single antigen-labeled memory B cells is performed. Sequence information for full antibody-encoding genes is directly obtained from memory B cells without culturing them. c) IgG-encoding gene and amino acid sequencing is performed, and memory B cells immortalized by EBV are cloned. Most memory B cells are infected with EBV and polyclonally transformed into LCLs. The LCLs are seeded into 96-well plates and cultured with TLR9 ligand CpG or TLR9 agonist K3. IgG-encoding gene and amino acid sequences are identified from RNA and culture supernatants of immunopositive LCLs. Ultimately, the IgG sequence is subcloned into a mammalian expression vector. BCR, B cell receptor; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; ELISA, enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay; Fab, fragmented antigen binding region; LCL, lymphoblast cell line; mAb, monoclonal antibody; Peripheral blood mononuclear cell, PBMC; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, RT-PCR; scFv, single-chain fragmented variable region; VH and VL, variable regions of the heavy and light chains.

3.1. Phage display

By employing bacteriophages, phage display is the most widely used method in the development of human neutralizing mAbs (Frenzel et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2020; Uchański et al., 2019). The genes of heavy chain (VH) and light chain (VL) variable regions are amplified using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from the RNA of antigen-specific memory B cells, which are collected from those who have infected, recovered or vaccinated. scFv and Fab genes are cloned into a phagemid to generate a scFv or Fab library that contains >108 VH and VL combinations (DiGiandomenico et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2021; Parray et al., 2020; Throsby et al., 2008). This library is introduced into the phage and expressed on the surface. After 3–5 rounds of panning for a target antigen, phage clones are screened using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The DNA sequences of immunopositive phage clones are analyzed to construct human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Fig. 2a). In this application, predefined antigens are needed to pan the library. It is not suitable for identifying novel neutralizing epitopes (Salazar et al., 2017). This method has generated neutralizing mAbs against SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, EBOV, HCV, influenza virus, DENV, botulinum neurotoxin (BTX), diphtheria toxin (DT), Pseudomonas aeruginosa exopolysaccharide Psl, and Staphylococcus aureus wall moiety protein A (Table 1) (Saylor et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2021).

3.2. BCR cDNA sequencing of a single labeled-antigen memory B cell

Memory B cells are isolated from PBMCs of infected, recovered, or vaccinated donors to react with a biotinylated or fluorescent antigen. Antigen-labeled memory B cells are sorted by flow cytometry. Subsequently, BCR cDNA sequencing of single cells is performed directly without culturing the B cells to gain sequence information for antibody-encoding genes (Fig. 2b). Similar to phage display, well-characterized antigens are required to isolate the antigen-labeled memory B cells. This method is also not suitable for identifying novel neutralizing epitopes (Salazar et al., 2017; Walker & Burton, 2018). This method has generated recombinant neutralizing mAbs from infected or immunized donors against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), SARS-CoV-2, influenza virus, EBOV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and Zika virus (ZIKV) (Table 1) (Walker et al., 2009; Walker et al., 2011).

3.3. Obtaining antibody-encoding gene and amino acid sequencing, and cloning of memory B cells immortalized by EBV or human hybridoma cell line

IgM+ B cells are depleted from PBMCs derived from naturally infected or immunized donors. The remaining cells are infected with EBV, followed by culturing with stimuli including Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 ligand, CpG, or TLR9 agonist K3, as well as some other supplements. Next, they are polyclonally transformed into a lymphoblast cell line (LCL) that produce an antibody (Ali et al., 2020; Minamitani et al., 2021). LCL supernatants are screened by ELISA against various antigens. On the other hand, human B cells are isolated from PBMC of infected or recovered donors. These cells expanded on irradiated NIH 3 T3 cells in medium supplemented with CpG and the others. Next, supernatants were assessed by ELISA for reactivity against various antigens. The immunopositive B cells were fused with HMMA2.5 myeloma cells and culture (Yu, McGraw, et al., 2008). Hybridoma cell lines producing the antibody were cloned biologically by single-cell fluorescence-activated cell sorting (Gilchuk et al., 2018). RT-PCR is then performed using RNA from immunopositive LCL clones or human hybridoma cell lines from which we can obtain the sequence information of IgG-encoding genes and amino acids (Fig. 2c) (Boutz et al., 2014; Sato et al., 2012; Walker & Burton, 2018). With this method, it is unnecessary to sort antigen-specific memory B cells by the target antigen, which makes it suitable for identifying novel neutralizing epitopes (Salazar et al., 2017; Walker & Burton, 2018). This method was used to generate neutralizing mAbs against SARS-CoV, influenza virus, EBOV, HCV, ZIKV, HIV, Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein, and tetanus toxin (TeNT) (Table 1) (Gorny et al., 2005).

4. Development of human neutralizing mAbs against viral infection

For the development of antibody therapeutics, viruses are classified by whether they have an envelope. Antibodies can recognize viral glycoproteins of the envelope on the surface of the virion as target antigens. A glycoprotein recognizes and interacts with a host cell receptor via a binding site on the glycoprotein (Ali et al., 2020; Walker & Burton, 2018). Subsequently, the viral envelope fuses with the host cellular membrane, allowing the capsid and viral genome to enter the host. Enveloped viruses include SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, influenza virus, HCV, EBOV, ZIKV, CHIKV, and HIV. Neutralizing mAbs against enveloped viruses are created to block the binding of the glycoprotein to the host cell receptor in most cases (Ali et al., 2020). In contrast, non-enveloped viruses including adenovirus, norovirus, and rhinovirus enter the host via lysis of the membrane or making pore-like structures in the membrane without interaction between a viral glycoprotein and a host receptor. The development of antibodies against non-enveloped virus has not progressed much (Ali et al., 2020).

4.1. Human neutralizing mAbs against SARS-CoV-2

SARS-CoV-2 is a new coronavirus that causes COVID-19, an infectious disease that emerged in 2019. The development of therapeutic agents for COVID-19 has been progressing with the unprecedented speed. Nimatrelvir and monupiravir were approved for an emergency use authorization as the first oral antivirals by Food and Drug Administration. However, these drugs show effectiveness for the patients only when they are administered orally within 3–5 days after symptom onset. Therefore, there are no validated therapeutics against SARS-CoV-2 infection when the symptom onset over 5 days and the viral replication becomes dominant in the body (Cao et al., 2020; Parums, 2022). Accordingly, there is an urgent need to develop antibody drugs against COVID-19. The SARS-CoV-2 envelope has a spike (S) glycoprotein with two subunits, namely S1 and S2. S1 includes the N-terminal domain (NTD) and the receptor-binding domain (RBD). S2 promotes fusion of the viral and cellular membranes. S1 binds to the host angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor via the RBD, resulting in viral entry (Fig. 3a) (Jahanshahlu & Rezaei, 2020). In 2020 and 2021, it has been reported that many neutralizing mAbs against SARS-CoV-2 were made using methods involving memory B cells from infected or recovered donors. The target of all these antibodies is the binding of S protein to ACE2 via the RBD of S1 (Table 1) (Huang et al., 2020). Most of these antibodies can recognize the RBD of S1 and inhibit the interaction between the S protein and ACE2, while a few binds to the NTD. Although these antibodies can suppress viral entry, the risk of ADE is a concern (Iwasaki & Yang, 2020). Indeed, Liu et al. have reported that some neutralizing mAbs that target S1 NTD enhance the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2. The interaction between the mAb and NTD leads to a structural open state of the RBD, which facilitates the binding of S protein to ACE2, resulting in ADE (Liu et al., 2021). This report illustrates that it is essential to identify an appropriate epitope and evaluate neutralization activity in vivo and in vitro when developing mAbs for therapies.

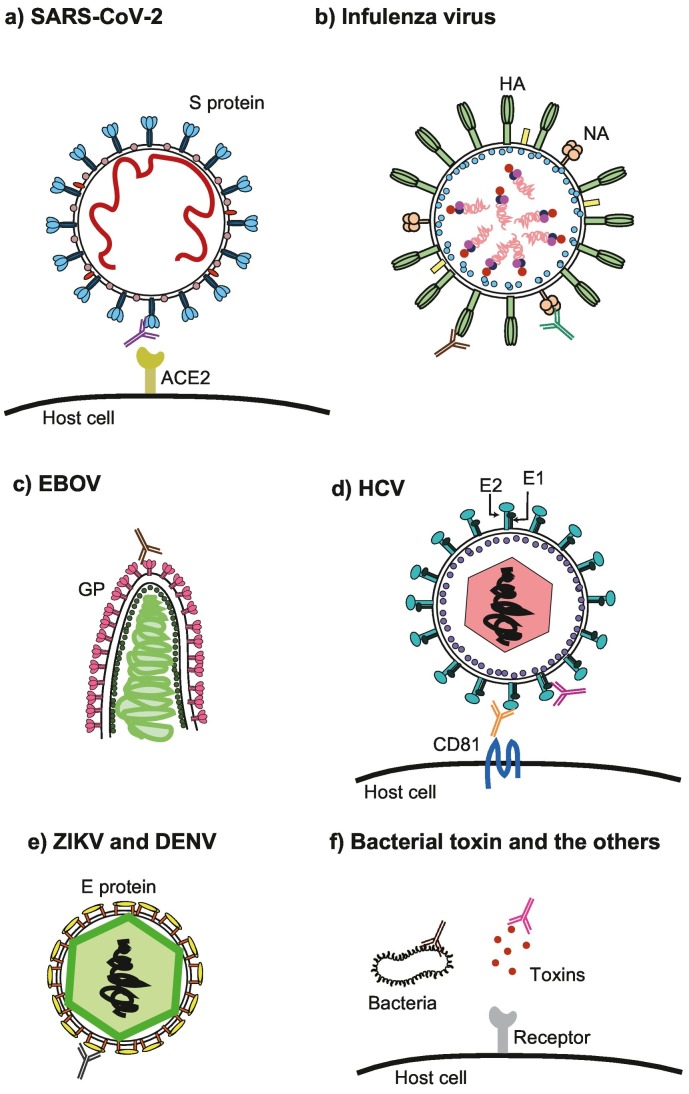

Fig. 3.

Targets for human neutralizing mAb against infectious diseases.

a) SARS-CoV-2 infection. The S protein binds to ACE2 via the S1 RBD. The main target is S1. b) Influenza virus infection. The targets are HA and NA. HA interacts with host sialic receptors to facilitate host cell entry. c) EBOV infection. The target is the glycoprotein. d) HCV infection. The target is the E1-E2 complex, which will interfere with the interaction between the E2 and CD81. e) ZIKV and DENV infection. The target is the E protein containing DI, DII, and DIII. DIII is a better target for obtaining cross-reactive mAbs than DII. f) Bacterial toxins and other targets. The toxin is the main target for mAb therapeutics. LPS is also a target for suppressing bacterial infection. ACE2, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; DENV, Dengue virus; GP, glycoprotein; EBOV, Ebola virus; HA, hemagglutinin; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; mAb, monoclonal antibody; NA, neuraminidase; RBD, receptor-binding domain; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; ZIKV, zika virus.

In 2004, the neutralizing mAb S309 against SARS-CoV was obtained from PBMCs of an individual who infected with SARS-CoV in 2003 (Traggiai et al., 2004). S309 has high affinity against both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 S protein since the SARS-CoV-2 S protein shares 77.5% homology with the SARS-CoV S protein (Pinto et al., 2020). In addition, the mAb S2X259 was isolated from an individual who had recovered from COVID-19. S2X259 has neutralizing activity against coronaviruses broadly, including SARS-CoV-2 (Tortorici et al., 2021). These reports suggest that existing neutralizing mAbs might overcome unknown mutant strains of SARS-CoV-2.

Owing to vaccination with S protein–encoding RNA or DNA vaccines worldwide (Rogliani, Chetta, Cazzola, & Calzetta, 2021), it is expected that development of neutralizing mAbs against SARS-CoV-2 will be further promoted by using memory B cells from a vaccinated individual.

4.2. Human neutralizing mAbs against influenzas virus

Influenza viruses are classified into three types: A, B, and C. In particular, influenza A and B have two glycoproteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). These influenza viruses are responsible for frequent seasonal epidemics. Genotypically, influenza A has 16 HA subtypes and 9 NA subtypes. After the HA head binds to the sialic acid receptor, the HA stem fuses the viral and host cell membranes, resulting in entry via endocytosis (Fig. 3b) (Turner et al., 2019). The main target for neutralizing mAbs against influenza is HA (Table 1). In a rare case, Gilchuk et al. have succeeded in generating neutralizing mAbs against NA. The mAbs NA-80 and NA-22 interact with NA, blocking the nascent virions releasing from the infected cells (Gilchuk et al., 2019). HA-specific and NA-specific mAbs have different molecular mechanisms for inhibiting viral infection. Therefore, an antibody cocktail including these mAbs is expected to have much higher neutralization activity than a single antibody.

Interestingly, Yu et al. reported that the development of neutralizing mAbs against H1N1 influenza virus from memory B cells of an elderly survivor from the influenza pandemic in 1918 was traceable (Table 1) (Yu et al., 2008). This suggests that neutralizing mAbs against infectious diseases that younger generations have not yet experienced might be obtained from a healthy individual who was infected in the past.

Variations in HA and NA antigenicity often occur due to antigenic drift within the same subtype, which causes seasonal influenza epidemics every year. Therefore, cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies that can recognize HAs of various highly pathogenic influenza A subtypes are needed. Table 1 includes several antibodies acquired from volunteers recently vaccinated with the seasonal influenza vaccine. The mAb CR9114 has neutralization activity against both influenza A and B in vivo, while CR6261 can decrease mortality from infection against the H1N1 and H5N1 influenza A subtypes in a mouse model (Table 1) (Dreyfus et al., 2012; Throsby et al., 2008). In addition, the mAbs 70-1F02 and 9-3A01 can inhibit infection with two subtypes of H1N1/H1N5 influenza A (Li et al., 2012; Nachbagauer et al., 2018). Moreover, MEDI8852 and Fl6 can recognize HA from all 16 subtypes in vitro and suppress various subtype infections in vivo (Corti et al., 2011; Kallewaard et al., 2016). These reports demonstrate that cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies against various subtypes of influenza A are rapidly and efficiently acquired from healthy donors vaccinated with the seasonal influenza vaccine.

4.3. Human neutralizing mAbs against EBOV

EBOV causes severe disease in humans; fatality rates range from 25% to 90% depending on the virus, location, and other factors (Wec et al., 2017). The 2013–2016 Ebola virus disease (EVD) epidemic occurred in West Africa, resulting in 28,646 infections and 11,323 deaths (Gilchuk et al., 2018). There are five distinct species of EBOV including Zaire ebolavirus commonly known as EBOV, Bundibugyo ebolavirus (BDBV), Sudan ebolavirus (SUDV), Tai Forest ebolavirus (TAFV), and Reston ebolavirus (RESTV). EBOV, BDBV, and SUDV cause lethal disease in humans (Flyak et al., 2016; Gilchuk et al., 2018).

EBOV has a single glycoprotein that forms a trimer. The glycoprotein (GP), which consists of two subunits, GP1 and GP2, binds to the host cell receptor via GP1 and induces fusion between the viral and host cell membranes through GP2, resulting in endosomal entry into the host cell (Fig. 3c) (Wec et al., 2017). The glycoprotein is the main target for neutralizing antibodies (Table 1). The ZMapp cocktail, a mixture of therapeutic mAbs, is composed of three EBOV glycoprotein-specific chimeric antibodies; 2G4 and 4G7 recognize the base region of glycoprotein and c13C6 targets the glycan cap. However, the ZMapp cocktail can only bind to the glycoprotein of EBOV, not BDBV or SUDV (Flyak et al., 2016; Wec et al., 2017). In order to acquire cross-reactive neutralizing mAbs against EBOV, BDBV, and SUDV, hundreds of glycoprotein-specific mAbs were isolated from survivors of the 2013–2016 EVD epidemic. The mAb BDBV223 can neutralize both EBOV and BDBV in vitro and in vivo (Table 1) (Flyak et al., 2016). On the other hand, several broad neutralizing mAbs have been obtained from human survivors of the 2014 EVD outbreak (Bornholdt et al., 2016). ADI-15742 and ADI-15878 interact with the glycoprotein fusion loop region and has high neutralization activity against EBOV, BDBV, and SUDV in vivo (Wec et al., 2017). Moreover, the cocktail including the E520 mAb which bounds to the base region of GP and E548 mAb which targets a glycan cap l has higher neutralization activity against EBOV, BDBV, and SUDV in vitro than a single mAb and completely protects non-human primates challenged with EBOV (Gilchuk et al., 2020). These reports prove that using a method involving memory B cells is suitable for isolating cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies against different viral species.

4.4. Human neutralizing mAbs against HCV

HCV is associated with liver failure and cirrhosis (Zhu, Qian, Zhao, & Qi, 2014). HCV contains a 9.6-kb positive-stranded RNA genome with one open reading frame encoding a single polyprotein (Mesalam et al., 2018). The polyprotein is cleaved by viral and host cellular proteases into 10 proteins including the envelope glycoprotein E1 and E2 proteins. E1 and E2 form a heterodimer on the virion and bind to CD81, claudin-1, scavenger receptor class B type I, and other targets to promote entry into host cells (Fig. 3d) (Mesalam et al., 2018). E2 is the major target for neutralizing antibodies (Table 1) (Kinchen, Cox, & Bailey, 2018).

HCV has seven genotypes. Direct acting antivirals (DAAs), which target multiple steps in the HCV replication life cycle, are highly effective against various HCV genotypes, including genotype 1, which is resistant to interferon therapy (Ecker et al., 2015). However, many DAAs induce drug-drug interactions, making it difficult for some patients to continue with therapy. Cross-reactive neutralizing mAbs have been isolated from memory B cells of an individual with chronic HCV infection (Table 1). Some specific mAbs, namely AR3A and AR3B, can neutralize genotype 1a/2a/4/5 pseudotype HCV particles in vitro (Law et al., 2008). AR4A can recognize the exterior of the CD81-binding site on the E1-E2 complex and suppress entry of cell culture–produced HCV genotype 1a/1b/2a/3a/4a/5a/6a into host cells in vitro (Giang et al., 2012; Velázquez-Moctezuma, Galli, Law, Bukh, & Prentoe, 2018). These studies suggest that the neutralizing mAbs that recognize less well-known epitopes may contain highly cross-reactive antibodies.

4.5. Human neutralizing mAbs against ZIKV and DENV

ZIKV is an enveloped positive-stranded RNA virus in the Flavivirus genus of the Flaviviridae family. ZIKV is associated with neurological pathology and congenital neurological defects (Dussupt et al., 2020). Other major human pathogens include DENV, West Nile virus, yellow fever virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and tick-borne encephalitis virus (Long et al., 2019). ZIKV's 11 kb genome encodes a single polyprotein that can be cleaved into 10 proteins. The glycoprotein E protein consists of DI, DII, and DIII domains and induces entry into host cells. Thus, the E protein is the main target for neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 3e) (Kim et al., 2021). The DI/II domain-specific mAb ZKA78 obtained from ZIKV-infected individuals inhibits ZIKV infection in vitro and in vivo. The cross-reactivity against the E protein of DENV in vitro was also validated. However, the cause of ADE in patients with DENV infection was also reported (Table 1) (Stettler et al., 2016). On the other hand, the DI/III linker region-specific mAb MZ4 isolated from an individual who experienced DENV infection was enrolled in the Z001 Zika purified inactivated virus phase 1 vaccine clinical trial. MZ4 has neutralization activity against both ZIKV and DENV in vivo and does not induce ADE (Table 1) (Dussupt et al., 2020). Taken together, it is absolutely necessary to confirm whether cross-reactive neutralizing mAbs have in vivo neutralization activity against each virus.

5. Development of neutralizing mAbs against bacterial infections

Bacteria have more complicated structures than viruses. Therefore, fewer therapeutic neutralizing mAbs against bacterial infection have been developed. Depending on the type of Bacteria, the major components include DNA, RNA, cytoplasm, cell membranes, and cell walls. Some bacteria have appendages such as flagella, pili, and capsules. Furthermore, gram-negative bacteria have an outer membrane outside of the cell wall (Motley & Fries, 2017).

Toxins including BTX, TeNT, and DT are virulence factors in bacterial infection. Toxins, which are produced extracellularly by bacteria, can bind to the host cell receptor, and subsequently enter the cell, resulting in cell death (Fig. 3f). Many neutralizing antibodies against toxins have been developed to inhibit the interaction between the toxin and its receptor (Motley, Banerjee, & Fries, 2019; Saylor et al., 2009). BTX, which is produced by Clostridium botulinum is the most lethal substance. All of the serotypes of BTXs are composed of two polypeptide chains. The heavy chain contains the C-terminal receptor binding domain (Hc) and the N-terminal translocation domain (Hn), while the light chain (Lc), which has the zinc protease catalytic activity, is responsible for vesicle fusion and acetylcholine vesicle release (Fan et al., 2015). Fan et al. isolated 19 Lc-specific mAbs using phage display method. 11 of them inhibits Lc proteolytic activity in vitro (Fan et al., 2015). Their study indicates that Lc plays an important role as an antigen in obtaining neutralizing antibodies against BTXs. Secreted by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, DT is another bacterial toxin consists of a catalytic (C) domain, transmembrane (T) domain, and receptor binding (R) domain. Wenzel et al. obtained 19 mAbs against DT with neutralization activity in vitro. Of these 19 antibodies, 9 have an epitope in the C domain, 7 in the R domain, and 2 in the T domain (Wenzel et al., 2020). This suggests that the C domain has the highest antigenicity, followed by the R and T domains. On the other hand, TeNT, which is released by Clostridium tetani, causes a fatal disease. TeNT is cleaved by bacterial and host proteases into two chains linked by a single disulfide bridge. As in the case of BTXs, TeNT consinst of Lc, Hc and Hn. Minamitani et al. have isolated several neutralizing mAbs against TeNT from memory B cells of healthy individuals (Minamitani et al., 2021). Hn has the lowest antigenicity, followed by Lc and Hc. The Hn-specific mAb 8D8 has the highest neutralization activity in vivo. This report suggests that the region of an antigen with high antigenicity might not correspond to the epitope with high neutralizing activity recognized by the relevant mAbs.

Developing neutralizing mAbs that target other components of bacteria is very difficult because the relationship between bacteria and host cells is not as simple as the relationship between viral glycoproteins and host cell receptors. Nevertheless, DiGiandomenico et al. have developed a neutralizing mAb, Cam-003, against exopolysaccharide Psl using phage display (DiGiandomenico et al., 2012). Two libraries were prepared from a healthy individual and a patient at 7–10 days after documented P. aeruginosa infection. P. aeruginosa whole cells were used in panning to screen for P. aeruginosa-specific scFvs. To identify Psl-specific scFvs, four strains were employed as antigens for screening: O-antigen deficient, O-antigen and alginate deficient, O-antigen and truncated outer core of lipopolysaccharide, and O-antigen and truncated inner core and Psl-specific scFvs. Psl-specific mAbs have neutralization activity in vitro and in vivo. Neutralizing mAbs as therapy for bacterial infections are still in the development stage. It is expected that mAbs with higher neutralization activity will be obtained after elucidating the mechanism of infection between a bacterium and the host cell.

6. Conclusions and perspectives

Two points in the strategy to develop therapeutic human neutralizing mAbs need to be considered. One is to thoroughly characterize the antigen. It is necessary to clarify which domain yields the mAb with the highest neutralization activity because mAbs acquired via highly antigenic antigens do not always have high neutralization activity. Moreover, obtaining mAbs against various epitopes is also important to enhance neutralization activity. In some cases, neutralization activity can be dramatically improved by making a cocktail containing multiple mAbs with different targets. When developing a cross-reactive neutralizing mAb, it is suitable to use an antigen containing a sequence that is conserved across different species not only in the primary structure but also in the tertiary structure. Another point is to evaluate the neutralization activity in vitro and in vivo. AED must always be considered when developing human mAb therapeutic agents.

Some mAbs in Table 1 have a low frequency of somatic hypermutation (Kallewaard et al., 2016; Wec et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021). This suggests that effective antibodies are produced without repeated sensitization to the antigen in the human body. It might be possible to obtain therapeutic neutralizing mAbs not only from infected or vaccinated individuals but also from healthy individuals. In addition, neutralizing mAbs derived from individuals with prior infection might respond to novel infectious diseases. For these reasons, it is helpful to further promote the development of therapeutic human neutralizing mAbs using method involving memory B cells. Moreover, the use of existing human neutralizing mAbs will lead to lower development costs. These are expected to bring great benefits to the development of human mAb therapeutic agents.

Author contributions

R.O. and Y.T. conceived the work and decided the topic. R.O. described the manuscript, generated the figures and table and found the references. Y.T. supervised the work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development of Japan (AMED) Grants 21fk0108467h0001 (to T.Y.), and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) 21K08503 (to T.Y.) and Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists 19K16641 (to R.O.). We thank Dr M. L. Leong and Dr. B. E. Grewunz for support of proofreading.

Editor: S.J. Enna

References

- Ali M.G., Zhang Z., Gao Q., Pan M., Rowan E.G., Zhang J. Recent advances in therapeutic applications of neutralizing antibodies for virus infections: An overview. Immunologic Research. 2020;68:325–339. doi: 10.1007/s12026-020-09159-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangaru S., Nieusma T., Kose N., Thornburg N.J., Finn J.A., Kaplan B.S., King H.G., Singh V., Lampley R.M., Sapparapu G., et al. Recognition of influenza H3N2 variant virus by human neutralizing antibodies. JCI Insight. 2016;1 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.86673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangaru S., Zhang H., Gilchuk I.M., Voss T.G., Irving R.P., Gilchuk P.…Nieusma T., et al. A multifunctional human monoclonal neutralizing antibody that targets a unique conserved epitope on influenza HA. Nature Communications. 2018;9:2669. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04704-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C.O., Jette C.A., Abernathy M.E., Dam K.A., Esswein S.R., Gristick H.B., Malyutin A.G., Sharaf N.G., Huey-Tubman K.E., Lee Y.E., et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody structures inform therapeutic strategies. Nature. 2020;588:682–687. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2852-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornholdt Z.A., Turner H.L., Murin C.D., Li W., Sok D., Souders C.A., Piper A.E., Goff A., Shamblin J.D., Wollen S.E., et al. Isolation of potent neutralizing antibodies from a survivor of the 2014 Ebola virus outbreak. Science. 2016;351:1078–1083. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutz D.R., Horton A.P., Wine Y., Lavinder J.J., Georgiou G., Marcotte E.M. Proteomic identification of monoclonal antibodies from serum. Analytical Chemistry. 2014;86:4758–4766. doi: 10.1021/ac4037679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broering T.J., Garrity K.A., Boatright N.K., Sloan S.E., Sandor F., Thomas W.D.…Babcock G.J. Identification and characterization of broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies directed against the E2 envelope glycoprotein of hepatitis C virus. Journal of Virology. 2009;83:12473–12482. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01138-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Su B., Guo X., Sun W., Deng Y., Bao L.…Geng C., et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 identified by high-throughput single-cell sequencing of convalescent Patients’ B cells. Cell. 2020;182(73–84) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli M.S., McGonigle P., Hornby P.J. The pharmacology and therapeutic applications of monoclonal antibodies. Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. 2019;7 doi: 10.1002/prp2.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerino A., Bremer C.M., Glebe D., Mondelli M.U. A human monoclonal antibody against hepatitis B surface antigen with potent neutralizing activity. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Li R., Pan Z., Qian C., Yang Y., You R.…Li Z., et al. Human monoclonal antibodies block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2020;17:647–649. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0426-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti D., Misasi J., Mulangu S., Stanley D.A., Kanekiyo M., Wollen S., Ploquin A., Doria-Rose N.A., Staupe R.P., Bailey M., et al. Protective monotherapy against lethal Ebola virus infection by a potently neutralizing antibody. Science. 2016;351:1339–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti D., Voss J., Gamblin S.J., Codoni G., Macagno A., Jarrossay D.…Vanzetta F., et al. A neutralizing antibody selected from plasma cells that binds to group 1 and group 2 influenza a hemagglutinins. Science. 2011;333:850–856. doi: 10.1126/science.1205669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin M., Lou G., Martinez O., Masterman S.K., Olsen O.A., Moksa A.A., Farzan M., Babcook J.S., Prabhakar B.S. Generation and characterization of human monoclonal neutralizing antibodies with distinct binding and sequence features against SARS coronavirus using XenoMouse. Virology. 2007;361:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejnirattisai W., Jumnainsong A., Onsirisakul N., Fitton P., Vasanawathana S., Limpitikul W.…Supasa S., et al. Cross-reacting antibodies enhance dengue virus infection in humans. Science. 2010;328:745–748. doi: 10.1126/science.1185181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desombere I., Mesalam A.A., Urbanowicz R.A., Van Houtte F., Verhoye L., Keck Z.Y.…Baumert T.F., et al. A novel neutralizing human monoclonal antibody broadly abrogates hepatitis C virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Research. 2017;148:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiandomenico A., Warrener P., Hamilton M., Guillard S., Ravn P., Minter R.…Lin J., et al. Identification of broadly protective human antibodies to Pseudomonas aeruginosa exopolysaccharide Psl by phenotypic screening. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2012;209:1273–1287. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus C., Laursen N.S., Kwaks T., Zuijdgeest D., Khayat R., Ekiert D.C., Lee J.H., Metlagel Z., Bujny M.V., Jongeneelen M., et al. Highly conserved protective epitopes on influenza B viruses. Science. 2012;337:1343–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1222908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussupt V., Sankhala R.S., Gromowski G.D., Donofrio G., De La Barrera R.A., Larocca R.A.…Davidson E., et al. Potent Zika and dengue cross-neutralizing antibodies induced by Zika vaccination in a dengue-experienced donor. Nature Medicine. 2020;26:228–235. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0746-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker D.M., Jones S.D., Levine H.L. The therapeutic monoclonal antibody market. mAbs. 2015;7:9–14. doi: 10.4161/19420862.2015.989042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgundi Z., Reslan M., Cruz E., Sifniotis V., Kayser V. The state-of-play and future of antibody therapeutics. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2017;122:2–19. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus J.H., Archer J., Fuerte-Stone J., Khandhar A.P., Voigt E., Granger B.…Durnell L.A., et al. Intramuscular delivery of replicon RNA encoding ZIKV-117 human monoclonal antibody protects against Zika virus infection. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2020;18:402–414. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Dong J., Lou J., Wen W., Conrad F., Geren I.N.…Ho M., et al. Monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the proteolytic activity of botulinum neurotoxin serotype/B. Toxins (Basel) 2015;7:3405–3423. doi: 10.3390/toxins7093405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flyak A.I., Kuzmina N., Murin C.D., Bryan C., Davidson E., Gilchuk P., Gulka C.P., Ilinykh P.A., Shen X., Huang K., et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies from human survivors target a conserved site in the Ebola virus glycoprotein HR2–MPER region. Nature Microbiology. 2018;3:670–677. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0157-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flyak A.I., Shen X., Murin C.D., Turner H.L., David J.A., Fusco M.L.…Kuzmina N., et al. Cross-reactive and potent neutralizing antibody responses in human survivors of natural ebolavirus infection. Cell. 2016;164:392–405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenzel A., Kugler J., Helmsing S., Meier D., Schirrmann T., Hust M., Dubel S. Designing human antibodies by phage display. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy. 2017;44:312–318. doi: 10.1159/000479633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giang E., Dorner M., Prentoe J.C., Dreux M., Evans M.J., Bukh J., Rice C.M., Ploss A., Burton D.R., Law M. Human broadly neutralizing antibodies to the envelope glycoprotein complex of hepatitis C virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:6205–6210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114927109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchuk I.M., Bangaru S., Gilchuk P., Irving R.P., Kose N., Bombardi R.G.…Li S., et al. Influenza H7N9 virus neuraminidase-specific human monoclonal antibodies inhibit viral egress and protect from lethal influenza infection in mice. Cell Host & Microbe. 2019;26(715–728) doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchuk P., Kuzmina N., Ilinykh P.A., Huang K., Gunn B.M., Bryan A.…Fusco M.L., et al. Multifunctional Pan-ebolavirus antibody recognizes a site of broad vulnerability on the ebolavirus glycoprotein. Immunity. 2018;49(363–374) doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchuk P., Murin C.D., Milligan J.C., Cross R.W., Mire C.E., Ilinykh P.A.…Hui S., et al. Analysis of a therapeutic antibody cocktail reveals determinants for cooperative and broad ebolavirus neutralization. Immunity. 2020;52(388–403) doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorny M.K., Stamatatos L., Volsky B., Revesz K., Williams C., Wang X.H.…Zolla-Pazner S. Identification of a new quaternary neutralizing epitope on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virus particles. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:5232–5237. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.5232-5237.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulet D.R., Atkins W.M. Considerations for the Design of Antibody-Based Therapeutics. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2020;109:74–103. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J., Baum A., Pascal K.E., Russo V., Giordano S., Wloga E., Fulton B.O., Yan Y., Koon K., Patel K., et al. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science. 2020;369:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan S.S., Miller A., Sapparapu G., Fernandez E., Klose T., Long F.…Diamond M.S., et al. A human antibody against Zika virus crosslinks the E protein to prevent infection. Nature Communications. 2017;8:14722. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Zhu Z., Li S., Deng Y., Wu Y., Zhang N.…Lei C., et al. A broadly neutralizing germline-like human monoclonal antibody against dengue virus envelope domain III. PLoS Pathogens. 2019;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Sun H., Yu H., Li S., Zheng Q., Xia N. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2: Current understanding, challenge and perspective. Antib Ther. 2020;3:285–299. doi: 10.1093/abt/tbaa028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo J., Zhao Y., Ren J., Zhou D., Duyvesteyn H.M.E., Ginn H.M.…Shah P.N.M., et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by destruction of the Prefusion spike. Cell Host & Microbe. 2020;28(445–454) doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt N.K., Seydoux E., Wan Y.-H., Edara V.V., Stuart A.B., Feng J., Suthar M.S., McGuire A.T., Stamatatos L., Pancera M. Structural basis for potent neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 and role of antibody affinity maturation. Nature Communications. 2020:11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19231-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki A., Yang Y. The potential danger of suboptimal antibody responses in COVID-19. Nature Reviews. Immunology. 2020;20:339–341. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0321-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshahlu L., Rezaei N. Monoclonal antibody as a potential anti-COVID-19. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2020;129 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju B., Zhang Q., Ge J., Wang R., Sun J., Ge X., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou B., Song S., et al. Human neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature. 2020;584:115–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallewaard N.L., Corti D., Collins P.J., Neu U., McAuliffe J.M., Benjamin E.…Walker P.A., et al. Structure and function analysis of an antibody recognizing all influenza a subtypes. Cell. 2016;166:596–608. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplon H., Muralidharan M., Schneider Z., Reichert J.M. Antibodies to watch in 2020. mAbs. 2020;12:1703531. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2019.1703531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplon H., Reichert J.M. Antibodies to watch in 2018. mAbs. 2018;10:183–203. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2018.1415671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplon H., Reichert J.M. Antibodies to watch in 2019. mAbs. 2019;11:219–238. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2018.1556465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplon H., Reichert J.M. Antibodies to watch in 2021. mAbs. 2021;13:1860476. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2020.1860476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.I., Kim S., Shim J.M., Lee H.J., Chang S.Y., Park S.…Kim S., et al. Neutralization of Zika virus by E protein domain III-specific human monoclonal antibody. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2021;545:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinchen V.J., Cox A.L., Bailey J.R. Can broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies Lead to a hepatitis C virus vaccine? Trends in Microbiology. 2018;26:854–864. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisalu N.K., Idris A.H., Weidle C., Flores-Garcia Y., Flynn B.J., Sack B.K.…Francica J.R., et al. A human monoclonal antibody prevents malaria infection by targeting a new site of vulnerability on the parasite. Nature Medicine. 2018;24:408–416. doi: 10.1038/nm.4512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Maruyama T., Lewis J., Giang E., Tarr A.W., Stamataki Z., Gastaminza P., Chisari F.V., Jones I.M., Fox R.I., et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies protect against hepatitis C virus quasispecies challenge. Nature Medicine. 2008;14:25–27. doi: 10.1038/nm1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G.M., Chiu C., Wrammert J., McCausland M., Andrews S.F., Zheng N.Y.…Edupuganti S., et al. Pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine induces a recall response in humans that favors broadly cross-reactive memory B cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:9047–9052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118979109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Soh W.T., Kishikawa J.I., Hirose M., Nakayama E.E., Li S.…Arakawa A., et al. An infectivity-enhancing site on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein targeted by antibodies. Cell. 2021;184(3452–3466) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long F., Doyle M., Fernandez E., Miller A.S., Klose T., Sevvana M.…Kuhn R.J., et al. Structural basis of a potent human monoclonal antibody against Zika virus targeting a quaternary epitope. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2019;116:1591–1596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815432116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L.L., Suscovich T.J., Fortune S.M., Alter G. Beyond binding: Antibody effector functions in infectious diseases. Nature Reviews. Immunology. 2018;18:46–61. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R.M., Hwang Y.C., Liu I.J., Lee C.C., Tsai H.Z., Li H.J., Wu H.C. Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2020;27:1. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0592-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston H.D., Paules C.I., Fauci A.S. Monoclonal antibodies for emerging infectious diseases — Borrowing from history. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378:1469–1472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1802256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza M., Ballesteros A., Qiu Q., Pow Sang L., Shashikumar S., Casares S., Brumeanu T.D. Generation and testing anti-influenza human monoclonal antibodies in a new humanized mouse model (DRAGA: HLA-A2. HLA-DR4. Rag1 KO. IL-2Rgammac KO. NOD) Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2018;14:345–360. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1403703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesalam A.A., Desombere I., Farhoudi A., Van Houtte F., Verhoye L., Ball J., Dubuisson J., Foung S.K.H., Patel A.H., Persson M.A.A., et al. Development and characterization of a human monoclonal antibody targeting the N-terminal region of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E1. Virology. 2018;514:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minamitani T., Kiyose K., Otsubo R., Ito T., Akiba H., Furuta R.A., Inoue T., Tsumoto K., Satake M., Yasui T. Novel neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies against tetanus neurotoxin. Scientific Reports. 2021;11:12134. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91597-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin T.J., Broering T.J., Leav B.A., Blair B.M., Rowley K.J., Boucher E.N.…Olsen D.B., et al. Human monoclonal antibody HCV1 effectively prevents and treats HCV infection in chimpanzees. PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motley M.P., Banerjee K., Fries B.C. Monoclonal antibody-based therapies for bacterial infections. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2019;32:210–216. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motley M.P., Fries B.C. A new take on an old remedy: generating antibodies against multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria in a postantibiotic world. mSphere. 2017:2. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00397-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachbagauer R., Shore D., Yang H., Johnson S.K., Gabbard J.D., Tompkins S.M.…Ahmed R., et al. Broadly reactive human monoclonal antibodies elicited following pandemic H1N1 influenza virus exposure protect mice against highly pathogenic H5N1 challenge. Journal of Virology. 2018;92 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00949-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales A., Piepenbrink M.S., Wang J., Ortega S., Basu M., Fucile C.F.…Keefer M.C., et al. A highly potent and broadly neutralizing H1 influenza-specific human monoclonal antibody. Scientific Reports. 2018;8:4374. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22307-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parray H.A., Chiranjivi A.K., Asthana S., Yadav N., Shrivastava T., Mani S.…Pindari K., et al. Identification of an anti-SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain-directed human monoclonal antibody from a naive semisynthetic library. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2020;295:12814–12821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.AC120.014918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parums D.V. Editorial: Current status of Oral antiviral drug treatments for SARS-CoV-2 infection in non-hospitalized patients. Medical Science Monitor. 2022;28 doi: 10.12659/MSM.935952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal K.E., Dudgeon D., Trefry J.C., Anantpadma M., Sakurai Y., Murin C.D.…Rafique A., et al. Development of clinical-stage human monoclonal antibodies that treat advanced Ebola virus disease in nonhuman Primates. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2018;218:S612–s626. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelfrene E., Mura M., Cavaleiro Sanches A., Cavaleri M. Monoclonal antibodies as anti-infective products: A promising future? Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2019;25:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D., Park Y.J., Beltramello M., Walls A.C., Tortorici M.A., Bianchi S., Jaconi S., Culap K., Zatta F., De Marco A., et al. Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Nature. 2020;583:290–295. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2349-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y., Stegalkina S., Zhang J., Boudanova E., Park A., Zhou Y.…Vogel T.U., et al. Mapping of a novel H3-specific broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibody targeting the hemagglutinin globular head isolated from an elite influenza virus-immunized donor exhibiting serological breadth. Journal of Virology. 2020;94 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01035-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattanapisit K., Shanmugaraj B., Manopwisedjaroen S., Purwono P.B., Siriwattananon K., Khorattanakulchai N.…Smith D.R., et al. Rapid production of SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD) and spike specific monoclonal antibody CR3022 in Nicotiana benthamiana. Scientific Reports. 2020;10:17698. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74904-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert J.M. Antibodies to watch in 2016. mAbs. 2016;8:197–204. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1125583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichert J.M. Antibodies to watch in 2017. mAbs. 2017;9:167–181. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2016.1269580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbiani D.F., Gaebler C., Muecksch F., Lorenzi J.C.C., Wang Z., Cho A., Agudelo M., Barnes C.O., Gazumyan A., Finkin S., et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature. 2020;584:437–442. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogliani P., Chetta A., Cazzola M., Calzetta L. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies: A network Meta-analysis across vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar G., Zhang N., Fu T.M., An Z. Antibody therapies for the prevention and treatment of viral infections. NPJ Vaccines. 2017;2:19. doi: 10.1038/s41541-017-0019-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapparapu G., Fernandez E., Kose N., Bin C., Fox J.M., Bombardi R.G., Zhao H., Nelson C.A., Bryan A.L., Barnes T., et al. Neutralizing human antibodies prevent Zika virus replication and fetal disease in mice. Nature. 2016;540:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature20564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S., Beausoleil S.A., Popova L., Beaudet J.G., Ramenani R.K., Zhang X.…Polakiewicz R.D. Proteomics-directed cloning of circulating antiviral human monoclonal antibodies. Nature Biotechnology. 2012;30:1039–1043. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylor C., Dadachova E., Casadevall A. Monoclonal antibody-based therapies for microbial diseases. Vaccine. 2009;27(Suppl. 6):G38–G46. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydoux E., Homad L.J., MacCamy A.J., Parks K.R., Hurlburt N.K., Jennewein M.F.…Feng J., et al. Analysis of a SARS-CoV-2-infected individual reveals development of potent neutralizing antibodies with limited somatic mutation. Immunity. 2020;53(98–105) doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stettler K., Beltramello M., Espinosa D.A., Graham V., Cassotta A., Bianchi S., Vanzetta F., Minola A., Jaconi S., Mele F., et al. Specificity, cross-reactivity, and function of antibodies elicited by Zika virus infection. Science. 2016;353:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryadevara N., Shrihari S., Gilchuk P., VanBlargan L.A., Binshtein E., Zost S.J.…Chen E.C., et al. Neutralizing and protective human monoclonal antibodies recognizing the N-terminal domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Cell. 2021;184(2316–2331) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornburg N.J., Zhang H., Bangaru S., Sapparapu G., Kose N., Lampley R.M.…Branchizio A., et al. H7N9 influenza virus neutralizing antibodies that possess few somatic mutations. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2016;126:1482–1494. doi: 10.1172/JCI85317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Throsby M., van den Brink E., Jongeneelen M., Poon L.L., Alard P., Cornelissen L., Bakker A., Cox F., van Deventer E., Guan Y., et al. Heterosubtypic neutralizing monoclonal antibodies cross-protective against H5N1 and H1N1 recovered from human IgM+ memory B cells. PLoS One. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkaczyk C., Hua L., Varkey R., Shi Y., Dettinger L., Woods R.…Chowdhury P., et al. Identification of anti-alpha toxin monoclonal antibodies that reduce the severity of Staphylococcus aureus dermonecrosis and exhibit a correlation between affinity and potency. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2012;19:377–385. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05589-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici M.A., Czudnochowski N., Starr T.N., Marzi R., Walls A.C., Zatta F., Bowen J.E., Jaconi S., Di Iulio J., Wang Z., et al. Broad sarbecovirus neutralization by a human monoclonal antibody. Nature. 2021;597:103–108. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traggiai E., Becker S., Subbarao K., Kolesnikova L., Uematsu Y., Gismondo M.R.…Lanzavecchia A. An efficient method to make human monoclonal antibodies from memory B cells: Potent neutralization of SARS coronavirus. Nature Medicine. 2004;10:871–875. doi: 10.1038/nm1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]