Abstract

Given the COVID-19 epidemic, the quantity of hazardous medical wastes has risen unprecedentedly. This study characterized and verified the pyrolysis mechanisms and volatiles products of medical mask belts (MB), mask faces (MF), and infusion tubes (IT) via thermogravimetric, infrared spectroscopy, thermogravimetric-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analyses. Iso-conversional methods were employed to estimate activation energy, while the best-fit artificial neural network was adopted for the multi-objective optimization. MB and MF started their thermal weight losses at 375.8 °C and 414.7 °C, respectively, while IT started to degrade at 227.3 °C. The average activation energies were estimated at 171.77, 232.79, 105.14, and 205.76 kJ/mol for MB, MF, and the first and second IT stages, respectively. Nucleation growth for MF and MB and geometrical contraction for IT best described the pyrolysis behaviors. Their main gaseous products were classified, with a further proposal of their initial cracking mechanisms and secondary reaction pathways.

Keywords: Medical plastic wastes, Pyrolysis, TG-FTIR, Py-GC/MS, Reaction mechanisms

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Prior to the new epidemic of coronavirus (COVID-19), the quantity of medical waste generation (e.g., masks, infusion tubes, protective clothing, medical gloves, and goggles) was estimated at 843,000 tons in 196 large-to-medium-sized cities in China (MEPC, 2020) but has increased by 7.5 times in Wuhan alone since the epidemic (Di Maria et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021). Polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and nylon are their main components. These hazardous medical wastes in unprecedentedly high quantity are also threatening public and environmental health unless their proper management is ensured (Windfeld and Brooks, 2015).

High temperature incineration of medical wastes was shown to produce air pollution, as well as harmful inorganic substances, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), persistent organic pollutants (POPs), and ash containing toxic metals (Al-Salem et al., 2009; Ali and Siddiqui, 2005; Garcia et al., 2007; Ulutan, 1998). Compared to incineration, pyrolysis favors an environmentally friendly and highly efficient process with high value-added products (Chand Malav et al., 2020; Imtenan et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2021) while degrading organic materials by splitting their chemical bonds in an anaerobic environment (Sharifzadeh et al., 2019; Wan Mahari et al., 2021). In terms of pollution control, the highly toxic substances produced by the waste pyrolysis are less than those produced by the waste incineration and can be further reduced by adopting a pretreatment process or co-pyrolysis (Çepelioğullar and Pütün, 2013; Han et al., 2020). Also, pyrolysis intermediates can be used in a variety of applications from premium fuels to fine chemicals (Matsakas et al., 2017). Mohseni-Bandpei et al. (2019) showed that temperature, waste particle size, and residence time were the main drivers of the formation and destruction of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and their components during the pyrolysis of health care wastes. Al-Salem et al. (2017) found that pyrolysis most reduced dioxin, CO, and SO2 emissions when incineration, landfill, gasification, and pyrolysis of plastic wastes were compared.

There have been previous studies on the pyrolysis of medical waste. Hong et al. (2018) pointed out the net profit of pyrolysis to be higher than that of other disposal methods, based on the life cycle assessment of medical wastes. Paraschiv et al. (2015) reported no significant effect of the reactor scale on the distribution of pyrolytic gas products of medical plastic wastes but on the quality of condensable fractions. Ding et al. (2021a) studied the pyrolysis volatiles of syringes and medicine bottles, which are C4-C24 olefins and dienes, C6-C41 alkanes and C8-C41 olefins, respectively. The addition of 10 % PP or PE to the co-pyrolysis of textile dyeing sludge was reported to achieve the best performance with the lowest activation energy (Ding et al., 2021b). Fang et al. (2020) reported that organic matter in medical waste pyrolyzed at 500 °C contained 60 % of hydrocarbons and lipids whose carbon chain length varied between C6-C28, and whose maximum calorific value of 37.56 MJ/kg was close to gasoline. This suggested that the pyrolysis of medical wastes can result in high-quality fuels. To quantify the pyrolysis kinetics of medical wastes, the model-free methods such as Friedman, Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose (KAS), Flynn–Wall–Ozawa (FWO), and distributed activation energy model (DAEM) have been widely used (Ding et al., 2021a; Paraschiv et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2009). To better understand the thermochemical conversions and optimize reactor designs, the model-free methods were also combined with the model-fitting methods such as integral master-plots (Song et al., 2021; Zou et al., 2020).

In related literature, there exists no study about the pyrolysis mechanisms, reaction pathways, and volatiles products of the medical wastes of masks and infusion tubes. Systematically characterizing and understanding their reaction mechanisms and products are essential to the design and optimization of medium-to-large reactors. Given the knowledge gaps in this field, this study aims to thermochemically characterize their pyrolytic drivers, mechanisms, kinetics, thermodynamics, products, and pathways, as well as simultaneously optimize multiple energetic and environmental objectives as a function of the interaction between temperature and feedstock types. The four iso-conversional methods of FWO, KAS, Starink, and Friedman were employed to estimate the pyrolysis kinetics, while the decomposition mechanism was quantified using the model-fitting method of integral master-plots.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample preparation

All the materials used in this experimental study were purchased from a pharmacy. Disposable medical masks with a size of 175 mm × 95 mm (manufactured by Henan Chaoya Medical Equipment Co. Ltd., China) in Fig. 1 were divided into mask belt (MB) and mask face (MF) and cut into pieces of about 2 mg and 0.2 mg, respectively. Hose parts of infusion tubes (IT) (manufactured by Zhenjiang Kangli Medical Equipment Co. Ltd., China) in Fig. 1 were used and ground to below 74 μm using a freezing grinder (Freezer/Mill 6875, SPEX CertiPrep, USA). All the samples were dried naturally under good ventilation for 24 h and then in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h for the further removal of moisture.

Fig. 1.

Disposable medical masks and infusion tubes used in this study.

2.2. Thermogravimetric (TG) analysis

A TG analyzer (NETZSCH STA 409 PC, Germany) was used to measure the mass losses of MB, MF, and IT during the pyrolysis in the range of 30–900 °C at the three heating rates of 10, 20, and 40 °C/min. About 8.0 mg of the samples were loaded in an alumina crucible and heated in the N2 atmosphere, with a carrier gas rate of 70 mL/min (20 mL for protective gas; 50 mL for purged gas). To obtain a blank baseline and eliminate the background value, an empty alumina crucible was heated under the same experimental conditions at each heating rate before the start of the formal experiments. Each test was replicated three times in order to ensure an experimental margin of error of ±2 %.

2.3. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer

A FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet IS50, Thermofisher, USA) was used to detect the surface functional groups of the samples. 1 mg of the IT samples and 150 mg of the KBr were weighed, put together into agate mortars, ground, and fully mixed rotating the agate body. They were put into a die using a tablet press under the pressure of 8 MPa for 60 s after which the tablet was taken out and dried in an oven for 10 min. Since the MB and MF samples cannot be ground, attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessories were used for measurements. Each test was replicated three times in order to ensure the reproducibility.

2.4. TG-FTIR analysis

A TG analyzer (TG209 F1, Netzsch, Germany) and a FTIR spectrometer (IS50, Thermo, USA) were combined to analyze gases generated in the pyrolysis. About 8.0 mg of the samples were heated from 30 to 900 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C/min in the N2 atmosphere, with a carrier gas rate of 50 mL/min. The evolved gases were sent to FTIR through the transfer line whose temperature was maintained at 260 °C against condensation. The FTIR settings were set to the scanning wavenumber range of 4000 to 600 cm−1 at a resolution of 8 cm−1 with four scans per sampling for the data acquisition time of 60 min. Similarly, a blank experiment before the formal experiment was carried out to eliminate the background value.

2.5. Pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) analysis

MB, MF, and IT were heated to 900 °C using a fast pyrolysis device (Frontier PY3030D, Japan). The volatiles products evolved from the pyrolysis were characterized using a GC/MS (Thermo TRACE1310, Thermo ISQLT, USA). Helium was used as the purge gas in the GC at a flow rate of 0.80 mL/min at the front inlet with a split ratio of 100:1. The temperature of the GC oven was kept at 50 °C initially for 1 min, increased to 300 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min, and held at 300 °C for 1 min. A DB-5MS quartz capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) was used in the MS. The MS was performed in an electron ionization (EI) mode with a mass-to-charge ratio of 40– 800 (m/z). The compositions of volatiles were determined using NIST107 library spectrum and published reports.

2.6. Pyrolysis kinetics

Kinetic analysis provides the basis for the energetics of pyrolysis behavior. The conversion degree (α) is defined as follows:

| (1) |

Eq. (1) can be re-arranged as follows (Chen et al., 2021):

| (2) |

where m 0, m t, and m f are original, instantaneous, and final sample masses, respectively; A represents the pre-exponential factor (s−1); β represents the heating rate; E represents activation energy (kJ/mol); R represents the gas constant [8.314 J/(K·mol)]; and T represents absolute temperature (K).

At the original conditions of α = 0 and T = T 0, the following results are obtained by integrating Eq. (2):

| (3) |

In this study, the four iso-conversional methods of FWO, KAS, Starink, and Friedman were employed to estimate the apparent activation energy (E a) (Table 2). Eqs. (4), (5), (6), (7) below were used to estimate the four thermodynamic parameters of ΔH, ΔG, A, and ΔS, respectively:

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

where K B and h are the Boltzmann (1.381 × 10−23 J/K) and Plank (6.626 × 10−34 J·s.) constants, respectively.

Table 2.

Kinetic methods employed in the present study (Cai and Chen, 2009; Vyazovkin, 2001; Yousef et al., 2020).

| Method | Approximation function of P(y) | Specific function |

|---|---|---|

| FWO | P(y) = exp(−1.052y − 5.331) | lnβ = ln (AE/RG(α)) − 5.331 − 1.052(E/RT) |

| KAS | P(y) = [exp(−y)]/y2 | ln(β/T2) = ln (AE/RG(α)) −E/RT |

| Starink | P(y) = [exp(−y)]/y2 | ln(β/T1.92) = ln (AE/RG(α)) − 0.312 − 1.0008(E/RT) |

| Friedman | – | ln(β(dα/dT)) = ln (f (α)A) −E/(RT) |

The integral master-plots method was used to determine the best-fit reaction mechanisms as follows:

| (8) |

where G(α 0.5) is the integral reaction model at α = 0.5 and .

P(u) can be transformed into the following form by the Doyle's approximation:

| (9) |

In order to obtain G(α)/G(α 0.5), the conversion degree (α) was decomposed into different integral forms of the dynamic models listed in Table S1 (Hu et al., 2019). The optimal kinetic model was obtained by comparing the theoretical G(α)/G(α 0.5) and experimental P(u)/P(u 0.5) master-plots. MATLAB was used to perform reverse calculations on the reaction transformations predicted by the model to further verify the credibility of the selected model.

2.7. Multi-objective optimization

Artificial neural networks (ANN) are the non-parametric data-driven models that accurately capture.

non-linear relationships between multiple inputs and outputs even in the face of categorical responses and predictors, outliers, and missing values (Hojjat, 2020). In this study, the best-fit ANN was adopted for the multi-objective optimization owing to its ability to jointly simulate the 14 responses of remaining mass (RM, %), derivative TG (DTG, %/min), and 12 volatiles species as a function of temperature (Temp, °C) and feedstock type (FT with three levels) (n = 76,652). The ANN-based joint optimization was carried out using the composite desirability (D) of 0–1 (ideal situation) (Derringer and Suich, 1980). All the analyses were performed using JMP Pro 16.2.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Physicochemical drivers of pyrolysis

The main components of MB, MF, and IT were PET, PP, and PVC respectively, as was determined by comparing FTIR results with the existing literature (Section 3.7). The ultimate, proximate, and higher heating value (HHV) analyses of MB, MF, and IT are presented in Table 1 . The volatiles contents of MB, MF, and IT were 92.21 %, 96.62 %, and 93.40 %, respectively. MB and IT contained high carbon and oxygen but low hydrogen, while MF contained only carbon and hydrogen that determined its higher heating value (HHV). The high HHV estimates of MF (45.88 MJ/kg), IT (25.04 MJ/kg), and MB (22.79 MJ/kg) indicated the extent to which their thermochemical conversions released energy.

Table 1.

The proximate analyses, ultimate analyses, and higher heating value (HHV) analyses of MB, MF, and IT.

| Samples | MB | MF | IT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximate analysis (wt%) | Moisture | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.22 |

| Volatiles | 92.21 | 96.62 | 93.40 | |

| Ash | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.07 | |

| Fixed carbon | 7.09 | 2.87 | 6.32 | |

| Ultimate analysis (wt%) | C | 62.65 | 85.65 | 51.67 |

| H | 4.78 | 14.43 | 6.81 | |

| O | 31.77 | – | 41.23 | |

| N | 0.1 | ND | ND | |

| HHV (MJ/kg) | 22.79 | 45.88 | 25.04 | |

O (wt%) = 100 % – C – H – N – moisture – ash; Fixed carbon (%) = 100 – moisture – ash – volatiles; ND: Not detected.

3.2. Pyrolysis patterns as a function of feedstock type, heating rate, and temperature

The pyrolysis patterns of MB, MF, and IT are shown in response to the heating rates of 10, 20, and 40 °C/min in Fig. 2 . With the increased heating rate, the TG-DTG curves shifted to the high temperature zone, while the initial (T i), peak (T p), and final (T f) temperatures of the samples gradually rose (Table 3). The peak (−R p) and average (−R v) decomposition rates of the higher heating rate were about twice those of the lower heating rate (Table 3). The comprehensive pyrolysis index (CPI) of the higher heating rate was 2.2–4.5 times that of the lower heating rate (Table 3). This showed that the rising heating rate significantly improved the pyrolysis performance and reduced the reaction time. From the perspective of industrial applications, 40 °C/min appeared as a better choice. Despite this, the reason and trade-offs for the selection of 20 °C/min for further discussion were as follows: (1) the three heating rates affected the TG and DTG curves of the samples similarly; (2) not only does a lower heating rate than 20 °C/min prolong the heating time, but also it increases the energy consumption and treatment cost of the pyrolysis; and (3) a higher heating rate than 20 °C/min cannot pyrolyze the feedstocks fully which in turn may raise the risk of reactor damage.

Fig. 2.

The (D)TG curves of the pyrolysis of (a) MB, (b) MF, and (c) IT at the three heating rates.

Table 3.

Pyrolysis characteristic parameters for MB, MF, and IT at the three heating rates (β).

| Parameters | β (°C/min) | MB | MF | IT stage I | IT stage II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial temperature (Ti,°C) | 10 | 363.3 | 397.5 | 216.6 | 378.0 |

| 20 | 375.8 | 414.7 | 227.3 | 388.0 | |

| 40 | 402.2 | 429.5 | 248.4 | 422.2 | |

| Peak temperature (Tp,°C) | 10 | 438.1 | 458.9 | 289.0 | 459.2 |

| 20 | 449.7 | 471.8 | 304.6 | 470.2 | |

| 40 | 464.2 | 483.9 | 325.0 | 486.4 | |

| Half-peak width temperature range (ΔT1/2, °C) | 10 | 22.0 | 15.0 | 35.0 | 31.5 |

| 20 | 23.5 | 16.5 | 37.5 | 34.5 | |

| 40 | 24.5 | 18.5 | 51.0 | 51.5 | |

| Final temperature (Tf,°C) | 10 | 566.8 | 480.2 | 378.0 | 547.9 |

| 20 | 581.4 | 496.3 | 388.0 | 607.6 | |

| 40 | 601.3 | 514.6 | 422.2 | 639.3 | |

| Peak decomposition rate (−Rp,%/min) | 10 | 16.82 | 27.25 | 10.04 | 2.71 |

| 20 | 33.46 | 54.46 | 21.72 | 5.14 | |

| 40 | 77.84 | 110.68 | 35.98 | 8.27 | |

| Average decomposition rate (−Rv, %/min) | 10 | 4.19 | 11.96 | 4.62 | 0.89 |

| 20 | 8.69 | 24.89 | 10.66 | 1.83 | |

| 40 | 19.38 | 55.21 | 22.18 | 6.38 | |

| Weight loss (Mf, %) | 10 | 86.68 | 99.24 | 72.10 | 19.72 |

| 20 | 86.88 | 99.56 | 72.49 | 19.81 | |

| 40 | 87.20 | 99.38 | 73.18 | 19.13 | |

| Residue (%) | 10 | 13.32 | 0.76 | – | 8.18 |

| 20 | 13.12 | 0.44 | – | 7.70 | |

| 40 | 12.80 | 0.62 | – | 7.69 | |

| Comprehensive pyrolysis index | 10 | 174.35 | 1181.67 | 152.71 | 0.87 |

| (CPI, %3/(min2·°C3·105)) | 20 | 636.11 | 4180.34 | 646.47 | 2.97 |

| 40 | 2875.55 | 15,793.85 | 1418.17 | 9.54 |

Both MB and MF underwent one-stage pyrolysis process in the ranges of 375.8–581.4 °C and 414.7–496.3 °C, respectively. Given the higher peak decomposition rate of MF (54.46 %/min) than MB (33.46 %/min) and higher weight loss (M f) of MF (99.56 %) than MB (86.89 %) (Table 3), MF had a faster pyrolysis rate and more degradation. The thermal degradation mechanism of MB included the primary depolymerization and further deoxidation. The depolymerization produced aromatic compounds which were further condensed into polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to form pyrolytic carbon, followed by the release of a large amount of CO and CO2 (Montaudo et al., 1993; Zheng et al., 2007). Therefore, the ash content of the MB pyrolysis was higher than that of the others (Table 3). The thermal degradation mechanism of MF was the random and end-chain scissions (Furushima et al., 2020). In its pyrolysis, heat flow generated at the high temperature broke the van der Waals force and hydrogen bonds between molecules, thus forming small molecules and some amorphous regions after which small molecular hydrocarbons decomposed into liquid and gaseous products which finally devolatilized/decomposed to form coke (Murata et al., 2002).

The IT pyrolysis process was divided into two stages in the ranges of 227.3–388.0 °C and 388.0–607.6 °C, with the peak decomposition rates of 21.72 and 5.14 %/min, respectively (Table 3). The main reaction in its first stage was dehydrochlorination that released HCl and other chlorinated hydrocarbons, with a weight loss of 72.49 %. In its second stage, the main reaction was the rearrangement and cyclization of conjugated olefins where volatiles generated were benzene and benzene derivatives, with a weight loss of 19.81 % (Table 3) (Zhou et al., 2020). To sum up, the first stage was the main reaction of the IT pyrolysis, with its faster pyrolysis rate and stronger weight-reduction effect. From the comparison of the peak decomposition rates, the pyrolysis performance of the feedstocks can be derived. For example, given the peak degradation rates of biomass such as wood saw dust (1.28 %/min) and rice straw (6.88 %/min) and other plastics such as LDPE (45.2 %/min) and PP (54.7 %/min), the pyrolysis performance of our feedstocks were the same as those of the other pure plastics but higher than those of biomass (Chanaka Udayanga et al., 2019; Clauser et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2020a).

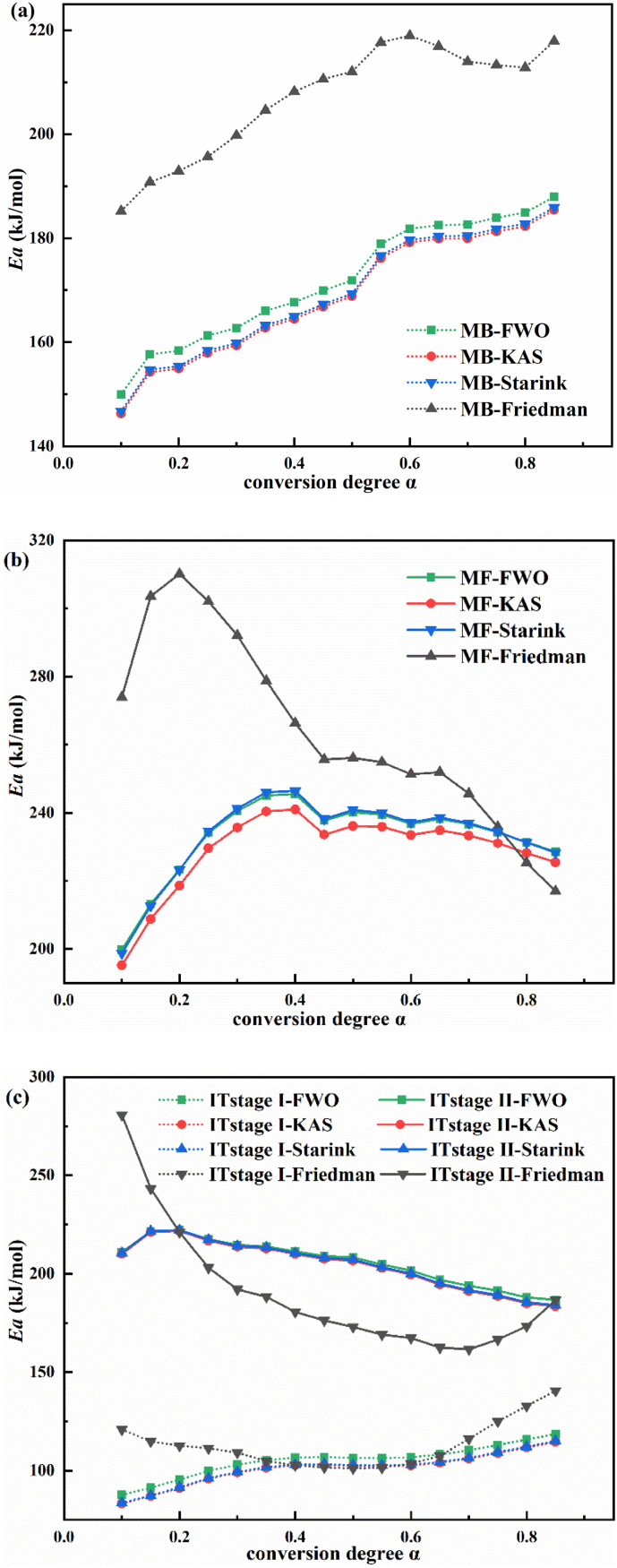

3.3. The influence of feedstock type and conversion degree on pyrolysis kinetics

The FWO, Starink, KAS, and Friedman methods were used to detect the variation in activation energy (Ea) of the main pyrolysis stages for each sample when 0.1 < α < 0.85 with an interval of 0.05 (Fig. 3 and Table S2). The FWO, Starink, and KAS methods resulted in the similar E a estimated values and trends but in the different ones from the Friedman method probably since the Friedman method does not use a mathematical approximation to denoise the data (Song et al., 2019). Therefore, the FWO-derived estimates were selected for further discussion. Given the E a estimates of MB (171.77 kJ/mol), MF (232.79 kJ/mol), IT stage I (105.14 kJ/mol), and IT stage II (205.76 kJ/mol), MF was the most difficult one to degrade (Chen et al., 2015). The IT stage II required a higher degradation temperature to break the higher energy barrier, as was consistent with the results in Section 3.2. The activation energy of the waste plastic types in the N2 atmosphere was previously reported as follows: LDPE (446.7 kJ/mol) > HDPE (445.9 kJ/mol) > PS (283.4 kJ/mol) > PP (274.2 kJ/mol) > PET (273.2 kJ/mol) (Saad et al., 2021). In other words, the MB (PET), MF (PP), and IT (PVC and plasticizer) were easier to pyrolyze than the other common plastics.

Fig. 3.

Changes in Ea of the pyrolysis of (a) MB, (b) MF, and (c) the two stages of IT according to the FWO, KAS, Starink, and Friedman methods.

The gradual upward trend in E a of MB and IT stage I may be caused by the accumulation of recalcitrant residues or fixed carbon. IT stage II presented an initially rising and then falling trend, with α = 0.15 as the turning point. The M-shaped trend of MF indicated its complex reaction process including the chain scission and molecular recombination (Singh et al., 2020b). The downward trend in E a at the end of MF and IT stage II with the rising value of α may be attributed to the degradation of recalcitrant residues or fixed carbon, as can be corroborated by the results of proximate analysis.

3.4. The influence of feedstock type and conversion degree on pyrolysis thermodynamics

The estimated values of ΔH, ΔG, A, and ΔS were obtained according to the FWO method at a heating rate of 20 °C/min (Fig. 4 and Table S3). ΔH is the energy difference between the original reactant and the activated clathrate. The smaller average gap between E a and ΔH is, the more easily the reaction proceeds (Huang et al., 2020). The average gap between E a and ΔH was of the following pattern (Fig. 4a): IT stage I (4.77 kJ/mol) < MB (5.95 kJ/mol) < MF (6.17 kJ/mol) < IT stage II (6.32 kJ/mol). ΔG reflects the pyrolysis reaction direction and the change in gross energy of the system when the activated clathrate grows. Given their ΔG values, the thermal conversion reaction of MF (187.18 kJ/mol) was more difficult than that of MB (181.91 kJ/mol) but similar to that of waste syringes (PP) (Ding et al., 2021a). All the sample reactions produced a large quantity of volatiles (Section 3.1). ΔG rose gradually with the increased conversion degree. The thermal conversion reaction of IT stage II (192.95 kJ/mol) was more difficult than that of IT stage I (145.00 kJ/mol) (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Change in the thermodynamic parameters of the MB, MF, and IT pyrolysis of (a) ΔH, (b) ΔG, (c) A, and (d) ΔS.

The value of A indicates the collision frequency of the reactant-activated molecules, as is the inherent properties of the pyrolysis reaction, regardless of temperature and concentration. A ≥ 109 indicates high reactivity of the reaction system, with its higher value referring to the higher energy requirement; that is, the higher activation energy (Section 3.3). Except for IT stage I when α = 0.10–0.20, the A values of all the samples were >109. The estimated values of A were of the following pattern: IT stage I (2.81 × 108–1.20 × 1010) < MB (1.89 × 1011–1.66 × 1013) < IT stage II (1.19 × 1012–7.82 × 1015) < MF (2.97 × 1014–2.41 × 1017) (Fig. 4c). ΔS is a measure of the degree of disorder in the system, with its positive value pointing to the increased disorder of the system and the high reaction activity. The highest and lowest reactivity belonged to the pyrolysis of MF (53.10 J/mol) and IT stage I (−77.99 J/mol), respectively. The pyrolysis of IT stage II exhibited fluctuating positive and negative ΔS values (Fig. 4d). This indicated the presence of the complex reaction and the numerous products which was explored via pyrolysis-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis in Section 3.8.

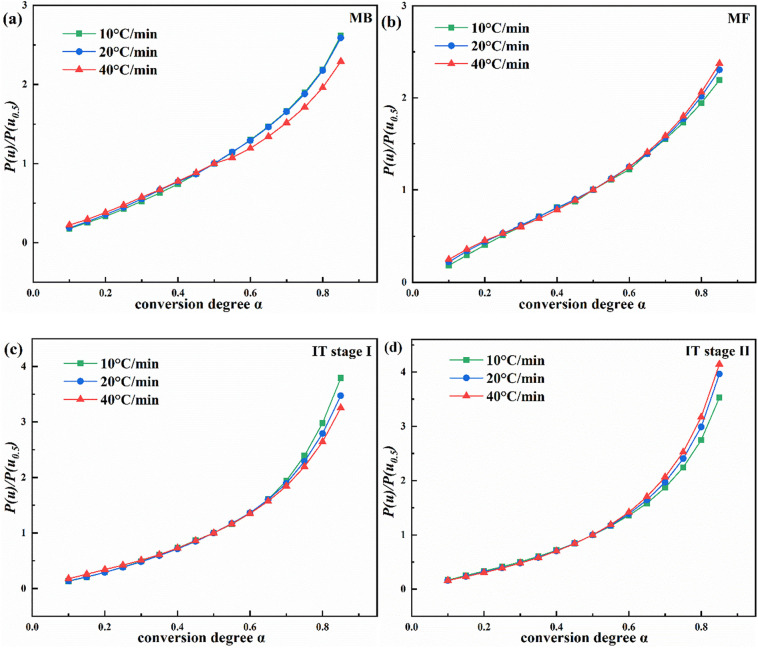

3.5. Verification of pyrolytic reaction mechanisms

In order to better understand the kinetics of the four-step reaction, the kinetic model, pre-exponential factor (A), and reaction order were introduced. To select the most suitable mechanisms of the decomposition reactions of the samples, the E a values estimated according to the FWO, KAS, and Starink methods were adopted to perform the integral principal graph analysis. Given the relationship between P(u)/P(u 0.5) and conversion degree (α) (Fig. 5a-d), regardless of the heating rate, the mechanism of one single pyrolysis reaction stage can be expressed as a single model (Aslan et al., 2017). Since the P(u)/P(u 0.5) curves at three heating rates did not differ significantly from one another, 20 °C/min was chosen to initially define the dynamic mechanism whose predictions were in turn verified through the inverse calculation.

Fig. 5.

The P(u)/P(u0.5) versus conversion degree (α) plots for the (a) MB, (b) MF, (c-d) IT stages I-II pyrolysis at the three heating rates and (e-h) at 20 °C/min and their comparisons to the G(α)/G(α0.5) versus conversion degree (α) plots for diverse reaction mechanisms.

By combining with the previously estimated activation energies and their temperature dependency, the most suitable model was selected (Fig. 5e-h). The theoretical G(α)/G(α 0.5) and experimental P(u)/P(u 0.5) plots were compared for each sample to find the optimal mechanism function with a step of 0.1. The optimal functions of MB, MF, IT stage I, and IT stage II were determined as A1.3, A1.4, F1.2, and F1.6, respectively. The close agreement between the experimental and theoretical curves of the different conversion rates in the pyrolysis confirmed the accuracy of the obtained kinetic model in each sample.

The general forms of the An and Fn models were thus:

| (10) |

From the partitioning of the integral functions of the An and Fn models into the following formula, the best-fit order (n) of the pyrolysis reaction models could be derived:

| (11) |

| (12) |

The optimal value of n was determined at a step size of 0.1 so as to cover the different values of n through the plots of [− ln (1 − α)]1/n and versus EP(u) × 10 n /βR (Fig. 6a-d) whose best-fit regression line slopes according to the highest R 2 value yielded the values of A. The kinetic triplets of E a, ƒ (α) and A of the MB, MF and two stages of IT pyrolysis were presented (Table 4). The experimental values closely matched the estimated values, with their high correlation indicating the reliability of the estimated values (Fig. 6e-h).

Fig. 6.

Curve of G(α) and EP(u) ×10n/βR for (a) MB, (b) MF, (c-d) IT stages I-II pyrolysis and their bets-fit lines. The experimental (lines) and predicted (dots) conversion data for (e) MB, (f) MF, and (g-h) IT stages I-II pyrolysis.

Table 4.

Kinetic parameters of Ea, ƒ (α), and A for the MB, MF, and IT pyrolysis.

| Samples | β (°C/min) | Ea (kJ/mol) | f (a) | FE | A | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB | 10 | 169.92 | 1.3(1 − α)[−ln(1 − α)]1/1.3 | y = 1.2731x + 0.0057 | 1.2731 × 1012 | 0.9998 |

| 20 | y = 1.4865x − 0.0158 | 1.4865 × 1012 | 0.9998 | |||

| 40 | y = 1.5419x − 0.0989 | 1.5419 × 1012 | 0.9987 | |||

| MF | 10 | 231.56 | 1.4(1 − α)[−ln(1 − α)]1/1.4 | y = 1.4616x − 0.0044 | 1.4616 × 1016 | 0.9986 |

| 20 | y = 1.4754x − 0.0246 | 1.4754 × 1016 | 0.9993 | |||

| 40 | y = 1.5179x − 0.0217 | 1.5179 × 1016 | 0.9977 | |||

| IT stage I | 10 | 102.51 | (1 − α)1.2 | y = 1.2067x + 0.0116 | 1.2067 × 109 | 0.9973 |

| 20 | y = 1.4354x − 0.0153 | 1.4354 × 109 | 0.9997 | |||

| 40 | y = 1.4692x − 0.0722 | 1.4692 × 109 | 0.9999 | |||

| IT stage II | 10 | 204.79 | (1 − α)1.6 | y = 1.6960x − 0.0455 | 1.6960 × 1014 | 0.9999 |

| 20 | y = 1.8877x + 0.0237 | 1.8877 × 1014 | 0.9992 | |||

| 40 | y = 1.5081x + 0.0528 | 1.5081 × 1014 | 0.9988 |

3.6. (TG-)FTIR analysis of functional groups

FTIR analysis was employed to detect the functional groups of the samples and determine their main constituents in comparison with the existing literature (Fig. 7a). The results showed that the main components of MB, MF, and IT were plastics PET, PP, and PVC, respectively (Fan et al., 2021). Table S4 lists a summary of IR bonds used in the functional group analysis. The presence of the functional groups in volatiles was determined using TG-FTIR analysis (Fig. 7b). Since the heating rate did not change the type of volatiles matter in the pyrolysis (Ming et al., 2020), 20 °C/min and the IR spectrum intercepted at the temperature of the highest peak of the pyrolysis rate obtained in Section 3.2 were used for evolved gas analysis. The gases formed in the wavenumber range of 3200–2800 cm−1 mainly indicated the existence of alkanes and alkenes, while the existence of CO and CO2 was also apparent in the range of 2200–2400 cm−1. The sharp and strong absorption peak of 1750–1610 cm−1 (C O) belonged to the carboxyl group on benzoic acid in MB and IT. The slight absorption peak between 1680 and 1620 cm−1 corresponded to the C C stretching vibration on the benzene ring. In the ranges of 1400–1340 cm−1 and 1200–870 cm−1, the scissoring and bending vibrations of C—H were indicative of the existence of alkanes and alkenes, respectively (Kai et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2020b; Xu et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2020).

Fig. 7.

FTIR analysis of functional groups of the samples (a) before and (b) after the pyrolysis.

MF and IT produced a large amount of alkanes and alkenes, while MB produced a large amount of CO and CO2. For MB, the absorption peaks of 3620–3550 cm−1 and 1320–1180 cm−1 corresponded to O—H and C—O stretching vibrations, respectively, indicating the presence of alcohols or phenols. Aromatic hydrocarbons can be further polymerized into polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which can generate CH4 and H2 through the demethylation and dehydrogenation reactions (Zhang et al., 2021). However, H2 was not found in the evolved gases which may be due to the low content of H (4.78 %) in MB. The main alkane product of MF was CH4, while its main alkene product was propylene (Ding et al., 2021a). For IT, a series of strong absorption peaks of 3100–2600 cm−1 belonged to the asymmetric stretching vibration of H—Cl, while the peak of 750–660 cm−1 verified the existence of —C—Cl bonds, indicating that HCl and chlorinated hydrocarbons were the main gaseous products.

3.7. Py-GC/MS analysis of gaseous products

The results of the pyrolysis of MB, MF, and IT at 900 °C are shown in Table 5. The relative content of the products was expressed in the peak area percentage in the mass spectrum. The types of the MB pyrolysis products were relatively diverse, containing aromatic compounds (34.08 %) among which 3,4-dihydrocoumarin reached 11.94 %, followed by ester compounds (9.55 %) and benzoic acid (8.15 %). The main pyrolysis products of MF were C3-C35 alkenes (22.75 %), C5-C32 alkanes (17.95 %), and 2,4-dimethyl-1-heptene (9.38 %) (Fig. 8 ). As can be seen in Section 3.2, the pyrolysis temperatures of MF and MB were similar, but their pyrolysis products were different due to their different materials.

Table 5.

Py-GC/MS-detected product distributions of MB, MF, and IT at 900 °C.

| Class | Name | Formula | Area (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MB | MF | IT | |||

| Alkanes | Pentane | C5H12 | – | 1.74 | – |

| Cyclopentane, 1,2,3,4,5-pentamethyl- | C10H20 | – | 1.73 | – | |

| Cyclooctane, 1,4-dimethyl-, trans- | C10H20 | – | 1.91 | – | |

| Cyclohexane, 1,2,3,4,5,6-hexaethyl- | C18H36 | – | 2.67 | – | |

| Cyclotetradecane, 1,7,11-trimethyl-4-(1-methylethyl)- | C20H40 | – | 3.63 | – | |

| Dodecane, 1-cyclopentyl-4-(3-cyclopentylpropyl)- | C25H48 | – | 5.04 | – | |

| 1,1,3,6-tetramethyl-2-(3,6,10,13,14-pentamethyl-3-ethyl-pentadecyl)cyclohexane | C32H64 | – | 1.23 | – | |

| Sum | 17.95 | ||||

| Alkenes | Propene | C3H6 | – | 1.76 | – |

| 1-Pentene, 2-methyl- | C6H12 | – | 1.39 | – | |

| 3-Ethyl-2-hexene | C8H16 | – | – | 0.48 | |

| Heptane, 3-methylene- | C8H16 | – | – | 3.74 | |

| 3-Heptene-3-methyl | C8H16 | – | – | 5.54 | |

| 2-Heptene, 3-methyl- | C8H16 | – | – | 3.34 | |

| 2-Octene, (E)- | C8H16 | – | – | 0.99 | |

| 2,3-Dimethyl-2-heptene | C9H18 | – | 1.10 | – | |

| 2,4-Dimethyl-1-heptene | C9H18 | – | 9.38 | – | |

| Nonane, 2-methyl-3-methylene- | C11H22 | – | 0.92 | – | |

| 3-Tetradecene, (Z)- | C14H28 | – | 0.81 | – | |

| 3-Hexadecene, (Z)- | C16H32 | – | 0.83 | – | |

| 9-Eicosene, (E)- | C20H40 | – | 1.20 | – | |

| Neophytadiene | C20H38 | – | 4.29 | – | |

| 1-Tetracosene | C24H48 | – | – | – | |

| 1-Hexacosene | C26H52 | – | 1.07 | – | |

| 17-Pentatriacontene | C35H70 | – | – | 0.32 | |

| Sum | – | 22.75 | 14.41 | ||

| Aromatics | Benzene | C6H6 | 3.56 | – | 1.59 |

| p-Xylene | C8H10 | – | – | 0.30 | |

| 3,4-Dihydrocoumarin | C9H8O2 | 11.94 | – | – | |

| Biphenyl | C12H10 | 2.51 | – | – | |

| 2,7-Dihydroxynaphthalene | C10H8O2 | 0.80 | – | – | |

| 9H-Fluoren-9-one | C13H8O | 0.36 | – | – | |

| Benzophenone | C13H10O | 0.42 | – | – | |

| (1,1’-Biphenyl)-2,2′-dicarboxaldehyde | C14H10O2 | 0.51 | – | – | |

| 4-Phenylbenzhydrazide | C13H12N2O | 5.09 | – | – | |

| Ethanedione, (4-methylphenyl) phenyl- | C15H12O2 | 0.48 | – | – | |

| p-Terphenyl | C18H14 | 0.67 | – | – | |

| 9H-Fluorene, 9-phenyl- | C19H14 | 0.35 | – | – | |

| Lapachone | C15H14O3 | 1.44 | – | – | |

| 1,1′:4′,1″:4″,1‴-Quaterphenyl | C24H18 | 1.19 | – | – | |

| 4,4′-Methylenebisphenol, 2,2′,6′-tris(tert.-butyl)-6-methyl- | C26H38O2 | 2.98 | – | – | |

| 3,6,13,16-tetraoxatricyclo [16.2.2.2(8,11)] tetracosa-8,10,18,20,21,23-hexaene-2,7,12,17-tetrone | C20H16O8 | 1.78 | – | – | |

| Sum | 34.08 | 1.89 | |||

| Aldehydes | Acetaldehyde | C2H4O | 5.66 | – | – |

| Sum | 5.66 | ||||

| Alcohols | 1-Hexanol, 2-ethyl- | C8H18O | – | – | 3.94 |

| 7-Methoxy-2-methylquinolin-4-ol | C11H11NO2 | 1.85 | – | 0.35 | |

| Octacosanol | C28H58O | – | 6.40 | – | |

| Spinosine | C28H32O15 | 1.15 | – | – | |

| Sum | 3.00 | 6.40 | 4.29 | ||

| Acids | Benzoic acid | C7H6O2 | 8.15 | – | – |

| 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid | C8H6O4 | – | – | 5.93 | |

| 3-(3-Methoxyphenyl)propionic acid | C10H12O3 | – | – | 0.92 | |

| Sum | 8.15 | 6.85 | |||

| Esters | Ethyl glycolate | C4H8O3 | 1.43 | – | – |

| 2-Butenoic acid, 2-methoxy-3-methyl-, methyl ester | C7H12O3 | 0.54 | – | – | |

| Benzoic acid, 2-ethylhexyl ester | C15H22O2 | – | – | 1.75 | |

| 1,2-Ethanediol, dibenzoate | C16H14O4 | 6.23 | – | – | |

| 11,13-Dimethyl-12-tetradecen-1-ol acetate | C18H34O2 | – | 1.52 | – | |

| Terephthalic acid, ethyl 2-nitro-3-methylbenzyl ester | C18H17NO6 | 1.00 | – | – | |

| D-Glucitol, 4-O-methyl-, pentaacetate | C17H26O11 | 0.35 | – | – | |

| Bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate | C24H38O4 | – | – | 53.58 | |

| Sum | 9.55 | 1.52 | 55.33 | ||

| Ethers | Oxirane, 2,2′-[1,4-butanediylbis(oxymethylene)] | C10H18O4 | 0.29 | – | – |

| Sum | 0.29 | ||||

| Chlorinated-hydrocarbons | 2-Chloro-octane | C8H17Cl | – | – | 0.32 |

| 3-Chloromethyl-heptane | C8H17Cl | – | – | 1.42 | |

| Sum | 1.74 | ||||

| Furans | Tetrahydrofuran | C4H8O | 0.80 | – | – |

| Sum | 0.80 | ||||

Fig. 8.

The proportions of gaseous products according to Py-GC/MS analysis.

The IT products had obvious characteristics such as esters, bis (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (53.58 %), and alkenes (14.41 %) of which 3-heptene-3-methyl accounted for 5.54 %. Primarily, its chlorinated hydrocarbons included 3-chloromethyl-heptane (1.42 %) and 2-chloro-octane (0.32 %), while its aromatic compounds included benzene (1.59 %) and p-xylene (0.3 %). The above analysis results were consistent with the FTIR results. Due to the rich variety of the products, only the products with the higher peaks were taken into account. In other words, the proportion of the actually produced compounds was slightly higher than the data presented here. For pure PVC (Zhou et al., 2020) at 650 °C, the relative contents of isoprene and 1,3-cyclopentadiene were estimated at 1.41 % and 1.87 %, while the production of benzene fell from 13.6 to 8.1 % with the increasing temperature. In addition to the influence of plasticizers, the high final temperature helped the secondary reaction of benzene series and avoided the formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

3.8. Pyrolytic mechanisms and pathways

Given the above discussions of the TG-FTIR and Py-GC/MS results and the previous studies, the possible reaction pathways in the pyrolysis of MB, MF, and IT are shown in Fig. 9 . The thermal degradation of polymers occurs through a free radical mechanism based on chain scissions and involves both synergistic and ionic reactions (McNeill et al., 1995; Zhou et al., 2016). Taking the three monomers as an example (Fig. 9A), the pyrolysis of PET in MB included the primary depolymerization and further deoxidation. Random cleavage occurred between oxygen and carbon atoms. There may be the following four types of 1 and 3; 1 and 4; 2 and 3; and 2 and 4. In the case of cleavage, short chains and monomer compounds with benzoic acid end or vinyloxycarbonyl benzene end were produced. The depolymerization continued until no polymer remained, and aromatic compounds (e.g., benzoic acid, p-xylene, styrene, and benzene) were produced. Aromatics can be further condensed into polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to form pyrolytic carbon (e.g., biphenyl, p-terphenyl, and 1,1′:4′,1″:4″,1‴-quaterphenyl) (Montaudo et al., 1993; Zheng et al., 2007). The deoxygenation reaction pathways A, B, and D were accompanied by the production of CO2, while the pathways C and E were accompanied by the production of CO which conformed to the results of FTIR analysis.

Fig. 9.

Pyrolysis mechanisms of MB, MF, and IT of (A) MB, (B) MF, (C-D) IT, and (E) plasticizer in IT.

Given the three monomers as an example (Fig. 9B), the pyrolysis of PP in MF was explained by the mechanism of intramolecular hydrogen transfer after random cracking [42]. Its pyrolysis process included intermolecular hydrogen transfer, β-fracture, and intermolecular hydrogen extraction reactions [43]. The fracture position can be 1 or 2, forming the four chain structures a, b, c, and d, respectively, and continued to break to form alkenes, dienes, alkanes, and cycloalkanes. The other products included short-chain hydrocarbons (e.g., 2-methyl-1-pentene, propene, and pentane) and long-chain hydrocarbons (e.g., 1-tetracosene and 9-eicosene).

The degradation of PVC started by removing the unstable chlorine to form hydrogen chloride and double bonds (Jordan et al., 2001). The double bond converted the adjacent secondary chlorine to the more unstable allyl chloride which was removed in the form of hydrogen chloride. Fig. 9C shows the possible pathways for the formation of main aromatic compounds in IT (Miranda et al., 2001; Xu et al., 2018). The dehydrochlorination reaction occurred on the polyvinyl chloride chain whose chain structure was randomly broken. There may be the following three situations of 1 and 2; 1 and 3; and 1 and 4, while three chlorinated olefins with carbon numbers of six, seven, and eight were generated, respectively. As the dechlorination or dehydrochlorination continued, molecular chain cyclization occurred to form chlorobenzene, chlorotoluene, p-xylene, benzyl chloride, and other aromatic compounds. This was because a small number of chlorine atoms were not released in the form of hydrogen chloride which led to the formation of chlorinated hydrocarbons. Afterwards, aromatics were further polycondensed into polycyclic aromatics. Fig. 9D shows the possible pathways for the formation of alkenes and alkanes in IT (Gui et al., 2013). Similarly, through the dehydrochlorination, scission, dechlorination, and rearrangement reactions, the polyvinyl chloride chain generated 3-methyl-3-heptene, 3-methyl-2-heptene, 2-chloro-octane, and other products. The plasticizer used to make IT was bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate. Fig. 9E shows its possible decomposition pathways. Its products included phthalic acid, 2-ethylhexyl alcohol isomers, and 2-ethylhexyl aldehyde isomers (Wang, 2000).

3.9. Environmentally and energetically optimal pyrolytic settings

Cross-validation serves to test the predictive power against a dataset unseen by the model by feeding the model with a different portion of equally and randomly partitioned data on each iteration. Based on the 5-fold cross-validation, the predictive power of the best-fit ANN in Fig. 10 varied between 6.98 % for C—Cl and 98.28 % for RM (Table 6). As the cross-validation-derived performance measures, the highest coefficient of determination (R 2) and lowest root mean square error (RMSE) values were chosen using a trial-and-error approach so as to decide the hyperparameters and architecture of the best-fit ANN. Thus, the selected hyperparameters were the hyperbolic tangent (Tan H) activation function, one hidden layer with three neurons, and a learning rate of 0.1. The ANN-based joint optimization of the 14 response objectives led to the composite desirability curve (D) of 0.48 (Fig. 11 ). The environmentally and energetically response objectives adopted were to maximize DTG, O—H, C O, C C, and C—O and minimize RM, CO2, CO, CH, CH3, CH2, R-CH CH2, H—Cl, and C—Cl. As a result, the range of 559–900 °C and MF appeared as the environmentally and energetically optimal pyrolytic settings. The three feedstock types (FT) of MF, MB, and IT did not differ significantly from one another according to the composite desirability (D) curve but slightly according to the individual desirability curves (Fig. 11). The relative importance of the total (main and interaction) effects of the two predictors (FT and temperature) to the responses was determined using the Monte Carlo resampling simulations. In terms of the overall total effect, the Monte Carlo simulations pointed to the temperature as the primary driver of the environmental and energetic behavior of the pyrolysis. Individually, the strongest and weakest total effects occurred on DTG and R-CH CH2 with the temperature and on R-CH CH2 and RM with the feedstock type, respectively. The combination of the predictors exerted the strongest and weakest interaction effects on R-CH CH2 and RM, respectively. Combined with insights in Section 3.2, the adoption of 559 °C as the final pyrolysis temperature and 40 °C/min as the pyrolysis heating rate appeared as the best choice from an industrial perspective because the former ensures both the large waste reduction and energy savings, while the latter shortens the waste treatment time and achieves energy savings.

Fig. 10.

The architecture of the best-fit ANN used in this study.

Table 6.

Performance measures of the best-fit ANN used in this study.

| Response | Parameter | Training | 5-fold validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| RM (%) | R2 | 0.9833 | 0.9828 |

| RMSE | 5.65 | 5.73 | |

| n | 61,322 | 15,330 | |

| DTG (%/min) | R2 | 0.5445 | 0.5375 |

| RMSE | 6.74 | 6.96 | |

| n | 61,322 | 15,330 | |

| O—H | R2 | 0.9629 | 0.9728 |

| RMSE | 0.001 | 0.0008 | |

| n | 197 | 53 | |

| CO2 | R2 | 0.9574 | 0.9470 |

| RMSE | 0.0005 | 0.0005 | |

| n | 197 | 53 | |

| CO | R2 | 0.9640 | 0.9527 |

| RMSE | 0.002 | 0.002 | |

| n | 197 | 53 | |

| C O | R2 | 0.6584 | 0.5725 |

| RMSE | 0.013 | 0.016 | |

| n | 393 | 107 | |

| C C | R2 | 0.8220 | 0.7478 |

| RMSE | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| n | 407 | 93 | |

| C—O | R2 | 0.3409 | 0.2744 |

| RMSE | 0.013 | 0.016 | |

| n | 393 | 107 | |

| C—H | R2 | 0.6337 | 0.4683 |

| RMSE | 0.007 | 0.009 | |

| n | 603 | 147 | |

| CH3 | R2 | 0.8028 | 0.6794 |

| RMSE | 0.0099 | 0.0085 | |

| n | 406 | 94 | |

| CH2 | R2 | 0.7730 | 0.6015 |

| RMSE | 0.0238 | 0.0222 | |

| n | 406 | 94 | |

| R-CH CH2 | R2 | 0.9694 | 0.9629 |

| RMSE | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| n | 210 | 40 | |

| H—Cl | R2 | 0.3035 | 0.6903 |

| RMSE | 0.004 | 0.004 | |

| n | 196 | 54 | |

| C—Cl | R2 | 0.0662 | 0.0698 |

| RMSE | 0.002 | 0.003 | |

| n | 196 | 54 |

Fig. 11.

ANN-based joint optimization of the 14 response objectives. The red-to-white color ramp indicates the relatively most and least important drivers, respectively.

4. Conclusion

The volatiles contents of MB, MF, and IT were all higher than 92 %, and their high comprehensive pyrolysis index pointed to their great potential for energy recovery. MF exhibited the best pyrolysis performance, while it was possible to recover and purify the MB pyrolysis gas products rich in 3,4-dihydrocoumarin and benzoic acid. The initial pyrolysis temperatures of MB, MF, and IT were estimated at 375.8, 414.7, and 227.3 °C, respectively. The pyrolysis behaviors of MB and MF conformed to the nucleation growth model (A1.3 and A1.4), while those of IT stages I and II conformed to the geometrical contraction model (F1.2 and F1.6). The main pyrolysis gaseous products were aromatic compounds for MB, C5-C32 alkanes and C3-C35 alkenes for MF, and HCl, 3-chloromethyl-heptane, and 2-chloro-octane for IT. The combination of the ANN-based joint optimization and industrial perspective pointed to the final pyrolysis temperature of 559 °C and the heating rate of 40 °C/min as the best choice since this operational condition minimized the wastes while saving time and energy cost. Overall, this study provides practical and new insights into suppressing the generation of persistent organic pollutants, recovering high value-added products, and designing and optimizing medium-to-large-scale reactors. In the future, the separation and purification processes of pyrolyzed volatile products and the co-pyrolysis of different medical wastes remain to be characterized and discussed.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Weijie Xu: Software, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing. Jingyong Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing-review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Ziyi Ding: Formal analysis, Software, Data curation. Jiawei Fu: Formal analysis, Software, Data curation. Fatih Evrendilek: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing-review & editing. Wuming Xie: Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation. Yao He: Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision, Validation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51978175), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (No. 2022A1515010825), and the Scientific and Technological Planning Project of Guangzhou, China (No. 202103000004). We would like to thank teacher Chunxiao Yang at the AnaIysis and Test Center of Guangdong University of Technology for her assistance with the TG-FTIR analysis.

Editor: Daniel CW Tsang

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156710.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data

References

- Al-Salem S.M., Antelava A., Constantinou A., Manos G., Dutta A. A review on thermal and catalytic pyrolysis of plastic solid waste (PSW) J. Environ. Manag. 2017;197:177–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Salem S.M., Lettieri P., Baeyens J. Recycling and recovery routes of plastic solid waste (PSW): a review. Waste Manag. 2009;29:2625–2643. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M.F., Siddiqui M.N. Thermal and catalytic decomposition behavior of PVC mixed plastic waste with petroleum residue. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2005;74:282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan D.I., Parthasarathy P., Goldfarb J.L., Ceylan S. Pyrolysis reaction models of waste tires: application of master-plots method for energy conversion via devolatilization. Waste Manag. 2017;68:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J.M., Chen S.Y. A new iterative linear integral isoconversional method for the determination of the activation energy varying with the conversion degree. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1986–1991. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çepelioğullar Ö., Pütün A.E. Thermal and kinetic behaviors of biomass and plastic wastes in co-pyrolysis. Energ. Convers. Manage. 2013;75:263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Chanaka Udayanga W.D., Veksha A., Giannis A., Lim T.-T. Pyrolysis derived char from municipal and industrial sludge: impact of organic decomposition and inorganic accumulation on the fuel characteristics of char. Waste Manag. 2019;83:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand Malav L., Yadav K.K., Gupta N., Kumar S., Sharma G.K., Krishnan S., Rezania S., Kamyab H., Pham Q.B., Yadav S., Bhattacharyya S., Yadav V.K., Bach Q.-V. A review on municipal solid waste as a renewable source for waste-to-energy project in India: current practices, challenges, and future opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;277 [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Mu L., Jiang B., Yin H., Song X., Li A. TG/DSC-FTIR and py-GC investigation on pyrolysis characteristics of petrochemical wastewater sludge. Bioresour. Technol. 2015;192:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Chen H., Wu X., Zhang J., Evrendilek D.E., Liu J., Liang G., Li W. Temperature- and heating rate-dependent pyrolysis mechanisms and emissions of Chinese medicine residues and numerical reconstruction and optimization of their non-linear dynamics. Renew. Energ. 2021;164:1408–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Clauser N.M., González G., Mendieta C.M., Kruyeniski J., Area M.C., Vallejos M.E. Biomass waste as sustainable raw material for energy and fuels. Renew. Energ. Environ. Pollut. 2021;13:794. [Google Scholar]

- Derringer G., Suich R. Simultaneous optimization of several response variables. J. Qual. Technol. 1980;12:214–219. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maria F., Beccaloni E., Bonadonna L., Cini C., Confalonieri E., La Rosa G., Milana M.R., Testai E., Scaini F. Minimization of spreading of SARS-CoV-2 via household waste produced by subjects affected by COVID-19 or in quarantine. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;743 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z., Chen H., Liu J., Cai H., Evrendilek F., Buyukada M. Pyrolysis dynamics of two medical plastic wastes: drivers, behaviors, evolved gases, reaction mechanisms, and pathways. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021;402 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z., Liu J., Chen H., Huang S., Evrendilek F., He Y., Zheng L. Co-pyrolysis performances, synergistic mechanisms, and products of textile dyeing sludge and medical plastic wastes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;799 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C., Huang Y.-Z., Lin J.-N., Li J. Microplastic constituent identification from admixtures by fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy: the use of polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and nylon (NY) as the model constituents. Environ. Technol. Inno. 2021;23 [Google Scholar]

- Fang S., Jiang L., Li P., Bai J., Chang C. Study on pyrolysis products characteristics of medical waste and fractional condensation of the pyrolysis oil. Energy. 2020;195 [Google Scholar]

- Furushima Y., Ota R., Ohkawa T. Isothermal thermogravimetric method using a fast scanning calorimeter and its application in the isothermal oxidation of nanogram-weight polypropylene. Thermochim. Acta. 2020;694 [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D., Balart R., Sanchez L., Lopez J. Compatibility of recycled PVC/ABS blends. Effect of previous degradation. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2007;47:789–796. [Google Scholar]

- Gui B., Qiao Y., Wan D., Liu S., Han Z., Yao H., Xu M. Nascent tar formation during polyvinylchloride (PVC) pyrolysis. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2013;34:2321–2329. [Google Scholar]

- Han Z., Li J., Gu T., Yan B., Chen G. The synergistic effects of polyvinyl chloride and biomass during combustible solid waste pyrolysis: experimental investigation and modeling. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2020;222 [Google Scholar]

- Hojjat M. Nanofluids as coolant in a shell and tube heat exchanger: ANN modeling and multi-objective optimization. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020;365 [Google Scholar]

- Hong J., Zhan S., Yu Z., Hong J., Qi C. Life-cycle environmental and economic assessment of medical waste treatment. J. Clean. Prod. 2018;174:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Yan Y., Evrendilek F., Buyukada M., Liu J. Combustion behaviors of three bamboo residues: gas emission, kinetic, reaction mechanism and optimization patterns. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;235:549–561. [Google Scholar]

- Huang H., Liu J., Liu H., Evrendilek F., Buyukada M. Pyrolysis of water hyacinth biomass parts: bioenergy, gas emissions, and by-products using TG-FTIR and py-GC/MS analyses. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2020;207 [Google Scholar]

- Imtenan S., Varman M., Masjuki H.H., Kalam M.A., Sajjad H., Arbab M.I., Rizwanul Fattah I.M. Impact of low temperature combustion attaining strategies on diesel engine emissions for diesel and biodiesels: a review. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2014;80:329–356. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K., Suib S., Koberstein J. Determination of the degradation mechanism from the kinetic parameters of dehydrochlorinated poly (vinyl chloride) decomposition. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2001;105:3174–3181. [Google Scholar]

- Kai X., Li R., Yang T., Shen S., Ji Q., Zhang T. Study on the co-pyrolysis of rice straw and high density polyethylene blends using TG-FTIR-MS. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2017;146:20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang J., Liu J., Chen L., Huang H., Evrendilek F. Co-pyrolytic mechanisms and products of textile dyeing sludge and durian shell in changing operational conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;420 [Google Scholar]

- Matsakas L., Gao Q., Jansson S., Rova U., Christakopoulos P. Green conversion of municipal solid wastes into fuels and chemicals. Electron. Biotech. 2017;26:69–83. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill I.C., Memetea L., Cole W. A study of the products of PVC thermal degradation. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 1995;49:181–191. [Google Scholar]

- MEPC . 2020. Annual Report on Prevention and Control of Environmental Pollution by Solid Waste in Large, Medium and Large Cities in 2020. Ministry of Environmental Protection of the People’s Republic of China. [Google Scholar]

- Ming X., Xu F., Jiang Y., Zong P., Wang B., Li J., Qiao Y., Tian Y. Thermal degradation of food waste by TG-FTIR and py-GC/MS: pyrolysis behaviors, products, kinetic and thermodynamic analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020;244 [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R., Pakdel H., Roy C., Vasile C. Vacuum pyrolysis of commingled plastics containing PVC II. Product analysis. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2001;73:47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni-Bandpei A., Majlesi M., Rafiee M., Nojavan S., Nowrouz P., Zolfagharpour H. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) formation during the fast pyrolysis of hazardous health-care waste. Chemosphere. 2019;227:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaudo G., Puglisi C., Samperi F. Primary thermal degradation mechanisms of PET and PBT. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 1993;42:13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Murata K., Hirano Y., Sakata Y., Uddin M.A. Basic study on a continuous flow reactor for thermal degradation of polymers. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2002;65:71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Paraschiv M., Kuncser R., Tazerout M., Prisecaru T. New energy value chain through pyrolysis of hospital plastic waste. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015;87:424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Saad J.M., Williams P.T., Zhang Y.S., Yao D., Yang H., Zhou H. Comparison of waste plastics pyrolysis under nitrogen and carbon dioxide atmospheres: a thermogravimetric and kinetic study. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 2021;156 [Google Scholar]

- Sharifzadeh M., Sadeqzadeh M., Guo M., Borhani T.N., Murthy Konda N.V.S.N., Garcia M.C., Wang L., Hallett J., Shah N. The multi-scale challenges of biomass fast pyrolysis and bio-oil upgrading: review of the state of art and future research directions. Prog. Energ. Combust. 2019;71:1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Tang Y., Zhang Z., Zheng C. COVID-19 waste management: Effective and successful measures in Wuhan, China. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2020;163:105071. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R.K., Ruj B., Sadhukhan A.K., Gupta P. A TG-FTIR investigation on the co-pyrolysis of the waste HDPE, PP, PS and PET under high heating conditions. J. Energy Inst. 2020;93:1020–1035. [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Hu J., Evrendilek F., Buyukada M., Liang G., Huang W., Liu J. Reaction mechanisms and product patterns of Pteris vittata pyrolysis for cleaner energy. Renew. Energ. 2021;167:600–612. [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Liu J., Evrendilek F., Kuo J., Buyukada M. Combustion behaviors of Pteris vittata using thermogravimetric, kinetic, emission and optimization analyses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;237 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulutan S. A recycling assessment of PVC bottles by means of heat impact evaluation on its reprocessing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1998;69:865–869. [Google Scholar]

- Vyazovkin S. Modification of the integral isoconversional method to account for variation in the activation energy. J. Comput. Chem. 2001;22:178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wan Mahari W.A., Azwar E., Foong S.Y., Ahmed A., Peng W., Tabatabaei M., Aghbashlo M., Park Y.-K., Sonne C., Lam S.S. Valorization of municipal wastes using co-pyrolysis for green energy production, energy security, and environmental sustainability: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;421 [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.C.-Y. Polymer additive analysis by pyrolysis–gas chromatography: I. Plasticizers. J. Chromatogr. A. 2000;883:199–210. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windfeld E.S., Brooks M.S.-L. Medical waste management – a review. J. Environ. Manag. 2015;163:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu F., Wang B., Yang D., Hao J., Qiao Y., Tian Y. Thermal degradation of typical plastics under high heating rate conditions by TG-FTIR: pyrolysis behaviors and kinetic analysis. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2018;171:1106–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Yan J.H., Zhu H.M., Jiang X.G., Chi Y., Cen K.F. Analysis of volatile species kinetics during typical medical waste materials pyrolysis using a distributed activation energy model. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009;162:646–651. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.05.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Yu X., Wu X., Wang J., Yan X., Jiang S., Chen Z. Emergency response to the explosive growth of health care wastes during COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, China. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2021;164:105074. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousef S., Eimontas J., Striugas N., Zakarauskas K., Praspaliauskas M., Abdelnaby M.A. Pyrolysis kinetic behavior and TG-FTIR-GC-MS analysis of metallised food packaging plastics. Fuel. 2020;282 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zhou X.-L., Shao L.-M., Lü F., He P.-J. Upcycling of PET waste into methane-rich gas and hierarchical porous carbon for high-performance supercapacitor by autogenic pressure pyrolysis and activation. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;772 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Cui P., Tian X., Zheng K. Pyrolysis studies of polyethylene terephthalate/silica nanocomposites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007;104:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Liu G., Wang S., Zhang H., Xu F. TG-FTIR and py-GC/MS study of the pyrolysis mechanism and composition of volatiles from flash pyrolysis of PVC. J. Energy Inst. 2020;93:2362–2370. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Broadbelt L.J., Vinu R. Mechanistic understanding of thermochemical conversion of polymers and lignocellulosic biomass. Adv. Chem. Eng. 2016;49:95–198. [Google Scholar]

- Zou H., Zhang J., Liu J., Buyukada M., Evrendilek F., Liang G. Pyrolytic behaviors, kinetics, decomposition mechanisms, product distributions and joint optimization of lentinus edodes stipe. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2020;213 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data