Abstract

Introduction

Institutions have reported decreases in operative volume due to COVID-19. Junior residents have fewer opportunities for operative experience and COVID-19 further jeopardizes their operative exposure. This study quantifies the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on resident operative exposure using resident case logs focusing on junior residents and categorizes the response of surgical residency programs to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

A retrospective multicenter cohort study was conducted; 276,481 case logs were collected from 407 general surgery residents of 18 participating institutions, spanning 2016-2020. Characteristics of each institution and program changes in response to COVID-19 were collected via surveys.

Results

Senior residents performed 117 more cases than junior residents each year (P < 0.001). Prior to the pandemic, senior resident case volume increased each year (38 per year, 95% confidence interval 2.9-74.9) while junior resident case volume remained stagnant (95% confidence interval 13.7-22.0). Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, junior residents reported on average 11% fewer cases when compared to the three prior academic years (P = 0.001). The largest decreases in cases were those with higher resident autonomy (Surgeon Jr, P = 0.03). The greatest impact of COVID-19 on junior resident case volume was in community-based medical centers (246 prepandemic versus 216 during pandemic, P = 0.009) and institutions which reached Stage 3 Program Pandemic Status (P = 0.01).

Conclusions

Residents reported a significant decrease in operative volume during the 2019 academic year, disproportionately impacting junior residents. The long-term consequences of COVID-19 on junior surgical trainee competence and ability to reach cases requirements are yet unknown but are unlikely to be negligible.

Keywords: Case volume, COVID-19, Multicenter, Resident, Surgical education

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented unparalleled challenges for surgical residencies with respect to operative education and experience. Institutions nationwide have proposed adaptive educational models, unique didactic techniques, and flexible scheduling paradigms to provide a temporary solution for residents affected by this pandemic.1, 2, 3, 4 Globally and across specialties, institutions and residents have reported a significant decrease in operative volume and clinical exposure due to the COVID-19 pandemic.4, 5, 6, 7 Single-site institutional survey reports have shown decreases in overall operative volume to 60%-80% of normal during pandemic surges.3 , 6 , 8 Furthermore, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) released elective case triage guidelines to direct an appropriate program intervention with the goal of providing effective patient care while minimizing hospital stay and preserving the health of caregivers.9 While crucial for maintaining trainee health and minimizing COVID-19 transmission, these recommendations also directly limited the number of residents involved per procedure and the overall number of procedures that could be performed, further impacting resident operative exposure.9 In response, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Surgery (ABS) reduced training requirements for graduating residents in recognition of the impact of COVID-19 on institutions’ surgical case volume to ensure the surgical advancement of senior residents.10, 11, 12

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple studies have demonstrated that junior surgical residents have less operative exposure, fewer independent operative experiences per year, and lower overall case volumes than senior trainees.13 Previous studies and expert perspectives have also warned about the “seniorization” of patient care and decreasing opportunity and surgical exposure of junior residents, even before COVID-19.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Thus, junior residents are particularly vulnerable to limitations in educational and operative opportunities, such as those seen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Few studies have reported on the impact of COVID-19 on surgical residents nationally.5 , 8 , 18 These investigations reported stark decreases in resident case volume based on survey responses but lack the granular data to objectively assess the impact on operative experience at the resident level. These studies were also unable to quantitatively assess changes in case volume or the surgical role of the trainee during these encounters. In addition, no studies have addressed the specific impact on junior surgical residents during the COVID-19 pandemic.9, 10, 11, 12

The present study aimed to address the gap in knowledge of the impact of COVID-19 on surgical resident operative exposure and specifically to investigate the impact on junior residents as a particularly vulnerable population. We hypothesized that resident case volume would significantly decrease during the COVID-19 pandemic and that junior residents would be disproportionally impacted when compared to senior residents. All general surgery residents enter their surgical cases in the ACGME Case Log System to track their operative experience for accreditation and certification requirements.19 Assessing general surgery junior resident case logs during this time offers an insight into the operative experiences of vulnerable and less experienced surgical trainees nationwide in the front lines of a global pandemic. While multiple survey studies have reported significant decreases in case volume, to date no study has examined the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on junior resident case volume using empiric ACGME and ABS advancement metrics.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective multicenter cohort study was conducted to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on junior surgical resident case volume. The policies and structural changes residency programs implemented to mitigate the toll on surgical education were also assessed.

Eighteen institutions elected to participate following a recruitment email sent to all members of the Association of Program Directors in Surgery; all ACGME accredited surgical residency programs were eligible to participate. Programs which elected to participate completed a survey detailing descriptive characteristics of their institution, baseline information about their residency program, and details regarding their educational response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including their highest ACGME Program Pandemic Status as of July 1, 2020.19 The Program Pandemic Status has been used by the ACGME to categorize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on an institution's case volume in a systematic fashion and establish specialized guidelines for impacted programs.20 , 21 The three categories are:

-

•

Stage 1: No change in clinical demand.

-

•

Stage 2: Increased but manageable clinical demand.

-

•

Stage 3: Crossing a threshold beyond which the increase in volume and/or severity of illness creates an extraordinary circumstance where routine care education and delivery must be reconfigured to focus only on patient care.

This status has been used by programs to delineate when surges in the pandemic have impeded academic programing including resident education, clinical rotations, and case volume. If a program reported Stage 3, it was interpreted to mean they implemented significant changes to their education program secondary to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Program type (academic, community-based, or military medical center), number of hospital beds, total number of COVID-19 positive patients admitted by the institution prior to July 1, 2020, and educational curricular changes were self-reported by the participating sites (Appendix A). Academic medical centers in this study include those who identify as university-based programs and are consistent with prior investigations.22

The ACGME case log system is a well-established database used by residency programs for reporting surgical case experience during residency training. Surgical residents use this tool to self-report all cases in which they participate.19 These data are used by the ACGME for accreditation decisions and by the ABS as a component of eligibility for board certification. Although the data are self-reported case volumes aggregated per resident and over time, are sufficiently reliable for analyses and used for nationwide policy changes and recommendations.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 , 22, 23, 24, 25

Participating programs submitted their surgical case logs of all junior residents (postgraduate year [PGY] 1-2) between July 1, 2016 and June 30, 2020. As such, cases were categorized as junior qualifying cases only if logged as a First Assistant or Surgeon Jr, were for “major credit” as deemed by the ACGME, only one procedure per case was logged, and the resident was a PGY1 or PGY2 at the time the case was performed. Residents and case logs that did not meet the above inclusion criteria were not categorized as junior resident cases. Senior resident case logs were evaluated on a similar basis, accounting for professional development and/or dedicated research years, for cases in the PGY3 through PGY5 years. Senior resident data that were available for this study were generated from residents who were initially junior residents between 2016 and 2018 and advanced to PGY3 or greater during the 2017-2019 academic years. The first senior residents with available case log data were PGY2 residents in 2016 who became PGY3 residents in 2017. Therefore, no senior resident data were available for analysis prior to 2017.

To improve the accuracy of case logs from participating sites, residents were prompted three times to be up-to-date on their case logs. In addition, resident's case logs were algorithmically flagged if deemed unreliable (less than 40 cases logged in any 6-month period or more than 100 operative procedures logged in any single month). All flagged cases were manually reviewed for accuracy and evaluated for exclusion. Overall, three resident's case logs were excluded for either unreliable inaccuracies or ineligibility, accounting for less than 1% of the total case logs collected.

Case logs reported to be performed between January 1, 2020 and June 30, 2020 were considered to have been during the COVID-19 pandemic. The decision was made a priori to use the aggregated case volumes from 2016-2017, 2017-2018, and 2018-2019 academic years as a historic average, which was then compared to the 2019-2020 academic year to account for program variability over that time. All academic year comparisons regarding the COVID-19 pandemic compared the aggregated 2016-2018 academic years to the 2019-2020 academic years.

The total number of cases reported per resident, change in case volume between PGY1 and PGY2, average case volume per resident, and case volume by program type were calculated. Where appropriate, two-sided t-test, paired t-tests, and bootstrap sampling for nonparametric analyses were used to compare groups with an alpha level of 0.05. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare multiple groups, with Kruskal–Wallis testing for nonparametric data and Dunn's correction for multiple comparisons. Linear regression models were used to assess effect modification between groups. Logistic regression models were used to assess program level binary parameters. Summaries are reported as means with standard deviations unless otherwise noted. Data are visualized using box plots, representing the median and interquartile range. All statistical analyses were completed with R version 4.0.2.26

Institutional review board and institutional participation approval were gained by participating sites as per the site specific policy. Waivers to informed consent for program available data were granted by participating centers institutional review boards and deidentified data were gathered by each program.

Results

Residency program overview

Of the 18 participating institutions, a broad range of geographic locations, size, and institutional diversity was attained. All four regions of the country were evenly represented (∼15%-30% per region), including 13 states, and there was an approximately equal division between academic and community-based medical centers (8 [44%] versus 10 [56%]). Program size ranged from 4 to 50 residents per institution. Programs of every level of ACGME Program Pandemic Status participated in the study (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Descriptive overview of resident case logs and residency program attributes.

| Program descriptors | Parameters |

|---|---|

| Institutional participants [N] | 18 |

| Logged cases collected [N] | 276,481 |

| Residents [N] | 407 |

| Program region [N, %] | - |

| Northeast | 5 (28%) |

| South | 6 (33%) |

| Midwest | 4 (22%) |

| West | 3 (17%) |

| Program type [N, %] | - |

| Academic medical center | 8 (44%) |

| Community-based | 10 (56%) |

| Military | 0 (0%) |

| Program size (mean, SD) | 24 (13) |

| ACGME program pandemic status [N, %] | - |

| Not reported | 1 (5%) |

| Stage 1 | 3 (17%) |

| Stage 2 | 7 (39%) |

| Stage 3 | 7 (39%) |

| Cancellation of elective cases, Yes [N, %] | 18 (100%) |

| Curriculum changes, Yes [N, %] | 17 (95%) |

| Redistributed residents, Yes [N, %] | 6 (33%) |

| Work from home policy, Yes [N, %] | 14 (78%) |

| Policy limiting trainee exposure, Yes [N, %] | 9 (50%) |

Programs reported a significant change in clinical and educational practice due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All 18 programs, at some point in time, had a cancellation of elective surgical cases. The majority implemented work-from-home policies (78%), academic curricular changes (95%), and reduced the exposure of surgical resident trainees during operative interventions (50%) including but not limited to operations, bedside procedures, and endoscopic procedures. Despite attempting to limit trainee exposure, one-third (33%) of participating institutions redistributed residents to cover areas of need including emergency departments and intensive care units (Table 1).

Case volume impact

All residents

Two hundred seventy six thousand four hundred eighty one ACGME case logs were collected from 407 general surgery residents. 139,217 senior resident case logs and 137,264 qualifying junior resident surgical case logs were collected between July 1, 2016 and June 30, 2020. The remaining case logs were the procedures performed by these residents when they progressed to PGY3 or more. Figure 1 demonstrates the time trend of case volume for both junior and senior residents from 2016 through 2020. From 2016 to 2018 total resident case volume for all residents increased each year. In the two academic years preceding the pandemic senior residents performed, on average, 117 more cases than junior residents (95% confidence interval [CI] 96.7-138.2, Fig. 1). Furthermore, preceding the pandemic senior resident case volume increased each year. On average, senior residents performed 38.4 more cases (95% CI 2.9-74.9, Fig. 1) each year while junior resident case volume did not increase (95% CI −13.7 to 22.0; Fig. 1). Both junior and senior residents reported a decrease in case volume during the 2019-2020 academic year compared to the 2018-2019 academic year (P = 0.03; Fig. 1). No other paired differences between any other academic years were statistically significant (P = 0.10-0.99).

Fig. 1.

Total number of cases per resident reported per year between academic years 2016 and 2020 stratified by junior and senior residents. Scatter points represent individual academic years. ∗ P < 0.05.

Senior versus junior residents

Figure 2 shows the aggregated resident case volume from 2016 to 2019, prior to the pandemic, compared to the 2019-2020 academic year during the COVID-19 pandemic. On average, senior residents saw a decrease of 27.8 cases (350.0 versus 307.4, 95% CI 14.9-70.0), accounting for approximately 8.7% of their total case volume. However, junior residents saw a larger impact with respect to their total case volume. Using the 2016-2018 academic years as a comparative historical baseline, junior residents reported on average 23.5 fewer cases (217.3 versus 193.8, 95% CI: 8.0-35.0, P = 0.001) in the 2019-2020 academic year accounting for approximately 11.0% of their total case volume. Evaluating the percentage decrease in case volume associated with COVID-19 pandemic and resident level (senior versus junior resident), junior resident case volume was disproportionately impacted (8.7% versus 11.0%, 95% CI −0.8 to −0.2, P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Total number of cases per resident reported per year between academic years 2016-2019 compared to 2019-2020, stratified by resident level. Scatter points represent individual residents. ∗ P < 0.05.

Comparing postgraduate year 1 and postgraduate year 2 residents

Figure 3 explored the differential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PGY1 and PGY2 residents. When comparing PGY1 residents during the 2019 academic year with the preceding years, PGY1 residents reported on average 19.8 fewer cases (95% CI: 3.7-36.0, P = 0.02; Fig. 3). Similarly, PGY2 residents during the 2019 academic year reported on average 26.7 fewer cases than those in earlier years (95% CI: 7.4-46.0, P = 0.007; Fig. 3). While PGY2 residents saw numerically fewer cases on average than PGY1 residents, this difference between these PGY years was not statistically significant (P = 0.60).

Fig. 3.

Total number of cases per junior resident reported during PGY 1 and PGY 2 across academic years 2016-2019 compared to 2019-2020. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

Figure 4 demonstrates a paired analysis following the same residents from PGY1 into PGY2 prior to and during the pandemic. This figure shows the change in case volume residents experienced in the 2016-2019 academic years versus the 2019-2020 academic year during the pandemic. This analysis followed individual residents over time as opposed to aggregated averages. Each scatter point represents an individual resident’s change in case volume from PGY1 to PGY2. Paired analyses showed, as expected, an increase in cases logged between a resident's PGY1 and PGY2 years (187.4 versus 247.1, P < 0.001). However, this increase in the second year of training was significantly less for residents who entered PGY2 in the 2019-2020 academic years (73.4 versus 34.3 additional cases in PGY2, 95% CI of difference: 16.6-61.8, P < 0.01). This corresponds with 39.2 fewer cases recorded than expected by the PGY2 class during the 2019-2020 academic year (Fig. 4). PGY2 residents during the COVID-19 pandemic saw a smaller increase in cases following their first year than earlier classes.

Fig. 4.

A paired analysis comparing junior resident case volume changes between PGY1 and PGY2 during academic years 2016-2019 and 2019-2020. Scatter points represent individual residents change in case volume between PGY1 and PGY2. ∗∗ P < 0.01.

Junior resident surgical role

Further investigation of the surgical role of junior residents within the operating room during the COVID-19 pandemic was considered, defined by self-reporting of First Assistant or Surgeon Jr as the resident role. There was no difference noted in the observed number of First Assistant cases junior surgical residents reported during the 2019-2020 academic year (34.2 versus 33.1, 95% CI: −4.9 to 7.0, P = 0.73). However, junior surgical residents during the 2019-2020 academic year reported significantly fewer Surgeon Jr cases (186.3 versus 170.0, 95% CI: 1.9 to 30.7, P = 0.02) when compared to the preceding academic years (Fig. 5 ). An effect modification analysis was carried out to analyze the differential impact of COVID-19 on the resident role within the operating room. Although fewer Surgeon Jr cases were recorded during the COVID-19 pandemic, the difference in the change in case volume between resident role groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.08).

Fig. 5.

Total number of Surgeon Jr cases per resident reported per year prior to the COVID-19 pandemic versus during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scatter points represent individual residents. ∗ P < 0.05.

Institutional impact

Program type

At both academic and community-based medical centers, resident case volume has been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. When stratifying by program type, community-based medical centers reported higher case volume than academic medical centers. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic community-based medical centers reported, on average, 50.6 more cases per resident than academic medical centers (246.1 versus 195.5, P < 0.001); this relationship persisted during the COVID-19 pandemic (216.5 versus 180.8, P < 0.01). Community-based medical centers observed on average 29.6 fewer total cases per resident (246.1 versus 216.5, P < 0.01) during the COVID-19 pandemic, while academic medical centers saw a smaller decrease that did not reach statistical significance (195.5 versus 180.8, P = 0.08). Despite numerical differences, the differences in the decrease in case volume between program types did not demonstrate statistically significant differences (P = 0.83; Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Comparison of total number of cases reported by program demographic prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (academic years 2016-2018) and during the COVID-19 pandemic (academic year 2019-2020).

| Parameters | Prior to COVID-19 | During the COVID-19 pandemic | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean total number of cases reported per resident by program type [N, SD] | |||

| Academic medical center | 195.5 (68.8) | 180.8 (74.3) | 0.08 |

| Community-based medical center∗ | 246.1 (92.9) | 216.5 (76.2)∗ | 0.009 |

P < 0.01.

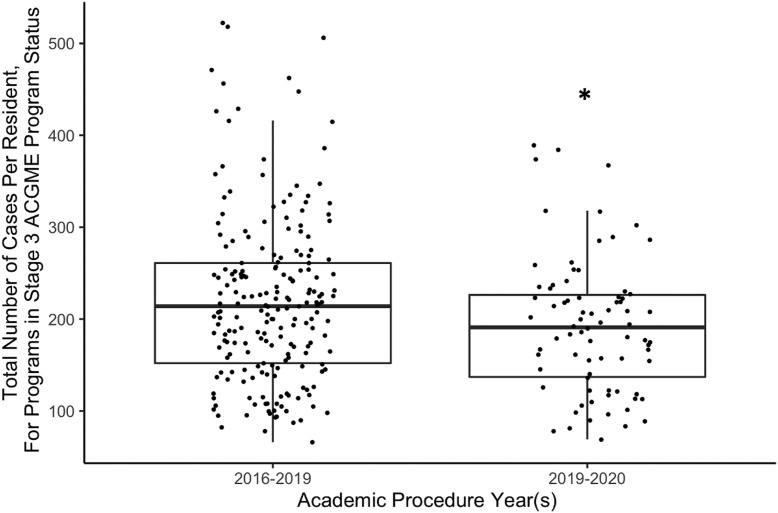

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education program pandemic status

The ACGME Program Pandemic Status reflects the response to the COVID-19 pandemic at the institution level. There was no difference observed in average total cases reported by residents in programs which identified a program status of Stage 1 (214.6 versus 205.2, P = 0.53) or Stage 2 (212.1 versus 194.8, P = 0.18). Programs which reported an ACGME Program Pandemic Status of Stage 3 demonstrated a significant decrease in the average total number of cases reported by residents (219.9 versus 192.5, P = 0.01; Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Total cases per resident, in programs who reported Stage 3 ACGME program pandemic status, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic versus during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scatter points represent individual residents. ∗P < 0.05.

Using a logistic regression analysis, it was determined that institutional reporting of an ACGME Program Pandemic Status of Stage 3 was a positive predictor of the redistribution of residents to the intensive care unit and emergency department (β = 0.40, P = 0.01). However, reporting of Stage 3 Program Pandemic Status was not a good predictor of institutional implementation of either a “work from home” policy (β = −0.22, P = 0.12) or explicit policy limiting the number of surgical trainees in the operating room (i.e., prohibiting double scrubbing; β = 0.10, P = 0.56). Therefore, programs that reported an ACGME Program Pandemic Status of Stage 3 observed the greatest loss in resident case volume and this delineation was a positive predictor of resident redistribution.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in unprecedented changes in clinical practice, leading to nationwide decreases in operative volume.3 , 6 , 8 While a few prior studies have reported on how this operative volume decrease has impacted resident education and training, these studies were primarily survey-based and lack objective data on operative experience at a resident level.5 , 8 , 18 In addition, no studies have investigated the impact on junior surgical residents during the COVID-19 pandemic, despite junior residents being a particularly vulnerable population with limited operative opportunities.14 , 15 To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first multicenter study to quantitatively assess the impact of COVID-19 on junior surgical resident case volume using empiric resident-reported case log data.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, junior residents reported a significant decrease in the total number of cases and limited early exposure to operative autonomy during the COVID-19 pandemic, as compared to those in previous years. Junior resident case volume was also disproportionately impacted, with a larger decrease than senior residents. This finding supports previous literature identifying junior surgical residents as a vulnerable population of surgical trainees.13 , 16 , 17 , 24 , 25 Interestingly, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, senior resident case volume increased each year, whereas junior resident case volume remained stagnant. This investigation corroborates previous reports that while the operative experience and role of senior residents is increasing, junior residents are being left behind.

Importantly, the greatest impact of this decrease on operative case volume came at the expense of junior resident's Surgeon Jr cases. These cases are where early surgical trainees are learning and experiencing a higher degree of autonomy and decision-making for the first time within the operating room.13 , 17 With no difference in the number of First Assistant cases reported during the COVID-19 pandemic, it can be suggested the most direct impact of COVID-19 on junior surgical trainees was in the lost opportunity to assume the role of Surgeon Jr during operative encounters.

Despite the steady increase in case volume over the past 3 y, the COVID-19 pandemic completely eradicated this growth in just 6 mo. A nationwide decrease in case volume this significant has not been appreciated since the implementation of the 80-hour work week.16 , 27 , 28 Furthermore, previous changes to the surgical education paradigm, and now the COVID-19 pandemic, have significantly impacted the junior surgical resident training experience.5 , 24 , 25 While the ABS has temporarily allowed junior surgical residents an extra 6 mo to complete their required 250 cases (previously required prior to beginning PGY3), there are still questions that remain about the sufficiency of this response and the long-term outcomes for surgical residents.29 Specifically, it is difficult to predict how this decrease in case volume will influence surgical proficiency and clinical competency. Thus, subsequent investigations, using resident-level data and quantitative measures, are needed to ensure these trainees achieve the necessary surgical exposure and reach appropriate benchmarks for advancement.

Since the first reported case of COVID-19 in the United States in January 2020, medical institutions across the country have been adapting and innovating the way surgical care is delivered. As is evident by the recommendations of the Center for Disease Control,30 the ACS,31 and the ABS,10, 11, 12 systematic structural changes were instituted at all hospital levels, inherently impacting trainees. Our analysis demonstrates that an ACGME Pandemic Status of Stage 3 was a positive predictor of resident redistribution and was associated with the greatest loss in resident case volume. Therefore, programs that reach an ACGME Pandemic Status of Stage 3 should be especially attentive to the experience and operative exposure of their surgical trainees.

Interpretations from this study should be made with a few limitations in mind. This study represents the early impact of COVID-19 on junior resident case volume during the first 6 mo of the pandemic. While significant decreases in case volume were seen during this time frame, calling attention to the importance of this issue, future studies spanning the entire pandemic are needed for a comprehensive evaluation of this issue. However, it is notable that the impact of COVID-19 in less than one academic semester was sufficient to decrease the overall operative case volume of all surgical residents independent of other factors. Although this study showed that junior residents were disproportionally affected by the decrease in case volume during COVID-19, this does not discount the importance of the impact on senior surgical residents, especially as they near graduation. Also of note, institutional participation in this study was voluntary, and thus carries a potential for selection bias. Finally, this study relied on self-reported resident case log data, which while used for ABS certification and accreditation decisions may not be fully accurate. At this time, there are currently no verified methods for certifying ACGME case logs for accuracy, and the selection criteria used in this study although based on previous studies and clinical experience, admittedly, are subjective.32 , 33 Although participating sites were instructed to remind residents to be up-to-date in their cases logs, there is a system-wide acknowledgment that at times case logs may be deficient.

This investigation is the first multi-center analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on junior surgical resident case volume and operative experience using the ACGME case logs. Given that this investigation included 18 institutions across the United States, in all four regions, both academic medical centers and community-based institutions from both large-sized and small-sized residency programs, its relevance to surgical training programs and junior residents nationwide is notable. This study demonstrated that not only did overall surgical resident case volume decrease but junior resident case volume was disproportionately impacted compared to senior residents and that there were decreased opportunities for junior resident operative autonomy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Decreased operative volume has been associated with increased resident discomfort and difficulty in achieving competency in previous studies.34 , 35 As the pandemic continues, the deficit in case volume may need to be recovered by these residents in the coming years to meet case requirements and attain clinical competency, further exacerbating the “seniorization” of resident education. As the ACGME and ABS incorporate the use of entrustable professional activities in resident competency, programs should emphasize attention to junior surgical residents impacted by this pandemic.36 Careful attention, education intervention, and institutional policies must be implemented to address these concerns moving forward. Future studies are necessary to follow these residents forward and assess the greater impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on resident case volume and operative experience.

Author Contributions

In order of written name, the following 21 authors have contributed meaningful participation in this nationwide investigation to earn authorship claims. The authors being credited on this investigation are Benjamin Kramer (B.K.), Gilman Plitt (G.P.), Judith C. French (J.C.F.), Rachel M. Nygaard (R.N.), Sebastiano Cassaro (S.C.), David A. Edelman (D.E.), Jason S. Lees (J.L.), Andreas H. Meier (A.M.), Amit R.T. Joshi (A.J.), Meredith P. Johnson (M.J.), Jose Chavez (J.C.), William W. Hope (W.H.), Shawna Morrissey (S.M.), Jeffrey M. Gauvin (J.G.), Ruchir Puri (R.P.), Jennifer LaFemina (J.L.), Hae Sung Kang (H.K.), Alan E. Harzman (A.H.), Sahned Jaafar (S.J.), Mathangi Anusha Chandramouli (M.C.), and Jeremy M. Lipman (J.M.L.). B.K., G.P., J.F., and J.M.L. came up with the concept for the investigation and solicited input from multiple institutions regarding study design and execution. R.N., S.C., D.E., J.L., A.M., A.J., M.J., J.C., W.H., S.M., J.G., R.P., J.L., H.K., A.H., S.J., and M.C. all contributed to study design, resident engagement, data processing, editing, and analysis. Each author also executed legal contracts to confirm and collaborate institutional data. B.K. finalized study design, performed advanced statistical analysis, and is the primary author of the manuscript. All authors participated in the drafting, editing, and finalization of the presented manuscript.

Disclosure

None declared.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2022.06.015.

Supplementary Materials

References

- 1.Daodu O., Panda N., Lopushinsky S., Varghese T.K., Jr., Brindle M. COVID-19 - considerations and implications for surgical learners. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e22–e23. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elizabeth Brindle M., Gawande A. Managing COVID-19 in surgical systems. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e1–e2. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nassar A.H., Zern N.K., McIntyre L.K., et al. Emergency restructuring of a general surgery residency program during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: the university of Washington experience. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:624–627. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porpiglia F., Checcucci E., Amparore D., et al. Slowdown of urology residents' learning curve during the COVID-19 emergency. BJU Int. 2020;125:E15–E17. doi: 10.1111/bju.15076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Purdy A.C., De Virgilio C., Kaji A.H., et al. Factors associated with general surgery residents’ operative experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:767–774. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lancaster E.M., Sosa J.A., Sammann A., et al. Rapid response of an academic surgical department to the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for patients, surgeons, and the community. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:1064–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Negopdiev D., Collaborative C., Hoste E. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1440–1449. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aziz H., James T., Remulla D., et al. Effect of COVID-19 on surgical training across the United States: a national survey of general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2020;78:431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surgeons ACo COVID-19: recommendations for management of elective surgical procedures 2020. 2020. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case Available at:

- 10.American Board of Surgery Modifications to training requirements. March 26, 2020. 2020. http://www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?news_covid19_trainingreq Available at:

- 11.American Board of Surgery ABS statement on training requirements during COVID-19. 3/19/2020. 2020. http://www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?news_covid19_training Available at:

- 12.American Board of Surgery FAQs - hardship modifications to general surgery training requirements. 2020. http://www.absurgery.org/default.jsp?faq_gshardship Available at:

- 13.Mullen M.G., Salerno E.P., Michaels A.D., et al. Declining operative experience for junior-level residents: is this an unintended consequence of minimally invasive surgery? J Surg Educ. 2016;73:609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cairo S.B., Craig W., Gutheil C., et al. Quantitative analysis of surgical residency reform: using case-logs to evaluate resident experience. J Surg Educ. 2019;76:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cortez A.R., Katsaros G.D., Dhar V.K., et al. Narrowing of the surgical resident operative experience: a 27-year analysis of national ACGME case logs. Surgery. 2018;164:577–582. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamine T.H., Gondek S., Kent T.S. Decrease in junior resident case volume after 2011 ACGME work hours. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:e59–e63. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dacey R.G., Jr., Nasca T.J. Seniorization of tasks in the academic medical center: a worrisome trend. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;228:299–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ellison E.C., Spanknebel K., Stain S.C., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical training and learner well-being: report of a survey of general surgery and other surgical specialty educators. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231:613–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.08.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Education ACfGM. Defined Category Minimum Numbers for General Surgery Residents and Credit Role 2019. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/definedcategoryminimumnumbersforgeneralsurgeryresidentsandcreditrole.pdf.

- 20.Accreditation Council for graduate medical education three stages of GME during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://acgme.org/COVID-19/-Archived-Three-Stages-of-GME-During-the-COVID-19-Pandemic Available at:

- 21.Potts J.R., 3rd. Residency and fellowship program accreditation: effects of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:1094–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuhrman G.M., Orr R., Dunn E., et al. An assessment of university versus independent general surgery program graduate performance on the American Board of Surgery examinations. J Surg Educ. 2007;64:346–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in general surgery. 2019. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/440_GeneralSurgery_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-22-085958-260 Available at:

- 24.Hutter M.M., Kellogg K.C., Ferguson C.M., Abbott W.M., Warshaw A.L. The impact of the 80-hour resident workweek on surgical residents and attending surgeons. Ann Surg. 2006;243:864–871. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000220042.48310.66. discussion 871-865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larson K.E., Grobmyer S.R., Reschke M.A.B., Valente S.A. Fifteen-year decrease in general surgery resident breast operative experience: are we training proficient breast surgeons? J Surg Educ. 2018;75:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.R Development Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2010. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.https://www.R-project.org Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferguson C.M., Kellogg K.C., Hutter M.M., Warshaw A.L. Effect of work-hour reforms on operative case volume of surgical residents. Curr Surg. 2005;62:535–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kairys J.C., McGuire K., Crawford A.G., Yeo C.J. Cumulative operative experience is decreasing during general surgery residency: a worrisome trend for surgical trainees? J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:804–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potts J.R., III, Lipsett P.A., Matthews J.B. The challenges of program accreditation decisions in 2021 for the ACMGE review committee for surgery. J Surg Educ. 2020;78:394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rusch V.W., Wexner S.D., American College of Surgeons Covid-19 Communications Committee BoR, Officers The American College of surgeons responds to COVID-19. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231:490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naik N.D., Abbott E.F., Aho J.M., et al. The ACGME case log system may not accurately represent operative experience among general surgery interns. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:e106–e110. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strosberg D.S., Quinn K.M., Abdel-Misih S.R., Harzman A.E. An analysis of operative experiences of junior general surgical residents and correlation with the SCORE curriculum. J Surg Educ. 2016;73:e9–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suwanabol P.A., McDonald R., Foley E., Weber S.M. Is surgical resident comfort level associated with experience? J Surg Res. 2009;156:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams R.G., Swanson D.B., Fryer J.P., et al. How many observations are needed to assess a surgical trainee's state of operative competency? Ann Surg. 2019;269:377–382. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner J.P., Lewis C.E., Tillou A., et al. Use of entrustable professional activities in the assessment of surgical resident competency. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:335–343. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.