1. Introduction

Covid-19 is a pandemic that started towards the end of 2019 and spread quickly (Ivanov, 2020). To this end, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified the outbreak of Covid-19 as a worldwide pandemic leading to quarantine, social distancing, border closure, and the prolonged closure of vital facilities (Ivanov and Dolgui, 2020). This impacted the global economy, social mobility, and health on a global scale (OECD, 2020). Specifically, the Covid-19 outbreak led to misalignment between supply and demand by affecting supply chain nodes to different extents (Araz et al., 2020). For example, it was reported that restrictions limited ports’ services, which led to port call cancellation, delays, and congestion on both hinterland and maritime sides (UNESCAP, 2020).

That being said, interconnected and nested logistics services have remained active through such uncertain events (UNCTAD, 2020a). Decision-makers need to cope with the challenge of keeping the balances between safety, security, sustainability, and performance of their systems considering resources, against a variety of strategic, tactical, and operational risks leading to system failure (John et al., 2014). This exhibits urgent demands for resilience-based decision-making which requires a thorough understanding of situations to plan and prepare for potential threats (Golan et al., 2020). In fact, this is nothing new. Since the beginning of this century, the world has undergone unfolded challenges because of climate change, epidemics, geopolitics, terrorism, economic uncertainties, as well as regional conflicts and rivalries. Such complexities pose threats to the appropriate use of critical infrastructures (CIs) that are crucial for societal well-being (Z. Yang et al., 2018). All these make them a serious concern for planners and operators (Rehak et al., 2019): such systems must be designed to be sufficiently resilient and capable of recovering quickly from disruptions. Here Haimes et al. (2008) and Zolli and Healy (2012) criticized past research's inadequacy to propose effective ways to significantly improve the resilience of the socio-economic systems, where such a view has recently been reiterated by Ivanov and Dolgui (2020). Consequently, research relevant to resilience and risk management has received considerable attention in recent years (Ullah et al., 2019), as it could decrease possible socio-economic losses and allow decision-makers to make better moves in the face of challenges (Mitchell, 2013).

In this regard, resilience can be understood as the ability of an entity or system to bounce back to a normal condition after its original state is affected by a disruptive event (Wan et al., 2017). Among the CIs, ports generate and sustain economic activities by offering various logistical services, and their attractiveness is vital to the competitiveness of logistics and supply chains (Ng, 2006). Also, being the focal point of global trade, logistics, and supply chains (Ng and Liu, 2014), they are responsible for more than 80% of the global freight movement (UNCTAD, 2020b). Thus the disruption of even a single element in a port could have a significant cascading effect, causing severe imbalances across the entire delivery service network, causing substantial direct and indirect financial losses. Hence, it is important to investigate port performance in tackling disruption through the lens of resilience.

Stemming from human behavior and psychology, resilience is not something new (Chapin et al., 2009). The idea initially appeared in the ecological environmental systems (Holling, 1973) on individuals' ability to face pressure and recover quickly from disruptive incidents (Van Der Vegt et al., 2015). This could be found in its early definitions, notably the continuity of associations within a system and a certain degree of ability to absorb and proceed with absorbing changes (Holling, 1973). In this regard, Labaka et al. (2015) argued that despite extensive research, resilience has various definitions. For example, it has been described as a system's capability for developing foresight, recognition, anticipation, and defense against changing risks before detrimental effects occur (Starbuck and Farjoun, 2005). Some scholars describe resilience as the system's capability to sustain a significant disruption and overcome it within a reasonable time and cost (e.g., Haimes et al. (2008)). Also, it has been referred to as preparing and adapting to changing environments and enduring and recovering quickly from disruptions (House, 2013). Part of such differences in the definition is based on the context in which they are applied (e.g., economic systems, education systems, health care systems, ecosystems, CIs) (Southwick et al., 2014). This explains why some researchers have tried to suggest a multidisciplinary definition for resilience (Clauss et al., 2020). That said, the majority of works in the context of CIs addresses the system's vulnerability, where there is limited attention to capacities and interrelations (Hosseini and Barker, 2016).

A resilient infrastructure relies on its ability to absorb, adjust, predict, and quickly overcome a possibly disruptive incident (NIAC, 2009). Here we highlight the fundamental features of a resilient system based on the definition by the US National Research Council (NRC), namely ‘the capability of the system to plan and prepare for, absorb, overcome with, and fit with real or possible disruptions’ (National Research Council, 2012). The definition has two key components: (1) risks decreasing the system's performance (i.e., actual or possible disruptions), and (2) resilience-building capacities resisting system's performance changes and returning it to a new normal (i.e., absorption, recovery, and adaptation/transformation capacities of the system). Later, it was followed by national directives (e.g., PPD (2021)) and explored by many research (e.g., Ramirez-Marquez (2012), Ayyub (2014), and Linkov et al. (2014)), and widely applied in recent research (e.g., Petersen et al. (2020); Doorn et al. (2019); Pescaroli and Needham-Bennett (2021)). As Ayyub (2014) has discussed, such a definition has certain characteristics that make it suitable for practical applications, including the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on port resilience.

Understanding such, in this study, we develop a Bayesian Belief Network (BBN) model to quantify the port system's resilience in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic. As a tool frequently used in supporting decision-making, BBN handles complexities and uncertainties by spotting disruptive factors, resilience-building capacities, and their interactions (Djalante et al., 2020). The model is then used to model the resilience of the port of Hong Kong's Kwai Tsing Container Terminals (KTCT). In this case, the key contributions of this study are as follows:

-

•

Identify port disruptions during a pandemic outbreak, including their cascading effects.

-

•

Investigate port resilience-building capacities in the face of a pandemic outbreak.

-

•

Develop an extendable model to quantify and assess the port's resilience considering various disruptions raised by a pandemic and resilience-building capacities based on the BBN.

-

•

Analyze the resilience of ports.

The rest of the paper is as follows. Section 2 consists of the research background, including the literature reviews. Section 3 discusses the framework to develop the model. Section 4 briefly introduces BBN as the analytical tool implemented to build the model based on the introduced framework. Section 5, 6 explains the research process, including data collection. Finally, the results are represented and concluded in Sections 7 and 8, respectively.

2. Research background

The key literatures regarding risk and resilience assessment of pandemic impacts are mainly associated with the effects of a pandemic on seaport transportation and the maritime supply chain. Similarly, the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic have mainly been considered the seaborne trade (e.g., Chua et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2021a), port and sea transport (e.g., Mack et al., 2021; Narasimha et al., 2021), and supply chains (e.g., Lahyani et al., 2021; Lopes et al., 2022; Ozdemir et al., 2022). In this case, ports have experienced significant changes to normal operating environments due to the Covid-19 pandemic (UNCTAD, 2022). Addressing the current and potential future challenges inspired researchers and practitioners to rethink strategic resilience in the ‘port’ context. Different natural and human-made disturbances, local or regional, have been widely discussed in the pieces of literature. However, pandemic disruptions, with their global impact and long-lasting effect, have been neglected. As such, it is pivotal to identify the key factors that affect port CIs during the Covid-19 pandemic (Gui et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2021b) and to build a BBN framework to quantify resilience and examine the impacts of different factors in port performance. Here we explore two key questions: 1) How is resilience developed in the context of the port industry? 2) How is BBN implemented in this context? To answer them, we focus on research conducted after 2010 where the port was the focus. For example, we do not cover those studies that analyze the resilience of maritime transport or maritime supply chain where the port is just one (not key) element.

Since CIs are exposed to different natural (e.g., hurricanes, tornados, tsunamis, floods, typhoons, volcanic eruptions, earthquakes) and man-made (e.g., pandemic and terrorist attacks) hazards at an unpredictable frequency, intensity, and scale, such systems should be designed in efficient and resilient ways (Djalante et al., 2020). In the meantime, quantifying the impact of threats on CIs performance is far from straightforward (Shafieezadeh and Burden, 2014). That said, considerable research related on port risk management and resilience has been conducted in the past decades. Unsurprisingly, researchers adopted different approaches to identify and assess resilience (Sun et al., 2020). For example, Mansouri et al. (2010) produced the framework of risk management-based decision analysis to investigate port facility resilience based on common fundamental elements of resilience in port infrastructure systems using Decision Tree Analysis (DTA). This helped decision-makers to develop mitigation strategies, contingency plans, and systems for controlling and overseeing potential threats and risk elements; and evaluate the resilience investment plans and strategies that have been adopted. Galbusera et al. (2018) proposed a robust Boolean network approach to examine the resilience of mutual infrastructure, including alleviation factors, allocation plans, and resource constraints. Therefore, fragility, restoration, recovery urgencies, and buffering abilities of provided seismic scenarios were operated to analyze the resilience of CIs in the port of Thessaloniki, Greece. Pitilakis et al. (2019) employed a risk-based method with four pre-assessment, assessment, decision, and report phases for stress assessing critical infrastructures exposed to seismic, geotechnical, and tsunami hazards. Argyroudis et al. (2020) established a resilient CI framework that revealed risks by considering the assets' vulnerability to hazards, the pace of damage recovery, and the hazards’ temporal volatility. The proposed framework that consisted of a an asset resilience index for the complete, incomplete, or no revamp of asset damage between the succeeding hazard conditions was applied to a highway bridge revealing the significant influence of the existence time of the second hazard on the resilience index and a substantial mistake by adopting easy imposition of resilience indices from various types of perils.

In addition, considering uncertainty in assessing the resilience of infrastructure systems is crucial. Shafieezadeh and Burden (2014) developed a framework for scenario-based resilience assessment of CIs that reflected the uncertainties of the process, the interrelationship of fragility evaluation of structural elements, the degree of earthquake intensity, the repair process, specifications, and service demands against seismic events. Hseih et al. (2014) evaluated port vulnerability from an interdependency viewpoint through orderly approaches containing sensitivity models and fuzzy cognitive maps to foster practitioner's comprehension of the interrelationship of various subsystems of port infrastructure and the cascading impact of the port vulnerability. Trepte and Rice (2014) investigated the US port system to forecast its capability to tackle cargo concentration disruptions. The study was undertaken by addressing the total volume and product categories that ports take in as a starting point and, following that, assess the required capacity to compete with neighboring ports for different types of products. These stated studies have set a concrete baseline to construct a framework for examining the resilience of ports in face of a pandemic. However, more specific research on this area is required.

3. Resilience assessment framework

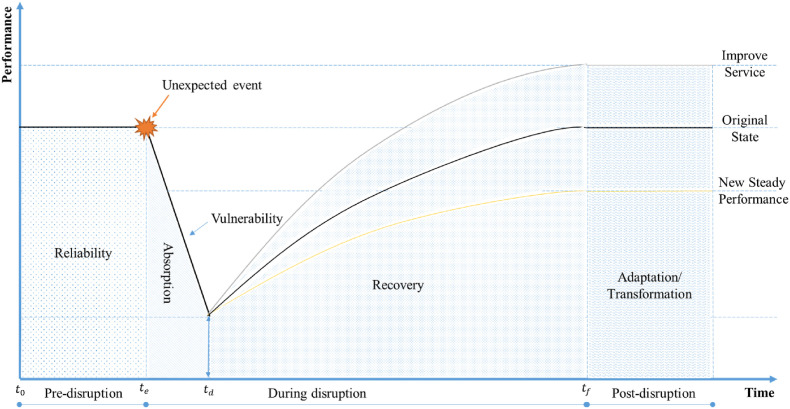

Fig. 1 demonstrates the performance of a system and how resilience-building capacities and disruption interact over time. Although performance is affected by different factors (e.g., aging of port infrastructure), such elements are not included in the pre-disruption period. The trough in the performance curve reflects part of the system's resilience in face of disruptions. Within the time interval of the system operates normally, then with disruption occurrence, the performance reduces until . Absorptive capacity refers to the degree that the system can absorb the impact of shocks caused by disruptions and minimize consequences. This is the robustness and reliability to mitigate adverse effects of the disturbance (Golan et al., 2020; Rehak et al., 2018; Setola et al., 2016).

Fig. 1.

Schematic demonstration of resilience phases (modified based on Henry and Ramirez-Marquez (2012) and Linkov et al. (2014)).

Recovery capacity enhances the serviceability during the disruption gradually until . This is the system's capability to recover its major functions effectively to the original state or a new (steady) performance level. Successful recovery includes actions that are dictated by available resources. The process usually takes longer than what it experiences in absorption (Linkov et al., 2014; Rehak et al., 2018; Vugrin et al., 2011). It might reach its original state, improve its service, or reach a lower steady-state performance level. Over this long period, the Adaptive/Transformative capacity could support performance stability and enhancement. This indicates the system's ability to learn from disruptive events and adapt to the possible recurrence of disruptions in the aftermath. By predicting and recognizing disruptive events, the infrastructure gains long-lasting preparedness for future disruptions by strengthening its resilience (Rehak et al., 2018; Setola et al., 2016). The hatched area around in Fig. 1 emphasizes the importance of considering adaptive/transformative capacities while devising recovery capacities and allocating resources. This could critically determine the final state of the system's performance.

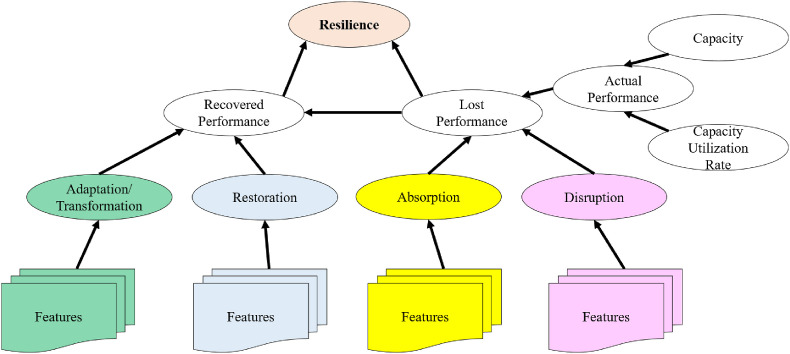

That said, the lost performance (LP) of a port is the reduction in performance of the port due to an unexpected event (e.g., disruption, which depends on its absorptive capacity). In other words, the system's absorptive capacity responds to the shock and determines to what extent it might lose performance. Recovered performance (RP) (i.e., the increase in the system's performance after its reduction) depends on the recovery and adaptive/transformative capacities in response to the LP. Fig. 2 shows the developed resilience assessment framework based on these definitions and used in similar research (e.g., Francis and Bekera (2014); Shen and Tang (2015)). Among various metrics used to assess port infrastructure's resilience, the metric used in this study measures the resilience as the ratio of RP to LP (Henry and Ramirez-Marquez, 2012).

Fig. 2.

Schematic view of the resilience assessment framework

(Source: Authors).

4. Bayesian Belief Network (BBN)

The BBN has a wide range of applications in the fields of risk assessment for decision-making under uncertainty and risk, and resilience engineering. This is due to its analytical power that can be used for decision-making under uncertainty and model both qualitative and quantitative variables (Hossain et al., 2019a; Patriarca et al., 2018). It is often adopted as a decision support tool for different types of risk assessment and resilience strategy development as it builds a cause and effect diagram simply (Lee et al., 2009), such as risk analysis (Goerlandt and Montewka, 2015; Lawrence et al., 2020; Montewka et al., 2014; Panahi et al., 2020; Song et al., 2013; Trucco et al., 2008; Xue and Xiang, 2020; Yang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2013), reliability engineering (Cai et al., 2019; Hänninen, 2014; Mahdi et al., 2018; Norrington et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008, 2013, 2018; Zhisen Yang et al., 2018; Zhang and Thai, 2016), safety modeling (Convertino and Valverde, 2018; Hänninen et al., 2014; Mahdi et al., 2018), sustainability analysis (Awad-Núñez et al., 2016, 2015), resilience assessment (Alyami et al., 2014; Hossain et al., 2019a; 2020; Hosseini and Barker, 2016; John et al., 2016), to name but a few. An overview of utilizing BN for risk and resilience assessment of CIs, like ports, is presented here: Hosseini and Barker (2016) implemented a BBN model infrastructure resilience of an inland waterway port and quantified resilience as a task of restorative, absorptive, and flexible abilities. Also, Hossain et al. (2019b) proposed a metric for port performance to evaluate inland port efficiency based on six parameters, namely 1) facility, 2) availability, 3) economy, 4) service, 5) connectivity, and 6) environment. They captured both quantitative and qualitative factors to rank the impact of the criteria based on a port performance index. Later, Hossain et al. (2020) proposed a model for assessing geographical, service provision interdependencies between an inland port infrastructure and its neighboring supply chain to demonstrate the negative impacts of disruptions on the whole infrastructure's performance. The studies suggest that BBN is a highly useful tool for dealing with uncertain situations and inferring knowledge to support timely decisions.

4.1. The BBN theory

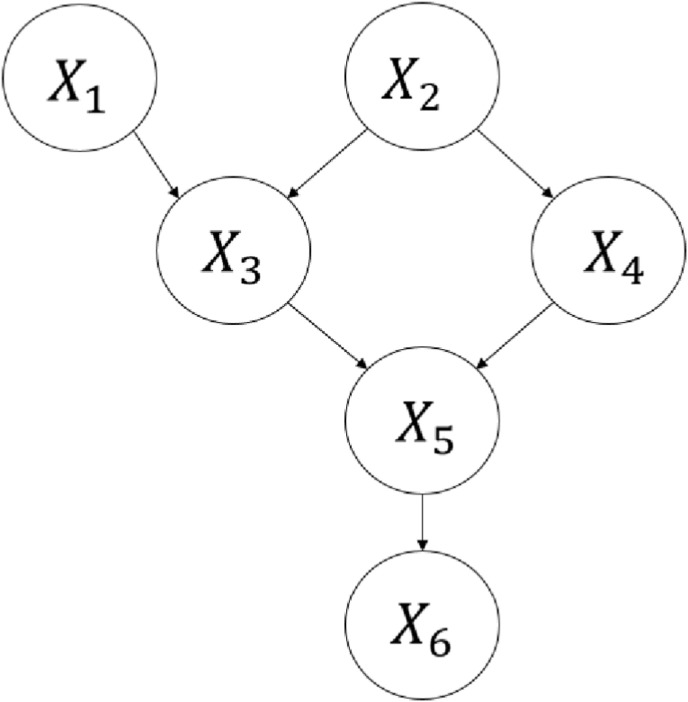

Constructed on the Bayes theorem, BBN is a probabilistic structure of Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAG), in which nodes represent the variables of the structure, and connections – pointing from parent to child nodes – represent the dependency or causal relationship between such nodes. Here, root nodes – those without a parent node – are quantified with a prior probability. The conditional probability is then used for child nodes, represented as Conditional Probability Tables (CPTs). Conditional probabilities reflect causal relationships among variables of a BBN. Then, the joint probability is written based on the probability of event Y occurring (child node) when event X (parent node) occurs. For a random number of variables , and a DAG with nodes, for which node is associated with the variable , the following represents the fundamental mathematical expression of the BBN:

| (1) |

To elaborate Eq. (1), a sample DAG with six nodes is represented in Fig. 3 . Here, the joint probability distribution of the BBN is given by:

| (2) |

Fig. 3.

An example of Bayesian Belief Network (BBN) with six nodes

(Source: Authors).

4.2. BBN quantification

For such a network, variables (nodes) should be quantified according to their type. For Boolean variables (e.g., True/False), the False state describes as the negative result while the True state identifies as the positive result (Fenton and Neil, 2013). For all those up to three parent nodes (i.e., zero, one, two, or three) experts were asked to directly determine the probability of each scenario, i.e., 23 scenarios assuming two states (e.g., True and False) for each node. Here we benefited from the weighting technique for those with more than three parent nodes, considering the level of complexity, i.e., more than 16 scenarios assuming two states (e.g., True and False) for each node. To determine the weight of features incorporated into a parent node, expert judgment was used by applying the Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP) based on pair-wise comparisons of such features (Tseng and Cullinane, 2018). To achieve this, we asked participants to determine the relative weight of parent nodes, and later we combined them with their probability to determine the probability of each scenario for the child node.

NoisyOR functions were used to determine Boolean variables as we preferred to quantify the effect of each causal factor on its parent node independently of considering all possible combinations of states of the other parents. The NoisyOR function simplifies the elicitation of complex conditional probability tables and soothes the presumption that a factor can be reported as a "True" state only when a parent is also in the "True" status (Kyburg and Pearl, 1991; Perreault et al., 2016). This is demonstrated by introducing the 'leak' factor which suggests that there are other unknown parent variables (nodes). By doing so, the assessment would become more realistic. To comprehend the operational concept of NoisyOR, we assume that there is a set of n causal factors, of a condition, Y. Likelihood of Y is being True once only one causal factor, is true, and all other reasons other than are False. The NoisyOR purpose is characterized by Eq. (3) where for each i, is the chances of the condition being True if and only if that causal factor is True (Fenton and Neil, 2013).

| (3) |

Leak factor, l, is a non-zero possibility of the effects that would be created, even though all causes are false. l represents the probability that Y will be True even if all its causal variables are false. So, the provisional likelihood of Y gained by the NoisyOR function is presented below:

| (4) |

To further clarify, we specified a value (between 0 and 1) for each causal factor to use the NoisyOR function. This value captured the probability that the consequence would be true in case of this cause is true. For example, if there is a 24% chance of port closure would cause a delay effect on the landside, the value associated with the cause of port closure would be 0.24. Then, the study identified all the values (one for each of the causes). Also, it is required to indicate an additional value, called the ‘leak value’ to, for example, 0.1, which would be the probability of a landside delay if all risk factors were absent. In other words, the leak factor represents causes of landside delay that are excluded in the model.

The posterior probability distribution of disruption and resilience-building capacity nodes are specified by their parent nodes’ weighted sum of probabilities. The weight of each factor shows its importance. In the following equation, the weighted mean (WMEAN) function is represented, where is the number of variables immediately associated with o the weighted average node (capacity node), and indicates the weight of th variable:

| (5) |

For continuous variables, historical data usually determines all the past allocations of the continuous variable. Through the adoption of a truncated normal distribution (TNORM), continuous variables are modelled accordingly (Fenton and Neil, 2013). Equation nodes can consider continuous values rather than a provisional probability distribution table. As such, it explains the key relationship of a discrete node with its parents (Bayes Fusion, 2020).

4.3. End nodes: resilience and performance

Disruptions lead to LP, which is highly dependent on absorptive capacity. Thus, the LP is set to zero when a port does not lose its performance, and the disruptions are absorbed. As per Table 1 , the Node Probability Table (NPT) for lost performance is adopted on three main variables, namely the probability of disruption occurrence (LDO), absorption, and actual performance (AP). The LP is calculated as a product of the probability of disruption occurrence (PDO) and AP if absorptive capacity fails to take in the shock caused by disruptions. AP is the product of the rate of capacity deployment and expected performance. A port's utilization rate (UR) during regular operation is obtained from historical data that vary between 0.8 and 1.0.

Table 1.

Node probability table (NPT) for lost performance (LP)(

Source: Authors).

| Absorptive Capacity | False | True |

|---|---|---|

| Expression | 0 |

In this case, RP is a function of three variables, namely recovery and adaptive/transformative capacities, and LP. Here we assume that, if recovery and adaptive/transformative capacities perform successfully, a port's CIs would improve the UR of its LP (i.e., zero). Table 2 illustrates the NPT for RP.

Table 2.

Node probability table (NPT) for recovered performance (RP)(

Source: Authors).

| Recovery and Adaptive/Transformative Capacities | False | True |

|---|---|---|

| Expression | 0 |

5. Research process

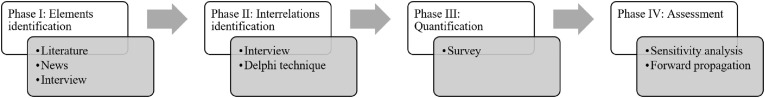

The research process can be found in Fig. 4 .

Fig. 4.

The research process

(Source: Authors).

It is divided into four main phases (I, II, III, and IV), as follows:

-

I.

Identification of resilience elements: We gathered a comprehensive list of the risks (disruptive factors) (i.e., factors adversely affecting port performance in the face of the pandemic) and resilience-building capacities (i.e., absorption, recovery, and adaptation/transformation capacities). This was performed concerning the literatures, the latest news and reports by international organizations, and experts' input extracted through semi-structured interviews (see Section 6).

-

II.

Building the resilience assessment model: We extracted the relationships between disruptive factors and those of identified capacities to build the system's model, based on the resilience assessment framework (see Section 3). In doing so, literature and inputs from the first phase were implemented. Later, the network was verified by circulating the outcome among experts who attended the first phase.

-

III.

Model quantification: We determined the (conditional) probability of the model nodes. In doing so, we investigated the port of Hong Kong, China and benefited from its historical data.

-

IV.

Resilience assessment: The total resilience of the studied port was measured based on the model outcome. Also, different techniques were used to shed light on the most important resilience-building capacities.

6. Study area and data collection

To develop the model and analyze ports in face of a pandemic (phases I and II), we obtained experts' inputs through conducting 28 semi-structured interviews with appropriate professionals who worked as container terminal operators and port authorities for at least ten years in Canada, China, the Netherlands, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). In addition to the availability of appropriate interviewees, by the time when this study took place, these countries also hosted many of the world's largest ports and terminals. In this case, information extracted from the latest news and reports by international organizations (see Section 5) was helpful in helping us to raise the right questions and obtained highly useful information. Specifically, we asked them questions that were closely related to the identification of resilience factors (Phase I) and their connections (Phase II). Table 3 provides detailed information on the interviewees' profiles.

Table 3.

The profiles of interviewees

(Source: Authors).

| Characteristic | Range | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Job title/Position | President/Director | 5 |

| Senior deputy director | 6 | |

| Division director | 7 | |

| Supervisor | 4 | |

| Senior engineer | 6 | |

| Age range | Under 40 | 5 |

| 40–50 | 8 | |

| 51–60 | 13 | |

| Above 60 | 2 | |

| Education background | Bachelor | 13 |

| Master | 12 | |

| Doctoral | 3 | |

| Years of experience in the industry | 10–15 | 4 |

| 16–20 | 6 | |

| 21–25 | 3 | |

| Above 25 | 5 | |

| Location | Canada | 4 |

| China | 14 | |

| Netherlands | 5 | |

| United Arab Emirate | 5 |

After developing the model with a table representing all the definitions, we circulated the outcomes among interviewees, benefiting from the Delphi technique. After three rounds of circulations, we have reached a full consensus among the study participants on resilience factors and their interrelations. For details, see Appendix A.

To conduct Phases III and IV, we applied the developed model on Kwai Chung and Tsing Yi Container Terminals (KTCT) in the port of Hong Kong, China. Located in southern China and renowned for its high efficiency, KTCT contributes an annual container-handling capacity of more than 20 million Twenty-Foot Equivalent Units (TEUs) by nine container terminals operated by five different operators, namely Modern Terminals Ltd. (MTL), Hongkong International Terminals Ltd (HIT), COSCO-HIT Terminals (Hong Kong) Ltd. (CHT), Goodman DP World Hong Kong Ltd., and Asia Container Terminals Ltd (ACT). As confirmed by several interviewees, keeping the port and its terminals open was extremely important even during the difficult periods (e.g., a pandemic), understanding its pivotal roles in sustaining the daily lives of all the city of Hong Kong's residents, bringing in vital commodities, not least food, medical supplies, and other basic necessities.

To quantify the model, we reached out to 13 senior managers, all with more than at least ten years of experience in KTCT's operation. Among them, three attended the first series of the stated interviews (see above). During the meetings, we explained the whole process and represented the developed model to the rest of the team. To simplify the process, we assumed only two states for all the nodes, namely "True" and "False". That said, we asked them to determine the probability of each state or scenario for all the nodes with up to three parent nodes (i.e., zero, one, two, and three). For those with more than three parent nodes, we asked them to determine the relative weight of each parent node (i.e., the contribution of the parent node to the child node, see Section 4.2).

7. Results and discussion

7.1. Model and quantification

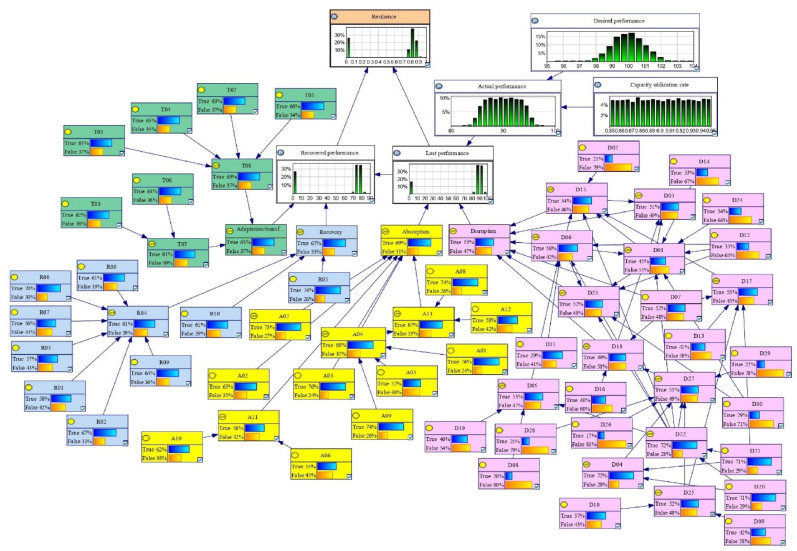

After Phases I and II have been completed, we obtained a general model to measure the resilience of the port. It includes 30, 13, ten, and eight nodes under disruption, absorption, recovery, and adaptation/transformation elements, respectively. Besides, the interplay among such nodes is simulated through 93 connections. After gathering the data (Phase III),1 we quantified the model, measured its resilience, and identified critical factors (Phase IV). With the assistance of the GeNIe software, the resilience assessment model for KTCT can be found in Fig. 5 .

Fig. 5.

The resilience assessment model of Kwai Chung and Tsing Yi Container Terminals (KTCT) (Remarks: (pink): disruptions, (yellow): absorption capacity, (blue): recovery capacity, (green): adaptation/transformation capacity) (Source: Authors).

The disruption node with two main states (i.e., True = 53% and False = 47%) suggests a 53% chance that KTCT's disruption would occur and adversely affect its resilience. On the other hand, there is a 47% possibility that the disruption would not happen. Considering the states for the absorption node, the system is 69% successful in absorbing shocks of disruptions based on its absorption capacity. This is 67% and 63% for recovery adaptation/transformation capacities, respectively. The overall resilience of KTCT is 83%. In this case, it is important to understand the contribution of variables in building the system's resilience, so that port and terminal decision-makers can effectively plan for the future by prioritizing their current actions. This can be done through sensitivity analysis (SA) and scenario analyses.

7.2. Sensitivity analysis (SA)

SA is a useful technique to validate the structure of the BN model (Hossain et al., 2019b; Lawrence et al., 2020) by examining the impact of the contributors in the target node within the same model. Indeed, it is a widely accepted method to identify which node has a further influence on its associated node. As such, SA examines the relative value of the independent variable(s) for a specific set of conditions on a particular dependent variable (Borgonovo and Plischke, 2016). This possesses certain advantages over other techniques, such as an in-depth study of all the variables allowing decision-makers to identify what and where they can make improvements, whether the origin of the inference is rational, and what an incremental effect might impact the modelled results.

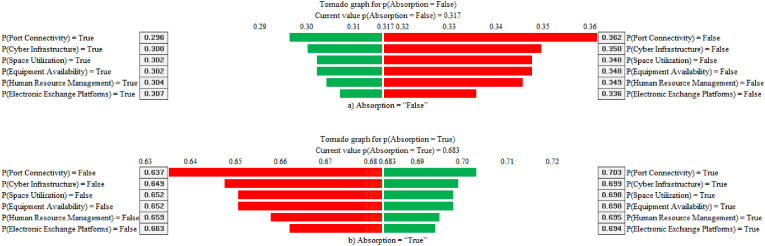

Here we used GeNIe to acquire more insight into the model and better understand how the parent nodes influence the child nodes of the underlying BBN structure. The impact of the absorption capacity's causal factors is analyzed by setting absorption as a target node. As an illustrative example, Fig. 6 shows the sensitivity analysis for absorption. The range of the bars related to every sensitivity node demonstrates a measure of the influence on the corresponding node's absorption capacity. Fig. 6(a) shows the impact of the parent nodes of absorption capacity on it when this capacity exists as “False”, while Fig. 6(b) illustrates the influences of those variables once the capacity acts as “True”. We did both analyses to check the impact of variables when absorption was “True” or “False”. By doing so, we found that port connectivity performed the maximum impact while electronic exchange platforms exhibited the minimum impact on absorptive capacity. Despite the wide impactful range of port connectivity from 0.637 to 0.703, the electronic exchange platform's impact was bounded to a restricted range between 0.663 and 0.694. This suggests that the enhancement of connectivity within the port system would create the largest effect of increasing the port's absorptive capacity. In contrast, improvement in the electronic exchange platforms would not have a significant impact on the port infrastructure's absorption capacity.

Fig. 6.

Sensitivity analysis for absorption

(Source: Authors).

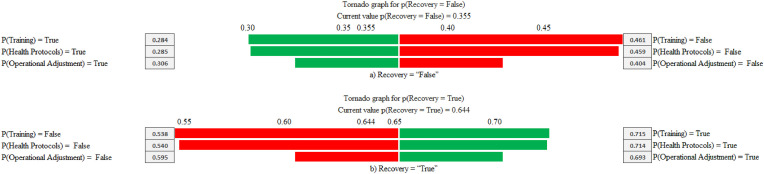

Fig. 7 provides the SA of the recovery capacity.

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity analysis for recovery

(Source: Authors).

Based on this, training exhibited the maximum effect, while operational adjustment had the minimal effect on enhancing the recovery process of port infrastructure. The probability of recovery presented the results of training shifts from 0.538 (on the condition that it is “False”) to 0.715 (providing that it is “True = On”); furthermore, the influence of operational adjustment is bounded to a restricted range, between 0.595 and 0.693. The SA of adaptation/transformation can be found in Fig. 8 .

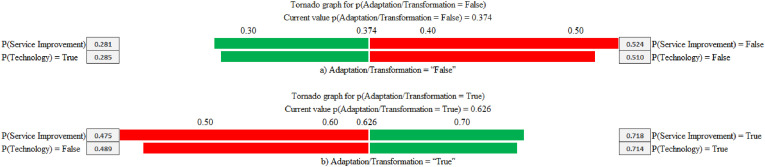

Fig. 8.

Sensitivity analysis for adaptation/transformation

(Source: Authors).

Fig. 8 depicts that both service improvement and technology have a considerable influence on improving adaptation to new conditions. According to Fig. 8(b), the chance of adaptation generated by the outcomes of service improvement shifts from 0.475 (on the condition that it is “False”) to 0.718 (in case that it is “True”); the result of technology moves from 0.489 to 0.714. Hence, we found that improving service improvement and technology would lead to better adaptation to new circumstances.

Based on the SA, port connectivity, training, and service improvement are considered the main factors playing a part in enhancing the port infrastructure's resilience. These results are consistent with the real-world scenarios, as port hinterland and maritime connectivity are among the top priorities for the port managers. During its early stage, Covid-19 has severely affected port calls and liner shipping connectivity levels. The lockdowns in major ports have had heavily impacted liner shipping connectivity (UNCTAD, 2020c). Also, the hinterland connectivity impact on ports' resilience was highlighted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Health policies and robust measures are required to prevent virus transmission in the recovery phase, whether on ships or ports of call worldwide. It is crucial to respond in a quick and determined way to keep the port operational, emphasizing the port community's health and safety. In the absence of urgent actions, the post-pandemic recovery would be severely affected, potentially weakening long-term sustainability. Indeed, the Covid-19 pandemic can be a significant driver for adopting emerging industrial 4.0 technologies, such as drones, AI-based surveillance, blockchain, digital twins, autonomous freight, Internet of Things (IoT), and real-time dashboards. Strengthening digitalization and eliminating paperwork in the maritime industry have simplified operational flows, enhance operational resilience, reduce costs, decrease risk, deliver efficiencies, and introduce transparency. Implementing a digitalization strategy can prepare the port infrastructure for the future and establish sustainability by risk analysis and resilience assessment based on different potential scenarios.

7.3. Belief propagation

The capability of propagating the influence of verification via the network, indicated as propagation analysis, is a valuable feature of the BBN. Types of analysis can be performed during propagation analysis. The influence of a recognized variable in the target node is measured by forwarding propagation (Fenton and Neil, 2013). In this study, three observations driven by sensitivity analysis with the highest impact on resilience capacities have been integrated into the underlying BBN model to update all unobserved variables’ conditional probabilities. The results are presented in Table 4 . The decision variables, including port connectivity, training, and service improvement, are chosen from absorptive, recovery, and adaptation/transformation capacities regarding their importance to port resilience. Based on the first scenario, port connectivity is not helpful (“False” state) in the absorption of disruptions, resulting in a reduced expected port resilience from 83.23% to 82.26%. The second scenario is referred to as two failed events related to port connectivity and training, which have an adverse impact on absorption and recovery. Scenario 2 drops absorption, recovery, and resilience values, respectively, to 57%, 55%, and 80.42%. Finally, the third scenario shows the impacts of the failure of port connectivity, training, and service improvement, which reduces all resilience capacities and has a more considerable negative impact on resilience, reducing it to 71.60%. The results of the observations on resilience capacities and consequently expected port resilience created by the preceding scenarios are specified and summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Forward propagation scenarios

(Source: Authors).

| Scenario | Port Connectivity | Training | Service improvement | Absorption (%) | Recovery (%) | Adaptation/Transformation (%) | Expected Resilience (%) | Failure Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Model | 69.00 | 65.00 | 63.00 | 83.23 | ||||

| 1 | False | 57.00 | 65.00 | 63.00 | 82.26 | One | ||

| 2 | False | False | 57.00 | 55.00 | 63.00 | 80.42 | Two | |

| 3 | False | False | False | 57.00 | 55.00 | 48.00 | 71.60 | Three |

Belief propagation analysis represents the advantage of the interrelationship among the variables of the basic BBN model. Based on the forward propagation analysis, all the resilience capabilities are critical for developing resilient port CIs. Propagation analyses enable decision-makers to establish various considerations in the fundamental model with the essential uncertainty to forecast the performance of CIs and obtain a crystal clear understanding for future operations, planning, and management. In addition, policymakers could make effective crucial decisions and build flexible planning to survive any disturbance to the underlying infrastructure according to the forecast.

8. Conclusion

The outbreak of Covid-19 pandemic has revealed the weakness of robust and organized coordination of the operations of ports around the world. Indeed, multifaceted precautionary measures for maritime services and against Covid-19 at ports have induced a progressive shortage of shipping service supply and decreased the operational performance of ports. As such, the Covid-19 pandemic has comprehensively reshaped the industry's environment and posed significant challenges and threats to ports' critical infrastructures (CIs). In addition, it has increased the uncertainty in global supply chains due to the changeable shipping market and the low productivity of port services. Indeed, the risk of supply chain disruptions has been sustained at a high level for a prolonged period. In response, how to mitigate such risk arising from typical epidemic control and prevention has eventually been an urgent issue for the sustainability of ports, from the global to local levels. Hence, in this study, we have proposed a resilience assessment model for critical port infrastructure systems to maintain strategic relationships among the key stakeholders, including terminal operators, shipping firms, logistics service providers, port decision-makers, and port authorities. To our best knowledge, the critical infrastructure systems of ports are seriously under-researched. Hence, our study is in line with the latest research hotspots and topic trends of the ocean and coastal management.

By the time when this study took place, we were still suffering a high level of uncertainty. Nevertheless, the silver lining is that it offers a valuable, unprecedented opportunity for researchers like us to show our ability to react with a prompt approach to challenges, providing contributions to proceed with the changes in human society. We believe that our study offers pivotal academic and practical contributions, not least identifying and classifying underlying factors about resilience capacities and disruptions, as well as the development of an interactive model to assess and monitor the resilience of port CIs. We can use the research outcomes to develop effective and practical business continuity plans for ports and port facilities. It ensures that the personnel and resources are well-protected after a major disruption, thus allowing them to continue functioning effectively and efficiently. Also, with suitable minor modifications based on feedback from relevant experts/stakeholders, this model can be used to quantify the resilience of any CIs. In addition, BNN can help to plan and evaluate the resilience of a specific port or numerous ports in the region to different disruptive incidents. It offers us a unique opportunity to investigate the results of possible decisions about disruptions. Furthermore, our findings initiate the construction of identical metrics to quantify the maritime transport system's resilience.

For further research, our expert interpretation can provide practical knowledge for improving the accuracy of NPTs by using the Delphi technique, swing weights, and classical methods. This sheds light on the possibility of extending, frequent updating, and increasing the resolution of the network. Besides, the development of new resilience model might further encourage interdisciplinary research, such as building resilient vaccine supply chains using cloud-based blockchain. This could provide a breakthrough for ports to improve their capacities and move towards industry 4.0 in the post-pandemic future. Hence, we strongly believe that the study offers the ideal platform for further research and development on resilient port, transport, and urban CIs.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The project is funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and Research Manitoba (#53013), CCAPPTIA (www.ccapptia.com), and the College of Professional and Continuing Education, an affiliate of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (#BHM-2021-212(J)).

Footnotes

For capacity utilization rate node, we used the port's historical data. For desired performance node, we put its mean as 100 and applied the poisson distribution.

Appendix A

Table A.1.

Disruptions of port infrastructure due to the Covid-19 pandemic

(Source: Authors)

| ID | Features | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| D01 | Cargo handling delay | Lack of workforce and misbehavior, low level of cargo handling automation, contractor non-compliance, new working environment, and cyber security failure lead to delays in berthing or loading/unloading operations or cargo evacuation. Delay in cargo handling causes congestion and both land and seaside delays. |

| D02 | Closure of dry ports | Pandemic crises cause operational challenges for the dry-docking process because of uncertainties about on-time dry port operations and vessels' repair. |

| D03 | Congestion | Truck shortages, warehouse closures, and too many empty containers aggravate port and landside congestion, leading to land and seaside delays. Moreover, lower vessel calls lead to the accumulation of uncollected cargo at ports, causing congestion and cargo build-ups, restricting the space for incoming cargo and containers (Krieger et al., 2021). For example, there is a growing build-up of non-essential cargoes at ports in the container sector, causing congestion for the next shipment of imports (Davison, 2020). Besides, due to government restrictions, some suppliers and manufacturers become unable to gather cargo since their warehouses are full or closed. This culminates in a dramatic increase in demand for port storage facilities, reducing the available storage for new cargo (ResearchAndMarkets, 2020). |

| D04 | Crew change service failure | One of the main challenges that maritime industries face has been crew change and travel during the Covid-19 pandemic. So, travel restrictions might cause significant delays in crew changes. Troubles may arise not only for seafarers coming from particular countries of origin with lockdowns but also for all the seafarers using areas that have been infected by the virus. Seafarers may also face quarantine in destination countries. Moreover, in some ports, the port authority is unwilling to let medical staff staying inside the port areas for regular checking of crew members for Covid-19. This results in the cancellation of the changing crew member policy. |

| D05 | Cyberattack | During the Covid-19 pandemic, cyber-attacks include e-mails with viruses or malware connected with hacking companies and/or vessels. Many of them imitate the World Health Organization (WHO), and some adopt actual vessel names and/or Covid-19 to imitate real vessels by malware-contaminated attachments. A network failure contributing to a cyber-attack may not be directly relevant to an opportunistic assault linked with a pandemic. However, this can occur when a range of other events disrupts the sector (Kefalas, 2020). |

| D06 | Cyber security failure | Cyber technology plays a pivotal role in port activities; however, this digitalization is becoming a significant vulnerability to emerging cyber threats. So, challenges of a new working environment besides cyber-attacks, inconsistent application of security protocols, and security gaps can cause cyber security infrastructure failures. Although electronic applications, licenses, and certificates (e.g., CIP-M, DNV GL, etc.) eliminate the necessity of physical interactions, cyber threats and crimes as a matter of urgency can delay the cargo handling process and disrupt the whole system. |

| D07 | Demand change | Shipping lines cut capacity, with a notable rise in the number of canceled departures worldwide. As a result, some ports have recorded significant drops in vessel calls. Also, port calls have reduced because of the nature of the risk and the unsafety of the port (Ship-technology, 2020). On the other hand, the freight volumes reduce because of the prolonged shutdown of factories and strict containment policies proposed by authorities, culminating in considerably lower global economic growth and lower demand for commodities (Ship-technology, 2020). As a result, ports get fewer vessel calls, and supply chains and manufacturing companies have lower production rates. |

| D08 | Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack | Individuals under stay-at-home and isolated employees are inclined towards depending on the internet more substantially in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, the rise of abnormal traffic leads to DDoS attacks during pandemic. |

| D09 | Human-cargo interaction | Continuity of port operations and critical services in port requires interaction between humans and cargoes. That is why maintaining the flow of goods and materials, particularly food and medicines, can lead to the virus' rapid spreading. |

| D10 | Human-human interaction | Ports rely on paper-based arrangements and individual communication because of shore-to-hinterland-based exchanges, the shipboard's norms, and ship-to-shore linkage. So, it addresses the association between shore-based personnel and seafarers at the time of port calls (UNCTAD, 2020c). Furthermore, the current traditional process of delivering the original bill of lading (BL) to the shipping line office and the collection of the paper delivery order add up to person-to-person communication. |

| D11 | Inconsistent application of security protocols | Ports face restrictions and inconsistent policy implementation of security protocols because most workers feel that implementing protocols by shipping companies and port authorities to the pandemic are “knee jerk” reactions (Twining, 2020). |

| D12 | Lack of key personnel | Port workers are identified as key workers to ensure that critical goods continue to flow through ports. So, ordaining new regulations leads to a lack of key personnel at ports. |

| D13 | Lack of truck drivers | During a pandemic, maintaining the quality of trucking services becomes more challenging because of a lack of truck drivers and more restrictive border checks. |

| D14 | Lack of yard workers | Governments establish new regulations that restrict the movement of people. So, the scarcity of workers is creating significant pressure on port infrastructures. |

| D15 | Landside delay | The Covid-19 pandemic triggered significant disruptions in ports related to hinterland transport. Ports have recorded more delays because of trucks getting in and out of ports (Scerra, 2020). Delays in cargo release and trucking activity delays become twofold because of a lack of workforce due to the pandemic crisis. |

| D16 | Leg port failure | In some cases, the partner ports fail to accept incoming vessels because of limited operating capacity, thus reducing vessel calls. |

| D17 | Lower trucking service | Overall trucking availability has decreased, as drivers reject trips to inland provinces to maximize the number of runs per day. Also, authorities' new regulations negatively affect trucking operations in/out of the port areas and to the hinterlands (Notteboom and Pallis, 2020). So, cross-border trucking experiences some congestion, with moderate delays. |

| D18 | Lower vessel calls | When a vessel cancels a planned stop at a port or changes its route due to the downturn in demand by the lockdown measures imposed in the country to stop the coronavirus outbreak, the demand for ship space decreases, which is called blanking of sailing (Resilience360, 2020, Ship-technology, 2020). As a result, in- and outbound cargo volumes decrease, and ports face fewer vessel calls. On the other hand, some ports fail to provide services for vessels coming from infected countries because of new sanitary requirements and/or new regulations, which results in a decline in vessel calls. When the vessels deviate from their intended track because of authorities' new restrictions, maritime shipping companies become reluctant to use this port along their major pendulum route. So, the total number of vessel calls reduce. |

| D19 | Malware and phishing | E-mail frauds trying to deliver spoofing links or malware to hack companies and/or vessels by unauthorized access to the port information and stealing confidential information. For example, they impersonate the WHO or use actual vessel names and/or Covid-19 and warn crew and vessels by malware-infected attachments (Leptos-Bourgi et al., 2020). |

| D20 | New port policies | Refusing vessels to board because of previous port schedule (visiting ports in the affected countries with a high rate of contagion) or new regulations is a critical issue and may result in changes in the ship's schedule and disrupt supply chain systems. |

| D21 | New regulations | Additional processes due to new regulations or ordaining dynamic regulations create a new environment and working conditions, which slow down the process in ports and deviate from the ordinary procedure, and the services become impacted/delayed. Also, with increasing lockdowns by new regulations that restrict business operations and movement of the vast majority of workers, ports experience disruptions due to insufficient workers. |

| D22 | New working environment | The new working environment created by new regulations and remote working of key technicians might lack specific security protocols or regulations. As a result, port operations disruptions can potentially lead to Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks (Leptos-Bourgi et al., 2020) Workers need to discover what the “new normal” will look like, causing delays at ports. The global shift to home office during the Covid-19 pandemic lead to a rise in cyber-attacks. With the widespread change to working remotely for an extended period and the unavoidable vulnerabilities in this operation, more cyber-attacks are expected to occur. |

| D23 | Seaside delay | Vessels all over the world are experiencing delays due to Covid-19 because of additional HSE and customs checks. In some ports, crew changes become difficult or restricted, and vessels may be subject to additional checks or even quarantine measures, depending on the latest ports of call or having reported any symptoms of the disease. (Addison and Hughes, 2020). So, the slowdown in the operations gives rise to extended delays and congestion at ports. Also, delays in (un)loading operations or returning equipment/containers because of new circumstances that are not within their control end up in seaside delays. |

| D24 | Sub-contractors non-compliance | One contractor's non-compliance has unintended consequences for operation in ports and causes delays in the cargo handling process, even if all the others are in full accordance with the new guidelines and procedures (Dennis, 2020). |

| D25 | Unsafe port | In unsafe ports, vessels legally reserve the right to deviate and travel to another port (Lockton, 2020). |

| D26 | Vessel chandelling service failure | This service is responsible for supplying the vessel and its crew with their required commodities in different categories, i.e., provisions, cabin stores, safety and lifesaving equipment, deck and engine stores, firefighting equipment, medical stores, construction materials, chemical and oils, electrical stores, electronics, and navigational supplies. |

| D27 | Vessel deviation | Vessels face difficulties because some ports refuse to board the vessels on the sole basis of unsafety. Hence, deviation causes problems for ports in the long-term since the shipping lines to lower the calls to the target port. Also, ports might use the rules for their rights and refuse to accept the vessels. |

| D28 | Vessel husbandry service failure | Husbandry service generally includes crew handling (e.g., hotel booking, shore pass arrangement), crew welfare (e.g., doctor, mail, internet, mobile), spares clearance, liaison with local authorities, bunker fuels, and communication assistance. |

| D29 | Vessel spare logistic failure | Spare logistical service includes providing the vessel with required spare parts (e.g., gearbox, oil purifier, freshwater pump, hydraulic motors, anchor and anchor chain, compressor, turbocharger, piston). |

| D30 | Workforce underperformance | The workforce refuses to change their routine workplace habits and behaviors, particularly those around physical-distancing measures and facial-covering mandates (Charaumilind et al., 2020). As a result, the port process experiences severe time pressure and an overload of work because of workers' behaviors (OECD, 2020). Considering different stressors in the new working environment, such as using new software and tools, job security, and the possibility of being infected, workers might underperform in even daily routines. |

Table A.2.

Absorptive capacities of a port in the face of a pandemic outbreak

(Source: Authors)

| ID | Features | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| A01 | Availability of spare parts | Spare parts should be available on a timely basis where supply chains are uncertain (UNCTAD, 2020b) to limit the chance of significant shock and enhance the dependability of the port. |

| A02 | Cyber infrastructure | The Covid-19 crisis poses enormous challenges for port CIs because of the urgent need for new remote working. As ports' daily operations include a wide range of networks, cyber-attacks can seriously affect navigation, transportation, content management systems, and port databases. Therefore, setting up a defense framework is crucial to avoid port CI disturbances (Brasington and Park, 2016) |

| A03 | Electronic exchange platform | Single window, port community systems (PCS), and other common electronic exchange platforms help organizations smoothly shift operations from office to home during the time of the Covid-19 pandemic. So, the maritime sector manages requests and assets for port service in an intelligent, organized, secure, and paperless manner. |

| A04 | Availability of equipment | Spare part redundancy results in equipment availability. On-time repair programs for cargo handling enhance the port's ability to endure disruptions. Also, the regular operation of the port at a given time interval is defined as a port's reliability, which is a measure of the effectiveness of the port maintenance. This means that all the gates remain operational during all regularly scheduled hours with minor changes for interacting with crew and truck drivers. |

| A05 | Equipment redundancy | Redundant cargo handling facilities (e.g., cranes and reach-stackers), berth facilities, and strong intermodal facilities (e.g., rail service) can reduce the impact of unprecedented disruptions and increase the robustness of port CIs (Hosseini and Barker, 2016, Ullah et al., 2019, Rice and Trepte, 2012). |

| A06 | Hinterland connection redundancy | The Covid-19 pandemic demonstrated the vulnerability of port efficiency and hinterland connectivity. Due to the importance of short-term emergency response to the pandemic, the availability of reliable and versatile connections ensures the continuous flow of commodities. Enough capacity to enable switching in an emergency (e.g., road, rail) should be facilitated to keep the supply chain open (Aritua and Chiew, 2016). |

| A07 | Human resource management | Reliable human resource management means having fruitful collaboration with labor unions, dealing with performance issues, determining temporary staff requirements, recruiting new workers, determining employee needs, and training employees. All mentioned options become even more critical in the time of a pandemic (UNCTAD, 2020c). So, keeping continuity and controlling disruptions during the pandemic crisis needs well-trained and professional operators and managers to decrease the duration of loading and unloading operations by using the full capacity of the equipment. |

| A08 | Level of automation | Using automated equipment and advanced technological tools, such as blockchain, the Internet of Things (IoT), and artificial intelligence that accelerate decision-making can reduce the dependency on manual works and increase the entire resilient performance of CIs (Chelin and Reva, 2020). |

| A09 | Maintenance strategy | Maintenance has various types and can be either preventive or corrective. In preventive maintenance, a task is done before a failure occurs to minimize its consequence or assess its risk. In conducting corrective maintenance, it is endeavored to restore the equipment functionality (Hupjé, 2018). |

| A10 | Maritime connectivity | Maritime connectivity is defined by the number of ports directly and/or indirectly connected to a port. The more the number of these connections, the less the chance of failure. So, strengthening the connectivity and reliability of maritime transportation should be ensured in maritime connectivity (IMO, 2020a). |

| A11 | Port connectivity | In the context of Covid-19, it significantly influences liner shipping connectivity levels, as well as port calls and maritime cargo flows. The port connectivity/call patterns are required to be closely observed to make sure whether the monitored negative movement is short-term or permanent (UNCTAD, 2020c). |

| A12 | Scheduling flexibility | Because of changing the arrival and berthing of the ships during a pandemic, ports need to offer greater scheduling flexibility to function with operational ease and efficiency. |

| A13 | Space utilization | The port space utilization depends on the port's approach towards operations, equipment, level of automation, and redundancies assumed in the planning. Efficient space utilization provides port authorities with the chance to be more flexible in times of crisis (Rice and Trepte, 2012). |

Table A.3.

Recovery capacity of a port infrastructure

(Source: Authors)

| ID | Features | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| R01 | Cargo disinfection | Protocols of cleaning and disinfection can decrease the spread of Covid-19 on vessels. In addition to regular cleaning and disinfection techniques, cleaning and disinfecting cargoes should be taken into consideration. |

| R02 | Crew disembarking protocol | Crew medical report with a quick Covid-19 test (Deep Throat Saliva Test), a term of responsibility from the agency/master is necessary for the crew to get permission to disembark (disembark Letter). So, professional seafarers and marine personnel should get a permit to get off vessels in port and transit via their area and carry out suitable screening and authorized protocols to facilitate repatriation and crew changes (IMO, 2020b). |

| R03 | Decontamination areas identification | General precautionary measures should be implemented. Hence, decontamination areas in the port buildings and facilities should be identified to apply quarantine, isolation, disinfection, or other measures. |

| R04 | Health protocols | Ports are hazardous locations with large-scale equipment and heavy overhead loads. Those responsible for human health and safety must collaborate with dock and port property planners to allow zoning of properties, operations, cargo storage/supplies, or other emerging risky operations (WSP, 2020). |

| R05 | Operational adjustment | Operational adjustment includes prioritizing operations such as establishing express lanes for foodstuff, and medical supplies, ceasing non-essential services, separating operations, such as providing bunkering service in the anchoring area and forming standby operation teams. |

| R06 | Physical distancing | Physical distancing is a primary solution to reduce the risk of spreading or transmitting Covid-19 in the workplace. Hence, identifying all actions or circumstances where people may be close to each other, assessing the level of risk that people may contract and/or spread Covid-19 in these activities or conditions, and identifying what control measures are practicable to implement considering the level of risk, is essential. |

| R07 | Physical interaction limitation between onshore and onboard staff | To decrease physical interaction, vessel crew members are obliged to make contacts with quayside staff via telephone or radio (or other non-physical means) as much as possible. Also, it is essential to increase digital documentation (ship-to-shore and shore-to-shore) to minimize human interaction to a minimum. |

| R08 | Protective equipment provision | Personal protective equipment (PPE) that contains gowns, face shields, surgical masks, and gloves, which are necessary for healthcare and community environments, as well as during particular procedures during cargo handling (WHO, 2020), should be provided. Also, it is essential to define the appropriate types and certifications where relevant. |

| R09 | Sanitation | As the Covid-19 virus can survive for at least 2–3 days on surfaces of different materials, infected surfaces with Covid-19 must be fully sanitized. |

| R10 | Training | Covid-19 has fueled port capabilities and maritime logistics, allowing operators to focus on responding to port congestion, freight imbalances, and delays. So, online training can provide high-quality, practical information with support in the area of the persistent digital divide and digital connectivity. |

Table A.4.

Adaptive/Transformative capacity of a port infrastructure

(Source: Authors)

| ID | Features | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| T01 | Data interoperability/standardization | Data standardization facilitates the development of a deeper understanding of Covid-19 and the most effective approaches to resolve it. Also, interoperability guidelines create a clear direction against information blocking, as sharing information is crucial at this point in the pandemic (Ebron and Ortiz, 2020). |

| T02 | Distributed ledger technology | As a way to monitor and share data through various database systems, distributed ledger technology allows smart contracts to be settled automatically at the lowest cost, with maximum confidence, and the ability to track their shipments at any time from the point of origin to the point of arrival. There is a significant push to digitalize documentation, especially for trade, thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic (Abouzid and Abouzid, 2020). |

| T03 | Infection certification | The release of special certification aims to help the maritime industry recover its operations better and prepare for Covid-19 or other infectious diseases. The maritime industry's latest infection prevention certification allows shipping lines and port operators to prove that they have protocols and processes in place to detect, monitor, and manage infections and protect their consumers, crews, and workforce. |

| T04 | Internet accessibility | Digital connectivity can be enhanced by improving Internet capabilities and accessibility for port staff and users inside and outside port areas. |

| T05 | Port community system (PCS) | The Port Community System (PCS), as a single, objective, and accessible electronic common platform, provides several benefits, including doing business at ports easier and allowing public and private stakeholders to exchange information safely, which are crucial within the port community during a pandemic (Linton, 2020). |

| T06 | Regional cooperation | Regional cooperation aims to provide systematized regional protocols and familiar feedback measures related to health services and cross-border transportation to create resilience (Ugaz and Sun, 2020). |

| T07 | Service improvement | To sustain vessels moving, cross-border trade flowing, and ports opening, border agencies and ports should keep operational and require effectively be reinforced to encounter the unfolded challenges they confront (UNCTAD, 2020a). |

| T08 | Technology improvement | Digitalization supports the maritime supply chains without interruption during the pandemic. Single Windows (SW), Port Community Systems (PCS), and other electronic common exchange platforms have performed a crucial role during the Covid-19 pandemic. This multidimensional transformation includes taking up both operational and administrative tasks and distant planning (UNCTAD, 2020c). |

References

- Abouzid Hala Nasr, Abouzid Heba Nasr. 2020. From Covid-19 Pandemic to A Global Platform Relies on Blockchain to Manage International Trade, Why Not? [Google Scholar]

- Addison J., Hughes M. News: Crew mental and physical wellbeing during extensive delays. 2020. https://www.standard-club.com/risk-management/knowledge-centre/news-and-commentary/2020/02/news-ships-in-ports-all-over-the-world-are-experiencing-delays-due-to-covid-19.aspx

- Alyami H., Lee P.T.W., Yang Z., Riahi R., Bonsall S., Wang J. An advanced risk analysis approach for container port safety evaluation. Marit. Pol. Manag. 2014;41:634–650. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2014.960498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araz O.M., Choi T.-M., Olson D.L., Salman F.S. Data analytics for operational risk. Decis. Sci. J. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1111/deci.12443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Argyroudis S.A., Mitoulis S.A., Hofer L., Zanini M.A., Tubaldi E., Frangopol D.M. Resilience assessment framework for critical infrastructure in a multi-hazard environment: case study on transport assets. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;714 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aritua B., Chiew W.L.E. World Bank Blogs; 2016. What are some critical innovations for improving port-hinterland connectivity?https://blogs.worldbank.org/transport/what-are-some-critical-innovations-improving-port-hinterland-connectivity [Google Scholar]

- Awad-Núñez S., González-Cancelas N., Soler-Flores F., Camarero-Orive A. A methodology for measuring sustainability of dry ports location based on bayesian networks and multi-criteria decision analysis. Transport. Res. Procedia. 2016;13:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.trpro.2016.05.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Awad-Núñez S., González-Cancelas N., Soler-Flores F., Camarero-Orive A. How should the sustainability of the location of dry ports be measured? A proposed methodology using Bayesian networks and multi-criteria decision analysis. Transport. 2015;30:312–319. doi: 10.3846/16484142.2015.1081618. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyub B.M. Systems resilience for multi-hazard environments: definition, metrics, and valuation for decision making. Risk Anal.: Int. J. 2014;34:340–355. doi: 10.1111/risa.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayes Fusion L. 2020. GeNIe Modeler—User Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Borgonovo E., Plischke E. Sensitivity analysis: a review of recent advances. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016;248:869–887. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2015.06.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brasington H., Park M. Cybersecurity and ports: vulnerabilities, consequences and preparation. Ausmarine. 2016;38:23. [Google Scholar]

- Cai B., Kong X., Liu Y., Lin J., Yuan X., Xu H., Ji R. Application of bayesian networks in reliability evaluation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2019;15:2146–2157. doi: 10.1109/TII.2018.2858281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin F.S., Kofinas G.P., Folke C. Principles of Ecosystem Stewardship: Resilience-Based Natural Resource Management in a Changing World. Springer Science & Business Media; 2009. Principles of ecosystem stewardship: resilience-based natural resource management in a changing world. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss T., Bouncken R.B., Laudien S., Kraus S. Business model reconfiguration and innovation in SMEs: a mixed-method analysis from the electronics industry. Int. J. Innovat. Manag. 2020;24 doi: 10.1142/S1363919620500152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Convertino M., Valverde L.J. Probabilistic analysis of the impact of vessel speed restrictions on navigational safety: accounting for the right whale rule. J. Navig. 2018;1:65–82. doi: 10.1017/S0373463317000480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charaumilind S., Craven M., Lamb J., Wilson M. Preventing Future Waves of COVID-19. McKinsey & Company; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chelin R., Reva D. Security vs efficiency: smart ports in a post-COVID-19 era. Inst. Secur. Stud. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Chua J.Y., Foo R., Tan K.H., Yuen K.F. Maritime resilience during the Covid-19 pandemic: impacts and solutions. Contin. Resil. Rev. 2022;4(1):124–143. doi: 10.1108/crr-09-2021-0031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davison D. Beyond COVID-19 In The Maritime Container Industry. 2020. https://www.wsp.com/en-GL/insights/beyond-covid-19-in-the-maritime-container-industry

- Dennis C. Construction Compliance & Safety During COVID-19. 2020. https://www.levelset.com/blog/construction-compliance-covid-19l/

- Djalante R., Shaw R., Dewit A. Progress in disaster science building resilience against biological hazards and pandemics: Covid-19 and its implications for the sendai framework. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020;6:100080. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorn N., Gardoni P., Murphy C. A multidisciplinary definition and evaluation of resilience: the role of social justice in defining resilience. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2019;4:112–123. doi: 10.1080/23789689.2018.1428162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebron S., Ortiz A. RTI Int; 2020. Supporting Interoperability During A Pandemic.https://www.rti.org/insights/data-standardization-interoperability-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- Fenton N., Neil M. Risk Assessment and Decision Analysis with Bayesian Networks. first ed. CRC Press; 2013. Assessment and decision analysis with bayesian networks. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R., Bekera B. A metric and frameworks for resilience analysis of engineered and infrastructure systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2014;121:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2013.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galbusera L., Giannopoulos G., Argyroudis S., Kakderi K. A boolean networks approach to modeling and resilience analysis of interdependent critical infrastructures. Comput. Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2018;33:1041–1055. doi: 10.1111/mice.12371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goerlandt F., Montewka J. A framework for risk analysis of maritime transportation systems: a case study for oil spill from tankers in a ship-ship collision. Saf. Sci. 2015;76:42–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2015.02.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golan M.S., Jernegan L.H., Linkov I. Trends and applications of resilience analytics in supply chain modeling: systematic literature review in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2020;1 doi: 10.1007/s10669-020-09777-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui D., Wang H., Yu M. Risk assessment of port congestion risk during the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022;10 doi: 10.3390/jmse10020150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haimes Y.Y., Crowther K., Horowitz B.M. Homeland security in emergent systems protection with resilience preparedness: balancing. Syst. Eng. 2008;14:287–307. doi: 10.1002/sys. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hänninen M. Bayesian networks for maritime traffic accident prevention: benefits and challenges. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014;73:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hänninen M., Valdez Banda O.A., Kujala P. Bayesian network model of maritime safety management. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014;41:7837–7846. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2014.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D., Ramirez-Marquez J.E. Generic metrics and quantitative approaches for system resilience as a function of time. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2012;99:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2011.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holling C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Systemat. 1973;4:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain N.U.I., El Amrani S., Jaradat R., Marufuzzaman M., Buchanan R., Rinaudo C., Hamilton M. Modeling and assessing interdependencies between critical infrastructures using Bayesian network: a case study of inland waterway port and surrounding supply chain network. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020;198 doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2020.106898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain N.U.I., Nur F., Hosseini S., Jaradat R., Marufuzzaman M., Puryear S.M. A Bayesian network-based approach for modeling and assessing resilience: a case study of a full-service deep-water port. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019;189:378–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2019.04.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain N.U.I., Nur F., Jaradat R., Hosseini S., Marufuzzaman M., Puryear S.M., Buchanan R.K. Metrics for assessing overall performance of inland waterway ports: a bayesian network based approach. Complexity. 2019;17 doi: 10.1155/2019/3518705. 2019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini S., Barker K. Modeling infrastructure resilience using Bayesian networks: a case study of inland waterway ports. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2016;93:252–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2016.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- House W. 2013. Presidential Policy Directive 21: Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience.https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/02/12/presidential-policy-directive-critical-infrastructure-security-and-resil Washington, DC. URL: accessed 6.6.20. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C.H., Tai H.H., Lee Y.N. Port vulnerability assessment from the perspective of critical infrastructure interdependency. Marit. Pol. Manag. 2014;41:589–606. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2013.856523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hupjé E. 2018. Types of Maintenance: The 9 Different Strategies Explained. Road to Reliab.https://www.roadtoreliability.com/types-of-maintenance/ [Google Scholar]

- IMO Prologue to Maritime Perspectives: Digital Connectivity & Data Standards – Singapore online event series. 2020. http://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/SecretaryGeneral/SpeechesByTheSecretaryGeneral/Pages/Digitalization-maritime-perspectives-.aspx

- IMO Recommended framework of protocols for ensuring safe ship crew changes and travel during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. 2020. https://www.seafarerswelfare.org/assets/documents/resources/IMO-Recommended-Framework-of-Protocols-for-ensuring-safe-ship-crew-changes-and-travel-during-the-Coronavirus-COVID-19-pandemic-22-April-2021.pdf