Abstract

Objective

This study sought to examine how access to contraception and cervical and breast cancer screening in British Columbia, Canada, has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

From August 2020 to March 2021, 3691 female residents of British Columbia (age 25–69 y) participated in this study. We used generalized estimating equations to analyze the proportion of females accessing contraception and the proportion having difficulty accessing contraception across the different phases of pandemic control measures, and logistic regression to analyze attendance at cervical and breast cancer screening. We added sociodemographic and biological variables individually into the models. Self-reported barriers to accessing contraception and attending screening were summarized.

Results

During phases with the highest pandemic controls, self-reported access to contraception was lower (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.90–0.98; P = 0.005) and difficulty with access was higher (OR 2.74; 95% CI 1.54–4.88; P = 0.001). A higher proportion of adults aged 25–34 years reported difficulty accessing contraception than those aged 35–39 years (P < 0.0001), and participants identifying as Indigenous had higher odds of access difficulties (OR 5.56; 95% CI 2.44–12.50; P < 0.001). Of those who required screening during the COVID-19 pandemic, 62% and 54.5% did not attend at least one of their cervical or breast screening appointments, respectively. Those with a history of breast cancer had significantly higher odds of self-reporting having attended their mammogram appointment compared with those without a history of breast cancer (OR 5.62; 95% CI 2.69–13.72; P < 0.001). The most common barriers to screening were difficulty getting an appointment and appointments being considered non-urgent.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has uniquely affected access to contraception and cancer screening participation for various subgroups. Self-reported data present potential avenues for mitigating barriers.

Keywords: contraception, early detection of cancer, COVID-19, breast neoplasms

Résumé

Objectif

Cette étude visait à examiner à quel point la pandémie de COVID-19 a nui à l’accès à la contraception et au dépistage des cancers du sein et du col de l’utérus en Colombie-Britannique (Canada).

Méthodologie

Pour la période d’août 2020 à mars 2021, 3 691 résidentes de la Colombie-Britannique (âgées de 25 à 69 ans) ont participé à cette étude. Nous avons utilisé des équations d’estimation généralisées pour analyser les proportions de femmes ayant eu accès à la contraception et de femmes ayant éprouvé des difficultés d’accès pendant les différentes phases de mesures de gestion pandémique. Nous avons aussi effectué une analyse de régression logistique concernant le dépistage des cancers du sein et du col de l’utérus. Nous avons ajouté des variables sociodémographiques et biologiques individuellement dans les modèles. Les obstacles autodéclarés concernant l’accès à la contraception et au dépistage ont été résumés.

Résultats

Pendant les phases où les mesures de gestion pandémique étaient les plus contraignantes, l’accès autodéclaré à la contraception s’est avéré inférieur (RC : 0,94; IC à 95 % : 0,90–0,98; p = 0,005) et les difficultés d’accès ont été plus élevées (RC : 2,74; IC à 95 % : 1,54–4,88; p = 0,001). Les difficultés d’accès à la contraception ont été déclarées davantage chez les 25 à 34 ans que chez les 35 à 39 ans (p < 0,0001). Les participantes s’identifiant comme autochtones avaient le plus grand risque de difficultés d’accès (RC : 5,56; IC à 95 % : 2,44–12,50; p < 0,001). Chez celles devant subir un dépistage pendant la pandémie, 62 % et 54,5 % ne se sont pas présentées à au moins un de leurs rendez-vous pour le dépistage du cancer du col de l’utérus ou du cancer du sein, respectivement. Celles ayant un antécédent de cancer du sein étaient significativement plus susceptibles d’autodéclarer s’être présentées à leur rendez-vous de mammographie que celles sans antécédent (RC : 5,62; IC à 95 % : 2,69–13,72; p < 0,001). Les obstacles au dépistage les plus fréquemment rapportés étaient la difficulté à obtenir un rendez-vous et les rendez-vous considérés comme non urgents.

Conclusions

La pandémie de COVID-19 a eu une incidence unique sur l’accès à la contraception et la participation au dépistage du cancer pour diverses classes démographiques. Les données autodéclarées présentent des solutions potentielles pour remédier aux obstacles.

A. Baaske

Introduction

Internationally, women’s access to contraception and to cervical and breast cancer screening has been disrupted1, 2, 3 as a result of the pandemic-associated public health measures designed to limit the spread of SARS-CoV-2.4 , 5 Interrupted access to contraception can result in consequences such as unintended pregnancy.6 Delays in cancer screening can result in later state disease detection and excess morbidity and mortality. For instance, the 5-year survival rate for cervical cancer decreases from 93% (stage 1A) to 80% (stage 1B) and further to 15% (stage 4B) when diagnosis and treatment starts at later stages.7

Though there are international data, the effect of the pandemic on contraception and cancer screening access has not been well characterized for women in Canada. Other topics currently underexplored include whether access to contraception and cancer screening has been differentially impacted based on sociodemographic factors, as physical and mental health outcomes have during the pandemic,8 , 9 and barriers to health-seeking behaviours. Furthermore, across jurisdictions, the pandemic public health response has been tailored to prevent hospitalization and infection rates,10 resulting in a series of lockdowns followed by periods of relaxed restrictions. Yet little research has explored the impact of these different “phases” of control measures on access to reproductive care and screening services.

To address these gaps, we examined access to birth control and emergency contraception across different phases of the pandemic, and attendance at the Pap test for cervical screening and mammography for breast screening across a 1-year period in British Columbia (BC). Based on the published literature,1, 2, 3 we hypothesized decreases in access and attendance, specifically during the phases of heightened pandemic controls. We hypothesized that factors such as younger age, non-White ethnicity, rural living, lower household income, lower education level, immigrant status, Indigenous ancestry, nonheterosexual orientation, and nonbinary/trans gender identity,1 , 2 , 11, 12, 13 as well as no history of breast or cervical cancer, would be predictors of access difficulties. Finally, we expected that difficulty getting an appointment and fears about exposure to SARS-CoV-2 would be commonly reported as barriers to access.14

Methods

Setting and Participants

The current study was a part of a larger study from Women's Health Research Institute (full study methods reported elsewhere15 , 16), which invited residents of BC aged 25 to 69 years to participate in an online survey on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic between mid-August 2020 and March 1, 2021.17 The participants were stratified into 9 5-year age strata and recruitment continued until a target of n = 750 was reached for each stratum. Public recruitment occurred through social media and research platforms. The recruitment ended for individuals aged 45 to 64 years in mid-November 2020 and individuals aged 40 to 44 years in mid-December after targets were reached for these strata. Ethical approval was received from BC Children’s and Women’s Research Ethics Board (approval number H20-01421).

Survey Design and Measures

We asked the participants to respond retrospectively across 5 phases of the pandemic, delineated by pandemic control measures, and prepandemic for specific items. The phases were as follows: pre-COVID (December 2019 to mid-March 2020), phase 1 (mid-March 2020 to mid-May 2020), phase 2 (mid-May 2020 to November 30, 2020), phase 3 (mid-May 2020 to August 31, 2020), phase 4 (September 1, 2020 to October 31, 2020), and phase 5 (November 1, 2020 to March 1, 2021).10 The participants who completed the survey before November 30, 2020, were asked to respond based on pre-COVID outcomes as well as phase 1 and phase 2. On November 30, 2020, phase 2 was removed and phases 3 to 5 were added.

For each phase, the participants responded to 4 contraception outcome measures: (1) regularly accessed birth control methods (e.g., birth control pill), (2) accessed emergency contraception (e.g., Plan B), (3) had difficulty accessing birth control methods, and (4) had difficulty accessing emergency contraception. Those who indicated that they had difficulty accessing contraception at any point during phases 1 through 5 were asked “What made accessing birth control or emergency contraceptives difficult during COVID-19?” and selected all that applied from a list of options ( Table S1). The participants were eligible for contraception outcomes analysis if they responded to ≥1 outcome measure across all phases and were of female sex, not postmenopausal, and not pregnant. Although it is possible for females >55 to still be menstruating, we also restricted contraception analyses to those aged ≤55 years.

We asked all survey participants to report on their attendance (attended all, some, or none) at cervical or breast screenings during the pandemic. The participants who reported that they only attended some or none of their appointments were asked “Why did you not attend the appointment(s)” and were able to select from a list of reasons (options were mutually exclusive). The listed reasons included: my doctor or clinic was not accepting in-person appointments, my appointment was considered “nonurgent,” worried about visiting doctors or doctors’ office, and other. The participants who selected “other” were able to provide a free-text response. For the analyses of cervical (Pap) and breast (mammogram) cancer screening outcomes, the eligibility was restricted to female sex and those who responded that during the COVID-19 pandemic (mid-March to now) they were due for, or in need of, a Pap test/mammogram.

We collected sociodemographic information including sex assigned at birth, postmenopausal status (have not had a period in ≥1 year), age, ethnicity (White and non-White), Indigenous ancestry, and other demographics (online Appendix). Indigenous ancestry was self-reported and assessed separately from ethnicity.

Data Analysis

All analyses were carried out in R v. 4.0.3.18 The significance threshold was set at P < 0.05. Missing data were excluded from analyses.

Access to birth control/emergency contraception was pooled due to a small proportion of respondents indicating accessing emergency contraception (1.7% pre-COVID, dropping to <1% in the later phases). By using generalized estimating equations with a first order autoregressive /cicorrelation structure using the “geepack” package19 , 20 to account for the repeated measures and including age as a covariate, we estimated both the proportion accessing contraception and the proportion having difficulty with access across the phases. We investigated the relationships between access, having difficulty accessing contraceptives, and sociodemographic variables by adding them individually to the models.

Attendance at required cervical or breast screening was dichotomized into attendance at none/some versus all appointments. The proportion attending all visits was analyzed using logistic regression. The reasons for nonattendance were reported as the percent of those who attended some/none of their appointments. We conducted thematic analyses on the open-ended responses for reasons for nonattendance at breast and cervical screening. We used a deductive, essentialist approach and constructed themes around semantic content by analyzing the surface meaning of each response.21

Results

In total, 3691 participants who provided informed consent for our larger survey were eligible for this study, and among these, we had sample sizes n = 2542 for contraception outcomes, n = 1077 for Pap test outcomes, and n = 1226 for mammogram outcomes (online Appendix). A participant could fall in more than 1 of these 3 cohorts.

Access to Contraception During COVID-19

After controlling for age, there was a significant relationship between the pandemic phase and both the proportion of females that accessed (P < 0.02) and that had difficulty accessing (P < 0.001) birth control/emergency contraception. During phase 1, fewer people accessed contraception (P = 0.005), and during phases 1 and 2 more people had difficulty accessing contraception (both P = 0.001) than during pre-COVID. Across all phases, we found a significant effect of age, with younger participants (25–34 years) proportionately more likely to report that they were accessing contraception (P < 0.0001) and had difficulty accessing contraception (P < 0.0001). Across the phases, <3% of those aged 35 to 55 years reported difficulties with access (Table 1 , Supplemental Figures S1 and S2).

Table 1.

Impact of age and COVID-19 phase on contraception access

| Predictor | Using contraception |

Difficulty accessing contraception |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age group, y | ||||

| 25–29 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 30–34 | 0.70 (0.47–1.02) | 0.065 | 0.63 (0.25–1.58) | 0.325 |

| 35–39 | 0.37 (0.26–0.53) | < 0.001 | 0.40 (0.18–0.89) | 0.025 |

| 40–44 | 0.31 (0.22–0.44) | < 0.001 | 0.24 (0.10–0.59) | 0.002 |

| 45–49 | 0.26 (0.18–0.38) | < 0.001 | 0.18 (0.06–0.52) | 0.002 |

| 50–55 | 0.14 (0.08–0.22) | < 0.001 | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | < 0.001 |

| Phase | ||||

| Pre-COVID | Reference | Reference | ||

| Phase 1 | 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | 0.005 | 2.74 (1.54–4.88) | 0.001 |

| Phase 2 | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 0.218 | 3.20 (1.66–6.18) | 0.001 |

| Phase 3 | 0.99 (0.90–1.08) | 0.761 | 1.75 (0.68–4.48) | 0.243 |

| Phase 4 | 1.09 (0.96–1.24) | 0.206 | 1.59 (0.59–4.27) | 0.359 |

| Phase 5 | 1.18 (1.02–1.36) | 0.025 | 2.14 (0.89–5.15) | 0.090 |

After controlling for age and phase, we found a significant relationship between Indigenous status and the proportion who had difficulty accessing contraception, with self-identified Indigenous participants having significantly higher odds of experiencing difficulty than non-Indigenous participants (P < 0.001). Further, we found that nonheterosexual participants had a significantly lower prevalence of accessing contraception than heterosexual respondents across all phases (P = 0.001), but there was no impact of sexual orientation on difficulties accessing (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Bivariable results of sociodemographic factors assessed individually on the proportion using/with difficulty accessing contraception

| Predictor | Using contraception |

Difficulty accessing contraception |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

| Geographic region | ||||

| Fraser | Reference | Reference | ||

| Interior | 1.33 (0.85–2.08) | 0.213 | 1.09 (0.40–2.93) | 0.868 |

| Northern | 0.75 (0.36–1.57) | 0.444 | 2.14 (0.47–9.70) | 0.324 |

| Vancouver Coastal | 1.32 (1.03–1.70) | 0.028 | 0.60 (0.29–1.25) | 0.172 |

| Vancouver Island | 1.13 (0.83–1.53) | 0.433 | 0.68 (0.29–1.60) | 0.374 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non-White | 1.32 (0.97–1.79) | 0.073 | 0.78 (0.37–1.64) | 0.506 |

| Household income, CAD$ | ||||

| <10 000–20 000 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 20 000–40 000 | 0.7 (0.37–1.31) | 0.265 | 0.64 (0.19–2.14) | 0.465 |

| 40 000–60 000 | 1.09 (0.61–1.97) | 0.764 | 0.73 (0.23–2.31) | 0.594 |

| 60 000–80 000 | 0.98 (0.55–1.75) | 0.938 | 0.38 (0.09–1.60) | 0.186 |

| 80 000–100 000 | 0.57 (0.32–1.01) | 0.055 | 0.18 (0.03–0.98) | 0.047 |

| 100 000–150 000 | 1.06 (0.62–1.82) | 0.828 | 0.50 (0.15–1.67) | 0.260 |

| >150 000 | 0.94 (0.55–1.61) | 0.835 | 0.36 (0.11–1.20) | 0.096 |

| Education | ||||

| More than high school | Reference | Reference | ||

| High school or less | 0.82 (0.58–1.17) | 0.278 | 0.97 (0.34–2.75) | 0.955 |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Cis-gender | Reference | Reference | ||

| Non–cis-gender | 0.53 (0.22–1.29) | 0.160 | 0.51 (0.06–4.03) | 0.524 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | Reference | Reference | ||

| Nonheterosexual | 0.62 (0.46–0.82) | 0.001 | 0.79 (0.39–1.61) | 0.519 |

| Immigrant status | ||||

| Immigrated <5 y ago | Reference | Reference | ||

| Immigrated ≥5 y ago | 1.24 (0.52–2.93) | 0.632 | 1.47 (0.18–12.32) | 0.721 |

| Nonimmigrant | 1.24 (0.64–2.39) | 0.521 | 1.38 (0.25–7.66) | 0.713 |

| Indigenous status | ||||

| Non-Indigenous | Reference | Reference | ||

| Indigenous | 0.95 (0.58–1.56) | 0.849 | 5.56 (2.44–12.50) | < 0.001 |

Note: All sociodemographic variables were adjusted for phase and age.

For those who had difficulty accessing contraception at any point (78 respondents), difficulty getting an appointment (37%) and worries about COVID-19 exposure (28%) were the top barriers to access. Other barriers to access endorsed by respondents are reported in, Table S1 in online Appendix.

Cervical Screening Attendance Throughout the Pandemic: Factors and Barriers

Of the sample who self-reported requiring a cervical screening (Pap test), 37.0% attended all, 9.9% attended some, and 52.1% attended none of their appointments. None of the sociodemographic factors nor history of cervical cancer affected the attendance at the cervix screenings (all P > 0.05).

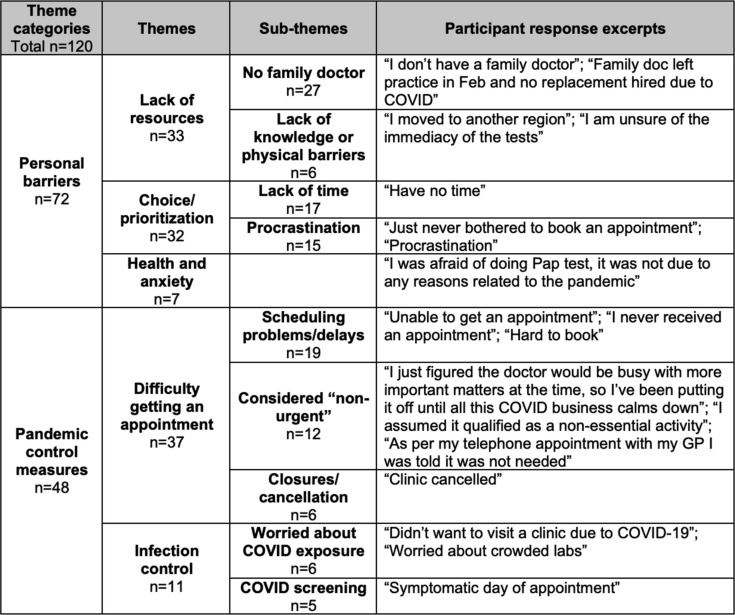

For the respondents who indicated that they attended some or none of their cervical screening appointments (668 respondents), primary endorsed reasons were as follows: my doctor or clinic was not accepting in-person appointments (32.5%), my appointment was considered nonurgent (25.3%), worried about visiting doctors or doctors’ office (24.6%), other (17.7%). For the 17.7% of respondents (118) who endorsed “other” and provided an open-ended response, thematic analysis revealed 2 overarching theme categories of “personal barriers” and “pandemic control measures,” each with several themes and subthemes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Thematic map of free-text responses to the question “Why did you not attend the (Pap test) appointment(s)?” Note: n values represent the number of participant responses within subthemes.

Breast Screening Attendance Throughout the Pandemic: Factors and Barriers

Of the sample who self-reported requiring breast screening (mammogram), 44.8% attended all, 10.7% attended some, and 43.8% attended none of their appointments.

Those with a history of breast cancer had significantly higher odds of self-reporting attending their mammogram during COVID-19 compared with those who did not (odds ratio 5.62; 95% CI 2.69–13.72; P < 0.001). There was no significant relationship between the mammogram attendance and any sociodemographic factor analysed (all P > 0.05). Appointments being considered “nonurgent” was the most endorsed primary reason for nonattendance at mammogram (30.1%), followed by: other (27.4%), worried about visiting doctors or doctors’ office (23.1%), my doctor or clinic was not accepting in-person appointments (19.3%).

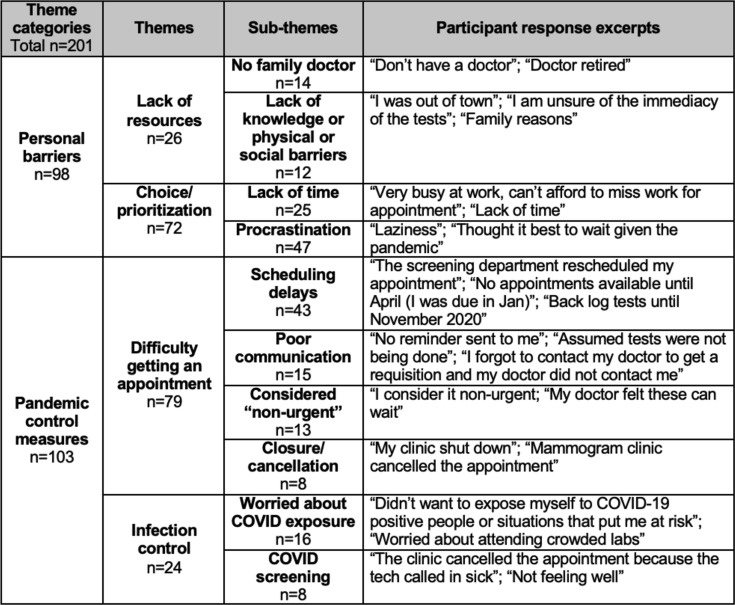

For those that selected “other” and provided an open-ended response (183 respondents), thematic analysis revealed overarching theme categories of “personal barriers” and “pandemic control measures,” each with several themes and subthemes (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Thematic map for free-text responses to the question “Why did you not attend the (mammogram) appointment(s)?” Note: n values represent the number of participant responses within subthemes. Responses were excluded (cervical analysis: n = 11, breast analysis: n = 7) if respondents used the free-text space to discuss something other than barriers to attendance.

Discussion

Our study showed a correlation between high levels of pandemic controls and a higher prevalence of difficulty accessing contraception, which continued even once the pandemic control measures loosened. This finding is unlike past findings1 and may have important implications for the longer-term effects of strict controls on female public health. Our findings did not support the notion that nonheterosexual woman are more likely to face barriers to contraception access during COVID-19 than heterosexual women.1 Rather, we found that nonheterosexual females reported accessing birth control less, consistent with the generally lower prevalence of contraception use among LGBTQ women.22

Our study also described the low rates of breast and cervical screening. Before the pandemic, between 2017 to 2019, participation in the BC Cancer Breast Screening Program was approximately 50% and cervical screening participation was approximately 68% (corrected for hysterectomy rate).23 , 24 Therefore, our data suggested 9% and 93.75% increases in nonparticipation in breast and cervical cancer screening during COVID-19, respectively. To clear the large queue of missed screenings and support participation during future disruptions, clear communication around scheduling, messaging on the importance of timely screening, and guidance on screening participation for individuals without a family doctor are points to consider. The barriers to cervical screening attendance identified in this analysis highlighted an opportunity for innovative approaches that minimize in-person contact, such as telehealth with self-collected screening options.25 Those without a history of breast cancer may have been less likely to seek breast screening during the COVID-19 pandemic due to less motivation among cancer-free populations to be screened for cancer.26 Mammography participation may have also been disrupted due to deferrals of radiology appointments perceived as “less urgent,”7 which is consistent with other findings that show larger volume drops for screening mammography compared with diagnostic mammography during COVID-19.27

Others have documented both within and outside of the COVID-19 pandemic that other sociodemographic factors, such as ethnicity, are predictors of health care access.1 , 11, 12, 13 Future research should assess the impact of the pandemic on groups previously demonstrated to face inequitable health care access using representative samples to the overall target population.

The limitations of our study were the retrospective nature of the questions, which could have introduced recall error, and the confinement of this study to the BC population. This study included a population with a higher percentage of respondents who identified as White, with more than a high school education, and who were more likely to live in the southern part of the province compared to the general population of BC (online Appendix),28 limiting the generalizability to similar populations. As well, the level of contraception access was not specified, which could have limited interpretability. For example, we do not know whether “difficulty getting an appointment” occurred at the level of initial contact with a clinic or due to clinics being over capacity. It is also unclear whether respondents may have changed the type of contraception they used, such as turning from contraception methods that require insertion (e.g., intrauterine devices) or hormonal methods that require a prescription to nonhormonal contraception (e.g., barrier methods). Because the question about birth control was in brackets (“e.g., birth control pill”), respondents may have assumed that it was referring to hormonal methods as opposed to all methods. Of note, it would still be an issue if females turned to less effective contraception such as nonhormonal methods, but this was not captured by our survey. The use of self-reported data was another limitation. For example, respondents may have self-reported requiring screening when in fact they were not due for an appointment as per BC guidelines.29 , 30

Conclusion

This study provided critical data on the barriers to females’ access to contraception and cancer screening in Canada during a year of unprecedented health care disruptions. Self-reported barriers to screening attendance presented in this study offer potential avenues for increasing cervical and breast cancer screening participation. These data can inform health leadership on the impacts of restricting health service delivery and of demographics warranting thoughtful consideration as they navigate pandemic recovery and future planning.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Falla Jin at the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute for her assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Funding for this project was from a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Grant (19055) and a BC Women's Health Foundation Grant (LRZ30421) both awarded to Dr. Lori A. Brotto and Dr. Gina S. Ogilvie.

All authors have indicated they meet the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2022.05.011.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Lindberg L.D., VandeVusse A., Mueller J., et al. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the 2020 Guttmacher survey of reproductive health experiences. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/early-impacts-covid-19-pandemic-findings-2020-guttmacher-survey-reproductive-health Available at: Accessed on June 23, 2021.

- 2.Papautsky E.L., Hamlish T. Patient-reported treatment delays in breast cancer care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;184:249–254. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05828-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller M.J., Xu L., Qin J., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on cervical cancer screening rates among women aged 21-65 years in a large integrated health care system – Southern California, January 1-September 30, 2019, and January 1-September 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:109–113. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7004a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.British Columbia Pharmacy Association BC pharmacists message to patients on medication supplies during COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.bcpharmacy.ca/news/bc-pharmacists-message-patients-medication-supplies-during-covid-19-outbreak Available at: Accessed on January 27, 2021.

- 5.Canadian Association of Radiologists Canadian Society of Breast Imaging and Canadian Association of Radiologists joint position statement on COVID-19. https://car.ca/news/canadian-society-of-breast-imaging-and-canadian-association-of-radiologists-joint-position-statement-on-covid-19/ Available at: Accessed on January 27, 2021.

- 6.World Health Organization Contraception. https://www.who.int/health-topics/contraception#tab=tab_1 Available at: Accessed on August 4, 2021.

- 7.Canadian Cancer Society Survival statistics for cervical cancer. https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/cervical/prognosis-and-survival/survival-statistics Available at: Accessed on September 2, 2021.

- 8.Boserup B., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Disproportionate impact of COVID-19 pandemic on racial and ethnic minorities. Am Surg. 2020;86:1615–1622. doi: 10.1177/0003134820973356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith L., Jacob L., Yakkundi A., et al. Correlates of symptoms of anxiety and depression and mental wellbeing associated with COVID-19: a cross-sectional study of UK-based respondents. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Government of British Columbia COVID-19 (novel coronavirus) https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/about-bc-s-health-care-system/office-of-the-provincial-health-officer/current-health-topics/covid-19-novel-coronavirus Available at: Accessed on February 10, 2021.

- 11.Hulme J., Dunn S., Guilbert E., et al. Barriers and facilitators to family planning access in Canada. Healthc Policy. 2015;10:48–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agénor M., Hughto J.M., Peitzmeier S.M., et al. Gender identity disparities in Pap test use in a sample of binary and non-binary transmasculine adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1015–1017. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4400-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoueri-Mychasiw N., McDonald P.W. Factors associated with underscreening for cervical cancer among women in Canada. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:6445–6450. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.11.6445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Endler M., Haidari T.A., Benedetto C., et al. How the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic is impacting sexual and reproductive health and rights and response: results from a global survey of providers, researchers, and policy-makers. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100:571–578. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogilvie G.S., Gordon S., Smith L.W., et al. Intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine: results from a population-based survey in Canada. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1017. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11098-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brotto L.A., Chankasingh K., Baaske A., et al. The influence of sex, gender, age, and ethnicity on psychosocial factors and substance use throughout phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0259676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Women’s Health Research Institute Research and innovation in women’s health. COVID-19 RESPPONSE study. https://whri.org/covid-19-respponse-study/ Available at: Accessed on August 4, 2021.

- 18.R Core Team. The R project for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/ Available at: Accessed on June 17, 2021.

- 19.Højsgaard S., Halekoh U., Yan J. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J Stat Softw. 2005;15:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan J., Fine J. Estimating equations for association structures. Stat Med. 2004;23:859–874. doi: 10.1002/sim.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2008;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ela E.J., Budnick J. Non-heterosexuality, relationships, and young women’s contraceptive behaviour. Demography. 2017;54:887–909. doi: 10.1007/s13524-017-0578-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.BC Cancer BC Cancer breast screening 2019 program results. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/Documents/Breast-Screening-Program-Report-2019.pdf Available at: Accessed on April 27, 2022.

- 24.BC Cancer BC Cancer cervix screening 2018 program results. http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/Documents/Cervix-Program-Results-2018.pdf Available at: Accessed on April 27, 2022.

- 25.Pederson H.N., Smith L.W., Racey C.S., et al. Implementation considerations using HPV self-collection to reach women under-screened for cervical cancer in high-income settings. Curr Oncol. 2018;25:e4–e7. doi: 10.3747/co.25.3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stockwell D.H., Woo P., Jacobson B.C., et al. Determinants of colorectal cancer screening in women undergoing mammography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1875–1880. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song H., Bergman A., Chen A.T., et al. Disruptions in preventative care: mammograms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Serv Res. 2021;56:95–101. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Statistics Canada Census profile, 2016 census: British Columbia and Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=59&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&SearchText=Canada&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&type=0 Available at: Accessed on November 22, 2020.

- 29.BC Cancer Who should get a mammogram? http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/breast/get-a-mammogram/who-should-get-a-mammogram Available at: Accessed on October 14, 2021.

- 30.BC Cancer Who should get screened? http://www.bccancer.bc.ca/screening/cervix/get-screened/who-should-get-screened Available at: Accessed on October 14, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.