Abstract

Public health and media discourses have often portrayed older adults as a vulnerable group during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, some emerging research is showing that older adults are faring better in terms of their mental health when compared to their younger counterparts. Understanding older adults' mental well-being during the pandemic requires in-depth exploration of the different place-based resources and systems around them. In particular, rural older adults face distinct challenges and opportunities related to accessing valued resources to promote their well-being. Drawing together research on aging and multi-systemic resilience, we explored what strategies, resources, and processes rural older adults valued in the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. A series of 51 semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted from May to August 2020 with 26 rural older adults in Manitoba, Canada. Despite adversities, participants drew on and developed resources at the individual, local, community, institutional, and societal level to support their well-being. Specifically, they identified individual strategies (e.g., positivity, acceptance, and gratitude), resources in their immediate environments (e.g., opportunities to keep busy, connect with friends, family and neighbours, and outdoor visits), and community organizations that contributed to their well-being. They also identified broader systems that shaped their resilience processes, such as access to health services, opportunities to volunteer and support others, media stories, reliable information, and public health policies and practices that value older adult lives. Importantly, some resources were less accessible to some participants, highlighting the need to develop strategies that address inequitable resources at different levels. By describing rural older adults’ resilience we seek to advance the growing body of research in relation to social ecological resilience that moves beyond a focus on individual characteristics to include understanding of the role of material, social, and cultural contexts.

Keywords: Older adults, Resilience, Rural, COVID-19, Well-being, Canada

Credit author statement

Conceptualization, Rachel Herron, Breanna C. Lawrence, Nancy E. G. Newall, Doug Ramsey and Candice M. Waddell- Henowitch; Data curation, Rachel Herron and Jennifer Dauphinais; Formal analysis, Rachel Herron, Breanna C. Lawrence, and Jennifer Dauphinais; Funding acquisition, Rachel Herron; Methodology, Rachel Herron, Breanna C. Lawrence, Nancy E. G. Newall, Doug Ramsey and Candice M. Waddell- Henowitch; Project administration, Jennifer Dauphinais; Supervision, Rachel Herron; Writing – original draft, Rachel Herron and Breanna C. Lawrence; Writing – review & editing, Nancy E. G. Newall, Doug Ramsey, Candice M. Waddell- Henowitch and Jennifer Dauphinais.

During the current COVID-19 pandemic, older adults have often been portrayed as “at risk” and “vulnerable” with much less attention to their diversity as a group, the different contexts in which they live, and their unique experiences of the pandemic (Chivers, 2020; Morgan et al., 2021). In Canada, governments and medical experts advised older adults to self-isolate and cautioned against visits with community-dwelling older adults to protect them from COVID-19 (Government of Canada, 2021). Part of the reason for this is because older adults were initially at higher risk of not only contracting COVID-19, but also being hospitalized and dying from the virus than other age groups (Arentz et al., 2020). For example, in July 2020 people aged 60 years and older represented 33% of Canadian COVID-19 cases and 96.7% of deaths due to COVID-19 (PHAC, 2020). Notably, approximately 80% of these deaths were individuals living in long-term residential care facilities (CIHI, 2020). The high rates of mortality in residential care facilities highlight the importance of context in understanding both the vulnerability and resilience of older adults. Indeed, older adults are a diverse group with different values and place-based resources during COVID-19. In this article, we focus specifically on the experiences of rural community-dwelling older adults, a group that has received less attention in research on COVID-19.

Rural community-dwelling older adults face distinct challenges and opportunities related to accessing valued resources that promote their well-being. Large-scale processes such as economic and social restructuring have contributed to the vulnerability of rural older adults (Joseph and Cloutier-Fisher, 2004). In general, they face challenges in relation to isolation and exclusion due to lack of services, including transportation, communications infrastructure, and health and social services (Walsh et al., 2020). To address this lack of formal support, rural older adults tend to rely more on informal support (e.g., relatives, close friends, and voluntary organizations) than their urban counterparts (Keating et al., 2011; Skinner, 2008). Moreover, the specific resources in rural communities are critical to the mental health and well-being of older adults that live there, particularly in the context of a global pandemic and the more restricted geographies in which many people are living (Herron et al., 2021).

Despite the vulnerability of older adults reflected in both public and academic discourses, some research suggests older adults are faring better in terms of their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic when compared to younger groups. Early quantitative research in countries such as the United States, Canada, and Spain showed lower rates of anxiety, depression, and PTSD among older adults compared to younger age groups during the pandemic (Garcia-Portilla et al., 2020; González-Sanguino et al., 2020; Klaiber et al., 2021). A study of community-dwelling older adults in the Netherlands found that mental health concerns among their sample of 1679 participants did not change before and after the start of the pandemic (van Tilburg et al., 2020). Drawing on a large convenience sample of people aged 18–76 in the USA, Carstensen et al. (2020) found that, compared to younger adults, older adults showed more emotional resilience in the face COVID-19. Another study from the United States, using telephone interviews, found most participants acknowledged that public health restrictions were challenging but they felt they were coping well by keeping busy, reaching out for support, and staying positive (Fuller & Huseth-Zosel, 2021). Although numerous studies from the global north have found that older adults appeared to cope well and experience fewer stress-related mental health problems, other studies have found older adults were more likely to worry and experience loneliness (Rohr, 2020). Certainly, the COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly influenced the quality of older adults’ lives in diverse ways in various places, and it is not over yet. What is important to note is that these larger scale studies suggest many older adults have negotiated resources and strategies to promote well-being during adversity.

Noticing how older adults are managing adversities during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is a critical opportunity to learn about resilience processes. Difficulties adapting and stressful life events that signify increased likelihood of negative outcomes are considered adversities. Resilience is a process that develops in the context of significant adversities and the opportunities for resilience spur from interactions between people and their environments. Resilience is defined as “the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to the psychological, social, cultural, and physical resources that sustain their well-being, and their capacity individually and collectively to negotiate for these resources to be provided and experienced in culturally meaningful ways” (Ungar, 2011, p. 10). How adversities influence outcomes depends on the meaningfulness of opportunities and resources.

The COVID-19 pandemic has produced an array of adversities including severe physical health threats, disruptions to health services, and growing mental health concerns. Despite the popularity of resilience in public and academic discourses during this time, less public and academic attention has been directed to the resilience of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. By overlooking this topic, we risk perpetuating ageist assumptions that misrepresent and devalue older adults and their strengths during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fraser et al., 2020). We also miss opportunities to build environments and systems that enable older adults to thrive.

In this article, we examine resilience processes from the perspective of older rural community-dwelling adults with particular attention to values and contexts that promote resilience. Specifically, we ask, what strategies, resources, and processes do older adults value in rural Manitoba during the COVID-19 pandemic? We draw together research from health geography, gerontology, and developmental psychology, with the aim of advancing the growing body of interdisciplinary research and theory development related to older adults' resilience (Wild et al., 2013; Wiles et al., 2012; Wister et al., 2016).

1. Social ecological resilience, aging, and well-being

As research on resilience in the social sciences continues to develop, complex contextualized social ecological approaches have developed that offer a critical framework for responding to crisis, uncertainty and risk at multiple levels. Although there are many different approaches to resilience, they generally share a focus on processes of persistence, resistance, recovery, adaptation, and transformation during and after adversity (Ungar, 2011, 2021; Masten, 2015). Rather than focus on individual resiliency, social ecological perspectives focus on the “social and physical environment as the locus of resources for personal growth” (Ungar, 2012: 15). Ecological perspectives also recognize the multi-dimensional processes that contribute to resilience. That is, multiple systems or groups of related things (e.g., biological, psychological, social, environmental, and structural) at multiple scales are understood to contribute to resilience. No single system can account for the complexity of processes associated with resilience or the outcome (such as well-being) of that result. In sum, resilience involves navigating and negotiating access to valued resources across a range of settings, systems, and timeframes (Ungar, 2012; Wiles et al., 2012; Windle, 2011).

Some conceptualizations of resilience that promote “bouncing back” as a defining process have been critiqued for suggesting individuals, communities, and healthcare systems can return to normal quickly after traumatic events and adverse experiences (Scott, 2020). Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, critical scholars pointed out that a return to normal may not be desirable, adaptive, equitable, or even possible (Barrios, 2016; Davoudi, 2017). The pandemic has shone a bright light on systemic inequalities and failures in relation to race, gender, and age. As such, scholars such as Scott (2021) continue to advocate for an approach to resilience, which emphasizes transformation rather than a quick return to status quo. Furthermore, Barrios (2016) advocated that resilience approaches must amplify multiple voices, be grounded in local experience, and not be subject to neoliberal ideology. Our approach to resilience responds to these critiques with a focus on the diverse processes and multiple systems that older rural adults say they value during the pandemic.

By focusing on older adults and the multiple resources they value, our research builds on the ongoing interest and debate about the application of resilience in critical gerontology (Harris, 2008; Wild et al., 2013; Wister et al., 2016). In 2008, Harris argued that resilience provides an alternative to dominant stereotypes of older adults as incapable of growth and adaptation while recognizing that adults face adversities throughout their lifecourse that influence their well-being. Following this article, other gerontologists cautioned that resilience can be misused in ways that overemphasize the value of individual assets while failing to account for larger systemic issues and significant disadvantages people face (Katz, 2020; Wild et al., 2013). Consistent with these critiques, studies on resilience in later life have tended to focus most on individual-level protective factors and assets that promote the well-being of older adults, including individual strategies (e.g., self-care, self-acceptance, and positive perspective) as well as social networks (Bolton et al., 2016). Other studies have highlighted the importance of maintaining a positive sense of identity, sense of purpose, and autonomy in adapting to physical limitations and changes to social networks (Browne-Yung et al., 2017; Higgins et al., 2016). These individual level strategies and resources are important, but they must be contextualized (Wiles et al., 2012). Moreover, many studies focus on the behaviors, strategies, social resources, and services (Felton and Hall, 2001; Higgins et al., 2016) that support resilience in later life. Much less attention has been paid to the environmental and culturally specific systems that support resilience processes (for a notable exception see Wiles et al., 2012), and the systems or scales at which these processes interact (Wild et al., 2013). As such, our research seeks to advance contextually sensitive and multi-systemic models of resilience in later life.

2. The case of rural Manitoba, Canada

The context and composition of rural Manitoba make it a compelling case in which to explore processes, resources, and strategies that helped rural older adults in the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Manitoba, 28.8% of the population lives in rural areas and small towns outside of one census metropolitan area, the city of Winnipeg (Statistics Canada, 2016). The province covers a large area (552,370.99 km2), including many remote communities with low population densities, significant distances to urban centres, and variable transportation and communications infrastructure. Since the early 1900s, the region has been shaped by settler colonial migration policies and the development of primary industries (agriculture in the South and resource extraction in the North). More recently, the southern part of the province where the majority of the population lives has been transformed by large-scale capital-intensive farming as well as economic diversification, such as the growth of manufacturing industries including agricultural processing (e.g. ethanol, pork, potatoes, peas) facilities. Demographically, the region includes a large and diverse Indigenous population, European settlers, Anabaptist groups (e.g., Hutterites, Mennonites) and a growing number of newcomers from the global south (Ashton et al., 2016). In 2019, approximately 16 per cent of the population of Manitoba were 65 years and older (Government of Manitoba, 2019) and many rural areas of the province contain a larger proportion of older adults aging in place, consistent with population aging trends in Canada and internationally (Skinner et al., 2021).

Manitoba's response to the COVID-19 pandemic began on March 20, 2020, when it declared a state of emergency and initiated public health measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19 including school closures, closing non-essential businesses, restricting visits to long-term residential care facilities and hospitals, restricting gatherings outside the household, and later requiring all travelers from out of province to quarantine for 14 days. When our study took place, the province was beginning to “restore safe services,” increasing the size of social gatherings (e.g., church, weddings, and funerals) and gradually opening and increasing the capacity of services (e.g., restaurants). During the summer of 2020, the province continued to reduce restrictions; however, COVID-19 cases began to increase throughout Manitoba in August 2020. Our findings focus on participants' experiences of initial restrictions and reopening and do not reflect older adults' experiences as COVID-19 cases increased throughout the rest of 2020 and 2021.

3. Research design

To explore older adults' experiences during the initial stages of COVID-19 we conducted a qualitative case study involving a series of 51 semi-structured telephone interviews with 26 older rural adults from May to August of 2020. A case study research design was best suited for exploring multiple scales of influence related to resilience processes in-depth, with attention to context, and over time (Stake, 1995). In this case study, two telephone interviews were conducted, one month apart, with older adults 65 years and older living in settings with a population of 10,000 people or less (Du Plessis et al., 2002). The inclusion criteria were chosen to focus on a diverse group of older people living in areas with fewer community resources and greater geographic isolation than urban centres.

Upon institutional research ethics approval, 26 participants were recruited for initial telephone interviews through press releases, television and radio interviews, Facebook advertisements, and active living centres for older adults in Manitoba. All participants who responded to recruitment notices met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. Participants’ ages ranged between 65 and 89 years. Many participants identified as women (77%) and were retired (85%); however, four participants were still working part or full-time. Most participants had a high school education (27%) or some postsecondary education (54%); several participants (12%) had less than a high school education and 7% of participants held graduate degrees. Only one quarter of participants lived alone and the remainder lived with a spouse.

After obtaining verbal informed consent from participants, the principal investigator and two research assistants conducted 26 initial telephone interviews over a one month period. The specific questions in the interview guide are reported elsewhere (see Herron et al., 2021). For the purposes of this article, we focused on questions that identified important family, community, social, institutional, and environmental resources and strategies.

Due to the rapidly changing conditions of COVID-19 and public health restrictions, we conducted follow-up interviews one month later with 25 of the original 26 participants. Again, the interview guide asked questions about valued resources as well as changes since the last interview and what strengths and challenges participants experienced living in a rural community during this time. The follow up interviews also allowed the researchers the opportunity to clarify and prompt for further details about participants’ experiences. All interviews for the study were digitally recorded and lasted between 30 and 90 min, with most interviews lasting an hour.

Interview transcripts were coded, as interviews were being conducted, using NVivo 12 software. Three researchers inductively coded the first transcript line-by-line with a focus on participant experiences and voices (Charmaz, 2014). The primary researcher continued to code transcripts independently. On a weekly basis, the three researchers met to code a new transcript, review the codebook, discuss divergent interpretations of the data, come to a consensus on codes, and then to develop the themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006). This process of regular coding meetings as a team enhanced the credibility and confirmability of analysis by ensuring that interpretations were reviewed and confirmed by multiple researchers who were directly involved in the interviews. In the second round of interviews, the researchers continued inductive line-by-line coding developing a separate codebook. During weekly meetings, the researchers compared the first and second codebook and coded a new transcript from the second set of interviews together. Once all interviews were coded, the researchers deductively categorized the initial themes from both the first and second interviews guided by Ungar's (2021) multi-systemic social ecological resilience framework. This involved grouping resources and strategies older adults valued into an organizing table to identify similar resources and strategies at different levels (e.g., individual, environmental, and community). Initially, codes were colour-coded based on whether they came from the first, second or both interviews. This process allowed the research team to verify that resources and strategies were relatively consistent across both interviews. The findings in this article are a representation of common individual, environmental, community, institutional, and societal resources that supported (or sometimes were not available to) older rural adults. Participant quotations from both sets of interviews are used to illustrate these resources and strategies. All participant names have been replaced with pseudonyms.

4. Findings

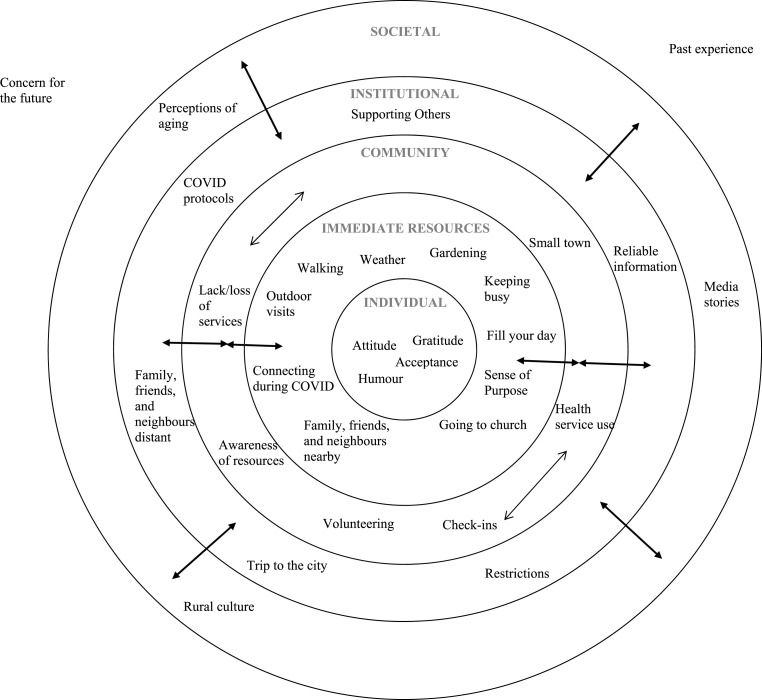

The findings are organized according to a systemic understanding of resilience. Social ecological resilience reflects multiple systems that are theoretically “a complex whole” comprised of multiple and interacting scales (Ungar, 2021). We describe the research findings as interacting and layered processes beginning with individual-level expanding to societal influences. While we discuss the scales in a separate manner to provide insight into clear patterns of resilience, we emphasize the complex interaction between systems for people in their environments. We begin by reporting on individual strategies such as positive thinking, acceptance, and gratitude, which older adults suggested promoted their well-being. We then link these strategies to older adults’ immediate social and physical environment including opportunities to keep busy, connect with friends, family and neighbours, and visit outdoors. As we progress through the findings, we identify broader systems influencing older adult well-being including access to health services, opportunities to volunteer and support others, access to reliable information, public health policies and practices that value older adult lives, and media stories. See Fig. 1 for a depiction of the findings.

Fig. 1.

A multi-systemic framework of later life resilience.

5. Individual resources and strategies: positivity, acceptance, and gratitude

Many participants talked about the importance of their attitude, thinking, and ways to “stay as positive as possible” (Aubrey, First interview). In doing so, they revealed various self-talk strategies they used to address feelings of isolation, loneliness, and feeling low or depressed. For example, Matilda explained:

“There were a couple of days where I was quite, um, [voice shaky, audible crying] emotional and I knew I was, you know, not clinically depressed but, just a real down couple of days. I knew I really had no reason to be. I was, you know, I have a nice house, a fridge, freezer full of food. Um, I was warm, I was comfortable. I have books to read. Um, there wasn’t really any reason not to be, or to be. I just found that hard … But, I just kind of, you know, you give yourself a little pep talk and say “You have no reason to be” (First interview).

Matilda indicated that she felt more isolated and lonely than she did before the pandemic and she explained that staying positive was not simply a matter of attitude, it involved appreciating the material resources she had within her home and rural environment and using those resources in her self-talk. In addition, some participants drew on their past experiences and faith systems to stay positive. For example, Evelyn explained:

“I’ve repeatedly said, ‘we will overcome this.’ That I believe in a power greater than, than, than the virus, like. Because of my life and what has happened in my life, I know that not too nice things don’t win” (First interview).

Evelyn described having experienced domestic abuse and financial insecurity throughout her life and she used faith to help her think positively about the future during challenging times. Her strategies highlight the links between individual coping, past experiences, and institutional resources (i.e., church).

In discussing their individual approaches to managing adversity, many participants revealed the importance of accepting difficult circumstances and at the same time expressing gratitude in order to stay positive. Ava described her process, saying “I think with myself, just, making up my mind that's the way things are and, and I better, you know, enjoy what I have got” (Second interview). Shirley explained that she found acceptance through talking with others: “I had people to talk to every day. And we just talked about the situations and said, ‘well, that's the way it is, we will just deal with it’” (Second interview). Other participants also described feelings of acceptance and gratitude in relation to their social and physical environments. Alice, who was recently divorced and described continued conflict with her ex-husband, explained, “I just feel, [deep breath out] relieved to be in my house … This is it; this is life and I'm thankful for it. And I'm thankful for my situation” (First interview). In contrast, George resigned himself to the situation, saying “I guess because you're locked up in your room, you can't do much other than go for a walk. And when you get really old, you can't walk too far, so you just put up with what you have and accept it” (Second interview). Notably, this participant lived in an apartment building for older adults in a small community. He had less space and more mobility limitations than other older adults in the study, which both contributed to his sense of being “locked-up.” Nonetheless, over time, he accepted what he could do in his circumstances, which included opportunities to go out to his daughter's farm. Having something to do was a critical strategy for many participants.

6. Valued resources close to home: keeping busy; friends, family and neighbours; outdoor visits

Participants identified “keeping busy” or “filling the day” as strategies for maintaining their well-being. For example, Matilda explained: “We have a large yard and garden and you know, flowers and stuff. So I think we are more, we're busier and that tends to take your mind off your problems” (First interview). Gardening and walking were common activities among most of the participants. They described these activities as offering an opportunity to get out of the house, as well as providing them with a sense of purpose and gratitude. As another example, feeding the birds was described as a “full-time job” and some participants grew plants to sell or share with friends and family. Other participants talked about watching wildlife and livestock, further highlighting specific rural resources contributing to the well-being of older adults. Many participants described doing household chores and cleaning as an important strategy to fill their day with purpose. Some of these participants lived in apartments designed for older adults without gardens or outdoor spaces; nonetheless, they spoke of cleaning and reorganizing their belongings as a process that helped them. For example, Shirley said “I keep my home looking lovely. And if you had called in, I would be happy to have you” (First interview). Although public health restrictions prohibited having people in, it was important to this participant to maintain a sense of pride and purpose in keeping her home lovely.

Participants identified family, friends, and neighbours as immediate social resources that supported their well-being during the initial stages of the pandemic. For example, Alice, who lived alone explained that her son checked in on her and brought her food: “He would be cooking up something special, it didn't have to be special, but he would bring supper over for me [soft laugh]” (First interview). Other older adults explained how they relied on mutually supportive friendships. Jody said,

“… I’ve got one very, very special friend. And, uh, even before COVID came we talked every night because she’s by herself and, uh, she landed up in the hospital and I didn’t know about it. And, so, I have called her every night for many years. And, I still do” (First interview).

Some people identified a “loving partner” (Cheryl, Second interview) as an important resource and most participants who lived alone identified having someone who was both physically and emotionally close to talk with, share their experiences with, and share tangible resources such as food.

Although participants identified close family, friends and neighbours, not everyone felt they had the social support they needed. Helen explained, “Yah she [daughter] texts me and asks me how I'm doing. Yeah, and she comes to town, she comes to town quite often but she never calls to see how I am. It's just, you know, I miss that” (First interview). Helen described herself as very lonely. She not only lacked the support she desired from her daughter, she also felt that others in her apartment did not want to talk with her. Similarly, Evelyn lacked social, emotional, and tangible support at home. She explained “there's really nobody; ” (First interview) her children lived in other provinces and she was a caregiver to her husband who lived with dementia. She identified herself as struggling with loneliness and depression, since the drop-in centre her husband visited before the pandemic had closed. She was frustrated that nobody had thought to phone them and check in on him. Her experiences highlight the important connection among mental health, social resources, and community resources.

Despite challenges, participants identified strategies for maintaining social relationships and exchanging resources within their immediate environments through outdoor visits on decks, driveways, and roadways. For example, Jack explained,

“… We make a point of phoning somebody up and saying, ‘bring a lunch over, we are going to sit on the driveway.’ Or, you know, ‘bring your own, bring your own cup of tea, or whatever you want to bring. We don’t care what you drink. Just either come to our driveway or we will come to your driveway.’ Or deck, depending on what they have. We make an effort of connecting with people” (First interview).

Participants described different features of their environment that supported physically distanced encounters, including the type of neighbourhood they lived in, where they were located on the road and the features of their property. For example, Ava said:

“… I also live right on, ah, you know, a corner, like right close to the street. So, when people walk by they stop and talk or they come and pound on my kitchen window and let me know, yeah, so. Yeah, no, it’s been, people have been wonderful with me, and I think, being by myself, they have been even, some of the neighbours have even been nicer. Like, when it first started up one neighbour brought me over a beautiful plant and a card, you know, with their phone number in case I needed anything. And, people have said oh you are there all by yourself, but really it hasn’t been that bad.” (First interview).

Later, during the interview, she also talked about the importance of having a deck to sit on. Similarly, other participants talked about how sitting on their deck allowed them to interact with others walking by and get out of the house. Another participant explained, “We spend a lot of time standing in our window, enjoying, watching these children play” (Iris, First interview). Moreover, participants identified organized outdoor visits as well as spontaneous outdoor encounters as an important adaptive process in maintaining their well-being and their built environment facilitated these processes.

7. Community resources and strategies: organizations, businesses, routines, and rituals

Many participants described the role of community social organizations (e.g., Red Hatters, Crown Jewels, and Women's Institute) in facilitating different forms of social support, particularly among women. For example, when describing friends in her community, Aubrey explained, “I have a lot of friends, because I belong to Red Hatters” (First interview) an organization initially founded for women over 50 to provide social interaction and develop friendships. Other women belonged to similar organizations such as the Crown Jewels; Evelyn described the groups saying “we wear our red and white colors, or purple and we deck all up in all kinds of fancy jewelry and we sit there and we have fun … It is, it's a good group and uh, every month one person out of the group is, is to host an event. So, this time, being that we could do it outside in the fresh air, we did have an event.” (First interview). Participants explained that they continued to stay connected with members of social organizations and some arranged outdoor activities as the pandemic went on. Importantly, some women described their immediate social support as a product of much larger national and international non-profit organizations to which they belonged.

Some participants described the role of age-specific and cultural organizations in providing reassurance and tangible support during the pandemic. For example, in her first interview Hannah explained, “I belong to the senior's group and the last membership with them it was around 15–20. Now that wasn't, like, that's not close, close friendships or anything like that, but certainly I would feel that I could call on them if I had to.” (First interview). Other participants continued to receive meals from community active living centres as well as phone calls to check in on them. In addition, some participants identified cultural organizations offering them support. For example, Vera said, “So, I was very fortunate. I also received two hampers from the MMF [The Manitoba Metis Federation] … yeah, and they had some outreach to seniors, and I was really, really blessed to a have a couple of hampers. Which helped for groceries and things” (First interview). Moreover, many participants described themselves as being integrated into various geographic, social and cultural communities, which they continued to contribute to and these communities also provided support for them.

Several participants remarked on the actions of small businesses in their community that made them feel cared for. For example, Nora, who lived with a complex chronic condition, said, “store owners sent emails, it's like, “If you need bread, milk, anything, let us know and we will leave it on your doorstep” (First interview). In another community, one participant received a note from her local post office which read:

“Hello there [name], just us gals at the post office sending you a little note to wish you well. We're missing some of our customers that are especially delightful and decided to reach out by sending a note. We hope you're healthy and keeping active and that you're finding joy in each day. Bless you. [name] and the staff at the post office” (Shirley, First interview)

The latter example is particularly notable as the post office staff recognized the important social space the post office provided in the community and reached out to older adults who benefitted from the social engagement opportunities the post office provided.

Other participants remarked that their sense of community had changed precisely because access to, and routines in, community spaces had changed:

“It has changed because people are, half your visiting, as you know, might be done at the Co-Op when you go to buy groceries, you can spend twice the time in there because you just talked to three people. So, none of that is happening, and the best we can do is kind of nod at each other cause they don’t want to see us visiting anywhere. The, um, same at the post office, another community hangout. That’s not available to us. You can’t meet someone and say let’s go out for coffee. So that’s gone” (Gerta, First interview).

In addition to changes in social encounters within these community spaces, some participants also mentioned how restrictions on funerals (e.g., closure of funeral homes and/or reduced number of people allowed to attend funerals) were affecting their sense of community. Joann explained,

“we’ve also had a few people who have passed away, and of course, they haven’t been able to have a funeral, and closure for the community at all, so that also, I guess that has been a real challenge because in a small community everybody knows each other, so it’s not only the person’s spouse who, who needs closure, but the community itself needs closure” (First interview).

Participants commented on the loss of community support and rituals in relation to grieving because of COVID-19 restrictions, including funerals, providing food for grieving families, and not being able to have physical contact with the bereaved. The participants’ experiences of community change underscore the interaction of institutional processes such as public health protocols with local community strategies for coping with loss and adversity.

8. Institutional resources and strategies: health service use, supporting others and volunteering

Although strategies and resources within participants’ immediate environment were most abundant, participants reflected on broader systems and how these systems influenced their individual strategies and resources, including access to health services, the advice of doctors, the workplace of their social relations, decisions of the school system, and the education and childcare needs of grandchildren.

Participants who were experiencing pain and uncertainty while awaiting medical procedures reported poorer mental health, while others living with managed chronic conditions reported greater acceptance, comfort, and overall well-being. Maria explained, “if you have health issues, it's making this, um, pandemic a lot worse. I think cause, um, well you know, you're always conscious about, well you have to isolate and things like that, so I hadn't realized the impact of, uh, being in pain had on my entire outlook of the pandemic” (Second interview). The well-being of participants with acute health conditions was influenced by their access to health services as well as timely and relevant information about how to manage their condition while awaiting further care.

In some cases, participants reported that their contact with family and friends was also influenced by the advice of doctors and/or their health conditions. For example, Jody said, “under the advice of the doctors we did not see our granddaughters for, uh, three months” (Second interview). In contrast, other participants cared for grandchildren when schools first closed. In her second interview, Danielle explained,

“I babysit for my son and his wife every 6 weeks. They come out for the weekend, because they both work the same shift. And with schools opening, I’m diabetic, I now have COPD, um, I have high blood pressure and a heart problem, so I’m not going to be able to look after them anymore, if they go back to school.”

The latter example highlights the interaction between the decisions of different institutions (i.e., health and education) and their influence on older adults' health and social well-being.

Other participants discussed the challenges of negotiating contact with friends and family and the role of older adults in supporting the education of their grandchildren. Gerta said,

“If we see our grandchildren, we can’t really see our friends. So that has been very awkward. Some of my friends are actually ex-teachers so they have been tutoring their grandchildren, or babysitting them and, their children don’t want them to do anything but that, don’t go anywhere, don’t see anybody, don’t bring this disease to your grandchildren. So, that’s sort of the other side of the coin. Protecting the elderly, no, it’s the elderly protecting the young” (Second interview).

Participants revealed the complexity of navigating who they could see in person as well as their role in supporting and augmenting social systems such as education and childcare.

In many ways, participants contributed to the social welfare of others in their community through their volunteer work and association with various non-profit organizations. In the first set of interviews, half of participants identified a loss of volunteer activities as a challenge during the initial stages of the pandemic; however, during the second round of interviews, some participants were able to resume different types of volunteer work independently or with one other person. Ava said,

“I’m going to start delivering meals, and I did a medical run [as part of a volunteer driver program to help older adults get to appointments] … when I do medicals, I try and make it pleasant for them, too. If there’s anything they want to do. And the other day, this gentleman wanted to stay, or after have lunch before we go. And wanted to go to do grocery shopping.” (Second interview).

Although some participants still experienced barriers to volunteering and contributing to their community and institutions, some older adults not only negotiated resources to promote their own well-being, but they also supported the well-being of other groups and organizations, by providing transportation to medical appointments and groceries. In doing so, they demonstrated their role as agents of resilience and not just recipients of care.

9. Societal influences: media stories, reliable information, and policies that value older adult lives

Some participants indicated that media stories contributed to feelings of worry, depression, and loneliness and as result they decided to limit their exposure to the news. In particular, when asked about feelings of depression and loneliness, some participants responded with comments about the negative influence of the news; Hannah said “It's not the virus so much as just, well I, if I would just quit watching the news” (First interview) and Jody said “I feel a lot less isolated in some ways if I could persuade myself to stay off Yahoo news” (Second interview). Similarly, Iris stated “I also learned early on … If you wanted to cope well, one of the things that you need to do is very, very explicitly is limit your exposure to the news” (Second interview). Participants expressed an awareness of media influences on their well-being as well as strategies for remaining informed without exacerbating feelings of worry or anxiety.

Participants identified the importance of clear protocols, reliable information, and public health measures that made them feel valued at provincial and national levels. When asked about the influence of provincial and national public health restrictions on their lives, most participants explained that they had learned and adapted to wearing masks, sanitizing, and maintaining physical distance with people outside their household or designated contacts. When Hannah was asked what helped most during COVID-19, she stated:

“… excellent medical knowledge on how best to, to carry out your affairs, with, you know, the washing of hands, the social distancing, the masks, umm, and being really careful not to be in close proximity to different people. I’ve been making masks for people as well, for those who want them and feel that they would be of use. That would be primarily knowledge that is imparted from Health Canada … we’ve listened, we have learned, and we adhere” (Second interview).

Another participant reflected on the importance of protocols and subsequent actions that made her feel valued. Vera explained:

“People were being obedient and caring about each other. I think that’s a major thing that has impressed me. Is, I am so grateful, so grateful to be in a society that is willing to sacrifice like this to be able to safeguard, especially the vulnerable, those that are vulnerable to COVID. And that is, of course, I am in that category” (First interview).

Some participants resisted and even opposed being characterized as vulnerable but they appreciated the care that individuals, communities, organizations, and governments took to ensure their safety and well-being.

10. Discussion

In this article, we examined the strategies, resources, and processes that older adults living in rural communities in Manitoba, Canada valued during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, we aimed to advance research related to older adults’ resilience with particular attention to the contexts and systems that promote resilience (Wiles et al., 2012; Ungar, 2021). Fig. 1 illustrates a multi-systemic conceptual framework of later life resilience based on the voices of older adults involved in this study that extends resilience from individual assets to broader systemic dimensions (Katz, 2020; Wild, 2013). This framework offers an integrated and contextualized approach to understanding resilience, illustrating how individual-level processes are influenced by multiple dynamic systems surrounding older adults including their immediate environment, broader communities, institutions, and societal influences.

Results highlight the cognitive and emotional strategies that older adults used to cope and how these strategies are embedded within the larger social context. Cognitive strategies, such as positive thinking, optimism, acceptance, and gratitude are important in understanding older adults' resilience and our findings support extensive past research on older adults' emotional regulation capacities (Carstensen et al., 2020), individual strategies (Bolton et al., 2016), and their implications for mental health (Carr, 2018). In addition, participants' narratives clearly illustrate how these individual competencies are embedded in the material, physical, and social environments in which older adults live, supporting the work of Wiles and colleagues (2012). For example, keeping busy or filling your day is possible for older adults who live in environments that offer opportunities to walk, garden, read, or volunteer. Similarly, access to outdoor spaces within rural settings enabled many older adults to maintain their social relationships at a physical distance and adapt their social practices to meet their need for meaningful connection with friends and family, provided they lived nearby. These findings further contextualize Fuller and Huseth-Zosel's (2021) observations that many older adults are “coping well” by keeping busy, reaching out, and staying positive.

Importantly, not all older adults in the study had access to the resources they valued to maintain their well-being within their immediate rural environments. For example, some women lived alone or were socially isolated due to their caregiving responsibilities. Many of these women made use of local/national social organizations to fill their social needs. Their membership in these social organizations predated COVID-19 and demonstrates a positive substitution (where meaningful social support was lacking at home and local organizations filled that need) as well as persistence (where this need continued to be met through the relationships and meanings associated with these social organizations). Moreover, when valued resources are lacking in one system, other systems can help compensate for this lack of resources, provided that older adults have access to these systems and they offer relevant support.

Within the rural communities in which older adults lived, some businesses, services, and cultural groups provided valued resources that continued to enhance the well-being of older adults during the pandemic, including providing reassurance, check-ins, and food. In addition, participants noted changes to community routines and rituals in relation to grieving because of restrictions on funerals. There was little mention, however, of specific adaptive strategies to cope with these losses, raising questions about how these needs will be met. Future research must continue to investigate the changing dynamics, routines, and rituals of rural communities as COVID-19 continues as well as their implications for the well-being of older adults.

Results also highlight how resilience among older adults during the pandemic involved an interplay between being both helped by –as well as contributing to—families, communities, and institutions. Consistent with research by Wiles and Jayasinha (2013), older adults in the study were actively involved in caring for others and contributing to the resources available in their families, communities, and institutions. In doing so, they resisted characterizations of older adults as vulnerable and in need of protection (Chivers, 2020; Wiles, 2011). In fact, in several cases the caring work and volunteering of older adults in the study compensated for institutional changes (e.g., helping their families with providing at home learning for children) and infrastructure gaps (e.g., lack of transportation services such as public transit or taxis). These processes of resistance highlight the agency, values, contributions, and connectedness of older adults. It is important to note that negotiating safe opportunities to contribute was challenging for some older adults as some of the systems to which they previously contributed were not responsive or adaptive in ways that promoted their safety during COVID-19 (e.g., older adults noted they could no longer volunteer in schools, palliative care, or more communal settings). In comparison to the broad range of resources older adults identified in their immediate environment, there were certainly fewer resources in older adults communities and institutions as well as greater impediments to accessing resources (e.g., health services and education); this is consistent with neoliberal policies, which promote individual resourcefulness. However, our findings point to opportunities for public systems such as health and education to become more responsive and age-friendly to better support the resilience of older adults.

At a societal level, media stories, medical knowledge, and public health policies and practices influenced older adults’ resilience and well-being. Consistent with other research during COVID-19 (Kizilkurt et al., 2020), older adults indicated that media stories sometimes adversely affected their wellbeing; however, they learned to limit their consumption of media and find relevant and reliable information that fit their skills and context (e.g., sewing masks).

Results also highlight how the broader social views of the pandemic and the ideas of ‘caring for others’ were felt positively at an individual level by older adults. For example, at the time of the interviews, some older adults noted the value of public health policies and practices that seek to protect older adults as a “vulnerable group.” Although some older adults resisted being characterized as vulnerable, they valued the care that others took to protect their lives and that it seemed that others cared about their well-being. Although this view and feeling might be temporary, the impact and processes of achieving this effect are certainly worth noting. When multiple levels of government, businesses, community organizations, families and individuals work together to promote the well-being of older adults, it can have a significant impact on how they feel.

Understanding the processes that contributed to the resilience of older adults in the study can guide future policies and programs that promote resilience and enable older adults to thrive. Multi-level approaches are needed to effectively enhance resilience and sustained well-being over time. Our study emphasizes the importance of making a broad range of multi-level resources available and accessible that are valued and contextually relevant to promote resilience (e.g., accessible to outdoor gathering spaces, inclusive social and cultural organizations for older adults at the community level, businesses that recognize the diverse and distinct needs of older community members, safe volunteer opportunities to contribute to community welfare, and relevant and reliable public health information that recognizes the diverse capacities of older adults). Moreover, our findings illustrate the many actors, including older adults themselves, are required to develop such practices across levels.

A key strength of our study is our focus on rural older adults, who have received much less attention in research on COVID-19 and resilience. In addition, repeated interviews enabled us to develop rapport and collect rich descriptive data; however, our study is not without limitations. First, in the summer of 2020, we could not have anticipated the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic; as such, we conducted interviews only one month apart. Clearly, more longitudinal research is needed to explore processes of persistence, resistance, recovery, adaptation and transformation in the long term. For example, how will systems continue to evolve and influence the well-being of older adults? Another limitation of our research is that more women than men participated in interviews and few participants self-identified as racialized or Indigenous. Future research should continue to explore the broad range of resources and strategies that are relevant to diverse older adults. Furthermore, research is needed explore how transformations during COVID-19 influence pre-existing inequalities in later life. Drawing on a multi-systemic framework, future research should also consider perspectives of stakeholders from different community and institutional systems. Other stakeholders’ perspectives might enrich understandings of different systemic challenges and opportunities to promoting well-being.

11. Conclusion

We have learned from older adults living in rural Manitoba during the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic that older adults can be vulnerable and also negotiate resilience when a broad range of relevant resources are available and accessible to promote their well-being. Older adults in the study identified many resources within their immediate rural environments that supported their individual cognitive strategies and contributed to their well-being. They also identified the critical role of community organizations, institutions, and governments in promoting the well-being of older adults in general as well as compensating for a lack of resources at home. Most importantly, what this moment during COVID-19 teaches us is that multi-level policies and practices that demand care and consideration of the lives of older adults can have far-reaching consequences on older adults’ well-being.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arentz M., Yim E., Klaff L. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically Ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington state. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton W., Galatsanou E., Miller Cronkrite M., Pettigrew R. Rural Development Institute; Brandon, MB: 2016. Immigration in 5 Rural Manitoba Communities with a Focus on Refugees. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios Resilience: a commentary from the vantage point of anthropology. Ann. Anthropol. Pract. 2016;40(1):28–38. doi: 10.1111/napa.12085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton K.W., Praetorius R.T., Smith-Osborne A. Resilience protective factors in an older adult population: a qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis. Soc. Work. Res. 2016;40(3):171–182. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browne-Yung K., Walker R.B., Luszcz M.A. An examination of resilience and coping in the oldest old using life narrative method. Gerontol. 2017;57(2):282–291. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnv137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (C.I.H.I . CIHI; Ottawa, ON: 2020. Pandemic Experience in the Long-Term Care Sector: How Does Canada Compare with Other Countries?https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/covid-19-rapid-response-long-term-care-snapshot-en.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. Mental health of older widows and widowers: which coping strategies are most protective. Aging Ment. Health. 2018;24(2):291–299. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1531381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L.L., Shavit Y.Z., Barnes J.T. Age advantages in emotional experience persist even under threat from the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sci. 2020;31:1374–1385. doi: 10.1177/0956797620967261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz . second ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, California: 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Chivers S. How we rely on older adults, especially during the coronavirus pandemic. Conversation. 2020 https://theconversation.com/how-we-rely-on-older-adults-especially-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi S. In: Governing for Resilience in Vulnerable Places. Trell E.M., Restemeyer B., Bakema M.M., van Hoven B., editors. Routledge; New York: 2017. Self-reliant resiliency and neoliberal mentality: a critical refection; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis V., Beshiri R., Bollman R.D., Clemson H. Definitions of rural. Agric. Rural Work. Pap. Ser. 2002;61:1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Felton B.S., Hall J.M. Conceptualizing resilience in women older than 85: overcoming adversity from loss or illness. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2001;27(11):46–53. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20011101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Lagacé M., Bongué B., Ndeye N., Guyot J., Bechard L., Garcia L., Taler V., Adam S., Beaulieu M., Bergeron C.D., Boudjemadi V., Desmette D., Donizzetti A.R., Éthier S., Garon S., Gillis M., Levasseur M., Lortie-Lussier M., et al. Ageism and COVID-19: what does our society's response say about us? Age Ageing. 2020;49(5):692–695. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller H.R., Huseth-Zosel A. Lessons in resilience: initial coping among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontol. 2021;61(1):114–125. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Portilla P., de la Fuente Tomas L., Bobes-Bascaran T., Jimenez Trevino L., Zurron Madera P., Suarez Alvarez M., Menendez Miranda I., Garcia Alvarez L., Saiz Martinez P.A., Bobes J. Are older adults also at higher psychological risk from COVID-19? Aging Ment. Health. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1805723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanguino C., Ausín B., Castellanos M.Á., Saiz J., López-Gómez A., Ugidos C., Muñoz M. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:172–176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada Vulnerable populations and COVID-19. 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/vulnerable-populations-covid-19.html Available online:

- Government of Manitoba Age-friendly Manitoba initiative. 2019. https://www.gov.mb.ca/seniors/afmb Retrieved from.

- Harris P.B. Another wrinkle in the debate about successful aging: the undervalued concept of resilience and the lived experience of Dementia. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2008;67(1):43–61. doi: 10.2190/AG.67.1.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herron R., Newall N.E.G., Lawrence B.C., Ramsey D., Waddell C.M., Dauphinais J. Conversations in times of isolation: exploring rural-dwelling older adults' experiences of isolation and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic in Manitoba, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18:1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins A., Sharek D., Glacken M. Building resilience in the face of adversity: navigation processes used by older Lesbians, Gay, bisexual and transgender adults living in Ireland. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016;25(23–24):3652–3664. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph A.E., Cloutier-Fisher D. In: Ageing and Place. Andrews Gavin J., Phillips David R., editors. Routledge; 2004. Ageing in rural communities: vulnerable people in vulnerable places; pp. 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Katz S. In: Precarity and Ageing: Understanding Insecurity And Risk In Later Life (41 – 65) Grenier A., Phillipson C., Settersten R. Jr., editors. Bristol University Press; Bristol: 2020. Precarious life, human development and the life course: critical intersections. [Google Scholar]

- Keating N., Swindle J., Fletcher S. Aging in rural Canada: a retrospective and review. Can. J. Aging. 2011;30(3):323–338. doi: 10.1017/S0714980811000250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizilkurt O.K., Yilmaz A., Noyan C.O., Dilbaz N. Health anxiety during the early phases of COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey and its relationship with postpandemic attitudes, hopelessness, and psychological resilience. Psychiatr. Care. 2020;57:399–407. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaiber P., Wen J.H., DeLongis A., Sin N.L. The ups and downs of daily life during COVID-19: age differences in affect, stress, and positive events. J. Gerontol.: Ser. B. 2021;76(2):e30–e37. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A.S. Pathways to integrated resilience science. Psychol. Inq. 2015;26:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan T., Wiles J., Williams L., Gott M. COVID-19 and the portrayal of older people in New Zealand news media. J. Roy. Soc. N. Z. 2021;51:S127–S142. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2021.1884098. sup.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- PHAC . 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology Update.https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Rohr S. Mental wellbeing in the German old age population largely unaltered during COVID-19 lockdown: results of a representative study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01889-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott M. COVID-19, place-making and health. Plann. Theor. Pract. 2020;21:343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Scott M. In: COVID-19 and Similar Futures, Global Perspectives on Health Geography. Andrews G.J., Crooks V.A., Pearce J.R., Messina J.P., editors. Springer Nature; Switzerland: 2021. Resilience, risk, and policymaking; pp. 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner Voluntarism and long-term care in the countryside: the paradox of a threadbare sector. Can. Geogr. 2008;52(2):188–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0064.2008.00208.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner M., Winterton R., Walsh K. In: Rural Gerontology: towards Critical Perspectives on Rural Ageing. Skinner M., Winterton R., Walsh K., editors. Routledge; 2021. Introducing rural gerontology; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stake R. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada . 2016. Manitoba: Focus on Geography Series.https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-pr-eng.cfm?Lang=Eng&GK=PR&GC=46&TOPIC=1 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. The social ecology of resilience: addressing contextual and cultural ambiguity of a nascent construct. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(1):1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. In: The Social Ecology of Resilience. Ungar M., editor. Springer; New York, NY: 2012. Social ecologies and their contribution to resilience; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M. Oxford University Press; New York: 2021. Multisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change. [Google Scholar]

- van Tilburg T.G., Steinmetz S., Stolte E., van der Roest H., de Vries D.H. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study among Dutch older adults. J. Gerontol.: Soc. Sci. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, O'Shea E., Scharf T. Ageing & Society; 2020. pp. 1–27. (Rural Old-Age Social Exclusion: a Conceptual Framework on Mediators of Exclusion across the Lifecourse). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wild K., Wiles J.L., Allen R.E.S. Resilience: thoughts on the value of the concept for critical gerontology. Ageing Soc. 2013;33:137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles J. Reflections on being a recipient of care: vexing the concept of vulnerability. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2011;12(6):573–588. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2011.601237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles J.L., Jayasinha R. Care for place: the contributions older people make to their communities. J. Aging Stud. 2013;27(2):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles J.L., Wild K., Kerse N., Allen R.E.S. Resilience from the point of view of older adults: ‘there's still life beyond a funny knee. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;74:416–424. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle G. What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Rev. Clin. Gerontol. 2011;21:152–169. doi: 10.1017/S0959259810000420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wister A.V., Coatta K.L., Schuurman N., Lear S.A., Rosin M., MacKey D. A lifecourse model of multimorbidity resilience: theoretical and research developments. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2016;82(4):290–313. doi: 10.1177/0091415016641686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]