Abstract

Emerging new variants of SARS-CoV-2 and inevitable acquired drug resistance call for the continued search of new pharmacological targets to fight the potentially fatal infection. Here, we describe the mechanisms by which the E protein of SARS-CoV-2 hijacks the human transcriptional regulator BRD4. We found that SARS-CoV-2 E is acetylated in vivo and co-immunoprecipitates with BRD4 in human cells. Bromodomains (BDs) of BRD4 bind to the C-terminus of the E protein, acetylated by human acetyltransferase p300, whereas the ET domain of BRD4 recognizes the unmodified motif of the E protein. Inhibitors of BRD4 BDs, JQ1 or OTX015, decrease SARS-CoV-2 infectivity in lung bronchial epithelial cells, indicating that the acetyllysine binding function of BDs is necessary for the virus fitness and that BRD4 represents a potential anti-COVID-19 target. Our findings provide insight into molecular mechanisms that contribute to SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and shed light on a new strategy to block SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, envelope E protein, BRD4, bromodomain, ET domain

Graphical abstract

SARS-CoV-2 virus uses host molecular programs for viral replication and survival in infected cells. Vann et al. identified mechanisms by which the E protein of SARS-CoV-2 interacts with the human transcriptional regulator BRD4.

Introduction

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) continues posing an immense threat to public health. This pathogen causes severe respiratory distress and pneumonia and has led to the disastrous viral infection pandemic with morbidity reaching 305 million as of January 2022. SARS-CoV-2 relates to other beta-coronaviruses SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, which triggered outbreaks in 2002 and 2012 and have similar genomes and host cell entry mechanisms. The ∼30-kb single-stranded RNA genome of SARS-CoV-2 encodes four structural proteins, spike (S), envelope (E), nucleocapsid (N), and membrane (M), all of which are involved in multiple aspects of the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle, including the virion particle assembly, viral entry, fusion of viral and host cell membranes, and the virus replication (Li et al., 2021). The E protein of SARS-CoV-2 is the smallest structural protein, containing only 75 amino acids. Although it remains poorly characterized, homologous SARS-CoV E has been shown to play a vital role in virus production, maturation, and budding (DeDiego et al., 2007; Schoeman and Fielding, 2019). The amino-terminal transmembrane domain of SARS-CoV E can oligomerize, forming the ion-conductive pores in membranes (Nieto-Torres et al., 2014; Schoeman and Fielding, 2019; Verdia-Baguena et al., 2012). Deletion of SARS-CoV E diminishes virus virulence, and immunization of mice with recombinant SARS-CoV lacking the E protein was found to protect the mice against lethal disease, demonstrating that the E protein is an essential virulence factor (Netland et al., 2010).

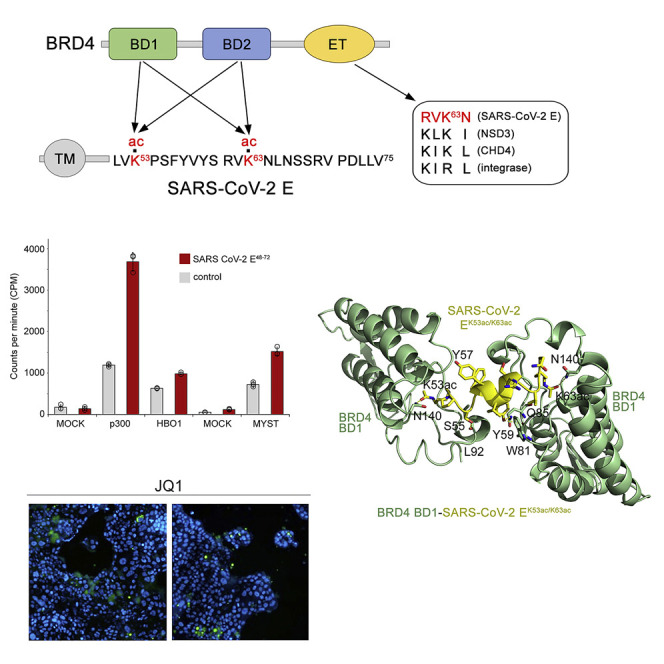

Affinity-purification mass spectrometry analysis has identified over 300 high-confidence interactions between human proteins and the SARS-CoV-2 proteins (Gordon et al., 2020). Among them are the SARS-CoV-2 E protein and human bromodomain and extra-terminal domain (BET) proteins BRD2 and BRD4. Of the four members of the BET family proteins, BRD4 has received considerable attention as a pharmacological target for the treatment of a wide array of human diseases (Filippakopoulos and Knapp, 2014; Lambert et al., 2019). BRD4 contains two tandem bromodomains (BDs), bromodomain 1 (BD1) and bromodomain (BD2), which bind to acetylated lysine residues, and the extra-terminal (ET) domain, which recognizes the KhKh (h; hydrophobic residue) motif found in LANA, CHD4, and NSDs (Zhang et al., 2016) (Figure 1A). BRD4 BD1 is primarily known to interact with acetylated histones, such as poly-acetylated histone H4, whereas BRD4 BD2 also associates with acetylated non-histone proteins (Shi et al., 2014). Both interactions help recruit BRD4-containing transcription complexes to promoters of target genes and are linked to active gene transcription (Filippakopoulos et al., 2012). The basis of the potential link between BRD4 and the E protein of SARS-CoV-2 remains undetermined.

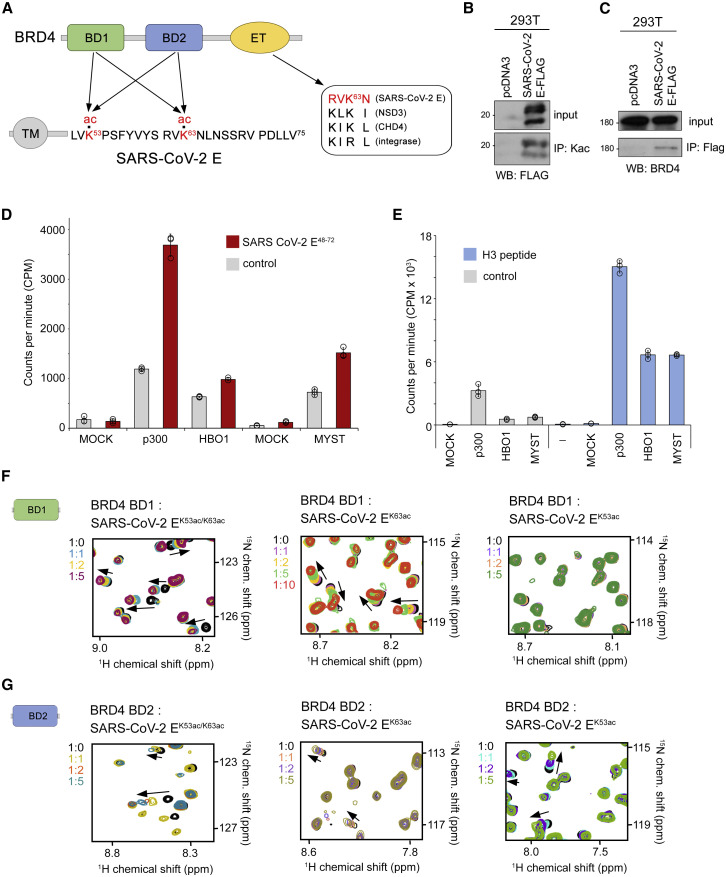

Figure 1.

SARS-CoV-2 E protein is acetylated in vivo and interacts with BRD4

(A) Domain architecture of BRD4 (top) and the SARS-CoV-2 E protein (bottom). Sequence alignment of the motif present in the E protein and other proteins known to interact with the BRD4 ET domain is shown on the right. Arrows indicate potential contacts between BRD4 and the E protein. Acetylated lysine residues are highlighted red.

(B) Immunoprecipitation with anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies on whole cell extracts from 293T cells expressing FLAG-tagged SARS-CoV-2 E protein or empty tag (pcDNA3) followed by western blot with FLAG antibody indicates that SARS-CoV-2 E is acetylated in vivo.

(C) Immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG beads on the same extracts as in (B) followed by western blot with BRD4 antibodies indicates that the SARS-CoV-2 E protein interacts with BRD4 in vivo.

(D) Acetylation efficiency of the SARS-CoV-2 E protein in vitro. Acetyltransferase assays using recombinant p300 and the native human MYST-family HAT complexes purified via MEAF6 (MYST) or BRPF2 (HBO1) subunits and the SARS-CoV-2 E48-72 peptide (aa 48–72 of SARS-CoV-2 E) as the substrate. Incorporation of 3H-ac was measured by liquid scintillation counting. Mock purification from K562 cells expressing an empty tag was used as control. Data are represented as mean ± SD among three replicates.

(E) Acetyltransferase assays using recombinant p300 and H3 peptide (aa 1–29 of H3). Mock corresponds to a mock purification control. Data are represented as mean ± SD among three technical replicates.

(F and G) Overlayed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled BRD4 BD1 (F) and BRD4 BD2 (G) recorded before and after gradual addition of the indicated acetylated SARS-CoV-2 E peptides. The spectra are color-coded according to the protein:peptide molar ratio. See also Figures S1, S2, and S4.

Here, we identified two mechanisms by which the E protein of SARS-CoV-2 hijacks the human transcriptional regulator BRD4. BD1 and BD2 of BRD4 associate with acetylated K53 and K63 of the E protein (SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac and EK63ac, respectively), preferring the diacetylated sequence (SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac), whereas the ET domain of BRD4 binds to the SFYVYSRVKNLN motif of the E protein (SARS-CoV-2 E55-66). We show that the E protein can be acetylated by human acetyltransferase p300, and that the SARS-CoV-2 infection is reduced by blocking BDs with the BET inhibitors JQ1 or OTX015. Our findings point to a new strategy to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Results and discussion

The E protein of SARS-CoV-2 contains only two lysine residues, K53 and K63, located at the C-terminus of the protein amino acid sequence (Figure 1A). We used a combination of structural, biochemical, and enzymatic approaches to explore the idea that these lysine residues could be acetylated in the cell by human enzymes and subsequently recognized by bromodomains of human BRD4. The FLAG-tagged SARS-CoV-2 E protein was expressed in 293 T cells and its acetylation on lysine residues in vivo was confirmed by immunoprecipitation with anti-acetyl-lysine antibodies from whole cell extracts (Figures 1B and S1). Immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG beads on the same extracts followed by western blot with BRD4 antibodies also confirmed the interaction of the FLAG-tagged SARS-CoV-2 E protein with BRD4 (Figure 1C).

To test whether the SARS-CoV-2 E protein can be acetylated by human acetyltransferases, we performed in vitro acetyltransferase assays using a set of acetyltransferases known to acetylate histone and non-histone proteins. As shown in Figure 1D, recombinant p300 efficiently acetylated the SARS-CoV-2 E48-72 peptide (amino acids [aa] 48–72 of SARS-CoV-2 E), though the level of E peptide acetylation was lower than the level of acetylation of histone H3, a known substrate of p300 (Figure 1E). While acetylation of the SARS-CoV-2 E48-72 peptide by the human HAT complexes SAGA and NuA4/TIP60 was undetectable, the native human MYST-family HAT complexes purified via MEAF6 (MYST) or BRPF2 (HBO1) subunits were also able to some extent acetylate the SARS-CoV-2 E48-72 peptide.

The binding of BRD4 BDs to diacetylated SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac (aa 53–64 of SARS-CoV-2 E) peptide was evident in NMR experiments. Titration of SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac into the 15N-labeled BRD4 BD1 NMR sample led to large chemical shift perturbations (CSPs), and saturation was reached with a 2-fold excess of the SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac peptide (Figure 1F). Binding affinity of BD1 for SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac, measured via CSP analysis, was found to be 36 μM (Figure S2). Similarly, BD2 of BRD4 formed a complex with SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac based on CSPs in the intermediate exchange regime (Kd = 30 μM) (Figures 1G and S2). While BRD4 BD2 was capable of binding to both monoacetylated SARS-CoV-2 EK63ac (aa 60–68 of SARS-CoV-2 E) and SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac (aa 50–55 of SARS-CoV-2 E) peptides (Kds = 200 and 710 μM, respectively), BD1 selected for acetylated K63 (Kd = 660 μM) over acetylated K53 (Kd > 1 mM) (Figures 1F, 1G and S2).

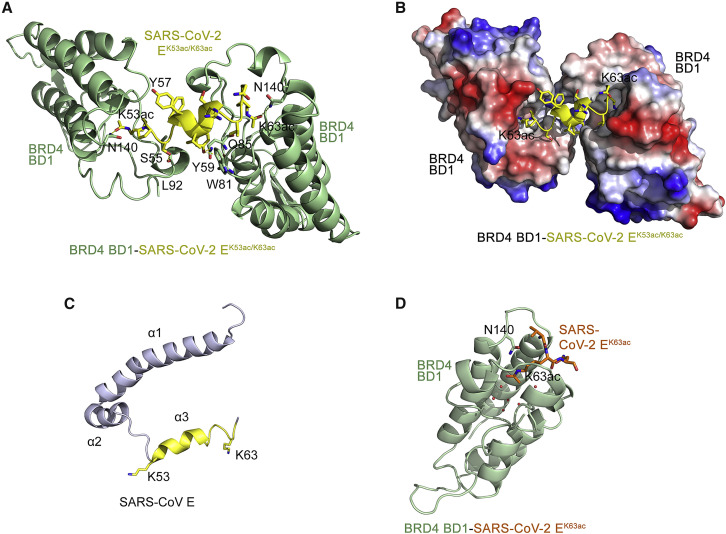

To gain insight into the mechanistic basis of the BRD4-E interaction, we co-crystallized BRD4 BD1 with the diacetylated SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac peptide and determined the crystal structure of the complex to 2.6-Å resolution (Figures 2A, 2B, and S3 and Table 1 ). The structure shows that two molecules of BD1 are engaged with one SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac peptide. BRD4 BD1 adopts a four-helix bundle fold with K53ac of the SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac peptide bound by one BD1 molecule, whereas K63ac of the peptide was bound by another BD1 molecule (Figure 2A). The side chains of both K53ac and K63ac, being in an extended conformation, insert deep into the hydrophobic pockets at the top of the α-helical bundles (Figure 2B). The characteristic hydrogen bonds with the side chain amide nitrogen of N140 of both BD1 molecules restrain the carbonyl oxygen of the acetyl groups of K53ac and K63ac of the peptide. The complex is further stabilized through the formation of hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl group of Y59 of SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac and the backbone carbonyl group of W81 and the side chain amide of Q85 of one BD1 molecule. The backbone carbonyl group of L92 from another BD1 molecule is hydrogen bonded to the hydroxyl group of S55 of SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac. The residues F56-R61 of SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac form an α-helix that positions K53ac and K63ac for the simultaneous interaction with two BDs, and interestingly, this region adopts an α-helical conformation in the structure of the homologous SARS-CoV E protein (Figure 2C) (Surya et al., 2018). The crystal structure of BRD4 BD1 in complex with monoacetylated SARS-CoV-2 EK63ac (aa 60–68 of SARS-CoV-2 E) peptide superimposes with the structure of the BD1-SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac complex with a root-mean-square deviation of 0.4 Å, revealing a conserved mode of acetyllysine recognition (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Structural basis of SARS-CoV-2 E recognition by BRD4 BDs

(A) A ribbon diagram of the crystal structure of BRD4 BD1 (green) in complex with the SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac peptide (aa 53–64 of SARS-CoV-2 E, yellow). Yellow dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds.

(B) Electrostatic surface potential of BRD4 BD1 in complex with SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac (yellow ribbon), with blue and red colors representing positive and negative charges, respectively.

(C) A ribbon diagram of the NMR structure of the homologous E protein from SARS-CoV (PDB ID: 5X29). An exposed C-terminal α-helix 3, consisting of residues K53-K63, is yellow.

(D) Crystal structure of BRD4 BD1 (green) in complex with the SARS-CoV-2 EK63ac peptide (aa 60–68 of SARS-CoV-2 E, orange). Red spheres represent water molecules. See also Figure S3.

Table 1.

Diffraction data collection and refinement statistics for BRD4 BD1 in complex with acetylated SARS-CoV-2 E peptides

| BRD4-BD1 in complex with monoacetylated SARS-CoV-2 EK63ac peptide | BRD4-BD1 in complex with diacetylated SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/K63ac peptide | |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | ||

| Space group | C 2 2 21 | P 21 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.54 | 1.54 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0-2.68 (2.81-2.68)a | 48.11-2.60 (2.72-2.60)a |

| Unit-cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 78.5, 91.4, 100.3 | 49.32, 96.22, 78.95 |

| α, β, γ | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 90.00, 94.37, 90.00 |

| No. of measured reflections | 49,963 | 41,616 |

| No. of unique reflections | 10,316 (1,316) | 22,330 (2,702) |

| Multiplicity | 4.8 (4.4) | 1.9 (1.8) |

| I/σ | 14.6 (3.5) | 5.7 (1.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.9 (96.4) | 98.5 (98.0) |

| Rsymb (%) | 8.6 (49.7) | 11.9 (40.4) |

| No. of molecules in ASU | 2 | 4 |

| Matthew’s coefficient (Å3 Da−1) | 2.76 | 2.75 |

| Solvent content (%) | 55.4 | 55.3 |

| Refinement | ||

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 21.6/27.6 (33.8/38.1) | 24.3/29.2 (32.2/40.9) |

| No. of atoms | 2021 | 4996 |

| Protein | 1960 | 4758 |

| Water | 61 | 238 |

| B-factors (Å2) | 4.0.89 | 25.34 |

| Protein | 41.12 | 25.52 |

| Water | 33.69 | 21.68 |

| RMSD | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.003 | 0.004 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.58 | 0.73 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 97.8 | 98.0 |

| Ramachandran allowed (%) | 2.2 | 2.0 |

| Ramachandran outliers | 0 | 0 |

| Clashscore | 3.32 | 6.72 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell (Å).

Rsym = ∑|Iobs −Iavg|/Iavg, where Iobs is intensity of any given reflection and Iavg is the weighted mean I.

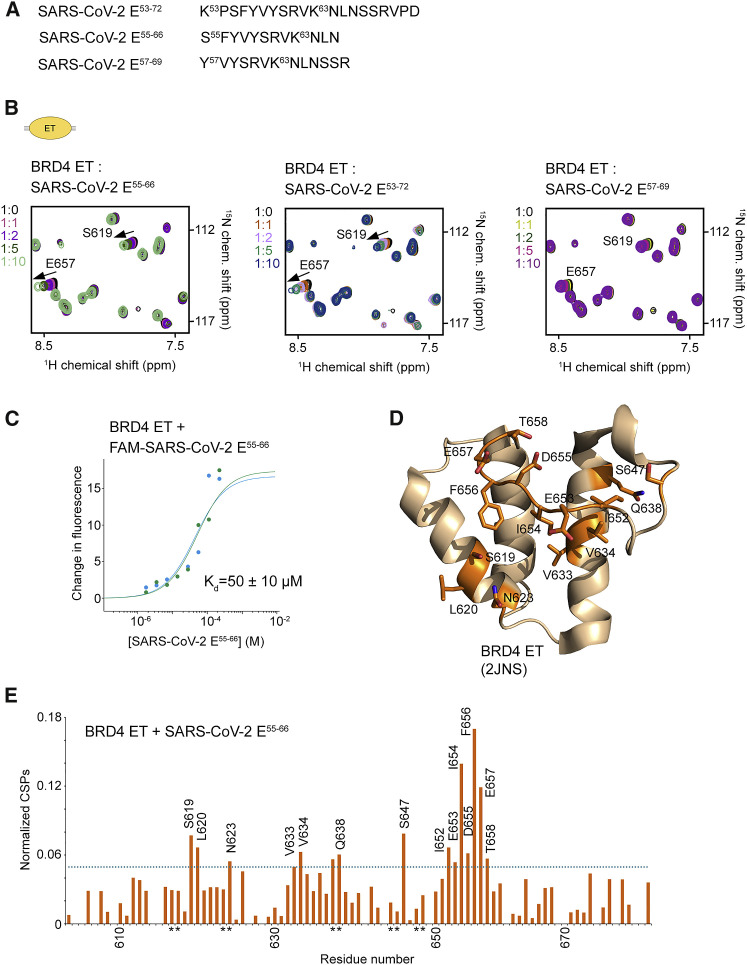

Notably, the SARS-CoV-2 E protein contains the sequence RVK63N, which resembles the KhKh motif that is recognized by the ET domain of BRD4 (Figures 1A and 3A). To test the idea that the BRD4 ET domain binds to the unmodified E protein, we titrated SARS-CoV-2 E55-66 (aa 55–66 of SARS-CoV-2 E) into the BRD4 ET NMR sample (Figure 3B). CSPs and disappearance of the ET resonances pointed to an interaction, which was confirmed by measuring Kd for the BRD4 ET-E55-66 complex by microscale thermophoresis (MST) (Kd = 50 μM) (Figure 3C). The longer peptide SARS-CoV-2 E53-72 (aa 53–72 of SARS-CoV-2 E) did not alter the pattern of CSPs in BRD4 ET, indicating that the SARS-CoV-2 E55-66 sequence is sufficient for the interaction; however, removing S55 and F56 in the SARS-CoV-2 E57-69 (aa 57–69 of SARS-CoV-2 E) peptide led to small CSPs, suggesting that SF56 is necessary for binding of BRD4 ET. Mapping CSPs caused by SARS-CoV-2 E55-66 onto the structure of BRD4 ET delineated the binding interface, which encompasses the groove formed by α1 and α2 helices and the loop between α2 and α3 of the ET domain (Figures 3D and 3E).

Figure 3.

The ET domain of BRD4 is an additional target of SARS-CoV-2 E

(A) The SARS-CoV-2 E peptides tested.

(B) Overlayed 1H,15N HSQC spectra of the 15N-labeled BRD4 ET domain recorded before and after gradual addition of the indicated SARS-CoV-2 E peptides. The spectra are color-coded according to the protein:peptide molar ratio.

(C) Representative MST binding curves for the interaction of the BRD4 ET domain with the FAM-SARS-CoV-2 E55-66 peptide. Data are representative of two experiments, and error represents SEM.

(D and E) Analysis of CSPs in the BRD4 ET domain induced by SARS-CoV-2 E55-66. Residues of the BRD4 ET domain that exhibited large chemical shift perturbations (greater than the average plus 1 SD) upon addition of SARS-CoV-2 E55-66 are mapped onto the BRD4 ET structure (2JNS), labeled, and colored orange in (D). Histogram of normalized CSPs in 1H,15N HSQC spectra of BRD4 ET induced by 10-fold molar excess of SARS-CoV-2 E55-66 as a function of residue is shown in (E). The dotted line indicates average chemical shift change plus 1 SD. Side chain amide resonances are indicated by asterisk.

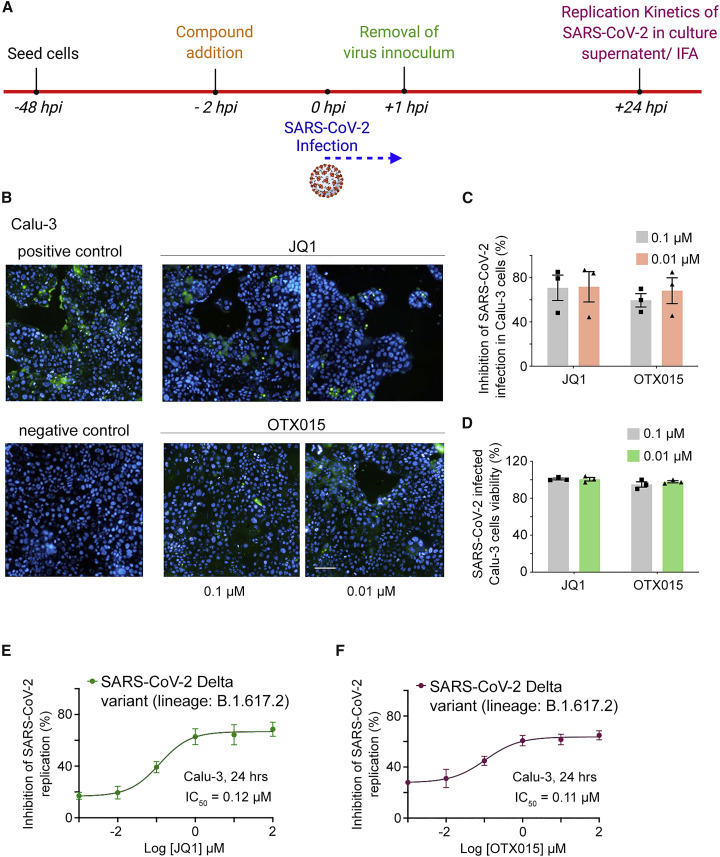

BRD4 is known to mediate immune and inflammatory responses to viral infection and was recently reported to regulate COVID-19-mediated cytokine storm and cardiac damage (Mills et al., 2021). Furthermore, BET inhibitors were shown to downregulate the expression of viral host entry factors, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), thereby limiting SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro (Gilham et al., 2021; Qiao et al., 2020), and have potent anti-viral activity (Acharya et al., 2022; Qiao et al., 2020; Samelson et al., 2022). To examine the importance of the BRD4-E interaction for the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle, we infected the human lung bronchial epithelial cell line Calu-3 with a Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 (pangolin linage B.1.617.2) and monitored infection by immunofluorescence (Figures 4A and 4B). As shown in Figure 4B, the addition of inhibitors of BRD4, JQ1 or OTX015, led to a decrease in Spike SARS-CoV-2 protein staining (green), indicating that the acetyllysine binding activity of BDs is necessary for the virus fitness. At the concentration of 0.01 μM, JQ1 and OTX015 inhibited SARS-CoV-2 infection in Calu-3 cells by 72% and 69%, respectively, and showed low cytotoxicity with Calu-3 cell viability being 100% for JQ1-treated cells and 98% for OTX015-treated cells (Figures 4C and 4D). Based on viral loads in the culture supernatant of Calu-3 cells, JQ1 showed anti-viral activity with a half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 0.12 μM, and OTX015 showed anti-viral activity with an IC50 of 0.11 μM against the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2 (Figures 4E and 4F). These data suggest that the disruption of acetyllysine binding activity of BRD4 might represent a novel approach to combat the infection.

Figure 4.

BRD4 inhibitors JQ1 and OTX015 block SARS-CoV-2 replication

(A) Experimental diagram: the viral replication kinetics were measured in Calu-3 cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Delta variant of concern, pangolin linage: B.1.617.2) with 0.5 MOI of viral titer and treated with JQ1 or OTX015.

(B) Representative immunofluorescence images of infected (or uninfected negative control) Calu-3 cells probed with antibodies against the Spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 (green) in the absence (positive control) or presence of JQ1 and OTX015 at the indicated concentrations. Scale bar, 100 μm for all panels.

(C) Percent inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Calu-3 cells treated with JQ1 and OTX015 at the indicated concentrations.

(D) Cell viability in compound treated and SARS-CoV-2 infected Calu-3 cells. Data in (C and D) represent mean of three replicates, and error bars represent SEM. n = 3. Cells were from the same frozen stock, and experiments were performed using the same plate on the same day.

(E and F) Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication in Calu-3 cells treated with JQ1 (E) or OTX015 (F). BRD4 inhibitor mediated effects on SARS-CoV-2 viral load were quantified in the culture supernatant using RT-qPCR and plotted as % inhibition of viral replication. Data in (E and F) represent mean of three independent measurements, and error bars represent SEM. n = 3.

Collectively, in this study we identified the molecular basis underlying SARS-CoV-2 association with the transcriptional activator BRD4 and show that the interaction between BRD4 and the E protein is essential for SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis in human cells. We found that the full-length SARS-CoV-2 E protein is acetylated in vivo and co-immunoprecipitates with BRD4 in 293T cells and that the C-terminus of SARS-CoV-2 E can be acetylated in vitro by human acetyltransferases, such as p300. The interaction between BRD4 BDs and acetylated SARS-CoV-2 E represents yet another example that highlights how vital host cell signaling programs can be hijacked by posttranslationally modified viral proteins. Posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of viral proteins, such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, methylation, and acetylation, installed by host enzymes during infection have been shown to play essential roles in the virus replication, fusion with the host membrane, and localization in the host cell, as well as in host defense (reviewed in Kumar et al., 2020; Murray et al., 2019). Acetylation of Tat, a human immunodeficiency virus HIV-1 protein, the influenza A protein NP, and the pUL26 protein of the human cytomegalovirus affects virulence properties, production of viral proteins, and virus replication and assembly (Kumar et al., 2020; Murray et al., 2019). Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that the E2 protein of papillomaviruses is acetylated by p300 (Jose et al., 2021) and that methylated non-structural protein 1 (NS1) from H3N2-subtype influenza A binds to histone readers (Marazzi et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2019).

Our findings point to a new strategy to block SARS-CoV-2 infection and aid in our understanding of how SARS-CoV-2 targets host cell signaling pathways and alters immune responses. Future studies are needed to address important questions, including whether BDs and the ET domain of BRD4 can be engaged with the E protein simultaneously. It will also be essential to establish which domain in BRD4 is the preferred target and whether the BRD4-SARS-CoV-2 E interactions are conserved in other BET family proteins and what biological roles they may play.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-Spike of SARS-CoV-2 | Sino biological | MA14AP0204 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-rabbit | Thermo Fisher | Cat # A-11034 |

| Anti-FLAG M2 agarose affinity gel (For IP) | Sigma-Aldrich | A2220 |

| Anti-acety-lysine (For IP) | ImmuneChem | ICP0380 |

| Anti-FLAG M2 HRP conjugated (For WB) | Sigma-Aldrich | A8592 |

| Anti-Brd4 (For WB) | Abcam | Ab46199 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus (De3) RIL | Agilent Technologies | 230245 |

| DH5α Competent Cells | Thermo Fisher Sci | Cat. # 18265017 |

| SARS-Related Coronavirus 2, Isolate hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP05647/2021 | BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH | NR-55672 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Dithiothreitol | Gold Biotechnology | 27565-41-9 |

| β-mercaptoethanol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat. # M6250 |

| Imidazole | Alfa Aesar | Cat. # A10221 |

| 15NH4Cl | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat. # 299251 |

| JQ1 | Cayman Chemical | 11187 |

| OTX015 | Cayman Chemical | 15947 |

| IPTG | Goldbio | Cat. # I2481 |

| Ni-NTA resin | Thermo Scientific | Cat. # 88223 |

| Glutathione Sepharose 4B beads | GE Healthcare | Cat. # 17-0756-01 |

| Streptavidin magnetic beads | Thermo Fisher Sci | Cat. # 88816 |

| E peptides | Synpeptide | N/A |

| PreScission protease | Home expressed | N/A |

| Thrombin protease | MP Biomedicals | 154163 |

| Enterokinase protease | NEB | P8070S |

| Hoechst 33258 | Invitrogen | Cat # H3570 |

| Cell Mask | Invitrogen | Cat # C10046 |

| Recombinant p300 (catalytic domain) | Active Motif | 81093 |

| Lipofectamine 3000 | Invitrogen | L3000001 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Platinum™ II Hot-Start PCR Master Mix (2X) | Thermo Fisher Sci | 14000013 |

| QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit | QIAGEN | Cat # 27106 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Crystal structure of BRD4 Bromodomain 1 in complex with SARS-CoV-2 E peptide diacetylated at K53 and K63 | This study | PDB: 7TV0 |

| Crystal structure of BRD4 Bromodomain 1 in complex with SARS-CoV-2 E peptide acetylated at K63 | This study | PDB: 7TUQ |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Calu-3 cells | ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA | HTB-55 |

| K562 | ATCC | CCL-243 |

| 293T | ATCC | CRL-3216 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| BamH1 E: atataggatccTACAGCTTCGTATCAGAAGA | This study | N/A |

| Xho1 E: atatactcgagTCATTCGAGAACGAGGAGATC | This study | N/A |

| gBlockE: TACAGCTTCGTATCAGAAGAAA CCGGGACACTGATCGTAAATTCTGTGCTC TTGTTTCTGGCATTCGTCGTATTTC TCCTCGTCACACTGGCAATTCTGA CTGCATTGAGGCTTTGCGCCTACT GTTGTAACATTGTCAATGTATCTCTC GTGAAACCCTCATTCTACGTTTACA GCAGGGTGAAGAATCTCAATTCTA GCAGGGTGCCGGATCTCCTCGTTCTCGAA |

This study | N/A |

| E_Sarbeco_F1: ACAGGTACGTTAATAGTTAATAGCGT | This study | N/A |

| E_Sarbeco_R2: ATATTGCAGCAGTACGCACACA | This study | N/A |

| E_Sarbeco_P1:FAM -ACACTAGCCATCCT TACTGCGCTTCG - BHQ1 |

This study | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pGEX-6P-1 | Cytiva | 28-9546-48 |

| pGEX-4T-1 | Cytiva | 28-9545-49 |

| pcDNA3.1 | Invitrogen | V79020 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| XDS | Kabsch (2010) | https://xds.mr.mpg.de/ |

| Phenix | Adams et al., 2010 | http://www.phenix-online.org/ |

| Coot | Emsley et al., 2010 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| Prism 9.0 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| CCP4 | M. D. Winn et al., 2011 | https://www.ccp4.ac.uk/ |

| NMRPipe | Delaglio et al., 1995 | https://www.ibbr.umd.edu/nmrpipe/ |

| MO.Affinity Analysis | NanoTemper Technologies | https://nanotempertech.com/monolith-mo-control-software/ |

| MO.Control software | NanoTemper Technologies | https://nanotempertech.com/monolith-mo-control-software/ |

| Other | ||

| qPCR Control RNA from Heat-Inactivated SARS-Related Coronavirus 2, Isolate USA-WA1/2020 | BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH | NR-52347 |

| HiPrep™ 16/60 Sephacryl® S-100 HR column | GE Healthcare | Cat. # 17-1165-01 |

| HiTrap SP HP column | Cytiva | 17115201 |

| HiLoad Superdex 75 pg column | Cytiva | 28989333 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Tatiana G. Kutateladze (tatiana.kutateladze@cuanschutz.edu).

Materials availability

All expression plasmids used in this study will be made available on request. This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

The BD1 and BD2 domains of BRD4 were expressed in BL21 (DE3) RIL in LB or minimal media supplemented with 15NH4Cl. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 16 h at 18°C. The ET domain of BRD4 was expressed in Tuner (DE3) cells in minimal media supplemented with 15NH4Cl. Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 16 h at 18°C. The native MYST-family HAT complexes MEAF6 (MYST) and BRPF2 (HBO1) were purified by tandem affinity steps (3xFlag-2xStrep) from human K562 cells expressing endogenously tagged MEAF6 or BRPF2 from the AAVS1 safe harbor. Human bronchial epithelial Calu-3 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in complete medium [Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) ATCC] supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (P/S). Human Kidney 293T (ATCC, CRL-3216) were maintained in complete medium DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Human bone marrow K652 (ATCC, CCL-243) were maintained in complete medium RPMI with 10% New Born Calf Serum (NBCS).

Method details

Cloning and protein expression and purification

pGEX6P-1 BRD4 bromodomain 1 (residues 43-180) and pGEX4T-1 BRD4 bromodomain 2 (residues 342-460) constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) RIL cells in Luria Broth or minimal media supplemented with 15NH4Cl. The cells were cultured at 37°C, induced with a final concentration of 1 mM IPTG and cultured for 16 h post-induction at 18°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm. The cells were resuspended in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM TCEP, lysed by sonication, and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 15000 rpm. Unlabeled and 15N-labeled BRD4 BD1 or BD2 domains were purified on glutathione Sepharose 4B beads, and the GST tag was cleaved with PreScission (BD1) or thrombin (BD2) protease. The cleaved protein was concentrated using a 3 kDa CO concentrator and further purified by FPLC using a HiPrep Sephacryl S-100 HR column (GE) in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP. Protein fractions were checked for purity by SDS-PAGE and concentrated to ∼9-20 mg/mL.

The pET32a BRD4 ET domain (600-700) vector was a gift from Tim McKinsey. The TRX-6His-S-tagged ET domain was expressed in Escherichia colicTuner (DE3) cells in minimal media supplemented with 15NH4Cl. Cells were cultured at 37°C, induced with a final concentration of 0.5 mM IPTG, cultured for 16 h post-induction at 18°C and harvested by centrifugation at 5000 rpm. Cells were resuspended in 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0) buffer, supplemented with 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole and 2 mM BME, lysed by sonication, and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm. Unlabeled and 15N-labeled His-tagged ET domain was purified on Nickel-NTA resin (ThermoScientific). The tagged protein was eluted using a 30-300 mM imidazole gradient elution. The eluted protein was first buffer exchanged into cleavage buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2 and then cleaved overnight at RT with enterokinase protease (NEB). The ET domain was further purified using Nickel-NTA resin (Thermo Scientific) and ion exchange using a HiTrap SP column (Cytiva) to remove the cleaved tag. Size-exclusion chromatography was performed using a Superdex S75 column (Cytiva). The purified protein was buffer exchanged into 20 mM Tris pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM DTT, concentrated to ∼10 mg/mL using 3 kDa Millipore concentrator.

The full-length SARS-CoV-2 E sequence was synthetized by gBlock (IDT) and amplified by PCR with BamHI and XhoI restriction sites for ligation in the BamHI and XhoI digested pcDNA3 3xFlag plasmid.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments were carried out on a Varian INOVA 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe at 298 K. The 1H,15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra of 0.2 mM uniformly 15N-labeled BRD4 BD1 and BRD4 BD2 were collected in the presence of increasing concentrations of indicated SARS-CoV-2 peptides in PBS buffer, pH 6.8, 10% D2O. 1H,15N HSQC spectra of 0.15 mM uniformly 15N-labeled BRD4 ET were collected in the presence of increasing concentrations of indicated SARS-CoV-2 peptides (diluted to a stock of 50 mM in 50–100% DMSO) in 20 mM Tris pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM DTT and 10% D2O. NMR data were processed with NMRPipe. NMR assignments for BRD4 ET were taken from (Zhang et al., 2016). Control experiments, demonstrating that the BRD4 ET domain is not perturbed by DMSO and BRD4 BD1 does not bind to non-acetylated SARS-CoV-2 peptide (aa 53-72) are shown in Figure S4.

The dissociation constants (Kds) were determined by a nonlinear least-squares analysis in GraphPad Prism using the equation:

where [L] is concentration of the peptide, [P] is concentration of the protein, Δδ is the observed chemical shift change, and Δδmax is the normalized chemical shift change at saturation. Normalized chemical shift changes were calculated using the equation where Δδ is the change in chemical shift in parts per million (ppm).

X-Ray crystallography

BRD4 BD1 (residues 43-180) was incubated with 2 molar equivalence of peptide at 4°C overnight and then dialyzed against 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP. The dialyzed protein-peptide mixtures were concentrated to 7-15 mg/mL. Crystals of BRD4 BD1 in complex with SARS-CoV-2 E peptides were grown by the sitting-drop or hanging-drop vapor diffusion method in a 0.6–3 μL drop using 1:1 or 1:2 ratio of protein/peptide: reservoir solution at 18°C. Crystals of BRD4 BD1 in complex with Ac-SRVK(ac)NLNSS-NH2 SARS-CoV-2 EK63ac peptide (aa 60-68) were formed in a sitting-drop and BRD4 BD1 in complex with dual acetylated SARS-CoV-2 EK53ac/63ac peptide (aa 53-64) were formed in a hanging-drop against the reservoir solution (1.5 M ammonium sulfate,100 mM Tris pH 8.5 and 12% glycerol). X-ray diffraction datasets for the complexes were collected at 100 K on a Rigaku Micromax 007 high-frequency microfocus X-ray generator with a Pilatus 200K 2D area detector (University of Colorado Anschutz X-ray core facility). The data were indexed and scaled using XDS (Kabsch, 2010). Phase solutions were determined by molecular replacement in Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007) using an edited version of BRD4 BD1 (PDB IDs: 3JVK and 3UVW) as search models. Refinement was performed in PHENIX Refine (Adams et al., 2002) and manually by Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004).

Affinity purifications of native histone acetyltransferase complexes

Native HBO1 (BRPF2) and MYST (MEAF6) acetyltransferase complexes were purified by Tandem Affinity Purification (TAP, 3Flag-2Strep) as described (Dalvai et al., 2015).

Acetyltransferase assays

Acetyltransferase assays with recombinant p300 (catalytic domain, ActiveMotif, Cat # 81093) or purified native human histone acetyltransferase complexes were performed in a volume of 15 μL. The native MYST-family HAT complexes MEAF6 (MYST) and BRPF2 (HBO1) were purified by tandem affinity steps (3xFlag-2xStrep) from human K562 cells expressing endogenously tagged MEAF6 or BRPF2 from the AAVS1 safe harbor (Dalvai et al., 2015; Klein et al., 2019). Mock purification from K562 cells expressing an empty tag was used as control. 0.1 μg of p300 was used in the reactions with the E peptide and 0.2 μg of p300 was used in the reactions with the histone peptides. The reaction mixtures containing 0.5 μg of the E peptide (aa 48-72 of E) or recombinant H3 peptide (aa 1-29 of H3) as substrates and 0.125 μCi of 3H labeled Ac-CoA (2.1 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences) in buffer 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM sodium butyrate, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol were incubated for 30 min at 30°C. The reactions were then spotted on P81 filter paper, and the free 3H-labeled Ac-CoA was washed away with 50 mM NaHCO3-Na2CO3 pH 9.2. The filter was rinsed with acetone, dried, and then analyzed using Liquid Scintillation.

Microscale thermophoresis (MST)

FAM-labeled SARS-CoV-2 E peptide (Synpeptide) was diluted to a stock of 50 mM in 100% DMSO. Working concentrations were diluted in 20 mM Tris pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM DTT, 0.05% Tween 20 with a final concentration of 5% DMSO, which was also used as assay buffer for MST experiments. FAM-labeled peptide was used as the target at a concentration of 500 nM, while non-labeled ET protein was titrated in a 1:1 dilution series (1-200 μM). Samples were mixed, centrifuged and loaded into premium-treated capillaries (NanoTemper Technologies) and measured using a Monolith NT.115 pico and MO.Control software (excitation power setting 100%, NanoBlue, MST power 40%). Data were analyzed using MO.Affinity Analysis software (NanoTemper Technologies) at the standard MST-on time of 5 s.

Cell culture

Human bronchial epithelial Calu-3 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were maintained in complete medium [Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM) ATCC] supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (P/S). Human Kidney 293T (ATCC, CRL-3216) were maintained in complete medium DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Human bone marrow K652 (ATCC, CCL-243) were maintained in complete medium RPMI with 10% New Born Calf Serum (NBCS).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Human kidney 293T cells at 80–90% confluency in D150 mm plate (∼1.6×107 cells) were transfected with 20 μg of pcDNA3 (empty FLAG, Invitrogen, Cat #V79020) or pcDNA3 SARS-CoV-2 E 3xFLAG with lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Cat #L3000001) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were harvested 76 h post-co-transfection and lysed in 500 μL of WCE buffer (450 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1% TX-100, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ZnCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture. The NaCl concentration was reduced to 225 mM, and the whole cell extract was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 min. The FLAG SARS-CoV-2 E was immunoprecipitated from the soluble fraction using 50 μL anti-FLAG M2 affinity beads (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat # A2220) for 2 h at 4°C on a rotating wheel or with 6 μg of anti-acetyl-lysine antibody (ImmuneChem, Cat # ICP0380) for 3 h at 4°C on a rotating wheel and followed by incubation with 50 μL protein G-Sepharose beads (Dynabeads Invitrogen, 10002D). The immunoprecipitation was eluted in 45 μL of 1xLaemmli Buffer at 95°C for 10 min. 1% Input and 15 μL of immunoprecipitations were used for western blotting. Anti-FLAG M2 conjugated to horseradish peroxydase (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat # A8592) was used at a 1:10,000 dilution, and the immunoblots were visualized using a Western Lightning plus-ECL reagent (PerkinElmer). Anti-BRD4 (Abcam, Cat # ab46199) was used at a 1:1,000 dilution. Uncropped western blots are shown in Figure S5.

SARS-CoV-2 (Delta variant) infection of Calu-3 cells and BRD4 inhibitor studies

All live virus experiments were performed in the BSL3 laboratory at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (Omaha, NE, USA). Calu-3 cells were plated in a 96 well transparent bottom black color plate (15000 cells/well) and cultured for 48 h before infection. On the day of infection, the cells were treated with different concentrations of JQ1 (Cayman Chemical, Cat # 11187) or OTX015 (Cayman Chemical, Cat # 15947) (0.1 μM to 0.001 μM) two hours before infection. The cells were infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Delta variant of concern (VOC); pangolin linage: B.1.617.2, obtained from BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH; cat # 55672) with 0.5 MOI of viral titer or left uninfected (negative control). One hour post-infection, virus inoculum was removed from the cells, washed 3 times with 1X PBS, replenished with fresh media and treated with respective compounds. The reaction was terminated 24 h post-infection. The culture supernatant was collected for measuring the viral replication kinetics, and the cells were washed and fixed with 4% PFA for immunofluorescence analysis.

Viral replication kinetics using RT-qPCR

The SARS-CoV-2 viral load in the cells was determined as described (Acharya et al., 2021). Briefly, RT-qPCR was performed on a set of primers targeting the E gene of SARS-CoV-2 using PrimeDirect Probe RT-qPCR Mix (TaKaRa Bio USA, Inc) and Applied Biosystems QuantStudio3 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). The SARS-CoV-2 genome equivalent copies were calculated by quantitative PCR control RNA from heat-inactivated SARS-CoV-2, isolate USA-WA1/2020 (BEI, Catalog# NR-52347). The percent inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 replication by JQ1 and OTX015 treatment was measured based on viral concentration in positive control wells (considered 0% inhibition) and negative control wells (uninfected cells). IC50 values were calculated using four-parameter variable slope sigmoidal dose-response models using Graph Pad Prism 9.0 software.

Immunofluorescence

The 4% PFA fixed Calu-3 cells were washed three times with 1X PBS and permeabilized by adding 50 μL of 0.1% Triton X-100. Blocking was performed in 3% bovine serum albumin-phosphate buffered saline for 2 h. Then, 50 μL of the primary antibody against the Spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 (Sino biological, Cat # MA14AP0204) was added at a 1:1,000 dilution, and cells were incubated overnight at 4°C on a shaker. The cells were washed three times with 1X PBS, and 50 μL of secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-rabbit (Thermo Fisher, Cat # A-11034) was added per well at a 1:2,000 dilution. The reactions were incubated for 1 h in the dark at room temperature on a shaker. The reactions were incubated at room temperature on a shaker for 1 h in the dark. The cells were then washed once with 1X PBS, stained with Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen, Cat #H3570) and Cell Mask (Invitrogen, Cat #C10046) to visualize the nucleus and cytoplasm. Images were captured using a high content analysis system at 20X air on an Operetta CLS. Data were analyzed with the Harmony analysis software.

Quantification and statistical analysis

The crystal structure of the BRD4 BD1 domain in complex with mono- and diacetylated E peptides were determined using materials and softwares listed in the Key resources table. Statistics generated from X-ray crystallography data processing, refinement, and structure validation are displayed in Table 1. Data shown in Figures 1D and 1E represent mean of three independent measurements, and error represents SD n = 3 Data shown in Figures 4C–4F represent mean of three replicates, and error bars represent SEM n = 3 IC50 values shown in Figures 4E and 4F were calculated using four-parameter variable slope sigmoidal dose-response models using Graph Pad Prism 9.0 software.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from NIH: HL151334, CA252707, GM125195, GM135671, and AG067664 to T.G.K. and AI129745 and DA052845 to S.N.B., and a foundation grant from the CIHR to J.C. (FDN-143314). S.N.B. acknowledges independent research and development (IRAD) funding from the National Strategic Research Institute (NSRI) at the University of Nebraska. J.C. holds the Canada Research Chair on Chromatin Biology and Molecular Epigenetics. We acknowledge the UNMC BSL-3 core facility at DRC-1 where experiments involving live SARS-CoV-2 were performed and St Patrick Reid laboratory for the use of Operetta CLS. UNMC BSL-3 core facility is administered by the Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Research and supported by the Nebraska Research Initiative (NRI).

Author contributions

K.R.V., A.A., S.M.J., C. L., M.Z., T.A.H., A.L.S., and K.P. performed experiments and, together with D.L.D., D.E.G., J.C., S.N.B., and T.G.K., discussed and analyzed the data. K.R.V. and T.G.K. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: June 17, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.str.2022.05.020.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes 7TV0 and 7TUQ. Other data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Acharya A., Pandey K., Thurman M., Klug E., Trivedi J., Sharma K., Lorson C.L., Singh K., Byrareddy S.N. Discovery and evaluation of entry inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 and its emerging variants. J. Virol. 2021;95:e0143721. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01437-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya A., Pathania A.S., Pandey K., Thurman M., Vann K.R., Kutateladze T.G., Challagundala K.B., Durden D.L., Byrareddy S.N. PI3K-α/mTOR/BRD4 inhibitor alone or in combination with other anti-virals blocks replication of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants of concern including Delta and Omicron. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022;12:e806. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams P.D., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Hung L.W., Ioerger T.R., McCoy A.J., Moriarty N.W., Read R.J., Sacchettini J.C., Sauter N.K., Terwilliger T.C. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvai M., Loehr J., Jacquet K., Huard C.C., Roques C., Herst P., Côté J., Cote J., Doyon Y. A scalable genome-editing-based approach for mapping multiprotein complexes in human cells. Cell Rep. 2015;13:621–633. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeDiego M.L., Alvarez E., Almazan F., Rejas M.T., Lamirande E., Roberts A., Shieh W.J., Zaki S.R., Subbarao K., Enjuanes L. A severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus that lacks the E gene is attenuated in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 2007;81:1701–1713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01467-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/s0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P., Knapp S. Targeting bromodomains: epigenetic readers of lysine acetylation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:337–356. doi: 10.1038/nrd4286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P., Picaud S., Mangos M., Keates T., Lambert J.P., Barsyte-Lovejoy D., Felletar I., Volkmer R., Müller S., Pawson T., et al. Histone recognition and large-scale structural analysis of the human bromodomain family. Cell. 2012;149:214–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilham D., Smith A.L., Fu L., Moore D.Y., Muralidharan A., Reid S.P.M., Stotz S.C., Johansson J.O., Sweeney M., Wong N.C.W., et al. Bromodomain and extraterminal protein inhibitor, apabetalone (RVX-208), reduces ACE2 expression and attenuates SARS-Cov-2 infection in vitro. Biomedicines. 2021;9:437. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9040437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D.E., Jang G.M., Bouhaddou M., Xu J., Obernier K., White K.M., O'Meara M.J., Rezelj V.V., Guo J.Z., Swaney D.L., et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature. 2020;583:459–468. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose L., Gilson T., Androphy E.J., DeSmet M. Regulation of the human papillomavirus lifecyle through post-translational modifications of the viral E2 protein. Pathogens. 2021;10:793. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10070793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/s0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein B.J., Jang S.M., Lachance C., Mi W., Lyu J., Sakuraba S., Krajewski K., Wang W.W., Sidoli S., Liu J., et al. Histone H3K23-specific acetylation by MORF is coupled to H3K14 acylation. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4724. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12551-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Mehta D., Mishra N., Nayak D., Sunil S. Role of host-mediated post-translational modifications (PTMs) in RNA virus pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;22:323. doi: 10.3390/ijms22010323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J.P., Picaud S., Fujisawa T., Hou H., Savitsky P., Uusküla-Reimand L., Gupta G.D., Abdouni H., Lin Z.Y., Tucholska M., et al. Interactome rewiring following pharmacological targeting of BET bromodomains. Mol. Cell. 2019;73:621–638.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Lai S., Gao G.F., Shi W. The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;600:408–418. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marazzi I., Ho J.S.Y., Kim J., Manicassamy B., Dewell S., Albrecht R.A., Seibert C.W., Schaefer U., Jeffrey K.L., Prinjha R.K., et al. Suppression of the antiviral response by an influenza histone mimic. Nature. 2012;483:428–433. doi: 10.1038/nature10892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy A.J., Grosse-Kunstleve R.W., Adams P.D., Winn M.D., Storoni L.C., Read R.J. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/s0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills R.J., Humphrey S.J., Fortuna P.R.J., Lor M., Foster S.R., Quaife-Ryan G.A., Johnston R.L., Dumenil T., Bishop C., Rudraraju R., et al. BET inhibition blocks inflammation-induced cardiac dysfunction and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell. 2021;184:2167–2182.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L.A., Combs A.N., Rekapalli P., Cristea I.M. Methods for characterizing protein acetylation during viral infection. Methods Enzymol. 2019;626:587–620. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2019.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netland J., DeDiego M.L., Zhao J., Fett C., Alvarez E., Nieto-Torres J.L., Enjuanes L., Perlman S. Immunization with an attenuated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus deleted in E protein protects against lethal respiratory disease. Virology. 2010;399:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Torres J.L., DeDiego M.L., Verdiá-Báguena C., Jimenez-Guardeño J.M., Regla-Nava J.A., Fernandez-Delgado R., Castaño-Rodriguez C., Alcaraz A., Torres J., Aguilella V.M., Enjuanes L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein ion channel activity promotes virus fitness and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004077. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y., Wang X.M., Mannan R., Pitchiaya S., Zhang Y., Wotring J.W., Xiao L., Robinson D.R., Wu Y.M., Tien J.C., et al. Targeting transcriptional regulation of SARS-CoV-2 entry factors ACE2 and TMPRSS2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2020;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021450118. e2021450118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S., Liu Y., Tempel W., Eram M.S., Bian C., Liu K., Senisterra G., Crombet L., Vedadi M., Min J. Structural basis for histone mimicry and hijacking of host proteins by influenza virus protein NS1. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3952. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samelson A.J., Tran Q.D., Robinot R., Carrau L., Rezelj V.V., Kain A.M., Chen M., Ramadoss G.N., Guo X., Lim S.A., et al. BRD2 inhibition blocks SARS-CoV-2 infection by reducing transcription of the host cell receptor ACE2. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022;24:24–34. doi: 10.1038/s41556-021-00821-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeman D., Fielding B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019;16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Wang Y., Zeng L., Wu Y., Deng J., Zhang Q., Lin Y., Li J., Kang T., Tao M., et al. Disrupting the interaction of BRD4 with diacetylated Twist suppresses tumorigenesis in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:210–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surya W., Li Y., Torres J. Structural model of the SARS coronavirus E channel in LMPG micelles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018;1860:1309–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdiá-Báguena C., Nieto-Torres J.L., Alcaraz A., DeDiego M.L., Torres J., Aguilella V.M., Enjuanes L. Coronavirus E protein forms ion channels with functionally and structurally-involved membrane lipids. Virology. 2012;432:485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Zeng L., Shen C., Ju Y., Konuma T., Zhao C., Vakoc C.R., Zhou M.M. Structural mechanism of transcriptional regulator NSD3 recognition by the ET domain of BRD4. Structure. 2016;24:1201–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ahn J., Green K.J., Vann K.R., Black J., Brooke C.B., Kutateladze T.G. MORC3 is a target of the influenza A viral protein NS1. Structure. 2019;27:1029–1033.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes 7TV0 and 7TUQ. Other data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.