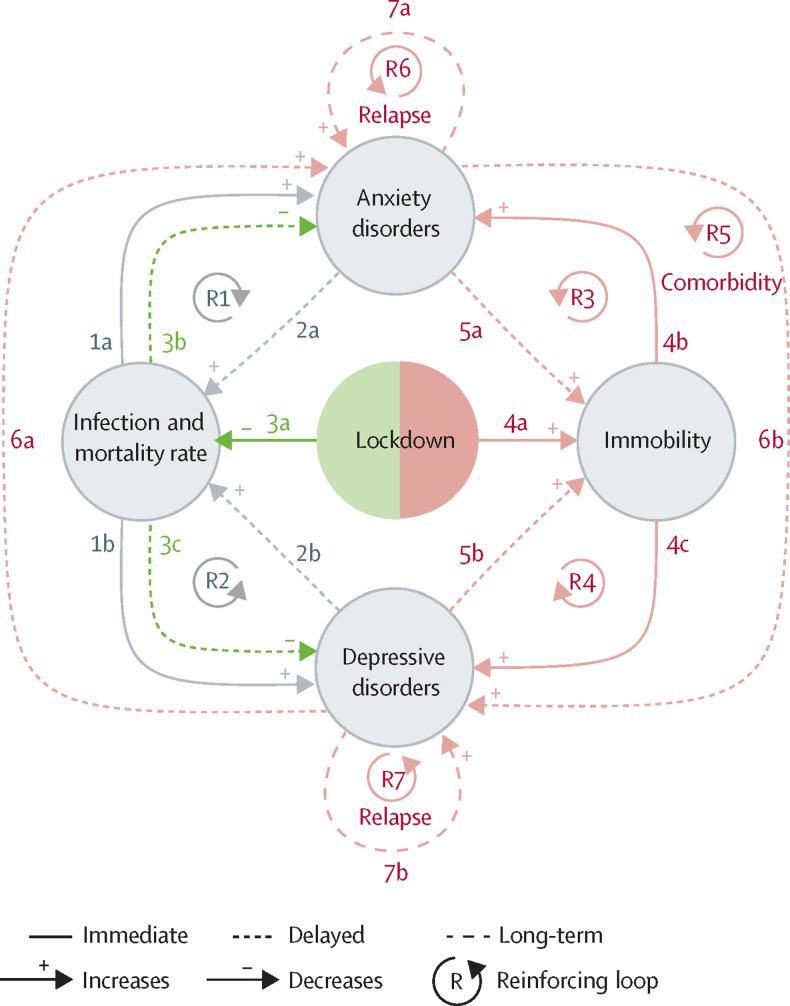

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) data for 2020 from 204 countries indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns increased the prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders worldwide.1 Two key factors behind these increases were identified: infection rate and immobility.1 Here we present a conceptual model that provides insight into the processes that underlie how these factors operate and can help to predict the long-term effects of the factors. The effect of infection rate and immobility on depressive and anxiety disorders is shown in the figure. (In the GBD study,1 infection rate was used as a proxy factor for the psychological effects [eg, fear of infection] of the pandemic and the physiological effects [eg, nervous system impairment2] of COVID-19.) The findings of the GBD study suggest that lockdowns, by decreasing the number of infections, can indirectly help to reduce the prevalence of anxiety disorders and depressive disorders (figure ).

Figure.

A conceptual model of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns on depressive and anxiety disorders

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (grey) include a higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders (1a,b). These disorders can also lead to more severe SARS-CoV-2 infections and increased mortality (2a,b). The beneficial effects of lockdowns (green) include fewer infections and reduced mortality, leading to fewer depressive and anxiety disorders (3a–c). Harmful effects of lockdowns (red) include immobility, leading to more depressive and anxiety disorders (4a–c), which then, in turn, increase immobility (5a,b). These disorders are also highly comorbid (6a,b) and are likely to relapse (7a,b).

However, any positive short-term effects of lockdowns on mental health (eg, due to safety behaviours, such as avoiding social contact and feeling less anxiety as a result) are likely to become counterproductive in the longer term (eg, social anxiety). Lockdowns decrease mobility, leading to a reduction in physical activity, social isolation, disruption of school and work-related activities, reduced peer interaction and learning, and restricted access to (mental) health care.1 The immobility resulting from the lockdowns was associated with an increased prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in the GBD study (figure).1 Therefore, lockdowns seem to have both advantageous and disadvantageous effects: by lowering infection rates, they might reduce the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders, but lockdowns are also likely to increase the prevalence of these disorders owing to the resulting immobility (figure). Future research on interventions to mitigate the adverse effects of lockdowns or other types of emergency policy on mental health could examine which elements of immobility are particularly harmful, and how to alleviate them.

Because depressive and anxiety disorders undermine general health, they can amplify the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection.3, 4 Infection severity and mortality rates are likely to be higher in people with depression and anxiety as a result of compromised immune system functioning in these disorders,3, 4 leading to a reinforcing feedback loop between the increased infection rates and the disorders (figure). Similarly, because depressive disorders and some anxiety disorders impair daily functioning, people with these disorders might have greater immobility than the general population—for instance, due to low energy, social withdrawal, or fear of leaving their houses. This can result in reinforcing feedback loops between increased immobility and the disorders (figure), which are likely to remain after the lockdowns are lifted and the pandemic is over.

Depressive and anxiety disorders are also highly comorbid.5 These disorders can form another feedback loop in which they can trigger and reinforce each other (figure). Such a loop is highly likely to operate during and after the lockdowns and the pandemic.

Finally, depressive and anxiety disorders are highly recurrent:6 individuals with major depressive disorder are estimated to have seven episodes throughout their lives.7 Both depressive and anxiety disorders can be risk factors for a subsequent episode, creating their own individual reinforcing feedback loops (figure) that can operate over months or years, leading to more mental health problems even after the lockdowns and the pandemic are long gone.

After the COVID-19 pandemic is over, affected individuals will most likely not return to their normal (mental) lives.8 As we aim to show with our conceptual model, common mental disorders can take a long time to subside because their strong self-reinforcing mechanisms can keep individuals trapped in complex, reinforcing negative cycles long after the triggering cause has disappeared.9 Moreover, because a previous episode is among the largest risk factors for depression9 and anxiety disorders,10 millions of individuals who have had these conditions during the pandemic will have them again—and multiple times—during their lives. COVID-19 will therefore have changed the mental health landscape of the coming decades.

Insights from research such as the GBD study outline environmental pathways that lead to depressive and anxiety disorders and help to identify reinforcing loops that keep individuals vulnerable during societally challenging times. With this emerging knowledge, we can identify new target points for interventions and inform policymakers of the risk factors. This will, in turn, enable us to prevent and treat mental health problems more effectively during any future pandemics or other societal crises involving immobility and heightened concern for one's safety, such as war.

We declare no competing interests. Research in the Amsterdam UMC and the Centre for Urban Mental Health is funded by the University of Amsterdam. The funding bodies had had no direct involvement in the conceptualisation or the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:1700–1712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683–690. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vai B, Mazza MG, Delli Colli C, et al. Mental disorders and risk of COVID-19-related mortality, hospitalisation, and intensive care unit admission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:797–812. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00232-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teixeira AL, Krause TM, Ghosh L, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 infection and mortality among patients with psychiatric disorders, 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Graaf R, Bijl RV, Smit F, Vollebergh WAM, Spijker J. Risk factors for 12-month comorbidity of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders: findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Am J Psych. 2002;159:620–629. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eaton WW, Shao H, Nestadt G, Lee HB, Bienvenu OJ, Zandi P. Population-based study of first onset and chronicity in major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:513–520. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruijshaar ME, Barendregt J, Vos T, de Graaf R, Spijker J, Andrews G. Lifetime prevalence estimates of major depression: an indirect estimation method and a quantification of recall bias. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:103–111. doi: 10.1007/s10654-004-1009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:611–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bockting CL, Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Kuyken W, Dobson K. A lifetime approach to major depressive disorder: the contributions of psychological interventions in preventing relapse and recurrence. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;41:16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hovenkamp-Hermelink JHM, Jeronimus BF, Myroniuk S, Riese H, Schoevers RA. Predictors of persistence of anxiety disorders across the lifespan: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:428–443. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30433-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]