PURPOSE:

Abiraterone and enzalutamide are commonly used oral cancer therapies for patients with prostate cancer, both with potentially high out-of-pocket costs for patients. We investigated the prevalence of financial assistance mechanisms used to alleviate out-of-pocket costs and the association of these mechanisms with timing of treatment initiation of abiraterone or enzalutamide.

METHODS:

Using data from the medical center's specialty pharmacy, we identified first prescriptions for abiraterone or enzalutamide between January 1, 2017, and March 31, 2019. Prescriptions dispensed at an external pharmacy or that were discontinued for reasons unrelated to cost were excluded. Patient demographics, insurance coverage, out-of-pocket cost, and number of days between prescribed date and pill-to-mouth date were collected.

RESULTS:

Among 220 prescriptions in our final cohort, 185 were filled through our internal specialty pharmacy, 23 through a manufacturer-sponsored patient assistance program (PAP), and 12 were never filled because of cost. One third of the prescriptions in our final cohort (n = 66) were filled with financial assistance: PAP (10%), copay cards (9%), and grants (11%). The median amount of assistance received for the first fill was $2,860 US dollars (USD) (interquartile range $1,856-$10,717 USD). Prescriptions with an out-of-pocket cost < $100 USD were filled in the shortest time (median 5 days), whereas those filled through a PAP had the longest time to initiation (median 30.5 days).

CONCLUSION:

Among patients prescribed oral therapies for prostate cancer at a single institution, one third of patients received financial assistance. Although receiving assistance is likely to improve financial toxicity, waiting for assistance may lead to longer time to initiation of medication.

INTRODUCTION

Financial toxicity is a well-known problem for patients with cancer that has been associated with depression, poor quality of life, and higher mortality.1-8 Oral cancer therapies, in particular, can contribute to worsened financial toxicity because they are covered differently by insurance than injectables and patients may be responsible for more of the cost. In prostate cancer, for example, oral cancer therapies such as abiraterone and enzalutamide are commonly used expensive treatments with an average wholesale price > $10,000 US dollars (USD) for a 1-month supply.9,10

There are various financial assistance mechanisms available to relieve some of the financial burden on patients, including copay cards (provided by the drug manufacturer), patient assistance programs (PAPs) that provide the drug directly to the patient from the manufacturer free of charge, and grants (provided by private foundations, some of which receive funding from manufacturers). There is growing evidence to suggest that patient support programs such as PAPs and grant programs are crucial in improving access to care among patients with cancer, especially those without adequate health insurance.11-16 Previous investigators have analyzed patient out-of-pocket costs and financial relief provided through these assistance mechanisms and found that 36%-54% of all oral cancer prescriptions required at least one form of financial assistance, and PAPs specifically were used by 10%-30% of patients.17-20 Little is known about which patients are using these mechanisms, the differences in out-of-pocket costs among those who do not qualify for assistance, and whether or not these mechanisms are associated with delays in starting oral cancer therapies. Furthermore, those patients who do not qualify for assistance are not commonly included in prior studies to determine whether they filled their prescriptions or decided to forego treatment altogether.

Therefore, to fill these knowledge gaps, we investigated the prevalence of the different financial assistance mechanisms, the differences in out-of-pocket costs among patients receiving and not receiving assistance, and the effects of these mechanisms on treatment delays in a sample of men with advanced prostate cancer at an academic cancer center.

METHODS

Study Sample

Patients older than age 18 years who received first-time abiraterone or enzalutamide prescriptions in an academic cancer center from January 1, 2017, through March 31, 2019 were identified. We selected January 1, 2017 as a start date because of implementation of an internal comprehensive pharmacy reporting database starting on that date. We excluded 130 patients whose prescriptions were discontinued by the provider before the fill for reasons unrelated to cost (eg, trial participation or provider preference), and those patients whose prescriptions were handled by external specialty pharmacies since we were unable to verify copay and copay assistance data.

Data Sources

We used an electronic health record system to identify patient characteristics, prescription date, pill-to-mouth date, pharmacy used to fill first-time prescription, financial assistance mechanisms used, and out-of-pocket costs. A NRx pharmacy management system, a web-based pharmacy management system that tracks all prescriptions for oral chemotherapy entered by providers within the cancer center, was also used to compile detailed reports of abiraterone and enzalutamide prescriptions that included information regarding financial assistance mechanisms used, out-of-pocket costs, and the amount of assistance received where applicable. Physical files kept by the oral chemotherapy pharmacy were used to obtain data regarding PAPs. The information provided through the NRx pharmacy management system was cross-referenced with information gathered from the electronic health record system, as well as with physical files kept by the oral chemotherapy program.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was to describe (1) the proportion of first-time prescriptions that were filled with financial assistance mechanisms, (2) those first-time prescriptions filled without assistance, and (3) those not filled at all because of cost. Assistance mechanisms used were collected through review of pharmacy financial coordinator notes in the electronic medical record and included three categories: copay cards, PAPs, and grants. Patients with commercial insurance are generally offered copay cards (provided by the drug manufacturer) to cover high out-of-pocket costs. Since patients with government health insurance, including Medicare and Medicaid, cannot use copay cards (which are prohibited by the anti-kickback statute), those who have an income below a designated threshold can take advantage of PAPs sponsored by pharmaceutical manufacturers. PAPs provide the drug directly to the patient from the manufacturer free of charge.21 For patients who do not qualify for PAPs or copay cards, grants can sometimes be obtained to cover high out-of-pocket costs, contingent on both patient qualifications and the availability of the grant; grants are dependent on donors and often become unavailable when funds become scarce.

Most patients who received assistance had little to no out-of-pocket payment. Therefore, only those prescriptions that did not require assistance were categorized by their out-of-pocket payment as less or more than $100 USD. We also identified those prescriptions that were not filled because of financial reasons. Prescriptions were categorized as never-filled when there was no fill of the prescription and no pursuit of financial assistance within 45 days of the date prescribed. These prescriptions were reviewed by a clinical team to determine whether they were never filled because of reasons related to cost or unrelated to cost.

Secondary outcomes were to describe (1) the amount of assistance received, (2) out-of-pocket payment for patients who did not receive assistance, and (3) associations between the time from prescription to treatment initiation depending on whether a prescription was filled with or without assistance. Out-of-pocket payment and amount of assistance received were obtained through chart review and pharmacy management system reports. Patient out-of-pocket payment was the amount the patient paid after their insurance contribution and any financial assistance contribution. We expected privately insured patients to have fixed monthly copays and Medicare Part D–insured patients to have more varying out-of-pocket payments, given the cost-sharing structure. We also expected patients with Medicare Part D to have higher 30-day out-of-pocket payments compared to patients with private insurance. The time from prescription to treatment initiation was determined by evaluating the number of days between date prescribed and date of pill-to-mouth. Pharmacists from the cancer center routinely call every patient who is prescribed an oral cancer therapy to discuss the medication with them and confirm the date that they would start taking the medication. The pharmacists document a telephone note describing the encounter into the electronic health record so we can identify an accurate pill-to-mouth date by chart review of these telephone notes. We expected patients with commercial health insurance and out-of-pocket payments < $100 USD to have the shortest time between date prescribed and date of pill-to-mouth.

Covariates

We described patient characteristics including age, race, ethnicity, and type of insurance coverage. Two reviewers assessed a 10% sample of patients independently to ensure consistency of chart review and data abstraction.

This study was exempted by the institutional review board.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to analyze our data. We calculated proportions for the patient characteristics of those who filled and did not fill their prescription. We calculated mean, median, and range for out-of-pocket payments and final out-of-pocket payments for patients who paid more than $0 USD. We described the number of days between date of prescription and pill-to-mouth among patients who did or did not receive financial assistance and depending on their assistance mechanism used. Finally, we used analysis of variance and Fisher's exact test to compare age, race, and insurance status for those patients who received or did not receive financial assistance.

RESULTS

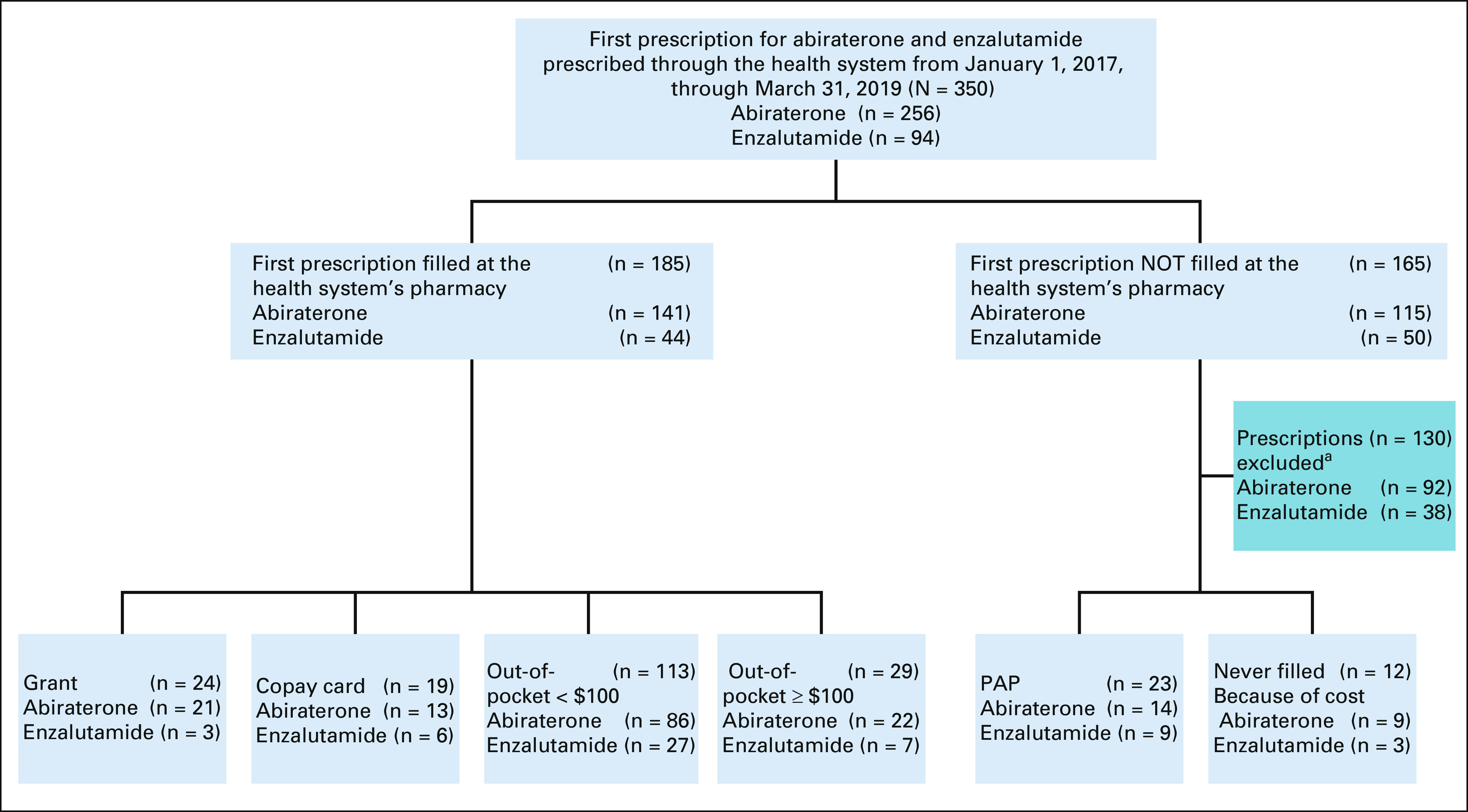

We identified 350 first-time abiraterone and enzalutamide prescriptions from January 1, 2017, through March 31, 2019. We excluded 130 first-time prescriptions that were handled by external pharmacies or that were discontinued before a fill was obtained for reasons unrelated to cost (eg, clinical trial participation or provider preference). There were some patients who received sequential abiraterone and enzalutamide prescriptions with our institution and thus were included in this analysis for both medications. Figure 1 details the cohort selection.

FIG 1.

Flowchart of the patient cohort. aPrescriptions were excluded if the first prescription was not filled at the internal specialty pharmacy or was never filled for reasons unrelated to cost. PAPs are also known as free drug programs that are provided by manufacturers to patients with low incomes who qualify. Grants are assistance mechanisms from private foundations to supplement high out-of-pocket costs to patients who have insurance. Copay cards are coupons provided to patients with commercial insurance from manufacturers to supplement high out-of-pocket patient costs. PAP, patient assistance program.

Prescriptions Filled With and Without Assistance Mechanisms

Table 1 outlines patient characteristics of those who received these prescriptions. The mean age of patients in the final cohort was 72 years. Most patients were White (80%), whereas 12% of patients were Black, 3% were Asian, and 5% were of unknown race. The majority had Medicare Part D as their prescription insurance (60%), whereas 35% had commercial insurance, 2% had Medicaid, and 3% did not have any prescription insurance at the time of their prescription.

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics and Financial Assistance Mechanisms Used by Patients With Prescriptions for Abiraterone or Enzalutamide From January 2017 Through March 2019

Thirty percent of the prescriptions in our final cohort were filled using a financial assistance mechanism. PAPs were used for 23 (10%) of first-time prescriptions. Grants were used to cover some of the costs of the drug and reduce the patient's out-of-pocket payment for 24 (11%) prescriptions, and copay cards were used to decrease or fully cover the patient's out-of-pocket payment for 19 (9%) of first-time prescriptions.

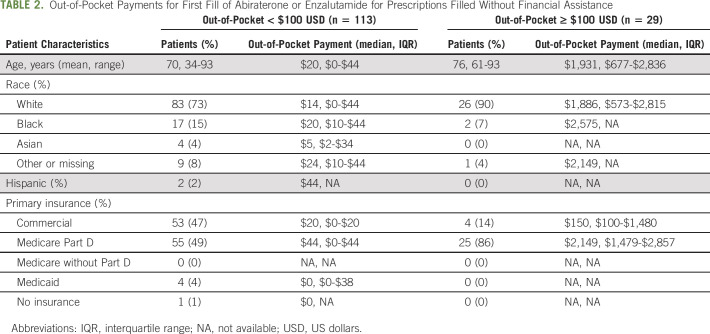

Among those prescriptions filled without financial assistance (n = 142), 80% had an out-of-pocket payment < $100 USD, 50% of which were filled with Medicare Part D. Among those with out-of-pocket payment ≥ $100 USD, 86% were filled with Medicare Part D. The type of financial assistance received and whether patients had an out-of-pocket cost < $100 USD or ≥ $100 USD varied significantly by age and primary insurance type. Those with Medicare Part D and older patients more often received PAPs, grants, or paid ≥ $100 USD out of pocket (P < .01; Table 1).

Among the 20% of prescriptions filled without assistance that still required out-of-pocket payments ≥ $100 USD (n = 29), the median out-of-pocket payment was $1,931 USD for the first month of therapy, ranging from $150 USD for those filled with commercial insurance to $2,149 USD for those filled with Medicare Part D (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Out-of-Pocket Payments for First Fill of Abiraterone or Enzalutamide for Prescriptions Filled Without Financial Assistance

Of note, generic abiraterone became available toward the end of our study timeframe. In our final cohort, 29 patients were prescribed generic abiraterone. The prevalence of assistance received and not received was similar to our overall results with 38% receiving financial assistance (six PAPs, five grants), 41% paying < $100 USD out of pocket, and 17% paying ≥ $100 USD out of pocket.

Prescriptions Unfilled Because of Cost

Five percent of the prescriptions in our final cohort were not filled at all because of cost. Among those that were not filled because of cost, 75% of those prescriptions were for patients with Medicare Part D.

Amount of Assistance Received

Among prescriptions filled with financial assistance, the median amount of assistance received was $2,860 USD (interquartile range [IQR] $1,792-$10,717 USD) for the first 30 days of therapy for either abiraterone or enzalutamide. PAP assistance provided the highest amount of assistance since it covered the entire cost of the drug (median, $11,318 USD; IQR $10,717-$12,417 USD). Similar to PAP assistance, grant assistance covered what would have been the entire out-of-pocket cost of the drug, so that patients ultimately had an out-of-pocket payment of $0 USD. However, since there was also insurance contribution among patients who received grants, the median amount of assistance received through grants was $2,427 USD (IQR $2,083-$2,794 USD). Patients who received assistance through copay cards received a median of $140 USD (IQR $59-$2,635 USD) in assistance. Most of these patients still paid some out-of-pocket after their financial assistance, but the copay cards brought their first-time payment down to $10 USD.

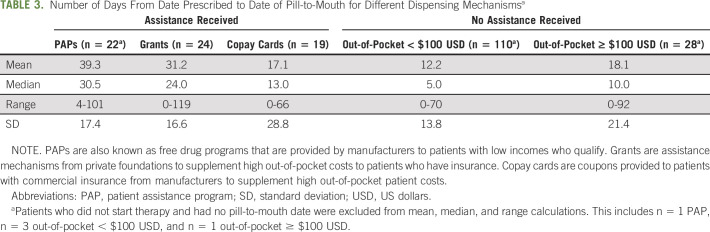

Time From Prescription to Treatment Initiation

Among the 203 medication starts, those who received their medication through a PAP experienced the greatest amount of time (mean 39.3 days, standard deviation 17.4) between date prescribed and date of pill-to-mouth. Patients who did not receive assistance and had an out-of-pocket payment < $100 USD had the shortest time from prescription to starting their therapy (mean 12.2 days, standard deviation 13.76; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Number of Days From Date Prescribed to Date of Pill-to-Mouth for Different Dispensing Mechanismsa

DISCUSSION

In this study, approximately one third of first-time prescriptions for abiraterone and enzalutamide filled through our academic center specialty pharmacy were obtained with additional financial assistance, suggesting that at least one third of patients would have had significant difficulty obtaining their prescription without financial support or may not have been able to fill at all. An additional 13% of patients paid ≥ $100 USD for their first fill and another 5% of prescriptions were never filled because of cost. Patients who received their drug through a PAP had to wait more than three times as long to start therapy after the prescription was written than did patients who were able to fill their prescription without a financial assistance mechanism and had an out-of-pocket payment < $100 USD.

Previous investigations have identified those with Medicare Part D and patients without insurance are those who require the most financial assistance for their oral cancer prescriptions.13-18 Patients in our study with Medicare Part D insurance were disproportionately represented among those who received the most assistance, specifically those patients who received PAPs or assistance through foundational grants. We also found prescriptions that went unfilled because of cost tended to be for those patients who had Medicare Part D or were uninsured, a finding that has not previously been investigated. Finally, patients with Medicare Part D who did not receive assistance paid the most out-of-pocket. Among patients who did not receive assistance and had to pay ≥ $100 USD out-of-pocket, the median amount paid for their first prescription for those with Medicare Part D was more than 10× the amount paid by patients with commercial insurance. What likely separates those patients with Medicare Part D who paid substantial amounts out-of-pocket from those who received assistance through PAPs or grants is their household income. Patients with incomes above a certain threshold do not qualify for financial assistance and thus must make the decision about whether they will pay the steep out-of-pocket costs or forego their treatment altogether.

It is not surprising that patients in our study who used assistance mechanisms had the longest wait time between date prescribed and date of pill-to-mouth. For patients who require assistance, the oral oncolytic team in our specialty pharmacy coordinates application completion between manufacturer and patient and collects signed documents from patient and provider. By contrast, those patients with low up-front out-of-pocket costs who did not need to go through the paperwork associated with financial assistance mechanisms experienced the shortest time between date prescribed and date of pill-to-mouth. These assistance mechanisms likely allowed some patients access to treatment who may not have had it otherwise, but at the cost of a delayed start of treatment. The median time to fill was six times longer for patients who needed PAPs to fill their prescription compared to those who filled their prescription with an out-of-pocket cost < $100 USD. Prior work has demonstrated longer times to fill for patients who received financial assistance, but the difference was much lower (2 days) and included all prescriptions for a patient rather than the first prescription.15 We would expect the first prescription for a new medication to be the most delayed because of the first-time PAP and grant applications that are required at treatment start, which may explain why the time to fill in our study was so much longer.

One limitation of this study was our exclusion of prescriptions filled through external specialty pharmacies. Since we did not have access to what patients paid out-of-pocket to external specialty pharmacies and potential assistance received by those patients, we felt it was important to exclude those patients without complete information. Although these data are not available to us, it is possible that patients who filled at external pharmacies may be required to fill at these external pharmacies through a commercial insurer. If commercially insured patients are over-represented in the excluded cohort and Medicare Part D patients over-represented in our sample, the distribution of the financial assistance mechanisms may shift slightly, but the overall proportion of patients requiring assistance is likely to be similar. Nevertheless, the findings in our sample still have important implications for all patients with Medicare Part D, the most common payer in men with advanced prostate cancer, where the average age is 72 years. Another limitation to consider is we did not have details on patient income. Only patients who sought out and applied for financial assistance shared their income with the team. Finally, it is possible that our findings may have underestimated the effects of Medicare Part D on financial burdens faced by our patient population due to our geographic proximity in Southeast Michigan and the prevalence of retirees from the three large automotive companies (General Motors, Fiat Chrysler, and Ford Motor Company) in our patient population. The three automotive companies each have subsidized retirement plans that reduce out-of-pocket costs for many of the patients with Medicare Part D on our study; thus, we may have seen more of a difference between commercially insured patients and those with Medicare Part D in out-of-pocket payments since the contribution from these companies would substantially lower what was required from the patient.

Our findings provide greater insight into the role of financial assistance mechanisms in a patient's experience when pursuing oral cancer therapies, which has broad implications for multiple stakeholders involved in the patient's care. For policymakers, it is critical that the current cost-sharing design of Medicare Part D be restructured since the current coverage provides inadequate protection to patients with cancer and instead causes these patients to be disproportionately affected by high out-of-pocket costs from oral cancer therapies. For health care teams, unfortunately, the active pursuit of financial resources alongside the patient has become crucial for many patients to receive their treatment. Thus, until drug pricing and benefit designs are reformed, it remains necessary to invest significant resources toward financial navigation for patients to ensure access to adequate treatment. This investment of resources may come in the form of advocating for a dedicated financial assistance team within the health center or formulating step-by-step measures for financial assistance applications for patients. Finally, the patient population affected by our findings will continue to expand as our population continues to age and medications for prostate cancer continue to expand in their indication.22 Moreover, it is important to recognize that the delays of financial approval of preferred therapies may lead to substitution of cheaper but potentially less-effective therapies. Patients and providers who seek urgent treatment and do not want to risk waiting over a month to receive a specific medication through a PAP may find themselves pursuing alternative treatment, which could be considered less effective care. As we continue to explore the financial barriers to access to and timely receipt of oral cancer therapies, we hope that navigation of patient access to these medications will be better understood and ultimately improved.

Andrea R. Roman

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie/Genentech, Karyopharm Therapeutics

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

M.E.V.C. is funded by a Prostate Cancer Foundation Young Investigator Award and by National Cancer Institute Grant Numbers R37CA222885 and R01CA242559.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Angelina Y. Jeong, Eric B. Schwartz, Andrea R. Roman, Rachel L. McDevitt, Elyssa Henry, Megan E.V. Caram

Financial support: Megan E.V. Caram

Provision of study materials or patients: Megan E.V. Caram

Collection and assembly of data: Angelina Y. Jeong, Eric B. Schwartz, Andrea R. Roman, Elyssa Henry, Megan E.V. Caram

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Characterizing Out-of-Pocket Payments and Financial Assistance for Patients Prescribed Abiraterone and Enzalutamide at an Academic Cancer Center Specialty Pharmacy

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Andrea R. Roman

Consulting or Advisory Role: AbbVie/Genentech, Karyopharm Therapeutics

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kale HP, Carroll NV: Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer 122:283-289, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, et al. : Population-based assessment of cancer survivors' financial burden and quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract 11:145-150, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. : Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the Comprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST). Cancer 123:476-484, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al. : Association of financial strain with symptom burden and quality of life for patients with lung or colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:1732-1740, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta D, Lis CG, Grutsch JF: Perceived cancer-related financial difficulty: Implications for patient satisfaction with quality of life in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 15:1051-1056, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaisaeng N, Harpe SE, Carroll NV: Out-of-pocket costs and oral cancer medication discontinuation in the elderly. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 20:669-675, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farias AJ, Hansen RN, Zeliadt SB, et al. : The association between out-of-pocket costs and adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy among newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Am J Clin Oncol 41:708-715, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. : Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:980-986, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.RED Book. 2020. www-micromedexsolutions-com.proxy.lib.umich.edu [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong SE, Everest L, Jiang DM, et al. : Application of the ASCO value framework and ESMO magnitude of clinical benefit scale to assess the value of abiraterone and enzalutamide in advanced prostate cancer. JCO Oncol Pract 16:e201-e210, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker L, Shaul A, Murphy B, et al. : Effectiveness of a patient support program in supporting access to therapy for solid tumor malignancies. J Health Econ Outcomes Res 3:107-121, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson PE: Patient assistance programs and patient advocacy foundations: Alternatives for obtaining prescription medications when insurance fails. Am J Health Syst Pharm 63:S13-S17, 2006. (21 suppl 7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farano JL, Kandah H-M: Targeting financial toxicity in oncology Specialty Pharmacy at a large tertiary academic medical center. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 25:765-769, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan G, Karabon P, Lerchenfeldt S: Use of prescription assistance programs after the Affordable Health Care Act. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 24:247-251, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yezefski T, Schwemm A, Lentz M, et al. : Patient assistance programs: A valuable, yet imperfect, way to ease the financial toxicity of cancer care. Semin Hematol 55:185-188, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felder TM, Lal LS, Bennett CL, et al. : Cancer patients' use of pharmaceutical patient assistance programs in the outpatient pharmacy at a large tertiary cancer center. Community Oncol 8:279-286, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zullig LL, Wolf S, Vlastelica L, et al. : The role of patient financial assistance programs in reducing costs for cancer patients. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 23:407-411, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell A, Muluneh B, Patel R, et al. : Pharmaceutical assistance programs for cancer patients in the era of orally administered chemotherapeutics. J Oncol Pharm Pract 24:424-432, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olszewski A, Zullo A, Nering C, et al. : Use of charity financial assistance for novel oral anticancer agents. J Oncol Pract 14:e221-e228, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geynisman D, Meeker CR, Doyle JL, et al. : Provider and patient burdens of obtaining oral anticancer medications. Am J Manag Care 24:e128-e133, 2018 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.42 U.S.C. 1320A-7B—Criminal Penalties for Acts Involving Federal Health Care Programs. US Government Publishing Office website, 2010. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/granule/USCODE-2010-title42/USCODE-2010-title42-chap7-subchapXI-partA-sec1320a-7b [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caram MEV, Kaufman SR, Modi PK, et al. : Adoption of abiraterone and enzalutamide by urologists. Urology 131:176-183, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]