Abstract

In the process of physiological cardiac repair, splenic leukocyte-activated lipoxygenases (LOXs) are essential for the biosynthesis of specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators as a segment of an active process of acute inflammation in splenocardiac manner. In contrast, young 12/15LOX−/− mice use a compensatory mechanism that amplifies epoxyeicosatrienoic acid mediators after myocardial infarction, improving cardiac repair, function, and survival. Next, we tested whether deletion of 12/15LOX impacted the genesis of chronic inflammation in progressive aging. To test the risk factor of aging, we used the inter-organ hypothesis and assessed heart and spleen leukocyte population along with the number of inflammation markers in age-related 12/15LOX−/− aging mice (2 months, 6 months, 13 months) and compared with C57BL/6 J (WT; wild type) as controls (2 months). The 12/15LOX−/− aging mice showed an age-related increase in spleen mass (hypersplenism) and decreased marginal zone area. Results suggest increased interstitial fibrosis in the heart marked with the inflammatory mediator (PGD2) level in 12/15LOX−/− aging mice than WT controls. From a cellular perspective, the quantitative measurement of immune cells indicates that heart and spleen leukocytes (CD11b+ and F4/80+ population) were reduced in 12/15LOX−/− aging mice than WT controls. At the molecular level, analyses of cytokines in the heart and spleen suggest amplified IFN-γ, with reduced COX-1, COX-2, and ALOX5 expression in the absence of 12/15LOX-derived mediators in the spleen. Thus, aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice increased spleen mass and altered spleen and heart structure with activation of multiple molecular and cellular pathways contributing to age-related integrative and inter-organ inflammation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-021-00496-x.

Keywords: Aging, 12/15 lipoxygenases, Splenic leukocytes, Heart, Inflammation, Resolution, Lipid mediators

Introduction

Spleen is immune responsive leukocyte reservoir and is known for an inter-organ defensive role in coordinating inflammation and resolution responses after injury or infection [1]. In the process of physiological wound healing after cardiac injury, splenic leukocytes exit from the spleen and mobilize to the site of infarction to facilitate the biosynthesis of specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) and sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) that facilitate cardiac repair [2–4]. Immune responsive lipoxygenase (LOX; -5, 12, and -15) are major fat metabolic enzymes that regulate the biosynthesis of SPMs in the spleen and infarcted heart, thereby directing a safe clearance of inflammation in risk-free young mice [2, 5]. Obesogenic aging dysregulates LOX, amplifies proinflammatory mediators, lowers SPMs biosynthesis, and develops dysbiosis in cardiac healing in acute heart failure [6, 7]. In humans, splenectomy increases the risk of pneumonia, pulmonary hypertension, stroke, and ischemic heart disease [8, 9]. Moreover, clinically, aging is an inevitable and number one risk factor of cardiovascular disease; therefore, the interaction of aging and LOX remains of interest to define leukocytes phenotype-directed inflammation and cardiac function.

Splenic leukocyte-directed inflammation is a self-defense mechanism responding to injury, infection, and stress, but if the inflammation remains unresolved, it leads to non-resolving and chronic inflammation [10]. Aging is a prime risk factor that amplifies non-resolving inflammation when superimposed on other co-morbidity like obesity, environmental pollution/smoking, noise pollution, smoking, and sedentary lifestyle [11, 12]. Splenic leukocyte activates LOX-derived endogenous SPMs to facilitate cardiac repair post-myocardial infarction [2]. In contrast, genetic deletion 12/15LOX expedites cardiac repair via switching to cytochrome P450 (CYP) — pathway leading to biosynthesis of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs; cypoxins) in the heart, spleen, and plasma in young mice [2, 13, 14]. However, whether the mechanism of young mice cardiac repair preserved in aging of 12/5LOX-deficient mice remains of interest. Thus, next, we tested the hypothesis of how aging interacts with 12/15LOX deficiency to define the translational mechanism of our finding using age-related groups of monogenic mice. Compared to adult risk-free wild-type mice, 12/15LOX−/− mice develop age-related splenomegaly and marked dysregulation of mononuclear phagocyte network with signs of non-resolving inflammation and cardiac dysfunction. (1) The 12/15LOX deficiency in mice drives increased spleen mass and developed diastolic dysfunction, (2) decreased telomerase length, (3) dysregulated mononuclear phagocyte network by decreasing macrophages, and (4) reduced multiple immune responsive enzymes (COXs and LOXs) necessary for initiation of the host immune response.

Methods

Animals and ethical compliance

All animal procedures were conducted according to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (8th Edition, 2011), AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals (2013 Edition) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of South Florida, Tampa, FL. Risk-free male C57BL/6 (wild type (WT); Cat # 000,664) and 12/15LOX null mice (12/15LOX−/−; B6.129S2-Alox15tm1Fun/J; Cat # 002,778) on the C57BL/6 genetic background were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA) and were maintained under constant temperature (19.8–22.2 °C). The mice were given free access to water and a standard chow diet. 12/15LOX−/− were aged in house (institutional) colony during the pandemic time up to 6 months and 13 months that revealed spleen enlargement in 12/15LOX null mice.

High-resolution echocardiography

The diastolic and systolic function of the left ventricle of WT and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice was assessed using high-resolution ultrasound Vevo 3100 (VisualSonics Inc., Canada) echocardiography as previously described [15]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized using 0.8–1.5% isoflurane in a 100% oxygen mix. Electrocardiograms and heart rates were monitored using a surface electrocardiogram. Images were acquired using the 3100 in the Vivo imaging system equipped with probes up to 40 MHz and a resolution of 30 µm. The mouse was placed in the supine position on the adjustable rail to coordinate the ultrasound transducer. The transducer placement was maneuvered to obtain multiple views, such as parasternal LV long- and short-axis, apical four-chamber, and suprasternal views. Parasternal long-axis views were obtained by aligning the scan head at 30–45° counterclockwise to the head of the mouse. The images obtained included LV long-axis B mode, left atrium M-mode, and Doppler imaging of LV applying pulsed-wave Doppler. Parasternal short-axis B mode images were acquired by rotating ∼90° clockwise from the parasternal long-axis view. Pulsed-wave Doppler images of the mitral valve, viewed as an apical four-chamber view, were obtained by moving the scan head transverse at the lower left side of the thorax. Aortic valve velocity was obtained via a pulsed-wave Doppler image in suprasternal view [15, 16].

Necropsy and organ harvest analysis

Heart, mainly left ventricle sliced in three parts to utilize mid-cavity for histology and spleen, was collected as previously described [16, 17].

Heart and spleen histology and confocal microscopy

For structural examination of the heart and spleen, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was done as previously described [16]. Red pulp and white pulp areas were demarcated using dotted white lines. To measure the area of cardiomyocytes, Alexa Fluor® 647 conjugate of WGA (wheat gram agglutinin) was used as previously described [18]. Myocyte area was quantified from 5–6 high-power fields per section using ImageJ software (NIH). Data for each group were calculated from 30 cardiomyocyte sections and 4–5 mice/group [15, 16].

Collagen staining using picrosirius red staining

For collagen deposition measurement, particularly in the interstitial area, the LV mid-cavity was stained using picrosirius red (PSR) staining as detailed in previous reports [16].

Quantitative real-time PCR

For qPCR, reverse transcription was performed with 2.0 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript® VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Quantitative PCR for COX-1, COX2, ALOX-12, ALOX-15, ALOX-5, IFN-γ TNF-α, IL6, and TGF-β genes were performed using TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA) on master cycler ABI, 7900HT. Gene levels were normalized to Hprt-1 as the housekeeping control gene. The results were reported as 2−ΔCt (ΔΔCt) values. All the experiments were performed in duplicates with n = 6–8/group [2, 6, 16].

Flow cytometry

Single mononuclear cells were isolated from LV and spleen and were stained as previously described. The immune cell surface marker strategy is detailed in supplementary data [2, 6, 7, 13].

Mass spectrometric analysis of plasma and spleen lipid mediators

After necropsy, the snap frozen spleen tissues (~ 15 mg) from WT (2 months) and 13-month-old 12/15LOX−/− mice were homogenized in 1:9 ratio with 1 × PBS (pH 7.4) and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The samples were further extracted using solid phased extraction for targeted lipidomics using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry as described in previous reports [6, 7, 14].

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean + SEM and presented scatter dot plot. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple comparisons. For 2 group comparison, the Student’s t-test (unpaired) was applied, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

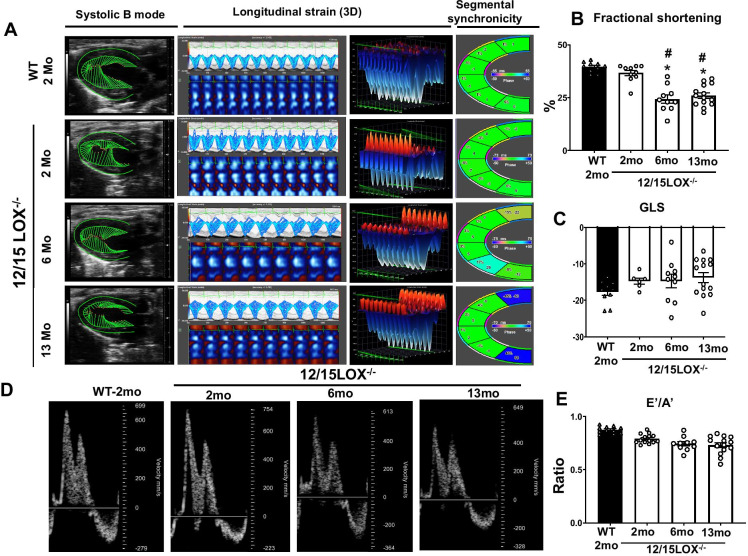

Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice leads to cardiac dysfunction

The number of reports indicates that increased 12/15LOX expression and activity correlated with chronic and unresolved inflammation [19, 20]. In contrast, previously, we reported that the genetic deficiency of 12/15LOX in adult mice improved post-MI function and limited fibrosis by programming leukocytes (neutrophils and macrophages) to reparative phenotype improved survival [13, 14, 18]. Here, we tested how deletion of 12/15LOX in mice impacts cardiac function and leukocyte phenotype in progressive aging. To evaluate the former, we used 2-, 6-, and 13-month-old 12/15LOX knockout (12/15LOX−/−) mice for our studies and compared them with young WT mice. First, we assessed the cardiac function using echocardiography. Longitudinal heart function data showed that fractional shortening (FS) in 12/15LOX−/− mice start decreasing at the 6 months of age with consistent decrease till 13 months (p < 0.5) compared with 2 months of WT and 2-month-old 12/15LOX−/− mice (Fig. 1A, B; Table 1). However, no significant difference was noted in global longitudinal strain (GLS) from 2 to 13 months of age in 12/15LOX−/− mice and 2-month WT (Fig. 1C). Along with systolic function, we also determine whether 12/15LOX−/− mice also develop diastolic dysfunction in progressive aging. For this, 2-month WT are progressively compared with 12/15LOX−/− aging mice using Doppler echocardiography. Obvious age-related trends were noted with signs of diastolic dysfunction (E′/A′) between 2 month-WT control and 12/15LOX age-progressive mice (Fig. 1D, E; Table 1). Our results suggest that progressive aging in 12/15LOX−/− mice adversely impacted the heart with signs of ventricular dysfunction in progressive aging.

Fig. 1.

Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice develops cardiac dysfunction. (A) Representative echocardiographic images are displaying B mode systolic function, longitudinal strain, and segmental synchronicity in male C57BL/6 (WT; 2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− (2 months, 6 months, and 13 months) mice. Graph representing (B) fractional shortening (FS). (C) Global longitudinal strain (GLS). (D) Representative echocardiographic images displaying diastolic function. (E) Graph E′/A′ ratio in synchrony in WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− (2 months, 6 months, and 13 months) mice. Data is representative of average ± SEM; n = 10–15/group; *p < 0.05 vs. WT (2 months), #p < 0.05 vs. 12/15LOX−/− (2 months) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

Table 1.

Echocardiography parameters in WT and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice

| WT (2 months) | 12/15LOX−/− (2 months) | 12/15LOX−/− (6 months) | 12/15LOX−/− (13 months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 10 | 10 | 10 | 14 |

| Body weight (g) | 25 ± 1 | 21 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 471 ± 12 | 499 ± 14 | 435 ± 16 | 462 ± 12 |

| EDD (mm) | 3.8 ± 0.07 | 3.5 ± .08 | 3.9 ± 0.09 | 3.9 ± 0.09 |

| ESD (mm) | 2.3 ± 0.07 | 2.2 ± .09 | 2.9 ± 0.08 | 2.9 ± 0.08 |

| Fractional shortening (%) | 39 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 26 ± 1*# | 26 ± 1*# |

| PWTs (mm) | 1.09 ± 0.03 | 1.03 ± 0.02 | 1.16 ± .07 | 1.08 ± 0.04 |

| GLS (%) | − 20 ± 1 | − 15 ± 2 | − 15 ± 2 | − 14 ± 2 |

| EDV (µl) | 49 ± 3 | 44 ± 3 | 56 ± 3*# | 68 ± 4*# |

| ESV (µl) | 21 ± 2 | 25 ± 2 | 29 ± 3 | 33 ± 2*# |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 58 ± 3 | 44 ± 2 | 49 ± 3 | 52 ± 2 |

| E/A | 1.6 ± 0.09 | 1.3 ± 0.04 | 1.4 ± 0.08 | 1.4 ± 0.05 |

Values are mean ± SEM; n indicates sample size. bpm beats per minute, EDD end-diastolic dimension, ESD end-systolic dimension, ESV end-systolic volume, EDV end-diastolic volume, GLS global longitudinal strain, PWT Posterior wall thickness, S systole, mm millimeter, E velocity of early mitral flow, A velocity of late mitral flow. *p < 0.05 vs. day 0 wild-type (WT 2 months) l; #p < 0.05 vs. 12/15LOX−/− 2 months

Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice progressively developed splenomegaly with interstitial fibrosis in the heart

Lack of 12/15LOX drives the compensatory biosynthesis of EETs in the spleen, plasma, and infarcted heart after ischemic insult [13, 14]. Splenic leukocyte LOX and cytochrome P450 epoxygenase activation is critical for cardiac repair [2]. The reports have stated that 12/15LOX−/− mice develop moderate splenomegaly [21]. Thus, we asked whether spleen size changes can correlate with chronic heart inflammation in 12/15LOX−/− mice during progressive aging. Interaction of progressive aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice from 2 to 13 months of age show increased spleen mass as signs of splenomegaly compared with 2-month WT controls. Histological examination of the spleen showed a change in splenic architecture with a remarkable decrease in follicles and disruption in the red and white pulp compartmentalization. Though disruption in red and white pulp compartmentalization was observed in 2 months of 12/15LOX−/− mice, the disruption in compartmentalization (hyperplasia) increased with advanced age. At 13 months, 12/15LOX mice spleen showed complete hyperplasia compared with 2-month WT and 12/15LOX−/− mice (Fig. 1A and D). We also examined the LV structure using wheat gram agglutinin (WGA) to measure cardiomyocyte area and picrosirius red (PSR) staining to determine myocardial collagen density. PSR-stained matrix data suggested that 6- and 13-month-old 12/15LOX−/− mice had more significant interstitial matrix deposition than 2-month 12/15LOX−/− and WT. The interstitial collagen content increase in 13 months in 12/15LOX−/− mice indicated an accelerated fibrotic response due to progressive aging (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. 2A). However, cardiac size measurement revealed a limited change in cardiomyocyte area of 12/15LOX−/− mice from 2 to 6 months stained by WGA compared with WT 2 months of age; however, 13-month-old 12/15LOX−/− mice showed a significant increase in cardiomyocyte area (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Fig. 2A). Age-related molecular markers suggest that aging primarily shortens telomere length, indicating the sign of senescence and marker of shortening lifespan [22]. At 2 months, WT and 12/15LOX−/− mice have similar telomerase lengths. However, the aging of 12/15LOX mice showed a significant decrease in telomerase length in splenic tissue at the age of 6 months, and 13 months compared with 2 months of 12/15LOX−/− mice (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2E). Interestingly, the splenic mRNA expression of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (TERT) was lower in 12/15LOX−/− mice at the age of 2 months compared with 2-month WT mice (Fig. 2F). These results signify that aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice develop profound splenomegaly and increase markers of premature aging with marked interstitial fibrosis of the heart.

Fig. 2.

Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice progressively developed splenomegaly with interstitial fibrosis in the heart. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained images of the spleen showing sequential changes in splenic remodeling in 12/15LOX−/− aging mice, particularly distorting the germinal center, marginal zones (MZs), and red pulp (RP) and white pulp (WP). (B) Picrosirius red (PSR)-stained interstitial fibrosis in left ventricular (LV) of 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. × 1.25 images of LV mid-cavity. (C) LV representative wheat gram agglutinin (WGA)-stained images display increased cardiomyocyte area in 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. Scatter plot displaying changes in (D) spleen weight. (E) Telomerase length. (F) TERT in the spleen of WT (2 months) and aging 12/15LOX−/− mice. Scale bar = 50 µm. Magnification: × 10 for spleen; 40X for LV. n = 7–8 mice/group for hematoxylin and eosin staining, n = 4 for immunofluorescence, n = 6 for RT PCR. Data is representative of average ± SEM; *p < 0.05 vs. WT (2 months), #p < 0.05 vs. 12/15LOX−/− (2 months) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

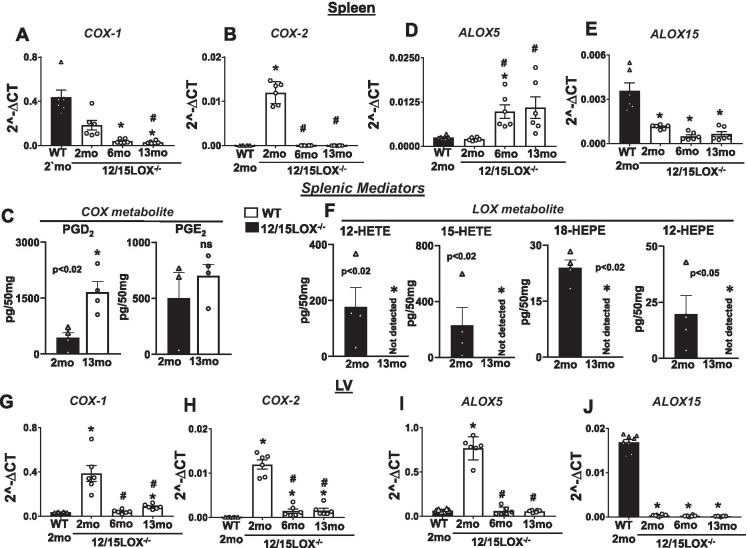

Aging of 12/15LOX-deficient mice dysregulated COXs and LOXs and respective lipid mediators in splenocardiac manner

12/15LOX−/− mice shift arachidonic metabolism towards cytochrome epoxygenase-derived bioactive mediators termed cypoxins in heart, plasma, and spleen to augment post-ischemic cardiac repair [13, 14]. Since deletion of 12/15LOX in aging leads to splenomegaly in mice, we aim to determine COX and LOX mRNA expression changes and their respective metabolites in splenocardiac manner. The COX-1 expression gradually decreased from 2 to 13 months in the spleen of 12/15LOX−/− mice compared with 2-month WT controls (Fig. 3A). However, the mRNA expression of COX-2 increased (p < 0.05) in the spleen of 12/15LOX−/− mice at 2 months compared with age-matched WT, but at the age of 6 months and 13 months, mRNA expression of COX-2 was downregulated (p < 0.05) compared to 2-month 12/15LOX−/− spleen (Fig. 3B). In alignment with gene expression, the levels of COX metabolite PGD2 were significantly increased (p < 0.05) in 13-month 12/15LOX−/− compared with 2-month WT with a non-significant increase in PGE2 (Fig. 3C). The mRNA expression of ALOX5 at 2 months was similar in both WT and 12/15LOX−/− mice; however, the mRNA levels of ALOX5 increased at 6 months and 13 months in the spleen (Fig. 3D), a possible compensatory increase with aging and evident lower levels of ALOX15 (Fig. 3E). Interestingly, 12/15LOX metabolites such as 12-HETE, 15-HETE, 18-HEPE, and 12-HEPE remained undetected in the spleen of 12/15LOX−/− mice compared to 2-month WT controls suggestive of limited LOX activity (Fig. 3F). In LV, mRNA levels of COX-1, COX-2, and ALOX5 were increased in 12/15LOX−/− in 2-month mice compared with 2-month WT. The LV showed lower COX-1, COX-2, and ALOX5 and obvious no detection of ALOX15 expression due to absence of 12/15LOX (Fig. 3G–I) compared with WT 2-month controls. Targeted lipid mediator analyses suggest that the absence of 12/15LOX dysregulated COX and LOX expressions and their respective metabolites in the spleen and heart in aging.

Fig. 3.

Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice dysregulated COX and ALOX5 mRNA expressions and respective lipid mediators in splenocardiac manner. mRNA expressions of (A) COX-1 and (B) COX-2 in spleen WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. *p < 0.05 vs. WT (2 months), #p < 0.05 vs. 12/15LOX−/− (2 months) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (C) Representative graph showing COX metabolites: PGD2 and PGE2 in the spleen of WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− (13 months) mice. The quantitative outcome of lipid mediators was reported as pg/50 mg of the spleen. The detection limit was ~ 1 pg. *p < 0.05 compared to WT (2 months) by Student’s t-test. mRNA expressions of (D) ALOX5 and (E) ALOX15 in spleen WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. *p < 0.05 vs. WT (2 months), #p < 0.05 vs. 12/15LOX−/− (2 months) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (F) Representative graph showing LOX metabolites: 12-HETE, 15-HETE, 18 HEPE, and 12-HEPE in the spleen of WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− (13 months) mice. The quantitative outcome of lipid mediators was reported as pg/50 mg of the spleen. The detection limit was ~ 1 pg. *p < 0.05 compared to WT (2 months) by Student’s t-test. mRNA expressions of (G) COX-1, (H) COX-2, (I) AlOX5, and (J) ALOX15 in LV WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. *p < 0.05 vs. WT (2 months), #p < 0.05 vs. 12/15LOX−/− (2 months) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

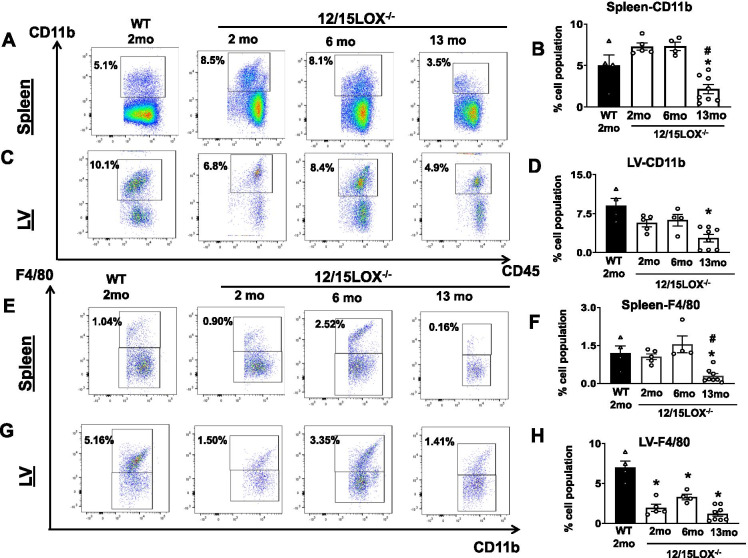

Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice lowered spleen and heart monocyte/macrophage network

Splenic leukocytes (monocytes/macrophages) are essential for cardiac healing, and aging is a prime contributor that impacts macrophage number [23]. As shown before, young 12/15LOX−/− mice have an abundant leukocyte pool that biosynthesizes differential lipid mediators in response to myocardium injury [14]. Here, we evaluated the impact of aging on overall monocytes (CD45+CD11b+) and macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+) population in the spleen and heart in 12/15LOX−/− mice compared with WT 2-month mice. The average monocyte content (CD45+CD11b+) in the spleen of 12/15LOX−/− 2-month controls was noted 7.2 ± 0.4% compared with WT age-matched controls having 4.9 ± 1.3% cells. CD45+CD11b+ population was reduced (2.1 ± 1.0%; p < 0.05) at 13 months of age compared with 2-month WT, 12/15LOX−/− 2-month and 12/15LOX−/− 6-month-old mice in the spleen (Fig. 4A, B). A similar trend was noted in LV where (CD45+CD11b+) content lowered in 12/15LOX−/− aging mice compared to 2-month WT controls. Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice (13 months) showed lower average percentage of CD45+CD11b+ (2.7 ± 0.7%) compared with WT 2-month (9.0 ± 1.3%) and 12/15LOX−/− 2-month (5.6 ± 0.6%) mice (Fig. 4C, D). Heart and spleen do not display any statistical difference in the leukocyte population in 12/15LOX−/− 6-month mice compared WT 2-month and 12/15LOX−/− 2-month control. The splenic and LV macrophage evaluation was done by quantifying CD11b+/F4/80+ gated over CD45+ cells. No difference was noted in the CD11b+/F4/80+ population in the spleen of 12/15LOX−/− 2-month and 12/15LOX−/− 6-month-old mice compared to WT 2-month control. Nevertheless, the 13-month-old 12/15LOX−/− mice have a significantly lower population of CD11b+/F4/80+ cells (0.2 ± 0.1% vs. 1.1 ± 0.1% vs. 1.2 ± 0.3%) compared with 12/15LOX−/− 2-month and WT 2-month controls, respectively (Fig. 4E, F). However, it was noted that LV has a significantly lower macrophage number in 12/15LOX−/− 2-month (1.9 ± 0.4%) compared with WT 2-month control (5.2 ± 0.8%). Overall, a decrease in macrophages was noted in both 6- and 13-month-old 12/5LOX−/− mice compared with 2-month WT mice in LV but at 6-month 12/15LOX−/− a marginal increase in LV macrophage population was noted compared with 2-month 12/15LOX−/− (Fig. 4G, H). Presented results suggest that progressive aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice consistently decreases monocytes and macrophages in both LV and spleen.

Fig. 4.

Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice lowered monocytes and macrophages in splenocardiac manner. Representative flow cytometry (fluorescence-activated cell sorting [FACS]) pseudo plots and scatter plots showing the monocyte population (CD11b+) in (A and B) spleen and (C and D) LV of WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. Representative FACS pseudo plots and a bar graph showing the macrophage population (F4/80+) in (E and F) spleen and (G and H) LV of WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. Data is representative of average ± SEM; n = 4–8 mice/group. *p < 0.05 vs. WT (2 months), #p < 0.05 vs. 12/15LOX−/− (2 months) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

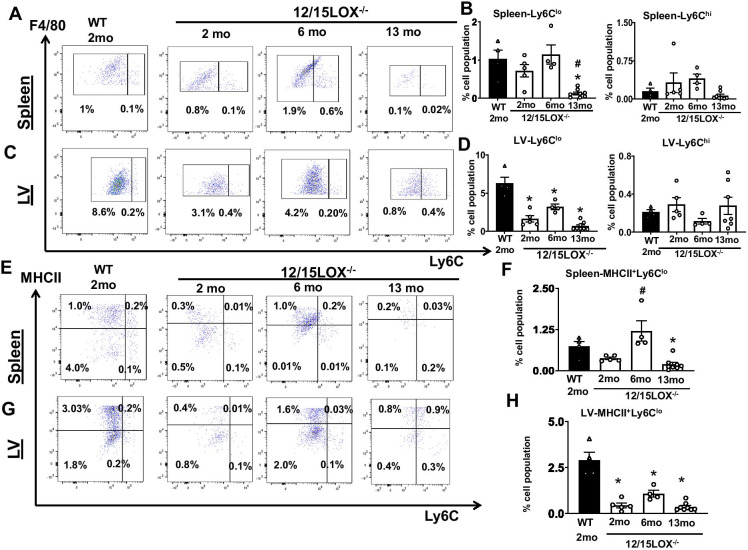

Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice modulates macrophage subset in splenocardiac network

Macrophages reside virtually in every tissue and are critical for homeostasis and stress-induced response [24]. Residential macrophages are Ly6Clo in nature that express different levels of MHCII to self-proliferate locally [25]. Since 12/15LOX−/− aging mice have a relatively lower number of monocytes and macrophages, we determined macrophage status subsets. The quantification of Ly6Clo and Ly6Chi macrophages in the spleen showed no significant difference in Ly6Clo population WT 2-month and 12/15LOX−/− mice at 2 months and 6 months of age. However, in 13-month 12/15LOX−/− spleen, Ly6Clo cells were significantly lower (0.1 ± 0.03%) than WT 2-month and the rest of 12/15LOX−/− spleen. However, no difference was noted in Ly6Chi macrophages in spleen (Fig. 5A, B). In LV, the percentage of Ly6Clo macrophage subset was significantly lower in 12/15LOX−/− mice from 2-month (1.6 ± 0.2%), 6-month (3.2 ± 0.4%), and 13-month (0.7 ± 0.2%) age compared with WT 2-month control (6.2 ± 0.8%) (Fig. 5C, D). An increase of Ly6Clo macrophage in 6-month 12/15LOX aging mice suggests adaptive increase before the maladaptive decrease in reduced macrophage number compared with 13 months. We further determined the MHCII+ subset on the Ly6Clo population in aging mice. The 2-month-old WT and 12/15LOX−/− do not show any significance in the MHCII+/Ly6Clo population. The 6-month-old 12/15LOX mice−/− significantly increased the MHCII+Ly6Clo population (1.2 ± 0.3%) compared with 12/15LOX−/− 2-month (0.4 ± 0.03%) mice. The splenic MHCII+Ly6Clo population decreased in aging 13 months (0.2 ± 0.06%) compared with WT 2-month control (Fig. 5E, F). However, in LV, 12/15LOX−/− mice have a lower MHCII+Ly6Clo population from 2 to 13 months of age than WT 2 months of mice (Fig. 5G, H). These results indicate that deficiency of 12/15LOX limits the local density of cardiac resident macrophages in progressive aging.

Fig. 5.

Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice dysregulates macrophage subset Ly6Clo/Ly6Chi in splenocardiac network. Representative FACS pseudo plots and scatter plot showing the macrophage phenotype (Ly6Clo and Ly6Chi) in (A and B) spleen and (C and D) LV of WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. Representative FACS pseudo plots and scatter plot showing the MHCII macrophage phenotype (MHCII+/Ly6Clo) in (E and F) spleen and (G and H) LV of WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. Data is representative of average ± SEM; n = 4–8 mice per group per day. *p < 0.05 vs. WT (2 months), #p < 0.05 vs. 12/15LOX−/− (2 months) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)

TH1/TH17 response was skewed in progressive aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice leading to non-resolving inflammation in 12/15LOX−/− mice

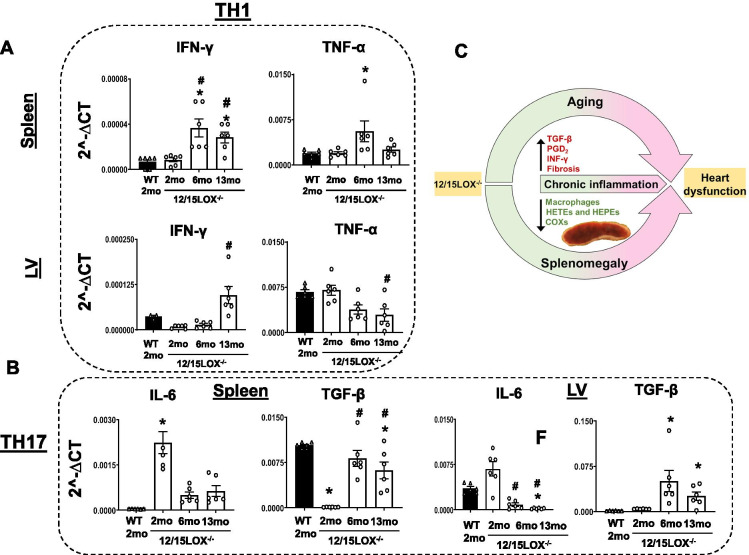

Deletion of ALOX15 is known to decrease Tregs [26]. We further determined whether 12/15LOX deletion impacts TH1 and TH17 cytokine response in progressive aging. Th1-type cytokines tend to produce the proinflammatory responses responsible for controlling intracellular parasites and perpetuating autoimmune responses, and excessive proinflammatory responses can lead to uncontrolled tissue damage [27]. Analyses of cytokine measurement suggest a significant increase in IFN-γ in spleen and LV of 13-month 12/15LOX−/− aging mice compared with 2-month WT and 12/15LOX−/− mice. Increased IFN-γ in 13-month 12/15LOX−/− correlate with dysfunctional macrophages in spleen. However, a decreasing trend was noted in TNF-α in both tissues compared with the other groups at the 13 months; however, the TNF-α was significantly increased in the spleen 6-month 12/15LOX−/− mice compared with other groups, a sign of maladaptive increase (Fig. 6A). Th17 cells are characterized by the production of IL-17 and may have evolved for host protection. Th17 differentiation in the mouse combines transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and IL-6 [28]. mRNA transcript analysis showed that IL-6 is significantly diminished due to aging (13 months) 12/15LOX−/− mice in the spleen and LV. In concord, there was a concomitant increase in TGF-β in both spleen and LV at 13-month mice compared with 2 months in 12/15LOX−/− mice (Fig. 6B). Our results indicated that progressive aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice caused asymmetrical changes to TH1/TH17 cytokines leading to non-resolving inflammation.

Fig. 6.

12/15LOX modulates TH1 and TH2 response in aging. (A) mRNA expression depicting TH1 response (IFNγ and TNFα) in LV and spleen of WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. (B) mRNA expression depicting TH17 response (IL6 and TGFβ) in LV and spleen of WT (2 months) and 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. Data is representative of average ± SEM; n = 6/group. *p < 0.05 vs. WT (2 months), #p < 0.05 vs. 12/15LOX−/− (2 months) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (C) Graphical sketch representing the impact of aging on heart function in 12/15LOX−/− mice in splenocardiac manner

Discussion

Age-related chronic inflammation is a primary risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and the role of the spleen and splenic leukocyte in cardiac health is becoming an interest to cardiovascular medicine [29, 30]. An observational study indicates that removing the spleen (splenectomy) increases the risk of acute myocardial infarction-related mortality noted on long-term follow-up in World War II veterans [9]. Rodent studies suggest that the spleen supplies leukocytes for cardiac repair after injury [2, 3]. Notably, we discovered that lipoxygenase is enriched in activated leukocytes in response to cardiac injury that is mobilized from spleen to heart and helps to biosynthesize endogenous resolution mediators [2]. A recent study suggests that spleen and heart S1P align together for cardiac repair as a sign of physiological process in young adult risk-free mice, however dysregulated in aging ischemic patients [4]. The presented report indicates that the aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice amplify (1) spleen size (splenomegaly), structure, and content; (2) cardiac dysfunction and signs of suboptimal inflammation; and (3) homeostatic decline of immune cell density, macrophages, and monocytes (Fig. 6C). Thus, the aging of 12/15LOX−/− increases spleen size that amplifies cardiac dysfunction discussed in three sections.

First, in clinical setting human splenic metabolic activity is indicative of future cardiac events [31]. At the same time, the pre-clinical reports indicate that activated splenic leukocyte-expressed 12/15LOX use the essential fatty acids and biosynthesize resolution mediators (SPMs) in response to cardiac injury [2]. Blockade or dysregulation of 12/15LOX impaired the cardiac repair post-MI in splenocardiac manner [32, 33]. In contrast, in the absence of 12/15LOX in mice, leukocytes increased levels of EETs in the spleen, heart, and plasma post-MI [13, 14, 34]. A compensatory increase of EETs improved survival, heart function, and activation of EP4 receptor in macrophages during the adult cardiac repair particularly in young mice [18]; however, aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice increased spleen mass and dysregulated splenic leukocyte phenotype. The aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice increased PGD2 as a sign of chronic inflammation and decreased 12- and 15-HEPE necessary for the biosynthesis of tri-hydroxy series resolution mediators. Adult cardiac repair and aging are two distinct factors that impact 12/15LOX activity, function, and leukocyte phenotypes that need additional and direct comparative investigation using age-matched controls.

Second, splenic monocyte-derived macrophages are prime contributors to cardiac repair. Our results document the interaction of aging and 12/15LOX deficiency. Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice shifts the leukocyte (monocyte/macrophages) towards inflammatory phenotype with pathological enlargement of the spleen. Removal of spleen (splenectomy) due to medical conditions in patients increases the risk of severe sepsis and blood clots [9]. Recent fate mapping and single-cell RNA sequencing studies indicate the multi-dimensional role of macrophages in steady-state and in response to injury [35], though aging as the main confounding risk factor remains understudied in leukocyte/macrophage biology. Aging itself leads to the structural de-compartmentalization of cell regions in the spleen, with the boundaries between these regions becoming less defined, impacting immune cell function, activation, and migration [36]. However, aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice enlarged spleen mass, disrupted marginal zone, and decreased telomere length and TERT with a reduced number of Ly6Clo macrophages in heart and spleen. Leukocytes originate in the bone marrow and are stored in the spleen for emergency release during an ischemic event such as a heart attack or stroke. More than 70–75% of splenic leukocytes mobilized to the heart for cardiac repair in response injury [3]. Histological observation suggests the disruption of the microarchitecture of the marginal zone area in 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. With aging, cardiac macrophages substituted by monocyte-derived macrophages indicate a possible risk of unresolved inflammation [37]. Thus, lack of 12/15LOX in mice adversely affects spleen mass, microarchitecture, leukocyte composition, and phenotype with signs of immunosenescence and suboptimal inflammation.

Third, age-related hematologic reports of 12/15LOX−/− mice indicate asymptomatic loss of leukocytes with the development of multiple cell-autonomous hematopoietic defects. In particular, the lymphocytes and monocytes are decreased with age; thus, 12/15LOX is essential for leukocyte number, proliferation, and function in response to infection or injury. 12/15LOX catabolizes AA to produce HETEs, HEPEs, and HDHA, indicating their pleiotropic action on essential fatty acids. As expected, 12/15LOX−/− mice showed undetected levels of 12/15 HETEs and 12/18HEPEs suggestive of a regulatory role in myelopoiesis and leukocyte action. Aging of 12/15LOX−/− mice diminished essential immune population, i.e., macrophages and monocytes required for first-line defense. Further, macrophages are more proinflammatory in phenotype, i.e., Ly6Chi indicative of inflammation in 12/15LOX−/− aging mice. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a crucial role in immune tissue homeostasis and self-tolerance; however, the decision to take the immune response in a specific direction is not made by one signal alone. Different elements act synergistically, antagonistically, and through positive feedback loops to activate a Th1, Th2, or Th17 immune response [38]. Th1 cells secrete the cytokine interferon (IFN)-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which allow these cells to be particularly effective in protecting against infections that grow in macrophages [39]. IL-6 is a pleiotropic cytokine involved in the physiology of virtually every organ system. IL-6 induces the generation of Th17 cells from naïve T cells together with TGF-β and inhibits TGF-β-induced Treg (iTreg) differentiation, which is critical in autoimmune disease [40]. Studies have shown that deletion of ALOX 15 reduces FOXP3 altered cellular metabolic pathways and the transcriptome of Tregs, further disrupting TH1 response and macrophage efferocytosis [26]. Aging in 12/15LOX−/− mice showed a reduced level of 1L-6 with an increase in TGF-β. Simultaneously, a synergistic increase in TH1 response cytokine IFNγ and with decrease in TNFα clearly showed an imbalance between TH1 and TH17 responses, which could be due to increased susceptibility to infection due to aging.

In summation, we found that progressive aging 12/15LOX−/− dwindled production of LOX metabolite HEPEs and HETEs but increased the COX metabolite PGD2, thereby altering the ratio of COX/LOX biomolecules required for homeostasis. The aging changed the spleen microarchitecture in 12/15LOX−/− mice and altered the immune cell population and their phenotypes. These observations support a central role for 12/15LOX in shaping the physiological properties of both innate and adaptive immune responses. As such, the present study uncovered the importance of immune responsive metabolic enzyme role in splenic leukocyte density (quality and quantity) and possible impact on cardiac health in aging; thus, future studies are warranted to consider the aging as primary risk factor in macrophage function.

Limitations

Young 2-month-old naive male C57BL/6 mice have limited changes in spleen size, mass, and structure in the absence of injury, aging, and infection [41]; however, use of male age-matched control groups is ideal for the precise and comparative outcome of aging 12/15LOX−/− mice. Another limitation is that we used only male mice; therefore, there will be some possible age-related differences in spleen microarchitecture of male and female 12/15LOX−/− aging mice that require further investigation. Possible interaction of activated leukocyte and cardiomyocyte/fibroblast may be a causative factor in fibrotic remodeling and suboptimal inflammation that warrants further investigation.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Fig. 1: Detailed flow cytometry strategy for LV and spleen mononuclear cells. Fig. 2: Aging of 12/15LOX-/- mice progressively increased fibrosis and cardiomyocyte area in the heart. (A). Scatter plot representing quantification of collagen density in left ventricular (LV) of 12/15LOX-/- aging mice. (B). Graph representing cardiomyocyte area of LV stained by wheat gram agglutinin (WGA). 4–5 images/mouse, n = 5 mice/group. Data is representative of average±SEM; *p<0.05 vs. WT (2mo), # p<0.05 vs. 12/15LOX-/- (2 mo) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (PPTX 99 KB)

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (HL132989 and HL144788) to GVH.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bronte V, Pittet MJ. The spleen in local and systemic regulation of immunity. Immunity. 2013;39(5):806–818. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halade GV, Norris PC, Kain V, Serhan CN, Ingle KA. Splenic leukocytes define the resolution of inflammation in heart failure. Sci Signal. 2018;11(520):eaao1818. 10.1126/scisignal.aao1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Swirski FK, et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325(5940):612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gowda SB, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate interactions in the spleen and heart reflect extent of cardiac repair in mice and failing human hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;321(3):H599–H611. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00314.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adel S, et al. Evolutionary alteration of ALOX15 specificity optimizes the biosynthesis of antiinflammatory and proresolving lipoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(30):E4266–E4275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604029113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halade GV, et al. Aging dysregulates D- and E-series resolvins to modulate cardiosplenic and cardiorenal network following myocardial infarction. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8(11):2611–2634. doi: 10.18632/aging.101077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kain V, Van Der Pol W, Mariappan N, Ahmad A, Eipers P, Gibson DL, et al. Obesogenic diet in aging mice disrupts gut microbe composition and alters neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio, leading to inflamed milieu in acute heart failure. FASEB J. 2019;33:6456–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Rorholt M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events and pulmonary hypertension following splenectomy — a Danish population-based cohort study from 1996–2012. Haematologica. 2017;102(8):1333–1341. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.157008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinette CD, Fraumeni JF., Jr Splenectomy and subsequent mortality in veterans of the 1939–45 war. Lancet. 1977;2(8029):127–129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(77)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serhan CN. Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature. 2014;510(7503):92–101. doi: 10.1038/nature13479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Otin C, et al. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Münzel T, et al. Environmental noise and the cardiovascular system. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(6):688–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halade GV, Kain V, Tourki B, Jadapalli JK. Lipoxygenase drives lipidomic and metabolic reprogramming in ischemic heart failure. Metabolism; 2019;96:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kain V, et al. Genetic deletion of 12/15 lipoxygenase promotes effective resolution of inflammation following myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;118:70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingle KA, et al. Cardiomyocyte-specific Bmal1 deletion in mice triggers diastolic dysfunction, extracellular matrix response, and impaired resolution of inflammation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309(11):H1827–H1836. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00608.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halade GV, Kain V, Ingle KA. Heart functional and structural compendium of cardiosplenic and cardiorenal networks in acute and chronic heart failure pathology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;314(2):H255–h267. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00528.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Y, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-28 deletion exacerbates cardiac dysfunction and rupture after myocardial infarction in mice by inhibiting M2 macrophage activation. Circ Res. 2013;112(4):675–688. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kain V, et al. Activation of EP4 receptor limits transition of acute to chronic heart failure in lipoxygenase deficient mice. Theranostics. 2021;11(6):2742–2754. doi: 10.7150/thno.51183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kayama Y, et al. Cardiac 12/15 lipoxygenase–induced inflammation is involved in heart failure. J Exp Med. 2009;206(7):1565–1574. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dioszeghy V, et al. 12/15-lipoxygenase regulates the inflammatory response to bacterial products in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181(9):6514. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Middleton MK, et al. Identification of 12/15-lipoxygenase as a suppressor of myeloproliferative disease. J Exp Med. 2006;203(11):2529–2540. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.AdwanShekhidem H, et al. Telomeres and longevity: a cause or an effect? Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(13):3233. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sager HB, Kessler T, Schunkert H. Monocytes and macrophages in cardiac injury and repair. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(Suppl 1):S30–s35. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.11.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosser DM, Hamidzadeh K, Goncalves R. Macrophages and the maintenance of homeostasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(3):579–587. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00541-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honold L, Nahrendorf M. Resident and monocyte-derived macrophages in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2018;122(1):113–127. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marques RM, Gonzalez-Nunez M, Walker ME, Gomez EA, Colas RA, Montero-Melendez T, et al. Loss of 15-lipoxygenase disrupts Treg differentiation altering their pro-resolving functions. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28:3140–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Berger A. Th1 and Th2 responses: what are they? BMJ. 2000;321(7258):424. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das J, et al. Transforming growth factor beta is dispensable for the molecular orchestration of Th17 cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 2009;206(11):2407–2416. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy SP, et al. Inflammation in heart failure: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(11):1324–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kain V, Prabhu SD, Halade GV. Inflammation revisited: inflammation versus resolution of inflammation following myocardial infarction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2014;109(6):444. doi: 10.1007/s00395-014-0444-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Emami H, et al. Splenic metabolic activity predicts risk of future cardiovascular events: demonstration of a cardiosplenic axis in humans. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(2):121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tourki B, et al. Lipoxygenase inhibitor ML351 dysregulated an innate inflammatory response leading to impaired cardiac repair in acute heart failure. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;139:111574. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halade GV, et al. Subacute treatment of carprofen facilitate splenocardiac resolution deficit in cardiac injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;104(6):1173–1186. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3A0618-223R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halade GV, et al. Interaction of 12/15-lipoxygenase with fatty acids alters the leukocyte kinetics leading to improved postmyocardial infarction healing. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;313(1):H89–h102. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00040.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaman R, Hamidzada H, Epelman S. Exploring cardiac macrophage heterogeneity in the healthy and diseased myocardium. Curr Opin Immunol. 2021;68:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner VM, Mabbott NA. Influence of ageing on the microarchitecture of the spleen and lymph nodes. Biogerontology. 2017;18(5):723–738. doi: 10.1007/s10522-017-9707-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Molawi K, et al. Progressive replacement of embryo-derived cardiac macrophages with age. J Exp Med. 2014;211(11):2151–2158. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaiko GE, et al. Immunological decision-making: how does the immune system decide to mount a helper T-cell response? Immunology. 2008;123(3):326–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02719.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lafaille JJ. The role of helper T cell subsets in autoimmune diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998;9(2):139–151. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6101(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mangan PR, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441(7090):231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aw D, et al. Disorganization of the splenic microanatomy in ageing mice. Immunology. 2016;148(1):92–101. doi: 10.1111/imm.12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. 1: Detailed flow cytometry strategy for LV and spleen mononuclear cells. Fig. 2: Aging of 12/15LOX-/- mice progressively increased fibrosis and cardiomyocyte area in the heart. (A). Scatter plot representing quantification of collagen density in left ventricular (LV) of 12/15LOX-/- aging mice. (B). Graph representing cardiomyocyte area of LV stained by wheat gram agglutinin (WGA). 4–5 images/mouse, n = 5 mice/group. Data is representative of average±SEM; *p<0.05 vs. WT (2mo), # p<0.05 vs. 12/15LOX-/- (2 mo) by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). (PPTX 99 KB)