Abstract

In the last decades, the scientific community spared no effort to elucidate the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs). Unfortunately, in vitro cellular senescence occurring along with a loss of proliferative capacity is a major drawback in view of future therapeutic applications of these cells in the field of regenerative medicine. Even though insight into the mechanisms of replicative senescence in human medicine has evolved dramatically, knowledge about replicative senescence of canine MSCs is still scarce. Thus, we developed a high-content analysis workflow to simultaneously investigate three important characteristics of senescence in canine adipose-derived MSCs (cAD-MSCs): morphological changes, activation of the cell cycle arrest machinery, and increased activity of the senescence-associated β-galactosidase. We took advantage of this tool to demonstrate that passaging of cAD-MSCs results in the appearance of a senescence phenotype and proliferation arrest. This was partially prevented upon immortalization of these cells using a newly designed PiggyBac™ Transposon System, which allows for the expression of the human polycomb ring finger proto-oncogene BMI1 and the human telomerase reverse transcriptase under the same promotor. Our results indicate that cAD-MSCs immortalized with this new vector maintain their proliferation capacity and differentiation potential for a longer time than untreated cAD-MSCs. This study not only offers a workflow to investigate replicative senescence in eukaryotic cells with a high-content analysis approach but also paves the way for a rapid and effective generation of immortalized MSC lines. This promotes a better understanding of these cells in view of future applications in regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-021-00488-x.

Keywords: Cellular senescence, High-content analysis, Canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells, Immortalization, Telomerase, BMI1 protein

Introduction

In the last decades, regenerative medicine has seen dramatic developments and potential for new therapeutic approaches [1]. Much of this promise relies on stem cells, and the discovery of somatic stem cells (SSCs) in various tissues. In recent years, the scientific community spared no effort to elucidate the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) for serious diseases such as orthopaedic disorders [2], cardiovascular problems [3], immune system ailments [4] and cancer [5], and several cell culture systems for human stem cells have become available.

As their name implies, MSCs originate from mesenchymal tissue. Irrespective of their occurrence in various body compartments, MSCs have two peculiar characteristics in common: the capability of self-renewal and the ability to differentiate into specific cell types [6]. Correspondingly, these multipotent cells are endowed with a great potential for many therapeutic approaches [7].

The main obstacle for the diffusion of MSCs in routine clinical applications is the qualitative heterogeneity of the cell preparations for lack of reproducibility and standardization of the in vitro culture conditions. This implies an extensive characterization of the cells prior to any clinical application. This, in turn, requires a considerable number of cells, which need to be produced only to enable their characterization [8]. However, notwithstanding the capability of MSCs to self-renew, the expansion of these cells under in vitro culture conditions is limited. Despite enhanced research efforts to address this problem, scientists are unanimous in conceding that cellular ageing, also called senescence, has remained a major obstacle to the development of therapeutic applications based on MSCs [9].

Senescence is a physiological process triggered by endogenous and exogenous stimuli. In principle, cells may either adapt and completely recover or undergo cell death as a response to stress-induced cell damage. Additionally, proliferating cells such as MSCs also have the capability to react to stressors by entering a state called cellular senescence [10]. This is an irreversible state of permanent cell-cycle arrest irrespective of sustained metabolic activity.

In vivo, this mechanism is related to ageing [11], but it also affects cells cultured in vitro. The so-called replicative senescence is a phenomenon seen in cell cultures that stop proliferating even though ideal growth conditions are still met. Senescent cells not only undergo proliferation arrest but also exhibit characteristic morphological and physiological features, including increased nuclear and cytoplasmic volumes, enhanced activity of the enzyme β-galactosidase, decreased expression of the cell cycle regulator protein polycomb ring finger proto-oncogene BMI1 (BMI1) and telomere shortening [12]. The major corollary of replicative senescence in cell cultures is the impossibility of expanding MSCs beyond a limited number of passages. Altogether, in vitro cellular senescence going along with a loss of proliferative capacity is a major drawback in view of future therapeutic applications of MSCs in the field of regenerative medicine.

It has been shown that senescence in primary cells may be circumvented by means of immortalization techniques [13]. Some of these techniques consist of upregulating natural cellular pathways. In this respect, promising results have been shown by upregulating the human telomerase reverse transcriptase enzyme (hTERT) [14] to counteract telomere shortening, or by upregulating the polycomb complex protein BMI1 [15], which is involved in cell cycle regulation [16]. In human adipose-derived MSCs (hAD-MSCs), the simultaneous overexpression of hTERT and BMI1 following consecutive exposure to two different lentiviral vectors has turned out to provide the best immortalization efficiency, in combination with a low impact on the cell phenotype [17].

Even though insight into the mechanisms of senescence in human medicine has evolved dramatically [18], knowledge about replicative senescence of canine (Canis lupus familiaris) MSCs is still very scarce [19–21]. Therapeutic use of stem cells in veterinary medicine has not yet progressed beyond pioneering work [22, 23]. Correspondingly, there is a great interest in this field [24], both for the importance of dogs as a model organism for human diseases in pre-clinical studies and for the relevance of dogs as a companion animal.

The aim of the present study was to provide specific knowledge on canine MSCs by characterizing canine AD-MSCs (cAD-MSCs) by means of a high-content analysis workflow. Our results show that these cells undergo phenotypical changes associated with replicative senescence similar to those that occur in their human counterparts. Furthermore, we designed a non-viral PiggyBac™ transposon system containing the human TERT and the human BMI1 coding sequences under the same promotor. This innovative approach enabled us to immortalize the cells and to prevent, to some extent, the occurrence of the senescent phenotype in cAD-MSCs.

Results

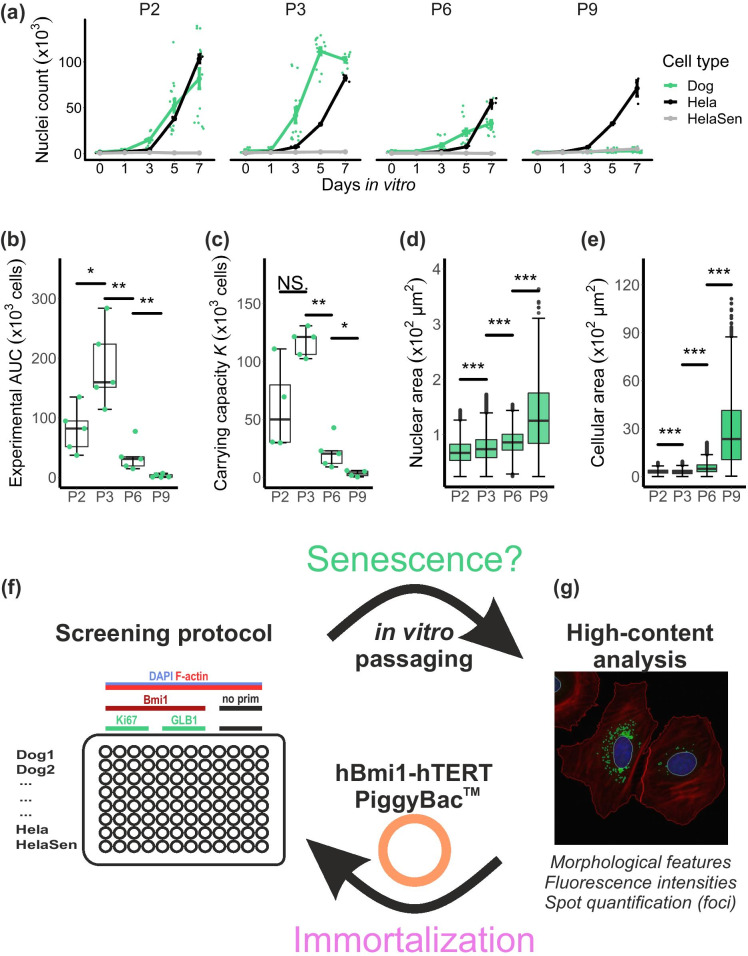

Proliferation rate of cAD-MSCs decreases with increasing number of passages

The proliferation assay corroborated a noticeable reduction in proliferation potential in cAD-MSCs over passages (five dog donors, age range 0.5–8 years). The number of nuclei counted at day in vitro 7 (DIV7) decreased progressively (Fig. 1a), and cAD-MSCs reached proliferation arrest at P9. This prevented the performance of any experiments at later passages. The proliferation characteristics at different passages were compared by quantifying the area under the experimental proliferation curve (eAUC) and the carrying capacity (K), which both first increased between P2 and P3, but then significantly decreased at every later passage measured (Fig. 1b and c). Consistently, the immortal control HeLa cells did not undergo proliferation arrest even at higher passages, while HeLa cells treated with 1 µM of the cytostatic drug camptothecin at DIV1 (HeLaSen) showed immediate proliferation arrest.

Fig. 1.

The proposed high-content analysis workflow demonstrates that in vitro passaging induces proliferation arrest and increased cell and nuclear size in cAD-MSCs. Logistic equations were fitted to cellular growth data (a), obtained by automated counting of nuclei in DAPI-stained micrographs over 7 days at different passages (P2-P9) (n = 5 biological replicates, mean ± s.e.m.). HeLa cells and HeLa cells treated with 1 µM camptothecin to induce senescence were assessed in parallel. The progressive reduction of the extrapolated area under the experimental proliferation curve eAUC (b) and the carrying capacity K (c) are in agreement with a decrease in proliferation capacity starting from P3. The analysis of cell morphology features revealed a significant increase of both nuclear (d) and cellular (e) size (2D-projected area) over passages. The high-content analysis workflow consists in a four-colour immunostaining and imaging screening method to study replicative senescence in a quantitative manner (f). cAD-MSCs that were obtained from five tissue donors and two controls (HeLa and HeLaSen) were processed and imaged in the same multi-well plate. Gene expression at the protein level of three proteins involved in replicative senescence was studied by immunostaining (BMI1, Ki67 and GLB1). Incubations without primary antibodies served as controls. DAPI staining of DNA and phalloidin staining of F-actin were used to identify morphological features of cAD-MSCs (g). The acquired micrographs were automatically segmented and cellular features were extracted and quantified using open-source software exclusively. After assessing senescence in cAD-MSCs over four passages, the efficacy of immortalization using a BMI1-hTERT-PiggyBac™ transfection vector was corroborated by repeating the screening procedure on “immortalized” cAD-MSCs. NS p > 0.05; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Scale bar = 50 µm

Late-passage cAD-MSCs present characteristic morphological features of senescent cells

In this study, the potential of high-content analysis was exploited to provide a complex picture of the effects of passaging on cAD-MSCs. To this end, we developed a workflow that allowed the simultaneous analysis of cells originating from different tissue donors, three proteins involved in senescence and numerous morphological features (Fig. 1f). This parallelization considerably reduced the experimental variability between samples. The workflow was used first to assess the appearance of a replicative senescence phenotype in cAD-MSCs, and later to evaluate the efficacy of a newly designed immortalization protocol to generate cAD-MSC lines (Fig. 1f and g). The image analysis pipeline included automated nuclei and cell segmentation, and the quantification of fluorescent signals. For this purpose, only open-source software was used (segmentation pipelines available as Supplementary Table S2).

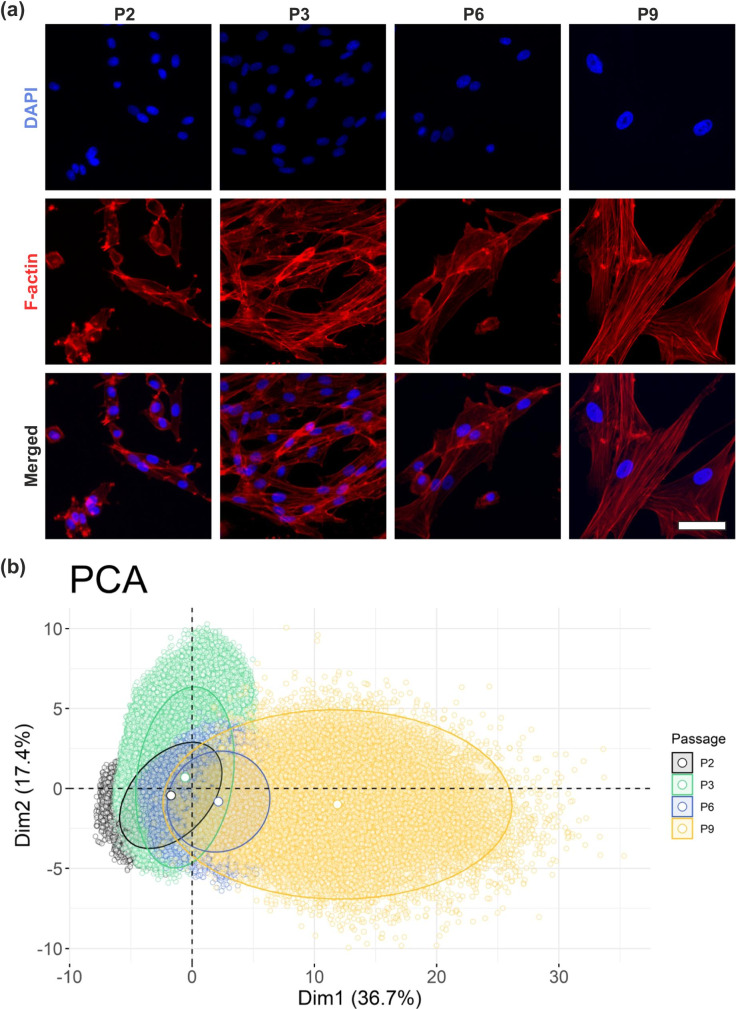

Nuclear and cellular areas measured in DAPI- and phalloidin-stained micrographs significantly increased in cAD-MSCs over each successively analysed passage. Over the entire experiment (passages P2–P9, which corresponds to 6–17 cumulative population doublings), a twofold increase in nuclear area and a ninefold increase in cell area were observed (Fig. 1d and e). In contrast, there were no significant differences in the measured parameters between cAD-MSCs from different tissue donors within the same passage (Supplementary Figure S1a and S1b). This allowed the pooling of cAD-MSCs results for further analysis. The enlarged nuclear and cellular areas of cAD-MSCs were already evident by visual inspection of the micrographs at different passages (Fig. 2a). The same was true for camptothecin-treated control HeLaSen cells, while untreated HeLa cells did not show morphological changes upon passaging (Supplementary Figure S1c).

Fig. 2.

High-content analysis reveals that cellular morphological features of cAD-MSCs changed upon in vitro passaging. The significant increase of cell and nuclear size of cAD-MSCs is obvious by visual inspection of representative DAPI- and phalloidin-(F-actin)-stained micrographs displayed at identical magnifications (a). The dimensionality reduction (b) by principal component analysis (PCA) of the extracted morphological features revealed that cAD-MSCs assume distinct morphological characteristics during passaging, which show only minor overlap between P2 and P9. The five canine samples were pooled. The axes represent the first two dimensions of the PCA, which together explained 54.1% of the total variance. Each dot in the graph represents a single cell

The evolution of the morphological appearance as a function of increasing numbers of passages was highlighted by principal component analysis (PCA) of defined nuclear and cellular morphological features (Supplementary Table S2). Over passages, cAD-MSCs mostly showed a right-shift on the first principal component axis (Dim1), which explained 36.7% of the variance in the experiment. Features such as cellular perimeter, cellular diameter, cellular area and nuclear area yielded the major contribution to Dim1 (Supplementary Figure S2a). The clusters of cAD-MSCs at different passages plotted in the first two dimensions showed an evident separation. In particular, cells at P9 had a small overlap with cells at earlier passages (Fig. 2b). This method was used later to compare the effects of immortalization on cAD-MSCs.

Protein expression of cAD-MSCs at late passages was in accordance with a senescence phenotype

The high-content analysis workflow included the immunostaining of two important proteins involved in the regulation of the cell cycle, antigen Ki67 (Ki67) and BMI1. Median intensities per cells where compared, resulting in an important increase in the intensities of both proteins from the freshly thawed passage P2 to the next highly proliferative passage P3 (Fig. 3b and d). However, we measured a significant reduction in the intensity signals for both proteins between P3 and P6. Between P6 and P9, only the BMI1 signal increased significantly. To assess the number of cells expressing the two proteins of interest, we also analysed the number of positive Ki67 and BMI1 cells by setting a threshold at the highest measured background signal (Supplementary Figure S2b and S2c). For both proteins, we observed the same trend as described for the median signal intensities, suggesting that loss of signal occurred along with loss of positive cells.

Fig. 3.

High-content analysis of the immunostaining for the detection of replicative senescence-associated proteins suggests the development of a senescent phenotype in cAD-MSCs upon in vitro passaging. Representative micrographs of Ki67 immunostaining at P2 and P9 (a) as well as quantification of median Ki67 intensity per cell (b) revealed an important decrease of Ki67 signal between P3 and P9. In contrast, micrographs of BMI1 immunostaining (c) suggest the maintenance of important BMI1 signal levels at P9. This visual impression was confirmed by signal quantification, which showed a fluctuation of the BMI1 signal over passages with a considerable decrease between P3 and P6 (d). GLB1 foci appear in micrographs as a vesicular accumulation of signal in the perinuclear cytoplasm (e). The number of cAD-MSCs containing at least one GLB1 focus increased progressively from P2 to P9 (f). AIU, arbitrary intensity unit. NS p > 0.05; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Scale bars = 50 µm

An extensively described characteristic for replicative cellular senescence is the increase in the SA-β-galactosidase enzyme activity over passages. In our experimental setup, the activity was measured indirectly by quantifying the number of cells expressing β1-galactosidase (GLB1) and the number of GLB1-signal foci per cell, as corroborated by immunostaining of this protein. Between P2 and P9, an increasing tendency toward high numbers of GLB1-positive cells was noted. Nevertheless, when comparing P9 with P2, the number of GLB1-expressing cells reached significantly higher values (Fig. 3f). Within the cells presenting GLB1 foci, a twofold increase in cells containing a “very high” (n > 20) number of foci per cell was observed at P9 (2.39%) compared to P2 (1.19%), and a moderate positive correlation between the percentage of GLB1-positive cells and the mean number of foci per cell was measured (R = 0.73, p = 0.00026) (Supplementary Figure S2d and S2e). Furthermore, Pearson’s correlation between each of the extracted features in the high-content analysis was performed and is reported in Supplementary Table S4. It can be visually inspected in a Shiny App specifically developed for the detailed navigation of this dataset (https://anastojiljkovic.shinyapps.io/Senescence_cAD-MSCs/).

An additional marker for replicative senescence is the accumulation of DNA double-strand breaks, which correlates with the accumulation of foci expressing the phosphorylated form of the histon H2AX protein (γ-H2AX). γ-H2AX mean intensities were corroborated by immunostaining and quantified upon normalization to the DAPI signal in cAD-MSCs at different passages. An accumulation of this protein was significant only between P3 and P6. However, the mean value difference was only minimal (Supplementary Table S4 and Supplementary Figure S2f and S2g).

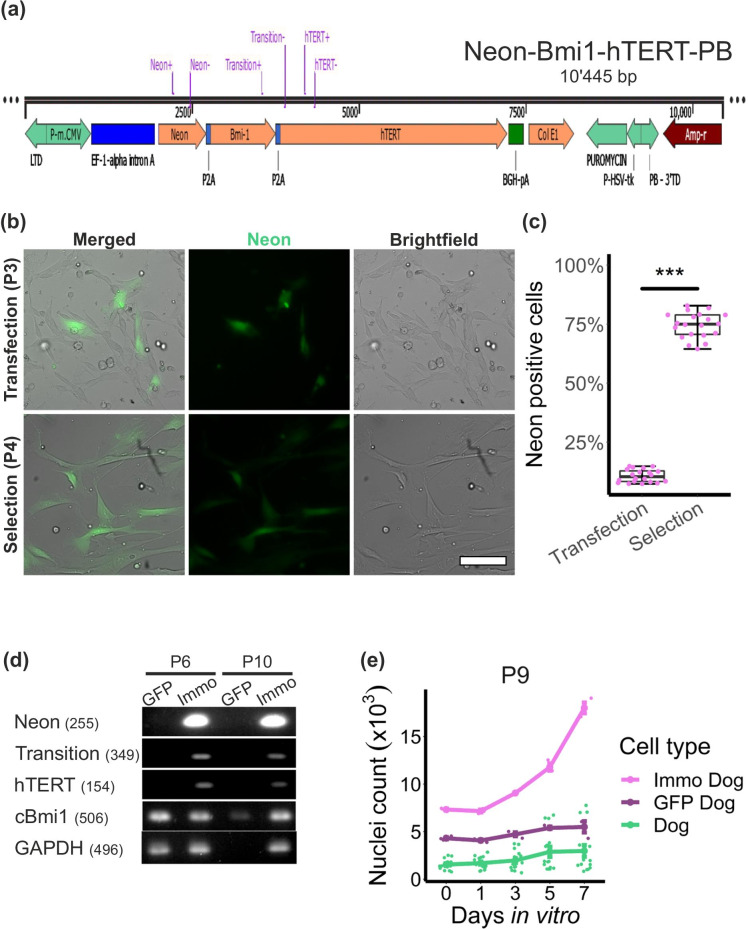

The hBMI1-hTERT PiggyBac™ transposon system provides an efficient way to transfect cAD-MSCs

To immortalize cAD-MSCs, we designed a PiggyBac™ (PB) transposon system containing the coding sequences for human BMI1 and human TERT under the same promotor (Immo-PB). The hBMI1 and hTERT coding sequences are separated by a P2A sequence, which allows the expression of both proteins to a similar amount in transfected cAD-MSCs (Fig. 4a). Additionally, to assess successful transfection, a mNeonGreen (Neon) protein was introduced upstream of the hBMI1 sequence and connected to it with a P2A sequence. The transfection efficacy of a cAD-MSCs-sample at P3 with the Immo plasmid co-transfected with a hyperactive PB transposase was quantified by automated segmentation (Fig. 4b). The number of Neon-expressing cells amounted to 10.7% (± 2.7%) (Fig. 4c). A further advantage of this plasmid is the presence of a puromycin-resistance coding sequence, which allows for the selection of the efficiently transfected cells. After puromycin selection, the number of positive cells in the sample reached 74.5% (± 5.4%) at P4 (Fig. 4c). To monitor the successful transcription of the introduced genes, we performed quantitative PCR using primers for Neon, hTERT and the transition region between hBMI1 and hTERT, as schematically represented in the plasmid map (Fig. 4a). mRNA samples of Immo-transfected cAD-MSCs were collected at P6 and P10 and compared to cAD-MSCs transfected with a control PB plasmid containing only the coding sequence for the green fluorescent protein (GFP). The PCR results demonstrated that the Immo-transfected cells expressed the three tested sequences at the mRNA level, even at P10. In contrast, the cells transfected with GFP-PB only lacked the transcription of these three sequences (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, we corroborated the transcription of the canine BMI1 by designing a primer that showed no binding to the human BMI1 sequence. As expected, all the mRNA samples contained the canine BMI1 mRNA. Interestingly, Immo-transfected cells allowed for the collection of enough material to perform good quality PCR for many genes even at P10, while the cells transfected with GFP-PB permitted the harvesting of only small amounts of mRNA at P10, which resulted in a very weak canine BMI1 signal and an irrelevant signal in the reference gene Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) sample. The harvesting problem was confirmed with the results of the proliferation assay. In particular, at P9, cAD-MSCs transfected with GFP-PB only (GFP Dog) showed no significant increase in cell numbers over 7 days in vitro, while the growth curve of cAD-MSCs transfected with the Immo plasmid showed exponential growth even at P9 (Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4.

The BMI1-hTERT- PiggyBac™ transposon system successfully transfected cAD-MSCs and allowed for the puromycin selection of mNeonGreen-expressing cells. A PiggyBac™ transposon system (PB) was designed to contain the coding sequence for mNeonGreen (Neon), human BMI1 and human TERT on the same promotor (Immo-PB) (a) and was used to transfect cAD-MSCs. The Immo-PB vector consents puromycin selection of successfully transfected cells. Transfection and selection efficiency were quantified by automated counting of Neon-expressing cells and were compared between P3 at 24 h after transfection and P4 after three rounds of puromycin selection (b and c). Qualitative PCR was performed using primers for coding sequences contained in the Immo-PB (the primers are highlighted in purple in the vector map (a)). The transcription of Neon, hTERT and the transition region BMI1-hTERT were corroborated. The transcription of canine BMI1 was assessed using primers specifically designed for the canine BMI1 gene sequence, and GAPDH was assessed as a reference gene (d). cAD-MSCs transfected with the Immo-PB (Immo Dog) as well as with the control GFP-PB only containing the coding sequence for green fluorescent protein (GFP) (GFP Dog) were collected for PCR at P6 and P10. The PCR revealed that cAD-MSCs maintained the expression of the genes contained in the Immo-PB vector up to passage 10. Canine BMI1 expression was detected until later passages under all conditions. The efficacy of the Immo-PB vector to immortalize primary cells was assessed by performing the proliferation assay previously described for cAD-MSCs (e). This experiment corroborated that cAD-MSCs show important proliferation only when transfected with the Immo-PB (Immo Dog). This was not the case for untreated cAD-MSCs (Dog) or GFP-PB transfected cAD-MSCs (GFP Dog) (mean ± s.e.m.). *** p < 0.001. Scale bar = 100 µm

cAD-MSCs transfected with the hBMI1-hTERT-PiggyBac™ transposon system develop a senescence phenotype, which partially recovers over passages

The high-content analysis workflow was run on Immo-transfected cAD-MSCs at P6 and P9 and compared to the results previously obtained from untreated cAD-MSCs (dog). Both nuclear and cellular areas were significantly higher in immortalized cAD-MSCs (Immo dog) than in dog cells, but in contrast to what we observed in dog cells, the immortalized cells showed a significant decrease in both parameters over passages (Fig. 5a). The violin plots highlighted a skewed distribution towards smaller nuclear and cellular parameter, which was more pronounced in Immo dog cells. This is in accordance with the observation that the immortalized cells presented an inhomogeneous population in the DAPI- and phalloidin-stained samples, in which widely scattered cells showed a moderate-sized nucleus, or more often small cells with small nuclei (Fig. 5b). The quantification of the Neon signal at P6 and P9 revealed that 100% of the cells expressed the fluorescence reporter gene. The PCA including the immortalized cells showed a high overlap between the immortalized cells and the P9 dog cells. The immortalized cells were even more shifted to the right on the first principal component axis, while by passaging, we observed a slight left shift instead of the right shift observed by passaging dog cells (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

cAD-MSCs transfected with the BMI1-hTERT-PiggyBac™ show a cellular phenotype development over passages in countertendency to the untreated cAD-MSCs. When performing the high-content analysis workflow on cAD-MSCs transfected with the BMI1-hTERT-PiggyBac™ (Immo-PB) vector, we observed a significant reduction in the nuclear and cellular area between P6 and P9 (Immo cells), which is opposed to the phenotype development of untreated cAD-MSCs (Dog cells) (a). By visual inspection of the Immo cells at P9, we observed two distinct cell populations characterized by an important difference in nuclear and cellular size (b). Furthermore, the quantification of cells expressing mNeonGreen (Neon) at P6 and P9 showed an enrichment of the positive cells by passaging, without the need of further puromycin selection, reaching 100% positivity. The principal component analysis including the data of Immo cells showed that the morphological features of Immo cells at P6 and P9 are overlapping with untreated cells (Dog) mainly at P9. A slight left-shift towards the earlier passages of Dog cells is observed when comparing Immo P9 to Immo P6. NS p > 0.05; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Scale bar = 50 µm

Even if the cell’s morphology was comparable to that of late-passage cAD-MSCs, the expression of Ki67 and BMI1 in immortalized cells revealed a very important increase from P6 to P9 in the median intensities per cell for both proteins (Fig. 6a and b). Furthermore, the expression of BMI1 in Immo-transfected cells at P6 was already threefold higher than in untreated dogs at P6, and it increased up to a factor of 10 in immortalized cells at P9. The high Ki67 and BMI1 intensities assessed with the high-content workflow were confirmed by visual inspection of the micrographs of Immo-transfected cAD-MSCs at P9 (Fig. 6d and e). With regard to the GLB1 signal, we only have an indicative quantification of GLB1-positive cells in Immo-transfected cAD-MSCs, which was above the dog range at P6, but showed a tendency to decrease at P9, falling into the range of untreated dog cells at P9 (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

cAD-MSCs transfected with the BMI1-hTERT-PiggyBac™ show a reduction in the replicative senescence-associated gene expression over passages and maintain a high differentiation potential. In contrast to untreated cAD-MSCs (Dog), immortalized cAD-MSCs (Immo) show a significant increase in Ki67 (a) and BMI1 (b) median intensities per cell from P6 to P9. The intensity values were significantly higher than the intensities measured in Dog cells at any passage. At P9, Immo cells also show a tendency to a decreased number of GLB1-expressing cells (c). Important levels of Ki67 (d) and BMI1 (e) signals were observed by visual inspection of representative immunostaining micrographs of Immo cells at P9. Notably, MSCs at later passages lost the potential to fully differentiate into various cells of mesoderm origin (tri-lineage differentiation), i.e., adipocytes. However, Immo cells at P11 showed an important accumulation of lipid droplets (stained with Oil Red O) when exposed to adipogenesis-inducing medium (f). Control cells were cultured in standard MSC growth medium (f). Mean intensity quantification of the Oil Red O staining (ORO) revealed that only MSCs at P3 (DogP3) and immortalized MSCs at P9 (ImmoP9) displayed an increase of the signal when cultured in adipogenesis induction media (ind) (e). MSCs at P9 (DogP9) and GFP-PB-only transfected cells at P9 (GFP_P9) had mean ORO intensities comparable to the background signal, which corresponded to 0.025 AIU. For GFP_P9, the quantification of the signal was possible exclusively in the control medium, as the exposure to induction media provoked a complete cell loss. Cell loss was important also for DogP9, and the visual inspection is confirmed by the very small interquartile range of the boxplot for these cells. AIU, arbitrary intensity unit. ns p > 0.05, *** p < 0.001. Scale bars = 50 µm

cAD-MSCs transfected with the hBMI1-hTERT-PiggyBac™ transposon system maintain their differentiation potential at late passages

A main drawback of replicative cellular senescence is the loss of the differentiation potential in AD-MSCs at late passages. To investigate the effect of immortalization on the ability of cAD-MSCs to undergo adipogenesis, osteogensis, and chondrogenesis, we have first demonstrated the mesenchymal origin of the cells isolated for this study (Supplementary Figure S3) and performed tri-lineage differentiation at P3 (Supplementary Figure S4). Then, we qualitatively (Fig. 6f) and quantitatively (Fig. 6g) assessed adipogenesis in Immo-transfected cells and compared it to cells transfected with GFP only. Immo-transfected cells at P11 showed a considerable accumulation of lipid droplets only when exposed to adipogenesis-inducing media (adipogenesis), as revealed with Oil Red O but not after exposure to standard growth medium (ctrl) (Fig. 6f). This visual impression was also confirmed at P9 with the quantification of the fluorescent Oil Red O signal (Fig. 6g). Notably, only immortalized cells (ImmoP9) showed increased Oil Red O signal after exposure to adipogenesis induction medium. In contrast, the cAD-MSCs sample used for immortalization showed increased signal only at P3 (DogP3), but not at P9 (DogP9). In addition, cells that were transfected with GFP only (GFP P9) never reached the cell density needed to start an adipogenesis experiment, and the rare cells exposed to the adipogenic medium were lost during the differentiation protocol. Osteogenesis and chondrogenesis were also performed and qualitatively assessed at passage P9 (Supplementary Figure S5). As for adipogenesis, DogP9 and GFP P9 did not reach an appropriate confluency due to proliferation arrest and failed to differentiate upon osteogenesis induction. However, in the osteogenesis experiment, Immo P9 failed to differentiate as well. Even though the cell yield was higher for Immo P9, we have chosen to seed all the samples at the same density, which was limited by Dog P9 and GFP P9, in favour of the best possible comparability. For osteogenesis, we have observed that the cell-to-cell contact is fundamental for a successful differentiation. In fact, we observed at P3 that in the osteogenesis induction condition, the cells show a very strong reorganisation and they build a three-dimensional colony-like structure. Interestingly, we observed calcium deposition in these structures only (Supplementary Figure S4). We hypothesised that the lack of confluency at P9 limits the successful osteogenesis in all the samples, thus precluding any conclusion to be drawn about the potency of immortalized cAD-MSCs. In contrast, chondrogenesis was successful for Immo P9 cells only. Under standard culture condition, these cells formed a monolayer on the membrane insert, but under chondrogenesis induction, they formed a moderate pellet structure, which displayed an important blue coloration when stained with Alcian blue. Dog P9 cells also formed a small pellet. However, this was mostly red in colour, even upon chondrogenesis induction. GFP P9 formed only a discontinued monolayer under control condition, and the cells were lost during differentiation. In conclusion, immortalized cAD-MSCs maintained a higher multi-potency at late passages when compared to different non-immortalized control cAD-MSCs.

Discussion

In this study, we present a high-content screening and analysis workflow relying on open-source image analysis pipelines, which was implemented to detect cellular senescence in eukaryotic cells. The workflow was first applied to investigate the appearance of replicative cellular senescence in cAD-MSCs, and later to assess the evolution of the senescence phenotype of the same cell type upon treatment with a newly designed immortalization protocol.

The development of this high-content analysis workflow was based on multicolour high-throughput imaging. Taking advantage of immunostaining, quantification of the expression of three different proteins was performed simultaneously. The use of a multi-well system allowed for the reduction in the variability between experiments, as it allowed for the analysis of cAD-MSCs extracted from different tissue donors and control cells during an identical experimental run. One experimental run generated data for the quantification of numerous nuclear and cellular features and simultaneously assessed the expression of the three proteins associated with in vitro proliferation arrest and senescence (Ki67, BMI1 and GLB1).

The canonical SA-β-gal chromogenic assay was replaced in our study by GLB1 immunostaining. The expression of this enzyme at the protein level was reported to be strongly associated with SA-β-gal activity [25], and its correlation has also been tested on cAD-MSCs in this study; therefore, we considered its immunostaining a reasonable alternative to assessing the senescence phenotype in cAD-MSCs. The use of fluorescence-conjugated antibodies and spot-quantification instead of the classic chromogenic assay [26] has the advantage of being less susceptible to pH fluctuations. Overall, we consider the quantification of GLB1 signal to be more suitable and reliable for high-throughput screening.

The proliferation capacity of cAD-MSCs was also quantified using high-content screening and analysis. The advantage of this system, compared to the widely accepted MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide) proliferation assay, is the direct quantification of the cell number instead of an indirect inference from measuring the enzymatic activity by quantification of the luminescence signal, which can be affected by different extrinsic and intrinsic factors [27]. This is even more important when assessing senescence, as senescence induces important metabolic changes in the cells. Therefore, we consider the proposed high-content analysis method to be a more specific tool to assess proliferation.

The high-content analysis workflow described above was used to study replicative cellular senescence of cAD-MSCs. Proliferation arrest due to replicative senescence detected by SA-β-gal kits has been suggested previously for cAD-MSCs [19, 20], but an actual quantification of the senescence phenotype was missing for the canine species so far. Our results confirmed the occurrence of a proliferation arrest in cAD-MSCs upon in vitro passaging. The arrest was reached at P9, independently from the origin of the cells. Therefore, our data suggest that differences in tissue donors seem to play a minor role in the development of the senescence phenotype when compared to the effects induced by in vitro passaging itself. However, the in-depth assessment of differences between the donors was not the main objective of this study. In general, the observed proliferation arrest at P9 is in line with previous work on human AD-MSCs [28] and canine AD-MSCs [19]. This observation was also confirmed by measuring a significant reduction of the proliferation marker Ki67 [29] at late passages.

With the same workflow, we were able to trace the morphological evolution of cAD-MSCs over passaging and corroborated the appearance of characteristic morphological modifications as being typical of senescent cells. The main parameters were an increase in nuclear and cellular size [18, 30]. We further demonstrated an important downregulation of BMI1 from P3 to P6. This protein is crucial in the maintenance of cell cycling and prevents senescence via the p16Ink4A-retinoblastoma (RB) pathway [31, 32]. However, we observed an increase in BMI1 positive cells between P6 and P9, but this needs to be interpreted with caution, taking in consideration that the cells reaching P9 are probably already enriched for expressing high levels of BMI1. Furthermore, we demonstrated an increased expression of GLB1 at late passages, which provides indirect evidence for the upregulation of the β-galactosidase activity, a typical feature of senescent cells [33].

Thus, we developed a workflow to simultaneously investigate three important characteristics of senescence [34] and demonstrated that cAD-MSCs at late passages show all three of these characteristics: lack of proliferation markers, activation of the cell cycle arrest machinery and increased activity of the SA-β-galactosidase. Even though we have performed the quantification of the nuclear γ-H2AX signal, we do not recommend its use in the senescence screening workflow described here, as it requires an additional imaging step at higher magnification. Furthermore, its sensitivity to detect senescence in the cAD-MSCs model seems to be of limited value only.

Performing this investigation on cAD-MSCs, we also observed an effect of freezing on the proliferation capacity of MSCs. When characterizing the freshly thawed cells at P2, we observed a significantly lower proliferation rate than that measured for the cells at the very next passage, P3. This observation was corroborated by both growth curve quantification and Ki67 fluorescence intensity. Furthermore, cAD-MSCs at P2 showed a reduced expression of BMI1 when compared to P3. However, the morphological features and the expression of GLB1 were only marginally affected by the freezing process. Thus, the present findings suggest a considerable impact of freezing on the proliferation capacity of MSCs, as previously described [35], but only a minor importance in regard to inducing a senescent phenotype. Although freezing is a standard procedure in stem cell research, our observations substantiate a detrimental effect of thawing on early proliferation rate. This observation and the results suggesting a rapid onset of proliferation arrest demonstrate that the exploitable time window for any therapeutic application of these precious cells is extremely narrow.

In this study, we also described the generation of a newly designed immortalization system, which may be useful in the future to generate patient-specific AD-MSC lines. Immortalization of MSCs by overexpression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) has previously been reported [12]. hTERT prevents telomere shortening caused by the end replication problem, which is an important mechanism of replicative senescence [36]. Interestingly, overexpressing hTERT and BMI1 simultaneously shows more efficient immortalization of hAD-MSCs than hTERT alone [17]. A combined hTERT-BMI1 immortalization approach by using a PiggyBac™ (PB) overexpression system has been previously described for bovine fibroblasts [37]. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, these two genes have always been introduced sequentially into the cells using distinct vectors. Sequential transfection has the important disadvantage of being tedious and time-consuming, as the selection of cells expressing both genes in sufficient amounts has to be warranted. Thus, this is the first report describing the use of a non-viral integrative vector to simultaneously overexpress the human BMI1 and the human TERT gene in MSCs, which might better support immortalization. In addition, this system allows for the possibility of footprint-free excision of the inserted transgene at a later point in time [38].

Using the proposed high-content analysis workflow, we demonstrated that cAD-MSCs transfected with this new immortalization PB transposon system showed high-proliferation capacity at P9 and displayed high levels of Ki67 and BMI1 when compared to untreated cells. The expression of these two proteins increased over passages, while GLB1 expression decreased. Nevertheless, the analysis of morphological features in immortalized cAD-MSCs showed enlarged nuclear and cellular size, comparable to those of senescent cAD-MSCs cells, but these parameters decreased over passages. We hypothesize that the morphological appearance of immortalized cells briefly after immortalization is related to stress-induced senescence due to puromycin selection. In fact, it has been shown that the expression of the puromycin gene can activate pathways in the cells that lead to reactive oxygen species production [39]. Therefore, we consider the morphological appearance of immortalized cells to be mainly stress-related, and not directly related to replicative senescence, this observation being in accordance with persistently high levels of Ki67 and BMI1. Furthermore, we observed that passaging reduces the senescence phenotype observed in immortalized cAD-MSCs, probably by gradual selection of small highly proliferative cells over enlarged senescent cells. To reduce the stress-induced senescence problem, other selection techniques might be more adequate, such as flow cytometry sorting of Neon-expressing cells. The need for a gentler selection method than the puromycin treatment was also highlighted by the inferior differentiation performances at late passages of the GFP-only transfected cells when compared to the untransfected cAD-MSCs controls. However, our results indicate that irrespective of their increased size, immortalized cAD-MSCs maintain differentiation potential up to late passages, as corroborated by adipogenesis quantification at P9 and further qualitative assessment at P11. This is very promising, as one of the main drawbacks of in vitro culture of MSCs is the loss of the differentiation potential over passaging, and in particular the considerable reduction in the adipogenic differentiation potential [40].

The suggested workflow can also be of great value to study the implication of telomere shortening in replicative senescence. The PiggyBac™ (PB) system containing the human TERT—which has a 70% identity at the protein level with the canine TERT—allows a direct comparison of the telomere biology in these two species. Even if dogs display a tenfold faster telomere shortening and a reduced life span when compared to humans, it has been demonstrated that dogs are a better model to study telomeres than rodents. In dogs as in humans, short telomeres correlate with increased mortality from cardiovascular diseases, respiratory failure, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal disorders [41]. Overall, understanding the overexpression of TERT in a canine in vitro model will contribute to improve our understanding of telomere shortening and aging in a valuable animal model for human diseases.

In conclusion, we report the development of a high-content analysis workflow, which allows for the simultaneous characterization of at least three aspects of replicative senescence in eukaryotic cells in a miniaturized system. We applied the workflow to quantify the appearance of a senescence phenotype in canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells over passages and showed that this phenotype can be partially recovered by taking advantage of a newly designed non-viral immortalization vector. Many properties of these cells are still evading our understanding due to the limited possibilities of in vitro expansion. However, the development of more reliable immortalization techniques and, thus, the facilitated generation of patient-derived MSCs will pave the way for a better understanding of these cells and how individual variation affects their potential in view of future applications in regenerative medicine.

Experimental procedures

Unless stated otherwise, all the cell culture solutions mentioned in this chapter were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Reinach, CH).

Cell isolation and culture conditions

Canine AD-MSCs (Canis lupus familiaris) were isolated as previously described for other species [42]. Briefly, five canine adipose tissue samples (Supplementary Table S1), discarded during abdominal surgeries due to indications unrelated to this study, were collected after owner informed consent in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (P/S) and kept at 4 °C (time prior to cell isolation ranged 0.5–24 h). The sample collection was randomized by including all the adipose tissue samples discarded during surgery over one month of collection. To blind the experimenter, an identification code was given to the sample without any reference to the origin of the sample. The fat tissue was minced with a disposable scalpel, and the tissue fragments were enzymatically digested in 0.1% collagenase type IA (Merck, Zug, CH) in DMEM at 37 °C for 1 h. After collagenase inactivation, the supernatant was filtered through a 70 µm cell strainer (Corning® by Merck) and centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min. The pellet was resuspended in DMEM, and the cells were seeded in tissue-culture-treated flasks (TPP, Techno Plastic Products AG, Trasadingen, CH) in high-glucose GlutaMAX™ DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, P/S and 10 ng/ml of human recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF) (PeproTech, London, UK). The cells were grown at 37 °C under humidified conditions with 5% CO2. After 24 h, adherent cells were extensively washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), and supplied with fresh growth medium. The medium was changed every two days and passaged once until approximately 90% confluency was reached. To this end, TrypLE™ Express Enzyme was added for 5 min. The cells were sub-cultured at 5000 cells/cm2. Cumulative population doublings were also calculated for each passage using the formula: n = 3.322 * (logE – logI) + X where “n” is the cumulative population doubling level for a defined passage, logE is the logarithm with base 10 of the number of cells harvested at the end of each culture period, logI is the logarithm with base 10 of the cell count used to inoculate the culture and X is the cumulative doubling level at the previous passage. Detailed results are presented in the Supplementary Table S4.

Cell characterization

Standard characterization was performed to confirm the cAD-MSC nature of the isolated cells. In particular, the expression of mesenchymal markers and the absence of hematopoietic markers was assessed by flow cytometry. For the surface phenotyping of cAD-MSCs, 1 Mio cells per condition were collected in ice-cold PBS supplemented with 1% FBS after enzymatic dissociation with TrypLE™ Express enzyme. The cells were then incubated with the corresponding fluorescence-conjugated primary antibodies (Supplementary Table S3) for 30 min on ice in the dark. The antibody-stained cells were centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Following two more washing steps in PBS, the supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in PBS with 1% FBS. The cells were stored on ice in the dark until use for flow cytometry quantification. The data acquisition was performed with a BDTM LSR II flow cytometry system (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and comprised 10′000 events per condition. The data generated were analyzed with the FlowJo™ software (FlowJo LCC, BD Life Sciences, Ashland, OR, USA). As no antibody double labelling was performed, fluorescence compensation was not needed. The gates were set on the unstained control cAD-MSCs. This experiment was repeated on five cAD-MSCs samples each at passage P2. As positive controls for the hematopoietic markers, blood samples from eight dogs of different breeds, sex and age were analysed. Excess blood left after the routine analysis was kindly provided by the Clinical Laboratory of the Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern. These samples were collected for clinical reasons unrelated to this study. The samples were centrifuged at 300 × g for 15 min at 4 °C before discarding the serum. The buffy coat containing the white blood cells was transferred to a tube containing 4 ml of PBS containing 1 µg/ml Hoechst 33,342 (Merck, Zug, CH) as a nuclear counterstain. The antibodies used to prove cAD-MSCs identity were added to white blood cells at the same dilution as for flow cytometry. Samples were incubated for 30 min on ice in the dark. After two washing steps as previously described for cAD-MSCs, the cells were transferred to a 8-well chamber µ-slide (ibidi, Martinsried, DE) and the white blood cells were allowed to sediment under the microscope for 15 min at RT prior to imaging, taking advantage of the high-content analysis system INCell Analyzer 2000 (GE, General Electric Healthcare Europe GmbH, Glattbrugg, CH). Imaging was preferred to flow cytometry due to the small amount of white cells obtained from the blood samples. A pooled sample of cAD-MSCs from five samples was processed in parallel for this imaging experiment and, therefore, the surface phenotyping results obtained in flow cytometry for the cAD-MSCs were confirmed optically.

Tri-lineage differentiation was performed as previously described for canine MSCs [43]. Briefly, for adipogenesis, the cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 10′000 cells/cm2 (TPP, Techno Plastic Products AG, Trasadingen, CH) in high-glucose GlutaMAX™ DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and P/S (basic medium). Each plate contained the five different canine samples at P3 in three replicates. After 24 h, the basic medium was supplemented with 5 µM rosiglitazone, 1 µM dexamethasone, 5 µg/mL insulin and 5% rabbit serum. The medium was changed every three days and the cells were fixed and stained after 14 days. Fixation was achieved using 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (PFA) for 20 min. Lipid vacuoles were stained with standard Oil Red O protocols and the nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. For osteogenesis, the cells were seeded as described for adipogenesis, with the only difference that cell density in this experiment corresponded to 1000 cells/cm2. After 24 h, the basic medium was supplemented with 0.1 µM dexamethasone, 50 µM L-ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate. The medium was changed every 3 days. After 42 days, the cells were fixed as previously described for adipogenesis, and calcium deposits were stained using standard Alizarin Red staining protocols. The cells stained with Oil Red O and Alizarin Red were imaged with an EVOS XL Core imaging system (ThermoFisher Scientific). Chondrogenesis was performed by seeding the cells into 6.5 mm Ø transwell polycarbonate membrane inserts with 8.0 μm pore size (Corning® Transwell®, Merck, Zug, CH). The cells were seeded at a density of 500′000 cells/well by pipetting 100 µL of cells resuspended in the chodrogenesis medium into the centre of the transwell insert and letting the cells sediment for 30 min. After this period, the well was slowly filled with medium to avoid excessive movement of the insert. For chondrogenesis, the basic medium was supplemented with 10 ng/mL TGF-β1, 50 µM L-ascorbic acid and 6.25 μg/mL insulin. The medium was carefully changed every three days and the cells were fixed after 14 days. After fixation with 4% PFA for 30 min, the pellet was incubated for 3 h in increasing sucrose concentration (10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose in PBS). The samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C in 30% sucrose before snap-freezing the insert membranes in tissue freezing medium (O.C.T.™ Compound, Tissue-Tek®) and carefully separated from the insert using a sharp needle. 5-micron-thick cryo-sections were obtained by cutting the samples perpendicular to the insert membrane. The sections were stained for the presence of glycosaminoglycans with a standard protocol for Alcian blue staining, and counterstained with nuclear fast red. The sections were imaged as tiles using a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 and stitched with the Zen Blue software (Carl Zeiss Vision Swiss AG, Feldbach, Switzerland). The same procedure for tri-lineage differentiation was performed also at P9 for cAD-MSCs (Dog P9), as well as for the GFP-only-transfected control cells (GFP P9) and immortalized cAD-MSCs (Immo P9). However, the initial seeding density was significantly reduced, due to the low cell yield of DogP9 and GFP P9 at late passages. The resulting seeding densities were 2 cells/cm2 for osteogenesis, 20 cells/cm2 for adipogensis and about 200′000 cells/well for chondrogenesis. Compared to the seeding conditions for the cells at P3, at P9 the seeding densities were 500 times lower for adipo- and osteogenesis and 2.5 times lower for chondrogenesis. Even if Immo P9 had a higher cell yield at P9, we seeded the same number of cells as for the other conditions for the sake of a better comparability. Furthermore, during an independent transfection experiment, adipogenesis was performed also at P11.

PiggyBac™ transposon system plasmid preparation

A plasmid containing the hTERT sequence (#1773, Addgene, Watertown, MA, USA) was modified to contain the coding sequence for the human BMI1 followed by a P2A sequence. The human BMI1 sequence (pUC57 vector, GenScript, Leiden, NL) was inserted upstream of the hTERT sequence by enzymatic digestion (XbaI and MluI, Promega AG, Dübendorf, CH) and subsequent ligation (Rapid DNA Ligation Kit, Roche, Merck, Zug, CH). Then, we took advantage of the In-Fusion® HD Cloning system (Takara Bio Europe, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, FR) to generate a PiggyBac™ transposon system (PB) containing NEON, hBMI1 and hTERT under the same promotor (Immo-PB). Briefly, we designed primers with complementary overhangs (Supplementary Table S3) and used them to generate a "NEON insert" by PCR amplification (high-fidelity DNA polymerase, CloneAmp™, Takara Bio Europe, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, FR) of the mNeonGreen sequence (Allele Biotechnology and Pharmaceuticals Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Similarly, we generated a "hBMI1-hTERT insert" by amplifying the hBMI1-hTERT-PB plasmid previously described. Using the In-Fusion® cloning system, the two inserts were introduced into a PB-backbone [44], which was linearized by removing the EGFP coding sequence by enzymatic digestion (NotI and BsrGI, New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and was purified with the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN AG, Hombrechtikon, CH). DH5α competent cells were transformed with the product of the cloning reaction and the positive colonies were screened by colony PCR with a primer designed to amplify a region located between the vector backbone and the NEON insert (Supplementary Table S3).

Growth curves

To quantify the proliferation capacity of the cAD-MSCs, the cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 5000 cells/cm2. For each canine sample, five plates were prepared, one for each imaging time point, including three replicate wells for each condition. At the tested time points (Day In Vitro (DIV) 0, 1, 3, 5, and 7), the cells were washed once with DPBS and stained with 1 µg/ml Hoechst 33,342 (Merck, Zug, CH) in a Live Cell Imaging Solution (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 20 min at 37 °C. After the nuclear staining, the medium was substituted with fresh medium, and 81 fields of view were imaged. Live cell imaging was performed at 37 °C under humidified conditions and CO2-supply, taking advantage of the high-content analysis system INCell Analyzer 2000 (GE, General Electric Healthcare Europe GmbH, Glattbrugg, CH) equipped with a Plan Fluor Nikon 20 × 0.45 NA objective and the 350_50x & 455_50 m (DAPI) filter set. The time point DIV0 was imaged at 4 h after the cell seeding. At this time point, the cells had enough time to adhere, but not to proliferate. The experimental setup included two types of HeLa cell controls, a genuinely immortal cell line derived from a human cervical cancer (confirmed as mycoplasma-free prior to use). HeLa cells are expected not to show signs of proliferation arrest over passages (negative control). The cells were grown in GlutaMAX™ DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and P/S and under the same culture conditions as cAD-MSCs. The experiments were performed in parallel to the cAD-MSCs, but HeLa cells were seeded at 2500 cells/cm2. As a positive control for senescence, at DIV1, half of the plated HeLa cells were incubated with standard culture medium containing 1 µM camptothecin (CPT) for 3 h. After this period, the medium was changed back to the standard medium. Effects of impaired growth were expected from DIV3 on, as the plant-derived cytostatic CPT has been reported to induce proliferation arrest and senescence phenotype also in immortal cells over a mechanism of topoisomerase I-mediated DNA damage [45].

The images were segmented using an Otsu two-class thresholding strategy with the CellProfiler™ software (version 3.8.1). For the detailed analysis pipeline, see Supplementary Table S2.

Prior to pooling the five dog samples, we verified the absence of significant differences between donors by using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by a Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test (p < 0.05). A logistic regression model was fitted to the data of each dog sample using the Growthcurver package for R, and the area under the experimental proliferation curve (eAUC) and the carrying capacity K were extrapolated and plotted over the four passages.

Immunostaining and high-content analysis

For the characterization of the senescence phenotype in cAD-MSCs by means of immunostaining, the cells were seeded in Greiner µClear® 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, AT) at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 (HeLa: 2500 cells/cm2). The cells were grown under standard culture conditions for 48 h prior to fixation and immunostaining (detailed protocol in Supplementary Table S3). For the quantification of the Ki67 and GLB1 signals, each plate contained four well replicates, while eight replicate wells were plated for the BMI1 signal.

Images were acquired with the high-content analysis system INCell Analyzer 2000 (GE, General Electric Healthcare Europe GmbH, Glattbrugg, CH) equipped with a Plan Fluor Nikon 20 × 0.45 NA objective (filter sets in Supplementary Table S3). For each well, 30 randomly distributed fields of view were imaged.

The images were segmented using the CellProfiler™. For the nuclear segmentation, a similar strategy was used as previously described for the quantification of the proliferation capacity. Furthermore, the cell contours were segmented by using the nucleus as a reference object, which was propagated in the micrographs of the Alexa Fluor™ 555 Phalloidin signal (pipeline in Supplementary Table S2). Nuclear and cellular areas were compared over passages considering the tissue donors as biological replicates. Stratified randomized sub-sampling of the data was used to address the problem of p-hacking in big data [46]. We observed that sub-sampling eliminated the differences between donors, while the significant differences between passages remained unchanged. For nuclear and cellular areas, only non-parametric tests were applied because the distribution of the data showed positive skewness.

To address the question of the morphological alteration of cAD-MSCs over passages, we performed principal component analysis (PCA). For this purpose, 10 nuclear and 10 cellular features (Supplementary Table S2) were extracted from the segmented objects and analysed using the PCA function of the R package FactoMineR and the factoextra R package. The one-by-one correlations between all the parameters analysed at a single-cell level are available in a web-based interactive dashboard created for this high-content analysis dataset (Shiny App: https://anastojiljkovic.shinyapps.io/Senescence_cAD-MSCs/) and summarized in the Supplementary Table S4.

For the quantification of the immunofluorescence signal, the nuclear segmentation was used as reference object to measure the median intensity of Ki67 and BMI1 after the subtraction of the background, measured as minimal intensity value of the Ki67 or BMI1 signals, respectively. The subtraction of the background was performed to minimize the plate-to-plate effect. In this case, using DAPI for normalization was considered as inappropriate due to the observed effects on nuclear morphology at different passages. For the count of GLB1-positive cells, GLB1 foci were segmented and assigned by 100% overlapping to objects resulting from cellular segmentation. To evaluate the possible accumulation of GLB1 foci over passages, the number of GLB1 foci was assigned to four categories: GLB1 foci ≤ 3 as “low,” GLB1 foci > 3 and ≤ 10 as “medium,” GLB1 foci > 10 and ≤ 20 as “high,” and GLB1 > 20 as “very high.” To validate the GLB1 antibody on the cellular model used in this study, we have plated cAD-MSCs from all the canine samples at P6, as previously described for the immunostaining of GLB1, and we have double-stained the cells with a commercially available detection kit for the activity of the senescence associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-GAL) enzyme (CellEvent™ Senescence Green Detection Kit, Invitrogen™, ThermoFisher). Spearman’s correlation was performed and the correlation coefficient rho is reported in the Supplementary Table S4. Overall, the correlation was present but weak at P6. However, the correlation was strong when the cells where treated with 1 µM camptothecin to induce senescence. These findings suggest a satisfactory specificity of the GLB1 immunostaining procedure in cAD-MSCs.

γ-H2AX quantification was performed with the high-content analysis system as previously described, but this nuclear staining required imaging at a higher magnification (Nikon 60x, 0.7 NA objective). For the quantification of the γ-H2AX signal, the nuclear segmentation was used as reference object to measure the mean nuclear intensities of both γ-H2AX and DAPI. Background subtraction was not performed for these images, as the signal to noise ratio at this magnification was better when compared to images acquired at 20x. For this specific analysis alone, normalization against DAPI was considered appropriate because DNA damage is proportional to DNA content.

Transfection of cAD-MSCs with the PiggyBac™ transposon system

cAD-MSCs at P2 were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 and grown under standard culture conditions for 24 h. Then, they were transfected with 0.5 µg DNA, which was composed of a 5:1 ratio of Immo-PB and a PiggyBac™ transposase[44]. The transfection was performed with the Lipofectamine Stem reagent following the manufacturer’s instructions. At 24 h after transfection, brightfield and fluorescent images were acquired to assess the number of NEON-expressing cells. For this purpose, live cell imaging was performed with the INCell Analyzer 2000 using the environmental control, as previously described. The images were automatically segmented using CellProfiler™ (pipeline in Supplementary Table S2). After imaging, the cells were split with standard protocols and transferred to 6-well plates to allow proliferation of the successfully transfected cells. The cells were monitored for confluency, and as soon as NEON-positive colonies appeared, the cells were treated with 10 µg/mL puromycin. The medium was changed daily to remove the cell debris and replaced with fresh medium containing puromycin. After 3 days of puromycin treatment, the medium was replaced with standard culture medium. The medium was replaced every second day, and the cells were monitored daily. The cells required 10 days to repopulate the well and reach confluency. At this moment, they were split at a 1:3 ratio and treated for 3 days with puromycin, as previously described. After the last puromycin treatment, the cells were imaged to assess the number of NEON-positive cells, which reached 100% at this point. The immortalized cells underwent the exact same experimental procedures as described for cAD-MSCs. In parallel to the Immo-PB transfection, cells transfected with a GFP-only control PB were generated and used as a control. So far, the immortalization was performed in two completely independent experiments. Both transfections resulted in cells stably expressing green (NEON) fluorescence, the immortalized cultures being monitored up to P11. The only-GFP-transfected controls showed a strong growth reduction already at P6 and were completely lost at P9. For the PiggyBac™-transfected cells, the senescence screening protocol was adapted to the fact that immortalized cells express NEON fluorescence. To this end, the number of replicates was reduced to three for the stained proteins Ki67, BMI1, and GLB1, and only single-staining was performed instead of double-staining.

Furthermore, we used standard PCR protocols to assess the expression of the inserted constructs at different passages (detailed protocol in Supplementary Table S3).

Adipogenesis quantification in cAD-MSCs

Interestingly, in a pilot study, we have observed that the standard Oil Red O staining is fluorescent in the red channel filter set of the high-content imaging system used for the senescence workflow (INCell Analyzer 2000, General Electric Healthcare Europe GmbH, Glattbrugg, CH). Therefore, the cells treated to induce adipogenesis were first stained with a standard Oil Red O staining protocol and imaged using a conventional widefield microscope in brightfield mode, as described previously. Subsequently, the fixed cells were counterstained with DAPI to allow nuclear segmentation and the mean intensities of the signal measured using the red filter sets were quantified using high-content analysis. This procedure was performed for all the dog samples at P3 to quantify the differentiation potential (Supplementary Figure S5), and for the dog sample used for immortalization at P3 (DogP3), and P9 (DogP9). In addition, transfected cells with the GFP-PB-only construct (GFP_P9) and the immortalization construct (ImmoP9) were measured at P9. The CellProfiler™ analysis pipeline used to quantify ORO signal is described in Supplementary Table S2. The mean intensity signal of the background was 0.025 AIU. For the pairwise comparison between the different cells, Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. As all the cells significantly differed between each other, an effect size was calculated using the “effsize” package in R. All the results are reported in Supplementary Table S4 and in Supplementary Figure S5.

Data analysis

Data processing and analysis were performed with KNIME 3.7.0 (Zürich, CH) and the R environment (version 3.6.1) using R Studio version 1.2.5033 (Boston, MA, USA). Statistical analysis was performed with R, and the figures were prepared with the R package ggplot2 and assembled with CorelDRAW Graphics Suite 2018 (Corel Corporation, Ottawa, CAN). The images were prepared using FIJI (ImageJ 1.52p). Beside the graphical representation, all the relevant results are presented as numerical values in Supplementary Table S4.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the kind support of the staff from the Small Animal Clinic, Vetsuisse Faculty Bern and the assistance of Helga Mogel in the lab. We also thank Philippe Plattet and Marianne Wyss for providing us with plasmids and helping with cloning. We thank Meike Mevissen, Angélique Ducray, Volker Enzmann and Simone Forterre for helpful discussions. This study was performed with the support of the interfaculty Microscopy Imaging Center (MIC) of the University of Bern.

Author contribution

AS designed the high-content analysis approach, wrote the manuscript and created the figures with the support of JB and MHS. AS designed and created the Shiny App for the navigation of the single-cell data. AS performed all the experiments with the help of VG for cell culture and molecular biology. FF and UR organized the collection of the tissue samples.

Funding

This work was funded by the Division of Veterinary Anatomy, University of Bern, Switzerland.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The image analysis pipelines are available in the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/StojiljkovicVetAna/HCA-to-investigate-senescence.

The Shiny App to navigate the single-cell data generated for this study is available at: https://anastojiljkovic.shinyapps.io/shiny_morpho/.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The tissue samples were collected after owner informed consent.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cossu G, Birchall M, Brown T, de Coppi P, Culme-Seymour E, Gibbon S, et al. Lancet Commission: Stem cells and regenerative medicine. Lancet. 2018;391:883–910. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31366-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry F, Murphy M. Mesenchymal stem cells in joint disease and repair. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9:584–594. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roura S, Gálvez-Montón C, Mirabel C, Vives J, Bayes-Genis A. Mesenchymal stem cells for cardiac repair: are the actors ready for the clinical scenario? Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8:238. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0695-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang M, Yuan Q, Xie L. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Immunomodulation: Properties and Clinical Application. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:3057624. doi: 10.1155/2018/3057624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chulpanova DS, Kitaeva KV, Tazetdinova LG, James V, Rizvanov AA, Solovyeva VV. Application of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Therapeutic Agent Delivery in Anti-tumor Treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:259. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–7. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown C, McKee C, Bakshi S, Walker K, Hakman E, Halassy S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: Cell therapy and regeneration potential. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019 doi: 10.1002/term.2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKee C, Chaudhry GR. Advances and challenges in stem cell culture. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2017;159:62–77. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turinetto V, Vitale E, Giachino C. Senescence in Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Functional Changes and Implications in Stem Cell-Based Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 doi: 10.3390/ijms17071164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campisi J, Di d'Adda FF. Cellular senescence: When bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeBrasseur NK, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Cellular Senescence and the Biology of Aging, Disease, and Frailty. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2015;83:11–18. doi: 10.1159/000382054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estrada JC, Torres Y, Benguría A, Dopazo A, Roche E, Carrera-Quintanar L, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell-replicative senescence and oxidative stress are closely linked to aneuploidy. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e691. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fridman AL, Tainsky MA. Critical pathways in cellular senescence and immortalization revealed by gene expression profiling. Oncogene. 2008;27:5975–5987. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kassem M, Abdallah BM, Yu Z, Ditzel N, Burns JS. The use of hTERT-immortalized cells in tissue engineering. Cytotechnology. 2004;45:39–46. doi: 10.1007/s10616-004-5124-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, Soda Y, Takahashi K, Bai Y, Mitsuru A, Igura K, et al. Successful immortalization of mesenchymal progenitor cells derived from human placenta and the differentiation abilities of immortalized cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;351:853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.10.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ben-Porath I, Weinberg RA. The signals and pathways activating cellular senescence. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:961–976. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tátrai P, Szepesi Á, Matula Z, Szigeti A, Buchan G, Mádi A, et al. Combined introduction of Bmi-1 and hTERT immortalizes human adipose tissue-derived stromal cells with low risk of transformation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;422:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez-Segura A, Nehme J, Demaria M. Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence. Trends Cell Biol. 2018;28:436–453. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krešić N, Šimić I, Lojkić I, Bedeković T. Canine Adipose Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transcriptome Composition Alterations: A Step towards Standardizing Therapeutic. Stem Cells International. 2017;2017:4176292. doi: 10.1155/2017/4176292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Z, Screven R, Boxer L, Myers MJ, Devireddy LR. Characterization of Canine Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells in Serum-Free Medium. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2018;24:399–411. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2017.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee J, Byeon JS, Lee KS, Gu N-Y, Lee GB, Kim H-R, et al. Chondrogenic potential and anti-senescence effect of hypoxia on canine adipose mesenchymal stem cells. Vet Res Commun. 2016;40:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11259-015-9647-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guercio A, Di Marco P, Casella S, Cannella V, Russotto L, Purpari G, et al. Production of canine mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue and their application in dogs with chronic osteoarthritis of the humeroradial joints. Cell Biol Int. 2012;36:189–194. doi: 10.1042/CBI20110304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linon E, Spreng D, Rytz U, Forterre S. Engraftment of autologous bone marrow cells into the injured cranial cruciate ligament in dogs. Vet J. 2014;202:448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Bakker E, van Ryssen B, de Schauwer C, Meyer E. Canine mesenchymal stem cells: state of the art, perspectives as therapy for dogs and as a model for man. Vet Q. 2013;33:225–233. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2013.873963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee BY, Han JA, Im JS, Morrone A, Johung K, Goodwin EC, et al. Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase is lysosomal beta-galactosidase. Aging Cell. 2006;5:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gary RK, Kindell SM. Quantitative assay of senescence-associated beta-galactosidase activity in mammalian cell extracts. Anal Biochem. 2005;343:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Tonder A, Joubert AM, Cromarty AD. Limitations of the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay when compared to three commonly used cell enumeration assays. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:47. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1000-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Legzdina D, Romanauska A, Nikulshin S, Kozlovska T, Berzins U. Characterization of Senescence of Culture-expanded Human Adipose-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int J Stem Cells. 2016;9:124–136. doi: 10.15283/ijsc.2016.9.1.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sobecki M, Mrouj K, Camasses A, Parisis N, Nicolas E, Llères D, et al. The cell proliferation antigen Ki-67 organises heterochromatin. Elife. 2016;5:e13722. doi: 10.7554/eLife.13722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner W, Horn P, Castoldi M, Diehlmann A, Bork S, Saffrich R, et al. Replicative senescence of mesenchymal stem cells: a continuous and organized process. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimono Y, Mukohyama J, Nakamura S-I, Minami H. MicroRNA Regulation of Human Breast Cancer Stem Cells. J Clin Med. 2015 doi: 10.3390/jcm5010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neault M, Couteau F, Bonneau É, de Guire V, Mallette FA. Molecular Regulation of Cellular Senescence by MicroRNAs: Implications in Cancer and Age-Related Diseases. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2017;334:27–98. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Itahana K, Campisi J, Dimri GP. Methods to detect biomarkers of cellular senescence: the senescence-associated beta-galactosidase assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;371:21–31. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-361-5_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burton DGA, Krizhanovsky V. Physiological and pathological consequences of cellular senescence. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:4373–4386. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1691-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oja S, Kaartinen T, Ahti M, Korhonen M, Laitinen A, Nystedt J. The Utilization of Freezing Steps in Mesenchymal Stromal Cell (MSC) Manufacturing: Potential Impact on Quality and Cell Functionality Attributes. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1627. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shay JW, Wright WE. Senescence and immortalization: role of telomeres and telomerase. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:867–874. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi W, Kim E, Yum S-Y, Lee C, Lee J, Moon J, et al. Efficient PRNP deletion in bovine genome using gene-editing technologies in bovine cells. Prion. 2015;9:278–291. doi: 10.1080/19336896.2015.1071459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang G, Yang L, Grishin D, Rios X, Ye LY, Hu Y, et al. Efficient, footprint-free human iPSC genome editing by consolidation of Cas9/CRISPR and piggyBac technologies. Nat Protoc. 2017;12:88–103. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moran DM, Shen H, Maki CG. Puromycin-based vectors promote a ROS-dependent recruitment of PML to nuclear inclusions enriched with HSP70 and Proteasomes. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng H, Qiu L, Ma J, Zhang H, Cheng M, Li W, et al. Replicative senescence of human bone marrow and umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells and their differentiation to adipocytes and osteoblasts. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:5161–5168. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0665-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fick LJ, Fick GH, Li Z, Cao E, Bao B, Heffelfinger D, et al. Telomere length correlates with life span of dog breeds. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1530–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bunnell BA, Flaat M, Gagliardi C, Patel B, Ripoll C. Adipose-derived stem cells: isolation, expansion and differentiation. Methods. 2008;45:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neupane M, Chang C-C, Kiupel M, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V. Isolation and characterization of canine adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1007–1015. doi: 10.1089/tea.2007.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matasci M, Baldi L, Hacker DL, Wurm FM. The PiggyBac transposon enhances the frequency of CHO stable cell line generation and yields recombinant lines with superior productivity and stability. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:2141–2150. doi: 10.1002/bit.23167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]