Abstract

We examined the interactions between educational attainment and genetic susceptibility on dementia risk among adults over 60 years old. A total of 174,161 participants were free of dementia at baseline. The APOE ε4–related genetic risk was evaluated by the number of APOE ε4 alleles. The overall genetic susceptibility of dementia was evaluated by polygenetic risk score (PRS). Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the association between educational attainment and incident dementia. During a median of 8.9 years of follow-up, a total of 1482 incident cases of dementia were documented. After adjustment for covariates, we found that low education attainment was significantly associated with higher dementia risk in the APOE ε4 carriers, and such relation appeared to be stronger with the increasing number of ε4 alleles. In contrast, educational attainment was not associated with dementia risk in non-APOE ε4 carriers (P for multiplicative interaction = 0.006). In addition, we observed that the dementia risk associated with a combination of low educational attainment and high APOE ε4–related genetic risk was more than the addition of the risk associated with each of these factors (P for additive interaction < 0.001). We found similar significant interactions between educational attainment and PRS on both the multiplicative and additive scales on the dementia risk, mainly driven by the APOE genotype. These data indicate that higher educational attainment in early life may attenuate the risk for dementia, particularly among people with high genetic predisposition.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-022-00545-z.

Keywords: Education, Genetic, APOE, Dementia

Introduction

Dementia is a medical diagnosis based on accumulated loss of cognitive abilities and limited cognitive capacity which negatively impacts the ability to live independently [1]. Both genetic and environmental factors have been implicated in the development of dementia [2]. The ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene is the strongest genetic risk factor predisposing to dementia [3, 4]. Compared with non-APOE ε4 carriers, individuals with one ε4 allele have a 2- to threefold higher dementia risk, whereas those with two ε4 alleles have a 7 to 14-fold higher dementia risk [5, 6]. On the other hand, a variety of modifiable risk factors for dementia have been identified at different stages of the lifespan, such as less education in early life, hypertension, obesity, hearing loss in midlife, and unfavorable lifestyles (smoking, physical inactivity) in late-life [7, 8]. Notably, it is still unclear whether improving such modifiable factors could attenuate the increased genetic risk for dementia. The majority of previous studies focusing on the interactions of midlife and late-life modifiable factors with genetic variations generated inconsistent results [9–13]. A recent study combined several well-established modifiable factors in midlife and late-life to create a composite modifiable-risk-factor score, whereas such score was associated with dementia risk only in non-APOE ε4 carriers, but not in APOE ε4 carriers [9], suggesting dementia risk in APOE ε4 carriers might be less affected by modifiable risk factors in midlife and late-life.

On the contrary, emerging evidence from cross-sectional analyses suggests that early-life educational attainment may modify the association between the APOE genotype and dementia risk, with a stronger inverse association between educational attainment and dementia risk in APOE ε4 carriers [14, 15]. However, evidence from the prospective settings is still lacking. Moreover, because participants with two ε4 alleles have a much higher dementia risk than those with one ε4 allele [5, 6], thus the association between educational attainment and dementia risk may differ according to the number of APOE ε4 alleles. However, previous studies failed to assess the relation of education with dementia risk according to the number of ε4 alleles.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the interactions between early-life educational attainment and genetic risk profiles (both the number of APOE ε4 alleles and overall genetic susceptibility) on the dementia risk among an older population of Europeans. The interactions were assessed on both the multiplicative and additive scales.

Methods

Study population

The UK Biobank Study is a population-based cohort study; the study design and methods have been described in detail previously [16]. In brief, more than 0.5 million participants aged 37 to 73 years were recruited in the baseline survey at 22 assessment centers throughout England, Wales, and Scotland from 2006 to 2010. In this study, because the majority of incident dementia cases occur in older adults, our analyses were restricted to participants aged at least 60 years old at baseline (N = 217,493) [10]. We further excluded participants who were classified as non-White European, dementia at baseline, and have incomplete data on the APOE e4 genotype information and education (N = 21,201). We additionally excluded participants with incomplete data on the main covariates (hearing problem, frequency of depression, social isolation score, and body mass index, physical activity, and smoking, N = 22,131). A total of 174,161 participants were included in the final analysis.

Educational attainment

Information on education was collected through the baseline touch-screen questionnaire. Participants were asked, “Which of the following qualifications do you have? (You can select more than one.)” Eight options were provided: (1) College or University degree; (2) advanced levels (A levels) or equivalent; (3) ordinary levels (O levels) or equivalent; (4) Certificate of Secondary Education (CSE) or equivalent; (5) National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) or Higher National Diploma (HND) or Higher National Certificate (HNC) or equivalent; (6) other professional qualifications (e.g., nursing, teaching); (7) none of the above; (8) prefer not to answer. According to the International Standard Classification of Education, we categorized educational attainment into three categories: high (college or university degree), intermediate (A/AS levels or equivalent, other professional qualification, and National Vocational Qualification or equivalent), and low (O levels/GCSEs or equivalent and none of the aforementioned).

The number of APOE ε4 allele and polygenetic risk score for dementia

The APOE ε4 genotype was determined by two APOE single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs): rs7412 and rs429358. The number of APOE ε4 allele was coded as 0 (ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, ε3/ε3), 1 (ε3/ε4), and 2 (ε4/ε4) respectively [20]. Participants with ε2/ε4 genotype were not included in the main analysis [20, 21], as such genotype have a combination of potentially protective and risk alleles (we performed a sensitivity analysis using the population including the APOE ε2/ε4 genotype). The polygenetic risk score for dementia, PRS (includes the APOE ε4 genotype), was calculated by 26 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [3], which passed quality control, based on a previous meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies (Supplementary Table 1). A weighted method was used to calculate the PRS. Each SNP was recoded as 0, 1, or 2 according to the number of risk alleles, and each SNP was multiplied a weighted risk estimate (β coefficient) on Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive disorder obtained from the previous genome-wide association study [3]. The genetic risk score was calculated by using the equation: PRS = (β1 × SNP1 + β2 × SNP2 + … + β26 × SNP26) × (26/sum of the β coefficients), where SNPi is the risk allele number of each SNP [22]. The PRS ranges from 10.0 to 42.5; a higher score indicates a higher genetic predisposition to dementia. This PRS was then categorized into low (the lowest tertile), intermediate (the middle tertile), and high (the highest tertile) risk. SNP genotyping, imputation, and quality control of the genetic data were performed by the UK Biobank team. The detailed information is available elsewhere [23].

Assessment of outcomes

A UK Biobank outcome adjudication team reviewed the possible dementia cases and determined whether a person had dementia, as well as the date of diagnosis, using data from multiple sources. In brief, information on the diagnosis of dementia was collected through medical history and linkage to data on hospital admissions, questionnaires, and the death register data. Follow-up time was counted from the date of assessment center visit until the date of diagnosis of dementia (until February 7, 2018) or the date of loss to follow-up or the date of death, whichever came first. To verify the accuracy of codes in UK Biobank for identifying participants with dementia, a subset of 17,198 UK Biobank participants has been studied for a validation study, and a high positive predictive value was observed (82.5% for all-cause dementia) [24]. Detailed information on the ascertainment of dementia has have been described previously (https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/showcase/showcase/docs/alg_outcome_dementia.pdf).

Statistical analysis

Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the association between educational attainment and incident dementia with years of follow-up as the time metric, reporting hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The proportional hazards assumption was tested by the Kaplan–Meier method. Several potential confounders were adjusted in the models, including age, sex, Townsend deprivation index, moderating drinking, current smoking, healthy diet score, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, depression, social isolation, hearing problem, regular physical activity, high cholesterol, traumatic brain injury, and cardiovascular diseases (coronary heart disease and stroke). The details of these confounders were described in the Supplementary methods. We also adjusted for the first 10 genetic principal components, genotyping array (106 batches), and relatedness (genetic kinship) when the genetic data were included in the analysis. Because the missing rates for all covariates were low (all covariates missing < 1%) in the current study, missing data were coded as a missing indicator category for categorical variables and with mean values for continuous variables. We tested the multiplicative interaction by adding the interaction terms between levels of educational attainment and genetic factors [the number of APOE e4 allele (0, 1, and 2) and PRS (low, middle, and high)] into the multivariable-adjusted models. Because the estimate of joint effect decomposition is based on the hypothesized linear associations between exposures and outcomes [25–27], to assess additive interaction between educational attainment and genetic risk, we considered low educational attainment (≦ 10 years of education, yes or no) and high genetic risk (for APOE ε4–related genetic risk: any ε4 allele (≧1) vs. zero ε4 allele; for PRS: high PRS vs. low and intermediate PRS) as two dichotomous variables. The relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) was assessed as an index of additive interaction [25, 28]. We also examined the decomposition of the joint effect: the proportion attributable to low educational attainment alone, to high genetic risk, and to the interaction [27]. On the hazard ratio scale, we decomposed the joint excess relative risk for both exposures (HR11 − 1) into the excess relative risk for low educational attainment (HR01 − 1), high genetic risk (HR10 − 1), and RERI. Specifically, we have HR11 − 1 = (HR01 − 1) + (HR10 − 1) + RERI. We then likewise calculated the proportion of the joint effect due to low educational attainment alone: (HR01 − 1)/(HR11 − 1); due to high genetic risk alone: (HR10 − 1)/(HR11 − 1); and due to their additive interaction, RERI/(HR11 − 1).

The study was approved by the NHS National Research Ethics Service. The present analysis was approved by the Tulane University (New Orleans, LA) Institutional Review Board. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and SPSS 22.0. All statistical tests were two-sided, and we considered P < 0.05 to be statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of participants according to the levels of educational attainment

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the study population by the levels of educational attainment. Participants with higher educational attainment were more likely to be younger and men, and had a higher socioeconomic level (a lower Townsend deprivation index). In addition, participants with higher educational attainment were more likely to have a healthy diet and moderate drinking habits; less likely to be current smokers or to have depressive symptoms or to have social isolation symptoms; and lower prevalence of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, hearing problems, high cholesterol, and cardiovascular diseases. The comparison of descriptive data for those who developed dementia and those who did not develop dementia is shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants by levels of educational attainment

| Low | Intermediate | High | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 72,659 (41.7) | 54,392 (31.2) | 47,110 (27.0) |

| Age, years (SD) | 64.4 (2.9) | 64.0 (2.8) | 63.8 (2.8) |

| Male (%) | 42.0 | 51.8 | 53.3 |

| Townsend deprivation index | − 1.3 (3.0) | − 2.0 (2.7) | − 2.0 (2.7) |

| Modifiable risk factors in middle or late life | |||

| Healthy diet score | 2.2 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.1) |

| Moderate drinking (%) | 44.4 | 48.8 | 51.8 |

| Current smoking (%) | 9.7 | 7.7 | 5.7 |

| Regular physical activity (%) | 63.6 | 64.7 | 63.2 |

| Obesity (%) | 27.4 | 24.9 | 18.3 |

| Hypertension (%) | 72.7 | 69.8 | 64.2 |

| Diabetes (%) | 7.3 | 6.5 | 4.9 |

| Depression (%) | 18.9 | 16.6 | 16.2 |

| Social isolation (%) | 10.1 | 7.5 | 7.2 |

| Hearing problem (%) | 32.1 | 32.4 | 31.7 |

| Traumatic brain injury (%) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| High cholesterol (%) | 31.7 | 28.9 | 24.3 |

| Cardiovascular diseases (%) | 11.3 | 9.6 | 6.8 |

| Number of the APOE ε4 alleles | |||

| Zero (%) | 73.5 | 73.7 | 73.8 |

| One (%) | 24.2 | 23.8 | 23.9 |

| Two (%) | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| PRS | |||

| Low (%) | 33.2 | 33.5 | 33.3 |

| Middle (%) | 33.3 | 33.3 | 33.5 |

| High (%) | 33.6 | 33.1 | 33.2 |

Data are mean (SD), or (%)

Association between educational attainment and incident dementia risk

During a median of 8.9 years of follow-up, we documented 1482 incident all-cause dementia cases. We found that lower educational attainment was significantly associated with higher dementia risk. After adjustment for age, sex, Townsend deprivation index, moderating drinking, current smoking, healthy diet score, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, depression, social isolation, hearing problem, regular physical activity, high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease, traumatic brain injury, compared with participants with a high education level, the adjusted HRs for all-cause dementia were 1.20 (95% CI, 1.03–1.39) for participants with an intermediate educational attainment, and 1.36 (95% CI, 1.18–1.56) for participants with a low educational attainment. These results remained unchanged after further and genetic risk profiles (the number of the APOE ε4 alleles or overall genetic susceptibility) (Table 2).

Table 2.

The association between levels of educational attainment and dementia risk

| Levels of educational attainment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Intermediate | Low | P-trend | |

| Cases (n, %) | 294 (0.6) | 431 (0.8) | 757 (1.0) | |

| Age and sex adjusted | 1 (reference) | 1.23 (1.06–1.43) | 1.54 (1.34–1.76) | < 0.001 |

| Multivariable adjusteda | 1 (reference) | 1.20 (1.03–1.39) | 1.36 (1.18–1.56) | < 0.001 |

| Multivariable adjusteda + number of APOE e4 allelesb | 1 (reference) | 1.20 (1.03–1.39) | 1.35 (1.18–1.56) | < 0.001 |

| Multivariable adjusteda + PRSb | 1 (reference) | 1.20 (1.03–1.39) | 1.35 (1.17–1.55) | < 0.001 |

aAdjusted for age, sex, Townsend deprivation index, moderating drinking, current smoking, healthy diet score, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, depression, social isolation, hearing problem, regular physical activity, high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease, and traumatic brain injury

bFurther adjusted for the first 10 genetic principal components, relatedness, and genotyping array

Association between the genetic risk profiles and incident dementia risk

Both the increasing number of APOE ε4 alleles and higher level of overall genetic susceptibility assessed by PRS were significantly associated with higher risks of dementia (Supplementary Table 3). Compared with participants without APOE ε4 allele, the HR was 2.74 (2.46–3.06) for participants with one ε4 allele; 8.66 (7.36–10.20) for participants with two ε4 alleles. Compared with participants with low PRS (the lower tertile of the PRS), the HR was 1.12 (0.95–1.31) for participants with intermediate PRS (the middle tertile of the PRS); 3.03 (2.65–3.46) for participants with high PRS (the upper tertile of the PRS). These results did not appreciably change after further adjustment educational attainment.

Interactions between the genetic risk profiles and educational attainment in relation to dementia risk

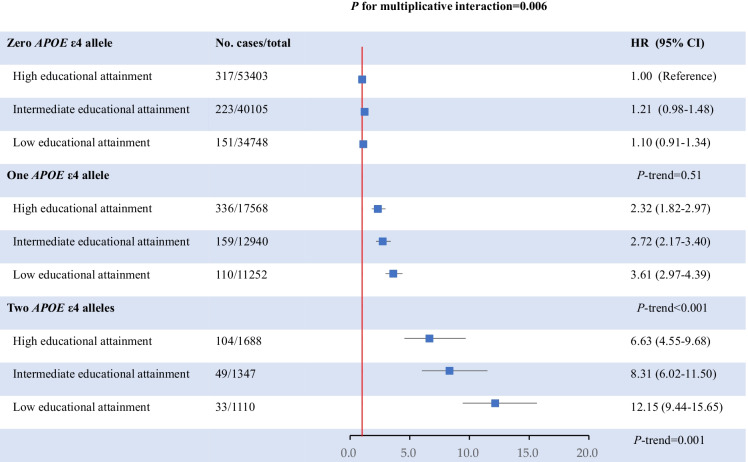

We first tested the interaction on the multiplicative scale. The number of APOE ε4 alleles significantly modified the association between levels of educational attainment and dementia risk (P for multiplicative interaction = 0.006). In participants without APOE ε4 allele, educational attainment was not associated with dementia risk (P-trend = 0.51). However, in participants with one APOE ε4 allele, lower educational attainment was significantly associated with higher dementia risk (P-trend < 0.001), as compared with participants with zero APOE ε4 allele and high educational attainment, the adjusted HRs were 2.32 (1.82–2.97), 2.72 (4.57–8.20), and 3.63 (2.97–4.39) in the high, intermediate, and low educational attainment category, respectively. The associations appeared to be further strengthened in participants with two APOE e4 alleles, the corresponding adjusted HRs were 6.63 (4.55–9.68), 8.32 (6.02–11.50), and 12.15 (9.44–15.65), respectively (P-trend = 0.001). Figure 1 shows the joint association between the number APOE ε4 alleles and educational attainment in relation to dementia risk.

Fig. 1.

Joint association between the number of APOE ε4 alleles and educational attainment in relation to dementia risk. Results were adjusted for age, sex, Townsend deprivation index, moderating drinking, current smoking, healthy diet score, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, depression, social isolation, hearing problem, regular physical activity, high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease and traumatic brain injury, the first 10 genetic principal components, relatedness, and genotyping array

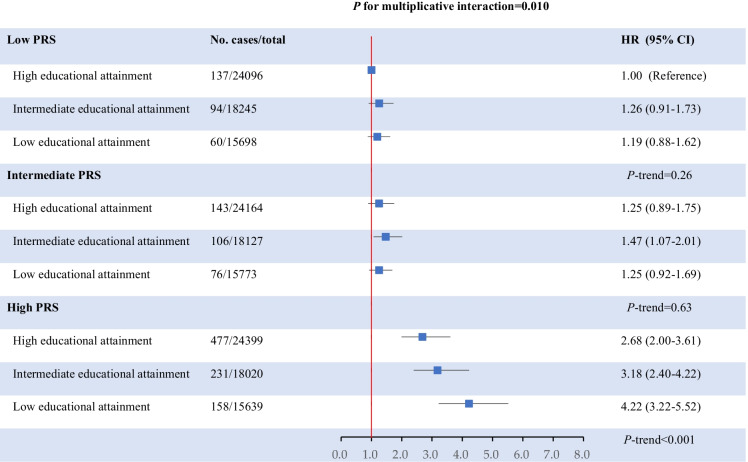

The overall genetic susceptibility assessed by PRS also significantly modified the association between levels of education and dementia risk (P for multiplicative interaction = 0.010). Low educational attainment was significantly associated with a higher dementia risk only in participants with the high PRS (the upper tertile of the PRS) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Joint association between PRS and educational attainment in relation to dementia risk. Results were adjusted for age, sex, Townsend deprivation index, moderating drinking, current smoking, healthy diet score, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, depression, social isolation, hearing problem, regular physical activity, high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease and traumatic brain injury, the first 10 genetic principal components, relatedness, and genotyping array

We then analyzed the interaction on the additive scale. We found that the dementia risk associated with a combination of low educational attainment (yes or no) and high APOE ε4–related genetic risk (at least one ε4 allele) was more than the addition of the risk associated with each of these factors (P for additive interaction < 0.001). The multivariable-adjusted HR of dementia was 3.87 (3.73–4.02) for the joint effect, with a relative excess risk due to interaction of 1.19 (0.71–1.67). The attributable proportions to the additive interaction were 41.5% (95% CI, 27.6–55.3) (Table 3). Similar significant additive interactions between high PRS (the upper tertile of the PRS) and low educational attainment in relation to dementia risk were observed (Table 3). Interestingly, both the multiplicative interaction and the additive interaction turned out to be non-significant after removing the APOE genotype from the PRS (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 4).

Table 3.

Attributing effects to additive interaction between low educational attainment and high genetic risk on dementia risk

| APOE ε4–related genetic risk | Overall genetic risk (PRS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main effects | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Main effects | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

| High APOE ε4–related genetic risk | 2.69 (2.33–3.12) | High overall genetic susceptibility | 2.37 (2.05–2.75) |

| Low educational attainment | 0.99 (0.85–1.16) | Low educational attainment | 0.98 (0.83–1.15) |

| Joint effect | 3.87 (3.73–4.02) | Joint effect | 3.34 (3.20–3.49) |

| Relative excess risk due to interaction a | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Relative excess risk due to interaction a | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

| Relative excess risk due to interaction | 1.19 (0.71–1.67) | Relative excess risk due to interaction | 1.00 (0.59–1.40) |

| P-value | < 0.001 | P-value | < 0.001 |

| Attributable proportion | % (95% CI) | Attributable proportion, % | % (95% CI) |

| High APOE ε4–related genetic risk | 59.0 (46.4–71.5) | High overall genetic susceptibility | 58.7 (45.8–71.6) |

| Low educational attainment | − 0.004 (− 0.05 to 0.05) | Low educational attainment | − 0.01 (− 0.07 to 0.05) |

| Additive interaction | 41.5 (27.6–55.3) | Additive interaction | 42.6 (27.6–57.5) |

Results were adjusted for age, sex, Townsend deprivation index, moderating drinking, current smoking, healthy diet score, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, depression, social isolation, hearing problem, regular physical activity, high cholesterol, cardiovascular disease and traumatic brain injury, the first 10 genetic principal components, relatedness, and genotyping array

aOn the hazard ratio scale, we decomposed the joint excess relative risk (HR11) for both exposures into the excess relative risk for low educational attainment (HR01), high genetic risk (HR10), and relative excess risk due (RERI) to their interaction. Specifically, we have HR11 − 1 = (HR01 − 1) + (HR10 − 1) + RERI

In sensitivity analyses, similar significantly multiplicative interaction and additive interaction were observed after further excluding participants with limited follow-up years (≦2 years) (Supplementary Figs. 2–3 and Supplementary Table 5). Further including participants with the APOE ε2/ε4 genotype did not appreciably change the results (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 6). Further including participants with the missing covariates (missing covariates were imputed with the multiple imputations) also did not appreciably change the results (Supplementary Figs. 5–6 and Supplementary Table 7).

Discussion

In this study, we found significant interactions between early-life educational attainment and the overall genetic susceptibility in relation to dementia risk on both the multiplicative and additive scales, whereas such interactions were mainly driven by the APOE genotype. We found that higher educational attainment was related to a lower dementia risk only among those with high-risk genetic profiles.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the multiplicative interaction between educational attainment and genetic risk profile on the dementia risk in a prospective cohort. Our findings are in line with previous evidence showing the high genetic risk for dementia might be mitigated by a high educational attainment in early life [14, 15]. A previous cross-sectional study reported that lower educational attainment was significantly associated with higher dementia risk in APOE ε4 carriers but not in non-APOE ε4 carriers [15]. An imaging study reported that higher educational attainment was significantly related to better cognitive function (as reflected by frontotemporal metabolism) only in APOE ε4 carriers but not in non-APOE e4 carriers, and such associations were independent of amyloid load [14]. However, it is notable that all these prior studies have failed to assess the number of ε4 alleles. Because participants with two ε4 alleles have a much higher risk for dementia than participants with one allele [5, 6, 29]. It is unclear whether a high educational attainment can still attenuate the extremely high genetic risk in participants with two APOE ε4 alleles. Intriguingly, our findings showed for the first time that the association of education with dementia risk appeared to be strengthened with the increasing number of the APOE ε4 alleles and indicated that people with a greater APOE ε4–related genetic predisposition might be more susceptible to the favorable effect of higher education.

Moreover, we observed that the dementia risk associated with a combination of low educational attainment and high APOE ε4–related genetic risk was more than the addition of the risk associated with each of these factors, indicating a significant interaction on an additive scale. Specifically, if both low educational attainment and high APOE ε4–related genetic risk were present, this would result in an additional 41.5% of cases of dementia. Notably, because the additive interactions could discern whether the effect of a risk factor on a certain disease would be different in different subgroups, thus they are more relevant to public health as compared with multiplicative interaction [30, 31]. These findings indicate that the public health consequence of low educational attainment would be larger in participants with a high genetic risk for dementia.

The precise mechanisms underlying the observed interactions remain unclear. The APOE ε4 allele increases dementia risk through its effects on brain pathology (increased amyloid positivity) [32, 33]. Of note, previous evidence has shown that APOE ε4–related brain changes occurred as early as during childhood [34]. Because such APOE ε4–related brain changes are irreversible and accumulate with age [35, 36], thus it is not surprising that the midlife or late-life modifiable factors were not related to dementia risk among the APOE ε4 carriers in some previous studies [9, 12, 13]. In contrast, education may construct a “cognitive reserve” in early life and thus confer resistance to the accumulation of brain pathologies with aging [37–39]. Other mechanisms might also be involved, and future studies are needed to provide biological insights into the APOE ε4 alleles by educational attainment on dementia risk.

Similar significant interactions were observed between educational attainment and overall genetic susceptibility on dementia risk on both the multiplicative and additive scales. However, these interactions became non-significant after removing the APOE genotype from the PRS, indicating that the observed interactions between PRS and education were mainly driven by the APOE genotype.

The major strengths of this study include the prospective design, the large sample size, the availability of data for several major covariates for dementia, and the inclusion of PRS and the number of APOE ε4 alleles in evaluating the genetic risk profile. The consistent results of the interactions on both the multiplicative and additive scale ensured the robustness of our findings. We also acknowledge several potential limitations of this study. First, this observational study does not allow us to evaluate the causal or sequence relation among genetic variants, education level, and dementia risk. Second, despite the large size of the study and long follow-up period, the incidences of dementia were still relatively low, probably because the mean age of participants was only 73 years at the end of the follow-up period. In addition, incident dementia cases were ascertained through death registry and hospital inpatient records only, which might also limit the number of incident dementia cases. However, because of the universal health coverage in the UK, a previous study has shown that the dementia cases recorded in routinely collected hospital admission data are sufficiently reliable for epidemiological research [40]. Third, UK Biobank participants comprise a relatively healthy cohort and may not be demographically representative of the general UK population. Nonetheless, a valid assessment of exposure-disease relationships may not require a representative population [41]. Fourth, as the small sample size of non-White participants in the UKB (about 4% of the total population), only White participants were included in this study; our results might not be generalizable to other ethnic groups.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that the associations between educational attainment and dementia risk may vary according to the genetic profiles, especially the number of the APOE ε4 alleles. Higher educational attainment is related to a lower dementia risk only among those with high-risk genetic profiles. These results highlight the importance of early-life educational attainment in the prevention of dementia among those with high genetic risk.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource, approved project number 29256.

Author contribution

Dr. Qi had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Qi, Ma. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Qi, Ma. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Qi, Ma. Statistical analysis: Ma. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding

Lu Qi was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL071981, HL034594, HL126024), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK115679, DK091718, DK100383, DK078616).

Data availability

The genetic and phenotypic UK Biobank data are available on application to the UK Biobank (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).

Declarations

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the NHS National Research Ethics Service. The present analysis was approved by the Tulane University (New Orleans, LA) Institutional Review Board.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Organization WH. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. 2019 [PubMed]

- 2.Gatz M, Reynolds CA, Fratiglioni L, Johansson B, Mortimer JA, Berg S, et al. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(2):168. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, Damotte V, Naj AC, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019;51(3):414. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.T O’Brien J, Thomas A. Vascular dementia. The Lancet 2015 386 10004 1698 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Stocker H, Perna L, Weigl K, Möllers T, Schöttker B, Thomsen H et al. Prediction of clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, vascular, mixed, and all-cause dementia by a polygenic risk score and APOE status in a community-based cohort prospectively followed over 17 years. Mol Psychiatry 2020 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;278(16):1349. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160069041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.M Baumgart HMS, MC Carrillo SF. Summary of the evidence on modifiable risk factors for cognitive decline and dementia: a population-based perspective. Alzheimer’s & … 2015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Licher S, Ahmad S, Karamujić-Čomić H, Voortman T, Leening MJG, Ikram MA, et al. Genetic predisposition, modifiable-risk-factor profile and long-term dementia risk in the general population. Nat Med. 2019;25(9):1364. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lourida I, Hannon E, Littlejohns TJ, Langa KM, Hyppönen E, Kuźma E, et al. Association of lifestyle and genetic risk with incidence of dementia. JAMA. 2019;322(5):430. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kivipelto M, Rovio S, Ngandu T, Kåreholt I, Eskelinen M, Winblad B, et al. Apolipoprotein E ɛ4 magnifies lifestyle risks for dementia: a population-based study. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12(6b):2762. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelber RP, Petrovitch H, Masaki KH, Abbott RD, Ross GW, Launer LJ, et al. Lifestyle and the risk of dementia in Japanese-American men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):118. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Podewils LJ, Guallar E, Kuller LH, Fried LP, Lopez OL, Carlson M, et al. Physical activity, APOE genotype, and dementia risk: findings from the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161(7):639. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Gonneaud J, Fouquet M, Perrotin A, Mézenge F, Landeau B, et al. Interaction between years of education and APOE ε4 status on frontal and temporal metabolism. Neurology. 2015;85(16):1392. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, Gustafson DR, Kivipelto M, Pedersen NL, Skoog I, Windblad B, et al. Education halves the risk of dementia due to apolipoprotein ε4 allele: a collaborative study from the Swedish Brain Power initiative. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(5):1007. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015 12 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, Kong E, Maghzian O, Zacher M, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50(8):1112. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou T, Sun D, Li X, Ma H, Heianza Y, Qi L. Educational attainment and drinking behaviors: Mendelian randomization study in UK Biobank Mol Psychiatry 2019 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Carter AR, Gill D, Davies NM, Taylor AE, Tillmann T, Vaucher J et al. Understanding the consequences of education inequality on cardiovascular disease: Mendelian randomisation study BMJ 2019 365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Lyall DM, Ward J, Ritchie SJ, Davies G, Cullen B, Celis C, et al. Alzheimer disease genetic risk factor APOE e4 and cognitive abilities in 111,739 UK Biobank participants. Age Ageing. 2016;45(4):511. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Risch NJ, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, et al. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E type 2 allele for late onset Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet. 1994;7(2):180. doi: 10.1038/ng0694-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ripatti S, Tikkanen E, Orho-Melander M, Havulinna AS, Silander K, Sharma A, et al. A multilocus genetic risk score for coronary heart disease: case-control and prospective cohort analyses. The Lancet. 2010;376(9750):1393. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61267-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bycroft C, Freeman C, Petkova D, Band G, Elliott LT, Sharp K et al. Genome-wide genetic data on~ 500,000 UK Biobank participants. BioRxiv 2017 166298

- 24.Wilkinson T, Schnier C, Bush K, Rannikmäe K, Henshall DE, Lerpiniere C, et al. Identifying dementia outcomes in UK Biobank: a validation study of primary care, hospital admissions and mortality data. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(6):557. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00499-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VanderWeele TJ, Tchetgen EJT. Attributing effects to interactions. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.) 2014 25 5 711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Li Y, Ley SH, Tobias DK, Chiuve SE, VanderWeele TJ, Rich-Edwards JW et al. Birth weight and later life adherence to unhealthy lifestyles in predicting type 2 diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2015 351 h3672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.VanderWeele TJ, Knol MJ. A tutorial on interaction. Epidemiol. Methods. 2014;3(1):33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li R, Chambless L. Test for additive interaction in proportional hazards models. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):227. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small G, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261(5123):921. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.VanderWeele TJ, Robins JM. The identification of synergism in the sufficient-component-cause framework. Epidemiology. 2007;18(3):329. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000260218.66432.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blot WJ, Day NE. Synergism and interaction: are they equivalent. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110(1):99. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Evans DA, Aggarwal NT, Arnold SE, et al. Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele, AD pathology, and the clinical expression of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2003;60(2):246. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000042478.08543.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mortimer JA, Snowdon DA, Markesbery WR. The effect of APOE-ε4 on dementia is mediated by Alzheimer neuropathology. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(2):152. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318190a855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang L, Douet V, Bloss C, Lee K, Pritchett A, Jernigan TL, et al. Gray matter maturation and cognition in children with different APOE ε genotypes. Neurology. 2016;87(6):585. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Lee SJ, Wolters FJ, Ikram MK, Hofman A, Ikram MA, Amin N, et al. The effect of APOE and other common genetic variants on the onset of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia: a community-based cohort study. The Lancet Neurology. 2018;17(5):434. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30053-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM. The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2009;63(3):287. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Vemuri P. Resistance vs resilience to Alzheimer disease: clarifying terminology for preclinical studies. Neurology. 2018;90(15):695. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valenzuela MJ. Brain reserve and the prevention of dementia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(3):296. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f97b1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Del Ser T, Hachinski V, Merskey H, Munoz DG. An autopsy-verified study of the effect of education on degenerative dementia. Brain. 1999;122(12):2309. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.12.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown A, Kirichek O, Balkwill A, Reeves G, Beral V, Sudlow C, et al. Comparison of dementia recorded in routinely collected hospital admission data in England with dementia recorded in primary care. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2016;13(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12982-016-0053-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fry A, Littlejohns TJ, Sudlow C, Doherty N, Adamska L, Sprosen T, et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with those of the general population. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(9):1026. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The genetic and phenotypic UK Biobank data are available on application to the UK Biobank (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/).