Abstract

Background: Doxorubicin as an anti-cancer drug causes cardiotoxicity, limiting its tolerability and use. The mechanism of toxicity is due to free radical production and cardiomyocytes injury. This research evaluated Rheum turkestanicum (R.turkestanicum) extract against doxorubicin cardiotoxicity due to its considerable in vitro antioxidant activity.

Methods: Male Wistar rats received 2.5 mg/kg doxorubicin intraperitoneally every other day for 2 weeks to create an accumulative dose. R. turkestanicum was administrated at a dose of 100 and 300 mg/kg intraperitoneally from the second week for 7 days. On the 15th day, the animals were anesthetized and blood was collected from cardiac tissue for evaluation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), cardiac muscle creatinine kinase (CK-MB), troponin T (cTn-T), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and B-type natriuretic peptide brain natriuretic peptide. A cardiac homogenate was also collected to determine superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase Catalase Activity, malondialdehyde (MDA), and thiols. Histopathology was also performed.

Results: Doxorubicin increased all cardiac enzymes and malondialdehyde, correlating with a reduction in SOD, catalase, and thiols. Histopathology revealed extracellular edema, moderate congestion, and hemorrhage of foci. In contrast, administration of R. turkestanicum ameliorated these doxorubicin-induced pathophysiological changes.

Conclusion: This study revealed that the extract ameliorated doxorubicin-induced cardiac toxicity via modulation of oxidative stress-related pathways. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of R. turkestanicum indicated several components with potent pharmacological properties.

Keywords: Rheum turkestanicum, chemotherapy, doxorubicin, oxidative stress, herbal medicine, cardiotoxicity

Introduction

Doxorubicin is a commonly administered chemotherapeutic agent for a variety of cancers. However, doxorubicin’s utility is restricted due to its associated cardiotoxicity, with a reported incidence of toxicity of approximately 11% (Chatterjee et al., 2010). Additionally, another study showed that 2.2% of 4,000 patients who consumed doxorubicin had symptoms of heart failure (Bennink et al., 2004). This cardiotoxicity involves metabolic activation to a semiquinone, subsequent oxidative stress, and binding of lipid peroxidation products [such as malondialdehyde (MDA)] toward macromolecular targets (Ma et al., 2013). The administration of doxorubicin also attenuates antioxidant enzymes such as catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GSH), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (Kosoko et al., 2017). Moreover, doxorubicin stimulates apoptosis in cardiomyocytes resulting in congestive heart failure. Clinically, heart failure is associated with symptoms such as edema, orthopnea, fatigue, and increased venous pressure, which promote cardiac dysfunction (Yancy et al., 20132013). Following heart failure, the level of biomarkers such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatinine kinase (CK-MB), troponin T, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) elevate rapidly (Liquori et al., 2014). Therefore, researchers seek additional protective agents to mitigate doxorubicin’s cardiotoxicity. One such agent, dexrazoxane, can reduce doxorubicin toxicity; however, this drug interacts with the chemotherapeutic benefits of doxorubicin (Swain and Vici, 2004). Researchers are now investigating other natural compounds with lower side effects, including herbal medicines (Hosseini and Sahebkar, 2017). Phytochemical-rich products are candidates for reducing the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin because of their antioxidant and cardioprotective properties (Hosseini and Sahebkar, 2017). Rheum turkestanicum (R.turkestanicum) belongs to the polygonaceae family. It grows in Asia, especially in the northeast of Iran (Taheri and Assadi, 2013). The studies have reported that R. turkestanicum has beneficial effects in treating diabetes, hypertension, and cancer (Shiezadeh et al., 2013; Moradi et al., 2016; Boroushaki et al., 2019a; Moradzadeh, 2019; Ghorbani et al., 2021). This herb is composed of different chemical components, including anthraquinones (e.g., aloe-emodin, emodin glycosides, physione, and rhein), flavonoids (e.g., epicatechin and quercetin), alkanes (e.g., eicosane and heneicosane), and fatty acids (e.g., linoleic acid and 9-octadecenoic acid) (Hosseini et al., 2017). Therefore, the pharmacological properties of R. turkestanicum can be related to the presence of active ingredients (Ghorbani et al., 2019). One recent study showed R. turkestanicum reduced doxorubicin-induced toxicity in cardiomyocytes (H9c2 cell line) via modulation of oxidative stress (Hosseini and Rajabian, 2016). Also In another study cardioprotective effect of R. turkestanicum against isoprenaline was evaluated which showed anti-oxidant activity of extract reduced isoprenaline-induced cardiac toxicity (Hossini et al., 2022) In the current study, we have evaluated the cardioprotective effects of R. turkestanicum against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in an animal model.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Doxorubicin, ketamine hydrochloride/xylazine hydrochloride solution and 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA) were prepared from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, United States). Pyrogallol and 2,2′ -dinitro-5,5′ -dithiodibenzoic acid (DTNB) were obtained from Cayman (Michigan, United States). Other agents included alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (mancompany, 613,032), muscle, brain creatinine kinase (CK-MB) (Riton, R144), troponin T (Biomerieux, 415,386), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (mancompany, 613,036), and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) (Sigma Aldrich, RAB0386). CK-MB was measured by VIDAS device according to enzyme-linked fluorescent assay and other biochemical tests were carried out by autoanalyzer Hitachi 902.

Preparation of R. turkestanicum Extract

R. turkestanicum was collected from chenar trees around Khorasan and identified by a botanist. The voucher specimen is 21,377. The root of R. turkestanicum was dried and converted to a fine powder. The hydro-alcoholic extract was obtained by the Soxhlet apparatus. After 48 h, the extract was dried in a water bath and maintained at −18°C until use. The final yield of the extract was determined as 21% (w/w).

Animals

This project was done according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for Laboratory Animals and was confirmed by the Animal Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran (IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1399.425). Adult male albino Wistar rats (200–250 g) were housed at the Laboratory Animals Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, at 22 ± 4°C with a 12 h dark/light cycle. The animals had free access to standard laboratory chow and tap water ad libitum.

Experimental Protocol

The rats were divided into five groups, with eight rats in each group. Group 1 received normal saline 0.9% intraperitoneally (i.p.) for 14 days. Doxorubicin was administrated i. p. at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg in 6 equal injections for 2 weeks to create a cumulative dose (15 mg/kg body weight) (Arafa et al., 2014). Groups 3 and 4 received R. turkestanicum at doses of 100 and 300 mg/kg (Hosseini et al., 2017; Jahani Yazdi et al., 2020; Hossini et al., 2022) as i. p. one week after doxorubicin administration. R. turkestanicum was injected at a dose of 300 mg/kg to rats in the fifth group without administration of doxorubicin. On the 15th day, ketamine was injected at 75 mg/kg i. p to induce anesthesia. Three ml of blood was collected from the heart, then centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 rpm. The separated serums were kept at −20°C to determine biochemical parameters such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (mancompany, 613,032), muscle, and brain creatinine kinase (CK-MB) (Riton, R144), Troponin T (Biomerieux, 415,386), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) (Sigma Aldrich, RAB0386). The isolated cardiac tissue was homogenized in cold KCl solution (1.5%, pH = 7) to give a 10% homogenate, and used for suspension to measure thiol, malondialdehyde (MDA), an anti-oxidant enzyme levels.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis of R. turkestanicum

According to our previous study, the LC-MS analysis was performed using an AB SCIEX QTRAP (Shimadzu) liquid chromatography coupled with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Hossini et al., 2022). Liquid chromatography separation was performed on a Supelco C18 (15 mm × 2.1 mm × 3 μm) column. MS analysis was carried out in negative and positive ionization modes to monitor as many ions as possible and ensure that the most significant number of metabolites extracted from the sample was detected. The analysis was done at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The gradient analysis started with 95% of 0.2% aqueous formic acid, isocratic conditions were maintained for 1 min, and then a 14-min linear gradient to 40% acetonitrile with 0.2% formic acid was applied. From 15 to 35 min, the acidified acetonitrile was increased to 100%, followed by 5 min of 100% acidified acetonitrile and 5 min at the start conditions to re-equilibrate the column. The mass spectra were acquired in a range of 150–1,000 within 45 min of scan time. Mass feature extraction of the acquired LC-MS data and maximum detection of peaks were done using the MZmine analysis software package, version 2.3.

Lipid Peroxidation Analysis

Lipid peroxidation was assessed via MDA generation as previously reported (Boroushaki et al., 2019a). The samples were mixed with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) (0.67%) and trichloroacetic acid (10%), then boiled for 40 min. HCl and n-butanol were added to cooled samples, centrifuged, and the upper layer was measured spectrophotometrically at 535 nm. MDA concentration (M) was determined as: Absorbance/(1.56*105 cm−1M−1).

Determination of Thiols

Thiol concentrations were determined using DTNB as previously described (11). Briefly, Tris-EDTA buffer (pH = 8.6) was added to 50 µl of the homogenate, then the absorbance was read at 412 nm (A1). The solution was mixed with DTNB and again measured after 15 min (A2). DTNB was applied as blank. Total thiol concentration (mM) = (A2-A1-B)*0.7)/0.05*14.

Determination of Enzyme Markers and Biochemical Parameters

The level of markers such as LDH, CK-MB, cTnT, BNP and ALT was determined according to standard kits and manufacturer’s instructions.

Determination of Catalase Activity (CAT)

Catalase activity was determined according to (Aebi, 1984). This protocol’s based on the constant rate (k) (dimension: s-1, k) of hydrogen peroxide reduction measuring absorbance at 240 nm. The activity of CAT was expressed as K (rate constant) per liter.

Evaluation of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) Activity

Superoxide dismutase activity was determined colorimetrically according to (20). This procedure measures superoxide production by pyrogallol auto-oxidation, and the prevention of superoxide-dependent reduction of the tetrazolium dye to its Formosan by SOD was evaluated at 570 nm (Madesh and Balasubramanian, 1998).

Histopathological Analysis

The isolated hearts were fixed with 10% formalin solution for histopathological studies. After paraffinization of tissues, the slices of 3 mm thickness were prepared. Hematoxylin and Eosin were used to dye the sections for light microscopic analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism® software version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and presented as means ± SD. Significance was determined by One-Way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test.

Results

LC-MS Analysis of R. turkestanicum Extract

A total of 24 compounds were identified in the hydro-ethanol extract of R. turkestanicum using LC-MS analysis. These compounds include anthraquinones (e.g., emodin, emodin glycosides, physione, rhein, and its derivatives), fatty acids (9-octadecenoic acid), and flavonoids (e.g., epicatechin and quercetin). The extract also contained a high level of glucogallin, a phenolic compound formed from β-D-glucose and gallic acid (Hosseini et al., 2017). Identification of the compounds are shown in Table 1. The total ion chromatograms of R. turkestanicum extract in ESI− mode are shown in Figure 1. The MS spectral data were compared with the reported compounds in some previous literature. Figures 1A–D provide a representative chromatogram.

TABLE 1.

Peak assignment of metabolites in the hydro-ethanol extract of R.turkestanicum using LC-MS in the negative mode (Hossini et al., 2022).

| Peak no. | Compound | RT (min) | [M-1] (m/z) | Intensity (E) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6-methyl-rhein | 21.3 | 297.42 | 4.94 | Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 2 | 6-methyl-rhein-diacetate | 31.8 | 381.06 | 2.74 | Singh et al. (2005) |

| 3 | Emodin | 20.9 | 269.16 | 1.75 | Zhang and Liu (2004), Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 4 | Emodin-8-O-glucopyranoside | 18.0 | 431.28 | 2.24 | Ko et al. (1995), Matsuda et al. (2000) |

| 5 | Emodin glucoside | 18.2 | 431.34 | 1.64 | Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 6 | Revandchinone 1 | 17.1 | 520.98 | 4.04 | Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 7 | Revandchinone 2 | 20.0 | 674.58 | 3.84 | Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 8 | Revandchinone 3 | 2.5 | 577.68 | 2.44 | Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 9 | Chrysophanol | 20.5 | 254.94 | 2.74 | Zhang and Liu (2004), Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 10 | Epicatechin | 44.4 | 289.08 | 2.04 | Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 11 | Ethyl linoleate | 44.2 | 307.62 | 3.84 | Ragasa, (2017) |

| 12 | Glucogallin | 32.0 | 331.08 | 2.24 | Thakur et al. (1989) |

| 13 | Danthron | 37.7 | 239.22 | 2.24 | Chen et al. (2019) |

| 14 | Methyleugenol | 19.1 | 177.3 | 9.14 | Miyazawa et al. (1996) |

| 15 | Physcion | 19.6 | 283.44 | 2.74 | Zhang and Liu (2004), Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 16 | Piceatannol | 23.1 | 243.36 | 8.74 | Raalh and Tsouprasd, (2003) |

| 17 | Epigallocatechol | 44.5 | 305.04 | 6.74 | Agarwal et al. (2001) |

| 18 | Cadinen | 10.9 | 204.36 | 3.14 | Miyazawa et al. (1996) |

| 19 | 9-octadecenoic acid | 30.2 | 281.10 | 2.04 | Ragasa, (2017) |

| 20 | Quercetin | 44.9 | 300.60 | 3.64 | Ragasa, (2017) |

| 21 | Rhaponticin-β-D-glucoside | 21.1 | 717.00 | 2.65 | Ragasa, (2017) |

| 22 | Rhein | 19.3 | 283.38 | 2.44 | Zhang and Liu (2004), Zargar et al. (2011) |

| 23 | Rheochrysin | 20.4 | 444.78 | 6.24 | Youngken (1946), Agarwal et al. (2001) |

| 24 | Rhododendrin | 19.9 | 327.36 | 2.14 | Dehghan et al. (2018) |

FIGURE 1.

Chromatogram and corresponding mass adducts which was reported in our recent work (Hossini et al., 2022). (A) The total ion chromatogram of R.turkestanicum using LC-MS in the positive mode. (B) Chromatogram of emodin and corresponding mass adduct, [M-H], at m/z 269.16. (C) Mass spectra of 6-methyl-rhein, [M-H], at m/z 297.42. (D) Mass spectra of revandchinone 1, [M-H], at m/z 520.98.

Effect of R.turkestanicum on Cardiac Parameters

Our results revealed that doxorubicin increased the level of BNP, CK-MB, cTnT, LDH and ALT significantly in comparison with the control group (p < 0.001) (Figure 3 ). At the dose of 100 mg/kg, R. turkestanicum significantly reduced levels of BNP (p < 0.05), CK-MB (p < 0.05), cTn-T (p < 0.01), and ALT (p < 0.05). The higher dose of the extract (300 mg/kg) further abrogated doxorubicin-induced elevations of marker enzymes, including BNP, cTn-T, CK-MB and ALT (p < 0.001), and LDH (p < 0.01) in comparison with doxorubicin alone (Figure 2). R. turkestanicum alone had no effect on any of these cardiac enzymes.

FIGURE 3.

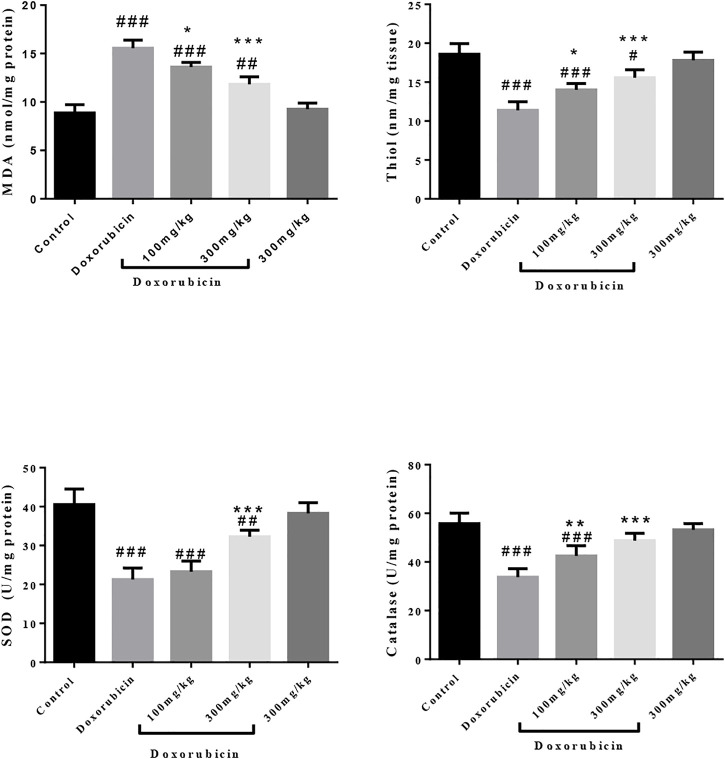

Effect of R. turkestanicum on oxidative stress and antioxidant enzymes. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 in comparison with the control group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 in comparison with doxorubicin.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of R. turkestanicum on the level of serum BNP, cTnT, CK-MB, LDH and ALT. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 in comparison with the control group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 in comparison with doxorubicin.

Effect of R.turkestanicum on Oxidative Stress

As shown in Figure 3, overall, doxorubicin increased oxidative stress while simultaneously reducing antioxidant defenses. Specifically, the cardiotoxic drug increased MDA production (p < 0.001) and reduced thiols (p < 0.001), and enzymatic activities of SOD and catalase (p < 0.001) compared to control. Administration of R. turkestanicum ameliorated doxorubicin-induced changes. At dosages of both 100 mg/kg and 300 mg/kg, the extract prevented oxidative stress (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively) and restored thiol content (p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively). Similarly, both dosages of R. turkestanicum significantly increased both SOD (p < 0.001 at 300 mg/kg) and catalase (p < 0.01 and p < 0.001 at 100 mg/kg and 300 mg/kg, respectively). The extract alone had no effect on either biomarkers of oxidative stress and antioxidant defenses.

Histopathological Analysis

Microscopic examination of the doxorubicin-treated group showed mild to moderate degrees of mostly extracellular edema and moderate congestion and small foci of hemorrhage (Figure 4). The tissue changes in groups 3 and 4 (doxorubicin + extract), included mild edema and mild congestion. These changes were similar but lessened at the 300 mg/kg dose. Again, R. turkestanicum alone had no effect on histopathology.

FIGURE 4.

The effects of R. turkestanicum on cardiac histopathology. (A) (H&E, ×400) Control group shows normal cardiac tissue, (B) (H&E ×400) doxorubicin group shows edema (black arrows) and (C) (H&E ×400) doxorubicin group indicates edema (blue arrows) and hemorrhage (black arrows), (D) (H&E ×400) R.turkestanicum + doxorubicin (100 mg/kg) shows mild edema (black arrows), (E) (H&E ×400) R.turkestanicum + doxorubicin (300 mg/kg) also exhibits mild edema (black arrows), and (F) (H&E ×400) R.turkestanicum (300 mg/kg) shows no obvious pathological changes and is similar to control group.

Discussion

Although doxorubicin is a drug of choice for various cancer treatments, its cardiotoxicity restricts its clinical utility. The primary finding of this study is that R. turkestanicum reduced doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by modulating oxidative stress and antioxidant defenses. The extract also reduced the drug’s effect on pathological abnormalities.

Several mechanisms may be responsible for doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. These mechanisms include mitochondrial injury, ROS generation, intracellular Ca+2 dysregulation, inflammatory cytokine production, and myocyte damage (Rawat et al., 2021; Sheibani et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2022).

Doxorubicin is metabolized via several oxidative/reductive enzymes into a semiquinone, which increases the generation of superoxide radicals via redox cycling. Relatedly, doxorubicin facilitates oxidative stress by impairing antioxidant defense enzymes such as SOD and catalase. Concomitantly, this oxidative stress is associated with a depletion of glutathione (GSH), the primary thiol antioxidant within cells. Reduced GSH levels are also important in the doxorubicin-induced downregulation of GSH-Px 4 (Tadokoro et al., 2020). Restoration of GSH status protects against the drug’s cardiotoxicity (Mohamed et al., 2000). Interestingly, Hosseini et al. reported that R. turkestanicum prevented doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, similar to intervention with N-acetylcysteine, a structurally related non-protein thiol antioxidant (Hosseini and Rajabian, 2016). Maintenance of GSH-dependent antioxidant defenses and various other compounds, including carvedilol, omega-3 fatty acids, and dexrazoxane, attenuate some of the drugs’ toxicity (Takemura and Fujiwara, 2007).

Doxorubicin preferentially accumulates in the cardiac mitochondria and is associated with cardiac toxicity. For example, doxorubicin significantly reduces mitochondrial complex 1 activity and can promote apoptosis (Marcillat et al., 1989; Basit et al., 2017; Rawat et al., 2021). Additionally, the expression of PARP1 in cardiomyocytes impairs mitochondrial function (Wen et al., 2018). Therefore, stabilizing the mitochondria can prevent doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity (Montaigne et al., 2010). Indeed, recent studies have reported that natural products may be appropriate alternatives for chemical agents in various diseases (Momtazi et al., 2017; Bagherniya et al., 2018; Alidadi et al., 2020; Soltani et al., 2021). One such natural product, R. turkestanicum, belongs to the Polygonaceae family and is composed of active ingredients with various pharmacological and biochemical properties (Ghorbani et al., 2019). The current study supports an earlier report that R. turkestanicum can reduce doxorubicin-induced toxicity in myocytes (Hosseini and Rajabian, 2016). In that study, the extract’s protective effects against doxorubicin were evaluated in vivo. Our findings confirm doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via mechanisms involving elevated oxidative stress and reduced antioxidant defenses (Songbo et al., 2019). Other studies have found that R. turkestanicum could decrease oxidative stress in endothelial cells (Hosseini et al., 2020).

Patients receiving doxorubicin exhibit left ventricular dysfunction demonstrated by elevated CK-MB and BNP activities (Pongprot et al., 2012). Additionally, animal studies have reported increased CK-MB, LDH, BNP, and cTnT activities following doxorubicin administration (Arafa et al., 2014; Kulkarni and Swamy, 2015; Nugraha et al., 2020; Syahputra et al., 2021). Moreover, previous research has also reported that doxorubicin elevates ALT (Barakat et al., 2018); our findings support these previous ones of doxorubicin-induced clinical enzyme alterations. Our findings also support that R. turkestanicum protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by restoring cellular antioxidant defenses and as an antioxidant in various cells and toxicity models (Hosseini et al., 2018; Boroushaki et al., 2019a; Boroushaki et al., 2019b; Hosseini et al., 2020). The protection by the plant is also associated with improvements in LDH and creatinine phosphokinase activities (Hosseini et al., 2017; Hossini et al., 2022). The protective effect of R. turkestanicum observed in our study is potentially attributed to the presence of specific plant bioactives. Specifically, R. turkestanicum is rich in molecules offering cellular and tissue protection, including emodin, rhein, epicatechin, and others, as we show in Table 1 and as reported by others Dehghan et al., 2018. As one example of these bioactives, it was reported that chrysophanol could improve cardiac function via inhibition of apoptosis, modulation of oxidative stress, and prevention of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK 1/2) activation (Xie and Li, 2020). Additionally, chrysophanol reduced doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by suppressing mitochondrial swelling, mitochondrial depolarization, and PARP1 inhibition (Lu et al., 2019). Epicatechin reduces blood pressure in hypertensive patients and infarct size (Yamazaki et al., 2008; Yamazaki et al., 2010). Another bioactive in R. turkestanicum, rhein, had demonstrated cytoprotection against oxidative stress-induced endothelial cell injury (Zhong et al., 2012). Finally, the cardioprotective effects of emodin and quercetin have been reported (Wu et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2014) and include the potential modulation by emodin of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via reduced Toll-like receptor four and P38 mitogen activating protein kinase (P38 MAPK) expression (Zhang et al., 2016).

Conclusion

The protective effect of R. turkestanicum against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity is attributed, at least in part, to the plant’s antioxidant properties and enhancement of cardiac tissue antioxidant defenses. However, our study has some limitations, such as the lack of cardiac function evaluation by echocardiography and the unknown mechanistic effects of co-administration of R. turkestanicum and doxorubicin. These considerations will be necessary in future studies. Future studies are also warranted to test the impact of extract upon oral administration, and perform quantitative analysis of R. turkestanicum extract and identify the main active phytochemicals responsible for the plant’s cardioprotection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice Chancellery for Research and Technology, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, upon a reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran (IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1399.425).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AH. Supervision: AH, AS, AE, and YA. Investigation: AH, M-KS, AR, and SB-N. Writing-original draft: AH, M-KS, AR, and SB-N. Writing-review and editing: EG, AS, AE, and YA. Approval of the final version: All authors.

Funding

Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (AH) and UAEU Program for Advanced Research, grant number 31S398-UPAR (YA).

Conflict of Interest

EG is employed by Isagenix International, LLC.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Aebi H. (1984). Catalase In Vitro . Methods Enzymol. 105, 121–126. 10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S. K., Singh S. S., Lakshmi V., Verma S., Kumar S. (2001). Chemistry and Pharmacology of Rhubarb (Rheum Species)—A Review. J. Sci. Industrial Res. 60 (1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Alidadi M., Jamialahmadi T., Cicero A. F. G., Bianconi V., Pirro M., Banach M., et al. (2020). The Potential Role of Plant-Derived Natural Products in Improving Arterial Stiffness: A Review of Dietary Intervention Studies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 99, 426–440. 10.1016/j.tifs.2020.03.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arafa M. H., Mohammad N. S., Atteia H. H., Abd-Elaziz H. R. (2014). Protective Effect of Resveratrol against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiac Toxicity and Fibrosis in Male Experimental Rats. J. Physiol. Biochem. 70 (3), 701–711. 10.1007/s13105-014-0339-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagherniya M., Nobili V., Blesso C. N., Sahebkar A. (2018). Medicinal Plants and Bioactive Natural Compounds in the Treatment of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Clinical Review. Pharmacol. Res. 130, 213–240. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat B. M., Ahmed H. I., Bahr H. I., Elbahaie A. M. (2018). Protective Effect of Boswellic Acids against Doxorubicin-Induced Hepatotoxicity: Impact on Nrf2/HO-1 Defense Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 8296451. 10.1155/2018/8296451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basit F., van Oppen L. M., Schöckel L., Bossenbroek H. M., van Emst-de Vries S. E., Hermeling J. C., et al. (2017). Mitochondrial Complex I Inhibition Triggers a Mitophagy-dependent ROS Increase Leading to Necroptosis and Ferroptosis in Melanoma Cells. Cell Death Dis. 8 (3), e2716. 10.1038/cddis.2017.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennink R. J., van den Hoff M. J., van Hemert F. J., de Bruin K. M., Spijkerboer A. L., Vanderheyden J. L., et al. (2004). Annexin V Imaging of Acute Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity (Apoptosis) in Rats. J. Nucl. Med. 45 (5), 842–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroushaki M. T., Fanoudi S., Mollazadeh H., Boroumand-Noughabi S., Hosseini A. (2019). Reno-protective Effect of Rheum Turkestanicum against Gentamicin-Induced Nephrotoxicity. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 22 (3), 328–333. 10.22038/ijbms.2019.31552.7597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroushaki M. T., Fanoudi S., Rajabian A., Boroumand S., Aghaee A., Hosseini A. (2019). Evaluation of Rheum Turkestanicum in Hexachlorobutadien-Induced Renal Toxicity. Drug Res. (Stuttg) 69 (8), 434–438. 10.1055/a-0821-5653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee K., Zhang J., Honbo N., Karliner J. S. (2010). Doxorubicin Cardiomyopathy. Cardiology 115 (2), 155–162. 10.1159/000265166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhao C., He R., Zhou M., Liu Y., Guo X., et al. (2019). Danthron Suppresses Autophagy and Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Doxorubicin. Toxicol Vitro 54, 345–353. 10.1016/j.tiv.2018.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehghan H., Salehi P., Amiri M. S. (2018). Bioassay-guided Purification of α-amylase, α-glucosidase Inhibitors and DPPH Radical Scavengers from Roots of Rheum Turkestanicum. Industrial Crops Prod. 117, 303–309. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.02.086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Q., Chen L., Lu Q., Sharma S., Li L., Morimoto S., et al. (2014). Quercetin Attenuates Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity by Modulating Bmi-1 Expression. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171 (19), 4440–4454. 10.1111/bph.12795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani A., Amiri M. S., Hosseini A. (2019). Pharmacological Properties of Rheum Turkestanicum Janisch. Heliyon 5 (6), e01986. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani A., Hosseini A., Mirzavi F., Hooshmand S., Amiri M. S., Jafarian A. H., et al. (2021). Protective Effects of Rheum Turkestanicum Janischagainst Diethylnitrosamine-Induced Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Rats. Res. Square. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-528331/v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini A., Fanoudi S., Mollazadeh H., Aghaei A., Boroushaki M. T. (2018). Protective Effect of Rheum Turkestanicum against Cisplatin by Reducing Oxidative Stress in Kidney Tissue. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 10 (2), 66–71. 10.4103/JPBS.JPBS_9_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini A., Mollazadeh H., Amiri M. S., Sadeghnia H. R., Ghorbani A. (2017). Effects of a Standardized Extract of Rheum Turkestanicum Janischew Root on Diabetic Changes in the Kidney, Liver and Heart of Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 86, 605–611. 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini A., Sahebkar A. (2017). Reversal of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Using Phytotherapy: a Review. J. Pharmacopuncture 20 (4), 243–256. 10.3831/KPI.2017.20.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini A., Sheikh S., Soukhtanloo M., Malaekeh-Nikouei B., Rajabian A. (2020). The Effect of Hydro-Alcoholic Extract of Rheum Turkestanicum Roots against Oxidative Stress in Endothelial Cells. Int. J. Prev. Med. 11, 122. 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_386_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini A., Rajabian A. (2016). Protective Effect of Rheum Turkestanikum Root against Doxorubicin-Induced Toxicity in H9c2 Cells. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 26, 347–351. 10.1016/j.bjp.2016.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hossini A., Rajabian A., Sobhanifar M. A., Alavi M. S., Taghipour Z., Hasanpour M., et al. (2022). Attenuation of Isoprenaline-Induced Myocardial Infarction by Rheum Turkestanicum. Biomed. Pharmacother. 148, 112775. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahani Yazdi A., Javanshir S., Soukhtanloo M., Jalili-Nik M., Jafarian A. H., Iranshahi M., et al. (2020). Acute and Sub-acute Toxicity Evaluation of the Root Extract of Rheum Turkestanicum Janisch. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 43 (6), 609–615. 10.1080/01480545.2018.1561713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko S. K., Whang W. K., Kim I. H. (1995). Anthraquinone and Stilbene Derivatives from the Cultivated Korean Rhubarb Rhizomes. Arch. Pharm. Res. 18 (4), 282–288. 10.1007/bf02976414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kosoko A., Olurinde O., Oyinloye O. (2017). Attenuation of Doxorubicin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Organ Damage in Experimental Rats by Theobroma Cacao Stem Bark. Jocamr 2, 1–27. 10.9734/jocamr/2017/30604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni J., Swamy A. V. (2015). Cardioprotective Effect of Gallic Acid against Doxorubicin-Induced Myocardial Toxicity in Albino Rats. Indian J. Health Sci. Biomed. Res. (KLEU) 8 (1), 28. 10.4103/2349-5006.158219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liquori M. E., Christenson R. H., Collinson P. O., Defilippi C. R. (2014). Cardiac Biomarkers in Heart Failure. Clin. Biochem. 47 (6), 327–337. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Li J., Hu Y., Guo Z., Sun D., Wang P., et al. (2019). Chrysophanol Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Suppressing Cellular PARylation. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 9 (4), 782–793. 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Wang Y., Zheng D., Wei M., Xu H., Peng T. (2013). Rac1 Signalling Mediates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity through Both Reactive Oxygen Species-dependent and -independent Pathways. Cardiovasc Res. 97 (1), 77–87. 10.1093/cvr/cvs309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madesh M., Balasubramanian K. A. (1998). Microtiter Plate Assay for Superoxide Dismutase Using MTT Reduction by Superoxide. Indian J. Biochem. Biophys. 35 (3), 184–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcillat O., Zhang Y., Davies K. J. (1989). Oxidative and Non-oxidative Mechanisms in the Inactivation of Cardiac Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Components by Doxorubicin. Biochem. J. 259 (1), 181–189. 10.1042/bj2590181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H., Kageura T., Morikawa T., Toguchida I., Harima S., Yoshikawa M. (2000). Effects of Stilbene Constituents from Rhubarb on Nitric Oxide Production in Lipopolysaccharide-Activated Macrophages. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 10 (4), 323–327. 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00702-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa M., Minamino Y., Kameoka H. (1996). Volatile Components of the Rhizomes ofRheum Palmatum L. Flavour Fragr. J. 11 (1), 57–60. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed H. E., El-Swefy S. E., Hagar H. H. (2000). The Protective Effect of Glutathione Administration on Adriamycin-Induced Acute Cardiac Toxicity in Rats. Pharmacol. Res. 42 (2), 115–121. 10.1006/phrs.1999.0630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momtazi A. A., Banach M., Pirro M., Katsiki N., Sahebkar A. (2017). Regulation of PCSK9 by Nutraceuticals. Pharmacol. Res. 120, 157–169. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaigne D., Marechal X., Baccouch R., Modine T., Preau S., Zannis K., et al. (2010). Stabilization of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Isolated Rat Heart. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 244 (3), 300–307. 10.1016/j.taap.2010.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi M.-T., Asadi-Samani M., Bahmani M. (2016). Hypotensive Medicinal Plants According to Ethnobotanical Evidence of Iran: A Systematic Review. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 9 (5), 416–426. [Google Scholar]

- Moradzadeh M. (2019). Rheum Turkestanicum Induced Apoptosis through ROS without a Differential Effect on Human Leukemic Cells. Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 14, e12198. 10.5812/jjnpp.12198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha S. E., Yuandani E., Nasution E. S., Syahputra R. A. (2020). Investigation of Phytochemical Constituents and Cardioprotective Activity of Ethanol Extract of Beetroot (Beta Vulgaris. L) on Doxorubicin Induced Toxicity in Rat. Rjc 13 (02), 973–978. 10.31788/rjc.2020.1325601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pongprot Y., Sittiwangkul R., Charoenkwan P., Silvilairat S. (2012). Use of Cardiac Markers for Monitoring of Doxorubixin-Induced Cardiotoxicity in Children with Cancer. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 34 (8), 589–595. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31826faf44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raalh A., Tsouprasd G. (2003). “Hydroxystilbenes in the Roots of Rheum Rhaponticum,” in Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Sciences, Chemistry (Estonian Academy Publishers; ). [Google Scholar]

- Ragasa C. Y. (2017). Chem. Const. Rheum ribes L 9 (1), 65–69. 10.25258/ijpapr.v9i1.8041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat P. S., Jaiswal A., Khurana A., Bhatti J. S., Navik U. (2021). Doxorubicin-induced Cardiotoxicity: An Update on the Molecular Mechanism and Novel Therapeutic Strategies for Effective Management. Biomed. Pharmacother. 139, 111708. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani M., Azizi Y., Shayan M., Nezamoleslami S., Eslami F., Farjoo M. H., et al. (2022). Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: An Overview on Pre-clinical Therapeutic Approaches. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 22 (4), 292–310. 10.1007/s12012-022-09721-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiezadeh F., Mousavi S. H., Amiri M. S., Iranshahi M., Tayarani-Najaran Z., Karimi G. (2013). Cytotoxic and Apoptotic Potential of Rheum Turkestanicum Janisch Root Extract on Human Cancer and Normal Cells. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 12 (4), 811–819. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. S., Pandey S., Singh R., Agarwal S. K. (2005). 1, 8-Dihydroxyanthraquinone Derivatives from Rhizomes of Rheum Emodi Wall. Indian J. Chem. Sect. B 44 (7). [Google Scholar]

- Soltani S., Boozari M., Cicero A. F. G., Jamialahmadi T., Sahebkar A. (2021). Effects of Phytochemicals on Macrophage Cholesterol Efflux Capacity: Impact on Atherosclerosis. Phytother. Res. 35 (6), 2854–2878. 10.1002/ptr.6991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songbo M., Lang H., Xinyong C., Bin X., Ping Z., Liang S. (2019). Oxidative Stress Injury in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 307, 41–48. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2019.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain S. M., Vici P. (2004). The Current and Future Role of Dexrazoxane as a Cardioprotectant in Anthracycline Treatment: Expert Panel Review. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 130 (1), 1–7. 10.1007/s00432-003-0498-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syahputra R. A., Harahap U., Dalimunthe A., Pandapotan M., Satria D. (2021). Protective Effect of Vernonia Amygdalina Delile against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Heliyon 7 (7), e07434. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadokoro T., Ikeda M., Ide T., Deguchi H., Ikeda S., Okabe K., et al. (2020). Mitochondria-dependent Ferroptosis Plays a Pivotal Role in Doxorubicin Cardiotoxicity. JCI insight 5 (9). 10.1172/jci.insight.132747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri G., Assadi M. (2013). A Synopsis of the Genus Rheum (Polygonaceae) in Iran with Description of Three New Species. Rostaniha 14 (1), 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Takemura G., Fujiwara H. (2007). Doxorubicin-induced Cardiomyopathy from the Cardiotoxic Mechanisms to Management. Prog. Cardiovasc Dis. 49 (5), 330–352. 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur R., Puri H. S., Husain A. (1989). Major Medicinal Plants of India. Vol. 12. India: Central Institute of medicinal and aromatic plants Lucknow. [Google Scholar]

- Wen J. J., Yin Y. W., Garg N. J. (2018). PARP1 Depletion Improves Mitochondrial and Heart Function in Chagas Disease: Effects on POLG Dependent mtDNA Maintenance. PLoS Pathog. 14 (5), e1007065. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B. B., Leung K. T., Poon E. N. (2022). Mitochondrial-Targeted Therapy for Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (3), 1912. 10.3390/ijms23031912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Tu X., Lin G., Xia H., Huang H., Wan J., et al. (2007). Emodin-mediated Protection from Acute Myocardial Infarction via Inhibition of Inflammation and Apoptosis in Local Ischemic Myocardium. Life Sci. 81 (17-18), 1332–1338. 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X. J., Li C. Q. (2020). Chrysophanol Protects against Acute Heart Failure by Inhibiting JNK1/2 Pathway in Rats. Med. Sci. Monit. 26, e926392. 10.12659/MSM.926392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K. G., Romero-Perez D., Barraza-Hidalgo M., Cruz M., Rivas M., Cortez-Gomez B., et al. (2008). Short- and Long-Term Effects of (-)-epicatechin on Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 295 (2), H761–H767. 10.1152/ajpheart.00413.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K. G., Taub P. R., Barraza-Hidalgo M., Rivas M. M., Zambon A. C., Ceballos G., et al. (2010). Effects of (-)-epicatechin on Myocardial Infarct Size and Left Ventricular Remodeling after Permanent Coronary Occlusion. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55 (25), 2869–2876. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy C. W., Jessup M., Bozkurt B., Butler J., Casey D. E., Drazner M. H., et al. (20132013). 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: Executive Summary: a Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 128 (16), 1810–1852. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngken H. W. (1946). Studies on Indian Rhubarb; Rheum Emodi. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 35 (5), 148–154. 10.1002/jps.3030350504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zargar B. A., Masoodi M. H., Ahmed B., Ganie S. A. (2011). Phytoconstituents and Therapeutic Uses of Rheum Emodi Wall. Ex Meissn. Food Chem. 128 (3), 585–589. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.03.083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. X., Liu M. C. (2004). Separation Procedures for the Pharmacologically Active Components of Rhubarb. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 812 (1-2), 175–181. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Lin C., Yang X., Wang Y., Fang Y.-F., Wang F. (2016). Effect of Emodin on the Expression of TLR4 and P38MAPK in Mouse Cardiac Tissues with Viral Myocarditis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 9 (10), 10839–10845. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X. F., Huang G. D., Luo T., Deng Z. Y., Hu J. N. (2012). Protective Effect of Rhein against Oxidative Stress-Related Endothelial Cell Injury. Mol. Med. Rep. 5 (5), 1261–1266. 10.3892/mmr.2012.793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, upon a reasonable request.