Abstract

Although a high prevalence of COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis has been reported, it is still difficult to distinguish between colonization with Aspergillus fumigatus and infection. Concomitantly, similarities between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and hypersensitivity pneumonitis were suggested. The objective of this study was to investigate retrospectively if precipitin assays targeting A. fumigatus could have been useful in the management of SARS-CoV-2 patients hospitalized in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in 2020. SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients were screened for Aspergillus co-infection using biomarkers (galactomannan antigen, qPCR) and culture of respiratory samples (tracheal aspirates and bronchoalveolar lavage). For all these patients, clinical data, ICU characteristics and microbial results were collected. Electrosyneresis assays were performed using commercial A. fumigatus somatic and metabolic antigens. ELISA were performed using in-house A. fumigatus purified antigen and recombinant antigens.

Our study population consisted of 65 predominantly male patients, with a median ICU stay of 22 days, and a global survival rate of 62%. Thirty-five patients had at least one positive marker for Aspergillus species detection. The number of arcs obtained by electrosyneresis using the somatic A. fumigatus antigen was significantly higher for these 35 SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients (P 0.01, Welch's t-test). Our study showed that SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients with a positive marker for Aspergillus species detection more often presented precipitins towards A. fumigatus. Serology assays could be an additional tool to assess the clinical relevance of the Aspergillus species in respiratory samples of SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients.

Lay Summary

This study showed retrospectively that precipitin assays, such as electrosyneresis, could be helpful to distinguish between colonization and infection with Aspergillus fumigatus during the management of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS CoV-2) patients in an intensive care unit.

Keywords: precipitins, SARS-CoV-2, tracheal aspirates, Aspergillus fumigatus, electrosyneresis, somatic antigen

Introduction

During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, similarities between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) were hypothesized.1,2 HP are interstitial lung diseases characterized by a type III hypersensitivity reaction to microbial antigens, which is mediated by the formation of antigen-antibody aggregates called immune complexes.3 The papers reporting a relationship between SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia and HP highlighted the potential role of immune complexes in the occurrence of the hyper-inflammation response, characterized by the release of proinflammatory cytokines and the influx of polynuclear cells (also called “cytokine storm”).1,2

At the same time, several papers reported clinical cases of fungal superinfections of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia, called COVID -19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA).4,5 Guidelines to better define and manage CAPA were published in 2021.6

Several precipitation reactions that allow a macroscopic visualization of the antigen-antibody reaction by generating precipitation arcs, are applied for the serological diagnosis of HP.7,8 Among them, electrosyneresis is performed on cellulose acetate sheets while other methods such as double diffusion and immune-electrophoresis are performed on agar gel; electrosyneresis was previously shown more performant for the differential serodiagnosis of HP.9

The first objective of this study was to investigate retrospectively if precipitin assays targeting A. fumigatus could have been useful in the management of SARS-CoV-2 patients hospitalized in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in 2020. The second objective of this study was also to assess retrospectively the contribution of ELISA assays using in-house purified and recombinant antigens from A. fumigatus (Glucose-6-isomerase and Glu/Leu/Phen/Val dehydrogenase).10–11

Methods

Fungal screening of SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients

In total, 225 SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients were managed between March 2020 and December 2020 at the ICU of the University Hospital of Besancon. The fungal screening was performed prospectively on a weekly basis in all patients. Respiratory samples (tracheal aspirates, broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL)) were cultivated on Sabouraud media. Identification of the fungal species was performed macroscopically, microscopically and verified using Bruker MALDI-TOF techniques. Serum samples were used to measure the galactomannan antigen using an ELISA assay (Platelia Aspergillus EIA; Bio-Rad, Marnes la Coquette, France) and to detect A. fumigatus DNA by qPCRs using in-house techniques.12

During both the first COVID-19 wave in France (March 2020-May 2020), and the second one (October 2020-December 2020), 16/135 and 19/90 SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients presented a positive marker for Aspergillus species detection during their ICU stay (either a positive culture in tracheal aspirate, a positive culture in BAL, a positive galactomannan in serum, or a positive A. fumigatus qPCR in serum). Overall, 35 SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients (35/225; 15.5%) were included retrospectively in the “A. fumigatus group”.

Thirty SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients were randomly chosen among the 185 patients with no positive marker for Aspergillus species detection during their ICU stay (30/225; 13.3%) to be included in the “control group”.

For all patients included in the study, clinical data, residence details, ICU characteristics, and microbial results were collected retrospectively.

During the COVID-19 waves of 2020, the galactomannan antigen was locally measured only in the serum of SARS-CoV-2 patients; Respiratory samples were considered as a risk of exposure for the technicians.

Electrosyneresis on cellulose acetate

Electrosyneresis assays were performed retrospectively for all SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients included. Electrosyneresis was performed on residual sera that were sampled initially to measure the galactomannan antigen, in median 6 days [1-26] after the ICU admission.

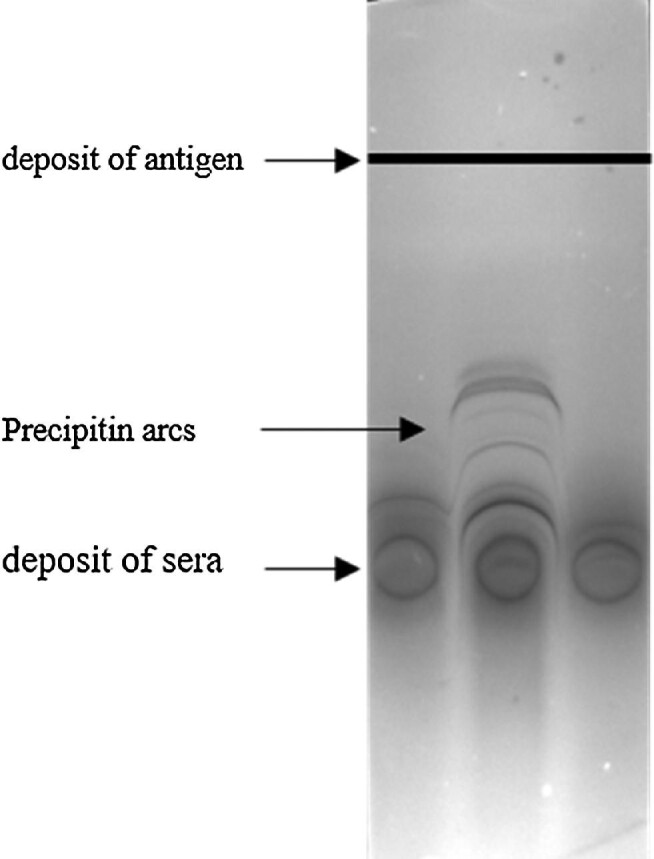

Electrosyneresis assays were performed using commercial A. fumigatus somatic and metabolic antigens (R-Biopharm®,St Didier au Mont d'Or, France) and commercial cellulose acetate sheets (Cellogel electrophoresis®, Milano, Italy). Briefly, samples of 15 μl of each serum were placed on three spots on the anode side and a 15-μl line of somatic antigen was placed on the cathode side 3.5 cm from the first deposit (Figure 1). The samples were washed and stained after 125 min of migration in a 90 mV current, as recommended by the supplier. The number of arcs was determined for each serum by two independent readers using a magnifying glass.

Figure 1.

Illustration of precipitation arcs obtained by electrosyneresis.

ELISA tests

ELISA were performed using an in-house proteic purified antigen, which depart from in-house somatic antigen that is further submitted to an enzymatic lysis of cell wall polyosids, protein acidic precipitation and acetone purification8 and ii) recombinant antigens, Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (G6PI) and Glu/Leu/Phen/Val dehydrogenase (GLPV), selected among immunogenic proteins from Aspergillus fumigatus in a previous study.10,11

Briefly, the wells of 96-well plates (PolySorp Immunomodule®, Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) were coated by incubation with 200 μl of 1 μg/ml recombinant antigen or purified antigen solution in 50 mmol/l K2HPO4 buffer, pH 8.5, at 4°C for 48 h. ELISA tests for specific IgG were then conducted, as described previously.10,11 Optical densities at 450 nm were read with a spectrophotometer (VictorTM 2 Multilabel Counter, PerkinElmer, Courtaboeuf, France).

ELISA was performed on residual sera sampled in median 6 days [1-26] after the ICU admission.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Jamovi, version 2.2. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant. In order to compare frequencies between the two defined groups, Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test (when the theoretical numbers were too small) were used. Student's or Welch t-tests were used to compare means based on the equality of variances.

Results

Characteristics of the studied population

The study population consisted of 65 predominantly (80%) male SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients, with a median age of 72 years, a median ICU stay of 22 days and a global survival rate of 62%.

No significant difference was observed between the two studied groups in terms of mean age at admission, sex ratio or residence type (urban or rural) (Table 1). Risk factors comparison showed that patients from the “A. fumigatus group’’ had significantly more frequently chronic respiratory diseases, such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), than patients from the “control group” (in mean ± SD, respectively, 0.34 ± 0.6 vs 0.07 ± 0.25, P 0.016 Welch's t-test; Table 1). Indeed, eight patients from the “A. fumigatus group’’ had asthma or COPD and two patients from the “A. fumigatus group’’ had both asthma and COPD (10/35 patients with chronic respiratory diseases) while only two patients from the “control group” had COPD (2/30 patients with chronic respiratory diseases).

Table 1.

Description of sex, age, residence details and risk factors for both groups of patients.

| A. fumigatus group N = 35 | Control group N = 30 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 28 (80%) | 24 (80%) | 1 |

|

Age at admission mean

Median [range] |

67 70 [23–82] |

72 73 [51–82] |

0.06 |

|

Residential area

– Urban – Rural |

18 (51%) 17 (49%) |

20 (67%) 10 (33%) |

0.21 |

|

Chronic respiratory diseases

(mean ± SD) |

0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.07 ± 0.2 | 0.016 |

| Cardiovascular risk (mean ± SD) | 1.4 ± 1 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 0.70 |

|

Immuno-suppression

(mean ± SD) |

0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.6 | 0.28 |

No significant difference was observed for cardiovascular risk and the fact to be immunocompromised (Table 1). Cardiovascular risks listed were diabetes, obesity, hypertension and cardiopathy, 29 patients from the “A. fumigatus group’’ had cardiovascular risks (1 to 4 among the risks listed) and 23 patients from the “control group” had cardiovascular risks (1 to 3 among the risks listed). Immunosuppression risks listed were corticotherapy long course, solid organ transplantation, hemopathy, allograft, solid cancer. Five patients from the “A. fumigatus group’’ had immunosuppression risk factors (1 to 3 among the risks listed) and ten patients of the ‘control group » had immunosuppression risk factors (1 to 2 among the risks listed).

ICU characteristics of the two studied groups did not differ significantly neither on the mean duration of the ICU stay, nor on their gravity scores (Apache II and qSOFA) (Table 2).

Table 2.

ICU characteristics and fungal screening.

| Clinical data | A. fumigatus Group N = 35 | Control Group N = 30 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median ICU stay (in days) [range] | 21 [3–44] | 25 [3–70] | 0.17 |

| Median Apache II Score [range] | 19 [8–38] | 22 [13–33] | 0.14 |

| qSOFA Score ≥ 2 | 15/27 (43%) | 13 (48%) | 0.68 |

| Survival at D90 | 21 (60%) | 19 (63%) | 0.78 |

| Frequency of voriconazole treatment | 14 (40%) | 1 (3%) | < 0.001 |

| Median number of tracheal aspirates analyzed during the ICU stay per patient [range] | 5 [0–11] | 4 [1–17] | 0.83 |

| Median number of broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) analyzed during the ICU stay per patient [range] | 1 [0–4] | 0 [0–5] | 0.45 |

| Median number of antigen galactomanan measurements in serum [range] | 2 [0–7] | 3 [1–10] | 0.04 |

| Number of A. fumigatus qPCR on serum [range] | 2 [0–7] | 3 [1–10] | 0.04 |

No difference in survival was observed neither between both groups of patients (Table 2).

Patients from the “A. fumigatus group’’ were significantly more often treated with voriconazole (40%) than patients included in “the control group” (3%) (P < 0.001, Fisher's exact test, Table 2).

Fungal screening

Both groups of patients were equally frequently screened by respiratory samples (tracheal aspirates and broncho-alveolar lavage) during their ICU stay (Table 2). Fungal biomarkers galactomannan and A. fumigatus qPCR on serum were performed on the same sample. During their ICU stay, patients from the”control group” were screened for fungal biomarkers in serum more frequently than patients from the “A. fumigatus group” (in mean ± SD, respectively, 3.6 ± 2.5 vs 2.5 ± 1.8, P 0.04, Student's t-test; Table 2).

Most patients of the “A. fumigatus group’’ had positive A. fumigatus cultures (N = 34, 97%). Only two had positive A. fumigatus qPCR in serum, and only one had a positive galactomannan antigen in serum.

Based on the criteria proposed by Koelher et al.,6 12 patients from the “A. fumigatus group’’ were retrospectively classified as probable CAPA and 23 patients from the “A. fumigatus group’’ were classified as colonized (Table 3). To be classified as probable CAPA, patients had either a positive culture in BAL, a positive galactomannan on serum or a positive A. fumigatus qPCR in serum (Table 3). Patients with only tracheal aspirates positive for A. fumigatus culture (but not BAL) were considered as colonized with A. fumigatus and not as having probable CAPA (Table 3).

Table 3.

Criteria for probable CAPA/colonization classification for patients included in the “A. fumigatus group”, based on Koelher's classification.6

| Patients | Positive culture in tracheal aspirates | Positive culture in BAL | Positive galactomannan (serum) | Positive A. fumigatus qPCR (serum) | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Probable CAPA |

| P2 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Probable CAPA |

| P3 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Probable CAPA |

| P4 | Yes | yes | no | no | Probable CAPA |

| P5 | Yes | yes | no | no | Probable CAPA |

| P6 | Yes | yes | no | no | Probable CAPA |

| P7 | Yes | yes | no | no | Probable CAPA |

| P8 | Yes | yes | no | no | Probable CAPA |

| P9 | Yes | yes | no | no | Probable CAPA |

| P10 | Yes | yes | no | no | Probable CAPA |

| P11 | Yes | yes | no | yes | Probable CAPA |

| P12 | No | No | yes | yes | Probable CAPA |

| P13 | Yes | No | no | no | Colonized |

| P14 | yes | No | no | no | Colonized |

| P15 | yes | No | no | no | Colonized |

| P16 | yes | No | no | no | Colonized |

| P17 | yes | No | no | no | Colonized |

| P18 | yes | No | no | no | Colonized |

| P19 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P20 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P21 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P22 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P23 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P24 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P25 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P26 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P27 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P28 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P29 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P30 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P31 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P32 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P33 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P34 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

| P35 | yes | no | no | no | Colonized |

Seven patients classified as probable CAPA died (7/12, 58%), seven patients classified as colonized died (7/23, 30%) and eleven non-colonized patients died (11/30, 37%). No relationship was found between the Koelher's classification and the outcome (P 0.15, Fisher's exact test). No difference in terms of residential area (rural vs urban) was observed between probable CAPA patients (5/12, 42%) and colonized patients (12/23, 52%) (P 0.55, Fisher's exact test).

Serology results

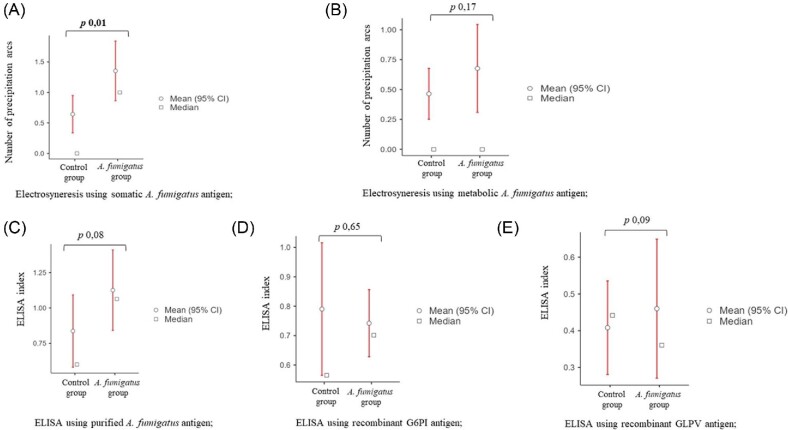

Serology results are presented in Figure 2. Based on electrosyneresis using A. fumigatus somatic antigen, the number of arcs was significantly higher in the “A. fumigatus group” (P 0.01, Welch's t-test) (Figure 2A). In contrast, no significant difference was observed between the “A. fumigatus group” and the “control group” using A. fumigatus metabolic antigen (P 0.17, Welch's t-test) (Figure 2B). No significant difference was found between probable CAPA patients and colonized patients by electrosyneresis, using either the somatic antigen (P 0.4, Welch's t-test) or the metabolic antigen (P 0.8, Welch's t-test).

Figure 2.

Serology results. (A) Significant difference by electrosyneresis between the two groups studied using the somatic A. fumigatus antigen (P 0.01, Welch's t-test). (B) No significant difference by electrosyneresis between the two groups studied using the metabolic A. fumigatus antigen (Welch's t-test). (C) No significant difference by ELISA using the purified A. fumigatus antigen (Welch's t-test). (D) No significant difference by ELISA using the recombinant G6PI antigen (Welch's t test). (E) No significant difference by ELISA using the recombinant GLPV antigen (Welch's t-test).

ELISA tests were performed using either a purified A. fumigatus antigen or using recombinant antigens (G6PI and GLPV).

No significant difference was observed between the “A. fumigatus group” and the “control group” in ELISA using the purified A. fumigatus antigen (P 0.08, Welch's t-test) (Figure 2C).

However, significant higher indices for colonized patients compared to probable CAPA patients were observed (1.3 ± 0.9 vs 0.68 ± 0.4, P 0.02, Welch's t test) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Serology results using in-house ELISA, when considering the groups probable CAPA (n = 12), colonized (n = 23) and non-colonized (n = 30).

No significant difference was observed between the “A. fumigatus group” and the “control group” in ELISA using the recombinant antigen G6PI (p 0.65, Welch's t test) (Figure 2D).

However, significant higher indices for colonized patients compared to probable CAPA patients were observed (0.8 ± 0.4 vs 0.6 ± 0.2, P 0.008, Welch's t-test) (Figure 3).

No significant difference was observed between the “A. fumigatus group” and the “control group” in ELISA using the recombinant antigen GLPV (P 0.09, Welch's t-test) (Figure 2E).

No difference in indices was observed between colonized patients and probable CAPA patients (1.1 ± 0.9 vs 1.2 ± 0.9, P 0.9, Welch's t-test) (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our study aimed at investigating retrospectively if A. fumigatus precipitin detection could have been useful in deciding whether or not to use antifungal treatment for SARS-Cov-2 ICU patients who present positive respiratory samples in culture for A. fumigatus. Indeed, since the prevalence of COVID Associated Pulmonary Aspergillosis (CAPA) may increase with the deterioration of respiratory conditions, authors have recently emphasized the importance of acting quickly: the sooner the antifungal prescription based on the first positive culture/test, the better.4–6

Precipitin assays targeting A. fumigatus allow the detection of serum-specific immunoglobulin which is merely indicative of previous exposure and immunologic sensitization, and does not prove infection.7 We observed a difference in positivity according to the nature of the A. fumigatus antigen used for electrosyneresis, which can be explained by the protein composition of each antigen: somatic antigen is obtained from the mycelial culture of A. fumigatus while metabolic antigen is obtained by filtration of A. fumigatus liquid culture media. So, the metabolic antigen contains proteins produced in the culture media by A. fumigatus and not directly the proteins composing A. fumigatus mycelium and spores. Precipitation reactions remain the “gold standard” to highlight macroscopically the precipitation arcs that result from the antigen-antibody reaction.8 Most probably, these precipitating antibodies are not as well detected by ELISA method than by precipitation techniques. ELISA tests did not highlight significant differences between the two main groups of patients (“A. fumigatus group” vs “control group”), however, ELISA tests using A. fumigatus purified antigen and the recombinant G6PI antigen showed significantly higher indices for patients classified retrospectively as colonized compared to those classified retrospectively as probable CAPA. This result was not expected and may be related to the small size of the subgroup of patients classified retrospectively as probable CAPA (n = 12).

Before the study, we hypothesized that the rural/urban habitation of SARS-Cov-2 ICU patients could have played a role on their exposure to molds at home and their probability to arrive in the ICU colonized with A. fumigatus. The environmental exposure plays indeed a key role in HP investigations7,8 and also in the risk to develop invasive aspergillosis.13 However, no significant difference was observed between residential area between the two groups of patients, and also between probable CAPA patients and colonized patients.

One could consider that the fact that the patients from the”control group” were randomly chosen and not matched to the patients from the “A. fumigatus group” represents a bias. However, the descriptive analysis showed that both groups were similar in terms of age and sex (Table 1) and in terms of ICU characteristics (Table 2).

The management of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia has evolved over time, and a regimen of dexamethasone for 10 days is now recommended in severe cases.14 A SARS-CoV-2 ICU patient receiving dexamethasone while showing evidence of A. fumigatus colonization (i.e. positive culture in tracheal aspirate) and of A. fumigatus sensitization (i.e. positive precipitin assay) could be a possible candidate for CAPA, as the steroids may create a favorable local environment for A. fumigatus growth in situ. When a patient had a positive result in culture for A. fumigatus in BAL, physicians rapidly treated the patient with voriconazole, which was illustrated by the high frequency of treated patients in the “A. fumigatus group” (40%, Table 2) compared to the “control group”(3%). However, when SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients had no positive result for A. fumigatus detection, the screening in serum remained sustained, as illustrated by the high rate of galactomannan and A. fumigatus qPCR measurements in serum performed in the “control group” (Table 2). Fungal biomarkers were rarely positive, <10% in our series, which was also the case in other reports.15 There is thus a need for additional tools, and serology assays could be appropriate candidates.

Conclusion

Our study has demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients with a positive marker for Aspergillus species detection more often presented precipitins towards the somatic A. fumigatus antigen. Serology assays could thus be an additional tool to manage SARS-CoV-2 ICU patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pamela Albert for her editorial assistance.

We thank Pfizer for supporting this study.

Contributor Information

A P Bellanger, Department of Parasitology-Mycology, University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; Referent Laboratory of Medical Biology for the serological diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (LBMR PHS), University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; CNRS-University of Franche-Comte/ UMR 6249 Chrono-environment, Besançon, Besancon, France.

S Lallemand, Department of Parasitology-Mycology, University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France.

A Tumasyan Horikian, Department of Parasitology-Mycology, University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France.

J C Navellou, Intensive Medical Care Unit, Regional Hospital of Besancon, Besancon, France.

C Barrera, Department of Parasitology-Mycology, University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; Referent Laboratory of Medical Biology for the serological diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (LBMR PHS), University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; CNRS-University of Franche-Comte/ UMR 6249 Chrono-environment, Besançon, Besancon, France.

A Rouzet, Department of Parasitology-Mycology, University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; Referent Laboratory of Medical Biology for the serological diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (LBMR PHS), University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; CNRS-University of Franche-Comte/ UMR 6249 Chrono-environment, Besançon, Besancon, France.

E Scherer, Department of Parasitology-Mycology, University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; Referent Laboratory of Medical Biology for the serological diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (LBMR PHS), University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; CNRS-University of Franche-Comte/ UMR 6249 Chrono-environment, Besançon, Besancon, France.

G Reboux, Department of Parasitology-Mycology, University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; Referent Laboratory of Medical Biology for the serological diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (LBMR PHS), University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France.

G Piton, Intensive Medical Care Unit, Regional Hospital of Besancon, Besancon, France.

L Millon, Department of Parasitology-Mycology, University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; Referent Laboratory of Medical Biology for the serological diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis (LBMR PHS), University Hospital of Besançon, Besancon, France; CNRS-University of Franche-Comte/ UMR 6249 Chrono-environment, Besançon, Besancon, France.

Declaration of interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Song YG, Song HS.. COVID-19, a clinical syndrome manifesting as hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Infect Chemother. 2020; 52: 110–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vuitton DA, Vuitton L, Seillès E, Galanaud P.. A plea for the pathogenic role of immune complexes in severe Covid-19. Clin Immunol. 2020; 217: 108493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Selman M, Pardo A, King TE Jr.. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012; 186: 314–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alanio A, Dellière S, Fodil S, Bretagne S, Mégarbane B.. Prevalence of putative invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Lancet Respir Med. 2020; 8: e48–e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gangneux JP, Dannaoui E, Fekkar Aet al. Fungal infections in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 during the first wave: the French multicentre MYCOVID study. Lancet Respir Med. 2022; 10: 180–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koehler P, Bassetti M, Chakrabarti Aet al. Defining and managing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: the 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021; 21: e149–e162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johannson KA, Barnes H, Bellanger APet al. Exposure Assessment Tools for Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020; 17: 1501–1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bellanger AP, Reboux G, Rouzet Aet al. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a new strategy for serodiagnosis and environmental surveys. Respir Med. 2019; 150: 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fenoglio CM, Reboux G, Sudre Bet al. Diagnostic value of serum precipitins to mould antigens in active hypersensitivity pneumonitis. European Respiratory J. 2007; 29: 706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Millon L, Roussel S, Rognon Bet al. Aspergillus species recombinant antigens for serodiagnosis of farmer's lung disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012; 130: 803–805e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barrera C, Richaud-Thiriez B, Rocchi Set al. New commercially available IgG kits and time-resolved fluorometric IgE assay for diagnosis of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in patients with cystic fibrosis. Clinical Vaccine Immunol. 2015; 23: 196–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bellanger AP, Millon L, Berceanu Aet al. Combining Aspergillus mitochondrial and ribosomal QPCR, in addition to galactomannan assay, for early diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in hematology patients. Med Mycol. 2015; 53: 760–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rocchi S, Reboux G, Larosa Fet al. Evaluation of invasive aspergillosis risk of immunocompromised patients alternatively hospitalized in hematology intensive care unit and at home. Indoor Air. 2014; 24: 652–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JRet al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19.2021. N Engl J Med. 2021; 384: 693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rutsaert L, Steinfort N, Van Hunsel Tet al. COVID-19-associated invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Ann Intensive Care. 2020; 10: 71–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]