Abstract

Background

Patterns of shedding replication-competent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in severe or critical COVID-19 are not well characterized. We investigated the duration of replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 shedding in upper and lower airway specimens from patients with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Methods

We enrolled patients with active or recent severe or critical COVID-19 who were admitted to a tertiary care hospital intensive care unit (ICU) or long-term acute care hospital (LTACH) because of COVID-19. Respiratory specimens were collected at predefined intervals and tested for SARS-CoV-2 using viral culture and reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). Clinical and epidemiologic metadata were reviewed.

Results

We collected 529 respiratory specimens from 78 patients. Replication-competent virus was detected in 4 of 11 (36.3%) immunocompromised patients up to 45 days after symptom onset and in 1 of 67 (1.5%) immunocompetent patients 10 days after symptom onset (P = .001). All culture-positive patients were in the ICU cohort and had persistent or recurrent symptoms of COVID-19. Median time from symptom onset to first specimen collection was 15 days (range, 6–45) for ICU patients and 58.5 days (range, 34–139) for LTACH patients. SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in 40 of 50 (80%) ICU patients and 7 of 28 (25%) LTACH patients.

Conclusions

Immunocompromise and persistent or recurrent symptoms were associated with shedding of replication-competent SARS-CoV-2, supporting the need for improving respiratory symptoms in addition to time as criteria for discontinuation of transmission-based precautions. Our results suggest that the period of potential infectiousness among immunocompetent patients with severe or critical COVID-19 may be similar to that reported for patients with milder disease.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, viral culture, virus shedding, intensive care, long-term acute care hospital

Among patients with severe or critical COVID-19, replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 was detected in respiratory specimens of 4/11 (36%) immunocompromised patients up to 45 days after symptom onset and 1/67 (1.5%) immunocompetent patients up to 10 days after symptom onset.

Shedding of replication-competent virus is a key determinant of risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission [1–3]. Respiratory isolation precautions are recommended while patients are shedding replication-competent virus, but the duration of shedding in patients with severe or critical coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [4] is not well characterized [1, 5, 6]. Based on limited data, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that patients with severe or critical COVID-19 remain in respiratory isolation for 20 days after symptom onset [1]. Patients with COVID-19 with mild or moderate disease have been found to shed replication-competent virus for a shorter period, and respiratory isolation is recommended for a minimum of 10 days [1].

Survivors of the acute phase of severe or critical COVID-19 who are initially treated in a short-term acute care hospital intensive care unit (ICU) may require continued care at a long-term acute care hospital (LTACH). These healthcare facilities are designed to treat patients who require long-term respiratory support and ventilator weans [7, 8]. Maintaining LTACH patients on respiratory isolation precautions may interfere with rehabilitation activities that occur in common areas, such as physical therapy suites. It is therefore important to have accurate estimates of the length of time that patients with COVID-19 with severe or critical illness shed replication-competent virus in order to ensure that they receive optimal treatment while protecting other patients and healthcare personnel from potential exposure.

Our study has 3 aims: (1) to determine the length of time that replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 can be isolated in culture from upper and lower respiratory tract specimens of patients with severe or critical COVID-19, (2) to determine whether replication-competent virus is shed longer in the lower versus the upper respiratory tract, and (3) to assess risk factors for shedding of replication-competent virus.

METHODS

Population and Settings

We conducted the study at Rush University Medical Center, a 664-bed tertiary care academic hospital in Chicago, Illinois, and 2 LTACHs: RML Specialty Hospital in Chicago (87 beds) and Hinsdale (115 beds), Illinois. Patient inclusion criteria included the following: (1) age 18 years or older, (2) positive result for SARS-CoV-2 by a nucleic acid amplification test, and (3) severe or critical COVID-19 [4], defined as admission to an ICU and requiring high-flow oxygen therapy, noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) at some point during treatment of COVID-19. If no specimens were collected from an enrolled patient, the patient was excluded from analysis. We enrolled patients from 11 August 2020 to 4 February 2021 when variants containing the D614G mutation in the spike protein gene were predominant in our region and before variants of concern were detected [9, 10]. We collected information including the following: demographics, date of symptom onset, hospital admission date, ICU admission date, highest mode of oxygen supplementation and respiratory support, chest imaging, disease severity according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria [4], results of SARS-CoV-2 reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) clinical diagnostic testing, comorbidities including immunocompromising conditions [11], receipt of antiviral or immunomodulating therapy, and clinical outcomes. Clinical and epidemiologic metadata were obtained through patient or family interview, electronic medical record review, and the Illinois' National Electronic Disease Surveillance System to confirm SARS-CoV-2 test results and date of symptom onset for events outside our study sites [12].

Collection of Respiratory Specimens

To maximize the precision of our estimate of duration of shedding of replication-competent virus, we collected respiratory specimens every other day from the ICU cohort during the ICU stay, since this time corresponded to the period during which earlier observational studies had reported virus clearance [13–15]. For upper respiratory tract specimens, study staff collected midturbinate swab specimens using Copan FLOQSwabs (Copan, Murrieta, CA). For lower respiratory tract specimens, respiratory therapists collected endotracheal aspirates from patients who were intubated.

In order to estimate the longest duration of virus shedding among patients with prolonged critical illness, we collected paired midturbinate swab and tracheal aspirate specimens for 3 consecutive days from patients in the LTACH cohort, which included patients who were typically much longer than 20 days past COVID-19 symptom onset. The LTACH nursing staff collected midturbinate swab specimens and respiratory therapists collected tracheal aspirate specimens.

Midturbinate swab specimens were placed immediately into 3-mL sterile Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline. Endotracheal/tracheal aspirate specimens were collected into sterile sputum traps. Specimens were transported at 2–8°C to the Rush laboratory, where the specimens were aliquoted into 1-mL volumes and stored at −80°C for a median of 149 days (range, 102–306 days) until viral culture and RT-qPCR testing.

SARS-CoV-2 Culture and RT-qPCR

A single aliquot was thawed and tested for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 by culture and RT-qPCR. Cultures were tested in a blinded manner; RT-qPCR results were matched with culture results after testing was completed and patient identifiers were not revealed during the testing process.

Specimens were cultured on Vero E6 cells (ATCC CRL-1586) with minimum essential medium + 1 mM l-glutamine + 1 mM sodium pyruvate + 10% fetal bovine serum + 1× penicillin-streptomycin/amphotericin B and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment with humidity under biosafety level-3 conditions [16]. We incorporated a passage process on day 4 of incubation by transferring 100 μL of culture medium supernatant to a newly prepared plate containing fresh Vero E6 cells in 1:10 dilution. On day 7, cytopathic effect (CPE) on Vero E6 cells was assessed in primary and passage plates and culture supernatant was tested for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using a modified version of the CDC RT-qPCR assay, as described previously [17, 18]. Cultures were defined as positive for replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 if compatible CPE was observed in both primary and passage plates and supernatant from the passage plate was positive for the SARS-CoV-2 N1 gene by RT-qPCR (cycle threshold [Ct] value <40). For specimens with bacterial outgrowth and detectable SARS-CoV-2 by RT-qPCR in the primary specimen, we repeated viral culture with the addition of gentamicin. If bacterial outgrowth was still noted on repeat culture of a new frozen aliquot, results were defined as invalid as the bacterial outgrowth inhibited visualization of CPE. Details of the viral culture procedure can be found in the Supplementary material.

Specimens were tested for SARS-CoV-2 RNA by the RealTime SARS-CoV-2 assay performed on the Abbott m2000 platform (Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL), as described previously [17]. Cycle number (Cn) values reported in this study were adjusted for the 10 “hidden” cycles masked by the software used on the Abbott m2000 to facilitate comparison to Ct values generated by other SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR assays. The Cn values were converted to log10 RNA genome equivalents (ge)/mL using an internally validated calibration curve developed from testing of serial dilutions of purified genomic RNA from a reference SARS-CoV-2 isolate (USA-WA1/2020, NR-52285, lot no. 70035629; BEI Resources, Manassas, VA) [17].

SARS-CoV-2 Whole-Genome Sequencing

Total nucleic acid was extracted from 100-µL aliquots of the same aliquot as used for culture and RT-qPCR using the Maxwell RSC 48 automated extraction robot (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the Maxwell RSC Viral Total Nucleic Acid Purification Kit (Promega) protocol, with an elution volume of 50 µL. RNA was converted into cDNA using the High Capacity Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). Multi-amplicon next-generation-sequencing libraries were generated in 2-step PCR reactions from cDNA, using the low-input recommendations of the Swift Normalase Amplicon SARS-CoV-2 gene panel (Swift Biosciences, Ann Arbor, MI). Indexed libraries were pooled in equal volumes (3 µL) for quality-control sequencing. Percent mapping to a SARS-CoV-2 reference sequence (MN908947) and total reads were used to calculate volumes for repooling with a target of 500 000 reads per sample. The repooled library was sequenced by NovaSeq6000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Data generated were trimmed using Cutadapt [19], and then imported into CLC Genomics for processing (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). Trimmed reads were mapped to a reference sequence (MN908947).

Statistical Analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Comparison of viral load levels between SARS-CoV-2 culture-positive specimens and those of culture-negative specimens was accomplished with a repeated-measures model. A generalized linear mixed model was used to examine the difference between midturbinate and endotracheal/tracheal aspirate specimens with respect to culture positivity and bacterial contamination (binary endpoints). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Details of the statistical analysis can be found in the Supplementary material.

Human Subjects Research Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Rush University Medical Center and RML Specialty Hospitals, respectively. Written informed consent was required. Patients’ designated surrogates provided informed consent if patients were incapacitated.

RESULTS

Enrollment and Patient Characteristics

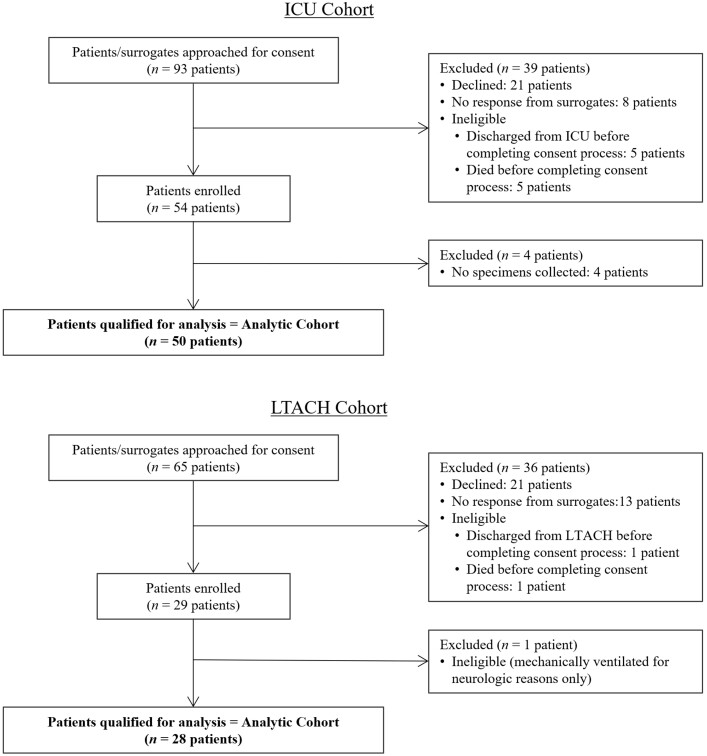

We approached 93 ICU patients and enrolled 50 patients in the ICU cohort. We approached 65 LTACH patients and enrolled 28 patients in the LTACH cohort (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1, stratified by ICU or LTACH setting. Overall, demographics and clinical conditions were typical of those seen in patients with COVID-19 in our region during this time. A minority of patients (9 in the ICU cohort and 2 in the LTACH cohort) were immunocompromised, of whom 5 ICU patients were subcategorized as severely immunocompromised [11]. Most patients (62% in the ICU and 100% in the LTACH cohorts) were categorized as critical COVID-19. Among 19 ICU patients with severe but not critical COVID-19, 16 required high-flow oxygen therapy and 3 required noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation. A majority of patients received remdesivir (92% ICU and 61% LTACH) and dexamethasone (98% ICU and 68% LTACH), while only a minority received tocilizumab (0% ICU and 25% LTACH) (Table 1). None of the patients in the ICU and LTACH cohorts had received a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2.

Figure 1.

ICU and LTACH enrollment. Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LTACH, long-term acute care hospital.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Variable | ICU (n = 50) | LTACH (n = 28) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), years | 60.5 (26–91) | 62.5 (42–86) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 35 (70) | 17 (61) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic | 32 (64) | 10 (36) |

| White non-Hispanic | 11 (22) | 12 (43) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 4 (8) | 5 (18) |

| Asian non-Hispanic | 3 (6) | 1 (4) |

| Disease severity,a n (%) | ||

| Critical | 31 (62) | 28 (100) |

| ECMO | 3 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Mechanical ventilation only | 28 (56) | 28 (100) |

| Severe | 19 (38) | 0 (0) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 36 (72) | 24 (86) |

| Pulmonary | 6 (12) | 6 (21) |

| Moderate or severe renal disease (eGFR <60 mL/minute) | 10 (20) | 3 (11) |

| Hemodialysis | 2 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Diabetes | 21 (42) | 17 (61) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) | 30 (60) | 15 (54) |

| Severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) | 8 (16) | 7 (25) |

| Immunocompromising conditionb | 9 (18) | 2 (7) |

| Severec | 5 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Nonsevered | 4 (1) | 2 (7) |

| COVID-19 antiviral and immunomodulatory therapy, n (%) | ||

| Remdesivir | 46 (92) | 17 (61) |

| Dexamethasonee | 49 (98) | 19 (68) |

| Tocilizumab | 0 (0) | 7 (25) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ICU, intensive care unit; LTACH, long-term acute care hospital; SOT, solid-organ transplant.

According to the National Institutes of Health criteria [4]. Critical disease was defined as respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiple organ dysfunction. Severe disease was defined as peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) <94% on room air at sea level, ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) <300 mmHg, or lung infiltrates >50%.

Fraaij et al [11].

Defined as allogeneic HSCT <12 months, GVHD after allogeneic HSCT, HIV-positive with CD4+ T-cell count <200 cells/µL, chemotherapy with >7 days neutropenia, lung transplant, SOT other than lung with induction therapy <6 months, SOT other than lung >1 year and rejection <3 months, use of immunomodulating biologicals, or daily corticosteroid dosage (based on prednisone) of >30 mg for >14 days.

Defined as maintenance chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies, chemotherapy for solid tumors, autologous HSCT, >1 year after SOT and no rejection, HIV-positive with undetectable viral load and CD4+ T-cell count >200 cells/µL, methotrexate use for autoimmune disease, daily corticosteroid (based on prednisone) dosage ≤30 mg for ≤14 days, other possible immune deficiencies (ie, untreated autoimmune disease, use of immunosuppressants other than immunomodulating biologicals).

Six milligrams per day for 10 days [20].

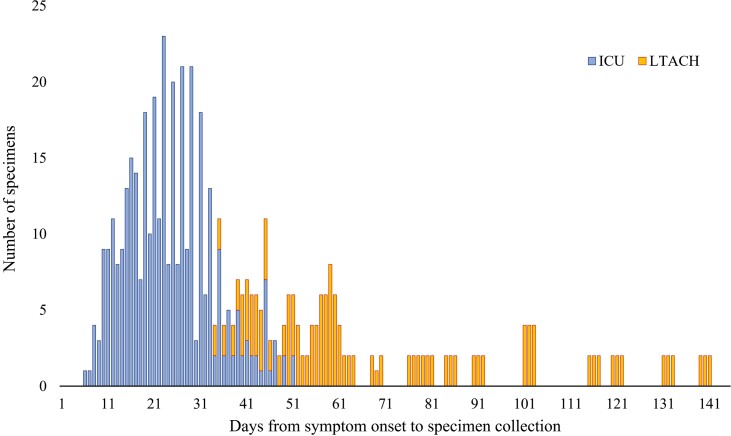

A total of 529 respiratory specimens were collected: 362 from ICU patients and 167 from LTACH patients (Table 2). The median time from symptom onset to collection of the first specimen was 21 days for the combined ICU and LTACH cohort (IQR, 12–50 days; range, 6–139 days). Most specimens were collected on days 10 to 60 from symptom onset (445 specimens, 84%) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Specimen Characteristics, SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR, and Viral Culture Results

| ICU (n = 50) | LTACH (n = 28) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of specimens, n (median number of specimens per patient) | 362 (5.5) | 167 (6) |

| Midturbinate specimens | 244 (4) | 84 (3) |

| Endotracheal/tracheal aspirate specimens | 118a (4) | 83 (3) |

| Median (range) days from symptom onset to first specimen collection date | 15 (6–45) | 58.5 (34–139) |

| Number of patients with culture-positiveb specimens | 5 | 0 |

| Median number of specimens per patient with a positive culture result,c n (range) | 2 (1–4) | 0 |

| Midturbinate specimens | 2 (1–2) | 0 |

| Endotracheal/tracheal aspirate specimens | 1 (0–2) | 0 |

| Number of patients with SARS-CoV-2 RNA detected by RT-qPCR | 40 | 7 |

| Median number of specimens per patient with a positive RT-qPCR result, n (range) | 4 (1–19) | 1 (1–5) |

| Midturbinate specimens | 3 (1–10) | 1 (0–3) |

| Endotracheal/tracheal aspirate specimens | 1 (0–9) | 0 (0–2) |

Abbreviations: CPE, cytopathic effect; ICU, intensive care unit; LTACH, long-term acute care hospital; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Median number of specimens collected from the 27 patients who had at least 1 endotracheal specimen collected.

Defined as presence of compatible CPE in both primary and passage plates plus positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR in post-passage viral culture supernatant.

Calculated only for patients with at least 1 positive viral culture.

Figure 2.

Distribution of days from symptom onset to study specimen collection. Blue bars represent specimens from ICU cohort and orange bars represent specimens from LTACH cohort. Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LTACH, long-term acute care hospital.

Viral Culture and Risk Factors for Detection of Replication-Competent Virus

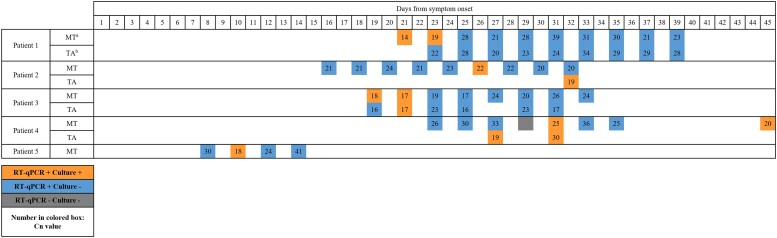

Overall, specimens from 5 (6.4%) patients grew replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 from 12 of 529 (2.3%) respiratory specimens (median [range] of 2 [1–4] culture-positive specimens per culture-positive patient) (Table 2). All culture-positive patients were in the ICU cohort and had persistent or recurrent symptoms of COVID-19. Overall, 5 of 50 (10%) ICU patients grew replication-competent virus from 1 or more respiratory specimen. Replication-competent virus was detected in 4 of 11 (36%) immunocompromised patients (3 of whom were classified as having severe immunocompromise) up to 45 days after symptom onset, and in 1 of 67 (1.5%) immunocompetent patients 10 days after symptom onset (P = .001) (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Table 3.

Study Participants With Positive SARS-CoV-2 Culture

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) and sex | 68, Female | 68, Male | 50, Male | 55, Female | 61, Male |

| Immunocompromising conditiona | Severe

|

Severe

|

Nonsevere

|

Severe

|

None |

| COVID-19 antiviral and immunomodulatory therapy | Remdesivir, dexamethasone | Remdesivir, dexamethasone | Remdesivir, dexamethasone | Remdesivir, dexamethasone | Remdesivir, dexamethasone |

| Days from symptom onset | |||||

| Hospital admission | 6 | 12 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| ICU admission | 17 | 15 | 13 | 7 | 4 |

| Positive culture(s) | 21, 23 | 26, 32 | 19, 21 | 27, 31, 45 | 10 |

| Negative cultures | 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37, 39 | 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 28, 30 | 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33 | 23, 25, 29, 33, 35 | 8, 12, 14 |

| Anti-N IgG | Negative: 19 | Not available | Not available | Negative: 17, 36, 57 | Not available |

| Outcome | 54 (died) | 33 (died) | 37 (died) | 83 (discharged to LTACH) | 17 (discharged to home) |

| Comments | Patient’s initial specimens grew SARS-CoV-2 in culture, but subsequent specimens were culture negative | 9 upper respiratory tract specimens had similar Cn values (range, 20–24) but only 1 specimen collected on day 26 grew replication-competent virus. A lower respiratory tract specimen collected on day 32 from symptom onset also grew replication-competent SARS-CoV-2. | Patient had initial specimens with positive viral culture then subsequent specimens turned negative for culture. | Patient had recurrence of detectable replication-competent virus 45 days after symptom onset after return to the ICU with worsening respiratory and systemic symptoms. This was preceded by clinical recovery and specimens with negative viral culture. An alternative explanation for clinical deterioration was not identified. Results of whole-genome sequencing of this patient’s isolates were consistent with a single SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than new or superinfection with SARS-CoV-2. Patient declined further specimen collection. |

Abbreviations: CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; Cn, cycle number; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, intensive care unit; IgG, immunoglobulin G; LTACH, long-term acute care hospital; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; s/p, status post.

Fraaij et al [11].

Figure 3.

Cycle number (Cn) values and culture positivity over time within patients with at least 1 positive culture. Orange boxes represents specimens with detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA and detectable replication-competent virus. Blue boxes represent specimens with detectable SARS-CoV-2 RNA and negative viral culture. Gray boxes represent specimens with negative RT-qPCR results and negative viral culture. Numbers in colored boxes represent Cn values from the SARS-CoV-2 Abbott m2000 Assay. Abbreviations: MT, midturbinate specimen; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TA, endotracheal aspirate specimen.

One of the patients with severe immunocompromise (Patient 4), who had SARS-CoV-2 detected longest after symptom onset was analyzed further. This patient had recurrence of detectable replication-competent virus 45 days after symptom onset after return to the ICU with worsening respiratory and systemic symptoms. An alternative explanation for the clinical deterioration was not identified; routine microbiologic testing was negative except for a diagnostic nasopharyngeal swab specimen positive for SARS-CoV-2 by RT-qPCR. Whole-genome sequencing of this patient’s isolates on days 23, 27, 31, 35, and 45 after symptom onset identified the D614G lineage with identical consensus sequences and minor variations over time at positions 9438 and 11962, consistent with viral evolution during a prolonged infection (Supplementary Figure 1). The patient had undetectable serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) to SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein on days 17, 36, and 57 after symptom onset; this testing was done as part of the patient’s routine clinical care.

Detection of Replication-Competent Virus in Midturbinate vs Endotracheal/Tracheal Aspirate Cultures

Replication-competent virus was detected in 8 midturbinate and 4 endotracheal/tracheal aspirate specimens. No difference in the probability of detection of replication-competent virus was identified between the 2 specimen types (P = .78) when tested in the mixed model (odds ratio [OR], .82; 95% confidence interval [CI], .19–3.44). Of note, bacterial outgrowth was observed in viral culture of 17 midturbinate and 27 endotracheal/tracheal aspirate specimens; in such cases, viral culture results were reported as being invalid due to the inability to visualize CPE, although none of the culture supernatants of these specimens were RT-qPCR positive. Midturbinate specimens had less bacterial contamination compared with endotracheal/tracheal aspirate specimens (OR, .26; 95% CI, .11–.64; P = .004). Endotracheal/tracheal aspirate specimens were often mucoid and contained large amounts of cellular elements and debris, which inhibited the RT-qPCR reaction in 38% (76 of 201) of specimens. Inhibition was not observed in midturbinate specimens.

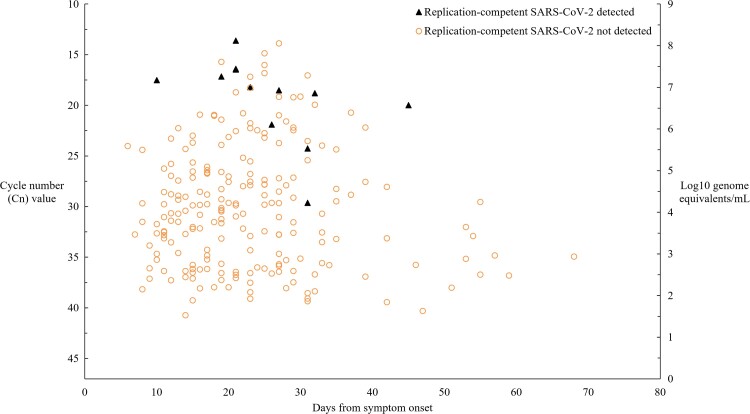

Relation Between SARS-CoV-2 Culture and RT-qPCR–Estimated SARS-CoV-2 RNA Concentration

To assess the relation between the detection of replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV-2 estimated genomic RNA concentration, we evaluated the 221 respiratory specimens with positive RT-qPCR results and their viral culture results (Figure 4). After adjusting for days since symptom onset and accounting for within-patient correlation of observations, estimated mean values of SARS-CoV-2 log10 RNA were 6.9 ge/mL for culture-positive specimens and 4.3 ge/mL for culture-negative specimens (P = .003).

Figure 4.

Relation of detection of replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 and estimated concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA to time from symptom onset. Among a total of 529 respiratory specimens, we evaluated 221 specimens that yielded positive RT-qPCR results and interpretable viral culture results (positive or negative) to assess the relation. Genomic RNA concentration was estimated using an internally validated calibration curve: Cn = −1.786 ln(viral load in log10 RNA ge/mL) + 37.416. See Methods for details. Not shown is a specimen collected on day 133 after symptom onset with Cn value 31 and negative SARS-CoV-2 culture result. Abbreviations: Cn, cycle number; ge, genome equivalents; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription–quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

DISCUSSION

In this longitudinal, observational cohort study of 78 ICU and LTACH patients with severe or critical COVID-19, replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 was detected in only 5 patients (6.4%), 4 of whom were immunocompromised (3 patients were severely immunocompromised), all of whom had persistent or recurrent respiratory symptoms, and all of whom were in the ICU cohort. Only 4 patients (all immunocompromised) had detectable replication-competent virus for longer than 10 days after symptom onset, suggesting that severe or critical COVID-19 alone may not be a strong risk factor for prolonged virus shedding beyond 10 days. In contrast to the low recovery rate of replication-competent SARS-CoV-2, 80% of patients in the ICU cohort and 25% of patients in the LTACH cohort had SARS-CoV-2 RNA detected in 1 or more samples by RT-qPCR. These results suggest that positive RT-qPCR results are a poor surrogate for the presence of replication-competent virus in patients with severe or critical COVID-19. They also suggest that patients who are sufficiently recovered from COVID-19 to be able to be transferred to an LTACH are unlikely to be shedding infectious virus.

Immunocompromising conditions in our patient cohorts included having a history of stem cell transplant, solid-organ transplant, and receipt of immunomodulating biological agents. Two of five study patients with replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 anti-N IgG at day 19 of symptom onset or later, which is consistent with the previously described association between undetectable SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and prolonged infectious virus shedding among hospitalized COVID-19 patients [13, 21]. Importantly, all 4 immunocompromised patients with detectable replication-competent virus had persistent or recurrent symptoms that indicated the need to continue transmission-based precautions during their clinical care. One severely immunocompromised patient developed apparent relapsed COVID-19 at 45 days after symptom onset and after a period of clinical recovery. Results of whole-genome sequencing of this patient’s isolates were consistent with a single SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than new or superinfection with a different SARS-CoV-2. The potential for prolonged viral replication and shedding among immunocompromised patients is supported by multiple case studies [22–25].

Like other investigators, we found that positive RT-qPCR results were a poor indicator of the presence of replication-competent virus [13, 14], although specimens that grew SARS-CoV-2 in culture had significantly higher mean estimated SARS-CoV-2 genomic RNA concentrations than specimens that were culture negative. Other studies have reported that respiratory specimens with a high concentration of SARS-CoV-2 virus, as estimated by RT-qPCR, have a greater likelihood of harboring replication-competent virus [26–29].

Our study utilized a stringent culture assay that was highly specific for the presence of replication-competent SARS-CoV-2, requiring molecular confirmation of virus detection on a passage plate. Other studies detecting live SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding in ICU patients have utilized various assays, including testing approaches that may be less specific for replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 (eg, requiring only visual confirmation, without molecular confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 presence). Other factors that may influence the frequency of detection of SARS-CoV-2 in respiratory specimens include differences in the population tested (eg, time from symptom onset, immunocompromising conditions, or receipt of immunocompromising medications), specimen type, and culture procedure [13, 30, 31].

Our study has limitations. First, our study was conducted before SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern were circulating in our region, so our results may not be generalizable to infections caused by recent variants [32, 33]. Second, lower respiratory tract specimens were often mucoid and contained large amounts of cellular elements and debris, which appeared to inhibit the RT-qPCR reaction and viral culture, and resulted in bacterial outgrowth that precluded reading CPE. Thus, we were unable to test whether the duration of SARS-CoV-2 shedding from the lower respiratory tract was different from that of the upper respiratory tract, as suggested in prior studies [34–37]. Third, our respiratory specimens underwent 1 freeze–thaw cycle before viral culture and RT-qPCR. Using control SARS-CoV-2 stock with known virus concentration, we estimated a 1-log10 decrease in infectious titer after a single freeze–thaw event (data not shown). Fourth, we collected midturbinate swab specimens in 3 mL of transport medium, thus diluting the specimen and potentially reducing sensitivity. Fifth, we estimated the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using a standard curve developed with a commercially available, full-genome SARS-CoV-2 whose concentration was estimated by digital droplet PCR testing; the World Health Organization international standard for SARS-CoV-2 RNA was not available when we began our study [38]. Estimated virus concentration determinations from our study may not be generalizable to other testing platforms or laboratories.

Our study also has strengths. We collected respiratory specimens prospectively at predetermined times using standardized methods. We had access to multiple databases including the Illinois' National Electronic Disease Surveillance System; thus, we used more complete data for the determination of time of symptom onset. We studied a robust number of patients and specimens enriched for the disease time period (ie, days >10 after onset of symptoms) during which other retrospective and cross-sectional studies have reported virus clearance. Last, we enrolled in the LTACH setting, in which data on virus clearance among recovering patients are particularly sparse, and where understanding transmission risk is important to optimize care of patients recovering from COVID-19 and to protect other LTACH patients who are typically at high risk of developing severe or critical COVID-19.

In summary, we found that patients with severe or critical COVID-19 shed replication-competent SARS-CoV-2 rarely unless they had immunocompromising conditions and persistent or recurrent respiratory symptoms. Guidelines for discontinuation of transmission-based precautions for COVID-19 in healthcare settings should continue to include a criterion for improving respiratory symptoms, in addition to time-based criteria [1]. Our results suggest that the period of potential infectiousness among immunocompetent patients with severe or critical COVID-19 may be similar to that reported for patients with milder disease.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the patients and staff of Rush University Medical Center and RML Specialty Hospitals for their participation. They thank Laura Furtado, Hannah Barbian, Stefan Green (Rush University Medical Center), Xueting Qui (Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health), and Dan Lu (Chan Zuckerberg Initiative) for whole-genome sequencing and analysis; Mary Carl Froilan, Jinal Makhija, and Khaled Aboushaala (Rush University Medical Center) for their role in consenting study patients and collecting specimens; and Christine Fukuda (Rush University Medical Center) for data analysis support. The authors also thank Sangeetha Baskaran, Pamela B. Bell, and Jennifer Lindsley (Rush University Medical Center) for their role in specimen processing and diagnostic laboratory testing.

Financial support. This work was supported in part by a COVID-19 supplemental grant to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cooperative agreement U54 CK000481-05-02. D.K. is a recipient of Leadership in Epidemiology, Antimicrobial stewardship, Public health (LEAP) fellowship training award sponsored by SHEA, IDSA, PIDS and received training grant from IDSA.

Potential conflicts of interest. M. K. H. is a member of a clinical adjudication panel for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine under development by Sanofi; reports support unrelated to this work from the CDC; and is 2021 President of the SHEA Board of Directors, Chair of IDSA Rapid Guidelines Committee for COVID-19 Diagnosis, and Chair of IDSA Diagnostics Committee. N. M. M. reports a research contract unrelated to this work and paid to his institution from Cepheid, Inc; honoraria for a continuing education lecture from South Central Association for Clinical Microbiology, honoraria for book chapters from Elsevier, honoraria for a continuing education lecture from the American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science; and a position as President-Elect of the Illinois Society for Microbiology. All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Do Young Kim, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Chicago Department of Public Health, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Michael Y Lin, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Cheryl Jennings, Rush Research Cores, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Haiying Li, Department of Pathology, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Jae Hyung Jung, Department of Internal Medicine, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Nicholas M Moore, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Department of Pathology, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA; Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Isaac Ghinai, Chicago Department of Public Health, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Stephanie R Black, Chicago Department of Public Health, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Daniel J Zaccaro, Social & Scientific Systems, Inc, a DLH Holdings Corporation, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

John Brofman, RML Specialty Hospital, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Mary K Hayden, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Duration of isolation and precautions for adults with COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2020; 2019:1–7. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/duration-isolation.html. Accessed 29 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Guidance for discharge and ending of isolation of people with COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Guidance-for-discharge-and-ending-of-isolation-of-people-with-COVID-19.pdf. Accessed 29 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization . COVID-19 clinical management: living guidance. 2021. Available at:https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/338882. Accessed 29 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information . NIH coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment guidelines. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570371/. Accessed 24 March 2022.

- 5. Fontana LM, Villamagna AH, Sikka MK, et al. Understanding viral shedding of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2): review of current literature. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2021; 42:659–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walsh KA, Spillane S, Comber L, et al. The duration of infectiousness of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. J Infect 2020; 81:847–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chopra V, Flanders SA, O’Malley M, Malani AN, Prescott HC. Sixty-day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 2021; 174:576–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Saad M, Laghi FA, Brofman J, Undevia NS, Shaikh H. Long-term acute care hospital outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Crit Care Med 2022; 50:256–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lorenzo-Redondo R, Nam HH, Roberts SC, et al. A clade of SARS-CoV-2 viruses associated with lower viral loads in patient upper airways. EBioMedicine 2020; 62:103112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Touchstone LA . What happens when the coronavirus mutates? | Illinois. Available at: https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/1386071796. Accessed 1 November 2021.

- 11. Fraaij PL, Schutten M, Javouhey E, et al. Viral shedding and susceptibility to oseltamivir in hospitalized immunocompromised patients with influenza in the Influenza Resistance Information Study (IRIS). Antivir Ther 2015; 20:633–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Illinois Department of Public Health . Infectious disease reporting. Available at: https://dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/diseases-and-conditions/infectious-diseases/infectious-disease-reporting. Accessed 1 November 2021.

- 13. van Kampen JJA, van de Vijver DAMC, Fraaij PLA, et al. Duration and key determinants of infectious virus shedding in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). Nat Commun 2021; 12:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Folgueira MD, Luczkowiak J, Lasala F, Pérez-Rivilla A, Delgado R. Prolonged SARS-CoV-2 cell culture replication in respiratory samples from patients with severe COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Infect 2021; 27:886–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wölfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature 2020; 581:465–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harcourt J, Tamin A, Lu X, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from patient with coronavirus disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26:1266–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moore NM, Li H, Schejbal D, Lindsley J, Hayden MK. Comparison of two commercial molecular tests and a laboratory-developed modification of the CDC 2019-ncov reverse transcriptase PCR assay for the detection of sars-cov-2. J Clin Microbiol 2020; 58:e00938-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Real-time RT-PCR diagnostic panel. For emergency use only. For in-vitro diagnostic (IVD) use. CDC 2020; 80. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/134922/download. Accessed 1 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J 2011; 17:10. [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Institutes of Health . NIH COVID-19 treatment guidelines. Available at: https://files.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/guidelines/archive/covid19treatmentguidelines-08-04-2021.pdf. Accessed 24 April 2022.

- 21. Glans H, Gredmark-Russ S, Olausson M, et al. Shedding of infectious SARS-CoV-2 by hospitalized COVID-19 patients in relation to serum antibody responses. BMC Infect Dis 2021; 21:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aydillo T, Gonzalez-Reiche AS, Aslam S, et al. Shedding of viable SARS-CoV-2 after immunosuppressive therapy for cancer. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2586–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Avanzato VA, Matson MJ, Seifert SN, et al. Case study: prolonged infectious SARS-CoV-2 shedding from an asymptomatic immunocompromised individual with cancer. Cell 2020; 183:1901–12, e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baang JH, Smith C, Mirabelli C, et al. Prolonged severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 replication in an immunocompromised patient. J Infect Dis 2021; 223:23–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choi B, Choudhary MC, Regan J, et al. Persistence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an immunocompromised host. N Engl J Med 2020; 383:2291–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scola BL, Bideau ML, Andreani J, et al. Viral RNA load as determined by cell culture as a management tool for discharge of SARS-CoV-2 patients from infectious disease wards. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2020; 39:1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bullard J, Dust K, Funk D, et al. Predicting infectious severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 from diagnostic samples. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:2663–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Basile K, McPhie K, Carter I, et al. Cell-based culture informs infectivity and safe de-isolation assessments in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e2952-9. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33098412/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Singanayagam A, Patel M, Charlett A, et al. Duration of infectiousness and correlation with RT-PCR cycle threshold values in cases of COVID-19, England, January to May 2020. Euro Surveill 2020. Available at:https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.32.2001483. Accessed 21 September 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Saud Z, Ponsford M, Bentley K, et al. Mechanically ventilated patients shed high titre live SARS-CoV2 for extended periods from both the upper and lower respiratory tract. Clin Infect Dis 2022. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Funk DJ, Bullard J, Lother S, et al. Persistence of live virus in critically ill patients infected with SARS-COV-2: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 2022; 26:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ong SWX, Chiew CJ, Ang LW, et al. Clinical and virological features of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: a retrospective cohort study comparing B.1.1.7 (Alpha), B.1.315 (Beta), and B.1.617.2 (Delta). Clin Infect Dis 2021. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Science brief: Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/scientific-brief-omicron-variant.html. Accessed 29 December 2021. [PubMed]

- 34. Chen C, Gao G, Xu Y, et al. SARS-CoV-2–positive sputum and feces after conversion of pharyngeal samples in patients with COVID-19. Ann Intern Med 2020; 172:832–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang K, Zhang X, Sun J, et al. Differences of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 shedding duration in sputum and nasopharyngeal swab specimens among adult inpatients with coronavirus disease 2019. Chest 2020; 158:1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Egbuonu K, Hyle EP, Hurtado RM, et al. Yield of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 lower respiratory tract testing after a negative nasopharyngeal test among hospitalized persons under investigation for coronavirus disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8:ofab257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Infectious Diseases Society of America . IDSA guidelines on the diagnosis of COVID-19: molecular diagnostic testing. Available at: https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-diagnostics/. Accessed 29 August 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38. National Institute for Biological Standards and Control . First WHO international standard for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Available at: https://www.nibsc.org/products/brm_product_catalogue/detail_page.aspx?catid=20/146. Accessed 13 December 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.