Summary

The entire landscape of dermatology service provision has been transformed by the current SARS‐CoV‐2 (COVID) pandemic, with virtual working having become the new norm across the UK. A pre‐pandemic UK‐wide survey of dermatology registrars in training demonstrated a huge shortfall in trainee confidence in their teledermatology skills, with only 15% feeling even slightly confident, while 96% of trainees surveyed felt that more teaching in this area was needed. We carried out a follow‐up trainee survey during the COVID‐19 pandemic, which showed that the sudden thrust into virtual working had achieved dramatic gains in trainee confidence, propelling the percentage of trainees that now felt slightly confident to 58%. However, the shortfall remains, as does the pressing need to incorporate teledermatology into the trainee teaching timetable.

The COVID‐19 pandemic has been a crash course in teledermatology for all concerned. A previous study of UK dermatology registrars pre‐COVID‐19 demonstrated that only 15% of the surveyed dermatology registrars in training felt even slightly confident in their ability to deal with teledermatology referrals.1 Trainee access to teledermatology teaching and training was highly variable across the UK, with up to 46% of respondents surveyed having no teaching at all in this area and 96% agreeing that more teaching was needed.1 The current Joint Royal Colleges of Physicians Training Board dermatology curriculum2 does not include teledermatology as a competency, but this is being rectified imminently in the new August 2021 dermatology curriculum. A rapid overhaul of training is needed to address this shortfall and bring training up to speed with both the new curriculum and the ground realities of current dermatology practice.

Dermatologists, consultants and registrars alike have been forced to innovate and navigate unfamiliar virtual territory because of the COVID‐19 pandemic. With social distancing measures affecting the allowable volume of face‐to‐face (FTF) clinic throughput until a more permanent solution to SARS‐CoV‐2 is found, and the future clearly trending towards a shift to virtual working in the long term, data were needed to see how dermatologists in training were adapting to these unprecedented alterations in service delivery.

Report

We carried out a UK‐wide follow‐up survey of dermatology registrars in training, asking about their experience of teledermatology and virtual working during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Responses were collected during the period 11–31 August 2020, using an online survey tool, SmartSurvey®. Our aim was to ascertain the degree of confidence trainees felt with teledermatology and virtual working 5 months into the COVID‐19 pandemic. Most trainees were returned from redeployment back to their usual workplace, only to find an entirely transformed landscape of dermatology service provision and training. Of the 31 respondents (response rate, 15%), 100% had conducted virtual consultations in some shape or form during the pandemic. Of these, 94% had carried out telephone consultations, 58% used images for inpatient ward reviews and 26% had taken video consultations. Respondents were well represented across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, as well as across all levels of specialty training (ST3–ST6): 23% of respondents were at ST3 level, another 23% at ST4 level, 26% were ST5 trainees, 23% were final year trainees (ST6) and CESR clinical fellows made up the remaining 7%.

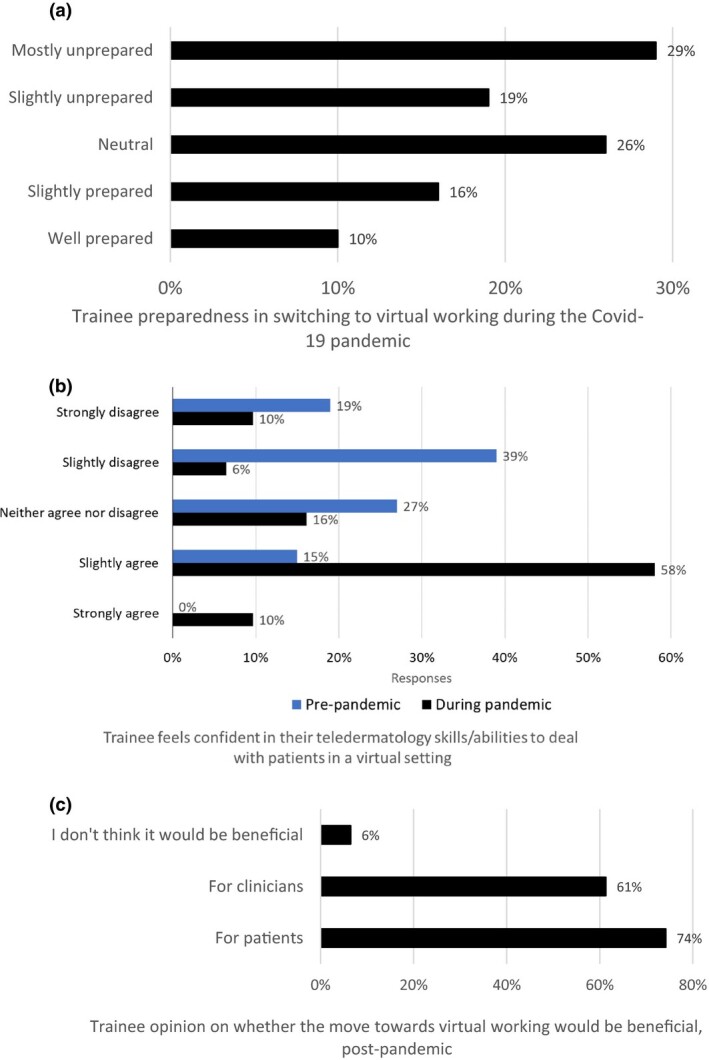

Most respondents (61%) used virtual working for managing both new and follow‐up patients, 32% for follow‐ups only and 7% for new patients only. Virtual working during the pandemic was excellently supported for trainees, with 94% having access to a supervising consultant. We used a five‐point Likert scale to assess trainee preparedness for the shift to virtual working and their confidence in teledermatology practice during the pandemic. However, only 10% felt well prepared for the sudden shift to virtual working, 16% felt slightly prepared, which correlated well with pre‐COVID‐19 trainee confidence levels (Fig. 1b) and most (74%) felt neutral or unprepared (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Trainee preparedness in switching to virtual working during the COVID‐19 pandemic; (b) comparison of trainee confidence levels in teledermatology pre‐pandemic and during the pandemic; and (c) trainee opinion on whether increased virtual working would be beneficial, post‐pandemic.

Interestingly, we noted a dramatic rise in trainee confidence levels (Fig. 1b), with 58% of respondents now feeling slightly confident compared with only 15% in the previous pre‐pandemic survey1 7 months earlier.

Finally, most trainees (74%) agreed that a move towards virtual working would be beneficial post‐pandemic for patients, while 61% agreed that it would also be beneficial for clinicians.

Enforced adaption to teledermatology and virtual working has brought about rapid gains in trainee confidence, which a concerted teaching programme might not have achieved as quickly. Nevertheless, more work is needed. Trainees drawn into the bubble of virtual working have much to say about the practicalities and pitfalls facing them (Table 1). These insights could be used to develop future service provision and training. In the pre‐pandemic survey, trainees were keen on the establishment of local teledermatology services in their workplace with increased direct trainee involvement,1 as at the time these services were either nascent in evolution or entirely nonexistent, but COVID‐19 has already pushed teledermatology provision across the UK to 100%.

Table 1.

Selected quotes from trainees suggesting ways of supporting teledermatology and virtual working.

| Potential areas for improvement | Quotes |

| Formal teaching sessions, including avoidance of pitfalls | We've all been learning on the job but in future it might be nice to have some teaching on it |

| There will be an increasing shift towards telederm and virtual clinics from now on, so more training needs to be provided | |

| Online learning modules for trainees | |

| Dedicated training session on telephone and video consultations, highlighting potential pitfalls and how to deal with them | |

| Supervised reporting sessions/virtual consultations | Regular supervised sessions, e.g. triaging |

| Allocated time for consultants to supervise trainees during consultation times | |

| Three‐way phone/video consultations with a consultant | |

| Improved IT support, equipment and training | Better induction into virtual platforms for trainees |

| Need for more investment in IT | |

| Working practices and equipment standards would go a long way to ensure the new way of working is supported by the specialty, i.e. hands‐free headsets, quiet environment, ability to use multiple screens if needed, etc. | |

| Standardization of local working practices and expectations from trainees | Better access to software, e.g. video consults, better photo quality from GP referrals |

| Would be good to see how other units do it as it is a very new service in our department, and we are having lots of teething problems | |

| Developing a more streamlined system, based on guidelines/evidence, which would inspire confidence | |

| Reducing barriers | Certainly, in our deanery it needs to be incorporated into existing schedules so we as trainees know when we are doing telederm clinics |

| Have worked in two hospitals with different set ups. One has worked very well – text messages sent to patients a week before with request for photographs – these were uploaded by secretary to records and reviewed prior to an allocated telephone call. Video not very helpful and poor quality | |

| Reducing barriers to being able to see photographs – whether that’s patients emailing/messaging them directly or having cameras on the wards that ward doctors can use to upload, instead of needing a photography team to come to the wards |

GP, general practitioner; IT, information technology.

Going forward, as training needs must reflect the reality of everyday clinical practice, we highlight the importance of including formal teledermatology teaching in trainee timetables.3 This could take the form of consultant‐guided teledermatology triage sessions for primary care referrals, in which trainees are directly supervised to do the reporting. This would build trainee confidence in decision‐making, especially with regard to discharging new referrals where appropriate, amid the uncertainties of less visual information than can be gained in an FTF consultation. In addition, it may provide a potential solution for clearing the pandemic‐induced backlog of primary care referrals facing most dermatology centres, by combining training needs with service delivery.

In the USA, the Accreditation Counsel for Graduate Medical Education now permits residents to use telemedicine under supervision for patient care.4 In a recent paper describing their pandemic experience, Oldenburg and Marsch 5 suggested that institutions should immediately start implementing workflows that incorporate residents in order to avoid disruption in resident education. They described using an electronic medical record software application to perform virtual video visits, in which multiple providers simultaneously interface with the patient from distinct and remote locations. This enables residents to lead the consultation under direct supervision of the patient’s attending physician, who is also logged into the video visit.5

International experience of disruption to undergraduate and postgraduate dermatology training caused by the pandemic also suggests that teledermatology itself can provide a solution for maintaining education, with the wholesale replacement of FTF teaching by online teaching in the form of webinars and video‐conferencing, as well as remote practical examinations for which virtual case scenarios and images replace patients.6, 7

Wider issues of virtually managing patients can potentially create frustrations and anxieties that are also new for junior and senior dermatologists alike. Similarly, the greater time required for managing an individual patient potentially reduces access to the dermatology service for our population. A permanent photographic record should allow new opportunities for learning from retrospective image analysis, but may also raise new concerns about errors in diagnosis that are now documented with technologies that are not yet familiar. As teledermatology takes centre stage during this crisis, the extra information and experience from an FTF ‘three‐dimensional’ encounter will for now be a rare and precious thing for trainees, the experience of which makes the limited information from a ‘two‐dimensional’ encounter easier to interpret for the pre‐COVID‐19 generation of dermatologists.

The COVID‐19 pandemic provides an opportunity to develop different ways of working, but both positive and negative experiences should inform safe and effective alternatives to teach, train and deliver dermatology services for the foreseeable future.

Learning points.

A previous, pre‐COVID‐19 survey in January 2020 identified a vital gap in UK dermatology registrar confidence with regard to their teledermatology skills, with only 15% of trainees feeling even slightly confident.

The landscape of dermatology services across the UK changed dramatically very shortly after, and the pandemic‐induced crash course in virtual working has led to rapid gains in trainee confidence in teledermatology (58% of trainees now feel slightly confident).

However, more formal training and support in this area is needed to bring trainees up to speed with the demands of virtual working in a post‐COVID‐19 digital era.

Contributor Information

A. Lowe, Department of Dermatology Royal Gwent Hospital Gwent UK.

A. Pararajasingam, Department of Dermatology Royal Gwent Hospital Gwent UK

R. G. Goodwin, Department of Dermatology Royal Gwent Hospital Gwent UK

References

- Lowe A, Pararajasingam A, Goodwin R. A UK‐wide survey looking at teaching and trainee confidence in teledermatology: a vital gap in a COVID‐19‐induced era of rapid digital transformation? Clin Exp Dermatol 2020; 45: 876–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint Royal College of Physicians Training Board. Specialty curriculum for dermatology August 2010 (amendment August 2012). Available at: https://www.jrcptb.org.uk/sites/default/files/2010%20Dermatology%20%28amendment%202012%29.pdf (accessed 1 September 2020).

- Hussain K, Patel NP. Fast‐tracking teledermatology into dermatology trainee timetables, an overdue necessity in the COVID‐era and beyond. Clin Exp Dermatol 2020. 10.1111/ced.14427 (accessed 7 December 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education ACGME Response to the coronavirus (COVID‐19). 18 March 2020. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Newsroom/Newsroom‐Details/ArticleID/10111/ACGME‐Response‐to‐the‐Coronavirus‐COVID‐19 (accessed 30 September 2020).

- Oldenburg R, Marsch A. Optimizing teledermatology visits for dermatology resident education during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82: e229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Bishnoi A, Vinay K. Changing paradigms of dermatology practice in developing nations in the shadow of COVID‐19: lessons learnt from the pandemic. Dermatol Ther 2020; 33: e13472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat YJ, Aslam A, Hassan I, Dogra S. Impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on dermatologists and dermatology practice. Indian Dermatol Online J 2020; 11: 328–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]