The COVID‐19 pandemic emerged when India was already facing an epidemic‐like situation of superficial dermatophytosis (tinea). The prevalence of tinea in India is currently 27.6%, with tinea faciei accounting for 1.8% cases.1 The use of face masks, although necessary, has the potential to aggravate a worrisome situation with regard to tinea in India.

We report seven nonfamilial cases of tinea faciei (confirmed by culture and potassium hydroxide staining) all of which involved the facial area covered by a mask (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Table 1). The lesions appeared after the patients began using masks. Mean duration of mask use was 6–7 h/day. Patients reused masks without daily washing (mean duration 6–7 days before washing), and the used masks were often stored and washed with other clothing. Five patients had pre‐existing plaques of tinea (tinea corporis, cruris and unguium) elsewhere. Presence of tinea infections among family members was noted in four patients, three of whom gave a history of sharing masks with other family members. Three patients had pre‐existing diabetes mellitus. All the patients were treated with oral and topical antifungals, and given advice regarding proper mask use.

Figure 1.

(a,b) Tinea faciei presenting as (a) a serpiginous plaque localized above left nasolabial fold in Patient1 and (b) as scaly plaque with a defined margin seen in the neck region in Patient 2. (c) Lactophenol cotton blue mount showing tear‐drop microconidia consistent with Trichophyton rubrumin a culture from Patient 1.

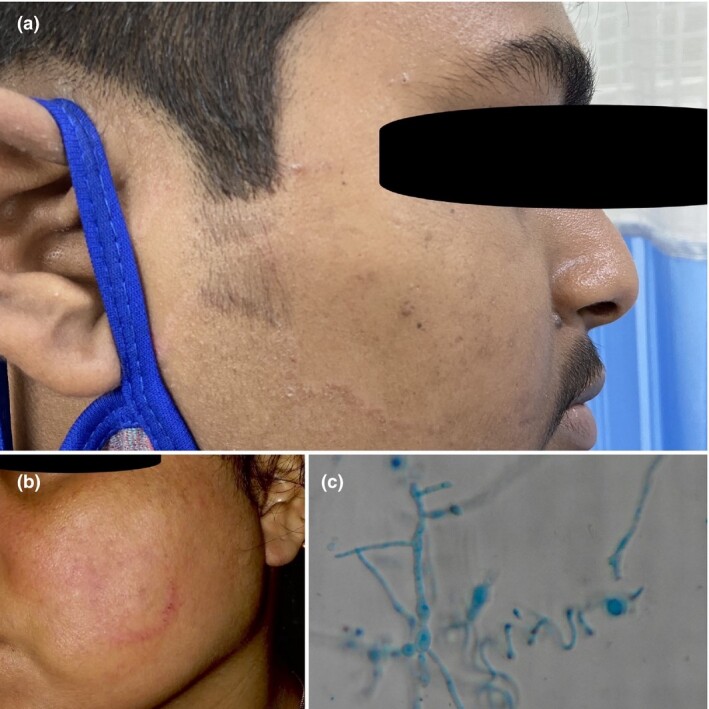

Figure 2.

(a,b) Tinea faciei as (a) an annular plaque 30 × 30 mm in size on the right cheek in Patient 3 (b) and (b) as an erythematous annular plaque localized to the leftcheek of Patient 4. (c) Lactophenol cotton blue mount showing spiral hyphae consistent with Trichophyton mentagrophytesin a culture from Patient 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients presenting with ‘mask tinea’.

| Patient | Age, years/sex | Fungal culture | Location of tinea on face | Mean duration of mask use per day, h | Tinea lesions elsewhere in the body | Mean duration between washing masks, days | Family history of tinea | Sharing of mask among family members | Concurrent disease/medication |

| 1 | 50/M | Trichophyton rubrum | Above left nasolabial fold | 8–10 | Tinea corporis, cruris and unguium (toe) | 7 | Yes | No | Type 2 DM, uncontrolled/insulin |

| 2 | 35/F | T. rubrum | Neck region | 6 | No | 7 | Yes | Yes | Type 2 DM, controlled/metformin |

| 3 | 30/M | Trichophyton mentagrophytes | Right cheek | 8 | Tinea cruris | 3–4 | No | No | – |

| 4 | 40/F | T. mentagrophytes | Left cheek | 6–8 | No | 5 | Yes | Yes | Type 2 DM, controlled/metformin |

| 5 | 25/M | T. mentagrophytes | Left cheek | 8–10 | Tinea cruris, corporis and unguium (finger) | 5–7 | Yes | Yes | – |

| 6 | 43/M | T. rubrum | Right cheek | 6–8 | Tinea cruris | 10 | No | No | – |

| 7 | 18/F | T. mentagrophytes | Right cheek | 6 | Tinea cruris | 7 | No | No | – |

Face masks create a humid microenvironment due to occlusion and increased sweating, which are the perfect conditions for the fungus. In a tropical country such as India where the burden of tinea is already high, we believe that the widespread promotion and use of cloth face masks is acting as a source for the inoculation and spread of dermatophytes.2, 3 In all patients, the source of infection was either from a coexisting area of tinea elsewhere or from an infected family member. Most of the patients reused and shared masks, and washed masks along with their regular clothing. Hammer et al. found that 10% of infectious material was transferred from contaminated to sterile textiles during common storage, and 16% of spores were transferred during washing of clothes in the same vessel. Washing of contaminated clothes at 60 °C is recommended to eliminate fungal pathogens, which is not commonly practised in India. This explains how the fungus spreads from clothes to the mask, and persists even after regular washing.4 Family history of tinea, fomite spread, tight clothing, hot and humid climate, and pre‐existing diabetes are documented risk factors for acquiring tinea (noted in our patients).5 Multiple lockdowns impinging access to healthcare, along with personal neglect and use of over‐the‐counter treatments could also be precipitating factors.

We propose calling this new variant of tinea faciei, ‘mask tinea’, owing to its peculiar location, associated cosmetic blemishes and difficulty in prevention. The masking effect due to the protective face covers could lead to a delay in diagnosis, thus we advocate thorough examination of the mask area in patients with tinea. A limitation of our case series is that we cannot confidently attribute this type of tinea solely to the wearing of masks, as other proven risk factors should be considered as well. Establishing the causality requires further case−control studies.

As dermatologists, we should be aware about this increasing problem due to the novel mask requirements by the general public during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Consequently, proper counselling regarding use, handling and sanitization of the ubiquitous mask should also be done.

Contributor Information

A. Agarwal, Department of Dermatology IMS & SUM Hospital Bhubaneshwar India

T. Hassanandani, Department of Dermatology IMS & SUM Hospital Bhubaneshwar India

A. Das, Department of Dermatology KPC Medical College and Hospital Kolkata India

M. Panda, Department of Dermatology IMS & SUM Hospital Bhubaneshwar India

S. Chakravorty, Department of Microbiology Bhagirathi Neotia Woman and Child Care Centre Kolkata India

References

- Ganeshkumar P, Mohan S, Hemamalini M et al. Epidemiological and clinical pattern of dermatomycoses in rural India. Indian J Med Microbiol 2015; 33: 134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Madhu R. The great Indian epidemic of superficial dermatophytosis: an appraisal. Indian J Dermatol 2017; 62: 227–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Helath and Family Welfare. Advisory on use of homemade protective cover for face & mouth. 2020. Available at: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Advisory&ManualonuseofHomemadeProtectiveCoverforFace&Mouth.pdf. (accessed 2 November 2020).

- Hammer T, Mucha H, Hoefer D. Infection risk by dermatophytes during storage and after domestic laundry and their temperature‐dependent inactivation. Mycopathologia 2010; 171: 43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Verma P, Chandra U et al. Risk factors for chronic and chronic‐relapsing tinea corporis, tinea cruris and tinea faciei: results of a case–control study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2019; 85: 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]