A 46‐year‐old man with hypercholesterinaemia and coronary heart disease presented to the emergency department with a 3‐day history of fatigue, dry cough and fever. He was febrile with a temperature of 39.5 °C and an oxygen saturation of 91% while breathing ambient air, with a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min.

Laboratory tests showed elevated levels of C‐reactive protein (13 mg/dL; normal < 0.5 mg/dL) and interleukin‐6 (125 pg/mL; normal < 5.9 pg/mL). White blood cell count was normal, but he had eosinopenia (< 1%; normal range 1–4%). An oropharyngeal swab for COVID‐19 testing was positive. Chest computed tomography showed bilateral ground‐glass opacities.

As he was showing increasing respiratory distress, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit with severe acute respiratory syndrome, where invasive mechanical ventilation was conducted for 9 days. Empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy with meropenem and azithromycin was administered with improvement of the patient’s condition.

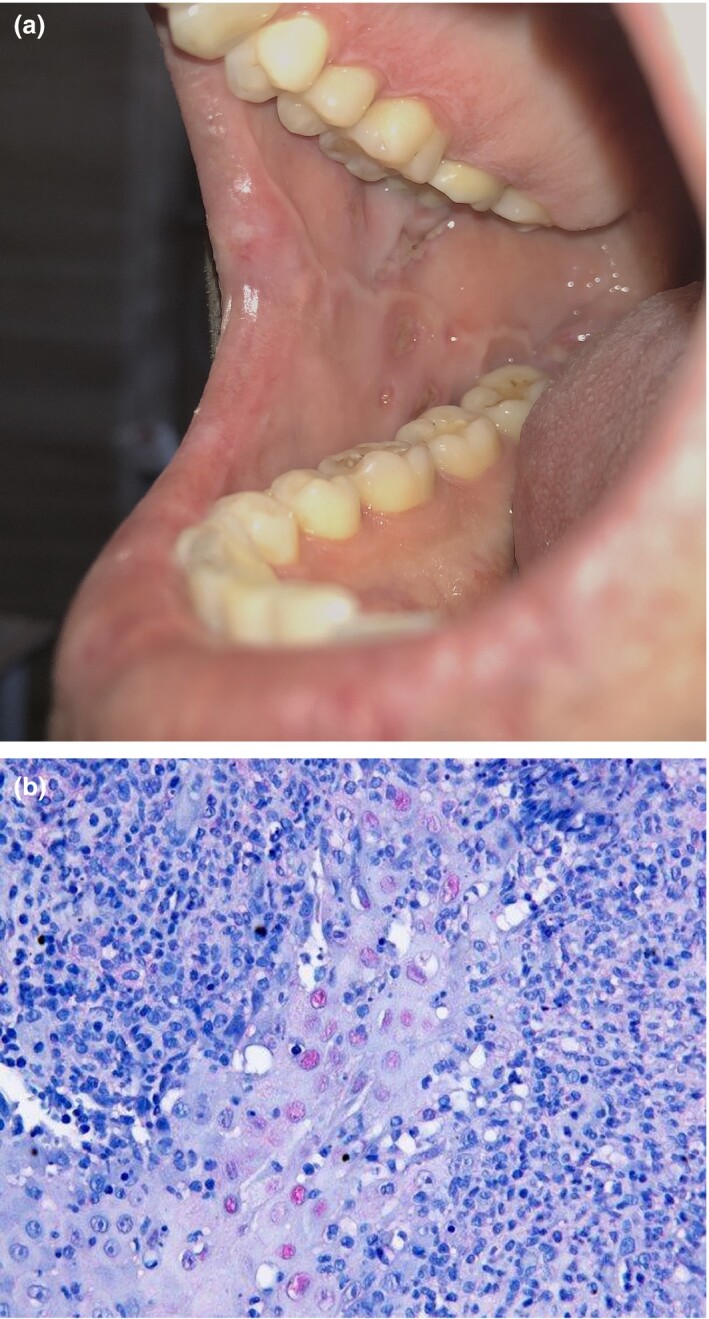

Three days after extubation and recurrence of wellbeing, the patient reported painful ulcerations in his mouth. Dermatological examination revealed multiple sharply circumscribed ulcerations of the oral mucosa covered by yellow–grey membranes (Fig. 1a). Apart from submandibular lymphadenitis, no further skin changes or pathologies were found. His medical history included recurrent herpes labialis infection.

Figure 1.

(a) Ulcerations in the right side of buccal mucosa; (b) multiple nuclei with herpes simplex virus 1/2 antibodies after immunohistochemical staining (original magnification × 40).

As the patient was originally from the Middle East, genomic analysis was performed after informed consent was obtained. Analysis of human leucocyte antigen (HLA)‐B*51, B*27 and B*44 was negative.

A pathergy test was performed on the middle of the right forearm with no pathological sign after 24 and 48 h; thus in the absence of genital ulcerations and nonfollicular pustules the diagnosis of Behçet disease could be excluded.1 Skin biopsy and dermatohistopathological examination showed central ulcerations with apoptotic keratinocytes and interface dermatitis. After immunohistochemical staining, multiple nuclei with herpes simplex virus (HSV)‐1/2 antibodies were visible (Fig. 1b).

Buccal swabs revealed a normal oral microbiome, and HSV‐1 DNA was detected by PCR. When we checked the initial serum sample taken before inpatient care, we detected anti‐HSV‐1 IgG, and in subsequent serum samples we also found anti‐HSV‐IgM, which was compatible with HSV‐1 reactivation.

Based on the results and the patient’s medical history, we diagnosed secondary herpetic gingivostomatitis (SHGS) in the context of COVID‐19 infection. In contrast to primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, which represents the initial primoinfection with HSV in infants and adults, SHGS develops regularly in immunosuppressed adults and shows a more severe progression of disease with increasing age.2, 3

Because of the patient’s discomfort and the prolonged ICU treatment, oral aciclovir therapy 400 mg five times daily was administered, which resulted in rapid improvement of pain and ulcerations.4 Given the patient’s age and the rare secondary manifestation of HSV‐1 in the oral cavity, we believe that the COVID‐19 infection and prolonged inpatient care were causal factors of stress induction and immunosuppression, leading to the distinct oral manifestations.

Acknowledgement

We thank the patient for his written informed consent to publication of his case details.

Contributor Information

T. Kämmerer, Department of Dermatology and Allergology University Hospital Munich Munich Germany

J. Walch, Department of Dermatology and Allergology University Hospital Munich Munich Germany

M. Flaig, Department of Dermatology and Allergology University Hospital Munich Munich Germany

L. E. French, Department of Dermatology and Allergology University Hospital Munich Munich Germany

References

- Hatemi G, Christensen R, Bang D, et al. 2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of Behcet's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77: 808–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley RJ. Herpes simplex virus infection. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 2002; 13: 6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin PJ, Ajar AH. Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis in adults: a review of 13 cases, including diagnosis and management. J Can Dent Assoc 2002; 68: 247–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasser M, Fedorowicz Z, Khoshnevisan MH, Shahiri Tabarestani M. Acyclovir for treating primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (4): CD006700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]