Summary

Background

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic has spread, information about COVID‐19 and skin disease or related biologics is still lacking.

Objectives

To identify the association between COVID‐19 and skin diseases or biologics.

Methods

A nationwide claim dataset relevant to COVID‐19 in South Korea was analysed. This dataset included insurance claim data before and during COVID‐19 treatment and clinical outcomes. Claim data related to skin diseases and relevant biologics were analysed to determine the association of COVID‐19 with skin diseases and relevant biologics.

Results

The dataset contained a total of 234 427 individuals (111 947 male and 122 480 female) who underwent COVID‐19 testing. Of them, 7590 (3·2%) were confirmed as having COVID‐19, and 227 (3·0%) confirmed patients died. Among various skin diseases and biologics, no significant increase in the presence of specific skin diseases or exposure to biologics was observed in the COVID‐19‐positive group, even after adjusting for or matching covariates. The presence of skin diseases and exposure to biologics also did not seem to affect clinical outcomes including mortality.

Conclusions

Underlying skin diseases did not appear to increase susceptibility to COVID‐19 or mortality from COVID‐19. Considering the risks and benefits, biologics for dermatological conditions might be continuously used during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) was first found in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China in December 2019 and has now become a global pandemic.1 COVID‐19 is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), which is an enveloped, nonsegmented, positive‐sense, single‐stranded RNA virus.2 SARS‐CoV‐2 infection causes immune responses including a T‐cell response.2 Previous studies reported that COVID‐19 can cause immune dysregulation in the form of cytokine storms, including an elevation of inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α, interleukin (IL)‐1β, IL‐4, IL‐12p70 or IL‐17A.3, 4

Many skin diseases, such as alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, rosacea and vitiligo, are known to be caused by abnormal immunological pathways.5–9 Classic immunosuppressants are broadly used for various dermatological conditions, and recently, biologics targeting specific cytokines have been widely used in dermatology.10 Studies of patients with severe COVID‐19 reported elevated serum levels of TNF‐α and IL‐17, which are major targets of biologics in dermatology.11 In addition, recent articles have reported cases of COVID‐19 in dermatological patients under biologic treatments,12–18 and thus there is a concern regarding maintenance of biologics for skin diseases during the COVID‐19 pandemic.10, 19

South Korea borders China and experienced an early outbreak of COVID‐19 in February 2020.20 Recently, the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service (HIRA) in South Korea opened a dataset of emerging confirmed cases of COVID‐19 from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) and insurance claims relevant to cases of COVID‐19 (OpenData4Covid19). In this study, we aimed to identify the association of COVID‐19 with the presence of skin diseases and the use of biologics.

Patients and methods

Study design, data source and study population

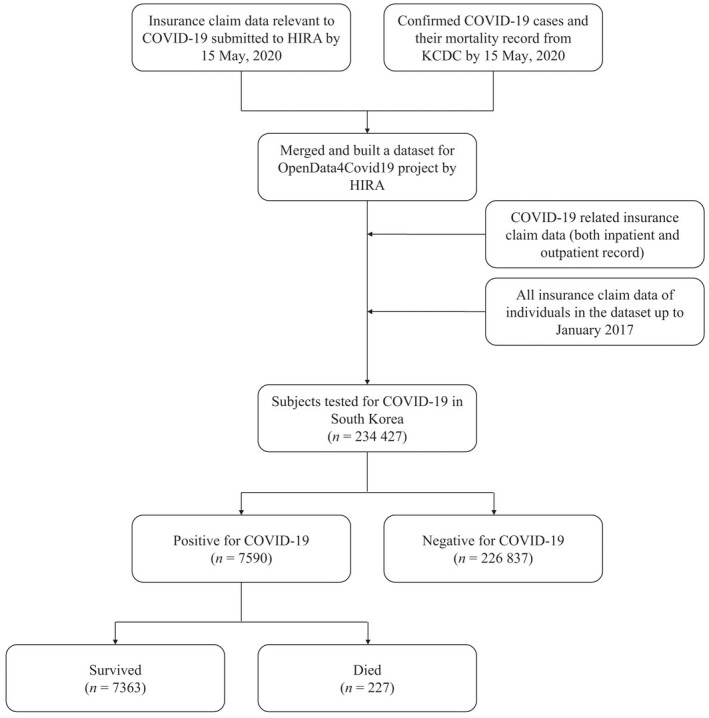

This study was a cross‐sectional study using nationwide claim data in South Korea. The OpenData4Covid19 project is provided by HIRA via their website (https://hira‐covid19.net). According to the guidelines in South Korea, KCDC confirmed cases of COVID‐19 based on laboratory tests, SARS‐CoV‐2 real‐time reverse‐transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, or virus isolation.20, 21 HIRA released a dataset of relevant insurance claims up to 15 May 2020 of those who were tested for COVID‐19, along with the individual’s claim records for the past 3 years, which were merged with data of SARS‐CoV‐2 confirmation and mortality from KCDC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of the OpenData4Covid19 dataset. HIRA, Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service; KCDC, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The government of South Korea has actively traced people suspected of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection or those who had close contact with patients with COVID‐19, based on advanced information technology,22, 23 to find almost all potential patients with COVID‐19 in South Korea.23, 24 In this regard, the OpenData4Covid19 dataset built by HIRA and KCDC contains almost all confirmed and suspicious but negative cases of COVID‐19 in South Korea and is highly reliable.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University Hospital (no. E‐2004‐036‐1116).

Definition of skin diseases and related biologics

The dataset contains all claim records of patients up to 3 years before COVID‐19 tests. All Korean residents are required to join the National Health Insurance System, and insurance claims regarding their visits to any health institution are stored in this system.25 Thus, the dataset contained all medical insurance claim data of the patient, including dates of visits, the locations of medical institutes, diagnostic codes, procedures, treatments and the prescription of drugs.26

Patients with specific skin diseases were defined as those who had more than three claim records between 2017 and COVID‐19 testing, with International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision codes as follows: alopecia areata (L63.x), atopic dermatitis (L20.x), psoriasis (L40.x), rosacea (L71.x) and vitiligo (L80). In adjusting for other comorbidities, patients with diabetes (E10.x–E14.x), hypertension (I10.x), heart failure (I50.x) and chronic pulmonary disease (CPD; I27.8, I27.9, J40–J47, J60–J67.x, J68.4, J70.1, J70.3) were defined by the same method.

Patients exposed to biologics were defined as those with a history of any biologic prescription between October 2019 and COVID‐19 testing, considering the early outbreak in South Korea. Biologics approved for dermatological use (including psoriatic arthritis) in South Korea are as follows: TNF‐α inhibitors (etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab), IL‐12/23 inhibitor (ustekinumab), IL‐23 inhibitor (guselkumab), IL‐17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab) and IL‐4/13 inhibitor (dupilumab).

Clinical outcomes

The main outcome in this study was SARS‐CoV‐2 infection among patients with specific skin diseases and those being treated with biologics. The secondary outcome was a severe clinical course in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, defined by hospitalization, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), ventilator use or mortality. Hospitalization was confirmed by the claim dataset relevant to admission. ICU admission and ventilator use were defined by the claim record during hospitalization for COVID‐19 treatment. Mortality was based on the transferred data from KCDC mentioned above.

Statistical analysis

To reduce potential bias, we matched controls to cases according to propensity scores computed with a nonparsimonious logistic regression model. The covariates included for propensity scores were age, sex, residency, and comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, heart failure and CPD. An explosive outbreak related to a religious group in Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk‐do (Dae‐Gyeong area) occurred,20 and thus residency was further subdivided as to whether a patient was in the Dae‐Gyeong area or not. These locations had more confirmed cases of COVID‐19 per population than other cities or provinces in South Korea. For example, the number of confirmed cases in the Dae‐Gyeong area was 72·4 per 100 000 persons, which was more than 66 times greater than the 1·1 per 100 000 persons in other cities and provinces in South Korea, as of 2 March 2020.20

Pearson’s χ2‐test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, and Student’s t‐test was used for continuous variables. Outcomes from logistic regression are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. All statistical tests were performed with SAS version 9·4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographics of the population

The dataset contained 234 427 patients (111 947 male and 122 480 female) who had been tested for COVID‐19. Of them, 7590 (3·2%; 3095 male and 4495 female) were positive for COVID‐19. The COVID‐19‐positive group had more female patients and was younger overall compared with the COVID‐19‐negative group (Table 1). Most COVID‐19 testing was conducted in provinces other than the Dae‐Gyeong area (n = 197 252, 84·1%), but there were more confirmed COVID‐19 cases in the Dae‐Gyeong area (n = 4234, 55·8%). Thus, the rate of positive COVID‐19 tests was significantly higher in the Dae‐Gyeong area (11·4% vs. 1·7%, P < 0·001).

Table 1.

Demographics of the population according to the results of COVID‐19 testing

| Total | Areas | ||||||||

| Dae‐Gyeong areaa | Other cities and provinces | ||||||||

| COVID‐19 negative | COVID‐19 positive | P‐value | COVID‐19 negative | COVID‐19 positive | P‐value | COVID‐19 negative | COVID‐19 positive | P‐value | |

| n = 226 837 | n = 7590 | n = 32 941 | n = 4234 | n = 193 896 | n = 3356 | ||||

| Sex | < 0·001 | < 0·001 | < 0·001 | ||||||

| Male | 108 852 (48·0) | 3095 (40·8) | 15 743 (47·8) | 1707 (40·3) | 93 109 (48·0) | 1388 (41·4) | |||

| Female | 117 985 (52·0) | 4495 (59·2) | 17 198 (52·2) | 2527 (59·7) | 100 787 (52·0) | 1968 (58·6) | |||

| Age (years), mean ± SD) | 46·8 ± 21·9 | 45·9 ± 19·8 | < 0·001 | 48·4 ± 21·0 | 50·3 ± 20·0 | < 0·001 | 46·6 ± 20·0 | 40·3 ± 18·0 | < 0·001 |

| Age (years) | < 0·001 | < 0·001 | < 0·001 | ||||||

| 0–9 | 9211 (4·1) | 82 (1·1) | 968 (2·9) | 37 (0·9) | 8243 (4·3) | 45 (1·3) | |||

| 10–19 | 8367 (3·7) | 346 (4·6) | 925 (3·0) | 132 (3·1) | 7442 (3·8) | 214 (6·4) | |||

| 20–29 | 39 827 (17·6) | 1855 (24·4) | 5355 (16·3) | 809 (19·1) | 34 472 (17·8) | 1046 (31·2) | |||

| 30–39 | 38 517 (17·0) | 776 (10·2) | 5202 (15·8) | 367 (8·7) | 33 315 (17·2) | 409 (12·2) | |||

| 40–49 | 32 010 (14·1) | 1003 (13·2) | 4960 (15·1) | 512 (12·1) | 27 050 (14·0) | 491 (14·6) | |||

| 50–59 | 30 303 (13·4) | 1503 (19·8) | 5218 (15·8) | 886 (20·9) | 25 085 (12·9) | 617 (18·4) | |||

| 60–69 | 25 859 (11·4) | 1061 (14·0) | 4129 (12·5) | 737 (17·4) | 21 730 (11·2) | 324 (9·6) | |||

| 70–79 | 22 544 (9·9) | 590 (7·8) | 3252 (9·9) | 444 (10·5) | 19 292 (9·9) | 146 (4·4) | |||

| ≥ 80 | 20 199 (8·9) | 374 (4·9) | 2932 (8·9) | 310 (7·3) | 17 267 (8·9) | 64 (1·9) | |||

| Province | < 0·001 | ||||||||

| Dae‐Gyeong areaa | 32 941 (14·5) | 4234 (55·8) | |||||||

| Others | 193 896 (85·5) | 3356 (44·2) | |||||||

| Comorbidity | |||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 37 067 (16·3) | 965 (12·7) | < 0·001 | 5283 (16·0) | 712 (16·8) | 0·35 | 31 784 (16·4) | 253 (7.5) | < 0·001 |

| Hypertension | 61 350 (27·0) | 1573 (20·7) | < 0·001 | 9040 (27·4) | 1133 (26·8) | 0·20 | 52 310 (27·0) | 440 (13.1) | < 0·001 |

| Heart failure | 9503 (4·2) | 171 (2·3) | < 0·001 | 1547 (4·7) | 141 (3·3) | < 0·001 | 7956 (4·1) | 30 (0·9) | < 0·001 |

| CPD | 70 426 (31·0) | 1500 (19·8) | < 0·001 | 9268 (28·1) | 932 (22·0) | < 0·001 | 61 158 (31·5) | 568 (16·9) | < 0·001 |

The data are presented as n (%) unless stated otherwise. CPD, chronic pulmonary disease. aIncluding Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk‐do.

Association between COVID‐19‐positive test results and skin diseases or use of biologics

No significant increase was seen in the presence of specific skin diseases in the COVID‐19‐positive group (Table 2). After adjusting for age, sex, residence and comorbidities, no skin disease was found to increase the risk of COVID‐19 (Table 3). Subgroup analyses in the Dae‐Gyeong area and other provinces were also consistent with this result (Tables 2 and 3). Similarly, the use of neither single biologics nor classes of biologics showed an increase in susceptibility to COVID‐19.

Table 2.

The rate of the presence of various skin diseases and exposure to biologics according to the results of COVID‐19 testing

| Total | Areas | ||||||||

| Dae‐Gyeong areaa | Other cities and provinces | ||||||||

| COVID‐19 negative | COVID‐19 positive | P‐value | COVID‐19 negative | COVID‐19 positive | P‐value | COVID‐19 negative | COVID‐19 positive | P‐value | |

| n = 226 837 | n = 7590 | n = 32 941 | n = 4234 | n = 193 896 | n = 3356 | ||||

| Skin disease | |||||||||

| Alopecia areata | 1383 (0·6) | 42 (0·6) | 0·54 | 241 (0·7) | 21 (0·5) | 0·085 | 1142 (0·6) | 21 (0·6) | 0·78 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 8640 (3·8) | 180 (2·4) | < 0·001 | 950 (2·9) | 93 (2·2) | 0·011 | 7690 (4·0) | 87 (2·6) | < 0·001 |

| Psoriasis | 1717 (0·8) | 55 (0·7) | 0·75 | 260 (0·8) | 35 (0·8) | 0·78 | 1457 (0·8) | 20 (0·6) | 0·30 |

| Rosacea | 473 (0·2) | 11 (0·1) | 0·23 | 52 (0·2) | 5 (0·1) | 0·68 | 421 (0·2) | 6 (0·2) | 0·64 |

| Vitiligo | 383 (0·2) | 12 (0·2) | 0·82 | 63 (0·2) | 8 (0·2) | 0·97 | 320 (0·2) | 4 (0·1) | 0·52 |

| Biologics | |||||||||

| TNF‐α inhibitors | 339 (0·15) | 3 (0·04) | 0·009 | 50 (0·15) | 1 (0·02) | 0·026 | 289 (0·15) | 2 (0·06) | 0·25 |

| Etanercept | 47 (0·02) | 1 (0·01) | 1·00 | 8 (0·02) | 0 | 0·61 | 39 (0·02) | 1 (0·03) | 0·50 |

| Infliximab | 151 (0·07) | 1 (0·01) | 0·10 | 14 (0·04) | 0 | 0·39 | 137 (0·07) | 1 (0·03) | 0·74 |

| Adalimumab | 132 (0·06) | 1 (0·01) | 0·14 | 27 (0·08) | 1 (0·02) | 0·36 | 105 (0·05) | 0 | 0·43 |

| Golimumab | 14 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 2 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 12 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 |

| IL‐12/23 or IL‐23 inhibitors | 34 (0·01) | 0 | 0·63 | 4 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 30 (0·02) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Ustekinumab | 24 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 2 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 22 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Guselkumab | 11 (< 0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 2 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 9 (< 0·01) | 0 | 1·00 |

| IL‐17 inhibitors | 17 (0·01) | 2 (0·03) | 0·13 | 2 (0·01) | 1 (0·02) | 0·30 | 15 (0·01) | 1 (0·03) | 0·24 |

| Secukinumab | 11 (< 0·01) | 2 (0·03) | 0·065 | 0 | 1 (0·02) | 0·11 | 11 (0·01) | 1 (0·03) | 0·19 |

| Ixekizumab | 6 (< 0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 2 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 4 (< 0·01) | 0 | 1·00 |

| IL‐4/13 inhibitors | 9 (< 0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 1 (< 0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 8 (< 0·01) | 0 | 1·00 |

IL, interleukin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor. aIncluding Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk‐do.

Table 3.

Odds ratios of various skin diseases and exposure to biologics in the COVID‐19‐positive group compared with the COVID‐19‐negative group

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P‐value | |

| Skin disease | ||||||

| Alopecia areata | 0·91 (0·67–1·23) | 0·53 | 0·82 (0·60–1·12) | 0·21 | 0·69 (0·44–1·08) | 0·10 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 0·61 (0·52–0·71) | < 0·001 | 0·76 (0·65–0·88) | < 0·001 | 0·82 (0·66–1·02) | 0·073 |

| Psoriasis | 1·00 (0·77–1·31) | 0·98 | 1·03 (0·78–1·36) | 0·81 | 1·07 (0·75–1·53) | 0·70 |

| Rosacea | 0·68 (0·38–1·24) | 0·21 | 0·80 (0·44–1·48) | 0·48 | 0·75 (0·30–1·87) | 0·53 |

| Vitiligo | 0·92 (0·52–1·64) | 0·78 | 0·86 (0·48–1·54) | 0·60 | 0·95 (0·45–1·98) | 0·89 |

| Biologics | ||||||

| TNF‐α inhibitors | 0·27 (0·088–0·84) | 0·024 | 0·27 (0·087–0·85) | 0·026 | 0·18 (0·024–1·27) | 0·085 |

| Etanercept | 0·64 (0·089–4·63) | 0·66 | 0·66 (0·089–4·91) | 0·68 | NA | 0·93 |

| Infliximab | 0·20 (0·028–1·43) | 0·11 | 0·23 (0·032–1·67) | 0·15 | NA | 0·93 |

| Adalimumab | 0·24 (0·034–1·67) | 0·15 | 0·20 (0·027–1·42) | 0·11 | 0·32 (0·044–2·38) | 0·27 |

| Golimumab | NA | 0·92 | NA | 0·91 | NA | 0·95 |

| IL‐12/23 or IL‐23 inhibitors | NA | 0·92 | NA | 0·89 | NA | 0·95 |

| Ustekinumab | NA | 0·90 | NA | 0·91 | NA | 0·95 |

| Guselkumab | NA | 0·90 | NA | 0·90 | NA | 0·94 |

| IL‐17 inhibitors | 3·53 (0·82–15·3) | 0·092 | 3·56 (0·77–16·6) | 0·11 | 4·21 (0·37–47·8) | 0·25 |

| Secukinumab | 5·44 (1·20–24·6) | 0·028 | 6·87 (1·40–33·8) | 0·018 | NA | 0·93 |

| Ixekizumab | NA | 0·93 | NA | 0·93 | NA | 0·95 |

| IL‐4/13 inhibitors | NA | 0·91 | NA | 0·92 | NA | 0·94 |

CI, confidence interval; IL, interleukin; NA, not applicable; TNF, tumour necrosis factor. Model 1: result of logistic regression after adjustment for age and sex. Model 2: result of logistic regression after adjustment for age, sex, residence, diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure and chronic pulmonary disease. Model 3: result of logistic regression in Daegu and Gyeongsangbuk‐do after adjustment for age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, heart failure and chronic pulmonary disease.

Additional analysis in the propensity‐score‐matched population showed consistent results. We selected two controls matched to a case by propensity score, considering age, sex, residency and comorbidities. After matching, the demographics became comparable between the groups positive and negative for COVID‐19, and no increases in the presence of skin diseases or the use of biologics were found (Tables S1 and S2; see Supporting Information). Furthermore, we built propensity‐score‐matched populations for each class of biologics with a 1 : 10 ratio, and found a consistent result regarding susceptibility to COVID‐19 in patients treated with biologics (Table S3; see Supporting Information).

Association between the clinical outcomes of the COVID‐19‐positive group and skin diseases or use of biologics

Of the patients with COVID‐19, 227 (3·0%) died, and most of them died while hospitalized (218, 96·0%). They were significantly older (mean ± SD 77·1 ± 10·8 years) than those who survived (44·9 ± 19·2 years), and all comorbidities (including diabetes, hypertension, heart failure and CPD) were more common in those who died (P < 0·001 in each) (Table S4; see Supporting Information). Most deaths occurred in the Dae‐Gyeong area (n = 201, 88·5%). In total 7157 patients (94·3%) were admitted to hospital for COVID‐19. Of the inpatients, 216 (3·0%) were admitted to the ICU, and 127 (1·8%) used a ventilator.

No significant association between cases with mortality and the presence of skin disease was observed (Table 4). The hospitalization rate did not increase significantly in patients with skin diseases or in patients exposed to any biologics. In addition, in the COVID‐19‐positive hospitalization group, there was no significant association between skin diseases and ICU admission or ventilator use. In addition, no COVID‐19‐positive patient exposed to biologics had a record of ICU admission, ventilator use or mortality.

Table 4.

Association of clinical outcomes in patients with COVID‐19 with various skin diseases and exposure to biologics

| Mortality (n = 7590) | Admission (n = 7590) | In‐hospital patient with COVID‐19 (n = 7157) | ||||||||||

| Intensive care unit event | Ventilator event | |||||||||||

| Survived | Died | P‐value | Without | With | P‐value | Without | With | P‐value | Without | With | P‐value | |

| n = 7363 | n = 227 | n = 433 | n = 7157 | n = 6941 | n = 216 | n = 7030 | n = 127 | |||||

| Skin disease | ||||||||||||

| Alopecia areata | 42 (0·6) | 0 | 0·64 | 6 (1·4) | 36 (0·5) | 0·016 | 36 (0·5) | 0 | 0·63 | 36 (0·5) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 172 (2·3) | 8 (3·5) | 0·25 | 10 (2·3) | 170 (2·4) | 0·93 | 166 (2·4) | 4 (1·9) | 0·82 | 166 (2·4) | 4 (3·1) | 0·55 |

| Psoriasis | 51 (0·7) | 4 (1·8) | 0·081 | 3 (0·7) | 52 (0·7) | 1·00 | 49 (0·7) | 3 (1·4) | 0·21 | 50 (0·7) | 2 (1·6) | 0·24 |

| Rosacea | 11 (0·1) | 0 | 1·00 | 0 | 11 (0·2) | 1·00 | 11 (0·2) | 0 | 1·00 | 11 (0·2) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Vitiligo | 11 (0·1) | 1 (0·4) | 0·31 | 0 | 12 (0·2) | 1·00 | 12 (0·2) | 0 | 1·00 | 12 (0·2) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Biologics | ||||||||||||

| TNF‐α inhibitors | 3 (0·04) | 0 | 1·00 | 0 | 3 (0·04) | 1·00 | 3 (0·04) | 0 | 1·00 | 3 (0·04) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Etanercept | 1 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 0 | 1 (0·01) | 1·00 | 1 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 1 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Infliximab | 1 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 0 | 1 (0·01) | 1·00 | 1 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 1 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Adalimumab | 1 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 0 | 1 (0·01) | 1·00 | 1 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 | 1 (0·01) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Golimumab | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| IL‐12/23 or IL‐23 inhibitors | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Ustekinumab | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Guselkumab | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| IL‐17 inhibitors | 2 (0·03) | 0 | 1·00 | 0 | 2 (0·03) | 1·00 | 2 (0·03) | 0 | 1·00 | 2 (0·03) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Secukinumab | 2 (0·03) | 0 | 1·00 | 0 | 2 (0·03) | 1·00 | 2 (0·03) | 0 | 1·00 | 2 (0·03) | 0 | 1·00 |

| Ixekizumab | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

| IL‐4/13 inhibitors | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA |

IL, interleukin; NA, not applicable; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

There was a significant difference in hospitalization according to region, with a hospitalization rate of 91·8% in the Dae‐Gyeong area and 97·4% in other areas (P < 0·001). However, the associations between death and sex, age, underlying disease, skin disease and relevant biologics were similar in the two regional groups (Tables S4 and S5; see Supporting Information).

Discussion

The present study is a nationwide analysis of the association between COVID‐19 and dermatological diseases or biologics. The dataset is highly reliable as it captured COVID‐19‐related claim data of the Korean population from both confirmed cases and negative cases, provided by Korean government institutions.

It has been reported that inflammatory cytokines such as TNF‐α and IL‐17 are increased in patients with COVID‐19, which sometimes results in fatal cytokine storms.3, 4, 11 It is well known that immunological mechanisms are important in the pathogenesis of various skin diseases. For example, acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, psoriasis and vitiligo show elevated levels of IL‐17,27 which can play an important role in acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID‐19.28 Thus, it is not unreasonable to suspect that skin diseases with immunological pathogenesis might affect the clinical course of COVID‐19.

However, in this study, patients with any dermatological disease did not show an increased susceptibility to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Among patients with COVID‐19, the presence of any dermatological disease also did not affect the clinical outcome, including ICU admission, ventilator use or mortality. As various comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension and CPD are associated with poor prognosis after COVID‐19,29, 30 we adjusted for these comorbidities, as well as age and sex, and found the same result. This trend was consistent even in the analyses of the propensity‐score‐matched population and subgroups according to the region with an explosive outbreak.

Continuing biologics during the COVID‐19 pandemic is an important issue. Discontinuation of biologics usually results in relapse of skin disease, including psoriasis,31, 32 and some patients are unable to achieve the previous response to biologics.33 The guideline from the American Academy of Dermatology did not recommend discontinuation of biologics without evidence of COVID‐19 infection or reasonable risk.34 Another statement from the European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis also recommended biologics such as dupilumab for atopic dermatitis during the COVID‐19 pandemic, because they are not considered to increase the risk of viral infection.35 However, clinical evidence for continuing biologics for dermatological diseases is insufficient, and there are concerns derived from clinical trials of biologics reporting an increasing risk of various infectious diseases, such as those caused by bacteria and fungi or tuberculosis.19, 36, 37

Recently, a study from a single hospital cohort in Lombardy, Italy reported that the rates of COVID‐19 were higher in patients treated with biologics than in residents in the same province.38 On the other hand, there was no ICU admission or deaths among patients with psoriasis treated with biologics in the same study.38 However, this study from Lombardy is limited because the method of capturing data was different between cases and controls. Furthermore, the differences in demographic characteristics and comorbidities between groups were not considered. Other observational studies from Italy showed no increase in hospitalization due to COVID‐19 and no cases of death from COVID‐19 in patients treated with biological therapy compared with the general population.12, 14, 39 In several cases, dermatological patients receiving biologics were reported to recover from COVID‐19 infection without complications.15–18 The results of the present study, like the other studies mentioned, showed that the use of biologics in dermatological patients may not increase the susceptibility to COVID‐19 and may not lead to injurious clinical outcomes after COVID‐19.

This study had some limitations. Firstly, the data from insurance benefit claims did not include detailed clinical information such as disease severity or lab results. The definition of skin diseases was based on the diagnostic codes, which might cause misclassification of some individuals. Secondly, medications other than biologics were not included in the analysis. Thirdly, there could be racial or ethnic disparities in reference to COVID‐19 infection.40 Fourthly, the number of patients exposed to biologics other than TNF‐α inhibitors was relatively small. Thus, additional research is needed to overcome racial or ethnic disparities and small sporadic reports from across the world. Dermatologists around the world can work together to build case registries to overcome the small sample sizes of dermatological patients with COVID‐19 to inform evidence‐based management practices during the COVID‐19 pandemic.41–43 In addition, even if the skin disease itself does not increase the susceptibility to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, in order to reduce potential exposure of dermatological patients to patients with COVID‐19, it is necessary to reduce nonurgent outpatient visits and consider telemedicine during the COVID‐19 pandemic.42, 44

This study showed that patients with various dermatological diseases or exposure to biologics were not particularly susceptible to COVID‐19 and did not have worse outcomes of COVID‐19 compared with others. Further research needs to be conducted to determine whether these associations are also observed in other population groups. Dermatologists may continue treatment during the COVID‐19 pandemic, taking the patient’s risks and benefits into consideration and following the latest guidelines from dermatology groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the healthcare professionals dedicated to treating patients with COVID‐19 in South Korea, and the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service of Korea for sharing invaluable national health insurance claims data with a lot of effort. We also thank all medical staff fighting COVID‐19 globally.

Author Contribution

Soo ick Cho: Conceptualization (equal); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (equal); Resources (equal); Software (equal); Supervision (supporting); Validation (supporting); Writing‐original draft (lead); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Ye Eun Kim: Conceptualization (supporting); Data curation (supporting); Formal analysis (supporting); Methodology (equal); Supervision (supporting); Writing‐original draft (supporting); Writing‐review & editing (supporting). Seong Jin Jo: Conceptualization (lead); Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (equal); Investigation (equal); Methodology (equal); Project administration (lead); Resources (equal); Software (equal); Supervision (lead); Validation (lead); Writing‐original draft (supporting); Writing‐review & editing (lead).

Supplementary Material

Table S1 Demographics of the population according to the results of COVID‐19 tests, after propensity score matching.

Table S2 The rate of the presence of various skin diseases and exposure to biologics according to COVID‐19 test results after propensity score matching.

Table S3 Comparison of the rates of positive COVID‐19 tests between patients exposed to biologics and propensity‐score‐matched controls.

Table S4 Demographics of the population according to the mortality from COVID‐19.

Table S5 The rate of the presence of various skin diseases and exposure to biologics according to the mortality from COVID‐19.

Powerpoint S1 Journal Club Slide Set.

Contributor Information

S.I. Cho, Department of Dermatology Seoul National University College of Medicine Seoul South Korea

Y.E. Kim, Department of Dermatology Seoul National University College of Medicine Seoul South Korea

S.J. Jo, Department of Dermatology Seoul National University College of Medicine Seoul South Korea.

References

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020; 323:1061–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Fan Y, Lai Y et al. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol 2020; 92:424–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z et al. Dysregulation of immune response in patients with coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19) in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:762–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowes MA, Suarez‐Farinas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis. Annu Rev Immunol 2014; 32:227–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner PM, Guttman‐Yassky E, Leung DY. The immunology of atopic dermatitis and its reversibility with broad‐spectrum and targeted therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139:S65–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boniface K, Seneschal J, Picardo M et al. Vitiligo: focus on clinical aspects, immunopathogenesis, and therapy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018; 54:52–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L et al. Alopecia areata: disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhl T, Sulk M, Nowak P et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of inflammatory infiltrate in rosacea reveals activation of Th1/Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol 2015; 135:2198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price KN, Frew JW, Hsiao JL et al. COVID‐19 and immunomodulator/immunosuppressant use in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82:e173–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X. COVID‐19: immunopathology and its implications for therapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2020; 20:269–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlando M, Carmisciano L, Cozzani E et al. A survey of psoriasis patients on biologics during COVID‐19: a single centre experience. J Dermatolog Treat 2020; 10.1080/09546634.2020.1770165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carugno A, Gambini DM, Raponi F et al. COVID‐19 and biologics for psoriasis: a high‐epidemic area experience – Bergamo, Lombardy, Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 6:292–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisondi P, Facheris P, Dapavo P et al. The impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on patients with chronic plaque psoriasis being treated with biological therapy: the Northern Italy experience. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183:373–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci S, Romagnuolo M, Angileri L et al. Safety of dupilumab in severe atopic dermatitis and infection of Covid‐19: two case reports. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e303–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestri R, Rech G, Girardelli CR. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in a psoriatic patient treated with IL‐17 inhibitor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e357–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina F, Piaserico S. SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in a psoriatic patient treated with IL‐23 inhibitor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e254–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caroppo F, Biolo G, Belloni Fortina A. SARS‐CoV‐2 asymptomatic infection in a patient under treatment with dupilumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schett G, Sticherling M, Neurath MF. COVID‐19: risk for cytokine targeting in chronic inflammatory diseases? Nat Rev Immunol 2020; 20:271–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korean Society of Infectious Diseases, Korean Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Korean Society of Epidemiology et al. Report on the epidemiological features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in the Republic of Korea from January 19 to March 2, 2020. J Korean Med Sci 2020; 35:e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong KH, Lee SW, Kim TS et al. Guidelines for laboratory diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Korea. Ann Lab Med 2020; 40:351–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S, Choi GJ, Ko H. Information technology‐based tracing strategy in response to COVID‐19 in South Korea – privacy controversies. JAMA 2020; 323:2129–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na BJ, Park Y, Huh IS et al. Seventy‐two hours, targeting time from first COVID‐19 symptom onset to hospitalization. J Korean Med Sci 2020; 35:e192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. COVID‐19 screening center: how to balance between the speed and safety? J Korean Med Sci 2020; 35:e157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Shin JY, Kim HJ et al. Chasms in achievement of recommended diabetes care among geographic regions in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2019; 34:e190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Yoon S, Kim LY et al. Towards actualizing the value potential of Korea Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) data as a resource for health research: strengths, limitations, applications, and strategies for optimal use of HIRA data. J Korean Med Sci 2017; 32:718–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini N, Skroza N, Tolino E et al. IL‐17 and its role in inflammatory, autoimmune, and oncological skin diseases: state of art. Int J Dermatol 2020; 59:406–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacha O, Sallman MA, Evans SE. COVID‐19: a case for inhibiting IL‐17? Nat Rev Immunol 2020; 20:345–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). JAMA Cardiol 2020; 5:811–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395:1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu HY, Hui RC, Tsai TF et al. Predictors of time to relapse following ustekinumab withdrawal in patients with psoriasis who had responded to therapy: an eight‐year multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; in press; doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinato F, Girolomoni G, Gisondi P. Relapse of psoriasis in patients who asked to discontinue etanercept after achieving a stable clinical remission. Br J Dermatol 2019; 181:1319–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH et al. Joint AAD‐NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80:1029–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Dermatology. Guidance on the use of biologic agents during COVID‐19 outbreak. Available at: https://assets.ctfassets.net/1ny4yoiyrqia/PicgNuD0IpYd9MSOwab47/023ce3cf6eb82cb304b4ad4a8ef50d56/Biologics_and_COVID‐19.pdf (last accessed 7 September 2020).

- Wollenberg A, Flohr C, Simon D et al. European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD) statement on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐Cov‐2) infection and atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:e241–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan MT, Shin DB, Winthrop KL et al. The risk of respiratory tract infections and symptoms in psoriasis patients treated with IL‐17‐pathway inhibiting biologics: a meta‐estimate of pivotal trials relevant to decision‐making during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83:677–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez DP, Kirsner RS, Lev‐Tov H. Clinical considerations for managing dermatology patients on systemic immunosuppressive and/or biologic therapy during COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83:288–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani G, Pacifico A, Bragazzi NL et al. Biologics increase the risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and hospitalization, but not ICU admission and death: real‐life data from a large cohort during red‐zone declaration. Dermatol Ther 2020; in press; doi: 10.1111/dth.13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisondi P, Zaza G, Del Giglio M et al. Risk of hospitalization and death from COVID‐19 infection in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis receiving a biologic treatment and renal transplant recipients in maintenance immunosuppressive treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83:285–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb Hooper M, Napoles AM, Perez‐Stable EJ. COVID‐19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA 2020; 323:2466–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahil SK, Yiu ZZN, Mason KJ et al. Global reporting of cases of COVID‐19 in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis: an opportunity to inform care during a pandemic. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183:404–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price KN, Thiede R, Shi VY et al. Strategic dermatology clinical operations during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 82:e207–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik HB, Alhusayen R, Frew J et al. Global Hidradenitis Suppurativa COVID‐19 Registry: a registry to inform data‐driven management practices. Br J Dermatol 2020; 183:780–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahmy DH, El‐Amawy HS, El‐Samongy MA et al. COVID‐19 and dermatology: a comprehensive guide for dermatologists. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34:1388–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Demographics of the population according to the results of COVID‐19 tests, after propensity score matching.

Table S2 The rate of the presence of various skin diseases and exposure to biologics according to COVID‐19 test results after propensity score matching.

Table S3 Comparison of the rates of positive COVID‐19 tests between patients exposed to biologics and propensity‐score‐matched controls.

Table S4 Demographics of the population according to the mortality from COVID‐19.

Table S5 The rate of the presence of various skin diseases and exposure to biologics according to the mortality from COVID‐19.

Powerpoint S1 Journal Club Slide Set.