ABSTRACT

Background

Kidney replacement therapy (KRT) conferred a high risk for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) related mortality early in the pandemic. We evaluate the presentation, treatment and outcomes of COVID-19 in patients on KRT over time during the pandemic.

Methods

This registry-based study involved 6080 dialysis and kidney transplant (KT) patients with COVID-19, representing roughly 10% of total Spanish KRT patients. Epidemiology, comorbidity, infection, vaccine status and treatment data were recorded, and predictors of hospital admission, intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mortality were evaluated.

Results

Vaccine introduction decreased the number of COVID-19 cases from 1747 to 280 per wave. Of 3856 (64%) COVID-19 KRT patients admitted to the hospital, 1481/3856 (38%) were admitted during the first of six waves. Independent predictors for admission included KT and the first wave. During follow-up, 1207 patients (21%) died, 500/1207 (41%) during the first wave. Among vaccinated patients, mortality was 19%, mostly affecting KT recipients. Overall, independent predictors for mortality were older age, disease severity (lymphopaenia, pneumonia) and ICU rejection. Among patient factors, older age, male sex, diabetes, KT and no angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) were independent predictors of death. In KT recipients, individual immunosuppressants were independent predictors of death. Over time, patient characteristics evolved and in later pandemic waves, COVID-19 was mainly diagnosed in vaccinated KT recipients; in the few unvaccinated dialysis patients, ICU admissions increased and mortality decreased (28% for the first wave and 16–22% thereafter).

Conclusions

The clinical presentation and outcomes of COVID-19 during the first wave no longer represent COVID-19 in KRT patients, as the pandemic has become centred around vaccinated KT recipients. Vaccines lowered the incidence of diagnosed COVID-19 and mortality. However, mortality remains high despite increased access to ICU care.

Keywords: COVID-19, dialysis, kidney transplant, mortality, SARS-CoV-2

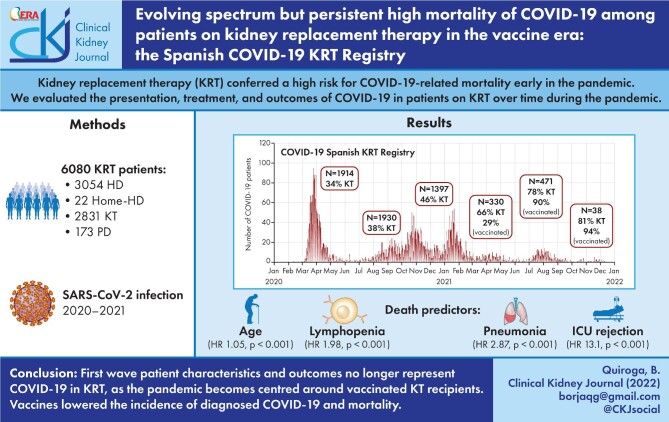

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and, specifically, those needing kidney replacement therapy (KRT) were among those having the highest mortality during the first wave of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, a time when healthcare systems were frequently overwhelmed, limiting access to intensive care units (ICU), empirical therapy was later found to be ineffective and vaccination was not available [1–3]. However, dynamic factors such as new virus variants, decreased saturation of healthcare systems, approval of effective treatments and more importantly, SARS-CoV-2 vaccines may have modified the nature and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in patients on KRT [4].

Specific characteristics of KRT patients may have modified SARS-CoV-2 exposure and outcomes differentially from the general population over time through the pandemic [5]. On one hand, KRT patients present multiple comorbidities and poly-medication that may increase fragility and haemodialysis (HD) patients have limited ability to shield due to their need to access healthcare facilities thrice weekly [6, 7]. On the other hand, KRT patients have been excluded from the prescription of certain drugs and even from mechanical ventilation or ICU admission because of their worse prognosis, especially when healthcare systems were overwhelmed [8]. Finally, the response of kidney transplant recipients (KT recipients) to vaccines may be suboptimal, at least from the point of view of antibody development [9]. Only an analysis of presentation and outcomes of COVID-19 in KRT patients over the successive pandemic waves may identify persistent risk factors for adverse outcomes as well as characterizing the current prognosis of patients with CKD on KRT.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the dynamic presentation features and outcomes across the six waves of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Spain in a registry-based population of patients on KRT. As Spain was one of the earliest and hardest-hit countries and currently is one of the countries with the highest uptake of vaccines (80% of the total population on 29 December 2021), changes over time in Spain may be of special interest to understand the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and healthcare measures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Spanish COVID-19 KRT Registry is an initiative of the Spanish Society of Nephrology open to all nephrology and dialysis centres in Spain. It was set up on 18 March 2020 with a prospective design. It includes all patients treated with in-centre HD, home HD (HHD), peritoneal dialysis (PD) or kidney transplant recipients (KT recipients) that have developed a confirmed SARS-Cov-2 infection. Diagnosis of COVID-19 was based on the positivity of one of the following tests: reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), rapid antigen tests or SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike antibodies before vaccination.

This analysis included the full cohort until 12 December 2021. During follow-up, local coordinators were asked to immediately report cases from their centres through a centralized web page (www.senefro.org) only accessible to registered users. Until now, the Spanish Public Health Institute has defined six pandemic waves [10], according to the following dates: first wave from 31 January 2020, second wave from 1 July 2020, third wave from 1 December 2020, fourth wave from 1 March 2021, fifth wave from 1 June 2021 and sixth wave from 1 November 2021. These dates were used for the present analysis.

Variables

At baseline, epidemiological factors (sex and age), KRT (KT, HD, PD and HHD), KRT vintage and cause of CKD, concomitant treatments [angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID)] and immunosuppressive drugs were recorded.

At diagnosis, symptoms, lymphopaenia (total lymphocyte count <500/mm3) and pneumonia were registered. Prescribed medications for SARS-CoV-2 infection and, in KT, the need for adjustment of immunosuppressants were also collected. Invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation was registered.

Vaccination

In Spain, the SARS-CoV-2 vaccination started on 27 December 2020. The following four vaccines have been used: BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech®), mRNA-1273 (Moderna®), ChAdOx1-S (AstraZeneca®) or Ad26.COV.2 (Janssen®) [9]. Prescription of individual vaccines was guided by local public health authorities and mainly driven initially by vaccine availability and later by successive modifications of the age range for ChAdOx1-S. Vaccination status was collected during the present study and considered when the full vaccination schedule was completed before SARS-CoV-2 infection. The course of the first full (i.e. two doses except for Ad26.COV.2) vaccine schedule was uneven, as decisions were taken at the regional level and not all regions assigned the same priority to patients on KRT or to the different KRT modalities. However, for KRT patients, it was generally completed in the first semester of 2021 [9]. The booster dose was generally administered to KRT patients from October to early November 2021, i.e., before the sixth wave.

Outcomes

During follow-up, the following outcomes were registered in patients infected by SARS-CoV-2: admission to hospital, intensive care unit (ICU) admission and mortality. Investigators could report that patients had been rejected for ICU admission.

Ethics

The registry was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee of Asturias.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median [interquartile range (IQR)] depending on the distribution of the variables, tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher test and continuous variables with t-test or Mann–Whitney, according to the variable distribution. For comparison of continuous variables from more than two groups, ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used.

Univariate logistic regressions were performed for assessing associations between the outcomes (admission, ICU admission and mortality) and the registered variables. To identify factors associated with admission, ICU admission and mortality differentially over time, two different analyses were performed. The first analysis compared the first with subsequent waves. The rationale is that the first wave differed from other waves in several aspects: the healthcare system was overwhelmed, health authorities were advising against the widespread use of face masks, and there was use of potentially toxic ineffective drugs and a lack of awareness about the need to prevent thrombosis. The second analysis compared the first three waves with the subsequent waves. The rationale is to compare the waves before and after vaccine availability.

Multivariate regression models were adjusted for variables with P < .1 in univariate analyses and those considered confounders.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

A total of 6080 KRT patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection were included (36% female, age 63 ± 15 years). Among them, 2832 (46%) were KT recipients, 3063 (50%) were on in-centre HD, 173 (3%) on PD and 22 (<1%) on HHD. Prior to infection, 501 (8%) patients had received a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (Table 1). Baseline characteristics for the successive pandemic waves are shown in Table 1. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was common among those infected in the fifth and sixth waves. Differences between KRT modalities are shown in Supplementary data, Table S1. SARS-CoV-2-infected KT recipients were younger but had longer KRT vintage than HD patients and also had a higher rate of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, infection related variables and outcomes in different waves

| Total (n = 6080) | First (n = 1914) | Second (n = 1930) | Third (n = 1397) | Fourth (n = 330) | Fifth (n = 471) | Sixth (n = 38) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male), n (%) | 3901 (64) | 1236 (64) | 1226 (63) | 901 (65) | 204 (62) | 312 (66) | 22 (58) | .719 |

| Age (years) | 63 ± 15 | 67 ± 14 | 62 ± 15 | 64 ± 15 | 60 ± 14 | 58 ± 15 | 60 ± 15 | <.001 |

| Diabetic kidney disease, n (%) | 1199 (21) | 408 (25) | 378 (21) | 282 (21) | 56 (17) | 72 (16) | 3 (8) | <.001 |

|

KRT, n (%): KT HD PD HHD |

2831 (47) 3054 (50) 173 (3) 22 (<1) |

648 (34) 1198 (63) 62 (3) 6 (<1) |

922 (48) 946 (49) 52 (3) 10 (<1) |

644 (46) 703 (5) 46 (3) 4 (<1) |

217 (66) 108 (33) 5 (1) 0 (0) |

369 (78) 93 (20) 7 (1) 2 (0) |

31 (81) 6 (16) 1 (3) 0 (0) |

<.001 |

| Haemodialysis unit location (external), n (%) | 1460 (53) | 488 (48) | 462 (52) | 392 (58) | 55 (52) | 61 (68) | 2 (40) | <.001 |

| KRT vintage (months) | 44 (17–95) | 38 (15–83) | 45 (17–97) | 45 (18–97) | 48 (18–110) | 53 (19–111) | 60 (61–101) | <.001 |

|

Symptoms at onset, n (%) Asymptomatic Fever Cough/rhinorrhoea Dyspnoea Gastrointestinal |

1225 (22) 3525 (60) 3512 (60) 2196 (39) 1279 (23) |

259 (15) 1300 (71) 1161 (63) 742 (43) 424 (24) |

498 (28) 1037 (56) 1004 (54) 629 (35) 419 (23) |

339 (26) 677 (50) 792 (59) 492 (38) 236 (18) |

58 (19) 188 (59) 212 (67) 130 (42) 71 (23) |

68 (16) 298 (66) 319 (71) 193 (44) 120 (27) |

3 (9) 25 (68) 24 (69) 10 (29) 9 (26) |

<.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 |

| Lymphopenia, n (%) | 3584 (63) | 1358 (75) | 1037 (57) | 725 (56) | 196 (63) | 257 (58) | 11 (38) | <.001 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 3148 (53) | 1260 (68) | 843 (45) | 616 (45) | 179 (56) | 238 (52) | 12 (39) | <.001 |

| Hospital admission, n (%) | 3856 (64) | 1481 (78) | 1104 (58) | 757 (55) | 207 (64) | 292 (63) | 15 (47) | <.001 |

| ICU admission, n (%)a | 561 (15) | 127 (9) | 179 (17) | 123 (17) | 39 (19) | 90 (32) | 3 (21) | <.001 |

| ICU rejection, n (%)a | 431 (12) | 208 (16) | 77 (7) | 109 (16) | 15 (8) | 19 (7) | 1 (8) | <.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%)a | 656 (19) | 210 (17) | 170 (17) | 143 (22) | 46 (25) | 84 (31) | 3 (23) | <.001 |

|

Treatment at onset, n (%) lopinavir/ritonavir Hydroxychloroquine Interferon Tocilizumab Steroids No treatment |

611 (12) 1425 (27) 60 (4) 468 (9) 2565 (48) 1740 (35) |

596 (35) 1419 (80) 5 (<1) 172 (11) 587 (35) 253 (16) |

9 (1) 5 (<1) 0 (0) 132 (8) 862 (50) 705 (44) |

1 (<1) 1 (<1) 0 (0) 79 (7) 661 (53) 539 (45) |

0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 33 (11) 183 (61) 92 (32) |

5 (1) 0 (0) 0 (0) 52 (14) 261 (63) 135 (34) |

0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 0 (0) 11 (41) 16 (57) |

<.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 |

| Baseline ACEi, n (%) | 768 (13) | 231 (12) | 246 (13) | 158 (12) | 49 (15) | 80 (18) | 4 (11) | .014 |

| Baseline ARB, n (%) | 1343 (23) | 384 (21) | 455 (24) | 317 (24) | 72 (23) | 106 (24) | 9 (25) | .181 |

| Previous NSAID, n (%) | 181 (3) | 63 (3) | 61 (3) | 43 (3) | 6 (2) | 7 (2) | 1 (3) | .326 |

|

Immunosuppression, n (%) Prednisone Ciclosporin Tacrolimus Mycophenolate mTORi Azathioprine |

2268 (81) 3 (<1) 2449 (95) 1945 (76) 412 (16) 29 (1) |

461 (74) 0 (0) 511 (92) 382 (69) 124 (22) 8 (1) |

745 (82) 0 (0) 814 (96) 654 (77) 114 (13) 11 (1) |

531 (83) 2 (<1) 564 (96) 446 (76) 93 (16) 3 (<1) |

181 (83) 1 (<1) 198 (97) 156 (76) 35 (17) 3 (1) |

323 (89) 0 (0) 333 (96) 281 (81) 44 (13) 3 (1) |

27 (90) 0 (0) 29 (100) 23 (79) 2 (7) 1 (3) |

<.001 .219 .006 .001 <.001 .470 |

| SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, n (%) | 500 (8%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 (1) | 66 (20) | 396 (84) | 30 (79) | <.001 |

| Immunosuppressants adjusted, n (%) | 458 (65) | 13 (72) | 16 (42) | 78 (60) | 88 (69) | 246 (67) | 17 (81) | .015 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1207 (21) | 500 (28) | 292 (16) | 265 (20) | 52 (17) | 94 (22) | 4 (19) | <.001 |

| Mortality in vaccinated, n (%) | 86 (19) | NA | NA | 1 (12) | 8 (12) | 75 (21) | 2 (15) | .382 |

| Mortality in symptomatic patients, n (%) | 1010 (25) | 412 (30) | 244 (20) | 225 (25) | 46 (20) | 80 (25) | 3 (19) | <.001 |

a% of admitted.

Data are displayed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) unless otherwise indicated. KRT; kidney replacement therapy, KT, kidney transplant; HD, in-centre haemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis; HHD, home haemodialysis; ICU, intensive care unit; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB: angiotensin receptor blockers; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; mTORi, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors; NA, not applicable.

Regarding immunosuppressive drugs, KT recipients were mostly receiving prednisone (81%), tacrolimus (95%) and mycophenolate (76%) for chronic immunosuppression before developing COVID-19 (Table 1). The chronic immunosuppressive medication of KT recipients that were diagnosed with COVID-19 evolved during the pandemic: over time the percentage of patients on prednisone (P < .001), tacrolimus (P = .006) and mycophenolate (P = .001) increased and the percentage of patients on mTORi inhibitors (P < .001) decreased. Most of these differences were evident between the first and subsequent waves (Supplementary data, Table S2). However, only prednisone was significantly more frequent for chronic immune suppression during the vaccine era (Supplementary data, Table S2). In fact, chronic immune suppression with prednisone was observed in 80% of KT recipients before vaccines became available (waves 1–3) and in 88% in waves 4–5, when over 85% of KT recipients with SARS-CoV-2 infection were vaccinated.

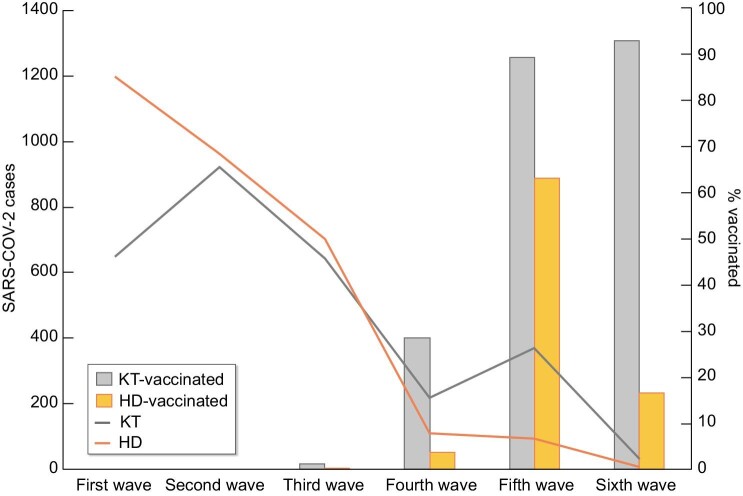

Changing patterns of SARS-CoV-2 infection and treatment

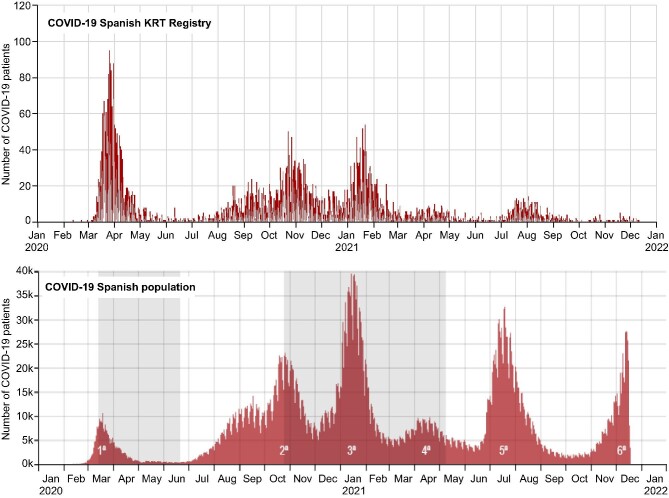

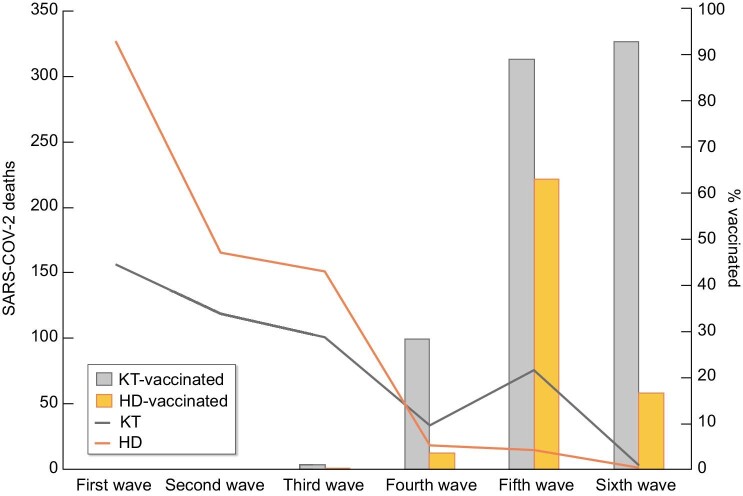

Figure 1 shows the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Spanish COVID-19 KRT Registry and in the general Spanish population [3]. In the KRT cohort, more SARS-CoV-2 infections occurred during the first wave than in subsequent waves (P < .001), unlike in the general population. The pandemic affected more frequently in-centre HD patients in the initial wave and KT recipients from the fourth wave, i.e. after the vaccine had become available (Fig. 2) (Supplementary data, Tables S2 and S3). Following the availability of vaccines, the number of COVID-19 cases among KRT patients decreased dramatically. However, an interesting pattern is observed in which most COVID-19 cases in KT recipients in the fifth and sixth waves occurred among vaccinated persons, while in the sixth wave, i.e. after the booster had been offered, most infections in HD occurred in unvaccinated patients.

FIGURE 1:

SARS-CoV-2 infections over time in the COVID-19 Spanish KRT Registry and in the general Spanish population during the pandemic.

FIGURE 2:

SARS-CoV-2 cases and vaccination status among kidney transplant recipients and haemodialysis. Continuous lines refer to total cases in the different cohorts. Bars indicate the percentage of vaccination among infected patients. KT, kidney transplant; HD, haemodialysis.

Symptoms varied across waves. A total of 1025 (22%) patients were asymptomatic and the frequency increased from the first wave (15%) to the second and third wave (28% and 26%, respectively), likely representing changes in HD units screening patterns, and then decreased to 9% (P < .001). In this regard, KT recipients and patients on PD were less likely to be asymptomatic (P < .001) and had higher rates of pneumonia (P < .001) (Supplementary data, Table S1). A total of 3148 (53%) patients developed pneumonia (Table 1). The most common symptoms were fever (60%) and cough/rhinorrhoea (60%).

The prescription of drugs to treat COVID-19 changed during the pandemic. Lopinavir/ritonavir (35%) and hydroxychloroquine (80%) were used only in the first wave and then became obsolete (P < .001 for both). Steroids (48%) were the most frequent treatment initiated for the cytokine storm phase of COVID-19, while 35% of patients were untreated (Table 1). KT recipients were treated more frequently with drugs targeting the cytokine storm (i.e. steroids or tocilizumab) than the other cohorts (P < .001 for both) (Supplementary data, Table S1).

Among KT recipients, 458 (65%) required an adjustment of immunosuppressive treatment during the infection, the most common being a reduction or withdrawal of mycophenolate in 384 (98%), followed by a reduction in calcineurin inhibitors [tacrolimus in 232 (68%) patients, cyclosporine in 5 (20%)] and an increase in steroid dose in 289 (82%) patients. A decrease/withdrawal of mTOR inhibitors was uncommon (3 patients, 5%).

Factors associated with admission

Among infected patients, 3856 (64%) were admitted to hospital. Factors associated to admission are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factors associated with outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection in univariate analysis

| Hospital admission | ICU admission | Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Sex (male) | 1.30 (1.17–1.45) | <.001 | 1.13 (0.93–1.36) | .226 | 1.25 (1.10–1.43) | .001 |

| Age (per year) | 1.02 (1.02–1.03) | <.001 | 0.97 (0.96–0.97) | <.001 | 1.06 (1.05–1.06) | .001 |

| Diabetic kidney disease (yes) | 1.39 (1.21–1.59) | <.001 | 0.82 (0.65–1.03) | .093 | 1.43 (1.23–1.66) | <.001 |

| KRT (KT) | 1.15 (1.03–1.28) | .010 | 3.75 (3.07–4.59) | <.001 | 0.73 (0.64–0.83) | <.001 |

| Haemodialysis unit location (in-centre) | 0.76 (0.65–0.89) | .001 | 0.98 (0.68–1.42) | .932 | 1.02 (1.00–1.44) | .045 |

| KRT vintage (per month) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | .331 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | .055 | 1.00 (0.99–1.00) | .871 |

| Lymphopaenia (yes) | 15.1 (13.3–17.3) | <.001 | 3.75 (2.59–5.42) | <.001 | 6.52 (5.35–7.95) | <.001 |

| Pneumonia (yes) | 104 (82–132) | <.001 | 11.6 (6.80–19.9) | <.001 | 10.7 (8.8–13.07) | <.001 |

|

Treatment during admission (yes): Lopinavir/ritonavir Hydroxychloroquine Interferon Tocilizumab Steroids |

– – – – – |

– – – – – |

28.0 (16.1–48.7) 7.05 (5.84–8.51) 33.7 (4.67–243) 93.3 (29.9–290) 26.1 (21.5–31.7) |

<.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 |

2.34 (1.95–2.83) 1.83 (1.58–2.12) 3.52 (2.15–5.76) 2.98 (2.43–3.65) 3.49 (3.02–4.04) |

<.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 <.001 |

| Baseline ACEi (yes) | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) | .265 | 1.11 (0.85–1.44) | .431 | 0.92 (0.76–1.12) | .39 |

| ACEi withdrawal at admission (yes) | – | – | 2.94 (1.68–5.15) | <.001 | 5.09 (3.17–8.19) | <.001 |

| Baseline ARB (yes) | 0.88 (0.77–0.99) | .047 | 1.47 (1.19–1.81) | <.001 | 0.75 (0.63–0.88) | <.001 |

| ARB withdrawal at admission (yes) | – | – | 3.43 (2.28–5.17) | <.001 | 4.38 (3.08–6.21) | <.001 |

| Previous NSAID (yes) | 1.06 (0.77–1.45) | .701 | 0.19 (0.07–0.53) | .001 | 0.95 (0.65–0.14) | .805 |

|

Immunosuppressive medication (yes) Prednisone-free regimen CNI-free regimen mTORi-free regimen Mycophenolate-free regimen |

0.82 (0.69–0.99) 1.39 (0.93–2.10) 0.86 (0.68–1.08) 1.15 (0.95–1.39) |

.046 .110 .199 .148 |

0.71 (0.52–0.97) 0.78 (0.45–1.36) 1.56 (1.11–2.19) 0.56 (0.42–0.75) |

.030 .380 .011 <.001 |

0.78 (0.59–1.02) 1.18 (0.74–1.89) 1.51 (1.10–2.07) 0.87 (0.67–1.11) |

.075 .480 .011 .260 |

| SARS-CoV-2 wave (first) | 2.61 (2.30–2.96) | <.001 | 0.41 (0.33–0.51) | .001 | 1.74 (1.53–1.99) | <.001 |

| ICU admission (yes) | – | – | – | – | 3.78 (3.13–4.58) | <.001 |

| ICU rejection (yes) | – | – | – | – | 17.0 (12.9–22.3) | <.001 |

| Vaccination status (yes) | 0.89 (0.74–1.09) | .261 | 2.74 (2.09–3.58) | <.001 | 0.88 (0.69–1.13) | .315 |

The increased OR of UCI admission in univariate analysis among the vaccinated appears to be related to the availability of vaccines in most recent pandemic waves, in which ICU access was easier than in previous waves when the healthcare system was overwhelmed.

KRT; kidney replacement therapy; KT, kidney transplant; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB; angiotensin receptor blockers; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; CNI, calcineurin inhibitors; mTORi, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; OR (95%CI), odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

A total of 658 (11%) patients required mechanical ventilation. Mechanical ventilation use increased over time (P < .001) (Table 1), potentially reflecting improved capacities of healthcare facilities to absorb the case load.

In multivariate analysis, patient (older age, male sex, KT recipient), COVID-19 severity (baseline lymphopaenia, pneumonia) and pandemic (first wave) factors were independent predictors for admission (Table 3). Sensitivity analyses exploring different pandemic wave categories yielded similar results (Supplementary data, Tables S4 and S5).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression for outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Hospital admission | ICU admission | Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age (per year) | 1.01 (1.01–1.02) | <.001 | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | <.001 | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | <.001 |

| Sex (male) | 1.21 (1.01–1.46) | .034 | – | – | – | – |

| KRT (KT) | 1.81 (1.46–2.23) | <.001 | 2.90 (2.28–3.68) | <.001 | – | – |

| Lymphopenia (yes) | 5.58 (4.64–6.65) | <.001 | 3.23 (2.16–4.82) | <.001 | 1.98 (1.48–2.64) | <.001 |

| Pneumonia (yes) | 50.7 (39.4–65.4) | <.001 | 16.9 (8.64–33.4) | <.001 | 2.87 (2.15–3.83) | <.001 |

| KRT vintage (month) | – | – | 0.99 (0.99–0.99) | .008 | – | – |

| SARS-CoV-2 wave (first) | 1.57 (1.28–1.93) | <.001 | 0.43 (0.34–0.54) | <.001 | – | – |

| ICU rejection (yes) | – | – | – | – | 13.1 (9.81–17.5) | <.001 |

Models adjusted for diabetic kidney disease. KRT, kidney replacement therapy; KT, kidney transplant; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; OR (95% CI): odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

Factors associated with ICU admission

Among infected patients, 562 (9%) were admitted to ICU, corresponding to 15% of patients admitted to hospital. In 439 patients (7%) were rejected from ICU admission despite severity criteria for ICU admission. The pattern of ICU admissions also evolved during the pandemic, being lower during the first wave (in which rejection from ICU was higher), likely reflecting overwhelmed healthcare systems (Supplementary data, Table S2).

Factors associated with ICU admission are summarized in Table 2. Multivariate analysis identified patient (younger age, KT recipient, shorter KRT vintage), COVID-19 severity (baseline lymphopaenia, pneumonia) and pandemic (infection outside the first wave) factors as independent predictors for ICU admission (Table 3). Sensitivity analyses exploring different pandemic wave categories yielded similar results (Supplementary data, Tables S6 and S7).

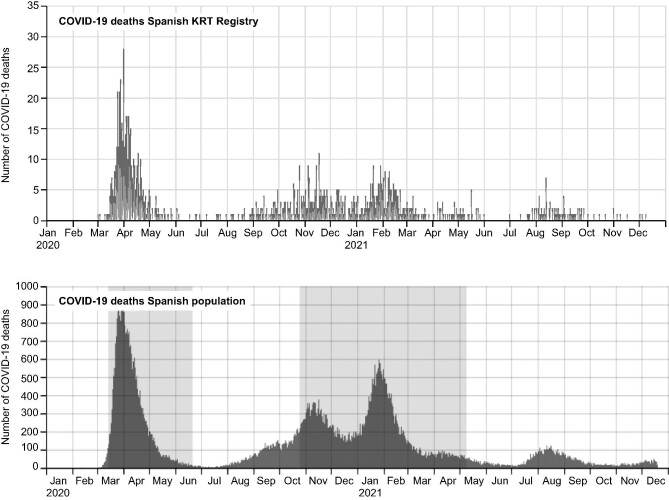

Factors associated with mortality

During follow-up, 1207 patients (21%) died, 4539 (74%) recovered and 344 (6%) were lost to follow-up. Figure 3 shows the mortality in the Spanish COVID-19 KRT Registry and COVID-19 mortality in the general Spanish population [3]. COVID-19 mortality among KRT patients was more frequent during the first wave (28%) than in other waves (18%) (P < .001) (Supplementary data, Table 2) and grossly paralleled those of the general population. From the fourth wave, i.e. after vaccines became available, the number of deaths decreased dramatically and occurred mainly in KT recipients (Fig. 4). However, among breakthrough diagnosed with COVID-19 in the vaccinated, mortality was 19% (Table 1). Of the 86 vaccinated KRT patients that died, a majority (77, 89%) were KT recipients (Supplementary data, Table 1).

FIGURE 3:

COVID-19 mortality over time in the COVID-19 Spanish KRT Registry and in the general Spanish population during the pandemic.

FIGURE 4:

SARS-CoV-2 deaths and vaccination status among kidney transplant recipients and haemodialysis patients. Continuous lines refer to total deaths in the different cohorts. Bars indicate the percentage of vaccination among patients dying from COVID-19. KT, kidney transplant; HD, haemodialysis.

COVID-19 mortality was higher in HD and PD (24 and 22%, respectively) than in KT (18%) or HDD (14%) patients (P < .001). Patient (male sex, older age, diabetic kidney disease, in-centre HD), COVID-19 severity (baseline lymphopaenia, pneumonia), COVID-19 treatment (ACEi and ARB withdrawal, ICU rejection) and pandemic (first wave) factors were also associated to mortality.

In multivariate analysis, patient factors (older age), COVID-19 severity (baseline lymphopaenia, pneumonia) and COVID-19 treatment (ICU rejection) factors were independent predictors of mortality (Table 3). Sensitivity analyses exploring different pandemic wave categories yielded similar results (Supplementary data, Tables S8 and S9).

While COVID-19 severity is an expected driver of mortality, the identification of additional patient factors associated with mortality, potentially by increasing disease severity, may be of interest. Focussing only on patient factors, multivariate analysis identified older age, male sex, diabetes and KT as independent risk factors for death, while ARB use was protective (Supplementary data, Table S10). An analysis focussed on KT recipient factors confirmed the higher risk conferred by older age, male sex and diabetes and, additionally, identified an association with immunosuppressants: mTORi-free and calcineurin inhibitor-free regimens were associated with mortality, while prednisone-free regimens were associated with lower mortality (Supplementary data, Table S11).

DISCUSSION

The key finding of our study is that, although lower than in the first wave, the mortality of KRT patients diagnosed with COVID-19 remains high (around 19% for vaccinated KRT patients) despite advances in treatment and higher availability of ICU care in the era of vaccines. This is 13-fold higher than the 1.55% mortality of confirmed COVID-19 in the general population in Spain [11]. However, the vaccine era witnessed a dramatic decrease in the number of diagnosed COVID-19 cases in the KRT population as compared with the general population, as well as in the absolute number of deaths, and mortality of vaccinated KRT patients was for the most part limited to KT recipients. Thus, a shift was observed from HD patients to KT recipients, for both cases and deaths, likely reflecting the lower efficacy of vaccines in KT recipients [9]. In this regard, the increased prevalence of chronic immunosuppressive regimens containing steroids among COVID-19-infected KT recipients over time should be considered in the context of reports that associate chronic immunosuppressive regimens containing steroids with poorer humoral responses to vaccines [9]. In contrast, almost half of the HD patients infected in the fifth wave and most of the few HD patients infected in the sixth wave were unvaccinated, supporting the efficacy of booster vaccine doses in this population.

Several changes in the presentation, treatment and outcomes of COVID-19 were evident over time and through the successive pandemic waves. One of the most striking features was the shift in the KRT patient population with COVID-19. The first wave mainly affected HD patients while the fifth and sixth waves, following vaccination, were the KT recipient waves. In the first wave, the healthcare system was unprepared to prevent the spread of the virus, but HD patients needed to access healthcare facilities thrice weekly and could not shield themselves [7, 12, 13, 14]. The more recent shift to KT recipients appears related to their suboptimal response to vaccines [9]. In this regard, although the case fatality ratio was similar among vaccinated KT recipients and vaccinated HD patients, there were 8.5-fold more deaths among vaccinated KT recipients than among vaccinated HD patients, likely reflecting the higher number of breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections despite vaccination in KT recipients. To put these data into perspective, the number of KT recipients with functioning grafts in Spain is 1.35-fold higher than the number of patients on HD [15].

A key finding is a potential role of therapeutic nihilism in the high mortality of KRT patients during the first COVID-19 wave, especially among HD and PD patients. In this regard, KT recipients were admitted more frequently, with more symptoms and more frequent pneumonia and received more ICU care, but mortality was lower than in PD or HD patients. Multivariate analysis identified refusal of ICU care as an independent risk factor for death, among other patient and disease severity factors. Difficult decisions had to be made early in the COVID-19 pandemic when ICUs were overwhelmed. This observation is confirmed in our data, where young patients were more frequently accepted for ICU admission. However, we should strive to prevent the rejection of KRT patients during the first pandemic wave becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy and KRT patients being refused advanced life support in the future because of that earlier high mortality. Indeed, our data show that KRT patients with COVID-19 during the first wave were 2.3-fold less likely to be admitted to ICUs than in subsequent waves. In this regard, in the most recent pandemic waves, when vaccines are available and therapies such as dexamethasone are widely used [16], most KRT patients with breakthrough COVID-19 survived. Moreover, in KRT patients, unlike in the general population, additional comorbidities, such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease and chronic lung disease, do not further add to the risk of death and the impact of older age on the risk of death is up to 6-fold lower than in the general population [1, 3].

Beyond access to advanced life support, other treatment factors may influence the risk of death. In addition to the prescription of antivirals or steroids, adjustment of chronic immunosuppression could be a successful strategy in KT recipients. In this regard, mTORi-free and calcineurin inhibitor-free regimens were associated with higher mortality, while steroid-free regimens were consistently associated with lower hospital admissions, lower ICU admissions and lower mortality. Data on the prevalence of chronic immunosuppressive regimens containing steroids among infected KT recipients over time also points to the negative impact of steroids-containing immune suppressive regimens on sensitivity to COVID-19 and also, to severe and potentially lethal COVID-19. This may be, at least in part, related to reports that associate steroids-containing immunosuppressive regimens with poorer humoral responses to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines [9]. Interestingly, steroids are beneficial when used acutely in COVID-19 [17]. This controversy can be understood in light of the anti-inflammatory effect of high doses of corticosteroids on the cytokine storm phase of COVID-19, in contrast to the chronic immunosuppression with steroids prescription that may dampen antiviral and vaccine responses. Regarding acute steroid prescription, an indication bias should be noted, as they were prescribed to treat severe COVID-19, and we believe that this underlies the association with mortality. Among other pre-existent therapies, baseline use of ARBs was a patient factor associated with lower mortality in the full KRT population, albeit not in KT recipients. While this should be confirmed in a wider KRT population, there is biological plausibility for the relationship, since angiotensin receptor-1 (AT-1), the target of ARBs, was recently shown to facilitate SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells mediated by soluble angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (sACE2) [18]. Thus, ARBs could potentially interfere with this port of entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells and we can only speculate that, based on the clinical observation, this viral entry pathway may be more relevant in dialysis patients. This hypothesis merits being pursued in further research as it may be clinically relevant.

The main impact of vaccines appeared to be the reduction in the number of cases, as mortality among vaccinated KRT patients diagnosed with COVID-19 was similar to among non-vaccinated KRT patients diagnosed with COVID-19. However, mortality among vaccinated COVID-19 patients was almost exclusively found in KT recipients, pointing to a suboptimal response to vaccination in those patients who died despite vaccination. Thus, as the pandemic shifts from the wider KRT population to vaccinated KT recipients, the urge to optimize the vaccination regimens increases. This may imply transient adaptation of immune suppression regimens, more common use of the mRNA-1273 vaccine, additional booster doses or novel vaccines [9].

The presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the case fatality ratio may have been influenced by the criteria used to perform diagnostic tests. Thus, early in the pandemic, testing seemed to be reserved for more symptomatic patients, given supply chain issues. Later, testing of even asymptomatic patients was performed in HD units for outbreak monitoring, but not in at-home dialysis or KT recipients [19, 20]. This may explain the lower likelihood of being asymptomatic and higher rates of pneumonia in KT recipients and PD patients. Indeed, asymptomatic infections in the second and third waves were 26–28% and decreased to ˂20% when the epidemiological context changed and preventive screening protocols became outdated. However, the combination of strictly observed isolation measures (e.g. masks during transport to and from dialysis centres and during HD sessions) and vaccines appears to be more effective in the KRT population than vaccines in combination with more relaxed measures in the general population, as judged by the lower number of infections recorded upon vaccine implementation in KRT patients than in the general population. Thus, vaccination and booster doses should continue to be promoted in KRT patients and isolation measures should be maintained. In this regard, early in the pandemic lack of face masks during transport to and from dialysis and suboptimal personal protective equipment were identified as risk factors for infection in KRT patients and healthcare personnel [7, 11, 12].

Some limitations should be acknowledged. In this registry-based study, inherent bias includes some incomplete data, limited variables (such as body mass index or treatment duration) or loss of follow-up. However, first, this is a multicentric prospective study involving a large cohort of patients on KRT infected by SARS-CoV-2 in Spain, corresponding to roughly 10% of Spanish patients on KRT [12], so data and conclusions are thought to be representative. Second, information on vaccination dates or antibody response is not available. In Spain, the first vaccine dose was administered at the end of December 2020, but widespread vaccination started in January 2021 and reached KRT patients at some point between February and April 2021. Third, subclinical or asymptomatic infections probably went unnoticed, especially beyond the third wave, when systematic periodic screening of HD units was no longer performed, so the studied outcomes could be overestimated. However, this makes the data more comparable to the general population, for which widespread screening of asymptomatic individuals is not performed [15]. Fourth, the sixth wave data predate the introduction and expansion of the Omicron variant in Spain and thus, the impact of this strain is not reflected in the data. Finally, some variables, such as rejection from ICU admission, did not have a universal definition and should be analysed from a subjective point of view.

In conclusion, the features of the COVID-19 pandemic in KRT patients (patient characteristics, treatment and outcomes) keep evolving, shifting towards vaccinated KT recipients and unvaccinated dialysis patients. Vaccines are associated with a lower incidence of diagnosed COVID-19, but mortality remains high despite ICU care, although most patients survive. Further improvement in KRT patient outcomes may be obtained by optimizing vaccination and immune suppression protocols in KT recipients, promoting vaccination and boosting dialysis patients and providing access to life support care if needed.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank all the implicated Spanish centres for their altruist collaboration. A.O. research is supported by FIS/Fondos FEDER [PI18/01366, PI19/00588, PI19/00815, DTS18/00032, ERA-PerMed-JTC2018 (KIDNEY ATTACK AC18/00064 and PERSTIGAN AC18/00071, ISCIII-RETIC REDinREN RD016/0009)], Sociedad Española de Nefrología, FRIAT, Comunidad de Madrid en Biomedicina B2017/BMD-3686 CIFRA2-CM. Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) RICORS program to RICORS2040 (RD21/0005/0001), FEDER funds.

APPENDIX

The Spanish COVID-19 KRT Registry collaborative group:

| Victoria Oviedo |

| Antoni Bordils Gil |

| Maria Luisa Navarro López |

| María Isabel Martínez Marín |

| Amparo Bernat García |

| Isabel Berdud Godoy |

| Mª Victoria Guijarro Abad |

| María del Mar Rodríguez de Oña |

| Elena Vaquero Párrizas |

| María Antonia Fernández Solís |

| Jose Antonio Gomez Puerta |

| Alvaro Ossorio Anaya |

| Elena Calvo |

| Carmen Cabré Menéndez |

| Nuria García Fernández |

| Paloma Leticia Martín Moreno |

| Mª José Fernández-Reyes Luis |

| Cristina Lucas Álvarez |

| Guadalupe Tabernero fernández |

| Manuel Heras Benito |

| Pilar Fraile Gómez |

| Joaquin Manrique Escola |

| Enrique Pelaez Perez |

| Luz María Cuiña Barja |

| Teresa Cordal Martinez |

| Maria Jesus Castro Vilanova |

| Silvia Moreno Loshuertos |

| Francisco Javier Ahijado Hormigos |

| Ana Roca Muñoz |

| Carlos Jesús Cabezas Reina |

| Jesús Grande Villoria |

| Ana Isabel Díaz Mareque |

| Anabertha Narváez Benítez |

| Argimiro Gándara Martínez |

| Mª Gloria Rodríguez Goyanes |

| Maria Crucio Lopez |

| Alfonso Iglesias |

| Laureano Perez Oller |

| Carlos Antonio Soto Montañez |

| Juan Villaro Gumpert |

| Ana Beatriz Muñoz Díaz |

| Gustavo Useche Bonilla |

| Maria Noel Martina Lingua |

| Diana Pazmiño Zambrano |

| Sandra Castellano Gasch |

| Guadalupe Caparrós Tortosa |

| Silvia Soto Alarcón |

| Mercedes Albaladejo Pérez |

| Ignacio Cidraque Vella |

| Cristina Canal Girol |

| Silvia Benito García |

| Montserrat Picazo Sánchez |

| Anna Patrícia Balius Matas |

| Núria Garra Moncau |

| Rodrigo Avellaneda Campos |

| Ana María Ramos Verde |

| Laura Muñiz Pacios |

| Alfonso Pobes Martínez de Salinas |

| Maria Jimenez Herrero |

| Liliana Morán Caicedo |

| Mª Dolores Prados Garrido |

| Mariana Garbiras |

| Laura Sanchez Rodríguez |

| Maria Dolores Albero Molina |

| Elena Gutiérrez Solis |

| Ana Hernández Vicente |

| Angel.M Sevillano Prieto |

| Teresa Bada Bosch |

| Hernando Trujillo Cuéllar |

| Helena Díaz Cambre |

| Cassandra Emma Puig Hooper |

| Adriana Maria Cavada Bustamante |

| Boris Gonzales Gandía |

| Miguel Rodeles del Pozo |

| Miquel Blasco Pelicano |

| José Jesús Broseta Monzó |

| Jaime Sanz García |

| Jose Antonio Herrero Calvo |

| Isabel Maria Pérez Flores |

| Virginia López de la Manzanara Pérez |

| Javier Vian Pérez |

| Sara Huertas Salazar |

| Armando Coca Rojo |

| R. Alvarez |

| Miguel Angel González Rico |

| Ana Isabel Martinez Diaz |

| Elena Giménez Civera |

| Ignacio Lopez Alejaldre |

| Claudio José Hornos Hornos |

| Zakariae Koraichi Rabie Senhaji |

| Enriqueta González Rodríguez |

| Andrea Patricia Zapata Balcázar |

| Cecilia Montoyo Castillo |

| David Tura Rosales |

| Raúl Edilberto Alvarado Gutiérrez |

| Rafael Garcia Maset |

| Rosa Garcia Osuna |

| Maria Eugenia Palacios Gómez |

| Sergio García Marcos |

| Francisco Roca Oporto |

| Manuel Ramirez de Arellano Serna |

| Elena Olivar Pérez |

| Oihana Larrañaga Zabaleta |

| Mº Dolores Arenas Jiménez |

| Marta Crespo Barrio |

| Silvia Collado Nieto |

| María Dolores Redondo Pachón |

| Anna Buxeda i Porras |

| Laura Llinàs Mallol |

| Alberto Mendoza-Valderrey |

| Carola Arcal Cunillera |

| Basilio Martin Urcuyo |

| Adelaida Morales Umpiérrez |

| Aránzazu Márquez Corbella |

| Eva Gavela Martínez |

| Julia Kanter |

| Sandra Beltrán Catalán |

| Mercedes Gonzalez Moya |

| July Vanessa Osma Capera |

| Alejandro Valero Anton |

| Elena Castillón Lavilla |

| Juan Casas Todolí |

| Amir Shabaka Fernández |

| Ainhoa Hernando Rubio |

| Inmaculada Lorenzo Gonzalez |

| Francisco Llamas fuentes |

| Francisco Javier Centellas Pérez |

| Ana Pérez Rodríguez |

| Alejandra Rodriguez |

| Jorge Reichert |

| Rosa Sanchez Hernández |

| Luis Fernando Domínguez Reina |

| Antonio Franco Esteve |

| Eduardo Muñoz de Bustillo Llorente |

| Dioné González Ferri |

| Alejandro Pérez Alba |

| Luis Guillermo Piccone Saponara |

| María Esperanza Moral Berrio |

| Silvia Ros Ruiz |

| Leonidas Cruzado Vega |

| Eduardo Bosque Muñoz |

| Joaquín de Juan Ribera |

| Josefa Martin Rivas |

| Inés Aragoncillo Sauco |

| Luis Alberto Sánchez Cámara |

| Antonio Pérez Pérez |

| Mª José Navarro Parreño |

| Gracia Mª Alvarez Fernández |

| Marisol Ros Romero |

| Diana Manzano Sánchez |

| Maria Molina Gomez |

| Javier Juega |

| Andrés Villegas Fuentes |

| Laura Espinosa Román |

| Cristóbal Donapetry García |

| Pablo Castro de la Nuez |

| Antonio Crespo Navarro |

| Neus Rodriguez Farre |

| Jesus Martin Garcia |

| Antonio Gascón Mariño |

| Secundino Cigarran Guldris |

| Margarita Montserrat Pousa Ortega |

| Roberto Holgado Salado |

| Margarita Delgado Cordova |

| Natalia Blanco Castro |

| Elvira Esquivias de Motta |

| Veronica Lopez Jimenez |

| Belen Gómez Giralda |

| María Verónica Torres Jaramillo |

| Juan Cristobal Santacruz Mancheno |

| Beatriz María Durá Gúrpide |

| Paula Munguía Navarro |

| Belen Moragrega |

| Marta Luzon Alonso |

| Fernando Gil Catalinas |

| Emma Huarte Loza |

| Cecilia Dall'Anese Siegenthaler |

| Pedro Jesús Labrador Gómez |

| Silvia González Sanchidrián |

| Yanina García Marcote |

| Bruna Natacha Leite Costa |

| Joan Manuel Gascó Company |

| Juan Rey Valeriano |

| Sheila Cabello Pelegrin |

| Paloma Livianos Arias-Camisón. |

| Maria Teresa García Falcón |

| Ana Rodriguez-Carmona |

| Antía López Iglesias |

| Felipe Sarró Sobrín |

| Maria Luisa Martin Conde |

| Javier Arrieta Lezama |

| Iñigo Moina Eguren |

| Olga Gonzalez Peña |

| Maria del Carmen Díaz Corte |

| Maria Luisa Suarez Fernandez |

| Pedro Vidau Arguelles |

| Elena Astudillo Cortés |

| Lucía Sobrino Díaz |

| Alba Rivas Oural |

| Luis Fernando Morán Fernández |

| Oscar Rolando Durón Vargas |

| Clara Sanz García |

| Adriana Maria Cavada Bustamante |

| Carmen Robledo Zulet |

| Oscar García Uriarte |

| Maria Begoña Aurrekoetxea Fernandez |

| Maria Isabel Jimeno Martín |

| Guillermo Alcalde Bezhold |

| Rosa Maria Ruiz-Calero Cendrero |

| Roman Hernandez Gallego |

| Maria Victoria Martin Hidalgo-Barquero |

| Pedro Abáigar Luquin |

| Emilio Sanchez |

| Sagrario García Rebollo |

| María Lourdes Pérez Tamajón |

| Alejandra Maxorata Alvarez Gonzalez |

| Greissi Jeniree Garcia Bonilla |

| Eva Alvarez |

| Sofía Zarraga Larrondo |

| Alfonso Cubas Alcaraz |

| Mª Teresa Naya Nieto |

| Fernando Henriquez Palop |

| Raquel Santana Estupiñán |

| Ernesto Francisco Valga Amado |

| Gabriel De Arriba De La Fuente |

| Marta Sánchez Heras |

| Concepción Alamo Caballero |

| Maria Pilar Perez del Barrio |

| Clara María Moriana Domínguez |

| Sara Blázquez Roselló |

| Gema Velasco Barrero |

| Jary Perello Martinez |

| Manuel Ramos Díaz |

| Marina Almenara Tejederas |

| Martín Giorgi González |

| Beatriz Diez Ojea |

| Vicente Paraíso Cuevas |

| Fernando Tornero Molina |

| David rodríguez Santarelli |

| Jessica Isabel Urdaneta Colmenares |

| Luis Alberto Blázquez Collado |

| Maria Teresa Rodrigo De Tomas |

| Fernando Simal Blanco |

| Marta Albalate Ramón |

| Patricia de Sequera Ortiz |

| Rafael Lucena Valverde |

| Raquel Diaz Mancebo |

| Rocio Echarri Carrillo |

| Gabriel Ledesma Sanchez |

| Ernesto Jose Fernandez Tagarro |

| Iván Chamorro Bucheli |

| Joan Albert Fernández Roig |

| Isabel Garcia Mendez |

| Carlos Jimenez Martin |

| María Ovidia López Oliva |

| Mª Elena González García |

| Maria Auxiliadora Bajo Rubio |

| Laura Alvarez García |

| Jesus Calviño Varela |

| Juan Carlos Ruiz San Millán |

| Celestino Piñera Haces |

| Rosa Palomar Fontanet |

| Rosalía Valero San Cecilio |

| M. Jose Aladrén Regidor |

| Alejandro Soria Villén |

| Cristina Medrano Villarroya |

| Orlando Siverio Morales |

| Diego Rodríguez Puyol |

| María Pérez Fernández |

| Jose Portoles Perez |

| Charo Llopez Carratala |

| Auxiliadora Mazuecos |

| Juan Manuel Cazorla Lopez |

| Maríaa Gabriela Sánchez Márquez |

| Carolina Lancho Novillo |

| Lien Winderickx |

| Carlos Íñiguez Villalón |

| Cristina Galeano Álvarez |

| Sara Jiménez Álvaro |

| Esmeralda Castillo Rodríguez |

| Daniel Eduardo Villa Hurtado |

| Milagros Fernandez Lucas |

| Alberto Rodríguez Benot |

| Sagrario Soriano Cabrera |

| Raquel Ojeda López |

| Jose Luis Pérez Canga |

| Ana Cristina Andrade López |

| Anna Gallardo Pérez |

| Aniana Oliet Palá |

| Maria Sanchez Sanchez |

| Juan Manuel Buades Fuster |

| Maria Eugenia Palacios Gómez |

| Felisa Martínez Sanchez |

| Cristina Jimeno Griñó |

| Adoración Martínez Losa |

| Isabel María Saura Luján |

| Luis Gil Sacaluga |

| Gabriel Bernal Blanco |

| Maria Jose Marco Guerrero |

| Ana Isabel Martínez Puerto |

| Mª Jesús Moyano Franco |

| Elena Araceli Jiménez Víbora |

| Nuria Aresté Fosalba |

| Maria de los Ángeles Rodríguez Pérez |

| Ramos Escorihuela |

| Ramón Jesús Devesa Such |

| Isabel Beneyto Castelló |

| Edoardo Melilli |

| María José Soler Romeo |

| Francesc Moreso Mateos |

| Nestor Gabriel Toapanta Gaibor |

| Alfonso Pobes Martínez de Salinas |

| Begoña Rincón Ruiz |

| Mªcarmen Ruiz Fuentes |

| Ramón López-Menchero Martínez |

| Miguel Angel Suarez Santistebam |

| Carlos Jarava Mantecón |

| Fernando Fernandez Giron |

| Omar Miranda Espinal |

| Juan Carlos Martínez Ocaña |

| Raúl García Castro |

| Florentino Villanego Fernández |

| Montserrat Belart Rodríguez |

| Camino García Monteavaro |

Contributor Information

Borja Quiroga, IIS-La Princesa, Nephrology Department, Hospital de la Princesa, Madrid, Spain.

Alberto Ortiz, IIS-Fundación Jimenez Diaz, School of Medicine, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Fundación Renal Iñigo Alvarez de Toledo-IRSIN, REDinREN, Instituto de Investigación Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

Carlos Jesús Cabezas-Reina, Nephrology Department, Hospital Universitario de Toledo, Toledo, Spain.

María Carmen Ruiz Fuentes, Nephrology Department, Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, Spain.

Verónica López Jiménez, Nephrology Department, Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga, Universidad de Málaga, Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Málaga, RICORS2040 (RD21/0005/0012), Malaga, Spain.

Sofía Zárraga Larrondo, Nephrology Department, Hospital Universitario de Cruces, Bizkaia, Spain.

Néstor Toapanta, Nephrology Department, Vall d'Hebrón University Hospital, 08035 Barcelona, Spain.

María Molina Gómez, Nephrology Department, University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol (HUGTiP) & REMAR-IGTP Group, Germans Trias i Pujol Research Institude (IGTP), Can Ruti Campus, Badalona Barcelona, Spain.

Patricia de Sequera, Nephrology Department, Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor – Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

Emilio Sánchez-Álvarez, Nephrology Department, Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes, Gijón, Spain.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available upon a reasonable request.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

B.Q. has received honoraria for conferences, consulting fees and advisory boards from Vifor-Pharma, Astellas, Amgen, Bial, Ferrer, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Sandoz, Laboratorios Bial, Esteve, Sanofi-Genzyme and Otsuka. He is the present secretary of the Spanish Society of Nephrology. A.O. has received grants from Sanofi and consultancy or speaker fees or travel support from Advicciene, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Amicus, Amgen, Fresenius Medical Care, GSK, Bayer, Sanofi-Genzyme, Menarini, Kyowa Kirin, Alexion, Idorsia, Chiesi, Otsuka, Novo-Nordisk and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma, and is Director of the Catedra Mundipharma-UAM of diabetic kidney disease and the Catedra AstraZeneca-UAM of chronic kidney disease and electrolytes. He is the former Editor-in-Chief of CKJ. M.M.G. has received honoraria for conferences, consulting fees and advisory boards from Astellas and Chiesi. P.deS. reports honorarium for conferences, consulting fees and advisory boards from Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Braun, Fresenius, Nipro, Vifor-Pharma. She is the present president of the Spanish Society of Nephrology (S.E.N.). E.S.-Á. has received honoraria for conferences, consulting fees and advisory boards from AstraZeneca, Vifor, Astellas, Novo Nordisk and Baxter.

C.J.C.-R., M.C.R.F., V.L.J., N.T. and S.Z.L. do not present any disclosure.

REFERENCES

- 1. ERA-EDTA Council; ERACODA Working Group . Chronic kidney disease is a key risk factor for severe COVID-19: a call to action by the ERA-EDTA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021; 36: 87–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature 2020; 584: 430–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hilbrands LB, Duivenvoorden R, Vart P et al. COVID-19-related mortality in kidney transplant and dialysis patients: results of the ERACODA collaboration. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 1973–1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soler MJ, Jacobs-Cachá C. The COVID-19 pandemic: progress in nephrology. Nat Rev Nephrol 2021; 17: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanchez E, Macía M, de Sequera Ortiz P. Management of hemodialysis patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection: perspective from the Spanish Nephrology. Kidney360 2020; 1: 1254–1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. Alsaad R, Chen X, McAdams-DeMarco M. The clinical application of frailty in nephrology and transplantation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2021; 30: 593–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fernandez-Prado R, Gonzalez-Parra E, Ortiz A. Often forgotten, transport modality to dialysis may be life-saving. Clin Kidney J 2020; 13: 510–512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jonny VL, Kartasasmita AS, Amirullah Roesli RM et al. Pharmacological treatment options for Coronavirus Disease-19 in renal patients. Int J Nephrol 2021; doi: 10.1155/2021/4078713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Quiroga B, Soler MJ, Ortiz A et al. Safety and immediate humoral response of COVID-19 vaccines in chronic kidney disease patients: the SENCOVAC study [published online ahead of print, 2021 Nov 12]. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021; 2021: 14078713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. https://cnecovid.isciii.es/covid19/#documentaci%C3%B3n-y-datos March 2022.

- 11. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/en/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/situacionActual.htm March 2022.

- 12. Quiroga B, Sánchez-Álvarez E, Ortiz A et al. Suboptimal personal protective equipment and SARS-CoV-2 infection in Nephrologists: a Spanish national survey. Clin Kidney J 2021; 14: 1216–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rincón A, Moreso F, López-Herradón A et al. The keys to control a COVID-19 outbreak in a haemodialysis unit. Clin Kidney J 2020; 13: 542–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carriazo S, Kanbay M, Ortiz A. Kidney disease and electrolytes in COVID-19: more than meets the eye. Clin Kidney J 2020; 13: 274–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. https://www.senefro.org/contents/webstructure/MEMORIA_REER_2020_PRELIMINAR.pdf March 2022.

- 16. Kusztal M, Myślak M. Therapeutic dilemmas in dialysis patients hospitalized for COVID-19: balancing between nihilism, off-label treatment and side effects. Clin Kidney J 2021; 14: 1039–1041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. RECOVERY Collaborative Group, Horby P, Lim WS, Emberson JR et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 693–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yeung ML, Teng JLL, Jia L et al. Soluble ACE2-mediated cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 via interaction with proteins related to the renin-angiotensin system. Cell 2021; 184: 2212–2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Sequera Ortiz P, Quiroga B, de Arriba de la Fuente G et al. Protocol against coronavirus diseases in patients on renal replacement therapy: Dialysis and kidney transplant. Protocolo de actuación ante la epidemia de enfermedad por coronavirus en los pacientes de diálisis y trasplantados renales. Nefrologia (Engl Ed) 2020; 40: 253–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pizarro-Sánchez MS, Avello A, Mas-Fontao S et al. Clinical features of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Blood Press Res 2021; 46: 126–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon a reasonable request.