Abstract

The tcbR-tcbCDEF gene cluster, coding for the chlorocatechol ortho-cleavage pathway in Pseudomonas sp. strain P51, has been cloned into a Tn5-based minitransposon. The minitransposon carrying the tcb gene cluster and a kanamycin resistance gene was transferred to Pseudomonas putida KT2442, and chromosomal integration was monitored by selection either for growth on 3-chlorobenzoate or for kanamycin resistance. Transconjugants able to utilize 3-chlorobenzoate as a sole carbon source were obtained, although at a >100-fold lower frequency than kanamycin-resistant transconjugants. The vast majority of kanamycin-resistant transconjugants were not capable of growth on 3-chlorobenzoate. Southern blot analysis revealed that many transconjugants selected directly on 3-chlorobenzoate contained multiple chromosomal copies of the tcb gene cluster, whereas those selected for kanamycin resistance possessed a single copy. Subsequent selection of kanamycin resistance-selected single-copy transconjugants for growth on 3-chlorobenzoate yielded colonies capable of utilizing this carbon source, but no amplification of the tcb gene cluster was apparent. Introduction of two copies of the tcb gene cluster without prior 3-chlorobenzoate selection resulted in transconjugants able to grow on this carbon source. Expression of the tcb chlorocatechol catabolic operon in P. putida thus represents a useful model system for analysis of the relationship among gene dosage, enzyme expression level, and growth on chloroaromatic substrates.

The last 25 years have seen a vigorous investigation of genetic, biochemical, and ecological aspects of the interaction of many chloroaromatic compounds with microorganisms in the biosphere as part of a broad effort to understand the fate of these chemicals in the environment and to develop novel bioremediation strategies (22, 33, 37). One of the concepts to emerge from this body of work is the division of biodegradative routes into “upper” and “lower” pathways that are connected by the “central intermediate” chlorocatechol (38). Genetic studies of chlorocatechol ortho-cleavage pathways have shown that the regulatory and structural genes are grouped into divergent operons (11) and are often found on plasmids (13, 41). Combination of a chlorocatechol degradation pathway with an upper pathway having sufficiently broad substrate specificity to accept chloroaromatics has likely been an important factor in the evolution of chloroaromatic-mineralizing bacteria in response to xenobiotics in the environment. This notion is exemplified by the related chlorobenzene degradation pathways in Pseudomonas sp. strain P51 and Burkholderia sp. strain PS12: a complete mineralization pathway appears to have evolved through transposon-mediated recruitment of toluene or benzene dioxygenase and dihydrodiol dehydrogenase genes next to a gene cluster coding for an ortho-cleavage chlorocatechol pathway (4, 43). This same principle can be of service in the laboratory construction of desired phenotypes (36).

The potential for broadening the growth substrate range of bacteria to include chlorinated aromatics by equipping them with a chlorocatechol degradation pathway has long been recognized (see reference 30 for an extensive review). Previous attempts to develop novel biodegradative phenotypes have taken advantage of the transmission of plasmids between two strains, one capable of transforming an aromatic compound to chlorocatechol and the other capable of mineralizing chlorocatechol. Pure cultures capable of mineralizing chlorobenzene, 3-chlorobiphenyl, or 2-chlorobenzoate were isolated by mixing the appropriate individual strains and applying a selection regimen (1, 14, 18, 21). One major disadvantage of this plasmid-based approach is that the phenotype of the hybrid strain is expected to be unstable in the absence of selective pressure (15), a characteristic that is undesirable for field application, where constant selective pressure is not assured.

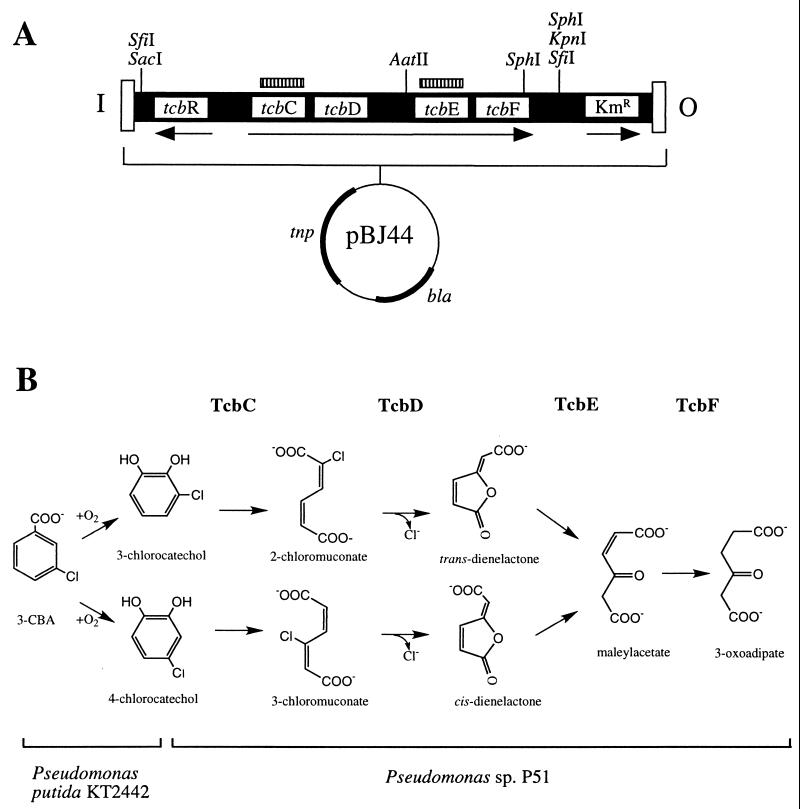

We describe here the creation of a “catabolic cassette” designed to facilitate the stable genetic modification of bacteria for chlorocatechol degradation. The cassette contains the complete chlorocatechol ortho-cleavage pathway (the tcbR-tcbCDEF gene cluster, hereafter referred to as the tcb gene cluster) from the trichlorobenzene-degrading strain Pseudomonas sp. strain P51 (41) in a Tn5-based minitransposon (16). The tcb chlorocatechol catabolic genes tcbCDEF are arranged in an operon and code for enzymes that convert chlorocatechol to 3-oxoadipate, a compound that eventually enters the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Fig. 1). The divergently transcribed gene tcbR encodes a LysR-type transcriptional activator (19, 40). Although the inducer for TcbR-mediated transcriptional activation has not been experimentally determined, the products of chlorocatechol ring fission (chlorinated muconates) are probable inducers by analogy with the closely related ClcR and CbnR transcriptional activators (20, 23). The tcb-encoded pathway was selected because (i) the complete sequence of the gene cluster was available when this work was initiated (39, 40), (ii) transfer of a plasmid containing the tcb gene cluster to Pseudomonas putida KT2442 confers on this strain the ability to grow on 3-chlorobenzoate (3-CBA) (41), and (iii) the chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase TcbC possesses the ability to cleave di- and tri- as well as monochlorinated catechols (39), potentially permitting the mineralization of multiply chlorinated aromatics.

FIG. 1.

(A) Diagram of pBJ44 illustrating the inner (I) and outer (O) minitransposon ends, the tcb gene cluster (tcbR-tcbCDEF), the kanamycin resistance marker (Kmr), the transposase gene (tnp), the β-lactamase gene (bla), and the restriction sites used for cloning and Southern analysis. Hatched bars indicate sequences used for probing Southern blots. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription of each of the three transcriptional units. (B) Pathway for the mineralization of 3-CBA following introduction of the tcb gene cluster into P. putida KT2442. The tcb-encoded enzymes responsible for catalyzing steps in the pathway are shown above the respective reactions: TcbC, chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase; TcbD, chloromuconate cycloisomerase; TcbE, dienelactone hydrolase; TcbF, maleylacetate reductase. 3-Oxoadipate is channeled into the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Brackets at the bottom indicate the species origins of the two components of the pathway.

Functioning of the cassette was tested following integration into the chromosome of P. putida KT2442, a strain capable of growth on benzoate. P. putida KT2442 is able to convert 3-CBA to 3- and 4-chlorocatechols, presumably through broad-spectrum benzoate dioxygenase and dihydrodiol dehydrogenase enzymes in a fashion similar to that observed with Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 (31, 32). P. putida KT2442 does not productively metabolize chlorocatechols and therefore does not grow on 3-CBA. Following conjugation of the tcb minitransposon into P. putida KT2442, acquisition of the ability to utilize 3-CBA as a sole source of carbon and energy was monitored, and selected transconjugants were analyzed in detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Bacteria grown with 3-CBA (sodium salt), sodium benzoate, or glucose as a sole carbon source were cultured in minimal salts medium as described previously (7), except that the concentration of phosphate buffer was doubled. Solid media contained 1.5% purified agar. P. putida and Ralstonia eutropha cultures were incubated at 30°C. Concentrations of antibiotics used were as follows: kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; rifampin, 70 μg/ml; piperacillin, 75 μg/ml; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 30 μg/ml; streptomycin, 50 μg/ml; and gentamicin, 20 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, transconjugants, and plasmids used in this study

| Strain, transconjugant, or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli CC118(λpir) | Δ(ara-leu) araD ΔlacX74 galE galK phoA20 thi-1 rpsE rpoB argE(Am) recA1; lysogenized with λpir phage | 16 |

| Escherichia coli HB101 | recA hsdR hsdM strA pro leu thi | 5 |

| Pseudomonas putida KT2442 | hsdR Rifr | 12 |

| Pseudomonas putida G7 | Nah+ | 9 |

| Pseudomonas putida PRS4020 | catR::Gmr Ben− | 26 |

| Ralstonia eutropha JMP222 | Smr | 6 |

| Transconjugants | ||

| Km-selected | ||

| P. putida KT2442::44CK | 3-CBA− Kmr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44EK | 3-CBA− Kmr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44FK | 3-CBA− Kmr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44LK | 3-CBA− Kmr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44MK | 3-CBA− Kmr Rifr | This study |

| Early 3-CBA-selected | ||

| P. putida KT2442::44AE | 3-CBA+ Kmr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44BE | 3-CBA+ Kmr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44HE | 3-CBA+ Kmr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44BJE | 3-CBA+ Kmr Pipr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44IE | 3-CBA+ Kmr Pipr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44JE | 3-CBA+ Kmr Pipr Rifr | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44KE | 3-CBA+ Kmr Pipr Rifr | This study |

| Late 3-CBA-selected | ||

| P. putida KT2442::44ES1L | 3-CBA+ derivative of 44EK | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44ES4L | 3-CBA+ derivative of 44EK | This study |

| P. putida KT2442::44ES5L | 3-CBA+ derivative of 44EK | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pRK600 | RK2-Mob+ RK2-Tra+ Cmr | 17 |

| pUC18Sfi | Apr | 16 |

| pUTKm | Minitransposon delivery vector; Kmr Apr | 16 |

| pBSL202 | Minitransposon delivery vector; Gmr Apr | 2 |

| pTCB45 | 13.0-kb SstI fragment carrying tcbRCDEF in pUC18; Kmr | 41 |

| pBJ3 | 7.0-kb SacI-KpnI fragment from pTCB45 in pUC18Sfi; Apr | This study |

| pBJ44 | 7.0-kb SfiI fragment from pBJ3 in pUTKm; Kmr Apr | This study |

| pDP100 | 7.0-kb SfiI fragment from pBJ3 in pBSL202; Gmr Apr | This study |

Resistance markers: Rif, rifampin; Gm, gentamicin; Sm, streptomycin; Km, kanamycin; Pip, piperacillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Ap, ampicillin.

Plasmid construction.

The minitransposon delivery vectors pBJ44 and pDP100 were constructed in two steps. First, a 7.0-kb SacI-KpnI fragment from pTCB45 containing the tcb gene cluster was ligated into SacI-KpnI-digested pUC18Sfi, yielding plasmid pBJ3. The resulting 7.0-kb SfiI fragment was then ligated into SfiI-digested pUTKm or pBSL202, generating minitransposon vectors pBJ44 (Fig. 1A) and pDP100, respectively. The orientation of the tcb gene cluster relative to the minitransposon inner end was checked by restriction enzyme digestion, and the orientation shown in Fig. 1A was used for all experiments.

Matings and isolation of transconjugants.

Plasmids were transferred to P. putida KT2442 or R. eutropha JMP222 in triparental filter matings. Fresh log-phase cultures of plasmid-containing donor strain Escherichia coli CC118(λpir), “helper” strain E. coli HB101/pRK600, and the recipient strain were mixed in a 1:1:1 ratio and spread onto a sterile 0.22-μm-pore-size nitrocellulose filter on a Luria-Bertani (LB) medium plate. After overnight incubation at 30°C, cell growth was resuspended in 1 ml of sterile 50 mM MgSO4, and plated on either (i) 3-CBA (2 or 10 mM) or (ii) 5 mM benzoate with the appropriate antibiotic(s). The frequency of phenotype acquisition per recipient cell was estimated by dividing the number of colonies appearing on selective media by the total number of potential recipients, as determined by plating of a dilution series on 5 mM benzoate. Growth on 3-CBA of transconjugants selected on benzoate plus antibiotic was assessed by patching onto 2 mM 3-CBA plates; a 3-CBA-positive (3-CBA+) phenotype was scored when significant cell density appeared in the patched area within 5 days of incubation at 30°C. Piperacillin resistance was assayed by patching transconjugants onto plates containing 5 mM benzoate and 75 μg of piperacillin per ml and incubating overnight at 30°C.

Transconjugants were isolated as follows. P. putida KT2442 transconjugants that were acquired from mating mixtures plated on benzoate-kanamycin plates were designated Km selected. Transconjugants that arose within 10 days from mating mixtures plated directly on 3-CBA were designated early 3-CBA selected. Each Km-selected and early 3-CBA-selected transconjugant listed in Table 1 was obtained from an independent mating. 3-CBA+ variants of P. putida KT2442::44EK (designated late 3-CBA selected) were selected by spreading 100 μl of a stationary-phase LB-kanamycin culture onto a 10 mM 3-CBA plate. All 3-CBA+ transconjugants analyzed in detail (Table 1) were streaked from the selection plate onto 2 mM 3-CBA, and a single colony was inoculated into liquid medium containing 5 mM 3-CBA. Following growth to stationary phase, the culture was once again streaked onto 2 mM 3-CBA, and a single colony was chosen for further analysis.

Generation of DNA probes by PCR.

DNA probe sequences for Southern blotting were generated by PCR amplification of portions of the tcbC gene (primers: forward, 5′ GTGAAGCAGGTTGCGTCCGC; reverse, 5′ CGCCCTCGGTCTTTGTCGGC), the tcbE gene (primers: forward, 5′ CCCGGTGGTGATGGTTGCGC; reverse, 5′ GAGGCGTGAGTGGGTCGTGG), and the tnp gene (primers: forward, 5′ GCGCTGGGTGATCCTCGCCG; reverse, 5′ GCGCAGGCTCAAGCTCGC) of pBJ44. A probe hybridizing to the macromolecular synthesis (MMS) operon was obtained by PCR amplification of the last 175 bp of dnaG, the intergenic sequence, and the first 523 bp of rpoD from P. putida KT2442 genomic DNA (primers: forward, 5′ CCAACGCGAGCGCAGCCTGG; reverse, 5′ CTCGTCGTCACCGCTTTCGG). PCRs were carried out with 50-μl reaction volumes containing 1.3 U of Taq polymerase (Qiagen) at an annealing temperature of 60°C (tcbC and tcbE) or 55°C (tnp and MMS) for an extension time at 72°C of 1 min. The PCR product was excised from the agarose gel and purified using a Qiaex II gel extraction kit (Qiagen).

Southern blots.

Total genomic DNA from P. putida KT2442 and the transconjugants was isolated using a QIAamp tissue kit (Qiagen). Approximately 5 μg of DNA was completely digested with SfiI, SphI, or AatII and electrophoresed on a 0.6% agarose gel. DNA was transferred to a Qiabrane Nylon Plus membrane (Qiagen) by vacuum blotting at 50 mbar (5 kPa) with the following steps: depurination (0.25 M HCl, 30 min), denaturation (0.5 M NaOH–1.5 M NaCl, 30 min), neutralization (1 M Tris–2 M NaCl, pH 5, 30 min), and transfer (20× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 2 h). Blotted DNA was cross-linked to the membrane with UV light. DNA probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 μCi/mmol; Amersham) using a RediPrime II random prime labeling kit (Amersham) and hybridized overnight at 68°C to the membrane-bound DNA in hybridization buffer (6× SSC, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% polyvinylpyrrolidone 40000, 0.1% glycerol, 100 μg of salmon sperm DNA per liter). The membrane was washed once in room-temperature 2× SSC–0.1% SDS, once in the same solution preheated to 68°C, and twice in 1× SSC–0.1% SDS preheated to 68°C. Signals were recorded on a phosphor screen, developed on a Storm 860 instrument, and analyzed using ImageQuaNT software (Molecular Dynamics).

To quantitate the number of copies of the tcb gene cluster in the genome of Km-selected transconjugants, the MMS operon sequence of P. putida KT2442 (35) was selected as an internal standard. The probe hybridized to a 1,624-bp SphI fragment of the MMS operon. For quantitative analysis of Southern blots, probes for tcbC and the MMS operon were labeled separately, purified from unincorporated [α-32P]dCTP, denatured, mixed, and added to the hybridization solution. Hybridization, washing, and autoradiography were carried out as described above. Signal intensities were determined using the Auto Area Report function of ImageQuaNT software and were within the linear range of the phosphor screen. Baseline correction was performed manually.

Preparation of cell extracts and enzyme assays.

Starter cultures of P. putida transconjugants were grown in mineral salts medium containing either 5 mM 3-CBA or 5 mM glucose–50 μg of kanamycin per ml and then diluted 1:100 (3-CBA) or 1:200 (glucose-kanamycin) into fresh medium containing 10 mM respective growth substrate. Cultures were shaken in baffled flasks at 135 rpm and 30°C. Cells were harvested during exponential growth, washed once in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until needed. Immediately prior to enzyme assays, cells were thawed, washed once with ice-cold 50 mM Tris-HCl–4 mM MnSO4 (pH 7.0), resuspended in 1 ml of the same buffer, and lysed by two passages through a chilled French pressure cell at 800 lb/in2. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 128,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C; the supernatant was removed and used directly in enzyme assays.

TcbC activity was measured spectrophotometrically at 25°C with a 1-ml volume containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 2.5 mM EDTA, and 0.2 mM 3-chlorocatechol. Assay mixtures were preincubated for 2 min in a thermostat-controlled cuvette holder, and then reactions were initiated by the addition of substrate. An extinction coefficient of 17,100 M−1 cm−1 for 2-chloromuconate at 260 nm was used to calculate activity (8). One unit of activity corresponds to 1 nmol of substrate converted per minute. Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford assay (Biorad) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Chemicals.

3-Chlorobenzoic acid (≥99% pure) was obtained from Fluka, and 3-chlorocatechol was obtained from Promochem.

RESULTS

Construction of pBJ44, conjugative transfer to P. putida KT2442, and phenotypic analysis.

A minitransposon vector containing the tcb gene cluster (pBJ44) was constructed as depicted in Fig. 1A. This vector was transferred by conjugation to P. putida KT2442, which is able to transform 3-CBA to 3- and 4-chlorocatechols (Fig. 1B) but cannot efficiently further metabolize chlorocatechols; therefore, the ability of transconjugants to grow on 3-CBA indicated acquisition and expression of the tcb-encoded enzymes. Transconjugants containing the minitransposon from pBJ44 were selected in two ways. The first mode of selection involved plating of the mating mixture directly onto 3-CBA. The second mode of selection took advantage of the kanamycin resistance gene downstream of the tcbCDEF operon in the minitransposon. Transconjugants obtained from kanamycin selection with unchlorinated benzoate as the sole carbon source are referred to as Km selected and are indicated with a subscript “K” (Table 1).

Conjugal transfer and stable acquisition of minitransposon DNA occurred with a frequency of approximately 10−6 per recipient based on expression of the kanamycin resistance marker. Three percent of Km-selected transconjugants (4 of 128 from six independent matings) were also resistant to the β-lactam piperacillin, in agreement with published values for chromosomal integration of the bla-containing vector DNA along with the minitransposon (16). Surprisingly, only 2% (1 of 50) of the Km-selected transconjugants were capable of growth when patched onto 3-CBA plates (3-CBA+). Selection for expression of the tcb genes by plating mating mixtures directly on 2 or 10 mM 3-CBA for 7 days gave rise to 102 to 103 fewer transconjugants than did kanamycin selection. These early 3-CBA+ transconjugants were designated early 3-CBA-selected and are indicated with a subscript “E.” Seventy-five percent of the early 3-CBA+ transconjugants (55 of 73 from seven independent matings) were resistant to piperacillin, indicating that the vector DNA had been stably incorporated into the chromosome in the majority of the transconjugants. After approximately 15 days of incubation, new colonies began to appear on the 3-CBA plates; after 5 weeks of incubation, the number of 3-CBA+ transconjugants was 5% that of kanamycin-resistant transconjugants. These late 3-CBA+ colonies (designated late 3-CBA selected and indicated with a subscript “L”) were characterized by a fraction of piperacillin resistance comparable to that of Km-selected transconjugants, thereby further distinguishing them from the early 3-CBA-selected colonies (data not shown).

Representatives of the three classes of transconjugants (Km selected, early 3-CBA selected, and late 3-CBA selected) were isolated for further analysis of tcb gene expression (Table 1). Five 3-CBA-negative (3-CBA−) Km-selected and seven early 3-CBA-selected transconjugants were isolated directly from mating selection plates. The appearance of late 3-CBA-selected transconjugants was reproduced by plating the Km-selected transconjugant P. putida KT2442::44EK on 2 mM 3-CBA (hereafter transconjugants are referred to as, for example, “44EK” for P. putida KT2442::44EK). The advantage of this approach, as opposed to picking colonies directly from mating plates, was that the resulting 3-CBA+ colonies could be compared directly to the parent transconjugant. Colonies began to appear after 14 days and continued to appear for the duration of the experiment (9 weeks). Three 3-CBA+ colonies derived from 44EK were isolated and designated 44ES1L, 44ES4L, and 44ES5L.

The Km-selected transconjugants listed in Table 1 were analyzed further to determine whether the apparent lack of ability to grow on 3-CBA was an artifact of the culture conditions. Preculturing on plates containing rich medium (LB) or minimal salts medium with either glucose, benzoate, or benzoate–3-CBA in an 8:1 molar ratio did not alter the inability to grow on 2 mM 3-CBA plates. Decreasing the 3-CBA concentration in the plates fourfold to 0.63 mM also had no effect (data not shown).

Conjugation of pBJ44 into a naphthalene-degrading strain (P. putida G7), a catR host (P. putida PRS4020), and a member of the β subdivision of the Proteobacteria (R. eutropha JMP222) yielded results similar to those observed with P. putida KT2442.

Plate assay for TcbC expression.

Growth of P. putida KT2442 on solid agar containing mixtures of benzoate and 3-CBA resulted in deep brown coloration of the medium due to the accumulation and autooxidation of chlorocatechol, whereas the growth of a 3-CBA+ transconjugant on the same mixtures was not accompanied by discoloration (data not shown). These observations suggested a qualitative plate assay for expression of the tcbC chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase gene in Km-selected transconjugants. With a 5 mM:0.63 mM (8:1) ratio of benzoate to 3-CBA, P. putida KT2442 produced sufficient chlorocatechol that both the microbial growth and the surrounding medium turned brown. In contrast, the growth of Km-selected transconjugants 44CK, 44EK, 44FK, 44LK, and 44MK as well as 3-CBA+ transconjugants 44KE and 44ES1L did not produce detectable brown coloration, suggesting that TcbC was expressed in all transconjugants under these conditions.

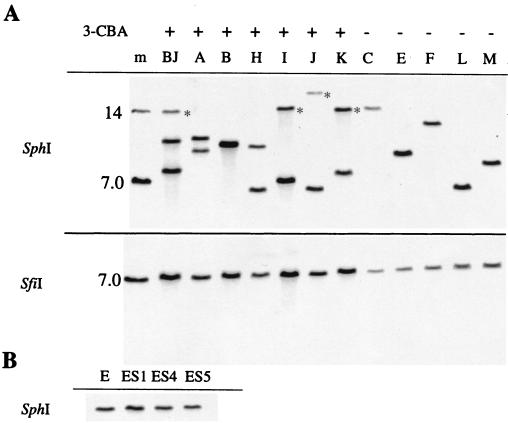

Southern blot analysis of chromosomal DNA.

Genomic DNA from 5 Km-selected and 10 3-CBA-selected transconjugants (7 early, 3 late) was isolated, digested with SfiI or SphI, and probed with a PCR-amplified fragment of tcbC (Fig. 2). SfiI restriction sites flank the tcb gene cluster and should give rise to a 7-kb fragment if the entire minitransposon is incorporated into the genome. A single band of 7 kb was observed in all SfiI digests (Fig. 2A). There are two SphI sites in pBJ44, one in tcbF and one between the tcbF gene and the kanamycin resistance gene (Fig. 1A). A single SphI fragment from each of the five Km-selected transconjugants hybridized to the tcbC probe. Quantitation of the signal intensity relative to that of the single-copy MMS operon yielded an average copy number for the tcb gene cluster of 0.95 ± 0.12 in the Km-selected transconjugants. Unexpectedly, genomic DNA from six of the seven early 3-CBA-selected transconjugants gave rise to multiple SphI fragments capable of hybridizing to the tcbC probe; five of these transconjugants (44AE, 44HE, 44IE, 44JE, and 44KE) contained two hybridizing fragments, whereas 44BJE contained three (Fig. 2A). The late 3-CBA-selected transconjugants (44ES1L, 44ES4L, and 44ES5L) each contained a single hybridizing fragment, the size of which was identical to that in the parent transconjugant 44E (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Southern blots of selected P. putida transconjugants probed with DNA complementary to tcbC. (A) SphI and SfiI digests of genomic DNA from early 3-CBA-selected and Km-selected transconjugants. Transconjugants are identified by letter; m, size markers. The 3-CBA phenotype is indicated above each lane. Asterisks indicate bands that hybridized to a tnp probe. (B) SphI digests of genomic DNA from a 3-CBA− transconjugant (44EK) and three 3-CBA+ derivatives (44ES1L, 44ES4L, and 44ES5L). This figure was prepared using Adobe Photoshop 5.0 and Canvas 6 (Deneba Systems, Inc.).

Four of the 3-CBA-selected transconjugants (44BJE, 44IE, 44JE, and 44KE) were resistant to piperacillin, suggesting that pBJ44 had recombined with the chromosome to form a cointegrate. To identify pBJ44 vector DNA outside of the tcb minitransposon, the Southern blot of SphI-digested genomic DNA shown in Fig. 2A was stripped and reprobed with the transposase (tnp) gene. Only those transconjugants identified as being piperacillin resistant contained DNA that hybridized with the tnp probe, and the hybridizing band had the same mobility as one of the tcbC-hybridizing bands in each case (Fig. 2A).

One possible route to multiple chromosomal copies of the tcb gene cluster consists of the transposition of one copy followed by homologous recombination with a second copy of pBJ44, generating tandem repeats of the tcb gene cluster separated by pBJ44 DNA. In such a case, digestion of the genomic DNA with a restriction enzyme would yield a tcbC-hybridizing fragment equal in size to that from pBJ44 digested with the same enzyme. As three of the 3-CBA-selected transconjugants (44BJE, 44IE, and 44KE) contained tcbC- and tnp-hybridizing SphI fragments that appeared to comigrate with a 14-kb SphI fragment from pBJ44, the possibility that these transconjugants contained tandem repeats was investigated further. Genomic DNA from the three transconjugants was digested with AatII, a restriction enzyme that cuts once in pBJ44 between tcbC and tcbE, and a Southern blot was probed with DNA complementary to tcbC or tcbE. A fragment comigrating with AatII-digested pBJ44 was observed to hybridize with both the tcbC and the tcbE probes for 44BJE and 44KE (data not shown); this outcome is possible only if two tandem copies of the tcb gene cluster are present. To ensure that pBJ44 was not present as an autonomously replicating plasmid in these transconjugants, total undigested DNA was probed following Southern blotting. No hybridization was observed at a mobility corresponding to that of supercoiled or linear pBJ44.

TcbC specific activity in 3-CBA+ transconjugants.

The specific activities of the chlorocatechol 1,2-dioxygenase TcbC in crude extracts of 3-CBA+ transconjugants grown on either 3-CBA or glucose as a sole carbon source were measured (Table 2). TcbC specific activities in extracts of cells grown on 3-CBA with 3-chlorocatechol as a substrate varied over a threefold range. Specific activities in extracts of glucose-grown cells were a small fraction of those of 3-CBA-grown cells, indicating that the expression of TcbC is induced in the presence of a chloroaromatic substrate.

TABLE 2.

TcbC specific activities in crude extracts of transconjugants grown on 3-CBA or glucose

| Transconjugant | TcbC sp act, U/mg of protein, ona:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 3-CBA | Glucose | |

| 44ES1L | 388 ± 6 | 8 |

| 44HE | 376 ± 8 | 4 ± 1 (1) |

| 44BE | 551 ± 75 | 13 ± 3 (2) |

| 44KE | 622 ± 97 | 16 ± 4 (3) |

| 44IE | 1,170 ± 100 | 32 ± 8 (3) |

Each measurement represents the mean ± standard deviation for three cultures; when no standard deviation is given, only a single culture was assayed. Values in parentheses indicate the relative TcbC specific activity, expressed as a percentage, in cell extracts from glucose-grown cells compared with 3-CBA-grown cells.

Construction of transconjugants with two copies of the tcb gene cluster.

To introduce a second copy of the tcb gene cluster into Km-selected transconjugants, the gene cluster was subcloned into a minitransposon vector containing a gentamicin resistance gene (pBSL202). The resulting plasmid, pDP100, was transferred to transconjugants 44CK and 44EK, and kanamycin- and gentamicin-resistant clones were isolated. All transconjugants tested grew on 10 mM 3-CBA plates (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The tcb gene cluster of Pseudomonas sp. strain P51 was introduced into the chromosome of P. putida KT2442, and the resulting transconjugants were evaluated for the ability to grow on 3-CBA. Following direct plating on 3-CBA, two distinct classes of 3-CBA+ colonies arose, distinguished by their rate of appearance and frequency of piperacillin resistance. Early 3-CBA-selected transconjugants appeared rapidly and were characterized by a high incidence of piperacillin resistance, indicating frequent chromosomal integration of vector DNA. Late 3-CBA-selected transconjugants began to appear after 15 days of incubation, and the observed small fraction of piperacillin-resistant transconjugants was similar to that previously reported for the miniTn5 vector pUTKm (16). One clear genotypic difference between the two classes of 3-CBA-selected transconjugants lay in the number of copies of the tcb gene cluster, observed as discreet bands on a Southern blot: six of seven early 3-CBA-selected transconjugants analyzed contained multiple copies of the tcb gene cluster, while the three late 3-CBA-selected transconjugants appeared to possess a single copy. All five Km-selected transconjugants analyzed also had a single copy of the tcb gene cluster, indicating that the appearance of multiple copies in early 3-CBA-selected transconjugants was not an artifact of the minitransposon delivery vector. A sequence of gene amplification, mutation, and deamplification has recently been proposed to explain the adaptive mutability of the lac operon in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (3). When two copies of the tcb gene cluster were introduced into the P. putida genome using independent antibiotic resistance markers, no prior exposure to 3-CBA was required for growth on this carbon source. This observation rules out the possibility that the presence of multiple copies of the tcb gene cluster is an indirect consequence of the requirement for a mutation as a prerequisite for growth on 3-CBA.

There are several ways through which a 3-CBA+ transconjugant might acquire multiple copies of the tcb gene cluster. One possibility involves transposition of a single copy followed by recombination between short homologous flanking sequences in the genome, as was observed with the β-lactamase ampC gene in Escherichia coli (10). Another possibility is conjugative transfer of two copies of pBJ44, resulting in either two independent transposition events or transposition followed by homologous recombination. The latter possibility would result in tandem repeats of the minitransposon separated by vector DNA, an arrangement observed for transconjugants 44BJE and 44KE.

TcbC specific activities in crude extracts of 3-CBA+ transconjugants varied over a threefold range. Variability in expression levels is expected to arise from two sources: the number of copies of the tcb gene cluster and the position of these copies in the genome (34). All TcbC specific activities were at least twofold higher than the 170 U/mg of protein reported for 3-CBA-grown P. putida KT2442 containing the tcb gene cluster on a broad-host-range plasmid (41). Very low levels of TcbC activity were observed following growth of the 3-CBA+ transconjugants on glucose as a sole carbon source, indicating that the tcb structural genes were inducible, as previously reported (40). Growth of the transconjugants on a mixture of glucose and 3-CBA did not result in efficient induction of the Tcb enzymes; thus, it was not possible to make quantitative comparisons of TcbC expression levels of 3-CBA− and 3-CBA+ transconjugants. In a qualitative plate assay, all Km-selected transconjugants were found to express TcbC at levels sufficient to prevent the visible accumulation of chlorocatechol oxidation products in the presence of high concentrations of 3-CBA.

Interesting parallels can be drawn between the system studied here and other organisms capable of degrading chloroaromatics. The best-characterized example involves the clcR-clcABDE gene cluster of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13, which encodes functional homologs of tcbR-tcbCDEF products (37). In 1988, the amplification of a 4.3-kb BglII fragment containing the clc genes in Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 clones expressing a 3-CBA+ phenotype was reported (27). Recently, the molecular basis for this phenomenon was discovered: the clc genes were found to reside on a 105-kb genetic element capable of site-specific chromosomal integration (28, 29). Studies carried out following conjugation of the clc element to P. putida F1, which is capable of converting monochlorobenzene (MCB) to chlorocatechol, demonstrated two site-specific integration loci; however, transconjugants containing two copies of the clc element were unable to grown on MCB. Characterization of MCB-positive transconjugants revealed that three to eight copies of the clc element were required for growth on MCB as a sole carbon source, with a larger number of clc elements being associated with increasingly vigorous growth. Interestingly, prolonged exposure of P. putida F1 containing two clc elements to MCB resulted in colonies able to grow on this carbon source without amplification of the element (28); these colonies were analogous to late 3-CBA-selected P. putida KT2442::tcb gene cluster transconjugants. Thus, it is likely that adaptation to chlorocatechols can occur through mechanisms other than gene amplification. In another example, duplication of the cbnR-cbnABCD gene cluster from Alcaligenes eutrophus NH9, which shares very high sequence similarity with the tcbR-tcbCDEF gene cluster, was found to be associated with increased fitness following long-term growth on 3-CBA in liquid batch cultures (24, 25). Additionally, a duplication of clcRA from the clcRABD locus in chlorobenzene-degrading Ralstonia sp. strain JS705 was observed (42). The genetic evidence suggests that gene amplification has played an important role in the adaptation of bacteria to chlorocatechol degradation in environments contaminated with chloroaromatics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to I. Plumeier and S. Backhaus for excellent technical assistance, J. Armengaud and S. Beil for invaluable advice, T. Potrawfke and B. Hofer for PCR primers, J. R. van der Meer for pTCB45, C. S. Harwood for P. putida strain PRS4020, B. Gonzalez for helpful discussions, and K. N. Timmis for supporting this work.

This work was supported by contract BI04-CT97-2040 of the BIOTECH program of the EC. M.K. thanks the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation for financial support in the form of a research fellowship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams R H, Huang C-M, Higson F K, Brenner V, Focht D D. Construction of a 3-chlorobiphenyl-utilizing recombinant from an intergeneric mating. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:647–654. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.2.647-654.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexeyev M F, Shokolenko I N, Croughan T P. New mini-Tn5 derivatives for insertion mutagenesis and genetic engineering in Gram-negative bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1995;41:1053–1055. doi: 10.1139/m95-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson D I, Slechta E S, Roth J R. Evidence that gene amplification underlies adaptive mutability of the bacterial lac operon. Science. 1998;282:1133–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beil S, Timmis K N, Pieper D H. Genetic and biochemical analyses of the tec operon suggest a route for evolution of chlorobenzene degradation genes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:341–346. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.341-346.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer H W, Roulland-Dussoix D. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1969;41:459–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Don R H, Pemberton J M. Properties of six pesticide degradation plasmids isolated from Alcaligenes paradoxus and Alcaligenes eutrophus. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:681–686. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.2.681-686.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorn E, Hellwig M, Reineke W, Knackmuss H-J. Isolation and characterization of a 3-chlorobenzoate degrading pseudomonad. Arch Microbiol. 1974;99:61–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00696222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorn E, Knackmuss H-J. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Substituent effects on 1,2-dioxygenation of catechol. Biochem J. 1978;174:85–94. doi: 10.1042/bj1740085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn N W, Gunsalus I C. Transmissible plasmid coding early enzymes of naphthalene oxidation in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1973;114:974–979. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.3.974-979.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edlund T, Normark S. Recombination between short DNA homologies causes tandem duplication. Nature. 1981;292:269–271. doi: 10.1038/292269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eulberg D, Kourbatova E M, Golovleva L A, Schlömann M. Evolutionary relationship between chlorocatecol catabolic enzymes from Rhodococcus opacus 1CP and their counterparts in proteobacteria: sequence divergence and functional convergence. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1082–1094. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1082-1094.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franklin F C, Bagdasarian M, Bagdasarian M M, Timmis K N. Molecular and functional analysis of the TOL plasmid pWWO from Pseudomonas putida and cloning of genes for the entire regulated aromatic ring meta cleavage pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7458–7462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosal D, You I-S, Chatterjee D K, Chakrabarty A M. Genes specifying degradation of 3-chlorobenzoic acid in plasmids pAC27 and pJP4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1638–1642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartmann J, Karin E, Nordhaus B, Schmidt E, Reineke W. Degradation of 2-chlorobenzoate by in vivo constructed hybrid pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;61:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hempel C, Erb R W, Deckwer W-D, Hecht V. Plasmid stability of recombinant Pseudomonas sp. B13 pFRC20P in continuous culture. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;57:62–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrero M, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertions of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler B, de Lorenzo V, Timmis K N. A general system to integrate lacZ fusions into the chromosomes of gram-negative eubacteria: regulation of the Pm promoter of the TOL plasmid studied with all controlling elements in monocopy. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;233:293–301. doi: 10.1007/BF00587591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kröckel L, Focht D D. Construction of chlorobenzene-utilizing recombinants by progenitive manifestation of a rare event. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2470–2475. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.10.2470-2475.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leveau J H J, de Vos W M, van der Meer J R. Analysis of the binding site of the LysR-type transcriptional activator TcbR on the tcbR and tcbC divergent promoter sequences. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1850–1856. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.7.1850-1856.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFall S M, Parsek M R, Chakrabarty A M. 2-Chloromuconate and ClcR-mediated activation of the clcABD operon: in vitro transcriptional and DNase I footprint analyses. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3655–3663. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3655-3663.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mokross H, Schmidt E, Reineke W. Degradation of 3-chlorobiphenyl by in vivo constructed hybrid pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:179–186. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90053-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neilson A H. An environmental perspective on the biodegradation of organochlorine xenobiotics. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 1996;37:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogawa N, McFall S M, Klem T J, Miyashita K, Chakrabarty A M. Transcriptional activation of the chlorocatechol degradative genes of Ralstonia eutropha NH9. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6697–6705. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.21.6697-6705.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogawa N, Miyashita K. The chlorocatechol catabolic transposon Tn5707 of Alcaligenes eutrophus NH9, carrying a gene cluster highly homologous to that in the 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene-degrading bacterium Pseudomonas sp. strain P51, confers the ability to grow on 3-chlorobenzoate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:724–731. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.724-731.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa N, Miyashita K. Recombination of a 3-chlorobenzoate catabolic plasmid from Alcaligenes eutrophus NH9 mediated by direct repeat elements. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3788–3795. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3788-3795.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parales R E, Harwood C S. Regulation of the pcalJ genes for aromatic acid degradation in Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5829–5838. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.18.5829-5838.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rangnekar V M. Variation in the ability of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13 cultures to utilize meta-chlorobenzoate is associated with tandem amplification and deamplification of DNA. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1907–1912. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.4.1907-1912.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravatn R, Studer S, Springael D, Zehnder A J B, van der Meer J R. Chromosomal integration, tandem amplification, and deamplification in Pseudomonas putida F1 of a 105-kilobase genetic element containing the chlorocatechol degradative genes from Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4360–4369. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4360-4369.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravatn R, Studer S, Zehnder A J B, van der Meer J R. Int-B13, an unusual site-specific recombinase of the bacteriophage P4 integrase family, is responsible for chromosomal insertion of the 105-kilobase clc element of Pseudomonas sp. strain B13. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5505–5514. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5505-5514.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reineke W. Development of hybrid strains for the mineralization of chloroaromatics by patchwork assembly. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:287–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reineke W, Knackmuss H-J. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Substituent effects on 1,2-dioxygenation of benzoic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;542:412–423. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reineke W, Knackmuss H-J. Chemical structure and biodegradability of halogenated aromatic compounds. Substituent effects on dehydrogenation of 3,5-cyclohexadiene-1,2-diol-1-carboxylic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;542:424–429. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(78)90373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reineke W, Knackmuss H-J. Microbial degradation of haloaromatics. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1988;42:263–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sousa C, de Lorenzo V, Cebolla A. Modulation of gene expression through chromosomal positioning in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1997;143:2071–2078. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-6-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szafranski P, Smith C L, Cantor C R. Principal transcription sigma factors of Pseudomonas putida strains mt-2 and G1 are significantly different. Gene. 1997;204:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00533-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Timmis K N, Pieper D H. Bacteria designed for bioremediation. Trends Biotechnol. 1999;17:201–204. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(98)01295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van der Meer J R. Evolution of novel metabolic pathways for the degradation of chloroaromatic compounds. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1997;71:159–178. doi: 10.1023/a:1000166400935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Meer J R. Genetic adaptation of bacteria to chlorinated aromatic compounds. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;15:239–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Meer J R, Eggen R I L, Zehnder A J B, de Vos W M. Sequence analysis of the Pseudomonas sp. strain P51 tcb gene cluster, which encodes metabolism of chlorinated catechols: evidence for specialization of catechol 1,2-dioxygenases for chlorinated substrates. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2425–2434. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.8.2425-2434.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Meer J R, Frijters A C J, Leveau J H J, Eggen R I L, Zehnder A J B, de Vos W M. Characterization of the Pseudomonas sp. strain P51 gene tcbR, a LysR-type transcriptional activator of the tcbCDEF chlorocatechol oxidative operon, and analysis of the regulatory region. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3700–3708. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.12.3700-3708.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Meer J R, van Neerven A R W, de Vries E J, de Vos W M, Zehnder A J B. Cloning and characterization of plasmid-encoded genes for the degradation of 1,2-dichloro-, 1,4-dichloro-, and 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene of Pseudomonas sp. strain P51. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:6–15. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.6-15.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Meer J R, Werlen C, Nishino S F, Spain J C. Evolution of a pathway for chlorobenzene metabolism leads to natural attenuation in contaminated groundwater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4185–4193. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.11.4185-4193.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Werlen C, Kohler H-P E, van der Meer J R. The broad substrate chlorobenzene dioxygenase and cis-chlorobenzene dihydrodiol dehydrogenase of Pseudomonas sp. strain P51 are linked evolutionarily to the enzymes for benzene and toluene degradation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4009–4016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]