Measuring biomarkers using stored serum samples is widely performed in epidemiologic and clinical studies. However, investigators may only have access to stored samples that have undergone previous freeze-thaw cycles (i.e., thawed for other laboratory tests and then frozen again for storage), potentially influencing laboratory results. Understanding the impact of freeze-thaw cycles on specific measurements is important for the appropriate interpretation of research findings when a prior freeze-thaw has occurred. Using samples collected within the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, we evaluated the stability of various biomarkers after a freeze-thaw cycle, including those representing bone-mineral metabolism (fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), parathyroid hormone (PTH), calcium (albumin was simultaneously measured for correction), phosphorus, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D)), kidney function (creatinine and cystatin C), and cardiac damage or overload (high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) and N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP)). A few previous studies have examined the impact of freeze-thaw cycles on these biomarkers but had a few caveats (1–3). They explored the stability of relatively short-term-stored samples (i.e., days to a year after sample collection), while many epidemiologic studies use samples stored for more than 10 years. Also, those studies mostly evaluated a single biomarker, precluding us from assessing the relative stability across biomarkers representing the same biological pathway (e.g., a given bone-mineral biomarker may be more stable than a different bone-mineral biomarker).

The ARIC Study enrolled 15,792 individuals from 4 US communities in 1987–1989 (4). The present evaluation is based on serum samples collected at visit 2 (1990–1992), with 14,348 participants (mean age = 57 years; 55% of participants were female, and 25% were Black) who provided informed consent. In 2019, we analyzed a random subset of serum samples (from 99 participants), which had been stored at −70 degrees Celsius since visit 2. Stored frozen serum samples were thawed and an aliquot was taken (“before freeze-thaw”), frozen at −70 degrees Celsius for >60 minutes, and thawed for measurement (“after freeze-thaw”). All tests were performed at the Advanced Research and Diagnostic Laboratory (ARDL) at the University of Minnesota. The study was approved by institutional review boards.

All paired (i.e., before and after freeze-thaw) samples were measured in the same assay batch using the following methods: a 2-site enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for intact FGF23 (Kainos, Atlanta, Georgia; laboratory interassay coefficient of variation (CV), 8.1%), a sandwich immunoassay method for intact PTH (Roche, Indianapolis, Indiana; laboratory interassay CV, 5.8%), colorimetric methods for calcium and phosphorus (laboratory interassay CVs, 1.3%–1.9%), liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry for 25(OH)D as the sum of D2 and D3 (laboratory interassay CVs, 7.5% for D2 and 5.4% for D3), a bromecresol purple method for albumin (Roche; laboratory interassay CV, 2.6%), an enzymatic method for creatinine (Roche; laboratory interassay CV, 2.9%), gentian immunoassay for cystatin C (Gentian, Moss, Norway; laboratory interassay CV, 4.3%), Gen 5 STAT for hs-cTnT (Roche; laboratory interassay CV, 3.7%), and an Elecsys proBNP II immunoassay for NT-proBNP (Roche; laboratory interassay CV, 2.6%).

We calculated the mean of each biomarker before and after freeze-thaw, and the mean absolute difference between before and after freeze-thaw. Within-subject CVs were calculated as the square root of the within-subject variance divided by the mean of before and after freeze-thaw squared. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated as the ratio of the proportion of between-subject variance to the sum of within- and between-subject variances using mixed effects model. Pearson coefficients were calculated as the covariance between before and after freeze-thaw divided by the product of their standard deviations. We also calculated the mean relative difference in percentage (%) as the absolute difference in the mean of before minus after freeze-thaw divided by the mean of before freeze-thaw. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 15 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

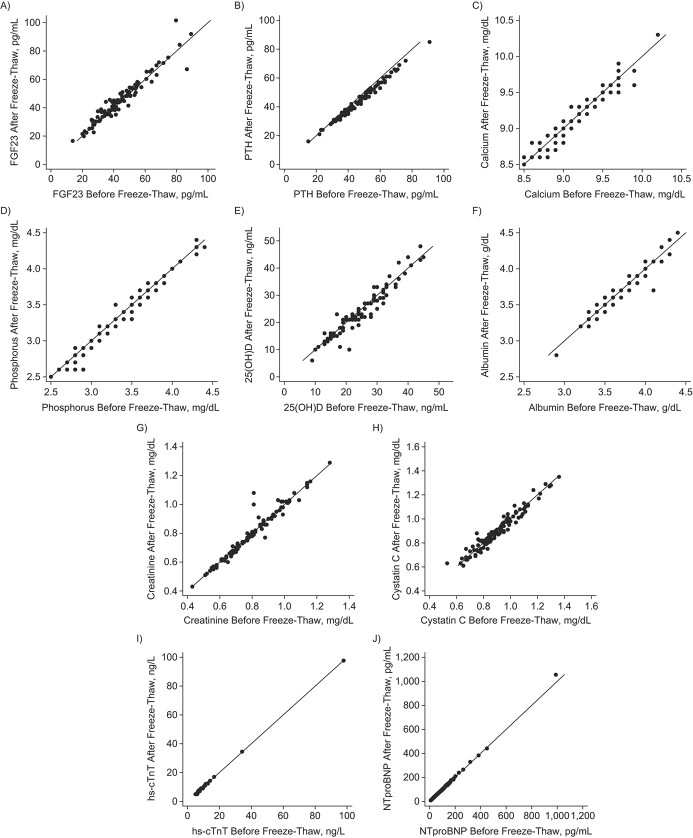

Overall, the mean difference between before and after freeze-thaw was small relative to the mean of each biomarker (Table 1). The mean relative change was less than 5% for all biomarkers tested, except for PTH (6.59%). Within-subject CV was less than 10% for all biomarkers tested, ranging from 0.8% for calcium to 9.7% for 25(OH)D. The ICC was greater than 0.950 in every biomarker, with approximately 1 for hs-cTnT and NTproBNP. Pearson coefficients were also high for all analyzed biomarkers (>0.950). Scatter plots confirmed that serum concentrations between before and after freeze-thaw were aligned with the diagonal line across the range of each biomarker (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary Statistics of Serum Analytes Before and After Freeze-Thaw Process, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities, United States, Using Samples Collected in 1990–1992

| Freeze-Thaw Study | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomarker | No. of Pairs a | Mean Before Freeze-Thaw Process | Mean After Freeze-Thaw Process | Mean Absolute Difference From Before Freeze-Thaw Process | Mean Difference Relative to Before Freeze-Thaw Process, % | Within-Subject CV (%), Mean | 10th and 90th Percentile | ICC | 95% CI | Pearson Coefficient |

| Bone mineral markers | ||||||||||

| FGF23, pg/mL | 99 | 44.4 | 45.6 | +1.15 | 2.60 | 6.3 | 0.5, 12.2 | 0.957 | 0.936, 0.971 | 0.959 |

| PTH, pg/mL | 95 | 46.4 | 43.4 | −3.06 | 6.59 | 4.8 | 1.4, 7.3 | 0.968 | 0.952, 0.978 | 0.993 |

| Calcium, mg/dL | 79 | 9.16 | 9.11 | −0.05 | 0.54 | 0.8 | 0.0, 1.5 | 0.955 | 0.930, 0.971 | 0.958 |

| Phosphorus, mg/dL | 98 | 3.38 | 3.35 | −0.04 | 1.04 | 1.7 | 0.0, 2.4 | 0.984 | 0.976, 0.989 | 0.986 |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 85 | 25.3 | 24.4 | −0.87 | 3.43 | 9.7 | 0.0, 13.9 | 0.945 | 0.922, 0.963 | 0.957 |

| Other markers | ||||||||||

| Albumin, g/dL | 98 | 3.77 | 3.74 | −0.02 | 0.61 | 1.5 | 0.0, 2.0 | 0.953 | 0.930, 0.968 | 0.957 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 98 | 0.81 | 0.81 | +0.001 | 0.16 | 3.2 | 0.0, 3.1 | 0.972 | 0.959, 0.981 | 0.973 |

| Cystatin C, mg/dL | 98 | 0.90 | 0.90 | −0.001 | 0.06 | 3.2 | 0.6, 4.9 | 0.972 | 0.959, 0.981 | 0.972 |

| hs-cTnT, ng/L | 92 | 7.30 | 7.40 | +0.10 | 1.32 | 2.5 | 0.0, 3.2 | 1.000 | 1.000, 1.000 | 1.000 |

| NTproBNP, pg/mL | 95 | 91.7 | 91.6 | −0.10 | 0.11 | 2.9 | 0.0, 4.1 | 0.998 | 0.997, 0.999 | 0.999 |

Abbreviations: 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; CI, confidence interval; CV, coefficient of variation; FGF23, fibroblast growth factor 23; hs-cTnT, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide; PTH, parathyroid hormone.

a Sample sizes differed across biomarkers due to inadequate sample volume (n = 1 for phosphorus, creatinine, and cystatin C; n = 4 for PTH and NTproBNP; n = 7 for hs-cTnT; and n = 14 for 25(OH)D). In addition, 20 samples could not be analyzed for calcium due to suboptimal batch handling.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots for serum concentrations before and after freeze-thaw cycle, using samples from Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities, United States,1990–1992. A) Fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23); B) parathyroid hormone (PTH); C) calcium; D) phosphorus; E) 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D); F) albumin; G) creatinine; H) cystatin C; I) high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT); J) N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP).

We demonstrated that biomarkers of FGF23, PTH, calcium, phosphorus, 25(OH)D, albumin, creatinine, cystatin C, hs-cTnT, and NT-proBNP were overall stable to freeze-thaw in stored serum samples (1–3). According to an empirical threshold of the mean relative difference of >10% to recommend the need for recalibration (5), our study suggests that none of the analyzed biomarkers would require recalibration for freeze-thaw. The stability is further supported by low CVs and high ICCs. A limitation of our study includes the data relying solely on a single freeze-thaw cycle. On the other hand, the present study is strengthened by our ability to assess various biomarkers using consistent methods in stored samples collected within a well-documented cohort, the ARIC Study, with a long history of high-quality data collection and specimen handling. In conclusion, we found that the bone-mineral, kidney, and cardiac biomarkers tested here were stable to a freeze-thaw cycle, a finding that is informative for designing and interpreting future clinical and translational studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study has been funded in whole or in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (contract numbers HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700005I, and HHSN268201700004I). The measurements of the biomarkers in this study were supported by Kyowa Kirin, as an ancillary study (PI: K.M.). Roche supported the assays for all biomarkers except for FGF23.

The data, analytical methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

K.M. received personal fee from Kyowa Kirin outside of the submitted work. A.B.K. is an external consultant for Roche Diagnostics and has received research funding support from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics. The other authors report no conflicts.

REFERENCES

- 1. Antoniucci DM, Black DM, Sellmeyer DE. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is unaffected by multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Clin Chem. 2005;51(1):258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Michel M, Mestari F, Alkouri R, et al. High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T: a preanalytical evaluation. Clin Lab. 2016;62(4):743–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nowatzke WL, Cole TG. Stability of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide after storage frozen for one year and after multiple freeze-thaw cycles. Clin Chem. 2003;49(9):1560–1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parrinello CM, Grams ME, Couper D, et al. Recalibration of blood analytes over 25 years in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study: impact of recalibration on chronic kidney disease prevalence and incidence. Clin Chem. 2015;61(7):938–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]