Abstract

Objective

Develop a comprehensive socially inclusive measure to assess child resilience factors.

Design

A socioecological model of resilience, community-based participatory research methods and two rounds of psychometric testing created the Child Resilience Questionnaire (parent/caregiver report, child report, school report). The parent/caregiver report (CRQ-P/C) is the focus of this paper.

Setting

Australia.

Participants

Culturally and socially diverse parents/caregivers of children aged 5–12 years completed the CRQ-P/C in the pilot (n=489) and validation study (n=1114). Recruitment via a large tertiary hospital’s outpatient clinics, Aboriginal and refugee background communities (Aboriginal and bicultural researchers networks) and nested follow-up of mothers in a pregnancy cohort and a cohort of Aboriginal families.

Analysis

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses conducted to assess the structure and construct validity of CRQ-P/C subscales. Cronbach’s alpha used to assess internal consistency of subscales. Criterion validity assessed with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) parent report.

Results

Conceptually developed CRQ comprised 169 items in 19 subscales across five socioecological domains (self, family, friends, school and community). Two rounds of psychometric revision and community consultations created a CRQ-P/C with 43 items in 11 scales: self (positive self, positive future, managing emotions), family (connectedness, guidance, basic needs), school (teacher support, engagement, friends) and culture (connectedness, language). Excellent scale reliability (α=0.7–0.9), except basic needs scale (α=0.61) (where a highly endorsed item was retained for conceptual integrity). Criterion validity was supported: scales had low to moderate negative correlations with SDQ total difficulty score (Rs= -0.2/–0.5. p<0.001); children with emotion/behavioural difficulties had lower CRQ-P/C scores (β=−14.5, 95% CI −17.5 to −11.6, adjusted for gender).

Conclusion

The CRQ-P/C is a new multidomain measure of factors supporting resilience in children. It has good psychometric properties and will have broad applications in clinical, educational and research settings. The tool also adds to the few culturally competent measures relevant to Aboriginal and refugee background communities.

Keywords: Community child health, PUBLIC HEALTH, SOCIAL MEDICINE, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of participatory methods and codesign processes to ensure content validity and a measure that is culturally and socially inclusive of diverse populations.

Use of gold-standard psychometric approaches, including confirmatory factor analysis to establish construct validity, and testing of criterion validity against the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

While the families taking part represent a cross-section of the Australian community, the measure may not work as well in other settings or communities not represented in our study.

While we were able to assess criterion validity, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire is not a gold-standard measure of resilience as no such measure was available at the time of the study.

Introduction

Children exposed to social adversity and trauma have higher risks of adverse behavioural, emotional, developmental and physical health problems.1–3 However, many children experiencing adversity have outcomes similar to peers who have not experienced the same level or type of adversity. Understanding what enables children to do well despite exposure to social adversity has been hampered by a lack of culturally and psychometrically validated measures.4 5

Much resilience research has focused on identifying individuals or populations exposed to a specific adversity and using a measure of competence (eg, academic or social) to identify individuals showing positive outcomes.6 These individuals are categorised as ‘resilient’. Thus, resilience is conceptualised as an ‘outcome’. However, a growing number of studies look at resilience as the process by which positive or protective factors mediate a child’s mental, academic or social outcomes.7–10 In an ecological–transactional model of resilience, each level of the environment—the child surrounded by their family, community and societal factors—contains risk and protective factors.11 12 Resilience can be seen as the process of drawing on available internal resources or the environment to develop, maintain or recover developmental or health outcomes, despite adversity.13–15 As a lifelong process, resilience needs to be considered within the context of life course development and across these socio-ecological domains.

Some communities, including First Nations and refugee communities, experience a significantly higher cumulative load of early life stress and adversity. This can be linked to the impacts of colonisation, persecution, experiences of war, social disadvantage and intergenerational trauma. Despite these experiences, many of these communities demonstrate resilience16–19 but are poorly represented in the existing child resilience literature—as demonstrated in a systematic review conducted as part of this study.20 The few resilience measures currently available are almost universally adult, or youth focused and developed without adequate consideration of cultural diversity.21–24

Middle childhood represents a neglected period in research and clinical work.25 A number of disorders and psychopathologies such as depression, self-injury, substance use and eating disorders commonly emerge in adolescence,26 but increasingly antecedents are being identified in childhood.27 28 Sandwiched between early childhood and adolescence, middle childhood represents a critical ‘turning point’ or transition, where appropriate intervention may significantly change a life course.25 29 Better evidence about factors supporting resilience in children experiencing adversity is essential to inform effective interventions.

A review of resilience measures conducted in 2011 stressed the lack of measures for children under 12 years.22 A more recent review identified few studies employing a psychometrically validated measure of resilience.23 Of those using validated measures, the most commonly used were the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (n=6) and the Child Behaviour Checklist (n=5), neither of which was designed to assess resilience. A systematic review of resilience factors associated with positive outcomes for adolescents in out-of-home care identified a greater number of resilience measures. The one study conducted with children (≤12 years) used a scale from the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths measure to identify resilience. Seven of the remaining 16 studies included a standardised measure of resilience factors. Four measures were cited: Resilience Scale for Children and Adolescents (individual resilience factors only), the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (a multidomain brief measure developed and tested with adolescents and adults); the Adolescent Resilience Questionnaire (a multidomain adolescent measure), and the Resilience Scale (a multidomain adult measure). Finally, a measure developed to assess the social and emotional well-being of Indigenous youth—Strong Souls—includes a resilience scale that addresses individual and social aspects of resilience.30 None of these measures was developed with children, specifically, children aged 5–12 years, nor do the measures address all domains in which resilience factors (and vulnerabilities) will exist. Greater scientific rigour and consistency in measurement tools are needed, particularly for children, including the development and validation of culturally and socially inclusive tools.22 23 31–33

This paper describes the development of the Child Resilience Questionnaire (CRQ), a culturally and socially inclusive multidimensional measure of factors supporting resilient child outcomes. Community-based participatory research methods and codesign with Aboriginal and refugee background communities34 35 were employed to create a measure with high cultural acceptability, reliability and effectiveness for use in a range of diverse contexts. A parent/caregiver, child and teacher report were developed. The objectives of this paper are to describe: (1) development of the CRQ conceptual scales and items, (2) initial pilot testing of the parent/carer version (CRQ-P/C) assessing the overall structure and performance of individual items and scales and (3) results of psychometric testing of the revised CRQ-P/C, including assessment of construct validity, criterion validity with the SDQ and internal consistency/reliability.

Methods

The study was designed to develop an inclusive, multidimensional measure of resilience in children that was relevant to a range of contexts in which children may encounter adversity and show resilience. Two methodological approaches were used to ensure participation by families with diverse social and cultural backgrounds, adversity exposures and resilience factors: (1) the questionnaire was codesigned with Aboriginal and refugee background communities, populations with high levels of historic and current discrimination, intergenerational trauma and violence exposures; and (2) families with a child suffering an illness or injury were recruited from outpatient clinics in a large public Victorian tertiary hospital. Public hospitals provide free healthcare, and the clinics are attended by large numbers of families everyday, including urban and rural-based families, with significant variation in economic, cultural and social backgrounds.

Throughout every stage of the study, the following processes were used to embed community consultation, engagement and codesign. The study was conducted in partnership with the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia, an Aboriginal family support unit in a large tertiary hospital in Victoria, and the lead provider of refugee counselling services in Victoria. These partners were involved in the funding application and study design as recommended in community consultation guidelines.36–38 Working groups involving academic and non-academic (partner) study investigators were established to codesign research processes. The Aboriginal working group involved Aboriginal researchers, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal study investigators and representatives of partner organisations. The refugee working group involved study investigators, representatives of partner organisations, staff from the hospital’s Immigrant Health Centre, refugee advocates and bicultural researchers employed on the study. Aboriginal researchers or bicultural workers were employed to work with their communities and networks to advertise the study and recruit families. As a member of the community, they ensured that the recruitment, consent and questionnaire administration were conducted in ways that promoted cultural safety and trust, including speaking to families in their preferred language.

At each stage of the study, informed parent/caregiver written or verbal consent was required for participation, and parent/caregiver written or verbal consent was required for each child’s participation. Participants were given a copy of the information statement, including contact details of study researchers. Researchers went through the study information statement with the family, covering the purpose of the study, confidentiality, use of the data, etc. Researchers answered any questions, and parents wishing to participate then signed the consent form or verbally consented, with the researcher signing a verbal consent form on their behalf (important in Aboriginal and refugee background communities where language and literacy barriers can exist). Where parents gave signed consent for a child to participate, the child was also asked if they were happy to participate (informed assent).

The three stages in the development of the CRQ-P/C will be discussed in turn: (1) generation of potential items and development of conceptual subscales, (2) pilot testing of draft items and (3) refinement and validation of final CRQ-P/C.

Development of conceptual scales and items

The draft CRQ was developed based on an ecological–transactional model of resilience, with input sought from diverse population groups to ensure variation in the type and severity of adversity experienced and the individual, family and community-level resilience factors that would be identified. The recruitment and conduct of discussion groups have been described elsewhere.39 In brief, resilience factors were identified in a systematic review of the existing literature20 and in discussion groups with people working with higher risk families and parents and children of diverse backgrounds. These factors were grouped by the first author into socioecological domains (individual, family, friends, school and community). Conceptual scales and items were codesigned and three versions were created; a parent/caregiver version (CRQ-P/C) for children aged 5–12 years; a self-report version for children aged 7–12 years (CRQ-C) and a school staff version for children aged 5–12 years (CRQ-S). All development processes involved iterative consultation and community engagement as described above. While space limits this paper to describing the CRQ-P/C, publication of the CRQ-C and CRQ-S will follow.

Pilot study to test draft CRQ-P/C

Parents/caregivers of children aged 5–12 years from diverse backgrounds and contexts in which children may encounter adversity and show resilience were recruited from four sources from June to December 2016.

Aboriginal families were recruited via the community networks of Aboriginal investigators and researchers based in South Australia. Parents/caregivers of Aboriginal children were invited to complete the draft CRQ-P/C on paper.

The draft CRQ-P/C was included in a pilot follow-up questionnaire completed by mothers/carers of Aboriginal children aged 5–7 years in the Aboriginal Families Study, a community-based birth cohort of 344 Aboriginal families recruited in South Australia.

Families of refugee background were recruited via community networks of bicultural researchers in four diverse communities: Assyrian Chaldean (from Iraq and Syria), Karen (from Burma), Tamil (from Sri Lanka) and Sierra Leone families (from Sierra Leone). Families completed the CRQ-P/C on paper in English, Karen and Arabic with assistance from the bicultural researcher as needed.

Representing the ‘general’ population, urban and rural families from diverse economic, cultural and social backgrounds were recruited in specialist outpatient clinics at a large tertiary children’s hospital. Families in the waiting areas were invited to complete the CRQ-P/C on paper while waiting for their child’s appointment.

Validation study

As above, parents/caregivers of children aged 5–12 years from diverse backgrounds and a range of settings in which children may encounter adversity and show resilience were recruited between September 2017 and March 2020:

Aboriginal families were recruited via community networks of Aboriginal investigators and researchers and completed the CRQ-P/C on iPad or paper. The CRQ-P/C was completed by mothers/caregivers of study children participating in the Aboriginal Families Study.

Refugee background families were recruited via the community networks of the bicultural workers in four diverse communities: Assyrian Chaldean (from Iraq and Syria), Hazara (from Afghanistan), Karen (from Burma and Thailand); Sierra Leone families (from Sierra Leone). Parents/carers completed the CRQ-P/C on iPad or paper in English, Karen, Arabic or Dari as preferred.

Representing the ‘general’ population, urban and rural-based families with diverse economic, cultural and social backgrounds were recruited in the specialist clinics of a tertiary children’s hospital. Parents/carers were randomised to complete the CRQ-P/C on iPad or paper.

A sample of families were recruited via a pregnancy cohort study of 1507 first-time mothers, followed up over 10 years (Maternal Health Study). Child exposure to intimate partner violence has been investigated in this cohort, with 1 in three exposed to IPV by age 10.40 Mothers were invited to complete the CRQ-P/C using an online REDCap survey.

Measures

Child Resilience Questionnaire

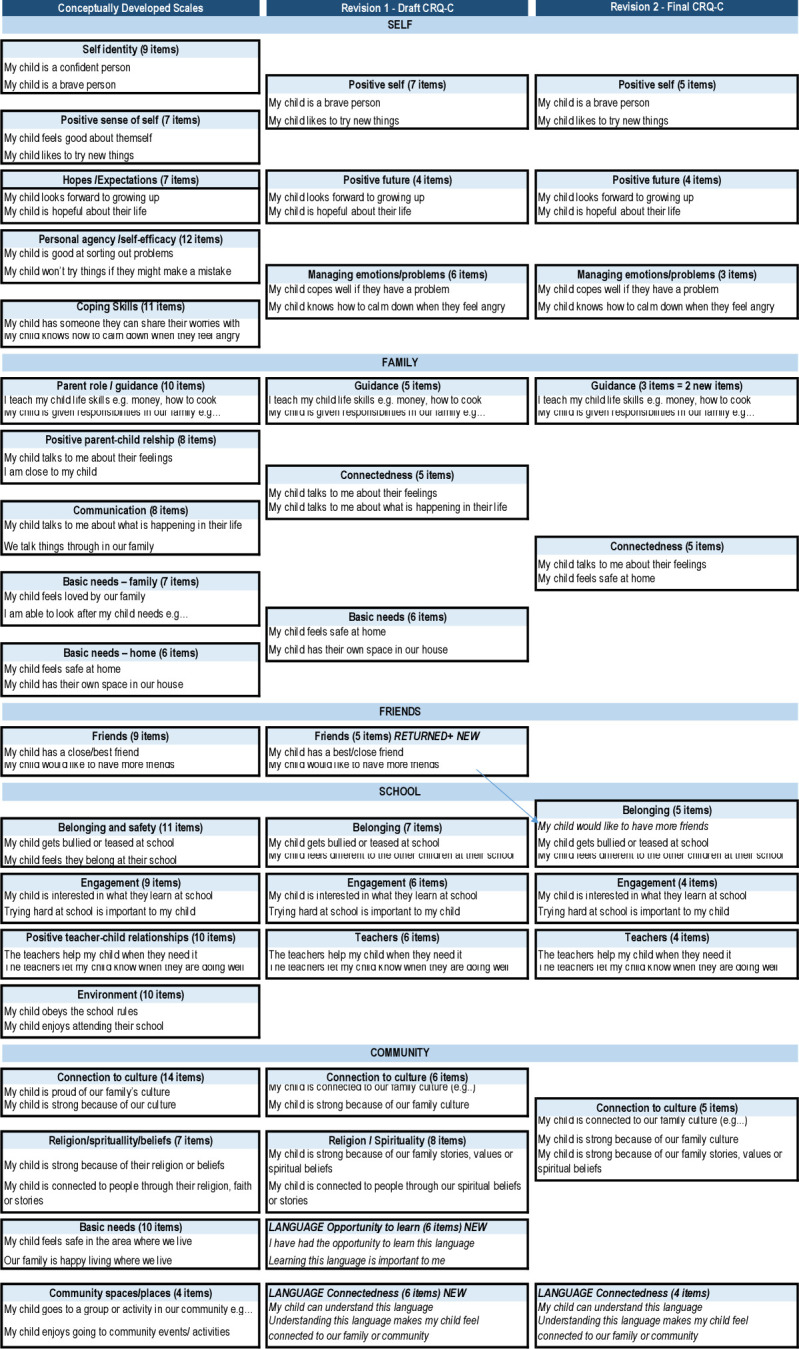

The CRQ-P/C comprises multiple scales across the individual, family, school and community domains. Figure 1 provides an outline of the domains, subscales and example items in the draft CRQ-P/C, pilot and final CRQ-P/C. The conceptually developed draft CRQ-P/C was over inclusive for testing purposes, with 169 items in 19 subscales.

Figure 1.

CRQ-P/C scale progression from conceptual scales to final version. CRQ-P/C, Child Resilience Questionnaire (parent/caregiver report).

Parents/carers were asked, ‘How often are the following true for your child?’, with response options 0 ‘not at all, 1 ‘not often’, 2 ‘sometimes’, 3 ‘most of the time’ 4 ‘all of the time’. To support respondents with limited literacy and/or familiarity with research questions, response options were accompanied by a pictogram of a glass that was empty (‘not at all’) through to a full glass (‘all of the time’). The CRQ-P/C was available in English, Arabic, Karen and Dari. Translations were conducted by accredited translators. The translated versions were assessed by study bicultural workers and revised to ensure words and language style were appropriate for the local community involved.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

As the most common measure of child resilience at the time of the study, the SDQ was included to test criterion validity. The measure comprises 25 statements on a 3-point scale (0=not true to 2=certainly true) assessing emotional and behavioural difficulties. Six subscales assess emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity and inattention, peer problems and prosocial behaviours. The SDQ total difficulty score is calculated based on the first five subscales, with higher scores indicating more difficulties. A predefined cut-off score of ≥14 was used to classify children scoring in the clinical range based on Australian norms.41 42

Analysis

Analyses of data collected in the pilot study and validation study were conducted iteratively. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise characteristics of the children (subject) and the parents/carers (respondent) completing the questionnaire.

Pilot study

The distribution of item responses and missing data were examined. Items were removed if they had limited response sets, were highly skewed, or had a high proportion of missing data. Exploratory factor analyses (EFA) using maximum likelihood and varimax rotation in SPSS was then used to examine the factor structure within each domain.43 Determination of the number of factors and items to retain was guided: by eigenvalues >1 (Kaiser’s rule), scree plot, variance explained by the model, pattern of factor loadings, interpretability of the scale and the conceptual underpinning of the scales.44 45

Validation study

The revised CRQ-P/C was employed in the validation study. Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted using MPlus with robust maximum likelihood estimation on the covariance structures on the scales within each domain. The adequacy of the models was assessed using goodness-of-fit χ2, and practical fit indices including the Comparative Fit Index, Goodness-of-Fit index and Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit index with estimates of 0.90 or above indicating acceptable model fit.46 The root mean square error of approximation with values close to or below 0.05 within the 90% CI also indicated good model fit.45 Standardised factor loadings, standardised residual covariances and modification indices were examined to identify model misfit. All modifications were theoretically driven based on the relevance of items to the scale and degree of redundancy.43–45

Internal scale consistency was examined using Cronbach Alpha, with 0.7–0.9 deemed good to excellent.47 48 Finally, criterion validity of the CRQ-P/C was assessed by examining the Pearsons’ rank correlation between CRQ scale scores and SDQ total score.43 44 48

Patient and public involvement

This study grew from community consultations being conducted in Aboriginal communities in rural, regional and remote South Australia. Community members wanted to better understand why some children and families were doing well, while others in similar situations were not doing so well. Representatives from the public were consulted at each stage. For example, the study recruitment and conduct of the study were guided by an Aboriginal advisory group, an Aboriginal working group and a refugee background working group, each of which included community members. Community Aboriginal staff and bicultural workers were employed to guide and conduct the research and consult on the findings at each stage. Authors on this paper include representatives from all of these groups (with the exception of our bicultural workers).

Results

Participants

The recruitment sources and social characteristics of the children (subject) and their parents/carers (respondents) are outlined in table 1 for the pilot and validation studies. The majority of children were Australian born, with a mean age of 9.7 (SD 1.6) in the pilot and 9.1 (SD 2.3) in the validation study, with slightly more boys than girls (52.8% compared with 47.2% in the validation sample). Targeted recruitment in the pilot and validation studies were successful in engaging a significant proportion of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander families (13.7 and 22.3, respectively) and refugee background families (17.6% and 10.0%, respectively).

Table 1.

Description of recruitment and participants

| Pilot study | Validation study | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Respondents | ||

| Recruitment source | ||

| Hospital specialist clinics | 339 (69.3) | 499 (44.8) |

| Refugee background communities | 86 (17.6) | 111 (10.0) |

| Aboriginal communities | 18 (3.7) | 71 (6.4) |

| Aboriginal mother–child cohort | 46 (9.4) | 165 (14.8) |

| General population mother–child cohort | 268 (24.1) | |

| Questionnaire format | ||

| Paper | 489 (100) | 271 (24.3) |

| iPad | 588 (52.8) | |

| Online (REDCap) | 255 (22.9) | |

| Self-reported gender | ||

| Female | 391 (81.6) | 938 (84.7) |

| Male | 88 (18.4) | 170 (15.3) |

| Continent of birth | ||

| Australia | 330 (69.0) | 807 (72.7) |

| Asia | 97 (20.3) | 199 (17.9) |

| Europe | 22 (4.6) | 54 (4.9) |

| Africa | 25 (5.2) | 35 (3.2) |

| North America | 2 (0.4) | 9 (0.8) |

| South America | 2 (0.4) | 6 (0.5) |

| CRQ-P/C Target child | ||

| Australian born | ||

| Yes | 244 (76.5) | 988 (89.2) |

| No | 75 (23.5) | 120 (10.8) |

| Child gender | ||

| Female | 439 (47.2) | |

| Male | 491 (52.8) | |

| Age mean (SD) | 9.7 (1.6) | 9.1 (2.3) |

| 5–6 years | 6 (1.8) | 230 (20.8) |

| 7–8 years | 86 (25.2) | 225 (20.3) |

| 9–10 years | 132 (38.7) | 240 (21.7) |

| 11–12 years | 111 (32.6) | 410 (37) |

| 13 years | 6 (1.8) | 3 (0.3) |

| Aboriginal &/or Torres Strait Islander | 67 (13.7) | 247 (22.3) |

| Community (refugee background families) | ||

| Assyrian Chaldean (Iraq, Syria) | 30 (34.9) | 29 (26.1) |

| Karen (Burma, Thailand) | 25 (29.1) | 30 (27.0) |

| Sierra Leone (Sierra Leone) | 16 (18.6) | 22 (19.8) |

| Tamil (Sri Lanka) | 15 (17.4) | – |

| Hazara (Afghanistan) | – | 30 (27.0) |

| Years in Australia (refugee background families) | ||

| Born in Australia | 15 (25.0) | 33 (31.1) |

| 1–2 years | 10 (16.7) | 33 (31.1) |

| 3–5 years | 16 (26.7) | 21 (19.8) |

| 6+ years | 19 (31.6) | 19 (17.9) |

| Total | 489 (100) | 1114 (100) |

CRQ-P/C, Child Resilience Questionnaire (parent/caregiver report).

Pilot study—testing of items and CRQ-P/C structure

The conceptually developed draft CRQ-P/C comprised 19 scales and 169 items. Examination of item distributions, missing values and participant feedback guided the exclusion of 74 items (self-domain–15; school-17, family-41; community-1). A very brief description of the factor analyses is provided below, with comprehensive details prioritised for the validation study. (Factor solutions, item loadings and a record of decisions are detailed in online supplemental table 1).

bmjopen-2022-061129supp001.pdf (126KB, pdf)

Self: a seven-factor solution was identified explaining 54.8% of the variance in scores. A four-factor solution was retained based on criteria described above. The factors reflected Positive self, Positive Future, Managing emotions/problems (positive) and Managing emotions (negative) (see figure 1). A number of items were removed due to low communalities or low/multiple factor loadings. Given the conceptual overlap, the three-item factor managing emotions (negative) was dropped, and a three-factor solution was accepted for validation.

Family: a six-factor solution was identified, explaining 54.5% of the variance in scores. Four of the six conceptually developed scales were accepted for validation connectedness, guidance, basic needs and friends. Three items were dropped for loading on multiple factors. Two items in the connectedness scale also loaded on the basic needs factor (I listen to my child, I am close to my child). These items were retained as seen as conceptually important in consultations. The Friends scale had only two items loading at >0.4 and was revised for validation.

School: a six-factor solution was identified explaining 59.1% of the variance in scores, with the first three factors retained reflecting Belonging, Engagement, Teacher support scales. One item identified as ambiguous/difficult to answer by respondents was deleted, and two items with low factor loadings were dropped.

Community: A six-factor structure was identified, explaining 61.4% of the variance. Three scales were retained—Connection to culture, Religion and Spiritualty and Community (see figure 1). Five items were deleted due to low loadings and/or conceptual overlap. In consultations, it was agreed that Connection to culture and Community scales also overlapped conceptually. Connection to culture was retained as more congruent with the resilience literature, while Community appeared to be more related to what could be considered socio-economic factors (eg, having green spaces, feeling safe in your community). Other changes made in this domain are described below.

Consultation-driven revisions: working group, community and investigator consultations on the face and content validity of the revised CRQ resulted in three further alterations:

The community/culture domain was developed to capture resilience factors that were broadly relevant—not limited to overseas born or Aboriginal families. However, many respondents indicated they ‘didn’t have a culture’ and skipped the section (mean missing data were 7.0 (SD=11.4) compared with 3.9 (SD=10.1) in self-domain or 5.1 (SD=11.6) in the school domain). A preamble was added asking respondents to tick a list of factors important to their family that reflected a diverse interpretation of culture (eg, the food you eat, family celebrations, family traditions, religion). It was hoped this would highlight the broad relevance of the section and encourage completion.

Language as a connection to culture was identified as a gap in the revised CRQ in consultations. Therefore, two new language scales (Opportunity to learn and Connectedness) were created for multilingual families through iterative consultations (see figure 1).

Peer relationships are known to be associated with resilience,20 but the two scales addressing them (Friends and School Belonging) did not form strong scales. These scales were revised and expanded through an iterative process of consultation and included in the school domain (see figure 1).

Validation study

The revised CRQ-P/C comprised 81 items in 15 subscales (see figure 1). Scale items, item descriptives (mean, SD, skewness and kurtosis), initial and final confirmatory factor model fit and loadings are provided in table 2 (self and family domains) and table 3 (school and community domains). Actions taken to improve model fit in CFA are described below.

Table 2.

CRQ-P/C item summary, including standardised factor loadings from initial and final confirmatory factor models (CFA) for the SELF and FAMILY domains (n=1111)

| Domain | Model fit/factor loadings | ||||||

| Item | N | M (SD) | Skew | Kurt | Initial congeneric CFA | Final congeneric CFA | |

| SELF | |||||||

| Self-Identity | χ2 (14)=124.20, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.09 (.07,.10); CFI*=0.98; TLI*=0.98 | χ2 (5)=37.76, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.08 (.06,.10); CFI=0.99; TLI=0.99 | |||||

| 1 | My child feels good… | 1110 | 3.1 (0.6) | −0.4 | 3.5 | 0.75 | – |

| 2 | My child keeps trying … | 1107 | 2.8 (0.8) | −0.3 | 2.8 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| 3 | My child is a strong… | 1105 | 3.1 (0.8) | −0.6 | 3.2 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| 4 | My child is a confident… | 1108 | 2.9 (0.8) | −0.5 | 3.0 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| 5 | My child likes to try… | 1111 | 3.0 (0.9) | −0.6 | 2.6 | 0.69 | 0.70 |

| 6 | My child is a brave … | 1107 | 3.1 (0.8) | −0.7 | 3.1 | 0.76 | 0.78 |

| Positive future | χ2 (2)=22.90, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.10 (.07,.14); CFI=0.99; TLI=0.99 | No modifications | |||||

| 1 | My child is positive about … | 1109 | 3.2 (0.8) | −0.7 | 3.5 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| 2 | My child looks forward to… | 1109 | 3.2 (0.8) | −0.9 | 3.5 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| 3 | My child is hopeful … | 1108 | 3.3 (0.7) | −1.0 | 4.2 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| 4 | My child is positive … | 1102 | 3.3 (0.7) | −0.8 | 3.5 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| Managing emotions/problems | χ2 (9)=184.67, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.14 (.12,.16); CFI=0.99; TLI=0.97 | No fit indices for 3-item model | |||||

| 1 | My child thinks about the reasons … | 1107 | 2.8 (0.9) | −0.4 | 2.9 | 0.33 | – |

| 2 | My child knows how to manage … | 1109 | 2.4 (0.9) | −0.3 | 2.9 | 0.84 | – |

| 3 | My child copes well … | 1108 | 2.5 (0.9) | −0.5 | 3.3 | 0.83 | 0.77 |

| 4 | My child knows how to calm … | 1108 | 2.4 (1.0) | −0.3 | 2.8 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| 5 | My child knows how to manage … | 1107 | 2.5 (0.9) | −0.3 | 3.1 | 0.91 | 0.94 |

| 6 | My child worries about … | 1104 | 2.0 (1.0) | −0.1 | 3.0 | 0.04 | – |

| FAMILY | |||||||

| Connectedness | χ2 (5)=167.22, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.18 (.16,.20); CFI=0.98 TLI=0.97. | χ2 (2)=3.30, p=0.192; RMSEA=0.03 (.00,.07); CFI=1.00; TLI=1.00 | |||||

| 1 | My child talks to me about … | 1075 | 3.1 (0.8) | −0.7 | 3.5 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| 2 | I listen to my child … | 1069 | 3.6 (0.6) | −0.8 | 3.0 | 0.61 | – |

| 3 | My child talks to me about their feelings … | 1072 | 3.2 (0.8) | −0.9 | 3.8 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| 4 | My child talks to me about their worries… | 1068 | 3.1 (0.9) | −0.8 | 3.4 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| 5 | I am close … | 1071 | 3.7 (0.5) | −1.8 | 6.6 | 0.75 | 0.70 |

| Basic needs | χ2 (9)=42.50, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.06 (.04,.08); CFI=0.99; TLI=0.98 | χ2 (2)=4.00, p=0.135; RMSEA=0.03 (.00,.08); CFI=1.00; TLI=0.99 | |||||

| 1 | My child likes being … | 1073 | 3.5 (0.6) | −1.3 | 5.3 | 0.71 | – |

| 2 | My child feels safe … | 1070 | 3.8 (0.5) | −2.3 | 8.6 | 0.77 | 0.67 |

| 3 | My child feels they belong… | 1070 | 3.7 (0.6) | −2.1 | 8.6 | 0.82 | – |

| 4 | Our family has routines … | 1068 | 3.4 (0.7) | −1.0 | 3.5 | 0.58 | 0.61 |

| 5 | My child feels special … | 1069 | 3.4 (0.8) | −1.5 | 6.1 | 0.75 | 0.79 |

| 6 | My child has own space… | 1068 | 3.5 (0.8) | −2.1 | 7.4 | 0.58 | 0.60 |

| Guidance | χ2 (2)=10.03, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.06 (.03,.10); CFI=1.00; TLI=0.99 | No fit indices for 3-item model | |||||

| 1 | My child is given responsibilities … | 1073 | 2.8 (1.0) | −0.6 | 2.8 | 0.73 | 0.72 |

| 2 | My child helps with things like … | 1068 | 2.8 (1.0) | −0.3 | 2.3 | 0.79 | 0.82 |

| 3 | Our family talks about … | 1068 | 3.6 (0.6) | −1.5 | 5.1 | 0.51 | – |

| 4 | I teach my child life … | 1071 | 3.3 (0.8) | −1.0 | 3.4 | 0.75 | 0.73 |

CFI, Comparative Goodness of Fit Index; CRQ-P/C, Child Resilience Questionnaire (parent/caregiver report); RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; TLI, Tucker Lewis Index.

Table 3.

CRQ-P/C item summary, including standardised factor loadings from initial and final confirmatory factor models (CFA) for the SCHOOL and COMMUNITY domains (n=1111)

| DOMAIN | Model fit/factor loadings | ||||||

| Item | N | M (SD) | Skew | Kurt | Initial congeneric CFA | Final congeneric CFA | |

| SCHOOL | |||||||

| Teachers | χ2 (9)=177.93, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.14 (.12,.15); CFI=0.98; TLI=0.97 | χ2 (2)=28.89, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.12 (.08,.15); CFI=1.00; TLI=0.99 | |||||

| 1 | The teachers help … | 1084 | 3.3 (0.8) | −0.9 | 3.5 | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| 2 | The teachers listen to …. | 1081 | 3.1 (0.8) | −0.8 | 3.3 | 0.84 | 0.88 |

| 3 | My child’s school/teachers celebrate … | 1078 | 3.3 (0.8) | −1.1 | 4.0 | 0.74 | – |

| 4 | My child has a teacher they can … | 1075 | 3.0 (1.0) | −0.9 | 3.3 | 0.75 | 0.76 |

| 5 | The teachers let my child know … | 1078 | 3.2 (0.8) | −0.8 | 3.4 | 0.81 | 0.75 |

| 6 | The teachers are fair … | 1070 | 3.2 (0.8) | −1.0 | 4.5 | 0.70 | – |

| Engagement | χ2 (9)=99.86, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.10 (.08,.12); CFI=0.98; TLI=0.97 | χ2 (2)=25.41, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.10 (.07,.15); CFI=0.99; TLI=0.98 | |||||

| 1 | My child likes learning … | 1095 | 3.2 (0.8) | −1.0 | 3.7 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

| 2 | My child doesn’t like … | 1082 | 3.2 (1.0) | −1.2 | 3.8 | 0.63 | – |

| 3 | My child is interested … | 1081 | 3.2 (0.8) | −0.9 | 3.4 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| 4 | Trying hard at school … | 1077 | 3.0 (1.0) | −0.8 | 3.2 | 0.68 | 0.71 |

| 5 | My child finishes work … | 1061 | 2.8 (0.9) | −0.6 | 2.9 | 0.64 | 0.65 |

| Belonging PLUS Friend scale | χ2 (35)=607.70 p<0.001; RMSEA=0.13 (.12,.14); CFI=0.92; TLI=0.90 | No fit indices for 3-item model | |||||

| 1 | My child gets bullied … | 1083 | 3.0 (1.0) | −0.7 | 3.1 | 0.58 | – |

| 3 | My child feels comfortable … | 1073 | 3.2 (1.0) | −1.4 | 4.8 | −0.39 | – |

| 4 | My child feels different … | 1075 | 3.0 (1.1) | −0.7 | 2.8 | 0.61 | – |

| 5 | My child gets in trouble …. | 1081 | 3.2 (0.9) | −1.1 | 4.0 | 0.31 | – |

| 6 | My child is lonely … | 1066 | 3.2 (0.9) | −1.2 | 3.9 | 0.80 | – |

| 7 | My child finds it hard … | 1090 | 2.9 (1.1) | −0.7 | 2.8 | 0.73 | – |

| 8 | My child would like to … | 1073 | 1.9 (1.2) | −0.0 | 2.1 | 0.48 | – |

| 9 | My child has a group of friends … | 1081 | 3.3 (0.8) | −1.1 | 4.4 | −0.83 | 0.81 |

| 10 | My child has a friend they can … | 1067 | 2.7 (1.1) | −0.6 | 2.8 | −0.67 | 0.75 |

| 11 | My child has a best … | 1077 | 3.2 (1.0) | −1.3 | 4.3 | −0.78 | 0.90 |

| COMMUNITY | |||||||

| Culture | χ2 (27)=568.07, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.14 (.13,.15); CFI=96; TLI=0.94 | χ2 (2)=33.3, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.13 (.09,.17); CFI=0.99; TLI=0.98 | |||||

| 1 | My child is strong because … | 1029 | 2.9 (0.9) | −0.9 | 3.9 | 0.78 | 0.83 |

| 2 | My child is connected … | 1025 | 3.0 (0.9) | −0.9 | 3.7 | 0.80 | 0.81 |

| 3 | My child can deal with problems … | 1026 | 2.8 (1.0) | −0.6 | 3.2 | 0.82 | – |

| 4 | Our family culture or values … | 1023 | 2.8 (0.9) | −0.6 | 3.2 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

| 5 | My child likes going to events … | 1011 | 3.1 (0.9) | −1.0 | 3.7 | 0.72 | – |

| 6 | My child is connected to elders … | 1020 | 3.2 (1.1) | −1.3 | 3.9 | 0.63 | – |

| 7 | My child is strong because of our family … | 1016 | 2.9 (1.0) | −0.8 | 3.2 | 0.84 | 0.79 |

| 8 | Our family culture makes my … | 1003 | 2.9 (1.0) | −0.8 | 3.2 | – | – |

| Religion/spirituality | χ2 (5)=178.83, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.19 (.17,.21); CFI=0.98; TLI=0.96 | ||||||

| 1 | My child looks to their elders … | 1008 | 2.8 (1.1) | −0.7 | 2.7 | – | – |

| 2 | My child is connected to people … | 991 | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.69 | – |

| 3 | My child is connected to people … | 997 | 2.1 (1.4) | −0.2 | 1.8 | 0.87 | – |

| 4 | My child is connected to their spirit … | 966 | 2.0 (1.4) | −0.0 | 1.7 | 0.79 | – |

| 5 | Our family talk or yarn about … | 1007 | 2.6 (1.1) | −0.6 | 2.6 | 0.84 | – |

| 6 | Our family stories or spiritual beliefs … | 994 | 2.3 (1.3) | −0.3 | 2.1 | 0.89 | – |

| Language—opportunity to learn | Not calculated | Not calculated | |||||

| 1 | Learning this language … | 488 | 2.5 (0.7) | −1.0 | 2.9 | ||

| 2 | My child would like to learn … | 487 | 2.5 (0.6) | −1.1 | 3.0 | ||

| 3 | My child has had the opportunity … | 491 | 2.5 (0.7) | −0.8 | 2.5 | ||

| 4 | I encourage my child … | 487 | 2.7 (0.5) | −1.5 | 4.3 | ||

| Language—connectedness | χ2 (9)=123.42, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.16 (.14,.19); CFI=0.99; TLI=0.99 | χ2 (2)=15.84, p<0.001; RMSEA=0.12 (.07,.18); CFI=1.00; TLI=1.00 | |||||

| 1 | My child can speak … | 496 | 2.1 (0.6) | −0.1 | 2.4 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| 2 | My child can understand … | 493 | 2.4 (0.6) | −0.5 | 2.3 | 0.94 | 0.95 |

| 3 | A family member speaks to … | 487 | 2.5 (0.6) | −0.9 | 2.8 | 0.85 | – |

| 4 | My child understands when … | 488 | 2.4 (0.7) | −0.7 | 2.3 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| 5 | My child can easily talk to … | 487 | 2.1 (0.8) | −0.2 | 1.6 | 0.90 | – |

| 6 | My child likes to talk to … | 487 | 2.1 (0.8) | −0.2 | 1.7 | 0.91 | 0.86 |

| 7 | Understanding this language…feel special | 482 | 2.5 (0.7) | −0.9 | 2.6 | – | – |

| 8 | Understanding this language…feel connected | 483 | 2.5 (0.7) | −1.0 | 2.9 | – | – |

CRQ-P/C, Child Resilience Questionnaire (parent/caregiver report); RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

Self: the CFA for Positive Future was a good fit to the data, and all four items retained. The one factor congeneric Self-Identity model did not have good fit. This improved with removal of item 1 (poor response distribution). The CFA for Managing Emotions showed poor fit to the data. Sequential removal of three items with lowest factor loadings and/or conceptual overlap with other items resulted in a three-item subscale. The factor loadings for the remaining items were excellent (model fit indices not available for three item models).

Family: the one factor congeneric model for Connectedness was a poor fit to the data. There was also redundancy between items. Item 2 was dropped as it had the lowest factor loading. Model fit was improved, and the remaining items had excellent factor loadings. In the Basic Needs scale, the item ‘My child feels safe at our home’ was retained for conceptual integrity despite being endorsed by most respondents (poor distribution). Items 1 and 3 were very highly endorsed and overlapped conceptually with other items. Dropping these two items resulted in good model fit. Finally, the one factor congeneric model Guidance showed poor model fit indices. Item 3 was removed due to the low factor loading and potential variation and ambiguity in wording around what is right and wrong across families. The factor loadings for the remaining items were excellent.

School: the one factor congeneric models for Teacher support and Engagement had inadequate fit indices, and the items with the lowest factor loadings were dropped sequentially to achieve good fit indices. The one factor congeneric models for the Belonging and Friends scales did not fit the data. Three and four-factor CFA models were tested for this domain. The Teacher support and School engagement factors were consistent in both models, but the Belonging and Friends items were mixed. With compatibility between the two concepts, the decision was made to test a one-factor congeneric model with the Belonging and Friends items combined, retaining items that loaded on the three-factor model. Eight items were retained, but the model had very poor fit to the data. Sequential removal of the worst performing seven items did not achieve good model fit; however, the factor loadings for the remaining three items from the Friends scale were excellent (≥0.75) and this scale was retained.

Culture: the added preamble to the culture section appeared to work well, with fewer missing items (mean=1.3, SD=3.7). One item in the connectedness scale was identified in community consultations as having poor face validity and was dropped (our family culture makes my child feel special). The one factor congeneric Connectedness scale model showed poor model fit. Two items with the lowest factor loadings were removed. There was also redundancy between items 3 and 4. Item 3 was retained as it was more concisely worded. Good model fit was achieved.

The items in the Spirituality scale had the highest level of missing data (≈10%). One item with poor distribution was dropped. The one factor congeneric model of the remaining items showed very poor fit. Sequentially dropping three items with the lowest loadings or conceptual overlap was insufficient to achieve acceptable model fit. The three-item factor had poor face validity and was dropped.

An EFA was conducted to assess the underlying factor structure for the two new language scales. Scree plot and eigenvalues supported a one factor structure, explaining 21% of the variance, comprising six of the eight Connectedness scale items. A one factor congeneric model of the six items showed poor model fit. Dropping item 3 (lowest factor loading), followed by item 5 (overlapped conceptually with item 6), resulted in good model fit indices and excellent item factor loadings.

The final CRQ-P/C

The scale summary statistics and scale reliability are shown in table 4. With the exception of the Basic Needs scale in the family domain (Cronbach’s α=0.61), the final scales showed excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α=0.73 to 0.88), with high internal consistency for the questionnaire as a whole (Cronbach’s α=0.93).

Table 4.

Summary of the final scales for the Child Resilience Questionnaire—Parent/Caregiver version

| CRQ-P/C total sample | Girls (n=421) | Boys (n=471) | |||||||

| Items (range*) | n | Range | Mean (SD) | Cronbach α | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | T-test | P value | |

| SELF | |||||||||

| Positive self | 5 (0–20) | 1112 | 2–20 | 14.8 (3.3) | 0.83 | 15.2 (3.2) | 14.8 (3.3) | 2.0 | 0.042 |

| Positive future | 4 (0–16) | 1111 | 0–16 | 12.8 (2.7) | 0.87 | 13.0 (2.5) | 12.8 (2.7) | 1.1 | 0.256 |

| Managing emotions | 3 (0–12) | 1100 | 0–12 | 7.1 (2.4) | 0.86 | 7.8 (2.3) | 7.2 (2.4) | 3.6 | <0.001 |

| FAMILY | |||||||||

| Connectedness | 4 (0–16) | 1071 | 3–16 | 13.0 (2.6) | 0.85 | 13.3 (2.5) | 12.9 (2.6) | 2.0 | 0.046 |

| Basic needs | 4 (0–16) | 1070 | 6–16 | 14.1 (2.0) | 0.61 | 14.1 (2.0) | 14.1 (2.0) | −0.1 | 0.898 |

| Guidance | 3 (0–12) | 1076 | 1–12 | 8.9 (2.3) | 0.73 | 9.0 (2.3) | 8.8 (2.3) | 1.5 | 0.133 |

| SCHOOL | |||||||||

| Teacher support | 4 (0–16) | 1080 | 0–16 | 12.6 (2.8) | 0.81 | 12.7 (2.6) | 12.7 (2.8) | 0.2 | 0.811 |

| Engagement | 4 (0–16) | 1079 | 2–16 | 12.2 (2.8) | 0.81 | 12.9 (2.5) | 11.8 (3.0) | 5.4 | <0.001 |

| Friends | 3 (0–12) | 1049 | 0–12 | 9.2 (2.4) | 0.80 | 9.5 (3.3) | 9.0 (2.4) | 3.2 | 0.002 |

| CULTURE | |||||||||

| Connectedness | 5 (0–20) | 1023 | 0–16 | 11.6 (3.2) | 0.84 | 11.8 (3.3) | 11.6 (3.1) | 0.8 | 0.433 |

| Language† | 4 (0–8) | 489 | 0–8 | 4.9 (2.3) | 0.88 | 5.2 (2.3) | 4.9 (2.3) | 0.9 | 0.347 |

| CRQ total score | 39 (0–156) | 1062 | 57–152 | 115.8 (17.4) | 0.93 | 118.6 (16.7) | 115.1 (17.6) | 3.0 | 0.003 |

| CRQ total score (incl. lang)† | 43 (0–172) | 480 | 64–164 | 127.7 (18.4) | 0.93 | 130.0 (17.6) | 127.9 (18.4) | 1.2 | 0.249 |

*Response options ranged from 0 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘all of the time”, with exception of language where response options ranged from 0 ‘not at all’ to 2 ‘a lot”.

†Completed by multilingual families only.

CRQ-P/C, Child Resilience Questionnaire (parent/caregiver report).

Spearman’s rank correlations between the CRQ-P/C scales are presented in table 5. In general, correlations between the subscales were moderate and in the expected direction. Scales within the same domain tended to be more highly correlated with each other than with scales in other domains. A strong correlation was observed between the Positive Self and Positive Future scales (rs=0.66, p<0.001). As could be expected, the Culture Language subscale showed the lowest correlations with other scales, the highest correlation with the Culture Connectedness scale (rs=0.23, p<0.001) and was negatively correlated with the Family Basic Needs scale.

Table 5.

Spearman’s correlations between CRQ-P/C scales, total CRQ-P/C score and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) total score

| DOMAIN CRQ-P/C Scale |

SELF | FAMILY | SCHOOL | CULTURE | ||||||||

| Positive Self n=1112 | Positive Future n=1111 | Managing emotions n=1100 | Connectedness n=1071 | Basic needs n=1060 | Guidance n=1063 | Teacher Support n=1080 | Engagement n=1079 | Friends n=1079 | Connectedness n=1023 | Language* n=489 |

CRQ-P/C Total n=1062 | |

| SELF | ||||||||||||

| Positive future | 0.661 | |||||||||||

| Emotion regulation | 0.564 | 0.547 | ||||||||||

| FAMILY | ||||||||||||

| Connectedness | 0.413 | 0.443 | 0.323 | |||||||||

| Basic Needs | 0.282 | 0.383 | 0.225 | 0.499 | ||||||||

| Guidance | 0.249 | 0.273 | 0.200 | 0.449 | 0.402 | |||||||

| SCHOOL | ||||||||||||

| Teacher support | 0.312 | 0.319 | 0.254 | 0.349 | 0.290 | 0.241 | ||||||

| Engagement | 0.456 | 0.441 | 0.427 | 0.366 | 0.314 | 0.284 | 0.472 | |||||

| Friends | 0.373 | 0.394 | 0.403 | 0.328 | 0.282 | 0.263 | 0.380 | 0.377 | ||||

| CULTURE | ||||||||||||

| Connectedness | 0.378 | 0.362 | 0.318 | 0.429 | 0.406 | 0.356 | 0.291 | 0.304 | 0.289 | |||

| Language (n=489) | 0.159 | 0.100 | 0.116 | 0.120 | −0.021† | 0.051† | 0.072† | 0.192 | 0.001 | 0.233 | ||

| CRQ-P/C Total | 0.713 | 0.724 | 0.637 | 0.674 | 0.569 | 0.541 | 0.584 | 0.682 | 0.634 | 0.634 | 0.163 | |

| SDQ total difficulties score (n=980) | −0.332 | −0.324 | −0.531 | −0.213 | −0.207 | −0.152 | −0.195 | −0.394 | −0.449 | −0.217 | −0.051 | −0.471 |

*Completed by multilingual families only.

†Nonsignificant p value (>0.05).

CRQ-P/C, Child Resilience Questionnaire (parent/caregiver report).

Parents/caregivers rated girls higher on average than boys on five subscales: Positive self, Managing Emotions, Family Connectedness, School Engagement and Friends (see table 4). Overall, the CRQ-P/C mean total score (excluding the Culture—Language scale) for boys was lower than for girls (t839=3.0, p=0.003).

Criterion validity

Criterion validity of the CRQ-P/C was assessed using the SDQ. All CRQ-P/C scales showed low to moderate negative correlations with the SDQ total difficulty score. As would be expected given the content of the SDQ, the Emotion Regulation and Friends scales were the most highly correlated (rs=−0.53 and rs=−0.45, respectively). The total CRQ-P/C score was moderately negatively correlated with the SDQ total difficulty score (rs=−0.47).

Almost one in five children (18.4%) was identified as having clinically significantly symptoms on the SDQ (total difficulties score ≥14). The mean CRQ-P/C total resilience score for children identified as having emotional and/or behavioural difficulties was lower than for children without difficulties (mean=103.4, SD=18.7 and 119.3, SD=15.5, respectively). Linear regression analysis identified children with difficulties scored lower on average on the CRQ-P/C by 14 points (β=−14.5, 95% CI −17.5 to −11.6, p<0.001), after adjusting for child gender.

Discussion

Extensive community-based participatory research methods ensured that the CRQ has good content validity and addresses a broad range of factors that can support child resilience across diverse contexts. The pilot testing and validation involved large samples, with targeted recruitment of families from diverse backgrounds, including families known to experience greater social disadvantage, adversity and resilience.49 50 The final CRQ-P/C comprises 10 scales across the domains of self, family, school and culture, with 43 items in total. Good psychometric properties were attained. Subscale internal consistency reliability was excellent apart from the family Basic needs scale, which was adequate. Construct validity was supported, with all scales showing moderate negative correlation with the SDQ total difficulties score, and significantly lower mean resilience scores for children identified as having emotional and/or behavioural difficulties.

Several aspects of the CRQ-P/C are important for note. (1) Two scales in the Self-domain—Positive self and Positive future—were strongly correlated (rs=0.66). Further research is required to determine if it is sufficient to retain just one of these scales and (2) the family Basic needs scale showed only adequate internal consistency reliability (0.61), and almost a third of children (31%) were scored at the top of the scale range. Community consultations stressed that meeting basic family needs is a key factor underpinning child resilience. The scale addresses feeling safe at home, having routines, feeling special in your family and having your own space in the place where you live. Despite very high positive endorsement, the item ‘I feel safe in my family’ was retained for conceptual integrity. Children who are scored lower in this domain may be a particularly vulnerable group, with further research required to corroborate this. 3) The importance of cultural factors for resilient outcomes is not new.19 20 51–53 What is new is the assessment of connectedness to culture and language as a connection to culture/community. Efforts were also made to assess potential strengths associated with a child’s connection to religious and/or faith communities/institutions. Religion/spirituality was identified as potentially supporting child resilience in consultations, with mixed findings in the literature focused on adolescents or adults.20 The spirituality/religion scale was unsuccessful. A high proportion of respondents skipped these items or, alternatively, responded with strong positive or negative endorsement of all items. It may be too disparate a factor to capture in a single scale, or a more distal factor for children than for adolescents or adults. Finally, the friends scale was not strongly consistent across the revisions but showed excellent scale reliability with three items. While friendships in middle childhood have been highlighted as developmentally important25 and associated with positive self-worth and school engagement,54 most investigation in terms of resilience has been with adolescents.55–57 Availability of the multidomain CRQ will facilitate investigation of the importance of specific resilience factors, such as friends, in different contexts (eg, Aboriginal families) or adversities (eg, family violence exposure) to advance our understanding of child resilience and how to support positive outcomes in the face of adversity.

Strengths of our study include use of participatory methods and co-esign processes to ensure content validity and cultural acceptability and gold-standard psychometric approaches, including confirmatory factor analysis to establish construct validity and testing of criterion validity against the SDQ.23 In addition, we recruited culturally diverse participants and employed a range of approaches to community consultation and codesign to ensure cultural validity of the CRQ-P/C. While our study has many strengths compared with previous research, there are important limitations to note. Our focus was children aged 5–12, and the measure may not be appropriate for use outside this age range. While the families taking part represent a cross-section of the Australian community, the measure may not work as well in other settings, or in communities not represented in our study, for example, First Nation populations in other countries or refugee background communities not included in the development of the questionnaire. While we were able to assess criterion validity using the SDQ as a proxy measure of resilience, this is not a measure of resilience. No such measure existed at the time of the study. Further assessment against new resilience measures will enable more rigorous assessment. It was beyond the scope of this paper to report on the child report CRQ (CRQ-C) against the CRQ-P/C, but this is underway. Assessment of test–retest reliability and the psychometric properties of the CRQ-P/C in different populations, child ages and contexts are also planned.

Conclusion

Resilience was originally seen as a static characteristic of an individual—unique heroic figures achieving remarkable things despite tragic childhoods. It is now better conceptualised as a more ‘ordinary magic’13—a dynamic process of drawing on internal and external resources to adapt, recover or thrive despite adverse experiences. Thus, children who have access to resilience factors within themselves, and in their family, school and community will fare better in the face of adversity than children who are not similarly resourced. The CRQ-P/C is the first culturally and socially inclusive, multidomain measure of child resilience that reflects this paradigm shift. The measure will facilitate investigation of a child’s strengths or vulnerabilities across different aspects of their socioecological world. Availability of the first developmentally appropriate child measure with demonstrated content, construct validity, reliability and criterion validity will facilitate understanding of resilience across settings, contexts, adversities and countries.

Socially inclusive and culturally appropriate research methods and tools are fundamental to creating the evidence needed to guide interventions to support child resilience across diverse contexts and settings. This tool expands the extremely limited number of culturally inclusive measures available for use with Aboriginal and refugee background children.

The CRQ-C/P will support more complex and nuanced examinations of child resilience, with wide ranging applications including in: clinical settings for starting conversations with families about a child’s strengths and potential vulnerabilities; evaluation of programmes aimed at building child resilience; and finally, in child resilience research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all the families who participated and made this project possible, and the Aboriginal researchers (additional to the authors) and bicultural workers who developed study processes, collected data in their communities, and guided interpretation of findings throughout the study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @_elisha_riggs

Collaborators: Childhood Resilience Study Collaborative Group: Professor Helen Herman, Professor Kelsey Hegarty, A/Professor Jane Yelland, Ms Amanda Mitchell, Ms Selena White, Ms Tanya Koolmatrie, Ms Sue Casey, Mr Josef Szwarc, A/Professor Georgie Paxton

Contributors: DG, ER, RG, KG, SJB conceptualised the study; DG, ER, RG, KG, DW, MS, SM, SJB and the CRS collaborative group co-designed this study. DG, ER, DW, SM facilitated discussion groups and undertook data collection for the discussion groups, pilot study and/or validation study; DG, RG conducted the analyses for this paper; DG, ER, RG, KG, DW, MS, SM, SJB and Childhood Resilience Study Collaborative Group interpreted the data; DG drafted the paper. All authors critically revised the paper, approved the manuscript to be published and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work. DG accepts full responsibility for the finished work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. DG is the guarantor of this work.

Funding: This work was supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council: Project Grants (#1064061, #1105561); Research Fellowship (SJB #1103976); Career Development Fellowship (RG #1109889); and the Safer Families CRE (DG #1198270); and the Myer Family Foundation (# N/A). Research conducted at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute is supported by the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure program.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Contributor Information

Members of the Childhood Resilience Study Collaborative Group:

Helen Herman, Kelsey Hegarty, Jane Yelland, Amanda Mitchell, Selena White, Tanya Koolmatrie, Sue Casey, Josef Szwarc, and Georgie Paxton

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s)

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for all stages of the study was obtained from Royal Children’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (#34142, 34220,36142,37167A) and the South Australian Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee (04-14-585), and protocols were submitted for approval by study partner Victorian Foundation for the Survivors of Torture. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Kimber M, McTavish JR, Couturier J, et al. Consequences of child emotional abuse, emotional neglect and exposure to intimate partner violence for eating disorders: a systematic critical review. BMC Psychol 2017;5:33. 10.1186/s40359-017-0202-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, et al. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e356–66. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kalmakis KA, Chandler GE. Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: a systematic review. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2015;27:457–65. 10.1002/2327-6924.12215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Khanlou N, Wray R. A whole community approach toward child and youth resilience promotion: a review of resilience literature. Int J Ment Health Addict 2014;12:64–79. 10.1007/s11469-013-9470-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Herrman H, Stewart DE, Diaz-Granados N, et al. What is resilience? Can J Psychiatry 2011;56:258–65. 10.1177/070674371105600504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fraser E, Pakenham KI. Resilience in children of parents with mental illness: relations between mental health literacy, social connectedness and coping, and both adjustment and caregiving. Psychol Health Med 2009;14:573–84. 10.1080/13548500903193820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suárez-Soto E, Pereda N, Guilera G. Poly-victimization, resilience, and suicidality among adolescents in child and youth-serving systems. Child Youth Serv Rev 2019;106:104500. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dirks MA, Persram R, Recchia HE, et al. Sibling relationships as sources of risk and resilience in the development and maintenance of internalizing and externalizing problems during childhood and adolescence. Clin Psychol Rev 2015;42:145–55. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Domhardt M, Münzer A, Fegert JM, et al. Resilience in survivors of child sexual abuse: a systematic review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 2015;16:476–93. 10.1177/1524838014557288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ben-David V, Jonson-Reid M. Resilience among adult survivors of childhood neglect: a missing piece in the resilience literature. Child Youth Serv Rev 2017;78:93–103. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lynch M, Cicchetti D. An ecological-transactional analysis of children and contexts: the longitudinal interplay among child maltreatment, community violence, and children's symptomatology. Dev Psychopathol 1998;10:235–57. 10.1017/S095457949800159X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cicchetti D, Lynch M. Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: consequences for children's development. Psychiatry 1993;56:96–118. 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Masten AS. Ordinary magic. resilience processes in development. Am Psychol 2001;56:227–38. 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cicchetti D. Annual Research Review: Resilient functioning in maltreated children--past, present, and future perspectives. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2013;54:402–22. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02608.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rutter M. Annual Research Review: Resilience--clinical implications. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2013;54:474–87. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pieloch KA, McCullough MB, Marks AK. Resilience of children with refugee statuses: a research review. Can Psychol 2016;57:330–9. 10.1037/cap0000073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tol WA, Song S, Jordans MJD. Annual Research Review: Resilience and mental health in children and adolescents living in areas of armed conflict--a systematic review of findings in low- and middle-income countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2013;54:445–60. 10.1111/jcpp.12053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Merritt S. An Aboriginal perspective on resilience. Aborig Isl Health Work J 2007;31:10. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Young C, Tong A, Nixon J, et al. Perspectives on childhood resilience among the Aboriginal community: an interview study. Aust N Z J Public Health 2017;41:405–10. 10.1111/1753-6405.12681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gartland D, Riggs E, Muyeen S, et al. What factors are associated with resilient outcomes in children exposed to social adversity? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2019;9:e024870. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gartland D. Resilience in adolescents: the development and preliminary psychometric testing of a new measure. Melbourne: Swinburne University, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:8–25. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. King L, Jolicoeur-Martineau A, Laplante DP, et al. Measuring resilience in children: a review of recent literature and recommendations for future research. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2021;34:10–21. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clauss-Ehlers CS, Factors S. Sociocultural factors, resilience, and coping: support for a culturally sensitive measure of resilience. J Appl Dev Psychol 2008;29:197–212. 10.1016/j.appdev.2008.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. DelGiudice M. Middle Childhood: An Evolutionary-Developmental Synthesis. In: Halfon N, Forrest CB, Lerner RM, et al., eds. Handbook of life course health development. Cham (CH): Springer Copyright 2018, The Author(s), 2018: 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Masten AS. Regulatory processes, risk, and resilience in adolescent development. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004;1021:310–9. 10.1196/annals.1308.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Data and Statistics on Children’s Mental Health US Dept. Health and Human ServicesMar, 2021. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html

- 28. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . Australia’s Children. Cat. No. CWS 69. In: Youth Ca. Canberra: AIHW, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rutter M. Resilience concepts and findings: implications for family therapy. J Fam Ther 1999;21:119–44. 10.1111/1467-6427.00108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas A, Cairney S, Gunthorpe W, et al. Strong souls: development and validation of a culturally appropriate tool for assessment of social and emotional well-being in Indigenous youth. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2010;44:40–8. 10.3109/00048670903393589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev 2000;71:543–62. 10.1111/1467-8624.00164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu D, Fairweather AK, Burns R. Measuring resilience: difficulties, issues and recommendations. Australasian Society for psychiatric research (ASPR) conference. Perth: Dec Fremantle, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Block K, Riggs E, Haslam N, eds. Values and vulnerabilities : the ethics of research with refugees and asylum seekers. Australian Academic Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tremblay M-C, Martin DH, Macaulay AC, et al. Can we build on social movement theories to develop and improve community-based participatory research? A framework synthesis review. Am J Community Psychol 2017;59:333–62. 10.1002/ajcp.12142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lucero J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, et al. Development of a mixed methods investigation of process and outcomes of community-based participatory research. J Mix Methods Res 2018;12:55–74. 10.1177/1558689816633309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. National Health And Medical Research Council . Increasing cultural competency for healthier living & environments. 25, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Health and Medical Research Council . Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities: guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wardliparingga Aboriginal Research Unit . South Australian Aboriginal health research Accord. South Australian Health and Medical Research Council, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gartland D, Riggs E, Giallo R, et al. Using participatory methods to engage diverse families in research about resilience in middle childhood. J Health Care Poor Underserved. In Press 2021;32:1844–71. 10.1353/hpu.2021.0170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gartland D, Conway LJ, Giallo R, et al. Intimate partner violence and child outcomes at age 10: a pregnancy cohort. Arch Dis Child 2021;106:1066–74. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hawes DJ, Dadds MR. Australian data and psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2004;38:644–51. 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hayes L. Problem behaviours in early primary school children: Australian normative data using the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2007;41:231–8. 10.1080/00048670601172715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cohen R, Schneider W, Tobin R. Psychological testing and assessment: an introduction to tests and measurement. 10th ed. McGraw-Hill Education, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, et al. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front Public Health 2018;6:149. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shevlin M. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis in clinical and health psychology. In: Miles J, Gilbert P, eds. A Handbook of research methods for clinical and health psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46. L-t H, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 1999;6:1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kline T. Psychological testing: a practical approach to design and evaluation. London: SAGE Publications, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 48. DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh 2007;39:155–64. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kaplan I, Lives RS. Rebuilding Shattered lives. Brunswick, Melbourne: Victorian Foundation for the Survivors of Torture, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Herrman H. Sustainable development goals and the mental health of resettled refugee women: a role for international organizations. Front Psychiatry 2019;10:608. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ungar M. Researching and theorizing resilience across cultures and contexts. Prev Med 2012;55:387–9. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Panter-Brick C, Eggerman M. Understanding culture, resilience, and mental health: The production of hope. In: Ungar M, ed. The social ecology of resilience: a Handbook of theory and practice. New York, NY, US: Springer Science + Business Media, 2012: 369–86. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jones JM. Exposure to chronic community violence: resilience in African American children. J Black Psychol 2007;33:125–49. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Maunder R, Monks CP. Friendships in middle childhood: links to peer and school identification, and general self-worth. Br J Dev Psychol 2019;37:211–29. 10.1111/bjdp.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pawlby SJ, Mills A, Taylor A, et al. Adolescent friendships mediating childhood adversity and adult outcome. J Adolesc 1997;20:633–44. 10.1006/jado.1997.0116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lansford JE, Criss MM, Pettit GS, et al. Friendship quality, peer group affiliation, and peer antisocial behavior as Moderators of the link between negative parenting and adolescent Externalizing behavior. J Res Adolesc 2003;13:161–84. 10.1111/1532-7795.1302002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Haddow S, Taylor EP, Schwannauer M. Coping and resilience in young people in alternative care: a systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review 2021;122:105861. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-061129supp001.pdf (126KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.