Abstract

Forensic DNA methodologies have potential applications in the investigation of human trafficking cases. DNA and relationship testing may be useful for confirmation of biological relationship claims in immigration, identification of trafficked individuals who are missing persons, and family reunification of displaced individuals after mass disasters and conflicts. As these applications rely on the collection of DNA from non-criminals and potentially vulnerable individuals, questions arise as to how to address the ethical challenges of collection, security, and privacy of collected samples and DNA profiles. We administered a survey targeted to victims’ advocates to gain preliminary understanding of perspectives regarding human trafficking definitions, DNA and sex workers, and perceived trust of authorities potentially involved in DNA collection. We asked respondents to consider the use of DNA for investigating adoption fraud, sex trafficking, and post-conflict child soldier cases. We found some key differences in perspectives on defining what qualifies as “trafficking.” When we varied terminology between “sex worker” and “sex trafficking victim” we detected differences in perception on which authorities can be trusted. Respondents were supportive of the hypothetical models proposed to collect DNA. Most were favorable of DNA specimens being controlled by an authority outside of law enforcement. Participants voiced concerns focused on privacy, misuse of DNA samples and data, unintentional harms, data security, and infrastructure. These preliminary data indicate that while there is perceived value in programs to use DNA for investigating cases of human trafficking, these programs may need to consider levels of trust in authorities as their logistics are developed and implemented.

Keywords: Decriminalization, DNA identification, ELSI, forensic DNA, human rights, human trafficking, sex trafficking, sex workers, victims

INTRODUCTION

Modern day slavery, commonly termed human trafficking, is an international problem of a horrifying scale. Although reliable statistics are difficult to obtain, human trafficking is estimated to involve more than 20 million adults and children at any given time [1]. According to UNICEF (the United Nations International Children’s Fund), as many as two million children are subjected to prostitution in the global commercial sex trade [2, 3]. Countries affected by trafficking in persons may serve as source sites, transit sites, and/or final destinations. The scope of trafficking within the United States is also challenging to ascertain as it involves individuals trafficked for multiple purposes, including involuntary servitude, slavery, debt bondage, and forced labor [3, 4]. The United States Department of State 2014 Trafficking in Persons report makes recommendations for the U.S. including the need to “increase screening to identify trafficked persons, including among at-risk youth, detained individuals, persons with disabilities, and other vulnerable populations” [1].

Solutions to limit the supply and demand for all human trafficking contexts continue to elude law enforcement. Relatively few cases of human trafficking are prosecuted, and most victims remain unidentified. Identifying victims of human trafficking remains critical to tackling illicit migration. Combating trafficking in persons requires a cooperative approach of law enforcement, social services, and victim support groups [5]. Trafficking victims have limited means to escape or seek help given how disruptive enslavement is to virtually all aspects of the victims’ lives (e.g., housing, education, jobs, healthcare, financial security). Victims require social assistance, legal assistance, and in many cases medical treatment (commonly, substance abuse). The collaborative approach must be carried out in a manner conducive to the preservation of evidence helpful for future prosecution.

Sex trafficking in particular encompasses a broad range of moral issues, civil liberties, and human rights [6]. In 2010, 62,668 arrests were made for prostitution and commercialized vice in the United States [7]. The Bureau of Justice reported 2,065 cases of sex trafficking collected by the Human Trafficking Reporting System between 2008–2010 [8]. In the Polaris Project’s first five years of operations, they documented 5,932 cases of sex trafficking [9].

Forensic application of DNA to address human trafficking is in its infancy but is likely to expand in the coming years with multiple applications and implications. Innovative applications of DNA to trafficking investigations, including databases of DNA profiles, relationship testing, and opportunistic DNA sampling, may assist law enforcement in a number of ways, including the identification of victims, the identification of suspects, and detection of fraudulent claims of biological relatedness. DNA may be applicable in human trafficking contexts for post-mortem identification of victims, identification of victims in transit or in detention, detection of unrelated individuals seeking immigration, and investigation of traffickers through opportunistic collection of suspected evidence. This approach may be particularly applicable to investigations of sex trafficking, immigration fraud, inter-country illicit adoption, organ trafficking, and family reunification of child soldiers.

Using genetic information to address these investigative challenges is riddled with issues from international cooperation to genetic privacy issues and thus far has proven to be useful only in specific, limited contexts. Nonetheless, given the scale of the human trafficking epidemic, all efforts should be considered as potentially valuable additions to the international community’s anti-trafficking arsenal, including the development and expanded implementation of DNA programs for identification and familial reunification. Strategies using DNA for investigation of human trafficking cases can not serve as a solution in and of themselves but within the context of an anti-trafficking agenda could provide identification clarity and investigative leads useful in prosecuting cases and identifying victims.

Defining Human Trafficking

Defining human trafficking is itself a challenge, with the legal definition of a given jurisdiction often differing from the social or ethical definition of trafficking. According to Article 3 “Palermo Protocol”), “trafficking in persons” includes:

“The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purposes of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs” [10].

This legal definition consists of three essential elements: (1) the actions taken (the what), (2) the means used (the how), and (3) the purpose for those actions (the why). All three elements must be present for the scenario to meet the legal definition. The Palermo Protocol explains that the victim’s consent is “irrelevant where any of the means set forth in subparagraph (a) have been used” [10]. Similarly, when the exploitative actions involve a child (i.e., any person under 18 years of age), the means used are irrelevant [10]. The Palermo Protocol does not define exploitation or provide an exhaustive list; rather, it provides a baseline of examples that would be included. This aspect of the Palermo Protocol allows the States discretion to determine, as a matter of national law, whether specific scenarios are considered exploitation. For example, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime takes an official neutral position on whether prostitution (i.e., consensual sex work) is trafficking in persons [11]. Application of the Palermo Protocol’s “trafficking in persons” definition to the scenarios surveyed here reveals the challenges of research conducted in this area. Determinations are fact specific and, accordingly, depend on nuances and must be made on a case-by-case basis. For example, scenarios involving the transfer of children for monetary compensation do not always fit the Palermo Protocol’s definition. Consider the scenario in which a child is given up by biological parents and taken in by a new couple that provides monetary compensation to the biological parents. Under such a scenario, the action element is satisfied (there has been a transfer), the means element is disregarded as irrelevant (because a child is involved), and the determination rests upon whether the purpose of the transfer is exploitative. Such a determination requires consideration of domestic laws. As of 2013, 31 U.S. states have statutes that prohibit the offering or acceptance of money for relinquishing parental rights, [12] thereby limiting any monetary exchange to those expenses permitted by statute. Payments within the statutory allowances would likely not to be considered coercive or exploitative; however, payments in excess of the statutory allowance would likely to be considered coercive and exploitative per se. Thus, the scenario of providing monetary compensation for a child adoption is sometimes—but not always—trafficking in persons.

DNA Applications in Detecting Human Trafficking

Forensic DNA approaches for human identification could vitally aid investigation of human trafficking cases. Some have proposed including DNA typing and relationship testing as part of a comprehensive approach to detect child trafficking, [13] adoption fraud, [14–16] and human trafficking [17–22]. For example, DNA collection of displaced children was proposed after the 2011 Haiti earthquake in order to track placement and reunify found family members [20]. After the April 2014 abduction of Nigerian schoolgirls by Boko Haram, DNA collection of family members was proposed to facilitate identification and family reunification as suspected victims emerge (whether soon or after many years) [20, 23–25]. The U.S. and at least 19 other countries have made some efforts to incorporate DNA relationship testing into border security measures to confirm immigrants’ relatedness to individuals who are already settled in the receiving country [26, 27]. This effort is designed in part to aid in the identification of trafficked individuals. A number of countries have applied DNA technologies specifically to identify and rescue trafficking victims. China initiated a nationwide DNA database program in 2009, which as of early 2013 had assisted in the reunification of more than 2,300 homeless or abducted children to their families [28, 29]. The United Arab Emirates have used DNA testing to identify children who may have been trafficked as camel jockeys [30]. Notably, DNA-PROKIDS (www.dna-prokids.org) has partnered with numerous governments and law enforcement agencies to collaborate in providing DNA testing for cases of human trafficking [31, 32].

The use of DNA to investigate cases related to sex trafficking have broad applications from identifying homicide victims [33] to connecting evidence of repeat offenders (e.g., sex customers), [21] and potentially to identifying trafficked missing persons. One locale in the U.S., Dallas, TX, is using DNA to investigate sex trafficking-related crimes with its Dallas Prostitute Diversion Initiative (PDI) [34] and Positive Recovery Intensive Divert Experience (PRIDE) Court. Through this program, detained sex workers are offered participation in a high-risk DNA database (HRDNA) to serve as a reference database for post-mortem identification. A municipality in Canada [35] is also using this approach, and other jurisdictions may be poised to follow [36, 37].

Other Human Rights DNA Applications

Trade in human organs and illicit adoptions, while not technically or uniformly considered human trafficking under the Palermo Protocol, also involve violent abduction or non-violent coercion. In the U.S., a child from outside the U.S. may legally be adopted if he or she has no parents, most often when both parents are determined to have died, disappeared, been separated from, or have abandoned the child [38]. In many cases, children may be illicitly or wrongfully placed for international adoption. A child may be abducted from guardian care or parents may be forced or compensated to relinquish a child. DNA may be helpful in some cases to verify parentage of a relinquishing parent of a child placed for adoption. After an emergency, mass or natural disaster, or war, a child may be displaced from their family and later adopted out of their home country [5]. In these cases, a DNA profile database may be useful to document the identities of displaced individuals.

Often, wrongful adoption and human trafficking involves laundering and fraud through the falsification of travel or identification documents to make it possible to transport victims across international borders [39]. In many cases, trafficking victims’ travel documents are confiscated by the traffickers to hinder travel [1]. With modern increases in international travel and migration, many countries now recognize the need to accurately and expediently identify individuals attempting to cross international borders. As part of these efforts, many governments, law enforcement, and private organizations have begun incorporating biometric identification technologies, including DNA collection, to manage international travel and track immigrants [27, 40, 41].

Ethical, Legal, & Social Implications

The social ramifications of collecting DNA from vulnerable populations (e.g., children, vagrant youth, sex workers, victims) are considerable and questions remain unanswered on how to protect individuals from misuse of voluntarily provided DNA [20]. Cross-jurisdictional collaborations present the nontrivial challenge of sharing sensitive identification information, DNA profiles, and genetic information in a secure manner and with cultural sensitivities distinct to each population. Concerns have been voiced about the security of DNA profile systems, the possible disclosure of personal information, and the risk for misuse and/or malfunction [42]. Individuals sampled for such a database may be at a risk for coercion to submit samples into the database. For instance, they could be under the influence of alcohol or other mind-altering substances, could have uncertain legal status, or could be desperate for support services that they fear would otherwise not be accessible without providing samples. Additionally, sampled individuals may not fully understand the anticipated benefits, technical limitations, and potential risks associated with DNA collection and profiling [20]. Cultural and political differences around the world mean that different communities may hold varying attitudes toward DNA collection and profiling [43]. Some populations may differ in concerns regarding DNA submission and fear of retribution for reporting suspicions or evidence of ongoing crimes [44]. Moreover, mistrust of law enforcement officials among sex trafficking victims is high, seeded from a history of brothel raids and sting operations targeted at arresting sex workers. Often trafficking victims are traumatized or are fearful of retaliation by their traffickers and may be reluctant to cooperate with law enforcement investigations [45, 46]. The advocates who work with these victims may have similar distrust of authorities and question the official use of DNA for assisting victims. Yet it is the role of the advocate – e.g., a social worker, police officer, lawyer, human rights volunteer, or medical professional – to advise a victim of options for rescue from a trafficking situation. Earning the buy-in of this population is essential for long term success of any DNA strategy involving victims’ genetic information.

If we are to construct a DNA-based approach to identifying human trafficking victims, we must first develop a basic sense of the perspectives of two key stakeholders: 1) the victims to be sampled and catalogued; and 2) the victims’ advocates who might approach a victim for DNA collection. To ascertain the first stakeholder set, our study team conducted focus groups with potential victims (not reported here, manuscript under preparation). Reported here are our pilot findings on the second stakeholder set. To understand the perspectives of victims’ advocates who work with trafficked victims, we launched a survey on DNA applications to identify victims, including use to combat sex trafficking, adoption fraud, and child trafficking for military actions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Survey Development and Data Collection

Two workshops were conducted, each with 40–50 participants at Duke University, to inform survey design and questions. The workshops, attended by academics and professionals with an interest in human trafficking, centered on discussions and debate surrounding the use of DNA in a variety of human trafficking contexts. The workshops resulted in a series of key questions and three focus areas of possible DNA applications: sex trafficking, adoption fraud, and child soldiers. We used these workshops to ascertain salient issues from multiple disciplines to develop answer choices that were appropriate to the target population. We consulted or included in the workshops social workers, ethicists, law enforcement, lawyers, and laboratory directors. We also invited to the workshops Duke faculty, staff and student participants from The Kenan Institute for Ethics, Duke Human Rights Center at the Franklin Humanities Institute, and Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy. Development of survey questions and design was informed in consultation with internal and external content experts, including relationship testing laboratories and forensic experts. The survey questions (available as supplemental data) contained four main sections: (1) demographics; (2) definitions of human trafficking; (3) attitudes towards law enforcement and uses of DNA; and (4) consideration of mock scenario applications using DNA. In total, the survey consisted of 60 questions formatted as Likert-scale, multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, and open response questions. Respondents working directly with victims’ advocacy organizations were presented with certain additional questions that were not relevant or provided to general respondents. An existing stigma scale was adapted to assess attitudes towards sex workers [47, 48]. One question randomly presented the alternating terms “sex worker” and “sex trafficking victim.” The survey was designed and distributed using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, LLC, Provo, UT). All study materials and protocols were approved by the Duke University Health Systems Institutional Review Board (DUHS Pro00048591).

Sample and Recruitment

We sought preliminary data on challenges with DNA applications in human rights context by approaching potential participants working for human trafficking and human rights organizations. We used a snowball sampling strategy to recruit study participants from victims’ advocacy organizations and human trafficking listservs, targeting victims’ advocates as a primary stakeholder group. Organizations were identified using Internet search terms for “human rights,” “human trafficking,” and “sex trafficking,” We sent introductory e-mails to 225 organization contacts inviting them to participate in an anonymous, web-based survey and encouraging them to forward the invitation to other colleagues who may not have received it. Fourteen invitations were also posted to organization usernames on Twitter (twitter.com, San Francisco, CA) and included hashtag prompts #humanrights, #humantrafficking, #slavery, and #stophumantrafficking. Participants were offered an incentive of entry into a drawing for a $50 gift card.

Descriptive Analysis

Responses to most questions were recorded on 5-point Likert scales and were summarized using frequency distributions. Sample sizes did not allow for statistical analysis, so data are described to demonstrate trends. Differences in frequency of responses between demographic populations [e.g., male vs. female, student vs. non-student, human trafficking (HT) worker vs. non-human trafficking (non-HT) worker, white vs. non-white] were compared. For Likert scales, the response categories were ordered and coded as follows: strongly agree/yes responses as 0, agree as 1, neutral as 2, disagree as 3, and strongly disagree/no as 4. Microsoft Excel v.14.4.2 was used for all analyses. To describe the trends in the Likert scales, the codes were summed and divided by the sample size (Σ/N). Stigmatization variables were quantified via an additive scale based on relative agreements with stigmatization scale statements, with increasing stigmatization on a scale from 0–4. Sample sizes varied by question since participants were allowed to skip any question they did not wish to answer, only those working with victims were provided some questions, and participants were required to respond only to one of the three scenarios. Qualitative data were collected on eight questions, but sample sizes prohibit qualitative analysis. Samples of the qualitative data are presented in Box 2.

Box 2.

Selected quotes from open-ended mock scenario questions.

|

What concerns do you have about the use of DNA for law enforcement, immigration, and/or human trafficking?

| |

| “Corruption, use for punitive purposes. Perhaps a law could be created that states the particular DNA collected in the program cannot be used against donors in a court of law.” – 34 year old female, social worker | |

| “Many victims of trafficking are undocumented, and while there are visas and laws in place to help them stay in this country, that does not always happen easily, so it is possible additional information/identification could be used against them in deportation. Additionally, the time/effort/money going into a program like this does not seem like a wise use of limited resources.” – 30 year old female, social worker | |

| “Our DNA is a fundamental part of who we are and it seems like we are being asked to give up a tiny part of ourselves in some way nearly everyday. There is a tremendous amount of good that can come from these sciences but there is also the potential for terrible repercussions. When a piece of information as valuable as a persons’ fundamental identity is on the line can we really be too careful with who should hold that information, who should be able to use it and what they can use it for? The intended purpose may be altruistic but ultimately, 10–15 years later, who knows how or why that same information may be applied.” – male, unknown age, volunteer | |

|

What benefits are there to using DNA for law enforcement, immigration, and/or human trafficking? | |

| “I see value in using DNA to identify perpetrators of crimes, linking them to a murder scene for example. I also think there is potential benefit in using DNA for identification of children/missing children/adoption, but it requires the utmost confidentiality and care of information, which is difficult to trust our government, must less other more corrupt governments to provide the necessary precautions. Most NGOs have better intentions but lack the infrastructure and technology to seriously guard sensitive information. I also see the value in using DNA for human trafficking, but I do worry about human rights violations that could have negative and unintentional effects for the victims.” – 30 year old female, social worker | |

| “In the case of missing persons: Identification of human remains and repatriation to victim families, identification of living missing persons and reunification with biological families, addressing/persecuting missing person related crimes (such as human trafficking, etc.).” – 46 year old male, scientist | |

| “It helps get around the tactics traffickers use to hide their victims.” – 24 year old female, communications | |

|

What concerns would you have about participation? | |

| International Adoptions | “My concern would be the DNA samples were not kept confidential or could in some way be used against the Guatemalan families. Also concern regarding the accuracy with which a child can be matched to a family of origin, making sure that children weren’t sent back to the wrong families.” – 30 year old female, social worker |

| “1. Family and child informed consent. 2. Right to privacy guarantees. 3. Judicial consequences in case there is an identification (i.e., what will happen [next]?)” – 46 year old male, scientist | |

|

| |

| Child Soldiers | “Procedures for protection of samples and information. Special consideration for the needs of the child, including considerations of the negative consequences of reunification. Transparent and fair processes that respect the families’ privacy. Ensuring the government processes have appropriate checks and balances and transparency so attempts to cover up political involvement in crimes against humanity, etc. are not covered up.”– 42 year old female |

| “That the children’s DNA would include medical information about [diseases] that would stigmatize them in their home community.” – 24 year old female, communications | |

|

| |

| Sex Trafficking | “Exploitation of the sex workers’ rights - being accused of crimes not committed.”– 27 year old female, sociologist |

| “Prejudicial administration and implementation. Privacy issues.” – 31 year old female, lawyer | |

|

What would motivate you to encourage or discourage participation? | |

| International Adoptions | “Knowing more about how samples and data were stored and used, what kind of DNA analysis was used (whole genome, selected markers, etc.), and what kind of counseling children and families were given before participating.”– 29 year old male, lawyer |

| “I think orphanages can be pretty grim places to grow up, and if a child has a family to go back to, and this could help them get home, iťs worth the risk.”– 24 year old female, communications | |

|

| |

| Child Soldiers | “I would encourage participation when data security is present, when corrupting forces are minimized, when child soldiers and families both desire reunification, when child soldiers can be protected during the identification and reunification process, and when family members can be protected from potential reprisal or punishment for providing DNA. I would discourage unstable testing programs that could not provide participants with informed choices, data security, and personal/communal safety.”– 32 year old female, volunteer |

| “That families hold the information and only provide to government or police agencies when seeking help.”– 63 year old female, sociologist | |

|

| |

| Sex Trafficking | “I would encourage participation for those wanting peace of mind, concerned about potential danger involved with sex work, and those generally supportive of database-based law enforcement protocols. I would discourage participation if DNA samples cannot be kept securely, or if collection and use protocols are not clearly developed and clearly enforced.” – 32 year old female, volunteer |

| “Knowing more about limits on university’s ability to use samples, local law enforcement’s political history, and what counseling is provided to sex-workers before participating.”– 29 year old male, lawyer | |

RESULTS

A total of 39 online surveys were started, 37 completed (94.9%); due to our snowball sampling approach, the response rate is unknown (Table 1). Results from the two incomplete surveys were included in the response analyses. Of the 39 respondents, 23 (59%) had experience with organizations working with victims. Demographic characteristics of the respondents are shown in Table 1. The sample contained a higher percentage of women than men. Respondents indicated a mixed familiarity with law enforcement use of DNA and DNA databases. Due to the convenient, snowball sampling strategy used and the low sample size, this survey sample might not be representative of all victims’ advocate organizations and results might not be generalizable.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents.

| Invitations | N = 239 | %age |

|---|---|---|

| Responses | N = 39 | |

|

| ||

| Complete | 37 | 94.9% |

|

| ||

| Partial | 2 | |

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

|

| ||

| Female | 31 | 79.5% |

|

| ||

| Male | 8 | 20.5% |

|

| ||

| Race / Ethnicity | ||

|

| ||

| White, European, or European American | 30 | 76.9% |

|

| ||

| Other (including Hispanic white) | 7 | 17.9% |

|

| ||

| No response | 2 | |

|

| ||

| Students | 7 | 17.9% |

|

| ||

| Experience working with HT victims | ||

|

| ||

| Career | 17 | 43.6% |

|

| ||

| Volunteer | 6 | 15.4% |

|

| ||

| Tenure in victims’ advocacy | ||

|

| ||

| 1–2 years | 6 | 15.4% |

|

| ||

| 3–5 years | 8 | 20.5% |

|

| ||

| 6–10 years | 4 | 10.3% |

|

| ||

| More than 10 years | 5 | 12.8% |

|

| ||

| Familiarity with law enforcement use of DNA | Very | 29.0% |

| Somewhat | 63.1% | |

| Not at all | 7.9% | |

|

| ||

| Familiarity with U.S. law enforcement DNA database CODIS | Very | 23.7% |

| Somewhat | 47.4% | |

| Not at all | 28.9% | |

Defining Human Trafficking

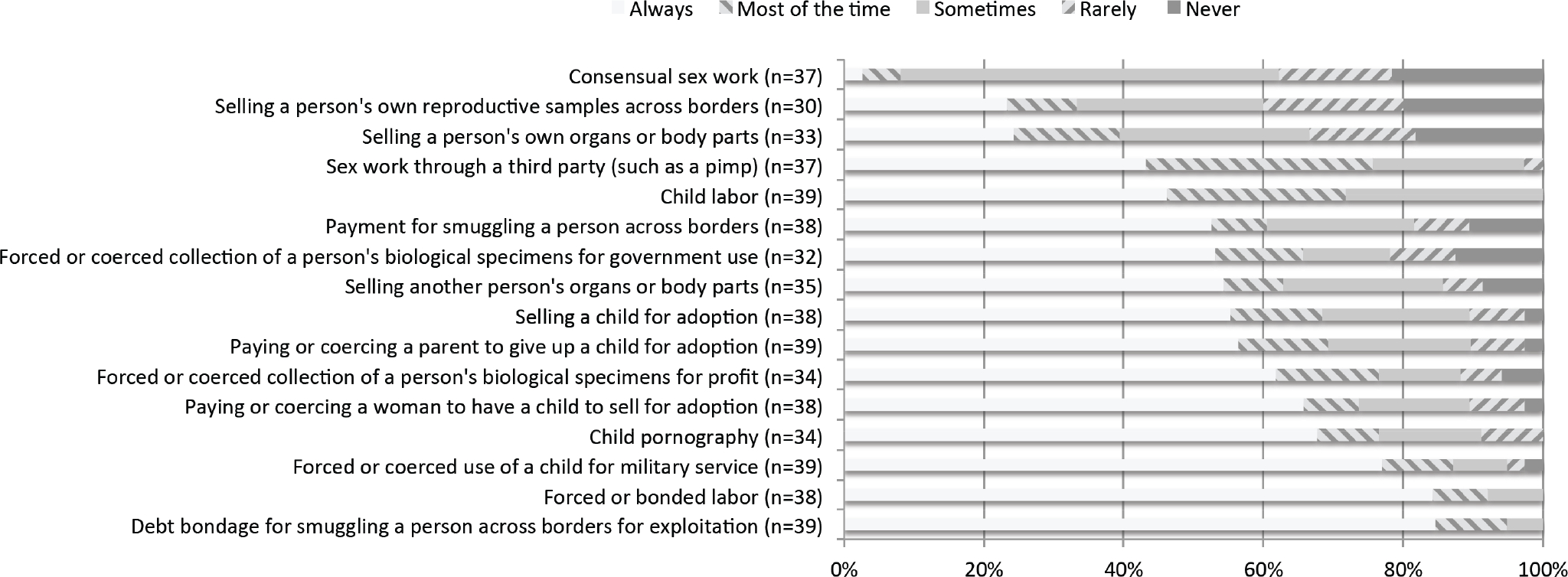

Respondents were presented with multiple scenarios and asked whether they considered the scenarios to be examples of “human trafficking” Fig (1). Few respondents (8.1%) indicated that they considered consensual sex work to be human trafficking (most or all of the time) whereas the majority (89.5%) considered child prostitution human trafficking. All but three of the scenarios were considered human trafficking most or all of the time (consensual sex work, selling a person’s reproductive samples, and selling a person’s own organs or body parts). Many of the scenarios that do not fit the Palermo Protocol definition were thought to be cases of human trafficking. All of the scenarios involving children were considered by the majority to be human trafficking. Importantly for DNA applications, the two scenarios involving biological specimens for profit or government use (taken by force or coercion) were considered human trafficking by the majority of respondents.

Fig. (1).

Opinions about scenarios that represent possible interpretations of human trafficking. Respondents were presented with multiple contexts and used a Likert scale to rate whether they considered each to be an example of human trafficking.

Attitudes about international adoptions were assessed via Likert scales finding general neutrality or agreement among respondents (n=39) that adoption is good for families (94.9%), the adopted child (89.7%), and the originating country (87.2%).

Respondents were asked about the perceived discrimination against sex workers using five stigmatization scale statements (Table 2) [48]. No difference was observed between responses filtered by demographic variables, except for a slight difference between the sexes of the respondents where responses from females indicated slightly more perceived discrimination of sex workers (3.0) than males (2.6).

Table 2.

Perceived stigmatization of sex workers.

| Stigma Question [“Agree or disagree with the following statements”] | Score (Σ/N) N=38 |

Females (N=30) |

Males (N=8) |

Students (N=7) |

Non-Students (N=31) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most people would willingly accept a sex worker as a close friend | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 |

| Most people believe that a sex worker is just as trustworthy as the average person | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 3.0 |

| Most people would date a person who has been a sex worker | 3.0 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| Most employers will hire a sex worker if he or she is qualified for the job | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| Most people in my community would treat a sex worker just as they would treat anyone | 3.1 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

| OVERALL | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.9 |

Data are scores calculated as (Σ/N), where Σ is the sum of 5-point Likert scale responses, Strongly Agree (SA) to Strongly Disagree (SD), where a weight of 0 was used for each SA response, 1 for each Agree, 2 for each Neither, 3 for each Disagree, and 4 for each SD; N is the sample size of respondents who answered that question.

Higher scores indicate an increase in stigmatization. Darker shading also indicates a higher perception of stigmatization.

Attitudes Towards Law Enforcement and Uses of DNA

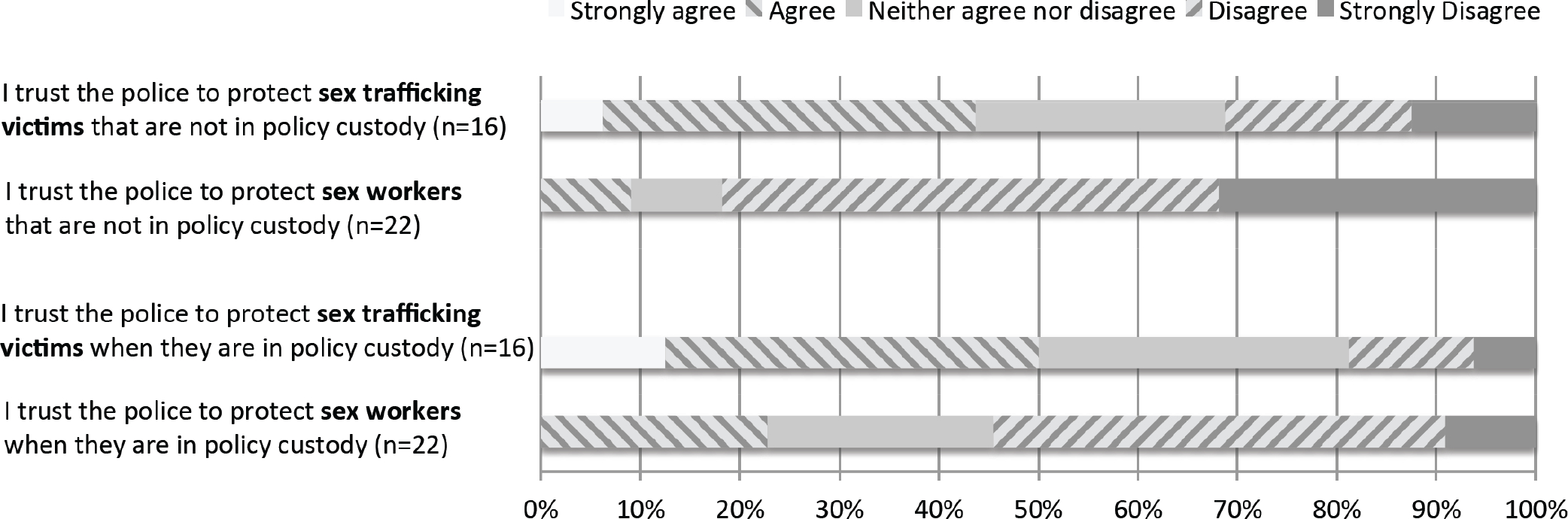

Respondents also indicated their trust of authorities in assisting victims, identified in the survey either as “sex workers” or “sex trafficking victims,” where higher scores indicated increased trust (Table 3). Respondents who were asked about their trust in police to protect a “sex worker” that is not in police custody indicated less trust of authorities (3.0) compared to those who were asked about their trust in police to protect a “sex trafficking victim” that is not in police custody (1.9) Fig. (2). No differences were observed among demographic variables. A similar trend was observed when participants were asked about their trust in the police to protect those in police custody (sex worker = 2.4, sex trafficking victim = 1.6). Respondents indicated slightly more trust in social workers, health care providers, and lawyers than in police for protecting both sex workers and sex trafficking victims (Table 3).

Table 3.

Trust in authorities to protect victims.

| Trust Question [“Agree or disagree with the following statements”] | Score (Σ/N) (N=38) | Subject “sex workers” (N=22) | Subject “sex trafficking victims” (N=16) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I trust the police to protect [SUBJECT] when they are in custody | 2.1 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| I trust the police to protect [SUBJECT] that are not in police custody | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.9 |

| I trust social workers to assist [SUBJECT] | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| I trust a health care provider to assist [SUBJECT] | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| I trust a lawyer to assist [SUBJECT] | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.2 |

Σ of 5-point Likert scale responses, Strongly Agree (SA) to Strongly Disagree (SD), weighted 0 for each SA response, 1 for each Agree, 2 for each Neither, 3 for each Disagree, and 4 for each SD.

Higher scores indicate an increase in stigmatization. Darker shading also indicates a higher perception of stigmatization.

Fig. (2).

Variations in respondents’ trust in law enforcement when using the term “sex worker” versus “sex trafficking victim.”

When asked about DNA being used as a law enforcement tool, respondents were either neutral or supportive of the application for solving crimes (100%) and identifying victims (97.4%). Respondents were also neutral or favorable towards the use of CODIS (Combined DNA Index System, the U.S.-based national DNA database) for solving crimes (92.1%).

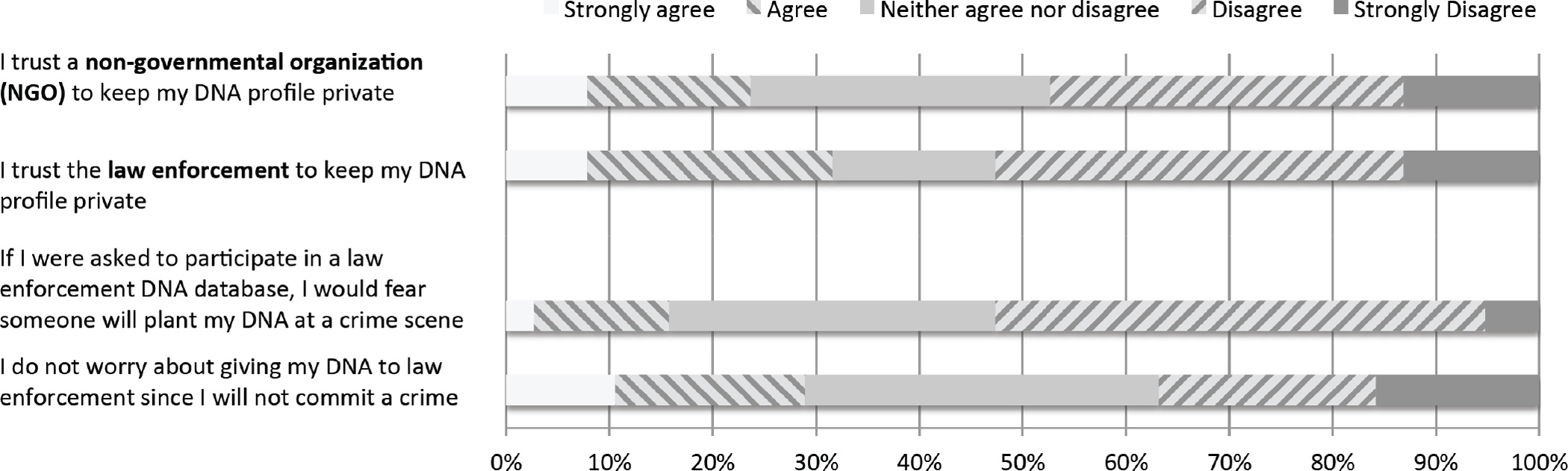

With respect to the privacy of genetic information, on a scale of 0–4 with 0 being private, participants felt that DNA is private information (1.1), and they strongly favored privacy protections for DNA samples (0.7) and for DNA identity profiles (0.8). However, when asked whether they trusted law enforcement and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to keep DNA profiles private, roughly half of respondents indicated that they did not trust law enforcement (52.6%) nor NGOs (47.4%) to protect DNA profiles Fig. (3). Some respondents indicated that they feared that their provided DNA could be planted at a crime scene (15.8%). However, respondents were split on whether they worried about providing DNA to law enforcement on the assumption that they would not commit a crime, with 28.9% indicating that they trusted law enforcement and 36.8% distrusted law enforcement.

Fig. (3).

Respondents’ (n=38) trust towards the use and protection of DNA samples provided to law enforcement or non-governmental organizations.

Mock Scenarios of DNA Applications

Respondents could choose to consider one, two, or all three mock scenarios described in the survey (Box 1). These scenarios presented the use of DNA (a) in international adoptions contexts (n=21); (b) in child soldier contexts (n=19); and (c) for identifying sex trafficking victims (n=31).

Box 1.

Mock scenarios of DNA applications.

| A. | In Guatemala, children have been sold for purposes of international adoption, prompting closure of several adoption programs and resulting in an abundance of orphans. DNA samples from children being considered for adoption and residing in orphanages may be collected for comparison to samples collected from families in villages with reported missing children. The program would be intended to assist with identification of stolen children before they are placed for international adoption. |

| B. | In Sierra Leone, victims’ advocates are recovering groups of trafficked child soldiers and attempting to identify the children and their families for reunification. DNA samples from children may be collected for comparison to samples collected from families in villages with missing children. The program would be intended to assist with rapid and reliable identification of human trafficking victims. |

| C. | In Texas, the High Risk Potential Victims DNA Database is a voluntary DNA collection program for sex workers completing a prostitute diversion program run by the local police department in partnership with social services. DNA samples from consenting individuals are collected and stored in a repository at a local university. The program is intended to assist with post-mortem identification of sex workers likely to be victims of serial crime in Texas. Samples remain unprocessed until law enforcement suspects that a violent crime, homicide, or missing persons case may be connected to an individual sampled. A database of DNA profiles from sex workers also could be useful for identifying missing persons and victims of human trafficking if a second sample were collected for comparison to the nation-wide missing persons database. |

International Adoptions

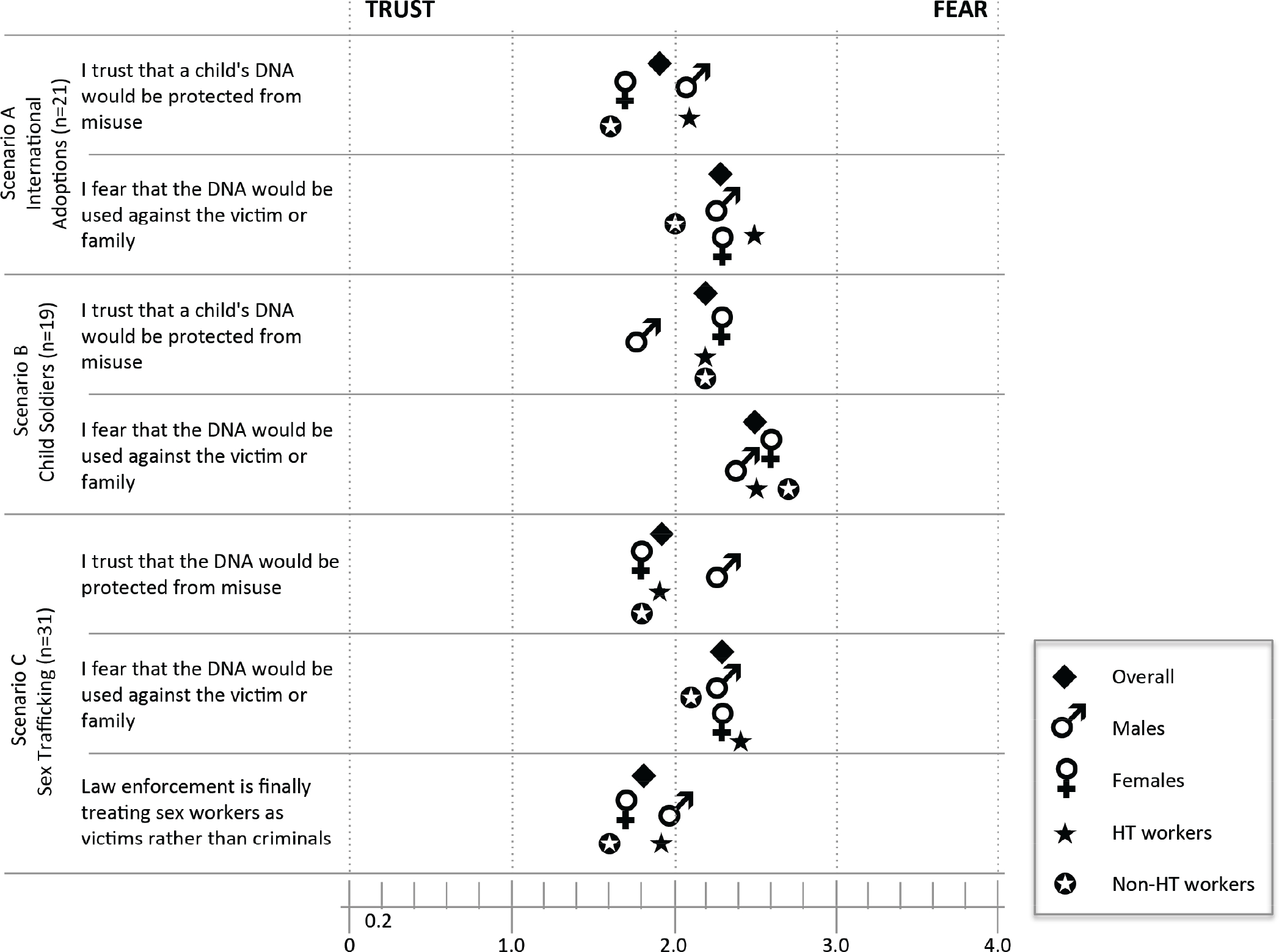

All 21 respondents (100%) would recommend participation in this mock DNA collection program (Table 4), which respondents overwhelmingly indicated (n=21, 95%) would benefit either the victims or their families (Table 5). Respondents showed considerable distrust of the law enforcement in Guatemala to hold DNA specimens; however, respondents were split over whether other entities could be trusted to hold or use DNA specimens (Table 6). Males indicated less trust in the protection of DNA from misuse than did females. Additionally, compared to respondents who have not worked with human trafficking victims, respondents who do work with human trafficking victims indicated less trust and greater fear that DNA may be used against the victim or family Fig. (4).

Table 4.

Recommended participation in mock scenario DNA programs.

| Would you recommend participation in the DNA collection program? (“Yes”) | Overall | Males/Females | HT workers/non-HT |

|---|---|---|---|

| International adoptions (n=21) | 100% | ||

| (n=5 / n=14) | (n=13 / n=6) | ||

| Child soldiers (n=19) | 94.7% | 100% / 92.9% | 100% / 83.3% |

| Sex trafficking (n=31) | (n=6 / n=25) | (n=19 / n=12) | |

| Sample storage for post-mortem identification | 87.1% | 67% / 92% | 84.2% / 91.7% |

| DNA profiling for post-mortem identification | 76.7% | 60% / 80% | 66.7% / 91.7% |

| DNA profiling for comparison to missing persons database | 86.7% | 60% / 92% | 83.3% / 91.7% |

Table 5.

The perceived primary beneficiary of mock scenario DNA programs.

| Who do you see as the primary intended beneficiary of this program? | International adoptions (n=21) | Child soldiers (n=19) | Sex trafficking (n=31) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Law enforcement or government | 4.8% | 10.5% | 50% |

| Families of victims | 57.1% | 47.4% | 26.7% |

| Victims | 38.1% | 42.1% | 23.3% |

| Local community | - | - | n/a |

Darker shading indicates a higher percentage of responses.

Table 6.

Trust in possible administrators of mock scenario DNA programs to protect victims’ DNA samples.

| Trust Question [“If such a program were to be offered, who would you trust to HOLD the DNA specimens and USE the DNA profiles (only relaying identity)?”] | Who would you trust to HOLD the DNA specimens? Score (Σ*/N) | Who would you trust to USE the DNA specimens? Score (Σ*/N) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| International Adoptions (N=21) | ||

| Law enforcement in Guatemala | 3.2 | 2.1 |

| Government organization in Guatemala | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| Government organization outside of Guatemala | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| NGO | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| Academic center | 2.4 | 1.4 |

|

Child Soldiers (N=18) | ||

| Law enforcement in Sierra Leone | 3.3 | 2.0 |

| Government organization in Sierra Leone | 2.7 | 1.9 |

| Government organization outside of Sierra Leone | 2.8 | 2.1 |

| NGO | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| Academic center | 1.9 | 1.2 |

|

Sex Trafficking (N=23) | ||

| Texas law enforcement | 2.2 | 1.8 |

| US-based governmental organization | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| NGO | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| Academic center | 0.9 | 1.1 |

Σ of 3-point scale responses, weighted 0 for each Yes response, 2 for each Maybe, and 4 for each No

Higher scores and darker shading indicate a decrease in trust.

Fig. (4).

Differences in trust and fear among respondents regarding the use of DNA in mock scenarios (Box 1). The scale presents increasing trust on the left and decreasing trust (increasing fear) on the right. 5-point Likert scale questions [Strongly Agree (SA) to Strongly Disagree (SD)] were calculated as Σ/Ν (“Trust” questions weighted 0 for each SA response, 1 for each Agree, 2 for each Neither, 3 for each Disagree, and 4 for each SD; “Fear” questions weighted 0 for each SD response, 1 for each Disagree, 2 for each Neither, 3 for each Agree, and 4 for each SA).

Child Soldiers

Most of the respondents would recommend participation in this mock DNA collection program (Table 4), which was seen overwhelmingly (n=17, 89.5%) to benefit either the victims or their families (Table 5). Respondents showed considerable distrust of the law enforcement in Sierra Leone to hold DNA specimens; however, respondents were split over whether other entities may be trusted to hold or use DNA specimens (Table 6). Unlike the adoption scenario, females indicated slightly less trust than males in the protection of DNA from misuse. There were negligible differences among responses according to other demographics Fig. (4).

Sex Trafficking

A majority of respondents (n=27, 87.1%) indicated they would recommend participation in DNA collection for post-mortem identification, 76.7% (n=23) for DNA profiling for post-mortem identification, and 86.7% (n=26) for DNA profiling for comparison to missing persons database (Table 4). Half of the respondents see this program as benefiting victims or their families, while the other half see the primary beneficiary as law enforcement (Table 5). Respondents were split over which entities could be trusted to hold or use DNA specimens, but showed slightly more trust in academic centers (Table 6). Males indicated slightly less trust than females in the protection of DNA from misuse, and respondents who work with human trafficking victims indicated slightly less trust and greater fear that DNA may be used against the victim or family Fig. (4). Respondents were split in their opinions on whether the mock scenario indicated that law enforcement were treating sex workers as victims rather than criminals Fig. (4).

Each scenario was accompanied by four open-ended questions asking about concerns and benefits regarding its proposed DNA program. Respondent concerns centered on privacy, misuse of DNA information, unintentional harms, data security, and infrastructure. Selected quotes for all scenarios can be found in Box 2.

DISCUSSION

These pilot data provide initial insight into how human trafficking victims’ advocates may perceive the collection and use of genetic information for anti-trafficking purposes. The small sample size and broad topics covered represent trends and considerations for use when planning DNA collection programs. Formal statistical analysis of these data would be inappropriate and potentially misleading. Nevertheless, these preliminary data are useful for highlighting areas in need of additional research. Certain aspects of our work raised important questions that require further research to investigate.

In the mock scenarios, the primary beneficiary of the sex trafficking program was perceived to be law enforcement/government, whereas the primary beneficiary of the other two programs was perceived to be the victims/families. This difference might tell us something about the way each scenario was framed and suggests the challenges that such programs face both in design stages and in efforts to obtain public support or buy-in. Regardless, the clear difference highlights the importance of developing DNA programs thoughtfully and context-dependently, with a mindful eye on the victims’ perspectives and personal risks (manuscript in progress).

The ethical and social challenges associated with DNA collection are not unique to these victims. DNA is collected by law enforcement routinely from sexual assault victims, relatives of missing persons, and sex workers under criminal investigation. One challenge unique to human trafficking victims lies in the necessity of cross-jurisdictional DNA databases that will most optimally address human trafficking investigations. For instance, one can envision border checks to confirm relationship claims or missing persons database searches of DNA from detained vagrant youth or sex workers to identify trafficked individuals. Whereas the general public seems to accept the use of DNA for investigating crimes, the collection and storage of DNA and DNA profiles from non-criminal individuals by law enforcement may be unpopular. Existing programs using DNA (e.g., DNA-PROKIDS, HRDNA) are partnerships between law enforcement and academic or social services to assail concerns of DNA misuse by authorities. However, further delineation between authorities may be necessary to ensure that participation has maximum benefit for victims.

Another major challenge is the mistrust by sex workers and undocumented immigrants of authorities such as law enforcement. While a law enforcement program may be developed with the intention to protect victims of trafficking, the victims themselves may not trust the authorities to use their genetic information solely for this purpose. Prostitution continues to be a criminal offense in most jurisdictions, so sex workers (whether voluntary actors or human trafficking victims) are unable or reluctant to seek assistance from victims’ support, law enforcement, or the judicial system for fear of prosecution for acts of prostitution, fear of retaliation from their traffickers (such as pimps and madams), and distrust of authorities.

Policies and protocols for the application of DNA technologies as anti-trafficking measures must be data-driven to avoid the innumerable pitfalls of this complex problem and appropriately situate the narrow DNA component into the broader anti-trafficking approach. Understanding the perceptions and assumptions of stakeholders is essential to design, develop, and implement successful programs. Insights from law enforcement, practitioners, advocates, and--perhaps most importantly--former victims are vital to avoid “ivory tower” theorizing by the academic community and to set programs up for success (namely so that the programs are equitable, effective, and efficient). While a set of overarching principles might be valuable guidelines, in practice programs require adaptability to continually changing local conditions, circumstances, political winds, and legalities. It is useful to keep the inherent dignity and equality of all human beings at the forefront and acknowledge that local conditions might require different approaches to promote and ensure that equality. The design and implementation of DNA programs as anti-trafficking measures must adequately take into account the diversity of the victim population the specific programs are targeting in order to allocate resources responsibly and maximize the program’s impacts and return on investment. Dank et al. (2014) reported complex racial and ethnic relations among victims and trafficking perpetrators in different U.S. cities and venues; [6] in other words, the racial and ethnic composition of the trafficking perpetrators and trafficked victims vary from one city to another and between brothels, strip clubs, massage parlors, truck stops, and street work. Accordingly, DNA collection schemes must be narrowly tailored to the local contexts to avoid disparate impacts and to mitigate and overcome nuanced ethical, legal, and psychosocial challenges faced by members of the victim populations the programs are intended to benefit. If implemented poorly, DNA programs could exacerbate levels of distrust held by trafficking victims toward law enforcement, could exacerbate racial disparities within the sex industry, and could exhaust limited resources and prevent their application to meet other needs of trafficking victims. Data to inform policy in this area are scant, which is one reason why the preliminary data we are sharing here are valuable despite its limitations.

Study Limitations

The main limitation of this pilot study was the number of survey responses. A few reasons may explain the low response rate: the snowball sampling may not have reached sufficient individuals; invitations were sent by email with a single follow-up email to potential participants; and the sensitive nature of the subject matter may have dissuaded from people from participating. The survey recruited few males and non-white respondents. The participants were self-selected, so there may be responder bias towards people who have strong pre-existing views on human trafficking and/or on the uses of DNA. For these reasons, care must be taken in interpreting the findings presented here as they may not be generalizable to a wider population. Nevertheless, the diversity of our participants in terms of age, career focus, education level, and previous experiences with human trafficking provides a variety of viewpoints regarding the use of DNA for human trafficking investigations.

CURRENT AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENT

These data highlight the need for further research into the distinct challenges of collecting DNA from victims and family members for investigation of human trafficking. It will be important to look at the perspectives of victims (or potential victims) such as those individuals sampled for the HRDNA or DNA-PROKIDS programs. The root of the mistrust of authorities demonstrated by our data is unknown, as are the reasons for concern over collection of respondents’ own DNA for law enforcement purposes. Investigating the uptake and outcomes of existing programs will be important, as well as mapping the policy structures developed, to prevent misuse of genetic information in these and future programs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project and manuscript developed after insightful conversations at the DNA, Human Rights, & Human Trafficking Workshops held at Duke University on March 20, 2013 and September 13, 2013, which were made possible by funding from the Josiah Charles Trent Memorial Foundation. The workshops were co-sponsored by the Institute for Genome Sciences and Policy, The Kenan Institute for Ethics, and the Duke Center for Human Rights at the Franklin Humanities Institute. MAM is supported by NIH P50HG03391. The authors are grateful to all of the workshop participants and particularly Misha Angrist, Jay Aronson, Bruce Budowle, Robert Cook-Deegan, Nita Farahany, Martha Felini, Diane Holt, Jayne Ifekwunigwe, Robin Kirk, Jose Lorente, George Maha, and Susanne Shanahan for their encouragement, cooperation, and suggestions with this and related research. Importantly, the authors thank the survey respondents for their thoughtful participation.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- CODIS

COmbined DNA Index System

- Dallas PDI

Dallas Prostitute Diversion Initiative

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- DUHS

Duke University Health Systems

- FBI

U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigations

- HRDNA database

High risk DNA Database

- HT

Human Trafficking

- NGOs

Non-Governmental Organizations

- PRIDE court

Positive Recovery Intensive Divert Experience Court

- UNICEF

United Nations International Children’s Fund

Biography

Sara H. Katsanis

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- [1].U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in persons report 2014. 2014.

- [2].United Nations Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking (UN.GIFT). Global report on trafficking in persons. February 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [3].U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in persons report 2011. 2011.

- [4].United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Annex II: Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and Children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols Thereto. Vienna, Austria: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Katsanis SH, Kim J. DNA in Immigration and Human Trafficking. In: Primorac D, Schanfield M, editors. Forensic DNA Applications: An Interdisciplinary Perspective: CRC Press; 2014. p. 539–56. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dank M, Khan B, Downey PM, et al. Estimating the size and structure of the underground commercial sex economy in eight major US cities. March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [7].U.S. Bureau of Statistics. Arrest data analysis tool. 2012.

- [8].Banks D, Kyckelhahn T. Characteristics of suspected human trafficking incidents, 2008–2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Polaris Project. National human trafficking trends in the United States. 2013.

- [10].United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Protocol to prevent, suppress and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime. November 15, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [11].United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Human trafficking FAQs. Available from http://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/faqs.html (Accessed on: June 1, 2014).

- [12].Child Welfare Information Gateway. Regulation of Private Domestic Adoption Expenses. 2013.

- [13].Groves M. Trafficking reports raise heart-wrenching questions for adoptive parents. Los Angeles Times. November 11, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Andre A. Indian parents want DNA test in Dutch adoption row. Radio Netherlands Worldwide. June 12, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Corbett S. Where do babies come from? New York Times. July 16, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Llorca JC. To save adopted girl, U.S. couple gives her up. USA Today. November 23, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Birchard K. Call for DNA testing for foreign adoptions. The Lancet. 1998; 352: 9128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Katsanis S. Use DNA to stop child trafficking. Toronto Globe and Mail. February 23, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sherwell P. Guatemalan mother reunited with baby stolen and sold for adoption by US couple. The Sunday Telegraph. July 26, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kim J, Katsanis SH. Brave new world of human-rights DNA collection. Trends Genet. 2013; 29(6): 329–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chinapen R. UNH forensic scientist targets worldwide sex trafficking through DNA. New Haven Register. March 22, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Salvio S. Being proactive in the traffic jam of human trafficking. The Charger Bulletin. February 5, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dalvi R. Human trafficking: the angle of victimology- a commentary. Law, Social Justice & Global Development Journal (LGD) [Internet]. Available from: http://www.go.warwick.ac.uk/elj/lgd/2010_2/dalvi (Accessed on: June 1, 2014)

- [24].France-Presse A. How DNA forensics could identify lost Nigerian girls. Global Post. May 6, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [25].International Commission on Missing Persons. The Missing - An Agenda for the Future: Conference Report. The Hague, The Netherlands: 2014. May 20, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Heinemann T, Lemke T. Suspect Families: DNA kinship testing in German immigration policy. Sociology. 2013; 47(4): 810–26. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Taitz J, Weekers JE, Mosca DT. DNA and immigration: the ethical ramifications. Lancet. 2002; 359(9308): 794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].DNA matching helps find 1,400 children. People’s Daily Online. September 26, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Yan Z. Database gives hope to abducted children. China Daily USA. January 22, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Thibedeau A. National forensic DNA databases. Council for Responsible Genetics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Etchegaray R, Arber W, Perez AA, et al. Statement on trafficking in human beings. November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Eisenberg A, Schade L. DNA-PROKIDS: Using DNA technology to help fight the trafficking of children. Forensic Magazine. April/May 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [33].U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Highway serial killings: new initiative on an emerging trend. April 6, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Felini M, Hampton R, Ryan E, et al. Prostitute Diversion Initiative annual report 2010–2011. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hainsworth J. Sex workers question police DNA collection. Xtra! News. March 11, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Goldstein S. Potential victims give DNA for Dallas database. The Dallas Morning News. July 9, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Roth P. Project KARE tracking several persons of interest. Calgary Sun. March 4, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [38].U.S. Department of State Bureau of Consular Affairs. Intercountry Adoption 2012. Available from: http://adoption.state.gov/about_us.php. (Accessed on: June 1, 2014)

- [39].Fuentes F, Boechat H, Northcott F. Investigating grey zones of intercountry adoption. International Reference Centre for the Rights of Children Deprived of their Family, International Social Service, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Esbenshade J. Special Report: An Assessment of DNA Testing for African Refugees. 2010.

- [41].Jamieson R, Winchester D, Stephens G, Smith S. Developing a Conceptual Framework for Identity Fraud Profiling. 16th European Conference on Information Systems. Galway, Ireland. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Thomas R. Biometrics, International Migrants and Human Rights. European Journal of Migration and Law. 2006; 7(4): 377–411. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jonassaint CR, Santos ER, Glover CM, et al. Regional differences in awareness and attitudes regarding genetic testing for disease risk and ancestry. Hum Genet. 2010; 128(3): 249–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kaufman DJ, Murphy-Bollinger J, Scott J, Hudson KL. Public opinion about the importance of privacy in biobank research. Am J Hum Genet. 2009; 85(5): 643–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Antonopoulou C, Skoufalos N. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in victims of trafficking. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2006; 5: 120. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Clawson HJ, Small KM, Go ES, Myles BW. Needs assessment for service providers and trafficking victims. Caliber, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Shrout PE, Link BG, Dohrenwend BP, et al. Characterizing life events as risk factors for depression: the role of fateful loss events. J Abnorm Psychol. 1989; 98(4): 460–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Li L, Moore D. Acceptance of disability and its correlates. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1998; 138(1): 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.