Abstract

Swiss needle cast (SNC), caused by Nothophaeocryptopus gaeumannii, is a foliage disease of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), that reduces growth in native stands and exotic plantations worldwide. An outbreak of SNC began in coastal Oregon in the mid-1990s and has persisted since that time. Here we review the current state of knowledge after 24 years of research and monitoring, with a focus on Oregon, although the disease is significant in coastal Washington and has recently emerged in southwestern British Columbia. We present new insights into SNC distribution, landscape patterns, disease epidemiology and ecology, host-pathogen interactions, trophic and hydrologic influences, and the challenges of Douglas-fir plantation management in the presence of the disease. In Oregon, the SNC outbreak has remained geographically contained but has intensified. Finally, we consider the implications of climate change and other recently emerged foliage diseases on the future of Douglas-fir plantation management.

Keywords: Swiss needle cast, Nothophaeocryptopus gaeumannii, Douglas-fir, foliage disease, Oregon

Swiss needle cast (SNC) is a foliage disease of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii [Mirb.] Franco) caused by the fungus Nothophaeocryptopus gaeumannii (T. Rohde) Videira, C. Nakash., U. Braun & Crous (Mycosphaerellaceae) (Videira et al. 2017). The Pacific coastal forests of Oregon, Washington, and southwestern British Columbia have seen SNC emerge as a significant threat to Douglas-fir plantation productivity (Hansen et al. 2000, Shaw et al. 2011, Ritóková et al. 2016, Montwé et al. 2021). The pathogen causes growth and volume loss of Douglas-fir because of reductions in gas exchange (Manter et al. 2000) and premature casting of foliage (Hansen et al. 2000, Maguire et al. 2002, 2011), although disease-caused tree mortality is rare (Maguire et al. 2011) (Figure 1). The fungus is present wherever Douglas-fir occurs but causes significant disease only in certain geographic, climatic, and management settings (Shaw et al. 2011, Lee et al. 2016, 2017, Mildrexler et al. 2019). The pathogen is native to western North America but was first described in Switzerland (Boyce 1940), hence the name, Swiss needle cast.

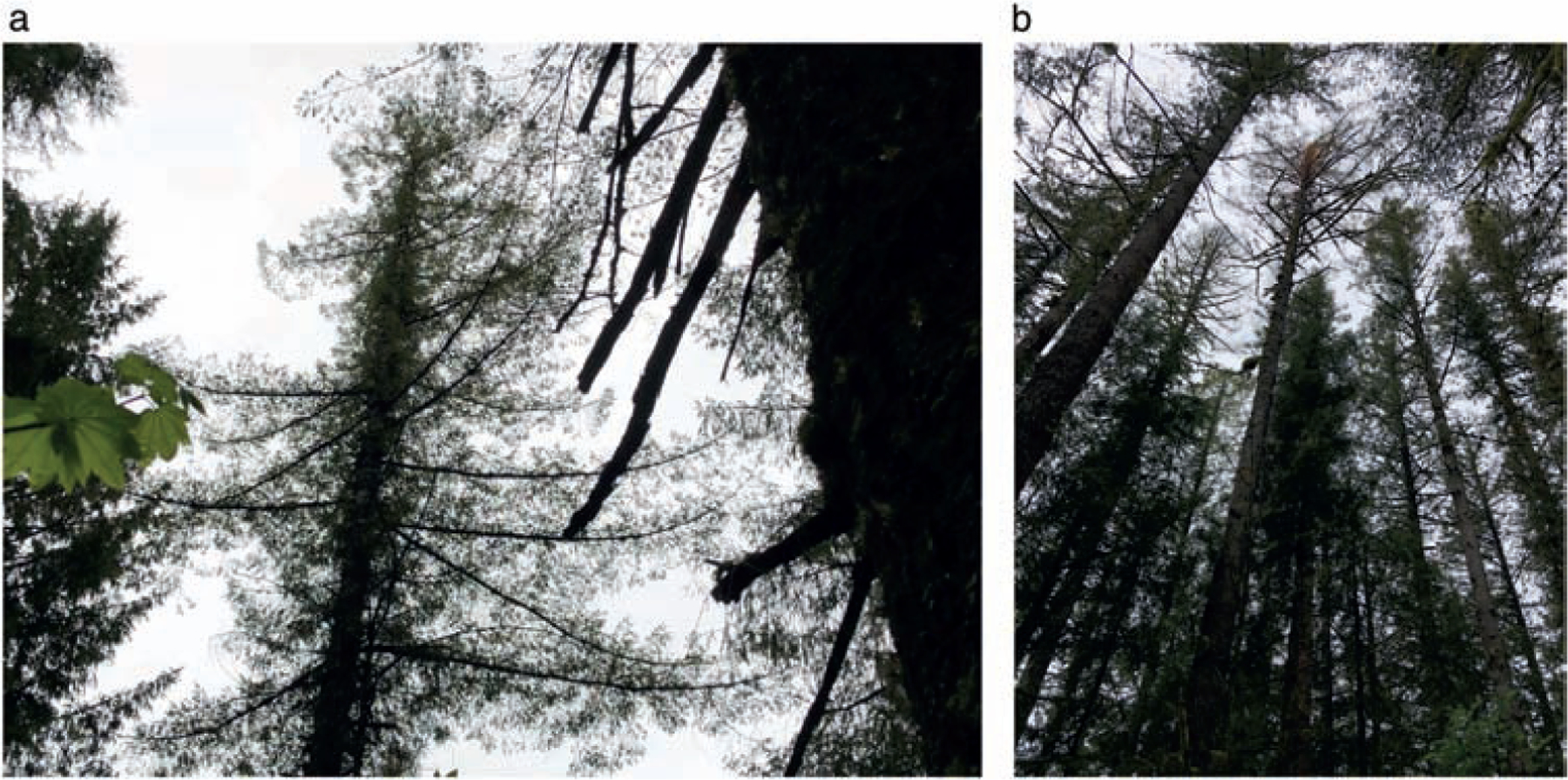

Figure 1.

Symptoms of Swiss needle cast. (a) Swiss needle cast disease symptoms (chlorotic foliage, low foliage retention) in Douglas-fir. (b) The impacts of Swiss needle cast on growth can be seen in two 40-year-old stands planted at the same time ~3 miles from the coast. Douglas-fir is the stand on the right versus western hemlock, the stand on the left. Note the western hemlock trees are larger and have created more shade, whereas the Douglas-fir are smaller and have thin crowns allowing full light to increase understory vegetation growth. The western hemlock stand was a fenced first-generation progeny test site. Photo by Gabriela Ritóková.

Nothophaeocryptopus gaeumannii is a fungus that does not directly kill the leaf. Spores land on the leaf surface, germinate, and grow hyphae into the leaf via an appressorium in a stomate (Stone et al. 2008a). Disease expression (leaf chlorosis, foliage casting and reduced diameter growth) (Figure 1a, b) is associated with spore-producing bodies (pseudothecia) that plug the stomates. Foliage is cast when approximately 25% to 50% of the stomates are plugged (Hansen et al. 2000, Manter et al. 2003). Disease severity is associated with conditions where stomatal plugging occurs on one- and two-year-old foliage, causing premature foliage casting. Foliage retention has been correlated with disease severity (Hansen et al. 2000, Manter et al. 2005, Ritóková et al. 2020), and estimates of growth impacts from SNC have been based on foliage retention in years (i.e., the number of retained annual foliage cohorts; Maguire et al. 2002, 2011). Quantifiable volume growth losses occur when fewer than three years of foliage are retained (Figure 2). Annual volume growth losses averaged ~23% for 10- to 30-year-old Douglas-fir plantations in the northwestern Oregon Coast Range, and average cubic volume growth losses can exceed 50% on the most severely infected sites (Black et al. 2010, Maguire et al. 2011).

Figure 2.

The relationship observed between foliage retention and percent volume-growth loss over four separate growth periods from 1998 to 2008 within 76 Douglas-fir stands in north coastal Oregon. Different color lines represent the foliage retention-growth loss relationship during a specific measurement period. In general, growth loss peaks at about 50–60%, and no growth loss is expected when trees retain more than three foliage cohorts.

Swiss needle cast symptoms are most severe at lower elevations near the coast and lessen with increasing elevation and distance from the ocean in western Oregon (Hansen et al. 2000, Rosso and Hansen 2003, Shaw et al. 2014). Ritóková et al. (2016) also demonstrated that foliage retention increased with increasing elevation on the west slope of the Cascade Mountains in Oregon where SNC is present, but where disease symptoms and apparent volume growth losses are limited to moist low elevation stands and follow short-term climate fluctuations. Climate in the Oregon Coast Range is influenced by the west–east elevation profile and is a significant factor related to SNC severity. Mild winter temperatures and leaf wetness during spore dispersal in May through August have been identified as the main environmental factors positively associated with the disease expression (Michaels and Chastagner 1984, Hansen et al. 2000, Manter et al. 2005). Dominant forest types within this region are Douglas-fir and western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla [Raf.] Sarg.) with a narrow zone of Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis [Bong.] Carr.) along the coast (Franklin and Dyrness 1988). The epidemic has long been associated with Douglas-fir plantations within the coastal fog belt of the Sitka spruce zone immediately adjacent to the coast, but the disease is not limited to that zone (Rosso and Hansen 2003, Ritóková et al. 2016).

Here we update the current state of knowledge after 24 years of research and monitoring, with a focus on Oregon, although the disease is significant in coastal Washington and has emerged in southwestern British Columbia. We have new insight into the spread of the disease, landscape patterns, epidemiology, ecology, and host-pathogen interactions, as well as trophic and hydrologic influences. Silviculture and management remain nuanced and closely associated with local site conditions, especially stand age (Mildrexler et al. 2019). We conclude with a synthesis of our understanding of SNC and climate change and discuss the three additional foliage diseases considered threats to Douglas-fir plantations of western Oregon.

Is the Disease Spreading in Oregon?

An aerial detection survey (USDA Forest Service, Oregon Department of Forestry Cooperative Aerial Survey, hereafter ADS) has been flown for SNC symptoms annually from 1996 to 2016, and again in 2018. Observed SNC symptoms extend inland from the coast approximately 35 km (22 miles) (Figure 3). We evaluated the SNC ADS from 1996 and 2016 except 2008 when the surveys were incomplete (Figure 4). The surveys were performed from an observation plane flown at 460 to 610 m above the terrain, following north–south lines separated by 3.2 km (Ritóková et al. 2016). Observers looked for areas of Douglas-fir forest with obvious yellowing (chlorotic) foliage and thin crowns. Polygons of forest with these symptoms were sketched onto topographic maps or ortho-photos, originally on paper and eventually on computer touchscreens. The survey area extended from the Columbia River in Oregon south to the California border and from the coastline eastward until obvious symptoms were no longer visible (Figures 3, 4).

Figure 3.

Map of Aerial Detection Survey results for Swiss needle cast in Oregon for 2018 indicating 167,165 hectares were symptomatic with chlorotic foliage and thin crowns visible from the airplane. Yellow polygons are considered moderately infected, and red are severely infected. Note the distinct regional pattern associated with distance from coast. Map source: Oregon Department of Forestry.

Figure 4.

Aerial Detection Survey results for Swiss needle cast in coastal Oregon 1996–2018. In 2017, aerial detection survey was not flown.

To determine if the disease has spread further east from the coast, we used the ArcGIS software to locate the area and centroid for each symptomatic polygon delineated by ADS. The distance from the coast to each polygon centroid was then identified. A polygon was defined as the individual area drawn on the map by the observer. For each year, the distance from the coast that contained 50%, 75%, and 95% of the total symptomatic area was determined and compared across all annual aerial surveys. The 50th, 75th, and 95th percentile distances were intended to outline the proximity of the symptomatic stands to the coast for each year. A simple linear regression was performed to predict the distance from the coast from 1996 to 2016 for each percentile.

Symptomatic hectares expanded eastward for the first few years of the study; however, very little net change occurred after that (Figure 5), even while the total symptomatic area in the coast range rose from 57,235 hectares in 1999 to 221,056 hectares in 2016 (Figure 4). The trendlines for the three percentile marks are nearly flat and none of the percentiles had an R2 value greater than 0.04. A similar pattern occurred when the years were arranged by total infected area (not shown). Though initial increases in total statewide symptomatic area were correlated with expansions eastward, once the total symptomatic area passed 80,000 hectares, the trendlines were nearly flat again and none of the percentiles had an R2 greater than 0.02. These results indicate that SNC disease has a strong geographic pattern that has remained remarkably stable.

Figure 5.

Distance from the coast that contains 50%, 75%, and 95% of all Aerial Detection Survey Swiss needle cast (SNC) symptomatic polygons from 1996 to 2016 arranged by year with data from 2008 excluded.

Mapping Disease Severity and Foliage Retention for Plantations

Douglas-fir plantation management requires a knowledge of where SNC is a problem and what the growth losses are. A new research and monitoring plot network installed by the Swiss Needle Cast Cooperative (http://sncc.forestry.oregonstate.edu), extending from the northern California border to southwestern Washington (560 km [338 miles]), and 56 km (35 miles) inland, complements the ADS survey with ground based measurements and provides an opportunity for epidemiology studies while monitoring stand volume growth impacts across a gradient of disease symptoms (Ritóková et al. 2020). The geographic setting of the new plot network includes the coastal portion of the Klamath-Siskiyou Mountains, the Oregon Coast Range, and the Willapa Hills in southwestern Washington. Precipitation and temperature vary across the region because of elevation, latitude, and rain shadow on the eastern slope of the Coast Ranges. Annual precipitation ranged from 1,200 to 4,800 mm (47–190 inches), with the majority falling as rain from October through May. Mean annual temperature ranged from 13°C to 18°C (55–64°F). Elevation of the research plots ranged from 48 to 807 m (157–2,657 feet) above sea level (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Maps of Swiss needle cast research and monitoring plot area. (a) Map of elevation across the Oregon Coast Range and location of 106 Swiss needle cast research and monitoring plots. (b) Foliage retention in years of retained foliage across the Oregon Coast Range. (c) Disease severity (incidence × pseudothecia-plugged stomate density) across the Oregon Coast Range. Black dots note the location of Swiss needle cast research and monitoring plots used as data points to make the maps b and c.

Methodology

The plot installation protocol followed the Maguire et al. (2011) procedures to remain compatible with the original growth impact sampling methodology and is described by Ritóková et al. (2020). All plots were established in plantations (10–30 years old) that had not been precommercially thinned or fertilized within five years prior to establishment. Foliage samples were collected just prior to budbreak (March–May) in the spring following plot installation in 2014, 2015, and 2016. Foliage sampling methods, including assessment of foliage retention and disease severity followed the methods of Mulvey et al. (2013b) and Ritóková et al. (2020). The SNC disease severity index was calculated by multiplying the incidence of leaves with pseudothecia by the percent pseudothecial density on individual leaves.

SNC foliage retention and disease severity continuous surface maps were created by interpolating data from 106 research plots using ordinary kriging (Figure 6b, c). The spatial extent of each surface interpolation was limited to the average distance (17 km) between the nearest five research plots used in interpolation search neighborhoods. Final maps were created by classifying continuous surface maps. All geostatistical analyses were completed using ArcGIS geographic information system (GIS) software (ESRI, 1995–2017, ArcMap version; ESRI, 2014, ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10.7.0. Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA).

Results

Our sample region encompassed a range of disease severity (0.05–52.11) and foliage retention (1.15 years to 3.9 years) (Figure 6b, c). Within crowns, disease severity was greater in the upper crown, foliage retention was greatest in the lower crown, and the pattern was consistent regardless of distance from coast (Ritóková et al. 2020). The potential site hazard maps indicate a clear distance-from-coast and elevation pattern in foliage retention (Figure 6b) and a less clear pattern in disease severity (Figure 6c). There is a strong latitudinal gradient with foliage retention decreasing and disease severity increasing from the California border to the northern coast of Oregon and into southwestern Washington State (Ritóková et al. 2020). Although we consider foliage retention to be closely related to disease severity, there are distinct differences in the maps which indicates that there is an inconsistent relationship between needle retention and disease severity (Montwé et al. 2021). However, foliage retention and disease severity are strongly related to elevation (Figure 7a, b).

Figure 7.

Elevation and disease severity and foliage retention. (a) Relationship between foliage retention and plot elevation across coastal Oregon and southwestern Washington based on the Swiss needle cast (SNC) research and monitoring plot network. Mixed linear models were applied to test the association of plot elevation with foliage retention by using R (v. 3.4.3, R Core Team 2017) packages dplyr (Wickham et al. 2017), ggplot2 (Wickham 2009), and nlme (Pinheiro et al. 2017). The association between foliage retention and plot elevation is significantly positive (p < .001). Gray area indicates 95% confidence interval. (b) Relationship between SNC severity index and plot elevation across coastal Oregon and southwestern Washington based on the SNC research and monitoring plot network. Mixed linear models were applied to test the association of plot elevation with SNC severity index by using R (v. 3.4.3, R Core Team 2017) packages dplyr (Wickham et al. 2017), ggplot2 (Wickham 2009), and nlme (Pinheiro et al. 2017). The association between SNC severity index and plot elevation is significantly negative (p < .001). Gray area indicates 95% confidence interval.

New Insights into Epidemiology, Ecology, and Host-Pathogen Interactions

Epidemiology is the study of the distribution, patterns and cause of disease focusing on why and how a disease agent is causing problems. Ecological perspectives shed light on how the patho-system relates to forest management. Although N. gaeumannii is found everywhere Douglas-fir grows, the fungus causes SNC disease in a subset of specific geographic regions associated with mild winter temperatures and late spring–summer rainfall or fog-causing leaf wetness and increased humidity. Leaf wetness during the spore dispersal period (May–August) allows good fungal colonization of the needle while warm winter temperatures appear to accelerate the timing of pseudothecia development so that pseudothecia form in one- and two-year-old foliage and cause needle casting.

Zhao et al. (2011, 2012) found correlations between coastal Douglas-fir foliage retention and a temperature-based continentality index as well as a suite of other variables encompassing seasonality of both temperature and precipitation that is consistent with epidemiological models (Manter et al. 2005). In addition, Lee et al. (2017) used tree ring width chronologies to show that SNC can affect growth across the region and is not limited to the coastal fog zone. They also found that impacts were regionally synchronous and linked to winter and summer temperatures, and summer precipitation, and the specific factor (temperature or moisture) that was more influential varied with geographic location.

Tree Age

The question of tree age and disease severity has recently been investigated by Lan et al. (2019a) who compared SNC disease severity between young (20- to 30-year-old) and mature Douglas-fir (120- to 470-year-old) across seven sites in western Oregon; three sites in the Coast Range in the epidemic area, and four sites in the Cascade Mountains outside the epidemic area. The authors found that young plantation trees had consistently higher disease severity than nearby mature/old-growth forests. In addition, SNC disease incidence (% needles with pseudothecia) was evaluated for all age classes of foliage. Incidence peaked at age two for young trees and ages three to five for mature trees. These differences are related to timing of pseudothecial development and emergence in stomates. Theories for earlier pseudothecial emergence in young trees include temperature of tree crowns, factors related to age, or differential tree genetics.

The association of SNC with younger plantations in the Oregon Coast Range is supported by Mildrexler et al. (2019), who have shown that SNC is more likely to be mapped by aerial detection surveys in the intensively managed plantations more typical of private ownership. However, older stands can exhibit substantial disease impacts. Black et al. (2010) used dendrochronological techniques to investigate SNC in mature stands at both low- and high-elevation sites near Tillamook, Oregon, and found nearly 85% growth reductions in several low elevation trees with more than 10 missing growth rings. In recent visits to the sites, it was discovered that many trees >90 years old that have been chronically infected for over 20 years died during the 2015–2018 drought (Figure 8a, b). This area has long been considered the most severely affected by SNC, such that western hemlock has supplanted Douglas-fir as the preferred plantation species.

Figure 8.

Mature Douglas-fir trees affected by Swiss needle cast. (a) Chronically affected mature Douglas-fir (~85 years) northeast of Tillamook Oregon in 2018 at Tillamook Lower (Black et al. 2010). Individual live crown; note the epicormic branching along the bole, low foliage retention, and thin crown. (b) Tree mortality associated with long term impacts of Swiss needle cast perhaps interacting with drought.

Short-Term Climate Trends and Persistence of Coastal Fog

Mildrexler et al. (2019) also found that short-term climate trends were correlated with a significant rise in symptomatic hectares documented from aerial detection survey. For the period from 2003 to 2012, they used canopy energy and water exchange data calculated from Modis Land Surface Temperature and evapotranspiration data, and PRISM (parameter-elevation relationships on independent slopes model) derived precipitation data to estimate climate trends. During this nine-year period, June and July recorded cool and moist conditions, conducive to disease development. ADS validated this presumed SNC intensification, with a reported low of 71,465 hectares in 2004, increasing to 210,184 hectares in 2012 (Figure 4).

The link with the coastal region has often been associated with summer fog (Rosso and Hansen 2003), but quantification of fog and low clouds across the region has remained elusive. Dye et al. (2020) have recently developed the first documentation of low clouds for the entire region over the 22-year period 1996–2017. Their analysis shows that occurrence of low clouds (including fog) in May, June, and July are a significant characteristic of the lower elevations of the coastal strip along the west side of the Oregon Coast Range. The subsequent moist conditions, in combination with ocean-moderated mild winter temperatures could explain why the SNC outbreak area has remained geographically contained during that period with distance from coast defining the epidemic (Figure 5). Whether the results of Dye et al. (2020) constitute a change in conditions relative to prior periods is unknown.

Seed Source

Wilhelmi et al. (2017) investigated a seed source movement trial that used coastal Douglas-fir seed sources from southwestern Washington, western Oregon, and northwestern California to determine the susceptibility to foliage diseases. N. gaeumannii and Rhabdocline species (cause of Rhabdocline needle cast) were important within the study and seed source was shown to affect susceptibility to these diseases. Trees grown from seed sourced from drier habitats moved to wetter habitats, and from higher elevations to lower elevations showed increased SNC and Rhabdocline needle cast. This is consistent with the hypothesis expressed in Hansen et al. (2000) that establishment of Douglas-fir in coastal zones previously dominated by Sika spruce, western hemlock, and red alder, and establishment of Douglas-fir stands using seeds sourced from drier areas further east have a role in the origins of the epidemic. Douglas-fir shows genetic tolerance to N. gaeumannii, in that all seed sources have leaves that are equally susceptible to infection no matter what the environment. Tolerant trees have greater foliage retention and crown fullness, however.

Lineages of Nothophaeocryptopus gaeumannii

There are two, noninterbreeding lineages of N. gaeumannii (Lineage 1 and Lineage 2) (Winton et al. 2006, Bennett and Stone 2019) in coastal Pacific Northwest forests, and a third lineage (Lineage 1i) has been identified in the interior of British Columbia, Canada, and the Northern Rocky Mountains, USA (Hamelin and Feau, University of British Columbia, 2020, pers. commun.). Although these lineages are noninterbreeding, they require molecular analysis to determine the differences. In Oregon, Lineage 2 is closely associated with the coast, and Lineage 1 is more widespread, reflecting the gradient of environmental conditions (Winton et al. 2006, Bennett and Stone 2019). Investigations into whether any of these lineages are more pathogenic than the other are inconclusive (Bennett and Stone 2019).

Effects on the Tree

The implications of N. gaeumannii infection on nonstructural carbohydrates associated with stomate blockage was investigated by Saffell et al. (2014b). The study provides insight into carbon dynamics because water stress was low, and carbon uptake was not influenced by drought. In a highly diseased stand, mean basal area increment growth decreased by about 80% and nonstructural stem carbohydrates decreased by about 60% across a gradient of foliage mass reduction. However, twig and foliage nonstructural carbohydrate concentrations remained constant with decreasing foliage mass. Douglas-fir trees retained nonstructural carbohydrates in the crown at the expense of trunk radial growth which allowed for foliage growth and shoot extension in the spring.

In a study of tree-ring stable isotopes in a fungicide treated plantation versus an adjacent untreated plantation, Saffell et al. (2014a) showed that isotopes record the impact of N. gaeumannii on CO2 assimilation and growth. Fungicide only protects current year foliage from infection and the fungicide treatment occurred for five consecutive years in the treated plantation. As foliage retention increased following treatment, the annual basal area increment doubled by the fifth year compared with the untreated stand. After treatment stopped, it took about four years of steady growth reductions before increment in the two stands were similar, indicating that N. gaeumannii was the cause of growth impacts. The ability of Douglas-fir to discriminate against carbon stable isotope (∆13C) increased in the treated stand, supporting the contention that N. gaeumannii is causing carbon starvation. The authors also found that tree ring ∆13C was negatively correlated with relative humidity during the two previous summers, supporting the contention that summer climate is important.

Hydrologic and Trophic Interactions

In the first study to show a forest pathogen can influence watershed hydrologic regimes, N. gaeumannii was shown to influence catchment scale hydrology in the Oregon Coast Range (Bladon et al. 2019). Bladon and colleagues investigated 1990–2015 annual streamflow, runoff ratio, and the magnitude and timing of peak flows and low flows for 12 catchments in areas with 0 to 90% of the catchments mapped with SNC symptoms by ADS surveys. They found that in catchments with >10% ADS area mapped, that the runoff ratios increased. However, in the two most heavily affected catchments, with ~50–90% of the area mapped by ADS, there was no effect. They hypothesized that this was due to vegetation compensation—that is, growth of non-Douglas-fir conifers, hardwoods, and shrubs increased because of the negative impact of SNC on Douglas-fir (Zhao et al. 2014a).

Studies also indicate that trophic interactions are altered by N. gaeumannii, including mycorrhizae and the Douglas-fir beetle (Dendroctonus pseudotsugae) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Luoma and Eberhart (2014) investigated the relationship between Swiss needle cast and ectomycorrhizal fungus diversity in the Oregon Coast Range across a gradient of disease severity. They found that ectomycorrhizal diversity varied 10-fold across the sites and ectomycorrhizal species richness varied about 2.5-fold. Both ectomycorrhizal diversity and species richness were positively related to increasing foliage retention. Carbon starvation may be the reason for the reduction in ectomycorrhizal fungi diversity and abundance, and this likely causes a trophic cascade below ground.

The lack of evidence for SNC-induced mortality in Douglas-fir plantations (Maguire et al. 2011) is partially because of the decreased likelihood of secondary mortality agents. For example, the Douglas-fir beetle is not attracted to SNC diseased Douglas-fir trees (Kelsey and Manter 2004). Carbon starvation and lack of tree resources for production of protective chemicals and ethanol may be the reason. Kelsey and Manter (2004) found that woody tissue ethanol concentrations, wound-induced resin flow, and beetle attraction were reduced as the severity of SNC increased. Because there has not been increased Douglas-fir beetle activity associated with the SNC outbreak, the authors speculate that pioneering beetles do not recognize stressed SNC infected trees because of a lack of an ethanol signal.

Silviculture and Plantation Management

Management of SNC-infected stands can be coarsely directed by the known gradient of disease severity on the landscape (Figure 6). A one-size fits all approach ignores opportunities for effectual production of Douglas-fir throughout the coastal region (Shaw et al. 2011, Mulvey et al. 2013a, Zhao et al. 2014b). Integrated pest management is recommended and the suggested approach to SNC stand management includes three steps. First, a site hazard assessment should incorporate ADS and models of SNC impacts on foliage retention (Figure 6b), to assess the current and future likelihood of disease impacts. Second, stand impact assessments should be made using average stand foliage retention, verification of N. gaeumannii, and quantitative growth impact assessments. Determining whether growth reductions are occurring is a key step because deviating from normal plantation management practices should be based on knowledge of whether growth reductions are occurring. Finally, silvicultural decisions should be site specific, informed by both biological and economic risk factors.

Precommercial and commercial thinning can be used in conjunction with species selection to improve the stand (Zhao et al. 2014b). Variation in disease tolerance within individuals is observed in the field (Zhao et al. 2014a); therefore, thinning from below can remove Douglas-fir with sparse crowns and small sizes indicative of low disease tolerance. Western hemlock is a codominant species in the near-coastal region of Oregon that naturally seeds into Douglas-fir plantations. In severely affected Douglas-fir stands, western hemlock can outcompete Douglas-fir even seeding in two or three years later (Figure 1b). Some landowners use a diameter-minus rule for precommercial thinning where western hemlock is common (Zhao et al. 2014b), dictating the retention of small hemlocks and removal of larger neighboring Douglas-fir in expectation of better long-term results for hemlock. The size difference in diameter dictating such decisions (diameter-minus) depends on absolute tree size, and SNC intensity.

Silvicultural techniques that are traditionally used to reduce foliage disease by drying the canopy through increased air circulation, including thinning, vegetation management, and pruning, are not effective at reducing SNC within a planation (Mainwaring et al. 2005, Shaw et al. 2011). Thinning and vegetation management have been shown to increase individual Douglas-fir tree growth in diseased stands, but growth rates will be reduced relative to healthy stands (Mainwaring et al. 2005). Fungicides have been shown to be effective in plantations (Stone et al. 2007, Saffell et al. 2014a), but their use is neither cost effective nor environmentally friendly, requiring annual applications because only current-year foliage is colonized by N. gaeumannii.

Species choice at planting is generally driven by economic factors and management familiarity, but alternative species such as western hemlock, currently less valuable, can be included in increasing proportion as the known or expected disease severity of the site increases. The seed source of planted stock is important, with sources from drier regions moved to wetter regions, or higher elevations moved to lower elevations, being particularly susceptible to both SNC and Rhabdocline needle casts (Wilhelmi et al. 2017). Traditional tree improvement focused on genetic tolerance is an important part of the overall goal of managing Douglas-fir for Swiss needle cast (Jayawickrama et al. 2012, Montwé et al. 2021), but some locations exhibit such high disease severity that Douglas-fir is not advised and western hemlock has emerged as a preferred species (Kastner et al. 2001).

Although the hypothesis that higher foliage N increases disease is still unclear (Mulvey et al. 2013b), fertilization of diseased stands with N is not advised, with multiple fertilizer trials in diseased stands having repeatedly shown no positive growth responses (Mainwaring et al. 2014). Lan et al. (2019b), using the SNC research and monitoring network, recently confirmed that higher N in foliage is associated with higher disease, but this covaries with climate factors and distance from coast, so it is difficult to disassociate from epidemiological factors.

Climate Change

Seasonal changes in precipitation and temperature rather than increasing tree stress will influence SNC, as well as other foliage diseases (Kliejunas et al. 2009, Agne et al. 2018). Temperature is a key non-growing-season epidemiological factor described by Manter et al. (2005). Stone et al. (2008b), Watt et al. (2010), and Lee et al. (2017) suggest that winter temperatures will influence SNC impacts in future climate scenarios, and that if conditions in late spring to midsummer result in some periods of leaf wetness, SNC impacts will increase at higher elevations and higher latitudes. A dendrochronological investigation of heavily affected mature stands in the Tillamook area found that SNC-associated basal area growth reductions became evident in the 1980s and have persisted since that time (Black et al. 2010). According to the Oregon Coastal Climate Division of NOAA, the average minimum November–April temperatures since the mid-1980s have generally been above the 1901–2000 average (Figure 9), possibly indicating that warming winter temperature has already played a role in the SNC epidemic of coastal Oregon.

Figure 9.

Minimum temperature time series from 1895 to 2020 for the six-month period, November–April for Division 1, Coastal Oregon. Note that since the 1980s, temperatures have tended to be warmer. Source: NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Divisional Time Series, Division 1 (coastal) Oregon Climate.

Late spring and summer precipitation and fog that wets Douglas-fir leaves is key to disease intensification. Mildrexler et al. (2019) have shown that consistently cool and wet weather in the coastal Oregon during May–July from 2004 to 2014 correlated with an increase in SNC ADS area (Figure 4). However, drought, drier spring and summer weather, and longer, drier, and hotter growing seasons will reduce SNC presence or impacts because of poor colonization of foliage when conditions are dry. Precipitation changes are difficult to predict along the coast, but spring precipitation may remain similar and summers will likely be drier, for the period 2010–2039 compared with 1971–2000 (MACA Summary Projections using higher emissions, RCP 8.5, https://climate.northwestknowledge.net/MACA/tool_summarymaps2.php), so that the disease may persist along the coast into the future even if the inland sites dry out more as predicted.

The Suite of Foliage Diseases in Coastal Douglas-Fir

Over the past decade, two new foliage diseases have emerged as potential threats to Douglas-fir plantations (LeBoldus et al. 2019). These include web blight (Rhizoctonia butinii) (Chastagner and LeBoldus 2018) and Phytophthora needle cast (Phytophthora pluvialis) (Williams and Hansen 2018) of Douglas-fir. Rhabdocline needle cast (several Rhabdocline species) (Stone 2018) is a well-known disease associated with off-site plantings and may emerge if assisted migration is employed without field testing (Wilhelmi et al. 2017). Although these new diseases do not currently appear to be affecting forest plantation management to the degree that SNC does, this complex of diseases could threaten Douglas-fir management as environmental and management conditions change.

Phytophthora needle cast, also called red needle cast in New Zealand, is a foliage Phytophthora recently described in western Oregon and about the same time observed in Douglas-fir and radiata pine in New Zealand where is it causing significant damage (Hansen et al. 2015, Williams and Hansen 2018). Although it is widespread in western Oregon, it does not appear to be causing significant damage in Douglas-fir plantations (Hansen et al. 2017). Gómez-Gallego et al. (2019) contrasted pathogen loads in coexisting populations of P. pluvialis and N. gaeumannii in New Zealand and the Pacific Northwest, USA. They found that both pathogens were more abundant in New Zealand than the Pacific Northwest, and that in the Pacific Northwest, their abundance in the same leaf was negatively correlated.

Web blight is widespread and more commonly observed than Phytophthora needle cast, but anecdotal observations suggest it is most important in lower crowns of dominant and codominant canopy class Douglas-fir trees in plantations and understory trees such as western hemlock in mixed and older stands (Chastagner and LeBoldus 2018, LeBoldus et al. 2019; personal observations by the authors). In general, our knowledge of the role of Phytophthora needle cast and web blight in natural and managed forests of western Oregon is in its infancy, and epidemiological and ecological studies are needed. It is generally believed that P. pluvialis is native to western Oregon (Hansen et al. 2017), and it is not known if R. butinii is native or not.

Conclusions

Swiss needle cast will continue to be an issue for coastal Douglas-fir into the near future, and the lower elevations of the western Cascade Mountains are also a region of potential SNC impacts. Warmer winter temperatures combined with leaf wetness during May–July will lead to disease intensification and increased impacts at increasingly higher elevations. The scale of the disease on the landscape is influencing forest productivity, hydrologic regimes, as well as trophic interactions and biodiversity belowground. Continued research and development of genetically improved, tolerant Douglas-fir for plantations is critical to long-term management, while care must be taken in moving seed sources from drier regions into the coast range of Oregon. Although disease severity and needle retention can be estimated from models and maps (Figure 6), individual stand management is quite nuanced, site specific, and entails an informed approach based on how the disease is actually influencing the stand.

The tree microbiome is the new frontier of forest pathology, and knowledge of the dynamics of the entire microbial community of Douglas-fir foliage could lead to major breakthroughs in our understanding of SNC because interactions with other fungi and bacteria in the leaf may influence N. gaeumannii. At the leaf level, there is also a need to understand more about the internal nutrient acquisition of the fungus. Other key research needs include the role of temperature in the timing of pseudothecial development and investigations of whether temperature of the leaf is distinct in young, even-aged plantations versus mature and older stands, and whether this can be explained by stand structure. The influence of soils and foliage chemistry and linkages to climate and distance from coast require more inquiry to try to separate these confounding factors.

Study Implications:

Douglas-fir tree growers need to consider Swiss needle cast (SNC) and other emerging foliage diseases as SNC has not abated over the past 24 years, and along with other emerging diseases, it continues to pose a threat to Douglas-fir plantation productivity. Douglas-fir management in western Oregon remains important, such that a knowledge of disease impacts and effective silvicultural responses is key. Managers should carefully consider whether alternative species may be ecologically or economically beneficial in some situations while tree improvement programs must continue to breed for tolerance to SNC. Research shows that regional scale foliage disease outbreaks can result in trophic cascades and hydrologic changes that affects more than just the trees.The environmental controls on the SNC epidemic imply that climate change could strongly influence future directions of the outbreak, with the greatest threats to trees at higher elevations.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the US Environmental Protection Agency.

We would like to thank the Swiss Needle Cast Cooperative members (Cascade Timber Consulting, Lewis & Clark Tree Farms, Greenwood Resources, Oregon Department of Forestry, Starker Forests, Stimson Lumber, USDA Forest Service, Weyerhaeuser Company) and the College of Forestry, Oregon State University (OSU) for assistance and financial support. We are grateful to Bureau of Land Management, Hampton Affiliates, Hancock Forest Management, Menasha Campbell Global (currently Rayonier), OSU College of Forests, Roseburg Resources, South Coast Lumber, Washington DNR, and other landowners who gave us permission to establish research plots on their lands and at times provided assistance in the field.

Literature Cited

- Agne MC, Beedlow PA, Shaw DC, Woodruff DR, Lee EH, Cline S, and Comeleo RL. 2018. Interactions of predominant insects and diseases with climate change in Douglas-fir forests of western Oregon and Washington, U.S.A. For. Ecol. Manage 409(February):317–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PI, and Stone JK. 2019. Environmental variables associated with Nothophaeocryptopus gaeumannii populations structure and Swiss needle cast severity in Western Oregon and Washington. Ecol. Evol 9(19):11379–11394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black BA, Shaw DC, and Stone JK. 2010. Impacts of Swiss needle cast on overstory Douglas-fir forests of the western Oregon Coast Range. For. Ecol. Manage 259(8):1673–1680. [Google Scholar]

- Bladon KD, Bywater-Reyes S, LeBoldus JM, Keriö S, Segura C, Ritóková G, and Shaw DC. 2019. Increased streamflow in catchments affected by a forest disease epidemic. Sci. Total Environ 691(November):112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce JS 1940. A needle-cast of Douglas fir associated with Adelopus gäumanni. Phytopathology 30:649–659. [Google Scholar]

- Chastagner G, and LeBoldus J. 2018. Web blight. P. 128– 130 in Compendium of conifer diseases, Hansen EM, Lewis KJ, and Chastagner GA (eds.). APS Press, St. Paul, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Dye AW, Rastogi B, Clemesha RES, Kim JB, Samelson RM, Still CJ, and Williams AP. 2020. Spatial patterns and trends of summertime low cloudiness for the Pacific Northwest, 1996–2017. Geophys. Res. Lett 47(16):e2020GL088121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JF, and Dyrness CT. 1988. Natural vegetation of Oregon and Washington Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, OR. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Gallego M, LeBoldus JM, Bader MK-F, Hansen E, Donaldson L, and Williams NM. 2019. Contrasting the pathogen loads in coexisting populations of Phytophthora pluvialis and Nothophaeocryptopus gaeumannii in Douglas fir plantations in New Zealand and the Pacific Northwest United States. Phytopathology 109(11):1908–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen EM, Reeser PW, and Sutton W. 2017. Ecology and pathology of Phytophthora ITS glade 3 species in forests in western Oregon, USA. Mycologia 109(1):100–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen EM, Reeser PW, Sutton W, Gardner J, and Williams N. 2015. First report of Phytophthora pluvialis causing needle loss and shoot dieback on Douglas-fir in Oregon and New Zealand. Plant Dis 99(5):727. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen EM, Stone JK, Capitano BR, Rosso P, Sutton W, Winton L, Kanaskie A, and McWilliams MG. 2000. Incidence and impact of Swiss needle cast in forest plantations of Douglas-fir in coastal Oregon. Plant Dis 84(7):773–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayawickrama KJS, Shaw D, and Ye TZ. 2012. Genetic selection in coastal Douglas-fir for tolerance to Swiss needle cast disease P. 256–261 in Proceedings of the fourth international workshop on the genetics of host-parasite interactions in forestry: Disease and insect resistance in forest trees, Sniezko RA, Yanchuk AD, Kliejunas JT, Palmieri KM, Alexander JM, Frankel SJ (tech. cords). USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-240, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Albany, CA. 372 p. [Google Scholar]

- Kastner WW Jr., Dutton SM, and Roché DM. 2001. Effects of Swiss needle cast on three Douglas-fir seed sources on a low-elevation site in the northern Oregon Coast Range: Results after five growing seasons. West. J. Appl. For 16(1):31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey RG, and Manter DK. 2004. Effect of Swiss needle cast on Douglas-fir stem ethanol and monoterpene concentrations, oleoresin flow, and host selection by the Douglas-fir beetle. For. Ecol. Manage 190(2–3):241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Kliejunas JT, Geils BW, Glaeser JM, Goheen EM, Hennon P, Kim M-S, Kope H, Stone J, Sturrock R, and Frankel SJ. 2009. Review of literature on climate change and forest diseases of western North America. USDA Forest Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-225, Pacific Southwest Research Station, Albany, CA. 54 p. [Google Scholar]

- Lan Y-H, Shaw DC, Beedlow PA, Lee EH, and Waschmann RS. 2019a. Severity of Swiss needle cast in young and mature Douglas-fir forests in western Oregon, USA. For. Ecol. Manage 442(June):79–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan Y-H, Shaw DC, Ritóková G, and Hatten JA. 2019b. Associations between Swiss needle cast severity and foliar nutrients in young-growth Douglas-fir in coastal western Oregon and southwestern Washington, USA. For. Sci 16(5):537–542. [Google Scholar]

- LeBoldus J, Shaw D, and Reeser P. 2019. Emerging threats to conifer foliage. Digger Magazine April 2019:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lee EH, Beedlow PA, Waschmann RS, Tingey DT, Wickham C, Cline S, Bollman M, and Carlile C. 2016. Douglas-fir displays a range of growth responses to temperature, water, and Swiss needle cast in western Oregon, USA. Agric. For. Meteorol 221(May):176–188. [Google Scholar]

- Lee EH, Beedlow PA, Waschmann RS, Tingey DT, Cline S, Bollman M, Wickham C, and Carlile C. 2017. Regional patterns of increasing Swiss needle cast impacts on Douglas-fir growth with warming temperatures. Ecol. Evol 7(24):11167–11196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma DL, and Eberhart JL. 2014. Relationship between Swiss needle cast and ectomycorrhizal fungus diversity. Mycologia 106(4):666–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire D, Kanaskie A, Voelker W, Johnson R, and Johnson G. 2002. Growth of young Douglas-fir plantations across a gradient in Swiss needle cast severity. West. J. Appl. For 17(2):86–95. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire DA, Mainwaring DB, and Kanaskie A. 2011. Ten-year growth and mortality in young Douglas-fir stands experiencing a range in Swiss needle cast severity. Can. J. For. Res 41(10):2064–2076. [Google Scholar]

- Mainwaring DB, Maguire DA, Kanaskie A, and Brandt J. 2005. Growth responses to commercial thinning in Douglas-fir stands with varying severity of Swiss needle cast in Oregon, USA. Can. J. For. Res 35(10):2394–2402. [Google Scholar]

- Mainwaring DB, Maguire DA, and Perakis SS. 2014. Three-year growth response of young Douglas-fir to nitrogen, calcium, phosphorus, and blended fertilizers in Oregon and Washington. For. Ecol. Manage 327(September):178–188. [Google Scholar]

- Manter DK, Bond BJ, Kavanagh KL, Rosso PH, and Filip GM. 2000. Pseudothecia of Swiss needle cast fungus, Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii, physically block stomata of Douglas fir, reducing CO2 assimilation. New Phytol 148(3):481–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manter DK, Bond BJ, Kavanagh KL, Stone JK, and Filip GM. 2003. Modelling the impacts of the foliar pathogen, Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii, on Douglas-fir physiology: Net canopy carbon assimilation, needle abscission and growth. Ecol. Modell 164(2–3):211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Manter DK, Reeser PW, and Stone JK. 2005. A climate-based model for predicting geographic variation in Swiss needle cast severity in the Oregon Coast Range. Phytopathology 95(11):1256–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels E, and Chastagner GA. 1984. Seasonal availability of Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii ascospores and conditions that influence their release. Plant Dis 68(11):942–944. [Google Scholar]

- Mildrexler DJ, Shaw DC, and Cohen WB. 2019. Shortterm climate trends and the Swiss needle cast epidemic in Oregon’s public and private coastal forestlands. For. Ecol. Manage 432(January):501–513. [Google Scholar]

- Montwé D, Bryan E, Socha P, Wyatt J, Noshad D, Feau N, Hamelin R, Stoehr M, and Ehlting J. 2021. Swiss needle cast tolerance in British Columbia’s coastal Douglas-fir breeding population. Forestry 94(2):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey RL, Shaw DC, Filip GM, and Chastagner GA. 2013a. Swiss needle cast USDA Forest Service Forest Insect and Disease Leaflet (FIDL) 181, FS/R6/RO/FIDL#181–13/001, Northwest Region (R6), Portland, OR. 16 p. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey RL, Shaw DC, and Maguire DA. 2013b. Fertilization impacts on Swiss needle cast disease severity in western Oregon. For. Ecol. Manage 287(January):147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, and R Core Team. 2017. nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–131 Available online at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme; last accessed March 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2017. R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online at https://www.R-project.org/; last accessed March 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ritóková G, Mainwaring DB, Shaw DC, and Lan Y-H. 2020. Douglas-fir foliage retention dynamics across a gradient of Swiss needle cast in coastal Oregon and Washington. Can. J. For. Res Available online at 10.1139/cjfr-2020-0318; last accessed March 9, 2021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritóková G, Shaw DC, Filip G, Kanaskie A, Browning J, and Norlander D. 2016. Swiss needle cast in western Oregon Douglas-fir plantations: 20-year monitoring results. Forests 7(8):155. [Google Scholar]

- Rosso PH, and Hansen EM. 2003. Predicting Swiss needle cast disease distribution and severity in young Douglas-fir plantations in coastal Oregon. Phytopathology 93(7):790–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffell BJ, Meinzer FC, Voelker SL, Shaw DC, Brooks JR, Lachenbruch B, and McKay J. 2014a. Tree-ring stable isotopes record the impact of a foliar fungal pathogen on CO2 assimilation and growth in Douglas-fir. Plant, Cell Environ 37(7):1536–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffell BJ, Meinzer FC, Woodruff DR, Shaw DC, Voelker SL, Lachenbruch B, and Falk K. 2014b. Seasonal carbohydrate dynamics and growth in Douglas-fir trees experiencing chronic, fungal-mediated reduction in functional leaf area. Tree Physiol 34(3):218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DC, Filip GM, Kanaskie A, Maguire DA, and Littke W. 2011. Managing an epidemic of Swiss needle cast in the Douglas-fir region of Oregon: The Swiss Needle Cast Cooperative. J. For 109(March 2011):109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DC, Woolley T, and Kanaskie A. 2014. Vertical foliage retention in Douglas-fir across environmental gradients of the western Oregon coast range influenced by Swiss needle cast. Northwest Sci 88(1):23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stone J 2018. Rhabdocline needle cast. P. 108–110 in Compendium of conifer diseases, Hansen EM, Lewis KJ, and Chastagner GA (eds.). APS Press, St. Paul, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Stone JK, Capitano BR, and Kerrigan JL. 2008a. The histopathology of Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii on Douglas-fir needles. Mycologia 100(3):431–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JK, Coop LB, and Manter DK. 2008b. Predicting the effects of climate change on Swiss needle cast disease severity in Pacific Northwest forests. Can. J. Plant Pathol 30(2):169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Stone JK, Reeser PW, and Kanaskie A. 2007. Fungicidal suppression of Swiss needle cast and pathogen reinvasion in a 20-year-old Douglas-fir stand in Oregon. West. J. Appl. For 22(4):248–252. [Google Scholar]

- Videira SIR, Groenewald JZ, Nakashima C, Braun U, Barreto RW, de Wit PJGM, and Crous PW. 2017. Mycosphaerellaceae – chaos or clarity? Stud. Mycol 87(June):257–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MS, Stone JK, Hood IA, and Palmer DJ. 2010. Predicting the severity of Swiss needle cast on Douglas-fir under current and future climate in New Zealand. For. Ecol. Manage 260(December):2232–2240. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H 2009. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis Springer-Verlag, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, Francois R, Henry L, and Müller K. 2017. dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation. R package version 0.7.4 Available online at https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr; last accessed March 9, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmi NP, Shaw DC, Harrington CA, Clair JB St., and Ganio LM. 2017. Climate of seed source affects susceptibility of coastal Douglas-fir to foliage diseases. Ecosphere 8(12):e02011. [Google Scholar]

- Williams N, and Hansen E. 2018. Red needle cast. P. 16– 18 in Compendium of conifer diseases, Hansen EM, Lewis KJ, and Chastagner GA (eds.). APS Press, St. Paul, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Winton LM, Hansen EM, and Stone JK. 2006. Population structure suggests reproductively isolated lineages of Phaeocryptopus gaeumannii. Mycologia 98(5):781–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Maguire DA, Mainwaring DB, and Kanaskie A. 2014a. Western hemlock growth response to increasing intensity of Swiss needle cast on Douglas-fir: Changes in the dynamics of mixed-species stands. Forestry 87(5):697–704. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Maguire DA, Mainwaring D, Wehage J, and Kanaskie A. 2014b. Thinning mixed-species stands of Douglas-fir and western hemlock in the presence of Swiss needle cast: Guidelines base on relative basal area growth of individual trees. For. Sci 60(1):191–199. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Maguire DA, Mainwaring DB, and Kanaskie A. 2012. Climatic influences on needle cohort survival mediated by Swiss needle cast in coastal Douglas-fir. Trees 26:1361–1371. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Mainwaring DB, Maguire DA, and Kanaskie A. 2011. Regional and annual trends in Douglas-fir foliage retention: Correlations with climatic variables. For. Ecol. Manage 262(9):1872–1886. [Google Scholar]