Abstract

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) is associated with a poor outcome in breast cancer. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the clinical significance of LVI in primary breast cancer and to investigate disease-free survival as a prognostic marker according to the breast cancer subtypes. This study examined 4,652 consecutive cases of invasive breast cancer excluding the patients with non-invasive cancer, stage IV and those who underwent neo-adjuvant therapy from February 2002 to February 2021. The clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of LVI-positive and -negative tumors were compared. LVI was evaluated in H&E staining specimens from surgically resected samples. The LVI expression rates were 29.2% (low, 19.7%; high, 9.5%) in all primary cases. The LVI-positive rate was significantly associated with specimens with the following characteristics: ER/PgR-negative, HER2-positive, p53 overexpression, higher Ki-67 index values, higher nuclear grade, positive nodes and larger tumors. Moreover, the subtypes were significantly associated with LVI positivity; 20% in Luminal A, 34.6% in Luminal B, 40.9% in Lumina/HER2, 38.1% in HER2-enriched and 29.8% in triple negative (TN). There were significant differences in disease-free survival between LVI status in Luminal A, Luminal B and TN subtypes, but there was no difference in the Luminal/HER2 and HER2-enriched subtypes. A multivariate analysis revealed that LVI was a significant factor in Luminal B and TN subtypes. Overall, LVI was significantly associated with the advanced and aggressive characteristics in breast cancer. Luminal A type had a lower LVI rate, and HER2 type had a higher LVI rate. Moreover, LVI was a significant prognostic factor in Luminal B and TN subtypes. These data suggested that the LVI status was useful in predicting the prognosis in HER2 negative breast cancer cases.

Keywords: lymphovascular invasion, breast cancer, subtype, disease-free survival, Ki-67, estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common cancer diagnosed among women in Japan and globally (1). The number of breast cancer cases among women in Japan was estimated to be the highest at ~92,000 in 2020 (2).

Identification of clinically predictive and prognostic factors is important in the treatment of BC. Various prognostic and predictive factors for BC have been recognized by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) to guide the clinical management of BC patients. The prognostic factors for BC are lymph node status, tumor size, lymphatic/vascular invasion, age, histologic grade, histologic subtypes (i.e. tubular, mucinous, or papillary), response to neoadjuvant therapy, estrogen receptor (ER)/progesterone receptor (PgR) status, HER2 gene amplification or HER2 protein overexpression (3). Metastasis of the axillary lymph nodes is an indication that the BC may have spread to other organs. Survival and recurrence are independent of level of involvement but are directly related to the number of involved nodes.

There are five main intrinsic or molecular subtypes of BC that are derived from immunohistochemistry (IHC) of ER/PgR, HER2, and Ki-67. They are Luminal A, Luminal B, Luminal/HER2, HER2 enriched and Triple Negative (TN) subtypes. The subtypes are important to predict the biology, response to therapy and prognosis of each case.

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI) is defined as the invasion of the vessel walls by tumor cells and/or the presence of tumor emboli within an endothelial-lined space. LVI may be considered as the initial stage for lymph node metastasis and other types of organ metastases. Moreover, LVI is associated with a poor outcome in several types of cancer such as colorectal (4), urothelial (5), prostate (6) and uterine endometrial cancer (7) other than BC. The first study on the prognostic significance of LVI in BC was published in 1964 (8). The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical significance of LVI in primary BC and to investigate disease-free survival (DFS) as a prognostic marker according to the BC subtypes. The clinical significance of LVI was analyzed to investigate the biology and prognosis.

Patients and methods

Patients

This study examined 4,652 consecutive invasive BC cases excluding the patients with non-invasive cancer, Stage IV and those who underwent neo-adjuvant therapy from February 2002 to February 2021 at Kumamoto City Hospital and Kumamoto Shinto General Hospital. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Kumamoto Shinto General Hospital. The clinicopathological factors investigated were menopausal status, nodal status, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), tumor size, nuclear grade, ER/PgR and HER2 status, p53 overexpression and the Ki-67 index value. Invasive BC was divided into 5 subtypes according to the IHC data derived from ER/PgR, HER2 and the Ki-67 index values (cutoff point: 20%). Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all of the patients. The clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of LVI positive and negative tumors were compared.

Histopathological examination

Immunostaining for ER, PgR, p53, Ki-67 and HER2 was conducted using the same procedure (9) as the autostainer (Benchmark XT; Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, USA). The positive cell rates for ER/PgR were determined by IHC using the monoclonal rabbit ER-antibody SP1/PgR-antibody 1E2 and a value of ≥1% was considered positive. The antibodies used for IHC were HER2 (clone 4B5; rabbit monoclonal; all Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.), p53 (clone DO7; mouse monoclonal) and Ki-67 (clone MIB-1; mouse monoclonal; both Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The positive rate for Ki-67 was calculated based on a count of at least 500 tumor cells in the hot spot and the value was represented as a percentage. The p53 overexpression was predetermined to be the number of cases with a positive cell count of ≥50% (10). The HER2 status was dichotomized into positive and negative cases using IHC and the FISH test. Cases with IHC3+ (strong and diffuse staining) or FISH amplified were identified as HER2 positive.

Lymphovascular invasion (LVI)

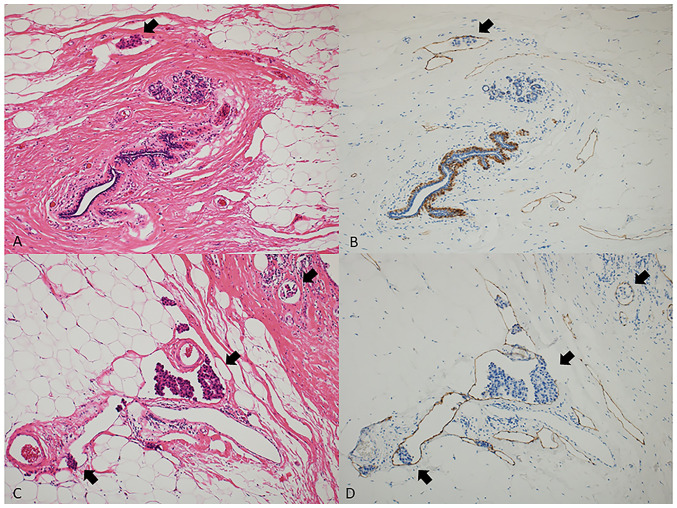

LVI was routinely evaluated at peritumoral areas in hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining specimens from surgically resected samples. LVI was defined as the presence of carcinoma cells (LVI positive; high and low) within the lymphatic vessel. When the results were undetermined mainly due to the difficulty in excluding tissue retraction artifacts, a specific marker for lymphatic endothelium (podoplanin, clone D2-40, mouse monoclonal, Dako) was used to identify the endothelium-lined lymphatic spaces. Fig. 1 shows the detection of low (A and B) and high (C and D) expression of LVI in H&E staining (A and C, ×100) and D2-40 immunostaining (B and D, ×100) specimens. A previous study demonstrated that there was a significant association between routine H&E-stained sections and immunostaining for D2-40 in 976 lymph node-negative patients (11). Proper tissue handling of surgically removed BC tumors is critical for an accurate assessment of the predictive and prognostic biomarkers (i.e. Ki-67 index value) and the tissue retraction artifacts are also known to be caused by insufficient fixation (12). At our hospital great care is taken to avoid insufficient tissue fixation (13) because an inaccurate assessment of blood vessel invasion of tumor cells does not provide sufficient data on the key antibodies CD31, CD34, and podoplanin/D2-40 and produces a lower frequency of blood vessel invasion (~3%) (12). In this study, we did not use both CD31 and CD34 antibodies for the detection of LVI.

Figure 1.

Detection of low and high expression of LVI in H&E staining and D2-40 immunostaining specimens. A representative case with low LVI stained with (A) H&E and (B) D2-40. A representative case with high LVI stained with (C) H&E and (D) D2-40. Black arrows indicate LVI (all magnification, ×100). H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

BC subtypes and adjuvant therapy

Hormone receptor (HR) positive (ER/PgR) and HER2 negative tumors with lower Ki-67 index values (<20%) were classified as luminal A type, those with higher Ki-67 index values (≥20%) as luminal B type, HR positive and HER2 positive tumors as luminal HER2 type, HR negative and HER2 positive tumors as HER2 enriched, and HR negative and HER2 negative tumors as TN type. Most of the cases with luminal type tumors received endocrine therapy (tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitor) and most of the cases with TN and HER2 type were treated with chemotherapy (anthracycline containing regimen +/- taxane, and anti-HER2 therapy if HER2 positive). Anti-HER2 therapy (trastuzumab) was used in Japan after receiving approval in 2008.

Statistical analysis

The intergroup comparisons between the LVI-positive (low and high) and LVI-negative groups were conducted using the chi-square test and the Fisher's exact test; the P-value applies to the overall comparison of the three groups. The Kaplan-Meier test was used to calculate cumulative disease-free survival (DFS) and tested with the log rank procedure. The univariate and multivariate analyses for factors related to DFS were performed using the Cox proportional hazard model (SPSS version 21). The prognosis was compared between LVI-positive and LVI-negative groups. The median follow-up period was 95.0 months.

Results

Patient characteristics

Table I shows the patient characteristics. Out of 4652 cases, 65% of the cases were postmenopausal, and 70% of the cases had a T1 (<2 cm) tumor and pathologically negative nodes. In terms of the biological markers, the ER- and PgR-positive rates were 80.9 and 72.1%, respectively. HER2 positive cases had a rate of 13.4% and the p53 overexpression cases had a rate of 15.1%. Low proliferation (Ki-67 ≤20%) was observed in 40.6% of the cases and high proliferation (50%≤ Ki-67) in 16% of the cases.

Table I.

Characteristics of 4,652 patients with primary breast cancer.

| Characteristic | Number of patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Menopausal status | |

| Premenopausal | 1,614 (34.7) |

| Postmenopausal | 3,026 (65.0) |

| Male | 12 (0.3) |

| Tumor size | |

| T1 | 3,286 (70.6) |

| T2 | 1,205 (25.9) |

| T3, 4 | 120 (2.6) |

| Unknown | 41 (0.9) |

| Number of involved nodes | |

| 0 | 3,242 (69.7) |

| 1-3 | 1,062 (22.8) |

| ≥4 | 338 (7.3) |

| Unknown | 10 (0.2) |

| Estrogen receptor | |

| Negative | 888 (19.1) |

| Positive | 3,764 (80.9) |

| Progesterone receptor | |

| Negative | 1,299 (27.9) |

| Positive | 3,353 (72.1) |

| HER2 | |

| Negative | 4,030 (86.6) |

| Positive | 622 (13.4) |

| p53-overexpression | |

| Without | 3,769 (81.0) |

| With | 701 (15.1) |

| Unknown | 182 (3.9) |

| Ki-67 | |

| ≤20% | 1,887 (40.6) |

| 21–49% | 2,022 (43.4) |

| ≥50% | 743 (16.0) |

| Grade | |

| 1 | 2,466 (53.0) |

| 2 | 1,078 (23.2) |

| 3 | 1,108 (23.8) |

| Total | 4,652 |

HER2, receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2.

Clinicopathological factors and LVI in primary BC

The LVI expression rates were 29.2% (low: 19.7% and high: 9.5%) in all primary cases. Table II shows a significant positive association between the LVI positive rate and the ER/PgR negative rate (P=0.007 and P=0.01, respectively), HER2 positive rate (P<0.0001), p53 overexpression (P<0.0001), higher Ki-67 index values (P<0.0001), higher nuclear grade (P<0.0001), positive nodes (P<0.0001), and larger tumors (P<0.0001).

Table II.

Clinicopathological factors and LVI in primary breast cancer (n=4652).

| LVI-negative | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Variables | Category | LVI-positive | Low | High | Total | P-valuea |

| Menopausal status | Premenopausal | 1,066 (66.0) | 342 | 206 (12.8) | 1,614 | |

| Postmenopausal | 2,218 (73.3) | 574 | 234 (7.7) | 3,026 | <0.0001 | |

| Male | 9 (75.0) | 1 | 2 (16.7) | 12 | ||

| Tumor size | T1 | 2,589 (78.8) | 538 | 159 (4.8) | 3,286 | |

| T2 | 623 (51.7) | 342 | 240 (19.9) | 1,205 | <0.0001 | |

| T3, 4 | 54 (45.0) | 28 | 38 (31.7) | 120 | ||

| Number of Involved Nodes | 0 | 2,656 (81.9) | 486 | 100 (3.1) | 3,242 | |

| 1-3 | 528 (49.7) | 333 | 201 (18.9) | 1,062 | <0.0001 | |

| > 4 | 104 (30.8) | 92 | 141 (41.7) | 338 | ||

| Estrogen receptor | Negative | 597 (67.2) | 184 | 107 (12.0) | 888 | |

| Positive | 2,696 (71.6) | 733 | 335 (8.9) | 3,764 | 0.007 | |

| Progesterone receptor | Negative | 906 (69.7) | 243 | 150 (11.5) | 1,299 | |

| Positive | 2,387 (71.2) | 674 | 292 (8.7) | 3,353 | 0.01 | |

| HER2 | Negative | 2,918 (72.4) | 761 | 351 (8.7) | 4,030 | |

| Positive | 375 (60.3) | 156 | 91 (14.6) | 622 | <0.0001 | |

| p53 overexpression | Without | 2,693 (71.5) | 741 | 335 (8.9) | 3,769 | ≥ |

| With | 442 (63.1) | 160 | 99 (14.1) | 701 | <0.0001 | |

| Ki-67 | ≤20% | 1,501 (79.5) | 299 | 87 (4.6) | 1,887 | |

| 21–49% | 1,297 (64.1) | 469 | 256 (12.7) | 2,022 | <0.0001 | |

| ≥50% | 495 (66.6) | 149 | 99 (13.3) | 743 | ||

| Nuclear grade | 1 | 1,980 (80.3) | 360 | 126 (5.1) | 2,466 | |

| 2 | 615 (57.1) | 315 | 148 (13.7) | 1,078 | <0.0001 | |

| 3 | 698 (63.0) | 242 | 168 (15.2) | 1,108 | ||

| Total | 3,293 | 917 | 442 | 4,652 | ||

The P-value shows that there was a significant difference when the LVI negative group was compared to both the high and low positive groups. LVI, lymphovascular invasion; HER2, receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2.

BC subtypes and LVI

The subtypes was significantly associated with LVI positivity; 20% in Luminal A, 34.6% in Luminal B, 40.9% in Luminal/HER2, 38.1% in HER2 enriched, and 29.8% in TN cases (Table III).

Table III.

Breast cancer subtypes and LVI.

| LVI-positive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Subtype | LVI-negative | Low | High | Total | P-value (vs. Luminal A) |

| Luminal A | 1,409 (80.0) | 277 | 75 (4.3) | 1,761 | - |

| Luminal B | 1,149 (65.4) | 390 | 219 (12.5) | 1,758 | <0.0001 |

| Luminal/HER2 | 182 (59.1) | 77 | 49 (15.9) | 308 | <0.0001 |

| HER2-enriched | 193 (61.9) | 78 | 41 (13.1) | 312 | <0.0001 |

| Triple negative | 360 (70.2) | 95 | 58 (11.3) | 513 | <0.0001 |

| Total | 3,293 | 917 | 442 | 4,652 | <0.0001 |

LVI, lymphovascular invasion; HER2, receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2.

Adjuvant therapy and LVI in primary BC

There was a significant relationship between the level of LVI and adjuvant therapy. Most of the cases with negative LVI did not receive chemotherapy and more than 50% of the cases with positive LVI had chemo-endocrine therapy (Table IV).

Table IV.

Adjuvant therapy and LVI in primary breast cancer.

| LVI-positive | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Adjuvant therapy | LVI-negative | Low | High | Total | P-value (vs. none) |

| None | 477 (85.0) | 67 | 17 (3.0) | 561 | - |

| Chemotherapy | 399 (62.1) | 147 | 97 (15.1) | 643 | <0.0001 |

| Endocrine therapy | 2,034 (78.3) | 445 | 118 (4.5) | 2,597 | 0.0004 |

| Chemo-endocrine therapy | 378 (44.8) | 258 | 209 (24.8) | 845 | <0.0001 |

| Total | 3,288 | 917 | 441 | 4,644 | |

LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

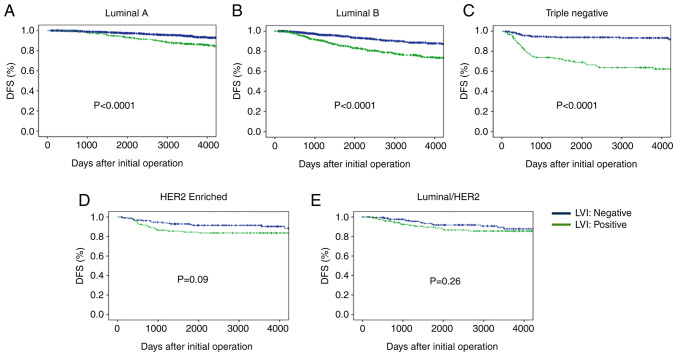

Disease-free survival (DFS) according to BC subtypes and LVI status

DFS rates after initial treatment according to BC subtypes are shown in Fig. 2. Cases with negative LVI had a significantly higher DFS rate than those with positive LVI in the Luminal A type cases. Similar findings were observed in the Luminal B type cases. There were significant differences in DFS between the LVI positive and negative status in the TN subtypes, but there was no difference in the Luminal/HER2 and HER2 enriched subtypes (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

DFS according to BC Subtypes and LVI status. Cases with negative LVI had a significantly higher DFS rate compared with those with positive LVI in the (A) Luminal A and (B) Luminal B type cases. There were significant differences in DFS between the LVI-positive and -negative status in the (C) triple negative subtypes, but there was no difference in the (D) HER2-enriched and (E) Luminal/HER2 subtypes. DFS, disease-free survival; BC, breast cancer; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; HER2, receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the factors for DFS were performed using the following factors: tumor size, nodal status, Ki-67 index value, p53 overexpression, nuclear grade and LVI. A multivariate analysis revealed that LVI was a significant factor in Luminal B and TN subtypes and not in Luminal/HER2 and HER2 enriched subtypes (Table V).

Table V.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of the factors for DFS according to breast cancer subtypes.

| A, Luminal A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| P-value | |||

|

|

|||

| Variables | Category | Univariate | Multivariate |

| Tumor size | <2/≥2 cm | <0.0001 | 0.006 |

| Nodal status | Negative/positive | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Ki-67 | ≤20%/>20% | - | - |

| p53 overexpression | With/without | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Nuclear grade | 1+2/3 | 0.065 | 0.25 |

| LVI | Negative/positive | <0.0001 | 0.12 |

|

| |||

| B, Luminal B | |||

|

| |||

| P-value | |||

|

|

|||

| Variables | Category | Univariate | Multivariate |

|

| |||

| Tumor size | <2/≥2 cm | <0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Nodal status | Negative/positive | <0.0001 | 0.007 |

| Ki-67 | ≤20%/>20% | - | - |

| p53 overexpression | With/without | 0.69 | - |

| Nuclear grade | 1+2/3 | 0.064 | 0.17 |

| LVI | Negative/positive | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||

| C, Luminal/HER2 | |||

|

| |||

| P-value | |||

|

|

|||

| Variables | Category | Univariate | Multivariate |

|

| |||

| Tumor size | <2/≥2 cm | 0.041 | 0.095 |

| Nodal status | Negative/positive | 0.023 | 0.17 |

| Ki-67 | ≤20%/>20% | 0.18 | - |

| p53 overexpression | With/without | 0.53 | - |

| Nuclear grade | 1+2/3 | 0.41 | - |

| LVI | Negative/positive | 0.27 | - |

|

| |||

| D, HER2-enriched | |||

|

| |||

| P-value | |||

|

|

|||

| Variables | Category | Univariate | Multivariate |

|

| |||

| Tumor size | <2/≥2cm | 0.033 | 0.092 |

| Nodal status | Negative/positive | 0.025 | 0.14 |

| Ki-67 | ≤20%/>20% | 0.73 | - |

| p53 overexpression | With/without | 0.23 | - |

| Nuclear grade | 1+2/3 | 0.96 | - |

| LVI | Negative/positive | 0.09 | 0.75 |

|

| |||

| E, Triple negative | |||

|

| |||

| P-value | |||

|

|

|||

| Variables | Category | Univariate | Multivariate |

|

| |||

| Tumor size | <2/≥2 cm | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Nodal status | Negative/positive | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Ki-67 | ≤20%/>20% | 0.024 | 0.068 |

| p53 overexpression | With/without | 0.29 | - |

| Nuclear grade | 1+2/3 | 0.23 | - |

| LVI | Negative/positive | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

LVI, lymphovascular invasion; HER2, receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2.

Discussion

The clinical and prognostic significance of LVI in primary BC, especially in relation to BC subtypes, was investigated in this retrospective study. The LVI expression rates were 29.2% (low: 19.7% and high: 9.5%) in all primary BC cases which is similar to the findings in some studies (11,14–18), but lower in other studies (19,20). LVI was significantly associated with premenopausal status, larger tumors, positive nodes, negative ER/PgR, HER2 positivity, p53 overexpression, higher Ki-67 index value and higher grade. These findings suggest that a positive LVI may be an indication of advanced and aggressive characteristics of primary BC tumors.

Our results demonstrate that LVI is a prognostic factor for predicting patient outcomes. Previous studies reported the prognostic value of LVI independent of lymph node metastasis as well as other tumor characteristics such as histological grade, PgR and HER2 status (11,21,22). However, some studies reported that LVI was not independently associated with the outcome in primary BC cases (23,24) and others reported no association (25,26). In this study, the clinical significance of LVI was evaluated according to BC subtypes. Moreover, the subtypes were significantly associated with LVI positivity (20% in Luminal A, 34.6% in Luminal B, 40.9% in Lumina/HER2, 38.1% in HER2 enriched, and 29.8% in TN). Furthermore, a multivariate analysis revealed that LVI was a significant factor for DFI only in the Luminal B and TN subtypes. LVI is not a significant prognostic factor for Luminal/HER2 and HER2 enriched subtypes. Moreover, LVI was found to be a predictive factor for recurrence in TN BC (27). In a previous study it was reported (28) that there was a relationship between Luminal B/HER2(−) and LVI, basal-like and LVI (P<0.0001, and that there was no significant statistical difference between LVI and other molecular subtypes. A different study reported (29) that the presence of LVI has an independent negative prognostic impact on survival in early BC patients, except in ER-positive grade 3 tumors and in those with Luminal A-like tumors treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. The current study demonstrated that LVI is a significant predictor for DFS in Luminal B and TN subtypes treated with chemotherapy. Furthermore, LVI with more than a pathological complete response (pCR) in surgical BC specimens obtained after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) was a significant independent prognostic factor (29,30). These data suggest that LVI at initial surgery as well as after chemotherapy is a prognostic predictor for DFS in early BC.

Kariri et al (2020) stated that LVI develops through complex molecular pathways and the acquisition of more invasive migration abilities and that this is an important phenomenon required for the process of LVI (31). Further mechanistic evaluation is necessary to explore the inter-relationship of these processes in BC. Asaoka et al (2020) reported that LVI correlated with higher genome copy number aberrations, aneuploidy, and homologous recombination defects. Moreover, tumor immune cell composition and cytolytic activity was not associated with LVI status, but the expression of cell proliferation-related genes significantly increased in LVI positive tumors (32). Kurozumi et al (2019) reported that LVI correlated with a specific transcriptomic profile with a potential prognostic value (33). An examination of the potential factors influencing cell migration in LVI can contribute to an understanding of the mechanisms of LVI so that a targeted therapy for BC can be identified (31).

There are two potential limitations in this study. First, it was a retrospective study. However, the follow-up period was 95.0 months in more than 4,000 cases and adjuvant treatment was performed based on the recommendations of the St. Gallen's International Meeting. Second, the subtypes were identified using IHC markers. However, the IHC method is cost efficient and does not need highly experienced technicians.

In conclusion, the clinical significance of LVI was analyzed to investigate the biology and prognosis of BC cases. LVI significantly was associated with larger tumors, positive nodes and aggressive characteristics (i.e. Ki-67, p53 overexpression, nuclear grade and subtype). Luminal A type had a lower LVI rate and the HER2 type had a higher LVI rate. Moreover, LVI was a significant prognostic factor in Luminal B and TN subtypes. These data suggest that the LVI status is useful in predicting the prognosis for DFS in HER2 negative BC cases.

Acknowledgements

The abstract was presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium Dec 7–10, 2021 in San Antonio, TX and published as abstract no. P4-07-12 in Cancer Res 82 (Suppl 4): 2022. The authors would like thank Dr Toyozumi (Department of Pathology, Kumamoto City Hospital, Kumamoto, Japan) for their technical assistance and for the collection of cancer tissue samples.

Funding Statement

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

RN and NA performed the experiments and conducted the data analysis. RN was a major contributor to the preparation of the manuscript. TO, YO, MN, HO and MF made substantial contributions to the design of the study. RN and NA confirm the authenticity of all the raw data in this study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Kumamoto Shinto General Hospital (approval no. 2021-J14-001). Written informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all of the patients.

Patient consent for publication

All patients or guardians of the patients provided informed consent for the publication of any associated data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends-an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:16–27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statista Research Department; May 7, 2021. Estimated number of cancer cases diagnosed in women in Japan in 2020 by cancer site. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalasani P. What are the prognostic and predictive factors for breast cancer? www.medscape.com/answers/1947145-155277 Medscape. 2021 Feb 04; [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meguerditchian AN, Bairati I, Lagacé R, Harel F, Kibrité A. Prognostic significance of lymphovascular invasion in surgically cured rectal carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2005;189:707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotan Y, Gupta A, Shariat SF, Palapattu GS, Vazina A, Karakiewicz PI, Bastian PJ, Rogers CG, Amiel G, Perotte P, et al. Lymphovascular invasion is independently associated with overall survival, cause-specific survival, and local and distant recurrence in patients with negative lymph nodes at radical cystectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6533–6539. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herman CM, Wilcox GE, Kattan MW, Scardino PT, Wheeler TM. Lymphovascular invasion as a predictor of disease progression in prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:859–863. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200006000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stålberg K, Bjurberg M, Borgfeldt C, Carlson J, Dahm-Kähler P, Flöter-Rådestad A, Hellman K, Hjerpe E, Holmberg E, Kjølhede P, et al. Lymphovascular space invasion as a predictive factor for lymph node metastases and survival in endometrioid endometrial cancer-a Swedish gynecologic cancer group (SweGCG) study. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:1628–1633. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2019.1643036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teel P. Vascular invasion as a prognostic factor in breast carcinoma. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1964;118:1006–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kai K, Nishimura R, Arima N, Miyayama H, Iwase H. p53 expression status is a significant molecular marker in predicting the time to endocrine therapy failure in recurrent breast cancer: A cohort study. Int J Clin Oncol. 2006;11:426–433. doi: 10.1007/s10147-006-0601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kikuchi S, Osako T, Nishiyama Y, Nakano M, Tashima R, Fujisue M, Toyozumi Y, Arima N. P53 overexpression in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Cytol Histol. 2014;5:269–274. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rakha EA, Martin S, Lee AH, Morgan D, Pharoah PD, Hodi Z, Macmillan D, Ellis IO. The prognostic significance of lymphovascular invasion in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:3670–3680. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoda SA, Brogi E, Koerner FC, Rosen PP. fifth edition. Wolters Kluwer; 2014. Rosen's Breast Pathology; pp. p477–482. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arima N, Nishimura R, Osako T, Nishiyama Y, Fujisue M, Okumura Y, Nakano M, Tashima R, Toyozumi Y. The importance of tissue handling of surgically removed breast cancer for an accurate assessment of the Ki-67 index. J Clin Pathol. 2016;69:255–259. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debled M, de Mascarel I, Brouste V, Mauriac L, MacGrogan G. Re: Population-based study of peritumoral lymphovascular invasion and outcome among patients with operable breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:275–277. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ejlertsen B, Jensen MB, Rank F, Rasmussen BB, Christiansen P, Kroman N, Kvistgaard ME, Overgaard M, Toftdahl DB, Mouridsen HT, Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group Population-based study of peritumoral lymphovascular invasion and outcome among patients with operable breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:729–735. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chas M, Boivin L, Arbion F, Jourdan ML, Body G, Ouldamer L. Clinicopathologic predictors of lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients according to molecular subtype. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2018;47:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houvenaeghel G, Cohen M, Classe JM, Reyal F, Mazouni C, Chopin N, Martinez A, Daraï E, Coutant C, Colombo PE, et al. Lymphovascular invasion has a significant prognostic impact in patients with early breast cancer, results from a large, national, multicenter, retrospective cohort study. ESMO Open. 2021;6:100316. doi: 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang S, Zhang D, Gong M, Wen L, Liao C, Zou L. High lymphatic vessel density and presence of lymphovascular invasion both predict poor prognosis in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:335. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3338-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akrami M, Meshksar A, Ghoddusi JM, Safarpour MM, Tahmasebi S, Zangouri V, Talei A. Prognostic role of lymphovascular invasion in patients with early breast cancer. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2021;12:671–677. doi: 10.1007/s13193-021-01367-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohammed ZM, McMillan DC, Edwards J, Mallon E, Doughty JC, Orange C, Going JJ. The relationship between lymphovascular invasion and angiogenesis, hormone receptors, cell proliferation and survival in patients with primary operable invasive ductal breast cancer. BMC Clin Pathol. 2013;13:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6890-13-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohammed RA, Martin SG, Mahmmod AM, Macmillan RD, Green AR, Paish EC, Ellis IO. Objective assessment of lymphatic and blood vascular invasion in lymph node-negative breast carcinoma: Findings from a large case series with long-term follow-up. J Pathol. 2011;223:358–365. doi: 10.1002/path.2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinder SE, Ellis IO, Galea M, O'Rouke S, Blamey RW, Elston CW. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. III. Vascular invasion: Relationship with recurrence and survival in a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1994;24:41–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freedman GM, Li T, Polli LV, Anderson PR, Bleicher RJ, Sigurdson E, Swaby R, Dushkin H, Patchefsky A, Goldstein L. Lymphatic space invasion is not an independent predictor of outcomes in early stage breast cancer treated by breast-conserving surgery and radiation. Breast J. 2012;18:415–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2012.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ovcaricek T, Frkovic SG, Matos E, Mozina B, Borstnar S. Triple negative breast cancer-prognostic factors and survival. Radiol Oncol. 2011;45:46–52. doi: 10.2478/v10019-010-0054-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camp RL, Rimm EB, Rimm DL. A high number of tumor free axillary lymph nodes from patients with lymph node negative breast carcinoma is associated with poor outcome. Cancer. 2000;88:108–113. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000101)88:1<108::AID-CNCR15>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim SH, Simkovich-Heerdt A, Tran KN, Maclean B, Borgen PI. Women 35 years of age or younger have higher locoregional relapse rates after undergoing breast conservation therapy. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(98)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Na YM, Ryu YJ, Cho JS, Park MH, Yoon JH. Lymphovascular invasion as a predictive factor for recurrence in triple-negative breast cancer. Indian J Surg. 2021;83:475–483. doi: 10.1007/s12262-021-02783-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morkavuk ŞB, Güner M, Çulcu S, Eroğlu A, Bayar S, Ünal AE. Relationship between lymphovascular invasion and molecular subtypes in invasive breast cancer. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e13897. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamy AS, Lam GT, Laas E, Darrigues L, Balezeau T, Guerin J, Livartowski A, Sadacca B, Pierga JY, Vincent-Salomon A, et al. Lymphovascular invasion after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is strongly associated with poor prognosis in breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;169:295–304. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4610-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryu YJ, Kang SJ, Cho JS, Yoon JH, Park MH. Lymphovascular invasion can be better than pathologic complete response to predict prognosis in breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11647. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kariri YA, Aleskandarany MA, Joseph C, Kurozumi S, Mohammed OJ, Toss MS, Green AR, Rakha EA. Molecular complexity of lymphovascular invasion: The role of cell migration in breast cancer as a prototype. Pathobiology. 2020;87:218–231. doi: 10.1159/000508337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asaoka M, Patnaik SK, Zhang F, Ishikawa T, Takabe K. Lymphovascular invasion in breast cancer is associated with gene expression signatures of cell proliferation but not lymphangiogenesis or immune response. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;181:309–322. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05630-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurozumi S, Joseph C, Sonbul S, Alsaeed S, Kariri Y, Aljohani A, Raafat S, Alsaleem M, Ogden A, Johnston SJ, et al. A key genomic subtype associated with lymphovascular invasion in invasive breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2019;120:1129–1136. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0486-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.